The role of the p53 protein in preventing tumor progression has been largely attributed to its ability to induce apoptosis or senescence in cells undergoing malignant progression (1). The transformation of cells from normal to cancerous is accompanied by increases in numerous types of stress that signal to the activation of p53, which can then provoke the elimination of the rogue cell. This executioner role for p53 neatly accommodates its role as a tumor suppressor—and it is certainly the response to p53 that we would like to reactivate for the treatment of cancer. However, there is now growing evidence that under certain circumstances, p53 can also come to the aid of a stressed cell, functioning to protect the cell from damage and contributing to a survival response (2). Several of the more recently described roles of p53 in regulating metabolism seem to fall into this latter category, suggesting that p53 helps to maintain normal metabolism and plays a key role in allowing cells to adapt to various types of metabolic stress. Two interesting new studies published in this issue of PNAS take this area of p53 activity even further, describing a role for p53 in the metabolism of glutamine through the activation of expression of glutaminase 2 (GLS2) (3, 4). These observations immediately suggest a plethora of intriguing possibilities and further questions.

p53 is a key player in the response to a multitude of different types of stress. First shown to be activated by DNA damage, we now know that p53 can be induced by a broad gamut of signals, including telomere shortening, hypoxia, loss of cell contact, oncogene activation, and starvation. It seems that whenever the cell gets into trouble, p53 is called upon to help deal with the problem. Interestingly, the range of possible outcomes upon p53 activation is also extremely diverse and includes the ability to control the pathways of energy metabolism and modulate oxidative stress (5). Most intriguingly, several of these functions of p53 have been found to operate even in the absence of overt stress signals, suggesting that p53 may play a role under normal growth conditions, as well as in response to trauma.

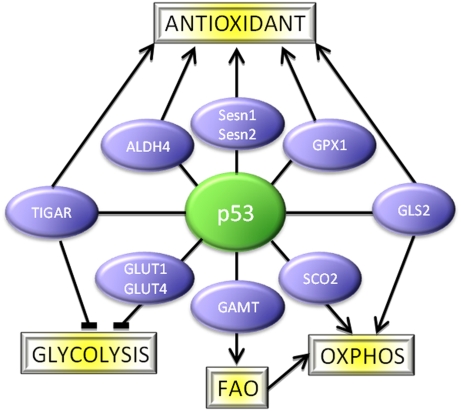

Changes in the mechanisms of energy metabolism are deeply embedded in the switch from normal to malignant growth. Most cancer cells show alterations in glucose metabolism that result in the utilization of glycolysis—rather than oxidative phosphorylation—for energy production. Mounting evidence supports the importance of these alterations to the maintenance of tumorigenesis (6), with the possibility that tumor cells become selectively dependent on these changes. Several p53 activities can oppose this metabolic switch, by both dampening the rate of glycolysis (through repressing the expression genes like GLUT1, GLUT4, or PGM that function to drive glycolysis, or activating the expression of genes like TIGAR that slow glycolysis) and by promoting mitochondrial respiration (through the activation of genes like SCO2) and mitochondrial maintenance (7) (Fig. 1). p53 therefore plays an important role in maintaining the balance between glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation, providing a mechanism by which p53 can hinder cancer development that is clearly different from the induction of cell death or senescence.

Fig. 1.

p53 at the hub of a network of pathways that regulate metabolism and oxidative stress. Many p53-inducible proteins that function in these responses have now been described; for clarity, only some examples have been shown here.

A second important function of p53 in preventing oncogenic transformation (as opposed to eliminating cells that may have acquired oncogenic changes) is to limit oxidative damage (8). p53 can directly activate the expression of antioxidant genes such as the sestrins, SOD2, GPX1, and ALDH4 (Fig. 1). The induction of TIGAR by p53, while dampening glycolysis, promotes the use of the pentose phosphate pathway and so encourages the production of NADPH that is essential for antioxidant activity. This activity of p53 helps to prevent the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced DNA damage, thereby suppressing tumor progression. Intriguingly, this function of p53 may also contribute to other, non–cancer-associated pathologies, such as aging.

The two articles describing the activation of GLS2 by p53 give us a further nugget of information to integrate into our understanding of p53 function (Fig. 1). GLS2 converts glutamine to glutamate, which can be used to generate Krebs cycle intermediates and reduced glutathione (GSH), which functions as a key ROS scavenger in the cell. The studies show that the induction of GLS2 by p53 leads to an efficient antioxidant activity, reflected in an increased ratio between GSH and oxidized glutathione. Loss of p53, or depletion of GLS2, enhanced intracellular ROS and increased the cell's sensitivity to ROS-associated apoptosis. Importantly, GLS2 was linked to tumorigenesis, with loss of GLS2 expression detected in hepatocellular carcinomas and overexpression of GLS2 (in experimental systems) resulting in a decrease of tumor cell growth. Taken together, the data nicely support a role for p53-mediated activation of GLS2 in lowering ROS and protecting from tumor development. Importantly, as has been shown for many other antioxidant activities of p53, the regulation of GLS2 by p53 occurs in cells even in the absence of acute stress, supporting the importance of the antioxidant activities of p53 under normal growth conditions.

There are, however, more consequences of GLS2 expression than the generation of GSH. The glutamate produced by GLS2 can be converted to form α-ketoglutarate, which is a Krebs cycle intermediate. p53 is known to promote mitochondrial respiration through the activation of several genes, such as SCO2 (9), and the new studies show that GLS2 activity also increases ATP production and oxygen consumption. This role of p53 in respiration may help to explain why so many cancers (in which the p53 function is generally compromised) show a dependence on glycolysis for energy production (7). But in the case of glutaminolysis, aligning this previously uncharacterized function of p53 with the emerging concepts of how metabolic changes contribute to cancer is likely to require some more investigation. As is seen for glucose utilization, glutamine uptake and metabolism can also be altered during the cancer development to result in enhanced rates of glutaminolysis. Indeed Myc, an oncogene that plays an important role in most human cancers, has been shown to promote glutaminolysis through the induction of expression of glutaminase 1 (GLS1) (10, 11), an enzyme with a structure and activity similar to that of GLS2. Under these conditions, Myc-induced glutaminolysis contributes to the proliferation and survival of the transformed cells. An emerging model suggests that increased glutamine metabolism in cancers would help boost energy production (when sufficient oxygen is available) and lower ROS, but may be most important in providing Krebs cycle intermediates for the anabolic reactions that generate nonessential amino acids, lipids, and nucleotides to support cell growth (12). At first glance, Myc-driven glutaminolysis contributing to tumorigenesis might seem to be quite inconsistent with a similar role of p53 in tumor suppression. Although the answer to this riddle is not completely clear, there are several clues that point to a possible solution. Clearly, GLS1 and GLS2 are regulated differently—the oncogene Myc targets only GLS1, whereas the tumor suppressor p53 only controls the expression of GLS2. Although sharing some functions, GLS1 and GLS2 show distinct kinetics and activities that may make the consequences of their enhanced expression quite different, and this may depend on factors that include signal, environment, and cell/tissue type. But even if GLS1 and GLS2 expression has essentially the same consequences, this will not be the first example whereby p53 regulates an activity that has the potential to both prevent and contribute to tumor development,depending on the circumstances.

p53 may play a role under normal growth conditions, as well as in response to trauma.

Consider, for example, the contribution of p53 to ROS regulation, whereby diametrically opposite activities can be elicited. The antioxidant activities of p53, to which GLS2 clearly contributes, have been convincingly shown to help prevent tumor development (13). However, several apoptotic target genes of p53 can promote the accumulation of oxidative stress, and the apoptotic/senescence responses induced by p53 are dependent, to a large degree, on ROS (14). So under these conditions, antioxidants that lower ROS levels would reduce apoptosis or senescence and could hinder p53’s tumor-suppressive abilities. There is clearly a complex interplay between the different responses to p53 and how these activities are regulated. It does not seem beyond the bounds of possibility to suggest that in some tissue types, enhanced expression of a protein that can lower ROS and promote glutaminolysis, like GLS2, might contribute to tumorigenesis.

It might also be interesting to consider this previously uncharacterized activity of p53 in allowing cells to adapt to changes in nutrient availability. p53 is emerging as central in coordinating the response to metabolic or energetic stress, driving outcomes such as cell cycle arrest and autophagy that help cells adapt and survive (15). Activation of guanidinoacetate methyltransferase (GAMT) by p53 can enhance fatty acid oxidation, providing an energy source that might help cells ride out periods of starvation (16) (Fig. 1). Similarly, the ability of p53 to promote the utilization of glutamine for energy production could also, under some conditions, help buffer cells from fluctuations in the availability or range of nutrient sources.

Most exciting, perhaps, is the impact that understanding the metabolic functions of p53 has on our ability to indentify critical points in these pathways to serve as targets for therapeutic intervention. The metabolic alterations caused by loss of p53 seem to contribute to cancer progression but also present some interesting points of vulnerability that may be specific to the cancer cell (17). The apparently opposing functions of GLS1 and GLS2 in regulating cancer development might even suggest that it would be worth searching for specific inhibitors of one but not the other. Even more intriguing is the emerging suggestion that p53 contributes to metabolic disorders such as diabetes and aging (18). Identifying, understanding, and exploiting these could be key in our search for new ways to treat disease.

Acknowledgments

K.H.V. is supported by funding from Cancer Research UK.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Zuckerman V, Wolyniec K, Sionov RV, Haupt S, Haupt Y. Tumour suppression by p53: the importance of apoptosis and cellular senescence. J Pathol. 2009;219:3–15. doi: 10.1002/path.2584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vousden KH, Prives C. Blinded by the light: The growing complexity of p53. Cell. 2009;137:413–431. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu A, et al. Glutaminase 2, a novel p53 target gene regulating energy metabolism and antioxidant function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:7455–7460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001006107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suzuki S, et al. Phosphate activated glutaminase (GLS2), a p53-inducible regulator of glutamine metabolism and reactive oxygen species. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:7461–7466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002459107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gottlieb E, Vousden KH. p53 regulation of metabolic pathways. Cold Spring Harbor Pespect Biol. 2010 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001040. 10.1101/cshperspec.a001040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tennant DA, Durán RV, Boulahbel H, Gottlieb E. Metabolic transformation in cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:1269–1280. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeung SJ, Pan J, Lee MH. Roles of p53, MYC and HIF-1 in regulating glycolysis—the seventh hallmark of cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:3981–3999. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8224-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olovnikov IA, Kravchenko JE, Chumakov PM. Homeostatic functions of the p53 tumor suppressor: Regulation of energy metabolism and antioxidant defense. Semin Cancer Biol. 2009;19:32–41. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matoba S, et al. p53 regulates mitochondrial respiration. Science. 2006;312:1650–1653. doi: 10.1126/science.1126863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wise DR, et al. Myc regulates a transcriptional program that stimulates mitochondrial glutaminolysis and leads to glutamine addiction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:18782–18787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810199105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao P, et al. c-Myc suppression of miR-23a/b enhances mitochondrial glutaminase expression and glutamine metabolism. Nature. 2009;458:762–765. doi: 10.1038/nature07823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deberardinis RJ, Sayed N, Ditsworth D, Thompson CB. Brick by brick: Metabolism and tumor cell growth. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2008;18:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sablina AA, et al. The antioxidant function of the p53 tumor suppressor. Nat Med. 2005;11:1306–1313. doi: 10.1038/nm1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Macip S, et al. Influence of induced reactive oxygen species in p53-mediated cell fate decisions. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:8576–8585. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.23.8576-8585.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng Z. p53 Regulation of the IGF-1/AKT/mTOR pathways and the endosomal compartment. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a001057. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ide T, et al. GAMT, a p53-inducible modulator of apoptosis, is critical for the adaptive response to nutrient stress. Mol Cell. 2009;36:379–392. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 17.Buzzai M, et al. Systemic treatment with the antidiabetic drug metformin selectively impairs p53-deficient tumor cell growth. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6745–6752. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bazuine M, Stenkula KG, Cam M, Arroyo M, Cushman SW. Guardian of corpulence: A hypothesis on p53 signaling in the fat cell. Clin Lipidol. 2009;4:231–243. doi: 10.2217/clp.09.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]