Abstract

OX40 is an inducible co-stimulatory molecule expressed by activated T cells. It plays an important role in the activation and proliferation of T lymphocytes. Recently, some co-stimulatory molecules have been shown to direct leukocyte trafficking. Chemotaxis is essential for achieving an effective immune response. CCL20 is an important chemoattractant produced by activated T cells. In this study, using DO11.10 mice whose transgenic T cell receptor specifically recognizes ovalbumin, we demonstrate that ovalbumin induces OX40 expression in CD4+ lymphocytes. Further stimulation of OX40 by OX40 activating antibody up-regulates CCL20 production. Both NF-κB dependent and independent signaling pathways are implicated in the induction of CCL20 by OX40. Finally, we primed the DO11.10 splenocytes with or without OX40 activating antibody in the presence of ovalbumin. Intranasal administration of the cell lysates derived from the cells with OX40 stimulation results in more severe leukocyte infiltration in the lung of DO11.10 mice, which is substantially attenuated by CCL20 blocking antibody. Taken together, this study has shown that activation of OX40 induces CCL20 expression in the presence of antigen stimulation. Thus, our results broaden the role of OX40 in chemotaxis, and reveal a novel effect of co-stimulatory molecules in orchestrating both T cell up-regulation and migration.

Keywords: CCL20, CD4+ T cells, Co-stimulatory molecule, OX40, T cell co-stimulation

1. Introduction

T cell-mediated adaptive immunity is characterized by its long-term immune memory and antigen specific response [1,2]. It is a vital component of our immune system, and plays a critical role in antigen recognition and host defense. However, aberrant T cell reaction results in many diseases such as asthma, inflammatory bowel disease, multiple sclerosis, and uveitis [3–6]. The generation, activation, and recruitment of sufficient T cells are essential steps to wage a full-fledged immune response. After encountering antigen, coordinated migration enables activated T cells to traffic through secondary lymphoid organs and infiltrate to inflamed tissues.

Regulating this complex T cell-mediated immune response requires sophisticated molecular machinery. T cell activation and differentiation requires a dual signaling process [7–11]. The first signal is mediated by the T cell receptor (TCR) interacting with an antigen fragment presented by the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) on antigen presenting cells (APC). Subsequently, an array of co-stimulatory molecules provides a second signal that is crucial to the amplification of the T cell activation [7–11]. Without further ligation of co-stimulatory molecules with their corresponding partners, the stimulation of TCR alone leads to T cell anergy. Co-stimulatory molecules regulate a variety of biological processes including T cell differentiation, proliferation, activation, and survival [7–11]. In addition to facilitating TCR signaling, some co-stimulatory molecules have been found to modulate T cell trafficking. For instance, CD28 reportedly enhances T cell migration, whereas CTLA-4 exhibits an opposing effect [12–16].

OX40 (CD134) is a co-stimulatory molecule in the tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) superfamily. It is mainly expressed by effector T cells [17–21]. OX40 signals through phosphatidylinositol-3-kinases (PIK3), eventually leading to NF-κB activation [17,18]. Activation of NF-κB by OX40 provides a crucial co-stimulatory signal for T cell activation, proliferation and survival [17,18]. Unlike constitutively expressed CD28 that is responsible for initial T cell activation, OX40 is an inducible co-stimulatory molecule, and is preferentially up-regulated in activated CD4+ T cells. In general, OX40 provides a second wave of co-stimulation, thereby contributing to the enhancement of T cell function rather than initiation of T cell activation [17–19]. Furthermore, Lane P et al. have reported that engagement of OX40 and OX40 ligand at the time of T cell activation up-regulates CXCR5, thereby directing CD4+ T cells into B cell follicles. This finding underscores the role of OX40 in coordinating T cell migration to promote lymphocyte interaction [20, 21].

CCL20, also called MIP-3α or LARC, is a unique CC chemokine with various naturally occurring isoforms [22–24]. T cells, especially Th17 cells, are a major source of CCL20 production [25–27]. CCL20 is strongly up-regulated during inflammation. This novel CC chemokine specifically recognizes CCR6 expressed on immature dendritic cells and activated T and B lymphocytes [28]. Thus, the CCL20/CCR6 axis ensues the strategic deployment of key immune cells during the early phase of inflammation. However, it is unclear whether co-stimulatory molecules regulate the expression of chemokines such as CCL20 as a mechanism of enhancing T cell effector function after initial antigen recognition.

Based on above studies, we postulated that OX40 signaling induces CCL20 expression, establishing a conducive environment for cell trafficking during the initial immune response. In this study, using DO11.10 mice whose transgenic TCR specifically recognizes ovalbumin (OVA), we demonstrate that OVA induces OX40 expression primarily in CD4+ T lymphocytes. Further stimulation of OX40 by OX40 activating antibody up-regulates CCL20 production in a dose-dependent manner, and non-PI3K-mediated NF-κB signaling is implicated in the induction of CCL20 by OX40. Finally, we primed the DO11.10 splenocytes with and without OX40 activating antibody in the presence of OVA. Intranasal administration of the cell lysates derived from these cells with OX40 stimulation results in more severe leukocyte infiltration in the lung of DO11.10 mice. This marked airway inflammation is substantially attenuated by CCL20 blocking antibody. Taken together, our study reveals a novel effect of OX40 on T cell activation. In addition, this finding further supports and validates the role of co-stimulatory molecules in leukocyte recruitment.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Mice

Six- to 8-week-old female DO11.10 mice on a BALB/c background (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine) were used for the experiments. These mice were housed in the regular animal room at Oregon Health & Science University, and had free access to water and standard chow. All studies were performed with the approval of our institutional animal care and use committee.

2.2. Cell Culture and Stimulation

After DO11.10 mice were sacrificed, their spleens were removed. Single cell suspensions were prepared by passing the tissue through a 70 μm cell strainer (BD Biosciences, Mountain View, CA). Red blood cells (RBC) were lysed with 1X RBC lysis buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) at room temperature for 5 min. The cell suspension was washed twice with RPMI 1640, and then cultured in RPMI 1640 with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) in an atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37°C. The DO11.10 splenocytes (5 × 106/ml) were then cultured with OVA323–339 peptide (Ile-Ser-Gln-Ala-Val-His-Ala-Ala-His-Ala-Glu-Ile-Asn-Glu-Ala-Gly-Arg) (AnaSpec, Fremont, CA) (5 μg/ml) in the presence or absence of OX40 activating antibody (Clone OX-86) (4 μg/ml) up to 72 hours. In some experiments, CD4+ lymphocytes were further isolated from the OVA-stimulated DO11.10 splenocytes using EasySep® Mouse CD4+ T Cell Enrichment Kit (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC) according to the manufacturer’ instruction. After repeated freezing and thawing, the cell lysates were collected for further analysis.

2.3. Flow Cytometry

DO11.10 splenocytes were suspended in PBS containing 2% FBS and 0.1% sodium azide. Anti-CD4 (Clone RM4-5), anti-OX40 (Clone OX-86), anti-CD8 (Clone 53-6.7), and anti-CCR6 (Clone 114906) antibodies conjugated with different fluorescent colors were used to label these cell surface markers for 30 minutes. After PBS wash, the cells were fixed with 1x fixation solution (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) at 4°C. Data acquisition was performed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer, and data were analyzed using CellQuest software.

2.4. ELISA

Various experimental groups of DO11.10 splenocytes and T lymphocytes were cultured with RPMI1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol. The culture media were collected at 24, 48 and 72 hour time points, and ELISA was performed to measure the IL-17 and CCL20 levels according to the manufacturer’s protocols (R and D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

2.5. Western Blot

DO11.10 splenocytes treated with or without OX40 activating antibody were collected in 1X LDS lysis buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) on ice. The lysates were then centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 min. Thirty μl of total protein from each group were separated by electrophoresis through a 4–12% gradient Tris-glycine SDS gel, and then transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. After milk blocking, the nitrocellulose membrane was incubated with the monoclonal antibody against CCL20 (R and D Systems) or β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. The signals of CCL20 and β-actin were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence luminol reagent.

2.6. Induction of Airway Inflammation

Previously, we and others showed that OVA can elicit rapid and robust inflammation in DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice without an antigen sensitization process. Thus, DO11.10 mice were anesthetized with methoxyflurane (Metofane) and then OVA (Sigma-Aldrich) (100 μg in 50 μl PBS) or an equal amount of bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a nonspecific antigen control was delivered through intranasal inhalation. These mice also intranasally received cell lysates derived from 5 × 107 DO11.10 splenocytes stimulated with either OVA (5 μg/ml) alone or OVA (5 μg/ml) plus OX40 activating antibody (4 μg/ml) for 3 days. Twenty four hours later, the mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation, and lung tissues were collected.

2.7. Histology

For histological evaluation, lungs (right lower lobe) were fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde. Then, the tissues were embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Airway inflammation was assessed by light microscopy according to the degree of cellular infiltration and other pathological change.

2.8. Real Time-PCR

Total RNA from lung homogenates was isolated with RNAeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). First-strand cDNA synthesis was accomplished with oligo (dT)-primed Omniscript reverse transcriptase kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Gene-specific cDNA was amplified by PCR using mouse specific primer pairs (Ccr6 sense: 5′-GGA ACA GTG ACC ATT TGA ACG-3′, and Ccr6 anti-sense: 5′-GGC TCC AGT CCT AAG AAT GTG-3′; β-actin sense, 5′-ATG CCA ACA CAG TGC TGT CT-3′, and β-actin antisense, 5′-AAG CAC TTG CGG TGC ACG AT-3′). The real-time PCR was performed using a RT2 Realtime PCR Master mix (SABiosciences, Fredrick, MD), and running for 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 sec and 55°C for 40 sec. The mRNA level of Ccr6 gene in each sample was normalized to β-actin mRNA and quantified using a formula: 2 [(Ct/β-actin β Ct/gene of testing gene)].

2.9. Statistics

Data are expressed as the average ± SD. Statistical probabilities were evaluated by Student’s t test, with a value of p < 0.05 considered significant.

3. Results

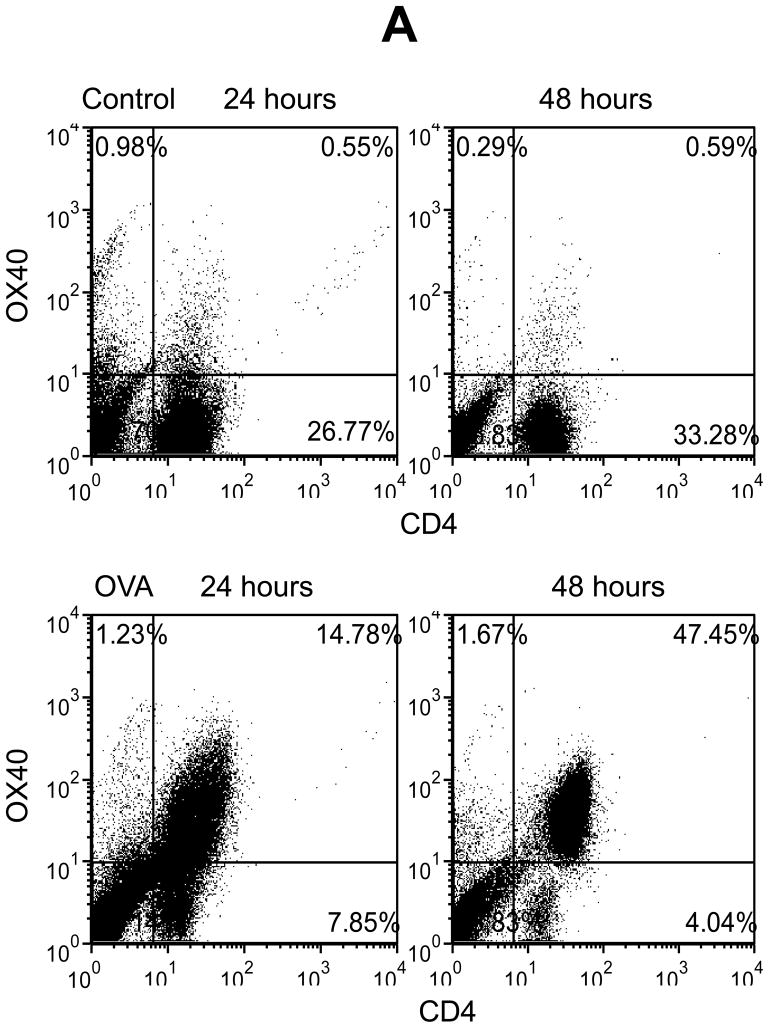

3.1. OVA Induces OX40 Expression Primarily in CD4+ T Cells

To study the potential relationship between OX40 and chemotaxis, we used lymphocytes from the spleen of DO11.10 mice that have a transgenic TCR specifically responding to the OVA323–339 epitope. It is well documented that OX40 induction occurs mainly in activated CD4+ lymphocytes. In addition, some CD8+ cells are reported to express OX40. Therefore, we first performed flow cytometry to define the cell population that expresses OX40 upon antigen challenge in DO11.10 splenocytes. The splenocytes were stimulated in vitro with OVA323–339 peptide up to 72 hours. We then examined the cell surface expression of CD4, CD8, and OX40 on the DO11.10 cells. In the absence of OVA, very few resting CD4+ and CD8+ cells co-expressed OX40 (Fig. 1). However, OVA stimulation caused marked OX40 induction in the CD4+ cells at 24 hours, and the OX40 expression reached the maximal level at 48 hours after the antigen challenge (Fig. 1). In contrast, OX40 was only mildly up-regulated in CD8+ cells (Fig. 1). Thus, CD4+ T lymphocytes appear to be the primary cell population and they were subjected to OX40 targeting in the following experiments.

Fig. 1.

OVA induces OX40 expression primarily in CD4+ T cells in DO11.10 splenocytes. Splenocytes were isolated from DO11.10 mice. These cells were further stimulated with OVA323–339 peptide (5 μg/ml) for 48 hours. Cell surface CD4, CD8, and OX40 expression were analyzed by flow cytometry. Representative plot of CD4, CD8, and OX40 expression from 3 independent studies.

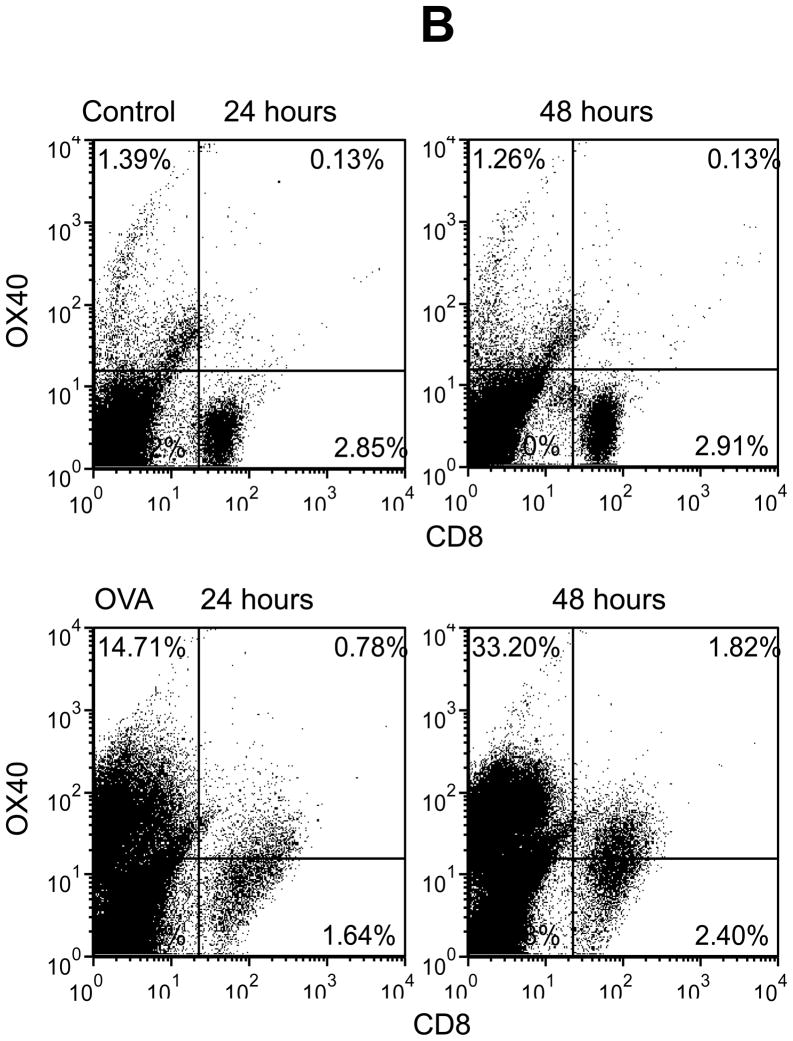

3.2. Further Activation of OX40 Induces Cell-Associated CCL20

CCL20 is an important chemotactic mediator for lymphocytes and dendritic cells, and it is predominantly expressed in the lymph nodes. Moreover, several recent studies reported that activated T cells, especially Th17 cells, produce CCL20 [25–27]. In addition, we and others showed that OVA can induce IL-17 production and Th17 cell generation in DO11.10 mice [29,30]. Moreover, our preliminary study demonstrated that activated Th17 cells expressed OX40, and further stimulation of OX40 enhanced the expression of Th17 effector molecules such as IL-21 and IL-23 receptor. These observations prompted us to determine if activation of OX40 could also induce CCL20 production. We stimulated DO11.10 splenocytes with OVA323–339 peptide (5 μg/ml) in the presence of various concentrations of OX40 activating antibody for 72 hours, and cell-associated CCL20 expression was measured by Western blot analysis. As illustrated in Figure 2, no CCL20 was detected in the splenocytes treated with OVA alone. Nevertheless, further activation of OX40 by OX40 agonistic antibody caused CCL20 up-regulation in a dose dependent manner. This indicates that antigen-induced CCL20 expression is augmented by a synergistic signal from OX40.

Fig. 2.

OX40 activating antibody induces CCL20 expression in DO11.10 splenocytes stimulated with OVA. The splenocytes were harvested from DO11.10 mice. These cells were further stimulated with OVA323–339 peptide (5 μg/ml) and various concentrations of OX40 activating antibody for 48 hours, and CCL20 was examined by Western blot analysis. Representative image of CCL20 induction from 3 independent studies.

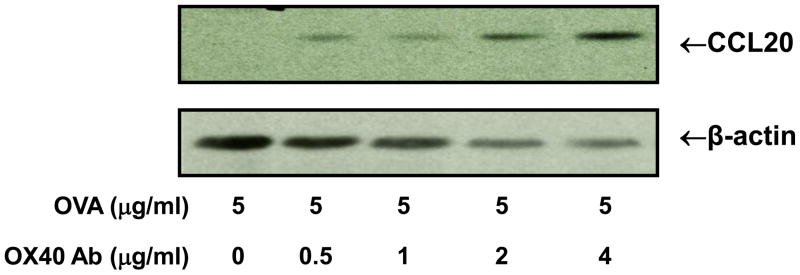

To directly assess whether activated CD4+ cells express CCL20, CD4+ lymphocytes were isolated from the OVA-stimulated DO11.10 splenocytes using EasySep® Mouse CD4+ T Cell Enrichment Kit (StemCell Technologies). Compared to OVA or OX40 activating antibody treatment alone, Westrn blot analysis showed that further OX40 stimulation by OX40 activating antibody significantly up-regulated CCL20 expression in OVA-stimulated CD4+ cells (Fig. 3). Given the fact that OVA induces OX40 largely in CD4+ cells, these data suggest that CD4+ T cells are the major source of CCL20 production in this particular experimental setting.

Fig. 3.

Activated DO11.10 CD4+ cells express CCL20. DO11.10 splenocytes were cultured with and without OX40 activating antibody (4 μg/ml) in the presence of OVA323–339 peptide (5 μg/ml) for 48 hours. CD4+ T lymphocytes were isolated using EasySep® Mouse CD4+ T Cell Enrichment Kit (StemCell Technologies). CCL20 in the CD4+ cells was further analyzed by Western blot. Note: OX40 activating antibody markedly increased the expression of CCL20 in CD4+ T cells. Representative image of CCL20 induction from 3 independent studies.

However, despite the induction of cell-associated CCL20 by OX40 activating antibody, ELISA did not demonstrate that OX40 activating antibody caused a significant increase of secreted CCL20 in the cell culture medium compared to OVA treatment alone (data not shown). This indicates that activation of OX40 alone is responsible for the up-regulation of cellular CCL20, and the secretion of CCL20 requires a non-OX40-mediated mechanism. In addition, we examined whether OX40 activation also up-regulated the expression of CCR6, the unique receptor for CCL20. Unlike its effect on CCL20, OX40 activating antibody did not alter the surface level of CCR6 on DO11.10 CD4+ and CD4- cells (data not shown). This indicates that OX40 signaling only regulates the chemokine activity in the CCL20/CCR6 chemotactic axis.

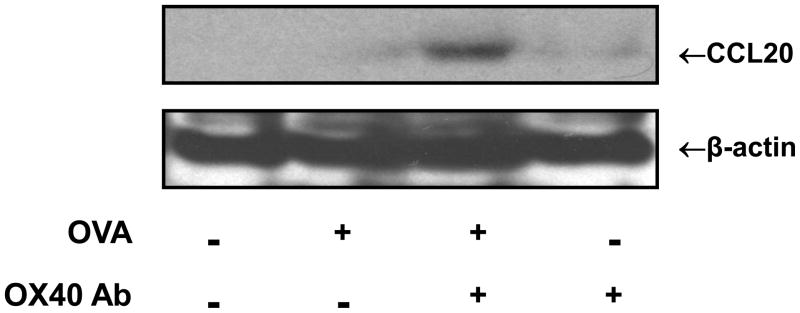

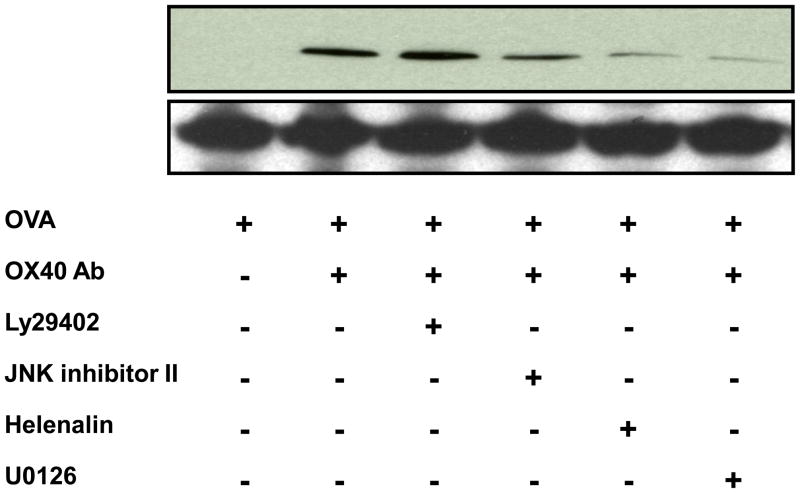

3.3. OX40-induced CCL20 Up-regulation Is Blocked by NF-κB and MEK Inhibitors But Not PI3K and JNK Antagonists

Having demonstrated the novel effect of OX40 on the chemokine expression, we sought to investigate OX40-mediated signaling pathways responsible for CCL20 induction. It is well documented that OX40 exerts its biological function via PI3K, which ultimately activates NF-κB [17,18]. Furthermore, a recent study has shown that IL-17 up-regulates CCL20 through a MEK/NF-κB-dependent mechanism [31]. As a result, we treated DO11.10 splenocytes with 50 μM PI3K inhibitor LY29402, JNK inhibitor II, NF-κB p65 inhibitor helenalin, and MEK 1/2 inhibitor U0126 (Calbiochem, Gibbstown, NJ) up to 72 hours. Moreover, 5 μg/ml OVA and 4 μg/ml OX40 activating antibody were added to the culture media to induce CCL20 production. As demonstrated by Western blot, OX40 activating antibody along with OVA induced CCL20 expression, which was suppressed by the inhibitors of JNK, MEK, and NF-κB in various degrees (Fig. 4). Inhibition of NF-κB and MEK had the most potent antagonistic effect on CCL20 up-regulation. Interestingly, PI3K inhibition did not affect OX40-mediated CCL20 up-regulation (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

NF-κB, JNK, and MEK inhibitors suppress OX40-mediated CCL20 expression in DO11.10 lymphocytes stimulated with OVA. The splenic lymphocytes were harvested from DO11.10 mice. These cells were further stimulated with OVA323–339 peptide (5 μg/ml) in the presence or absence of OX40 activating antibody (4μg/ml) up to 72 hours, and CCL20 was examined by Western blot analysis. Representative image of CCL20 from 2 independent studies.

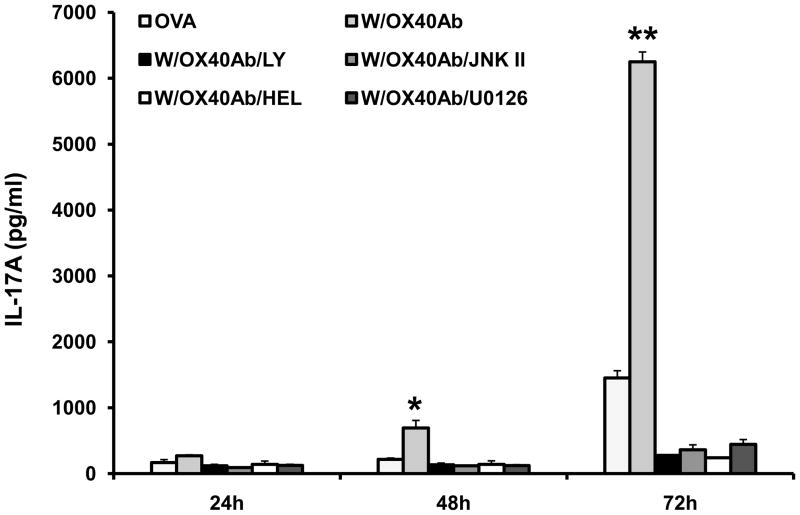

Previously, we showed that OVA evokes a CD4+ cell-dependent and IL-17A-mediated immune response in DO11.10 mice [29], and our preliminary data suggest that OX40 is implicated in the activation and expansion of Th17 cells. Since IL-17 is reported to up-regulate CCL20 [31,32], we then tested whether activation of OX40 enhanced IL-17A production. Furthermore, we explored the possibility that OX40-induced IL-17 production contributed to CCL20 induction. Thus, cell culture media from the above experiment were collected for ELISA to measure the IL-17A level. As shown in Figure 5, OX40 activating antibody synergistically enhanced IL-17A production in the cells stimulated by OVA over time. Inhibition of various signaling pathways (PI3K, JNK, NF-κB, and MEK) significantly mitigated IL-17A expression (Fig. 5). Although both PI3K and JNK antagonists blocked IL-17 in DO11.10 lymphocytes, inhibition of IL-17A by these 2 pathway inhibitors did not markedly suppress CCL20 induction (Fig. 4). This result suggests that IL-17 is not a key or exclusive intermediary molecule during the process of CCL20 induction by OX40.

Fig. 5.

PI3K, NF-κB, JNK, and MEK inhibitors suppress OX40-mediated IL-17A production in DO11.10 splenocytes stimulated with OVA. The splenocytes were harvested from DO11.10 mice. These cells were further stimulated with OVA323–339 peptide (5 μg/ml) in the presence or absence of OX40 activating antibody (4μg/ml) up to 72 hours, and secreted IL-17A was examined by ELISA. Data represent the mean ± SD of 2 independent experiments (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01).

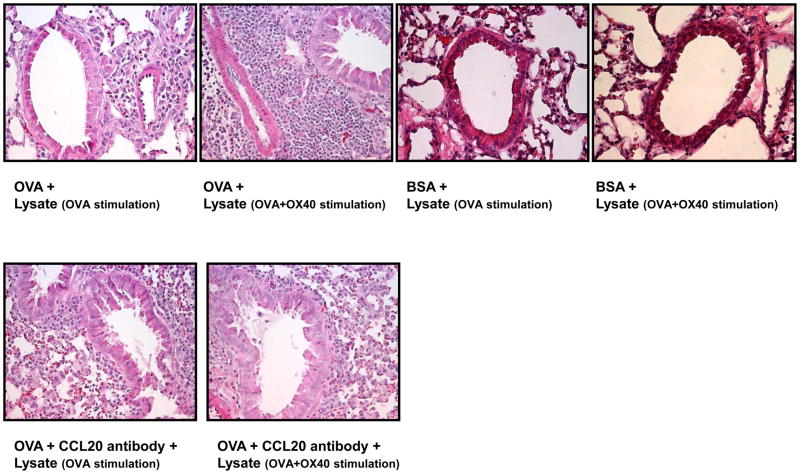

3.4. Neutralization of CCL20 Ameliorates Severe Airway Inflammation Induced by OX40 Activating Antibody-Primed Cell Lysate

In light of above findings, we went on to determine if OX40-induced CCL20 was biologically functional in an in vivo setting. To this end, we stimulated DO11.10 splenocytes with OVA alone or OVA plus OX40 activating antibody in vitro for 72 hours. Then, cell lysates were generated from 5 × 107 cells of each experimental group by repeated freezing and thawing. As evidenced by previous Western blot analysis, the lysate from OX40 activating antibody-treated cells contained inducible CCL20. Next, DO11.10 mice received OVA via intranasal inhalation to induce airway inflammation. In order to assess the biological function of OX40-induced CCL20, these cell lysates were intranasally administered to these recipient animals. Twenty four hours later, lung tissues were harvested for the evaluation of airway inflammation. Compared to the airway exposed to the lysate of the cells treated with OVA alone, the OX40-activated cell lysate induced more substantial infiltration of lymphocyte-predominant inflammatory cells into the peribronchiolar and perivascular lung tissues (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Intranasal inhalation of OVA and OX40 activating antibody-stimulated cell lysate significantly enhances antigen-induced airway inflammation in DO11.10 mice. DO11.10 splenocytes were primed with OVA alone or OVA plus OX40 activating antibody in vitro for 72 hours. Then, cell lysates derived from 5 × 107 cells of each experimental group were administered into the lungs of recipient DO11.10 mice along with additional OVA or BSA (100 μg) via intranasal inhalation. Twenty four hours later, the lungs were collected for histological examination. Note: The cell lysate derived from the cells treated with OX40 activating antibody induced marked peribronchial and perivascular congregation of inflammatory cells, which was substantially attenuated by local treatment of CCL20 neutralizing antibody (n = 3 per group).

However, in order to confirm that this inflammatory response is antigen specific, we also treated DO11.10 mice intranasally with an equal amount of BSA as a control for irrelevant antigen challenge. Our previous study showed that DO11.10 mice do not generate an immune response to BSA [33]. As illustrated in Figure 6, inhalation of BSA did not cause leukocyte infiltration in the lungs of DO11.10 mice. Moreover, in contrast to intranasal OVA challenge, the lysates of the cells activated by the OX40 antibody did not induce airway inflammation (Fig. 6). These results indicate that the cell lysate following OX40 triggering potentiates the immune response to specific antigen but does not itself initiate inflammatory process.

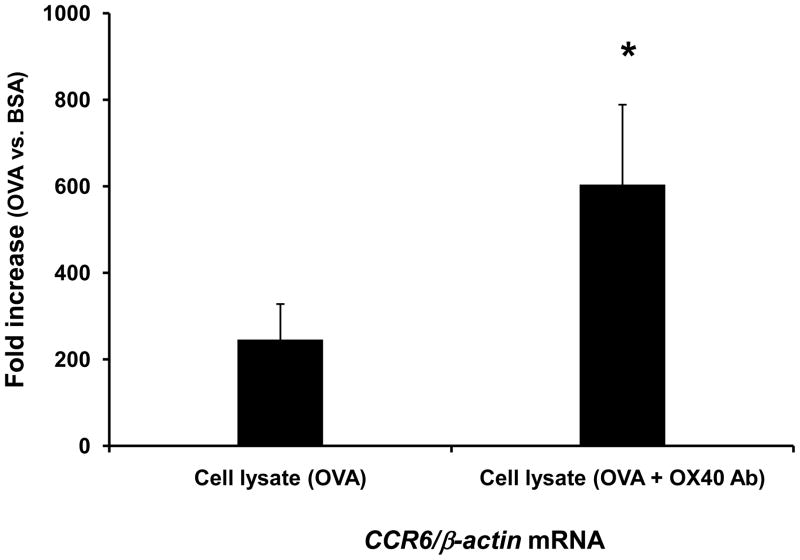

To validate the role of CCL20 in the enhanced airway inflammation, we treated some mice with intranasal delivery of 1 μg CCL20 neutralizing antibody (R and D Systems) along with OVA and cell lysates. The CCL20 antibody significantly attenuated OX40 activating antibody-exaggerated leukocyte recruitment in the lung (Fig 6). This indicates that augmented inflammation is mediated in part by CCL20. Since CCL20 attracts CCR6+ dendritic cells and lymphocytes, we further employed real time-PCR to assess Ccr6 signal in the lungs challenged with BSA and OVA. The group intranasally challenged with OVA and the cell lysate triggered with OVA alone markedly increased Ccr6 signal in the airway compared to BSA-treated counterpart (Fig. 7), suggesting the recruitment of CCR6+ inflammatory cells during antigen-elicited inflammation. Moreover, the Ccr6 mRNA level was further elevated in the lung after inhalation of OX40-triggered cell lysate (Fig. 7). This result indicates that OX40-augmented CCL20 expression is correlated with the increase of CCR6+ cell trafficking.

Fig. 7.

Intranasal inhalation of cell lystate from OVA and OX40 activating antibody-stimulated cells significantly enhances Ccr6 transcript level in antigen-induced airway inflammation. DO11.10 splenocytes were stimulated with OVA alone or OVA plus OX40 activating antibody in vitro for 72 hours. Then, cell lysates derived from 5 × 107 cells of each experimental group were administered into the lungs of recipient DO11.10 mice along with additional OVA or BSA (100 μg) via intranasal inhalation (n = 3 per group). Twenty four hours later, the lungs were harvested for total RNA isolation. The transcription of Ccr6 genes was measured by real time-PCR. Note: The cell lysate derived from the cells treated with OX40 activating antibody significantly enhanced Ccr6 signal in the antigen-challenged airway (*p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

An important finding of this study is the novel effect of OX40 signaling on CCL20 induction. In the presence of antigen stimulation, activation of OX40 with OX40 agonistic antibody up-regulates CCL20 expression. CCL20 plays a critical role in the recruitment of effector lymphocytes and dendritic cells. Recent studies show that Th17 cells express both CCL20 and CCR6 cells [25–27]. It is thought that the Th17 cells during the first round of local infiltration are activated to produce CCL20 [27]. This provides a chemotactic milieu for subsequent leukocyte homing in order to sustain immune response. Our results showed that OX40-induced CCL20 itself did not evoke inflammation in control animals treated with BSA, but augmented the immune response to specific antigen. Thus, CCL20 is likely to facilitate the recruitment of activated leukocytes after the inflammatory process is initiated. This is further consistent with the finding of increased CCR6 transcript in the lung challenged OX40-triggered cell lysate. Although we presumably delivered cell-associated CCL20 to the airway, soluble CCL20 may be released from the membrane by proteinases in the inflamed tissue to exert its function. It is also possible that the absence of activated proteainases in the control lung fails to convert membrane-bound CCL20 to a secreted form, which could explain the lack of CCL20 activity in the BSA-treated group.

Lymphocytes constantly patrol the vascular system and lymph network of the host to perform immune surveillance. Following cognate recognition of antigen, coordinated signaling of TCR and co-stimulatory molecules configures T cells to become effector lymphocytes. Meanwhile, navigation to target sites is an essential step for these activated lymphocytes to contain harmful or antigenic stimuli [12–14,16]. In addition to its well known role in T cell activation, differentiation, and proliferation, our study reveals an expanding role of OX40 signaling in the induction of an important chemokine. Thus, this finding has signified that co-stimulatory molecules also have an ability to directly orchestrate T cell trafficking and migration.

However, our study showed that OX40 signaling alone only enhanced the expression of cell-associated CCL20. It is well documented that certain chemokines such as CXCL1, CXCL8, and CCL2 mainly present as a cell-bound form in the circulation during various physiological and pathological conditions [34–36]. The cell-bound chemokines function as a reservoir to maintain and adjust their systemic and local level. In addition, cell-associated chemokines may play a role in facilitating direct cell-cell contact. By analyzing CCL20 sequences (1–96 amino acids), several studies suggest a putative cleavage site near the NH2 terminal of CCL20 precursor protein, theoretically responsible for converting CCL20 to a secreted form [37,38]. Recently, it has been shown that the secretion of cell-retained chemokines such as CXCL8 requires subsequent metabolic stimulation [39]. In addition, IL-12 is implicated in the release of cell-bound CXCL8 [40]. Therefore, these results point to the fact that chemokine production and secretion are a complex process that entails concerted work of many signaling components. Our data indicate that OX40 is mainly responsible for the induction of CCL20, and the secretion of CCL20 requires different internal and external stimuli.

Consistent with current publications [17,18], we found that both activated CD4+ and CD8+ cells express OX40. Nevertheless, in the studied DO11.10 cell population, CD4+ cells display a significantly higher magnitude of OX40 expression than CD8+ cells. In addition, we showed the production of CCL20 directly by CD4+ cells in response to OX40 activation. Therefore, it is plausible to postulate that CD4+ lymphocytes are a major source of OX40-induced CCL20 expression in this study.

Memory T cell response is a hallmark of adaptive immunity. Rapid mobilization of memory T cells to peripheral inflamed sites exerts a swift recall response to antigen re-challenge. Recent research has demonstrated that OX40 preferentially regulates tissue-infiltrating memory T cells. Moreover, antigen stimulation induces more rapid expression of OX40 in memory CD4+ cells than naive lymphocytes [41]. Although we demonstrate an antigen-specific response, this study is not able to elucidate whether OX40 activation induces CCL20 expression in naïve effector lymphocytes or memory T cells. Nevertheless, these mice were never exposed to OVA, and theoretically should not possess OVA specific memory T cells before the experimentation. Thus, it is feasible to infer that the OX40 effect on CCL20 up-regulation mainly occurs in naïve effector T cells in this study setting.

It has been shown that divergent signaling pathways are implicated in CCL20 induction. An NF-κB p65 binding site has been identified in the promoter region of CCL20 [43–45]. In addition, NF-κB-independent JNK and MEK-mediated pathways are involved in CCL20 transcription [31]. PI3K plays a pivotal role in T cell activation, proliferation, and trafficking as well as chemokine signal transduction [46, 47]. Recent studies have demonstrated that PI3K is one of the OX40 downstream signaling components [17,18]. Activation of PI3K by OX40 ultimately leads to intranuclear translocation of NF-κB. Hence, it was reasonable to postulate that OX40 induced CCL20 expression via a PI3K-dependent pathway. In this study, we found that NF-κB inhibitor, helenalin, abrogates OX40-induced induction of both CCL20 and IL-17, whereas the PI3K antagonist, LY29402, only suppresses the production of IL-17 but not CCL20. The insensitivity of CCL20 expression to the PI3K inhibitor suggests that OX40 utilizes an alternative non-PI3K-mediated pathway to activate NF-κB. In addition, epithelial cells have been shown to express CCL20 [31,45], and this expression can be enhanced by IL-17 [31,32]. Thus, it is possible that activation of OX40 in T cells could indirectly up-regulate epithelial cell-derived CCL20 through the secretion of intermediary IL-17. However, in this study, the PI3K inhibitor does not alter OX40-induced CCL20 expression even when it blocks IL-17 production. Our data suggests that IL-17 does not appear to mediate the induction of CCL20 by OX40. Finally, we found that both JNK and MEK inhibitors exert a profound suppression on OX40-promoted CCL20 expression. This indicates that an AP-1 component such as c-Jun is also implicated in OX40 signaling during the up-regulation of CCL20.

In summary, the present study demonstrates that OX40 induces CCL20 expression in T lymphocytes after direct antigen activation. Furthermore, the OX40-induced CCL20 is biologically functional as evidenced by its chemotactic effect in vivo. This effect is mediated by both NF-κB-dependent and independent pathways. These data clarify the role of OX40 in chemotaxis, and provide an insight into a novel effect of co-stimulatory molecules in orchestrating both T cell up-regulation and migration. This study suggests that lymphocyte cell activation, proliferation, and migration are coupled steps that are efficiently organized by OX40.

Acknowledgments

We thank Judie McDonald for help in preparing the manuscript. This study was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants EY016788 (ZZ), EY013093 (JTR), EY006484 (JTR), and Child Digestive Health and Nutrition Foundation/CCFA Young Investigator Award (ZZ). JTR Funds from the Stan and Madelle Rosenfeld Family Trust, Research to Prevent Blindness, the William and Mary Bauman Foundation, and the Fund for Arthritis and Infectious Disease Research also contributed to this work.

Abbreviations

- APC

Antigen presenting cells

- BAL

Bronchoalveolar lavage

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- H&E

Haematoxylin and eosin

- MHC

Major histocompatibility complex

- OVA

Ovalbumin

- RBC

Red blood cell

- TCR

T cell receptor

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mosmann TR, Li L, Hengartner H, Kagi D, Fu W, Sad S. Differentiation and functions of T cell subsets. Ciba Found Sym. 1997;204:148–54. doi: 10.1002/9780470515280.ch10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Antigen decoding by T lymphocytes: from synapses to fate determination. Nat Immunol. 2001;2(6):487–92. doi: 10.1038/88678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Louten J, Boniface K, de Waal Malefyt R. Development and function of TH17 cells in health and disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(5):1004–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahern PP, Izcue A, Maloy KJ, Powrie F. The interleukin-23 axis in intestinal inflammation. Immunol Rev. 2008;226:147–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tesmer LA, Lundy SK, Sarkar S, Fox DA. Th17 cells in human disease. Immunol Rev. 2008;223:87–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00628.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caspi R. Autoimmunity in the immune privileged eye: pathogenic and regulatory T cells. Immunol Res. 2008;42(1–3):41–50. doi: 10.1007/s12026-008-8031-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Podojil JR, Miller SD. Molecular mechanisms of T-cell receptor and costimulatory molecule ligation/blockade in autoimmune disease therapy. Immunol Rev. 2009;229:337–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00773.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. T-cell co-stimulatory pathways in autoimmunity. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10 (Suppl 1):S3. doi: 10.1186/ar2414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alegre ML, Frauwirth KA, Thompson CB. T-cell regulation by CD28 and CTLA-4. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1:220–8. doi: 10.1038/35105024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coyle AJ, Gutierrez-Ramos JC. The expanding B7 superfamily: increasing complexity in costimulatory signals regulating T cell function. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:203–9. doi: 10.1038/85251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mueller DL. T cells: A proliferation of costimulatory molecules. Curr Biol. 2000;10:R227–30. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00400-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marelli-Berg FM, Cannella L, Dazzi F, Mirenda V. The highway code of T cell trafficking. J Pathol. 2008;214(2):179–89. doi: 10.1002/path.2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.David R, Marelli-Berg FM. Regulation of T-cell migration by co-stimulatory molecules. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;5(Pt 5):1114–8. doi: 10.1042/BST0351114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marelli-Berg FM, Okkenhaug K, Mirenda V. A two-signal model for T cell trafficking. Trends Immunol. 2007;28(6):267–73. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mirenda V, Jarmin SJ, David R, Dyson J, Scott D, Gu Y, Lechler RI, Okkenhaug K, Marelli-Berg FM. Physiologic and aberrant regulation of memory T-cell trafficking by the costimulatory molecule CD28. Blood. 2007;109 (7):2968–77. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-050724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ward SG, Marelli-Berg FM. Mechanisms of chemokine and antigen-dependent T-lymphocyte navigation. Biochem J. 2009;418(1):13–27. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Croft M. The role of TNF superfamily members in T-cell function and diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:271–85. doi: 10.1038/nri2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Croft M, So T, Duan W, Soroosh P. The significance of OX40 and OX40L to T-cell biology and immune disease. Immunol Rev. 2009;229:173–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00766.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weinberg AD, Wegmann KW, Funatake C, Whitham RH. Blocking OX-40/OX-40 ligand interaction in vitro and in vivo leads to decreased T cell function and amelioration of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 1999;162:1818–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flynn S, Toellner KM, Raykundalia C, Goodall M, Lane P. CD4 T cell cytokine differentiation: the B cell activation molecule, OX40 ligand, instructs CD4 T cells to express IL-4 and upregulates expression of the chemokine receptor blr-1. J Exp Med. 1998;188:297–304. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lane P. Role of OX40 signals in coordinating CD4 T cell selection, migration, and cytokine differentiation in T helper (Th)1 and Th2 cells. J Exp Med. 2000;191(2):201–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.2.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Varona R, Zaballos A, Gutiérrez J, Martín P, Roncal F, Albar JP, Ardavín C, Márquez G. Molecular cloning, functional characterization and mRNA expression analysis of the murine chemokine receptor CCR6 and its specific ligand MIP-3α. FEBS Lett. 1998;440:188–94. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01450-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanaka Y, Imai T, Baba M, Ishikawa I, Uehira M, Nomiyama H, Yoshie O. Selective expression of liver and activation-regulated chemokine (LARC) in intestinal epithelium in mice and humans. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:633–42. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199902)29:02<633::AID-IMMU633>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schutyser E, Struyf S, Menten P, Lenaerts JP, Conings R, Put W, Wuyts A, Proost P, Van Damme J. Regulated production and molecular diversity of human liver and activation-regulated chemokine/macrophage inflammatory protein-3α from normal and transformed cells. J Immunol. 2000;165:4470–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.8.4470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirota K, Yoshitomi H, Hashimoto M, Maeda S, Teradaira S, Sugimoto N, Yamaguchi T, Nomura T, Ito H, Nakamura T, Sakaguchi N, Sakaguchi S. Preferential recruitment of CCR6-expressing Th17 cells to inflamed joints via CCL20 in rheumatoid arthritis and its animal model. J Exp Med. 2007;204(12):2803–12. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson NJ, Boniface K, Chan JR, McKenzie BS, Blumenschein WM, Mattson JD, Basham B, Smith K, Chen T, Morel F, Lecron JC, Kastelein RA, Cua DJ, McClanahan TK, Bowman EP, de Waal Malefyt R. Development, cytokine profile and function of human interleukin 17-producing helper T cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(9):950–7. doi: 10.1038/ni1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamazaki T, Yang XO, Chung Y, Fukunaga A, Nurieva R, Pappu B, Martin-Orozco N, Kang HS, Ma L, Panopoulos AD, Craig S, Watowich SS, Jetten AM, Tian Q, Dong C. CCR6 regulates the migration of inflammatory and regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2008;181(12):8391–401. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.12.8391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schutyser E, Struyf S, Van Damme J. The CC chemokine CCL20 and its receptor CCR6. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2003;14(5):409–26. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(03)00049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Z, Zhong W, Spencer D, Chen H, Lu H, Kawaguchi T, Rosenbaum JT. Interleukin-17 causes neutrophil mediated inflammation in ovalbumin-induced uveitis in DO11.10 mice. Cytokine. 2009;46(1):79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marks BR, Nowyhed HN, Choi JY, Poholek AC, Odegard JM, Flavell RA, Craft J. Thymic self-reactivity selects natural interleukin 17-producing T cells that can regulate peripheral inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(10):1125–32. doi: 10.1038/ni.1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kao CY, Huang F, Chen Y, Thai P, Wachi S, Kim C, Tam L, Wu R. Up-regulation of CC chemokine ligand 20 expression in human airway epithelium by IL-17 through a JAK-independent but MEK/NF-kappaB-dependent signaling pathway. J Immunol. 2005;175(10):6676–85. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kanda N, Shibata S, Tada Y, Nashiro K, Tamaki K, Watanabe S. Prolactin enhances basal and IL-17-induced CCL20 production by human keratinocytes. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39(4):996–1006. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Z, Zhong W, Hall MJ, Kurre P, Spencer D, Skinner A, O’Neill S, Xia Z, Rosenbaum JT. CXCR4 but not CXCR7 is mainly implicated in ocular leukocyte trafficking during ovalbumin-induced acute uveitis. Exp Eye Res. 2009 Oct;89(4):522–31. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olszyna DP, De Jonge E, Dekkers PE, van Deventer SJ, van der Poll T. Induction of cell-associated chemokines after endotoxin administration to healthy humans. Infect Immun. 2001;69(4):2736–8. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.4.2736-2738.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marie C, Fitting C, Cheval C, Losser MR, Carlet J, Payen D, Foster K, Cavaillon JM. Presence of high levels of leukocyte-associated interleukin-8 upon cell activation and in patients with sepsis syndrome. Infect Immun. 1997;65(3):865–71. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.3.865-871.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dembinski J, Behrendt D, Heep A, Dorn C, Reinsberg J, Bartmann P. Cell-associated interleukin-8 in cord blood of term and preterm infants. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2002;9(2):320–3. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.9.2.320-323.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hieshima K, Nagira M, Imai T, Kusuda J, Ridanpää M, Takagi S, Nishimura M, Kakizaki M, Nomiyama H, Yoshie O. Molecular cloning of a novel human CC chemokine secondary lymphoid-tissue chemokine that is a potent chemoattractant for lymphocytes and mapped to chromosome 9p13. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(31):19518–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.31.19518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rossi DL, Vicari AP, Franz-Bacon K, McClanahan TK, Zlotnik A. Identification through bioinformatics of two new macrophage proinflammatory human chemokines: MIP-3alpha and MIP-3beta. J Immunol. 1997;158(3):1033–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Siddiqui RA, Akard LP, Garcia JG, Cui Y, English D. Chemotactic migration triggers IL-8 generation in neutrophilic leukocytes. J Immunol. 1999;162(2):1077–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ethuin F, Delarche C, Benslama S, Gougerot-Pocidalo MA, Jacob L, Chollet-Martin S. Interleukin-12 increases interleukin 8 production and release by human polymorphonuclear neutrophils. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;70(3):439–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salek-Ardakani S, Croft M. Regulation of CD4 T cell memory by OX40 (CD134) Vaccine. 2006;24:872–83. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.07.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salek-Ardakani S, Song J, Halteman BS, Jember AG, Akiba H, Yagita H, Croft M. OX40 (CD134) controls memory T helper 2 cells that drive lung inflammation. J Exp Med. 2003;198(2):315–24. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sugita S, Kohno T, Yamamoto K, Imaizumi Y, Nakajima H, Ishimaru T, Matsuyama T. Induction of macrophage-inflammatory protein-3alpha gene expression by TNF-dependent NF-kappaB activation. J Immunol. 2002;168(11):5621–28. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Battaglia F, Delfino S, Merello E, Puppo M, Piva R, Varesio L, Bosco MC. Hypoxia transcriptionally induces macrophage-inflammatory protein-3alpha/CCL-20 in primary human mononuclear phagocytes through nuclear factor (NF)-kappaB. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83(3):648–62. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0607349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sirard JC, Didierlaurent A, Cayet D, Sierro F, Rumbo M. Toll-like receptor 5-and lymphotoxin beta receptor-dependent epithelial Ccl20 expression involves the same NF-kappaB binding site but distinct NF-kappaB pathways and dynamics. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1789(5):386–94. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Okkenhaug K, Vanhaesebroeck B. PI3K in lymphocyte development, differentiation and activation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3(4):317–30. doi: 10.1038/nri1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fruman DA, Bismuth G. Fine tuning the immune response with PI3K. Immunol Rev. 2009;228(1):253–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]