Abstract

Although recent studies highlight the importance of histone modifications and ATP-dependent chromatin remodelling in DNA double-strand break (DSB) repair, how these mechanisms cooperate has remained largely unexplored. Here, we show that the SWI/SNF chromatin remodelling complex, earlier known to facilitate the phosphorylation of histone H2AX at Ser-139 (S139ph) after DNA damage, binds to γ-H2AX (the phosphorylated form of H2AX)-containing nucleosomes in S139ph-dependent manner. Unexpectedly, BRG1, the catalytic subunit of SWI/SNF, binds to γ-H2AX nucleosomes by interacting with acetylated H3, not with S139ph itself, through its bromodomain. Blocking the BRG1 interaction with γ-H2AX nucleosomes either by deletion or overexpression of the BRG1 bromodomain leads to defect of S139ph and DSB repair. H3 acetylation is required for the binding of BRG1 to γ-H2AX nucleosomes. S139ph stimulates the H3 acetylation on γ-H2AX nucleosomes, and the histone acetyltransferase Gcn5 is responsible for this novel crosstalk. The H3 acetylation on γ-H2AX nucleosomes is induced by DNA damage. These results collectively suggest that SWI/SNF, γ-H2AX and H3 acetylation cooperatively act in a feedback activation loop to facilitate DSB repair.

Keywords: DNA double-strand break repair, Gcn5, H2AX phosphorylation, histone acetylation, SWI/SNF chromatin remodelling complex

Introduction

DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) can be generated by environmental agents such as ionizing radiation (IR). Unless repaired accurately and efficiently, DSBs can lead to genome instability, cell death and cancer development. On DSB generation, a number of DSB response proteins are recruited to the site of a DSB, and stable accumulation of such proteins within the DNA lesion, manifested as microscopically visible nuclear foci, is important for efficient DSB repair and checkpoint activation (van Gent et al, 2001; Jackson, 2002; Harper and Elledge, 2007). The compaction of the eukaryotic genome into a highly ordered chromatin structure necessitates cellular mechanisms for allowing regulatory proteins to access their target DNA. Indeed, studies show that histone modifications and ATP-dependent chromatin remodelling are both important for DSB repair and damage response (Allard et al, 2004; Peterson and Cote, 2004; Bao and Shen, 2007; Downs et al, 2007; van Attikum and Gasser, 2009).

Among the various histone modifications is S139ph, the most central for the cellular responses to DSBs. γ-H2AX, formed by ATM immediately after DNA damage, has an important function for the formation of stable repair foci in part by providing binding sites for DSB response proteins and has been shown to be important for efficient DSB repair and suppression of genome instability and cancer (Bonner et al, 2008; Kinner et al, 2008). Other types of histone modifications such as acetylation and methylation have also been shown to have important function in DSB response either individually or in conjunction with S139ph (Bird et al, 2002; Downs et al, 2004, 2007; Huyen et al, 2004; Sanders et al, 2004). In addition, a series of recent works have shown that S139ph facilitates the ubiquitination of histones H2A and H2B, which serves to recruit DSB response proteins to the sites of DSB, establishing crosstalk between histone modifications as an important mechanism for DSB response (Huen et al, 2007; Kolas et al, 2007; Mailand et al, 2007; Wang et al, 2007; Doil et al, 2009; Stewart et al, 2009).

Several ATP-dependent chromatin remodelling complexes have been directly implicated in DSB response. In yeast, INO80, SWR1, SWI/SNF and RSC complexes have been shown to be recruited to a DSB and reconfigure the nucleosomes around the DSB in such a way to facilitate DNA repair and/or to modulate checkpoint activation (Downs et al, 2004; Morrison et al, 2004; van Attikum et al, 2004, 2007; Chai et al, 2005; Shim et al, 2005; Bao and Shen, 2007). Mammalian SWI/SNF complexes have also been shown to target the chromatin at DBS sites and facilitate DNA repair (Park et al, 2006). Although INO80 and Swr1 complexes have been suggested to be recruited to a DSB through interaction with γ-H2AX, the mechanisms for these interactions have remained unclear (Downs et al, 2004; Morrison et al, 2004; van Attikum et al, 2004). Similarly, BRG1 and hBrm, the mutually exclusive ATPase subunits of human SWI/SNF complexes, have been shown to interact with γ-H2AX nucleosomes; however, the nature of their interactions has remained elusive (Park et al, 2006).

Interestingly, the yeast INO80 and mammalian SWI/SNF complexes interact with γ-H2AX and yet seem to stimulate γ-H2AX formation (Papamichos-Chronakis et al, 2006; Park et al, 2006), suggesting the existence of interdependence between chromatin remodelling and S139ph. However, how these distinct mechanisms of chromatin modifications work together during DBS repair has remained obscure. In this study, we investigated the specific interaction between SWI/SNF and γ-H2AX nucleosomes, and found an unexpected way of interaction between a chromatin remodeller and γ-H2AX nucleosomes; SWI/SNF binds to γ-H2AX nucleosomes by interacting with acetylated H3 rather than γ-H2AX itself. Through the course of further dissecting the responsible mechanisms for this interaction, we have revealed that SWI/SNF, γ-H2AX and H3 acetylation cooperatively act in a feedback activation loop to facilitate DBS repair. We propose a model for this novel mechanism and discuss its biological significance.

Results

SWI/SNF binds to γ-H2AX nucleosomes in S139ph-dependent manner

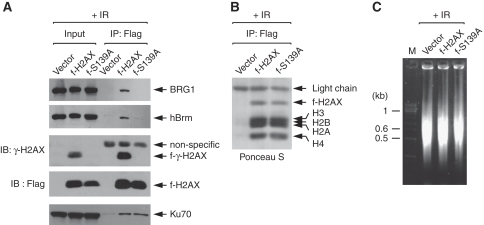

We have earlier shown the interaction of SWI/SNF with γ-H2AX nucleosomes by immunoprecipitation (IP) using the cells that stably express flag-tagged H2AX (f-H2AX) (Park et al, 2006). Although this interaction was shown to be dependent on IR, whether it requires S139ph was not determined. We, therefore, generated the stable cells expressing non-phosphorylatable f-H2AX in which Ser-139 is changed to Ala (f-S139A) and performed the similar chromatin IP experiments. When flag-tagged nucleosomes were precipitated from the cells after irradiation, BRG1 and hBrm were co-precipitated with f-H2AX nucleosomes as shown earlier (Park et al, 2006), but barely detectable with f-S139A nucleosomes (Figure 1A). As control, Ku70, known to bind the ends of nucleosomal DNA (Park et al, 2003), was co-precipitated equally with f-H2AX and f-S139A nucleosomes (Figure 1A). Under our experimental conditions, immunoprecipitated nucleosomes are intact as they contain the four core histones plus f-H2AX (Figure 1B) and are typically dimers or trimers depending on the conditions for chromatin fragmentation (Figure 1C). These data formally show that SWI/SNF binding to γ-H2AX nucleosomes is dependent on S139ph.

Figure 1.

SWI/SNF binds to γ-H2AX nucleosomes in S139ph-dependent manner. (A) Flag-tagged nucleosomes were immunoprecipitated from the cells stably expressing either f-H2AX or f-S139A at 1 h after 10-Gy IR, and analysed for flag-tagged histones, γ-H2AX and associating proteins by immunoblot with specific antibodies. As control, the cells containing empty vector were subjected in parallel to the nucleosome immunoprecipitation. (B) Ponceau S stain of immunoblot shows that immunoprecipitated f-H2AX nucleosomes are intact. (C) DNA of fragmented chromatin was analysed along with a size marker (M) on agarose gel.

S139ph stimulates H3 acetylation on γ-H2AX nucleosomes

We wished to understand how SWI/SNF interacts with γ-H2AX nucleosomes in S139ph-dependent manner. Two protein domains, the fork-head associated (FHA) and BRCA1 C-terminal (BRCT), have been identified to specifically recognize the phosphorylated amino-acid residues that are frequently found in proteins involved in DNA damage response (Durocher et al, 1999; Manke et al, 2003; Yu et al, 2003). We studied the sequences of BRG1/hBrm and all the associating proteins of SWI/SNF, and found that none of these proteins has FHA, BRCT or any protein domains known to recognize phosphorylated amino-acid residues. Therefore, we reasoned that SWI/SNF binds to γ-H2AX nucleosomes indirectly through other protein(s), or alternatively, directly binds to γ-H2AX nucleosomes by interacting with other histones than γ-H2AX still in the S139ph-dependent manner. As BRG1 and hBrm both have a BRD known to recognize acetylated histones (Mujtaba et al, 2007), we hypothesized the latter possibility.

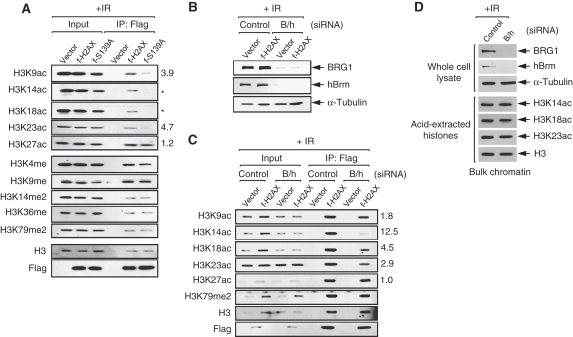

As a step towards investigating our hypothesis, we asked whether S139ph influences acetylations of other histones on γ-H2AX nucleosomes. To answer this question, we examined the effects of S139A mutation on the acetylation of H3, the core histone most heavily subjected to post-translational modifications. When we analysed the flag-tagged nucleosomes from irradiated f-H2AX or f-S139A cells for the acetylation at the conserved Lys residues of the N-terminal tails of H3, we found that the acetylations at K9, K14, K18 and K23 was largely decreased by S139A mutation with that at K14 and K18 most severely affected (Figure 2A). Interestingly, the acetylation at K27 was not affected by S139A mutation, indicating that not all acetylations on H3 are influenced by S139ph. In contrast, none of the methylations at the Lys residues of H3 analysed, including K79 known to serve as the binding site of 53BP1 DNA damage checkpoint protein (Huyen et al, 2004), was affected by S139A mutation (Figure 2A). These data indicate that S139ph positively influences the acetylation of H3 on the same and/or neighbouring nucleosomes, suggesting for the first time the existence of a crosstalk between S139ph and histone acetylation.

Figure 2.

S139ph is required for the acetylation of H3 on γ-H2AX nucleosomes. (A) Flag-tagged nucleosomes were immunoprecipitated from the cells containing empty vector, or expressing either f-H2AX or f-S139A at 1 h after 10-Gy IR, and analysed for the acetylations and methylations of H3 by immunoblot with specific antibodies. The bands of acetyl-H3 on precipitated f-H2AX and f-S139ph nucleosomes were quantitated by densitometer, and after normalization to H3 bands, the fold reduction of H3 acetylation was calculated and shown at the right side of the corresponding gel. For the gel with star mark, the fold reduction was not calculable as the band intensity of f-S139A lane is lower than background. The nomenclature of histone modifications used in this paper was followed by Turner (2005); ac, acetylation; me, monomethylation; me2, dimethylation; ph, phosphorylation. (B) Vector and f-H2AX cells were transfected with either the siRNAs specific for BRG1 or hBrm (B/h), or non-specific control siRNA. Cells were collected at 1 h after 10-Gy IR for the analysis of BRG1 and hBrm knockdown by immunoblot with specific antibodies; α-tubulin was also analysed for internal control. (C) Flag-tagged nucleosomes were immunoprecipitated from the aliquots of the cells prepared in (B) were analysed for the indicated modifications of H3 by immunoblot using specific antibodies. The fold reduction of H3 acetylation on precipitated f-H2AX nucleosomes by SWI/SNF knockdown was calculated as per in (A) and shown at the right side of the corresponding gel. (D) Cells were transfected with either control or BRG1/hBrm-specific siRNAs, and at 1 h after 10-Gy IR, whole cell lysates were prepared for the analysis of BRG1 and hBrm expression, and acid-extracted histones for the analysis of H3 acetylation as indicated.

SWI/SNF stimulates H3 acetylation on γ-H2AX nucleosomes through S139ph

The results in Figure 2A, together with our earlier finding that SWI/SNF facilitates γ-H2AX formation (Park et al, 2006), suggest that SWI/SNF stimulates H3 acetylation by facilitating S139ph. To determine whether this is the case, we knockdowned BRG1 and hBrm by specific siRNAs in f-H2AX cells (Figure 2B), and analysed the flag-tagged nucleosomes from these cells for H3 acetylation as described before. We found that the acetylations at K9, K14, K18 and K23, but not at K27, were largely decreased by SWI/SNF knockdown with K14 acetylation most dramatically affected (Figure 2C). Methylations at several lysine residues, including K79, were not affected by SWI/SNF knockdown (Figure 2C and data not shown). Importantly, the defect of H3 acetylation by SWI/SNF knockdown was not apparently detected when bulk chromatin was analysed, indicating that such effects occur preferentially on γ-H2AX nucleosomes (Figure 2D). These data, showing that SWI/SNF deficiency and S139A mutation result in the similar patterns of H3 acetylation defect, show that SWI/SNF stimulates H3 acetylation through S139ph.

BRG1 binds to γ-H2AX nucleosomes by interacting with acetylated H3 through its bromodomain

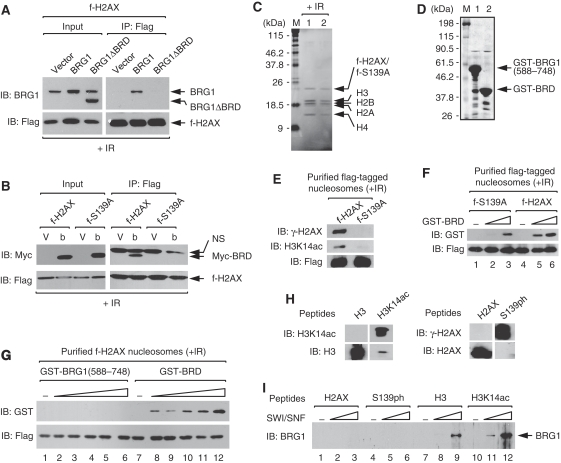

The results thus far raised the possibility that SWI/SNF may bind to γ-H2AX nucleosomes by interacting with acetylated H3 through the BRD of BRG1/hBrm. We investigated this possibility by focusing on BRG1. First, we examined whether the BRD is required for BRG1 binding to γ-H2AX nucleosomes. Flag-tagged nucleosomes were immunoprecipitated from the f-H2AX cells in which wild-type or BRD-deleted BRG1 (BRG1ΔBRD) was ectopically expressed and analysed for bound proteins. BRG1ΔBRD did not bind to γ-H2AX nucleosomes, whereas the wild-type BRG1 did as earlier seen (Figure 3A), indicating that BRD is required for BRG1 binding to γ-H2AX nucleosomes.

Figure 3.

BRG1 binds to γ-H2AX nucleosomes by interacting with acetylated H3 through its bromodomain. (A) f-H2AX cells were transfected with empty vector, or the expression vectors for the full-length BRG1 or the BRD-deleted BRG1 (BRG1ΔBRD). Flag-tagged nucleosomes were immunoprecipitated at 1 h after 10-Gy IR and analysed for associating proteins by immunoblot. (B) f-H2AX and f-S139A cells were transfected with empty vector (V) or the expression vector for myc-tagged BRG1 BRD (Myc-BRD, b). Flag-tagged nucleosomes were immunoprecipitated at 1 h after 10-Gy IR and analysed for associating proteins by immunoblot. Non-specific (NS) bands are also indicated. (C) f-H2AX (lane 1) and f-S139A (lane 2) cells were exposed to 10-Gy IR, and after 1 h, cells were collected and subjected to the affinity purification of flag-tagged nucleosomes. Coomassie stain gel of the purified nucleosomes is shown. (D) The GST proteins containing the 588–748 aa of BRG1 (lane 1) or the BRG1 BRD (lane 2) were expressed and purified from Escherichia coli, and analysed on an SDS gel with coomassie stain. (E) The purified flag-tagged nucleosomes shown in (C) were analysed for γ-H2AX and H3K14ac by immunoblot. (F) Affinity-purified f-S139A and f-H2AX nucleosomes were incubated with buffer only (lanes 1 and 4) or GST-BRD at increasing molar ratios of 1:2 (lanes 2 and 5) or 1:8 (lanes 3 and 6). Flag-tagged nucleosomes were immunoprecipitated and analysed for associating proteins by immunoblot. (G) Affinity-purified f-H2AX nucleosomes were incubated with buffer only (lanes 1 and 7) or indicated GST proteins at increasing molar ratios of 1:1 (lanes 2 and 8), 1:2 (lanes 3 and 9), 1:4 (lanes 4 and 10), 1:8 (lanes 5 and 11) or 1:16 (lanes 6 and 12). The nucleosomes were immunoprecipitated and analysed for associating proteins by immunoblot. (H) Verification of synthetic peptides by immunoblot analysis. Unmodified and K14-acetylated H3 peptides (left panel), and unmodified and S139-phosphorylated H2AX peptides (right panel) were run on 18% SDS gel and subjected to immunoblot with specific antibodies as indicated. (I) Indicated biotinylated peptides (5 μg/ml) were incubated with buffer only (lanes 1, 4, 7 and 10) or purified SWI/SNF complexes at the concentrations of 0.2 μg/ml (lanes 2, 5, 8 and 11) or 0.8 μg/ml (lanes 3, 6, 9 and 12). Peptide-protein complexes were pull downed by streptavidin-coated beads and the bead-bound proteins were analysed by immunoblot.

To determine whether BRG1 BRD is alone able to bind γ-H2AX nucleosomes in S139ph-dependent manner, the flag-tagged nucleosomes from f-H2AX and f-S139A cells in which myc-tagged BRG1 BRD (Myc-BRD) was expressed were analysed for bound proteins. As shown in Figure 3B, Myc-BRD bound to f-H2AX, but not to f-S139A, nucleosomes, indicating that BRG1 BRD is sufficient to bind to γ-H2AX nucleosomes dependently on S139ph. Therefore, the BRD of BRG1 is necessary and sufficient for the S139ph-dependent binding of BRG1 to γ-H2AX nucleosomes.

To directly show the S139ph-dependent interaction between BRG1 BRD and γ-H2AX nucleosomes, we performed in vitro pull-down experiments using affinity-purified f-H2AX and f-S139A nucleosomes (Figure 3C) and the GST proteins with BRG1 BRD (GST-BRD) purified from bacteria (Figure 3D). The purified flag-tagged nucleosomes contained the four core histones and the f-H2AX or f-S139A histones at stoichiometry. Immunoblot analysis verified that the levels of H3 acetylation were greatly reduced on f-S139A compared with f-H2AX nucleosomes as expected (Figure 3E). When incubated with purified flag-tagged nucleosomes, GST-BRD bound to f-H2AX much better than to f-S139A nucleosomes (Figure 3F). As a control, the GST proteins containing 588-748aa of BRG1 or GST alone did not bind to either nucleosomes (Figure 3G and data not shown), showing that BRG1 BRD specifically interacts with γ-H2AX nucleosomes. These data show that BRG1 BRD directly interacts with γ-H2AX nucleosomes in S139ph-dependent manner.

The results described above strongly suggest that BRG1 binds to γ-H2AX nucleosomes by interacting with acetylated H3 instead of S139ph. To determine whether this is the case, we performed in vitro pull-down assays using purified human SWI/SNF complexes and the synthetic peptides containing the sequences corresponding to H3 in the form of either non-acetylated (H3) or acetylated at K14 (H3K14ac) (Figure 3H, left panel), or the sequences corresponding to H2AX in the form of either non-phosphorylated (H2AX) or phosphorylated at S139 (S139ph) (Figure 3H, right panel). As shown in Figure 3I, BRG1 in the form of SWI/SNF complex preferentially binds to H3K14ac over H3 peptides; however, it did not bind to H2AX or S139ph peptides. Taken all together, the results collectively show that SWI/SNF binds to γ-H2AX nucleosomes in S139ph-dependent manner by interacting with acetylated H3 through BRG1 BRD rather than by interacting with S139ph itself.

BRG1 binding to γ-H2AX nucleosomes is important for S139ph and DSB repair

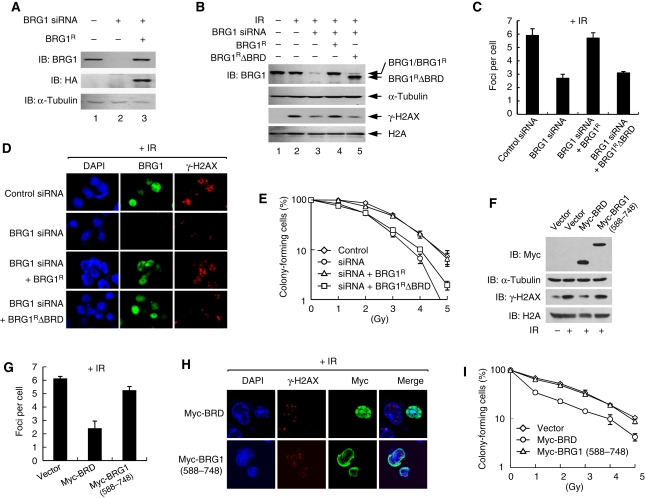

Having found the mechanisms for the interaction between SWI/SNF and γ-H2AX nucleosomes, we wanted to investigate whether the interruption of this interaction would affect the earlier defined functions of SWI/SNF in γ-H2AX formation and DSB repair (Park et al, 2006). To this end, we generated the expression vector for the silent mutant form of BRG1 whose expression is resistant to the BRG1-specific siRNA (BRG1R), as well as the expression vector for BRG1R lacking BRD (BRG1RΔBRD). First, we verified that BRG1R could be expressed in the cells in which BRG1 was knockdowned by siRNA and that the expression levels of BRG1R were similar to those of the endogenous BRG1 (Figure 4A). We then examined the effects of BRD deletion on the ability of BRG1 to stimulate S139ph after DNA damage by immunoblot. As shown in Figure 4B, BRG1RΔBRD failed to rescue the defect of S139ph induced by BRG1 knockdown, whereas BRG1R completely rescued this defect. Virtually, the same results were obtained when the effects of BRD deletion on the formation of γ-H2AX foci were examined using immunofluorescence microscopy (Figure 4C and D). Similar rescue experiments showed that BRG1R completely rescued the defect of cell survival after DNA damage in BRG1-knockdowned cells, whereas BRG1RΔBRD did not (Figure 4E). These data show that the BRD is critical for the BRG1's functions for γ-H2AX formation and DSB repair.

Figure 4.

BRG1 binding to γ-H2AX nucleosomes is important for S139ph and DSB repair. (A) Cells were cotransfected with non-specific (lane 1) or BRG1-specific siRNAs (lanes 2 and 3), plus either empty vectors (lanes 1 and 2) or the expression vectors for HA-tagged siRNA-resistant BRG1 (BRG1R) (lane 3). Whole cell lysates were analysed for the expression of BRG1 and BRG1R by immunoblot. (B) Cells were cotransfected with non-specific (lanes 1 and 2) or BRG1-specific siRNAs (lanes 3–5), plus either empty vectors (lanes 1–3) or the expression vectors for BRG1R (lane 4) or BRD-deleted BRG1R (BRG1RΔBRG1, lane 5). At 1 h after untreated (lane 1) or 10-Gy IR (lanes 2–5), cells were collected to prepare whole cell lysates and acid-extracted histones for immunoblots with anti-BRG1 or anti-γ-H2AX antibodies, respectively; α-tubulin and H2A were also analysed for loading control. (C) Cells were transfected as described in lanes 2–5 of (B) and exposed to 2-Gy IR. After 1 h, cells were fixed and dually stained with anti-BRG1 or anti-γ-H2AX antibodies before confocal images were captured. Average number of γ-H2AX foci per cell was depicted as graph by counting at least 50 cells. The error bar indicates mean±s.d. of three independent experiments. (D) Representative confocal images from the experiments in (C) are shown. (E) Cells transfected as per in (D) were untreated (0 Gy) or exposed to 1–5 Gy IR before the viability was determined by colony formation assays with triplicates per sample. The graph shows average number of colonies with mean±s.d. of four independent experiments. (F) Cells were transfected with empty or Myc-BRD expression vectors. At 1 h after 10-Gy IR, cells were collected to prepare whole cell lysates and acid-extracted histones for immunoblots with anti-Myc or anti-γ-H2AX antibodies, respectively; α-tubulin and H2A were also analysed for loading control. (G) Cells transfected with empty, Myc-BRD or Myc-BRG1(588–748) vectors were irradiated by 2 Gy, and after 1 h, cells were fixed for dual staining with the antibodies against Myc or γ-H2AX. The Myc-BRG1(588–748) vector expresses the sequences of 588–748 amino acids of BRG1, outside the BRD, and was used as a control. Average number of γ-H2AX foci per cell was depicted as graph by counting at least 50 each of untransfected and transfected cells. The error bar indicates mean±s.d. of three independent experiments. (H) Representative confocal images from the experiments in (G) are shown. (I) Cells were transfected with indicated vectors, and after irradiation, cells were subjected to colony formation assays as described in (E). The graph shows average number of colonies with mean±s.d. of three independent experiments.

Finally, we determined whether the BRD of BRG1, when overexpressed in the cells, could interfere with the BRG1's functions for γ-H2AX formation and DSB repair. We found that overexpression of Myc-BRD in the cells compromises S139ph (Figure 4F) and γ-H2AX focus formation (Figure 4G and H) as well as the cells' ability to survive DNA damage (Figure 4I), indicating that BRG1 BRD can function as dominant-negative inhibitors of BRG1 in γ-H2AX formation and DSB repair. Therefore, blocking the interaction between BRG1 and γ-H2AX either by deletion or overexpression of the BRG1 BRD leads to loss of the BRG1's ability to facilitate S139ph and DSB repair, showing the importance of SWI/SNF binding to γ-H2AX nucleosomes for these processes.

H3 acetylation is required for BRG1 binding to γ-H2AX nucleosomes

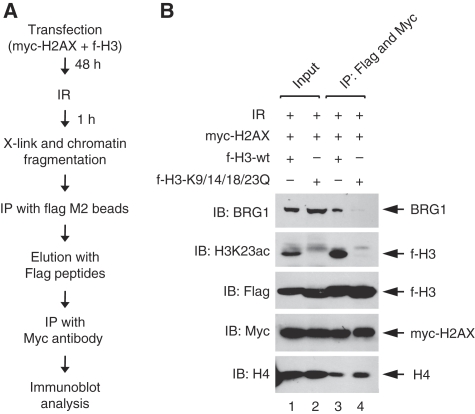

As our results showed that BRG1 binds to γ-H2AX nucleosomes through acetylated H3, we wanted to ask whether H3 acetylation is indeed required for this binding. For this, we generated a pair of plasmid constructs expressing flag-tagged H3 (f-H3) either in wild-type or the mutant forms in which the four N-terminal Lys residues (K9, K14, K18 and K23) were all changed to Gln, and also generated a construct expressing myc-tagged H2AX (myc-H2AX). We transfected 293T cells with myc-H2AX together with wild-type or mutant f-H3 vectors, and 1 h after irradiation, we sequentially immunoprecipitated the nucleosomes containing both f-H3 and myc-H2AX from these cells and analysed them for bound BRG1 (Figure 5A). Strikingly, the BRG1 binding to these nucleosomes was largely diminished by the mutation of the four acetylation sites of H3 (Figure 5B). These data, therefore, show that H3 acetylation is crucial for the BRG1 binding to γ-H2AX nucleosomes.

Figure 5.

H3 acetylation is required for the binding of BRG1 to γ-H2AX nucleosomes. (A) The experimental procedure used in (B) is represented as a schematic flow chart. See Materials and methods for details. (B) 293T cells were transfected with myc-H2AX plus either f-H3-wt (lanes 1 and 3) or f-H3-K9/14/18/23Q vectors (lanes 2 and 4), and irradiated by 10 Gy 1 h before harvest. f-H2AX nucleosomes were immunoprecipitated using anti-Flag M2 beads and eluted with Flag peptides, and the Flag-eluted nucleosomes were then subjected to the second immunoprecipitation by Myc antibody followed by immunoblot analysis as indicated. The K to Q mutations for the four acetylation sites were verified by DNA sequencing (Materials and methods) as well as by immunoblot analysis with specific antibodies (here and data not shown). H4 was also analysed to monitor the integrity of the precipitated nucleosomes.

Gcn5 is responsible for the H3 acetylation on γ-H2AX nucleosomes

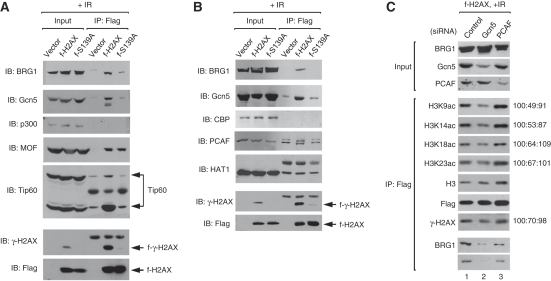

To understand how γ-H2AX stimulates H3 acetylation, we sought for the histone acetyltransferases (HATs) that are responsible for this mechanism. We reasoned that such HATs are likely to interact with γ-H2AX nucleosomes in S139ph-dependent manner, and examined several HATs with respect to this characteristic. We initially considered the HATs that have activity towards H3 and also has been shown to be implicated in DNA repair; those are Gcn5/KAT2A, p300/KAT3B and their closely related HATs, PCAF/KAT2B and CBP/KAT3A, respectively (Tamburini and Tyler, 2005; Allis et al, 2007; Das et al, 2009). We immunoprecipitated flag-tagged nucleosomes from irradiated f-H2AX and f-S139A cells, and analysed these nucleosomes for bound HATs by immunoblot using specific antibodies. As shown in Figure 6A and B, among the four HATs tested, only Gcn5 binds to γ-H2AX nucleosomes in S139ph-dependent manner, making this protein a strong candidate for the right HAT.

Figure 6.

Gcn5 is responsible for the γ-H2AX-mediated H3 acetylation. (A, B) To search for the HATs that bind to γ-H2AX nucleosomes in the S139ph-specific manner, all the HATs earlier shown to be implicated in DNA repair were examined by the similar experiments as described in Figure 1. Several independent sets of experiments were performed to test some subgroups of HATs in each of which the specific interaction between BRG1 and γ-H2AX nucleosomes was always monitored to control the chromatin IP experiments. The results of two representative experimental sets are shown. The specific interaction between Gcn5 and γ-H2AX nucleosomes was also included in the experimental set shown in (B). (C) Gcn5 knockdown reduces the acetylation of H3 on γ-H2AX nucleosomes. f-H2AX cells were transfected with non-specific (lane 1), Gcn5- (lane 2) or PCAF-specific siRNAs (lane 3), and at 1 h after 10-Gy IR, cells were fixed and sonicated for the preparation of fragmented chromatin lysate (Input). f-H2AX nucleosomes were immunoprecipitated and divided into two to analyse the levels of H3 acetylation and the binding of BRG1 and Gcn5 to f-H2AX nucleosomes in separate gels as indicated. The levels of γ-H2AX on f-H2AX nucleosomes was also analysed using the same blot as used for the analysis of H3 acetylation. The input lysate was analysed for siRNA knockdown of Gcn5 and PCAF as well as for the levels of BRG1. The relative band intensity of acetyl-H3 and γ-H2AX after normalization to H3 and f-H2AX bands, respectively, is shown next to the corresponding gel.

To investigate whether Gcn5 is responsible for the acetylation of H3 on γ-H2AX nucleosomes, we knockdowned Gcn5 as well as PCAF for control in f-H2AX cells and immunoprecipitated flag-tagged nucleosomes from the cells after irradiation. When we analysed these nucleosomes, we found that the levels of H3 acetylation on γ-H2AX nucleosomes were reduced by Gcn5, but not PCAF, knockdown and that the decrease of H3 acetylation by Gcn5 knockdown was observed for all four acetylation sites analysed (K9, K14, K18 and K23) (Figure 6C). Consistent with these and described earlier results, the BRG1 binding to γ-H2AX nucleosomes and the levels of S139ph on these nucleosomes were concomitantly reduced by Gcn5 knockdown (Figure 6C). These data show that Gcn5 is indeed responsible for the acetylation of H3 on γ-H2AX nucleosomes.

Next, we examined the second group of HATs, which, although not having activity towards H3, have been implicated in DNA repair, with respect to the specific binding to γ-H2AX nucleosomes; those are HAT1/KAT1, Tip60/KAT5 and HMOF/MYST1/KAT8 (Qin and Parthun, 2002; Gupta et al, 2005; Taipale et al, 2005; Squatrito et al, 2006; Allis et al, 2007). We performed the similar experiments as mentioned above and found that only Tip60 displayed the specific interaction with γ-H2AX (Figure 6A). Evidence suggests that Tip60 is involved in the DSB response at multiple levels including ATM activation and DNA repair (Squatrito et al, 2006). Although we did not pursue further investigation in this study partly because Tip60 has been shown to acetylate H4 but not H3 both on reconstituted nucleosomes in vitro and on the chromatin around a DSB in vivo (Ikura et al, 2000; Murr et al, 2006), it is possible that Tip60 mediates H4 acetylation on γ-H2AX nucleosomes as much the same way as Gcn5 does the H3 acetylation.

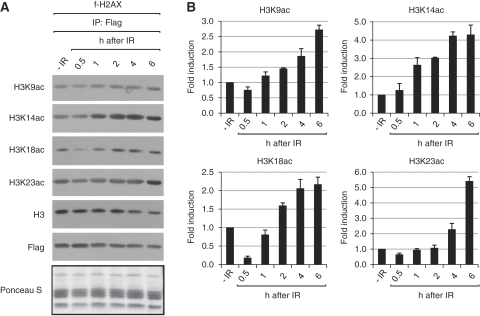

IR induces the acetylation of H3 on γ-H2AX nucleosomes

Having found that H3 acetylation on γ-H2AX nucleosome is stimulated by S139ph, we wanted to examine whether this modification is induced by DNA damage. For this, we compared the levels of H3 acetylation on immunoprecipitated f-H2AX nucleosomes before and after irradiation at various time points. The results are shown in Figure 7. Although the acetylations of H3 at K9, K14, K18 and K23 on γ-H2AX nucleosomes all increased after irradiation, they showed some variations in both the magnitude of induction and the time-course kinetics. For examples, whereas the K14 acetylation continually increases up to 6 h post-irradiation, other acetylations show a transient decrease at early time points. The magnitude of the IR induction of H3 acetylation at each time point somewhat varies among different sites. Although further investigation will be necessary to understand the biological significance of these results, the data minimally show that the acetylation of H3 on γ-H2AX is indeed induced by DNA damage.

Figure 7.

IR induces H3 acetylation on γ-H2AX nucleosomes. (A) f-H2AX cells were left untreated (−IR) or irradiated by 10 Gy, and the irradiated cells were harvested after various times. f-H2AX nucleosomes were immunoprecipitated from those cells and subjected to immunoblot analysis using specific antibodies. The immunoblot membrane stained with Ponceau S before incubation with antibodies is shown below the gel. (B) The quantitation data for the gel in (A) is shown. The bands of acetyl-H3 were quantitated by densitometer, and after normalization to H3, the fold induction of H3 acetylation was calculated and shown next to the corresponding gel. The error bar indicates mean±s.d. of three independent experiments.

Discussion

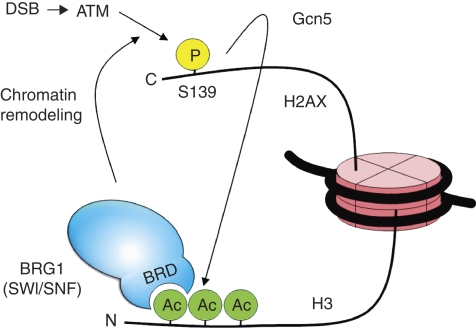

We initiated this work to investigate the specific interaction between SWI/SNF and γ-H2AX nucleosomes. We now have elucidated not only the molecular mechanism for this interaction, but also have discovered a novel crosstalk among a chromatin remodelling complex and two different types of histone modifications for DNA repair. By integrating the results in this work with our earlier finding for SWI/SNF stimulation of γ-H2AX, we propose the model of a cooperative activation loop among SWI/SNF, γ-H2AX and H3 acetylation for DSB repair (Figure 8). DSB-activated ATM initiates S139ph and establishes low levels of γ-H2AX on the chromatin around a DSB. γ-H2AX triggers the acetylation of H3 within the same and/or neighbouring nucleosomes by recruiting HATs such as Gcn5 to these nucleosomes. SWI/SNF then binds to γ-H2AX nucleosomes by interacting with the acetylated H3 using the BRD of BRG1. Recruited SWI/SNF in turn facilitates ATM-mediated S139ph probably by increasing the accessibility of nucleosomes around the DSB. The increased S139ph leads to further acetylation of H3 and more accumulation of SWI/SNF at γ-H2AX nucleosomes. This positive feedback loop among SWI/SNF, S139ph and H3 acetylation eventually establishes the high levels of γ-H2AX for efficient DSB response.

Figure 8.

A model for the cooperative action of SWI/SNF, S139ph and H3 acetylation during DSB repair. For clarity, only BRG1 subunit is shown for the SWI/SNF complex. See text for details.

Although recent studies have clearly documented the interaction between chromatin remodelling complex and γ-H2AX, the mechanisms for this interaction and its biological meaning for DSB repair have remained obscure. In this study, we found an unexpected way that a chromatin remodeller interacts with γ-H2AX. As depicted in our model, SWI/SNF complexes can specifically bind to γ-H2AX nucleosomes without interacting with γ-H2AX itself. This mode of molecular interaction would have advantages to keep γ-H2AX still available for carrying out its functions such as ATM recruitment for elevating its own levels, even if SWI/SNF is being bound to the γ-H2AX nucleosome. Thus, SWI/SNF and γ-H2AX can function in synergy without physically interfering with each other. Our model, therefore, can explain how SWI/SNF interacts specifically with γ-H2AX and yet stimulates γ-H2AX formation (Park et al, 2006). In addition, given the importance of histone acetylation in the DBS response (Downs et al, 2007), the cooperative activation loop among SWI/SNF, γ-H2AX and H3 acetylation may provide an efficient mechanism for rapid and synchronous accumulation of H2AX phosphorylation and histone acetylation within DNA lesions. Our work, therefore, provides important insights into the understanding of how chromatin remodellers cooperate with histone modifications during the DSB response.

γ-H2AX has a central function in recruiting and accumulating specific proteins at DSB-surrounding chromatin in response to DNA damage. Recent studies have shown that the crosstalk between γ-H2AX and the ubiquitination of H2A/H2B is important for these processes (van Attikum and Gasser, 2009). Our work here revealed a novel crosstalk between γ-H2AX and H3 acetylation, thus expanding the types of histone modifications that γ-H2AX cooperates with during the DSB response. In addition, as depicted in our model, the crosstalk between γ-H2AX and H3 acetylation is bidirectional such that the two modifications stimulate with each other. It should be noted that our screen for identifying S139ph-induced histone modifications was not exhaustive, therefore, leaving open the possibility that more such types of histone modifications can be discovered.

We show that Gcn5 is responsible for the mechanism by which S139ph stimulates H3 acetylation on γ-H2AX nucleosomes. Gcn5 binds to γ-H2AX nucleosomes in S139ph-dependent manner and its knockdown results in a decrease of H3 acetylation on γ-H2AX nucelosomes as well as a diminished BRG1 binding to γ-H2AX nucleosomes. Thus, it is possible that Gcn5 is recruited to DSBs through γ-H2AX and acetylates H3 on the chromatin around the DSBs. Gcn5 has been shown in yeast to be specifically recruited to the HO-induced DSB and required for efficient DNA repair, although the mechanism for the Gcn5 recruitment is not known, suggesting that the function of this HAT in the DSB response is evolutionarily conserved (Tamburini and Tyler, 2005). Our data also suggest that Gcn5 can acetylate H3 at the sites of K9, K14, K18 and K23 on γ-H2AX nucleosomes. In agreement with our results, human Gcn5 was recently shown to acetylate H3K9 in vitro and in vivo (Tjeertes et al, 2009), and yeast Gcn5 was shown to preferentially acetylate H3K14 among the four core histone substrates in vitro (Kuo et al, 1996; Grant et al, 1999). It is of great interest to see whether Gcn5 indeed acetylates H3 on γ-H2AX nucleosomes in the S139ph-dependent manner in a defined reconstituted system. Interestingly, Gcn5 has a BRD in the C-terminal, and it is possible that this HAT, such as BRG1, interacts with γ-H2AX nucleosomes through acetylated histones. The exact function of Gcn5 in the DSB response and the mechanism for its specific interaction with γ-H2AX nucleosomes remain to be elucidated.

Evidence suggests that the acetylation of the conserved N-terminal Lys residues of H3 is important for DSB repair. It has been shown that mutation of these Lys or deletion of the genes for corresponding HATs compromises DSB repair (Bird et al, 2002; Qin and Parthun, 2002; Tamburini and Tyler, 2005; Murr et al, 2006). It also has been shown that Gcn5, HAT1, Tip60 and Esa1 (the yeast orthologue of Tip60) are recruited to the HO-induced DSB, and that the levels of H3 acetylation increase around the DSB (Downs et al, 2004; Tamburini and Tyler, 2005; Murr et al, 2006; Qin and Parthun, 2006). Our data, showing that IR induces the acetylation of H3 at the four N-terminal Lys residues on γ-H2AX nucleosomes, further emphasizes the importance of H3 acetylation in the DSB response. Importantly, the IR induction of H3 acetylation seems to occur preferentially, even if not exclusively, on γ-H2AX nucleosomes as such effect is not easily detectable for bulk histones (data not shown). Therefore, our approach of subjecting γ-H2AX nucleosomes, instead of bulk histones, to analysis proves valuable for identifying DNA damage-specific histone modifications.

Histone acetylation at DSBs can be expected to assist repair process by directly affecting nucleosome stability and/or by functioning as signals for recruiting specific repair complexes as the histone code hypothesis predicts (Strahl and Allis, 2000). Our results, showing that BRG1 binds to γ-H2AX nucleosomes by interacting with acetylated H3, provide the first evidence that histone acetylation can function as a signal for recruiting specific proteins to DNA lesion. In this context, it is tempting to hypothesize that the acetylation of the N-terminal tail of H3, in particular at K14, can function as a histone code for DSB repair. Several lines of experimental evidence support this hypothesis. First, the S139A mutation, while having no effect on methylation in general, reduces the acetylation of H3 preferentially at some particular sites including K14, and BRG1 knockdown most severely impairs the acetylation of H3 at K14 among the five different sites analysed on γ-H2AX nucleosomes (Figure 2). Second, the Gln substitution for the four N-terminal Lys residues of H3, including K14, diminished the BRG1 binding to γ-H2AX nucleosomes (Figure 5). Third, the H3K14 acetylation is alone sufficient for BRG1 to interact with H3 peptides in an acetylation-dependent manner (Figure 3H and I). Fourth, the in vitro binding study using several acetylated histone peptides identified H3K14 to be the dominant substrate of the BRG1 BRD (Shen et al, 2007). Fifth, the acetylation of H3K14 on γ-H2AX nucleosomes is induced by IR with relatively fast kinetics and high magnitude compared with other sites (Figure 7). Finally, as earlier mentioned, Gcn5 has substrate specificity preferentially towards H3K14 among the four core histones (Kuo et al, 1996; Grant et al, 1999), and our data suggest that Gcn5 can acetylate H3K14 by specifically interacting with γ-H2AX nucleosomes (Figure 6). Interestingly, the recruitment of BRG1 to the INF-β promoter has been shown to be mediated by H4K8 acetylation (Agalioti et al, 2002). Thus, the H3K14 acetylation, in conjunction with γ-H2AX, may function as a repair-specific histone code to confine BRG1 to the repair process in distinction from transcription.

Materials and methods

Stable cells and antibodies

293T cells stably expressing f-H2AX has been described earlier (Park et al, 2006), and f-S139A-expressing cells were generated in the similar way. The polyclonal antibodies against γ-H2AX (07-164) and H2AX (2595) were purchased from Upstate, and produced by immunizing rabbits with synthetic peptides, CKATQA[pS]QEY and CKATQASQEY, respectively (AbFrontier). The following antibodies were purchased from Upstate: H2A (07-146), H3 (06-755), H3K9ac (07-352), H3K14ac (06-911), H3K18ac (07-354), H3K23ac (07-355), H3K27ac (07-360), H3K4me2 (07-030, anti-dimethyl-Histone H3 at Lys4), H3K9me (07-395), H3K14me2 (07-427) and H3K36me (07-548). The sources of other antibodies are as follows: BRG1 (sc-10768), Santa Cruz; H3K79me2 (ab3594, anti-dimethyl-Histone H3 at Lys79), Abcam; HA (sc-7392), Santa Cruz; Flag (F7425), Sigma; hBrm (610389), BD biosciences; Ku70 (sc-9033), Santa Cruz; α-Tubulin (sc-8035), Santa Cruz; c-Myc (SA-294), BIOMOL; all the HATs used in this work were from Santa Cruz.

Plasmid construction

All the plasmid constructs generated in this work were verified by sequencing. The f-S139A expression vector was generated by subjecting the f-H2AX vector (Park et al, 2006) to site-directed mutagenesis with the QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene), using the following oligonucleotides: 5′-GCGCAGATCTGGATCGGGCCGCGGCAAGAC and 5′-GCGCGGATCCTTAGTACTCCTGGGCGGCCT.

pBJ5-BRG1 (a gift from Anthony Imbalzano) was used as the wild-type BRG1 expression vector; this vector was verified by sequencing to encode the full-length human BRG1 with HA tag at the C-terminal. The expression vector for BRG1 lacking bromodomain (BRD), pBRG1ΔBRD, was generated by cloning the sequences amplified by PCR from pBJ-BRG1 into the NheI and EcoRV sites of pcDNA3.1-myc-HisA(-) (Invitrogen)—the PCR primers are as follows: 5′-GCTAGCGATGTCCACTCCAGACCCACCCCTGGGCGG and 5′-GATATCCTCGTCGTCGGGCACCTCGT.

pBRG1R, the expression vector for the silent mutant form of BRG1 whose expression is resistant to the BRG1 siRNA, was generated by subjecting pBJ-BRG1 to site-directed mutagenesis as described above, using the following oligonucleotides: 5′-AGCGCTGGAGACAGCTTTGAACGCTAAGGCCTACAAG and 5′-CCTTAGCGTTCAAAGCTGTCTCCAGCGCTGTGTCC. pBRG1RΔBRD, the expression vector for the siRNA-resistant BRG1 lacking BRD, was generated by subjecting pBRG1ΔBRD to site-directed mutagenesis as described above, using the following oligonucleotides: 5′-AGCGCTGGAGACAGCTTTGAACGCTAAGGCCTACAAG and 5′-CCTTAGCGTTCAAAGCTGTCTCCAGCGCTGTGTCC.

pMyc-BRD and pMyc-BRG1(588–748), the expression vectors for myc-tagged BRG1 BRD and myc-tagged BRG1588–748, respectively, were generated by inserting PCR products of pBJ-BRG1 into the XhoI and NotI sites of pCMV/myc/nuc (Invitrogen)—the PCR primers are as follows: the former, 5′-CTCGAGATGCCACCCAACCTCACCAAG, 5′-GCGGCCGCCTTCTCGATTTTCTG and the latter, 5′-GCTCGTCGACACCATGAAGGCAGAAAATGCAGAAGGAC and 5′-GCTCGCGGCCGCAAGCGCTGACTGCTTGTCCACTCT.

pGST-BRD, the expression vector for the BRG1 BRD fused with GST, was generated by inserting the DNA fragments amplified by PCR from pBJ-BRG1 into the BamHI and EcoRI sites of pGEX-2TK—the PCR primers are as follows: 5′-GCTCGGATCCATGCCACCCAACCTCACC and 5′-GCTCGAATTCGCTTCTCGATTTTCTGCCG. In the similar ways, pGST-BRG1 (588–748), the expression vector for the amino-acid sequences corresponding to BRG1588–748 fused with GST, was generated using the PCR primers as follows: 5′-GCTCGGATCCAAGGCAGAAAATGCAGAA-3′ and 5′-GCTCGAATTCGAAGCGCTGACTGCTTGTC-3′.

The myc-H2AX expression vector was generated by inserting the PCR product of the human H2AX cDNA sequence into the BamH1 and EcoRI sites of pcDNA3.1/myc-His A using the PCR primers as follows: 5′-GCGCGGATCCATGTCGGGCCGCGGC and 5-GCGCGAATTCGTACTCCTGGGAGGC. The expression vector for f-H3 was generated by cloning the PCR-amplified human H3 cDNA sequences into the EcoRI and BamH1 sites of the p3xFLAG-CMV-14 vector (Sigma) to generate the Flag-H3 vector. The sequences of the PCR primers are as follows: 5′-GCGCGAATTCATGGCCCGTACTAAG and 5′-GCGCGGATCCAGCCCGCTCTCCACG. The expression vector for the mutant f-H3 was generated by site-directed mutagenesis (QuikChange kit, Stratagene) using the f-H3 vector as a template. The oligonucleotides used are as follows: K9Q, 5′-TAAGCAGACTGCTCGCCAATCGACCGGCGGCAAGGCCCCGAGG and 5′-CCTCGGGGCCTTGCCGCCGGTCGATTGGCGAGCAGTCTGCTTA; K14Q, 5′-CAAGTCGACCGGCGGCCAAGCCCCGAGGAAGCAGCTGGCCACC and 5′-GGTGGCCAGCTGCTTCCTCGGGGCTTGGCCGCCGGTCGACTTG; K18Q, 5′-CGGCAAGGCCCCGAGGCAACAGCTGGCCACCAAGGCGGCCCGC and 5′-GCGGGCCGCCTTGGTGGCCAGCTGTTGCCTCGGGGCCTTGCCG; K23Q, 5′-GAAGCAGCTGGCCACCCAAGCGGCCCGCAAGAGCGCGCCGGCC and 5′-GGCCGGCGCGCTCTTGCGGGCCGCTTGGGTGGCCAGCTGCTTC.

IP of flag-tagged nucleosomes

Approximately 6 × 107 293T cells stably expressing f-H2AX or f-S139A were fixed with 1% formaldehyde on ice for 10 min followed by incubation with 0.1 M glycine for 5 min. Cells were collected and, after PBS wash, resuspended in 2.5 ml of NETN buffer (20 mM Tris–Cl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 0.5% NP40, 0.1 mM PMSF, protease inhibitor cocktail). Cell suspension was sonicated nine times for 10 s at 30% amplitude setting using Cole-Parmer 400 Watt Ultrasonic Homogenizer (these conditions produce chromatin fragments with the average length of about 500 bp in DNA). Lysates were centrifuged at 8000 g for 10 min, and the supernatant was taken and incubated with protein G sepharose at 4°C for 2 h. Pre-cleared supernatant was incubated with 5 μl of anti-Flag M2 affinity gel (Sigma) at 4°C for overnight. After washing four times with NETN buffer, pellet was suspended in sample loading buffer and boiled for 5 min before being subjected to SDS–PAGE and immunoblot analysis.

Purification of flag-tagged nucleosomes

Approximately 5 × 107 of 293T cells stably expressing f-H2AX or f-S139A were suspended in 900 μl of HNB buffer (0.5 M sucrose, 15 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 60 mM KCl, 0.25 mM EDTA pH 8, 0.125 mM EGTA, 0.5 mM spermidine, 0.15 μM spermine, 1 mM DTT, protease inhibitor cocktail) followed by centrifugation at 6000 g at 4°C for 5 min. Cell pellet was added dropwise by 300 μl of HNB containing 1% NP40 and incubated on ice for 5 min. Nuclei were isolated by centrifugation at 6000 g at 4°C for 5 min, and resuspended in 600 μl of nuclear buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 70 mM NaCl, 20 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 3 mM CaCl2, protease inhibitor cocktail). Nuclei suspension was added by 1.5 units of micrococcal nuclease (Sigma, N3755-200UN) and incubated at 37°C for 10 min, and the reactions were stopped by addition of 5 mM EDTA and 5 mM EGTA on ice (these conditions produce chromatin fragments with the average length of 200 bp in DNA). After centrifugation at 5000 g at 4°C for 5 min, supernatant was taken and incubated with anti-Flag M2 agarose at 4°C overnight with rocking. After washing several times, flag-tagged nucleosomes were eluted by incubation with 1.5 μg of the Flag peptides (Sigma) in 1 × TBS at 4°C for 30 min.

GST proteins and nucleosome-binding experiments

BL-21 cells containing the expression vectors for GST-BRD or GST-BRG1(588–748) were induced for the expression of GST fusion proteins by addition of IPTG at a final concentration of 0.4 mM. Cells were harvested and resuspended in 10 ml of the buffer (25 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 10 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM PMSF) and added by 80 mg of lysozyme for 10 min at RT followed by sonication. After mixing with 10 ml of lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 2% Triton X-100, 4 mM NaH2PO4, 16 mM Na2HPO4, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM PMSF), the lysate was clarified by centrifugation. Supernatant was taken and incubated with equilibrated glutathione beads at 4°C overnight with rocking and then poured into a syringe column. After extensive washing, GST fusion proteins were eluted with elution buffer containing 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0 and 5 mM glutathione (reduced form). Eluted proteins were dialysed against the buffer containing 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM DTT and 20% glycerol.

Purified f-H2AX nucleosomes were incubated with GST-BRD or GST-BRG1(588–748) in 1 ml of total reaction volume containing the binding buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP40, 0.1 mg/ml of BSA, 100 mM NaF, phosphatase inhibitor cocktail) at 4°C for 2 h, and the reactions were added by 5 μl of anti-Flag M2 agarose at 4°C overnight with rocking. After washing with the binding buffer several times, pellet was suspended in sample loading buffer and boiled for 5 min before being subjected to SDS–PAGE and immunoblot analysis.

Peptide pull-down assays

S139ph and H3K14ac peptides were synthesized from American Peptide Company, Inc, and the corresponding unmodified H2AX and H3 peptides from Peptron (Daejeon, Korea); the modifications were verified by immunoblot analysis (Figure 3H). The peptides sequences are as follows: H2AX, Biotin-TVGPKAPSGGKKATQAS QEY; S139ph, Biotin-TVGPKAPSGGKKATQAS(PO3H2)QEY; H3, Biotin-TKQTARKSTGGKAPRKQLAT; H3K14ac, TKQTARKSTGGK(COCH3)APRKQLAT. For pull-down experiments, 5 μg of peptides were incubated with 0.2 or 0.8 μg of the SWI/SNF complexes purified from HeLa cells (Kwon et al, 2000) in 1 ml reaction containing 50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP40, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, 100 mM NaF and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail. SWI/SNF-bound peptides were coupled to streptavidin-coated Dynal beads M-280 (Dynal). After extensive washing with the binding buffer, beads were separated by the magnet (Dynal MPC-S) and bead-bound proteins were analysed by immunoblot.

siRNA and plasmid transfection

All transfections in this work were performed by calcium phosphate method. The sequences of siRNA are as follows: BRG1, 5′-AGACAGCCCUCAAUGCUAAUU and 5′-PUUAGCAUUGAGGGCUGUCUUU; non-specific control, 5′-CCUACGCCACCAAUUUCGUUU and 5′-ACGAAAUUGGUGGCGUAGGUU. Cotransfection with BRG1 and hBrm siRNA was performed as described earlier (Park et al, 2006). siRNAs for GCN5 (sc-37946) and PCAF(sc-36198) were purchased from Santa Cruz. It is noted that transfection with BRG1 siRNA leads to downregulation of both BRG1and hBrm probably because BRG1 positively regulates the hBrm expression as discussed earlier (Park et al, 2006).

Sequential double IP of the nucleosomes containing myc-H2AX and f-H3

Approximately 2 × 107 293T cells were transfected with appropriate vectors by calcium phosphate method, and subjected to IP with ant-Flag M2 agarose as described before. After washing four times with TBS, the precipitated nucleosomes were eluted with 3 × FLAG peptides, and the eluate were then incubated with anti-Myc antibodies at 4°C for overnight followed by incubation of protein G beads for 1 h. After washing with the NETN buffer several times, pellet was suspended in SDS–PAGE sample buffer and boiled for 5 min before being subjected to SDS–PAGE and immunoblot analysis.

Immunofluorescence microscopy, colony formation assays, histone extraction and immunoblot analysis

These experiments were performed as described earlier (Park et al, 2006, 2009).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the grant to JK (R01-2007-000-10571-0) from the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation (KOSEF) funded by the Korea Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (MEST), the Molecular and Cellular BioDiscovery Research Program (M10748000334-08N4800-33410, grant to JK) from the KOSEF funded by MEST, and partly by grant No. R15-2006-020 from the National Core Research Center (NCRC) program of MEST and KOSEF through the Center for Cell Signaling and Drug Discovery Research at Ewha Womans University. JHP was supported by RP-Grant 2009 of Ewha Womans University.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Agalioti T, Chen G, Thanos D (2002) Deciphering the transcriptional histone acetylation code for a human gene. Cell 111: 381–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allard S, Masson JY, Cote J (2004) Chromatin remodeling and the maintenance of genome integrity. Biochim Biophys Acta 1677: 158–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allis CD, Berger SL, Cote J, Dent S, Jenuwien T, Kouzarides T, Pillus L, Reinberg D, Shi Y, Shiekhattar R, Shilatifard A, Workman J, Zhang Y (2007) New nomenclature for chromatin-modifying enzymes. Cell 131: 633–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao Y, Shen X (2007) Chromatin remodeling in DNA double-strand break repair. Curr Opin Genet Dev 17: 126–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird AW, Yu DY, Pray-Grant MG, Qiu Q, Harmon KE, Megee PC, Grant PA, Smith MM, Christman MF (2002) Acetylation of histone H4 by Esa1 is required for DNA double-strand break repair. Nature 419: 411–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner WM, Redon CE, Dickey JS, Nakamura AJ, Sedelnikova OA, Solier S, Pommier Y (2008) GammaH2AX and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 8: 957–967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai B, Huang J, Cairns BR, Laurent BC (2005) Distinct roles for the RSC and Swi/Snf ATP-dependent chromatin remodelers in DNA double-strand break repair. Genes Dev 19: 1656–1661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das C, Lucia MS, Hansen KC, Tyler JK. (2009) CBP/p300-mediated acetylation of histone H3 on lysine 56. Nature 459: 113–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doil C, Mailand N, Bekker-Jensen S, Menard P, Larsen DH, Pepperkok R, Ellenberg J, Panier S, Durocher D, Bartek J, Lukas J, Lukas C (2009) RNF168 binds and amplifies ubiquitin conjugates on damaged chromosomes to allow accumulation of repair proteins. Cell 136: 435–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downs JA, Allard S, Jobin-Robitaille O, Javaheri A, Auger A, Bouchard N, Kron SJ, Jackson SP, Cote J (2004) Binding of chromatin-modifying activities to phosphorylated histone H2A at DNA damage sites. Mol Cell 16: 979–990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downs JA, Nussenzweig MC, Nussenzweig A (2007) Chromatin dynamics and the preservation of genetic information. Nature 447: 951–958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durocher D, Henckel J, Fersht AR, Jackson SP (1999) The FHA domain is a modular phosphopeptide recognition motif. Mol Cell 4: 387–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant PA, Eberharter A, John S, Cook RG, Turner BM, Workman JL (1999) Expanded lysine acetylation specificity of Gcn5 in native complexes. J Biol Chem 274: 5895–5900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Sharma GG, Young CS, Agarwal M, Smith ER, Paull TT, Lucchesi JC, Khanna KK, Ludwig T, Pandita TK (2005) Involvement of human MOF in ATM function. Mol Cell Biol 25: 5292–5305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper JW, Elledge SJ (2007) The DNA damage response: ten years after. Mol Cell 28: 739–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huen MS, Grant R, Manke I, Minn K, Yu X, Yaffe MB, Chen J (2007) RNF8 transduces the DNA-damage signal via histone ubiquitylation and checkpoint protein assembly. Cell 131: 901–914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huyen Y, Zgheib O, Ditullio RA Jr, Gorgoulis VG, Zacharatos P, Petty TJ, Sheston EA, Mellert HS, Stavridi ES, Halazonetis TD (2004) Methylated lysine 79 of histone H3 targets 53BP1 to DNA double-strand breaks. Nature 432: 406–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikura T, Ogryzko VV, Grigoriev M, Groisman R, Wang J, Horikoshi M, Scully R, Qin J, Nakatani Y (2000) Involvement of the TIP60 histone acetylase complex in DNA repair and apoptosis. Cell 102: 463–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SP (2002) Sensing and repairing DNA double-strand breaks. Carcinogenesis 23: 687–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinner A, Wu W, Staudt C, Iliakis G (2008) Gamma-H2AX in recognition and signaling of DNA double-strand breaks in the context of chromatin. Nucleic Acids Res 36: 5678–5694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolas NK, Chapman JR, Nakada S, Ylanko J, Chahwan R, Sweeney FD, Panier S, Mendez M, Wildenhain J, Thomson TM, Pelletier L, Jackson SP, Durocher D (2007) Orchestration of the DNA-damage response by the RNF8 ubiquitin ligase. Science 318: 1637–1640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo MH, Brownell JE, Sobel RE, Ranalli TA, Cook RG, Edmondson DG, Roth SY, Allis CD (1996) Transcription-linked acetylation by Gcn5p of histones H3 and H4 at specific lysines. Nature 383: 269–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon J, Morshead KB, Guyon JR, Kingston RE, Oettinger MA (2000) Histone acetylation and hSWI/SNF remodeling act in concert to stimulate V(D)J cleavage of nucleosomal DNA. Mol Cell 6: 1037–1048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mailand N, Bekker-Jensen S, Faustrup H, Melander F, Bartek J, Lukas C, Lukas J (2007) RNF8 ubiquitylates histones at DNA double-strand breaks and promotes assembly of repair proteins. Cell 131: 887–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manke IA, Lowery DM, Nguyen A, Yaffe MB (2003) BRCT repeats as phosphopeptide-binding modules involved in protein targeting. Science 302: 636–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison AJ, Highland J, Krogan NJ, Arbel-Eden A, Greenblatt JF, Haber JE, Shen X (2004) INO80 and γ-H2AX interaction links ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling to DNA damage repair. Cell 119: 767–775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mujtaba S, Zeng L, Zhou MM (2007) Structure and acetyl-lysine recognition of the bromodomain. Oncogene 26: 5521–5527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murr R, Loizou JI, Yang YG, Cuenin C, Li H, Wang ZQ, Herceg Z (2006) Histone acetylation by Trrap-Tip60 modulates loading of repair proteins and repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Nat Cell Biol 8: 91–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papamichos-Chronakis M, Krebs JE, Peterson CL (2006) Interplay between Ino80 and Swr1 chromatin remodeling enzymes regulates cell cycle checkpoint adaptation in response to DNA damage. Genes Dev 20: 2437–2449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park EJ, Chan DW, Park JH, Oettinger MA, Kwon J (2003) DNA-PK is activated by nucleosomes and phosphorylates H2AX within the nucleosomes in an acetylation-dependent manner. Nucleic Acids Res 31: 6819–6827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JH, Park EJ, Hur SK, Kim S, Kwon J (2009) Mammalian SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complexes are required to prevent apoptosis after DNA damage. DNA Repair 8: 29–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JH, Park EJ, Lee HS, Kim SJ, Hur SK, Imbalzano AN, Kwon J (2006) Mammalian SWI/SNF complexes facilitate DNA double-strand break repair by promoting gamma-H2AX induction. EMBO J 25: 3986–3997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson CL, Cote J (2004) Cellular machineries for chromosomal DNA repair. Genes Dev 18: 602–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin S, Parthun MR (2002) Histone H3 and the histone acetyltransferase Hat1p contribute to DNA double-strand break repair. Mol Cell Biol 22: 8353–8365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin S, Parthun MR (2006) Recruitment of the type B histone acetyltransferase Hat1p to chromatin is linked to DNA double-strand breaks. Mol Cell Biol 26: 3649–3658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders SL, Portoso M, Mata J, Bähler J, Allshire RC, Kouzarides T (2004) Methylation of histone H4 lysine 20 controls recruitment of Crb2 to sites of DNA damage. Cell 119: 603–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W, Xu C, Huang W, Zhang J, Carlson JE, Tu X, Wu J, Shi Y (2007) Solution structure of human Brg1 bromodomain and its specific binding to acetylated histone tails. Biochemistry 46: 2100–2110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim EY, Ma JL, Oum JH, Yanez Y, Lee SE (2005) The yeast chromatin remodeler RSC complex facilitates end joining repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Mol Cell Biol 25: 3934–3944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squatrito M, Gorrini C, Amati B (2006) Tip60 in DNA damage response and growth control: many tricks in one HAT. Trends Cell Biol 16: 433–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart GS, Panier S, Townsend K, Al-Hakim AK, Kolas NK, Miller ES, Nakada S, Ylanko J, Olivarius S, Mendez M, Oldreive C, Wildenhain J, Tagliaferro A, Pelletier L, Taubenheim N, Durandy A, Byrd PJ, Stankovic T, Taylor AM, Durocher D (2009) The RIDDLE syndrome protein mediates a ubiquitin-dependent signaling cascade at sites of DNA damage. Cell 136: 420–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strahl BD, Allis CD (2000) The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature 403: 41–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taipale M, Rea S, Richter K, Vilar A, Lichter P, Imhof A, Akhtar A. (2005) hMOF histone acetyltransferase is required for histone H4 lysine 16 acetylation in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol 25: 6798–6810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamburini BA, Tyler JK (2005) Localized histone acetylation and deacetylation triggered by the homologous recombination pathway of double-strand DNA repair. Mol Cell Biol 25: 4903–4913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjeertes JV, Miller KM, Jackson SP (2009) Screen for DNA-damage-responsive histone modifications identifies H3K9Ac and H3K56Ac in human cells. EMBO J 28: 1878–1889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner BM (2005) Reading signals on the nucleosome with a new nomenclature for modified histones. Nat Struct Mol Biol 12: 110–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Chini CC, He M, Mer G, Chen J (2003) The BRCT domain is a phospho-protein binding domain. Science 302: 639–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Attikum H, Fritsch O, Gasser SM (2007) Distinct roles for SWR1 and INO80 chromatin remodeling complexes at chromosomal double-strand breaks. EMBO J 26: 4113–4125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Attikum H, Fritsch O, Hohn B, Gasser SM (2004) Recruitment of the INO80 complex by H2A phosphorylation links ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling with DNA double-strand break repair. Cell 119: 777–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Attikum H, Gasser SM (2009) Crosstalk between histone modifications during the DNA damage response. Trends Cell Biol 19: 207–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gent DC, Hoeijmakers JH, Kanaar R (2001) Chromosomal stability and the DNA double-stranded break connection. Nat Rev Genet 2: 196–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Matsuoka S, Ballif BA, Zhang D, Smogorzewska A, Gygi SP, Elledge SJ (2007) Abraxas and RAP80 form a BRCA1 protein complex required for the DNA damage response. Science 316: 1194–1198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.