Abstract

Relational frame theory (RFT) is a contemporary behavior-analytic account of language and cognition. Since it was first outlined in 1985, RFT has generated considerable controversy and debate, and several claims have been made concerning its evidence base. The present study sought to evaluate the evidence base for RFT by undertaking a citation analysis and by categorizing all articles that cited RFT-related search terms. A total of 174 articles were identified between 1991 and 2008, 62 (36%) of which were empirical and 112 (64%) were nonempirical articles. Further analyses revealed that 42 (68%) of the empirical articles were classified as empirical RFT and 20 (32%) as empirical other, whereas 27 (24%) of the nonempirical articles were assigned to the nonempirical reviews category and 85 (76%) to the nonempirical conceptual category. In addition, the present findings show that the majority of empirical research on RFT has been conducted with typically developing adult populations, on the relational frame of sameness, and has tended to be published in either The Psychological Record or the Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. Overall, RFT has made a substantial contribution to the literature in a relatively short period of time.

Keywords: relational frame theory, verbal behavior, citation analysis

Relational frame theory (RFT) is a contemporary behavior-analytic account of language and cognition (Hayes, Barnes-Holmes, & Roche, 2001). Stated simply, RFT contends that arbitrarily applicable relational responding, such as that seen during tests for derived stimulus relations, is a key process in human verbal behavior. To explain and investigate this process empirically, RFT makes a distinction between nonarbitrary and arbitrary forms of relational responding. Most species can, for instance, readily learn to select the larger of two stimuli from an array of different stimulus sets and across a number of contexts. Training in such nonarbitrary relational responding is entirely bound by the formal, physical properties of the related events (Giurfa, Zhang, Jenett, Menzel, & Srinivasan, 2001; Stewart & McElwee, 2009). Nonarbitrary relational responding is said to occur when, in the absence of reinforcement, an organism selects the larger of two stimuli based on a history with multiple stimulus sets and contexts. However, burgeoning empirical evidence now shows that verbally able humans can also learn to respond relationally to objects or events when the relation is defined not by the physical properties of the objects but rather by additional contextual cues (e.g., Hayes, Barnes-Holmes, & Roche, 2001; Sidman, 1994). For example, consider a young child who learns that “X is taller than Y.” Subsequently, he or she may when asked, “which is shorter?” respond “Y,” without any further training. According to RFT, this response, which is controlled solely by the contextual cues “taller” and “shorter” and not by any physical relations, is arbitrarily applicable because it can be applied to any stimuli regardless of their physical properties.

Specific kinds of arbitrarily applicable relational responding are called relational frames, and have the properties of mutual entailment, combinatorial entailment, and transformation of functions. Mutual entailment refers to the derived bidirectionality of stimulus relations, such that if Stimulus A is related to Stimulus B in a specific context, then a relation between B and A is also entailed in that context. If the relation is one of sameness or coordination (e.g., A is the same as B), then so too is the entailed relation (i.e., B is the same as A). However, if A is greater than B, then B is less than A. Combinatorial entailment refers to instances in which two or more relations are combined to produce a third relation. For example, if A is greater than B and B is greater than C, then A is greater than C and C is less than A. Transformation of stimulus functions is said to occur when the psychological functions of stimuli in a derived relation are transformed based on the nature of the relation and the psychological functions of the other members of that relation. For example, if A is greater than B and A is paired with shock, then presentations of B will evoke calm or reduced arousal (Dougher, Hamilton, Fink, & Harrington, 2007; Dymond & Rehfeldt, 2000). Relational frame theory contends that arbitrarily applicable relational responding generally, and the transformation of functions in particular, represent the key behavioral process in human verbal behavior and that it is possible to define verbal events accordingly.

Several authors have provided summaries of the main tenets of RFT (e.g., Barnes, 1994; Gross & Fox, 2009; Hayes & Wilson, 1996), yet to many, the theory remains complex and often controversial. First outlined in a presentation given at the annual convention of the Association for Behavior Analysis in 1985 and published as a chapter in an edited volume in 1989 (Hayes & Hayes, 1989), RFT has generated considerable scholarly debate in a relatively short period of time (Gross & Fox). For instance, it has been described as “unintelligible, ambiguous, opaque, and contradictory” (Burgos, 2003, p. 19), “obscure and occasionally incoherent” (Burgos, 2004, p. 53), and its evidence base as “data in search of a principle” (Palmer, 2004a). Other commentators have asked, “Who can understand RFT?” (Tonneau, 2002) and whether RFT is “post-Skinnerian, post-Skinner, or neo-Skinnerian?” (Ingvarsson & Morris, 2004).

Despite the misunderstandings and controversy that RFT has generated, the contributions that it has made to the broader scientific literature base have been described by other commentators as “prolific, generating scores of theoretical and empirical papers in the past decade” (Galizio, 2003, p. 159). By 2001, the first booklength treatment of RFT was published (Hayes, Barnes-Holmes, & Roche, 2001), and in 2003, Hayes, Barnes-Holmes, and Roche declared that, “RFT is now 18 years old. It has spawned more basic human operant work than almost any theory put forward during that time.” (2003, p. 40). The source of these claims about the empirical base for RFT was not specified. However, 3 years later, Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda, and Lillis (2006) claimed that “RFT has become one of the most actively researched basic behavior analytic theories of human behavior, with over 70 empirical studies focused on its tenets” (p. 5). Again, no source was provided in support of the statement that RFT had, in the relatively short space of approximately two decades, generated an evidence base of more than 70 empirical studies.

The burgeoning interest generated in RFT has led to the establishment, in 2005, of a new professional organization, the Association for Contextual Behavioral Science (ACBS). The ACBS is an organization that has emerged directly from RFT and related (e.g., acceptance and commitment therapy; ACT) research movements and currently has over 2,400 members from 44 different countries (Viladarga, Hayes, Levin, & Muto, 2009). The ACBS Web site, which is intended to act as a clearinghouse resource for the steady accumulation of empirical support for ACT and RFT from a range of domains, lists over 150 empirical articles “on RFT ideas or very closely related” (http://www.contextualpsychology.org/rft_empirical_support). These articles range from those published in 1986 up to and including in press articles, and ACBS members may nominate further articles for inclusion on this list. A search conducted using the filter “RFT: Empirical” on another page on the ACBS Web site (http://www.contextualpsychology.org/publications) lists 168 articles from 1986 to in press.

Clearly, there are conflicting details surrounding the scientific evidence base for RFT and the grounds on which existing claims have been based. It follows, therefore, that an objective assessment of the evidence base for RFT would be both salutary and informative. Bibliometric methods, such as citation analysis, involve searching literature databases with relevant key words to identify trends and may help to provide an objective assessment of the evidence base for RFT. In behavior analysis, citation analysis has been used several times previously to reveal various authorship trends, journal citation patterns, and current areas of research emphasis (e.g., Carr & Britton, 2003; Critchfield, 2002; Dymond & Critchfield, 2001; Dymond, O'Hora, Whelan, & O'Donovan, 2006; Marcon-Dawson, Vicars, & Miguel, 2009; Northup, Vollmer, & Serrett, 1993; Shabani, Carr, Petursdottir, Esch, & Gillet, 2004). For instance, Dymond et al. investigated the number of citations of Skinner's (1957) Verbal Behavior from empirical and nonempirical sources, and found that the majority of citations were from the latter category (see also Dixon, Small, & Rosales, 2007; Dymond & Alonso-Alvarez, in press; Sautter & LeBlanc, 2006). In this way, citation analysis provides an approximate measure of the extent to which relevant key-word search terms are to be found in the literature databases.

To date, there has been no prior citation analysis of RFT articles. The present study, therefore, sought to undertake the first such citation analysis by searching literature databases for articles that cited search terms related to RFT and assigning the subsequent articles to various categories.

METHOD

Database Searches

The search terms relational frame theory, relational frames, and arbitrarily applicable relations were individually entered into the ISI Web of Knowledge (Web of Science) and PsycINFO databases. Searches were conducted for articles that included at least one of these key words. An upper date limit of 2008 was employed, and the default lower date limit was 1981. Therefore, the initial search was conducted on articles published between 1981 and 2008 (inclusive).

The results of each search were checked for duplicate hits, and a final data set was compiled. Only journal articles deemed relevant were included in the final data set; that is, books, book chapters, dissertation abstracts, and articles deemed irrelevant or unrelated to the search terms were excluded. This resulted in one book, six book chapters, five dissertation abstracts, and 54 unrelated articles being excluded from the final set (the list of excluded articles is available from the first author). The remaining authors' names, article titles, sources, years, and abstracts were then transferred to a spreadsheet.

Article Categories

Following identification of the final data set, each of the four raters (a board-certified behavior analyst, a board-certified assistant behavior analyst, and two masters-level trained doctoral students) consulted their individual spreadsheets and categorized articles as either empirical or nonempirical. Empirical articles reported original data involving the direct manipulation of at least one independent variable and measurement of at least one dependent variable. An example of an empirical article is Steele and Hayes's (1991) study on arbitrarily applicable relational responding in accordance with sameness and opposition. Nonempirical articles did not involve manipulation of any independent variables or measurement of any dependent variables and reported no data. An example of a nonempirical article is Hayes and Leonhard's (1994) article on contrasting definitions of verbal behavior.

Further analyses of empirical articles

Consistent with the approach adopted by Dixon et al. (2007), we undertook further analyses of various parameters of the empirical article dataset. We identified the following parameters: Empirical RFT, Empirical Other, Populations, and Relational Frames.

Empirical RFT articles were articles that cited at least one of the search terms, reported original data involving one or more types of relational frames, defined features of relational frames (i.e., mutual entailment, combinatorial entailment, and transformation of stimulus functions), or the specific predictions of RFT (e.g., the predicted, facilitative effects of multiple-exemplar training; derived relational responding as generalized operant behavior, etc.). Examples of articles from this category are Dymond and Barnes's (1995) study on transformation of functions in accordance with the relational frames of sameness, more than, and less than, and Luciano, Becerra, and Valverde's (2007) study on the role of multiple-exemplar training in facilitating derived equivalence relations in an infant.

Empirical Other articles were articles that cited at least one of the search terms and reported original data but did not directly involve analysis of any of the defining features or the specific predictions of RFT. Examples of articles from this category include a study by Dymond and Barnes (1998) on the effects of instructions on derived transfer of functions through equivalence relations and Barnes-Holmes et al. (2004) on behavioral and electrophysiological measures of semantic priming with derived equivalence relations.

The Populations parameter was a measure based on the demographic information given by each study (Dixon et al., 2007). We recorded the type and age of the samples studied. Sample types were classified as either typically or atypically developing. Atypically developing samples were defined “as evident in the report of any type of label (e.g., physical, psychological, genetic, geriatric, developmental disabilities, etc.) or other descriptors that indicated below-average level of functioning” (Dixon et al., p. 198). Sample ages were classified as adults if the participants ages were reported as being 18 years or older and as children if the ages reported were at 17 years or younger. The sample types and ages parameters produced four mutually exclusive categories: Children Typically Developing, Children Atypically Developing, Adults Typically Developing, and Adults Atypically Developing.

Relational Frames were defined as specific kinds of derived relational responding (Hayes, Fox, et al., 2001, p. 33). Only articles from the Empirical RFT category were subject to additional classification as belonging to one or more of the following: sameness, sameness and opposition, difference, comparison, temporal, and deictic. Examples of articles from this category include Steele and Hayes (1991) on sameness, opposition, and difference, and Rehfeldt, Dillen, Ziomek, and Kowalchuk (2007) on deictic relations.

Subclassification of nonempirical articles

To further identify the content addressed by nonempirical articles, we classified them as either Nonempirical Reviews or Nonempirical Conceptual. Nonempirical Reviews cited at least one of the search terms and were those in which either the book-length description of RFT (Hayes, Barnes-Holmes, & Roche, 2001) or another related book was reviewed (e.g., Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999). Articles in this subcategory include commentaries on target articles and authors' replies to commentaries and reviews. Nonempirical Conceptual articles cited at least one of the search terms but did not systematically manipulate variables to change a participant's behavior (Dymond et al., 2006, p. 77).

Analyses of Interrater Agreement

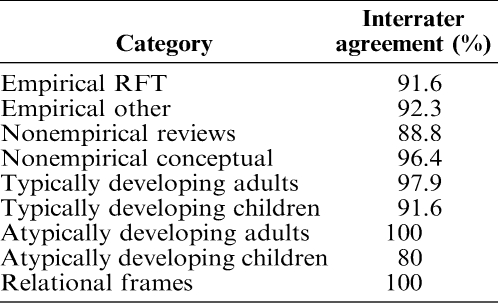

Interrater agreement was defined as both raters assigning an article to an identical category. Percentage agreement was calculated for each article category by dividing the number of agreements by the number of agreements plus disagreements, and multiplying by 100%. Overall, interrater agreement ranged between 80% and 100% (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Interrater agreement for each category

RESULTS

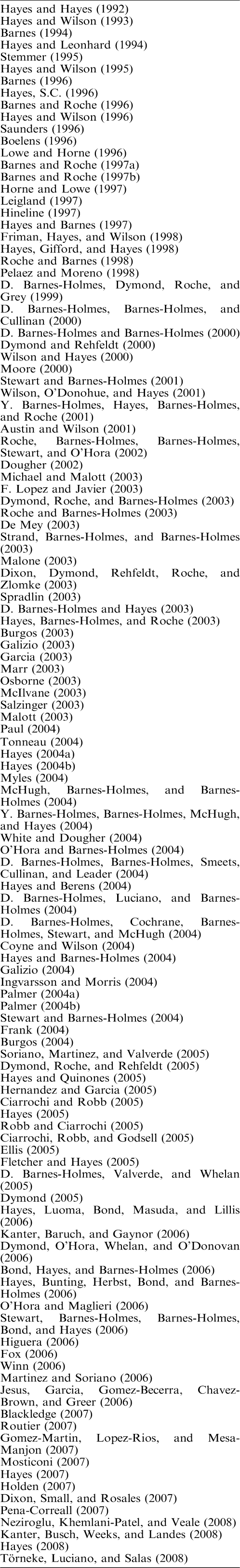

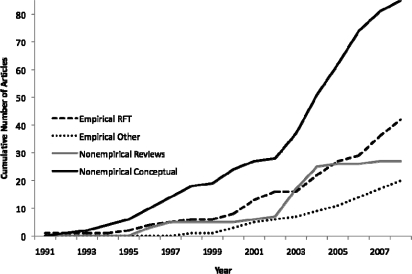

A total of 174 articles were identified and included in the final data set. Of these, 62 articles (36%) were assigned to the Empirical category and 112 (64%) to the Nonempirical category (see Table 2). Figure 1 shows the cumulative number of articles from the Empirical and Nonempirical categories between 1991 and 2008. Using the default setting of 1981, the first article to cite one or more of the search terms was published in 1991. Accordingly, the census period was between 1991 and 2008. The number of citations of RFT-related search terms by Empirical and Nonempirical articles had separated, in terms of level and trend, by 1993, with the highest number of citations coming from the Nonempirical category. This trend continued throughout the review period. Citations from both categories of articles increased in 1995, with a proportionately larger increase in Nonempirical citations, before both trends leveled off between 1998 and 1999. The greatest increase in Nonempirical citations occurred in 2001 following publication of the edited volume on RFT (Hayes, Barnes-Holmes, & Roche, 2001). Empirical citations have also increased steadily from 2000 onwards (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Nonempirical articles

Figure 1.

The cumulative number of Empirical and Nonempirical articles per year between 1991 and 2008 that reported at least one of the search terms.

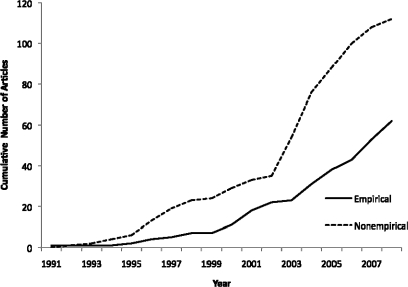

Of the 62 Empirical articles, 42 (68%) were classified as Empirical RFT and 20 (32%) as Empirical Other (see Table 3). Figure 2 shows the cumulative number of articles from the Empirical RFT and Empirical Other categories. Empirical RFT articles have appeared since 1991 (Steele & Hayes, 1991) and have continued to steadily increase in number from 1994 across all years except 1999 and 2003. Empirical Other articles first appeared in 1998 (Dymond & Barnes, 1998) and have increased over the years also, although at a slower rate.

Table 3.

Empirical RFT and empirical other articles

Figure 2.

The cumulative number of Empirical RFT, Empirical Other, Nonempirical Reviews, and Nonempirical Conceptual articles per year from 1991 to 2008 that reported at least one of the search terms.

Of the 112 Nonempirical articles, 27 (24%) were assigned to the Nonempirical Reviews category and 85 (76%) to the Nonempirical Conceptual category. Figure 2 shows the cumulative number of articles from the Nonempirical Reviews and Nonempirical Conceptual categories. Nonempirical Conceptual citations have appeared since 1992 and have grown since then. The pace of their growth increased around 2003 and this pace was maintained until 2006, when it began to return to its previous level. Nonempirical Reviews citations have also steadily appeared across the review period, but at a slower rate than Nonempirical Conceptual citations. Not surprisingly, the biggest increase in citations from Nonempirical Reviews articles occurred between 2002 and 2003, following publication of the edited volume on RFT. Interestingly, during 2003 there were also no Empirical RFT articles published.

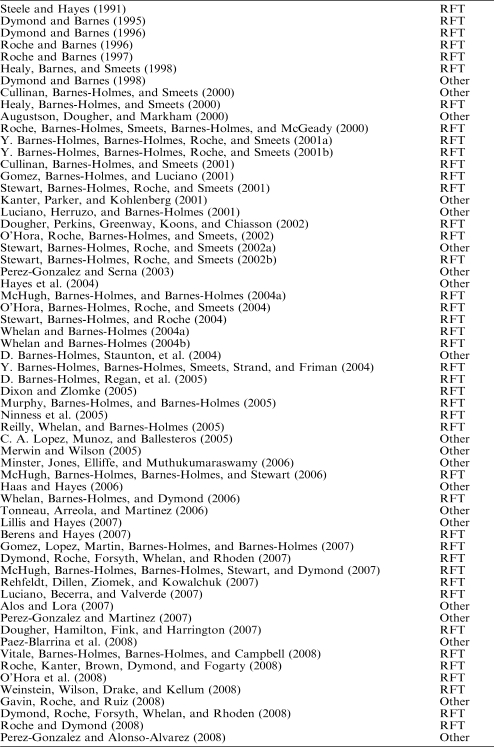

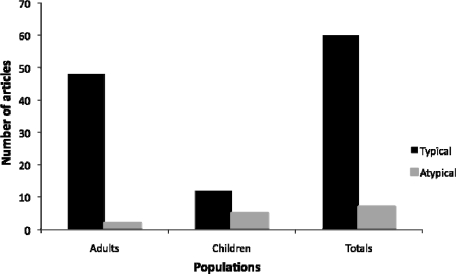

Analysis of the Populations studied in both categories of empirical articles indicates that the majority of research has been conducted with typically developing adult populations (see Figure 3). Of the articles assigned to the population categories, 72% involved typically developing adults, 18% typically developing children, 3% atypically developing adults, and 7% atypically developing children.

Figure 3.

The number of articles categorized as typical or atypical adults and children. Note that the totals do not sum to the total of the Empirical RFT and Empirical Other category because articles may have contributed to more than one population subcategory.

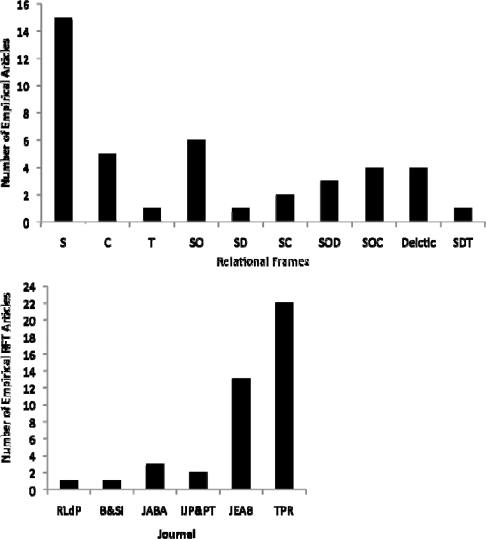

Analysis of the Relational Frames studied in Empirical RFT articles shows that sameness has been the most studied relational frame. The relational frames of sameness and opposition were the second most popular studied and were followed by comparison (Figure 4, top). Only one article has studied sameness and difference, temporal, or the combined relational frames of temporal, sameness, and difference.

Figure 4.

Top: The number of articles on specific relational frames. S = sameness, O = opposition, D = difference, C = comparison, and T = temporal. Bottom: The number of Empirical RFT articles published in various journals. RLdP = Revista Latinoamericana de Psicologia; B&SI = Behavior & Social Issues; JABA = Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis; IJP&PT = International Journal of Psychology & Psychological Therapy; JEAB = Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior; TPR = The Psychological Record.

An additional analysis was conducted on the Empirical RFT articles by identifying the journals in which the articles were published. Figure 4 (bottom) shows that the majority of Empirical RFT articles were published in The Psychological Record (TPR) and the Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior (JEAB), with three articles published in Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis (JABA), two in the International Journal of Psychology & Psychological Therapy (IJP&PT), and one in Revista Latinoamericana de Psicologia (RLdP) and Behavior & Social Issues (B&SI).

DISCUSSION

Within a relatively short period of time, RFT has made a considerable contribution to the empirical and theoretical literature base. During the 17-year review period, 36% of the articles that cited RFT-related search terms were from the Empirical category and 64% were from the Nonempirical category. The present study found that RFT has developed an evidence base of 62 empirical studies based on its key tenets, and that the growth seen in nonempirical citations is partially explained by the increase in the number of Nonempirical Reviews following the publication of Hayes, Barnes-Holmes, and Roche (2001) (a trend that has since leveled off; Figure 2). The findings also show that the number of citations from Nonempirical Conceptual articles continues to the end of the review period, maintaining a long tradition of interpretation in radical behaviorism (Burgos & Donahoe, 2000; Skinner, 1974).

The present findings are broadly consistent with the statement that RFT has generated over 70 empirical studies focused on its key tenets (Hayes, Luoma, et al., 2006). Our analysis identified 62 Empirical articles, 42 (68%) of which were assigned as Empirical RFT articles (Table 3). It is likely that differences in the operational definition of empirical were employed by Hayes, Luoma, et al., making it difficult to compare with the present findings. It is interesting to note that our findings did not identify several articles listed on the ACBS Web site as supportive of RFT or from the heading “RFT: Empirical.” This may also have been related to differences in the definition of empirical and of being supportive of RFT. All of these nonidentified articles were published prior to 1991 and concerned analyses of the determinants of human performance on tests for derived equivalence relations as well as topics from the broader research literature on rule-governed behavior and schedules of reinforcement. For instance, the article by Devany, Hayes, and Nelson (1986) on equivalence class formation in atypically developing children with and without expressive language abilities was not identified by our search but is included on the ACBS list. This often-cited experiment, which showed a correlation between language ability and success on tests for equivalence relations, predated the first publications on RFT and would probably have been assigned to our Empirical Other category. Given the contested nature of the relation between derived stimulus relations and language (e.g., Horne & Lowe, 1996), it is reasonable to assume that the Devany et al. article is deemed supportive of RFT because its findings are consistent with the RFT approach to this issue (i.e., that there is close functional overlap between derived relational responding and language). Another example of an article that was not identified in our search was a study by Barnes and Keenan (1993) on the role of concurrent activities in attenuating covert verbal processes (e.g., counting) during fixed-interval schedules. The relation between research on derived stimulus relations and rule-governed behavior is well known, and the Barnes and Keenan study may be considered to have been inspired by the RFT approach to rule governance. However, it remains unclear exactly how this article is deemed supportive of RFT without also including the majority of related articles on early human operant research on schedules of reinforcement.

Using the empirical articles listed in Table 3, the number of contributors to research articles on RFT may be determined. Of the three editors of the book-length treatment of RFT (Hayes, Barnes-Holmes, & Roche, 2001), Dermot Barnes-Holmes contributed the highest number of empirical articles (32), followed by Bryan Roche (14) and Steven Hayes (4). Other contributors included many of the three editors' former students, such as Yvonne Barnes-Holmes (11), Simon Dymond (9), and Ian Stewart (7). These findings are broadly consistent with previous analyses of the most prolific authors in behavior analysis (Dymond, 2002; Shabani et al., 2004) and indicate that the pioneers of RFT research and their students are important contributors to the majority of empirical RFT articles.

With regards to subject populations, the findings show that the majority of empirical research (72%) has been conducted with typically developing adult populations (mainly college students), and that only a minority involved atypically developing adults (3%) and children (7%). This may partly explain the low number of articles published in JABA. Although RFT is often considered a general theory of normal language and cognition, it makes clear predictions about facilitative interventions aimed at overcoming language deficits in applied populations (e.g., Y. Barnes-Holmes, Barnes-Holmes, & Cullinan, 2001; Y. Barnes-Holmes, Barnes-Holmes, & Murphy, 2004; Berens & Hayes, 2007; Hayes & Berens, 2004; Luciano et al., 2007; O'Toole, Murphy, & Barnes-Holmes, 2009). For instance, one intervention, multiple-exemplar training, has been implemented to facilitate the emergence of mutual and combinatorial entailment in typically developing infants and children (Y. Barnes-Holmes, Barnes-Holmes, Roche, & Smeets, 2001a, 2001b; Berens & Hayes, 2007; Luciano et al., 2007) and derived manding in children with autism (Murphy, Barnes-Holmes, & Barnes-Holmes, 2005). Given these initial encouraging applications, it remains to be seen whether the applied promise of such interventions is subject to further empirical scrutiny within the domain of atypical language development.

Our findings indicate that RFT has made a substantial contribution to the literature in a short period of time. In interpreting the present findings, it may be beneficial to consider the empirical and conceptual literature base of RFT in relation to other, competing behavioral theories of verbal behavior (e.g., Horne & Lowe, 1996; Skinner, 1957) and derived stimulus relations (e.g., Horne & Lowe, 1996; Sidman, 1994, 2000, 2008). However, the respective theories are, in many important respects, conceptually and empirically incompatible (Barnes, 1994; Clayton & Hayes, 1999; Sidman, 2008), making a direct comparison difficult. It was not the objective of the present study to undertake such a comparison but to objectively evaluate, for the first time, the evidence base for RFT. Nonetheless, a direct bibliometric comparison of the contributions made by each of the theories to the literature may prove to be helpful in distinguishing between each account, and future citation analyses should seek to identify the most effective method of doing so.

The main objective of the present study was to provide an objective assessment of the RFT literature base by determining the numbers of different categories of articles that cited at least one of the search terms employed in this analysis. By so doing, and because the present authors are reasonably familiar with the history and development of RFT, we anticipated identifying certain seminal, often-cited articles during our literature searches. As outlined in the Method section, our search terms were individually entered into the databases and a combined final data set emerged. Initially, however, the search term relational frame theory did not identify relevant empirical articles such as Steele and Hayes's (1991) first demonstration of arbitrarily applicable relational responding in accordance with sameness, opposition and difference, or Dymond and Barnes's (1995) study on the transformation of stimulus functions via sameness and comparison. It was only by extending our search to relational frames and arbitrarily applicable relations that these key studies were identified.

There are several possible explanations for the initial failure to identify these articles. First, they were published at the start of, or early into, the review period before sufficient publications on the RFT account of human behavior had accrued. Without this critical mass of literature to refer to, authors, when writing manuscripts for publication and nominating key words for inclusion in search databases, had few sources to refer to (it is the behavior of scientists, after all, that is measured by citation analyses). Second, these empirical studies were initial demonstrations of the key RFT prediction that relational responding may be brought under contextual control through a history of nonarbitrary relational responding. As such, the studies by Steele and Hayes (1991) and Dymond and Barnes (1995) should be considered as early empirical demonstrations of a defining feature of RFT—that multiple patterns of contextually controlled arbitrarily applicable relational responding in accordance with two or more relational frames may emerge given appropriate pretraining—rather than sources of empirical support specifically designed to test a theoretical prediction.

A final, noteworthy finding from the present analysis was that the majority of empirical RFT articles were published in TPR and JEAB (Figure 4). Both of these journals have long histories of publishing empirical and theoretical developments in behavior analysis generally and derived relational responding specifically, and the current findings attest to their significant role in developing the literature base on RFT. It is important, however, to consider the broader impact of research on RFT published in these and the other journals we identified by comparing their relative impact factors. Impact factor is a measure of the frequency with which an average article in a journal is cited during a 2-year period (Garfield, 1972). A journal's impact factor is calculated by dividing the number of current-year citations by the number of articles published in that journal during the previous 2 years. Although impact factor is not the only indicator of a field's vitality, it does provide an objective measure of a field's scholarly prominence and visibility (see Leydesdorff, 2009). Two of the six journals we identified as outlets for empirical research on RFT do not have an impact factor (IJP&PT and B&SI). According to the ISI Thomson-Reuters Journal Citation Reports (2008), the impact factors of the four remaining journals are, TPR (0.435), JEAB (2.155), JABA (0.863), and RLdP (0.435). Because a journal with an impact factor lower than 1.0 is often considered to be low impact (Carr & Britton, 2003), only those Empirical RFT articles that were published in JEAB may be considered to be high impact and likely to be cited in journals outside behavior analysis. Although the use of metrics such as impact factor in describing publication trends in those behavioral journals with (e.g., JABA; Piazza, 2009) and without (e.g., The Analysis of Verbal Behavior; Petursdottir, Peterson, & Peters, 2009) an existing impact factor is a source of ongoing debate, the present findings show that with the exception of articles published in JEAB, the majority of empirical articles on RFT have been published in low-impact journals.

In conclusion, the present study undertook the first citation analysis of RFT, and our findings indicate that RFT has made a substantial contribution to the literature in a short period of time. A growing empirical evidence base is accumulating support for the main tenets of RFT, and there remains a high level of conceptual interest in the RFT approach to topics in language and cognition. Only further research, and updated analyses, will reveal whether the intellectual promise offered by RFT will continue to be realized.

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous reviewers for their detailed and helpful comments and Dermot Barnes-Holmes for an early discussion on the potential pitfalls of citation analysis.

REFERENCES

- Alos F.J, Lora M.D. Contextual control in teaching numbers to a child with intellectual disabilities. Psicothema. 2007;19:435–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustson E.M, Dougher M.J, Markham M.R. Emergence of conditional stimulus relations and transfer of respondent eliciting functions among compound stimuli. The Psychological Record. 2000;50:745–770. [Google Scholar]

- Austin J, Wilson K.G. Response-response relationships in organizational behavior management. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 2001;21:39–53. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes D. Stimulus equivalence and relational frame theory. The Psychological Record. 1994;44:91–124. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes D. Naming as a technical term: Sacrificing behavior analysis at the altar of popularity? Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1996;65:264–267. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1996.65-264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes D, Keenan M. Concurrent activities and instructed human fixed-interval performance. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1993;59:501–520. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1993.59-501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes D, Roche B. Relational frame theory and stimulus equivalence are fundamentally different: A reply to Saunders' commentary. The Psychological Record. 1996;46:489–507. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes D, Roche B. A behavior-analytic approach to behavioral reflexivity. The Psychological Record. 1997a;47:543–572. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes D, Roche B. Relational frame theory and the experimental analysis of human sexuality. Applied & Preventive Psychology. 1997b;6:117–135. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Holmes D, Barnes-Holmes Y. Explaining complex behavior: Two perspectives on the concept of generalized operant classes. The Psychological Record. 2000;50:251–265. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Holmes D, Barnes-Holmes Y, Cullinan V. Relational frame theory and Skinner's Verbal Behavior: A possible synthesis. The Behavior Analyst. 2000;23:69–84. doi: 10.1007/BF03392000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Holmes D, Barnes-Holmes Y, Smeets P.M, Cullinan V, Leader G. Relational frame theory and stimulus equivalence: Conceptual and procedural issues. International Journal of Psychology & Psychological Therapy. 2004;4:181–214. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Holmes D, Cochrane A, Barnes-Holmes Y, Stewart I, McHugh L. Psychological acceptance: Experimental analyses and theoretical interpretations. International Journal of Psychology & Psychological Therapy. 2004;4:517–530. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Holmes D, Dymond S, Roche B, Grey I. Language and cognition. The Psychologist. 1999;12:500–504. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Holmes D, Hayes S.C. A reply to Galizio's “The abstracted operant: A review of Relational Frame Theory: A Post-Skinnerian Account of Human Language and Cognition.”. The Behavior Analyst. 2003;26:305–310. doi: 10.1007/BF03392084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Holmes D, Luciano C.M, Barnes-Holmes Y. Introductory comments to the series on relational frame theory. International Journal of Psychology & Psychological Therapy. 2004;4:177–179. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Holmes D, Regan D, Barnes-Holmes Y, Commins S, Walsh D, Stewart I, et al. Relating derived relations as a model of analogical reasoning: Reaction times and event-related potentials. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2005;84:435–451. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2005.79-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Holmes D, Staunton C, Barnes-Holmes Y, Whelan R, Stewart I, Commins S, et al. Interfacing relational frame theory with cognitive neuroscience: Semantic priming, the implicit association test, and event related potentials. International Journal of Psychology & Psychological Therapy. 2004;4:215–240. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Holmes D, Valverde M.R, Whelan R. Relational frame theory and the experimental analysis of language and cognition. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicologia. 2005;37:255–275. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Holmes Y, Barnes-Holmes D, Cullinan V. Education. In: Hayes S.C, Barnes-Holmes D, Roche B, editors. Relational frame theory: A post-Skinnerian account of human language and cognition. New York: Plenum; 2001. pp. 181–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Holmes Y, Barnes-Holmes D, McHugh L, Hayes S.C. Relational frame theory: Some implications for understanding and treating human psychopathology. International Journal of Psychology & Psychological Therapy. 2004;4:355–375. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Holmes Y, Barnes-Holmes D, Murphy C. Teaching the generic skills of language and cognition: Contributions from relational frame theory. In: Moran D.J, Malott R.W, editors. Evidence-based educational methods. London: Elsevier Science/Academic Press; 2004. pp. 277–292. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Holmes Y, Barnes-Holmes D, Roche B, Smeets P.M. Exemplar training and a derived transformation of function in accordance with symmetry. The Psychological Record. 2001a;51:287–308. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Holmes Y, Barnes-Holmes D, Roche B, Smeets P.M. Exemplar training and a derived transformation of function in accordance with symmetry: II. The Psychological Record. 2001b;51:589–603. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Holmes Y, Barnes-Holmes D, Smeets P.M, Strand P, Friman P. Establishing relational responding in accordance with more-than and less-than as generalized operant behavior in young children. International Journal of Psychology & Psychological Therapy. 2004;4:531–558. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Holmes Y, Hayes S.C, Barnes-Holmes D, Roche B. Relational frame theory: A post-Skinnerian account of human language and cognition. Advances in Child Development and Behavior. 2001;28:101–138. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2407(02)80063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berens N.M, Hayes S.C. Arbitrarily applicable comparative relations: Experimental evidence for a relational operant. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2007;40:45–71. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.7-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackledge J.T. Disrupting verbal processes: Cognitive defusion in acceptance and commitment therapy and other mindfulness-based psychotherapies. The Psychological Record. 2007;57:555–576. [Google Scholar]

- Boelens H. Accounting for stimulus equivalence: Reply to Hayes and Wilson. The Psychological Record. 1996;46:237–242. [Google Scholar]

- Bond F.W, Hayes S.C, Barnes-Holmes D. Psychological flexibility, ACT, and organizational behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 2006;26:25–54. [Google Scholar]

- Burgos J.E. Laudable goals, interesting experiments, unintelligible theorizing: A critical review of Relational Frame Theory. Behavior & Philosophy. 2003;31:19–45. [Google Scholar]

- Burgos J.E. Is relational frame theory intelligible? Acta Comportamentalia. 2004;12:53–73. [Google Scholar]

- Burgos J.E, Donahoe J.W. Structure and function in selectionism: Implications for complex behavior. In: Leslie J.C, Blackman D, editors. Experimental and applied analyses of human behavior. Reno, NV: Context Press; 2000. pp. 39–57. [Google Scholar]

- Carr J.E, Britton L.N. Citation trends of applied journals in behavioral psychology: 1981–2000. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2003;36:113–117. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciarrochi J, Robb H. Letting a little nonverbal air into the room: Insights from acceptance and commitment therapy: Part 2. Applications. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive Behavior Therapy. 2005;23:107–130. [Google Scholar]

- Ciarrochi J, Robb H, Godsell C. Letting a little nonverbal air into the room: Insights from acceptance and commitment therapy: Part 1. Philosophical and theoretical underpinnings. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive Behavior Therapy. 2005;23:79–106. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton M.C, Hayes L.J. Conceptual differences in the analysis of stimulus equivalence. The Psychological Record. 1999;49:145–161. [Google Scholar]

- Coyne L.W, Wilson K.G. The role of cognitive fusion in impaired parenting: An RFT analysis. International Journal of Psychology & Psychological Therapy. 2004;4:469–486. [Google Scholar]

- Critchfield T.S. Evaluating the function of applied behavior analysis: A bibliometric analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2002;35:423–426. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2002.35-423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullinan V.A, Barnes-Holmes D, Smeets P.M. A precursor to the relational evaluation procedure: Analyzing stimulus equivalence II. The Psychological Record. 2000;50:467–492. [Google Scholar]

- Cullinan V.A, Barnes-Holmes D, Smeets P.M. A precursor to the relational evaluation procedure: Searching for the contextual cues that control equivalence responding. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2001;76:339–349. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2001.76-339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Mey H.R.A. Two psychologies: Cognitive versus contingency-oriented. Theory & Psychology. 2003;13:695–709. [Google Scholar]

- Devany J.M, Hayes S.C, Nelson R.O. Equivalence class formation in language-able and language-disabled children. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1986;46:243–257. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1986.46-243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon M.R, Dymond S, Rehfeldt R.A, Roche B, Zlomke K.R. Terrorism and relational frame theory. Behavior and Social Issues. 2003;12:129–147. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon M.R, Small S.L, Rosales R. Extended analysis of empirical citations with Skinner's Verbal Behavior: 1984–2004. The Behavior Analyst. 2007;30:197–209. doi: 10.1007/BF03392155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon M.R, Zlomke K.M. Using the precursor to the relational evaluation procedure (pREP) to establish the relational frames of sameness, opposition, and distinction. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicologia. 2005;37:305–316. [Google Scholar]

- Dougher M.J. This is not B. F. Skinner's behavior analysis: A review of Hayes, Strosahl, and Wilson's Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2002;35:323–336. [Google Scholar]

- Dougher M.J, Hamilton D.A, Fink B.C, Harrington J. Transformation of the discriminative and eliciting functions of generalized relational stimuli. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2007;88:179–197. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2007.45-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougher M, Perkins D.R, Greenway D, Koons A, Chiasson C. Contextual control of equivalence-based transformation of functions. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2002;78:63–93. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2002.78-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dymond S. The next generation: Authorship trends in the experimental analysis of human behavior (1980–1999). Experimental Analysis of Human Behavior Bulletin. 2002;20:1–8. doi: 10.1007/BF03392034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dymond S. Learning across the life span: A review of Child and Adolescent Development: A Behavioral Systems Approach. Infant and Child Development. 2005;14:430–432. [Google Scholar]

- Dymond S, Alonso-Alvarez B. The selective impact of Skinner's Verbal Behavior on empirical research: A reply to Schlinger (2008). The Psychological Record in press [Google Scholar]

- Dymond S, Barnes D. A transformation of self-discrimination response functions in accordance with the arbitrarily applicable relations of sameness, more than, and less than. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1995;64:163–184. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1995.64-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dymond S, Barnes D. A transformation of self-discrimination response functions in accordance with the arbitrarily applicable relations of sameness and opposition. The Psychological Record. 1996;46:271–300. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1995.64-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dymond S, Barnes D. The effects of prior equivalence testing and detailed verbal instructions on derived self-discrimination transfer: A follow-up study. The Psychological Record. 1998;48:147–170. [Google Scholar]

- Dymond S, Critchfield T.S. Neither dark age nor renaissance: Research and authorships trends in the experimental analysis of human behavior (1980–1999). The Behavior Analyst. 2001;24:241–253. doi: 10.1007/BF03392034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dymond S, O'Hora D, Whelan R, O'Donovan A. Citation analysis of Skinner's Verbal Behavior: 1984–2004. The Behavior Analyst. 2006;29:75–88. doi: 10.1007/BF03392118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dymond S, Rehfeldt R. Understanding complex behavior: The transformation of stimulus functions. The Behavior Analyst. 2000;23:239–254. doi: 10.1007/BF03392013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dymond S, Roche B, Barnes-Holmes D. The continuity strategy, human behavior, and behavior analysis. The Psychological Record. 2003;53:333–347. [Google Scholar]

- Dymond S, Roche B, Forsyth J.P, Whelan R, Rhoden J. Transformation of avoidance response functions in accordance with same and opposite relational frames. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2007;88:249–262. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2007.22-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dymond S, Roche B, Forsyth J.P, Whelan R, Rhoden J. Derived avoidance learning: Transformation of avoidance response functions in accordance with same and opposite relational frames. The Psychological Record. 2008;58:271–288. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2007.22-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dymond S, Roche B, Rehfeldt R.A. Relational frame theory and the transformation of stimulus function. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicologia. 2005;37:291–303. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis A. Can rational-emotive behavior therapy (REBT) and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) resolve their differences and be integrated? Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive Behavior Therapy. 2005;23:153–168. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher L, Hayes S.C. Relational frame theory, acceptance and commitment therapy, and a functional analytic definition of mindfulness. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive Behavior Therapy. 2005;23:315–336. [Google Scholar]

- Fox E.J. Clarifying functional contextualism: A reply to commentaries. Educational Technology Research and Development. 2006;54:61–64. [Google Scholar]

- Frank A.J. Review of Relational Frame Theory: A Post-Skinnerian Account of Human Language and Cognition. Pragmatics & Cognition. 2004;12:169–177. [Google Scholar]

- Friman P.C, Hayes S.C, Wilson K.G. Why behavior analysts should study emotion: The example of anxiety. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1998;31:137–156. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1998.31-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galizio M. The abstracted operant: A review of Relational Frame Theory: A Post-Skinnerian Account of Human Language and Cognition. The Behavior Analyst. 2003;26:159–169. doi: 10.1007/BF03392084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galizio M. Relational frames: Where do they come from? A comment on Barnes-Holmes and Hayes (2003). The Behavior Analyst. 2004;27:107–112. doi: 10.1007/BF03392096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Y.A. Relational frame theory: A post-Skinnerian account of human language and cognition. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicologia. 2003;35:99–100. [Google Scholar]

- Garfield E. Citation analysis as a tool in journal evaluation. Science. 1972;178:471–479. doi: 10.1126/science.178.4060.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin A, Roche B, Ruiz M.R. Competing contingencies over derived relational responding: A behavioral model of the implicit association test. The Psychological Record. 2008;58:427–441. [Google Scholar]

- Giurfa M, Zhang S, Jenett A, Menzel R, Srinivasan M.V. The concepts of “sameness” and “difference” in an insect. Nature. 2001;410:930–933. doi: 10.1038/35073582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez S, Barnes-Holmes D, Luciano M.C. Generalized break equivalence I. The Psychological Record. 2001;51:131–150. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez S, Lopez F, Martin C.B, Barnes-Holmes Y, Barnes-Holmes D. Exemplar training and a derived transformation of functions in accordance with symmetry and equivalence. The Psychological Record. 2007;57:273–293. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Martin S, Lopez-Rios F, Mesa-Manjon H. Relational frame theory: Some implications for psychopathology and psychotherapy. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology. 2007;7:491–507. [Google Scholar]

- Gross A, Fox E.J. Relational frame theory: An overview of the controversy. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2009;25:87–98. doi: 10.1007/BF03393073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas J.R, Hayes S.C. When knowing you are doing well hinders performance: Exploring the interaction between rules and feedback. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 2006;26:91–111. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C. Developing a theory of derived stimulus relations. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1996;65:309–311. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1996.65-309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C. Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory, and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies. Behavior Therapy. 2004a;35:639–665. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C. Fleeing from the elephant: Language, cognition and post-Skinnerian behavior analytic science. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 2004b;24:155–173. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C. Stability and change in cognitive behavior therapy: Considering the implications of ACT and RFT. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive Behavior Therapy. 2005;23:131–151. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C. Mindfulness from the bottom up: Providing an inductive framework for understanding mindfulness processes and their application to human suffering. Psychological Inquiry. 2007;18:242–248. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C. Climbing our hills: A beginning conversation on the comparison of acceptance and commitment therapy and traditional cognitive behavioral therapy. Clinical Psychology-Science and Practice. 2008;15:286–295. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C, Barnes D. Analyzing derived stimulus relations requires more than the concept of stimulus class. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1997;68:235–244. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1997.68-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C, Barnes-Holmes D. Relational operants: Processes and implications: A response to Palmer's review of relational frame theory. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2004;82:213–224. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2004.82-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C, Barnes-Holmes D, Roche B, editors. Relational frame theory: A post-Skinnerian account of human language and cognition. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C, Barnes-Holmes D, Roche B. Behavior analysis, relational frame theory, and the challenge of human language and cognition: A reply to the commentaries on Relational Frame Theory: A Post-Skinnerian Account of Human Language and Cognition. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2003;19:39–54. doi: 10.1007/BF03392981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C, Berens N.M. Why relational frame theory alters the relationship between basic and applied behavioral psychology. International Journal of Psychology & Psychological Therapy. 2004;4:341–353. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C, Bunting K, Herbst S, Bond F.W, Barnes-Holmes D. Expanding the scope of organizational behavior management: Relational frame theory and the experimental analysis of complex human behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 2006;26:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C, Fox E, Gifford E.V, Wilson K.G, Barnes-Holmes D, Healy O. Derived relational responding as learned behavior. In: Hayes S.C, Barnes-Holmes D, Roche B, editors. Relational frame theory: A post-Skinnerian account of language and cognition. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 2001. pp. 21–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C, Gifford E.V, Hayes G.J. Moral behavior and the development of verbal regulation. The Behavior Analyst. 1998;21:253–279. doi: 10.1007/BF03391967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C, Hayes L.J. The verbal action of the listener as the basis for rule governance. In: Hayes S.C, editor. Rule-governed behavior: Cognition, contingencies and instructional control. New York: Plenum; 1989. pp. 153–190. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C, Hayes L.J. Verbal relations and the evolution of behavior analysis. American Psychologist. 1992;47:1383–1395. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C, Leonhard C. An alternative behavior-analytic approach to verbal behavior. Revista Mexicana de Psicologia. 1994;11:69–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C, Luoma J.B, Bond F.W, Masuda A, Lillis J. Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behaviour Research & Therapy. 2006;44:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C, Quinones R.M. Characterizing relational operants. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicologia. 2005;37((2)):277–289. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C, Strosahl K, Wilson K.G. Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. New York: Guilford; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C, Strosahl K, Wilson K.G, Bissett R.T, Pistorello J, Toarmino D, et al. Measuring experiential avoidance: A preliminary test of a working model. The Psychological Record. 2004;54:553–578. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C, Wilson K.G. Some applied implications of a contemporary behavior-analytic account of verbal events. The Behavior Analyst. 1993;16:283–301. doi: 10.1007/BF03392637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C, Wilson K.G. The role of cognition in complex human behavior: A contextualistic perspective. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1995;26:241–248. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(95)00024-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C, Wilson K.G. Criticisms of relational frame theory: Implications for a behavior analytic account of derived stimulus relations. The Psychological Record. 1996;46:221–236. [Google Scholar]

- Healy O, Barnes D, Smeets P.M. Derived relational responding as an operant: The effects of between-session feedback. The Psychological Record. 1998;48:511–536. [Google Scholar]

- Healy O, Barnes-Holmes D, Smeets P.M. Derived relational responding as generalized operant behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2000;74:207–227. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2000.74-207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez A, Garcia Y.A. Preliminary considerations to the study of relational frames. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicologia. 2005;37:243–254. [Google Scholar]

- Higuera J.A.G. Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) as a cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) development. Revista de Psicologia y Psicopedagogia. 2006;5:287–304. [Google Scholar]

- Hineline P.N. How, then, shall we characterize this elephant? Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1997;68:297–300. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1997.68-297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden B. Acceptance and commitment therapy: A behavior analytic psychotherapy. Tidsskrift for Norsk Psykologforening. 2007;44:1118–1126. [Google Scholar]

- Horne P.J, Lowe C.F. On the origins of naming and other symbolic behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1996;65:185–241. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1996.65-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne P.J, Lowe C.F. Toward a theory of verbal behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1997;68:271–296. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1997.68-271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingvarsson E.T, Morris E.K. Post-Skinnerian, post-Skinner, or neo-Skinnerian? Hayes, Barnes-Holmes, and Roche's Relational Frame Theory. The Psychological Record. 2004;54:497–504. [Google Scholar]

- Jesus M, Garcia M, Gomez-Becerra I, Chavez-Brown M, Greer D. Perspective taking and theory of the mind: Conceptual and empirical issues. A complementary and pragmatic proposal. Salud Mental. 2006;29:11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kanter J.W, Baruch D.E, Gaynor S.T. Acceptance and commitment therapy and behavioral activation for the treatment of depression: Description and comparison. The Behavior Analyst. 2006;29:161–185. doi: 10.1007/BF03392129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanter J.W, Busch A.M, Weeks C.E, Landes S.J. The nature of clinical depression: Symptoms, syndromes, and behavior analysis. The Behavior Analyst. 2008;31:1–21. doi: 10.1007/BF03392158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanter J.W, Parker C.R, Kohlenberg R.J. Finding the self: A behavioral measure and its clinical implications. Psychotherapy. 2001;38:198–211. [Google Scholar]

- Leigland S. Is a new definition of verbal behavior necessary in light of derived relational responding? The Behavior Analyst. 1997;20:3–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03392757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leydesdorff L. How are new citation-based journal indicators adding to the bibliometric toolbox? Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 2009;60:1327–1336. [Google Scholar]

- Lillis J, Hayes S.C. Applying acceptance, mindfulness, and values to the reduction of prejudice: A pilot study. Behavior Modification. 2007;31:389–411. doi: 10.1177/0145445506298413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez C.A, Munoz A, Ballesteros B.P. Changing socio-verbal context in women at risk of developing alimentary problems: A relational frame approach. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicologia. 2005;37:359–378. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez F, Javier C. Private events: A conceptual reconstruction. Apuntes de Psicologia. 2003;21:157–176. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe C.F, Horne P.J. Reflections on naming and other symbolic behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1996;65:315–353. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1996.65-315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luciano M.C, Becerra I.G, Valverde M.R. The role of multiple-exemplar training and naming in establishing derived equivalence in an infant. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2007;87:349–365. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2007.08-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luciano M.C, Herruzo J, Barnes-Holmes D. Generalization of say-do correspondence. The Psychological Record. 2001;51:111–130. [Google Scholar]

- Malone J.C. Advances in behaviorism: It's not what it used to be. Journal of Behavioral Education. 2003;12:85–89. [Google Scholar]

- Malott R.W. Behavior analysis and linguistic productivity. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2003;19:11–18. doi: 10.1007/BF03392978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcon-Dawson A, Vicars S.M, Miguel C.F. Publication trends in The Analysis of Verbal Behavior: 1999–2008. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2009;25:123–132. doi: 10.1007/BF03393076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marr M.J. Relational frame theory: A post-Skinnerian account of human language and cognition. Contemporary Psychology APA Review of Books. 2003;48:526–529. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez O.G, Soriano C.L. A study of pain in the perspective of verbal behavior: From the contributions of W. E. Fordyce to relational frame theory (RFT). International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology. 2006;6:169–188. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh L, Barnes-Holmes Y, Barnes-Holmes D. Perspective-taking as relational responding: A developmental profile. The Psychological Record. 2004a;54:115–144. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh L, Barnes-Holmes Y, Barnes-Holmes D. Relational frame account of the development of complex cognitive phenomena: Perspective-taking, false belief understanding, and deception. International Journal of Psychology & Psychological Therapy. 2004b;4:303–324. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh L, Barnes-Holmes Y, Barnes-Holmes D, Stewart I. Understanding false belief as generalized operant behavior. The Psychological Record. 2006;56:341–364. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh L, Barnes-Holmes Y, Barnes-Holmes D, Stewart I, Dymond S. Deictic relational complexity and the development of deception. The Psychological Record. 2007;57:517–531. [Google Scholar]

- McIlvane W.J. A stimulus in need of a response: A review of Relational Frame Theory: A Post-Skinnerian Account of Human Language and Cognition. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2003;19:29–37. doi: 10.1007/BF03392980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merwin R.M, Wilson K.G. Preliminary findings on the effects of self-referring and evaluative stimuli on stimulus equivalence class formation. The Psychological Record. 2005;55:561–575. [Google Scholar]

- Michael J, Malott R.W. Michael and Malott's dialogue on linguistic productivity. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2003;19:115–118. doi: 10.1007/BF03392985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minster S.T, Jones M, Elliffe D, Muthukumaraswamy S.D. Stimulus equivalence: Testing Sidman's (2000) theory. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2006;85:371–391. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2006.15-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore J. Thinking about thinking and feeling about feeling. The Behavior Analyst. 2000;23:45–56. doi: 10.1007/BF03391998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosticoni R. Identity: The functions of self. Acta Comportamentalia. 2007;15:71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy C, Barnes-Holmes D, Barnes-Holmes Y. Derived manding in children with autism: Synthesizing Skinner's Verbal Behavior with relational frame theory. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2005;38:445–462. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.97-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myles S.M. Understanding and treating loss of sense of self following brain injury: A behavior analytic approach. International Journal of Psychology & Psychological Therapy. 2004;4:487–504. [Google Scholar]

- Neziroglu F, Khemlani-Patel S, Veale D. Social learning theory and cognitive behavioral models of body dysmorphic disorder. Body Image. 2008;5:28–38. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ninness C, Rumph R, McCuller G, Harrison C, Ford A.M, Ninness S.K. A functional analytic approach to computer-interactive mathematics. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2005;38:1–22. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.2-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northup J, Vollmer T.R, Serrett K. Publication trends in 25 years of the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1993;26:527–537. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1993.26-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hora D, Barnes-Holmes D. Instructional control: Developing a relational frame analysis. International Journal of Psychology & Psychological Therapy. 2004;4:263–284. [Google Scholar]

- O'Hora D, Barnes-Holmes D, Roche B, Smeets P.M. Derived relational networks and control by novel instructions: A possible model of generative verbal responding. The Psychological Record. 2004;54:437–460. [Google Scholar]

- O'Hora D, Maglieri K.A. Goal statements and goal-directed behavior: A relational frame account of goal setting in organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 2006;25:131–170. [Google Scholar]

- O'Hora D, Pelaez M, Barnes-Holmes D, Rae G, Robinson K, Chaudhary T. Temporal relations and intelligence: Correlating relational performance with performance on the WAIS-II. The Psychological Record. 2008;58:569–583. [Google Scholar]

- O'Hora D, Roche B, Barnes-Holmes D, Smeets P.M. Response latencies to multiple derived stimulus relations: Testing two predictions of relational frame theory. The Psychological Record. 2002;52:51–75. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne J.G. Beyond Skinner? A review of Relational Frame Theory: A Post-Skinnerian Account of Human Language and Cognition. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2003;19:19–27. doi: 10.1007/BF03392979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Toole C, Murphy C, Barnes-Holmes D. Teaching flexible, intelligent, and creative behavior. In: Rehfeldt R.A, Barnes-Holmes Y, editors. Derived relational responding: Applications for learners with autism and other developmental disabilities. Oakland, CA: Context Press/New Harbinger; 2009. pp. 353–372. [Google Scholar]

- Paez-Blarrina M, Luciano M.C, Gutiérrez-Martínez O, Valdivia S, Rodríguez-Valverde M, Ortega J. Coping with pain in the motivational context of values: Comparison between an acceptance-based and a cognitive control-based protocol. Behavior Modification. 2008;32:403–422. doi: 10.1177/0145445507309029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer D.C. Data in search of a principle: A review of Relational Frame Theory: A Post-Skinnerian Account of Human Language and Cognition. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2004a;81:189–204. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2004.81-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer D.C. Generic response classes and relational frame theory: Response to Hayes and Barnes-Holmes. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2004b;82:225–234. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2004.82-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul H.A. Relational Frame Theory: A Post-Skinnerian Account of Human Language and Cognition [Review]. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2004;11:337–339. [Google Scholar]

- Pelaez M, Moreno R. A taxonomy of rules and their correspondence to rule-governed behavior. Revista Mexicana de Analisis de la Conducta. 1998;24:197–214. [Google Scholar]

- Pena-Correall T.E. B. F. Skinner's Verbal Behavior: 1957–2007. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicologia. 2007;39:653–661. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Gonzalez L.A, Alonso-Alvarez B. Common control by compound samples in conditional discriminations. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2008;90:81–101. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2008.90-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Gonzalez L.A, Martinez H. Control by contextual stimuli in novel second-order conditional discriminations. The Psychological Record. 2007;57:117–143. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Gonzalez L.A, Serna R.W. Transfer of specific contextual functions to novel conditional discriminations. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2003;79:395–408. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2003.79-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petursdottir A.I, Peterson S.P, Peters A.C. A quarter century of The Analysis of Verbal Behavior: An analysis of impact. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2009;25:109–121. doi: 10.1007/BF03393075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza C. JABA and the impact factor. 2009. May, Presentation at the annual convention of the Association for Behavior Analysis International, Phoenix. [Google Scholar]

- Rehfeldt R, Dillen J.E, Ziomek M.M, Kowalchuk R.K. Assessing relational learning deficits in perspective taking in children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. The Psychological Record. 2007;57:23–47. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly T, Whelan R, Barnes-Holmes D. The effect of training structure on the latency of responses to a five-term linear chain. The Psychological Record. 2005;55:233–249. [Google Scholar]

- Robb H, Ciarrochi J. Some final, gulp, “words” on REBT, ACT & RFT. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive Behavior Therapy. 2005;23:169–173. [Google Scholar]

- Roche B, Barnes D. Arbitrarily applicable relational responding and sexual categorization: A critical test of the derived difference relation. The Psychological Record. 1996;46:451–475. [Google Scholar]

- Roche B, Barnes D. A transformation of respondently conditioned stimulus function in accordance with arbitrarily applicable relations. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1997;67:275–301. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1997.67-275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche B, Barnes D. The experimental analysis of human sexual arousal: Some recent developments. The Behavior Analyst. 1998;21:37–52. doi: 10.1007/BF03392779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche B, Barnes-Holmes D. Behavior analysis and social constructionism: Some points of contact and departure. The Behavior Analyst. 2003;26:215–231. doi: 10.1007/BF03392077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche B, Barnes-Holmes D, Smeets P.M, Barnes-Holmes Y, McGeady S. Contextual control over the derived transformation of discriminative and sexual arousal functions. The Psychological Record. 2000;50:267–291. [Google Scholar]

- Roche B, Barnes-Holmes Y, Barnes-Holmes D, Stewart I, O'Hora D. Relational frame theory: A new paradigm for the analysis of social behavior. The Behavior Analyst. 2002;25:75–91. doi: 10.1007/BF03392046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche B, Dymond S. A transformation of functions in accordance with the nonarbitrary relational properties of sexual stimuli. The Psychological Record. 2008;58:71–94. [Google Scholar]

- Roche B.T, Kanter J.W, Brown K.R, Dymond S, Fogarty C.C. A comparison of “direct” versus “derived” extinction of avoidance responding. The Psychological Record. 2008;58:443–464. [Google Scholar]

- Routier C.P. Relational frame theory (RFT) and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT): Emperor's tailors or knights of the Holy Grail? Acta Comportamentalia. 2007;15:45–69. [Google Scholar]

- Salzinger K. On the verbal behavior of Relational Frame Theory: A Post-Skinnerian Account of Human Language and Cognition. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2003;19:7–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03392977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders R.R. From review to commentary on Roche and Barnes: Toward a better understanding of equivalence in the context of relational frame theory. The Psychological Record. 1996;46:477–487. [Google Scholar]

- Sautter R.A, LeBlanc L.A. The empirical applications of Skinner's analysis of verbal behavior with humans. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2006;22:35–48. doi: 10.1007/BF03393025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabani D.B, Carr J.E, Petursdottir A.I, Esch B.E, Gillet J.N. Scholarly productivity in behavior analysis: The most prolific authors and institutions from 1992 to 2001. The Behavior Analyst Today. 2004;5:235–243. [Google Scholar]

- Sidman M. Equivalence relations and behavior: A research story. Boston: Authors Cooperative; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Sidman M. Equivalence relations and the reinforcement contingency. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2000;74:127–146. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2000.74-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidman M. Symmetry and equivalence relations in behavior. Cognitive Studies. 2008;15:322–332. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. Verbal behavior. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. About behaviorism. London: Penguin; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Soriano C.L, Martinez O.G, Valverde M.R. Analyzing the verbal contexts in experiential avoidance disorder and in acceptance and commitment therapy. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicologia. 2005;37:333–358. [Google Scholar]

- Spradlin J.E. Alternative theories of the origin of derived stimulus relations. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2003;19:3–6. doi: 10.1007/BF03392976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele D, Hayes S.C. Stimulus equivalence and arbitrarily applicable relational responding. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1991;56:519–555. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1991.56-519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stemmer N. Do we need an alternative theory of verbal behavior?: A reply to Hayes and Wilson. The Behavior Analyst. 1995;18:357–362. doi: 10.1007/BF03392724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart I, Barnes-Holmes D. Understanding metaphor: A relational frame perspective. The Behavior Analyst. 2001;24:191–199. doi: 10.1007/BF03392030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart I, Barnes-Holmes D. Relational frame theory and analogical reasoning: Empirical investigations. International Journal of Psychology & Psychological Therapy. 2004;4:241–262. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart I, Barnes-Holmes D, Barnes-Holmes Y, Bond F.W, Hayes S.C. Relational frame theory and industrial/organizational psychology. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 2006;26:55–90. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart I, Barnes-Holmes D, Roche B. A functional-analytic model of analogy using the relational evaluation procedure. The Psychological Record. 2004;54:531–552. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart I, Barnes-Holmes D, Roche B, Smeets P.M. Generating derived relational networks via the abstraction of common physical properties: A possible model of analogical reasoning. The Psychological Record. 2001;51:381–408. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart I, Barnes-Holmes D, Roche B, Smeets P.M. A functional-analytic model of analogy: A relational frame analysis. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2002a;78:375–396. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2002.78-375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart I, Barnes-Holmes D, Roche B, Smeets P.M. Stimulus equivalence and nonarbitrary relations. The Psychological Record. 2002b;52:77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart I, McElwee J. Relational responding and conditional discrimination procedures: An apparent inconsistency and clarification. The Behavior Analyst. 2009;32:309–318. doi: 10.1007/BF03392194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strand P.S, Barnes-Holmes Y, Barnes-Holmes D. Educating the whole child: Implications of behaviorism as a science of meaning. Journal of Behavioral Education. 2003;12:105–117. [Google Scholar]

- Tonneau F. Who can understand relational frame theory? A reply to Barnes-Holmes and Hayes. European Journal of Behavior Analysis. 2002;3:95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Tonneau F. Relational Frame Theory: A Post-Skinnerian Account of Human Language and Cognition [Review]. British Journal of Psychology. 2004;95:265–268. [Google Scholar]

- Tonneau F, Arreola F, Martinez A.G. Function transformation without reinforcement. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2006;85:393–405. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2006.49-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Törneke N, Luciano C.M, Salas S.V. Rule-governed behavior and psychological problems. International Journal of Psychology & Psychological Therapy. 2008;8:141–156. [Google Scholar]

- Viladarga R, Hayes S.C, Levin M.E, Muto T. Creating a strategy for progress: A contextual behavioral science approach. The Behavior Analyst. 2009;32:105–133. doi: 10.1007/BF03392178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitale A, Barnes-Holmes Y, Barnes-Holmes D, Campbell C. Facilitating responding in accordance with the relational frame of comparison: Systematic empirical analyses. The Psychological Record. 2008;58:365–390. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein J.H, Wilson K.G, Drake C.E, Kellum K.K. A relational frame theory contribution to social categorization. Behavior and Social Issues. 2008;17:40–65. [Google Scholar]

- Whelan R, Barnes-Holmes D. Empirical models of formative augmenting in accordance with the relations of same, opposite, more-than and less-than. International Journal of Psychology & Psychological Therapy. 2004a;4:285–302. [Google Scholar]

- Whelan R, Barnes-Holmes D. The transformation of consequential functions in accordance with the relational frames of same and opposite. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2004b;82:177–195. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2004.82-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan R, Barnes-Holmes D, Dymond S. The transformation of consequential functions in accordance with the relational frames of more-than and less-than. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2006;86:317–335. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2006.113-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White E, Dougher M. Criticizing the tendency for evolutionary psychologists to adopt cognitive paradigms when discussing language. International Journal of Psychology & Psychological Therapy. 2004;4:325–340. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson K.G, Hayes S.C. Why it is crucial to understand thinking and feeling: An analysis and application to drug abuse. The Behavior Analyst. 2000;23:25–43. doi: 10.1007/BF03391997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson K.G, O'Donohue W.T, Hayes S.C. Hume's psychology, contemporary learning theory, and the problem of knowledge amplification. New Ideas in Psychology. 2001;19:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Winn W. Functional contextualism in context: A reply to Fox. Educational Technology Research and Development. 2006;54:55–59. [Google Scholar]