Abstract

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is now routinely used to map the topographic organization of human visual cortex. Mapping the detailed topography of somatosensory cortex, however, has proven to be more difficult. Here we used the increased blood-oxygen-level-dependent contrast-to-noise ratio at ultra-high field (7 Tesla) to measure the topographic representation of the digits in human somatosensory cortex at 1 mm isotropic resolution in individual subjects. A “traveling wave” paradigm was used to locate regions of cortex responding to periodic tactile stimulation of each distal phalangeal digit. Tactile stimulation was applied sequentially to each digit of the left hand from thumb to little finger (and in the reverse order). In all subjects, we found an orderly map of the digits on the posterior bank of the central sulcus (postcentral gyrus). Additionally, we measured event-related responses to brief stimuli for comparison with the topographic mapping data and related the fMRI responses to anatomical images obtained with an inversion-recovery sequence. Our results have important implications for the study of human somatosensory cortex and underscore the practical utility of ultra-high field functional imaging with 1 mm isotropic resolution for neuroscience experiments. First, topographic mapping of somatosensory cortex can be achieved in 20 min, allowing time for further experiments in the same session. Second, the maps are of sufficiently high resolution to resolve the representations of all five digits and third, the measurements are robust and can be made in an individual subject. These combined advantages will allow somatotopic fMRI to be used to measure the representation of digits in patients undergoing rehabilitation or plastic changes after peripheral nerve damage as well as tracking changes in normal subjects undergoing perceptual learning.

INTRODUCTION

High resolution measurements of the somatotopic mapping of the hand in human cerebral cortex are important for understanding disturbed sensory representations in neurological disorders (Butterworth et al. 2003) and for tracking cortical re-organization in rehabilitation following peripheral nerve damage or stroke. Precise knowledge of the spatial layout of primary somatosensory cortex (S1) is also crucial for understanding how top-down influences, such as attention, modulate sensory inputs to cortex.

Penfield was the first to map human somatosensory cortex perioperatively (Penfield and Boldrey 1937). With the advent of noninvasive neuroimaging techniques, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), these early measurements are being revisited. Several fMRI studies have investigated the cortical representation of the hand using pneumatic or piezoelectric stimuli applied to the glabrous skin of the fingertips (Duncan and Boynton 2007; Francis et al. 2000; Huang and Sereno 2007; Overduin and Servos 2008; Schweizer et al. 2008; Weibull et al. 2008). However, the spatial resolution of the cortical maps produced in most of these studies is limited by the use of large voxel sizes or normalization and averaging of results across subjects (Francis et al. 2000; Gelnar et al. 1998; Kurth et al. 2000; Maldjian et al. 1999; Nelson and Chen 2008; Overduin and Servos 2008; Weibull et al. 2008).

Ultra-high magnetic field (7T) provides access to fMRI data with high-spatial resolution and high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). Resolution is particularly important when studying somatosensory cortex as maps of the body surface in S1 (even the relatively over-represented maps of the finger tips) are small, and the postcentral gyrus (PCG) is prone to significant partial volume effects (PVE) due to its large surface-to-volume ratio (Scouten et al. 2006) and narrow width (Fischl and Dale 2000) as well as the interdigitation of the pre- and postcentral gyri (White et al. 1997). Achieving high-spatial resolution generally means compromising blood-oxygenation-level-dependent (BOLD) contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR), volume coverage, or temporal resolution. Statistical power can thus become limiting at lower field, particularly for sensory tasks where the BOLD signal is low in comparison with visual and motor tasks, even with a large number of repeated measurements (Schweizer et al. 2008).

7T provides increased BOLD sensitivity (Gati et al. 1997; Van der Zwaag et al. 2009; Yacoub et al. 2001), which can be exploited to improve the spatial resolution and/or reduce the number of trials. Higher spatial specificity can also be achieved in gradient echo (GE) BOLD data at 7T due to the attenuation of intravascular signal from veins (Gati et al. 1997; Ogawa et al. 1998; van der Zwaag et al. 2009; Yacoub et al. 2001). However, the extravascular signal from venules and large veins that immediately drain the capillary bed may still cause some spread of the BOLD response.

Here we used fMRI at ultra-high field (7 T) to generate complete high-resolution maps of the digit representations in the primary somatosensory cortex (S1) in individual subjects. We aimed to maximize efficiency in mapping all five digits and to assess the use of a “traveling wave” paradigm as has been widely applied to retinotopic mapping (Engel et al. 1994, 1997; reviewed in Wandell et al. 2007); a similar approach was first used in the somatosensory system to map the ventral surface of the left arm (Servos et al. 1998). In addition, we validated the traveling wave activity against a simple event-related protocol, assessed the contribution of different tissues to the measured responses, and characterized the temporal properties of the event-related fMRI response in S1.

The results reveal a robust, consistent map of digit representations in individuals along the posterior aspect of the central sulcus. In contrast to several previous studies that inferred cytoarchitectonic subregions by the existence of isolated peaks in thresholded statistical maps, our data show no such clear segregation (see e.g., Nelson and Chen 2008).

METHODS

Subjects

Five subjects experienced in fMRI experiments participated in this study with written consent. Procedures were conducted with approval from the University of Nottingham ethics committee. Each subject participated in three scan sessions: two sessions at 7T, one session to measure the topographic representation of digits in the somatosensory cortex with a traveling wave paradigm, and one session to characterize the spatial and temporal properties of responses to vibrotactile digit stimulation in an event-related task design. In addition, one session was performed at 3T to obtain high-resolution T1-weighted (MPRAGE, 1 mm isotropic) anatomical images of the whole brain.

Stimuli and paradigm

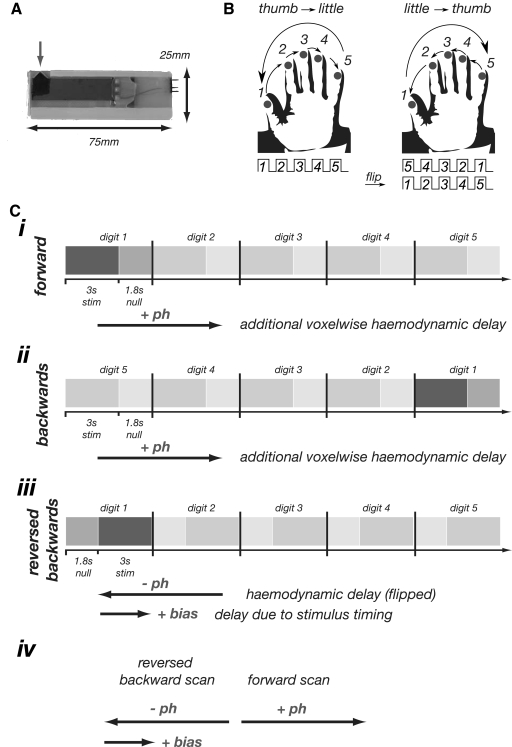

Tactile stimuli were delivered to the digit tips of the left hand using five independent, custom-built, MR-compatible, piezoelectric devices. Each stimulator delivered a somatosensory stimulus at a frequency of 30 Hz with ∼1 mm displacement applied over a ∼1 mm2 area of contact (Dancer Design, UK; Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

A: single piezo-electric stimulator device. The gray arrow indicates the protruding tip which is applied to skin (∼1 mm thickness); direction of movement is in and out of the plane. B: illustration of the traveling wave paradigm. Vibrotactile stimuli were applied to the fingertips in “forward” ordering from thumb to little finger or “backward” ordering from little finger to thumb. The backward scans can be time reversed and time-shifted to cancel any residual hemodynamic lag. C: illustration of expected temporal delays in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) responses in traveling wave paradigm due to the effect of hemodynamics and experimental design. I: timing diagram for the forward sequence. For voxels responding to stimulation of digit 1, the only delay (w.r.t. the onset of cycle) is due to hemodynamics (+ph). The additional arrow indicates this delay. Ii: timing diagram for the backward sequence, again with additional arrow indicating the delay (+ph). Iii: time-reversal of the backward sequence leading to reversal of the inherent hemodynamic delay. The asymmetry in the stimulation paradigm (3 s stimulation is followed by an 1.8 s off period) results in the sequence being delayed (or biased) by 1.8 s. iv: summary of the effects of hemodynamic delay and bias due to the stimulation paradigm. If the time series are simply averaged, the resulting time course will retain a delay (of magnitude +bias/2). To remedy this, we advance the phase values of the time-reversed backward scan by 1.8 s giving the difference between the 2 phase values for a given region of interest (ROI) equal to twice the inherent hemodynamic delay.

Two experimental paradigms were used: a traveling wave paradigm in which the sensory stimulation created a wave of activity across cortical regions containing a somatotopic map of the hand and an event-related paradigm in which stimulation was simultaneously applied to all five digits for brief periods. The traveling wave paradigm involved applying stimuli sequentially to different digits. Each digit was stimulated for 3 s, with an off period of 1.8 s between stimulation of adjacent digits. A whole cycle of stimulation of all five digits thus took 24 s. Digits were stimulated in a “forward” sequence from thumb to little finger (digit 1 to digit 5) and in a “backward” sequence (starting at the little finger and moving to the thumb; Fig. 1, B and C). In both cases, this resulted in each digit experiencing a 3 s stimulus followed by a 21 s off period. Similar paradigm designs have been extensively used to form retinotopic maps of the visual cortex (as reviewed in Wandell et al. 2007). In our study, a single traveling wave fMRI experiment (scan) consisted of 10 cycles, resulting in a scan-duration of 240 s. A total of six repeats of the traveling wave fMRI experiment were performed in a single fMRI session, alternating the repeats between forward and backward stimulation sequences. For the event-related paradigm, all five digits were simultaneously stimulated for an on period of 3 s (matching the individual digit stimulation period used in the traveling wave paradigm) with random interstimulus intervals of 18, 19, or 20 s. Each functional experiment consisted of 12 trials (228 s duration), and three experiments were run on each subject in a single fMRI session.

Functional MRI data acquisition

fMRI data were collected on a 7T Philips Achieva system (Philips Medical Systems) using a volume transmit head coil and 16-channel receive coil. To minimize head motion, subjects were stabilized using a customized MR-compatible vacuum pillow (B.U.W. Schmidt) and foam padding. Data were collected using T2*-weighted, gradient echo, single shot, echo planar imaging (GE-EPI) with the following scan parameters: SENSE factor 2 in the right-left direction, TE = 25 ms, flip angle FA = 90°, TR = 2.4 s. A total of 22 contiguous axial slices spanning the right primary somatosensory cortex were acquired with 1 mm isotropic resolution and a field of view (FOV) of 192 mm in the anterior-posterior (AP) direction and 72 mm in the right-left (RL) direction. The reduced FOV in the phase encoding direction (RL) required the use of outer-volume suppression (OVS) (Pfeuffer et al. 2002) to prevent signal fold-over. The locations of the imaging stack and OVS slab are shown in Fig. 3A for a representative subject. Magnetic field inhomogeneity was minimized by using a local, image-based shimming approach (Poole and Bowtell 2008; Wilson et al. 2002). This involved generating a B0-field map from the difference in phase of two gradient echo images with echo times of TE1 = 6 ms and TE2 = 6.5 ms; skull-stripping the B0-field map (BET, FSL) (Smith 2002) so that field optimization could be focused on brain regions; and determining the shim coil currents up to second order needed to minimize the field inhomogeneity inside a cuboidal region containing the central sulcus (highlighted in Fig. 3A). The shim calculation took <30 s (Matlab R2007, 2.0 GHz Pentium 4 processor). The efficacy of the image-based shimming procedure was compared with that of the FASTMAP approach (Gruetter 1993) as implemented on the Philips scanner, by acquiring B0-field maps and EP images after shimming on the same cuboidal target region with each procedure and converting to a geometric distortion or spatial offset map in pixel units (deviations in Hz converted to pixels using a 22.8 Hz bandwidth per pixel of the EPI sequence).

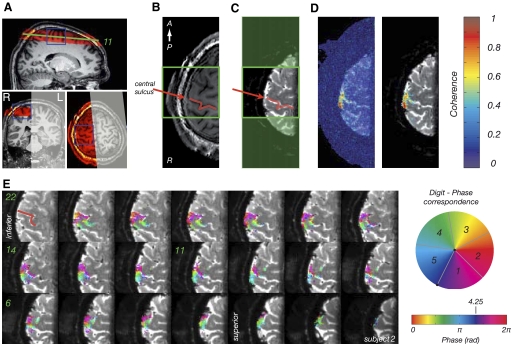

Fig. 3.

A: location of the imaging stack for zoomed fMRI (red) superimposed on MPRAGE scan for a representative subject. The gray shaded area indicates the location of the outer volume suppression slab and the blue lines show the location of the shim box. B: single slice of the MPRAGE image (1 mm isotropic MPRAGE) collected in the same location as the T2*-weighted EPI data. The red line indicates the location of central sulcus, the green box the cropping used in E. C: mean T2* weighted EP image obtained by averaging 100 repeats of 1 functional MRI scan; because fMRI data contain slight residual geometric distortions with respect to the MPRAGE images, statistical images are superimposed on the average EPI data. Red line, as in B. D: statistical map superimposed on mean EPI image. Transparent colors, coherence with best-fitting sinusoid at frequency of stimulus paradigm. Note values close to 1, indicating high statistical significance. Left: no thresholding applied. Right: statistical image obtained with threshold-free cluster enhancement, TFCE. E: statistical map (from the average of 6 scans) superimposed on mean T2*-weighted EPI data for all slices in stack. Axial slices are numbered from most superior (1) to most inferior (22). Colors indicate the phase values from traveling wave paradigm. Note that the statistical map is thresholded based on application of TFCE to the coherence map (see D). For this subject, the ROI contained 1,998 voxels. The mean coherence value was 0.53 ± 0.13 (minimum-to-maximum range: 0.35–0.94), the mean fMRI response amplitude across all voxels 3.28 ± 3.2% (range: 0.72–21.38), and the mean raw image intensity of the EP image was 22,434 ± 6,957 (range: 4,014–50,071).

To classify voxels in the functional, T2*-weighted data into tissue type, we also acquired three inversion recovery EP data sets (with the same bandwidth, matrix size, and shim settings to ensure that any residual geometric distortions were matched to the functional data). The inversion delays (TI) of 450, 1,200, and 2,300 ms were chosen to null white matter, gray matter, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), respectively. T1-weighted anatomical images with the same slice prescription, coverage, and resolution as the functional data (MPRAGE sequence with linear phase encoding order, TE = 2.14 ms, TR = 14 ms, FA = 10°, TI = 960 ms, 2 averages) were also acquired during each 7T scanning session. T1-weighted anatomical images of the whole brain (3D MPRAGE, 1 mm isotropic resolution, linear phase encoding order, TE = 3.7 ms, TR = 8.13 ms, FA = 8°, TI = 960 ms) were also acquired from each subject at 3T. These images, which displayed less B1-inhomogeneity-related signal intensity variation than images acquired at 7T, were used for gray matter segmentation and cortical flattening.

Data processing

The effective local geometric distortion due to residual magnetic field inhomogeneity was assessed for the two different shimming techniques by converting field offsets to spatial shifts based on the 22.8 Hz bandwidth per pixel of the EPI data. The EPI data were also visually compared against the MPRAGE data. The image-based shimming technique significantly reduced geometric distortions (see results) and so was used for all subsequent fMRI data acquisitions.

Functional image analysis was performed with a combination of custom-written software (mrTools, NYU, http://www.cns.nyu.edu/heegerlab/wiki/; VISTA, Stanford) running in Matlab 7.4 (Mathworks, Natick, MA) and FSL (FMRIB, Oxford, UK) (Smith et al. 2004). fMRI data were motion-corrected within and between scans in a given session (for traveling wave and event-related data) using a robust motion correction algorithm (Nestares and Heeger 2000), and the fMRI time series was then high-pass filtered to eliminate slow signal drift. Finally, each voxel's time series was divided by its mean intensity to convert the data from image intensity to units of percentage signal change. No spatial filtering was applied to the data. The mean of the T2*-weighted fMRI time-series was calculated and subsequently calculated statistical maps overlaid on this image. For additional visualization, the statistical maps from traveling wave and event-related data were transformed to the space of the anatomical MPRAGE data acquired at 3 T (see Schluppeck et al. 2005).

Traveling wave data analysis

Standard Fourier-based analysis methods (Engel et al. 1994) were applied voxel-by-voxel to generate somatotopic maps. We computed the coherence between the time series and the best-fitting sinusoid at the 0.04167 Hz stimulus repetition frequency, the phase of the response at that frequency, and the amplitude of the best-fitting sinusoid. The coherence measures the contrast to noise (Engel et al. 1994, 1997) of the response, taking a value near 1 when the fMRI signal modulation at the stimulus frequency is large relative to the noise (in other frequency components) and a value near 0 when there is no signal modulation or when the signal is small compared with the noise. The phase measures the temporal delay of the fMRI signal with respect to the onset of the stimulus cycle and therefore for this paradigm, reflects the spatial location of the stimulus (which digit) on the hand. A somatotopic map should therefore be visible on the cortical surface as a smooth progression of early to late phase values, corresponding to the different digits of the hand.

The time series data for the “forward” (from digits 1 to 5) and “backward” (from digits 5 to 1) stimulus sequences were combined following the standard approach used in retinotopic mapping (Engel et al. 1997; Sereno et al. 2001) to remove the effect of the hemodynamic delay in visualizing the somatotopic maps. This process is illustrated in Fig. 1C. Both the “forward” and “backward” scans were time-shifted (advanced by 2 TRs), to approximately cancel any residual hemodynamic delay at each voxel, the backward scans were then time reversed, and finally the forward and transformed backward scans were averaged. The resulting mean time series at each voxel in the average data (and its associated phase value) therefore approximately reflected the timing of the forward ordering scans, in which digits were stimulated sequentially from thumb (digit 1) to little finger (digit 5). We then subdivided the range of phase values in steps of 2π/5 corresponding to the somatotopic representations of digits 1–5. To incorporate information about the local spatial support of statistically significant responses, threshold-free cluster enhancement (TFCE) (Smith and Nichols 2009) was applied to the coherence map (H = 2, E = 0.5, neighborhood connectivity = 6). Regions of interest (ROIs) comprising voxels in the top percentile of the resulting image were then interrogated to produce fMRI time series, response (Fourier) amplitude, and related statistics for the different scans.

To estimate the hemodynamic lag from the traveling wave data, the time courses of the average forward and time-reversed backward scans (to which no time shift had been applied) were compared in detail. If we assume that after time reversal of the backward scans the time delay of the response is equal, but opposite in sign to that in the forward scans, then the difference in phase of the best-fitting sinusoids to the two time courses corresponds to twice the hemodynamic delay (this is defined as the uncorrected hemodynamic delay – see results).

Event-related data analysis

A model free deconvolution analysis procedure (Boynton et al. 1996; Buckner et al. 1998; Burock et al. 1998) was used to identify consistently active areas in the event-related data. Specifically, we used the data-driven analysis approach developed by Gardner et al. (2005) to reconstruct event-related fMRI responses to digit stimulation without making any prior assumptions about the shape of the response (or that of the underlying hemodynamic response function). First, the time series of each voxel in the three individual scans was high-pass filtered with a cutoff frequency of 0.01 Hz and converted to percent signal change. Data from the three scans were then concatenated to allow estimation of the response using all the acquired event-related data. The event-related fMRI response for a single event-type (all 5 fingers stimulated for 3 s) at a given voxel was then computed by finding the ordinary least-squares solution to the equation S·HT + noise = BT, where B is the measured (mean-subtracted) BOLD time course, S the stimulus convolution matrix, H the to be estimated event-related fMRI response, and []T the transpose operation. This yields the best least-squares estimate for the event-related fMRI response. Statistical activation maps were computed from the amount of variance in the original fMRI time course accounted for by events modeled (using the estimated event-related response) to be time-locked to stimulus presentations, r2 = 1 − variance(residual)/variance(original). The residual was calculated as the difference between the estimated time course (based on the least-squares solution) and the original time course.

To estimate the hemodynamic lag from the event-related data, the measured fMRI responses in ROIs defined for each digit from the phase measured in the traveling wave experiment were fitted using the model of the hemodynamic response function (HRF) as described in Eq. 1 (Friston et al. 1998; Glover 1999). The best-fit parameters were estimated by nonlinear least squares fitting and the time-to-peak of the fitted response was then determined numerically to provide an estimate of the hemodynamic delay.

Cortical segmentation and flattening

Inversion recovery (white, gray, and CSF nulled) images were used to visualize the location of the activity on the EP images (data not shown). To display activation on a cortically flattened surface, a registration algorithm (Nestares and Heeger 2000) was first used to align the MPRAGE anatomical images acquired at the end of each functional session to the co-registered fMRI data. The high-resolution MPRAGE images acquired at 7T were then registered to the whole-head 3T MPRAGE data. The 3T MPRAGE images were then used in a subset of subjects to create flattened visualizations of the cortical activity restricted to gray matter voxels. Cortical segmentations were obtained using a combination of tools [SurfRelax (Larsson 2001); FSL distribution, FMRIB Software Library (Smith et al. 2004)] using methods previously described (Schluppeck et al. 2006). It is important to note that data were projected onto surface representations as a final visualization step only. For the flat maps shown in the Results (Fig. 6), it was ascertained that the gray/white matter segmentations of the MPRAGE images for each particular subject were in good agreement with the EPI data (see also Fig. 2).

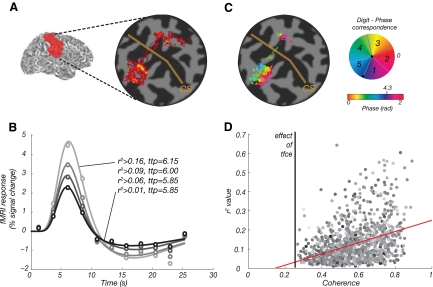

Fig. 6.

A: coherence map based on the r2 values from the event-related data (subject 5). B: mean event-related fMRI responses in S1 for subject 5. Symbols, mean event-related time course for voxels in the functional ROI defined in the traveling wave experiment (error bars, SE, are smaller than the plot symbols). Colors, data were thresholded according to the distribution of r2 value obtained for each voxel in the event-related analysis [ROI contain voxels with r2 over 0, 25, 50, and 75% of the r2 distribution (as for Table 3 for all subjects)], results plotted separately for the lowest (dark) to highest (bright) threshold. Solid lines, corresponding fits to the hemodynamic response function. ttp indicates the hemodynamic delay of the curve. C: coherence map from the traveling wave analysis (subject 5). Similar activation patterns can be seen for the primary somatosensory cortex for the event-related paradigm (A). D: direct comparison of the traveling wave and event-related data for subject 5 indicates that voxels with the highest r2 values (obtained in the event-related experiment) also tend to give most significant responses in the traveling wave experiment (linear regression: y = 0.29x − 0.04, Pearson correlation:0.39). Color, image intensity of underlying T2*-weighted EPI data.

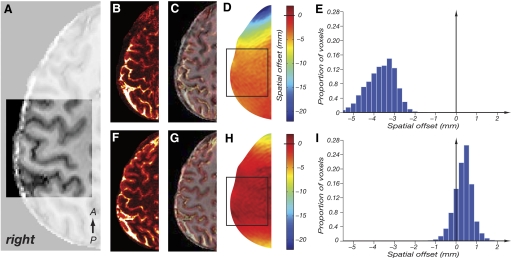

Fig. 2.

Effect of shimming on geometric distortion in echo planar imaging (EPI) images with pixel bandwidth of 22.8 Hz and phase-encoding (and hence distortion) in the right-left direction. A: skull-stripped anatomical image (MPRAGE, 1 mm isotropic resolution). Highlighted square indicates shimming volume. Orientation of stack as shown in Fig. 3A. B: EPI acquired with FASTMAP shimming method. C: EPI from B (hot colors) superimposed on undistorted MPRAGE image (greyscale) from A. Note the significant mismatch between echo-planar and MPRAGE images. D: field map obtained with the FASTMAP shimming method. Colors indicate the magnitude of geometric distortion in the phase-encode direction (right-left) in mm. The black square represents the border of the shim box. E: histogram of the geometric distortion, proportion of voxels in shim box (y axis) with given spatial offset (in mm, x axis). F–I as in B–E for data acquired using the image-based shimming method. Note the reduced distortions in the field map (H) with the histogram (I) centered close to 0 and narrowed for the image based shimming method.

RESULTS

The image-based shimming method significantly reduced geometric distortions in the EPI data. Figure 2 shows example images obtained using the manufacturer's implementation of the FASTMAP shimming method (B and C) compared with the image-based shimming method (F and G). The image-based shimming method produces a better correspondence of EPI data and (undistorted) anatomical MPRAGE images. The reduction of residual geometric distortion is illustrated by the field-maps (D and H) and histograms of spatial offset (E and I), which show that distortion can be restricted to less than one voxel (1 mm) over the shimming region.

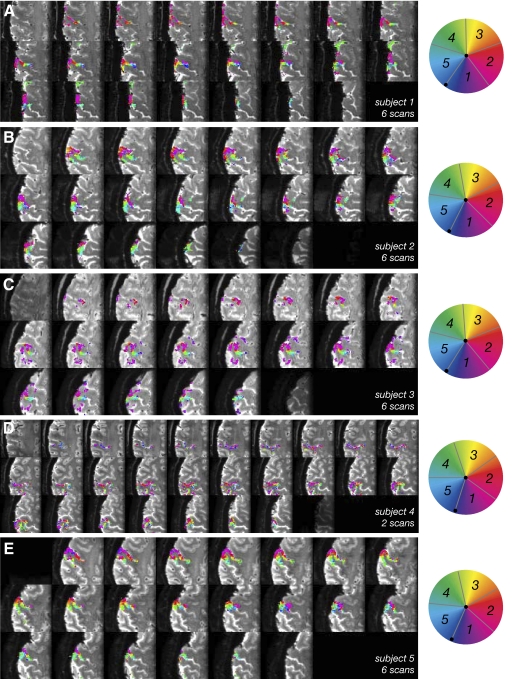

Analysis of the traveling wave data showed that the signal from a region of gray matter extending along the posterior bank of the central sulcus and the crown of the postcentral gyrus was significantly modulated at a frequency corresponding to the 24 s period of stimulation in all subjects. Figure 3 shows data from a representative subject (subject 2) with statistical maps superimposed on the mean T2*-weighted images from the functional scan. One scan (10 stimulus cycles, 100 volumes) was sufficient to form statistical maps, but to improve the SNR, responses were averaged across up to six scans before performing the standard Fourier analysis. The resulting coherence map (unthresholded) for one subject (average of 6 scans) is shown as a semi-transparent overlay in Fig. 3D (left) and following TFCE correction (right). The coherence map indicates that some voxels show nearly perfectly sinusoidal signal modulation (coherence values close to 1.0). The temporal delay, or phase, of the measured periodic response at a given point in the brain was then used to classify voxels corresponding to each stimulated digit. The resulting phase/”digit” map (Fig. 3E) showed consistency in the inferior-superior direction (across slices in the acquired stack) and an orderly mapping of phase values along the postcentral gyrus. Smaller phase delays, corresponding to digits 1 and 2 were present more laterally and inferiorly, while larger phase delays, corresponding to digits 3–5, more medially and superiorly. Figure 4 shows corresponding phase maps for all five subjects scanned; for each subject, a somatotopic map is clearly visible. Table 1 lists the average spatial extent of each individual digit representation and their SD, highlighting the variability in sulcal size and position across subjects. The areas of activation were localized to cortical gray matter as is evident from the images. For comparison, Table 2 shows the distribution of coherence, mean fMRI response amplitude and CNR across the functional ROIs obtained in each subject. The CNR was computed as the magnitude of the peak at 10 cycle/scan divided by the average of the magnitude of the high-frequency (33–50 cycle/scan) components in the Fourier spectrum (Fig. 5, C and F). The fMRI responses in individual voxels were large (with maximum values of the order of 10–24% peak-to-peak modulation) and robust, with CNRs of ≤40, but response strengths varied across voxels as well as subjects.

Fig. 4.

Statistical maps (average of 6 scans except for subject 4 with 2 scans) for each of 5 subjects scanned, superimposed on mean T2*-weighted EPI data for all slices in the stack, equivalent to Fig. 3E. Axial slices are numbered from most superior (1) to most inferior (22). Colors indicate the phase values from traveling wave paradigm. Statistical maps are thresholded using TFCE.

Table 1.

Spatial extent of digit representations in traveling wave maps averaged over subjects

| D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | D5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M-L, mm | 26.2 ± 5.9 | 23.2 ± 4.0 | 20.4 ± 5.0 | 20.6 ± 4.4 | 15.2 ± 4.4 |

| A-P, mm | 22.6 ± 2.1 | 21.2 ± 4.6 | 16.0 ± 1.9 | 15.6 ± 2.9 | 12.5 ± 4.3 |

| F-H, mm | 18.4 ± 0.9 | 18.0 ± 0.9 | 16.6 ± 1.9 | 16.6 ± 2.6 | 15.2 ± 2.9 |

| Volume, mm3 | 313 ± 140 | 373 ± 226 | 141 ± 47 | 225 ± 76 | 120 ± 60 |

Spatial extent of digit representations in travelling wave maps averaged over subjects for the medio-lateral (M-L), anterior-posterior (A-P), and foot-head (F-H) directions. Mean ± SD for each digit averaged across subjects.

Table 2.

Details of fMRI response for traveling wave paradigm

| Subject | Coherence Value (minimum − maximum) | Response Amplitude, % (minimum − maximum) | CNR |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.51 ± 0.12 (0.35–0.89) | 2.8 ± 1.4 (0.6–11.9) | 36.7 ± 7.0 |

| 2 | 0.53 ± 0.13 (0.35–0.94) | 3.3 ± 3.2 (0.7–21.4) | 39.5 ± 11.6 |

| 3 | 0.45 ± 0.11 (0.39–0.89) | 3.5 ± 1.5 (1.2–15.6) | 32.5 ± 6.3 |

| 4 | 0.39 ± 0.08 (0.30–0.67) | 4.2 ± 2.0 (1.6–24.6) | 19.4 ± 3.4 |

| 5 | 0.57 ± 0.13 (0.27–0.89) | 2.6 ± 1.3 (0.7–12.5) | 41.7 ± 5.4 |

fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging; CNR, contrast-to-noise ratio.

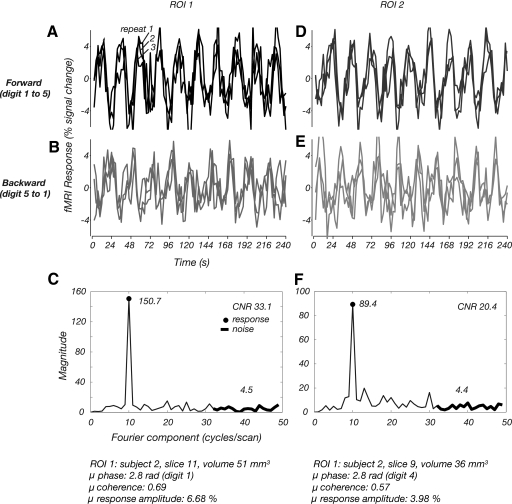

Fig. 5.

Time course plots from 2 small ROIs (columns) for 2 different stimulus conditions (rows). Details of the ROI are provided at the bottom of the figure. A: each trace, mean fMRI response in ROI1 for each of 3 scans with a forward stimulus (advancing from digits 1–5). B: fMRI responses in ROI1 for backward sequence. C: amplitude spectrum of average time course across all scans in ROI1. Black circle, magnitude at stimulus alternation frequency. Thick black line, high-frequency components used to calculate contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR). D–F: corresponding data for ROI2.

The time courses measured in the traveling wave experiments showed high consistency across repeats and locations on the somatotopic map. Figure 5 shows the fMRI responses from the traveling wave paradigm (for subject 2) for two small regions of interest (ROI details in figure) sited along the posterior bank of the central sulcus in different slices for two sets of three scan averages [3 “forward” (f) scans; 3 “backward” (b) scans] that were acquired in interleaved order (f, b, f, b,.). The presence of the large peak at 10 cycle/scan in the Fourier spectrum clearly indicates that the responses are dominated by the effects of the somatosensory stimulation. Contributions to the response from frequency components other than the first harmonic are negligible (Fig. 5, C and F).

Figure 6 compares the r2 map calculated from the event-related data (A) with a coherence map from the traveling wave analysis (C) on a flattened surface (for subject 5). Similar activation patterns are seen in the primary somatosensory cortex for both the traveling wave and event-related paradigms. The mean time courses of event related data extracted from ROIs, which were independently defined by the somatotopic mapping are shown in Fig. 6B. Note that the estimated hemodynamic lag from the event-related data does not strongly depend on a particular choice of r2 threshold (Table 3). The solid lines represent the corresponding fits to the hemodynamic response function (Friston et al. 1998). Figure 6D indicates that voxels with the highest r2 values in the event-related data also tend to give most significant responses in the traveling wave experiment. The uncorrected hemodynamic lag estimated from the traveling wave data is shown in Table 3. The event-related study provided an independent estimate of the hemodynamic delay in each voxel, and so for two subjects, we compared the average hemodynamic delay estimated from the event-related data to that obtained from the traveling wave analysis (Table 3) using the methods and correction described in Fig. 7. The uncorrected hemodynamic lag estimated from the traveling wave data is significantly shorter than that measured from the event-related paradigm.

Table 3.

Hemodynamic delay of traveling wave and event-related data

| Hemodynamic Delay, s |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event-Related Estimates, s |

|||||

| Subject | Uncorrected Traveling Wave, s | Corrected Traveling Wave, s | ROI A | ROI B | ROI C |

| 3 | 3.92 ± 0.04 | 5.09 ± 0.04 | 6.85 ± 0.50 | 6.82 ± 0.54 | 6.74 ± 0.44 |

| 5 | 3.12 ± 0.32 | 4.33 ± 0.32 | 6.22 ± 0.23 | 6.15 ± 0.23 | 5.95 ± 0.23 |

Values are means ± SD. Hemodynamic delay measured using traveling wave (both uncorrected and corrected) and event-related data. ROIs were defined for each digit from the traveling wave statistical map. For the event-related data, the hemodynamic delay is estimated for each digit ROI at different r2 thresholds (ROI A–C threshold levels chosen to include voxels with r2 values > 25, 50, and 75% of the r2 distribution).

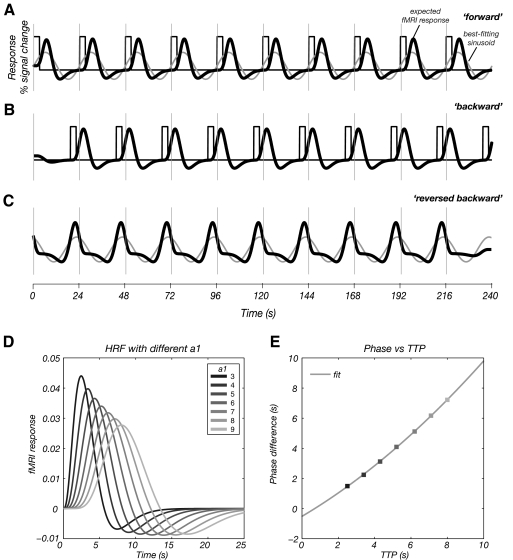

Fig. 7.

A: the stimulus input function of the forward scan of digit 1 (black line) convolved with the double gamma variate hemodynamic response function [HRF; 6 s time-to-peak (TTP); Eq. 1, a1 = 6, a2 = 12, b1 = 0.9 s, b2 = 0.9 s, c = 0.35] to simulate the forward fMRI response (thick black line). The simulated waveform (blue line) is then fitted to a sinusoidal wave of period 24 s (light gray line). The sinusoidal waveform shows a reduced time-to-peak compared with the model response. B: the stimulus input function of the backward scan for digit 1 (dark gray line), and the convolution with the double gamma variate HRF with 6 s TTP (as shown in A) to simulate the backward fMRI time course (thick black line). C: time reversed backward scan for digit 1 (thick black line) and fitted sinusoidal waveform (light gray line). The sinusoidal waveform shows a delayed time to peak compared with the double gamma variate HRF. The hemodynamic delay from the traveling wave analysis is estimated by first calculating the time between peaks of the 2 fitted sinusoid waveforms (light gray lines) in A and C. A delay of 1.8 s is then added to account for the time between stimulation of each digit (as shown in Fig. 1C). The resulting time difference is then divided by 2 to give an estimate of the hemodynamic delay. D: simulated double gamma variate HRF with a1 = 3 – 9 to simulate the range of hemodynamic delays found in the brain. E: simulated TTP of hemodynamic delay as determined from the traveling wave analysis [from the phase difference in the sinusoidal fits (A) and (C)] vs. the true hemodynamic TTP from the simulated HRF (D). Data show a parabolic relationship of y = 0.03x2 + 0.70x − 0.51.

Assessing systematic errors arising using Fourier analysis to estimate hemodynamic lag

The method of estimating the hemodynamic lag from the traveling wave data relies on the assumption that the fMRI time series can be well approximated by a sinusoidal function the period of which equals the length of the cycle (24 s) and that the hemodynamic delay and phase of the fitted sinusoidal response are tightly coupled. Here we perform a simulation to assess any potential bias in the estimation of the hemodynamic lag from traveling wave data.

Traveling wave signals were simulated using the timing of stimulus delivery and a model of the HRF, H(t), formed from the sum of two gamma functions (Friston et al. 1998)

| (1) |

where d1 = a1b1 and d2 = a2b2. Data were simulated for a range of HRF time-to-peak (TTP) values by varying parameter a1 from 3 to 9 while other parameters were fixed at a2 = 2; a1; b1 = 0.9 s; b2 = 0.9 s; c = 0.35 (Glover 1999) (Fig. 7D). The simulated data were then analyzed using the Fourier-method and the corresponding TTP of the hemodynamic delay was estimated. Based on this analysis, we calculated a correction factor for the traveling wave data. Figure 7 shows the steps of the simulation for digit 1. The fMRI time series is simulated from the asymmetric HRF (Eq. 1) convolved with the stimulus input function. The simulated fMRI response for the backward scan is time reversed and the responses for each of the forward and time-reversed backward scans are then fitted to a sinusoid of period 24 s. Assuming the hemodynamic lag is equal and opposite for the forward and time-reversed backward scans, the hemodynamic lag can then be estimated as half the difference between the delays found for the two conditions (light gray lines in Figs. 7A and 7C). However, we must also take into account an additional delay of 1.8 s for the time reversed data (Fig. 1C) that was included in the estimate of the uncorrected hemodynamic delay.

To estimate the inaccuracy in this uncorrected measure of hemodynamic lag, the uncorrected hemodynamic lag from the traveling wave data (as estimated from the phase difference in the sinusoidal fits) was plotted against the lag of the simulated HRF (as measured by the time to peak). For our simulated parameters, the hemodynamic lag from the traveling wave analysis (y) is related to the lag of the simulated HRF (x) by a parabolic relationship (y = 0.03x2 + 0.70x − 0.51), reflecting an underestimation of the hemodynamic lag in the traveling wave data. This relationship was used to correct the traveling wave hemodynamic delay, Table 3. Both methods yield estimates of hemodynamic delay that are comparable, but the delay from the event related paradigm is still longer.

DISCUSSION

These results demonstrate that robust maps of the representation of the fingers in human somatosensory cortex can be obtained with 1 mm isotropic resolution at 7T using a traveling wave paradigm and focal piezoelectric stimulation applied at 30 Hz to the fingertips. Areas of significant signal modulation were confined to the posterior aspect of the central sulcus and the crown of the postcentral gyrus and showed an orderly progression of phase of modulation reflecting the ordered somatotopic representation of digits 1–5 in primary somatosensory cortex (S1). The representation of digit 1 (thumb) was most inferior and lateral, whereas digits 2–5 were represented at increasingly superior and medial locations (Figs. 3 and 4). Unthresholded statistical maps confirm that the pattern of activation is almost exclusively on the postcentral side of the central sulcus and the crown of the postcentral gyrus. This is in contrast to some previous reports that have found that somatosensory representations extend further anteriorly to the precentral aspect of the sulcus (Moore et al. 2000).

The fMRI responses in individual voxels were large (from 10 to 24% peak-to-peak modulation, Table 2) and robust, with CNRs of ≤40. This can be compared with signal modulations of 3–4% for most sensory fMRI studies at 3T (Francis et al. 2000; Stippich et al. 1999) using 3 mm isotropic voxels. This large signal modulation at 7T is expected if a linear increase in BOLD signal with field strength can be realized (Gati et al. 1997; Yacoub et al. 2001). Here the increased CNR at ultra-high field has been exploited to achieve high-spatial resolution, reducing partial voluming of activated tissue with nonactivated gray matter and white matter/CSF. Potentially this can lead to larger and more consistent hemodynamic response modulations arising from cortical gray matter. In addition, 7T offers intrinsic improvements in spatial specificity for GE BOLD data compared with lower field strengths due to the supralinear increase in CNR in the microvasculature (Gati et al. 1997; Yacoub et al. 2003) and suppression of intravascular signal in draining veins distant from the site of neuronal activity due to shortening of venous blood T2 (∼7 ms) (Duong et al. 2003; Gati et al. 1997; Ogawa et al. 1998; Thulborn et al. 1982; Yacoub et al. 2003).

Another factor that may have improved spatial specificity in this experiment compared with previous studies is the paradigm design. First, tactile stimuli were delivered with a piezoelectric device at a stimulation frequency chosen to maximize the response in rapidly adapting somatosensory receptors the receptive fields of which are known to densely tile the glabrous skin on the digits (Darian-Smith 1982). Second, the traveling wave paradigm (Engel et al. 1997) is a form of differential paradigm and is likely to suppress nonspecific activation common to all digits, such as the BOLD signal in large veins draining from tissue spanning multiple digit representations in the postcentral gyrus, thus improving digit specific mapping. We compared the extent of activation maps for the traveling wave and event-related paradigms and found these to be similar, but the estimates of the hemodynamic lag were significantly shorter for the traveling wave paradigm (Table 3). The estimated hemodynamic delay is only slightly affected by the choice of thresholds. We performed a simulation to correct for the systematic errors introduced by the Fourier analysis in the estimating the hemodynamic lag. This reduced the discrepancy, but a difference of ∼1 s still remains. This discrepancy may in part be due to no slice-time correction being applied in our data analysis (to avoid interpolation effects), and this could give rise to an average 1.2 s error in the measured hemodynamic lag. The greater lag observed in the event-related estimates may also indicate an increased venous contribution (de Zwart et al. 2005; Hulvershorn et al. 2005) that is reduced by using a traveling wave paradigm.

The traveling wave paradigm has previously been applied to the study of somatosensory cortex only at coarse resolution using long cycle lengths (Huang and Sereno 2007; Overduin and Servos 2004) or to form an incomplete map of all digits of the hand. Overduin and Servos (2008) used a similar design to stimulate single digits from tip to base but did not use the Fourier-based analysis methods described in this study.

The spatial resolution of earlier functional MRI measurements (typically with voxel volumes of 10–30 mm3) (Kurth et al. 2000; Maldjian et al. 1999; Nelson and Chen 2008) is unfavorable with respect to the size of the somatotopic map. In our high resolution (1 mm isotropic) functional measurements, the extent of the sensory maps spanning D1–D5 was greater in the medial-lateral than AP or foot-head directions (Table 1). Digits 1 and 2 occupied the largest extent within the somatotopic map, whereas digit 5 has the smallest representation (Table 1). Note that the activation lies along the tortuous postcentral gyrus (Fig. 5) and with 1 mm isotropic resolution this leads to a band which is ∼29 mm in length in the postcentral gyrus for D1–D5 mapping. The failure to identify clear somatotopic maps in previous studies may have been due to the limits imposed by sampling a relatively small spatial map with comparatively coarse resolution. For example use of 3 mm isotropic resolution would yield somatotopic maps containing at best a third of the number of voxels measured in our study (assuming the best 1-dimensional tiling); at worst 1/33 taking into account volume. Even in those previous studies, where high-spatial resolution was used, the reduced contrast-to-noise necessarily reduced statistical power (Schweizer et al. 2008). In addition in several previous studies, results were averaged across-subjects, often registered into Talairach/MNI space. This causes blurring but also doesn't ensure exact alignment of anatomical structures across subjects, especially when their spatial extent is relatively small (Fischl and Dale 2000).

Previous studies, some based on relatively coarse resolution measurements, have emphasized the division of significant clusters of fMRI responses in S1 into four anatomical subdivisions (areas 1, 2, 3a, and 3b) (Moore et al. 2000; Nelson and Chen 2008; Overduin and Servos 2008), known to exist from anatomy, histology, and human/non-human single-unit physiology. These areas cannot currently be accurately identified using MRI in vivo but can roughly be assigned based on anatomical MR images: area 1 is located at the crown of the postcentral gyrus, area 2 in the postcentral sulcus, area 3a in the fundus of the central sulcus, and area 3b at the rostral bank of the postcentral gyrus. Microelectrode mapping studies in primates (e.g., Pons et al. 1987; Sur et al. 1984) have suggested that multiple representations of the body arise within primary somatosensory cortex with two complete body surface representations occupying cortical fields 3b and 1. Additionally it has been suggested that area 2 contains an orderly representation of predominantly deep body tissues, whereas area 3a may constitute a fourth representation. Several studies have compared functional data to these areas using probabilistic cytoarchitectonic maps derived from postmortem brains (see e.g., Geyer et al. 1999; see also Geyer et al. 2000; Grefkes et al. 2001; Schleicher et al. 2000). However, thresholding of statistical maps from fMRI experiments at a single significance value can lead to erroneous conclusions about multiple foci of activation corresponding to distinct anatomical subregions (the iceberg effect). Further, the spatial information in the probabilistic atlases currently does not capture the anatomical pattern of sulci and gyri, which makes accurate assignment to Brodmann regions difficult.

Given the size of the somatotopic maps of digit representations that we find, the spatial resolution and signal-to-noise limits imposed by fMRI data acquisition, and analysis methods of previous studies, we believe that the assignment of cyto-architectonic subregions based on the currently available simple mapping data alone is extremely problematic. Additionally, the anatomical variability in somatosensory cortex is known to be quite large (see e.g., White et al. 1997). In all previous imaging studies where this assignment was attempted, areas were classified either purely on the basis of geometric/anatomical information (referring to the layout of the cyto-architectonic subregions in postmortem samples in humans or monkeys), or using statistical maps that were computed and then thresholded to reveal several peaks that in turn were assigned, post hoc, to the different subregions.

Eickhoff et al. (2007) show that with careful consideration of the layout of the maps in somatosensory cortex (S2) and with reference to the monkey literature, such anatomical-functional assignments can be attempted, but in principle these measures require an even higher spatial resolution than for S1. In the study by Overduin and Servos (2004) where an attempt was made to map out the cytoarchitectonic subregions, the somatotopic maps were found to cover a distance of 50 mm in the rostral-caudal direction (10 coronal slices of 5 mm slice thickness), over double that found in our study and in previous work (e.g., Moore et al. 2000; Nelson and Chen 2008).

In this study, we found statistical maps with spatially contiguous representations of all digits. Stimulation of the fingertips mainly activated the rostral bank of the postcentral gyrus (defined operationally as area 3b), in agreement with a previous study using piezoelectric stimulation where “apparent” area 3b has shown some evidence of somatotopic organization (Schweizer et al. 2008). However, the spatial extent of the maps reported by Schweizer et al. (2008) was much smaller than our data, suggesting that previous functionally defined maps have greatly underestimated the cortical representation of the fingers. Given the relatively low indentation amplitude of our stimuli to the surface of the fingers, we did not expect to see responses dominated by neurons thought to be restricted to areas 3a and 2.

Although the pattern of the somatotopic maps is clearly visible in the axial planes in which our EPI data were acquired, with the direction of changing phase values in the map running along the central sulcus, surface rendering can provide a clearer sense of the spatial layout of topographic maps. Therefore to ease visualization of the two-dimensional digit topography, the statistical maps were rendered on inflated and flattened representations of the cortical surface (Fig. 6). For such visualization, accurate alignment between functional data and anatomical images is essential. The image-based shimming method has been shown to reduce distortions to less than one voxel (see methods and Fig. 2). Despite the relatively small residual geometric distortion between EP and anatomical images, problems in assigning responses to different sides of the postcentral sulcus may still result, although these can to some extent be overcome by image processing and careful segmentation and cortical unfolding (e.g., any voxel the activation of which is partial volumed over voxels, or voxels where there is simultaneous activation on both sides of the sulcus, could be excluded from further analysis). To enable more detailed surface-based analysis, segmentations have to be based on anatomical images with higher spatial resolution (e.g., 0.5 mm isotropic voxels), and future studies will assess the feasibility of using whole head anatomical MPRAGE data acquired at 7T in conjunction with normalization methods that can correct the nonuniform signal intensity (Van de Moortele et al. 2009). Additionally, small amounts of blurring due to spatial spreading of the hemodynamic response or caused by resampling in the motion correction step can aggravate such effects. Signal may appear in the precentral gyrus due to pial veins that drain the postcentral gyrus that share their extravascular signal with the precentral gray matter. However, note that the signal in the precentral aspect of the sulcus in the traveling wave data shown in Fig. 6C follows a progression of phase values consistent with the digit representations, indicating that such signal is likely caused by blurring due to venules specific to each digit, and not larger veins (which should lead to larger swaths of identical values in the phase maps). Also the spatial extent of activity on the precentral sulcus is larger for the event-related data, suggesting an increasing venous contribution to this data.

It remains to be seen whether a further reduction in image voxel size below 1 mm can lead to significant improvements in the achievable resolution in cortical maps. Artifacts due to subject motion, respiration, and the cardiac cycle may dominate at such small voxel sizes. In this study, subjects' heads were stabilized using customized MR compatible vacuum pillows and foam padding, and realignment results showed that subjects could maintain a stable head position within a fractions of mm for several minutes. Second, the width of the cortical point spread function (PSF) of the gradient-echo signal may be ultimately limiting; at 7T, the PSF has been shown to be of the order of 2.3 mm for gray matter with vessels masked out; this increased to 3.2 mm if veins were not excluded (Shmuel et al. 2007). However, recent studies of layer-specific activation using gradient echo BOLD (Harel et al. 2006; Koopmans et al. 2009; Ress et al. 2007) suggest that the intrinsic spatial resolution is of the order of the submillimeter level if contributions from pial veins are excluded.

The results of this study show that fMRI at 7T provides an excellent tool for studying the functional organization of cortex at a spatial resolution not easily achievable at lower field strengths. Because a somatotopic map can be obtained relatively quickly for an individual subject (<20 min scanning time), at 7T, these methods will allow researchers to study more complex aspects of somatosensory processing in follow-up experiments in the same session; making use of exact functional co-localization with an independent subject-specific somatotopic map. The maps are of sufficiently high resolution to resolve the representations of all five digits, and this could be a useful method to measure spatial changes in the cortical representations on the millimeter scale in, e.g., patients undergoing rehabilitation or plastic changes after peripheral nerve damage as well as tracking changes in normal subjects undergoing perceptual learning.

GRANTS

This work was funded by the Medical Research Council with grants to R. Bowtell, S. Francis, R. Sanchez-Panchuelo and supported by Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council Grant BB/G008906/1 to D. Schluppeck and S. Francis. R. Sanchez-Panchuelo is supported by a Marie Curie Early Stage Research Training Fellowship, D. Schluppeck by a Research Councils UK Academic Fellowship.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank our three anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Boynton GM, Engel SA, Glover GH, Heeger DJ. Linear systems analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging in human V1. J Neurosci 16: 4207–4221, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, Goodman J, Burock M, Rotte M, Koutstaal W, Schacter D, Rosen B, Dale AM. Functional-anatomic correlates of object priming in humans revealed by rapid presentation event-related fMRI. Neuron 20: 285–296, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burock MA, Buckner RL, Woldorff MG, Rosen BR, Dale AM. Randomized event-related experimental designs allow for extremely rapid presentation rates using functional MRI. Neuroreport 9: 3735–3739, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterworth S, Francis S, Kelly E, McGlone F, Bowtell R, Sawle GV. Abnormal cortical sensory activation in dystonia: an fMRI study. Mov Disord 18: 673–682, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darian-Smith I. Touch in primates. Annu Rev Psychol 33: 155–194, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Zwart JA, Silva AC, van Gelderen P, Kellman P, Fukunaga M, Chu R, Koretsky AP, Frank JA, Duyn JH. Temporal dynamics of the BOLD fMRI impulse response. Neuroimage 24: 667–677, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan RO, Boynton GM. Tactile hyperacuity thresholds correlate with finger maps in primary somatosensory cortex (S1). Cereb Cortex 12: 2878–2891, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duong TQ, Yacoub E, Adriany G, Hu XP, Ugurbil K, Kim SG. Microvascular BOLD contribution at 4 and 7 T in the human brain: gradient-echo and spin-echo fMRI with suppression of blood effects. Magn Resonance Med 49: 1019–1027, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff SB, Grefkes C, Zilles K, Fink GR. The somatotopic organization of cytoarchitectonic areas on the human parietal operculum. Cereb Cortex 17: 1800–1811, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel SA, Glover GH, Wandell BA. Retinotopic organization in human visual cortex and the spatial precision of functional MRI. Cereb Cortex 7: 181–192, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel SA, Rumelhart DE, Wandell BA, Lee AT, Glover GH, Chichilnisky EJ, Shadlen MN. fMRI of human visual cortex. Nature 369: 525, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, Dale AM. Measuring the thickness of the human cerebral cortex from magnetic resonance images. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 11050–11055, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis ST, Kelly EF, Bowtell R, Dunseath WJ, Folger SE, McGlone F. fMRI of the responses to vibratory stimulation of digit tips. Neuroimage 11: 188–202, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Fletcher P, Josephs O, Holmes A, Rugg MD, Turner R. Event-related fMRI: characterizing differential responses. Neuroimage 7: 30–40, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner JL, Sun P, Waggoner RA, Ueno K, Tanaka K, Cheng K. Contrast adaptation and representation in human early visual cortex. Neuron 47: 607–620, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gati JS, Menon RS, Ugurbil K, Rutt BK. Experimental determination of the BOLD field strength dependence in vessels and tissue. Magn Reson Med 38: 296–302, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelnar PA, Krauss BR, Szeverenyi NM, Apkarian AV. Fingertip representation in the human somatosensory cortex: an fMRI study. Neuroimage 7: 261–283, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer S, Schleicher A, Zilles K. Areas 3a, 3b, and 1 of human primary somatosensory cortex. Neuroimage 10: 63–83, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer S, Schormann T, Mohlberg H, Zilles K. Areas 3a, 3b, and 1 of human primary somatosensory cortex. II. Spatial normalization to standard anatomical space. Neuroimage 11: 684–696, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover GH. Deconvolution of impulse response in event-related BOLD fMRI. Neuroimage 9: 416–429, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grefkes C, Geyer S, Schormann T, Roland P, Zilles K. Human somatosensory area. II. Observer-independent cytoarchitectonic mapping, interindividual variability, and population map. Neuroimage 14: 617–631, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruetter R. Automatic, localized in vivo adjustment of all first- and second-order shim coils. Magn Reson Med 29: 804–811, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harel N, Lin J, Moeller S, Ugurbil K, Yacoub E. Combined imaging-histological study of cortical laminar specificity of fMRI signals. Neuroimage 29: 879–887, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang RS, Sereno MI. Dodecapus: an MR-compatible system for somatosensory stimulation. Neuroimage 34: 1060–1073, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulvershorn J, Bloy L, Gualtieri EE, Leigh JS, Elliott MA. Spatial sensitivity and temporal response of spin echo and gradient echo bold contrast at 3 T using peak hemodynamic activation time. Neuroimage 24: 216–223, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopmans PJ, Barth M, Norris DG. Layer-specific BOLD activation in human V1. Hum Brain Mapp In press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurth R, Villringer K, Curio G, Wolf KJ, Krause T, Repenthin J, Schwiemann J, Deuchert M, Villringer A. fMRI shows multiple somatotopic digit representations in human primary somatosensory cortex. Neuroreport 11: 1487–1491, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson J. Imaging Vision: Functional Mapping of Intermediate Visual Processes in Man (PhD thesis). Karolinska Institutet, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Maldjian JA, Gottschalk A, Patel RS, Detre JA, Alsop DC. The sensory somatotopic map of the human hand demonstrated at 4 Tesla. Neuroimage 10: 55–62, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore CI, Stern CE, Corkin S, Fischl B, Gray AC, Rosen BR, Dale AM. Segregation of somatosensory activation in the human rolandic cortex using fMRI. J Neurophysiol 84: 558–569, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson AJ, Chen R. Digit somatotopy within cortical areas of the postcentral gyrus in humans. Cereb Cortex 18: 2341–2351, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestares O, Heeger DJ. Robust multiresolution alignment of MRI brain volumes. Magn Reson Med 43: 705–715, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa S, Menon RS, Kim SG, Ugurbil K. On the characteristics of functional magnetic resonance imaging of the brain. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct 27: 447–474, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overduin SA, Servos P. Distributed digit somatotopy in primary somatosensory cortex. Neuroimage 23: 462–472, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overduin SA, Servos P. Symmetric sensorimotor somatotopy. PLoS ONE 3: e1505, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penfield W, Boldrey E. Somatic motor and sensory representation in the cerebral cortex of man as studied by electrical stimulation. Brain 60: 389–443, 1937. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeuffer J, van de Moortele PF, Yacoub E, Shmuel A, Adriany G, Andersen P, Merkle H, Garwood M, Ugurbil K, Hu XP. Zoomed functional imaging in the human brain at 7 Tesla with simultaneous high spatial and high temporal resolution. Neuroimage 17: 272–286, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pons TP, Wall JT, Garraghty PE, Cusick CG, Kaas JH. Consistent features of the representation of the hand in area 3b of macaque monkeys. Somatosens Res 4: 309–331, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole M, Bowtell R. Volume parcellation for improved dynamic shimming. Magma 21: 31–40, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ress D, Glover GH, Liu J, Wandell B. Laminar profiles of functional activity in the human brain. Neuroimage 34: 74–84, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleicher A, Amunts K, Geyer S, Kowalski T, Schormann T, Palomero-Gallagher N, Zilles K. A stereological approach to human cortical architecture: identification and delineation of cortical areas. J Chem Neuroanat 20: 31–47, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schluppeck D, Curtis CE, Glimcher PW, Heeger DJ. Sustained activity in topographic areas of human posterior parietal cortex during memory-guided saccades. J Neurosci 26: 5098–5108, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schluppeck D, Glimcher P, Heeger DJ. Topographic organization for delayed saccades in human posterior parietal cortex. J Neurophysiol 94: 1372–1384, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer R, Voit D, Frahm J. Finger representations in human primary somatosensory cortex as revealed by high-resolution functional MRI of tactile stimulation. Neuroimage 42: 28–35, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scouten A, Papademetris X, Constable RT. Spatial resolution, signal-to-noise ratio, and smoothing in multi-subject functional MRI studies. Neuroimage 30: 787–793, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sereno MI, Pitzalis S, Martinez A. Mapping of contralateral space in retinotopic coordinates by a parietal cortical area in humans. Science 294: 1350–1354, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servos P, Zacks J, Rumelhart DE, Glover GH. Somatotopy of the human arm using fMRI. Neuroreport 9: 605–609, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shmuel A, Yacoub E, Chaimow D, Logothetis NK, Ugurbil K. Spatio-temporal point-spread function of fMRI signal in human gray matter at 7 Tesla. Neuroimage 35: 539–552, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM. Fast robust automated brain extraction. Human Brain Mapp 17: 143–155, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Johansen-Berg H, Bannister PR, De Luca M, Drobnjak I, Flitney DE, Niazy RK, Saunders J, Vickers J, Zhang Y, De Stefano N, Brady JM, Matthews PM. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage 23, Suppl 1: S208–219, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Nichols TE. Threshold-free cluster enhancement: addressing problems of smoothing, threshold dependence and localisation in cluster inference. Neuroimage 44: 83–98, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stippich C, Hofmann R, Kapfer D, Hempel E, Heiland S, Jansen O, Sartor K. Somatotopic mapping of the human primary somatosensory cortex by fully automated tactile stimulation using functional magnetic resonance imaging. Neurosci Lett 277: 25–28, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sur M, Wall JT, Kaas JH. Modular distribution of neurons with slowly adapting and rapidly adapting responses in area 3b of somatosensory cortex in monkeys. J Neurophysiol 51: 724–744, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thulborn KR, Waterton JC, Matthews PM, Radda GK. Oxygenation dependence of the transverse relaxation time of water protons in whole blood at high field. Biochim Biophys Acta 714: 265–270, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Moortele PF, Auerbach EJ, Olman C, Yacoub E, Ugurbil K, Moeller S. T(1) weighted brain images at 7 Tesla unbiased for proton density, T(2) contrast and RF coil receive B(1) sensitivity with simultaneous vessel visualization. Neuroimage 46: 432–446, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Zwaag W, Francis S, Head K, Peters A, Gowland P, Morris P, Bowtell R. fMRI at 1.5, 3 and 7T: characterising BOLD signal changes. Neuroimage 47: 1425–1434, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wandell BA, Dumoulin SO, Brewer AA. Visual field maps in human cortex. Neuron 56: 366–383, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weibull A, Gustavsson H, Mattsson S, Svensson J. Investigation of spatial resolution, partial volume effects and smoothing in functional MRI using artificial 3D time series. Neuroimage 41: 346–353, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White LE, Andrews TJ, Hulette C, Richards A, Groelle M, Paydarfar J, Purves D. Structure of the human sensorimotor system. I. Morphology and cytoarchitecture of the central sulcus. Cereb Cortex 7: 18–30, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JL, Jenkinson M, de Araujo I, Kringelbach ML, Rolls ET, Jezzard P. Fast, fully automated global and local magnetic field optimization for fMRI of the human brain. Neuroimage 17: 967–976, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yacoub E, Duong TQ, Van De Moortele PF, Lindquist M, Adriany G, Kim SG, Ugurbil K, Hu X. Spin-echo fMRI in humans using high spatial resolutions and high magnetic fields. Magn Reson Med 49: 655–664, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yacoub E, Shmuel A, Pfeuffer J, Van de Moortele PF, Adriany G, Andersen P, Vaughan JT, Merkle H, Ugurbil K, Hu X. Imaging brain function in humans at 7 Tesla. Magn Reson Med 45: 588–594, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]