Abstract

We evaluated the association between energy balance and risk of bladder cancer and assessed joint effects of genetic variants in the mTOR pathway genes with energy balance. The study included 803 Caucasian bladder cancer patients and 803 healthy Caucasian controls matched to cases by age (± 5 years) and gender. High energy intake (OR=1.60; 95% CI=1.23-2.09) and low physical activity (OR=2.82; 95% CI=2.10-3.79) were each associated with significantly increased risk of bladder cancer with dose-response trends (P for trend<0.001). However, obesity (BMI ≥30) was not associated with the risk. Among 222 SNPs, 28 SNPs located in 6 genes of mTOR pathway were significantly associated with the risk. Further, the risk associated with high energy intake and low physical activity was only observed among subjects carrying a high number of unfavorable genotypes in the pathway. Moreover, when physical activity, energy intake and genetic variants were analyzed jointly, the study population was clearly stratified into a range of low to high risk subgroups as defined energy balance status. Compared to subjects within the most favorable energy balance category (low energy intake, intensive physical activity, low number of unfavorable genotypes), subjects in the worst energy balance category (high energy intake, low physical activity, and carrying seven or more unfavorable genotypes) had 21.93-fold increased risk (95% CI=6.7 to 71.77). Our results provide the first strong support that physical activity, energy intake and genetic variants in the mTOR pathway jointly influence bladder cancer susceptibility and these results have implications in bladder cancer prevention.

Keywords: bladder cancer, energy intake, physical activity, obesity, PI3K-AKT-mTOR Pathway

Introduction

Bladder cancer is the fourth most common cancer in U.S. men and the second most common urologic malignancy, with about of 70,980 new cases and about 14,330 deaths in 2009 (1). Major risk factors of bladder cancer include male gender, old age, tobacco smoking, and occupational exposure to aromatic amines (e.g., in the dye and rubber industries)(2). Energy balance, or the ability to maintain body weight by balancing energy intake with energy expenditure, has been gaining increasing attention as an etiologic factor of cancers (3). A positive energy balance, in which energy intake exceeds energy expenditure over a prolonged time, leads to the development of overweight or obesity (4). The prevalence of obesity has reached epidemic levels in many parts of the world. In the United States, nearly two thirds of adults are currently overweight or obese (5). Epidemiologic studies have provided sufficient evidences to support obesity as a risk factor for cancers of the esophagus (6), colon and rectum (7), endometrium (8) and kidney (6, 9). Modulation of energy balance, via increased physical activity, has been shown in epidemiological studies to reduce the risk of many cancers, including cancers of colon (10), endometrium (11) and breast (12). However, the association between physical activity and bladder cancer risk has been inconsistent in the literature (13-20) and previous studies have also generated conflicting results regarding the association between obesity and bladder cancer (14, 15, 20-34).

It is increasingly recognized that genetic susceptibility contributes to bladder carcinogenesis (35). Inter-individual differences in genes that control the energy balance pathways may cause defects in energy metabolism and consequently contribute to increased cancer risk (36). Several hormones and growth factors serving as intermediate and long-term communicators of nutritional state have been implicated in both energy balance and carcinogenesis (37). Evidences suggest that many of these cellular growth and metabolism involve signaling through the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin pathway (PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway or mTOR pathway) (38). The mTOR pathway was first described about 15 years ago in studies investigating the mechanism of action of rapamycin (inhibitor of mTOR) (39). mTOR is a member of the phosphoinositide-3-kinase-related kinase family, which is centrally involved in cell growth regulation, proliferation control and cancer cell metabolism (40). Engagement of mTOR pathway allows both intracellular and environmental factors, such as energy supply and growth factors, to affect cell growth, proliferation, survival, and metabolism (37). Evidence suggests that dietary energy balance could modulate cellular signaling through cell-surface receptors, affecting activation or deactivation of multiple downstream genes within the mTOR pathway (38). Thus, Genetic variations of mTOR pathway related genes and its interaction with energy balance may lead to dysregulation of proliferation or decreased cell death, and subsequently increased cancer risk.

In this large case-control study, we evaluated whether there is an association between energy intake, physical activity, obesity and bladder cancer risk. We also assessed whether genetic polymorphisms in mTOR pathway related genes may interact with energy balance to modify bladder cancer risk.

Methods

Study population

This case-control study started patient recruitment in 1999 and is currently on-going. Bladder cancer patients were recruited from The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center and Baylor College of Medicine. The procedures for cases recruitment and eligibility criteria were described previously (41). Briefly, all patients had histopathologically confirmed bladder cancer and had received no prior chemotherapy or radiotherapy upon recruitment. There are no restrictions of recruitment on age, sex, race, or cancer stage. The control subjects were healthy individuals without prior history of cancer (except nonmelanoma skin cancer). They were recruited from the Kelsey-Seybold clinics, the largest private multispecialty physician group consisting of more than 23 clinics and more than 300 physicians in the Houston metropolitan area. The majority of control participants were healthy individuals coming to the clinics for annual health check-ups. Controls were frequency matched to the patients by age (±5 years), sex, and ethnicity. The potential control subjects were first inquired with a short survey form to elicit willingness to participate in the study and to provide preliminary demographic data for matching. A Kelsey-Seybold staff member provided the short survey form to each potential control subject during clinical registration. The potential control subjects were contacted by telephone at a later date to confirm their willingness to participate in the study and to schedule an in-person interview at a Kelsey-Seybold clinic convenient to the participant. Written informed consent was obtained from all study subjects. The response rates for cases and controls were 92% and 76.7%, respectively (41). The study is approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of M.D. Anderson, Kelsey-Seybold clinics and Baylor College of Medicine. Due to the small number of minority populations, we restricted the analysis to Caucasians in this study.

Data collection

After obtaining written informed consent, trained M.D. Anderson staff interviewers administered a risk factor questionnaire to all participants. Data collected include demographic characteristics (age, gender, ethnicity, etc.), occupation history, tobacco use history, medical history, and family history of cancer. In addition to the risk factor questionnaire, a 45 minutes food-frequency questionnaire was administered to assess dietary intake during the year prior to diagnosis in the cases and the year prior to the interview in the control subjects. The food frequency questionnaire was derived from a modified version of the Health Habits and History Questionnaire (HHHQ) developed by the National Cancer Institute. The questionnaire includes a semi-quantitative food frequency list of food and beverage items, ethnic foods commonly consumed in the Houston area, an open-ended section, and dietary behaviors such as dining at restaurant and food preparation methods. The validity and reliability of the questionnaire has been documented previously (42). Daily energy intake was estimated by the type and amounts of the food and expressed as an average amount of calorie per day.

During the interview, participants were asked about their current weight and height, as well as their weight 1 and 5 years prior to the date of interview (or diagnosis date for cases). These variables were used to derive body mass index (BMI), calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. In the current study, we used the weight 5 years ago to calculate BMI. Participants also reported the average amount of time they spent on five broad groups of activities during the previous year and during their adult life. Individual activities included active sports such as tennis or racquetball, physical exercises such as aerobics, weight training, jogging or running, swimming, walking (including walking for golf), cycling, gardening or yard work, hunting, housework and other strenuous exercises. A metabolic equivalent task (MET) value was assigned based on the energy cost of each group of activity (43, 44). MET was defined as the ratio of working metabolic rate to a standard metabolic rate, where 1 MET corresponds to resting metabolic rate obtained during quiet sitting. The energy expenditure from physical activity was calculated as the MET value of each activity multiplied by the frequency of each activity and then summed across all activities. In this study, we estimated the frequency of each activity based on the reported activities in the year prior to the interview. Immediately after the interview, each participant donated a blood sample for molecular analyses.

An individual who had never smoked or had smoked less than 100 cigarettes in his or her lifetime was defined as a never smoker. An individual who had smoked at least 100 cigarettes in his or her lifetime but had quit more than 12 months before diagnosis (for cases) or before the interview (for controls) was classified as a former smoker. Current smokers were those who were currently smoking or quit less than 12 months before diagnosis (for cases) or before the interview (for controls).

SNPs selection and genotyping

The SNP selection procedures were described previously (45). Briefly, we compiled our gene list using SNPs3D bioinformatic tools, which is a web-based literature mining approach to select genes according to a set of user-defined query terms of human diseases or biological processes. Then we performed literature review to refine the gene list in PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway. We identified tagging SNPs (tSNPs) from the HapMap database (http://www.hapmap.org). All selected SNPs met the following criteria: r2 ≥0.8, minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥0.05 in Caucasians, and within 10 kb upstream of the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) and 10 kb downstream of the 3′ UTR of the gene. In addition, we included potentially functional SNPs (e.g., coding SNPs and SNPs in UTR, promoter, and splicing site). We also supplemented SNPs in this pathway previously genotyped as part of our genome-wide association study (46). For genes with less importance, only potentially functional SNPs with MAF > 0.01 (e.g. coding SNPs and SNPs in untranslated region, promoter and splicing site) were selected.

Genotyping of the SNPs was performed using the Illumina Infinium II Assay as described previously (45).Briefly, genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood using the QIAamp DNA Blood Maxi Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The genotyping was done using Illumina’s iSelect custom SNP array platform according to the manufacturer’s Infinium II assay protocol (Illumina, San Diego, CA) with 750 ng of input DNA for each sample. All genotyping data were analyzed and exported using BeadStudio software (Illumina). The average call rate for the SNP array was 99.7% (45)

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by using STATA 10.0 (College station, TX, USA). Distributions in categorical variables between cases and controls were evaluated by the χ2 test. Differences between cases and controls in continuous variables were tested using the Student’s t-test or Kruskal-Wallis test (for continuous variables not normally distributed). Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) was tested for each SNP using the goodness-of-fit Chi-Square test to compare the observed with the expected frequency of genotypes in controls. BMI was divided into three groups: normal (BMI lower than 25 kg/m2), overweight (BMI greater than or equal to 25 kg/m2 but less than 30 kg/m2) and obese (BMI greater than 30 kg/m2). For physical activity, the cutoff points were set on tertile distribution of the MET scores in controls: low (less than 9), medium (greater than or equal to 9 but less than 25), and intensive (great than 25). Total energy intake was also categorized into three groups based on the cutoff points of tertile distribution in controls: low(less than 1738 Kcal/day), medium (greater than or equal to1738 Kcal/day but less than 2313 Kcal/day), and high (greater than 2313 Kcal/day). Multivariate logistic regression model was applied to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) associated with physical activity, obesity and energy intake as well as main effects of SNPs.

For SNP analysis, we tested three different genetic models, including dominant model, recessive model and additive model. The best-fitting model was the one with the smallest P value among the three models. If the genotype counts for the homozygous variant genotype were less than five in cases and controls combined, we only considered the dominant model that had the highest statistical power. We calculated the q-value to account for multiple comparisons (48). The q-value measured the proportion of false positive incurred (false discovery rate) when particular test of SNP was called significant. To evaluate the modification effects from the genetic variants in the pathway, we summed up adverse genotypes (genotypes associated with significantly increased risk in the main effect analysis after adjustment for multiple comparisons) for each subject. In the case when multiple SNPs within a haplotype block were found to have significant main effect, only one most significant SNP with the smallest P-value will be selected to be summed up with other variants in the pathway.

Interactions between variables were included in the multivariate model as cross-product terms and the significance was assessed using the likelihood ratio test. To explore higher order gene-gene and gene-environment interactions, we applied a recursive partitioning technique. The recursive partitioning was derived from the methodology of Classification and Regression Tree analysis (CART). A tree-based model was created and allowed identifying effect modifications between variables that are less visible by traditional logistic regression. CART analysis was performed using the HelixTree (Golden Helix, MT, USA) software. All P values were two sided with a significance level of 0.05.

Results

The study included 803 bladder cancer patients and 803 controls matched to cases by age (±5 years) and sex. Although the study is frequency matched but not one-to-one matched, the same number of cases and controls were included for genotyping. We restricted the analysis to Caucasians due to the small sample size of minorities and the concern of population stratification. By study design, cases and controls were well matched in terms of age and sex (Table 1). As predicted, there was significant difference in the distribution of smoking status (P<0.001) with higher percentage of current smokers in cases and higher percentage of never smokers in controls (P<0.001). Among smokers, cases reported to have higher pack years of smoking than controls (38.0 vs. 22.5, P<0.001). Cases also had higher daily energy intake than controls (2218.95 Kcal/day vs. 1991.39 Kcal/day, P<0.001). Further, compared to controls, cases were less likely to take part in physical activities (P<0.001). For example, the percentage of subjects took part in intensive activities was 33.33% in controls but only 16.56% in cases (P<0.001). No significant difference was found in BMI between the two groups (cases: 27.31 kg/m2 vs. controls: 27.51 kg/m2, P=0.385).

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of cases and controls

| Characteristics | Case n=803, n(%) |

Control n=803, n(%) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Men | 640(79.70) | 639(79.58) | 0.951† |

| Women | 163(20.30) | 164(20.42) | |

| Age (year) | |||

| Mean(SD) | 64.73(11.13) | 63.82(10.88) | 0.098* |

| Smoking | |||

| Never | 212(26.40) | 355(44.21) | <0.001† |

| Former | 404(50.31) | 381(47.45) | |

| Current | 187(23.29) | 67(8.34) | |

| Smoking packyear | |||

| Median(Range) | 38(0.05-176) | 22.5(0.05-165) | <0.001‡ |

| Energy intake (Kcal/day) | |||

| Median(Range) | 2218.95(500.81- 17207.67) |

1991.39(350.13- 7354.53) |

<0.001‡ |

| Energy intake category | |||

| Low (<1738 Kal/day) | 219(28.82) | 258(33.25) | <0.001† |

| Medium (1738-2312 Kcal/day) |

195(25.66) | 259(33.38) | |

| High (≥2313 Kcal/day) | 346(45.53) | 259(33.38) | |

| Physical activity | |||

| Intensive (≥25) | 129(16.56) | 265(33.33) | <0.001† |

| Medium (9-24) | 325(41.72) | 329(41.38) | |

| Low (<9) | 325(41.72) | 201(25.28) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| Mean(SD) | 27.31(4.59) | 27.51(4.65) | 0.385* |

| BMI category | |||

| Normal (<25 kg/m2) | 236(30.26) | 233(29.23) | 0.700† |

| Overweight (25-29 kg/m2) | 367(47.05) | 369(46.30) | |

| Obese (≥30 kg/m2) | 177(22.69) | 195(24.47) |

: χ2 test;

: Kruskal-Wallis test;

:Student t-test;

BMI:Body mass index

Among the 222 SNPs examined, 213 SNPs were in agreement with HWE. In the main effect of single SNP analysis, after adjusting for age, sex, tobacco smoking, BMI, energy intake and physical activity, 28 out of 222 SNPs showed significant associations with bladder cancer risk (note that 27 out of the 28 SNPs were in agreement with HWE .One SNP rs2271612 had a HWE test P value of 0.03). These SNPs were located in 6 genes within mTOR pathway, including AKT3, RHEB, RPS6KA5, IRS2, TSC2 and RAPTOR. Because multiple SNPs within the RAPTOR gene showed significant main effect, only one SNP with the smallest P-value within the same haplotype block was selected, resulting in 17 SNPs with significant main effect (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association between mTOR pathway genetic polymorphisms and bladder cancer

| Gene | SNP† | Alleles (Major/minor) |

MAF‡ |

Best fitting model |

P for H-W& |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Control | Model | OR(95%CI)* | P value | ||||

| AKT3 | rs2994329 | G/A | 0.20 | 0.20 | Recessive | 2.11(1.21-3.67) | 0.008 | 0.262 |

| RHEB | rs717775 | A/C | 0.30 | 0.28 | Recessive | 1.60(1.09-2.36) | 0.016 | 0.361 |

| RPS6KA5 | rs7155799 | G/A | 0.22 | 0.24 | Recessive | 0.57(0.35-0.94) | 0.029 | 0.612 |

| IRS2 | rs9515120 | G/A | 0.07 | 0.05 | Dominant | 1.57(1.12-2.19) | 0.009 | 0.889 |

| TSC2 | rs2073636 | G/A | 0.41 | 0.37 | Additive | 1.18(1.01-1.38) | 0.036 | 0.721 |

| RAPTOR | rs11653499 | G/A | 0.31 | 0.26 | Additive | 1.22(1.03-1.44) | 0.019 | 0.662 |

| RAPTOR | rs7212142 | G/A | 0.43 | 0.38 | Recessive | 1.36(1.02-1.82) | 0.037 | 0.463 |

| RAPTOR | rs7211818 | A/G | 0.24 | 0.21 | Recessive | 2.16(1.35-3.47) | 0.001# | 0.637 |

| RAPTOR | rs7208536 | G/A | 0.28 | 0.24 | Recessive | 1.86(1.20-2.89) | 0.005 | 0.274 |

| RAPTOR | rs4969444 | G/A | 0.20 | 0.17 | Recessive | 2.16(1.22-3.82) | 0.009 | 0.744 |

| RAPTOR | rs2048753 | G/A | 0.27 | 0.24 | Additive | 1.22(1.02-1.45) | 0.030 | 0.513 |

| RAPTOR | rs2672890 | G/A | 0.18 | 0.20 | Dominant | 0.79(0.63-0.99) | 0.044 | 0.542 |

| RAPTOR | rs9897968 | G/A | 0.21 | 0.23 | Dominant | 0.79(0.63-0.98) | 0.036 | 0.823 |

| RAPTOR | rs1877926 | G/A | 0.35 | 0.33 | Recessive | 1.43(1.02-1.99) | 0.036 | 0.886 |

| RAPTOR | rs2271612 | A/G | 0.49 | 0.47 | Recessive | 1.39(1.07-1.81) | 0.013 | 0.033 |

| RAPTOR | rs6420481 | A/G | 0.43 | 0.42 | Recessive | 1.36(1.02-1.80) | 0.034 | 0.135 |

| RAPTOR | rs1062935 | A/G | 0.50 | 0.48 | Recessive | 1.29(1.00-1.66) | 0.047 | 0.219 |

:In raptor gene, we only listed one significant SNP with the smallest P value;

:MAF: Minor allele frequency;

Adjusting for age, sex, tobacco smoking, BMI, energy intake and physical activity;

: q value less than 0.1;

: Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium test among controls

SNPs rs7211818 in the RAPTOR gene remained significant after adjustment for multiple comparisons at the 10% level. The homozygous variant GG genotype was associated to an increased risk of bladder cancer, with ORs (95% CIs) of 2.16(1.35-3.47). To assess the accumulative effects of all SNPs in the pathway, we further categorized the subjects into three risk groups according to the number of unfavorable genotypes: low-risk group (0-4 unfavorable genotypes), medium-risk group (5-6 unfavorable genotypes), and high-risk group (≥7 unfavorable genotypes). Unfavorable genotypes were defined by referring the ORs of genotypes showing a significant association (P<0.05) in single SNP analysis in the best fitting model (As shown in Table 2). Compared with subjects in low-risk group, the risks for medium-risk group and high-risk group were significantly elevated, with the ORs of 1.50 (95% CI= 1.17 to 1.93, P=<0.001) and 2.42 (95% CI=1.81 to 3.23, P<0.001), respectively.

We next assessed the main effects of energy balance-related variables, namely energy intake, physical activity and BMI. Compared with subjects with low energy intake (less than 1738 Kcal/day), the OR for medium energy intake (1738-2312 Kcal/day) was 0.95 (95% CI=0.72 to1.25) but increased to 1.60 (95% CI= 1.23 to 2.09, P=0.001) for high energy intake category (greater than 2313 Kcal/day) (Table 3). Further, the increased risk associated with high energy intake was only significant in former (OR=1.60; 95% CI=1.11 to 2.32; P=0.012) and current smokers (OR=2.31; 95% CI=1.02 to 5.22; P=0.044) but not in never smokers. The interaction between smoking status and energy intake was statistically significant (P for interaction=0.033). For physical activity, compared with subjects with intensive physical activity (MET scores great than 25), subjects with medium physical activity (MET scores greater than or equal to 9 but less than 25) was at 1.87-fold (95% CI= 1.42 to 2.47; P<0.001) increased risk and the risk further increased to 2.82-fold (95% CI= 2.10 to 3.79; P<0.001) among subjects with low physical activity (MET scores less than 9) (Table 3). When stratified by smoking status, significantly increased risk of low physical activity was observed in all subjects regardless of smoking status (Table 3). For example, the ORs of low physical activity was 2.17 (95% CI=1.32 to 3.57; P=0.002), 2.87 (95% CI=1.89 to 4.35; P<0.001) and 6.33 (95% CI=2.68 to 14.97; P<0.001) for never, former and current smokers, respectively. However, no association was observed for BMI with the ORs of overweight and obese subjects to be 0.95 (95% CI= 0.73 to 1.23) and 0.79 (95% CI= 0.59 to 1.07), respectively, as compared to the normal BMI category (Table 3). No association was observed in stratified analysis by smoking status (Table 3).

Table 3.

The association between energy balance and bladder cancer stratified by smoking status

| Overall risk | Never smoker | Former smoker | current smoker | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Case/Control | OR(95%CI)† | P value |

Case/Control | OR(95%CI)† | P value |

Case/Control | OR(95%CI)† | P value |

Case/Control | OR(95%CI)† | P value |

P for interaction |

| Energy intake | 0.033 | ||||||||||||

| Low | 219/258 | Ref. | 73/119 | Ref. | 99/121 | Ref. | 47/18 | Ref. | |||||

| Medium | 195/259 | 0.95(0.72-1.25) | 0.733 | 49/120 | 0.67(0.42-1.06) | 0.086 | 113/114 | 1.35(0.92-1.98) | 0.128 | 33/25 | 0.62(0.27-1.46) | 0.275 | |

| High | 346/259 | 1.60(1.23-2.09) | 0.001 | 77/103 | 1.50(0.96-2.36) | 0.076 | 165/133 | 1.60(1.11-2.32) | 0.012 | 104/23 | 2.31(1.02-5.22) | 0.044 | |

| P for trend | <0.001 | 0.1 | 0.013 | 0.011 | |||||||||

| Physical activity | 0.189 | ||||||||||||

| Intensive | 129/265 | Ref. | 45/123 | Ref. | 68/122 | Ref. | 16/20 | Ref. | |||||

| Medium | 325/329 | 1.87(1.42-2.47) | <0.001 | 91/135 | 1.97(1.24-3.14) | 0.004 | 173/169 | 1.69(1.16-2.47) | 0.006 | 61/25 | 3.15(1.32-7.49) | 0.009 | |

| Low | 325/201 | 2.82(2.10-3.79) | <0.001 | 71/92 | 2.17(1.32-3.57) | 0.002 | 148/87 | 2.87(1.89-4.35) | <0.001 | 106/22 | 6.33(2.68-14.97) | <0.001 | |

| P for trend | <0.001 | 0.003 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||||

| BMI category | 0.687 | ||||||||||||

| Normal | 236/233 | Ref. | 59/100 | Ref. | 110/113 | Ref. | 67/20 | Ref. | |||||

| Overweight | 367/369 | 0.95(0.73-1.23) | 0.674 | 98/163 | 0.85(0.54-1.33) | 0.477 | 195/175 | 1.11(0.77-1.58) | 0.577 | 74/31 | 0.64(0.30-1.38) | 0.257 | |

| Obese | 177/195 | 0.79(0.59-1.07) | 0.131 | 48/87 | 0.76(0.45-1.27) | 0.297 | 87/92 | 0.84(0.55-1.28) | 0.409 | 42/16 | 0.79(0.33-1.86) | 0.584 | |

| P for trend | 0.136 | 0.296 | 0.443 | 0.565 | |||||||||

:Adjusting for age, sex, tobacco smoking, energy intake, BMI and physical activity where appropriate

To explore how genotypes in the mTOR pathway may modify the association between energy-balance related variables and bladder cancer, we performed stratified analysis of these variables by the number of unfavorable genotypes (Table 4). For energy intake, no significant association between energy intake and bladder cancer risk was observed among subjects carrying 0-4 unfavorable genotypes. However, among subjects carrying 5-6 unfavorable genotypes, high energy intake conferred a significant 1.66-fold (95% CI= 1.05 to 2.62; P=0.031) increased risk. Among subjects carrying 7 or more adverse genotypes, the risk of high energy intake elevated to 2.11-fold (95% CI= 1.16 to 3.87; P=0.015).

Table 4.

The association between energy balance and bladder cancer stratified by the number of unfavorable genotypes

| Variables | 0-4 unfavorable genotypes |

5-6 unfavorable genotypes |

≥7 unfavorable genotypes |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case/Control | OR(95%CI)† | P value | Case/Control | OR(95%CI)† | P value | Case/Control | OR(95%CI)† | P value | |

| Energy intake | |||||||||

| Low | 82/107 | Ref. | 72/85 | Ref. | 60/50 | Ref. | |||

| Medium | 63/124 | 0.75(0.48-1.19) | 0.223 | 68/80 | 1.07(0.66-1.73) | 0.790 | 61/48 | 1.19(0.67-2.12) | 0.548 |

| High | 116/126 | 1.31(0.86-2.00) | 0.212 | 135/92 | 1.66(1.05-2.62) | 0.031 | 87/38 | 2.11(1.16-3.87) | 0.015 |

| P for trend | 0.155 | 0.026 | 0.014 | ||||||

| Physical activity | |||||||||

| Intensive | 49/123 | Ref. | 41/85 | Ref. | 34/50 | Ref. | |||

| Medium | 109/146 | 1.82(1.17-2.84) | 0.008 | 116/113 | 2.00(1.22-3.28) | 0.006 | 95/59 | 2.01(1.12-3.63) | 0.020 |

| Low | 108/95 | 2.39(1.49-3.81) | <0.001 | 128/68 | 3.72(2.22-6.23) | <0.001 | 82/30 | 3.45(1.76-6.76) | <0.001 |

| P for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| BMI category | |||||||||

| Normal | 82/111 | Ref. | 70/70 | Ref. | 75/43 | Ref. | |||

| Overweight | 125/173 | 1.02(0.67-1.55) | 0.933 | 143/121 | 1.22(0.77-1.92) | 0.399 | 95/62 | 0.72(0.41-1.25) | 0.241 |

| Obese | 59/81 | 1.00(0.61-1.64) | 0.992 | 71/75 | 0.83(0.50-1.39) | 0.482 | 43/34 | 0.54(0.28-1.04) | 0.067 |

| P for trend | 0.987 | 0.450 | 0.065 | ||||||

:Adjusting for age, sex, tobacco smoking, energy intake, BMI and physical activity where appropriate

There was a 2.39-fold increased risk associated with low physical activity among subjects carrying low number of unfavorable genotypes (0-4 unfavorable genotypes). However, among subjects carrying 5-6 unfavorable genotypes, those low physical activity experienced 3.72-fold increased risk (95% CI= 2.22 to 6.23; P<0.001). Among subjects carrying 7 or more unfavorable genotypes, the risk of low physical activity was 3.45-fold (95% CI= 1.76 to 6.76; P<0.001). BMI was not associated with bladder cancer risk among subjects regardless of number of the unfavorable genotypes, although a slightly non-significant inverse association was observed among subjects carrying 7 or more unfavorable genotypes.

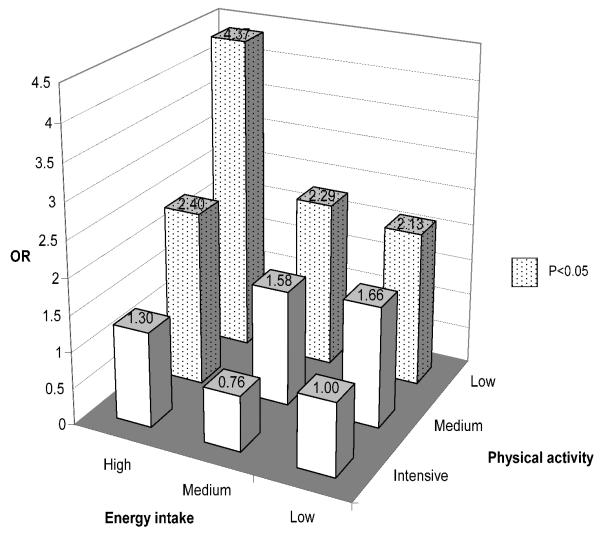

We next assessed joint effects of energy balance related variables and genotypes. Because physical activity and energy intake, but not BMI, was each associated with bladder cancer risk, we first assessed joint effects of physical activity and energy intake (Figure 1). Compared to the reference group, subjects with low energy intake and intensive physical activity, significant increased risks were observed in several subgroups (Figure 1) with the highest risk occurred in subjects with high energy intake and low physical activity (OR=4.37; 95% CI=2.59 to 7.37; P<0.001).

Figure 1.

Joint effects of energy intake and physical activity in the risk of bladder cancer

Note: The number on top of each bar is the odds ratio. ORs with P<0.05 are represented by dotted bars while ORs not significant in blank bars. The reference group is set as low physical activity and high energy intake.

Joint effects of energy intake, physical activity and mTOR pathway genes were shown in Table 5. In this analysis, we developed an energy balance index to collapse the physical activity and energy intake combinations (see Table 5 footnotes for the definition) and then analyzed the integrated index with the number of unfavorable genotypes. As shown in Table 5, the reference group was subjects with low energy intake, intensive physical activity and carrying low number of unfavorable genotypes (0-4 unfavorable genotypes). Compared to this reference group, the highest risk was observed in subjects located in the worst energy balance category: subjects with high energy intake, low physical activity, and carrying ten or more unfavorable genotypes. The risk was more than 21.93-fold (OR=21.93; 95% CI=6.70 to 71.77; P<0.001) (Table 5).

Table 5.

The association between energy balance index and bladder cancer stratified by the number of unfavorable genotypes

| Energy balance index* |

0-4 unfavorable genotypes |

5-6 unfavorable genotypes |

≥7 unfavorable genotypes |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case/Control | OR(95%CI)†‡ | P value |

Case/Control | OR(95%CI)†‡ | P value |

Case/Control | OR(95%CI)†‡ | P value |

|

| Q1 | 10/37 | Ref. | 14/15 | 3.56(1.27-10) | 0.016 | 8/18 | 1.98(0.65-5.98) | 0.227 | |

| Q2 | 47/80 | 1.93(0.87-4.3) | 0.108 | 38/66 | 1.96(0.86-4.44) | 0.108 | 40/31 | 5.06(2.15-11.9) | <0.001 |

| Q3 | 86/123 | 2.49(1.16-5.36) | 0.019 | 72/104 | 2.84(1.31-6.16) | 0.008 | 67/54 | 4.85(2.18-10.79) | <0.001 |

| Q4 | 71/82 | 2.83(1.3-6.18) | 0.009 | 83/51 | 5.67(2.56-12.57) | <0.001 | 55/27 | 7.19(3.05-16.91) | <0.001 |

| Q5 | 43/34 | 4.26(1.82-9.98) | 0.001 | 66/21 | 10.59(4.41-25.39) | <0.001 | 36/5 | 21.93(6.7-71.77) | <0.001 |

:Adjusting for age, sex, tobacco smoking, and BMI where appropriate

:Refer to individuals carrying 0-4 unfavorable genotypes and with lowest energy balance index (Q1)

:Energy balance index is calculated by the combination of energy intake and physical activity, Q1:low energy intake+intensive physical activity; Q2: low energy intake+medium physical activity or medium energy intake+intensive physical activity; Q3:low energy intake+low physical activity or medium energy intake+medium physical activity or high energy intake+intensive physical activity; Q4:medium energy intake+low physical activity or high energy intake+medium physical activity; Q5:high energy intake+low physical activity.

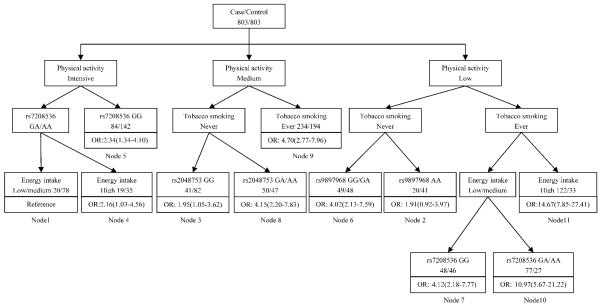

We applied CART analysis to explore the high order gene-gene and gene-environment interactions. As shown in Figure 2, three life style factors (tobacco smoking, physical activity and energy intake) and three SNPs (rs7208536, rs9897968, rs2048753) were identified as the defining variables in the tree model (Figure 2). The final tree structure contained 11 terminal nodes, representing a range of low to high risk subgroups as defined by different gene-gene, gene-environment combinations. The initial split of the root node was physical activity, indicating the importance of energy expenditure in the risk of bladder cancer. To calculate ORs as defined by the terminal nodes, we defined node 1 as the reference group, representing individuals had high physical activity, low/medium energy intake and rs7208536 GA/AA genotype. The ORs of terminal nodes ranged from 1.91 to 14.67 (Table 6). The highest risk group was individuals in terminal node 11 (ever smokers with low physical activity and high energy intake). Compared with the reference group, the risk for bladder cancer in this group has 14.67-fold increase (OR: 14.67; 95% CI= 7.85 to 27.41).

Figure 2.

CART analysis of genetic polymorphisms in mTOR pathway in the risk of bladder cancer

Note: Odds ratios and 95% CIs (in parenthesis) are presented underneath each terminal node box.

Table 6.

CART terminal nodes and risk for bladder cancer

| Node† | Case/Control | Case rate(%) | OR(95% CI)‡ | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Node 1 | 20/78 | 20.41 | 1 | |

| Node 2 | 20/41 | 32.79 | 1.91(0.92-3.97) | 0.082 |

| Node 3 | 41/82 | 33.33 | 1.95(1.05-3.62) | 0.034 |

| Node 4 | 19/35 | 35.19 | 2.16(1.03-4.56) | 0.042 |

| Node 5 | 84/142 | 37.17 | 2.34(1.34-4.10) | 0.003 |

| Node 6 | 49/48 | 50.52 | 4.02(2.13-7.59) | <0.001 |

| Node 7 | 49/46 | 51.58 | 4.12(2.18-7.77) | <0.001 |

| Node 8 | 50/47 | 51.55 | 4.15(2.20-7.83) | <0.001 |

| Node 9 | 234/194 | 54.67 | 4.70(2.77-7.96) | <0.001 |

| Node 10 | 76/27 | 73.79 | 10.97(5.67- 21.22) |

<0.001 |

| Node 11 | 122/33 | 78.71 | 14.67(7.85- 27.41) |

<0.001 |

:Refer to CART analysis (Figure 2)

:Adjusting for age and sex

Discussion

In this large case-control study, we evaluated the association between energy intake, physical activity, obesity, and the risk of bladder cancer. We also assessed whether genetic polymorphisms in mTOR pathway related genes may interact with energy balance to modify bladder cancer risk. We found that both high caloric intake and low physical activity conferred increased risk of bladder cancer and that the risk may be modified by polymorphisms in the mTOR pathway genes. Specifically, the risk associated with high energy intake and low physical activity was most evident among subjects carrying high number of unfavorable genotypes in the mTOR pathway. Moreover, our results strongly suggested that physical activity, energy balance and genetic variants in the mTOR pathway jointly influenced the risk: subjects located in the worst energy balance category (high energy intake, low physical activity, and carrying seven or more unfavorable genotype) were at more than ten fold increased risk as compared to subjects within the most favorable energy balance category (low energy intake, intensive physical activity, low number of unfavorable genotypes). This is the first study to report joint effects of energy balance and the genetic modification effects from the mTOR pathway genes in bladder cancer.

In the current study, we observed an increased bladder cancer risk with high daily energy intake. Few data on associations between energy intake and bladder cancer risk are noted, except that a null association was reported in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (20). However, our result is consistent to the findings from other cancer sites including kidney (49), breast (50) and rectum (51). In a large population-based case-control study (49), high calorie intake was associated with significantly 1.30-fold increased risk of renal cancer. In a large prospective study of more than 38,000 women (50), a significantly increased 1.25-fold increased risk of breast cancer was reported with increasing energy intake. Our results further revealed that the increased risk of high energy intake was only observed in smokers and that there was a significant interaction between energy intake and smoking status.

Energy balance reflects the interplay between diet, physical activity, as well as genetic background (37, 52). Positive energy balance due to excessive caloric intake and/or decreased energy expenditure leads obesity and consequently elevated levels of bioactive IGF-1, insulin adipokines and pro-inflammatory cytokines, which promote carcinogenesis process (37). Animal studies suggest that restricting energy intake delays disease onset, including cancer (53, 54) and increases life expectancy (55). Energy restriction affects adrenal and insulin metabolism, as well as various gene expression (56). Restriction of calories intake by 10%-40% has been shown to decrease cell proliferation, increasing apoptosis through anti-angiogenesis processes (4).

Although the potential anticancer effect of calorie restriction is clear, it is not generally considered to be a independent feasible strategy for cancer prevention in humans because even moderate calorie restriction may be harmful in specific patient populations, such as lean persons who have minimal amounts of body fat (4). Thus, physical activity, which helps increase energy expenditure, is considered as an alternative way to maintain energy balance. Compelling evidence has suggested that physical activity may enhance carcinogen detoxification, promote DNA repair process; alter cell proliferation, apoptosis and differentiation; decrease inflammation and enhance immune function (57). Consistent with the above anti-cancer roles of physical activity, we observed a strong inverse association between physical activity and bladder cancer risk and that the association was not modified by smoking status. In literature, few studies specifically examined the relation between physical activity and bladder cancer and the results were generally negative (14, 15, 20). In a large prospective cohort study of U.S. men and women (14), intensive physical activity showed a borderline significant inverse association with bladder cancer with a RR of 0.87 (95% CI=0.74-1.02) and the association was observed in former smokers only. In another large cohort study using data collected in the Health Professionals’ Follow-up Study and the Nurses’ Health Study (20), total recreational physical activity was not associated with bladder cancer with a RR of 0.97 (95% CI=0.77-1.24). Lack of an association was also observed in some early studies with small number of bladder cancer cases (16-18, 58). However, in the Iowa Women’s Health Study of postmenopausal women (15), an inverse association between regular physical activity and bladder cancer was borderline significant (RR=0.66; 95% CI=0.43-1.01). In contrast, an increased risk (RR=2.06, 95% CI=1.08-3.95) in bladder cancer was reported in a prospective study performed in middle aged men in England (13). Physical activity is a complex behavior and the quantification of physical activity is complicated because it involves not only measures of frequency, intensity and duration, but also multiple categories of physical activity (leisure time, occupation, household, transportation, etc.). Thus, physical activity is not precisely measured in most epidemiologic studies. Other possible explanations to the inconsistent results include the different study design, lack of control for confounding or chance findings due to small sample size in some studies.

One limitation of the above-mentioned studies is that genetic factors are not considered in risk assessment. In light of genetic predisposition to energy balance and cancer risk and because the mTOR pathway is a pathway directly engaged in energy balance, we stratified the analysis of energy balance by genetic variants in the mTOR pathway to further elucidate the association between energy balance and bladder cancer. Interestingly, we found that the risk associated with high energy intake and low physical activity was only evident among subjects carrying high number of unfavorable genotypes in the mTOR pathway.

Energy balance could modulate cellular signaling through cell-surface receptors, affecting activation or deactivation of multiple downstream genes within the mTOR pathway. The PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling pathway has been shown to be commonly activated in cancers (59). The signal is initiated by growth factors, nutrients, mutagens and hormones that bind receptor tyrosine kinases, which then activate PI3Ks, resulting in a kinase cascade through AKT and mTOR, generating cell survival, growth, differentiation, cell cycle control, and angiogenesis signals (60), molecular processes that implicated in cancers (39). As energy balance could affect activation or deactivation of multiple downstream genes within the mTOR pathway and that the full activation of the mTOR pathway requires signals from both nutrients and growth factors, it is important to evaluate the role of mTOR pathway genes and cancer risk in the context of energy balance status (61). Although the mTOR pathway has been implicated in energy balance regulation, current evidence regarding the interaction between mTOR pathway and energy balance in cancer risk from epidemiologic studies are scarce. To our knowledge, our current study is the first to explore the joint effects of genetic polymorphisms in the mTOR pathway and energy balance in bladder cancer risk. One important observation is that increased risk of bladder cancer associated with high energy intake and low physical activity was only observed in subjects carrying high number of adverse genotypes, supporting strong modification effects from genetic factor in energy balance-bladder cancer association. Moreover, when physical activity, energy intake and genetic variants were analyzed jointly, the study population was clearly stratified into a range of low to high risk subgroups with subjects located in the worst energy balance category (high energy intake, low physical activity, and carrying ten or more unfavorable genotype) experiencing the highest risk of bladder cancer. Our results strongly support joint effects of physical activity, energy balance and genetic variants in the mTOR pathway in bladder cancer susceptibility.

In our current study, we observed no association between obesity and bladder cancer in overall analysis and in stratified analysis by smoking status. The association between BMI and bladder cancer has been inconsistent in literature. The majority of prospective cohort studies reported modest positive association (14, 20, 22-27). Some of these associations reached statistical significance while others did not. In the Health Professionals Follow-up study (20) no association between baseline BMI and bladder cancer was observed. However, a significant positive association was found (RR=1.33, 95% CI=1.01-1.76) after excluding cases diagnosed within first 4 years of follow-up. A recent cohort study, the IH-AARP Diet and Health Study (14), found an up to 28% increased risk of bladder cancer associated with obesity with significant dose response trend. In contrast, two other cohort studies reported nonsignificant inverse association between BMI and bladder cancer (15, 29). The reason for the inverse association is unknown and possibly due to residual confounding from smoking that had not been removed. Compared to cohort studies, the results from case-control studies are more divergent with reporting positive association, inverse association or null association (31-34). The change in weight due to cancer diagnosis in cases could bias the results in case-control studies. The reference periods from which BMI were calculated is not consistent in previous studies and some studies did not report the reference period. Compared to prospective cohort studies, the bias in BMI due to the retrospective design may have led to the more inconsistent results in case-control studies. The association between obesity and bladder cancer warrant further study. Moreover, the inconsistencies could be attributed genetic risk factors yet to be identified.

We further explored the association between BMI and bladder cancer using weight 5 years prior to cancer diagnosis, weight 1 year ago prior to cancer diagnosis and current weight at cancer diagnosis. Inverse associations were found in all three scenarios. However, the magnitude of the association was different. The OR for the obese subjects was 0.79 (0.59-1.07) if BMI 5 years ago was used. The ORs for BMI 1 year ago and current BMI were 0.74 (0.55-0.99), 0.63 (0.47-0.85), respectively. We believe that the significant inverse association with current weight might largely be a result of weight loss due to bladder cancer diagnosis. To minimize such bias, we chose to use weight 5 years prior to cancer diagnosis to calculate BMI. Because data based on recall of diet and physical activity 5 years ago may not accurate, in our study, we only collected physical activity data and dietary intake data in reference to 1 year before cancer diagnosis. Taken together, although not ideal, considering of biases commonly found in case-control studies, the use of weight 5 years ago and calorie intake and physical activity one year ago may be a reasonable choice in this study.

Our data suggest that the high calorie intake and low physical activity of bladder cancer cases did not result in high BMI. The reason is unknown. But it should be noted that energy balance is maintained by a complex system involving multiple interactive pathways and that the three simple variables (calorie intake, physical activity, BMI) are not sufficient to describe the overall energy balance status. Other dietary factors, energy expenditure variables, and/or genetic factors not measured in this study may have contributed to the discrepancy and warrant further investigation.

In this study, besides the traditional logistic regression model, we also adopted a nonparametric CART analysis, to explore the potential gene-gene and gene-environment interactions. The terminal nodes as defined by combination of specific SNPs and life-style factors reflect risk subgroups resulted from the interactions between genetic and environmental factors. The grouping of specific genotypes in the nodes of CART analysis may not be consistent with the results from single SNP analysis by using logistical regression model, which did not take account of the high-order interactions between variables. The complementary application of both techniques has been proved to be a promising approach to perform the task of analyzing and interpreting the results of multiple marker studies.

Several methodological issues should be discussed. One limitation in case-control studies is recall bias, in which healthy controls are more likely to recall “healthy life style” than cancer patients (e.g., frequent physical activity, healthy diet pattern with less fat intake, etc.) leading to biased estimates of relative risk. Although the analyses presented have well controlled for confounders including age, sex and tobacco smoking, other bladder cancer risk factors may have confounded the observed associations. Moreover, the case-control study design may subject to selection bias, in which the energy intake and physical activity of participants and non-participants may differ. Thus, prospective cohort studies are needed to better unveil the causal relationship between physical activity, energy intake and cancer.

In conclusion, this is the first study to investigate joint effects of genetic variants in the mTOR pathway and energy balance in the susceptibility of bladder cancer. Our results strongly support that both high caloric intake and low physical activity conferred increased bladder cancer risk and that the risk may be modified by genetic polymorphisms of mTOR pathway related genes. The joint effects of physical activity, energy intake and genetic variants in the mTOR pathway strongly suggest that bladder cancer susceptibility could be modified by energy balance status as defined by energy intake, physical activity and genetic variants in the mTOR pathway genes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by NCI grants CA 74880 and CA 91846

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Competing interests The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu X, Ros MM, Gu J, Kiemeney L. Epidemiology and genetic susceptibility to bladder cancer. BJU Int. 2008;102:1207–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slattery ML, Murtaugh M, Caan B, Ma KN, Neuhausen S, Samowitz W. Energy balance, insulin-related genes and risk of colon and rectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2005;115:148–54. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fair AM, Montgomery K. Energy balance, physical activity, and cancer risk. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;472:57–88. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-492-0_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flegal KM, Graubard BI, Williamson DF, Gail MH. Excess deaths associated with underweight, overweight, and obesity. JAMA. 2005;293:1861–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.15.1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Renehan AG, Tyson M, Egger M, Heller RF, Zwahlen M. Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Lancet. 2008;371:569–78. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60269-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moghaddam AA, Woodward M, Huxley R. Obesity and risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of 31 studies with 70,000 events. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:2533–47. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas CC, Wingo PA, Dolan MS, Lee NC, Richardson LC. Endometrial Cancer Risk Among Younger, Overweight Women. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:22–27. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181ab6784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pan SY, DesMeules M. Energy intake, physical activity, energy balance, and cancer: epidemiologic evidence. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;472:191–215. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-492-0_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolin KY, Yan Y, Colditz GA, Lee IM. Physical activity and colon cancer prevention: a meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:611–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Voskuil DW, Monninkhof EM, Elias SG, Vlems FA, van Leeuwen FE. Physical activity and endometrial cancer risk, a systematic review of current evidence. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:639–48. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monninkhof EM, Elias SG, Vlems FA, van der Tweel I, Schuit AJ, Voskuil DW, van Leeuwen FE. Physical activity and breast cancer: a systematic review. Epidemiology. 2007;18:137–57. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000251167.75581.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG, Walker M. Physical activity and risk of cancer in middle-aged men. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:1311–6. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koebnick C, Michaud D, Moore SC, Park Y, Hollenbeck A, Ballard-Barbash R, Schatzkin A, Leitzmann MF. Body mass index, physical activity, and bladder cancer in a large prospective study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:1214–21. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tripathi A, Folsom AR, Anderson KE. Risk factors for urinary bladder carcinoma in postmenopausal women. The Iowa Women’s Health Study. Cancer. 2002;95:2316–23. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dosemeci M, Hayes RB, Vetter R, Hoover RN, Tucker M, Engin K, Unsal M, Blair A. Occupational physical activity, socioeconomic status, and risks of 15 cancer sites in Turkey. Cancer Causes Control. 1993;4:313–21. doi: 10.1007/BF00051333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paffenbarger RS, Jr., Hyde RT, Wing AL. Physical activity and incidence of cancer in diverse populations: a preliminary report. Am J Clin Nutr. 1987;45:312–7. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/45.1.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Severson RK, Nomura AM, Grove JS, Stemmermann GN. A prospective analysis of physical activity and cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;130:522–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schnohr P, Gronbaek M, Petersen L, Hein HO, Sorensen TI. Physical activity in leisure-time and risk of cancer: 14-year follow-up of 28,000 Danish men and women. Scand J Public Health. 2005;33:244–9. doi: 10.1080/14034940510005752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holick CN, Giovannucci EL, Stampfer MJ, Michaud DS. Prospective study of body mass index, height, physical activity and incidence of bladder cancer in US men and women. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:140–6. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Machova L, Cizek L, Horakova D, Koutna J, Lorenc J, Janoutova G, Janout V. Association between obesity and cancer incidence in the population of the District Sumperk, Czech Republic. Onkologie. 2007;30:538–42. doi: 10.1159/000108284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolk A, Gridley G, Svensson M, Nyren O, McLaughlin JK, Fraumeni JF, Adam HO. A prospective study of obesity and cancer risk (Sweden) Cancer Causes Control. 2001;12:13–21. doi: 10.1023/a:1008995217664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Samanic C, Gridley G, Chow WH, Lubin J, Hoover RN, Fraumeni JF., Jr. Obesity and cancer risk among white and black United States veterans. Cancer Causes Control. 2004;15:35–43. doi: 10.1023/B:CACO.0000016573.79453.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moller H, Mellemgaard A, Lindvig K, Olsen JH. Obesity and cancer risk: a Danish record-linkage study. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30A:344–50. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)90254-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whittemore AS, Paffenbarger RS, Jr., Anderson K, Lee JE. Early precursors of urogenital cancers in former college men. J Urol. 1984;132:1256–61. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)50118-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Batty GD, Shipley MJ, Jarrett RJ, Breeze E, Marmot MG, Smith GD. Obesity and overweight in relation to organ-specific cancer mortality in London (UK): findings from the original Whitehall study. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29:1267–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1625–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lew EA, Garfinkel L. Variations in mortality by weight among 750,000 men and women. J Chronic Dis. 1979;32:563–76. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(79)90119-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rapp K, Schroeder J, Klenk J, Stoehr S, Ulmer H, Concin H, Diem G, Oberaigner W, Weiland SK. Obesity and incidence of cancer: a large cohort study of over 145,000 adults in Austria. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:1062–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cantwell MM, Lacey JV, Jr., Schairer C, Schatzkin A, Michaud DS. Reproductive factors, exogenous hormone use and bladder cancer risk in a prospective study. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:2398–401. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pan SY, Johnson KC, Ugnat AM, Wen SW, Mao Y. Association of obesity and cancer risk in Canada. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:259–68. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pelucchi C, La Vecchia C, Negri E, Dal Maso L, Franceschi S. Smoking and other risk factors for bladder cancer in women. Prev Med. 2002;35:114–20. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harris RE, Chen-Backlund JY, Wynder EL. Cancer of the urinary bladder in blacks and whites. A case-control study. Cancer. 1990;66:2673–80. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19901215)66:12<2673::aid-cncr2820661235>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vena JE, Graham S, Freudenheim J, Marshall J, Zielezny M, Swanson M, Sufrin G. Diet in the epidemiology of bladder cancer in western New York. Nutr Cancer. 1992;18:255–64. doi: 10.1080/01635589209514226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu X, Lin X, Dinney CP, Gu J, Grossman HB. Genetic polymorphism in bladder cancer. Front Biosci. 2007;12:192–213. doi: 10.2741/2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones RG, Thompson CB. Tumor suppressors and cell metabolism: a recipe for cancer growth. Genes Dev. 2009;23:537–48. doi: 10.1101/gad.1756509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hursting SD, Lashinger LM, Wheatley KW, Rogers CJ, Colbert LH, Nunez NP, Perkins SN. Reducing the weight of cancer: mechanistic targets for breaking the obesity-carcinogenesis link. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;22:659–69. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moore T, Beltran L, Carbajal S, Strom S, Traag J, Hursting SD, DiGiovanni J. Dietary energy balance modulates signaling through the Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin pathways in multiple epithelial tissues. Cancer Prev Res (Phila Pa) 2008;1:65–76. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strimpakos AS, Karapanagiotou EM, Saif MW, Syrigos KN. The role of mTOR in the management of solid tumors: an overview. Cancer Treat Rev. 2009;35:148–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosner M, Hanneder M, Siegel N, Valli A, Fuchs C, Hengstschlager M. The mTOR pathway and its role in human genetic diseases. Mutat Res. 2008;659:284–92. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin J, Kamat A, Gu J, Chen M, Dinney CP, Forman MR, Wu X. Dietary intake of vegetables and fruits and the modification effects of GSTM1 and NAT2 genotypes on bladder cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2090–7. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Block G, Thompson FE, Hartman AM, Larkin FA, Guire KE. Comparison of two dietary questionnaires validated against multiple dietary records collected during a 1-year period. J Am Diet Assoc. 1992;92:686–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Leon AS, Jacobs DR, Jr., Montoye HJ, Sallis JF, Paffenbarger RS., Jr. Compendium of physical activities: classification of energy costs of human physical activities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1993;25:71–80. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199301000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, Irwin ML, Swartz AM, Strath SJ, O’Brien WL, Bassett DR, Jr., Schmitz KH, Emplaincourt PO, Jacobs DR, Jr., Leon AS. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32:S498–504. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen M, Cassidy A, Gu J, Delclos GL, Zhen F, Yang H, Hildebrandt MA, Lin J, Ye Y, Chamberlain RM, Dinney CP, Wu X. Genetic variations in PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway and bladder cancer risk. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:2047–52. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu X, Ye Y, Kiemeney LA, Sulem P, Rafnar T, Matullo G, Seminara D, Yoshida T, Saeki N, Andrew AS, Dinney CP, Czerniak B, Zhang ZF, Kiltie AE, Bishop DT, Vineis P, Porru S, Buntinx F, Kellen E, Zeegers MP, Kumar R, Rudnai P, Gurzau E, Koppova K, Mayordomo JI, Sanchez M, Saez B, Lindblom A, de Verdier P, Steineck G, Mills GB, Schned A, Guarrera S, Polidoro S, Chang SC, Lin J, Chang DW, Hale KS, Majewski T, Grossman HB, Thorlacius S, Thorsteinsdottir U, Aben KK, Witjes JA, Stefansson K, Amos CI, Karagas MR, Gu J. Genetic variation in the prostate stem cell antigen gene PSCA confers susceptibility to urinary bladder cancer. Nat Genet. 2009;41:991–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim KI, van de Wiel MA. Effects of dependence in high-dimensional multiple testing problems. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:114. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Storey JD, Tibshirani R. Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9440–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1530509100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pan SY, DesMeules M, Morrison H, Wen SW. Obesity, high energy intake, lack of physical activity, and the risk of kidney cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:2453–60. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chang SC, Ziegler RG, Dunn B, Stolzenberg-Solomon R, Lacey JV, Jr., Huang WY, Schatzkin A, Reding D, Hoover RN, Hartge P, Leitzmann MF. Association of energy intake and energy balance with postmenopausal breast cancer in the prostate, lung, colorectal, and ovarian cancer screening trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:334–41. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mao Y, Pan S, Wen SW, Johnson KC. Physical inactivity, energy intake, obesity and the risk of rectal cancer in Canada. Int J Cancer. 2003;105:831–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hursting SD, Lashinger LM, Colbert LH, Rogers CJ, Wheatley KW, Nunez NP, Mahabir S, Barrett JC, Forman MR, Perkins SN. Energy balance and carcinogenesis: underlying pathways and targets for intervention. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2007;7:484–91. doi: 10.2174/156800907781386623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Colman RJ, Anderson RM, Johnson SC, Kastman EK, Kosmatka KJ, Beasley TM, Allison DB, Cruzen C, Simmons HA, Kemnitz JW, Weindruch R. Caloric restriction delays disease onset and mortality in rhesus monkeys. Science. 2009;325:201–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1173635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Speakman JR, Hambly C. Starving for life: what animal studies can and cannot tell us about the use of caloric restriction to prolong human lifespan. J Nutr. 2007;137:1078–86. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.4.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fontana L, Klein S. Aging, adiposity, and calorie restriction. JAMA. 2007;297:986–94. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.9.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kritchevsky D. Caloric restriction and experimental carcinogenesis. Hybrid Hybridomics. 2002;21:147–51. doi: 10.1089/153685902317401753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rogers CJ, Colbert LH, Greiner JW, Perkins SN, Hursting SD. Physical activity and cancer prevention : pathways and targets for intervention. Sports Med. 2008;38:271–96. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200838040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brownson RC, Chang JC, Davis JR, Smith CA. Physical activity on the job and cancer in Missouri. Am J Public Health. 1991;81:639–42. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.5.639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jiang BH, Liu LZ. PI3K/PTEN signaling in angiogenesis and tumorigenesis. Adv Cancer Res. 2009;102:19–65. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(09)02002-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Manning BD, Cantley LC. AKT/PKB signaling: navigating downstream. Cell. 2007;129:1261–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Manning BD. Balancing Akt with S6K: implications for both metabolic diseases and tumorigenesis. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:399–403. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200408161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.