Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Preimplantation factor (PIF) is a novel, 15 amino acid peptide, secreted by viable embryos. This study aims to elucidate PIF’s effects in human endometrial stromal cells (HESC) decidualized by estrogen and progestin, which mimics the pre-implantation milieu, and in first trimester decidua cultures (FTDC).

STUDY DESIGN

HESC or FTDC were incubated with 100nM synthetic PIF or vehicle control. Global gene expression was analyzed using microarray and pathway-analysis. Proteins were analyzed using quantitative mass-spectrometry, and PIF binding by ProtoArray.

RESULTS

Gene and proteomic analysis demonstrate that PIF affects immune, adhesion and apoptotic pathways. Significant upregulation in HESC (fold-change) include: NF-k-β activation via IRAKBP1 (53); TLR5 (9); FKBP15 protein (2.3); DSCAML1 (16). BCL-2 was downregulated in HESC (21.1) and FTDC (27.1). ProtoArray demonstrates PIF interaction with intracellular targets insulin degrading enzyme and beta-K+ channels.

CONCLUSION

PIF displays essential multi-targeted effects, of regulating immunity, promoting embryo-decidual adhesion, and regulating adaptive apoptotic processes.

Keywords: Preimplantation Factor, decidual cells, genomics, proteomics, implantation

INTRODUCTION

The mammalian embryo/allograft may be considered a ‘perfect transplant”. The mother/host tolerates the invading embryo and subsequent feto-placental unit while preserving maternal immunity, ability to fight infection and to control autoimmune processes (1–5). Multiple factors have to act synergistically to allow such pregnancy-specific immune paradox (6–13). Maternal recognition of pregnancy occurs even before implantation, thus indicating that embryo-specific signaling is present before the embryo is in intimate contact with the endometrium (14–17).

Decidual cells play a central role in implantation (18), and they have been investigated extensively using a well established in vitro culture system based upon induction of decidualization using ovarian steroids (19). This culture system serves as valuable model to examine the role of different compounds during peri-implantation, a time frame in human reproduction which poses challenges to investigation in vivo.

Preimplantation factor (PIF) (MVRIKPGSANKPSDD) is a novel peptide, secreted only by viable embryos, absent in non-viable ones, detected in the circulation of several species of pregnant mammals, and expressed in the placenta (20–25). Recently, we demonstrated that synthetic PIF, replicates native PIF action, modulates peripheral immune cells, and creates a favorable immune environment shortly after fertilization (26). PIF regulates uterine natural killer cell toxicity in vivo, implying that PIF contributes to the maternal adaptation to pregnancy (27).

Herein, we used genomic and proteomic analysis to further define PIF’s precise mechanism of action in a well characterized in vitro system of human endometrial stromal cells (HESC) decidualized by estrogen and progestin, which mimics the pre-implantation milieu, and in first trimester decidua cultures (FTDC) (28).

METHODS

Peptide synthesis

Synthetic PIF analog (MVRIKPGSANKPSDD), was produced using solid-phase peptide synthesis (Peptide Synthesizer, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) employing Fmoc (9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl) chemistry. Final purification was carried out by reversed-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC), and peptide identity was verified by mass spectrometry. Alexafluor647-PIF conjugate was generated as well (Bio-Synthesis, Inc., Lewisville, TX).

Endometrial cell cultures

Institutional review board approval was obtained for this study. Discarded endometrial tissue from premenopausal women undergoing hysterectomies due to benign indications were used. Decidual specimens from the first trimester were obtained from women undergoing elective terminations in weeks 6–12 of normal pregnancy.

Using our previously established cell culture method, we studied non-pregnant HESC and cells collected from healthy first trimester of pregnancy decidua (29). Endometrial and decidual cells were isolated and re-suspended in RPMI-1640, grown to confluence and found to be leukocyte free (<1%). After reaching confluence, cells were decidualized using 10−8M estradiol and 10−7M, synthetic progestin analog (R5020) (Du Pont/NEN, Boston, MA) in both cases for seven days. Cells were switched to a serum free media containing (insulin, transferrin, and selenium) (Collaborative Research, Inc., Waltham, MA), 5μM trace elements (GIBCO), and 50 μg/ml ascorbic acid (Sigma-Aldrich), and treated overnight with synthetic PIF (100 nM) or vehicle control. The tissue was collected and frozen at −80ºC.

Microarray analysis

Total RNA was extracted from each cell culture. Analysis of HESCs or FTDC +/−PIF 100 nM (n=3/group) was examined using Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA) U133 Plus 2.0 Array (18,400 human genes), followed by fluorescence labeling and hybridization with Fluidics Station 450 and and optical scanning with GeneChip Scanner 3000 (Affymetrix), at W.M. Keck Foundation Biotechnology Resource Laboratory, Yale University.

Raw data was analyzed by GeneSpring software (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA), normalized for inter- and intra-chip variation to eliminate false positive results (30).

Mass spectrometry analysis

HESC protein lysates (n=3/group) were homogenized in buffer (100 mM Tris 250 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS) and assayed for protein concentration. Ten μg of each lysate was loaded in singlet onto a Novex 4–12% SDS-PAGE gel, (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) followed by electrophoresis. Each lane was excised into 10 equal slices, digested with trypsin, and analyzed by nano-liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (nano-LC/MS/MS) on an LTQ-Orbitrap XL tandem mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher, San Jose, CA). Data were searched against the Mascot concatenated forward-and-reversed v3.46 International Protein Index (IPI) database (Matrix Science Ltd., London, U.K.) and collated into non-redundant lists using Scaffold software (Proteome Software Inc., Portland, OR). A dual filtering strategy of target-decoy database searching and employing the Peptide and ProteinProphet algorithms provides high confidence in the proteins identified (FDR<0.5%).

Expression of Toll Like Receptor (TLR)-2 in FTDC

Western blotting for TLR-2 (diluted 1:1000) and β-actin (diluted 1:10,000) was conducted (n=1) using established methods (31). Antibodies for TLR-2 and β-actin were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) and Abcam, Inc. (Cambridge, MA), respectively. Densitometric analyses were carried out with the National Institutes of Health’s ImageJ software (available at http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij). Values were expressed as the ratio of TLR-2 to actin, correcting for loading efficiency.

Alexa-PIF interaction with human proteome array

ProtoArray Human Protein Microarrays v5.0 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with 9000 possible targets, were initially blocked followed by exposure to PIF-Alexa 647 (250 nM and 2.5 μM). Unbound probe was washed off, and arrays were assessed by a fluorescence microarray scanner. As negative control, an array was incubated with wash buffer while calmodulin kinase was used as positive control detected by Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated anti-V5 antibody. Three stringent conditions determined Alexa-PIF specificity of binding: signal value >200 relative fluorescent units, >6 time higher than the negative control, and Z-factor > 5.

Statistical analysis

For gene experiments, data was first analyzed using student’s t test, with p<0.05 results, followed by fold-change testing, with a cutoff >2- fold only reported. Pathway analysis was performed using the Ingenuity Systems (Redwood, CA) software, ranking by greatest number of genes in a given pathway. For proteome data, spectral counting was employed for relative quantitation and student’s t-test p<0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Effect of PIF on HESCs

PIF 100nM significantly changed >500 genes. The genes that were significantly (>10-fold change) are featured in Table 1. Notably, there was an 18.1 fold decrease in PDE4B, a gene encoding for a protein that specifically hydrolyzes cAMP, a critical molecule promoting decidualization (32).

TABLE 1.

PIF Effect on HESC genome, P<0.05

| GENE | Description | FOLD PIF/Control |

|---|---|---|

| IRAK1BP1 | IL-1 receptor-assoc kinase1 bind. Prot1 | 53 |

| CALD1 | caldesmon 1 | 29.9 |

| STX3 | syntaxin 3 | 22.8 |

| DSCAML1 | Down syndrome cell adhesion like 1 | 16 |

| FNDC3B | fibronectin type III domain containing 3B | 14.7 |

| TLX2 | T-cell leukemia homeobox 2 | 13.8 |

| UNC5CL | unc-5 homolog C (C. elegans)-like | 11.9 |

| RPE65 | retinal pigment epithelium protein 65kDa | 11.8 |

| SLC22A1 | solute carrier family 22 A1 | 11.6 |

| GABRG1 | GABA A receptor, gamma 1 | 11.6 |

| ZNF148 | zinc finger protein 148 | −16.6 |

| GRM1 | glutamate receptor, metabotropic 1 | −17.2 |

| PDE4B | phosphodiesterase 4B, cAMP-specific, E4 | −18.1 |

| RYBP | RING1 and YY1 binding protein | −19.3 |

| TLK1 | tousled-like kinase1 | −19.6 |

| BCL2 | B-cell CLL/lymphoma2 | −21.2 |

| COL8A1 | collagen, type VIII, alpha1 | −24.9 |

| GBF1 | golgi-specific brefeldin A resistance factor1 | −26.2 |

| VPS26A | vacuolar protein sorting 26 homolog A | −29 |

| MCCC2 | methylcrotonoyl-Coenzyme A carboxylase2B | −33.1 |

We focused on three pathways that are relevant for implantation: 1) immune-tolerance; 2) embryo adhesion; and 3) apoptosis/remodeling.

Effects on HESC gene expression

Immune pathway

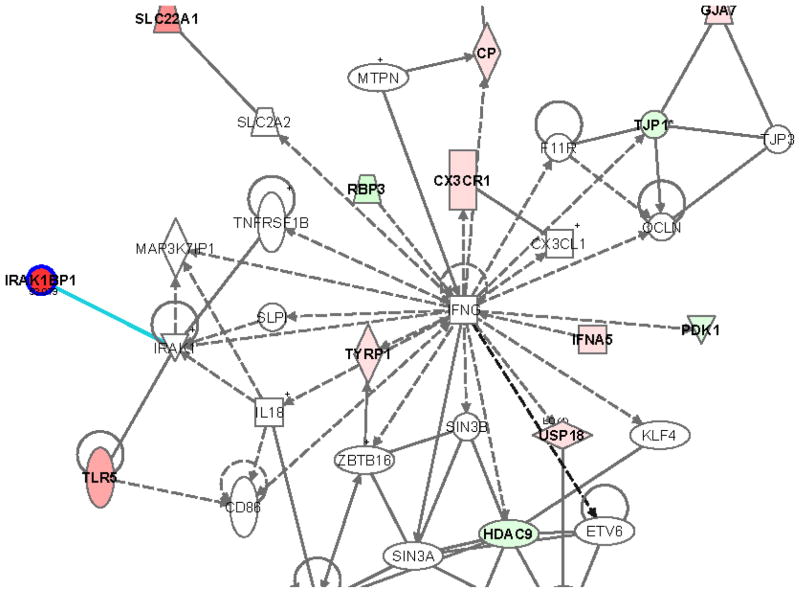

PIF increased IRAK1BP1 (53-fold), which interacts with TLR5 (Figure 1), a pathway involved in innate immune response to microbial agents. A decrease in IL12RB2 (9.1-fold), a receptor for a Th1 cytokine promoter of T cell proliferation and interferon secretion, was observed. PIF modulates the calcineurin pathway by down-regulating FKBPA1 (2.8-fold). The IgG immunoglobulin genes SEMA3D and SEMA3C were down regulated, 10.8- and 9.9- fold, respectively.

Figure 1. PIF-induced modulation of the TLR5 pathway in HESC.

Green reflects downregulation while red reflects upregulation. The intensity of the color reflects the extent of change in mRNA detection. Ingenuity Systems Inc. Redwood Ca.

Adhesion pathway

PIF upregulated DSCAML1 (16-fold) and SORBS2 (2.6 -fold), which interacts with actin cytoskeleton. Connexin 45, a gene encoding for a protein that facilitates cellular interaction, was upregulated 2.1-fold.

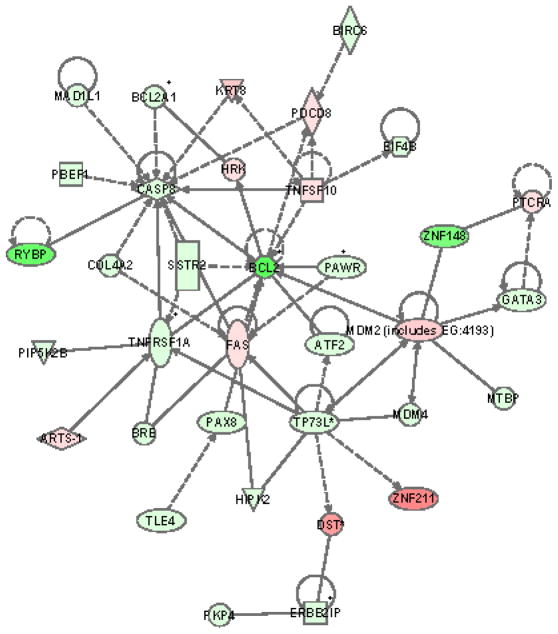

Apoptotic pathway

Figure 2 demonstrates that PIF suppressed Bcl-2 (21.1- fold), and induced down-stream effects in the Bcl-2 network. PIF increased MDM2 (5-fold), resulting in limiting cell proliferation via interaction with P53, thus favoring apoptosis. PIF upregulated BCOR (4.2-fold), which acts as a Bcl6 co-repressor.

Figure 2. PIF-induced modulation of the BCL2 pathway in HESC.

Green reflects downregulation while red reflects upregulation. The intensity of the color reflects the extent of change in mRNA detection. Ingenuity Systems Inc. Redwood Ca.

Effect of PIF on gene expression in FTDC

PIF affected over >500 genes. Table 2 lists the genes with the most significant change (> 16-fold).

TABLE 2.

PIF effect on HESC proteins (p<0.05)

| GENE- PROTEIN | Accession | FOLD PIF/control |

|---|---|---|

| RPS23 40S ribosomal protein S23 | IPI00218606 | 10 |

| CAPNS1 Calpain small subunit 1 | IPI00025084 | 6 |

| AGRN Agrin precursor | IPI00374563 | 5.5 |

| NDUFS3 NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulfur 3 | IPI00025796 | 5.3 |

| MIF Macrophage migration inhibitory factor | IPI00293276 | 5 |

| RPL10 60S ribosomal protein L10 | IPI00554723 | 4.9 |

| EIF5A Isoform 2 of Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A-1 | IPI00376005 | 4.6 |

| BAG2 BAG family molecular chaperone regulator 2 | IPI00000643 | 4 |

| PPFIBP1 Isoform 2 of Liprin-beta-1 | IPI00179172 | 3.9 |

| FBLN2 Fibulin-2 precursor | IPI00023824 | 3.9 |

| SDHA 57 kDa protein | IPI00217143 | 3.8 |

| RPS15 40S ribosomal protein S15 | IPI00216153 | 3.5 |

| RPL38 60S ribosomal protein L38 | IPI00215790 | 3.3 |

| UCHL1 Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase isozyme L1 | IPI00018352 | 3.3 |

| SH3BGRL SH3 domain-binding glutamic acid-rich-like protein | IPI00025318 | 3.07 |

| RPL18A 60S ribosomal protein L18a | IPI00026202 | 2.94 |

| RPL31 60S ribosomal protein L31 | IPI00026302 | 2.5 |

| FKBP15 Isoform 1 of FK506-binding protein 15 | IPI00853400 | 2.25 |

| PRDX6 Peroxiredoxin-6 | IPI00220301 | 2.16 |

| SORBS1 Isoform 9 of Sorbin and SH3 domain-protein 1 | IPI00002491 | 2.12 |

| HSPB1 Heat shock protein beta-1 | IPI00025512 | 2.1 |

| MAPRE1 Microtubule-associated protein RP/EB member 1 | IPI00017596 | 2 |

| RPL26 60S ribosomal protein L26 | IPI00027270 | 1.9 |

| RPS8 40S ribosomal protein S8 | IPI00216587 | 1.84 |

| CFL1 Cofilin-1 | IPI00012011 | 1.78 |

| ARCN1 Coatomer subunit delta | IPI00514053 | 1.75 |

| CAV1 Isoform Alpha of Caveolin-1 | IPI00009236 | 1.66 |

| RPL8 60S ribosomal protein L8 | IPI00012772 | 1.6 |

| HADHA Trifunctional enzyme subunit alpha, mitochondrial | IPI00031522 | 1.6 |

| CTSK Cathepsin K precursor | IPI00300599 | 1.6 |

| MT-CO2 Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 2 | IPI00017510 | 1.6 |

| CTNND1 Isoform 1AB of Catenin delta-1 | IPI00182469 | 1.52 |

| P4HB Protein disulfide-isomerase precursor | IPI00010796 | 1.5 |

| MYLK Isoform 2 of Myosin light chain kinase, smooth muscle | IPI00221255 | 1.21 |

| CLTC Isoform 1 of Clathrin heavy chain 1 | IPI00024067 | 1.12 |

| SRP68 Isoform 1 of Signal recognition particle 68 kDa protein | IPI00168388 | 0.86 |

| EPRS Bifunctional aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase | IPI00013452 | 0.84 |

| IQGAP1 Ras GTPase-activating-like protein IQGAP1 | IPI00009342 | 0.8 |

| EIF3A Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit A | IPI00029012 | 0.78 |

| EMD Emerin | IPI00032003 | 0.69 |

| RAD50 Isoform 1 of DNA repair protein RAD50 | IPI00305282 | 0.64 |

| EIF5B Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5B | IPI00299254 | 0.53 |

| SLC16A1 Monocarboxylate transporter 1 | IPI00024650 | 0.52 |

| NFIX Nuclear factor 1 | IPI00011507 | 0.2 |

| ERLIN1 ER lipid raft associated 1 | IPI00007940 | 0.01 |

Immune pathway

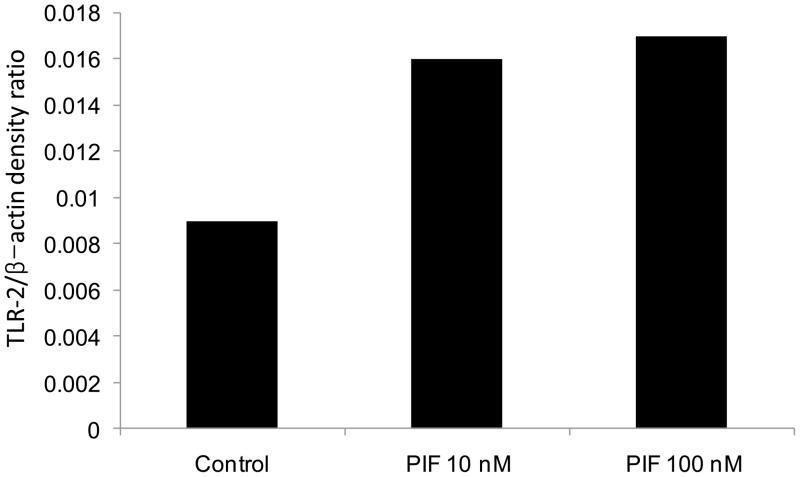

PIF increased Cx3CL1 (7.2-fold). This chemokine binds to CX3CR1, decreasing leukocyte adhesion and migration. TRAα (T cell receptor alpha) was upregulated (60.7-fold) which interacts with T cell CD3 CD3δε. IRAKBP1 was increased 27.9- fold. TLR6 was increased 2.1-fold, which interacts with TLR 2 to mediate cellular response to bacterial lipoproteins. To confirm PIF’s effects on TLR 2, we demonstrated by Western blot analysis that PIF increased TLR2 protein expression by ~90%. See Figure 3.

Figure 3. PIF-induced increase in TLR-2 expression in FTDC.

Increases in both 10 and 100nM PIF doses were noted as examined by Western blot. This reflects PIF antipathogenic effect on the early pregnancy milieu.

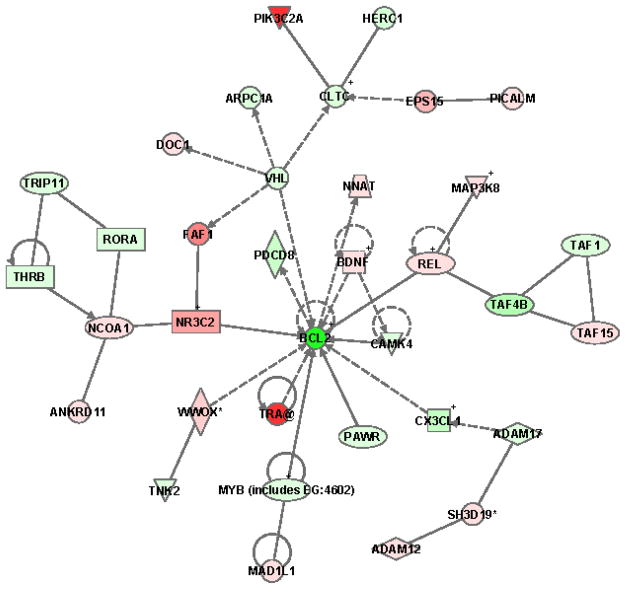

Apoptotic pathway

PIF decreased BCL2 (27.1- fold). Figure 4 demonstrates the Bcl-2 associated network in FTDC. Bcl-2 interacts with SMAD1 which was upregulated 53.4-fold. SMAD1 is a transcriptional modulator activated by BMP (bone morphogenetic proteins) type 1 receptor kinase FIF-1 FAS-related ligand increased 21.1-fold.

Figure 4. PIF-induced modulation of the BCL2 pathway in FTDC.

Green reflects downregulation while red reflects upregulation. The intensity of the color reflects the extent of change in mRNA detection. Ingenuity Systems Inc. Redwood Ca.

Control of proliferation

PIF significantly downregulated EGF receptor (24.5- fold) and further, PIF increased EPS15 expression (12.5 fold), which influences EGFR degradation by endocytosis.

PIF modulates solutes transport

PIF upregulated KLF 12 (25.7-fold) and CLNS1A(17.6-fold) which regulates the chloride channel.

Effects on HESC Proteins

Fifty out of >1000 proteins were significantly affected. See Table III.

TABLE 3.

PIF effect on FTDC genome (p<0.05)

| GENE | Description | FOLD PIF/Control |

|---|---|---|

| TRA@ | T cell receptor alpha locus | 60.7 |

| SMAD1 | SMAD, mothers against DPP homolog 1 | 53.4 |

| PIK3C2A | phosphoinositide-3-kinase, 2, A polypeptide | 37 |

| ABCG1 | ATP-binding cassette, G member 1 | 36.3 |

| LPIN1 | lipin 1 | 32.6 |

| IRAK1BP1 | IL-1 receptor-associated kinase1 bind prot 1 | 27.9 |

| SFRS3 | splicing factor, arginine/serine-rich 3 | 27 |

| FAF1 | Fas (TNFRSF6) associated factor 1 | 21.9 |

| CR1 | complement component (3b/4b) receptor1 | 20.6 |

| B3GALT2 | UDP-Gal:betaGlcNAcB1,3-galactosyltran 2 | 19.9 |

| SLC24A3 | solute carrier family 24/3 (Na/K/Ca) | −17.4 |

| CUL3 | cullin 3 | −17.7 |

| FGF12 | fibroblast growth factor 12 | −18.6 |

| SMA3 | Beta-glucuronidase-like protein | −20.4 |

| FLG | filaggrin | −22.1 |

| EGFR | epidermal growth factor receptor | −24.5 |

| EYA3 | eyes absent homolog 3 | −25. |

| MASK | serine/threonine protein kinase MST4 | −25.2 |

| KLF12 | Kruppel-like factor 12 | −25.7 |

| BCL2 | B-cell CLL/lymphoma 2 | −27. |

Immune pathway

PIF increased both Agrin 5.5-fold, a heparin sulphate expressed in immune cells, and Macrophage Inhibitory Factor (MIF) 5-fold, a regulator of macrophage migration.

Adhesion pathway

PIF increased SH3BGRL (3.1-fold), which interacts with EGFR. SORBS1 was increased 2.1-fold, which promotes formation of actin stress fibers, adhesion, and together with CTNND1, is involved in C- and E-cadherins.

Apoptotic pathway

PIF increased CAPNS1 4-fold, which promotes actin and cofilin (1.7-fold increase) based apoptosis. The increases in BAG2 (4-fold) and UCHL1 (2.7-fold) Prevent ubiquitin degradation.

Canonical pathway analysis of PIF effects on HESC and FTDC genome

Using Ingenuity software, we found the following ranking similarities between the implantation and post-implantation period: 1) Actin cytoskeleton, related to remodeling of the decidua 2) Integrin signaling, involved in embryo adhesion 3) G-protein coupled receptors, promoting embryo-maternal signaling 4) cAMP mediated signaling; a promoter of decidualization 5) Axon guidance. In contrast, ubiquination, and death receptor pathways, were highly ranked in HESC. Xenobiotic metabolism was highly represented in the FTDC. Several cytochrome p450 metabolizing enzymes (CYP2D6 and CYP2C9) and those involved in xenobiotic signaling (CAMK2B, CYP2C9, MAP3K3, and CAMK4), were observed, as were those in DNA synthesis (ENPP2, MPP5, KIF1B, ENPP3, and MPP4).

PIF acts by interacting with specific intracellular targets

Using a ProtoArray stringent analysis, we found that the top interacting protein-protein interaction candidate with PIF was insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE), followed by two transcript variants (1 and 3) of K+ voltage-gated channel, shaker-subfamily, beta1 (KCNAB1) gene. Variants of KCNAB1, and KCNAB3 were expressed in HESC. PIF down-regulated KCNMB2 9-fold, while in FTDC, KCNN2 and KCNH9 were up-regulated 13-fold and 11-fold respectively. Thus, PIF modulates specific ion channels, with diverse effects in both types of cells.

COMMENT

In this study, we demonstrated that PIF affects implantation and post implantation in decidual models. Complementary global genome and evaluable stringent proteome analysis demonstrate synergistic effects on immune, adhesion, and apoptotic/remodeling pathways in the peri-implantation model (HESC) and similarly in early pregnancy (FTDC). PIF exerts more of an ‘adaptive’ influence in FTDC by supporting protein synthesis and protecting against environmental insults.

In order to discern the relevance of our observations in complementary experiments, we employed an array of analytical tools Specifcally, we: 1) selected those genes displaying at least a two fold increase or decrease. (~500 genes fit both criteria in HESC and FTDC); 2) ranked the genes as top 10 increases and decreases in HESC and FTDC; 3) carried out system biology based interactive pathway study between different genes (Ingenuity program); 4) evaluated specific pathways relevant to implantation, namely, immune, adhesion, and apoptosis/tissue remodeling) pathways; 5) compared the ranking pathways in both HESC and FTDC as evaluated by maximal number of genes that are found to be affected in the same pathway; 6) carried out proteomic analysis in HESC cultures to confirm the involvement of various proteins, the end products of genes’ involvement in those three critical, albeit complementary, pathways; 7) used Western blot analysis to document PIF effect on FTDC; 8) examined potential PIF binding site by protein microarray.

Preimplantation Factor’s induced activation of TLR related pathways suggests that PIF impacts maternal innate immunity. NF B activation via IRAKBP1 and TNF activation by TLR5 induces an anti-infective effect (33). The increase in MIF may provide further protection by limiting macrophage migration. Maternal tolerance is supported by upregulation of FKBPA1 involved in the calcineurin pathway, where immunosuppressive agents such as FK506 and rapamycin bind (35).

PIF induced upregulation of several adhesion related genes, including DSCAML1, SORBS2, SORBS1 and Connexin 45. These findings are consistent with our previous data demonstrating that PIF increases α2β3 integrin protein in endometrial epithelial cell cultures (36). Other investigators have recognized that adhesion molecules are critical for implantation.

The Bcl-2 family of genes has both pro- and anti-apoptotic properties, whereas ubiquitins act as activators of apoptosis (37). PIF dramatically reduces Bcl-2 while increasing ubiquinating proteins. Controlled apoptosis of endometrial stromal cells is required for successful trophoblast invasion and PIF facilitates this process directly in vitro (37). The top ranking genes in HESC and FTDC experiments demonstrate the same trend in decreasing BCL2 while increasing IRAKBP1. The major increase in the FAS-related gene supports PIF’s wide-spread pro-apoptotic effects in both HESC and FTDC. Further, the major decrease in EGFR supports an anti-proliferative effect in FTDC.

Canonical analysis reveals further similarities in several pathways between HESC and FTDC genomes reflecting the sequential cascading effect of PIF at pre-, peri- and post implantation periods. Of note are protein synthesis promotion and protection against xenobiotics, cytochrome P450 metabolizing enzymes, which are essential elements for embryo support and safeguarding against environmental insults. We previously reported that these types of xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes are expressed in both embryos and placenta (39, 40).

The protein-protein interaction data provides additional insight into PIF’s potential intracellular targets and mechanism of action. Insulin-degrading enzyme probably plays a critical role in implantation, given that IDE binds to transforming growth factor alpha (TGF-α), a substrate for EGF receptor. PIF modulates K+ alpha channels and binds KCNAB1 (Kv1.3) protein variants. In HESC, PIF down regulated K+ channel genes, while in FTDC, these genes were upregulated. Interestingly, blockade of K+ channels can lead to T cell inhibition, and is considered as potential target in autoimmune diseases treatment (41). Preclinical studies to determine PIF’s potential for eventual human clinical trials in graft versus host disease and autoimmune disorders were completed (42).

Other investigators have demonstrated that activin, BMP2 and TGFb1 are likely to be involved in HESC decidualization (43–45). Since in our model decidualization was already complete by the time PIF was added, we found that a number of these genes were actually down-regulated. Cyclic AMP induced decidualization is dependent upon increased STAT3 (46). We found that in FDTC PIF actually decreased this same signaling pathway. Earlier, Lea et al examined patients’ deciduas following recurrent miscarriage and reported a decrease in TNF in some patients (47). This is of interest since FAF1, a FAS activating compound, is significantly increased in FTDC, following exposure to PIF, perhaps serving as a protective role against pregnancy loss.

Strengths of the study are: 1) We employed a well established in vitro endometrial stromal cell system; 2) Confirmatory proteomic analysis was performed to expand genomic results; 3) Synthetic PIF, whose structure is identical to native PIF, was studied, and in concentrations similar to maternal circulating levels; 4) Stringent data analysis, with ranking as well as canonical evaluation was carried out.

Limitations of this study are: 1) The use of an in vitro cell culture system is too restrictive of an environment to investigate the complex interactions of different cell types in vivo; 2) Non-pregnant HESC may not entirely replicate the native peri-mplantation environment; 3) Although significant overlap in the gene chip and protein microarrays was noted, they were not identical.

CONCLUSION

Preimplantation Factor modulates, and possibly orchestrates, maternal immunity without deleterious immune suppression, prepares the local uterine environment for implantation, and creates a supportive environment for early pregnancy. Our genomic and proteomic data significantly advance understanding of PIF’s essential multi-targeted effects of regulating immunity, promoting embryo-decidual adhesion, and regulating adaptive apoptotic processes. Relevant putative intracellular PIF mechanistic targets were identified as well. Investigations are underway to identify the specific gene responsible for PIF and confirmation of its mechanism of action. PIF is being investigated for its possible use in improving mammalian reproduction.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mr. Kevin Leitao for assistance in preparing the data for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Choudhury SR, Knapp LA. Human reproductive failure I: immunological factors. Hum Reprod Update. 2001;7:113–134. doi: 10.1093/humupd/7.2.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bainbridge D, Ellis S, Le Bouteiller P, Sargent I. HLA-G remains a mystery. Trends Immunol. 2001;22:548–552. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)02031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aplin JD, Kimber SJ. Trophoblast-uterine interaction at implantation. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2004 Jul 5;2:48. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-2-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sargent IL, Borzychowski AM, Redman CW. NK cells and human pregnancy- an inflammatory view. Trends Immunol. 2006;27:399–404. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ledee N, Dubanchet S, Oger P, Meynant C, Lombroso R, et al. Uterine Receptivity and Cytokines: New Concepts and New Applications. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2007;64:138–143. doi: 10.1159/000101737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wegmann TG, Lin H, Guilbert L, Mosman TR. Bidirectional cytokine interactions in the maternal-fetal relationship: is successful pregnancy a TH2 phenomenon? Immunol Today. 1993;14:353–356. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90235-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mellor AL, Munn DH. Extinguishing maternal immune responses during pregnancy: implications for immunosuppression. Semin Immunol. 2001;13:213–218. doi: 10.1006/smim.2000.0317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaouat G, Ledée-Bataille N, Dubanchet S, et al. TH1/TH2 paradigm in pregnancy: paradigm lost? Cytokines in pregnancy/early abortion re-examining the TH1 and TH2 paradigm. Int Arch Aller Immunol. 2004;134:93–109. doi: 10.1159/000074300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma S, Murphy SP, Barnea ER. Invited Review. Genes Regulating Implantation and Fetal Development: A Focus on Mouse Knockout Models. Frontiers in Bioscience. 2006;11:2123–37. doi: 10.2741/1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fortin M, Oulette MJ, Lambert RD. TGF-beta and PGE2 in rabbit blastocoelic fluid can modulate GM-CSF production by human lymphocytes. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1997;38:129–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1997.tb00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pinkas H, Fisch B, Tadir Y, Ovadia J, Amit S, et al. Immunosuppressive activity in culture media containing oocytes fertilized in vitro. Arch Androl. 1992;28:53–59. doi: 10.3109/01485019208987680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mattsson R, Holmdahl R, Scheynius A, Bernadotte F, Mattsson A, et al. Placental MHC class I antigen expression is induced in mice following in vivo treatment with recombinant interferon gamma. J Reprod Immunol. 1991;19:115–129. doi: 10.1016/0165-0378(91)90012-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paidas MJ, Ku DH, Davis B, Lockwood CJ, Arkel YS. Soluble monocyte cluster domain 163, a new global marker of anti-inflammatory response, is elevated in the first trimester of pregnancy. J Thromb Hemost. 2004;6:1009–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Somerset DA, Zheng Y, Kilby MD, Sansom DM, Drayson MT. Normal human pregnancy is associated with an elevation in the human suppressive CD25+CD4+ regulatory T-cell subset. Immunology. 2004;112:38–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.01869.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fuzzi B, Rizzo R, Criscuoli L, et al. HLA-G expression in early embryos is a fundamental prerequisite for the obtainment of pregnancy. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:311–315. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200202)32:2<311::AID-IMMU311>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cavanaugh AC, Morton H. The purification of early-pregnancy factor to homogeneity from human platelets and identification as chaperonin 10. Eur J Biochem. 1994;222:551–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Minhas BS, Ripps BA, Zhu YP, et al. Platelet activating factor and conception. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1996;35:267–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1996.tb00043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lockwood CJ, Schatz F. A biological model for the regulation of peri-implantational hemostasis and menstruation. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 1996 Jul-Aug;3(4):159–65. Review. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Irwin JC, Kirk D, King RJ, Quigley MM, Gwatkin RB. Hormonal regulation of human endometrial stromal cells in culture: an in vitro model for decidualization. Fertil Steril. 1989 Nov;52(5):761–8. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)61028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnea ER, Lahijani KI, Roussev R, Barnea JD, Coulam CB. Use of lymphocyte platelet binding assay for detecting a preimplantation factor: a quantitative assay. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1994;32:133–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1994.tb01103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roussev RG, Barnea ER, Thomason EJ, Coulam CB. A novel bioassay for detection of preimplantation factor (PIF) Am J Reprod Immunol. 1995;33:68–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1995.tb01140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roussev RG, Coulam CB, Kaider BD, et al. Embryonic origin of preimplantation factor (PIF): biological activity and partial characterization. Mol Hum Reprod. 1996;2:883–887. doi: 10.1093/molehr/2.11.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coulam CB, Roussev RG, Thomasson EJ, Barnea ER. Preimplantation factor (PIF) predicts subsequent pregnancy loss. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1995;34:88–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1995.tb00923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barnea ER, Simon J, Levine SP, Coulam CB, Taliadouros GS, et al. Progress in characterization of pre-implantation factor in embryo cultures and in vivo. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1999;42:95–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barnea ER. Insight into early pregnancy: emerging role of the embryo. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2004;51:319–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2004.00159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barnea ER. Preimplantation factor; an embryo-derived movel biomarker; promotes tolerance and attenuation of autoimmunity. J Reprod Immunol. 2009;81:119–120. (abst.) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Promponas E, Kerimitsoglou T, Ramu S, et al. Primplantation factor non-invasive biomarker for embryo selection in IVF. J Reprod Immunol. 2009;81:159. (abst.) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schatz F, Krikun G, Caze R, Rahman M, Lockwood CJ. Progestin-regulated expression of tissue factor in decidual cells: implications in endometrial hemostasis, menstruation and angiogenesis. Steroids. 2003 Nov;68(10–13):849–60. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(03)00139-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krikun G, Schatz F, Taylor R, Critchley HO, Rogers PA, Huang J, Lockwood CJ. Endometrial endothelial cell steroid receptor expression and steroid effects on gene expression. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(3):1812–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang SJ, Schatz F, Masch R, et al. Regulation of Chemokine Production in Response to Pro-inflammatory Cytokines in First Trimester Decidual Cells. J Reprod Immunol. 2006;72(1–2):60–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matta P, Lockwood CJ, Schatz F, Krikun G, Rahman M, Buchwalder L, Norwitz ER. Thrombin regulates monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression in human first trimester and term decidual cells. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Mar;196(3):268.e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen GA, Huang JR, Tseng L. The effect of relaxin on cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate concentrations in human endometrial glandular epithelial cells. Biol Reprod. 1988 Oct;39(3):519–25. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod39.3.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lockwood CJ, Yen CF, Basar M, Kayisli UA, Martel M, Buhimschi I, Buhimschi C, Huang SJ, Krikun G, Schatz F. Preeclampsia-related inflammatory cytokines regulate interleukin-6 expression in human decidual cells. Am J Pathol. 2008 Jun;172(6):1571–9. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070629. Epub 2008 May 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matta P, Lockwood CJ, Schatz F, Krikun G, Rahman M, Buchwalder L, Norwitz ER. Thrombin regulates monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression in human first trimester and term decidual cells. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:268.e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Than NG, Paidas MJ, Mizutani S, Sharma S, Padbury J, Barnea ER. Embryo-placento-maternal interaction and biomarkers: from diagnosis to therapy--a workshop report. Placenta. 2007;28(Suppl A):S107–10. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruvolo PP, Deng X, May WS. Phosphorylation of Bcl2 and regulation of apoptosis. Leukemia. 2001;15:515–5228. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duzyj C, Barnea ER, Huang SJ, Krikun G, Paidas MJ. Preimplantation Factor Promotes First Trimester Trophoblast Migration. 30th Annual Meeting of the Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine; Chicago, Ill. Tracking ID 211741, poster presentation. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barnea ER, Shklyar B, Moskowitz A, Barnea JD, Sheth K, Rose FV. Expression of quinone reductase activity in embryonal and adult porcine tissues. Biol Reprod. 1995 Feb;52(2):433–7. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod52.2.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanyal MK, Li YL, Biggers WJ, Satish J, Barnea ER. Augmentation of polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbon metabolism of human placental tissues of first-trimester pregnancy by cigarette smoke exposure. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993 May;168(5):1587–97. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(11)90803-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barnea ER. Applying Embryo-Derived Immune Tolerance to the Treatment of Immune Disorders: Role of PIF. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2007;1110:602–18. doi: 10.1196/annals.1423.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chandy KG, Gutman GA, Grissmer S. Physiological Role, molecular structure and evolutionary relationships of voltage-gated potassium channels in T lymphocytes. Seminars in The Neurosciences. 1993;5:125–134. [Google Scholar]

- 43.von Rango U, Classen-Linke I, Raven G, Bocken F, Beier HM. Cytokine microenvironments in human first trimester decidua are dependent on trophoblast cells. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:1176–86. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)04829-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.von Rango U, Krusche CA, Beier HM, Classen-Linke I. J Indoleamine-dioxygenase is expressed in human decidua at the time maternal tolerance is established. Reprod Immunol. 2007;74:34–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2006.11.001. Epub 2007 Feb 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chelsea J, Stoikos CA, Harrison A, Salamonsen LA, Dimitriadis EA. Distinct cohort of the TGFb superfamily members expressed in human endometrium regulate decidualization. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:1447–1456. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dimitriadis E, Stoikos C, Tan YL, Salamonsen LA. Interleukin 11 Signaling Components Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 (STAT3) and Suppressor of Cytokine Signaling 3 (SOCS3) Regulate Human Endometrial Stromal Cell Differentiation Endocrinol. 2006;147:3809–3817. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lea RG, Tulpulla M, Critchley HOD. Deficient syncytiotrophoblast TNF characterizes first trimester pregnancy in a subgroup of recurrent miscarriage patients. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:1313–20. doi: 10.1093/humrep/12.6.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]