Abstract

Sustained fructose consumption has been shown to induce insulin resistance and glucose intolerance, in part, by promoting oxidative stress. Alpha-lipoic acid (LA) is an antioxidant with insulin-sensitizing activity. The effect of sustained fructose consumption (20% of energy) on the development of T2DM and the effects of daily LA supplementation in fructose-fed University of California, Davis-Type 2 diabetes mellitus (UCD-T2DM) rats, a model of polygenic obese T2DM, was investigated. At 2 mo of age, animals were divided into three groups: control, fructose, and fructose + LA (80 mg LA·kg body wt−1·day−1). One subset was followed until diabetes onset, while another subset was euthanized at 4 mo of age for tissue collection. Monthly fasted blood samples were collected, and an intravenous glucose tolerance test (IVGTT) was performed. Fructose feeding accelerated diabetes onset by 2.6 ± 0.5 mo compared with control (P < 0.01), without affecting body weight. LA supplementation delayed diabetes onset in fructose-fed animals by 1.0 ± 0.7 mo (P < 0.05). Fructose consumption lowered the GSH/GSSG ratio, while LA attenuated the fructose-induced decrease of oxidative capacity. Insulin sensitivity, as assessed by IVGTT, decreased in both fructose-fed and fructose + LA-supplemented rats. However, glucose excursions in fructose-fed LA-supplemented animals were normalized to those of control via increased glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Fasting plasma triglycerides were twofold higher in fructose-fed compared with control animals at 4 mo, and triglyceride exposure during IVGTT was increased in both the fructose and fructose + LA groups compared with control. In conclusion, dietary fructose accelerates the onset of T2DM in UCD-T2DM rats, and LA ameliorates the effects of fructose by improving glucose homeostasis, possibly by preserving β-cell function.

Keywords: glucose tolerance, oxidative capacity, dyslipidemia, islet function

sustained fructose consumption has been shown to decrease insulin sensitivity, increase inflammation, and promote dyslipidemia, (18, 37–39, 44, 45) and may thereby increase the risk for development of Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Fructose has also been demonstrated to increase oxidative stress (3, 14, 15, 26, 46, 47), which may contribute to insulin resistance, islet dysfunction and the development of T2DM (10–12). Thus, we hypothesized that sustained fructose consumption would accelerate the onset of T2DM in University of California, Davis (UCD)-T2DM rats, a model of T2DM that is more similar in etiology to T2DM in humans than other existing rodent models (4).

Because of the increasing prevalence of T2DM, there is a need to identify new effective strategies for diabetes prevention, including the potential use of nutritional supplements. Alpha-lipoic acid (LA) is a widely used nutritional supplement that has antioxidant properties and other insulin-sensitizing actions (9, 13, 23, 25, 29). LA is a potent, multifunctional mitochondrial antioxidant with a unique self-regenerating capacity (1, 28, 43). LA scavenges reactive oxygen species (ROS), reduces other antioxidants such as vitamins E and C, chelates metals and repairs oxidized proteins, reduces inflammation and acts as a cofactor for mitochondrial enzymes responsible for glucose oxidation such as pyruvate dehydrogenase (29, 33). Furthermore, LA treatment has been reported to improve insulin sensitivity in rodent models (7, 25, 35, 36, 46) and in obese and diabetic humans (19, 24, 30, 31).

We hypothesized that daily LA supplementation would reduce oxidative stress and ameliorate the accelerated onset of T2DM in fructose-fed UCD-T2DM rats. Thus, we determined the time to diabetes onset and assessed oxidative status and changes of glucose tolerance, glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, and circulating lipids and hormones in three groups of UCD-T2DM rats: control (chow-fed), fructose-fed (20% of energy), and fructose + LA (20% of energy from fructose + 80 mg LA·kg body wt−1·day−1).

METHODS

Diets and animals.

The UCD-T2DM rat model was derived by crossing obese Sprague-Dawley rats prone to adult-onset obesity and insulin resistance (40, 42) with lean Zucker diabetic fatty (ZDF) rats that have intact leptin signaling, but a defect in pancreatic β-cell insulin gene transcription (17). This cross resulted in a new rat model that develops polygenic adult-onset obesity and diabetes in both sexes with animals exhibiting insulin resistance, impaired glucose tolerance, and eventual β-cell decompensation (4). These animals also demonstrate a later age of diabetes onset than other rodent models of T2DM, such as the ZDF rat, making them highly suitable for diabetes prevention studies (2, 4).

Male rats were housed in hanging wire cages in the animal facility in the Department of Nutrition at the University of California, Davis, and maintained on a 12:12-h light-dark cycle. Food intake and body weight were measured three times a week. Diabetes onset was defined as a fasting plasma glucose value >125 mg/dl. Animals were monitored up to 1 yr of age for T2DM onset. The experimental protocols were approved by the UCD Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Starting at 2 mo of age, male animals were divided into three groups: control (n = 23), fructose (n = 30), and fructose + LA (n = 28). Baseline body weights were 358 ± 4 g, 358 ± 4 g, and 360 ± 4 g in control, fructose, and fructose + LA animals, respectively. All animals received a ground rodent chow diet (no. 5012, Ralston Purina, Belmont, CA) supplemented with safflower oil, such that the percent energy from fat, protein, and carbohydrate were 27%, 17%, and 56%, respectively, for all treatment groups. The fructose and fructose + LA groups received fructose at 20% of energy. LA (racemic form; 1:1 ratio of the individual enantiomers; Antibioticos, Rodano, Italy) was mixed in with the chow to provide a dose of 80 mg LA·kg body wt−1·day−1. Blood samples were collected after an overnight fast into EDTA-treated tubes each month until 8 mo of age for measurement of glucose, insulin, triglyceride (TG), adiponectin, and leptin. Twelve-hour urine samples were also collected monthly in sodium azide-treated flasks and assayed for glucose. At 3.5 mo of age, an intravenous glucose tolerance test was conducted on unanesthetized animals. Animals were fasted overnight and a 27-gauge butterfly catheter was placed in the saphenous vein for infusion of a bolus dose of 500 mg/kg body wt of a 50% dextrose solution. Blood samples were collected from the tail at 0, 5, 10, 20, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120, and 180 min after glucose administration. A subset of animals (n = 11 per group) were euthanized at 4 mo of age and tissues were collected for the analyses described below. Whole blood samples were also collected from this subset of animals at 2 and 4 mo of age for the measurement of reduced to oxidized glutathione ratio (GSH/GSSG) in erythrocytes as an index of oxidative capacity.

Pancreatic immunohistochemistry.

Pancreata were dissected under pentobarbital sodium anesthesia and placed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C and embedded in paraffin. Sections (6 μM thick) were treated with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide for 30 min, followed by 5% normal goat serum in PBS, and then immunostained following a standard protocol (48). Antibodies used were 1) monoclonal anti-insulin (Sigma I-2018; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at 6 μg/ml and 2) monoclonal anti-glucagon (Sigma G-2654) at 10 μg/ml, 4°C overnight. Detection was by the ABC Elite kit (Vectastain PK-6100; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and diaminobenzidine-H2O2 (DAB) (Vector SK-4100), and counterstained in hematoxylin. For a negative control, normal mouse IgG was substituted (015-000-002; Jackson ImmunoResearch, Bar Harbor, ME) at 10 μg/ml, and the absence of staining of islet cells was confirmed. Images were captured using a Nikon CoolScope microscope at ×20 magnification. Original images of immunostained islets were captured as 16-bit RGB JPEG files. Each full original JPEG file was globally processed with the Auto Levels function of Adobe Photoshop to adjust color balance and contrast (no other manipulations were performed on the original image files).

Pancreatic insulin extraction.

Pancreatic insulin was extracted using a combination of methods of Davidson and Haist (5), Dixit et al. (6), and Karam and Grodsky (21). Preweighed pancreas samples were minced and sonicated and then incubated overnight at 4°C in acid alcohol with aprotinin. Samples were centrifuged, and the supernatant was collected, and the pellet was washed once more with the same solution. An alcohol diethyl ether solution (38% alcohol, 62% ether) was added to the supernatants and incubated overnight at 4°C to precipitate the insulin. Samples were centrifuged, and the pellet was reconstituted in 0.01 N hydrochloric acid. Samples were analyzed for insulin content by RIA (Millipore, St. Charles, MO).

Visceral adiposity and liver and muscle TG content.

Mesenteric, subcutaneous, epididymal, and retroperitoneal adipose depots were dissected and weighed. The liver and gastrocnemius muscle were dissected and weighed, and samples of each were immediately placed in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Liver and muscle TG content was measured using the Folch method (16) for lipid extraction followed by spectrophotmetric measurement of TG content (Thermo Electron, Louisville, CO). One animal from the control group and one from the fructose group had become diabetic and started losing weight prior to euthanasia, and thus were excluded from the data set to avoid the confounding effects of weight loss on tissue TG content and adiposity.

Mesenteric adipocytes were isolated according to the method of Rodbell (32), as modified by Mueller et al. (27). Adipose tissue was minced and incubated with digestion buffer with collagenase at 37°C with gentle shaking for 30 min. The resulting cell suspension was diluted with 0.1 M HEPES-phosphate buffer and filtered through a 250-μm nylon mesh screen. The filtered cells were washed once and centrifuged at 1,000 rpm for 6 min. Immediately following centrifugation, 25 μl of packed adipocytes were added to an Accuvette containing 20 ml of Isoton (Beckman Coulter, Sykesville, MD). The Accuvette was immediately capped and gently inverted until the cells were uniformly dispersed. The Accuvette was quickly placed on the sampling platform of the MultiSizer III and a 0.5-ml aliquot was counted and sized through a 280-μm aperture. Using the Multisizer 3.51 software supplied with the Multisizer III, cells were counted and sorted into 300 size bins in a range of 12-1,200 pl. The percent of total adipocyte volume was calculated for each bin, and the maximum value was reported as the peak value.

Assays.

Plasma and urine glucose were measured using an enzymatic colorimetric assay for glucose (Thermo DMA, Louisville, CO). Plasma TG was measured using an enzymatic colorimetric assay (L-type TG H kit, Wako Chemicals, Richmond, VA). Insulin, leptin, and adiponectin were measured with rodent/rat specific RIAs (Millipore). Plasma insulin in intravenous glucose tolerance test (IVGTT) samples was measured by rat/mouse insulin ELISA (Millipore) since small blood samples were collected (∼200 μl blood per time point), preventing the use of RIA. Whole blood GSH and GSSG were measured using an enzymatic colorimetric assay (BIOXYTECH GSH/GSSG-412; Oxis Research, Portland, OR). Fasting plasma intracellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) was measured with an ELISA for rat sICAM-1 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Statistics and data analysis.

Data are presented as means ± SE. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 4.00 for Windows, GraphPad Software (San Diego, CA). Diabetes prevention was analyzed by Log-rank testing of Kaplan-Meier survival curves up to 8 mo of age since 18/19 fructose-fed animals were diabetic by this age. Longitudinal data were compared by two-factor repeated-measures ANOVA (time and treatment) followed by post hoc analysis with Bonferroni's multiple-comparison test. Mesenteric adipose weights, mesenteric adipocyte size, and tissue TG results were analyzed by one-factor ANOVA. For IVGTT data, the area under the curve was calculated and compared by one-factor ANOVA. Insulin sensitivity was calculated by dividing the slope of the glucose curve between 5 and 30 min after glucose infusion by the insulin area under the curve times 1,000. The 4 mo GSH/GSSG ratios were compared with baseline values by Student's t-test. Animals that did not complete the 8-mo time course were not included in longitudinal analyses. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Effects of fructose and LA on T2DM onset.

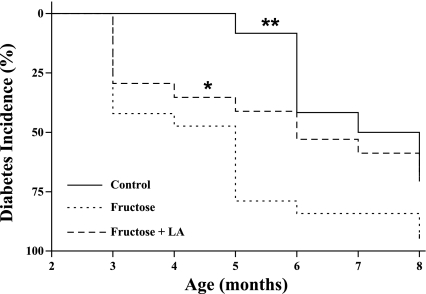

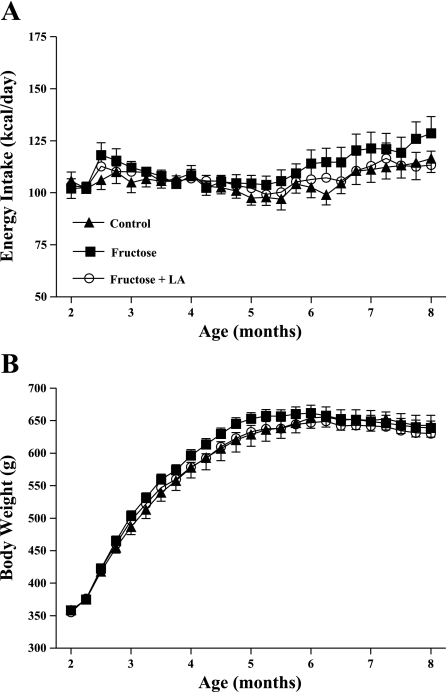

Chronic consumption of the high-fructose diet accelerated diabetes onset (P < 0.01) with fructose animals developing fasting hyperglycemia (fasting plasma glucose >125 mg/dl) 2.6 ± 0.5 mo earlier than control animals (Table 1). LA supplementation in fructose-fed rats delayed T2DM onset by 1.0 ± 0.7 mo compared with animals consuming fructose alone (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1). Despite these differences in T2DM onset, groups did not differ in energy intake or body weight (Fig. 2). At 4 mo of age, average energy intake was control = 109 ± 3 kcal/day, fructose = 108 ± 3 kcal/day, fructose + LA = 107 ± 6 kcal/day, and average body weights were control = 578 ± 16 g, fructose = 596 ± 9 g, fructose + LA = 579 ± 7 g. There was a tendency for fructose rats to have higher energy intake starting at 6 mo of age. By this age, 16 of the 19 fructose-fed animals had developed diabetes and were, therefore, developing diabetic hyperphagia. Average urine glucose values at 6 mo of age were control = 1,683 ± 650 mg/dl, fructose = 3,080 ± 723 mg/dl, fructose + LA = 1,735 ± 574 mg/dl.

Table 1.

Average ages of onset and incidence of diabetes in animals followed ≤1 yr of age

| Control | Fructose | Fructose + LA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of onset, mo | 7.4 ± 0.5 | 4.8 ± 0.5* | 5.8 ± 0.7 |

| Incidence, % | 92 | 100 | 88 |

| n | 12 | 19 | 17 |

Values are expressed as means ± SE. P < 0.05 by one-factor ANOVA;

P < 0.05 compared to control by Bonferroni's post test. LA, alpha-lipoic acid.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of diabetes incidence in control (n = 12), fructose (n = 19), and fructose + alpha-lipoic acid (LA) (n = 17) groups. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 by log-rank test compared with fructose.

Fig. 2.

Weekly mean energy intake (A) and body weight (B) in control (n = 12), fructose (n = 18), and fructose + LA (n = 16) groups. Values are expressed as means ± SE.

Effects of fructose and alpha-lipoic acid on glucose tolerance and lipids.

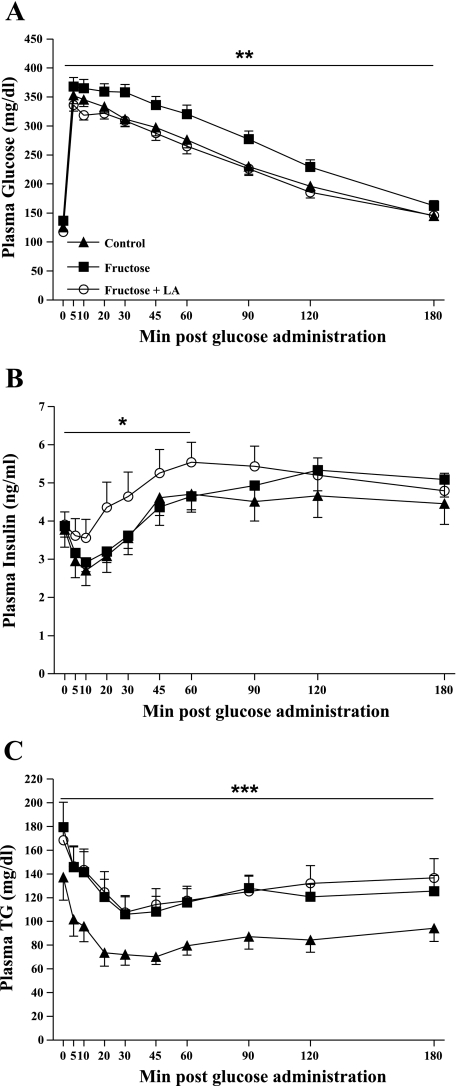

Insulin sensitivity (IS), as assessed by IVGTT, was significantly lower in fructose and fructose + LA animals compared with control animals (IS: control = −0.42 ± 0.11, fructose = −0.087 ± 0.10, fructose + LA = −0.13 ± 0.14, P < 0.05). However, fructose + LA animals were able to maintain lower glucose excursions, similar to control animals, by increasing insulin secretion in response to glucose, resulting in larger insulin excursions [area under the curve (AUC) control = 42,637 ± 1,602, fructose = 48,760 ± 2,027, fructose + LA = 41,234 ± 1,561 mg/dl × 180 min, P < 0.05 fructose compared with control and fructose + LA] (Fig. 3A). Insulin excursions between baseline and 60 min after glucose administration were higher in fructose + LA animals compared with fructose-fed animals (AUC: control = 224 ± 24, fructose = 215 ± 17, fructose + LA = 277 ± 33 ng/ml × 60 min, P < 0.05), suggestive of preservation of islet/β-cell function (Fig. 3B). TG exposure during IVGTT was increased in fructose-fed and fructose + LA groups compared with control (AUC: control = 14,929 ± 1,923, fructose = 21,680 ± 2,269, fructose + LA = 22,987 ± 2,381 mg/dl × 180 min, P < 0.05), further indicating the presence of insulin resistance in both the fructose and fructose + LA animals (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Plasma glucose (A), insulin (B), and triglycerides (TG) (C) excursions following intravenous glucose administration (500 mg/kg body wt, 50% dextrose solution) in control (n = 15), fructose (n = 20), and fructose + LA (n = 18) prediabetic rats at 3.5 mo of age. Values are expressed as means ± SE. *P < 0.05 compared with fructose, **P < 0.05 compared with control and fructose + LA, ***P <0.05 compared with control by one-factor ANOVA. For TG values, control: n = 13, fructose: n = 19, fructose + LA: n = 17.

Longitudinal measurements of metabolites and hormones.

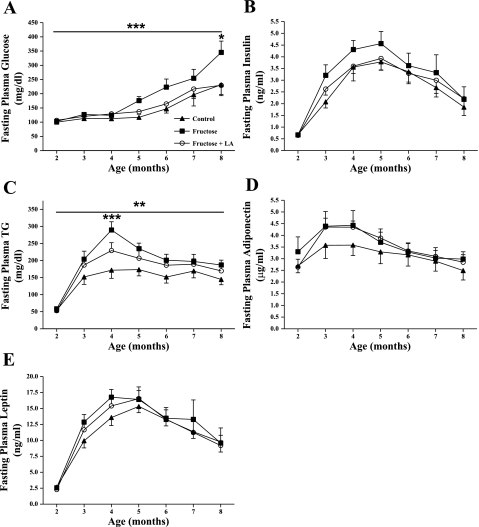

Consistent with the observed delay in T2DM onset, fasting plasma glucose concentrations were significantly higher in fructose-fed animals compared with both control and fructose + LA animals, particularly at 8 mo of age, at which time 18 of the 19 fructose animals had developed overt diabetes (Fig. 4A, P < 0.05). Fructose consumption tended to result in higher fasting plasma insulin concentrations compared with control animals, and this effect was mitigated by simultaneous LA supplementation (Fig. 4B). Fasting plasma TG concentrations were almost twofold higher in fructose-fed animals compared with control animals at 4 mo of age (P < 0.001), whereas fasting plasma TG levels only tended to be elevated in fructose + LA animals compared with control (Fig. 4C). The majority of animals in the fructose group (11 out of 19) were prediabetic at this age, demonstrating the development of fasting hypertriglyceridemia prior to T2DM onset in fructose-fed rats. There were no significant differences in fasting plasma adiponectin or leptin concentrations between treatment groups over the course of the study (Fig. 4, D and E).

Fig. 4.

Monthly fasting plasma glucose (A), insulin (B), TG (C), adiponectin (D), and leptin (E) concentrations in control (n = 12), fructose (n = 18), and fructose + LA (n = 16) aniamls. Values are expressed as means ± SE. ***P < 0.001 by Bonferroni's posttest compared with control; *P <0.05 by Bonferroni's posttest compared with control and fructose + LA (A).***P < 0.001 by two-factor repeated measures ANOVA compared with control and fructose + LA; **P < 0.001 by two-factor repeated measures ANOVA compared with control (C).

The GSH/GSSG ratio was significantly lowered compared with baseline values in fructose animals, but this ratio remained stable in both control and fructose + LA animals (%ΔGSH/GSSG from initial: control = −9 ± 15, fructose = −19 ± 4, fructose + LA = −8 ± 7) (Table 2). Fasting plasma sICAM-1 concentrations were elevated in fructose-fed and fructose + LA rats compared with control rats at 5 mo of age but did not differ between fructose + LA and fructose-fed rats (Table 3).

Table 2.

Oxidized and reduced glutathione concentrations in whole blood samples

| Control | Fructose | Fructose + LA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mo | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| GSH, μM | 2736 ± 239 | 1904 ± 148 | 2607 ± 166 | 1703 ± 113 | 2636 ± 176 | 2211 ± 125* |

| GSSG, μM | 69 ± 4 | 61 ± 4 | 71 ± 3 | 59 ± 3 | 73 ± 2 | 69 ± 3* |

| GSH/GSSG | 38 ± 3 | 31 ± 3 | 35 ± 2 | 27 ± 1** | 34 ± 2 | 31 ± 2 |

Values are expressed as means ± SE; P < 0.05 by one-factor ANOVA,

P < 0.05 compared to fructose by Bonferroni's post test and

P < 0.05 compared to baseline (2-mo) ratio by Student's t-test. Excludes animals that became diabetic and began losing weight before 4 mo of age. Control: n = 10, fructose: n = 10, fructose + LA: n = 11.

Table 3.

Fasting plasma sICAM-1 concentrations

| Two Months, ng/ml | Five Months, ng/ml | n | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 17.7 ± 0.7 | 21.3 ± 1.1 | 12 |

| Fructose | 16.9 ± 0.6 | 29.6 ± 3.6* | 19 |

| Fructose + LA | 16.8 ± 0.5 | 31.0 ± 4.0* | 17 |

Values are expressed as means ± SE. One-factor ANOVA,

P < 0.05 compared to Control by Bonferroni's post test.

Visceral adiposity and tissue TG content.

Body weight, fat depot weights, organ weight, and mesenteric adipocyte size did not differ between groups (Table 4). Liver and muscle TG content did not differ between groups but tended to be higher in the fructose + LA group.

Table 4.

Tissue weights and TG deposition, mesenteric adipocyte size, and pancreatic insulin content at 2 mo into intervention

| Control | Fructose | Fructose + LA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BW, g | 566 ± 10 | 568 ± 10 | 561 ± 10 |

| Epididymal fat, g | 9.7 ± 0.5 | 10.0 ± 0.5 | 9.9 ± 0.5 |

| Retroperitoneal fat, g | 12.7 ± 0.5 | 12.7 ± 1.1 | 11.6 ± 0.5 |

| Mesenteric fat, g | 10.4 ± 0.4 | 11.4 ± 0.7 | 10.7 ± 0.6 |

| Subcutaneous fat, g | 49 ± 3 | 50 ± 3 | 52 ± 3 |

| Total white adipose tissue, g | 82 ± 4 | 84 ± 4 | 84 ± 4 |

| Heart, g | 1.48 ± 0.03 | 1.49 ± 0.06 | 1.43 ± 0.03 |

| Kidney, g | 1.60 ± 0.04 | 1.62 ± 0.06 | 1.66 ± 0.05 |

| Liver, g | 19.1 ± 0.7 | 19.3 ± 0.8 | 20.5 ± 0.7 |

| Liver TG, mg/g | 32.7 ± 1.7 | 31.3 ± 3.4 | 42.5 ± 4.4 |

| Muscle TG, mg/g | 4.9 ± 1.2 | 3.7 ± 0.4 | 6.3 ± 1.1 |

| Peak mesenteric adipocyte size, pl | 485 ± 35 | 487 ± 21 | 531 ± 39 |

| Pancreatic insulin content, μg/g | 47 ± 9 | 45 ± 6 | 47 ± 5 |

Values are expressed as means ± SE. Control: n = 10, Fructose: n = 10, Fructose + LA: n = 11. For pancreatic insulin content, Control: n = 4, Fructose: n = 5, Fructose + LA: n = 5.

Pancreatic immunohistochemistry and insulin content.

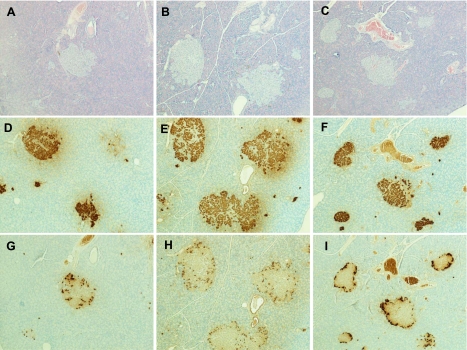

Immunostaining for insulin and glucagon was performed on a subset of six animals per group to assess islet morphology. Fig. 5 presents representative images of control, fructose-fed, and fructose + LA-treated animals. Generally, islets from control and fructose + LA-treated animals appeared to be smaller with less infiltration than islets from animals that received the high-fructose diet alone. Despite these morphologic differences, insulin content measured in pancreases from prediabetic animals killed at 4 mo of age was not different between groups (Table 3).

Fig. 5.

Representative images of pancreas sections from control, fructose-fed, and fructose + LA supplemented animals at 4 mo of age. Hematoxylin-and-eosin stain for control (A) fructose, (B) and fructose + LA (C). Anti-insulin immunostaining for control (D), fructose (E), fructose + LA animals (F). Anti-glucagon immunostaining for control (G), fructose (H), and fructose + LA (I).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated that chronic fructose consumption accelerates the onset of diabetes by reducing insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance and by promoting dyslipidemia, oxidative stress, and inflammation in UCD-T2DM rats. Furthermore, supplementation with LA in fructose-fed rats ameliorates the acceleration of diabetes onset and improves glucose tolerance, glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, and oxidative capacity, without decreasing body weight or affecting triglycerides. Together, these results are supportive of an important role for oxidative stress in the ability of fructose to hasten the onset of diabetes in UCD-T2DM rats.

The mechanism by which sustained fructose consumption reduces insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance, thus predisposing individuals to development of T2DM, is not established. It has been suggested that fructose reduces insulin sensitivity by providing a direct source of intrahepatic triglyceride via de novo lipogenesis (39, 41). Alternatively, it has also been suggested that fructose-induced hepatic insulin resistance is a product of increased hepatic stress signaling (47). Despite the observed increases of fasting plasma TG in response to fructose feeding, liver and muscle TG content were not increased in fructose-fed UCD-T2DM rats. Thus, induction of oxidative stress is a potential mechanism by which dietary fructose decreases insulin sensitivity in UCD-T2DM rats. This is supported by the observation that the GSH/GSSG ratio was significantly decreased only in the animals consuming fructose without LA supplementation. GSH is a key metabolite in the maintenance of the cellular redox state, and GSSG is its oxidized counterpart. Thus, maintaining higher GSH relative to GSSG levels is important in the protection of cell membranes from free radicals (20). The loss in oxidative capacity may, in part, explain the observed decreases of glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity in fructose-fed animals. Fructose consumption has been reported to increase production of reactive metabolites, which can activate pathways, such as c-Jun-N-terminal kinase and nuclear factor-κB pathways that result in serine phosphorylation of the insulin receptor and insulin receptor substrate proteins, resulting in decreased insulin sensitivity (12). Furthermore, the lack of a compensatory increase of the insulin response to glucose during IVGTT in the animals consuming fructose alone suggests β-cell dysfunction, which may be a result of oxidative stress at the level of the islet/β-cell (10, 11). It has been well documented that elevated circulating lipids can increase oxidative stress in β-cells and that with impaired oxidative regenerative capacity, this can lead to β-cell dysfunction and damage (11).

A role for oxidative stress in the acceleration of T2DM onset by fructose consumption in the UCD-T2DM rat is further strengthened by the effects of LA treatment in fructose-fed rats. We used a lower dose of LA to investigate the antioxidant properties of LA in the presence of fructose-induced oxidative stress, independent of its previously reported effects to decrease food intake and body weight (23, 34, 36). As in the control group, the animals consuming fructose that received supplemental LA did not exhibit a significant decrease of the GSH/GSSG ratio after 2 mo of treatment. This improvement in oxidative capacity was reflected in the IVGTT profile, as fructose + LA animals were able to maintain glucose excursions similar to control animals via increased insulin responses during the first 60 min after intravenous glucose administration, despite the presence of insulin resistance induced by chronic fructose consumption. Thus, LA supplementation appears to improve glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in fructose-fed rats. The preservation of islet function was supported by pancreatic immunohistochemistry, in which smaller islets with less infiltration were observed in control animals and fructose-fed animals receiving LA compared with the animals consuming fructose alone. Furthermore, the delay in onset in the animals supplemented with LA cannot be attributed to improved insulin sensitivity. LA has been suggested to improve insulin sensitivity by decreasing ectopic TG deposition and increasing AMP kinase expression in some studies (25, 36). However, differences in muscle or liver TG content, mesenteric adipocyte size, and circulating adiponectin concentrations were not observed in the present study. It is possible that reductions of food intake and body weight gain reported with higher doses of LA contributed to the previously observed effects of LA to improve insulin sensitivity (25, 36).

Despite the widespread use of LA, only one other study has been conducted to assess the effects of LA to prevent/delay the onset of Type 2 diabetes (36). In this study, LA supplementation completely prevented diabetes onset (compared with 78% diabetes incidence in untreated rats) in Otsuka Long-Evans Tokushima Fatty rats, a rat model in which obesity and diabetes are thought to result, in part, from a mutation in the gene encoding the CCK-A receptor (22). The present study was conducted in a rat model with polygenic adult-onset obesity and diabetes, which is more similar to the etiology of T2DM in human populations (4). Furthermore, this previous study (22) employed a substantially higher dose of LA (200 mg·kg body wt−1·day−1), which resulted in decreases of both food intake and body weight.

In summary, fructose feeding accelerates the onset of Type 2 diabetes, and concurrently decreases glucose tolerance, insulin sensitivity, and oxidative capacity compared with UCD-T2DM rats fed a standard rodent chow diet. It would also be of interest to determine whether fructose feeding accelerates diabetes onset compared with a glucose-fed control group. Supplementation with the antioxidant, LA, attenuated many of the effects of fructose consumption. This observation is supportive of a role for oxidative stress in the effects of dietary fructose to induce insulin resistance and accelerate the development of diabetes. Together, these data indicate the need for additional investigation of effects of antioxidants, such as LA, on glucose metabolism and islet/β-cell function and the prevention of T2DM (8). The potential for antioxidants to delay the onset of T2DM in human populations is important since delaying the onset of diabetes by even a few years, would similarly delay the development of complications of diabetes, including retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, and macrovascular disease.

GRANTS

The immunohistochemistry data are the result of work supported by facilities at the Veterans Affairs (VA) Puget Sound Health Care System, Seattle, Washington. Dr. Baskin is Senior Research Career Scientist, Research and Development Service, Department of VA Puget Sound Health Care System, Seattle, WA. This research was supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) through Grant AT002993. Dr. Havel's laboratory also receives support from NIH Grants R01 HL075675, R01 HL091333, AT002599, AT-002993, AT003645, and the American Diabetes Association. Immunohistochemistry work was supported by NIH National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant P30 DK-17047 through the Cellular and Molecular Imaging Core of the University of Washington Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center.

DISCLOSURES

Joseph L. Evans is a consultant for mRI, a company that distributes lipoic acid.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The immunohistochemistry work was done by the Cellular and Molecular Imaging Core, University of Washington Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center. We thank Hong-Duc Ta, Sunhye Kim, and Riva Dill for their extensive help with animal care and monitoring and Joyce Murphy for her excellent technical support with pancreas immunohistochemistry. The authors are grateful to Medical Research Institute (San Francisco, CA) and, in particular, Edward Byrd, for generously donating the lipoic acid used in this study. We thank Susan Bennett, Cheryl Phillips, and the Meyer Hall Animal Facility staff for providing excellent animal care.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arivazhagan P, Panneerselvam SR, Panneerselvam C. Effect of DL-alpha-lipoic acid on the status of lipid peroxidation and lipids in aged rats. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 58: B788–B791, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergeron R, Yao J, Woods JW, Zycband EI, Liu C, Li Z, Adams A, Berger JP, Zhang BB, Moller DE, Doebber TW. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-alpha agonism prevents the onset of type 2 diabetes in Zucker diabetic fatty rats: A comparison with PPAR gamma agonism. Endocrinology 147: 4252–4262, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cavarape A, Feletto F, Mercuri F, Quagliaro L, Daman G, Ceriello A. High-fructose diet decreases catalase mRNA levels in rat tissues. J Endocrinol Invest 24: 838–845, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cummings BP, Digitale EK, Stanhope KL, Graham JL, Baskin DG, Reed BJ, Sweet IR, Griffen SC, Havel PJ. Development and characterization of a novel rat model of type 2 diabetes mellitus: the UC Davis type 2 diabetes mellitus UCD-T2DM rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295: R1782–R1793, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davidson JK, Haist RE. A study of the levels of extractable insulin of guinea pig pancreas. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 42: 315–317, 1964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dixit PK, Lowe IP, Heggestad CB, Lazarow A. Insulin content of microdissected fetal islets obtained from diabetic and normal rats. Diabetes 13: 71–77, 1964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El Midaoui A, de Champlain J. Prevention of hypertension, insulin resistance, and oxidative stress by alpha-lipoic acid. Hypertension 39: 303–307, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evans JL. Antioxidants: do they have a role in the treatment of insulin resistance? Indian J Med Res 125: 355–372, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans JL, Goldfine ID. Alpha-lipoic acid: a multifunctional antioxidant that improves insulin sensitivity in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 2: 401–413, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans JL, Goldfine ID, Maddux BA, Grodsky GM. Are oxidative stress-activated signaling pathways mediators of insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction? Diabetes 52: 1–8, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans JL, Goldfine ID, Maddux BA, Grodsky GM. Oxidative stress and stress-activated signaling pathways: a unifying hypothesis of type 2 diabetes. Endocr Rev 23: 599–622, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evans JL, Maddux BA, Goldfine ID. The molecular basis for oxidative stress-induced insulin resistance. Antioxid Redox Signal 7: 1040–1052, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans JL, Youngren JF, Goldfine ID. Effective treatments for insulin resistance: trim the fat and douse the fire. Trends Endocrinol Metab 15: 425–431, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faure P, Rossini E, Lafond JL, Richard MJ, Favier A, Halimi S. Vitamin E improves the free radical defense system potential and insulin sensitivity of rats fed high fructose diets. J Nutr 127: 103–107, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faure P, Rossini E, Wiernsperger N, Richard MJ, Favier A, Halimi S. An insulin sensitizer improves the free radical defense system potential and insulin sensitivity in high fructose-fed rats. Diabetes 48: 353–357, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Folch J, Lees M, Sloane Stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem 226: 497–509, 1957 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griffen SC, Wang J, German MS. A genetic defect in beta-cell gene expression segregates independently from the fa locus in the ZDF rat. Diabetes 50: 63–68, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Havel PJ. Dietary fructose: implications for dysregulation of energy homeostasis and lipid/carbohydrate metabolism. Nutr Rev 63: 133–157, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacob S, Ruus P, Hermann R, Tritschler HJ, Maerker E, Renn W, Augustin HJ, Dietze GJ, Rett K. Oral administration of RAC-alpha-lipoic acid modulates insulin sensitivity in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus: a placebo-controlled pilot trial. Free Radic Biol Med 27: 309–314, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jain SK, McVie R. Hyperketonemia can increase lipid peroxidation and lower glutathione levels in human erythrocytes in vitro and in type 1 diabetic patients. Diabetes 48: 1850–1855, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karam JH, Grodsky GM. Insulin content of pancreas after sodium fluoroacetate-induce hyperglycemia. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 109: 451–454, 1962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawano K, Hirashima T, Mori S, Man ZW, Natori T. The OLETF rat. In: Animal Models of Diabetes: A Primer, edited by Sima AAF, Shafrir E. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers, 2001, p. 213–225 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim MS, Park JY, Namkoong C, Jang PG, Ryu JW, Song HS, Yun JY, Namgoong IS, Ha J, Park IS, Lee IK, Viollet B, Youn JH, Lee HK, Lee KU. Anti-obesity effects of alpha-lipoic acid mediated by suppression of hypothalamic AMP-activated protein kinase. Nat Med 10: 727–733, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Konrad T, Vicini P, Kusterer K, Hoflich A, Assadkhani A, Bohles HJ, Sewell A, Tritschler HJ, Cobelli C, Usadel KH. alpha-Lipoic acid treatment decreases serum lactate and pyruvate concentrations and improves glucose effectiveness in lean and obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 22: 280–287, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee WJ, Song KH, Koh EH, Won JC, Kim HS, Park HS, Kim MS, Kim SW, Lee KU, Park JY. Alpha-lipoic acid increases insulin sensitivity by activating AMPK in skeletal muscle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 332: 885–891, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levi B, Werman MJ. Long-term fructose consumption accelerates glycation and several age-related variables in male rats. J Nutr 128: 1442–1449, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mueller WM, Gregoire FM, Stanhope KL, Mobbs CV, Mizuno TM, Warden CH, Stern JS, Havel PJ. Evidence that glucose metabolism regulates leptin secretion from cultured rat adipocytes. Endocrinology 139: 551–558, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Packer L, Roy S, Sen CK. Alpha-lipoic acid: a metabolic antioxidant and potential redox modulator of transcription. Adv Pharmacol 38: 79–101, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Packer L, Witt EH, Tritschler HJ. alpha-Lipoic acid as a biological antioxidant. Free Radic Biol Med 19: 227–250, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pershadsingh HA. Alpha-lipoic acid: physiologic mechanisms and indications for the treatment of metabolic syndrome. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 16: 291–302, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poh Z, Goh KP. A current update on the use of alpha lipoic acid in the management of Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets 9: 392–398, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodbell M. Metabolism of isolated fat cells. I. Effects of hormones on glucose metabolism and lipolysis. J Biol Chem 239: 375–380, 1964 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shay KP, Moreau RF, Smith EJ, Smith AR, Hagen TM. Alpha-lipoic acid as a dietary supplement: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Biochim Biophys Acta 1790: 1149–1160, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shen QW, Jones CS, Kalchayanand N, Zhu MJ, Du M. Effect of dietary alpha-lipoic acid on growth, body composition, muscle pH, and AMP-activated protein kinase phosphorylation in mice. J Anim Sci 83: 2611–2617, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singh U, Jialal I. Alpha-lipoic acid supplementation and diabetes. Nutr Rev 66: 646–657, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 36.Song KH, Lee WJ, Koh JM, Kim HS, Youn JY, Park HS, Koh EH, Kim MS, Youn JH, Lee KU, Park JY. alpha-Lipoic acid prevents diabetes mellitus in diabetes-prone obese rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 326: 197–202, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stanhope KL, Griffen SC, Bair BR, Swarbrick MM, Keim NL, Havel PJ. Twenty-four-hour endocrine and metabolic profiles following consumption of high-fructose corn syrup-, sucrose-, fructose-, and glucose-sweetened beverages with meals. Am J Clin Nutr 87: 1194–1203, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stanhope KL, Havel PJ. Endocrine and metabolic effects of consuming beverages sweetened with fructose, glucose, sucrose, or high-fructose corn syrup. Am J Clin Nutr 88: 1733S–1737S, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stanhope KL, Havel PJ. Fructose consumption: potential mechanisms for its effects to increase visceral adiposity and induce dyslipidemia and insulin resistance. Curr Opin Lipidol 19: 16–24, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stanhope KL, Kras KM, Moreno-Aliaga MJ, Havel PJ. A comparison of adipocyte size and metabolism in Charles River and Harlan Sprague Dawley rats (Abstract). Obesity Res 8: 66S, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stanhope KL, Schwarz JM, Keim NL, Griffen SC, Bremer AA, Graham JL, Hatcher B, Cox CL, Dyachenko A, Zhang W, McGahan JP, Seibert A, Krauss RM, Chiu S, Schaefer EJ, Ai M, Otokozawa S, Nakajima K, Nakano T, Beysen C, Hellerstein MK, Berglund L, Havel PJ. Consuming fructose-sweetened, not glucose-sweetened, beverages increases visceral adiposity and lipids and decreases insulin sensitivity in overweight/obese humans. J Clin Invest 119: 1322–1334, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stanhope KL, Sinha M, Graham J, Havel PJ. Low circulating adiponectin levels and reduced adipocyte adiponectin production in obese, insulin-resistant Sprague-Dawley rats (Abstract). Diabetes 52: A404, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stevens MJ, Obrosova I, Cao X, Van Huysen C, Greene DA. Effects of DL-alpha-lipoic acid on peripheral nerve conduction, blood flow, energy metabolism, and oxidative stress in experimental diabetic neuropathy. Diabetes 49: 1006–1015, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Swarbrick MM, Stanhope KL, Elliott SS, Graham JL, Krauss RM, Christiansen MP, Griffen SC, Keim NL, Havel PJ. Consumption of fructose-sweetened beverages for 10 weeks increases postprandial triacylglycerol and apolipoprotein-B concentrations in overweight and obese women. Br J Nutr 100: 947–952, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thirunavukkarasu V, Anitha Nandhini AT, Anuradha CV. Effect of alpha-lipoic acid on lipid profile in rats fed a high-fructose diet. Exp Diabesity Res 5: 195–200, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thirunavukkarasu V, Anitha Nandhini AT, Anuradha CV. Lipoic acid attenuates hypertension and improves insulin sensitivity, kallikrein activity and nitrite levels in high fructose-fed rats. J Comp Physiol [B] 174: 587–592, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wei Y, Wang D, Topczewski F, Pagliassotti MJ. Fructose-mediated stress signaling in the liver: implications for hepatic insulin resistance. J Nutr Biochem 18: 1–9, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Williams DL, Schwartz MW, Bastian LS, Blevins JE, Baskin DG. Immunocytochemistry and laser capture microdissection for real-time quantitative PCR identify hindbrain neurons activated by interaction between leptin and cholecystokinin. J Histochem Cytochem 56: 285–293, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]