Abstract

Neonatal rodents deficient in medullary serotonin neurons have respiratory instability and enhanced spontaneous bradycardias. This study asks if, in Pet-1−/− mice over development: 1) the respiratory instability leads to hypoxia; 2) greater bradycardia is related to the degree of hypoxia or concomitant hypopnea; and 3) hyperthermia exacerbates bradycardias. Pet-1+/+, Pet-1+/−, and Pet-1−/− mice [postnatal days (P) 4–5, P11–12, P14–15] were held at normal body temperature (Tb) and were then made 2°C hypo- and hyperthermic. Using a pneumotach-mask system with ECG, we measured heart rate, metabolic rate (V̇o2), and ventilation. We also calculated indexes for apnea-induced hypoxia (total hypoxia: apnea incidence × O2 consumed during apnea = μl·g−1·min−1) and bradycardia (total bradycardia: bradycardia incidence × magnitude = beats missed/min). Resting heart rate was significantly lower in all Pet-1−/− animals, irrespective of Tb. At P4–5, Pet-1−/− animals had approximately four- to eightfold greater total bradycardia (P < 0.001), owing to an approximately two- to threefold increase in bradycardia magnitude and a near doubling in bradycardia incidence. Pet-1−/− animals had a significantly reduced V̇o2 at all Tb; thus there was no genotype effect on total hypoxia. At P11–12, total bradycardia was nearly threefold greater in hyperthermic Pet-1−/− animals compared with controls (P < 0.01). In both genotypes, bradycardia magnitude was positively related to the degree of hypopnea (P = 0.02), but there was no genotype effect on degree of hypopnea or total hypoxia. At P14–15, genotype had no effect on total bradycardia, but Pet-1−/− animals had up to seven times more total hypoxia (P < 0.001), owing to longer and more frequent apneas and a normalized V̇o2. We infer from these data that 1) Pet-1−/− neonates are probably not hypoxic from respiratory dysfunction until P14–15; 2) neither apnea-related hypoxia nor greater hypopnea contribute to the enhanced bradycardias of Pet-1−/− neonates from approximately P4 to approximately P12; and 3) an enhancement of a temperature-sensitive reflex may contribute to the greater bradycardia in hyperthermic Pet-1−/− animals at approximately P12.

Keywords: heart rate, apnea, body temperature, breathing, sudden infant death syndrome

bradycardias in early postnatal life are frequently associated with apnea and desaturation (1, 32, 33). Hypoxia (acting at the peripheral chemoreceptors), central mechanisms underlying apnea, and feedback from lung stretch receptors all contribute to the generation and magnitude of bradycardia accompanying respiratory disruption (9, 14, 32). The medullary serotonin (5-HT) system contributes to the reflex control of heart rate (HR), utilizing a variety of synaptic connections existing between the raphe nuclei and the nucleus of the solitary tract, nucleus ambiguous, and other aspects of the ventral medulla (34). We have previously demonstrated that the magnitude of spontaneous bradycardias is augmented until at least postnatal days (P) 11–12 in rat pups when the medullary 5-HT system is chemically lesioned shortly after birth (7). Here we extend these original observations and ask if hypoxia or greater concomitant hypopnea could contribute to bradycardia that might occur in Pet-1-deficient neonatal mice. Pet-1 is a transcription factor critical for the proper development of central 5-HT neurons, a process that begins at approximately embryonic day 11 in mice (15). As adults, these mice are missing ∼70% of their 5-HT neurons in the midbrain and brain stem (15).

The level and stability of ventilation (V̇e) in early postnatal life depends on serotonergic inputs to medullary respiratory nuclei and, more so than in adults, can be especially sensitive to changing environmental temperature [ambient temperature (Ta)]. Pet-1−/− and lmx-1b−/− mice that have reduced or absent 5-HT neurons, respectively, experience more apneas and reduced V̇e in the first few postnatal days (11, 16). Increasing Ta destabilizes neonatal breathing, in part from a concomitant rise in body temperature (Tb) and changes in metabolic drive (4, 6, 8). Given the interaction between respiratory and HR control, it is possible that, with warming, reduced and destabilized V̇e leads to more frequent, augmented bradycardias, especially in the absence of medullary 5-HT. As medullary 5-HT neurons can also influence thermogenesis (23), an influence of hypoxia on bradycardia magnitude in these animals depends, in part, on the relative influence of medullary 5-HT neurons on V̇e and metabolic rate (V̇o2).

This study addresses several novel hypotheses. First, Pet-1−/− neonates are susceptible to hypoxia in the first few postnatal days when breathing is the most unstable. Second, Pet-1−/− neonates experience augmented spontaneous bradycardia in the first week of life when hypopnea and apnea-related hypoxia are greatest. Third, mild hyperthermia will selectively augment the bradycardias of Pet-1−/− animals. These hypotheses are of particular interest because the sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) does not normally occur until the post-neonatal period (i.e., >1 mo old) and is associated with reduced medullary 5-HT (10), hyperthermia (13), bradycardia (24), and one or more preceding hypoxic events (28, 30). To address these hypotheses, we measured cardiorespiratory and metabolic variables in animals held at normal and mildly (∼2°C) hypo- and hyperthermic Tb.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Data were obtained from 51 littermates obtained from 8 different litters that originated from 8 female Pet-1+/− females paired with 4 Pet-1+/− males. Animals were studied at three postnatal ages: P4–5 (Pet-1−/−, 8; littermates, 10); P11–12 (Pet-1−/−, 7; littermates, 10), and P14–15 (Pet-1−/−, 9; littermates, 7). Dams were provided food and water ad libitum and were housed with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle at a Ta of 21–23°C. There is no difference in medullary 5-HT neuron counts between Pet-1+/+ and Pet-1+/− animals (15), so these genotypes were grouped together for analysis. All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Dartmouth College.

Genotyping.

Pups were ear-notched at each respective age. Genotyping on isolated DNA was performed according to a previous study (15) using primers: 5′-CGC ACT TGG GGG GTC ATT ATC AC-3′, 5′-CGG TGG ATG TGG AAT GTG TGC-3′, and 5′-GCC TGA TGT TCA AGG AAG ACC TCG G-3′. PCR was performed using an initial 5-min denaturing step at 95°C, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 62°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 50 s. PCR products generated were a wild-type allele and knockout allele of 209 and 361 base pairs, respectively.

Experimental setup.

Experiments were performed using a setup that allows for precise control of Tb and the accurate determination of tidal volume (Vt) in neonatal animals, where the Tb–Ta difference is very small (8). Briefly, the animal chamber (volume ∼40 ml) was constructed from a water-jacketed glass cylinder. Ta (and thus Tb) was altered by changing the temperature of the water perfusing the glass chamber. Ta and Tb changed ∼1°C/min and ∼0.2°C/min, respectively. V̇e in all animals was measured with a mask and pneumotach. The head chamber was made by fitting a section of vinyl over the end of syringe tube (volume ∼3 ml), held in place with another rubber gasket that fit into the anterior end of the chamber. The snout of the animal (fur removed) was placed into a small hole in the vinyl and sealed with polyether material (Impregum F Polyether Impression material, 3M, St. Paul, MN).

A downstream pump (AEI Technologies, Naperville, IL) connected to the outlet port of the mask pulled air through the pneumotach and mask at a flow of either 50 ml/min (P4–5), 110 ml/min (P7–8, P11–12), or 160 ml/min (P14–15). Air was pulled through a small, vertical column of Drierite (Hammond Drierite, Xenia, OH) before being analyzed for the fractional concentrations of CO2 and O2 by gas analyzers (AEI Technologies). Tb (rectal) and Ta were continually monitored with fine thermocouples (Omega Engineering, Stamford, CT). The Ta thermocouple was mounted above the animal, ∼0.5 cm displaced from the inner surface of the chamber. Both thermocouples and ECG leads exteriorized by way of a hole in a rubber gasket (Terumo Medical) in the posterior end of the chamber.

Inspiratory and expiratory airflows were detected by connecting both side-arms of the pneumotach to a differential pressure transducer (Validyne Engineering, Northridge, CA). Integration of the flow trace provided respiratory volume, calibrated by injecting and withdrawing known volumes of air (0.025, 0.05 ml) at the end of each experiment. The pneumotach responded in a linear fashion to these volumes.

Experimental protocol.

Experimentation was performed while blinded to genotype. Pups were removed from the litter and immediately weighed. To minimize heat loss, animals were held in-hand while instrumentation was performed; we limited the duration animals were exposed to room air temperature to ∼5 min. Animals were instrumented with ECG leads (contained in a small vest made from tensor bandage). A rectal thermocouple was then inserted ∼1 cm and lightly glued to the base of the tail. At this point, Tb was ∼31–32°C in younger animals and ∼33–34°C in older animals (i.e., slightly hypothermic).

P4–5, P11–12, and P14–15 mice were placed within the preheated glass chamber. Over ∼15 min, normothermic Tb was established, by adjusting Ta, at either 35 ± 0.5°C (P4–5) or 36 ± 0.5°C (P11–12 and P14–15) before recordings began. A 10-min recording of V̇e, V̇o2, and HR was then made at normothermia, after which Tb was made either 2°C hyperthermic (P4–5: ∼37°C; P11–12 and P14–15: ∼38°C) or hypothermic (P4–5: ∼33°C; P11–12 and P14–15: ∼34°C), with 10-min recordings at each new steady-state Tb. The order of the hyper- and hypothermic step was randomized and was followed immediately by the other temperature.

Data analysis.

Data are expressed as means ± SE. Ventilatory parameters reported are frequency (fB, min−1), Vt (ml/kg), and V̇e = fB × Vt (ml·min−1·kg−1). V̇o2 was calculated for all animals during room-air breathing, at all Tb, using the difference in the fractional concentrations of each gas entering and leaving the mask, multiplied by the flow rate (expressed as ml·min−1·kg−1). V̇e and V̇o2 were determined across all breaths during 5 min of breathing at each steady-state Tb. Breathing was analyzed automatically, within Labchart 6 (ADI Instruments), using peak detection to determine breath amplitude in conjunction with a slope trigger to detect the beginning of each breath and the breath duration.

Resting HR is reported in beats/min. Spontaneous bradycardias were counted and quantified if an acute drop in HR of at least 30 beats/min occurred. Rather than simply reporting the minimum HR achieved during the bradycardia, we expressed the magnitude of bradycardias as the integrated area above the HR curve (Fig. 1). This value is reported as “beats lost” [drop in HR (Hz) × duration (s)]. In this way, both the duration and fall in HR are taken into consideration for each event. In addition, we calculated a total bradycardia (beats lost/min) that represents the product of bradycardia magnitude (beats lost) and incidence (min). To determine apnea-related hypoxia, we assessed incidence of all apneas greater than two times the average respiratory period (apneas/min), regardless of when they occurred in the respiratory cycle. Importantly, respiratory disruptions where there was detectable inspiratory flow were not counted as apneas. As it is prohibitively difficult to accurately measure oxygen saturation in mouse pups weighing <5 g, we report an estimate for hypoxia occurring during the apnea (O2tot = μl O2/g) that represents the product of the apnea duration (s) and the V̇o2 before the apnea (μl O2·g−1·s−1). The key assumption we are making is that V̇o2 does not change in the period of the apnea from hypoxia or the reduced breathing (see discussion). Finally, as a measure of the total exposure to apnea-related hypoxia, we calculated a second index: total hypoxia (μl·g−1·min−1), representing the product of the apnea incidence (apneas/min) and O2tot (μl O2·g−1·apnea−1).

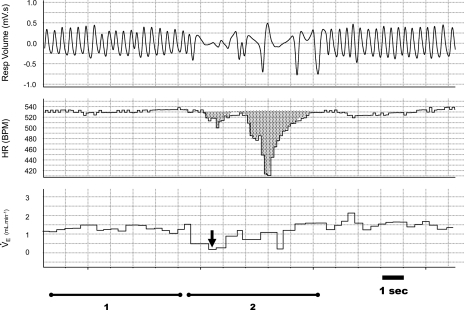

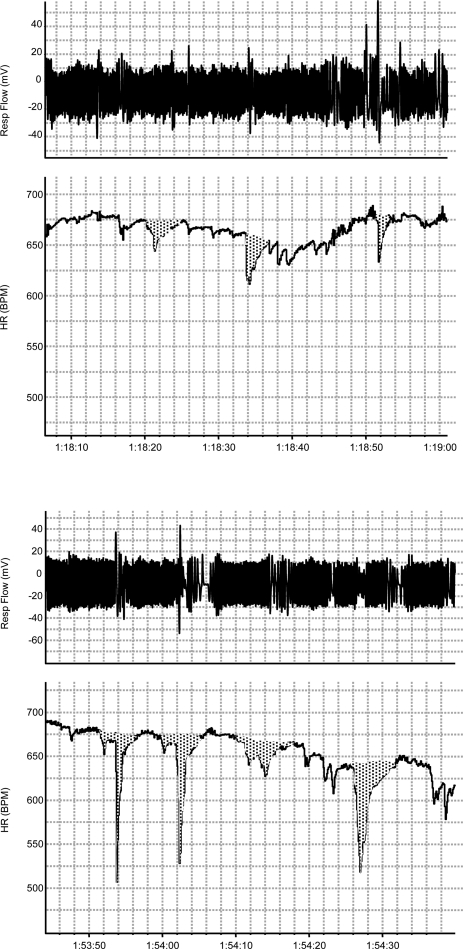

Fig. 1.

Example of a typical hypopnea and bradycardia. Respiratory volume, heart rate (HR), and ventilation (V̇e) tracings from a postnatal day 5 (P5) wild-type pup. Bradycardia magnitude was assessed by calculating the area over the HR curve. The largest fall in breath-to-breath V̇e during the bradycardia (2) was also determined (arrow) relative to the pre-event V̇e (1). BPM, beats/min.

Bradycardias in neonatal mice and rats frequently occur simultaneously with a drop in V̇e that is not an apnea (i.e., hypopnea where respiratory flow continues) (Fig. 1). For each animal, we assessed the relationship of bradycardia magnitude to maximum change in V̇e during the bradycardia (measured breath to breath). We did this by subtracting the minimum V̇e occurring during the bradycardia from the average V̇e in the ∼10 breaths preceding the bradycardia (Fig. 1). Regression analysis was performed on the average bradycardia and average hypopnea for every animal of each genotype.

Statistical analysis.

Effects of genotype and Tb on respiratory and metabolic variables were assessed using a two-factor, repeated-measures ANOVA within each age group. Tukey's post hoc tests were performed when significant effects were found. Effects were considered significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Effects of Pet-1 genotype on V̇o2 and breathing.

Given the metabolic status of newborn mice deficient in medullary 5-HT neurons had not previously been established, we were interested in measuring V̇o2 in Pet-1−/− neonates throughout the first 2 postnatal weeks. At P4–5, the V̇o2 of Pet-1−/− animals is reduced ∼25% relative to littermates, irrespective of Tb (Fig. 2A, left; P < 0.001). This relative hypometabolism is met with a proportional decrease in V̇e (Fig. 2B, left; P < 0.001) such that there is no effect of Pet-1 deficiency on the ventilatory equivalent (V̇e/V̇o2) (not shown). The relative decrease in V̇e in Pet-1−/− animals is due to reduced fB (Fig. 2C; P < 0.001) with no change in Vt (Fig. 2D). Warming is associated with a decrease in Vt (P < 0.001) and an increase in fB (P < 0.001), resulting in an increase in V̇e (P = 0.001). The effect of Tb does not depend on genotype.

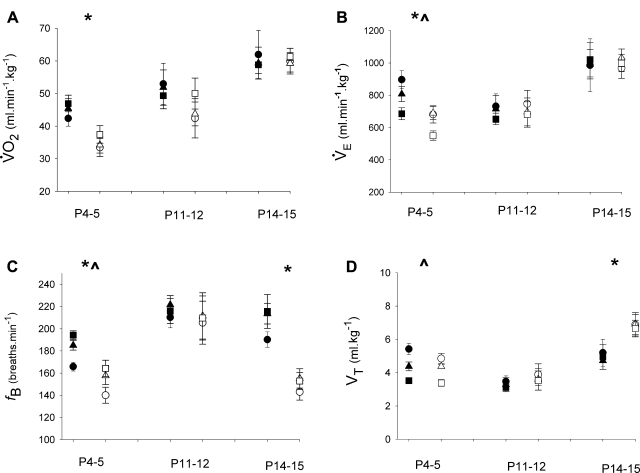

Fig. 2.

Metabolic rate (V̇o2) and V̇e of Pet-1−/− neonates and littermates throughout the first 2 postnatal weeks. V̇o2 (A), V̇e (B), and breathing frequency (fB; C) are lower in Pet-1−/− animals (open symbols, n = 8) at P4–5 compared with wild-type and heterozygous littermates (solid symbols, n = 10) at hypothermia (circles), normothermia (triangles), and hyperthermia (squares). *Genotype effect: P < 0.001. fB is also reduced in P14–15 Pet-1−/− animals (n = 9), relative to littermates (n = 7), but a relative increase in tidal volume (Vt; D) normalizes V̇e. In both genotypes, increasing body temperature (Tb) decreases V̇e, owing to a significant decrease in Vt (D). ^Tb effect: P < 0.001. Values are means ± SE.

P11–12 and P14–15 Pet-1−/− neonates have the same V̇o2 as littermates. The breathing of P11–12 Pet-1−/− animals is the same as that for littermates (Fig. 2, A–D, middle). By P14–15, however, Pet-1−/− animals again breathe more slowly (Fig. 2C; P < 0.001), but with an elevated Vt (Fig. 2D; P < 0.001) that normalizes V̇e (Fig. 2B, right). Thus, at ages beyond P4–5, Pet-1 deficiency has no effect on V̇o2 or overall V̇e.

Effects of Pet-1 genotype on the potential for apnea-related hypoxia.

Given the developmental changes in V̇o2, we reexamined apneas in Pet-1−/− animals throughout the first 2 postnatal weeks, with particular attention to the potential for apnea-related hypoxia. As accurately measuring O2 saturation was not possible in these small animals, we developed an index for the hypoxia developing during the apnea (O2tot), as well as for overall hypoxia (total hypoxia) that takes into account both O2tot and the apnea incidence.

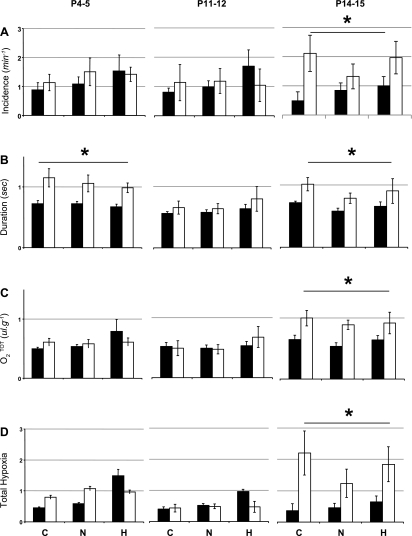

The incidence and duration of apneas in Pet-1−/− animals compared with littermates depends on postnatal age, but not Tb. P4–5 Pet-1−/− neonates have no more apneas compared with littermates (Fig. 3A, left), but their apneas are, on average, ∼50–60% longer in duration (Fig. 3B, left; P < 0.001). Owing to a reduced V̇o2 at this age, however, the apnea prolongation in Pet-1−/− animals does not translate into greater O2tot or total hypoxia compared with littermates (Fig. 3, C and D, respectively, left). The effect of Pet-1 deficiency on apnea duration resolves at P11–12 (Fig. 3B, middle), but reappears at P14–15 (P < 0.001), when apneas also become more frequent (P = 0.01) (Fig. 3, A and B, right, respectively). In addition, owing to the combined influence of apnea duration and a normal V̇o2, P14–15 Pet-1−/− animals experience, on average, an ∼50% greater O2tot (Fig. 3C, right; P = 0.003) that, along with increased apnea incidence, results in a hypoxia index that can be up to seven times greater than that of controls (Fig. 3D, right; P < 0.001).

Fig. 3.

Effect of Pet-1 genotype and Tb on apnea and potential for apnea-induced hypoxia throughout the first 2 postnatal weeks. Apnea incidence (A), duration (B), O2tot (an estimate of apnea-related hypoxia; C), and total hypoxia index (apnea incidence × O2tot; D) in P4–5, P11–12, and P14–15 Pet-1−/− animals (open bars; n = 8, 7, and 9, respectively) and wild-type and heterozygous littermates (solid bars; n = 10, 10, and 7, respectively) during hypothermia (C), normothermia (N), and hyperthermia (H) are shown. Total hypoxia is not influenced by Tb and is not significantly elevated in Pet-1−/− animals until P14–15. *Genotype effect: P < 0.01. Values are means ± SE.

Effects of Pet-1 genotype on resting HR and body size.

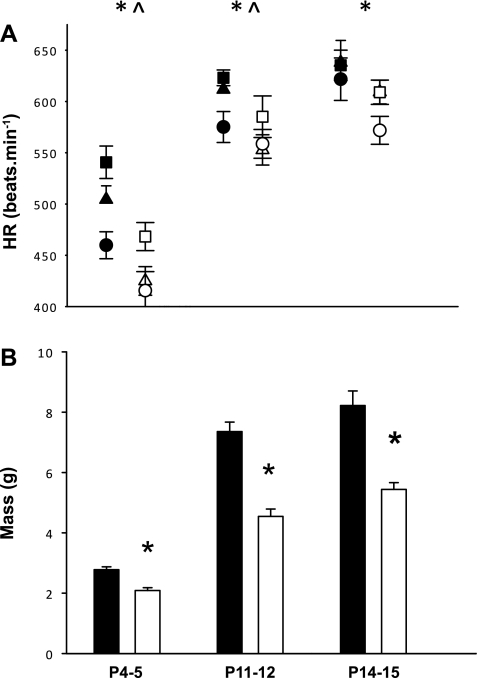

At all Tb, the HR of Pet-1−/− animals is significantly lower than that of littermates [Fig. 4A; P < 0.001 (P4–5); P = 0.002 (P11–12); P = 0.008 (P14–15)]. In animals younger than P14–15, HR increases as Tb increases [Fig. 4A; P < 0.001 (P4–5); P = 0.047 (P11–12); P = 0.17 (P14–15)]. Pet-1−/− animals are significantly smaller than littermates at all developmental time points (Fig. 4B; P < 0.001). In animals younger than P14–15, there is a significant relationship between HR and size (the relationship between size and HR at P4–5: R2 = 0.52, P < 0.001; at P11–12: R2 = 0.37, P < 0.01; at P14–15: R2 = 0.03, P = 0.54). On the other hand, there is no relationship between V̇o2 and HR in Pet-1−/− neonates (relationship between V̇o2 and HR at P4–5: R2 = 0.36, P < 0.01; at P14–15: R2 = 0.27, P = 0.04).

Fig. 4.

Pet-1−/− neonates have lower HR and are smaller throughout the first 2 postnatal weeks. A: shown are resting HR in P4–5, P11–12, and P14–15 Pet-1−/− animals (open symbols; n = 8, 7, and 9, respectively) and wild-type and heterozygous littermates (solid symbols; n = 10, 10, and 7, respectively) across development, at hypothermia (circles), normothermia (triangles), and hyperthermia (squares). B: mass of Pet-1−/− animals (open bars) and littermates (solid bars). *Genotype effect: P < 0.01; ^Tb effect: P < 0.001. Values are means ± SE.

Effects of Pet-1 genotype and Tb on the occurrence and magnitude of spontaneous bradycardias.

Pet-1−/− neonates can have qualitatively larger spontaneous bradycardias compared with wild-type littermates (Fig. 5). However, the specific influence of Pet-1 genotype on the incidence, magnitude, and temperature-sensitivity of spontaneous bradycardias depends on postnatal age. At P4–5, Pet-1−/− animals experience more bradycardias, irrespective of Tb (Fig. 6A, left; P = 0.02). The most striking effect of genotype at this age, however, is on bradycardia magnitude, with Pet-1−/− animals experiencing events that are approximately two to three times larger than those of littermates (Fig. 6B, left; P < 0.001). As a result, total bradycardia can be approximately four to eight times greater in Pet-1−/− animals compared with littermates (Fig. 6C, left; P < 0.001).

Fig. 5.

Examples of spontaneous bradycardias at P12 in a wild-type (top) and Pet-1−/− animal (bottom) at hyperthermic Tb.

Fig. 6.

Effect of Pet-1 genotype and Tb on spontaneous bradycardias throughout the first 2 postnatal weeks. Bradycardia incidence (A), magnitude (B), and total bradycardia index (incidence × magnitude) (C) in P4–5, P11–12, and P14–15 Pet-1−/− animals (open bars; n = 8, 7, and 9, respectively) and wild-type and heterozygous littermates (solid bars; n = 10, 10, and 7, respectively) are shown. Total bradycardia is significantly greater in Pet-1−/− animals compared with littermates until P12. *Genotype effect: P < 0.01. At P11–12, bradycardia magnitude is especially elevated at hyperthermic Tb (H) compared with normothermic (N) or hypothermic (C) Tb. ^Tb effect: P = 0.02.

By P11–12, Pet-1−/− animals are no longer having more frequent bradycardias than littermates (Fig. 6A, middle). However, Pet-1−/− animals continue to have larger bradycardias than littermates (Fig. 6B, middle; P = 0.03), most evident at warmer Tb (Tb effect: P = 0.02). Thus, although the overall effect of genotype at P11–12 is not as prominent as at P4–5, total bradycardia remains significantly elevated in Pet-1−/− animals (e.g., nearly ∼3 times greater than controls at hyperthermic Tb; Fig. 6C, middle; P = 0.007).

By P14–15, Pet-1−/− animals experience bradycardias at the same frequency and of the same magnitude as littermates (Fig. 6, A and B, respectively, right). As a result, unlike at younger ages, there is no significant genotype effect on total bradycardia (Fig. 6C, right).

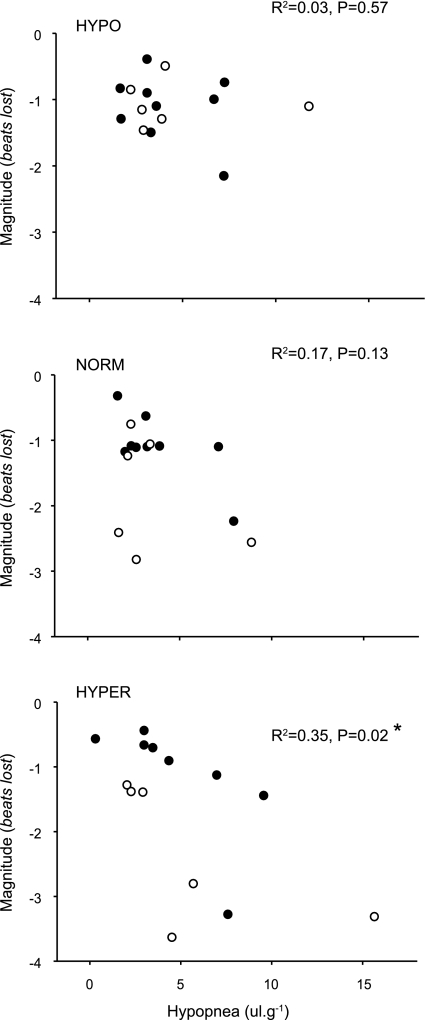

Relationship of spontaneous bradycardia magnitude to associated hypopnea.

Genotype has no effect on the magnitude of the hypopnea that occurs concomitantly with bradycardia. At P4–5, the average maximum fall in V̇e for wild-type animals is 6.8 ± 0.9, 5.3 ± 0.8, and 4.5 ± 0.5 μl/g at hypo-, normo-, and hyperthermic Tb, respectively, while Pet-1−/− animals experience a fall in V̇e of 5.2 ± 0.7, 5.3 ± 1.0, and 4.6 ± 0.5 μl/g, respectively. At P11–12, wild-type animals experience a fall in V̇e of 4.2 ± 0.8, 3.8 ± 0.8, and 4.6 ± 1.1 μl/g at hypo-, normo-, and hyperthermic Tb, respectively, while the V̇e of Pet-1−/− animals fell 4.6 ± 1.6, 3.6 ± 1.2, and 5.5 ± 2.3 μl/g, respectively.

We analyzed the relationship between the magnitude of bradycardias and the fall in V̇e (Fig. 1). At P4–5, no significant relationship exists, irrespective of Tb [R2 < 0.00, P = 0.99 (hypo); R2 < 0.001, P = 0.93 (norm); R2 = 0.08, P = 0.3 (hyper); not shown]. At P11–12, there exists a positive overall relationship between the degree of hypopnea and bradycardia magnitude, but only when animals are hyperthermic [Fig. 7, bottom (hyper): R2 = 0.35; P = 0.02].

Fig. 7.

Relationship between the degree of hypopnea and bradycardia magnitude in P11–12 Pet-1−/− mice (n = 7) and wild-type and heterozygous littermates (n = 10). While there is no relationship between the magnitude of hypopnea and bradycardia at hypothermic (top) or normothermic Tb (middle), a significant relationship exists at hyperthermic Tb (bottom, R2 = 0.35; P = 0.02). Values are means ± SE.

DISCUSSION

Previous data from our laboratory and others have demonstrated respiratory instability and a propensity for large, spontaneous bradycardias associated with these hypopneas in neonatal rodents deficient in medullary 5-HT neurons (7, 11). Our results extend these findings, suggesting that a prenatal loss of medullary 5-HT neurons not only enhances spontaneous bradycardias until P12, but also that 1) Pet-1−/− animals display respiratory instability at P4–5 and P14–15, but are only susceptible to hypoxia at P14–15, owing to a relative suppression of V̇o2 at P4–5; 2) contrary to our original hypothesis, neither greater hypoxia nor greater concomitant hypopnea explain the augmentation of bradycardias in Pet-1−/− neonates; and 3) at approximately P12, hyperthermia augments the bradycardias of both Pet-1−/− and littermates, with the largest bradycardias associated with the greatest concomitant fall in V̇e.

Pet-1 deficiency and potential for respiratory-related hypoxia over development.

Similar to other rodent models with medullary 5-HT disruption (including rat pups with pharmacological lesions, tryptophan hydroxylase−2−/− mice, and adult lmx-1b−/− mice) Pet-1−/− neonates have a lower fB and are prone to apnea (2, 7, 16, 17). Importantly, these new data suggest that P4–5 Pet-1−/− animals do not hypoventilate (and are thus not hypoxic), as their reduced fB and V̇e are matched appropriately to a reduced V̇o2. At P14–15, the fB of Pet-1−/− animals again lags behind that of littermates, suggesting the reemergence of a 5-HT-dependent defect in fB. A compensatory increase in Vt, possibly as a result of adaptation of respiratory motoneurons, normalizes overall V̇e. Why the fB of Pet-1−/− animals temporarily recovers at approximately P12 is a matter of speculation. Variability in 5-HT receptor expression may partially explain this effect. There is a transient reduction in 5-HT2 receptor expression at P12 in brain stem nuclei involved in respiratory control (22). It is possible nuclei participating in the respiratory rhythm become less reliant on medullary 5-HT during this developmental window.

P14–15 Pet-1−/− animals also experience longer, more frequent apneas compared with controls that, unlike in younger animals, result in a considerably higher total hypoxia. This persistent respiratory instability and potential hypoxia toward the end of the second postnatal week (and not in the first week) are novel findings and do not support our original hypothesis that the most hypoxia would occur along with the greatest respiratory instability. Previously, animals were only studied up until P9.5, and, with no measure of V̇o2, it was unknown whether neonates deficient in medullary 5-HT neurons were susceptible to respiratory-related hypoxia, or if this susceptibility changed with development. Our findings also underline the importance of obtaining accurate measurements of both Vt and V̇o2 in small neonatal animals, where airway resistance is high and is coupled with a small Tb–Ta difference.

HR control in Pet-1−/− mice: potential mechanisms.

While novel, our data do not support our original hypothesis that the augmented bradycardia in animals deficient in medullary 5-HT neurons is related to greater hypopnea or apnea-related hypoxia. What mechanisms could account for their lower resting HR and increased transient bradycardias? Similar to other rodent models of brain stem 5-HT deficiency (e.g., tryptophan hydroxylase−2−/−, Lmmx-1b−/−) (2, 16), Pet-1−/− mice were significantly lighter than littermates. However, a smaller size does not contribute to the cardiac phenotypes of Pet-1−/− mice because, over development, cardiac phenotypes resolve, while body mass becomes more disparate. A relatively reduced V̇o2 may be a contributing factor to the reduction in resting HR, but it is difficult to ascertain how this might contribute to the enhanced transient bradycardias. A more plausible explanation is that a reduction in medullary 5-HT neurons leads to autonomic dysfunction through a physiological effect within relevant nuclei. Not only do medullary 5-HT neurons impinge on premotor, presympathetic neurons in the ventrolateral medulla, but a significant proportion of premotor presympathetic neurons are themselves serotoninergic (19). Changes in vagal tone are also possible, as it is well established that medullary 5-HT neurons project to preganglionic vagal neurons, expressing a wide variety of 5-HT receptors (18, 34, 37). 5-HT also participates in the development of neuronal networks (5, 29). Thus an alternative possibility is that the cardiac phenotypes are owing to a developmental abnormality within premotor sympathetic, or preganglionic, parasympathetic nuclei, either directly from a lack of 5-HT, or through another downstream factor. Although 5-HT neurons begin synthesizing 5-HT almost immediately after their formation, full innervation of 5-HT targets continues until the third postnatal week in rodents (21). Hence, sympathetic, parasympathetic, and other nuclei involved in cardiorespiratory control may not be under the influence of medullary 5-HT at the same time, which could, in part, explain the variability in both cardiac and respiratory phenotypes over early postnatal life. Further research exploring autonomic dysfunction in Pet-1−/− mice and other models of medullary 5-HT deficiency is warranted.

At approximately P12, bradycardia magnitude is greater in Pet-1−/− animals, augmented by hyperthermic conditions, and positively related to the concomitant fall in V̇e. Given that the degree of hypopnea is not different between genotypes, a plausible explanation for the enhanced bradycardias in Pet-1−/− at this age is an enhancement of a temperature-dependent respiratory reflex. One possibility is the carotid chemoreflex, which is not only enhanced by mild warming (8, 12), but may also be a key contributor in early life to the bradycardia associated with apnea (14, 32). Interestingly, stimulation of the caudal raphe has been shown to mitigate the bradycardic response elicited by carotid body activation (38, 39). Alternatively, it may be that reflexes related to pulmonary stretch are enhanced, either centrally or peripherally, in Pet-1−/− animals. It has been previously demonstrated that the prevailing lung volume and hence activity of pulmonary stretch receptors can significantly influence the magnitude of chemoreflex-induced bradycardia magnitude, with greater bradycardia occurring as lung volume is reduced (3).

Methodological considerations.

A main finding of our study is that neonates deficient in 5-HT neurons are not susceptible to apnea-related hypoxia until P14–15. We acknowledge, however, that, for technical reasons, we were unable to measure O2 saturation directly. Previous data in human infants do suggest that apneas of only a few seconds (e.g., a few breaths; comparable in relative terms to apneas experienced by our P14–15 Pet-1−/− animals) can result in significant hypoxemia (<80% O2 saturation) (32). Of course, V̇o2 could be reduced during the apnea in response to hypoxia or to the reduced breathing. Alternatively, V̇o2 could increase as part of a stress response. In terms of processes that could limit hypoxemia, we feel our assumption is valid. First, it has been previously demonstrated across species that hypoxia-induced hypometabolism is an active process requiring a number of physiological adaptations, including a resetting of the Tb set-point and a downregulation of muscle activity, among others (25). These processes are more likely to occur in the order of minutes (not seconds) and are thus unlikely to occur during the short apneas we describe. The reduced breathing itself could lower energy expenditure and thus limit the fall in blood gases during the apnea. However, the cost of breathing is <1% of total V̇o2 in normoxia, so this is unlikely to have a big effect on blood gases (26). In addition, the dynamics and magnitude of oxygen desaturation during apnea are complex and are influenced by a number of additional factors, such as lung volume, hemoglobin affinity, and cardiac output (35). Because Pet-1−/− animals are smaller and have a lower resting HR, our hypoxia index may actually underestimate the degree of hypoxia they experience (35). However, as we have no measure of V̇o2 during apnea, our data should be interpreted with the above caveats in mind.

Conducting experiments on Pet-1−/− mice rather than postnatally lesioned rat pups allowed us to circumvent technical issues related to body size, allowing us to examine the control of HR and breathing in animals beyond P12. Rather than reporting the minimum HR achieved during the course of the spontaneous event [as our laboratory did in rat pups (7)], we have reported the integrated HR, i.e., the area over the HR curve, which we feel is a more physiologically relevant indicator of changes in cardiac output, resulting from bradycardia magnitude and duration. Our results in mice not only support the contention that medullary 5-HT neurons are important for the maintenance of HR in early postnatal life, but also provide the nidus for future experiments utilizing novel transgenic techniques that will further delineate the molecular mechanisms underlying the effect of medullary 5-HT on the control of HR.

Perspectives and Significance

While our data suggest that respiratory dysfunction and associated hypoxia do not explain the greater bradycardia in neonates with reduced medullary 5-HT, hypoxia alone has clear implications for neonatal mortality. SIDS is a syndrome associated with medullary 5-HT deficiency (10) and is thought to occur after one or more hypoxic events, based on evidence of brain stem gliosis, right ventricular enlargement, extramedullary hematopoeisis, and enlarged adrenal chromaffin cell mass, all of which are hallmarks of chronic hypoxemia (20, 27, 28).

There is direct evidence of bradycardia in cardiorespiratory tracings from SIDS cases (24, 31). In a background of medullary 5-HT deficiency, an augmentation of spontaneous, transient bradycardias superimposed on a background of reduced resting HR could result in inadequate perfusion of the brain and other vital organs, thereby increasing SIDS risk. This assumes there is no compensatory increase in stroke volume or adjustments to the relative perfusion of the central and peripheral vascular beds. That bradycardia in older animals is augmented by hyperthermia is of special interest, because evidence at the death scene suggests that overheating is a risk factor for SIDS (36). Our most salient finding is that, at ages past the first postnatal week, animals with reduced medullary 5-HT have bradycardia and potentially respiratory-related hypoxia. Pet-1−/− mice retain perhaps as much as 40% of their 5-HT neurons in B1 and B2 groups (15). As SIDS infants have only a partial reduction in medullary 5-HT content (10), our data, obtained from animals with a partial reduction of medullary 5-HT, are arguably relevant to the pathophysiology of SIDS. A lack of medullary 5-HT in human infants may increase the risk for SIDS in the postneonatal period (i.e., infants >1 mo old) through mechanisms related to bradycardia and chronic hypoxemia.

GRANTS

Funding for this work was provided by National Institutes of Health Grants HL-28066 and HD-36379. Support for K. J. Cummings was generously provided by the Parker B. Francis Fellowship Program.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- 1.Abu-Shaweesh JM, Martin RJ. Neonatal apnea: what's new? Pediatr Pulmonol 43: 937–944, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alenina N, Kikic D, Todiras M, Mosienko V, Qadri F, Plehm R, Boye P, Vilianovitch L, Sohr R, Tenner K, Hortnagl H, Bader M. Growth retardation and altered autonomic control in mice lacking brain serotonin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 10332–10337, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angell-James JE, Daly MD. The effects of artificial lung inflation on reflexly induced bradycardia associated with apnoea in the dog. J Physiol 274: 349–366, 1978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berterottiere D, D'Allest AM, Dehan M, Gaultier C. Effects of increase in body temperature on the breathing pattern in premature infants. J Dev Physiol 13: 303–308, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buznikov GA, Lambert HW, Lauder JM. Serotonin and serotonin-like substances as regulators of early embryogenesis and morphogenesis. Cell Tissue Res 305: 177–186, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cameron YL, Merazzi D, Mortola JP. Variability of the breathing pattern in newborn rats: effects of ambient temperature in normoxia or hypoxia. Pediatr Res 47: 813–818, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cummings KJ, Commons KG, Fan KC, Li A, Nattie EE. Severe spontaneous bradycardia associated with respiratory disruptions in rat pups with fewer brain stem 5-HT neurons. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 296: R1783–R1796, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cummings KJ, Frappell PB. Breath-to-breath hypercapnic response in neonatal rats: temperature dependency of the chemoreflexes and potential implications for breathing stability. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 297: R124–R134, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daly MB, Kirkman E. Differential modulation by pulmonary stretch afferents of some reflex cardioinhibitory responses in the cat. J Physiol 417: 323–341, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duncan JR, Paterson DS, Hoffman JM, Mokler DJ, Borenstein NS, Belliveau RA, Krous HF, Haas EA, Stanley C, Nattie EE, Trachtenberg FL, Kinney HC. Brainstem serotonergic deficiency in sudden infant death syndrome. JAMA 303: 430–437, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erickson JT, Shafer G, Rossetti MD, Wilson CG, Deneris ES. Arrest of 5HT neuron differentiation delays respiratory maturation and impairs neonatal homeostatic responses to environmental challenges. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 159: 85–101, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fadic R, Larrain C, Zapata P. Thermal effects on ventilation in cats: participation of carotid body chemoreceptors. Respir Physiol 86: 51–63, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fleming PJ, Azaz Y, Wigfield R. Development of thermoregulation in infancy: possible implications for SIDS. J Clin Pathol 45: 17–19, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henderson-Smart DJ, Butcher-Puech MC, Edwards DA. Incidence and mechanism of bradycardia during apnoea in preterm infants. Arch Dis Child 61: 227–232, 1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hendricks TJ, Fyodorov DV, Wegman LJ, Lelutiu NB, Pehek EA, Yamamoto B, Silver J, Weeber EJ, Sweatt JD, Deneris ES. Pet-1 ETS gene plays a critical role in 5-HT neuron development and is required for normal anxiety-like and aggressive behavior. Neuron 37: 233–247, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hodges M, Whener M, Aungst J, Smith JC, Richerson GB. Transgenic mice lacking serotonin neurons have severe apnea and high mortality during development. J Neurosci 29: 10341–10349, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hodges MR, Tattersall GJ, Harris MB, McEvoy SD, Richerson DN, Deneris ES, Johnson RL, Chen ZF, Richerson GB. Defects in breathing and thermoregulation in mice with near-complete absence of central serotonin neurons. J Neurosci 28: 2495–2505, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jordan D. Vagal control of the heart: central serotonergic (5-HT) mechanisms. Exp Physiol 90: 175–181, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kerman IA, Shabrang C, Taylor L, Akil H, Watson SJ. Relationship of presympathetic-premotor neurons to the serotonergic transmitter system in the rat brainstem. J Comp Neurol 499: 882–896, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kinney HC, Burger PC, Harrell FE, Jr, Hudson RP., Jr “Reactive gliosis” in the medulla oblongata of victims of the sudden infant death syndrome. Pediatrics 72: 181–187, 1983 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lidov HG, Molliver ME. Immunohistochemical study of the development of serotonergic neurons in the rat CNS. Brain Res Bull 9: 559–604, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Q, Wong-Riley MT. Postnatal changes in the expressions of serotonin 1A, 1B, and 2A receptors in ten brain stem nuclei of the rat: implication for a sensitive period. Neuroscience 165: 61–78, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Madden CJ, Morrison SF. Brown adipose tissue sympathetic nerve activity is potentiated by activation of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)1A/5-HT7 receptors in the rat spinal cord. Neuropharmacology 54: 487–496, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meny RG, Carroll JL, Carbone MT, Kelly DH. Cardiorespiratory recordings from infants dying suddenly and unexpectedly at home. Pediatrics 93: 44–49, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mortola JP. Implications of hypoxic hypometabolism during mammalian ontogenesis. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 141: 345–356, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mortola JP, Matsuoka T, Saiki C, Naso L. Metabolism and ventilation in hypoxic rats: effect of body mass. Respir Physiol 97: 225–234, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naeye RL. Brain-stem and adrenal abnormalities in the sudden-infant-death syndrome. Am J Clin Pathol 66: 526–530, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naeye RL. Hypoxemia and the sudden infant death syndrome. Science 186: 837–838, 1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pflieger JF, Clarac F, Vinay L. Postural modifications and neuronal excitability changes induced by a short-term serotonin depletion during neonatal development in the rat. J Neurosci 22: 5108–5117, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poets CF. Apparent life-threatening events and sudden infant death on a monitor. Paediatric respiratory reviews 5, Suppl A: S383–S386, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poets CF, Meny RG, Chobanian MR, Bonofiglo RE. Gasping and other cardiorespiratory patterns during sudden infant deaths. Pediatr Res 45: 350–354, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poets CF, Southall DP. Patterns of oxygenation during periodic breathing in preterm infants. Early Hum Dev 26: 1–12, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poets CF, Stebbens VA, Samuels MP, Southall DP. The relationship between bradycardia, apnea, and hypoxemia in preterm infants. Pediatr Res 34: 144–147, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramage AG. Central cardiovascular regulation and 5-hydroxytryptamine receptors. Brain Res Bull 56: 425–439, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sands SA, Edwards BA, Kelly VJ, Davidson MR, Wilkinson MH, Berger PJ. A model analysis of arterial oxygen desaturation during apnea in preterm infants. PLoS Comput Biol 5: e1000588, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sawczenko A, Fleming PJ. Thermal stress, sleeping position, and the sudden infant death syndrome. Sleep 19: S267–S270, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saxena PR, Villalon CM. Cardiovascular effects of serotonin agonists and antagonists. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 15, Suppl 7: S17–S34, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sevoz C, Callera JC, Machado BH, Hamon M, Laguzzi R. Role of serotonin 3 receptors in the nucleus tractus solitarii on the carotid chemoreflex. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 272: H1250–H1259, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weissheimer KV, Machado BH. Inhibitory modulation of chemoreflex bradycardia by stimulation of the nucleus raphe obscurus is mediated by 5-HT3 receptors in the NTS of awake rats. Auton Neurosci 132: 27–36, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]