Abstract

The ability to manipulate gene expression in Xenopus oocytes and then generate fertilized embryos by transfer into host females has made it possible to rapidly characterize maternal signaling pathways in vertebrate development. Maternal mRNAs in particular can be efficiently depleted using antisense deoxyoligonucleotides (oliogs), mediated by endogenous RNase-H activity. Since the microinjection of antisense reagents or mRNAs into eggs after fertilization often fails to affect maternal signaling pathways, mRNA depletion in the Xenopus oocyte is uniquely suited to assessing maternal functions. In this review, we highlight the advantages of using antisense in Xenopus oocytes and describe basic methods for designing and choosing effective oligos. We also summarize the procedures for fertilizing cultured oocytes by host transfer and interpreting the specificity of antisense effects. Although these methods can be technically demanding, the use of antisense in oocytes can be used to address biological questions that are intractable in other experimental settings.

Keywords: Xenopus, oocyte, antisense, host-transfer, maternal mRNA, oligonucleotide

1. Introduction

Xenopus oocytes have been widely used to study normal cellular functions, such as cell cycle progression, cell physiology and apoptosis. Additionally, the ability of Xenopus oocytes to translate virtually any injected message (1) has been exploited to investigate post-translational protein modification and secretion, assembly and function of various receptors and channels, as well as mechanisms of transcription and splicing (please see other review articles in this issue). Although the role of the oocyte as a model for cell and molecular biology is well recognized, oocytes can also be manipulated to give information about the mechanisms of early development. In Xenopus, as in many other organisms, the majority of RNAs and proteins used in early development are stored in oocytes, and large-scale zygotic RNA synthesis does not occur until the mid-blastula stage (mid-blastula transition or MBT) (2, 3). Numerous experiments have shown that critical cell fate and patterning decisions occur during this period, including primordial germ cell specification, germ layer induction and patterning, and dorsoventral axis formation (4). Owing to allopolyploidy and long reproductive cycles, the generation of maternal effect mutations is not likely to be practical in Xenopus laevis, although such strategies could be pursued in the diploid Xenopus tropicalis (5). Consequently, alternate methods have been developed in Xenopus to assess the roles of maternal factors by loss-of-function, the most useful of these being the injection of antisense DNA oligodeoxynucleotides (oligos) into oocytes.

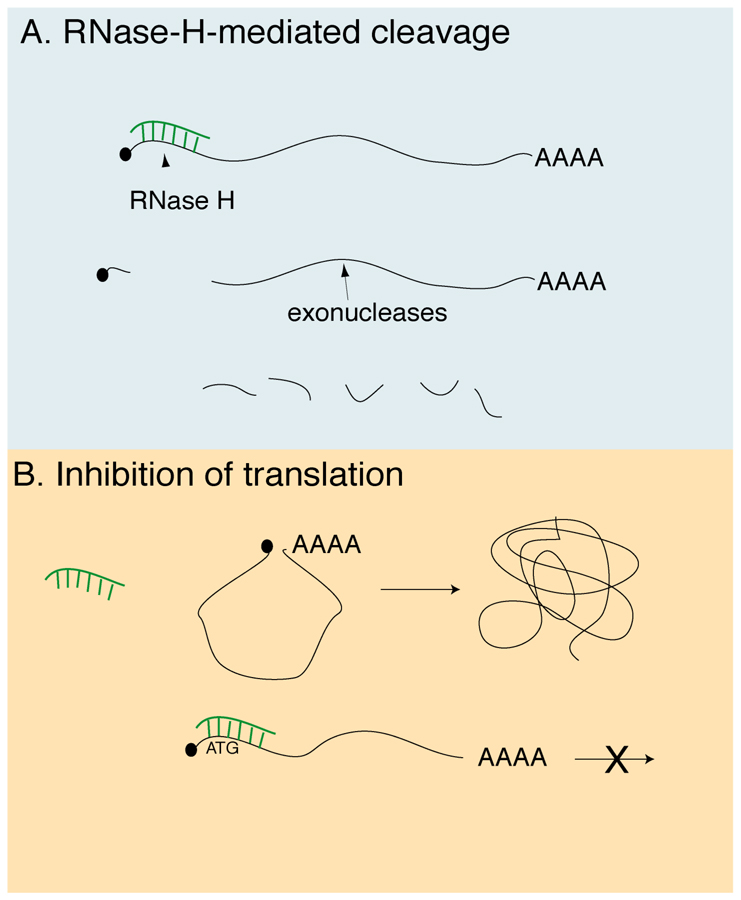

The inhibition of gene function by antisense relies on the ability of complementary RNA or DNA sequences to hybridize with and inhibit endogenous mRNAs. There are two main classes of antisense reagents (Fig. 1), those that degrade the message through cleavage of the RNA strand the DNA:RNA hybrid by RNase-H, generally considered the more potent mechanism, and those that form a stable hybrid that blocks translation or splicing of the transcript, such as morpholino oligos (morpholinos, or MOs). Recently, MOs have been used to inhibit gene expression during embryonic development (6), whereas traditional DNA-based oligos have remained more useful for oocyte studies. Several features of the Xenopus oocyte greatly facilitate the use of antisense oligos. First, oligos can be easily microinjected directly into the oocyte, so delivery into the cell is not an issue, whereas cellular uptake has been problematic for pharmacological antisense applications. Second, oligos are known to work by an RNase-H-like activity in oocytes (7), causing degradation of the message. Also, degradation of target mRNAs and of the oligo itself occur within 24 hours, so extended culture is not required (8, 9). Additionally, modified and unmodified oligos are more stable and less toxic in oocytes compared with fertilized eggs and embryos (9). Oocytes are transcriptionally quiescent and thus oligos deplete the target in the absence of competition from newly synthesized message.

Fig. 1.

Mechanisms of antisense oligo action. (A) Degradation of target mRNA by RNase-H cleavage (phosphodiesters, phosphorothioates, chimeric oligos). (B) Inhibition of translation by steric hinderanee (morpholinos, fully modified oligos).

Injection of antisense molecules against endogenous mRNAs into oocytes can be used to study functions occurring in living oocytes (splicing, oocyte maturation, nuclear reprogramming). However, in order to determine the effects of maternal mRNA depletion on embryonic development, it is necessary to fertilize the cultured oocytes, typically by transferring them into an ovulating host female. This approach has been used successfully to demonstrate the role of maternal mRNAs in cell adhesion and cell signaling during dorsal axis and germ layer specification and has been quite effective in analyzing the role of localized mRNAs in development. In many cases, depleting the maternal mRNA in the oocyte produced a phenotype in the resulting embryos that was not predicted from gain-of-function studies or function-blocking experiments following injection into fertilized eggs. Depletion of maternal β-catenin resulted in dorsal axis defects and highlighted the importance of the Wnt signaling pathway in this process (10, 11). Antisense depletion was also useful in uncovering the critical role of vegt, a vegetally localized T-box mRNA, in germ layer formation. Initial overexpression experiments suggested VegT had a role in patterning the mesoderm (12–14), however depletion of maternal vegt mRNA revealed essential functions in the formation of endoderm and in the initiation of mesoderm induction (15, 16). Depletion studies also identified an important germline function for dazl, (17) a germ plasm-localized mRNA with high similarity to human Deleted in Azoospermia [DAZ], a gene required for sperm production (18).

In certain cases, overexpression and loss-of-function effects are only manifest by manipulation of the oocyte. E-cadherin overexpression causes ventralization only if injected at high doses into the oocyte (10). Similarly, robust activation of canonical Wnt signaling by wnt11 occurs only if it is expressed prior to fertilization (19). Antisense depletion of maternal tcf3 mRNA prior to fertilization results in dorsalization of the embryo (20), whereas inhibition of tcf3 translation using morpholino reagents following fertilization causes a headless phenotype (21). Depletion of vegt in oocytes causes a loss of endoderm and mesoderm (16), in contrast to inhibition in embryos, which leads to anteriorization (22). In these cases it is likely that sufficient protein is made during oocyte maturation or immediately after fertilization. This phenomenon is not limited to Xenopus.

In zebrafish, wnt5 morpholino injections after fertilization (23) fail to recapitulate the phenotype of wnt5 maternal effect mutants (24). Therefore, short of generating maternal null animals, antisense and oocyte transfer may be the most effective means of routinely assessing maternal function in early development.

In this article, we review the methodology for loss-of-function studies in oocytes using antisense oligos. We describe the design, modification and screening of effective oligos. In addition, we review methods for fertilizing cultured oocytes and for analyzing the results of mRNA depletion on embryonic development. We also discuss the potential for new modifications and types of oligos to be used in loss-of-function in Xenopus oocytes.

2. The use of oligos in antisense experiments

2.1 Introduction to using oligos in Xenopus oocytes

Xenopus was one of the first organisms where antisense was vigorously pursued as a means to block the expression of developmentally interesting genes. Oocytes subsequently became a primary model system in which to understand the mechanisms of antisense-mediated gene inhibition. Dash et al. (7) and Cazenave et al. (25) showed that antisense oligos could specifically degrade exogenous and endogenous RNAs in Xenopus oocytes through an RNase-H mediated mechanism. Early on, experiments using oligos were successful in demonstrating a role for c-mos in oocyte maturation in culture (26). Initial attempts to degrade maternal RNAs in oocytes and obtain fertilized embryos using unmodified oligos were, however, confounded by high toxicity (27) or the inability to deplete maternal protein stores (28). Using terminally modified chimeric oligos (29), Wylie and Heasman and colleagues generated the first embryonic loss-of-function phenotype by fertilizing oocytes depleted of maternal cytokeratin mRNA (30). Initial experiments used chimeras containing a central region of diesters, flanked by methoxyethyl phosphoroamidate linkages, however chimeras incorporating phosphorothioate bonds have predominated more recently, since these are readily available commercially and inexpensive.

2.2 Rationale for using thioate modified, chimeric oligos

Without attempting a review of various oligo chemistries, there are several considerations that favor the use of phosphorothioate/diester chimeric oligos for antisense experiments in oocytes. Unmodified phosphodiester oligos are highly unstable and ineffective at sub-toxic doses in fertilized eggs and oocytes (9, 27, 29). Oligos modified along the entire length with phosphorothioate linkages (thioates) are stable in oocytes (9), but will likely persist into embryogenesis if the oocytes are fertilized, causing toxic effects in the resulting embryos. A variety of modifications can be made to oligos to increase nuclease resistance, however most of these, with the exception of thioate modification, also block RNase-H activity (31). Chimeras were made to increase stability, placing nuclease-resistant modifications on the ends while leaving a central region of phosphodiesters available as an RNase-H substrate (29, 31). Thioate/diester chimeras are more stable than completely unmodified oligos, but not excessively so, and are likely to be completely degraded during culture. Terminally modified thioate chimeras have an estimated half-life of ~ 3 hours in mammalian cells (32), whereas other modifications (e.g., phosphoroamidate) allow oligos to persist and degrade target mRNAs for at least 24 hours (33). Chimeric phosphorothioate oligos have little effect below about 2 ng (per oocyte) and become toxic above 5–6 ng. The effects of oligo overdose are usually only evident after fertilization and include a failure to undergo cleavage, gastrulation arrest or dissociation of the embryos. Toxicity is most likely mediated by addition of excess nucleotides to the nucleotide pool following oligo degradation or binding of the oligo to cellular proteins (34). Since phosphorothioates are RNase-H substrates, the placement of these is not critical, although 3–4 linkages on each end are usually sufficient. If other modifications are used (neutral or positive backbone modifications or sugar modifications), the central region of diesters should be at least 6 nucleotides long to allow RNase-H recognition (27, 35).

2.3 Limits to antisense oligo specificity

The exquisite precision of nucleotide base pairing underlies much of the promise for antisense oligos as genetic tools. Unfortunately, it has been difficult to predict the specificity of oligos in different contexts. Specificity is a function of sequence complementarity and hybrid stability, which in turn depends on oligo stability. Despite the potential of being able to specifically target any gene, theoretical and practical constraints generally limit the specificity that can be achieved. Longer oligos should confer more specificity, but also have a higher propensity to form secondary structure, which could block its activity. Longer oligos also are more likely to cleave to a partially complementary sequence in a non-target mRNA, termed irrelevant cleavage (27, 36). RNase-H can cleave short duplex regions within a partially matched hybrid (36), offsetting the gain in specificity conferred by increased length. Degradation of partially matched sequences has prompted the suggestion that it is probably theoretically impossible to design an oligo that would not have off-target effects (36). It is likely, however, that most of these unintended targets do not have important functions in early development. Also, many oligos that are perfectly complementary to their target mRNAs do not cause degradation (see below). Thus, it is unclear to what extent the theoretical limits to oligo specificity apply in vivo. Regardless, the possibility of oligo non-specificity is an important caveat that must be considered.

2.4 DNA oligos versus morpholinos

More recently, morpholino oligos have been found to be useful antisense reagents in embryos, although these are not RNase-H substrates and act through steric hindrance to block either translation or splicing (37). Morpholinos are generally highly stable in oocytes and embryos and are considered non-toxic at high doses, although some sequences do have inexplicable toxic side effects, as reviewed in (38). While MOs can certainly be used in oocyte experiments, they do not act catalytically and thus require higher doses. MOs can be particularly useful, however, when analyzing the effects of localized maternal RNA depletion. Degradation of vegt or other mRNAs localized to the vegetal cortex can cause certain classes of other localized RNAs to become delocalized (39, 40), which could affect the interpretation of the resulting phenotype. Since MOs do not cause the destruction of target mRNAs, they can be used to confirm that any observed phenotypes are due to loss of individual RNA function and not to perturbations in RNA localization.

Generally, a good antibody is necessary to determine the effectiveness of an MO, whereas oligo efficacy can be measured through analysis of RNA levels by RT-PCR. If oocytes are to be fertilized and embryos obtained, MOs are likely to endure and also affect zygotic gene expression, which may make it problematic to separate strict maternal functions from zygotic ones. Additionally, the user has very little control over the design of MOs, being limited to sequences in the 5’UTR and those flanking the start codon (37). By contrast, DNA oligos can be designed to target almost any region in the mRNA, since internal cleavage will result in degradation of the entire transcript by exonucleases.

3. Designing and testing oligos for depletion of the target mRNA

3.1 Design parameters for antisense oligos

The process of designing effective antisense oligos involves a relatively simple trial-and-error approach. Most suppliers have web-based design tools which can select optimal oligo sites or analyze oligo sequences for undesirable characteristics. Additionally, many of the parameters used in selecting PCR primers also seem to apply for antisense oligo design, namely a balanced GC content (40–60%), moderate Tm (50°C–60°C) and lack of hairpin formation and self annealing.

Appropriate oligo length is important to achieving good specificity in antisense experiments. Statistically, a length of 12–15 nucleotides has been cited as the shortest sequence likely to be unique within vertebrate genomes (36). Commonly, a length of 16–20 nucleotides is used to balance specificity with antisense efficiency. As discussed in section 2, increasing the length carries the risk of decreasing the specificity. Our lab routinely uses 18-mers, which are synthesized with three terminal phosphorothioate linkages on each end in their final form.

Certain nucleotide compositions have been documented to have non-specific effects and should be avoided. In particular, four consecutive guanines or repeats of guanine or cytosine dimers or trimers have the propensity to form G-tetraplexes and other exotic structures through Hoogsteen pairing and have potent nonantisense effects on cells (41). Runs of three or more of any single nucleotide, palindromes, and CG dimers have been linked to stimulation of the immune system, triggering a biological effect that could be confused with an antisense effect (34). Although this is not directly relevant to use in oocytes, these effects indicate that certain sequences have a higher incidence of non-effects in general, and should be avoided if possible.

Oligos can generally be designed to bind anywhere on the target message. We tend to favor the 5’ half of transcripts if possible, since cleavage near the 3’ end could leave stable fragments capable of producing at least a partial protein. Areas around the start codon are good starting points, since this area is likely to be accessible. An empirical approach of testing several candidates generally has the best chance of identifying effective oligos with minimal expense and effort. Although it is tempting to use an RNA folding algorithm to predict accessible sites in the target mRNA, it is unclear what constitutes an accessible site, and the accuracy of these programs is not known in most cases.

3.2 Screening for effective antisense oligos

Since one is unlikely to identify successful oligo target sites a priori from sequence information, several candidates must be synthesized and tested for depletion of the desired mRNA. A typical strategy is to design and test several unmodified oligos, find the most effective one or two, and re-synthesize them in phosphorothioate-modified form. From a set of ten or so oligos, usually one or more will cause degradation of the target mRNA. In several instances where the screening was described, the success rates were 1/12 and 2/10 for oligos against vegt and axin, respectively (16, 42). In this scheme, antisense oligos are designed more or less randomly along the mRNA sequence and checked for the suitable characteristics using primer design software. It is also beneficial to check whether the candidates match all of the alloallelic variants by performing BLAST searches. This will also determine if any of the candidates have a high degree of complementarity to other genes, related or not, that may be present in the oocyte. Sequencing the gene of interest from frogs in the colony could help identify highly polymorphic sequences to be avoided. Regions of identity between Xenopus laevis and Xenopus tropicalis might be useful to target, since these sequences are likely to be non-polymorphic within X. laevis.

Candidate oligos are ordered in small-scale and minimal purity, desalting only, dissolved at a concentration of 1 mg/ml in deionized water and tested by injection into manually defolliculated oocytes. At least two doses are injected, 5 and 10 ng per oocyte, since effective oligos will usually work in a dose-responsive fashion. The oocytes are then cultured from 4 hours to overnight and frozen for analysis of target mRNA levels (see below). Effective oligos will result in substantial depletion at both doses, with greater depletion at the higher dose, and little-to-no effect on non-specific mRNAs. The desired oligos are then re-ordered in modified and HPLC-purified form and are then tested to find an effective dose. If none of the oligos deplete the target mRNA, the process is repeated until one is found.

Although this method will generally result in a suitable antisense oligo, there are several drawbacks to screening with unmodified oligos. In addition to the added time required for multiple rounds of synthesis and testing, impurities in the oligo preps can cause blockage of microinjection needles. It is also not guaranteed that the modified version of the oligo will work effectively at a non-toxic dose, since phosphorothioate modification can lower the affinity of an oligo for its target. To avoid these possible problems, we have started testing small-scale syntheses of thioate-modified/HPLC purified chimeric oligos directly. The price of modified-purified oligos has decreased considerably, and can now be synthesized at a 50–100 nanomolar-scale for under $75 (US). We typically design 3–5 modified oligos to test using several handpicked ones, as well as some designed by various software programs. We have successfully used Primer3, MacVector and the IDT antisense design tool1.

3.3 Analysis of depletion efficacy and specificity

The most direct way of measuring the effectiveness of antisense oligos is to analyze the steady state level of the target mRNA after injection. Northern analysis, RNase protection assays or RT-PCR can be used, although quantitative assays such as RNase protection or realtime qPCR will give a more accurate indication of overall depletion. For qPCR, oocytes are frozen in batches of three-to-five in microfuge tubes on dry ice, and total RNA is isolated. RNAs are then treated with RNase-free DNase, reverse transcribed into cDNA and analyzed. Levels of target mRNA in the oligo-injected samples are measured by comparison against a standard curve of diluted, uninjected control cDNA. A reduction of the target to below 20% of control levels is considered a successful knockdown. Although this method gives a direct readout of the effectiveness of the oligo, it does not measure overall inhibition of gene expression, since the cognate target protein may endure after degradation of the message. If available, antibodies against the protein target or an assay of its specific activity (e.g., enzyme activity, DNA-binding activity) can be used to estimate the extent that the desired molecular function is being inhibited. Through trial and error, one or two oligos that deplete the target mRNA can usually ultimately be identified. In case of consistent dismal failure, it might be necessary to try other types of nucleotide modifications.

As discussed in section 2, there will likely always be the possibility that oligos will bind and cleave messages other than the intended target. Therefore, specific controls are needed to determine the extent that any phenotypic effects seen are the result of degradation of the intended mRNA. Ideally, at least two oligos recognizing different sequences on the target mRNA and producing similar depletion levels and phenotypes can be identified. Since the two sequences will be unlikely to target the same non-specific mRNA, it is reasonable to assume that the effects are probably specific. Oligos against the target that do not degrade the mRNA or mismatched oligos can also be used as controls to identify non-specific effects of oligo injection.

The most appropriate control is to rescue the effect by injecting transcript of the gene of interest, in effect replacing the mRNA that was degraded. This should be done in a manner that does not inhibit the oligo itself, to avoid simply swamping the oligo with exogenous RNA. Rescue injection can be done either by waiting until the oligo degrades (>24 hours, or ~ 8 half-lives; (32) or by using a transcript lacking the oligo binding sequence. The use of the homologous gene from another species (mouse, human or X. tropicalis) can be useful in rescue experiments, since the nucleotide sequence will likely be different enough to avoid being targeted by the antisense oligo. Alternatively, conservative third base point mutations in the oligo binding region can be made to protect the injected transcript (33).

4. Fertilization of cultured oocytes by the host-transfer method

4.1 Overview of host-transfer in amphibians

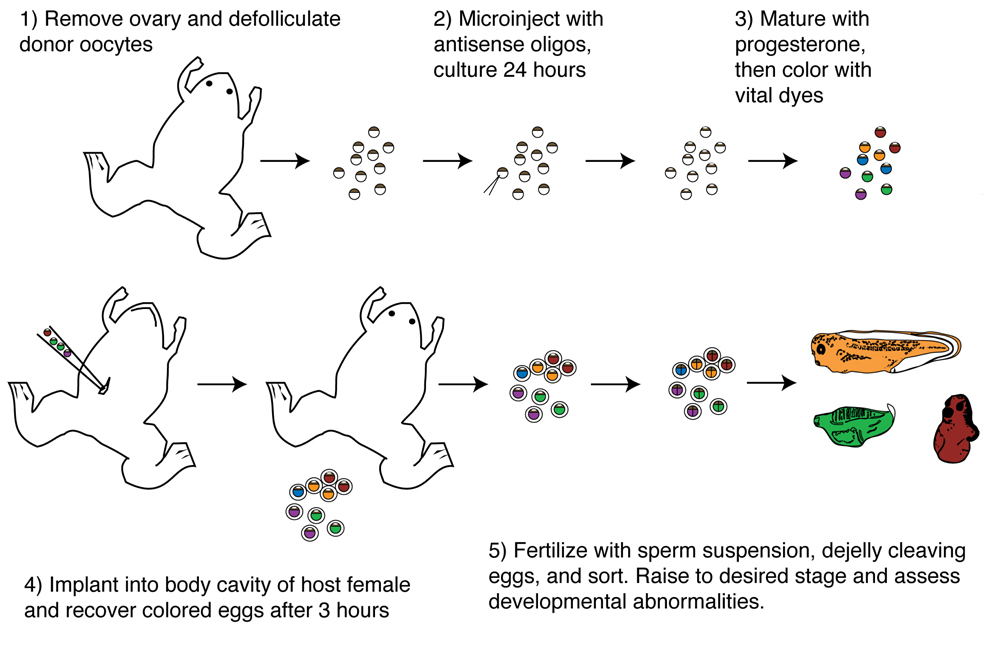

Amphibian oocytes and eggs cannot be fertilized until they pass through the oviduct and are enveloped by jelly coats, allowing sperm penetration. One approach to fertilizing cultured oocytes is to transfer mature oocytes into the body cavity of egg laying host females (Fig. 2), whereupon they will be moved by cilia lining the coelomic epithelium into the oviducts (43). This host-transfer technique was originally developed to study the relative roles of jelly coats and meiotic maturation state in fertilization, and has been used successfully in many amphibian species, including Triturus (44), several species of Rana (45, 46) and Xenopus (47). Oocytes treated with progesterone can also be fertilized by host-transfer (47, 48), affording the opportunity for manipulation in culture and subsequent analysis of development. In the past few decades, the host-transfer method has been gradually optimized (49–51) and is commonly used for fertilizing oocytes injected with antisense oligos. Mature oocytes can also be fertilized in culture following removal of the vitelline membrane and treatment with sperm incubated in exogenous jelly conditioned water (28, 52), although this method is less commonly used.

Fig. 2.

Diagram of the host-transfer procedure. Ovary is obtained from females by laparotomy, and full-grown stage VI oocytes are manually defolliculated and cultured in oocyte culture medium. Antisense oligonucleotides are injected at doses of 2–6 ng, depending on the gene of interest. Injected oocytes are cultured 24 hours to allow mRNA and oligo degradation to occur, and are treated with 2µM progesterone. The next day, oocytes are colored with vital dyes and transferred to ovulating host females. Eggs are obtained and fertilized by in vitro fertilization.

4.2 Isolating the donor ovary tissue

Oocytes to be used for antisense oligo injection followed by host-transfer must be manually defolliculated from the donor ovary tissue, as collagenase treatment damages oocytes too heavily to be fertilized. Healthy oocytes are essential to getting large numbers of embryos from these experiments, so it is worthwhile to keep a separate set of well-maintained frogs specifically for obtaining ovary. The ovary is procured from the donor female by laparotomy (partial oophorectomy). The donor female is anesthesized in buffered MS222 (0.1% MS222 + 0.7 % sodium bicarbonate) and a small incision is made in the lower abdomen. The desired quantity of ovary tissue is removed and placed in oocyte culture medium (OCM [60% L-15 medium, 0.4 mg/ml BSA, 1 mM glutamine, 0.1 mg/ml gentamicin](50)). The muscle/fascia layers and skin layer are sutured separately using sterile surgical techniques and the female is allowed to recover. The same female can be used multiple times to obtain ovary, allowing several months between uses. Most institutions allow five survival surgeries on a single female, along with a sixth terminal operation.

Once the ovary has been removed, it is subdivided into small pieces using scissors and forceps and stored at 18°C in OCM until use. Several lobes should be sufficient material to isolate many hundreds of oocytes. The ovary can be stored for up to several days, but oocytes should be transferred within 96 hours of removal from the frog. Each lobe is opened flat and trimmed into small squares, which are placed in dishes of fresh OCM, about 5 pieces per dish. This subdivision makes subsequent defolliculation easier and prevents contamination and deterioration of the tissue due to overcrowding in the dish.

4.3 Defolliculating and injecting oocytes

Individual oocytes are manually removed from the follicle layers using watchmakers’ forceps. Although defolliculating can be frustrating initially, it is a skill almost anyone can learn with practice. Properly sharpened and polished forceps are essential, as is proper technique (53). A loose grip on the forceps works best, using only enough pressure to make the tips meet. Closing the tips tightly will result in the oocyte being pulled from the ovary with removing the follicle layer. Defolliculated oocytes are injected with the desired oligos and cultured 24–48 hours at 18°C. This culture period allows for degradation of both the target mRNA and the antisense oligo itself, which is critical since residual oligo may become toxic when the oocytes are fertilized.

Groups of 75–200 oocytes are a convenient size, allowing a suitable number of embryos to be recovered for analysis. Due to limits on the number of colors that can be used to identify the different experimental and control groups following transfer into the female, only five or six groups of oocytes can be transplanted into a single host female, so experiments must be planned accordingly. Rescue mRNAs are injected typically on the day prior to performing the transfer. Effective rescue doses will depend on the gene of interest, but usually lie in the 20 pg-300 pg range. Pilot experiments are performed to determine a dose that does not have a prominent gain-of-function effect on control embryos, thus giving more confidence that any restoration of phenotype is due to replacement of function and not ectopic signaling. Injections can also be performed following fertilization, using normal embryo injection methods. Generally, rescue is considered successful if the knockdown effects can be alleviated in most of the cases, either by phenotypic or molecular analysis.

4.4 Implantation into host females and obtaining fertilized embryos

The evening before the transfer is to be performed, females are primed with human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG, 1000 units) and the oocytes are stimulated with progesterone (2 µM final concentration). Frogs and oocytes are maintained at 18°C overnight. Performing both hCG and progesterone treatment at the same time provides a good match between the maturation state of the donor eggs with the host, allowing for optimum fertilization efficiency. Oocytes that are transferred too late (>18 hours) or too soon (<6 hours) after progesterone treatment will fertilize poorly, if at all. We have had the best success when hCG injection and progesterone treatment are done 12 hours prior to transfer. On the morning of the transfer, the oocytes are colored with vital dyes2 to distinguish the groups from each other and from the host eggs. Once the desired staining level is reached (~10 minutes incubation), oocytes are washed in fresh OCM and set aside until the host frog is anesthetized and ready for transfer. While the eggs are coloring, a host frog is identified and placed in anesthetic. The host must be laying good quality eggs and, ideally, will have just started ovulating by the time the transfer is done. An incision is made in the abdomen, the eggs are introduced into the body cavity using a fire-polished Pasteur pipette and the incision is rapidly sutured. The female will recover and resume laying eggs normally, and the colored eggs will begin to appear two-to-three hours later.

Once recovered, transferred eggs can be fertilized in vitro, dejellied and sorted by color, and otherwise treated as ordinary embryos. Typically, 30–60% of the transferred oocytes will fertilize, cleave and survive to the point of analysis (gastrula/neurula). Enough embryos will usually be recovered to follow developmental phenotypes over time, in a statistically significant manner. The main determinants of success of the host-transfer procedure are the health of the donor oocytes and host frog. If either is compromised, the oocytes will fail to fertilize or insufficient numbers will be recovered from the host. Although there are no concrete indicators of whether a particular host female or batch of oocytes will work well, at least half of the attempts will yield enough embryos for analysis. Numerous experimental repetitions using different donor females are recommended to hedge against variability in oocyte quality and antisense effectiveness.

5. Future directions and summary

For this review, we have focused on using commercially available, phosphorothioate-modified oligos in oocytes. The main determinants for successful antisense experiments are the careful selection and screening of candidate oligos and the use of proper controls to distinguish specific antisense effects from non-specific effects. The results obtainable are highly consistent within a particular batch of oocytes and are generally repeatable across experiments. Occasionally, an oligo that has worked at one time will cease to be effective, suggesting either polymorphisms in the target mRNA sequence or variability in different lots of oligo synthesis. As with any other form of pharmacologic treatment, the dose of the antisense reagent is critical in these experiments. Identifying a minimal effective dose for RNA degradation and extending the incubation time should successfully lower the incidence of any toxic effects. In general, the degree of oligo specificity is likely to always be significant variable in antisense experiments. It might be interesting to use newer technology such as microarrays to measure the extent that irrelevant cleavage occurs in oocytes.

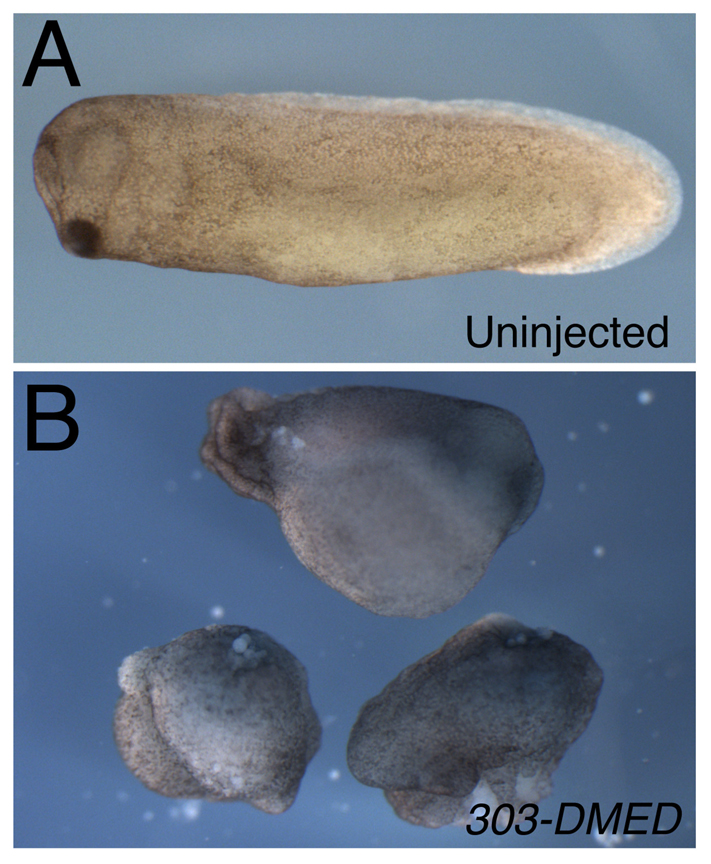

Although thioates work well and are the major type of modification currently in use, there is room for optimization of oligo design and use. Chimeras containing modifications to the sugar residues, such as 2’-O-methyl RNAs (2’OMe), locked nucleic acid residues (LNA) and backbone modification using cationic N,N-dimethylethylenediamines (DMED); (54), can effectively degrade target RNAs in embryos (55) and in oocytes (our unpublished observations). Overall, these reagents have lower toxicity and superior potency and specificity compared with thioate oliogs (55). These modifications were mainly attempted to extend the effectiveness of the antisense oligo beyond MBT. Indeed, a DEED-modified oligo (similar to DMED) against lim1 succeeded in generating a loss-of-function phenotype in embryos after MOs proved ineffective (56). These types of oligos could also be used at lower doses or shorter incubation times in oocytes, which could lead to fewer non-specific effects. Along these lines, we have successfully used a DMED-modified chimera of a published oligo against β-catenin (oligo 303, (10)) in host transfer experiments. Injection of this oligo at a dose of 400 pg into oocytes generated a high incidence of ventralized embryos (Fig. 3) with less death due to toxicity than is seen with 1 ng of the cognate thioate-modified oligo. Currently, only the 2’OMe and LNA modifications are commercially available and are more expensive that thioates, but the prospect of fewer side effects and fewer repetitions of experiments may make them worth the expense.

Fig. 3.

Depletion of β-catenin mRNA in oocytes using a DMED-modified chimera. (A) Phenotype of a stage 28 embryo derived from an uninjected oocyte. (B) Ventralized phenotypes of sibling β-catenin-depleted embryos, injected as oocytes with 400 pg of oligo 303-DMED.

In summary, antisense has been particularly successful in Xenopus oocytes largely because antisense oligos can be efficiently injected into the cell, the mechanism of antisense is well characterized, and the injected oocytes can be cultured for extended periods. Furthermore, simple and inexpensive types of oligos can be used, without need for extraordinary stability or systemic tolerance. When coupled with the ability to fertilize the depleted oocytes, the depletion of maternal mRNAs in oocytes becomes an effective and rapid method for elucidating key mechanisms in early development. As with any loss-of-function technique, a lack of effect creates uncertainties as to whether the gene in truly necessary, or to what extent there are redundant molecules or there was insufficient knockdown of function. However, despite the numerous variables present and labor-intensive nature of the procedures, these methods can be used to address important biological questions that are intractable in other model systems, and are almost always worth the effort.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dan Weeks for critical reading of the manuscript and for the synthesis of the 303-DMED oligo. This work was supported by The University of Iowa and by NIH 5R01 GM083999-02 to D.W.H.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Final vital dye concentrations: Blue, 0.001% Nile Blue A (Aldrich 121479-5G); Neutral Red: 0.0025% Neutral Red (Sigma N-6634), Brown: 0.01% Bismarck Brown. Five colors are possible; each of the single colors plus Mauve (Blue + Red) and Green (Blue + Brown).

References

- 1.Gurdon JB, Lane CD, Woodland HR, Marbaix G. Nature. 1971;223:177–182. doi: 10.1038/233177a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bachvarova R, Davidson EH, Allfrey VG, Mirsky AE. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1966;55:358–365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.55.2.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newport JW, Kirschner MW. Cell. 1984;37:731–742. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90409-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heasman J. Development. 1997;124:4179–4191. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.21.4179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirsch N, Zimmerman LB, Grainger RM. Dev Dyn. 2002;225:422–433. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heasman J, Kofron M, Wylie C. Dev Biol. 2000;222:124–134. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dash P, Lotan I, Knapp M, Kandel ER, Goelet P. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:7896–7900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.22.7896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shuttleworth J, Colman A. Embo J. 1988;7:427–434. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02830.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woolf TM, Jennings CG, Rebagliati M, Melton DA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:1763–1769. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.7.1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heasman J, Crawford A, Goldstone K, Garner-Hamrick P, Gumbiner B, McCrea P, Kintner C, Noro CY, Wylie C. Cell. 1994;79:791–803. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wylie C, Kofron M, Payne C, Anderson R, Hosobuchi M, Joseph E, Heasman J. Development. 1996;122:2987–2996. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.10.2987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lustig KD, Kroll KL, Sun EE, Kirschner MW. Development. 1996;122:4001–4012. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.12.4001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stennard F, Carnac G, Gurdon JB. Development. 1996;122:4179–4188. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.12.4179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J, King ML. Development. 1996;122:4119–4129. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.12.4119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kofron M, Demel T, Xanthos J, Lohr J, Sun B, Sive H, Osada S, Wright C, Wylie C, Heasman J. Development. 1999;126:5759–5770. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.24.5759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang J, Houston DW, King ML, Payne C, Wylie C, Heasman J. Cell. 1998;94:515–524. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81592-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Houston DW, King ML. Development. 2000;127:447–456. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.3.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reijo R, Lee TY, Salo P, Alagappan R, Brown LG, Rosenberg M, Rozen S, Jaffe T, Straus D, Hovatta O, Page D. Nat Genet. 1995;10:383–393. doi: 10.1038/ng0895-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tao Q, Yokota C, Puck H, Kofron M, Birsoy B, Yan D, Asashima M, Wylie CC, Lin X, Heasman J. Cell. 2005;120:857–871. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Houston DW, Kofron M, Resnik E, Langland R, Destree O, Wylie C, Heasman J. Development. 2002;129:4015–4025. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.17.4015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu F, van den Broek O, Destree O, Hoppler S. Development. 2005;132:5375–5385. doi: 10.1242/dev.02152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishibashi H, Matsumura N, Hanafusa H, Matsumoto K, De Robertis EM, Kuroda H. Mech Dev. 2008;125:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lele Z, Bakkers J, Hammerschmidt M. Genesis. 2001;30:190–194. doi: 10.1002/gene.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Westfall TA, Brimeyer R, Twedt J, Gladon J, Olberding A, Furutani-Seiki M, Slusarski DC. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:889–898. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200303107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cazenave C, Chevrier M, Nguyen TT, Hélène C. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:10507–10521. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.24.10507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sagata N, Oskarsson M, Copeland T, Brumbaugh J, Vande Woude GF. Nature. 1988;335:519–525. doi: 10.1038/335519a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shuttleworth J, Matthews G, Dale L, Baker C, Colman A. Gene. 1988;72:267–275. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90152-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kloc M, Miller M, Carrasco AE, Eastman E, Etkin L. Development. 1989;107:899–907. doi: 10.1242/dev.107.4.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dagle JM, Walder JA, Weeks DL. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:4751–4757. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.16.4751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Torpey N, Wylie CC, Heasman J. Nature. 1992;357:413–415. doi: 10.1038/357413a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agrawal S, Mayrand SH, Zamecnik PC, Pederson T. PNAS. 1990;87:1401–1405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fisher TL, Terhorst T, Cao X, Wagner RW. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:3857–3865. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.16.3857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raats JM, Gell D, Vickers L, Heasman J, Wylie C. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev. 1997;7:263–277. doi: 10.1089/oli.1.1997.7.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krieg AM, Stein CA. Antisense Res Dev. 1995;5:241. doi: 10.1089/ard.1995.5.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dagle JM, Weeks DL, Walder JA. Antisense Res Dev. 1991;1:11–20. doi: 10.1089/ard.1991.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woolf TM, Melton DA, Jennings CG. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:7305–7309. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Summerton J, Weller D. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev. 1997;7:187–195. doi: 10.1089/oli.1.1997.7.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heasman J. Dev Biol. 2002;243:209–214. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heasman J, Wessely O, Langland R, Craig EJ, Kessler DS. Dev Biol. 2001;240:377–386. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kloc M, Bilinski S, Dougherty MT. Experimental Cell Research. 2007;313:1639–1651. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benimetskaya L, Berton M, Kolbanovsky A, Benimetsky S, Stein CA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2648–2656. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.13.2648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kofron M, Klein P, Zhang F, Houston DW, Schaible K, Wylie C, Heasman J. Dev Biol. 2001;237:183–201. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rugh R. J Exp Zool. 1935;71:163–194. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Humphries A. J Morphol. 1956;99:97–135. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arnold J, Shaver J. Exp Cell Res. 1962;27:150–153. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(62)90054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lavin L. J Embryol Exp Morph. 1964;12:457–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brun R. Experientia. 1975;31:1275–1276. doi: 10.1007/BF01945777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith LD, Ecker RE, Subtelny S. Dev Biol. 1968;17:627–643. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(68)90010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heasman J, Holwill S, Wylie CC. Methods Cell Biol. 1991;36:213–230. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60279-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zuck MV, Wylie CC, Heasman J. In: "A comparative methods approach to the study of oocytes and embryos". Richter JD, editor. Oxford: Oxford University Ptress; 1998. pp. 341–354. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mir A, Heasman J. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;469:417–429. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-469-2_26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Elinson R. J Exp Zool. 1973;183:291–302. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith LD, Xu W, Varnold RL. Methods Cell Biol. 1991;36:45–60. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60272-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dagle JM, Littig JL, Sutherland LB, Weeks DL. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:2153–2157. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.10.2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lennox KA, Sabel JL, Johnson MJ, Moreira BG, Fletcher CA, Rose SD, Behlke MA, Laikhter AL, Walder JA, Dagle JM. Oligonucleotides. 2006;16:26–42. doi: 10.1089/oli.2006.16.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hukriede NA, Tsang TE, Habas R, Khoo PL, Steiner K, Weeks DL, Tam PP, Dawid IB. Dev Cell. 2003;4:83–94. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00398-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]