A point mutation of the rhodopsin gene results in a mutant Rho-C185R protein and causes dominant retinal degeneration in mice.

Abstract

Purpose.

To identify a new mouse mutation developing early-onset dominant retinal degeneration, to determine the causative gene mutation, and to investigate the underlying mechanism.

Methods.

Retinal phenotype was examined by indirect ophthalmoscopy, histology, transmission electron microscopy, immunohistochemistry, Western blot analysis, and electroretinography. Causative gene mutation was determined by genomewide linkage analysis and DNA sequencing. Structural modeling was used to predict the impact of the mutation on protein structure.

Results.

An ENU-mutagenized mouse line (R3), displaying attenuated retinal vessels and pigmented patches, was identified by fundus examination. Homozygous R3/R3 mice lost photoreceptors rapidly, leaving only a single row of photoreceptor nuclei at postnatal day 18. The a- and b-waves of ERG were flat in R3/R3 mice, whereas heterozygous R3/+ mice showed reduced amplitude of a- and b-waves. The R3/+ mice had a slower rate of photoreceptor cell loss than compound heterozygous R3/− mice with a null mutant allele. The R3 mutation was mapped and verified to be a rhodopsin point mutation, a c.553T>C for a p.C185R substitution. The side chain of Arg185 impacted on the extracellular loop of the protein. Mutant rhodopsin-C185R protein accumulated in the photoreceptor inner segments, cellular bodies, or both.

Conclusions.

Rhodopsin C185R mutation leads to severe retinal degeneration in R3 mutant mice. A dosage-dependent accumulation of misfolded mutant proteins likely triggers or stimulates the death of rod photoreceptors. The presence of a wild-type rhodopsin allele can delay the loss of photoreceptor cells in R3/+ mice.

Rhodopsin gene (Rho) mutations are one of the most prevalent causes of retinitis pigmentosa (RP). More than 100 predominantly autosomal dominant RHO mutations have been reported to cause RP in humans (http://www.sph.uth.tmc.edu/RetNet/home.htm). The phenotypic expression, disease progression, and vision impairment are often variable among patients carrying identical or different rhodopsin mutations.

To examine the mechanisms linking mutations in Rho to the death of photoreceptor cells, transgenic mice expressing rhodopsin mutations as found in patients with RP and knockout mice lacking rhodopsin have been generated.1–5 Rhodopsin knockout mice display clear, reproducible differences in the time course of photoreceptor cell degeneration in comparison with transgenic rodent models expressing mutant rhodopsin.

Studies of these animal models provide valuable insight into the roles of rhodopsin in the structure of rod photoreceptor outer segments, in the phototransduction pathway, and in the pathogenesis of mutant rhodopsin proteins causing rod photoreceptor cell death.6–11 Specific stress signaling pathways mediating the unfolded protein response have been reported to be responsible for the pathologic events triggered by misfolded rhodopsin mutant proteins.12 Experimental therapeutic approaches designed to inhibit the activation of stress signals triggered by unfolded protein response or to prevent the production of either mutant proteins or transcripts show some efficacy in animal models for slowing the progression of vision loss.13–17

Given that there are more than 100 identified mutations in human RP, a comprehensive picture of how different rhodopsin mutations induce various photoreceptor cell degeneration pathways is far from complete.18 Therefore, further studies are needed to investigate the mechanisms for why and how patients with identical or different rhodopsin mutations display a wide range of phenotypic variability. New animal models that recapitulate similar rhodopsin mutations found in human patients with RP will be useful for mechanistic studies and for testing or developing new therapeutic approaches.

We have identified a new mouse mutation that displays dominant retinal degeneration (RD) from a screen of N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU)-mutagenized mice. We have further determined that this severe RD phenotype is caused by a point mutation of the rhodopsin gene resulting in a mutated Rho-C185R protein. Our studies suggest that this mouse rhodopsin mutant line is a useful model for understanding how rhodopsin mutant proteins trigger the death of rod photoreceptors.

Methods

Mouse Breeding and Fundus Photography

Animals were cared for in accordance with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and the guidelines of the University of California at Berkeley Committee on Animal Research. The ENU-mutagenized mice in the C57BL/6J strain background were produced as described previously.19,20 An indirect ophthalmoscope and a portable slit lamp were used to examine the eyes of the ENU-mutagenized mice. For fundus examination, mouse pupils were dilated with a mixture of 1% atropine and 1% phenylephrine. Fundus photographs were captured by a small animal camera (Genesis; Kowa Pharmaceuticals, Montgomery, AL) with 200 ASA color slide film (elite2; Kodak, Rochester, NY). Homozygous mutant (R3/R3) mice were generated from the intercross of heterozygous mutant (R3/+) mice. Compound mutant (R3/−) mice were generated by intercrossing between R3/R3 mice and rhodopsin knockout (−/−) mice.5

Genomewide Linkage Analysis and Causative Gene Identification

Genomewide linkage analysis was performed according to previously described methods.20,21 Mutant R3 mice in the C57BL/6J strain background were crossed with wild-type C3H/HeN mice to produce affected G1 hybrid mice. G1 hybrids were further crossed with wild-type C3H/HeN mice to produce second-generation (G2) mice. The G2 mice were examined for retinal phenotype, and genomic DNA samples were extracted from tail snips for genomewide linkage analysis using a total of 59 microsatellite markers.20 Based on the chromosomal location, candidate causative genes were identified from a mouse genome database on the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Web site. DNA sequencing was performed on DNA products generated from the transcripts of candidate causative genes by RT-PCR and/or from the exons of mutant genomic DNA by PCR. The following paired primers were used to sequence the rhodopsin cDNA: 5′-AAGCAGCCTTGGTCTCTGTC-3′ and 5′-TAGTCAATCCCGCATGAACA-3′ with a product length of 630 bp; 5′-AACTTCCGCTTCGGGGAGAA-3′ and 5′- CCGGAACTGCTTGTTCAACA-3′ with a product length of 510 bp; 5′-CAGCTGGTCTTCACAGTCAA-3′ and 5′-TATCAAGCTGTCCCCATTGA-3′ with a product length of 560 bp. A synthesis kit (First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used to synthesize the first-strand cDNA from total RNA isolated from mutant retinas. Then a DNA polymerase kit (Platinum pfx; Invitrogen) was used to amplify the target cDNA and DNA fragments. Primers for sequencing rhodopsin gene from mouse tail DNA were 5′-AGCCATTCATGCTTATGTCC-3′ and 5′-ATGGCGTCTGTACGAACCCT-3′ with a product length of 330 bp.

Biochemical Studies

For membrane protein-enriched experiments, four retinas were dissected, homogenized, and briefly sonicated in 1 mL sample buffer (0.1 M NaCl and 50 mM Na2HPO4, pH 7.2) with proteinase inhibitors (Roche Diagnostic Corporation, Indianapolis, IN). The insoluble fraction was collected after centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4°C. The pellet was washed with fresh sample buffer once. One hundred microliters of NP-40 lysis buffer (1% NP-40, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, and one tablet of proteinase inhibitor per 10 mL solution) was added to the pellet and sonicated. After centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4°C, the supernatant was collected, and the protein concentration was determined (Coomassie Assay Reagent kit; Pierce, Rockford, IL). The samples were then mixed with an equal volume of 1× loading buffer (60 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 10 mM dithiothreitol, 10% glycerol, and 0.0001% bromophenol blue). Equal amounts of the samples were loaded onto 12.5% PAGE for separation and subjected to Western blot analysis. Rhodopsin proteins were detected with a mouse anti-rhodopsin monoclonal antibody (Chemicon, Temecula, CA), and β-actin was detected with mouse monoclonal β-actin antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO).

Histology

Eyeballs were marked by a stitch at the superior side and quickly enucleated. Eyecups, opened from anterior chambers, were immediately immersed in 2% glutaraldehyde and 2.5% formaldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2) at room temperature for 2 hours and then at 4°C for 24 hours. Eyecups were postfixed in 1% aqueous OsO4, dehydrated through graded acetone, and embedded in resin (Epon 12-Araldyte 502; Ted Pella, Redding, CA). Thick (1-μm) sections through the optic nerve head were collected on glass slides and were stained with toluidine blue. Bright-field images were acquired via a microscope (Axiovert 200; Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). Retinal sections cut through the optic nerve head were used for the quantitative analysis of outer nuclear rows. Retinal pictures were taken from an area, in the superior portion of the retina, approximately 650 μm from the optic nerve head using a 20× objective lens for counting the rows of nuclei in outer nuclei layer (ONL). A minimum of two animals of each genotype were examined for each time point. The average number of rows of nuclei in the ONL from retina sections of each genotype was determined. Thin sections (60 nm) were stained with Sato's triple lead solution and examined with an electron microscope (JEM-1200EX II; JEOL, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunohistochemistry

Eyes were fixed in freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 2 hours at 4°C. Fixed samples were rinsed and infiltrated overnight in 30% sucrose in PBS, then embedded in OCT compound (Tissue-Tek, Torrance, CA). Cryosections (8 μm) were collected and stained with a monoclonal antibody against mouse rhodopsin at 1:100 (MAB5316; Chemicon, Temecula, CA) and a polyclonal antibody against human red/green opsin at 1:200 (AB5405; Millipore Corporation, Bedford, MA). Slides were prepared with DAPI mounting medium (VectorShield; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and images were acquired on a microscope (Axiovert 200; Zeiss).

Electroretinography

Whole-field scotopic electroretinography was recorded in postnatal day (P) 21 mutant littermates and wild-type mice. Mice were dark adapted overnight and anesthetized with a mixture of 100 μg ketamine and 16 μg xylazine per gram of body weight mixed in PBS (1.8 μL per gram of body weight) in dim red light. Mouse pupils were dilated with a mixture of 1% atropine HCl (Alcon, Fort Worth, TX) and 2.5% phenylephrine HCl (Wilson, Mustang, OK). Proparacaine 0.5% (Bausch & Lomb, Tampa, FL) was used as a local anesthetic, and a heating pad was used to maintain the body temperature at 37°C. Before recording, mice were returned to complete darkness for 20 minutes. ERG recordings were obtained using contact lens electrodes on the cornea with a layer of clear 2.5% hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (Gonisol; Novartis Ophthalmics, Duluth, GA). The grounding electrode was inserted into the mouse tail, and differential electrodes were inserted in the cheeks. Eyes were stimulated with short intervals of low-intensity light followed by longer intervals of high-intensity light. The light intensity varied from 0 cd · s/m2 to 31.62 cd · s/m2 in seven separate steps ranging from 30-second intervals to 120-second intervals. Each step was repeated twice. Three mice of each genotype were tested, and measurements from the right eye were used to ensure reproducibility of light stimuli. The average of amplitude values of step 7 (31.62 cd · s/m2 light intensity) are presented in Results.

Results

Dominant and Rapid Retinal Degeneration in R3 Mice

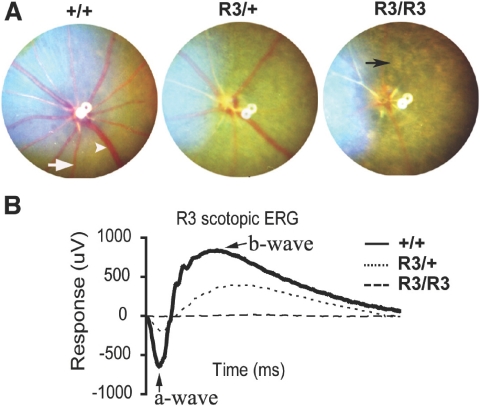

A G1 male founder, displaying abnormalities of retinal degeneration (RD) such as attenuated retinal vessels and unevenly distributed pigment patches, was identified from a fundus screen of ENU-mutagenized mice. Approximately half the offspring generated from an intercross between this male founder and wild-type C57/BL6 females developed the abnormal fundus characteristics of the male founder. The mutation, named R3, caused dominant RD with rapid disease progression. Homozygous mutant (R3/R3) mice were generated from the intercross between heterozygous mutant (R3/+) mice. A characteristic RD appearance was observed in the fundus of both R3/+ and R3/R3 mutant mice (Fig. 1A). The RD phenotype was consistently more severe in R3/R3 than R3/+ mutant mice. Electroretinograms demonstrated a severely reduced photoreceptor cell function in both R3/+ and R3/R3 mutant animals (Fig. 1B). The a- and b-waves were not recordable in R3/R3 mutant mice and were severely attenuated in R3/+ mutant mice. The a-wave amplitude of R3/+ mutant mice was approximately one-third that in wild-type (+/+) mice.

Figure 1.

R3 mutant mice develop dominant retinal degeneration. (A) Fundus photographs of wild-type (+/+), heterozygous mutant (R3/+), and homozygous mutant (R3/R3) mice at the age of 3 weeks. White arrowhead: retinal vein. White arrow: artery. Black arrow: unevenly distributed pigment patch in the homozygous mutant. (B) Scotopic ERG data of +/+ (solid line), R3/+ (dotted line), and R3/R3 (dashed line) mice at the age of 3 weeks. Arrows: a- and b-waves. Average of amplitude values of step 7 (31.62 cd · s/m2 light intensity) are presented.

A Single Nucleotide Substitution Resulted in the Rhodopsin C185R Mutant Protein

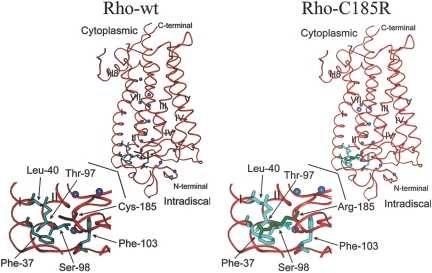

Heterozygous R3/+ mutant mice in the C57BL/6J strain background were crossed with wild-type C3H/HeNTac-MTV mice to generate the first-generation (G1) mutant hybrid mice. G1 mutant mice were crossed with wild-type C3H/HeNTac-MTV animals to produce the second-generation (G2) mice. Thirty-eight G2 mice (half normal, half mutant) were used for a genomewide mapping with 59 satellite markers. The lineage marker D6Mit328, located at 49.3 cM on mouse chromosome 6, displayed an LOD score of 9.2 (Fig. 2A). Therefore, the rhodopsin gene (Rho), located at 51.5 cM on chromosome 6, was a likely candidate causative gene. Sequencing of cDNA generated from a R3/+ mouse retina by RT-PCR revealed a rhodopsin point mutation, a c.553T>C for a p.C185R substitution. Subsequent sequencing of PCR products generated from the genomic DNAs of two homozygous mice confirmed this point mutation (Fig. 2B), linking the R3 retinal phenotypes to the RhoC185R mutation. The C185 residue is located in the extracellular (intradiscal) loop 2 (E-II) between transmembrane domains IV and V. Three-dimensional structure modeling of Rho-C185R mutant protein predicts that the large side chain of the arginine residue disrupts the proper folding and assembly of mutant rhodopsin protein (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

The rhodopsin C185R point mutation is determined in the R3 mouse line. (A) The causative gene mutation of the R3 mouse line is mapped to chromosome 6 with a LOD score of 9.2 for linkage marker D6mit328. (B) DNA sequencing reveals a rhodopsin point mutation, a c.553T>C for a p.C185R substitution.

Figure 3.

Structure models of wild-type (Rho-wt) and mutant (Rho-C185R) forms of rhodopsin. The rhodopsin backbone is shown as a red ribbon, and water molecules are shown as blue spheres. The Arg185 side chain is shown in green and is oriented in the same direction as the native Cys side chain. Considering the van der Waal's radius of Arg185, at least five different side chains are impacted by this mutation: Phe37, Leu40, Ser98, Thr97, and Phe103 (all shown in aqua). The largest clash is clearly with Phe37 in transmembrane domain I, which is very significant and likely disrupts proper folding and assembly of the mutant protein. Models were generated using a graphic molecular modeling program and PDB file 1L9H for the ground-state crystal structure of rhodopsin.

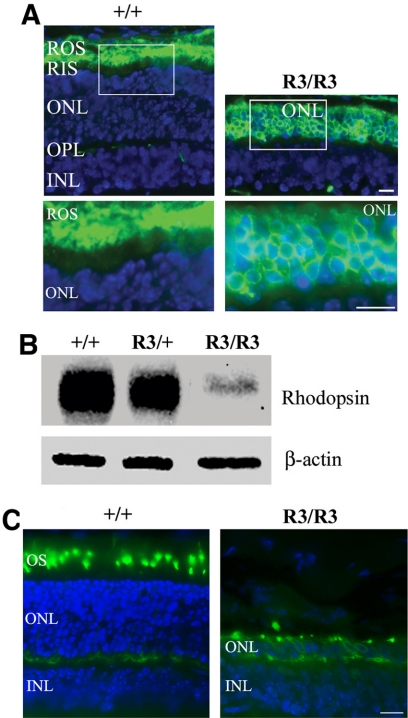

Mislocalization and Decrease of Rhodopsin-C185R Mutant Proteins in Photoreceptor Cell

Immunolocalization studies revealed the accumulation of mutant rhodopsin proteins in photoreceptor inner segments and cell bodies of mutant R3/R3 retinas at P14, in contrast to wild-type retinas in which rhodopsin proteins correctly trafficked to photoreceptor outer segments (Fig. 4A). Mutant proteins appeared only in inner segments and outer nuclei layers in P7 R3/R3 mutant retinas and obviously accumulated in P10 R3/R3 mutant retinas (data not shown). Western blot analysis demonstrated that the level of mutant proteins was dramatically decreased in homozygous mutant retinas (Fig. 4B). The level of rhodopsin proteins was also reduced in heterozygous mutant retinas compared with wild-type retinas. Equal loading of these protein samples was confirmed by the level of β-actin. Cone photoreceptors were examined by immunostaining with a cone-specific red/green opsin antibody. The cone-specific opsins were observed in cell bodies of the remaining single row of photoreceptor cells in the P21 R3/R3 mutant retina (Fig. 4C) compared with normal localization in the cone outer segments in the P21 wild-type retina. Thus, the single row of photoreceptor cells contains only cones in the R3/R3 mutant.

Figure 4.

Expression and distribution of mutant rhodopsin proteins in the retina. (A) Immunostaining of rhodopsin (green) in retinal cryosections prepared from wild-type (+/+) and homozygous mutant (R3/R3) mice at the age of P14. Cell nuclei were labeled by DAPI (blue). The white boxed areas are enlarged in the lower panels. Scale bar, 20 μm. ROS, retinal outer segment; RIS, retinal inner segment; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer. (B) Western blot analysis results of the membrane protein-enriched samples prepared from P14 mouse retinas detected by a monoclonal anti-rhodopsin antibody. Rhodopsin-C185R mutant protein level was extremely low in homozygous mutant retina and was significantly reduced in heterozygous mutant retina in comparison with wild-type retina. (C) Immunostaining of red/green-opsin (green) in retinal sections of P21 wild-type (+/+) and homozygous mutant (R3/R3) mice by a specific red/green-opsin antibody. Cell nuclei were labeled by DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 20 μm. The remaining outer nuclear row of mutant (R3/R3) retina is positively stained as the cone photoreceptor cells.

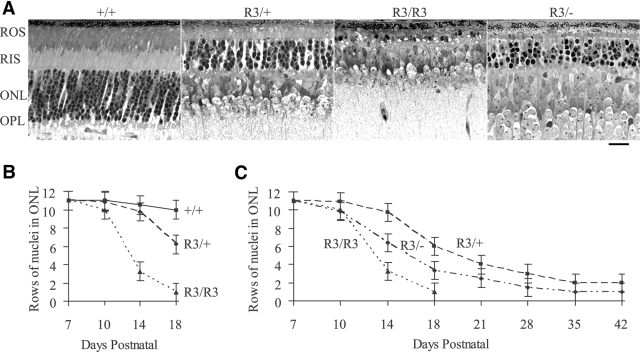

Progressive Loss of Photoreceptors in RhoC185R Mutant Retinas

Histologic data showed a rapid loss of the ONL in the retinas of R3/R3 and R3/+ mutant mice. Representative histologic sections showed that the ONL was reduced to a single row, which were presumably cones, in the R3/R3 mutant retina at P18, whereas ONL thickness in the R3/+ mutant retina was approximately 50% of that in wild-type (Fig. 5A). By counting the rows of ONL nuclei in mutant and wild-type mice, R3/R3 mutant mice showed rapid photoreceptor degeneration (Fig. 5B). Loss of photoreceptors was less rapid in R3/+ mutant retinas than in R3/R3 mutant retinas, with degeneration clearly observed by P14, progressing to two rows of ONL nuclei by P42 (Figs. 5B, C). The R3/− mutant mice with one C185R mutant allele and one null mutant allele had an intermediate rate of ONL loss, with a single ONL row at P35 (Fig. 5C), compared with R3/+ and R3/R3 mutant mice.

Figure 5.

Progressive loss of photoreceptors in mutant mouse lines. (A) Histologic sections were prepared from wild-type (+/+), heterozygous (R3/+), homozygous (R3/R3), and compound heterozygous (R3/−) retinas of mice at P18. Scale bar, 20 μm. (B) The graph reveals the average number of rows of ONL nuclei in +/+ (solid line), R3/+ (dashed line), and R3/R3 (dotted line) retinas of mice between ages P7 and P18. (C) The graph shows the average number of rows of ONL nuclei in R3/− (dotted-dashed line), R3/+ (dashed line), and R3/R3 (dotted line) retinas of mice between ages P7 and P42.

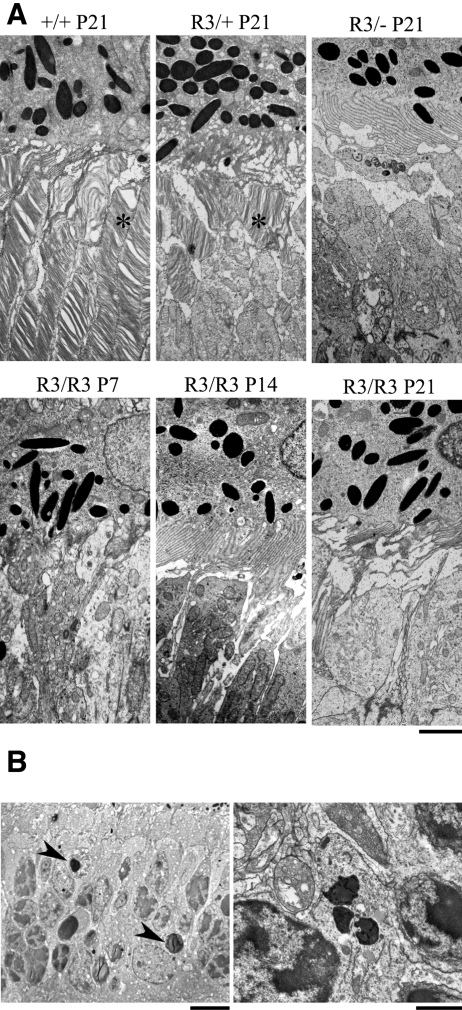

We examined the ultrastructure of mutant and wild-type retinas by transmission electron microscopy (Fig. 6A). The R3/+ mutant retina displayed short outer segments with disorganized discs, whereas no outer segments or discs could be seen in the R3/− mutant retina (Fig. 6A). Outer segments or discs were not observed in the R3/R3 mutant retinas from P7 to P21 mice. In addition, darkly stained or condensed nuclei, characteristic of apoptotic cells, were prevalent in the ONL of the R3/R3 mutant retina (Fig. 6B). Organized outer segments were seen in wild-type littermate controls.

Figure 6.

Transmission electron microscopy images of outer segments and photoreceptor cells. (A) Well-organized outer segments with normal disc stacking (asterisk) adjacent to the RPE in the wild-type (+/+) retina, short and disorganized outer segments (asterisk) in the heterozygous (R3/+) retina, and absence of outer segments with presumably inner segments adjacent to the apical RPE in the homozygous (R3/R3) retina were observed in P21 mice. Scale bar, 2 μm. (B, left) Darkly stained and condensed nuclei (arrowheads), a characteristic of apoptotic cells in the ONL of the R3/R3 retina of mice at age P14. Scale bar, 5 μm. Right: enlarged image of a typical apoptotic nucleus with condensed chromatin in a photoreceptor cell of the same retina. Scale bar, 1 μm.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that a rhodopsin point mutation, a c.553T>C for a p.C185R substitution, causes dominant RD in the R3 mouse line. The gene symbol for R3 mutation is designated as RhoR3. The Rho-C185R mutant protein fails to properly traffic in the rods and accumulates in inner segments of the photoreceptor cells. Downstream effects of abnormally accumulated mutant opsin proteins lead to a rapid loss of photoreceptor cells.

More than 100 human rhodopsin mutations, most of which are point mutations, have been reported to cause dominant RP. However, only a few rhodopsin mutations have been identified in animals thus far, including one naturally occurring rhodopsin mutation, T4R, in English Mastiff dogs22 and two chemically induced mouse rhodopsin mutations, C110Y23 and C185R. These three mutations closely mimic some of the phenotypic characteristics of human RP and are useful for investigating the biochemical mechanisms for RP caused by mutant opsins.24,25 It is unclear why such a small number of naturally occurring rhodopsin mutations have been identified in animals though rhodopsin mutations are prevalent in humans. Perhaps there is a strong evolutionary pressure against the reproduction of animals with vision loss, especially with early-onset blindness, in the natural environment.

Previous studies have demonstrated multiple mechanisms underlying retinal dysfunction caused by rhodopsin mutations, including responses of misfolded or mistrafficked proteins25–29 and the generation of constitutively active forms of rhodopsin through mutation of phosphorylation and arresting-binding shutoff mechanisms.30–32 The C185R mutant shares similarities with the C110Y and T4R mutants that affect the “plug” at the intradiscal (extracellular) side of the rhodopsin protein, which is responsible for protecting the chromophore from bulk water access.33,34 The structure in the extracellular, intradiscal domain of rhodopsin surrounding the Cys110-Cys187 disulfide bond has been shown to be important for the correct folding of this protein.35 The Cys185 residue also contributes to the formation of abnormal Cys185-Cys187 disulfide bonds detected in the mutant Rho-P23H human rhodopsin.

Opsin mutations account for 30% to 40% of identified autosomal dominant RP (adRP), and the P23H mutation is the most prevalent, causing approximately 10% of adRP in US Caucasians and showing a variable progression of RP in humans and in transgenic mice. The P23H mutation results in a misfolded apoprotein opsin, defined by a deficiency in its ability to bind 11-cis retinal to form rhodopsin. Further studies suggest how abnormal Cys185-Cys187 disulfide bonds affect protein function. A detailed biochemical study of the C185A mutant protein, which loses its ability to form this abnormal disulfide bond, has revealed that the mutant protein is less thermally stable and has a slow rate for binding 11-cis retinal. These results indicate that the C185A mutation alone destabilizes the open-pocket conformation of opsin.25 Structural modeling of the C185R mutant protein suggests a disruption of proper folding of the intradiscal domain. The accumulation of mutant proteins in inner segment reflects the mistrafficking of denatured proteins. Therefore, the C185R mutation likely destabilizes the open-pocket conformation and results in a misfolded rhodopsin protein.

Comparative studies of the rate of loss of photoreceptor cells in heterozygous (R3/+), homozygous (R3/R3), and compound mutant retinas (R3/−) with one null (knockout) allele provide valuable insight about the variable RD phenotypes in both humans and animal models. Genetic background and expression dosage variations in rhodopsin transgenic mice lead to a complex situation for the comparison of the rate of loss of photoreceptor cells between various animal models. The C185R mutation leads to rapid degeneration of rods resulting in a flat ERG, whereas only a single row of cones remains in R3/R3 mutant mice by P21. The R3/− mutant mice with one null allele, however, displayed less severe degeneration than homozygous mutant mice. Heterozygous R3/+ mutant mice with one wild-type allele developed the retinal degeneration phenotype more slowly (Fig. 3). Clearly, the presence of a wild-type rhodopsin allele delays but does not prevent photoreceptor loss because the R3/+ mutant mice had only a single outer nuclear layer, presumably the cone photoreceptors, by P42. The absence of outer segments, as observed in ultrastructure studies of R3/R3 homozygous mutant retinas at all ages examined, suggests that mutant rhodopsin proteins are improperly trafficked and sorted in inner segments and fail to form outer segments.

In conclusion, these results indicate that a dosage-dependent accumulation of C185R mutant proteins in photoreceptor cell inner segments likely triggers or promotes the death of photoreceptors. The ENU-mutagenized R3 mutant mouse line may have advantages over existing transgenic and knockout mouse models of retinal degeneration. Given that the mutation occurs in an endogenous rhodopsin gene, studies in this mutant mouse line avoid problems of transgene copy number and position effects in other genetically engineered animal models. Thus, the R3 mouse line is a useful model for dissecting the downstream stress signaling pathways activated by dosage-dependent accumulation of mutant proteins in rod photoreceptors.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Catherine Cheng, Nina Tsai, and Eric Lu for their assistance in some of the immunostaining experiments.

Footnotes

Supported by National Eye Institute Grants EY013849 (XG) and EY016493 (KDR), an East Bay Community Foundation grant (XG), and a Foundation Fighting Blindness grant (JGF).

Disclosure: H. Liu, None; M. Wang, None; C.-H. Xia, None; X. Du, None; J.G. Flannery, None; K. Ridge, None; B. Beutler, None; X. Gong, None

References

- 1.Olsson JE, Gordon JW, Pawlyk BS, et al. Transgenic mice with a rhodopsin mutation (Pro23His): a mouse model of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Neuron 1992; 9: 815–830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang PC, Gaitan AE, Hao Y, Petters RM, Wong F. Cellular interactions implicated in the mechanism of photoreceptor degeneration in transgenic mice expressing a mutant rhodopsin gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1993; 90: 8484–8488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naash MI, Hollyfield JG, al-Ubaidi MR, Baehr W. Simulation of human autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa in transgenic mice expressing a mutated murine opsin gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1993; 90: 5499–5503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Humphries MM, Rancourt D, Farrar GJ, et al. Retinopathy induced in mice by targeted disruption of the rhodopsin gene. Nat Genet 1997; 15: 216–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lem J, Krasnoperova NV, Calvert PD, et al. Morphological, physiological, and biochemical changes in rhodopsin knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999; 96: 736–741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Portera-Cailliau C, Sung CH, Nathans J, Adler R. Apoptotic photoreceptor cell death in mouse models of retinitis pigmentosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994; 91: 974–978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sung CH, Makino C, Baylor D, Nathans J. A rhodopsin gene mutation responsible for autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa results in a protein that is defective in localization to the photoreceptor outer segment. J Neurosci 1994; 14: 5818–5833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li T, Franson WK, Gordon JW, Berson EL, Dryja TP. Constitutive activation of phototransduction by K296E opsin is not a cause of photoreceptor degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1995; 92: 3551–3555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li T, Snyder WK, Olsson JE, Dryja TP. Transgenic mice carrying the dominant rhodopsin mutation P347S: evidence for defective vectorial transport of rhodopsin to the outer segments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996; 93: 14176–14181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang M, Lam TT, Tso MO, Naash MI. Expression of a mutant opsin gene increases the susceptibility of the retina to light damage. Vis Neurosci 1997; 14: 55–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dizhoor AM, Woodruff ML, Olshevskaya EV, et al. Night blindness and the mechanism of constitutive signaling of mutant G90D rhodopsin. J Neurosci 2008; 28: 11662–11672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin JH, Li H, Yasumura D, et al. IRE1 signaling affects cell fate during the unfolded protein response. Science 2007; 318: 944–949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Millington-Ward S, O'Neill B, Tuohy G, et al. Stratagems in vitro for gene therapies directed to dominant mutations. Hum Mol Genet 1997; 6: 1415–1426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cayouette M, Behn D, Sendtner M, Lachapelle P, Gravel C. Intraocular gene transfer of ciliary neurotrophic factor prevents death and increases responsiveness of rod photoreceptors in the retinal degeneration slow mouse. J Neurosci 1998; 18: 9282–9293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ali RR, Sarra GM, Stephens C, et al. Restoration of photoreceptor ultrastructure and function in retinal degeneration slow mice by gene therapy. Nat Genet 2000; 25: 306–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Reilly M, Palfi A, Chadderton N, et al. RNA interference-mediated suppression and replacement of human rhodopsin in vivo. Am J Hum Genet 2007; 81: 127–135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LaVail MM, Yasumura D, Matthes MT, et al. Ribozyme rescue of photoreceptor cells in P23H transgenic rats: long-term survival and late-stage therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000; 97: 11488–11493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guerin K, Gregory-Evans CY, Hodges MD, et al. Systemic aminoglycoside treatment in rodent models of retinitis pigmentosa. Exp Eye Res 2008; 87: 197–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoebe K, Du X, Georgel P, et al. Identification of Lps2 as a key transducer of MyD88-independent TIR signalling. Nature 2003; 424: 743–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Du X, Tabeta K, Hoebe K, et al. Velvet, a dominant Egfr mutation that causes wavy hair and defective eyelid development in mice. Genetics 2004; 166: 331–340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xia CH, Liu H, Cheung D, et al. A model for familial exudative vitreoretinopathy caused by LPR5 mutations. Hum Mol Genet 2008; 17: 1605–1612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kijas JW, Miller BJ, Pearce-Kelling SE, Aguirre GD, Acland GM. Canine models of ocular disease: outcross breedings define a dominant disorder present in the English mastiff and bull mastiff dog breeds. J Hered 2003; 94: 27–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pinto LH, Vitaterna MH, Shimomura K, et al. Generation, characterization, and molecular cloning of the Noerg-1 mutation of rhodopsin in the mouse. Vis Neurosci 2005; 22: 619–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Milla E, Heon E, Grounauer PA, et al. Rhodopsin C110Y mutation causes a type 2 autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmic Genet 1998; 19: 131–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hwa J, Reeves PJ, Klein-Seetharaman J, Davidson F, Khorana HG. Structure and function in rhodopsin: further elucidation of the role of the intradiscal cysteines, Cys-110, -185, and -187, in rhodopsin folding and function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999; 96: 1932–1935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garriga P, Liu X, Khorana HG. Structure and function in rhodopsin: correct folding and misfolding in point mutants at and in proximity to the site of the retinitis pigmentosa mutation Leu-125→Arg in the transmembrane helix C. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996; 93: 4560–4564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu X, Garriga P, Khorana HG. Structure and function in rhodopsin: correct folding and misfolding in two point mutants in the intradiscal domain of rhodopsin identified in retinitis pigmentosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996; 93: 4554–4559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hwa J, Garriga P, Liu X, Khorana HG. Structure and function in rhodopsin: packing of the helices in the transmembrane domain and folding to a tertiary structure in the intradiscal domain are coupled. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997; 94: 10571–10576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee ES, Flannery JG. Transport of truncated rhodopsin and its effects on rod function and degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2007; 48: 2868–2876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dryja TP, Berson EL, Rao VR, Oprian DD. Heterozygous missense mutation in the rhodopsin gene as a cause of congenital stationary night blindness. Nat Genet 1993; 4: 280–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rao VR, Cohen GB, Oprian DD. Rhodopsin mutation G90D and a molecular mechanism for congenital night blindness. Nature 1994; 367: 639–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gross AK, Rao VR, Oprian DD. Characterization of rhodopsin congenital night blindness mutant T94I. Biochemistry 2003; 42: 2009–2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ridge KD, Palczewski K. Visual rhodopsin sees the light: structure and mechanism of G protein signaling. J Biol Chem 2007; 282: 9297–9301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ridge KD, Abdulaev NG, Sousa M, Palczewski K. Phototransduction: crystal clear. Trends Biochem Sci 2003; 28: 479–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karnik SS, Khorana HG. Assembly of functional rhodopsin requires a disulfide bond between cysteine residues 110 and 187. J Biol Chem 1990; 265: 17520–17524 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]