Abstract

The standard collagen triple-helix requires a perfect (Gly-Xaa-Yaa)n sequence, yet all nonfibrillar collagens contain interruptions in this tripeptide repeating pattern. Defining the structural consequences of disruptions in the sequence pattern may shed light on the biological role of sequence interruptions, which have been suggested to play a role in molecular flexibility, collagen degradation, and ligand binding. Previous studies on model peptides with 1- and 4-residue interruptions showed a localized perturbation within the triple-helix, and this work is extended to introduce natural collagen interruptions up to nine residue in length within a fixed (Gly-Pro-Hyp)n peptide context. All peptides in this set show decreases in triple-helix content and stability, with greater conformational perturbations for the interruptions longer than five residue. The most stable and least perturbed structure is seen for the 5-residue interruption peptide, whose sequence corresponds to a Gly to Ala missense mutation, such as those leading to collagen genetic diseases. The triple-helix peptides containing 8- and 9-residue interruptions exhibit a strong propensity for self-association to fibrous structures. In addition, a small peptide modeling only the 9-residue sequence within the interruption aggregates to form amyloid-like fibrils with antiparallel β-sheet structure. The 8- and 9-residue interruption sequences studied here are predicted to have significant cross-β aggregation potential, and a similar propensity is reported for ∼10% of other naturally occurring interruptions. The presence of amyloidogenic sequences within or between triple-helix domains may play a role in molecular association to normal tissue structures and could participate in observed interactions between collagen and amyloid.

Keywords: collagen, triple helix, self-assembly, peptide, amyloid, aggregation

Introduction

The structure of the collagen triple-helix consists of three polyproline II-like polypeptide chains that are supercoiled around a common axis.1,2 The close packing of the three chains near the central axis restricts every third residue to be Gly, and a high content of the imino acids Pro and hydroxyproline (Hyp) stabilizes the extended polyproline II chain structure.3 As a result of these constraints, collagen chains are easily identified by their characteristic (Gly-Xaa-Yaa)n amino acid sequence pattern, where the Xaa and Yaa positions are frequently occupied by Pro and Hyp, respectively. However, in many collagen types reported over the past decades, distinct (Gly-Xaa-Yaa)n regions are found separated by sequences that do not follow this pattern.4–6 In some chains, there are short imperfections in the repeating pattern that are likely to produce only small distortions of the triple-helix. In other cases, there are sequences of greater length that could separate (Gly-Xaa-Yaa)n regions into independent folding domains. Defining the structural consequences of disruptions in the sequence pattern will help clarify the relationship between collagen sequence and structure and may shed light on the biological role of such interruptions.

Currently, there are 28 reported types of human collagens including both fibril-forming collagens and nonfibrillar collagens.4–7 The five fibril-forming collagens (Types I, II, III, V, and XI) are found in periodic fibrils, and all contain ∼1000 residue perfect (Gly-Xaa-Yaa)n sequences.4 Two recently discovered collagens, Types XXIV and XXVII, appear to be part of the fibril-forming family, but each contain two interruptions in the repeating tripeptide pattern.8,9 All other collagens are considered to be nonfibrillar collagens, a diverse group including network-forming types, FACIT collagens, and transmembrane collagens.4–7 Every nonfibrillar collagen chain contains imperfections in the regular repeating (Gly-Xaa-Yaa)n motif, but the number of interruptions and their lengths vary depending on the collagen type. Within the long triple-helix domains of basement membrane Type IV collagen and anchoring fibril Type VII collagen, there are more than 20 interruptions with lengths varying from 1 to 41 residue.10,11 In contrast, Type X collagen, expressed in hypertrophic chondrocytes during bone growth, contains eight imperfections, which are all one or four residue in length.4

Peptides have been useful as models for the standard collagen triple-helix12–14 and can also serve to model non-standard structures. The perturbations caused by 1- and 4-residue imperfections have been characterized in model peptides by X-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy.15–17 These triple-helical peptides show distortion in dihedral angles and perturbed hydrogen bonding localized to the interruption site. In addition, the twist of the superhelix on one end of the peptide is out of register with the other end. In the peptide with a 4-residue interruption, Val residue occupy the sequence position where a Gly is expected and pack near the center of the triple-helix, creating a small hydrophobic core.16,18

To better understand the effect of interruptions of other lengths, previous studies were extended to introduce interruptions of 1–9 residue in length within a fixed Gly-Pro-Hyp peptide context. The effects of these interruptions on peptide conformation, stability, calorimetric enthalpy, and hydrodynamic properties were investigated, and a correlation was observed between length and triple-helix distortion. In addition, the peptides containing 8- and 9-residue interruptions show a strong propensity for self-association to fibrillar structures, and a short peptide with only the 9-residue interruption sequence forms fibrils containing antiparallel β structure. About 10% of all interruption sequences in nonfibrillar collagens have a predicted propensity to form amyloid-like fibrils, including the 8- and 9-residue sequences studied here.

Results

Peptides incorporating interruptions of 1–9 residue in length in a (Gly-Pro-Hyp)n repeating sequence

Previous studies on peptides with 1- and 4-residue interruptions16–18 are extended to create a series of peptides with interruption lengths of 1–9 (Table I). Interruptions from nonfibrillar collagens are introduced within a fixed context of repeating Gly-Pro-Hyp (GPO) triplets: (GPO)5G(Aaa)m(GPO)4GY. For instance, an interruption found in the sequence GAKGEOGEFYFDLRLKGDKGDO from the α1 chain of Type IV collagen22 is incorporated into the peptide (GPO)5GEFYFDLRLK(GPO)4. This is considered to be a 9-residue interruption, defined as the region between Gly-Xaa-Yaa-Gly sequences. Interruption sequences from natural nonfibrillar collagens are selected to contain representative amino acid features for that length, such as a high hydrophobic content (m = 1, 3, 4, 5, 8, and 9) or the presence of an imino acid at the C-terminal end (m = 5, 6, 7, and 8).

Table I.

Physical Properties of Peptides Containing Interruptions 1–9 Residue in Length, Showing Mean Residue Ellipticity at 225 nm (MRE225nm), Ratio of Positive to Negative Peak (Rpn) Values, Melting Temperature Determined by Circular Dichroism (Tm), Calorimetric Enthalpy (ΔHcal), and Hydrodynamic Radius (Rh)

| Length (residues) | Peptide sequencea | MRE225nm (deg cm2 dmol−1) | Rpnb | Tmc (°C) | ΔHcal (kJ mol−1) | Rh (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m = 1 | Ac-(GPO)5GV(GPO)4GY-NH2 | 3420 | 0.11 | 33.4 | 315 | 1.9 |

| α1(IV): 274 | ||||||

| m = 3 | Ac-(GPO)5GLAL(GPO)4GY-NH2 | 3215 | 0.10 | 24.5 | 267 | 1.9 |

| α1(VII): 2019–2021 | ||||||

| m = 4 | Ac-(GPO)5GAAVM(GPO)4GY-NH2 | 3700 | 0.10 | 38.2 | 247 | 2.0 |

| α5(IV): 390–393 | ||||||

| m = 5 | Ac-(GPO)5GPPALO(GPO)4GY-NH2 | 4035 | 0.12 | 41.2 | 432d | 2.1 |

| α1(XIX): 386–390 | ||||||

| m = 6 | Ac-(GPO)5GQTITQP(GPO)4GY-NH2 | 2370 | 0.08 | 30.5 | 193 | 2.1 |

| α5(IV): 657-662 | ||||||

| m = 7 | Ac-(GPO)5GEVLGAQP(GPO)4GY-NH2 | 2465 | 0.09 | 22.5 | 254 | 2.1 |

| α2(IV): 775–781 | ||||||

| m = 8 | Ac-(GPO)5GSIIMSSLP(GPO)4GY-NH2 | 2215 | 0.09 | 19.6 | 179e | 2.6, |

| α5(IV): 160-167 | 65.8 | |||||

| m = 9 | Ac-(GPO)5GEFYFDLRLK(GPO)4-NH2 | 1520 | 0.07 | 21.4, | f | 2.2, |

| α1(IV): 532–540 | 70.0 | 26.3 | ||||

| Control | (POG)10 | 4304 | 0.12 | 58.8h | 376h | 1.9 |

| Control | Ac-(GPO)8GG-NH2 | 3625 | 0.12 | 47.3g | 225 | 1.7 |

Sequence in 1-residue code (using O for Hyp), with interruption residue in bold. Sequence is followed by the source of the interruption (collagen type, chain, residue number).

Rpn is the ratio of the magnitude of the positive 225 nm peak to the negative 198 nm peak in the CD spectrum.19

Tm value determined from CD thermal transition, as described in Materials and Methods.

The observation that the observed molar calorimetric enthalpy value of 432 kJ mol−1 for this m = 5 peptide is higher than the 390 kJ mol−1 value for the control (POG)10 is likely to reflect its length (33 residue vs. 30 residue in control); and a contribution from blocked ends (an increase of ∼50–60 kJ mol−1 has been observed in other peptide sets). (unpublished observation).

This value was taken after initial solubilization of peptide with the 8-residue interruption before aggregate formation.

ΔHcal for the trimer to monomer transition could not be calculated because of multiple peaks.

Persikov et al.20

Persikov et al.21

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra, CD thermal transitions, differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), and dynamic light scattering (DLS) are carried out on this set of peptides to investigate the effect of interruptions of various lengths on triple-helix properties (Table I). Standard peptides containing only Gly-Pro-Hyp repeating sequences, (POG)10 and (GPO)8, are considered as controls.20,21,23 Peptides containing interruptions of seven residue or fewer in length are all fully soluble in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7, at a concentration of 1 mg mL−1 at low temperature. The two peptides with the longest interruptions (m = 8 and 9) showed some aggregation under these conditions, and a procedure of heating, cooling, and centrifugation was used to prepare a solution for physical chemical characterization (final concentration of 1 mg mL−1). The CD spectra for peptides in the set show the characteristic collagen triple-helical features, with a positive peak near 225 nm and a large negative peak around 198 nm (Supporting Information Fig. 1). The mean residue ellipticity value at 225 nm for the 5-residue interruption peptide (MRE225nm = 4035 deg cm2 dmol−1) is similar to that seen for control peptides, with somewhat lower values observed for peptides with shorter interruptions (3215–3700 deg cm2 dmol−1 for m = 1, 3, and 4). Markedly lower values are seen for the longer interruptions (1520–2465 deg cm2 dmol−1 for m = 6, 7, 8, and 9). The ratio of the positive to negative peak heights (Rpn) can be used as a measure of triple-helix content, with values close to 0.12 supporting a fully triple-helical structure.19 Rpn values are in the fully triple-helical range for peptides containing 1-, 3-, 4-, and 5-residue interruptions but are lower for the remaining peptides, suggesting that structures containing the longer interruptions are not completely triple helical (Table I).

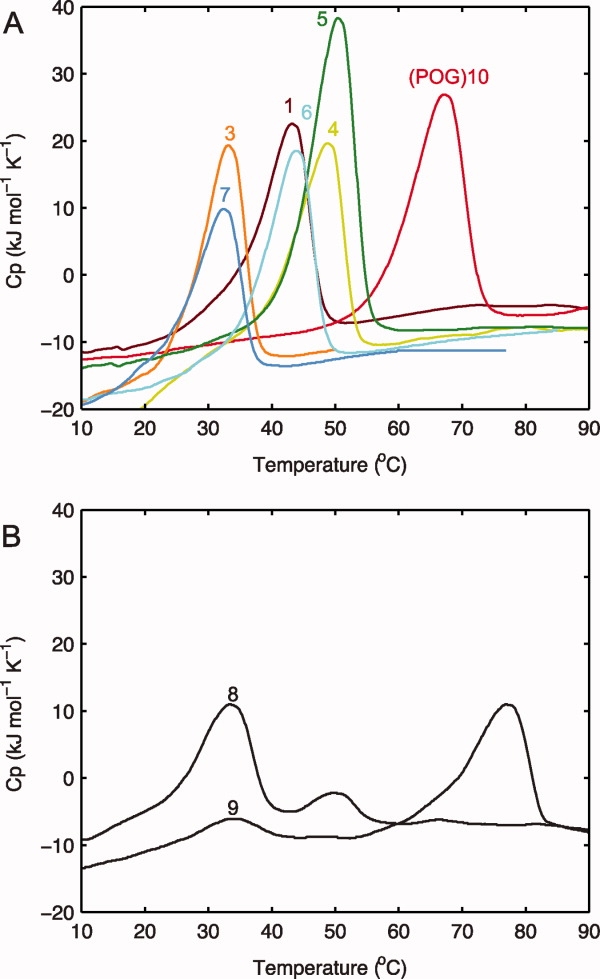

The presence of interruptions significantly decreases the thermal stability of all peptides as monitored by CD and DSC. The CD Tm values, obtained by monitoring the MRE225nm with increasing temperature, range from 41.2 to 19.1°C, significantly below the value for the (POG)10 peptide, 60.0°C (Table I, Supporting Information Fig. 2).20 The DSC profiles show a single transition for peptides with 1- to 7-residue interruptions and two transitions for peptides with 8- and 9-residue interruptions (Fig. 1). The calorimetric enthalpy values range from 179 to 432 kJ mol−1 [Table I; Fig. 1(A)], and all peptides except the 5-residue interruption peptide have values lower than the control (POG)10.

Figure 1.

A: Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) for peptides with interruptions of lengths 1–7 as defined in Table I, measuring excess molar heat capacity at a heating rate of 1°C min−1. The peptide without interruptions, (POG)10, is shown as a control. B: DSC of peptides with interruptions of 8 and 9 residues in length, (GPO)5GSIIMSSLP(GPO)4GY and (GPO)5GEFYFDLRLK(GPO)4. The thermal transition on DSC occurs 8–10°C higher than on CD because of the difference in heating rate under nonequilibrium conditions.21

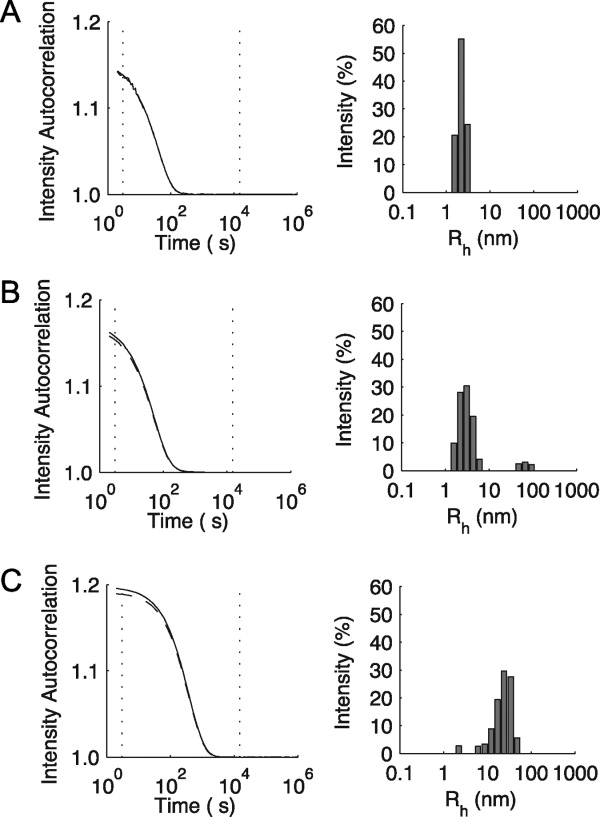

DLS studies show that all of the peptides with interruptions have a hydrodynamic radius (Rh) in the range of 1.9–2.2 nm, except for the 8-residue interruption, which is a little higher (2.6 nm). These values are close to that seen for the control, (POG)10 (Rh = 1.9), which adopts a rod-like structure (Table I). This suggests that the set of peptides containing interruption sequences have a size and shape similar to that of a standard rod-like triple-helix molecule.

Characterization of aggregates formed by peptides containing 8- and 9-residue interruptions

Although the peptides with interruptions of lengths 1–7 are all readily soluble in PBS at 5°C at a concentration of 1 mg mL−1, the peptide containing the 8-residue interruption (GPO)5GSIIMSSLP(GPO)4GY and the peptide containing the 9-residue interruption (GPO)5GEFYFDLRLK(GPO)4 show insolubility and self-association to visible aggregates. For these two peptides, a procedure of heating to solubilize the peptide, cooling to 5°C, and centrifugation leads to a clear supernatant (1 mg mL−1) that is used for the solution physical chemical characterization described above.

After incubation at 5°C for more than 1 week, visible aggregates are observed, and species larger than triple helices can be seen by a variety of techniques. The DSC profiles of the (GPO)5GSIIMSSLP(GPO)4GY and (GPO)5GEFYFDLRLK(GPO)4 peptides both show two peaks [Fig. 1(B)]. The lower stability peak is seen near the position expected for denaturation of the triple-helix at this heating rate (∼33°C),21 whereas the higher temperature peak (50.0°C for m = 8 and 76.9°C for m = 9) is likely to correspond to the denaturation of an aggregated form, based on previous studies of triple-helical peptides.24 The reverse DSC, in which the temperature is lowered at the same rate, has only one negative peak at low temperature reflecting triple-helix refolding (data not shown) but lacks a high-temperature peak indicative of aggregate formation.24

DLS studies of the peptides containing 8- and 9-residue interruptions also indicate the presence of both triple-helix species and higher order structures in solution (Fig. 2). A species with a hydrodynamic radius typical of a single triple-helix is seen (Rh = 2.6 nm for m = 8 and Rh = 2.2 nm for m = 9) together with a larger species (Rh = 65.8 nm for m = 8 and Rh = 26.3 nm for m = 9). In contrast, the nonaggregating 7-residue interruption peptide, (GPO)5GEVLGAQP(GPO)4GY, shows only a single species with Rh = 2.1 nm. Although both the 8- and 9-residue interruption peptides show higher order structure formation at a concentration of 1 mg mL−1 in PBS, the latter peptide demonstrates a much greater tendency toward aggregation with a faster time course and a greater relative size of the aggregate peak compared with the triple-helical peak on both DSC and DLS.

Figure 2.

Dynamic light scattering analysis for peptides containing interruptions. A: Peptide containing the 7-residue interruption, (GPO)5GEVLGAQP(GPO)4GY. B: Peptide containing the 8-residue interruption, (GPO)5GSIIMSSLP(GPO)4GY. C: Peptide containing the 9-residue interruption, (GPO)5GEFYFDLRLK(GPO)4. For each peptide, the correlation curve (—) and regularization fit (----) are shown on the left. The intensity distribution of hydrodynamic radii is shown on the right. It should be noted that the intensity depends on both the size of the species and the abundance of molecules of that size. All peptides were studied at a concentration of 1 mg mL−1 in PBS, following heating the samples to 90 °C, incubation at 5 °C for 2 weeks, and filtered before experimentation.

A short peptide consisting of the 9-residue interruption without a triple-helical context

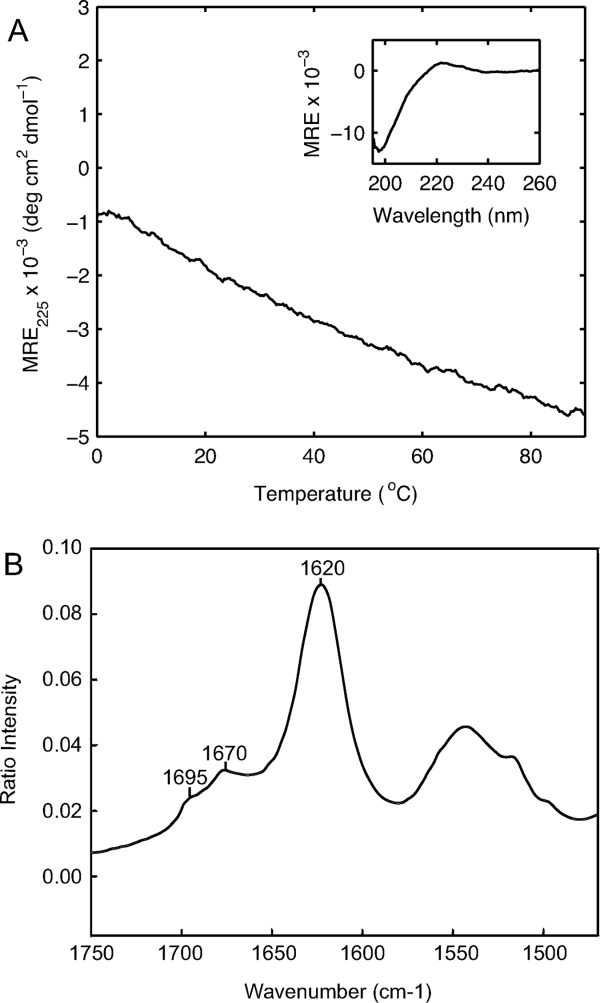

To explore whether the residue within the interruption can adopt an independent conformation or play a role in the observed aggregation, a peptide was designed to contain the 9-residue interruption sequence alone without Gly-Xaa-Yaa repeats: Ac-EFYFDLRLK-NH2. This peptide shows a polyproline-II-like CD spectrum at low temperature (positive peak at 221.5 nm and negative peak at 197.5 nm) [Fig. 3(A), inset]. Heating of the peptide as monitored by CD shows only a linear change in ellipticity, with no sign of a cooperative thermal transition [Fig. 3(A)], and DSC shows no thermal transition as well (data not shown). This short EFYFDLRLK peptide shows slow irreversible aggregation at low temperature similar to that seen for the peptide with the same sequence flanked by Gly-Pro-Hyp repeats. The Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrum obtained by attenuated total reflectance (ATR) on the aggregated EFYFDLRLK peptide in the solid state shows a spectrum in the amide I region characteristic of an antiparallel β-sheet [Fig. 3(B)].

Figure 3.

Conformational studies of EFYFDLRLK peptide. A: Temperature-induced denaturation as monitored by CD signal at 225 nm (heating rate ∼0.1°C min−1, c = 0.1 mg mL−1, PBS). Inset, CD spectrum at 0°C. B: Fourier transform infrared spectrum in the amide I region for precipitated aggregates formed by EFYFDLRLK peptide, using attenuated total reflectance.

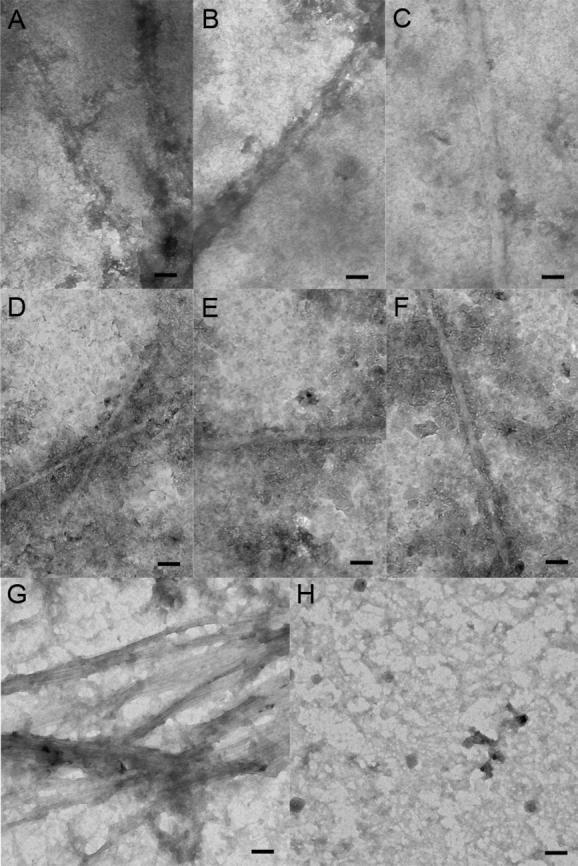

Aggregate morphology

The aggregates formed model peptides (GPO)5GSIIMSSLP(GPO)4GY [Fig. 4(A–C)] and (GPO)5GEFYFDLRLK(GPO)4 [Fig. 4(D–F)] appear fibrous when examined by electron microscopy. None of the collagen model peptides (GPO)5GSIIMSSLP(GPO)4GY and (GPO)5GEFYFDLRLK(GPO)4 appear fibrous when examined by electron microscopy [Fig. 4(A–C), 4(D–F)]. None of the collagen model peptides with shorter interruptions studied here show aggregates by any method, and an electron micrograph of the 7-residue interruption peptide, (GPO)5GEVLGAQP(GPO)4GY, does not display any fibers or other aggregated forms [Fig. 4(H)]. Electron microscopy of the EFYFDLRLK peptide, containing only the interruption sequence, shows an abundance of straight fibers [Fig. 4(G)].

Figure 4.

Electron micrograph of insoluble material formed by peptides. A–C: Aggregates of peptide containing 8-residue interruption, (GPO)5GSIIMSSLP(GPO)4GY. D–F. Aggregates of peptide containing 9-residue interruption, (GPO)5GEFYFDLRLK(GPO)4. G: Aggregates of EFYFDLRLK peptide. H: Solution of peptide containing 7-residue interruption, (GPO)5GEVLGAQP(GPO)4GY, which showed no aggregation. Peptides with interruptions were incubated at 5°C for 1 month after heating to 90°C (c = 1 mg mL−1, PBS). Bar represents 100 nm.

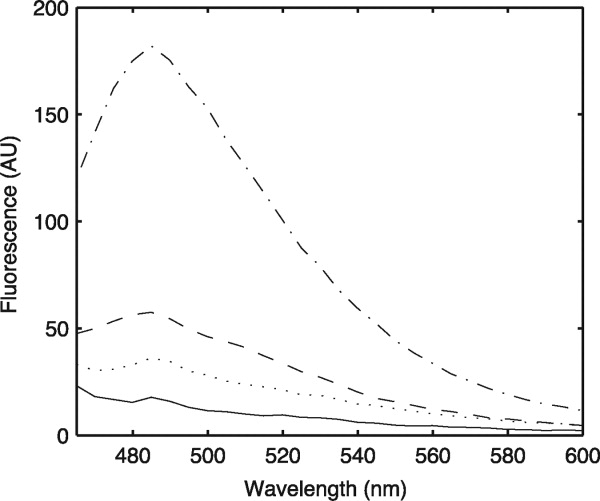

Because of the amyloid-like appearance of the fibrils formed, the aggregates were tested for thioflavin T (ThT) binding using a standard fluorescence assay. The (GPO)5GSIIMSSLP(GPO)4GY, (GPO)5GEFYFDLRLK(GPO)4, and EFYFDLRLK peptide all bind to ThT (Fig. 5), but the nonaggregating 7-residue interruption peptide, (GPO)5GEVLGAQP(GPO)4GY, does not. The observation that ThT binds to the aggregates of peptides with 8- and 9-residue interruptions, as well as the EFYFDLRLK peptide, is consistent with a recent publication indicating that ThT binds to both collagen fibrils and amyloid fibrils.25

Figure 5.

Fluorescence of Thioflavin T upon incubation with peptide aggregates. Peptide solutions were mixed with Thioflavin T, and fluorescence emission spectra were recorded upon excitation at 450 nm. Emission spectra for 8-residue interruption peptide (GPO)5GSIIMSSLP(GPO)4GY (····), 9-residue interruption peptide (GPO)5GEFYFDLRLK(GPO)4 (-·-·-·), EFYFDLRLK peptide (----), and Thioflavin T alone (—) are shown here. The 7-residue interruption peptide, (GPO)5GEVLGAQP(GPO)4GY, had a spectrum nearly identical to that of Thioflavin T alone and is not shown.

Computational analysis of collagen interruptions

Aggregation of the triple-helical peptides with the 8- and 9-residue interruptions and the formation of antiparallel β-sheet fibrils by the EFYFDLRLK peptide prompted an analysis of the amyloidogenic potential of all interruption sequences in nonfibrillar collagens. Analysis of the 35 distinct polypeptide chains that constitute the 21 types of human nonfibrillar collagens identified 374 interruptions within or between triple-helical (Gly-Xaa-Yaa)n sequences. Of these 374 interruptions, 75% are nine residue or less in length (Supporting Information Fig. 3), falling within the size range modeled by peptides in this study. The residue present within interruptions differ significantly from the residue within the (Gly-Xaa-Yaa)n repeating regions (P ≤ 0.0001 in a two-sample Z-test), most notably because of their higher content of hydrophobic residue (32%) (Supporting Information Fig. 4).

To explore aggregation propensity, the TANGO sequence analysis program is applied to all 374 interruption sequences (http://tango.crg.es). Under physiological conditions, a total of 33 interruptions show an aggregation score greater than 0, suggesting a significant propensity for cross-β aggregation (Table II). Aggregation is predicted for 1% of interruption sequences containing fewer than eight residue, 17% of sequences eight or nine residue in length, and 27% of sequences greater than nine residue in length. The shortest interruptions that are predicted to have cross-β aggregation were five residue in length.

Table II.

List of Sequences Within and Between (Gly-Xaa-Yaa)n Domains That Show Significant Cross-β Aggregation Propensity, as Predicted Using the Program TANGO

| Sequence | Collagen | Length | Aggregation propensitya |

|---|---|---|---|

| NSVFILGAVK | α4(IV) | 10 | 600.1 |

| TVIVTLTGPDNRTDLK | α3(IV) | 16 | 481.8 |

| PVVYVSEQDGSVLSVP | α1(XVIII) | 16 | 335.1 |

| PVTTITGETFDYSELASHVVSYLRTSGYGV | α1(XVII) | 60 | 306.2 |

| SLFSSSISSEDILAVLQRDDVRQYLRQYLM | |||

| IPADAVSFEEIKKYINQEVLRIFEERMAVFL | α1(XIX) | 46 | 193.4 |

| SQLKLPAAMLAAQAY | |||

| ATKIIDYNGNLHEALQRITTLTVT | α1(XXV) | 24 | 69.4 |

| ESPSMETLRRLIQEELGKQLETRL | α1(XXII) | 40 | 66.9 |

| EPQSLATLYQLVSQACESAIQTHVSKFDSF | α1(XX) | 52 | 61.2 |

| HENTRPPMPILEQKLEPGTEPL | |||

| EMAIISQK | α4(IV) | 8 | 55.8 |

| ALATYAAENSDSFRSELISYLTSPDVRSFIV | α1(XVII) | 31 | 52.7 |

| SSVIYCSV | α4(IV) | 8 | 33.1 |

| PSPNSPQGALYSLQPPTDKDNGDSRLASAI | α1(XXVI) | 36 | 30.3 |

| VDTVLA | |||

| PPAILGAAVALP | α1(XV) | 12 | 27.4 |

| EFYFDLRLKb | α1(IV) | 9 | 26.7 |

| NVWSSISVEDLSSYLHTAGLSFIP | α1(XVII) | 24 | 20.3 |

| TSYEELLSLLRGSEFR | α1(XVII) | 16 | 15.7 |

| RDATDQHIVDVALKMLQEQLAEVAVSAK | α2(IX) | 32 | 9.8 |

| REAL | |||

| DLQSQAMVRSVARQVCEQLIQSHMARYT | α1(XIV) | 45 | 7.9 |

| AILNQIPSHSSSIRTVQ | |||

| EPILSTIQ | α6(IV) | 8 | 6.6 |

| ISKVFSAYSNVTADLMDFFQTYGAIQ | α1(XVII) | 26 | 5 |

| LDNCAQCFLSLERPRAEEARGDNSE | α1(XVI) | 25 | 4.9 |

| SIIMSSLPb | α5(IV) | 8 | 2.9 |

| HIKVLSNSLINITHGFMNFSDIPELV | α1(XV) | 26 | 2.3 |

| ADFAGDLDYNELAVRVSESMQRQGLLQG | α1(XVII) | 34 | 2 |

| MAYTVQ | |||

| ESASDSLQESLAQLIVEP | α1(XXIII) | 18 | 2 |

| DGSLLSLDYAELSSRILSYMSSSGISI | α1(XVII) | 27 | 1..9 |

| LALTV | α5(VI) | 5 | 1.6 |

| LSSLLSPGDINLLAKDVCNDCPP | α1(XXII) | 23 | 1.6 |

| EYPHRECLSSMPAALRSSQIIALKLLPLLNS | α1(XIII) | 55 | 1.4 |

| VRLAPPPVIKRRTFQGEQSQASIQ | |||

| DMVNYDEIKRFIRQEIIKMFDERMAYYTSR | α1(XVI) | 41 | 1.3 |

| MQFPMEMAAAP | |||

| PFWSTARSAD | α1(XVIII) | 10 | 1 |

| IVIGT | α1(IV) | 5 | 0.8 |

| IPSDTLHPIIAPTGVTFHPDQYK | α2(IV) | 23 | 0.8 |

Calculated at T = 310.15 K, pH = 7, Ionic strength = 0.15M.

8- and 9-residue interruption sequences incorporated into peptides studied experimentally (as shown in bold).

For the sequences included in the model peptides studied here, TANGO predicts that the 9- and 8-residue interruption sequences (EFYFDLRLK and SIIMSSLP) have a significant propensity for cross-β aggregation, whereas the 1- to 7-residue interruption sequences studied do not (Table II). The predictions are consistent with the experimental results. The TANGO analysis suggests aggregation is not a general property of all 8- and 9-residue interruptions but is related to the specific sequences chosen for these peptides. The alternation of hydrophobic and polar residue in the 9-residue EFYFDLRLK sequence is likely to contribute to its high propensity for β-sheet and amyloid fibrils.26

Discussion

The structural basis for biological roles of interruptions is investigated here through a set of triple-helical peptides containing insertions of 1–9 residue in length between fixed (Gly-Pro-Hyp)n sequences. Interruption sites in nonfibrillar collagens may adopt unique conformations recognized by enzymes and cell receptors. In Type X collagen, two 4-residue interruption sequences were shown to be targets for matrix metalloproteinases,27 and cleavage at a 12-residue interruption site in Type IV collagen was shown to create a peptide important for metamorphosis in Drosophila melanogaster.28 In addition, the 9-residue interruption of the α1 chain of Type IV collagen, EFYFDLRLK, has been shown to bind to α3β1 integrin in ovarian carcinoma and melanoma cells.22 The structural studies on the peptides reported here support modifications of triple-helix features and stability at interruption sites that could serve as recognition sites for degradation or binding.

All peptides in this set show evidence of collagen triple-helix structure in solution, but with some conformational distortion and decreased thermal stability. In the range of lengths studied here, the peptides containing longer interruptions (m = 6, 7, 8, and 9) showed lower MRE225nm values, lower Rpn values, and decreased calorimetric enthalpies compared with the peptides containing the shorter interruptions (m = 1, 3, 4, and 5). It is likely that the shorter interruption peptides contain very localized perturbation of dihedral angles and hydrogen bonding as seen in molecular structures of peptides with 1- and 4-residue interruptions15–17 and with a Gly to Ala replacement equivalent to a 5-residue interruption.29 The increased conformational perturbation associated with longer interruptions could arise from greater deviation from the standard triple-helix or disruption of a larger segment of the molecule. The effect of an interruption is also likely to depend on its particular sequence, but the presence of consensus features for a given length of interruption supports some common structural consequences independent of sequence.17,18

In this set, the 5-residue interruption peptide stands out as having the highest MRE225nm, Rpn value, thermal stability, and calorimetric enthalpy, indicating that the distortion is not a simple function of length. The 5-residue interruption has a sequence equivalent to a Gly to Ala replacement, which suggests that preservation of the phase of the repeating tripeptide pattern could be one important factor in stability. Another factor in the high stability of the 5-residue interruption peptide could be the presence of Ala, a small residue, in the position where Gly is expected. Gly to Ala replacements are underrepresented in collagen diseases,30,31 and several fibril-forming collagens from annelid worms and molluscs contain a single Gly to Ala substitution within an otherwise perfect Gly-Xaa-Yaa repeat.32–35

Some evidence suggests that interruptions may create flexibility or kinks. Electron microscopy shows bends within individual Types IV and VII collagen molecules36–38 and the C1q triple-helix domain.39 However, the interruption peptides studied here did not demonstrate the significant changes in hydrodynamic radii compared with controls that might be expected from major changes in the rod-like structure of the standard triple-helix.

A new potential role for interruptions is suggested by the observed aggregation of peptides. Although peptides with interruptions of 1–7 residue in length form soluble triple-helical molecules with perturbed structure and stability, the two peptides containing the 8- and 9-residue interruptions have a high propensity to assemble into fibrillar structures. The characteristic features of this aggregation include its occurrence at low temperatures (5°C) and relatively low concentrations (∼300 μM) and its slow kinetics over a period of days. The aggregation of peptides with interruptions contrasts with the self-association of peptides containing perfect (Gly-Xaa-Yaa)n sequences, which requires high concentrations and higher temperatures and occurs over a period of minutes to hours.24,40 Although the aggregates formed by peptides with uninterrupted (Gly-Xaa-Yaa)n sequences are likely to be composed of overlapping triple-helical molecules,24,40,41 the nature of the fibrillar material formed from peptides containing both (Gly-Pro-Hyp)n sequences and β-aggregation-prone interruption sequences is not known as the high content of imino acids and Gly residue is expected disfavor β-sheet formation. The data reported here suggest that some natural interruptions may increase the propensity of triple-helices to self-associate and thus could play a previously unsuspected role in collagen molecular self-association. A number of nonfibrillar collagens show molecular association in tissue structures that could be influenced by interruptions. For example, the Type IV basement membrane collagen network shows lateral association of intertwined triple helices,42,43 and Type VII collagen forms anchoring fibrils in the skin that consist of large arrays of antiparallel dimers.11

The propensity toward aggregation inherent in some interruption sequences of nonfibrillar collagens could be a factor in recent reports of interactions between collagens and amyloid.44–49 Type XXV collagen (CLAC) was discovered as a component of Alzheimer amyloid plaque,45 and its amino acid sequence contains two long interruption sequences and three short imperfections within its triple-helix domain. There is evidence that Type XXV collagen inhibits amyloid fibril elongation,46,49 and that a highly hydrophobic 8-residue sequence within the large 26-residue interruption may be involved in this inhibition.48 The finding reported here that certain collagen interruption sequences can form amyloid-like fibrils may stimulate further investigations into the role of collagen in amyloid diseases.

Materials and Methods

Peptides

All peptides used in this study were synthesized by Tufts University Core Facility (Boston, MA) (Table I). Peptides were acetylated at their N-termini and amidated at their C-termini, and a Tyr was included at the C-terminus for accurate concentration determination (molar extinction coefficient = 1400 M−1 cm−1). Peptides were purified on a Shimadzu reverse-phased high-pressure liquid chromatography system, and their identities were confirmed by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time of flight mass spectroscopy. All peptides were dissolved in PBS (20 mM sodium phosphate buffer with 150 mM NaCl, pH 7).

Each peptide was designed to model an interruption found in a human collagen chain. The sequences of interruptions of length 1, 4, 6, 7, 8, and 9 are from interruptions found in one of the six chains of Type IV collagen (Table I). Although these interruptions occur in a heterotrimeric context in Type IV collagen, the peptide models are homotrimers. The sequences for interruptions of lengths 3 and 5 were taken from Types VII and XIX, respectively, which are homotrimers (Table I). Each of the peptides was designed to contain the interruption surrounded by five Gly-Pro-Hyp repeats on the N-terminal side and four Gly-Pro-Hyp repeats on the C-terminal side. In the 5-residue interruption sequence, PPALO, Hyp is incorporated in the last position rather than Pro, as Hyp is found in that position in two similar 5-residue interruptions in Type IV collagen.50

Here, we define the length of an interruption as the number of residue between Gly-Xaa-Yaa-Gly sequences, although it is not known whether repeat sequences adjacent to or within the interruption will adopt a standard or altered triple-helix structure. An alternate definition seen in the literature assumes that every Gly-Xaa-Yaa triplet belongs to a triple-helix domain, not an interruption sequence. According to our notation, the sequence GAKGEPGEFYFDLRLKGDKGDP in the α1(IV) chain has a 9-residue interruption EFYFDLRLK, but the alternate definition would consider this to be a 7-residue interruption YFDLRLK.

Circular dichroism spectroscopy

CD spectra were recorded on an Aviv model 62DS spectrophotometer equipped with a Peltier temperature controller (Aviv Biomedical, Lakewood, NJ). Cuvettes with 1-mm path length were used. Peptide solutions (1 mg mL−1, PBS) were equilibrated for a minimum of 48 h at 5°C before measurement. For wavelength spectra, measurements were collected in 0.5 nm steps with 4 s averaging time and repeated three times. The ratio of positive to negative peaks (Rpn) was calculated as described by Feng et al. from the wavelength scans of 0.1 mg mL−1 solutions recorded at 5°C.19 For temperature-induced denaturation, the temperature was increased at an average rate of 0.1°C min−1, and ellipticity at 225 nm was monitored. The melting temperature (Tm) was calculated as the temperature at which the fraction folded was equal to 0.5 when fit to a trimer–monomer transition. It should be noted that the melting curves obtained under the above conditions reflect a nonequilibrium state, although it is close to equilibrium.21

Differential scanning calorimetry

DSC experiments were carried out on a NANO DSC II Model 6100 (Calorimetry Sciences, Lindon, UT). The peptide solutions were dialyzed in PBS at 5°C and equilibrated for a minimum of 48 h at 5°C before measurements. Samples were heated at a constant rate of 1°C min−1. The calorimetric enthalpy of unfolding (ΔHcal) was calculated from the first scan because the scans were not reversible upon cooling.

Dynamic light scattering

DLS was carried out on a DynaPro Titan instrument (Wyatt Technology, Santa Barbara, CA) equipped with a temperature controller. Peptide solutions (1 mg mL−1, PBS) were kept for a minimum of 1 week at 5°C. All samples were filtered through a 0.1-μm Whatman Anotop filter before measurement. To obtain the hydrodynamic radii, the intensity autocorrelation functions were analyzed using the Dynamics software (Wyatt Technology). A viscosity value of 1.019 was used for PBS.

Peptide aggregation and electron microscopy

To prepare clear 1 mg mL−1 solutions of the 8- and 9-residue interruption peptides and the EFYFDLRLK peptide, a 1.25 mg mL−1 preparation of peptide in PBS was heated to 90°C for 30 min, cooled to 5°C, and centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 rpm at 5°C. The supernatant obtained from this procedure for the 8-residue interruption peptide was immediately used for physical chemical characterization, because after a week at 5°C, aggregates formed. For electron microscopy, the precipitates were incubated at 5°C for 1 month and then resuspended. Samples were negatively stained with 0.1% uranyl acetate for 5 s. Transmission electron microscopy was performed on a Phillips 420 instrument.

Attenuated total reflection–infrared spectroscopy

Solutions containing peptide aggregates were dialyzed against distilled water and centrifuged to isolate large precipitates. The precipitate was resuspended and lyophilized. The FTIR spectra of lyophilized peptides were obtained using a single-bounce ATR attachment on a Nicolet 6700 Analytical FTIR Spectrophotometer in the laboratory of Dr. Richard Mendelsohn.

Thioflavin T binding

Fluorescence measurements were performed using a Cary Eclipse instrument with a 1-cm plastic cuvette. The sample was excited at 450 nm, and emission spectra were recorded from 460 to 600 nm. Thioflavin T was added to a final concentration of 5 nM to a 1 mg mL−1 solution of peptide in PBS, and spectra were recorded after 30 min at 5°C.

Sequence analysis

Sequences for chains of all human nonfibrillar collagen types were obtained from UniProt: Types IV (chains 1–6), VI (chains 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6), VII, VIII (chains 1 and 2), IX (chains 1–3), X, XII, XIII, XIV, XV, XVI, XVII, XVIII, XIX, XX, XXI, XXII, XXIII, XXIV, XXV, XXVI, XXVII, and XXVIII.51 Interruptions were identified systematically by searching for Gly-Xaa-Yaa-Gly units. Any residue that were not part of such units were considered part of an interruption. Cross-β aggregation predictions were made using the online program TANGO at a temperature of 37°C, pH 7, and 0.15M ionic strength.52–54

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to Dr. Richard Mendelsohn and Carol Flach (Chemistry Department, Rutgers University, Newark, NJ) for performing the ATR experiments. They appreciate the assistance of Jeremy Pronchik and Jason Giurleo with ThT binding assays. They acknowledge peptide purification done by Teresita Silva, assistance with electron microscopy by Raj Patel, and computational work performed by Marina Girgis. They thank Dr. Michael Hecht for valuable discussion and Dr. Michael Liebowitz for the suggestion to perform amyloid predictions on the interruption sequences.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- ΔHcal

calorimetric enthalpy

- ATR

attenuated total reflectance

- CD

circular dichroism

- DLS

dynamic light scattering

- DSC

differential scanning calorimetry

- FTIR

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

- MRE225nm

mean residue ellipticity at 225 nm

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- Rh

hydrodynamic radius

- Rpn

ratio of magnitude of positive 225-nm CD peak to negative 198-nm peak

- Standard amino acids codes are used

with the addition of hydroxyproline designated by Hyp (3-letter code) and O (1-letter code)

- ThT

Thioflavin T

- Tm

melting temperature.

References

- 1.Ramachandran GN, Kartha G. Structure of collagen. Nature. 1955;176:593–595. doi: 10.1038/176593a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rich A, Crick FH. The molecular structure of collagen. J Mol Biol. 1961;3:483–506. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(61)80016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shoulders MD, Raines RT. Collagen structure and stability. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:929–958. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.032207.120833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kielty C, Grant M. The collagen family: structure, assembly and organization in the extracellular matrix. In: Royce PM, Steinmann BU, editors. Connective tissue and its heritable disorders: molecular, genetic, and medical aspects. New York: Wiley-Liss; 2002. pp. 159–222. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Myllyharju J, Kivirikko KI. Collagens, modifying enzymes and their mutations in humans, flies and worms. Trends Genet. 2004;20:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ricard-Blum S, Ruggiero F. The collagen superfamily: from the extracellular matrix to the cell membrane. Pathol Biol (Paris) 2005;53:430–442. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2004.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Veit G, Kobbe B, Keene DR, Paulsson M, Koch M, Wagener R. Collagen XXVIII, a novel von Willebrand factor A domain-containing protein with many imperfections in the collagenous domain. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:3494–3504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509333200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boot-Handford RP, Tuckwell DS, Plumb DA, Rock CF, Poulsom R. A novel and highly conserved collagen (proα1(XXVII)) with a unique expression pattern and unusual molecular characteristic establishes a new clade within the vertebrate fibrillar collagen family. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31067–31077. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212889200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koch M, Laub F, Zhou P, Hahn RA, Tanaka S, Burgeson RE, Gerecke DR, Ramirez F, Gordon MK. Collagen XXIV, a vertebrate fibrillar collagen with structural features of invertebrate collagens: selective expression in developing cornea and bone. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:43236–43244. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302112200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hudson BG, Tryggvason K, Sundaramoorthy M, Neilson EG. Alport's syndrome, Goodpasture's syndrome, and type IV collagen. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2543–2556. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burgeson RE. Type VII collagen, anchoring fibrils, and epidermolysis bullosa. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;101:252–255. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12365129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brodsky B, Persikov AV. Molecular structure of the collagen triple helix. Adv Protein Chem. 2005;70:301–339. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(05)70009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jenkins CL, Raines RT. Insights on the conformational stability of collagen. Nat Prod Rep. 2002;19:49–59. doi: 10.1039/a903001h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Renner C, Sacca B, Moroder L. Synthetic heterotrimeric collagen peptides as mimics of cell adhesion sites of the basement membrane. Biopolymers. 2004;76:34–47. doi: 10.1002/bip.10569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bella J, Liu J, Kramer R, Brodsky B, Berman HM. Conformational effects of Gly-X-Gly interruptions in the collagen triple helix. J Mol Biol. 2006;362:298–311. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y, Brodsky B, Baum J. NMR shows hydrophobic interactions replace glycine packing in the triple helix at a natural break in the (Gly-X-Y)n repeat. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:22699–22706. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702910200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thiagarajan G, Li Y, Mohs A, Strafaci C, Popiel M, Baum J, Brodsky B. Common interruptions in the repeating tripeptide sequence of non-fibrillar collagens: sequence analysis and structural studies on triple-helix peptide models. J Mol Biol. 2008;376:736–748. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.11.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohs A, Popiel M, Li Y, Baum J, Brodsky B. Conformational features of a natural break in the type IV collagen Gly-X-Y repeat. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17197–17202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601763200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng Y, Melacini G, Taulane JP, Goodman M. Collagen-based structures containing the peptoid residue N-isobutylglycine (Nleu): synthesis and biophysical studies of Gly-Pro-Nleu sequences by circular dichroism, ultraviolet absorbance, and optical rotation. Biopolymers. 1996;39:859–872. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(199612)39:6%3C859::AID-BIP10%3E3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Persikov AV, Ramshaw JA, Brodsky B. Prediction of collagen stability from amino acid sequence. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:19343–19349. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501657200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Persikov AV, Xu Y, Brodsky B. Equilibrium thermal transitions of collagen model peptides. Protein Sci. 2004;13:893–902. doi: 10.1110/ps.03501704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miles AJ, Knutson JR, Skubitz AP, Furcht LT, McCarthy JB, Fields GB. A peptide model of basement membrane collagen alpha 1 (IV) 531-543 binds the alpha 3 beta 1 integrin. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29047–29050. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.49.29047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berisio R, Vitagliano L, Mazzarella L, Zagari A. Crystal structure of a collagen-like polypeptide with repeating sequence Pro-Hyp-Gly at 1.4 A resolution: implications for collagen hydration. Biopolymers. 2000;56:8–13. doi: 10.1002/1097-0282(2000)56:1<8::AID-BIP1037>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kar K, Amin P, Bryan MA, Persikov AV, Mohs A, Wang YH, Brodsky B. Self-association of collagen triple helic peptides into higher order structures. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:33283–33290. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605747200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morimoto K, Kawabata K, Kunii S, Hamano K, Saito T, Tonomura B. Characterization of type I collagen fibril formation using thioflavin T fluorescent dye. J Biochem. 2009;145:677–684. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvp025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.West MW, Wang W, Patterson J, Mancias JD, Beasley JR, Hecht MH. De novo amyloid proteins from designed combinatorial libraries. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11211–11216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Welgus HG, Campbell EJ, Cury JD, Eisen AZ, Senior RM, Wilhelm SM, Goldberg GI. Neutral metalloproteinases produced by human mononuclear phagocytes. Enzyme profile, regulation, and expression during cellular development. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:1496–1502. doi: 10.1172/JCI114867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fessler LI, Condic ML, Nelson RE, Fessler JH, Fristrom JW. Site-specific cleavage of basement membrane collagen IV during Drosophila metamorphosis. Development. 1993;117:1061–1069. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.3.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bella J, Eaton M, Brodsky B, Berman HM. Crystal and molecular structure of a collagen-like peptide at 1.9 A resolution. Science. 1994;266:75–81. doi: 10.1126/science.7695699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marini JC, Forlino A, Cabral WA, Barnes AM, San Antonio JD, Milgrom S, Hyland JC, Korkko J, Prockop DJ, De Paepe A, Coucke P, Symoens S, Glorieux FH, Roughley PJ, Lund AM, Kuurila-Svahn K, Hartikka H, Cohn DH, Krakow D, Mottes M, Schwarze U, Chen D, Yang K, Kuslich C, Troendle J, Dalgleish R, Byers PH. Consortium for osteogenesis imperfecta mutations in the helical domain of type I collagen: regions rich in lethal mutations align with collagen binding sites for integrins and proteoglycans. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:209–221. doi: 10.1002/humu.20429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Persikov AV, Pillitteri RJ, Amin P, Schwarze U, Byers PH, Brodsky B. Stability related bias in residue replacing glycines within the collagen triple helix (Gly-Xaa-Yaa) in inherited connective tissue disorders. Hum Mutat. 2004;24:330–337. doi: 10.1002/humu.20091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gaill F, Hamraoui L, Sicot FX, Timpl R. Immunological properties and tissue localization of two different collagen types in annelid and vestimentifera species. Eur J Cell Biol. 1994;65:392–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mann K, Gaill F, Timpl R. Amino-acid sequence and cell-adhesion activity of a fibril-forming collagen from the tube worm Riftia pachyptila living at deep sea hydrothermal vents. Eur J Biochem. 1992;210:839–847. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sicot FX, Mesnage M, Masselot M, Exposito JY, Garrone R, Deutsch J, Gaill F. Molecular adaptation to an extreme environment: origin of the thermal stability of the pompeii worm collagen. J Mol Biol. 2000;302:811–820. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoneda C, Hirayama Y, Nakaya M, Matsubara Y, Irie S, Hatae K, Watabe S. The occurrence of two types of collagen proalpha-chain in the abalone Haliotis discus muscle. Eur J Biochem. 1999;261:714–721. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bachinger HP, Doege KJ, Petschek JP, Fessler LI, Fessler JH. Structural implications from an electronmicroscopic comparison of procollagen V with procollagen I, pC-collagen I, procollagen IV, and a Drosophila procollagen. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:14590–14592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hofmann H, Voss T, Kuhn K, Engel J. Localization of flexible sites in thread-like molecules from electron micrographs. Comparison of interstitial, basement membrane and intima collagens. J Mol Biol. 1984;172:325–343. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(84)80029-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bachinger HP, Morris NP, Lunstrum GP, Keene DR, Rosenbaum LM, Compton LA, Burgeson RE. The relationship of the biophysical and biochemical characteristics of type VII collagen to the function of anchoring fibrils. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:10095–10101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kilchherr E, Hofmann H, Steigemann W, Engel J. Structural model of the collagen-like region of C1q comprising the kink region and the fibre-like packing of the six triple helices. J Mol Biol. 1985;186:403–415. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kar K, Wang YH, Brodsky B. Sequence dependence of kinetics and morphology of collagen model peptide self-assembly into higher order structures. Protein Sci. 2008;17:1086–1095. doi: 10.1110/ps.083441308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cejas MA, Kinney WA, Chen C, Vinter JG, Almond HR, Jr, Balss KM, Maryanoff CA, Schmidt U, Breslav M, Mahan A, Lacy E, Maryanoff BE. Thrombogenic collagen-mimetic peptides: self-assembly of triple helix-based fibrils driven by hydrophobic interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:8513–8518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800291105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yurchenco PD, Ruben GC. Basement membrane structure in situ: evidence for lateral associations in the type IV collagen network. J Cell Biol. 1987;105:2559–2568. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.6.2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yurchenco PD, Ruben GC. Type IV collagen lateral associations in the EHS tumor matrix. Comparison with amniotic and in vitro networks. Am J Pathol. 1988;132:278–291. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheng JS, Dubal DB, Kim DH, Legleiter J, Cheng IH, Yu GQ, Tesseur I, Wyss-Coray T, Bonaldo P, Mucke L. Collagen VI protects neurons against Abeta toxicity. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:119–121. doi: 10.1038/nn.2240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hashimoto T, Wakabayashi T, Watanabe A, Kowa H, Hosoda R, Nakamura A, Kanazawa I, Arai T, Takio K, Mann DM, Iwatsubo T. CLAC: a novel Alzheimer amyloid plaque component derived from a transmembrane precursor, CLAC-P/collagen type XXV. EMBO J. 2002;21:1524–1534. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.7.1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Osada Y, Hashimoto T, Nishimura A, Matsuo Y, Wakabayashi T, Iwatsubo T. CLAC binds to amyloid beta peptides through the positively charged amino acid cluster within the collagenous domain 1 and inhibits formation of amyloid fibrils. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:8596–8605. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413340200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Relini A, Canale C, De Stefano S, Rolandi R, Giorgetti S, Stoppini M, Rossi A, Fogolari F, Corazza A, Esposito G, Gliozzi A, Bellotti V. Collagen plays an active role in the aggregation of beta2-microglobulin under physiopathological conditions of dialysis-related amyloidosis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:16521–16529. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513827200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Soderberg L, Kakuyama H, Moller A, Ito A, Winblad B, Tjernberg LO, Naslund J. Characterization of the Alzheimer's disease-associated CLAC protein and identification of an amyloid beta-peptide-binding site. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:1007–1015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403628200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kakuyama H, Soderberg L, Horigome K, Winblad B, Dahlqvist C, Naslund J, Tjernberg LO. CLAC binds to aggregated Abeta and Abeta fragments, and attenuates fibril elongation. Biochemistry. 2005;44:15602–15609. doi: 10.1021/bi051263e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwarz U, Schuppan D, Oberbaumer I, Glanville RW, Deutzmann R, Timpl R, Kuhn K. Structure of mouse type IV collagen. Amino-acid sequence of the C-terminal 511-residue-long triple-helical segment of the alpha 2(IV) chain and its comparison with the alpha 1(IV) chain. Eur J Biochem. 1986;157:49–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb09636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Consortium TU. The Universal Protein Resource (UniProt) Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D190–D195. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fernandez-Escamilla AM, Rousseau F, Schymkowitz J, Serrano L. Prediction of sequence-dependent and mutational effects on the aggregation of peptides and proteins. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:1302–1306. doi: 10.1038/nbt1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Linding R, Schymkowitz J, Rousseau F, Diella F, Serrano L. A comparative study of the relationship between protein structure and beta-aggregation in globular and intrinsically disordered proteins. J Mol Biol. 2004;342:345–353. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.06.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rousseau F, Schymkowitz J, Serrano L. Protein aggregation and amyloidosis: confusion of the kinds? Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2006;16:118–126. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]