Abstract

Background

Although the incidence of the use of life-ending drugs without explicit patient request has been estimated in several studies, in-depth empirical research on this controversial practice is nonexistent. Based on face-to-face interviews with the clinicians involved in cases where patients died following such a decision in general practice in Belgium, we investigated the clinical characteristics of the patients, the decision-making process, and the way the practice was conducted.

Methods

Mortality follow-back study in 2005-2006 using the nationwide Sentinel Network of General Practitioners, a surveillance instrument representative of all GPs in Belgium. Standardised face-to-face interviews were conducted with all GPs who reported a non-sudden death in their practice, at home or in a care home, which was preceded by the use of a drug prescribed, supplied or administered by a physican without an explicit patient request.

Results

Of the 2690 deaths registered by the GPs, 17 were eligible to be included in the study. Thirteen interviews were conducted. GPs indicated that at the time of the decision all patients were without prospect of improvement, with persistent and unbearable suffering to a (very) high degree in nine cases. Twelve patients were judged to lack the competence to make decisions. GPs were unaware of their patient's end-of-life wishes in nine cases, but always discussed the practice with other caregivers and/or the patient's relatives. All but one patient received opioids to hasten death. All GPs believed that end-of-life quality had been "improved considerably".

Conclusions

The practice of using life-ending drugs without explicit patient request in general practice in Belgium mainly involves non-competent patients experiencing persistent and unbearable suffering whose end-of-life wishes can no longer be ascertained. GPs do not act as isolated decision-makers and they believe they act in the best interests of the patient. Advance care planning could help to inform GPs about patients' wishes prior to their loss of competence.

Background

Studies in several European countries have consistently reported that a number of patients die following end-of-life decisions which may, or are intended to, shorten life. The use of drugs by physicians with the intention of ending a patient's life without his or her explicit request is a practice that has evoked considerable political, ethical and public debate [1-3]. Although legally prohibited all over the world, this practice seems to take place everywhere in modern healthcare, albeit with differences between countries. Incidence estimates within Europe range between 0.06% and 1.50% of all deaths with the highest prevalence being reported in Flanders, Belgium [4-6].

However, despite extensive debate about this practice little is known about its conduct. In Belgium, for instance, it is performed relatively more often among those younger than 80, and those who were judged cognitively incompetent [7-10], and occurs in the home and care home setting under the care of the general practitioner (GP) in about half of all cases in 2001 [9,11,12].

In order to get a comprehensive picture of the last phase of life in these cases, it is indispensable to gain additional insight into the clinical characteristics of the patients, the decision-making process and the performance of the practice. Setting-specific information is also valuable because GP-patient relationships formed over a long period can differ notably from specialist-patient relationships which are often short-term and take place in acute circumstances [13].

This study will focus on the use of life-ending drugs by GPs without explicit patient request, to gain insights into how, why and for which patients GPs decide to end a life in this manner.

Our research questions are:

1. What are the socio-demographical and clinical characteristics of patients dying following the use of life-ending drugs without explicit patient request in general practice in Belgium?

2. Was the decision discussed with patients, family and/or other professional caregivers?

3. Were other end-of-life decisions made and did they precede, follow or take place jointly with the decision to use life-ending drugs?

4. How was the practice performed?

Methods

Study design, setting and participants

In 2005 and 2006, a large-scale mortality follow-back study was conducted to monitor end-of-life care and decision-making in Belgium using the Sentinel Network of General Practitioners (SENTI-MELC) study [14]. It involved a quantitative registration study of deaths in the practices of GPs within the Belgian Sentinel Network which, since it was founded in 1979, has proved to be a reliable surveillance system for a wide variety of health-related epidemiological data [14-18] and which is representative of all Belgian GPs in terms of age, sex and region [18,19]. The study resulted in a robust representative sample of non-sudden deaths (n = 1690) [10] not restricted to a specific setting, age group or disease. The study protocol and the first set of results are published elsewhere [10,14,20-22].

During this registration study, we identified deceased patients meeting the following inclusion criteria:

- aged one year or older at time of death

- death did not occur "suddenly or totally unexpectedly" as judged by the GP

- death occurred at home or in a care home

Based on these criteria 225 such patients were identified and a large interview study involving them was performed.

For the current study, patients were included if the GP registered that, in addition:

- death followed the use of 'a drug prescribed, supplied or administered by the GP or a colleague physician with the explicit intention of hastening the end of life'

- the decision concerning this act was made without an explicit request from the patient.

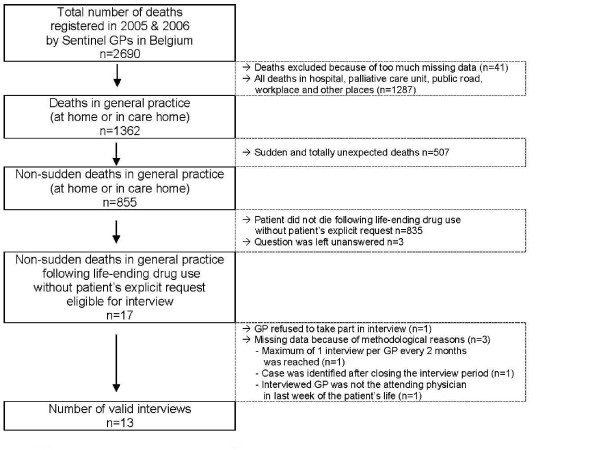

For 17 (1.3%) out of 1362 patients who died at home or in a care home in Belgium (Figure 1), life-ending drugs without explicit patient request preceded death (binomial 95% CI, exact method: [0.7-2.0]), which is 2.0% of all patients who died in these settings non-suddenly (binomial 95% CI, exact method: [1.2-3.2]). In four cases which met the criteria for inclusion interviews did not take place; in only one of these was the GP unwilling to participate. In total thirteen interviews were conducted.

Figure 1.

Process of interview inclusion.

Measurements

The interview with each GP was face-to-face and semi-structured and included both closed-ended and open-ended questions. Answers to open-ended questions were written down verbatim. For all questions, there was room to note additional information given by the GP.

Interview questions were based largely on existing questionnaires [1,23-28] (see Table 1 for all interview topics). Information about each patient's socio-demographics such as age at death, sex, level of education, and place of death was retrieved from the SENTI-MELC registration study.

Table 1.

Interview topics assessed in this study

| Questions on the patient's clinical and care characteristics during the last phase of life, assessing: |

|---|

| patient's main diagnosis [28] |

| other diseases for which the patient received treatment during the last three months of life [25-27] |

| patient's level of consciousness during the last week of life (not unconscious; unconscious one or more hours before death; unconscious one or more days before death; unconscious during whole week) [25-27] |

| time before death patient had started feeling ill and time before death patient was diagnosed [25-27] |

| number of GP contacts with the patient or with family regarding the patient during the last 3 months of life |

| the involvement of informal caregivers and/or clinical specialist in providing care for this patient during the last 3 months of life |

| symptom burden in the last week of life using an adapted version of the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale Global Distress Index (MSAS-GDI) [23] |

| functional status during the last three months of life using the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status Scale (ECOG) [24] |

| whether or not multidisciplinary palliative care services were involved |

| whether or not curative, life-prolonging or alternative palliative treatments could be considered that were not applied, and what the reasons were for not applying them [46] |

| to what extent the patient's suffering was persistent and unbearable and how GPs came to their judgment [46] |

| to what extent physical and/or psychological suffering was present that could not be alleviated [46] |

| to what extent the patient's medical situation was without prospect of improvement [46] |

| Questions on the process of the decision-making, assessing [1,3,4,6,25-27,47]: |

| The content and timing of the decision-making process: |

| whether or not the hastening of death was discussed with the patient (and reason for not discussing) |

| whether or not the patient was competent to make decisions (and reasons for incompetence) |

| wishes expressed by the patient concerning the termination of life, prior to the decision-making |

| involvement in the decision-making of patient's relatives, and other caregivers |

| time before death the decision was made and |

| GP's main considerations for doing so |

| Whether or not three other types of medical end-of-life decisions were made at the end of the patient's life and their sequence in time in relation to the decision to end life without explicit patient request: |

| (1) non-treatment decisions taking into account a possible hastening of death or with the explicit intent to hasten death |

| (2) intensifying alleviation of pain or other symptoms taking into account or co-intending the hastening of death |

| (3) using drugs to continuously sedate the patient until death |

| Questions on the performance of the practice, assessing [3,4]: |

| moment of drug administration and the circumstances surrounding death |

| drugs used to end life, time between administration of life-ending drugs and coma, and death |

| persons involved in the drug administration and GP's presence during the period until death |

| estimated life shortening effect of the drugs |

Procedure

In the SENTI-MELC registration study GPs registered deaths weekly, using a standardised form [14]. Every two months, the registration forms were screened for interview inclusion criteria. The GPs in cases meeting these criteria were contacted by telephone by an independent person to request their participation in a face-to-face interview. The interview took place at a time and place of the GP's choice. Each interview was undertaken by two researchers, one conducting the interview; the other making detailed notes of the interviewees' responses.

Strict procedures were used to preserve patient anonymity and physician confidentiality. Patient names were never identifiable to the interviewers or to other members of the research group: GPs used anonymous codes to refer to their patients in the registration form and the interviewers were given closed envelopes (prepared by the independent telephone operator) to give to the GP before each interview to make sure they referred to the correct patient. After closing the interview study, the GP's identity was permanently deleted from all files. The Ethical Review Board of Brussels University Hospital approved the study protocol.

Several procedures were used to ensure data quality and prevent missing data. If the question to identify patients who died following a life-ending act without explicit request was left unanswered on the registration form, a follow-up letter was sent to the GP. Also, to preclude overburdening the GP, each had no more than one interview per two months and the length of an interview was estimated at a maximum of one hour. In order to prevent recall bias, the interview was arranged as soon as possible after inclusion. Data-entry was done with consistency, range and skip checks, and the data were entered twice.

Analyses

All closed-ended questions were descriptively analyzed using SPSS 16.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill). Results of the study are presented both on an aggregate and on an individual case level. Both answers to open-ended questions and to questions for which additional information was provided by the GPs were encoded into categories by two researchers and/or registered as quotes.

Results

Table 2 and Additional file 1, Table S1 give an overview of the socio-demographic, care and clinical characteristics of patients dying following life-ending drug use without their explicit request. Of all thirteen patients three were aged 65 or younger at the time of death, eight died at home and five in the care home. Six out of the thirteen patients had been diagnosed with cancer and eleven had suffered from at least one comorbidity within the last three months of life. In the last week of life, all patients were completely bedridden and incapable of self-care, all but one were unconscious or in a coma for one or more hours or days before death, and all experienced symptoms. In general, physical symptoms were reported more often than psychological ones. The most frequently reported physical symptoms were: lack of energy, lack of appetite, feeling drowsy, and pain. The psychological symptoms most frequently reported were feeling nervous and feeling sad. For all but one patient (case n°12) the symptoms also caused serious distress.

Table 2.

Life-ending drug use in general practice without patient's explicit request - aggregated (n = 13)

| Sociodemographic characteristics * | n | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at death | 1-64 years | 3 |

| 65-79 years | 6 | |

| ≥ 80 years | 4 | |

| Sex | Male | 8 |

| Female | 5 | |

| Educational level* | Elementary or lower | 2 |

| Lower secondary | 6 | |

| Higher secondary or more | 4 | |

| Community of Belgium | Dutch community | 6 |

| French community | 7 | |

| Fixed partner at time of death | Yes | 6 |

| No | 7 | |

| Place of death | Home | 8 |

| Care home | 5 | |

| Symptom burden in the last week of life (MSAS-GDI) † | ||

| Physical symptoms | Lack of energy | 12 (6) |

| Pain | 9 (5) | |

| Dry mouth | 8 (5) | |

| Difficulty breathing | 8 (4) | |

| Feeling drowsy | 10 (3) | |

| Constipation | 7 (2) | |

| Lack of appetite | 11 (1) | |

| Psychological symptoms | Feeling sad | 7 (5) |

| Feeling nervous | 9 (4) | |

| Worrying | 6 (4) | |

| Feeling irritable | 5 (3) | |

| End-of-life care provision | ||

| Patient-GP encounters | In last week of life (range) | 1-15 |

| In last 3 months of life (range) | 6-42 | |

| Clinical specialist involved in care in last 3 months of life | None | 4 |

| Sometimes or often | 9 | |

| Informal care over last 3 months of life | None | 1 |

| Sometimes or often | 12 | |

| Treatment goal over last 3 months of life | Comfort/palliation | 5 |

| Transition to comfort/palliation | 8 | |

| Consideration of curative or life-prolonging treatments by GP ‡ | Not possible anymore | 7 |

| Still possible but not applied | 6 | |

| Reasons why not applied § | Physician deemed chance for improvement too small | 4 |

| Physician wanted to end further suffering | 4 | |

| Patient refused treatment (verbally or non-verbally) | 2 | |

| Proxies wanted to end further suffering | 1 | |

| Proxies were psychologically and physically exhausted | 1 | |

| Consideration of alternative palliative treatments by GP ‡ | Not possible anymore | 10 |

| Still possible but not applied | 3 | |

| Reasons why not applied § | Physician did not want to prolong patient's life | 1 |

| Physician wanted to end further suffering | 2 | |

| Patient refused treatment | 1 | |

| Multidisciplinary palliative home care team involved in last three months of life | Yes | 4 |

| No | 9 | |

* Missing values for level of education n = 1;

† Symptoms that were present during the last week before death, despite possible treatment. Between brackets: symptoms that distressed the patient, if present. Distress levels were measured for all but one case (patient comatose during last week) using the MSAS-GDI. Psychological symptoms were considered to have caused distress if patient did appear to feel this way "frequently" or "almost constantly". Physical symptoms were considered to have caused distress if symptom distressed the patient "quite a bit" or "very much"

‡ At the time of the decision making

§Multiple answers were possible;

For six patients, GPs judged curative or life-prolonging treatments to be available which were not applied for reasons such as affording little chance of improvement or risking additional suffering. In three cases it was considered that palliative treatment options were available but they were not applied because the patient refused further treatment or the physician judged it preferable not to prolong treatment or the life of the patient. Multidisciplinary palliative home care was involved in four cases.

At the time of decision-making, the GP judged the medical situation of all thirteen patients as without any prospect of improvement (Additional file 2, Table S2). Nine were considered to suffer persistently and unbearably to a high or very high degree. All patients suffered physically and/or psychologically to some degree, in ways which could not be alleviated otherwise though one GP deemed the patient's suffering not persistent and unbearable (case n°13). According to this GP 'the suffering was kept under control by medication'; though any attempts at improving the patient's medical situation had been futile and ending life was 'clearly the best for him' (qualitative additional information). In all cases GPs based their judgments on observation and compassion; and in ten cases also after conferring with patients themselves (before they lost competence), their loved ones, or with other professional caregivers (not shown in table).

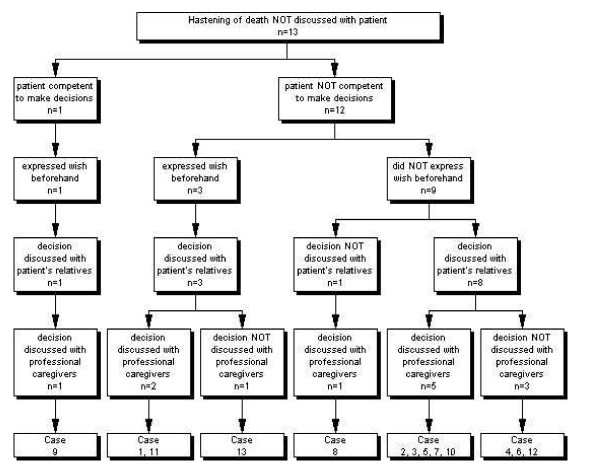

Decision-making process

All but one patient had lost the capacity to assess their situation and to make an informed decision about it (Figure 2). Reasons for incompetence cited were: the patient could no longer communicate, or was severely demented, unconscious, mentally disabled or considered too young (not shown in figure). One patient was considered competent but not able to express himself well (case n°9) and had earlier expressed a wish not to suffer anymore although this wish was not an explicit request to hasten death. In this case the medical situation was judged futile to the extent that, in the GP's view, the decision was in the patient's best interest. The GP made the decision in collaboration with a colleague physician and after several discussions with the patient's children.

Figure 2.

The discussion of the decision.

Nine patients were not competent to make decisions and had not expressed an advance wish about the termination of life. Within this group, the decision to end life was always discussed with either the relatives or a professional caregiver, and mostly with both. In one case no relatives were involved because the patient no longer had family.

In three cases the GP indicated that a wish had been expressed on various occasions while the patient was still competent which, although according to the GP not explicit, bore upon life-ending e.g. 'I do not want to suffer at the end of life' (qualitative additional information).

Nurses were involved in the decision-making in seven cases for the purpose of exchange of information, joint decision-making, support, or the arrangement of practicalities. Colleague physicians were involved in three cases when they were asked for information, advice, support, or to make the decision jointly. A frequent reason for lack of discussion with a colleague physician was that there was no need or that the situation was clear (not shown in figure).

In seven cases the GP felt influenced by the patient's relatives when making the decision: in five the family was supportive: 'we were on the same wavelength', 'it counts that the family indicates it is taking too long', 'they asked me: can't you do anything?'. In two cases the GP indicated that the family was initially not ready to consider such a decision, until they were confronted with the increasingly unbearable pain and suffering of their relative (qualitative additional information).

Additional file 3, Table S3 displays other end-of-life decisions made in each case in a chronological manner. In all cases the decision to end life without explicit patient request was preceded by or made jointly with the decision to intensify symptom alleviation. Decisions to withhold or withdraw treatment were also made for ten patients, often at different times. The following treatments were decided to be withheld or withdrawn: the administration of medication (n = 8); artificial hydration or nutrition (n = 7); chemotherapy or radiotherapy (n = 3); reanimation (n = 2); a blood transfusion (n = 1); the performance of an operation (n = 1).

In seven cases the GP decided to sedate the patient continuously and deeply until death, and in five of these this decision was made at the same time as the use of life-ending drugs. While for most patients the decision to end life was made within the last weeks or days, two GPs - in collaboration with the patient's relatives - made it more than one month before death. For one patient (case n°12), the relevant drugs (morphine and dormicum) were made available seven months prior to administration in the event that the brain tumor made suffering unbearable without possible alleviation which was the case in the end. For one other patient (case n°9), the drugs were available for several weeks before death and kept in the patient's house, in case the relatives agreed upon on ending the patient's life; the GP told them: 'it is you who has to decide' (qualitative additional information).

Characteristics of the performance of the practice

None of the patients was competent at the time of the administration of the drugs (Table 3). The hastening of death involved the administration of opioids in all but one case; seven patients received no other drug but opioids, and opioids were combined with a benzodiazepine in five other cases. A barbiturate induced death for one patient (case n°10). Neuromuscular relaxants were not used at all.

Table 3.

Life-ending drug use without patient's explicit request: performance of the practice (n = 13)

| n | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient was competent at time of drug administration | 0 | ||

| Drugs used to end life | Opioids only | 7 | |

| Opioids in combination with a benzodiazepine | 5 | ||

| Barbiturate | 1 | ||

| In case opioids were used to end life (n = 12) | Use of opioids already administered previous to | 9 | |

| life-ending practice to alleviate pain or other symptoms | |||

| Time between administration of (first) life-ending drug and coma | Patient was already in a coma at time of administration | 6 | |

| Patient never lapsed into a complete coma | 1 | ||

| (awoke now and then) | |||

| 15 minutes | 1 | ||

| 2 hours | 1 | ||

| 8 hours | 1 | ||

| 1 day | 1 | ||

| 2 days | 2 | ||

| Time between administration of (first) life-ending drug and death | instantly | 1 | |

| 20 minutes | 1 | ||

| 90 minutes | 2 | ||

| 3 hours | 1 | ||

| 4 hours | 1 | ||

| 12 hours | 1 | ||

| 13 hours | 1 | ||

| 1-2 days | 3 | ||

| 2-3 days | 2 | ||

| Persons involved in administration | Person who administered the (last) life-ending drug | GP | 7 |

| Nurse | 6 | ||

| GP's presence during the administration of life-ending drugs until the time of death | Continuously | 2 | |

| With short interruptions | 3 | ||

| Not present, but on call | 6 | ||

| Not present | 2 | ||

| Other persons present during the administration of life-ending drug | Professional caregivers & patient's relatives | 2 | |

| Professional caregivers only | 3 | ||

| Patient's relatives only | 7 | ||

| No other persons present | 1 | ||

| GP's estimation of life-shortening effect of administration of life-ending drugs | < 1 day | 2 | |

| 1-7 days | 8 | ||

| 1-4 weeks | 2 | ||

| > 6 months | 1 | ||

In three quarters of cases where the GP indicated opioids were used to end life, they had already been administered previously to alleviate pain or other symptoms. In six cases, patients were already in a coma at the time the first drug was administered and most others lapsed into a coma within the following hours. All patients died within three days of the first drug being administered. Three GPs reported having technical problems during the administration: one reported the occurrence of unexpected spasms (case n°7), one expected death to occur more rapidly (case n°3), and one expected it to occur more slowly (case n°6) (not shown in table).

In seven cases the final drug was given by the GP and in six by a nurse (case n°3/4/5/6/7/8). For all patients for whom death occurred in a care home a nurse administered the drug without presence of the GP although the GP was on call in four out of five of these cases (not shown in table). Relatives of the patient were present during the administering of the drug in nine cases. The estimated life-shortening effect was for all but one patient less than one month. This one patient (case n°10) had lost all brain function several months before death and had been held in a coma ever since (qualitative additional information).

All GPs said that the instigation of life-ending had improved their patients' end-of-life quality to some or to a considerable extent.

Discussion

In this interview study, we examined the practice of life-ending drug use without explicit patient request in thirteen cases in general practices in Belgium. The GPs involved indicated that at the time of making the decision there was no realistic prospect of improvement in the condition of any of these patients, most of whom who were suffering persistent and unbearable pain. Almost all patients had lost the capacity to assess their situation and to make decisions. In all cases the life-ending decision was discussed with other caregivers and/or those close to the patient and had preceded, accompanied or was followed by at least one other end-of-life decision. All but one patient received opioids with the explicit intention of hastening the end of life. GPs believed without exception that the patient's end-of-life quality had been improved considerably by their actions.

This is the first study to report on the practice of life-ending drug use without explicit patient request and to provide detailed information on an individual level on clinical characteristics during the last phase of life, on the decision-making process and on the performance of the practice. One major strength is that the thirteen cases were selected from a large two-year registration study, representative of all non-sudden deaths in the country [10], and gathered via a nationwide Sentinel Network representative of all GPs in Belgium. As such, the number of patients dying non-suddenly following life-ending drug use without explicit request in general practice (2.0%) was very similar to estimated incidence figures described in other studies in Belgium in 2001 (2.3%) [12]. Furthermore, the collected data are considered to be of high quality because the cooperation of the GPs in the network is optimal, because all interviews were conducted face to face by two researchers and as soon as possible after inclusion, and because quality control measures were used in both the registration and the interview study.

Finally, since the incidence of life-ending drug use has been shown to be relatively high compared with other countries [4-6] this study of Belgium is of particular interest.

However, because of the small sample of cases the results have to be interpreted cautiously. Notwithstanding that 13 interviews out of a possible 17 were conducted, the four additional interviews could probably have provided even more insight into the nature of this delicate practice. Also, due to the retrospective design of the study a possible recall bias could not be excluded entirely, or some decisions might have been interpreted differently a posteriori. Finally, our findings remain limited to the experiences of GPs. Views of patients, their family, and other caregivers were not studied.

The current study shows that patients who die following the practice of life-ending drug use without explicit request are those who suffer from incurable lingering diseases and whose quality of life dwindles drastically in the last phase. Although some patients were still fully active and ambulatory during the third month before death, they were all completely bedridden and incapable of self-care in the last week of life. Their medical situation within the final days was characterized mainly by unbearable and persistent suffering, characterized by physical as well as psychological symptom burden or by intermittent or permanent unconsciousness. That being in a coma is seen as a kind of suffering might seem inconsistent, but this might be explained by a subjective, compassionate interpretation GPs make at this very end of their long-lasting relationship with the patient. As the GPs believed without exception that their patient's end-of-life quality had been improved considerably by taking this step, it appears that they acted out of compassion and chose what they believed to be the least bad option in a medically futile situation. Whether compassion alone may in some cases justify this practice remains subject to intense debate however [29].

Another important finding of the study is that, even though patients did not or were not able to make an explicit life-ending request, GPs were in many cases unaware of their patient's wishes. This is remarkable since 95% of the population has a regular GP in Belgium [30] and have often built up a long-lasting relationship over the course of many years [31,32]. An explanation may be found in previous research that indicated that GPs experience uncertainty about initiating end-of-life discussions with their patients [33-35] which could mean that they wait for the moment at which decision-making becomes relevant, by which time patients may no longer have the capacity to express their wishes themselves. Therefore, advance care planning, i.e. communication with patients to explore their wishes in the case that they become unable to participate in decision-making [36], remains a matter of great concern in current general practice as GPs are in a key position to initiate and facilitate such discussions [37-40].

Although consultation rarely takes place with patients themselves, it does occur frequently with others: GPs do not appear to act surreptitiously or as isolated decision-makers but to involve both other professional caregivers and the patient's close circle in the decision-making process. This might suggest that GPs have a need for the exchanging of information, for consultation and advice, and for making these decisions jointly with others. However, it should be noted that in some cases the GP felt no need to discuss the decision with other professional caregivers. Furthermore, it is remarkable that multidisciplinary palliative home care teams are not consulted more often within the last months of these patients' lives, even though in Belgium they are available to all GPs in the country. The question however remains as to whether the involvement of such teams would have led to a different end-of-life decision.

Several of our findings further suggest that this end-of-life practice is quite complex and that for the GPs involved it resembles the process of intensified symptom alleviation with a possible life-shortening effect or the process of continuous deep sedation until death rather than a separate and lethal act such as euthanasia. Firstly, such decisions (symptom alleviation/sedation) were made in all cases in addition to the explicit decision to end the patient's life, and often at the same time. Therefore it seems that these medications were often given with a dual purpose: alleviating symptoms and hastening the end of life. Secondly, death did not occur immediately after the administration of the drugs. In a substantial number of cases several hours or days passed by before the patient died. This is in contradiction to what could be expected where a practice such as euthanasia was intended. Thirdly, even though there is strong evidence that the lethal potential of opioids and sedatives is doubtful and they therefore considered unsuitable agents where the hastening of death is explicitly intended [41-43], opioids, whether or not in combination with a benzodiazepine, were the predominant drug used. In addition, opioids were often already being administered to alleviate pain and symptoms prior to the life-ending action. The use of a neuromuscular relaxant which is noted in literature as an efficient euthanaticum with immediate life-shortening effect [44] was not administered in any of the reported cases. Other studies confirm that opioids are commonly in this practice [6,45].

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study shows that the practice of life-ending drug use without explicit patient request in general practice often seems to be an act of compassion to end the unbearable suffering of patients who can no longer decide for themselves. Our study provides various indications that the line between different end-of-life decisions is not always easy to define as the clinical context of this practice leans towards the process of intensified symptom alleviation or of continuous deep sedation until death. Although GPs are often not aware of their patient's end-of-life wishes, they do not act as isolated decision-makers and involve other professional caregivers and the patient's close circle in the decision. Advance care planning could inform GPs about their patient's wishes before the patient becomes incompetent.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

KM had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis, and drafted and revised the manuscript. LVDB contributed to the design, coordination and funding of the study, the analysis of the data and to the drafting and revisions of the manuscript. NB and JB participated in the design and coordination of the study, and contributed to the interpretation of the data, and critically revised the manuscript. ME contributed to the interpretation of the data, and critically revised the manuscript. LD contributed to the design, coordination and funding of the study, contributed to the interpretation of the data, and critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Life-ending drug use in general practice without patient's explicit request: patients' clinical characteristics during the last phase of life - case level (n = 13).

Table S2. Life-ending drug use in general practice without patient's explicit request: patient's suffering at the time of the decision-making (n = 13).

Table S3. Life-ending drug use without patient's explicit request and the process of decision-making: timing and involvement of other end-of-life decisions (n = 13).

Contributor Information

Koen Meeussen, Email: koen.meeussen@vub.ac.be.

Lieve Van den Block, Email: lvdblock@vub.ac.be.

Nathalie Bossuyt, Email: nbossuyt@iph.fgov.be.

Michael Echteld, Email: Michael.Echteld@vumc.nl.

Johan Bilsen, Email: johan.bilsen@vub.ac.be.

Luc Deliens, Email: luc.deliens@vub.ac.be.

Acknowledgements

This study is part of the 'Monitoring Quality of End-of-Life Care (MELC) Study', a collaboration between the Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Ghent University, Antwerp University, the Scientific Institute of Public Health, Belgium, and VU University Medical Center Amsterdam, the Netherlands. This study is supported by a grant from the Institute for the Promotion of Innovation by Science and Technology in Flanders (SBO IWT nr. 050158). The Belgian Sentinel Network of GPs is supported by the Flemish and Walloon Community of Belgium. The study protocol and anonymity procedures were approved by the ethical review board of the University Hospital of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel

We thank Viviane Van Casteren, the coordinator of the Sentinel Network of GPs in Belgium, for her advice and expertise in setting up this study, and all participating sentinel GPs providing data.

References

- Deliens L, Mortier F, Bilsen J, Cosyns M, Vander Stichele R, Vanoverloop J. End-of-life decisions in medical practice in Flanders, Belgium: a nationwide survey. Lancet. 2000;356:1806–1811. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03233-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, van der Heide A, Koper D, Keij-Deerenberg I, Rietjens JA, Rurup ML. Euthanasia and other end-of-life decisions in the Netherlands in 1995, and 2001. Lancet. 1990;362:395–399. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Maas PJ, van der Wal G, Haverkate I, de Graaff CL, Kester JG, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD. Euthanasia, physician-assisted suicide, and other medical practices involving the end of life in the Netherlands, 1990-1995. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1699–1705. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199611283352227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Heide A, Deliens L, Faisst K, Nilstun T, Norup M, Paci E. End-of-life decision-making in six European countries: descriptive study. Lancet. 2003;362:345–350. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seale C. National survey of end-of-life decisions made by UK medical practitioners. Palliat Med. 2006;20:3–10. doi: 10.1191/0269216306pm1094oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Heide A, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Rurup ML, Buiting HM, van Delden JJ, Hanssen-de Wolf JE. End-of-life practices in the Netherlands under the Euthanasia Act. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1957–1965. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa071143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Block L, Bilsen J, Deschepper R, Van Der Kelen G, Bernheim JL, Deliens L. End-of-life decisions among cancer patients compared with noncancer patients in Flanders, Belgium. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2842–2848. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.7531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Gendt C, Bilsen J, Mortier F, Vander Stichele R, Deliens L. End-of-life decision-making and terminal sedation among very old patients. Gerontology. 2008;55:99–105. doi: 10.1159/000163445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rietjens JA, Bilsen J, Fischer S, van der Heide A, van der Maas PJ, Miccinessi G. Using drugs to end life without an explicit request of the patient. Death Stud. 2007;31:205–221. doi: 10.1080/07481180601152443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Block L, Deschepper R, Bilsen J, Bossuyt N, Van Casteren V, Deliens L. Euthanasia and other end-of-life decisions: a mortality follow-back study in Belgium. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:79. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilsen J, Vander Stichele R, Mortier F, Bernheim J, Deliens L. The incidence and characteristics of end-of-life decisions by GPs in Belgium. Fam Pract. 2004;21:282–289. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmh312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Bilsen J, Fischer S, Lofmark R, Norup M, van der HA. End-of-life decision-making in Belgium, Denmark, Sweden and Switzerland: does place of death make a difference? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61:1062–1068. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.056341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Block L, Deschepper R, Bilsen J, Van Casteren V, Deliens L. Transitions between care settings at the end of life in Belgium. JAMA. 2007;298:1638–1639. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.14.1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Block L, Van Casteren V, Deschepper R, Bossuyt N, Drieskens K, Bauwens S. Nationwide monitoring of end-of-life care via the Sentinel Network of General Practitioners in Belgium: the research protocol of the SENTI-MELC study. BMC Palliat Care. 2007;6:6. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-6-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming DM, Schellevis FG, Van Casteren V. The prevalence of known diabetes in eight European countries. Eur J Public Health. 2004;14:10–14. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/14.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devroey D, Van Casteren V, Buntinx F. Registration of stroke through the Belgian sentinel network and factors influencing stroke mortality. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2003;16:272–279. doi: 10.1159/000071127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroobant A, Van Casteren V, Thiers G. In: Surveillance in Health and Disease. Eylenbosch WJ, Noah D, editor. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1988. Surveillance systems from primary-care data: surveillance through a network of sentinal general practitioners; pp. 62–74. [Google Scholar]

- Lobet MP, Stroobant A, Mertens R, Van Casteren V, Walckiers D, Masuy-Stroobant G. Tool for validation of the network of sentinel general practitioners in the Belgian health care system. Int J Epidemiol. 1987;16:612–618. doi: 10.1093/ije/16.4.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boffin N, Bossuyt N, Van Casteren V. IPH/EPI REPORTS N° 2007 - 013. Scientific Institute of Public Health Belgium; Unit of Epidemiology; 2007. Current characteristics and evolution of the Sentinel General Practitioners: data gathered in 2005 [Huidige kenmerken en evolutie van de peilartsen en hun praktijk. Gegevens verzameld in 2005]http://www.iph.fgov.be/epidemio/epien/index10.htm [Google Scholar]

- Van den Block L. End-of-life care and medical decision-making in the last phase of life. Brussels, VUB Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Block L, Deschepper R, Bilsen J, Van Casteren V, Deliens L. Transitions between care settings at the end of life in belgium. JAMA. 2007;298:1638–1639. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.14.1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block L Van den, Deschepper R, Drieskens K, Bauwens S, Bilsen J, Bossuyt N. Hospitalisations at the end of life: using a sentinel surveillance network to study hospital use and associated patient, disease and healthcare factors. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:69. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman SE, Tilden VP, Tolle SW. Family reports of dying patients' distress: the adaptation of a research tool to assess global symptom distress in the last week of life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22:565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(01)00299-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J, Davis TE, McFadden ET. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5:649–655. doi: 10.1097/00000421-198212000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). The SUPPORT Principal Investigators. JAMA. 1995;274:1591–1598. doi: 10.1001/jama.274.20.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinkenberg M. The last phase of life of older people: health, preferences and care: a proxy report study. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: PhD thesis, EMGO Institute, VU Amsterdam; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Deeg D, Beekman A, Kriegsman D, Westendorp-de Serière M. Autonomy and well-being in the aging population II: Report from the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam 1992-1996. Amsterdam: VU University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- van der Wal G, van der Heide A, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, van der Maas PJ. Medical decision-making at the end of life: practice in The Netherlands and the evaluation procedure of euthanasia [Medische besluitvorming aan het einde van het leven: de praktijk en de toetsingsprocedure euthanasie] Utrecht, The Netherlands: De Tijdstroom Uitgeverij; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Materstvedt LJ. Palliative care on the 'slippery slope' towards euthanasia? Palliat Med. 2003;17:387–392. doi: 10.1191/0269216303pm796oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayingana K, Demarest S, Gisle L, Hesse E, Miermans PJ, Tafforeau J. Health survey interview, Belgium 2004. Depotn°: D/2006/2505/4, IPH/EPI REPORTS N° 2006 - 035. Scientific Institute of Public Health Belgium, Department of Epidemiology; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Munday D, Dale J, Murray S. Choice and place of death: individual preferences, uncertainty, and the availability of care. J R Soc Med. 2007;100:211–215. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.100.5.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michiels E, Deschepper R, Van Der Kelen G, Bernheim J, Mortier F, Vander Stichele R. The role of general practitioners in continuity of care at the end of life: a qualitative study of terminally ill patients and their next of kin. Palliat Med. 2007;00:1–7. doi: 10.1177/0269216307078503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tierney WM, Dexter PR, Gramelspacher GP, Perkins AJ, Zhou XH, Wolinsky FD. The effect of discussions about advance directives on patients' satisfaction with primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:32–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.00215.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschepper R, Vander Stichele R, Bernheim JL, De Keyser E, Van Der Kelen G, Mortier F. Communication on end-of-life decisions with patients wishing to die at home: the making of a guideline for GPs in Flanders, Belgium. Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56:14–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown M. Participating in end of life decisions. The role of general practitioners. Aust Fam Physician. 2002;31:60–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teno JM, Nelson HL, Lynn J. Advance care planning. Priorities for ethical and empirical research. Hastings Cent Rep. 1994;24:S32–S36. doi: 10.2307/3563482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel LL, Danis M, Pearlman RA, Singer PA. Advance care planning as a process: structuring the discussions in practice. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:440–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb05821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitken PVJr. Incorporating advance care planning into family practice [see comment] Am Fam Physician. 1999;59:605–620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher R. An approach to advance care planning in the office. Can Fam Physician. 2006;52:459–464. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright CM, Parker MH. Advance care planning and end of life decision making. Aust Fam Physician. 2004;33:815–819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sykes N, Thorns A. The use of opioids and sedatives at the end of life. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4:312–318. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(03)01079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorns A, Sykes N. Opioid use in last week of life and implications for end-of-life decision-making. Lancet. 2000;356:398–399. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02534-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sykes N, Thorns A. Sedative use in the last week of life and the implications for end-of-life decision making. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:341–344. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.3.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royal Dutch Society for the Advancement of Pharmacy (KNMP). Utilization and Preparation of Euthanasia Drugs [In Dutch] The Hague, The Netherlands; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rurup ML, Borgsteede SD, van der Heide A, van der Maas PJ, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD. Trends in the use of opioids at the end of life and the expected effects on hastening death. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37:144–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belgisch Staatsblad 22 juni 2002 [Belgian official collection of the laws June 22 2002]. Wet betreffende euthanasie 28 mei 2002 [Law concerning euthanasia May 28, 2002] (in Dutch). 2002009590. 2002.

- Mitchell K, Owens RG. National survey of medical decisions at end of life made by New Zealand general practitioners. BMJ. 2003;327:202–203. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7408.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Life-ending drug use in general practice without patient's explicit request: patients' clinical characteristics during the last phase of life - case level (n = 13).

Table S2. Life-ending drug use in general practice without patient's explicit request: patient's suffering at the time of the decision-making (n = 13).

Table S3. Life-ending drug use without patient's explicit request and the process of decision-making: timing and involvement of other end-of-life decisions (n = 13).