This article reports the study of a novel truncating PROM1 mutation that causes autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa associated with a distinct macular phenotype and myopia, due to specific degradation of the mutated transcript allele by nonsense-mediated decay. The results support evidence that early truncation of PROM1 hampers disc morphogenesis in both rods and cones.

Abstract

Purpose.

To identify the genetic basis of a large consanguineous Spanish pedigree affected with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa (arRP) with premature macular atrophy and myopia.

Methods.

After a high-throughput cosegregation gene chip was used to exclude all known RP and Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA) candidates, genome-wide screening and linkage analysis were performed. Direct mutational screening identified the pathogenic mutation, and primers were designed to obtain the RT-PCR products for isoform characterization.

Results.

Mutational analysis detected a novel homozygous PROM1 mutation, c.869delG in exon 8 cosegregating with the disease. This variant causes a frameshift that introduces a premature stop codon, producing truncation of approximately two-thirds of the protein. Analysis of PROM1 expression in the lymphocytes of patients, carriers, and control subjects revealed an aberrant transcript that is degraded by the nonsense-mediated decay pathway, suggesting that the disease is caused by the absence of the PROM1 protein. Three (s2, s11 and s12) of the seven alternatively spliced isoforms reported in humans, accounted for 98% of the transcripts in the retina. Given that these three contained exon 8, no PROM1 isoform is expected in the affected retinas.

Conclusions.

A remarkable clinical finding in the affected family is early macular atrophy with concentric spared areas. The authors propose that the hallmark of PROM1 truncating mutations is early and severe progressive degeneration of both rods and cones and highlight this gene as a candidate of choice to prioritize in the molecular genetic study of patients with noncanonical clinical peripheral and macular affectation.

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP [MIM268000]) is a genetically and clinically heterogeneous group of ocular diseases that cause rod and cone degeneration. It is characterized by night blindness, constriction of the visual field, and pigment spicule deposits in the mid periphery of the retina, which eventually lead to blindness. To date, it has been postulated that mutations in at least 60 genes may cause RP (see RetNet). RP is a major genetic cause of blindness in adults, with a worldwide prevalence of 1:3000 to 1:4000.1,2 Allelic heterogeneity stands out as a prominent feature of several RP genes, as exemplified by ABCA4,3–5 CRB1,2,6 NRL,7 RDS,8 KLHL7,9 and CEP290,10 where different mutations lead to distinct retinal disease phenotypes. In addition to RP, these genes are responsible for Stargardt disease, cone–rod dystrophy (CORD), macular degeneration, Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA), and pattern macular dystrophy, among other disorders. The wide range of clinical entities associated with these genetic variants support that the proteins encoded by many of these genes are essential for both cone and rod function, and yet each mutation produces a specific phenotypic effect.

Prominin 1 (PROM1, accession number: AF027208, Gene ID: 8842, also known as PROML1, AC133, and CD133; GenBank; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Genbank/ NCBI) is located at 4p15.32 and at maximum length comprises 27 exons. The encoded protein, PROM1, is a five-transmembrane glycoprotein located at the plasma membrane protrusions, with two short N (extracellular)- and C (cytoplasmic)-terminal tails, and two large N-glycosylated extracellular loops (between TM2 and -3, and TM4 and -5). Seven PROM1 protein isoforms produced by alternative splicing have been reported in human tissues,11 although the alternatively spliced exons in the coding region only affect the short N- and the C-terminal domains. PROM1 is expressed in both rod and cone photoreceptors. Moreover, PROM1 expression has been detected in the cells of several other human tissues—among them CD34+ progenitor populations from adult blood and bone marrow cells—which has conferred on this protein the status of a valuable marker for human allogeneic transplantation.12,13 A paralogue of PROM1, PROM2, shares 60% of amino acid identity and displays the same characteristic of membrane topology.14 The pattern of PROM2 expression largely overlaps that of PROM1, except that there is no expression in the retina.

PROM1 function in the retina is not known, although it is selectively associated with microvilli, making a relevant contribution to the generation of plasma membrane protrusions, their organization, and lipid composition, notably with respect to cholesterol.15 In rods, prominin appears to be concentrated in the plasma membrane evaginations at the nascent disc membranes at the base of the outer segments, which are essential structures in the biogenesis of photoreceptor discs and to which the contribution of PROM1 seems crucial.16 The gene and probably also its function are highly evolutionarily conserved. In the Drosophila melanogaster eye, prom (known as eyes closed or eyc) interacts with spacemaker (also known as spam, eyes shut, or eys) and chaoptin to regulate the assembly of microvilli, ensure the structural integrity of the rhabdomeres, and guarantee the proper construction of an open rhabdom system.17 The human homologue of spacemaker, EYS, has been characterized as responsible for autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa.18,19 In mice, the absence of Prom 1 provokes progressive degeneration and functional deterioration of photoreceptors, due to impaired morphogenesis of the discs at the outer segment.16,20 In humans, mutations in PROM1 have been associated with severe forms of retinal dystrophy. Missense mutations are associated with autosomal dominant Stargardt-like or bull's-eye macular dystrophy,16 whereas nonsense and frameshift mutations have been related to retinitis pigmentosa,21,22 and severe cone–rod dystrophy with macular degeneration and night blindness.23

Herein, we describe a novel recessive mutation in the PROM1 gene that is responsible for severe RP with macular degeneration and myopia in a consanguineous pedigree from Spain. The retinal degeneration in these patients seems to be associated with the loss of PROM1 function as the nonsense-mediated decay machinery leads to an almost complete depletion of the mutated transcripts.

Material and Methods

DNA from Patients and Families

A consanguineous Spanish family affected with autosomal recessive RP (Fig. 1) was used in the present study. Informed consent from all the family members was obtained according to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Bioethics Committee of the University of Barcelona (Barcelona, Spain) approved all the work concerning patient recruitment and sample collection. DNA was obtained from blood samples (Wizard Genomic DNA purification kit; Promega; Madison, WI). DNA from 203 matched Spanish control individuals was obtained from whole blood by the same method.

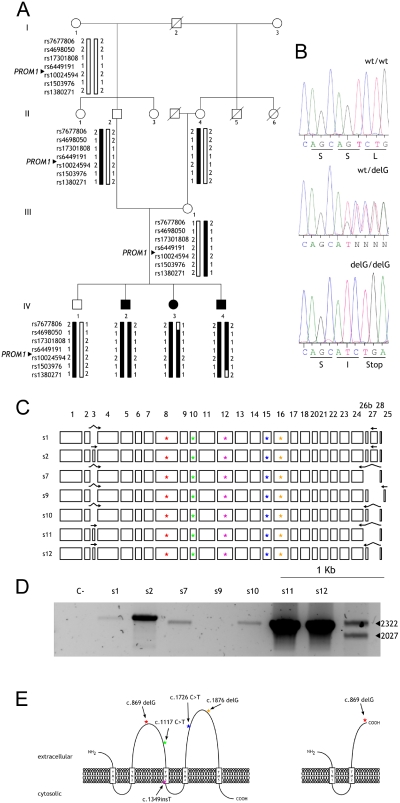

Figure 1.

(A) Pedigree and SNP haplotypes on chromosome 4p16.1-p15.31 surrounding the PROM1 locus. Black bars indicate the disease haplotype while open bars represent nondisease haplotypes. (B) Chromatograms identifying the mutation c.869delG, showing the wild-type exon 8 sequence (top), the heterozygous carrier (middle), and the homozygous patient (bottom). (C) PROM1 exon structure showing the reported seven human isoforms (Fargeas et al.11). They differ on the inclusion/exclusion of exons 3, 25, 26b, and 27, corresponding either to the N (3)- or C (25, 26b, and 27)-terminal tails. Arrows: specific primers for every isoform are indicated over the exons. The reported mutations are shown as colored stars. (D) RT-PCR analysis of PROM1 isoforms in wild-type human retina; s11 and s12 are the most prominent isoforms; isoform s2 is expressed more faintly, whereas isoforms s1, s7, and s10 are barely detectable. (E) PROM1 topology. Left: wild-type PROM1 is predicted to consist of an extracellular N-terminal domain, five transmembrane domains (TM1–TM5) that define two small intracellular and two large extracellular loops and a C-terminal cytoplasmic tail. The location of the novel c.869delG mutation and the previously described c.1117 C>T, c.1349insT, c.1726 C>T, and c.1876delG mutations are also shown. Right: the assumed PROM1 topologic representation of the truncated protein encoded by the mutant allele.

Clinical Examination

RP was diagnosed in all affected members after ophthalmic examination at the Instituto de Microcirugía Ocular (IMO, Barcelona, Spain) and the Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias (Oviedo, Spain). The clinical diagnosis included best corrected visual acuity and slit lamp biomicroscopy, followed by pupillary dilation and indirect ophthalmoscopy, fundus photography, fluorescein angiography, and full-field ERGs from both eyes (Fig. 2). The size and the extent of the visual-field defects within the central 30° were assessed with static perimetry (Fig. 3; Humphrey Field Analyzer; Carl Zeiss Meditec, Oberkochen, Germany). Electroretinograms (ERGs, EOGs) were recorded in accordance with the protocol of the International Society for Clinical Electrophysiology of Vision (ISCEV) at the IMO. A summary of the clinical features is provided in Table 1.

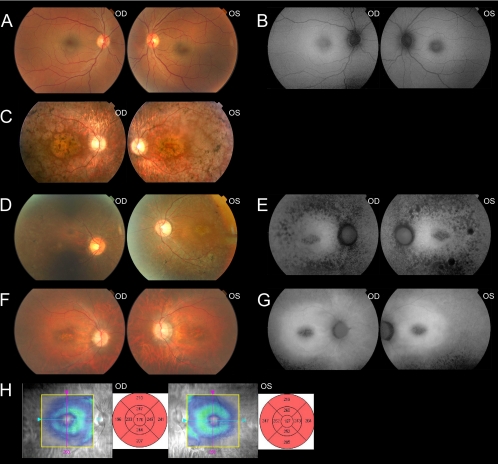

Figure 2.

Fundus eye photographs, autofluorescence images, and optical coherence tomography (OCT) from affected and unaffected family members. Images correspond to nonaffected heterozygous carrier IV1 (A, B), patient IV2 (C), patient IV3 (D, E), and patient IV4 (F–H). The OCT macular scans from patient IV4 show bilaterally neurosensorial atrophy in the macular area.

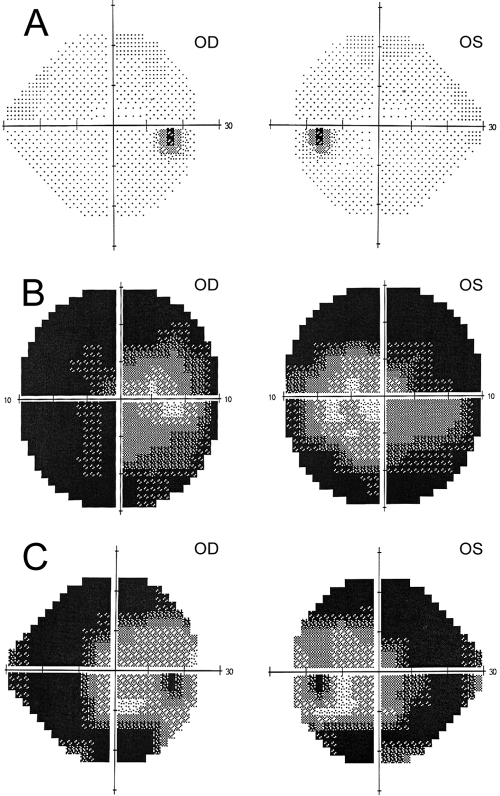

Figure 3.

Humphrey's visual field test from affected and unaffected family members, carrier IV1 (A), patient IV3 (B), and patient IV4 (C). Note the correspondence of the preserved central area around the macula in this test with the autofluorescence images of the posterior pole in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of the Three Affected (IV.2; IV.3, IV.4) and One Nonaffected (IV. 1) Siblings of the Analyzed Consanguineous Pedigree

| Individual | Age* (y) | RP Symptoms | Nystagmus | Progression | Visual Acuity (OD; OS) | Refraction (OD; OS) | Visual Field | Fundus | Myopla Axial Length (mm) (OD; OS) | ERG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IV1 | 37 | No | NA | — | 20/20; 20/20 | Normal | Normal | Normal | —; — | Normal |

| IV2 | 35 | Yes | No | Severe | LP: 20/60 | −0.50; −0.75 × 60° −1.00;−2.25 × 115° | Extensive constriction on both eyes | Bone-spicule pigmentation in the mid-peripheral retina; vessel attenuation; diffuse RPE atrophy; severe macular alteration | 23.62; 24.22 | Notperformed |

| IV3 | 27 | Yes | Yes | Severe | 20/800; 20/400 | −6.25; −0.50 × 130° −5.50; −0.75 × 65° | Extensive constriction on both eyes | Bone-spicule pigmentation in the mid-peripheral retina; subtle vessel attenuation; diffuse RPE alteration; severe macular atrophy | 23.84; 23.39 | Nonrecordable |

| IV4 | 18 | Yes | No | Severe | 20/100; 20/60 | −10.00; −1.00 × 25° −8.75; −1.50 × 175° | Extensive constriction on both eyes | RPE depigmentation in the mid-peripheral retina without bone spicules; RPE alteration in the macula area | 25.96; 25.75 | Nonrecordable |

ERG, electroretinogram; NA, not applicable; LP, light perception; RPE, retinal pigmented epithelium.

Current age

Genotyping and Cosegregation SNP Analysis with the RP-LCA Chip

DNA samples from eight related individuals, three affected and five unaffected, were genotyped with a high-throughput RP-LCA chip, which analyzes 240 SNPs of 40 genes responsible for autosomal dominant and recessive RP and LCA, as previously described.24,25 The SNPs were genotyped (SNPlex platform; Applied Biosystems, Inc. [ABI], Foster City, CA), according to the instructions, protocol, and software provided by the manufacturer. The platform generated raw data genotypes that were then assigned to each individual. Haplotype and cosegregation analyses were performed by hand.

Whole-Genome Scan

The Nsp gene microarray (GeneChip Mapping 500K; Affymetrix; Santa Clara, CA) was used to genotype 262,000 SNPs for each individual according to the manufacturer's protocol. Genotype calls were determined by the Bayesian robust linear model with Mahalanobis distance algorithm (BRLMM).

Linkage Analysis

The BRLMM files were formatted with ALOHOMORA,26 considering the allelic frequencies of the Caucasian population and using the Marshfield map as a reference. Pedstats27 was used to discard Mendelian errors and all markers with a degree of heterozygosity in the family above 90% or below 10%. GRR software28 was used to match the family relationships established in the pedigree and linkage was analyzed with Merlin.29 Each chromosome was considered separately, and inheritance was analyzed under parametric conditions for a rare recessive allele (0.0001) assuming 100% penetrance.

PROM1 Mutation Screening

Twenty-six pairs of primers (Table 2) allowed the PCR amplification of the PROM1 exons plus adjacent intronic sequences in the studied family members. All the fragments were sequenced (BigDye v. 3.1 kit; Prism 3730 DNA sequencer; ABI).

Table 2.

Sequence of Gene-Specific Primers Used for PROM1 gDNA and RNA Amplification

| Primer | Sequence | Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| PROM1-5′NCF | CGTCCAGGGCTCGGGTTTC | PROM1-15R | AAGAAAGACAACTGGTCGGGCA |

| PROM1-5′NCR | AAAAGTTTGGGTTGGACGGGC | PROM1-16F | TGGAGGCTTAGAAGCCATGGGA |

| PROM1-1F | TCCCGAACCCATAAAGGGTCTG | PROM1-16R | TGTGAATGTACTCAATGCCACC |

| PROM1-1R | GCTTCTGTGCAAAGCAATCGCTAA | PROM1-17F | TGCAAATGTTGCCACCTGTTT |

| PROM1-2F | AAGCTGTATGCGGTTTGCTGGT | PROM1-17R | GCAATGGCTGTGGACGGAAA |

| PROM1-2R | GGTTCAAATGGGATTTGTAAGGTGG | PROM1-18F | GAAGGAGGGTGTCTTGGCAC |

| PROM1-3F | TGCTGCCGTTGGTTCTGGAG | PROM1-18R | GGCCTGCTCACAGCAATGGA |

| PROM1-3R | TCCAGTGCTTTGTTGATTGTGTTGA | PROM1-19F | AGTACACATTGTTAATTGTGTTGG |

| PROM1-4F | CTCAATTCTCTGCTTCCTCTGTTTCAA | PROM1-19R | GGCACTGAGGTTTGGGATTGTG |

| PROM1-4R | GGAGTCTGCTGTGCTGGGAGG | PROM1-20F | GCTCATCTCCTTCCCTGCCC |

| PROM1-5F | CAGTCCTTCTGCGGGCTCCT | PROM1-20R | TGGTCCTGCACATCAATGTCCTT |

| PROM1-5R | AAACACCAATTCTGAAATTCGGC | PROM1-21F | TTCCTGCTGTGGAGCCCAGTT |

| PROM1-6F | TCTGGGCAGGAAGCAGCCTA | PROM1-21R | TGAGAAATCTGCACACCCGTGA |

| PROM1-6R | GGTCCTGCTGCCTGTGAAACA | PROM1-22F | GGTTGGAGTGGCCTAGATTCGC |

| PROM1-7F | TGGTGCGGAGACCCTGAAGA | PROM1-22R | TTCACCTGAACAGAAGTGACCCAA |

| PROM1-7R | TGCGTATGGCTGTGTTCCGA | PROM1-23F | CTTTCAACATGGGTCTTTCCTG |

| PROM1-8F | CCCTTGCAGTGTGTCCCTCTCA | PROM1-23R | TCGACTGAACATTTAAACTCATGGCA |

| PROM1-8R | CCTTTGCTCCTGCTGTGGTCA | PROM1-24F | GGTCCCTGCGGAACTTCCAT |

| PROM1-9F | TGCTTGTCAAGGAGGGTCTGAGC | PROM1-24R | ATGTGGAACCTGCAGGTACAG |

| PROM1-9R | TGGGAACTGGAAGGATGAACACA | PROM1-3′ NCF | TGCAACAAACATATTGCTGTGCCT |

| PROM1-10F | ACACAATCCCAGCAGCACCC | PROM1-3′ NCR | TCCAAGTGGAACATGGCCAATC |

| PROM1-10R | TAACTGTCCGAATGACACAATTG | PROM1-exon5-F | GGCATCTTCTATGGTTTTGTGG |

| PROM1-11F | TCGATGGTCTTGGCTATATTCATGC | PROM1-exon6-R | TTCAGATCTGTGAACGCCTTGT |

| PROM1-11R | TGTGCTGCCTGGTCTAAGCGA | GAPDH-F | TGAAGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTGG |

| PROM1-12F | TCCGCTGGTTGAATTGGAAGG | GAPDH-R | AGGCCATGAGGTCCACCAC |

| PROM1-12R | TCTCTCCTCCTCGCGACCTG | PROM1-exon3-F | CCAGAAACTGTAATCTTAGGTCT |

| PROM1-13F | ACCCTTGCCTGTCCTGGAGC | PROM1-NOexon3-F | GATTATGACAAGATTGTCTACTATG |

| PROM1-13R | GCAATCCACATTGAGCGGCA | PROM1-exon27-R | TGTCATAACAGGATTGTGAATACC |

| PROM1-14F | AACAGAGCAAGACTCTGTCTCA | PROM1-exon25-R | CACTGAACAGAAGTGACCCAAC |

| PROM1-14R | TTCCAAGGTCTCAAAGGCTTTC | PROM1-NOexon27-R | GTTGTGATGGGTTTTTCATGGG |

| PROM1-15F | CAGAAGTGGTGGGTGCTGGG | PROM1-Noexons26b_27-R | GTTGTGATGGGTCATCGTACAC |

RT-PCR Analysis of Prom1 and Characterization of Retinal Isoforms

A comprehensive data-mining search in the expression databases NCBI, UCSC, and Ensembl, was performed to identify the transcript and protein isoforms (see Appendix for database Web addresses).

Blood total RNA was obtained (RiboPure-Blood; Ambion, Austin, TX) from individuals IV1, IV3, IV4, and an unrelated control subject. To avoid RNA degradation, samples were mixed with RNA stabilizer (RNALater; Ambion) in a 1:3.5 ratio after blood collection. Total RNA (1.5 μg) was retrotranscribed (Transcriptor High Fidelity cDNA Synthesis Kit; Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) with random hexamers and oligo(dT)18, according to the manufacturer's instructions.

The Prom1 and GAPDH cDNAs were PCR amplified with specific primers (Table 2) in a final volume of 25 μL (GoTaq Flexi; Promega). Primers to detect all PROM1 transcripts (Table 2, PROM1-exon5-F and PROM1-exon6-R) were used for amplification of blood cDNA, in a three-step PCR: denaturation for 3 minutes at 96°C, followed by 35 cycles of 30 seconds at 94°C, 30 seconds at 56°C, and 20 seconds at 72°C. PROM1 retina isoforms differ on the presence or absence of exons 3, 25, 26b, and 27, and specific primers for the amplification of each isoform were therefore designed (Table 2). For amplification of retina cDNA (Biocat, Heidelberg, Germany), the following PCR conditions were used: denaturation at 96°C for 3 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 30 seconds at 94°C, 30 seconds at 56°C, and 150 seconds at 72°C. PCR amplification of GAPDH (GAPDH-F and GAPDH-R) was performed as follows: denaturation for 2 minutes at 96°C, followed by 30 cycles of 20 seconds at 94°C and 2 minutes at 60°C.

The RT-PCR products were resolved by electrophoresis and a semiquantitative evaluation was obtained (Multi Gauge ver. 3.0 software; Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan). Values were normalized against GAPDH levels and represented as a ratio of PROM1/GAPDH. The control wild-type ratio PROM1/GAPDH was arbitrarily set at 100%.

Results

A Spanish pedigree of a consanguineous family with three severely visually impaired members was referred for clinical assessment (Fig. 1). In particular, they reported night blindness in early childhood and bilateral progressive decline in visual acuity. An unaffected carrier sibling was also clinically assessed and had normal findings in an ophthalmic examination (Table 1; Figs. 2A, 2B). After the ophthalmic survey, the three patients were diagnosed with a retinal dystrophy form in which not just rods, but also cones, were severely affected. Patient IV3 had noncongenital nystagmus. Slit-lamp biomicroscopic assessment of the anterior segment was normal in all affected siblings. However, in the three cases, funduscopic examination revealed waxy-pale discs, discrete attenuation of retinal arterioles, and in patients IV2 and IV3, pigmentary bone spicules were apparent in the midperipheral retina, as well. Alteration in the retinal pigment epithelium in the macular area was remarkable in the three affected cases (Table 1; Figs. 2C, 2D, 2F). Moreover, autofluorescence images disclosed marked decreased autofluorescence in the periphery and macular areas due to severe changes in the pigment epithelium, with sparing of the RPE in discrete areas of the posterior pole in patients IV3 and IV4. (Figs. 2E, 2G). The three affected siblings presented with myopia; two of them, IV3 and IV4, showed myopic refractive error exceeding −5 D (Table 1). Patient IV3 had severe nystagmus; therefore, complete optical coherence tomography (OCT) scans of the maculae could not be obtained. Macular OCT scan of patient IV4 showed discrete bilaterally reduced retinal thickness (Fig. 2H). Electroretinograms were undetectable bilaterally for two of the affected siblings (IV3 and IV4). In addition, their visual field tests showed extensive constriction in both eyes (Fig. 3).

Overall, with both the macular and retinal periphery pathologically altered and both types of ERG abolished, the clinical association of symptoms with concentric periphery alterations and ophthalmoscopy findings and the results of visual function tests supported that the patients had diffused retinal dystrophy, with traits assignable to severe RP with a distinct added feature of premature macular affectation (Table 1).

Genome-wide Screening

A comprehensive cosegregation SNP chip containing 40 RP-LCA known genes25 was used to genotype all members of this consanguineous family (Fig. 1A). This chip allows the genotyping of 240 SNPs (6 per gene) located close to each presumptive candidate. On the stringent criteria of both cosegregation and homozygosity, all these candidates were discarded as the cause of the disease. Then, a genome-wide search was considered. Eight related individuals, three affected and five unaffected (Fig. 1A), were analyzed by whole-genome genotyping. The linkage analysis revealed a 11.3-Mb homozygous region on chromosome 4, between SNPs rs7677806 (4p16.1) and rs1380271 (4p15.31), both excluded with a maximum LOD score of 2.532. One of the genes reported within the homozygous interval was PROM1 (4p15.32), previously associated with severe retinal degenerations.16,21–23 After all the exons and flanking intronic regions of PROM1 were sequenced in one affected individual, a homozygous deletion in exon 8 (c.869delG, Fig. 1B) was observed. This mutation cosegregated with the disease in the family, as it was present in homozygosity in all the affected siblings and in heterozygosity in four of the five unaffected members. Moreover, this variant was not detected in 406 chromosomes from unrelated Spanish control subjects. This nucleotide deletion resulted in a frameshift from codon 289 onward and caused a premature STOP codon after the addition of 1 amino acid (Fig. 1B). The predicted protein, if translated, would probably not be functional, as more than half of the protein is missing, including the two extracellular loops (Fig. 1E).

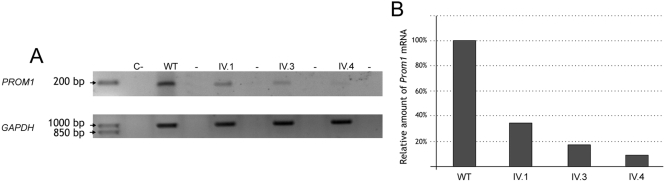

Reduced PROM1 RNA Expression Caused by the c.869delG Mutation

The mutation c.869delG introduces a stop codon on exon 8, 1661 bp upstream of the wild-type termination codon. Transcripts containing premature termination codons are reportedly degraded by nonsense-mediated decay (NMD).30,31 To assess whether the c.869delG mutation results in reduced levels of PROM1 transcripts, we performed a comparative semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis of PROM1 expression in white blood cells from two affected siblings (IV3 and IV4): one carrier (IV1) and a nonrelated control subject (Fig. 4A). The PROM1 mRNA fragment used to test the NMD amplified 179 bp of exons 5 and 6, was proximal to the mutation, and was shared by all the human PROM1 isoforms. The transcript levels observed in the affected siblings were much lower than those in the wild-type control, whereas the carrier sibling yielded a midrange PROM1 transcript level. The relative quantification of the normalized PROM1 transcript showed that the PROM1 level of the carrier was 33% that of the control, whereas the values decreased to 9% to 18% in patients (Fig. 4B), thereby supporting that the NMD machinery specifically degrades the transcript produced by the mutated allele.

Figure 4.

RT-PCR analysis of PROM1 mRNAs from blood of patients IV3 and IV4, the heterozygous carrier and a control individual. (A) Patients IV3 and IV4 showed lower, although detectable levels of PROM1 transcripts compared with carrier IV1 or the control (WT). GAPDH was used as control for normalization. (B) Semiquantitative analysis of PROM1 levels, with GAPDH expression used for normalization and the PROM1 levels of the wild-type control set at 100%.

PROM1 Isoforms in the Retina

PROM1 is a widely expressed gene with an as yet obscure function. After a comprehensive in silico search, at least nine different transcripts of PROM1 in humans due to alternative splicing and the use of five alternative promoters were identified. However, only seven protein isoforms, ranging from 826 to 866 amino acids, seem to be produced.11 The discrepancy between the number of transcripts and protein isoforms arises from variations at the 5′ and 3′ untranslated region (UTR). Given that PROM1 splicing events have not been studied in retinal tissues, we designed specific primers to amplify each reported protein isoform in the human retina (Fig. 2C). The most prominent PROM1 isoforms in the retina are the s11 and s12 (around 47% and 43% respectively). In contrast, the s2 isoform, which spans all the coding exons, was represented at a much lower level (8% of the isoforms), whereas the s1, s7, and s10 isoforms were barely detectable. No traces of s9 isoform expression were detected under our conditions.

Discussion

In this report, a consanguineous Spanish family with three affected siblings is described. The mode of inheritance and the main clinical features correspond to autosomal recessive RP but with a striking premature affectation of cones. The fundus examination revealed attenuation of blood vessels, waxy pale discs, and bone spicules in the mid periphery. The autofluorescence images showed concentric affectation of the retina, with the typical lesions at the periphery and the macula but with a considerable preservation of the RPE around the macula. Therefore, although both rods and cones were affected, the overall features—particularly, the aforementioned preservation area around the macula—led to the designation of the phenotype as RP rather than CORD. In addition, the three patients had myopia, two of them with enlarged axial lengths.

Genome-wide linkage analysis of the pedigree revealed a homozygous-by-descent chromosomal region on 4p15, where the PROM1 gene, already implicated in retinal degeneration diseases, lies. Sequence analysis identified a novel single nucleotide deletion, c.869delG on exon 8, which fully segregates with the disease. This deletion generates a frameshift, which is predicted to result in a prematurely truncated product, missing more than two thirds of the protein and, in principle, assignable to a recessive trait. Although only a limited number of mutations have been described in PROM1 (five, including this work) a genotype–phenotype pattern is beginning to emerge. Missense mutations have been associated with a dominant pattern of inheritance and a clinically mild degeneration of the macula, classified as Stargardt's-like and bull's-eye macular degeneration.16 In contrast, frameshift and null mutations have been associated with recessive retinal dystrophies—mainly RP21,22 and one recent report of CORD.23 In these reports, the authors emphasize that, with gradually evolving degeneration, both rods and cones become affected. These previous results, together with our report, strongly suggest that the pathogenicity of PROM1 mutations includes both types of photoreceptors, but the tempo and order of their affectation is likely to be dependent on the type and location of the mutation. The severity and progression of the disease may also depend on other as yet unknown modifier genes.

Of note, this is the second report of PROM1 mutations associated with high myopia. The fact that this gene is not highly expressed in the sclera23 and that this feature is not constantly observed in patients but is present in two consanguineous families, points to an independent mutation in a closely linked locus, and/or some common modifier variants shared by the affected siblings.

The identified mutation in the present work, c.869delG, is the most upstream mutation described to date. The resulting frameshift would generate a very short protein, with only two transmembrane domains and devoid of the two large extracellular loops, which have been described to be glycosylated and are crucial for the interaction with other protein partners.15 The quantification of PROM1 transcript in the blood of our family showed that the carrier sibling presented around 50% of PROM1 mRNA levels (but no affectation of the retina), and the patients produced around 10% of the normal transcript levels. Therefore, at least for the c.869delG mutation, protein synthesis is compromised by the specific degradation of the mutant mRNA by the NMD pathway and thus, very low amounts of the aberrant protein, if any, reach the cell surface. It has been argued that the pathogenicity of the truncated PROM1 mutant forms is due to a mislocalized protein or an aberrant role during protein trafficking in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi.16 However, our results support that the cause of the disease is the absence of the wild-type PROM1 protein, rather than the gain of function or ER stress caused by the truncated mutant forms. Given that most mutations in PROM1 reported to date generate prematurely truncated proteins, it is conceivable that also in these cases, the NMD machinery degrades the mutated allele transcript, thus providing a rationale for the severe retinal disorder associated with null and frameshift PROM1 mutations. However, we cannot rule out that on mutations that produce a longer protein fragment, the intracellular toxicity of the spared protein could add to the retinal pathogenesis.

Our analysis of PROM1 expression in the retina revealed that the three main isoforms (overall, accounting for >97% of PROM1 transcripts) all contain exon 3, and the main differences lie in the C-terminal encoding exons, with exon 27 being the least represented. The difference between the two more highly expressed isoforms, is the inclusion/exclusion of exon 26b (included in the s12 isoform). That both isoforms are the most prominent in retina and expressed at similar levels suggests a distinct and relevant function for these two isoforms based on the peptide encoded by this distinctive exon. Notably, the identified mutation (c.869delG) will affect all isoforms in the retina, as it is embedded in an exon not affected by alternative splicing. The eventual phenotype of the truncated PROM1 mutant forms would affect the correct folding and sealing of the photoreceptor membrane discs, resulting in an abnormal morphogenesis.

Prominin 1 has been the object of study from very different fields, which explains the multiplicity of names it has received. Originally, it was identified as an antigenic marker (AC133) in human hematopoietic stem cells and some tumoral cells, and was considered to be an antigen associated with undifferentiated replicating cells. The murine Prom (later prom1) was cloned instead as a protein selectively concentrated at the plasma protrusions of neuroepithelial progenitor cells and kidney. The identification of visual disorders associated with PROM1 mutations has shifted its original role from a mere proliferation antigen to a prominent function in the microdomain structure of the plasma membrane, particularly relevant in photoreceptor disc morphogenesis and phototransduction. Although PROM1 is widely expressed, only the retina is affected in patients and prom1-knockout mice. Given that PROM2 shares 60% amino acid identities with PROM1 and the two are concurrently expressed except in the retina, the former may account for the phenotype preservation in the remaining tissues.14 The phenotypic rescue due to partially overlapping of paralogue genes, as shown for REP2 and REP1 in choroideremia,32 is not an uncommon genetic event, but unfortunately no conclusive evidence has been gathered for PROM2.

The extremely high heterogeneity of retinal disorders has hampered molecular diagnosis and genotype–phenotype correlations. In this context, identifying distinct features associated with the clinical status of the patients is invaluable. In light of our results and those of others, we propose that early and severe progressive degeneration of both rods and cones (with peripheral and macular affectation) are the hallmark of PROM1 truncating mutations. In patients in whom these symptoms concur, particularly if high myopia is present, PROM1 would be the candidate of choice to prioritize in molecular genetic study.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the family for participating in the study; Matthew J. Brooks, Harsha K. Rajasimha, and Radu Cojocaru for technical and computational support; Andrés Mayor for sample collection and helpful discussions, and Borja Corcóstegui for constant support of our research.

Appendix

Web Resources

The URLs for data presented in this work are as follows:

Entrez: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/ National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), Bethesda, MD.

GenBank; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Genbank/ NCBI.

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Omim/ NCBI.

RetNet, http://www.sph.uth.tmc.edu/RetNet/; University of Texas Houston Health Science Center, Houston, TX.

UCSC Genome Browser, http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgGateway, University of California Santa Cruz.

Footnotes

Supported by grant BFU2006-04562 (Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia), CIBERER (U718), Fundaluce ONCE (RG-D), and an intramural program of the National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health (AS). JP is under contract to CIBERER. EP is under contract to CIBERER.

Disclosure: J. Permanyer, None; R. Navarro, None; J. Friedman, None; E. Pomares, None; J. Castro-Navarro, None; G. Marfany, None; A. Swaroop, None; R. Gonzàlez-Duarte, None

References

- 1.Hartong DT, Berson EL, Dryja TP. Retinitis pigmentosa. Lancet 2006;368:1795–1809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daiger SP, Bowne SJ, Sullivan LS. Perspective on genes and mutations causing retinitis pigmentosa. Arch Ophthalmol 2007;125:151–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinez-Mir A, Paloma E, Allikmets R, et al. Retinitis pigmentosa caused by a homozygous mutation in the Stargardt disease gene ABCR. Nat Genet 1998;18:11–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stenirri S, Battistella S, Soriani N, et al. Molecular scanning of the ABCA4 gene in Spanish patients with retinitis pigmentosa and Stargardt disease: identification of novel mutations. Eur J Ophthalmol 2007;17:749–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Molday RS, Zhong M, Quazi F. The role of the photoreceptor ABC transporter ABCA4 in lipid transport and Stargardt macular degeneration. Biochim Biophys Acta 2009;1791:573–583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richard M, Roepman R, Aartsen WM, et al. Towards understanding CRUMBS function in retinal dystrophies. Hum Mol Genet 2006;15:R235–R243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanda A, Friedman JS, Nishiguchi KM, Swaroop A. Retinopathy mutations in the bZIP protein NRL alter phosphorylation and transcriptional activity. Hum Mutat 2007;28:589–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Renner AB, Fiebig BS, Weber BH, et al. Phenotypic variability and long-term follow-up of patients with known and novel PRPH2/RDS gene mutations. Am J Ophthalmol 2009;1473:518–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedman JS, Ray JW, Waseem N, et al. Mutations in a BTB-Kelch protein, KLHL7, cause autosomal-dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Hum Genet 2009;84:792–800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.den Hollander AI, Koenekoop RK, Yzer S, et al. Mutations in the CEP290 (NPHP6) gene are a frequent cause of Leber congenital amaurosis. Am J Hum Genet 2006;79:556–561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fargeas CA, Huttner WB, Corbeil D. Nomenclature of prominin-1 (CD133) splice variants: an update. Tissue Antigens 2007;69:602–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shmelkov SV, St Clair R, Lyden D, Rafii S. AC133/CD133/Prominin-1. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2005;37:715–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mizrak D, Brittan M, Alison MR. CD133: molecule of the moment. J Pathol 2008;214:3–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fargeas CA, Florek M, Huttner WB, Corbeil D. Characterization of prominin-2, a new member of the prominin family of pentaspan membrane glycoproteins. J Biol Chem 2003;278:8586–8596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corbeil D, Roper K, Fargeas CA, Joester A, Huttner WB. Prominin: a story of cholesterol, plasma membrane protrusions and human pathology. Traffic 2001;2:82–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang Z, Chen Y, Lillo C, et al. Mutant prominin 1 found in patients with macular degeneration disrupts photoreceptor disk morphogenesis in mice. J Clin Invest 2008;118:2908–2916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zelhof AC, Hardy RW, Becker A, Zuker CS. Transforming the architecture of compound eyes. Nature 2006;443:696–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abd El-Aziz MM, Barragan I, O'Driscoll CA, et al. EYS, encoding an ortholog of Drosophila spacemaker, is mutated in autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Nat Genet 2008;40:1285–1287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collin RW, Littink KW, Klevering BJ, et al. Identification of a 2 Mb human ortholog of Drosophila eyes shut/spacemaker that is mutated in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Hum Genet 2008;83:594–603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zacchigna S, Oh H, Wilsch-Brauninger M, et al. Loss of the cholesterol-binding protein prominin-1/CD133 causes disk dysmorphogenesis and photoreceptor degeneration. J Neurosci 2009;29:2297–2308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maw MA, Corbeil D, Koch J, et al. A frameshift mutation in prominin (mouse)-like 1 causes human retinal degeneration. Hum Mol Genet 2000;9:27–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Q, Zulfiqar F, Xiao X, et al. Severe retinitis pigmentosa mapped to 4p15 and associated with a novel mutation in the PROM1 gene. Hum Genet 2007;122:293–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pras E, Abu A, Rotenstreich Y, et al. Cone-rod dystrophy and a frameshift mutation in the PROM1 gene. Mol Vis 2009;15:1709–1716 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pomares E, Marfany G, Brion MJ, Carracedo A, Gonzalez-Duarte R. Novel high-throughput SNP genotyping cosegregation analysis for genetic diagnosis of autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa and Leber congenital amaurosis. Hum Mutat 2007;28:511–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pomares E, Riera M, Permanyer J, et al. Comprehensive SNP-chip for retinitis pigmentosa-Leber congenital amaurosis diagnosis: new mutations and detection of mutational founder effects. Eur J Hum Genet 2010;18(1):118–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruschendorf F, Nurnberg P. ALOHOMORA: a tool for linkage analysis using 10K SNP array data. Bioinformatics 2005;21:2123–2125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wigginton JE, Abecasis GR. PEDSTATS: descriptive statistics, graphics and quality assessment for gene mapping data. Bioinformatics 2005;21:3445–3447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abecasis GR, Cherny SS, Cookson WO, Cardon LR. GRR: graphical representation of relationship errors. Bioinformatics 2001;17:742–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abecasis GR, Cherny SS, Cookson WO, Cardon LR. Merlin: rapid analysis of dense genetic maps using sparse gene flow trees. Nat Genet 2002;30:97–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rivolta C, McGee TL, Rio Frio T, Jensen RV, Berson EL, Dryja TP. Variation in retinitis pigmentosa-11 (PRPF31 or RP11) gene expression between symptomatic and asymptomatic patients with dominant RP11 mutations. Hum Mutat 2006;27:644–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rio Frio T, Wade NM, Ransijn A, Berson EL, Beckmann JS, Rivolta C. Premature termination codons in PRPF31 cause retinitis pigmentosa via haploinsufficiency due to nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. J Clin Invest 2008;118:1519–1531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cremers FP, Armstrong SA, Seabra MC, Brown MS, Goldstein JL. REP-2, a Rab escort protein encoded by the choroideremia-like gene. J Biol Chem 1994;269:2111–2117 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hubbard TJP, Aken BL, Beal K, et al. Ensembl 2007. Nucleic Acids Res 2007;35:D610–D617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]