Abstract

This report explains typical radiographic features of Scottish Fold osteochondrodysplasia. Three Scottish Fold cats suffering from lameness were referred to the Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital, Seoul National University, Korea. Based on the breed predisposition, history, clinical signs, physical examination, and radiographic findings, Scottish Fold osteochondrodysplasia was confirmed in three cases. Radiographic changes mainly included exostosis and secondary arthritis around affected joint lesions, and defective conformation in the phalanges and caudal vertebrae. The oral chondroprotective agents such as glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate make the patients alleviate their pain without adverse effects.

Keywords: lameness, osteochondrodysplasia, Scottish Fold cat

The Scottish Fold is a purebred cat with forward-folded ears, autosomal-dominant inherited trait and an outward sign of generalized defective cartilage formation [1,7,8]. Scottish Fold osteochondrodysplasia (SFOCD) is an inheritable disorder characterized by skeletal deformities such as short, thick, and inflexible tails and shortened splayed feet [1,2,6].

Affected cats show signs of lameness, reluctance to jump, stiff, and stilted gait [1,6,10]. These ambulatory difficulties are due to progressive osteoarthritis resulting from defective maturation and dysfunction of cartilage [1,9]. Radiographic features include irregularity in the size and shape of tarsal, carpal, metatarsal and metacarpal bones, phalanges, and caudal vertebrae, narrow joint spaces, and progressive new bone formation around joints of distal limbs with diffuse osteopenia of adjacent bone, formation of a plantar exostosis caudal to the calcaneus in advanced cases [6,10]. Radiographic changes are usually more spectacular in the hind limbs [1].

Treatment is noncurative, but pentosan polysulfate, glycosaminoglycans, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), or a combination of these treatment might be palliative [6]. In more severe cases, surgical approaches such as ostectomy and pantarsal arthrodeses, or palliative irradiation is optional [4, 7]. The purpose of this study is to summarize general aspects of SFOCD in three cats admitted to Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital of Seoul National University, Korea.

Case 1: A two-year old, spayed female, body weight 2.3 kg, Scottish fold cat was admitted for intermittent lameness of right hind limb for two weeks. The affected right tarsal joint was painful on palpation and the distal hind limbs were abnormally short. The patient was usually reluctant to jump and move.

Bilateral hind limb radiographs demonstrated radiographic changes consistent with SFOCD. The distal tibia and fibula, tarsal and metatarsal bones and phalanges were not markedly deformed, although the metatarsal bones were a bit shorter than normal. Extensive new bone formation was seen around the tarsus and proximal portion of the metatarsus (Fig. 1). The intertarsal and tarsometatarsal joint spaces appeared indistinct and narrowed irregularly and tarsal bones had a moth-eaten appearance, contributing to overlying periarticular bone. The lesions of the right tarsus were more prominent than those of the left tarsus, although there were similar signs. The cat was treated with meloxicam (0.1 mg/kg) daily for three days for pain control and then medicated with a complex of glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate.

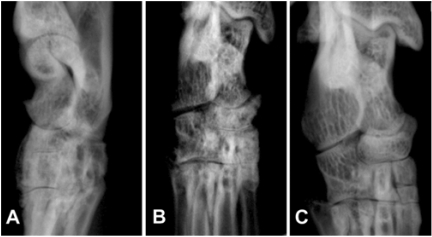

Fig. 1.

Lateral (A) and dorsopalmar (B) radiographs of the right distal pelvic limbs of the case 1. Extensive periarticular new bone formation around the tarsus (A) and proximal portion of the metatarsus is present. The intertarsal and tarsometatarsal joint spaces and margin (B) appear indistinct compared to normal tarsus (C).

Case 2: A four-month old, female, body weight 1.2 kg, Scottish Fold kitten was referred with lameness of the right hind limb for 1 week. The kitten was disinclined to climb and retreated to the comfort of her bed rather than socializing. The short and stiff tail, and thick feet were evident compared with other littermates.

Radiographs of the pelvis, hind limbs, and caudal vertebrae were obtained. There was mild extensive periarticular new bone formation around the right tarsal and proximal metatarsal joints in plantarolateral aspect (Fig. 2A). The metatarsal bones and phalanges were shorter than normal, and misshapen asymmetrically (Fig. 2B). The interphalangeal joint spaces were irregular and widening (Fig. 2B). Immediately after diagnosis, meloxicam (0.1 mg/kg) was prescribed daily for three days, and followed by glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate.

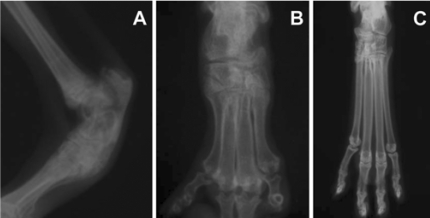

Fig. 2.

Lateral (A) and dorsoplantar (B) radiographs of the right pelvic limb of the case 2. There is mild new bone formation (A) in the plantarolateral aspect of the right pelvic limb. The metatarsal bones (B) are short, thick, splayed, and misshapen compared to normal metatarsal bones (C). The phalanges appear flared and hypoplastic.

Case 3: A three-year-old, intact female, body weight 3.0 kg, Scottish fold presented for evaluation of swelling of four limbs and associated lameness. The owner found swelling of hind limbs of the cat at 6-month of age. Both hock joints were initially enlarged with swelling. Carpal joints were recently appeared to be enlarged without pain. The cat had difficulty in walking, and could not jump onto a chair or onto a bed. Physical examination showed shortened splayed feet and short, thick and inflexible tail.

The radiographic changes were bilateral symmetric, and it was prominent in the tarsal joints. There was massive formation of new bone that bridges extending from the proximal calcaneus to the proximal metatarsus contributing to cuboidal bone fusion and tarsal ankylosis (Fig. 3). The new bone had a smooth margin but a typical trabecular pattern with a decreased radiopacity. Phalanges of all four limbs were usually short, malformed and splayed with flared sclerotic metaphyses (Fig. 4). The caudal vertebrae had various sizes of vertebral bodies and narrowed intervertebral spaces at the caudal vertebrae 5-8 regions. Therapeutic measurement was carried out by the combined administration of glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate for reducing the cat's discomfort.

Fig. 3.

Tarsal joint radiographs of the case 3. There is exuberant exostosis extending from the proximal calcaneus to the proximal metatarsal bones resulting in bony ankylosis.

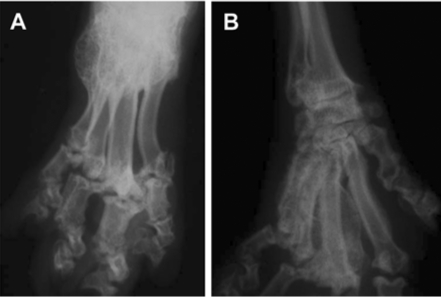

Fig. 4.

Dorsopalmar radiographs of the distal hindlimb (A) and forelimb (B) of the case 3. The metatarsal bones (A) are shortened, thickened, and splayed than normal. There is extensive and moderate periosteal reaction of phalanges (B) in the forelimb. The interphalangeal joint spaces are irregular and widening in both A and B.

In osteochondrodysplasia of Scottish Fold, the severity and duration of clinical manifestation, and radiographic lesions depend on genetic types. Cats homozygous for the gene (Fold-to-Fold matings) developed progressive skeletal changes, including epiphyseal and metaphyseal deformities, secondary osteoarthritis and exuberant exostosis around the distal extremities early in their lives, compared to heterozygote with much milder joint disorders later in their life [4,5,6,7].

SFOCD can be easily diagnosed through survey radiographs. Lesions are radiographically evident by 7 weeks of age [10]. Radiographic features of SFOCD are skeletal alterations and subsequent progressive ankylosing polyarthropathy affecting distal limb joints. Presented clinical signs are ambulatory problems, however, it is difficult for owners to recognize these signs. It is likely that a combination of the cat's small body stature and its ability to accommodate orthopedic abnormality by redistributing weight-bearing force to other limbs [3].

Generally, osteochondrodysplasia occurs due to defective endochondral ossification, resulting in disproportionate dwarfism and morphological defects in the axial and appendicular skeletons [10]. It is seen in only Scottish Fold cats and fast-growing, large and giant breeds of dogs such as Alaskan malamute, Great Pyrenees, Labrador retriever, Norwegian elkhound, Samoyed, and Scottish deerhound [6].

The proposed solution is to cease breeding cats with folded ears and restrict breeding to cats with a normal ear conformation such as Scottish short-haired cats [1]. While there is no specific treatment or cure for this disease, intermittent joint pain for advanced degenerative joint disease can be treated with chondroprotective agents such as glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate. These organic supplements are widely recommended for their potential value in helping animals suffering from arthritis and joint pain. It works by minimizing cartilage damage and swelling, increasing joint lubrication, helping to rebuild the cartilage that cushions and protects joints, and enhancing new cartilage production. In addition, affected cats have to take regular serial radiography to manage progressive and degenerative joint lesions.

References

- 1.Allan GS. Radiographic features of feline joint disease. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2000;30:281–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bulk RL, Feeney DA. The Appendicular skeleton. In: Bulk RL, Feeney DA, editors. Small Animal Radiology and Ultrasonography: A Diagnostic Atlas and Text. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2003. p. 543. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardie EM. Management of osteoarthritis in cats. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 1997;27:945–953. doi: 10.1016/s0195-5616(97)50088-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hubler M, Volkert M, Kaser-Hotz B, Arnold S. Palliative irradiation of Scottish Fold osteochondrodysplasia. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2004;45:582–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2004.04101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jack OF. Congenital bone lesions in cats with folded-ears. Bull Fel Advis Bur. 1975;14:2–4. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malik R, Allan GS, Howlett CR, Thompson DE, James G, McWhirter C, Kendall K. Osteochondrodysplasia in Scottish Fold cats. Aust Vet J. 1999;77:85–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1999.tb11672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mathews KG, Koblik PD, Knoeckel MJ, Pool RR, Fyfe JC. Resolution of lameness associated with Scottish Fold osteodystrophy following bilateral ostectomies and pantarsal arthrodeses: a case report. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1995;31:280–288. doi: 10.5326/15473317-31-4-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Partington BP, Williams JF, Pechman RD, Beach RT. What is your diagnosis? Scottish Fold osteodystrophy in a kitten. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1996;209:1235–1236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pedersen NC, Morgan JP, Vasseur PB. Joint diseases of dogs and cats. In: Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC, editors. Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000. p. 1874. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wisner ER, Konde LJ. Diseases of the immature skeleton. In: Thrall DE, editor. Textbook of Veterinary Diagnostic Radiology. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2002. pp. 155–156. [Google Scholar]