Abstract

As the terminal step in photosystem II, and a potential half-reaction for artificial photosynthesis, water oxidation (2H2O → O2 + 4e- + 4H+) is key, but it imposes a significant mechanistic challenge with requirements for both 4e-/4H+ loss and O—O bond formation. Significant progress in water oxidation catalysis has been achieved recently by use of single-site Ru metal complex catalysts such as [Ru(Mebimpy)(bpy)(OH2)]2+ [Mebimpy = 2,6-bis(1-methylbenzimidazol-2-yl)pyridine; bpy = 2,2′-bipyridine]. When oxidized from  to RuV = O3+, these complexes undergo O—O bond formation by O-atom attack on a H2O molecule, which is often the rate-limiting step. Microscopic details of O—O bond formation have been explored by quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical (QM/MM) simulations the results of which provide detailed insight into mechanism and a strategy for enhancing catalytic rates. It utilizes added bases as proton acceptors and concerted atom–proton transfer (APT) with O-atom transfer to the O atom of a water molecule in concert with proton transfer to the base (B). Base catalyzed APT reactivity in water oxidation is observed both in solution and on the surfaces of oxide electrodes derivatized by attached phosphonated metal complex catalysts. These results have important implications for catalytic, electrocatalytic, and photoelectrocatalytic water oxidation.

to RuV = O3+, these complexes undergo O—O bond formation by O-atom attack on a H2O molecule, which is often the rate-limiting step. Microscopic details of O—O bond formation have been explored by quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical (QM/MM) simulations the results of which provide detailed insight into mechanism and a strategy for enhancing catalytic rates. It utilizes added bases as proton acceptors and concerted atom–proton transfer (APT) with O-atom transfer to the O atom of a water molecule in concert with proton transfer to the base (B). Base catalyzed APT reactivity in water oxidation is observed both in solution and on the surfaces of oxide electrodes derivatized by attached phosphonated metal complex catalysts. These results have important implications for catalytic, electrocatalytic, and photoelectrocatalytic water oxidation.

Keywords: water split, O—O coupling, base effect, isotope effect

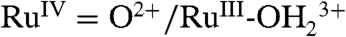

In natural photosynthesis, and in many schemes for artificial photosynthesis, water oxidation (2H2O → O2 + 4e- + 4H+) is a key reaction with requirements for both 4e-/4H+ loss and O—O bond formation. Significant progress in water oxidation catalysis has been achieved recently by using single-site molecular catalysts (1–8). This includes elucidation of a mechanism in Ce(IV) catalyzed water oxidation by [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(OH2)]2+ and [Ru(tpy)(bpz)(OH2)]2+ (tpy = 2,2′∶6′,2′′-terpyridine; bpm = 2,2′-bipyrimidine; bpz = 2,2′-bipyrazine), Scheme 1 (1). Although undergoing multiple turnovers unchanged, these catalysts are relatively slow with O—O bond formation, often the rate-limiting step. In Scheme 1, O-atom transfer from [RuV(tpy)(bpm)(O)]3+ to H2O is rate limiting and occurs with k(0.1 M HNO3,25 °C) = 8.9 × 10-3 s-1 (5). To put rate into perspective, in a practical solar energy conversion scheme, a turnover rate on the millisecond or submillisecond time scale is required to match or exceed the rate of solar insolation. Achieving rates of this magnitude poses a considerable challenge (9).

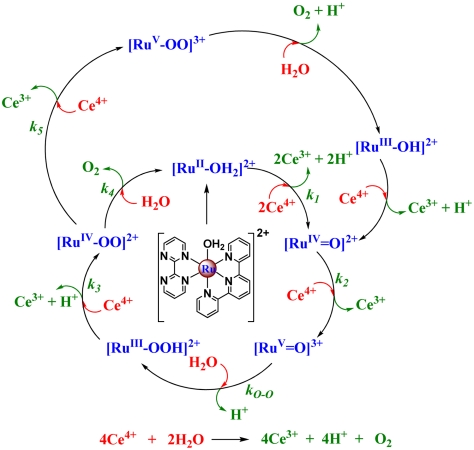

Scheme 1.

Mechanism of Ce(IV) catalyzed water oxidation by the single-site catalyst [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(OH2)]2+ (1, 5). (Reprinted from ref. 5.)

A useful strategy for achieving faster rates in metal complex catalysts exists based on an interplay between mechanism and systematic synthetic modifications. Ligand variations can be used to modify redox potentials, increase driving force, and decrease barriers (6). Mechanistic insight can uncover previously undescribed reaction pathways. We report here the use of a previously unidentified pathway to achieve greatly enhanced rates of electrocatalytic water oxidation for the catalyst, [Ru(Mebimpy)(bpy)(OH2)]2+ (1) [Mebimpy = 2,6-bis(1-methylbenzimidazol-2-yl)pyridine; bpy = 2,2′-bipyridine], Fig. 1A, in solution and for the related phosphonate derivative, {Ru(Mebimpy)[4,4′-((HO)2OPCH2)2bpy](OH2)}2+ (1-PO3H2), on oxide electrode surfaces, Fig. 1B. Significant rate accelerations are observed with added proton acceptor bases. The results of mechanistic and theoretical studies reveal that addition of bases accelerates O—O bond formation by concerted atom–proton transfer (APT) with the added base acting as a proton acceptor decreasing the barrier in the key O—O bond-forming step.

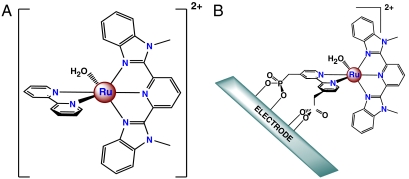

Fig. 1.

Structure of 1 (A) and schematic representation of 1-PO3H2 attached to a metal oxide electrode (B). (Reprinted from ref. 7.)

Results

Electrocatalyzed Water Oxidation.

Complex 1 has been shown to be both a catalyst for water oxidation by Ce(IV) and an electrocatalyst (6, 7). Scan rate normalized cyclic voltammograms (CV, i/υ1/2 vs. potential with i the current density in mA/cm2 and υ the scan rate in mV/s) of 1 in 0.1 M HNO3 at a glassy carbon (GC) electrode at different scan rates are shown in Fig. 2. In these CVs, waves appear for the  couple at Eo′ = 0.82 V [vs. normal hydrogen electrode (NHE)], a kinetically distorted wave (10) at ∼1.3 V for the

couple at Eo′ = 0.82 V [vs. normal hydrogen electrode (NHE)], a kinetically distorted wave (10) at ∼1.3 V for the  couple and a barely discernible wave at Ep,a = ∼ 1.60 V for oxidation of RuIV = O2+ to RuV = O3+ (1, 5). At the slow scan rates of 100–10 mV/s, there is evidence for a slightly increased catalytic current above the electrode background at 1.60 V consistent with electrocatalyzed water oxidation. An increase in i/υ1/2 with decreasing scan rate is expected for a rate-limiting chemical step before diffusional electron transfer at the electrode (11–13). The analogous phosphonate-derivatized complex {Ru(Mebimpy)[4,4′-((HO)2OPCH2)2bpy](OH2)}2+ on oxide electrode surfaces has also been shown to be an electrocatalyst for water oxidation. (7)

couple and a barely discernible wave at Ep,a = ∼ 1.60 V for oxidation of RuIV = O2+ to RuV = O3+ (1, 5). At the slow scan rates of 100–10 mV/s, there is evidence for a slightly increased catalytic current above the electrode background at 1.60 V consistent with electrocatalyzed water oxidation. An increase in i/υ1/2 with decreasing scan rate is expected for a rate-limiting chemical step before diffusional electron transfer at the electrode (11–13). The analogous phosphonate-derivatized complex {Ru(Mebimpy)[4,4′-((HO)2OPCH2)2bpy](OH2)}2+ on oxide electrode surfaces has also been shown to be an electrocatalyst for water oxidation. (7)

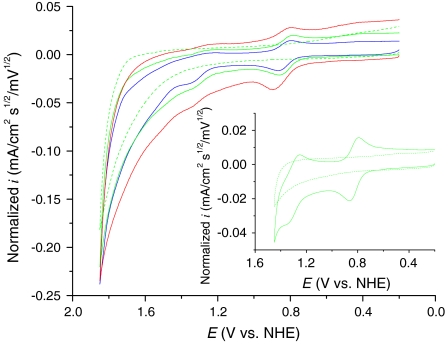

Fig. 2.

Normalized CVs (i/υ1/2 vs. potential with i the current density in mA/cm2 and υ the scan rate in mV/s) for 1 mM 1 in 0.1 M HNO3 at a GC electrode as a function of scan rate at room temperature. Red line, 1000 mV/s; green line, 100 mV/s; blue line, 10 mV/s. Inset, CV at 100 mV/s showing the Ru(III/II) and Ru(IV/III) redox couples as a reference. The dotted lines are the GC background at 100 mV/s.

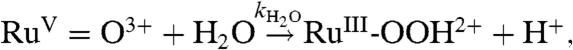

The mechanism for electrocatalytic water oxidation is presumably the same as in Scheme 1 but with the electrode providing oxidative equivalents rather than Ce(IV). In this mechanism, oxidation of RuIV = O2+ to RuV = O3+ at Ep,a = ∼ 1.60 V, Eq. 1a, is followed by O-atom transfer from RuV = O3+ to a water molecule to give a peroxidic intermediate, Eq. 1b, as in Scheme 1. Once formed, the peroxidic intermediate undergoes multielectron oxidation, Eq. 2a, Eq. 2b, accounting for the catalytic current at slow scan rates (7). Based on the results of an independent kinetic study, kH2O = 3.1 × 10-3 s-1 for O-atom transfer to water by [RuV(Mebimpy)(bpy)(O)]3+ in Eq. 1b (5).

| [1a] |

|

[1b] |

| [2a] |

| [2b] |

Reaction Mechanism. The O—O Bond Forming Step.

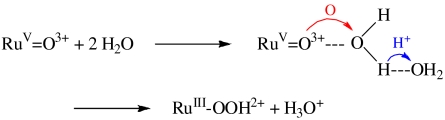

The details of the key, rate-limiting O—O bond-forming step in Eq. 1b have been investigated for a series of RuV = O3+ complexes by using the recently developed QM/MM-MFEP (minimal free energy path) method (14–18). This method allows for an ab initio description of the solute and a realistic and detailed description of the solvent. Simulation details and optimized reactant and product geometries for different complexes are provided in SI Text. These calculations reveal that in the lowest energy pathway for O—O coupling, a second water molecule is involved. Its role is to solvate the released proton. This pathway, Eq. 3, avoids the high energy, coordinated isomeric hydrogen peroxide intermediate [RuIII(Mebimpy)(bpy)(OOH2)]3+.  3

3

For [RuV(tpy)(bpm)(O)]3+, several different initial geometries of two QM water molecules were chosen and optimized by the QM/MM-MFEP method with optimized geometries leading to the preferred geometry in Fig. S1 in all cases. The optimized reactant and product geometries for the series of oxidants [RuV(tpy)(bpm)(O)]3+, [RuV(tpy)(bim-py)(O)]3+, [RuV(Mebimpy)(bpm)(O)]3+, and [RuV(Mebimpy)(bpy)(O)]3+, Fig. S1–S4, were very similar. The O-O distance between the reacting water molecule and the oxo group in RuV = O3+ was ∼1.5 Å, and the Ru = O bond length remained nearly constant through the reaction. The O-H distance in the reacting water molecule varied from 1.3 to 1.45 Å compared with 1.0 Å for O-H in a normal water molecule. The lengthening is consistent with considerable O-H bond weakening due to interaction with RuV = O3+ and the second water molecule acting as proton acceptor.

The results of the QM/MM simulations are qualitatively consistent with experimental trends in reactivity, Table S1. All RuV = O3+ oxidants share the same low-energy barrier (< 10 kcal/mol) pathway illustrated in Eq. 3 and Fig. S5 with barriers listed in Table S1. In this pathway, the oxo group in RuV = O3+ attacks a H2O molecule to form a peroxidic intermediate with a second water molecule accepting the released proton. Water functions as the acceptor base generating H3O+ even though pKa(H3O+) = -1.74. (19) This highlights the importance of the accompanying concerted proton transfer in avoiding a high-energy protonated peroxidic intermediate. It also suggests a role in catalytic water oxidation by concerted pathways with O-atom transfer coupled with proton transfer to added acceptor base, Fig. S6.

Rate Acceleration with Added Bases.

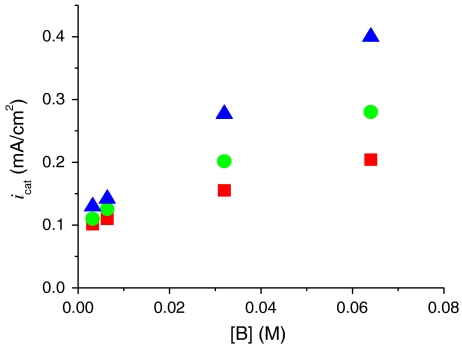

Of considerable importance for catalytic water oxidation by metal complexes is our observation of significant enhancements in catalytic currents for water oxidation, icat (the catalytic current in mA/cm2) with added proton bases  , acetate (OAc-), or

, acetate (OAc-), or  . Organic bases such as phthalate, histidine, citrate, or Hepes [4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonate] cannot be used because of background oxidation of the base either at the electrode or by RuV = O3+/RuIV = O2+. As shown in Fig. 3 Upper, icat for [Ru(Mebimpy)(bpy)(OH2)]2+ increases with increasing base concentration. This is a base effect and not a pH effect. Variations in the HOAc/OAc- buffer ratio and pH from 4 to 5.75 at fixed [OAc-] (0.064 M) had no effect on icat.

. Organic bases such as phthalate, histidine, citrate, or Hepes [4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonate] cannot be used because of background oxidation of the base either at the electrode or by RuV = O3+/RuIV = O2+. As shown in Fig. 3 Upper, icat for [Ru(Mebimpy)(bpy)(OH2)]2+ increases with increasing base concentration. This is a base effect and not a pH effect. Variations in the HOAc/OAc- buffer ratio and pH from 4 to 5.75 at fixed [OAc-] (0.064 M) had no effect on icat.

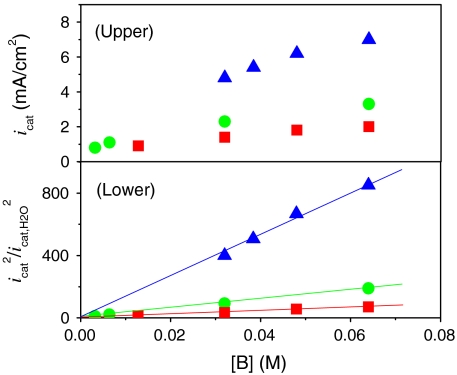

Fig. 3.

(Upper) Variations in catalytic current density (icat in mA/cm2; background subtracted) for 1 mM 1 at a GC electrode at room temperature with added bases:  at pH 2.4 (▪), OAc- at pH 5 (•), and

at pH 2.4 (▪), OAc- at pH 5 (•), and  at pH 7.45 (▴). (Lower) Plots of (icat/icat,H2O)2 vs. [B]. Ionic strength (I = 0.1 M) was maintained with added KNO3; scan rate, 100 mV/s. See CVs in Fig. S7.

at pH 7.45 (▴). (Lower) Plots of (icat/icat,H2O)2 vs. [B]. Ionic strength (I = 0.1 M) was maintained with added KNO3; scan rate, 100 mV/s. See CVs in Fig. S7.

The increase in icat with added base is consistent with an additional, base-dependent pathway for water oxidation and a second term in the rate law for O-atom transfer from RuV = O3+ to H2O, Eq. 4.

| [4] |

For a catalytic, rate-limiting chemical step preceding electron transfer at the electrode, current enhancements with added base are predicted to vary with  for a solution catalyst, Eq. 5 (11–13). As shown in Fig. 3 Lower, this prediction is observed experimentally. Rate constants for the base catalyzed pathway, kB, were calculated from the slopes of plots of (icat/icat,H2O)2 vs [B] by use of Eq. 5. As noted above, the value kH2O = 3.1 × 10-3 s-1 was available from the earlier independent kinetic study (5). The resulting values are listed in Table 1.

for a solution catalyst, Eq. 5 (11–13). As shown in Fig. 3 Lower, this prediction is observed experimentally. Rate constants for the base catalyzed pathway, kB, were calculated from the slopes of plots of (icat/icat,H2O)2 vs [B] by use of Eq. 5. As noted above, the value kH2O = 3.1 × 10-3 s-1 was available from the earlier independent kinetic study (5). The resulting values are listed in Table 1.

| [5] |

The data in Fig. 3 and the rate constants in Table 1 illustrate that significant rate enhancements occur for the base catalyzed pathways. For example, icat reaches 9.1 mA/cm2 in a solution 0.1 M in  (pH 7.45) at 100 mV/s compared to 0.24 mA/cm2 in 0.1 M HNO3.

(pH 7.45) at 100 mV/s compared to 0.24 mA/cm2 in 0.1 M HNO3.

Table 1.

Rate constants for base-assisted O-atom transfer from RuV = O3+ to H2O at room temperature, Eq. 4. kB and kH2O were evaluated from the slopes and intercepts of plots of (icat/icat,H2O)2 vs. [B], Fig. 3 Lower, according to Eq. 5. Ionic strength (I = 0.1 M) was maintained with added KNO3.

| B | pKa (HB) | kB (M-1 s-1) |

|

2.15 | 3.8 ± 0.5 |

| OAc- | 4.75 | 10.3 ± 1 |

|

7.20 | 48 ± 5 |

| H2O | −1.74 | kH2O ∼ 3.5 × 10-3 s-1 |

The addition of even higher concentrations of OAc- or  resulted in no further current enhancements, apparently due to complications arising from anation, e.g.,

resulted in no further current enhancements, apparently due to complications arising from anation, e.g.,  . Evidence for anation is found in a shift in the intense metal-to-ligand charge transfer absorption band for [RuII(Mebimpy)(bpy)(OH2)]2+ from 486 nm in 0.01–0.1 M OAc- to 490 nm in 1 M OAc-. Catalysis is lost with anation since RuV = O3+ is no longer accessible by oxidation and proton loss from

. Evidence for anation is found in a shift in the intense metal-to-ligand charge transfer absorption band for [RuII(Mebimpy)(bpy)(OH2)]2+ from 486 nm in 0.01–0.1 M OAc- to 490 nm in 1 M OAc-. Catalysis is lost with anation since RuV = O3+ is no longer accessible by oxidation and proton loss from  .

.

The data in Table 1 also illustrate that kB increases with the proton acceptor ability of the base (ΔGo′ = -RTpKa). A related effect has been documented for electron–proton transfer oxidation of tyrosine arising from the effect of enhanced basicity on ΔGo′ for the concerted electron-proton transfer step (20, 21).

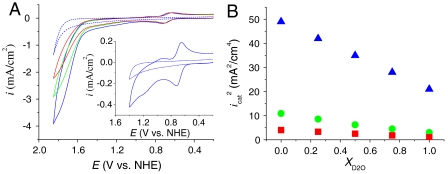

In an earlier study (7), the related phosphonate derivative 1-PO3H2 was shown to function as a water oxidation catalyst when surface bound to Sn(IV)-doped In2O3 (ITO) or fluorine-doped SnO2 (FTO) electrodes, or in nanoparticle TiO2 films on FTO (FTO|TiO2), Fig. 1B. Surface binding of the catalyst is important in accelerating rates and in minimizing the amount of catalyst used in an electrocatalytic or photoelectrocatalytic application. As shown by the data in Fig. 4, significant current enhancements with added bases are also observed for 1-PO3H2 on ITO (ITO|1-PO3H2).

Fig. 4.

As in Fig. 3, variations in icat (background subtracted) at ITO|1-PO3H2 with added bases,  at pH 2.4 (▪), OAc- at pH 5 (•), and

at pH 2.4 (▪), OAc- at pH 5 (•), and  at pH 7.45 (▴). Ionic strength (I = 0.1 M) was maintained with added KNO3; scan rate, 100 mV/s. See CVs in Fig. S8.

at pH 7.45 (▴). Ionic strength (I = 0.1 M) was maintained with added KNO3; scan rate, 100 mV/s. See CVs in Fig. S8.

Discussion

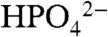

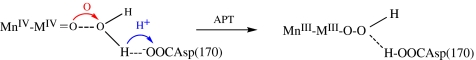

There are important insights in the electrocatalytic data. A related observation of buffer base catalysis has been reported for [M(bpy)3]3+ (M = Fe,Ru,Os) oxidation of tyrosine with added buffer bases. Base catalysis was attributed to multiple site electron–proton transfer (MS-EPT) with electron transfer to [M(bpy)3]3+ and simultaneous proton transfer to a H-bonded base. An example is shown in Eq. 6 with  as the proton acceptor base (20, 21). Relative to initial electron transfer followed by proton transfer, MS-EPT has the advantage of avoiding the high-energy 1e- intermediate TyrOH•+ with Eo′(TyrOH•+/TyrOH) = 1.34 V vs. NHE (22–24).

as the proton acceptor base (20, 21). Relative to initial electron transfer followed by proton transfer, MS-EPT has the advantage of avoiding the high-energy 1e- intermediate TyrOH•+ with Eo′(TyrOH•+/TyrOH) = 1.34 V vs. NHE (22–24).  6

6

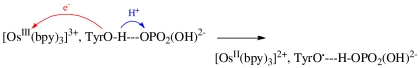

The appearance of a base-dependent pathway in water oxidation suggests a similar microscopic origin with O-atom transfer from [RuV(Mebimpy)(bpy)(O)]3+ to H2O accompanied by proton transfer to the added base, Eq. 7. As noted above, direct O-atom transfer would give the high-energy, isomeric hydrogen peroxide intermediate [RuIII(Mebimpy)(bpy)(OOH2)]3+, which is avoided in the base-assisted pathway. The viability of this pathway is supported by the MM/QM simulations, which point to water as a viable acceptor base even given the low pKa for H3O+.

The proton-coupled atom-transfer step in Eq. 7 can be described as concerted APT with O-atom transfer to the O of a water molecule coupled to proton transfer to an acceptor base (24). Consistent with the experimental results, QM/MM simulations for the reaction [RuV(Mebimpy)(bpy)(O)]3+ + H2O + OAc- show that the added proton base (OAc-) lowers the activation barrier, Fig. S5 and Table S1.  7

7

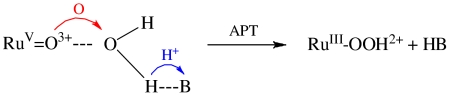

A related pathway may play a key role in water oxidation in the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II (PSII). The key O—O coupling step in PSII has been proposed to occur by O-atom transfer from a MnIV-MnIV = O unit of a CaMn4 cluster to a neighboring HO-Ca. The latter was suggested to form in a thermodynamically unfavorable acid-base equilibrium with neighboring Aspartate170, Asp(170)-COO- + H2O-Ca = Asp(170)-COOH + (HO-Ca)- (25). Use of APT, Eq. 8, would avoid the unfavorable preequilibrium.  8

8

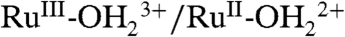

There is a significant H2O/D2O kinetic isotope effect (KIE) of 2.1 for tyrosine oxidation by MS-EPT in Eq. 6. It arises from the quantum nature of the coupled proton transfer (21, 24). As shown by CV comparisons for the solution catalyst in H2O/D2O solvent mixtures, Fig. 5A, there is also a significant H2O/D2O KIE for icat under conditions where the kB pathway in Eq. 4 dominates.

Fig. 5.

As in Fig. 3, (A) CVs of 1 mM 1 in H2O/D2O solvent mixtures 0.064 M in OAc- at pH 5. Red line, XD2O = 1; green line, XD2O = 0.5; blue line, XD2O = 0. Inset, CV in H2O showing the Ru(III/II) and Ru(IV/III) redox couples of 1 as a reference. (B) Dependence of  (background subtracted) of 1 mM 1 on XD2O 0.064 M in

(background subtracted) of 1 mM 1 on XD2O 0.064 M in  at pH 2.4 (▪), 0.064 M in OAc- at pH 5 (•), and 0.064 M in

at pH 2.4 (▪), 0.064 M in OAc- at pH 5 (•), and 0.064 M in  at pH 7.45 (▴) under conditions where the kB pathway in Eq. 4 dominates. The dotted lines are the GC background with XD2O = 0. XD2O is the mole fraction of D2O. GC working electrode; I = 0.1 M; scan rate, 100 mV/s; room temperature.

at pH 7.45 (▴) under conditions where the kB pathway in Eq. 4 dominates. The dotted lines are the GC background with XD2O = 0. XD2O is the mole fraction of D2O. GC working electrode; I = 0.1 M; scan rate, 100 mV/s; room temperature.

As shown for all three bases in Fig. 5B,  decreases linearly with the mole fraction of D2O (χD2O). This observation is consistent with a single pathway and transfer of a single proton in the rate-limiting step (26, 27). From the experimental rate constant ratios, kcat,H2O/kcat,D2O = (icat,H2O/icat,D2O)2, H2O/D2O KIE values for the solution reactions are 3.9 (

decreases linearly with the mole fraction of D2O (χD2O). This observation is consistent with a single pathway and transfer of a single proton in the rate-limiting step (26, 27). From the experimental rate constant ratios, kcat,H2O/kcat,D2O = (icat,H2O/icat,D2O)2, H2O/D2O KIE values for the solution reactions are 3.9 ( ), 3.4 (OAc-), and 2.3 (

), 3.4 (OAc-), and 2.3 ( ), as listed in Table 2.

), as listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

H2O/D2O KIE for base-assisted O-atom transfer from RuV = O3+ to H2O at room temperature, Eq. 4; the KIE values for solution catalysis were calculated from the experimental rate constant ratios, kcat,H2O/kcat,D2O = (icat,H2O/icat,D2O)2, in Fig. 5B

| B | H2O |  |

OAc- |  |

| KIE | 6.6 | 3.9 | 3.4 | 2.3 |

The KIE for the base independent pathway, with D2O as acceptor base, was determined by measurements in D2O with added OAc-. The value kD2O = 4.7 × 10-4 s-1 was calculated from the slope of a plot of (icat/icat,D2O)2 vs. [OAc-] and Eq. 5, which gave kH2O/kD2O = 6.6, in Table 2. A KIE of this magnitude is consistent with H2O acting as an APT acceptor base. It points to the importance of quantum effects in the transfer of the proton in APT as it is in MS-EPT. Also consistent is the increase in KIE with decreasing base strength (-RTpKa) through the series from water (6.6) to  (2.3) consistent with a decrease in APT proton transfer distance through the series as the strength of the acceptor base increases.

(2.3) consistent with a decrease in APT proton transfer distance through the series as the strength of the acceptor base increases.

Our observation of significant water oxidation catalysis with added bases is an important finding for the design of functional catalysts for water oxidation. From the data in Table 1 with 0.1 M added  ,

,  and the half time for a catalytic turnover is 0.1 s in solution. This is a rate enhancement of 1,400 (7.8 × 105 on a per molecule basis) compared to H2O as the acceptor base. The fact that the APT base catalyzed pathway also appears for ITO|1-PO3H2 is significant in showing that enhanced APT reactivity can be transferred to conducting or semiconductor solution interfaces in a device configuration.

and the half time for a catalytic turnover is 0.1 s in solution. This is a rate enhancement of 1,400 (7.8 × 105 on a per molecule basis) compared to H2O as the acceptor base. The fact that the APT base catalyzed pathway also appears for ITO|1-PO3H2 is significant in showing that enhanced APT reactivity can be transferred to conducting or semiconductor solution interfaces in a device configuration.

Materials and Methods

Deuterium oxide (D2O, 99.9%), nitric acid (70%, redistilled, trace metal grade), nitric acid-d (65 wt. % in D2O, 99 atom % D), acetic acid (99.9%), sodium acetate (≥99%), phosphoric acid (60%, redistilled, trace metal grade), RuCl3·3H2O, and 2,2′-bipyridine (bpy, ≥99%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used as received. NaH2PO4 (≥99.5%) and NaH2PO4 (≥99.5%) were obtained from Fluka. Ligand 2,6-bis(1-methylbenzimidazol-2-yl)pyridine (Mebimpy) was prepared by modification of the procedure reported for 2,6-bis(benzimidazol-2-yl)pyridine (28). Synthesis of the water oxidation catalyst [Ru(Mebimpy)(bpy)(OH2)]2+ (1) and {Ru(Mebimpy)[4,4′-((HO)2OPCH2)2bpy](OH2)}2+ (1-PO3H2) has been reported elsewhere (6). ITO glasses (Rs = 4–8 Ohms) were purchased from Delta Technologies. All other reagents were American Chemical Society grade and used as received. All solutions were prepared with Milli-Q ultrapure H2O (> 18 MΩ), D2O, or their mixtures.

Electrochemical measurements were performed with an EG&G Princeton Applied Research Potentiostat/Galvanostat Model 273A. The three-electrode configuration consisted of a glassy carbon (diameter 3 mm) or a glass slide (area 1.25 cm2) working electrode, a coiled Pt wire counter electrode, and a Ag/AgCl reference electrode (0.197 vs. NHE). Before each measurement, glassy carbon electrodes were polished with 0.05 μm alumina slurry to obtain a mirror surface and then sonicated and thoroughly rinsed with Milli-Q H2O, D2O, or H2O/D2O mixtures, the latters for kinetic isotope effect measurements. Stable phosphonate surface binding of 1-PO3H2 on cleaned ITO (ITO|1-PO3H2) was achieved following exposure of the substrates to a 0.1 mM stock solution of 1-PO3H2 in methanol for 2 h with saturation coverage of 1.2 × 10-10 mol/cm2 (7). All potentials reported are vs. NHE. All experiments were performed at room temperature (25 ± 2 °C).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

Funding by the Chemical Sciences, Geosciences and Biosciences Division of the Office of Basic Energy Sciences, U.S. Department of Energy through Grant DE-FG02-06ER15788 supporting preliminary experiments, Army Research Office through Grant W911NF-09-1-0426 supporting surface experiments and Z.C., and the UNC EFRC: Solar Fuels and Next Generation Photovoltaics, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Award DE-SC0001011 supporting J.J.C., X.H., and P.G.H. is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/1001132107/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Concepcion JJ, Jurss JW, Templeton JL, Meyer TJ. One site is enough. Catalytic water oxidation by [Ru(tpy)(bpm)(OH2)]2+ and [Ru(tpy)(bpz)(OH2)]2+ J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:16462–16463. doi: 10.1021/ja8059649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDaniel ND, Coughlin FJ, Tinker LL, Bernhard S. Cyclometalated iridium(III) aquo complexes: Efficient and tunable catalysts for the homogeneous oxidation of water. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:210–217. doi: 10.1021/ja074478f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tseng HW, Zong R, Muckerman JT, Thummel R. Mononuclear ruthenium(II) complexes that catalyze water oxidation. Inorg Chem. 2008;47:11763–11773. doi: 10.1021/ic8014817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hull JF, et al. Highly active and robust Cp* iridium complexes for catalytic water oxidation. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:8730–8731. doi: 10.1021/ja901270f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Concepcion JJ, Tsai MK, Muckerman JT, Meyer TJ. Mechanism of water oxidation by single-site ruthenium complex catalysts. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:1545–1557. doi: 10.1021/ja904906v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Concepcion JJ, et al. Catalytic water oxidation by single site ruthenium catalysts. Inorg Chem. 2009;49:1277–1279. doi: 10.1021/ic901437e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen ZF, Concepcion JJ, Jurss JW, Meyer TJ. Single-site, catalytic water oxidation on oxide surfaces. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:15580–15581. doi: 10.1021/ja906391w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Concepcion JJ, et al. Making oxygen with ruthenium complexes. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42:1954–1965. doi: 10.1021/ar9001526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alstrum-Acevedo JH, Brennaman MK, Meyer TJ. Chemical approaches to artificial photosynthesis. Inorg Chem. 2005;44:6802–6827. doi: 10.1021/ic050904r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trammell SA, et al. Mechanisms of surface electron transfer. Proton-coupled electron transfer. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:13248–13249. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kutner W, Meyer TJ, Murray RW. Electrochemical and electrocatalytic reactions of a ruthenium oxo complex in solution and in cation exchange beads in carbon paste electrodes. J Electroanal Chem. 1985;195:375–394. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bard AJ, Faulkner LR. Electrochemical Methods: Fundamentals and Applications. 2nd. New York: John Wiley; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zanello P. Inorganic Electrochemistry: Theory, Practice and Application. Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu H, Lu ZY, Parks JM, Burger SK, Yang WT. Quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics minimum free-energy path for accurate reaction energetics in solution and enzymes: Sequential sampling and optimization on the potential of mean force surface. J Chem Phys. 2008;128(3):034105. doi: 10.1063/1.2816557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu H, Lu ZY, Yang WT. QM/MM minimum free-energy path: methodology and application to triosephosphate isomerase. J Chem Theory Comput. 2007;3:390–406. doi: 10.1021/ct600240y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu H, Yang WT. Free energies of chemical reactions in solution and in enzymes with ab initio quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics methods. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2008;59:573–601. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.59.032607.093618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu H, Boone A, Yang WT. Mechanism of OMP decarboxylation in orotidine 5′-monophosphate decarboxylase. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:14493–14503. doi: 10.1021/ja801202j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parks JM, Hu H, Rudolph J, Yang WT. Mechanism of Cdc25B phosphatase with the small molecule substrate p-nitrophenyl phosphate from QM/MM-MFEP calculations. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:5217–5224. doi: 10.1021/jp805137x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jencks WP. Catalysis in Chemistry and Enzymology. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1969. p. 172. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fecenko CJ, Thorp HH, Meyer TJ. The role of free energy change in coupled electron-proton transfer. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:15098–15099. doi: 10.1021/ja072558d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fecenko CJ, Meyer TJ, Thorp HH. Electrocatalytic oxidation of tyrosine by parallel rate-limiting proton transfer and multisite electron-proton transfer. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:11020–11021. doi: 10.1021/ja061931z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sjödin M, Styring S, Åkermark B, Sun L, Hammarström L. Proton-coupled electron transfer from tyrosine in a tyrosine-ruthenium-tris-bipyridine complex: Comparison with tyrosineZ oxidation in photosystem II. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:3932–3936. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carra C, Iordanova N, Hammes-Schiffer S. Proton-coupled electron transfer in a model for tyrosine oxidation in photosystem II. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:10429–10436. doi: 10.1021/ja035588z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huynh MHV, Meyer TJ. Proton-coupled electron transfer. Chem Rev. 2007;107:5004–5064. doi: 10.1021/cr0500030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyer TJ, Huynh MHV, Thorp HH. The possible role of proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) in water oxidation by photosystem II. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:5284–5304. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Albery WJ, Davies MH. Mechanistic conclusions from the curvature of solvent isotope effects. J Chem Soc, Faraday Trans 1. 1972;68:167–181. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Melander L, Saunders WH. Reaction Rates of Isotopic Molecules. New York: John Wiley; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu X, Xi Z, Chen W, Wang D. Synthesis and structural characterization of copper(II) complexes of pincer ligands derived from benzimidazole. J Coord Chem. 2007;60:2297–2308. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.