Abstract

Retroviral particles assemble a few thousand units of the Gag polyproteins. Proteolytic cleavage mediated by the retroviral protease forms the bioactive retroviral protein subunits before cell entry. We hypothesized that this process could be exploited for targeted, transient, and dose-controlled transduction of nonretroviral proteins into cultured cells. We demonstrate that gammaretroviral particles tolerate the incorporation of foreign protein at several positions of their Gag or Gag-Pol precursors. Receptor-mediated and thus potentially cell-specific uptake of engineered particles occurred within minutes after cell contact. Dose and kinetics of nonretroviral protein delivery were dependent upon the location within the polyprotein precursor. Proteins containing nuclear localization signals were incorporated into retroviral particles, and the proteins of interest were released from the precursor by the retroviral protease, recognizing engineered target sites. In contrast to integration-defective lentiviral vectors, protein transduction by retroviral polyprotein precursors was completely transient, as protein transducing retrovirus-like particles could be produced that did not transduce genes into target cells. Alternatively, bifunctional protein-delivering particle preparations were generated that maintained their ability to serve as vectors for retroviral transgenes. We show the potential of this approach for targeted genome engineering of induced pluripotent stem cells by delivering the site-specific DNA recombinase, Flp. Protein transduction of Flp after proteolytic release from the matrix position of Gag allowed excision of a lentivirally transduced cassette that concomitantly expresses the canonical reprogramming transcription factors (Oct4, Klf4, Sox2, c-Myc) and a fluorescent marker gene, thus generating induced pluripotent stem cells that are free of lentivirally transduced reprogramming genes.

Keywords: Flp recombinase, murine leukemia virus, pluripotent cells, protein transfer

Developing approaches to cell-specific protein transduction is of substantial interest for advanced forms of cell engineering, including the formation and modification of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). Protein uptake can be achieved by fusion with so-called membrane penetrating peptides, such as those derived from the lentiviral accessory protein tat (1 –3) or the homeobox protein Antennapedia (4, 5). However, production and purification of recombinant proteins often require complex biochemical procedures and can be hampered by misfolding and trapping in producer cells. Furthermore, transduced proteins can be degraded in endosomes, and the targeting of defined cell subpopulations is hard to achieve with this approach. In contrast, retrovirus-like particles can easily be generated by transient transfection of common cell lines, enter target cells by receptor-mediated and potentially cell-specific uptake, avoid or escape endosomes in their cytoplasmic route, and thus offer substantial advantages for protein transduction if sufficient amounts of the protein of interest can be embedded, processed, and released (6).

Retroviral particles assemble by associating a few thousand Gag-precursor polyproteins, which accumulate at the cytoplasmic side of the cell membrane through myristoylation of the N-terminal matrix (MA) protein. The subunits capsid (CA) and nucleocapsid (NC), and in murine leukemia virus (MLV) also p12, complete the Gag polyprotein. Through various mechanisms, retroviruses express about 5% of Gag as an extended Gag-Pol polyprotein. In the case of the simply organized gammaretroviruses, such as MLV, Pol is composed of a protease (PR), reverse transcriptase (RT), and integrase (IN).

Infectious retroviral particles are formed by proteolytic maturation after budding from the cytoplasmic membrane (7). PR initiates maturation by releasing itself from the polyprotein and then processes further protease sites both in cis, on the same polyprotein, and in trans, on other polyproteins of the particle. These maturation steps allow the protein subunits (schema in Fig. 1A) to play their distinct roles in the retroviral life cycle. A subset of these proteins forms the reverse transcriptase complex and the preintegration complex to eventually integrate the retroviral genomic DNA into cellular chromosomes (8, 9). Here, we tested whether the assembly of polyprotein precursors into infectious particles with the subsequent protease-dependent processing and release of Gag subunits allows the targeted, transient and dose-controlled delivery of bioactive proteins into cultured cells, including iPSCs.

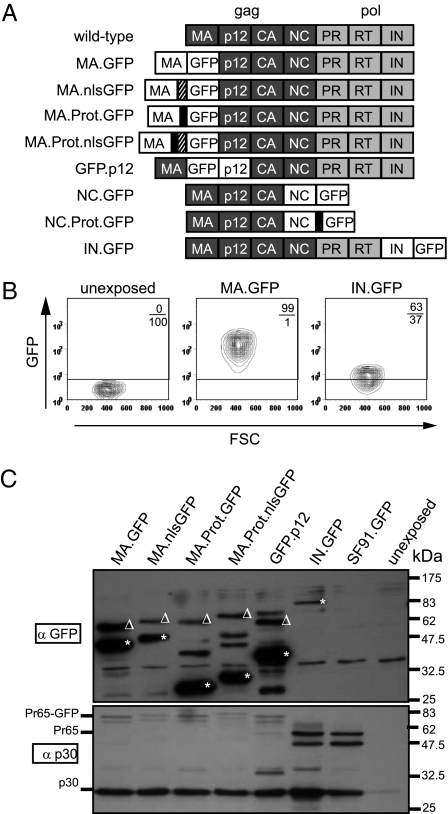

Fig. 1.

GFP embedded in the retroviral Gag-Pol polyprotein is tolerated, processed and delivered into target cells. (A) Schema of MLV Gag-Pol variants with protein subunits matrix (MA), p12, capsid (CA), nucleocapsid (NC), protease (PR), reverse transcriptase (RT), integrase (IN). GFP was incorporated in various Gag-Pol positions: C-terminal of MA (MA.GFP and derivatives), N-terminal of p12 (GFP.p12), and C-terminal of IN (IN.GFP). The MA position was also tested with a nuclear localization signal (hatched box, MA.nlsGFP), and an additional protease site (RSSLY/PALTP; black box, MA.Prot.GFP and MA.Prot.nlsGFP). GFP was also inserted C-terminal of NC replacing Pol with or without maintaining the natural protease site (QTSLL/TLDD) (NC.Prot.GFP or NC.GFP, respectively). (B) GFP transfer to SC1 fibroblasts by ecotropic particle preparations made with either MA.GFP or IN.GFP in the absence of WT Gag-Pol. FACS analysis 5 h posttransduction with 400 μL unconcentrated supernatants, indicating the percentage of GFP+ cells and fluorescence intensity. (C) Proteolytic maturation in HT1080mCAT cells 1.5 h posttransduction with concentrated ecotropic particles (lacking WT Gag-Pol). Supernatant of an integrating GFP vector (SF91.GFP) packaged with WT Gag-Pol served as control; polyclonal anti-GFP antibody (Upper). Asterisks represent processed products (Left to Right): MA.GFP, MA.nlsGFP, GFP, nlsGFP, GFP.p12, IN.GFP. Triangles represent associated unprocessed precursors (Pr). CA (p30) was detected with a polyclonal anti-Capsid (anti-p30) antibody and served as loading control (Lower). Sizes for Pr65-GFP, Pr65 (Gag precursor), and p30 (CA) are indicated.

Results

Embedding and Processing of Foreign Proteins in the Gag-Pol Polyprotein.

The expression constructs used in this study were based on Gag-Pol of Moloney MLV, encoding the Gag subunits MA, p12, CA, and NC (Fig. 1A). The enhanced GFP was inserted into the C-terminus of MA (MA.GFP), N-terminus of p12 (GFP.p12), as well as the C-terminus of NC (NC.GFP) or IN (IN.GFP). We also developed polyproteins with a protease cleavage site N-terminal of GFP, MA.Prot.GFP (with a second motif of the MA/p12 cleavage motif) and NC.Prot.GFP (with the NC/PR site). In the MA C-terminus, we introduced GFP with a nuclear localization signal (nls), with (MA.Prot.nlsGFP) or without (MA.nlsGFP) the protease site. To assess the preservation of Gag and Pol functions, the constructs were tested in a three-plasmid split gammaretroviral packaging system (10, 11). Constructs lacking Pol (NC.GFP, NC.Prot.GFP) were cotransfected (1:1 ratio) with WT Gag-Pol to provide the protease encoded by Pol. The integrating retroviral gene vector (SF11tCD34) expressed truncated CD34 (tCD34) as a cell-surface marker (12).

Although all variants except IN.GFP exhibited reduced titers (Fig. S1A), integrating vectors still produced titers up to 105 particles per milliliter, underlining the flexibility of the gammaretroviral Gag-Pol to incorporate foreign protein. Particles were brightly fluorescent when GFP was incorporated into Gag. When transducing SC1 fibroblasts with unconcentrated ecotropic supernatant, the entire cell population was GFP-labeled within 5 h posttransduction (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1B). Fluorescence levels depended on the localization of GFP within Gag-Pol (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1 B and C), with IN.GFP mediating the weakest signal in target cells. However, although cells were extensively washed before analysis, flow cytometry cannot distinguish between surface-bound and internalized GFP.

Proteolytic processing of GFP and Gag in vector preparations (Fig. S1D) and 1.5 h posttransduction in human fibroblasts (HT1080mCAT cells expressing the ecotropic receptor) was analyzed by Western blot (Fig. 1C). The uncleaved precursor polyprotein and the processed subunits were found in all cases, demonstrating functionality of the engineered protease site upstream of GFP or nlsGFP. Proteolytic cleavage was incipient in supernatants and nearly complete in transduced cells, reflecting the retroviral maturation kinetics or a potential selection for fully processed virions.

Controls revealed that particles assembled on the basis of WT Gag-Pol did not transduce significant amounts of GFP protein (lane SF91.GFP in Fig. 1C) unless it was incorporated into the Gag-Pol reading frame. Furthermore, reverse transcription was not needed for GFP transfer into target cells, as shown by treatment with the nucleoside analog AZT (Fig. S1E). Protein delivery thus depended on the incorporation into and the location within the polyprotein precursor.

Kinetics of Protein Delivery and Subcellular Processing of Transduced Proteins.

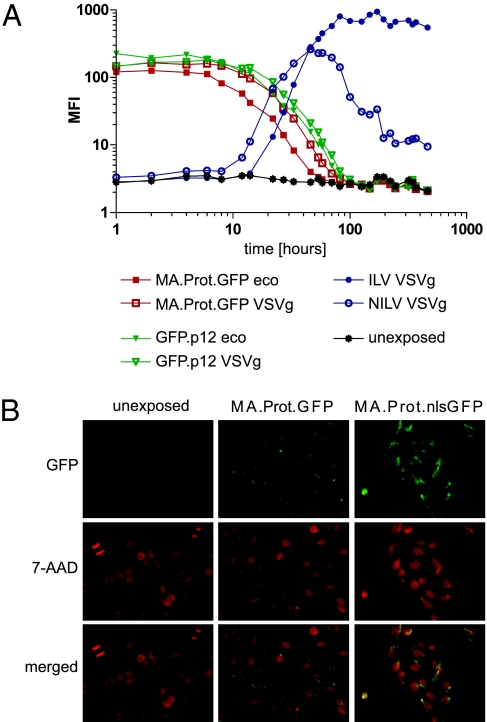

To investigate the kinetics of GFP delivery by modified Gag polyproteins, we studied HT1080mCAT cells over a period of 500 h (20 d) after exposure to concentrated ecotropic or VSVg pseudotyped particles. Mock-treated cells served as negative control, and integrating (ILV) or nonintegrating lentiviral vectors (NILV) expressing GFP from the strong spleen focus forming virus promoter served as reference values. MA.GFP expression rapidly accumulated to steady-state levels within 1 h posttransduction (Fig. S2). MA.Prot.GFP and GFP.p12 also showed rapid cellular association and stability until 6 h posttransduction (Fig. 2A), followed by a steady decline until 100 h with return to baseline autofluorescence. The decay of GFP fluorescence depended on its maximal expression level (compare GFP.p12 and MA.Prot.GFP), without major effects of the pseudotype (ecotropic or VSVg) or engineered protease motifs (Fig. 2A). The efficiency of GFP transfer by Gag polyproteins reached ≈10% of the level induced by expression from ILV and was comparable to the peak levels achieved with NILV. Interestingly, the transgene-dependent expression of GFP (ILV and NILV) started to accumulate beyond 10 h posttransduction, exactly when the polyprotein-mediated transduction began to decrease. Compared with the polyprotein-mediated delivery, NILV-transduced cells showed a much longer duration of expression (declining 50 h posttransduction) with persistence in a subset of cells, as described (13 –15). Thus, rapid onset and full reversion was only obtained with protein transduction.

Fig. 2.

Gag-Pol polyprotein mediated delivery of GFP is rapid, transient, and redirected by a nuclear localization signal. (A) HT1080mCAT cells were transduced with particles produced with MA.Prot.GFP (red) or GFP.p12 (green) in the absence of WT Gag-Pol. GFP-encoding integrating (ILV) and nonintegrating lentiviral vectors (NILV, packaged with a D64V integrase mutant) pseudotyped with VSVg (blue) served as controls [multiplicity of infection (MOI) 2 based on copackaged reporter genes tCD34 or GFP]. For GFP.p12, we used lower MOIs (0.8 ecotropic; 0.1 VSVg) because of low titers. Gag precursor-mediated delivery of GFP decreased to baseline of unexposed cells (black). (B) The intracytoplasmic distribution of transduced protein is affected by a nuclear localization signal. SC1 cells 4.5 h posttransduction with ecotropic MA.Prot.GFP or MA.Prot.nlsGFP particles (MOI 0.2), nuclei stained by 7-AAD. 400× magnification.

Delivery of Nuclear Localizing GFP from MA.Prot Modified Polyproteins.

We examined the intracellular localization of the transferred GFP by fluorescence microscopy, comparing constructs with a nuclear localization signal in GFP and an additional protease site C-terminal of MA (MA.Prot.GFP and MA.Prot.nlsGFP) (Fig. 1A). The protease site released GFP from MA (Fig. 1C), with microscopically visible signals primarily localized in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2B), whereas nlsGFP accumulated in the nucleus at 4.5 h posttransduction [7-Aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) stained red, showing partial signal overlay] (Fig. 2B). However, at later time points (6 and 9 h posttransduction) we predominantly observed accumulation of green fluorescence close to the nucleus (likely at the microtubule organizing center). As particle-associated GFP is brighter than freely diffusible molecules, microscopy may detect virions and derived complexes (16, 17) with a higher sensitivity than the potential nuclear translocation of free protein.

Delivery of Bioactive Flp Recombinase via Gag Polyproteins.

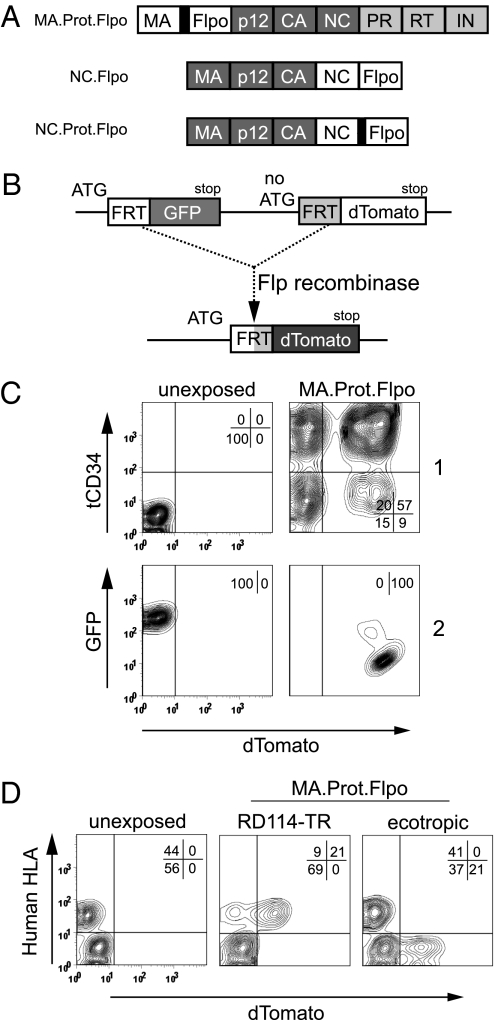

To directly demonstrate nuclear activity of the transduced protein, we generated constructs that deliver the yeast-derived Flp recombinase. A codon-optimized version (Flpo) (18) linked to an N-terminal protease site was incorporated between MA and p12 (MA.Prot.Flpo) or into the C-terminus of NC (NC.Prot.Flpo). Construct NC.Flpo lacked the protease site (Fig. 3A). VSVg pseudotyped particles were generated by cotransfecting WT Gag-Pol in a 1:1 ratio as a source of the protease, which is absent in constructs NC.Flpo and NC.Prot.Flpo. Particles were used to transduce SC1 cells containing an indicator allele, which converts from GFP to dTomato expression upon Flp recombination (Fig. 3B). Indeed, Flp protein delivery from Gag-polyprotein precursors induced dTomato in a strictly dose-dependent manner (Fig. S3A). Constructs MA.Prot.Flpo and NC.Prot.Flpo were more potent than NC.Flpo. Thus, retroviral particles with modified Gag precursors transduced a site-specific nuclear-active DNA recombinase, and the highest efficiency was obtained with an additional protease-site to release the protein of interest from Gag subunits.

Fig. 3.

Gag precursor-mediated Flp transduction does not require codelivery of retroviral genomes. (A) Codon-optimized Flp (Flpo) was fused C-terminal of MA with an additional MA/p12 protease site (MA.Prot.Flpo), or C-terminal of NC without (NC.Flpo), or with the natural protease site separating NC from PR (NC.Prot.Flpo). The NC constructs lacked Pol. In all Flp experiments, WT Gag-Pol was cotransfected for particle production. (B) Schema of the Flp-indicator cassette: GFP flanked by Flp recombinase target (FRT) sites followed by dTomato lacking the ATG start codon. FRT recombination switches expression from GFP to dTomato. (C) [Upper (1)] SF11tCD34 vector was cotransfected with VSVg and MA.Prot.Flpo. 5 × 104 Flp-indicator SC1 cells transduced with 400 μL unconcentrated supernatant. tCD34 expression detected by an APC-antibody was analyzed in relation to dTomato fluorescence 3d posttransduction. [Lower (2)] The same experiment devoid of SF11tCD34. GFP in relation to dTomato fluorescence. (D) Flp transduction from Gag precursors is receptor mediated. Mixed murine SC1 and human HT1080 cells carrying the Flp-indicator construct were transduced with unconcentrated MA.Prot.Flpo particles pseudotyped with RD114-TR (human specific) or the ecotropic envelope (murine specific). After 2 h the cells were washed and cultivated in virus-free medium before flow cytometry using anti-human HLA(A, B, C).

Combined Transduction of Nucleic Acids and Proteins.

To address the possibility of generating “bipotent” retroviral particle preparations capable of concomitantly transducing a gene of interest and delivering Flp, we packaged the retroviral vector SF11tCD34 in VSVg pseudotyped Flp-transducing particles, otherwise produced as described above. MA.Prot.Flpo mediated efficient genetic transduction (tCD34+, y axis) and Flp protein delivery (dTomato+, x axis), as detected by a high percentage of double-positive events (Fig. 3C) (57% dTomato+ cells expressing tCD34 vs. 9% lacking tCD34). In contrast, construct NC.Prot.Flpo preferentially transduced Flp in tCD34− cells (Fig. S3B). Construct NC.Flpo, which lacks the protease site, was most potent in transducing the integrating tCD34 vector but achieved the lowest recombination rate (26% dTomato+ cells) (Fig. S3B), indicating that the persisting fusion to NC impaired Flp activity or nuclear translocation.

Retrovirus-Like Particles Lacking Nucleic Acids Efficiently Transduce Flp.

Genomic mRNA containing the packaging signal is not required for gammaretroviral particle formation (19). To test whether transduction of Flp via the Gag polyprotein would also be feasible in the absence of vector mRNA, we produced particles as above but without a retroviral genomic mRNA. Construct MA.Prot.Flpo generated the most potent particles: a single exposure to 400 μL unconcentrated supernatant led to complete induction of red fluorescence in indicator cells (Fig. 3C and Fig. S4). This result is even more remarkable, as Southern blot analysis revealed that the indicator clone contains three copies of the Flp recombinase target (FRT)-transgene (Fig. S5A). We confirmed the dose-dependent loss of the different FRT-flanked GFP cassettes by Southern blot and PCR analyses (Fig. S5). These data, together with those obtained upon addition of the RT-inhibitor AZT (Fig. S1E), demonstrate that retroviral nucleic acids or reverse transcription are not required for Gag-mediated protein transduction.

Targeting of Protein Transduction by Virtue of Envelope Properties.

To test the receptor dependence, we produced MA.Prot.Flpo particles lacking envelope proteins and were unable to observe recombination in target cells. Next, we produced these particles with murine ecotropic or RD114-TR envelopes (20). Although the former does not transduce human cells, the latter does, but is severely restricted in murine cells. Mixed monolayer cultures of murine and human cells, both containing the Flp indicator cassette, were exposed to pseudotyped particles. Dose-escalation experiments with RD114-TR particles resulted in substantial cell fusions with subsequent toxicity, reflecting the known fusogenicity of this glycoprotein (21). Therefore, experiments were conducted with limited exposure time (2 h). RD114-TR particles exclusively converted human cells to red fluorescence, whereas ecotropic particles demonstrated their profound tropism for murine cells (Fig. 3D). These experiments revealed that the transduction of foreign proteins from engineered Gag precursors is mediated by envelope-dependent uptake of retroviral particles, allowing cell-specific targeting.

Gag-Pol Polyprotein Mediated Protein Transduction to Engineer iPSCs.

We used VSVg pseudotyped particles containing MA.Prot.GFP to examine the potential of Gag-mediated protein transduction in murine iPSCs (22). GFP expression increased in the entire cell population, although to a lesser extent than observed in SC1 cells (Fig. S6A). To validate these results, we generated iPSCs carrying the Flp-indicator cassette. As in fibroblasts, the MA variant was more potent than the NC location to release Flp in iPSCs (Fig. S6 B and C). Results were quantified by flow cytometry using a polyclonal population of iPSC, of which ∼50% were transduced and expressed the Flp-indicator construct. MA.Prot.Flpo was the most potent variant to release bioactive Flp: > 75% of the initial GFP+ iPSCs lost GFP and started to express dTomato after a single treatment (Fig. 4A). When transducing iPSC clones, Flp-mediated induction of dTomato was complete (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Modification of iPSCs by protein transduction of Flp. (A) 1 × 105 iPSCs containing the Flp-indicator construct (Fig. 3B) transduced with MA.Prot.Flpo or NC.Prot.Flpo particles (100 μL, concentrated, VSVg pseudotyped), FACS analysis 3 d posttransduction showing dTomato+ cells. (B) Experiment as in A transducing 7 × 104 clonal iPSCs with 30 μL of concentrated MA.Prot.Flpo supernatant. Fluorescence microscopy 3 d posttransduction. (100x magnification).

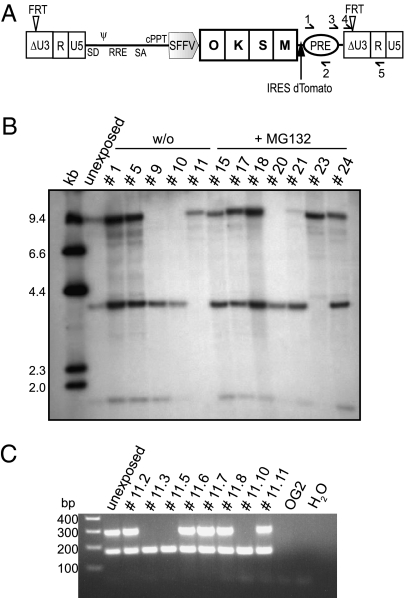

Finally, we tested the ability of the Flp particles to excise reprogramming cassettes from murine iPSC. To this end, we constructed and validated a lentiviral reprogramming vector containing an FRT-flanked expression cassette, which linked the four canonical reprogramming genes (22) to an IRES-dTomato fluorescence marker gene (Fig. 5A). As iPSCs generated with this vector silenced the reprogramming cassette including dTomato, we monitored excision of the reprogramming genes by quantitative PCR and Southern blot detecting the PRE sequence. In an iPSC clone containing three integrations of the FRT-flanked reprogramming vector (Fig. S7A), Gag-mediated protein transduction was as efficient as integrating retroviral vectors encoding Flp to excise the FRT-flanked cassette (Fig. S7B). Although treatment with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 did not further improve delivery of Flp, it indicated the reproducibility of the results (Fig. 5B and Fig. S7 B and C). Subclone analyses showed that all three lentiviral integrants were amenable to targeted recombination (Fig. 5B). Retreatment of a selected subclone (#11) led to the removal of all three vector insertions, as confirmed by a sensitive PCR (Fig. 5C and Fig. S7D). We thus showed the potential of Gag-mediated protein transduction to engineer iPSC without the need for additional transfer of nucleic acids.

Fig. 5.

Excision of a reprogramming cassette by Flp delivery from Gag precursors. (A) The lentiviral vector used for reprogramming mouse embryonic OG2 fibroblasts contained a cassette composed of the factors Oct4 (O), Klf4 (K), Sox2 (S), and c-Myc (M) separated by 2A cleavage sites, with FRT-sites in the ΔU3 region of the LTR. Primers detecting PRE (arrows 1 and 2) were used for qPCR. Primers detecting the LTR (arrows 3, 4, and 5) were used for semiquantitative PCR. (B) 5 × 104 murine iPSCs were transduced with 50 μL concentrated MA.Prot.Flpo particles ± 0.5 μM MG132. Twelve clones each were isolated and Southern blotting was accomplished on EcoRV-digested gDNA with PRE-specific probes. All three vector integrations were accessible to excision by Flp. In lane “unexposed” less gDNA was loaded; compare with Fig. S7A. (C) Next, 5 × 104 cells of clone #11 containing a single copy of the reprogramming vector as shown in B were transduced with 60 μL concentrated MA.Prot.Flpo particles. Eight subclones were analyzed by semiquantitative PCR using primers 3, 4, and 5 simultaneously. Primers 3 and 5 produce a 290-bp amplicon which cannot be obtained following Flp recombination of the vector. Primers 4 and 5 produce a 170-bp amplicon regardless of Flp recombination. OG2 fibroblasts and H2O served as controls.

Discussion

This work introduces a unique concept of targeted and dose-controlled protein delivery for transient cell modification. Foreign proteins can be incorporated into various positions of the retroviral Gag polyprotein precursor, exported from producer cells in the form of retroviral “nanoparticles,” targeted to cells by the interaction of the retroviral envelope with its potentially cell-specific receptor, released from the polyprotein by the retroviral protease and intracellular disassembly steps, and thus allowed to find their molecular targets in transduced cells. Removal of lentiviral reprogramming cassettes from iPSCs following delivery of the recombinase Flp demonstrated the potency of this approach.

Recombinases such as Flp and Cre mediate sequence-specific excision or cassette exchange of transgenes flanked by the corresponding recognition sites (23, 24). Ectopic and continued expression of recombinases may be immunogenic, impair cassette exchange, and induce genotoxic off-target events (25). DNA-based approaches for delivery of recombinases, such as those relying on adenoviral vectors (26) or transient transfection (27), are popular but cannot avoid the risk of residual transgene integration. Transfection of mRNA (28, 29) and the transduction of membrane-permeable recombinant protein (1 –4) lead to transient but rather variable expression. In contrast, Gag-mediated protein transduction mediates predictable and transient protein delivery, and may be combined with recently described measles envelope variants for antibody-mediated cell targeting (30, 31).

Dozens to a few hundred retroviral particles may enter a cell. The incorporation of heterologous proteins into Gag introduces ∼3,000 to 5,000 units per viral particle, and tolerates the introduction of additional protease sites to release the protein of interest in target cells. Other retroviral proteins, such as Vpr or Integrase, have not been modified with additional protease sites and are packaged to a lesser degree (∼100–200 Pol molecules or 18 to a few hundred lentiviral Vpr molecules) (32 –35). Gag-mediated protein transduction coupled with protease-mediated release may thus be the most efficient and “cleanest” way of retroviral protein delivery.

We show that modified MLV particles tolerate foreign sequences in the N-terminus of p12 and the C-termini of MA and NC, partly confirming earlier studies (36, 37). Although cleavage between MA and p12 is not critical for the maturation of MLV, cleavage of p12/CA and CA/NC is essential for normal core structure and RNA dimer stabilization, respectively (7). CA is not tolerant to large insertions, probably because of its “cage”-like structure. The constructs MA.GFP, GFP.p12, NC.GFP, and IN.GFP may serve as tools for virus trafficking studies (38 –46). Further work will have to address whether the localization within the virus particle influences the release kinetics of free protein.

Furthermore, our results indicate that retroviral particle preparations, which deliver foreign proteins from Gag, have the capacity to codeliver retroviral RNA genomes. As envelope proteins can be modified to deliver cytokine signals (47), it may be possible to engineer cells using multifunctional retroviral particle preparations, which elicit a cascade of immediate, transient, and permanent effects (48). Underlining the versatility of this concept, intermediate steps of the retroviral life cycle can be exploited to deliver episomal DNA (14, 15, 49) or mRNA (13, 50).

A proof-of-principle achieved in this report was the targeted genetic recombination of iPSCs by Gag-mediated transduction of Flp recombinase. We excised integrated and epigenetically silenced lentiviral reprogramming vectors to exclude their potential reactivation, thus reducing the risks of inhibited differentiation and teratoma formation (51, 52). It may be interesting to explore whether Gag-mediated protein transduction allows the induction of reprogramming or differentiation by the transient delivery of transcription factors.

Materials and Methods

Plasmid Construction.

To construct a modular system for incorporation of heterologous sequences into MLV gag-pol, we used PCR-based approaches to introduce unique restriction sites, thus facilitating the cloning of our genes of interest. See details in SI Materials and Methods.

Cell Lines and Production of Viral Supernatants.

Human embryonic kidney cells 293T, human fibroblasts HT1080 and HT1080mCAT (HT1080 cells expressing the murine ecotropic receptor mCAT), and murine fibroblasts SC1 were cultured in DMEM supplemented with glutamine (Biochrom), 10% FCS, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 1 mM sodium pyruvate (all PAA). Retroviral supernatants were produced after transient transfection of 293T cells as previously described, using ecotropic, VSVg, or RD114-TR envelopes (10, 53). Particles for delivery of GFP from MA, p12, or IN were produced using 7 μg plasmid, and from NC using 3.5 μg plasmid mixed 1:1 with WT Gag-Pol plasmid. Particles delivering Flp from the MA and NC position were produced with 3.5 μg engineered Gag-Pol mixed 1:1 with WT Gag-Pol. Some of the ecotropic or VSVg pseudotyped supernatants were concentrated by ultracentrifugation (Beckman Coulter, Optima LE-80K) at 12,300 × g and 4 °C overnight with (Figs. 1C, 2 A, and 4A , and Figs. S1 D and E, S2, and S6A) or without a 20% sucrose cushion. Cells were transduced as indicated in SI Materials and Methods. Murine iPSCs were cultured and transduced as indicated in SI Materials and Methods.

Flow Cytometry, Fluorescence Microscopy, and Western Blot.

Please refer to SI Materials and Methods.

Southern Blot.

gDNA was isolated from cells using QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen). Southern blots were performed according to standard protocols, after digesting 10 μg of gDNA with appropriate restriction enzymes. eGFP (for SC1 Flp-indicator cells) or wPRE (for iPSCs) DNA probes were radioactively labeled and hybridized.

Semiquantitative PCR.

For semiquantitative PCR, 400 ng of gDNA from SC1 Flp-indicator cells were used for amplification of the indicator cassette (Primer forward: ATTTGAATTAACCAATCAGCCTG; reverse: GCAACCAGGATTTATACAAGG) using Taq polymerase (Qiagen). PCR of iPSC gDNA (300 ng) to detect excision of the 4-in-1 reprogramming cassette was performed using three primers simultaneously (Primer 3 forward: CGAGTCGGATCTCCCTTTGGGC, Primer 4 forward: TGGAAGGGCTACGTAGCTAGC, Primer 5 reverse: GGTTCCCTAGTTAGCCAGAGAGC) (Fig. 5A).

Quantitative PCR.

Quantitative PCR amplifying wPRE (Primer 1 forward: GAGGAGTTGTGGCCCGTTGT, Primer 2 reverse: TGACAGGTGGTGGCAATGCC) (Fig. 5A) and GFP (Primer forward: CTATATCATGGCCGACAAGCAGA, reverse: GGACTGGGTGCTCAGGTAGTGG) was performed on a StepOnePlus Realtime PCR System (Applied Biosystems) according to standard protocols, using QuantiTect SYBR Green (Qiagen) and 50 ng of genomic DNA.

Statistical Analysis.

Data from experiments are expressed as mean ± SEM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Hans Schöler (Münster, Germany), Thomas Müller, Cornelia Kasper, and Thomas Scheper (Hannover, Germany) for help with induced pluripotent stem cells work; Maimona Id, Diana Szepe, Girmay Asgedom, Ivonne Fernandez, and Valerie Mordhorst for technical assistance; and Michael Morgan for critically reading the manuscript. This work was supported by grants of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft [SFB738 and cluster of excellence REBIRTH (Exc 62/1)] and the European Union (FP7 project PERSIST, HEALTH-F5-2009-222878).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. S.H.H. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0914517107/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Gump JM, Dowdy SF. TAT transduction: The molecular mechanism and therapeutic prospects. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:443–448. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwarze SR, Ho A, Vocero-Akbani A, Dowdy SF. In vivo protein transduction: Delivery of a biologically active protein into the mouse. Science. 1999;285:1569–1572. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5433.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris MC, Depollier J, Mery J, Heitz F, Divita G. A peptide carrier for the delivery of biologically active proteins into mammalian cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:1173–1176. doi: 10.1038/nbt1201-1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ford KG, Souberbielle BE, Darling D, Farzaneh F. Protein transduction: An alternative to genetic intervention? Gene Ther. 2001;8:1–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Derossi D, Joliot AH, Chassaing G, Prochiantz A. The third helix of the Antennapedia homeodomain translocates through biological membranes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10444–10450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dalba C, Bellier B, Kasahara N, Klatzmann D. Replication-competent vectors and empty virus-like particles: New retroviral vector designs for cancer gene therapy or vaccines. Mol Ther. 2007;15:457–466. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oshima M, et al. Effects of blocking individual maturation cleavages in murine leukemia virus gag. J Virol. 2004;78:1411–1420. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.3.1411-1420.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goff SP. Genetics of retroviral integration. Annu Rev Genet. 1992;26:527–544. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.26.120192.002523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowerman B, Brown PO, Bishop JM, Varmus HE. A nucleoprotein complex mediates the integration of retroviral DNA. Genes Dev. 1989;3:469–478. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.4.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schambach A, et al. Equal potency of gammaretroviral and lentiviral SIN vectors for expression of O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase in hematopoietic cells. Mol Ther. 2006;13:391–400. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schambach A, et al. Overcoming promoter competition in packaging cells improves production of self-inactivating retroviral vectors. Gene Ther. 2006;13:1524–1533. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fehse B, et al. CD34 splice variant: An attractive marker for selection of gene-modified cells. Mol Ther. 2000;1:448–456. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galla M, Schambach A, Towers GJ, Baum C. Cellular restriction of retrovirus particle-mediated mRNA transfer. J Virol. 2008;82:3069–3077. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01880-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nightingale SJ, et al. Transient gene expression by nonintegrating lentiviral vectors. Mol Ther. 2006;13:1121–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yáñez-Muñoz RJ, et al. Effective gene therapy with nonintegrating lentiviral vectors. Nat Med. 2006;12:348–353. doi: 10.1038/nm1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lehmann-Che J, et al. Centrosomal latency of incoming foamy viruses in resting cells. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e74. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zamborlini A, et al. Centrosomal pre-integration latency of HIV-1 in quiescent cells. Retrovirology. 2007;4:63. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-4-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raymond CS, Soriano P. High-efficiency FLP and PhiC31 site-specific recombination in mammalian cells. PLoS One. 2007;2:e162. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rulli SJ, Jr., et al. Selective and nonselective packaging of cellular RNAs in retrovirus particles. J Virol. 2007;81:6623–6631. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02833-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sandrin V, et al. Lentiviral vectors pseudotyped with a modified RD114 envelope glycoprotein show increased stability in sera and augmented transduction of primary lymphocytes and CD34+ cells derived from human and nonhuman primates. Blood. 2002;100:823–832. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-11-0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Germain E, Roullin VG, Qiao J, de Campos Lima PO, Caruso M. RD114-pseudotyped retroviral vectors kill cancer cells by syncytium formation and enhance the cytotoxic effect of the TK/GCV gene therapy strategy. J Gene Med. 2005;7:389–397. doi: 10.1002/jgm.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qiao J, Oumard A, Wegloehner W, Bode J. Novel tag-and-exchange (RMCE) strategies generate master cell clones with predictable and stable transgene expression properties. J Mol Biol. 2009;390:579–594. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oumard A, Qiao J, Jostock T, Li J, Bode J. Recommended method for chromosome exploitation: RMCE-based cassette-exchange systems in animal cell biotechnology. Cytotechnology. 2006;50:93–108. doi: 10.1007/s10616-006-6550-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higashi AY, et al. Direct hematological toxicity and illegitimate chromosomal recombination caused by the systemic activation of CreERT2. J Immunol. 2009;182:5633–5640. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anton M, Graham FL. Site-specific recombination mediated by an adenovirus vector expressing the Cre recombinase protein: A molecular switch for control of gene expression. J Virol. 1995;69:4600–4606. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.4600-4606.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soldner F, et al. Parkinson's disease patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells free of viral reprogramming factors. Cell. 2009;136:964–977. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilboa E, Vieweg J. Cancer immunotherapy with mRNA-transfected dendritic cells. Immunol Rev. 2004;199:251–263. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Tendeloo VF, Ponsaerts P, Berneman ZN. mRNA-based gene transfer as a tool for gene and cell therapy. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2007;9:423–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buchholz CJ, Mühlebach MD, Cichutek K. Lentiviral vectors with measles virus glycoproteins—dream team for gene transfer? Trends Biotechnol. 2009;27:259–265. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frecha C, et al. Stable transduction of quiescent T-cells without induction of cycle progression by a novel lentiviral vector pseudotyped with measles virus glycoproteins. Blood. 2008;112:4843–4852. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-155945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh SP, et al. Epitope-tagging approach to determine the stoichiometry of the structural and nonstructural proteins in the virus particles: Amount of Vpr in relation to Gag in HIV-1. Virology. 2000;268:364–371. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Link N, et al. Therapeutic protein transduction of mammalian cells and mice by nucleic acid-free lentiviral nanoparticles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:e16. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnj014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schenkwein D, et al. Production of HIV-1 integrase fusion protein containing lentivirus vectors for gene therapy and protein transduction. Hum Gene Ther. 2009 doi: 10.1089/hum.2009.051. online December 29, 2009, ahead of print, PMID: 20039782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cavrois M, De Noronha C, Greene WC. A sensitive and specific enzyme-based assay detecting HIV-1 virion fusion in primary T lymphocytes. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:1151–1154. doi: 10.1038/nbt745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Auerbach MR, Shu C, Kaplan A, Singh IR. Functional characterization of a portion of the Moloney murine leukemia virus gag gene by genetic footprinting. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:11678–11683. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2034020100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Puglia J, et al. Revealing domain structure through linker-scanning analysis of the murine leukemia virus (MuLV) RNase H and MuLV and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase proteins. J Virol. 2006;80:9497–9510. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00856-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sherer NM, et al. Visualization of retroviral replication in living cells reveals budding into multivesicular bodies. Traffic. 2003;4:785–801. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2003.00135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lampe M, et al. Double-labelled HIV-1 particles for study of virus-cell interaction. Virology. 2007;360:92–104. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Müller B, et al. Construction and characterization of a fluorescently labeled infectious human immunodeficiency virus type 1 derivative. J Virol. 2004;78:10803–10813. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.19.10803-10813.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Andrawiss M, Takeuchi Y, Hewlett L, Collins M. Murine leukemia virus particle assembly quantitated by fluorescence microscopy: Role of Gag-Gag interactions and membrane association. J Virol. 2003;77:11651–11660. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.21.11651-11660.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perrin-Tricaud C, Davoust J, Jones IM. Tagging the human immunodeficiency virus gag protein with green fluorescent protein. Minimal evidence for colocalisation with actin. Virology. 1999;255:20–25. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Larson DR, Johnson MC, Webb WW, Vogt VM. Visualization of retrovirus budding with correlated light and electron microscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15453–15458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504812102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hübner W, et al. Sequence of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) Gag localization and oligomerization monitored with live confocal imaging of a replication-competent, fluorescently tagged HIV-1. J Virol. 2007;81:12596–12607. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01088-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McDonald D, et al. Visualization of the intracellular behavior of HIV in living cells. J Cell Biol. 2002;159:441–452. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200203150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Campbell EM, Perez O, Melar M, Hope TJ. Labeling HIV-1 virions with two fluorescent proteins allows identification of virions that have productively entered the target cell. Virology. 2007;360:286–293. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Verhoeyen E, et al. Novel lentiviral vectors displaying “early-acting cytokines” selectively promote survival and transduction of NOD/SCID repopulating human hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2005;106:3386–3395. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baum C, Schambach A, Bohne J, Galla M. Retrovirus vectors: Toward the plentivirus? Mol Ther. 2006;13:1050–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vargas J, Jr, Gusella GL, Najfeld V, Klotman ME, Cara A. Novel integrase-defective lentiviral episomal vectors for gene transfer. Hum Gene Ther. 2004;15:361–372. doi: 10.1089/104303404322959515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Galla M, Will E, Kraunus J, Chen L, Baum C. Retroviral pseudotransduction for targeted cell manipulation. Mol Cell. 2004;16:309–315. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miura K, et al. Variation in the safety of induced pluripotent stem cell lines. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:743–745. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sommer CA, et al. Excision of reprogramming transgenes improves the differentiation potential of iPS cells generated with a single excisable vector. Stem Cells. 2010;28:64–74. doi: 10.1002/stem.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schambach A, et al. Lentiviral vectors pseudotyped with murine ecotropic envelope: Increased biosafety and convenience in preclinical research. Exp Hematol. 2006;34:588–592. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.