This paper provides the first report of the effects of a physiological vasoconstrictor on cellular and subcellular Ca2+ signaling in retinal arterioles. It also reveals a previously unsuspected effect of vasopressin, which persistently upregulates Ca2+ stores, sparks, and oscillations after washout of the agonist. This effect may allow for long-term modulation of retinal blood flow by vasopressin, despite receptor desensitization.

Abstract

Purpose.

To investigate the effects of arginine vasopressin (AVP) on Ca2+ sparks and oscillations and on sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ content in retinal arteriolar myocytes.

Methods.

Fluo-4-loaded smooth muscle in intact segments of freshly isolated porcine retinal arteriole was imaged by confocal laser microscopy. SR Ca2+ store content was assessed by recording caffeine-induced Ca2+ transients with microfluorimetry and fura-2.

Results.

The frequencies of Ca2+ sparks and oscillations were increased both during exposure to, and 10 minutes after washout of AVP (10 nM). Caffeine transients were increased in amplitude 10 and 90 minutes after a 3-minute application of AVP. Both AVP-induced Ca2+ transients and the enhancement of caffeine responses after AVP washout were inhibited by SR 49059, a V1a receptor blocker. Forskolin, an activator of adenylyl cyclase, also persistently enhanced caffeine transients. Rp-8-HA-cAMPS, a membrane-permeant PKA inhibitor, prevented enhancement of caffeine transients by both AVP and forskolin. Forskolin, but not AVP, produced a reversible, Rp-8-HA-cAMPS insensitive reduction in basal [Ca2+]i.

Conclusions.

AVP activates a cAMP/PKA-dependent pathway via V1a receptors in retinal arteriolar smooth muscle. This effect persistently increases SR Ca2+ loading, upregulating Ca2+ sparks and oscillations, and may favor prolonged agonist activity despite receptor desensitization.

Modulation of arteriole resistance plays a central role in the control of regional blood flow and capillary pressure in the retina (see recent review in Ref. 1). To understand how flow is regulated to meet local needs, we must understand Ca2+ signaling within the smooth muscle of these vessels, since intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+i]) is a key regulator of contraction and thus of constriction in ocular vessels (reviewed in Ref. 2). Retinal arterioles are not autonomically innervated,3,4 and modulation of tone depends on local control mechanisms, such as those responsible for autoregulation of retinal blood flow in the face of changes in blood pressure or metabolic demand.5,6 Vasopressin, which constricts retinal arterioles in vitro,7 may play a role in such control. The endocrine actions of circulating vasopressin in the control of renal H2O reabsorption and vascular tone are well known (see reviews in Refs. 8, 9). However, locally released vasopressin acts as a paracrine signal within the brain itself.10 Vasopressin has been detected in rat retina,11 where it is localized to the ganglion cell layer close to the inner retinal vessels.12 It seems possible, therefore, that local release of vasopressin would contribute to retinal vascular tone. Retinal vasopressin levels are elevated during periods of exposure to light, when total retinal metabolism is reduced.11,13 The vasoconstrictor action of vasopressin may therefore help explain how this change in metabolic need is coupled to a reduction in retinal blood flow.14

Arginine vasopressin (AVP) stimulates a transient increase in smooth muscle intracellular [Ca2+]i and vessel constriction when applied externally to retinal arteriole segments.7 In common with many other vascular preparations, this response desensitizes in pig (though not in rat) retinal vessels.1,15,16 We have reported that myocytes in freshly isolated segments of rat retinal arterioles generate asynchronous Ca2+ sparks and oscillations.17,18 Brief Ca2+ sparks summate to produce the more prolonged oscillations that are associated with muscle contraction, which leads us to propose that Ca2+ sparks are excitatory, proconstrictor events in retinal arterioles, rather than prodilatory, as in larger arteries.19 The purpose of the present study was to characterize the effects of AVP, a physiological vasoconstrictor, on Ca2+ sparks and oscillations in pig retinal arteriolar myocytes. These asynchronous, phasic, cellular and subcellular signaling events were increased in frequency both during application of AVP and 10 minutes after washout. SR Ca2+ loading was increased up to 90 minutes after AVP exposure, by a cAMP, protein kinase A (PKA)–dependent mechanism. These novel findings suggest that local or circulating AVP had prolonged effects on retinal vascular resistance, despite receptor desensitization.

Materials and Methods

Arteriole Preparation

Pigs were humanely killed at a registered slaughterhouse in compliance with the ethical and legal requirements specified by the Welfare of Animals (Slaughter or Killing) Regulations (Northern Ireland) 1996. The eyes were transported in low-Ca2+ solution at 1°C. The retinas were removed and the arterioles mechanically isolated according to a published method.7,17 The retinas were triturated in low-Ca2+ Hanks' solution, centrifuged, washed with low-Ca2+ medium, and centrifuged again. Vascular fragments were then incubated for 2 hours with the relevant Ca2+ indicator in low-Ca2+ solution. Arteriole segments (outer diameter, 30–100 μm) were anchored in position with tungsten wire slips and superfused with normal Hanks' solution at 37°C.

Ca2+ Imaging

High-speed Ca2+ imaging was performed, as described elsewhere.17 Retinal arterioles were incubated with 10 μM fluo-4 AM and imaged with a confocal scanning laser microscope (model MR-A1; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), mounted on an inverted microscope (Eclipse TE300; Nikon Instruments, Tokyo, Japan, with a PlanApo, ×60, 1.4 NA, oil-immersion objective). The vessels were excited at 488 nm, and emitted light was filtered (530–560 nm) and detected with a photomultiplier tube. Data acquisition was controlled with commercial software (Timecourse; Bio-Rad). Background-corrected fluorescence (F) was normalized to the resting fluorescence (F0) in each cell and F/F0 was calculated. Linescan images (500 lines second−1) were limited to a maximum of 150 seconds because of photodamage.

To minimize observer bias, custom software has been developed for the automated detection and analysis of Ca2+ sparks. This method involves an ‘à trous’ wavelet transform for detecting small-amplitude events in noisy images.20 Events were detected by using the third and fourth wavelet levels, with the threshold set at >3 SD for the noise on each wavelet level. Events detected but not apparent on the image were manually deleted. Ca2+ spark amplitudes were recorded as the maximum increase in normalized fluorescence (ΔF/F0) for a 5-pixel-wide region of interest centered on the point of maximum fluorescence. The software also extracted the full duration at half-maximum fluorescence (FDHM) of each event. Oscillations were analyzed with ImageJ (developed by Wayne Rasband, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD; available at http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/index.html), to determine the amplitude and duration of manually defined events.

Ca2+ Microfluorimetry

Changes in [Ca2+] within myocytes were recorded by using microfluorimetry, as previously described.7 Vessels were incubated in a 5-μM fura-2AM solution with DMSO (1% vol/vol), visualized on an inverted microscope (Diaphot 200; Nikon) and excited alternately at 340 and 380 nm (20 cyc/s). This method loads smooth muscle but not endothelium with the Ca2+ indicator in this preparation.7 Emitted fluorescence was recorded at 510 nm for each excitation wavelength (F340 and F380) with a spectrofluorometer (Ratiomaster RF-F3011; Photon Technology International, South Brunswick, NJ). The fluorescence ratio (R = F340/F380) was used to track changes in [Ca2+]i.21,22 There were large changes in the absolute values of R during this project, although the proportional dynamic range, signal-to-noise ratio, and relative amplitudes of the caffeine responses were unaltered. To allow data to be summarized, changes in R (ΔR) have been normalized using the resting ratio in the same tissue at the beginning of the experiment (R0). No attempt has been made to convert the data to [Ca2+]i, and analysis has been restricted to the changes in responses in internally controlled experiments.

Solutions and Drugs

The bath perfusate had the composition (mM): NaCl, 140; KCl, 5; d-glucose, 5; CaCl2, 2; MgCl2, 1.3; and HEPES, 10, with pH set to 7.4 with NaOH. Solution for vessel isolation contained 0.1 mM CaCl2. Drugs were applied in a prewarmed bath solution to the outside of the arterioles. The drugs were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Poole, UK), with the exception of the V1a antagonist, SR49059 (the kind gift of Claudine Serradeil-Le Gal; Sanofi, France).

Data Analysis

Summarized data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Ca2+ spark and oscillation data for pig arterioles were not normally distributed (P < 0.001; Kolmogorov-Smirnov test), and so a nonparametric Mann–Whitney test was used. Differences between mean [Ca2+]i transients in microfluorimetry experiments were assessed with a paired t-test for single comparisons, or repeated-measures ANOVA with a Tukey-Kramer post hoc test for multiple comparisons. The accepted significance level was P ≤ 0.05.

Results

Spontaneous Ca2+ Sparks and Oscillations under Control Conditions

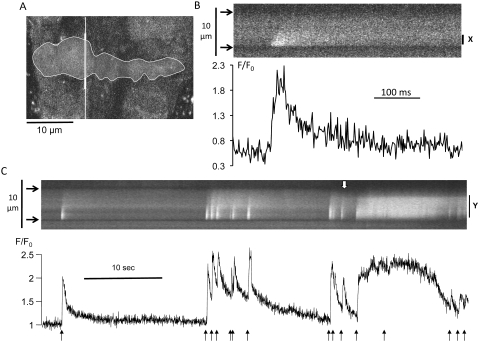

Confocal linescan Ca2+ images from myocytes in porcine retinal arterioles revealed spontaneous Ca2+ sparks and oscillations under control conditions (Fig. 1), similar to those previously reported in the rat.17 The sparks had a rapid rising phase (20–50 ms to peak) followed by an approximately exponential decay, with a total duration of 200 to 300 ms (Fig. 1B). Myocytes also generated more prolonged phasic [Ca2+] elevations lasting many seconds (Fig. 1C). We use the term oscillation for these events, but recognize that they may include longitudinally propagating Ca2+ waves, which cannot be identified in our transverse linescans. Both spark and oscillation characteristics are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

Spontaneous cellular Ca2+ signaling in porcine retinal arterioles under control conditions. (A) A 2-D confocal optical section through three adjacent fluo-4-loaded myocytes in a retinal arteriole. The line shown in white was scanned 500 seconds−1 to generate linescan images (B, C). (B) High time-resolution linescan of a Ca2+ spark in a single smooth muscle cell (outlined in A). Arrowheads: cell boundaries. The time series plots normalized fluorescence (F/F0) for a narrow region centered on the peak of the spark (X). (C) Longer linescan record from the same cell showing sparks and more prolonged oscillations. Fluorescence changes averaged across the whole width of the cell (Y) are plotted. This increased spatial averaging has considerably slowed the apparent kinetics of individual sparks (black arrows). The downward deflection of the upper boundary of the cell (white arrow) is caused by myocyte contraction.

Table 1.

Summary Data for Ca2+ Sparks and Oscillations Recorded from Porcine Retinal Arteriolar Myocytes under Control Conditions and during the First 120 Seconds of AVP Exposure

| Ca2+ Events | Control | AVP | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spark frequency, /10s | 0.27 ± 0.03 (139 cells) | 0.47 ± 0.19 (41 cells) | 0.034 |

| Spark amplitude, ΔF/F0 | 0.47 ± 0.02 (48 events) | 0.48 ± 0.01 (164 events) | NS |

| FDHM, ms | 27 ± 3 (48 events) | 24 ± 1 (164 events) | NS |

| Oscillation frequency, /10s | 0.11 ± 0.04 (53 cells) | 0.32 ± 0.08 (53 cells) | 0.015 |

| Oscillation amplitude, ΔF/F0 | 0.45 ± 0.05 (14 events) | 0.61 ± 0.03 (194 events) | NS |

| Duration, s | 6.51 ± 1.15 (14 events) | 4.94 ± 0.33 (194 events) | NS |

The data were obtained from linescans of arterioles from 4 animals: 10 control vessels and 8 exposed to AVP. Average frequencies were calculated based on all the cells analyzed, including 0 values. P-values were calculated with the Mann–Whitney U-test. NS, P > 0.05.

Table 2.

Summary Data for Ca2+ Sparks and Oscillations Recorded under Control Conditions and from Linescans of up to 130-Second Duration Recorded 10 Minutes after AVP Washout

| Ca2+ Events | Control | 10 min WO after AVP | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spark frequency, /10s | 0.31 ± 0.04 (93 cells) | 0.43 ± 0.05 (66 cells) | 0.014 |

| Spark amplitude, ΔF/F0 | 0.54 ± 0.15 (251 events) | 0.66 ± 0.02 (273 events) | NS |

| FDHM, ms | 20 ± 1 (251 events) | 21 ± 1 (273 events) | NS |

| Oscillation frequency, /10s | 0.12 ± 0.02 (86 cells) | 0.23 ± 0.03 (80 cells) | 0.0008 |

| Oscillation amplitude, ΔF/F0 | 0.66 ± 0.04 (87 events) | 0.75 ± 0.04 (180 events) | NS |

| Duration, s | 7.09 ± 0.71 (87 events) | 8.06 ± 0.54 (180 events) | NS |

P-values were calculated with the Mann–Whitney U-test. NS, P > 0.05.

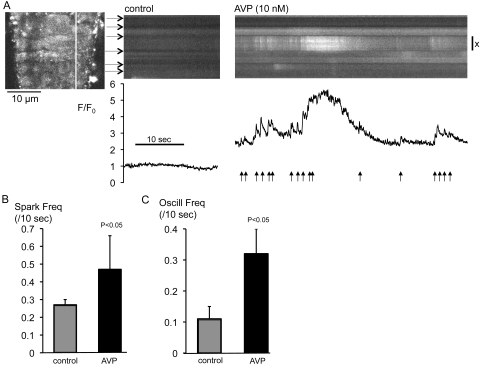

Effect of AVP on Ca2+ Sparks and Oscillations

High-speed Ca2+ imaging revealed the complexity of cellular responses to AVP. AVP (10 nM) increased fluorescence, indicating a rise in baseline cytoplasmic [Ca2+] (Fig. 2A). In 35 cells from four vessels, the baseline value of F/F0 was increased from 1.00 ± 0.03 at the end of the control period to 1.74 ± 0.14 after a 60-second exposure to AVP (P < 0.0001, Wilcoxon signed ranks). Ca2+ sparks and oscillations were also increased. This response was highly variable, even between adjacent cells in the same vessel (Fig. 2A). Data were summarized by measuring the frequency of Ca2+ events in every cell, the quiescent cells being included as 0. When this statistic was used, AVP raised mean spark frequency by 74% and mean oscillation frequency by 190% relative to control values in the same vessels, without affecting event amplitude or duration (Table 1). This description is the first in regard to the effects of AVP on Ca2+ sparks and oscillations in native vascular myocytes.

Figure 2.

AVP increased Ca2+ sparks and oscillations. (A) A 2-D confocal optical section through eight adjacent fluo-4-loaded myocytes in a rat retinal arteriole (left), indicating the relevant scanline. Linescan images are shown for the same cells (horizontal arrows: cell boundaries) under control conditions and during superfusion with AVP (10 nM). Normalized fluorescence (F/F0) is plotted for the myocyte marked X; arrows: Ca2+ sparks. AVP exposure commenced 60 seconds before acquisition of the rightmost linescan. Summary data (mean ± SEM) are for (B) spark and (C) oscillation frequencies under control conditions and during AVP exposure.

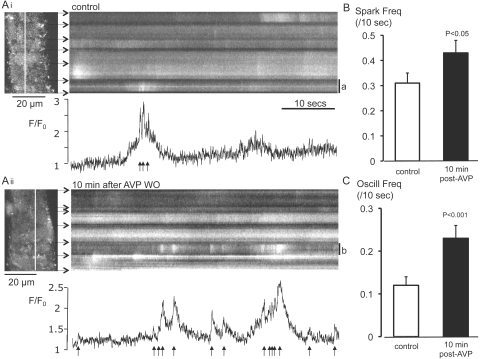

The acute effects of AVP on sparks and oscillations persisted after washout of the hormone (Fig. 3A). Arterioles were superfused with AVP (10 nM for 3 minutes) before a 10-minute washout period. The mean frequencies of sparks and oscillations after washout were increased by 39% and 92%, respectively, relative to control values in the same vessels (Figs. 3B, 3C, Table 2). Again, the amplitude and duration of sparks and oscillations were not affected (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Ca2+ sparks and oscillations were persistently increased after washout of AVP. (A) Confocal linescan records from separate regions of the same arteriole (Ai) under control conditions and (Aii) 10 minutes after washout of AVP (10 nM). XY frames to the left of each panel show six contiguous arteriolar myocytes and the relevant scanline (white). Horizontal arrows: cell boundaries. F/F0 is plotted for a single myocyte in each linescan (a and b); arrows: sparks. (B) Summary data (mean ± SEM) are for spark frequency recorded before (control) and 10 minutes after washout of AVP from different regions in the same vessels. (C) Summary data (mean ± SEM) for oscillation frequency recorded under control conditions and 10 minutes after washout of AVP.

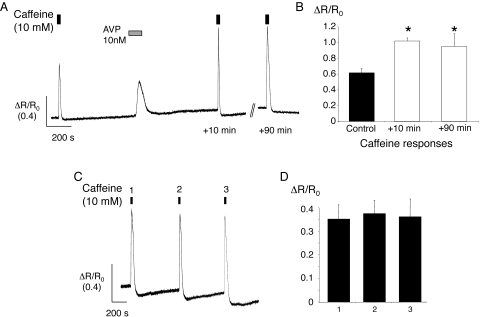

Effect of AVP on SR Ca2+ Loading in Retinal Arterioles

A possible cause of increased Ca2+ sparks and oscillations is increased SR Ca2+ loading.23 This possibility was tested by using caffeine to release intracellular Ca2+ stores by opening ryanodine receptors (RyRs).24 Caffeine (10 mM) produced a rapid Ca2+ transient followed by a variable undershoot under control conditions (Fig. 4). Subsequent superfusion with 10 nM AVP produced a smaller transient with slower kinetics. Cellular and subcellular signaling detail such as sparks and oscillations were not resolved. When caffeine was applied, 10 minutes after washout of AVP, at a time when Ca2+ sparks and oscillations were increased (Fig. 3), the transient was enhanced compared with the control. The response was still larger than control when caffeine was applied for a third time, some 90 minutes after washout of AVP.

Figure 4.

Caffeine-evoked Ca2+ transients were enhanced after AVP treatment. (A) Sample record showing changes in the fura-2 fluorescence ratio, normalized to the resting ratio (ΔR/R0) for an arteriole exposed to caffeine under control conditions, then approximately 10 minutes after washout of AVP, and again approximately 90 minutes after washout. Changes in the fura-2 fluorescence ratio (ΔR) have been normalized to the resting ratio in the same arteriole (R0). (B) Summary data for six arterioles showing the mean responses (±SEM) to each of the caffeine stimuli during the protocol shown in (A). *P < 0.05 versus control. (C) Ca2+ transients recorded from an arteriole during three consecutive applications of caffeine (10 mM). The vessel was superfused with normal bath solution for approximately 10 minutes between caffeine applications. (D) Summary data for eight vessels show the mean response (±SEM) to each of three consecutive applications of caffeine.

In 17 arterioles from 12 animals, the caffeine-evoked transient (ΔR/R0) was increased from a mean control value of 0.59 ± 0.06 to 0.77 ± 0.06 after 10 minutes of washout following exposure to AVP (P < 0.005). The mean response to AVP itself was 0.24 ± 0.03. In a subset of six vessels from five different animals in which caffeine was applied three times, the mean amplitude of the caffeine transient was 0.62 ± 0.06 under control conditions, 1.02 ± 0.04 after 10 minutes' washout (P < 0.05 versus control; ANOVA), and 0.95 ± 0.16 after 90 minutes' washout (P < 0.05 versus control; ANOVA). There were no changes in the response when caffeine alone was applied three times at 10-minute intervals (n = 8 vessels from six animals; Fig. 4). Thus, the increase in caffeine transients after AVP did not result from previous exposure to caffeine or time-dependent effects.

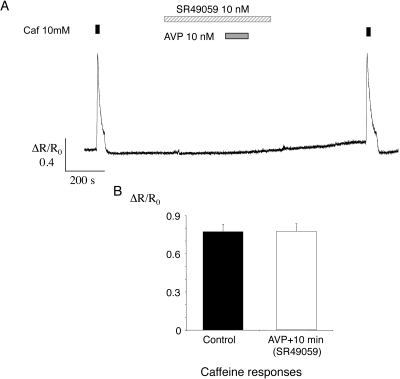

Enhancement of Caffeine Responses by AVP Mediated by V1A receptors

Application of AVP failed to evoke an increase in [Ca2+]i when a V1a receptor blocker (SR 4905925; 10 nM) was included in the bathing medium from 5 minutes before application of AVP until 2 minutes after washout (Fig. 5A). The response to caffeine after AVP washout was similar to that during the control period. In 15 vessels from three animals, the mean caffeine response (ΔR/R0) was 0.77 ± 0.06 before AVP application and 0.78 ± 0.06 after a 10-minute washout (NS, paired t-test; Fig. 5B). This result suggests that both the direct effect of AVP on [Ca2+]i and the persistent enhancement of the caffeine-evoked response were mediated via V1a receptors.

Figure 5.

AVP effects were blocked by SR49059. (A) A sample record of [Ca2+]i for an arteriole that was exposed to caffeine and then to the V1a blocker SR49059. AVP was then applied, and caffeine was reapplied after washout of AVP and SR49059. (B) Summary data for 15 arterioles show the mean responses (±SEM) to the two caffeine stimuli during the protocol shown in (A).

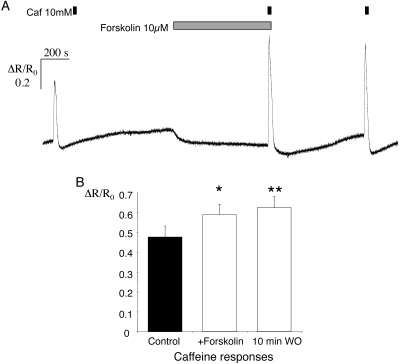

Effect of Forskolin on Caffeine-Evoked Transients in Retinal Arterioles

Experiments were performed to identify the signaling pathway involved in the increase in SR Ca2+ loading. It has been demonstrated that forskolin, which activates adenylyl cyclase and elevates cAMP levels (see reviews in Refs. 26, 27), also increases caffeine responses in isolated vascular myocytes from cerebral arteries in both rats and mice.27 Forskolin (10 μM) mimicked the effect of AVP on caffeine transients in pig retinal arterioles. Caffeine (10 mM) was applied under control conditions and again after a 10-minute superfusion with forskolin (Fig. 6A). Forskolin itself produced a small but consistent decline in the fluorescence ratio, which averaged 0.08 ± 0.02 relative to the control (P < 0.005, paired t-test). This decrease recovered during a 10-minute washout, after which the caffeine response was still enhanced relative to the control. In 12 vessels from six animals, the mean response to caffeine (ΔR/R0) was increased from 0.48 ± 0.06 under control conditions to 0.59 ± 0.05 after superfusion with forskolin for 10 minutes (P < 0.05 versus control, ANOVA, Fig. 6B). After a further 10-minute washout, caffeine transients were still enhanced, with a mean increase of 0.62 ± 0.06 (P < 0.01 versus control, ANOVA).

Figure 6.

Caffeine-evoked Ca2+ transients were enhanced after exposure to forskolin. (A) A sample record of [Ca2+]i for an arteriole which was exposed to caffeine (10 mM) under control conditions, after a 10-minute exposure to forskolin (10 μM), and finally, approximately 10 minutes after washout of forskolin. Changes in the fura-2 fluorescence ratio (ΔR) were normalized to the resting ratio in the same arteriole (R0). (B) Summary data for 12 arterioles showing the mean responses (±SEM) to each of the caffeine stimuli during the protocol shown in (A). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; versus control in both cases.

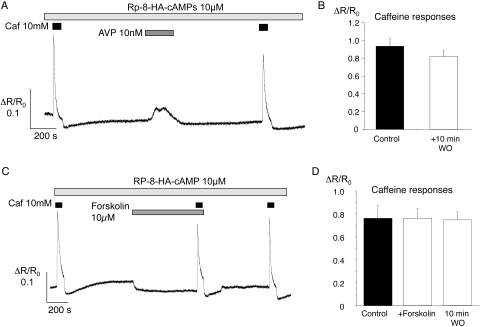

Effect of Rp-8-HA-cAMPS on Enhancement of Caffeine-Evoked Transients by AVP and Forskolin

Cyclic AMP exerts many of its effects through activation of protein kinase A (PKA; see review in Ref. 28). We tested this effect by using the Rp-isomer of the compound 8-hexylaminoadenosine-3′, 5′-monophosphorothioate (Rp-8-HA-cAMPS), a lipophilic PKA inhibitor.29 Tissues were pre-exposed to the drug (10 μM) for a minimum of 2 hours. Brisk, caffeine-evoked responses were still seen but were no longer enhanced after treatment with AVP or forskolin (Fig. 7). In a series of 19 vessels (from eight animals) preincubated with Rp-8-HA-cAMPS, the mean caffeine-induced increase in fluorescence ratio (ΔR/R0) was 0.93 ± 0.09 during the control period and 0.82 ± 0.08 after a 10-minute washout after AVP (NS, paired t-test; Fig. 7B). [Ca2+]i transients were still evoked by AVP itself in these experiments, with a mean increase in normalized ratio of 0.31 ± 0.04 (Fig. 7A). Rp-8-HA-cAMPS also blocked the increase in caffeine responses after exposure to forskolin (Fig. 7C). In 12 vessels from six animals, the mean caffeine response was 0.76 ± 0.12 during the control period, 0.76 ± 0.08 after 10 minutes of forskolin superfusion, and 0.75 ± 0.07 after a further 10-minute washout (Fig. 7D; NS, ANOVA versus control). The forskolin-induced reduction in baseline was not affected in these experiments (Fig. 7C), suggesting that the effect was not PKA dependent.

Figure 7.

Rp-8-HA-cAMPs inhibited enhancement of caffeine-evoked Ca2+ transients. (A) A sample record showing [Ca2+]i changes in an arteriole preincubated with the PKA inhibitor Rp-8-HA-cAMPs (10 μM). Caffeine (10 mM) was applied under control conditions and 10 minutes after exposure to AVP (10 nM). (B) Summary data for 19 arterioles show the mean caffeine responses (±SEM) for the control and post-AVP applications. (C) A sample record shows [Ca2+]i changes in the presence of Rp-8-HA-cAMPs (10 μM). Caffeine (10 mM) was applied under control conditions, after a 10-minute exposure to forskolin (10 μM), and approximately 10 minutes after washout of forskolin. (D) Summary data for 12 arterioles showing the mean responses (±SEM) to each caffeine stimulus.

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated for the first time in any native vascular myocytes that AVP persistently increases the frequency of Ca2+ sparks and oscillations in retinal arterioles, as well as raising baseline [Ca2+]i (Table 1, Fig. 2). The fact that AVP, which constricts retinal arterioles,30 also increases sparks and oscillations, is consistent with our proposal that sparks can act as building blocks for global Ca2+ signals during excitation–contraction coupling in these microvessels.18 In pig retinal vessels, as in many other preparations, AVP responses desensitize relatively rapidly.1,15,16 Persistent upregulation of Ca2+ sparks and oscillations after washout of AVP (Fig. 3) may prolong agonist effects despite receptor desensitization. In rat retinal arteriolar myocytes, sparks and oscillations reflect release of SR Ca2+ via RyR2-gated channels,31 and brief localized sparks can summate to generate more prolonged and global Ca2+ oscillations.18 Spark and oscillation characteristics in porcine vessels (Tables 1, 2) were similar to those previously observed in the rat.17,18 It should be noted that the apparent increase in oscillation duration in this study reflects a change in the measure used (from FDHM to full duration) rather than any biological difference. Ca2+ oscillations were also observed to result from spark summation in pig arterioles (Figs. 1C, 2A, 3A). Oscillations are associated with myocyte contraction in rat retinal vessels17,18 and, although transverse linescans cannot detect cell shortening, the narrowing of the cell profile during the second oscillation in Figure 1C almost certainly resulted from cell movement due to contraction. Taken together, this evidence again suggests that Ca2+ sparks promote constriction in these microvessels, rather than relaxation, as in larger arteries.1,19

Our results support a model in which increased SR Ca2+ content after AVP exposure accounts for the increase in Ca2+ sparks and oscillations. RyR opening, the Ca2+ release event responsible for sparks,18 can be stimulated by increases in cytoplasmic or SR [Ca2+].32,33 Rapid application of a high concentration of caffeine activates RyR release channels maximally and has been widely used as an indirect measure of SR Ca2+ content.27,34,35 The amplitude of caffeine-induced Ca2+ transients was increased both 10 and 90 minutes after AVP removal, suggesting a persistent increase in SR loading (Fig. 4). Given that spontaneous Ca2+ release in the form of sparks is increased under these conditions (Fig. 3), it seems likely that SR Ca2+ uptake must also be increased to account for the increased SR load (Fig. 4). A possible target molecule is phospholamban, which disinhibits uptake by the SR Ca2+ ATPase when phosphorylated by PKA.27,36 Cyclic nucleotide-dependent increases in Ca2+ store loading, with consequent increases in spontaneous Ca2+ release and activation of large-conductance, Ca2+-sensitive K+ channels, are believed to contribute to the action of some vasodilators.27,37 However, we believe this is the first demonstration that the cAMP/PKA pathway can persistently increase Ca2+ store content, spark, and oscillation frequency in response to a vasoconstrictor such as AVP.

The AVP-evoked Ca2+ transient was inhibited by a V1a antagonist (Fig. 5). V1a receptors are normally coupled via a G protein of the Gq/11 type to phospholipase C, stimulating the generation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3).38,39 This, in turn, releases SR Ca2+ via IP3 receptors (IP3Rs).40 Since IP3R-mediated Ca2+ release can stimulate RyR opening in smooth muscle,23,41 these events may underpin the increase in Ca2+ sparks and oscillations during acute application of AVP (Fig. 2). The persistent increase in SR store load was also V1a dependent (Fig. 5). This part of the response appeared to involve cAMP and PKA, as the response was mimicked by forskolin (Fig. 6) and blocked by RpcAMPs (Fig. 7A). RpcAMPS did not inhibit the AVP-induced Ca2+ transient, indicating that different signaling pathways are responsible for AVP-induced Ca2+ release and the persistent increase in store loading. Activation of V1a receptors has been shown to stimulate diverse signaling pathways in vascular cell lines.42,43 AVP treatment can amplify cAMP production when vascular smooth muscle cells are treated with a β-adrenoceptor agonist, although AVP alone does not elevate cAMP.44 This effect is blocked by V1a, but not V2 antagonists, and appears to be dependent on the AVP-induced rise in [Ca2+]i.44,45 Some such signal cross-talk may explain the observations in our experiments. Caffeine itself can act as a phosphodiesterase inhibitor and so increase cAMP levels,46 but we found no evidence of increased store loading after exposure to caffeine alone (Fig. 4). Smooth muscle responses secondary to stimulation of V1a receptors on endothelial cells cannot be completely ruled out.47

It is interesting to speculate on the possible physiological significance of AVP in the regulation of tone in retinal arterioles. How much access circulating AVP would have to retinal myocytes across the endothelial tight junctions of the inner blood–retinal barrier is unclear,48 but vasopressin has also been identified within the retinal ganglion cell layer, adjacent to retinal vessels.12 Local release of vasopressin may contribute to retinal vascular tone. AVP may act as a cellular switch, increasing vascular resistance and reducing retinal blood flow on going from dark to light. Retinal vasopressin levels vary cyclically with a light/dark cycle and are almost 100% higher in the light.11 It is possible, therefore, that increased SR loading and Ca2+ release due to retinal AVP decreases retinal blood flow in daylight, when total retinal metabolism and O2 consumption are reduced.13 This remains to be determined experimentally.

Footnotes

Supported by Wellcome Trust Grant 074648/Z/04 and Juvenile Diabetes Research Fund Grant 2-2003-525 (TMC).

Disclosure: O. Jeffries, Sanofi (F); M.K. McGahon, Sanofi (F); P. Bankhead, Sanofi (F); M.M. Lozano, Sanofi (F); C.N. Scholfield, Sanofi (F); T.M. Curtis, Sanofi (F); J.G. McGeown, Sanofi (F)

References

- 1.Scholfield CN, McGeown JG, Curtis TM. Cellular physiology of retinal and choroidal arteriolar smooth muscle cells. Microcirculation 2007;14:11–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curtis TM, Scholfield C, McGeown DJ. Calcium signaling in ocular arterioles. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr 2007;17:1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laties AM. Central retinal artery innervation: absence of adrenergic innervation to the intraocular branches. Archives of Ophthalmology 1967;77:405–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ye XD, Laties AM, Stone RA. Peptidergic innervation of the retinal vasculature and optic nerve head. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1990;31:1731–1737 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dumskyj MJ, Eriksen JE, Dore CJ, Kohner EM. Autoregulation in the human retinal circulation: assessment using isometric exercise, laser Doppler velocimetry, and computer-assisted image analysis. Microvasc Res 1996;51:378–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hein TW, Xu W, Kuo L. Dilation of retinal arterioles in response to lactate: role of nitric oxide, guanylyl cyclase, and ATP-sensitive potassium channels. Invest Ophthalmol VIs Sci 2006;47:693–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scholfield CN, Curtis TM. Heterogeneity in cytosolic calcium regulation among different microvascular smooth muscle cells of the rat retina. Microvasc Res 2000;59:233–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nielsen S, Frokiar J, Marples D, Kwon T-H, Agre P, Knepper MA. Aquaporins in the kidney: from molecules to medicine. Physiol Rev 2002;82:205–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barrett LK, Singer M, Clapp LH. Vasopressin: mechanisms of action on the vasculature in health and in septic shock. Crit Care Med 2007;35:33–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ludwig M, Leng G. Dendritic peptide release and peptide-dependent behaviours. Nat Rev Neurosci 2006;7:126–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gauquelin G, Gharib C, Ghaemmaghami F, et al. A day/night rhythm of vasopressin and oxytocin in rat retina, pineal and harderian gland. Peptides 1988;9:289–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Djeridane Y. Immunohistochemical evidence for the presence of vasopressin in the rat harderian gland, retina and lacrimal gland. Exp Eye Res 1994;59:117–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Birol G, Wang S, Budzynski E, Wangsa-Wirawan ND, Linsenmeier RA. Oxygen distribution and consumption in the macaque retina. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2007;293:H1696–H1704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riva CE, Grunwald JE, Petrig BL. Reactivity of the human retinal circulation to darkness: a laser Doppler velocimetry study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1983;24:737–740 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caramelo C, Tsai P, Okada K, Briner VA, Schrier RW. Mechanisms of rapid desensitization to arginine vasopressin in vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol 1991;260:F46–F52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schrier RW, Briner V, Caramelo C. Cellular action and interactions of arginine vasopressin in vascular smooth muscle: mechanisms and clinical implications. J Am Soc Nephrol 1993;4:2–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curtis TM, Tumelty J, Dawicki J, Scholfield CN, McGeown JG. Identification and spatiotemporal characterization of spontaneous Ca2+ sparks and global Ca2+ oscillations in retinal arteriolar smooth muscle cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2004;45:4409–4414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tumelty J, Scholfield N, Stewart M, Curtis T, McGeown G. Ca2+ sparks constitute elementary building blocks for global Ca2+ signals in myocytes of retinal arterioles. Cell Calcium 2007;41:451–466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nelson MT, Cheng H, Rubart M, et al. Relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by calcium sparks. Science 1995;270:633–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.von Wegner F, Both M, Fink RH. Automated detection of elementary calcium release events using the à trous wavelet transform. Biophys J 2006;90:2151–2163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem 1985;260:3440–3450 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Curtis TM, Scholfield CN. Nifedipine blocks Ca2+ store refilling through a pathway not involving L-type Ca2+ channels in rabbit arteriolar smooth muscle. J Physiol 2001;532:609–623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McGeown JG. Interactions between inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors and ryanodine receptors in smooth muscle: one store or two? Cell Calcium 2004;35:613–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meissner G, Rios E, Tripathy A, Pasek DA. Regulation of skeletal muscle Ca2+ release channel (ryanodine receptor) by Ca2+ and monovalent cations and anions. J Biol Chem 1997;272:1628–1638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Serradeil-Le Gal C, Herbert JM, Delisee C, et al. Effect of SR-49059, a vasopressin V1a antagonist, on human vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol 1995;268:H404–H410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Insel PA, Ostrom RS. Forskolin as a tool for examining adenylyl cyclase expression, regulation, and G protein signaling. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2003;23:305–314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wellman GC, Santana LF, Bonev AD, Nelson MT. Role of phospholamban in the modulation of arterial Ca(2+) sparks and Ca(2+)-activated K(+) channels by AMP. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2001;281:C1029–C1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scott JD. Cyclic nucleotide-dependent protein kinases. Pharmacol Ther 1991;50:123–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rothermel JD, Parker Botelho LH. A mechanistic and kinetic analysis of the interactions of the diastereoisomers of adenosine 3′,5′-(cyclic)phosphorothioate with purified cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase. Biochem J 1988;251:757–762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scholfield CN, Curtis TM. Heterogeneity in cytosolic calcium regulation among different microvascular smooth muscle cells of the rat retina. Microvasc Res 2000;59:233–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Curtis TM, Tumelty J, Stewart MT, et al. Modification of smooth muscle Ca2+ sparks by tetracaine: evidence for sequential RyR activation. Cell Calcium 2008;43:142–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zahradnikova A, Zahradnik I, Gyorke I, Gyorke S. Rapid activation of the cardiac ryanodine receptor by submillisecond calcium stimuli. J Gen Physiol 1999;114:787–798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gyorke I, Gyorke S. Regulation of the cardiac ryanodine receptor channel by luminal Ca2+ involves luminal Ca2+ sensing sites. Biophys J 1998;75:2801–2810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Santana LF, Kranias EG, Lederer WJ. Calcium sparks and excitation-contraction coupling in phospholamban-deficient mouse ventricular myocytes. The J Physiol 1997;503:21–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.White C, McGeown JG. Carbachol triggers RyR-dependent Ca(2+) release via activation of IP(3) receptors in isolated rat gastric myocytes. J Physiol 2002;542:725–733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simmerman HK, Jones LR. Phospholamban: protein structure, mechanism of action, and role in cardiac function. Physiological Reviews 1998;78:921–947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Porter VA, Bonev AD, Knot HJ, et al. Frequency modulation of Ca2+ sparks is involved in regulation of arterial diameter by cyclic nucleotides. Am J Physiol 1998;274:C1346–C1355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alexander SP, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to receptors and channels, 2nd ed. Br J Pharmacol 2006;147(suppl 3):S1–S168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schoneberg T, Kostenis E, Liu J, Gudermann T, Wess J. Molecular aspects of vasopressin receptor function. Adv Exp Med Biol 1998;449:347–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lo Russo A, Passaquin AC, Ruegg UT. Mechanism of enhanced vasoconstrictor hormone action in vascular smooth muscle cells by cyclosporin A. Br J Pharmacol 1997;121:248–252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.White C, McGeown JG. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors modulate Ca2+ sparks and Ca2+ store content in vas deferens myocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2003;285:C195–C204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu Y, Taylor CW. Stimulation of arachidonic acid release by vasopressin in A7r5 vascular smooth muscle cells mediated by Ca2+ stimulated phospholipase A2. FEBS Lett 2006;580:4114–4120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Byron KL, Lucchesi PA. Signal transduction of physiological concentrations of vasopressin in A7r5 vascular smooth muscle cells: a role for PYK2 and tyrosine phosphorylation of K+ channels in the stimulation of Ca2+ spiking. J Biol Chem 2002;277:7298–7307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Webb JG, Yates PW, Yang Q, Mukhin YV, Lanier SM. Adenylyl cyclase isoforms and signal integration in models of vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2001;281:H1545–H552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang J, Sato M, Duzic E, et al. Adenylyl cyclase isoforms and vasopressin enhancement of agonist-stimulated cAMP in vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol 1997;273:H971–H980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sutherland EW, Rall TW. Fractionation and characterization of a cyclic adenine ribonucleotide formed by tissue particles. J Biol Chem 1958;232:1077–1091 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ostrowski NL, Lolait SJ, Young WS., 3rd Cellular localization of vasopressin V1a receptor messenger ribonucleic acid in adult male rat brain, pineal, and brain vasculature. Endocrinology 1994;135:1511–1528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gardner TW, Antonetti DA, Barber AJ, Lieth E, Tarbell JA. The molecular structure and function of the inner blood-retinal barrier. Penn State Retina Research Group. Doc Ophthalmol 1999;97:229–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]