Sialic acids, a family of monosaccharides widely distributed in higher eukaryotes and certain bacteria, are determinants of many functional glycans that play central roles in numerous physiological and pathological processes.[1] For example, the sialic acid-containing epitope Siaα2–6Gal serves as the cellular receptor for human influenza-A and -B viruses during infection,[2] and linear homopolymers of sialic acids, known as polysialic acid (PSA), modulate neuronal synapse formation in mammalian development.[3] The expression of sialoglycoconjugates, such as sialyl Lewis x, sialyl Tn (STn), and PSA, is also a common feature shared by numerous cancers.[4] Interestingly, upregulation of these sialosides is strongly correlated with the transformed phenotype of many cancers.[5, 6] For example, STn, a mucin-associated disaccharide, is not normally found in healthy tissues but is expressed by malignant tumors, including those of the pancreas and breast.[7, 8] In addition, a strong correlation between the level of cell surface sialic acids and metastatic potential has been observed in several different tumor types.[9] Thus, as cancer cells generally display higher levels of sialic acid than their nonmalignant counterparts, sialylated glycoconjugates, collectively termed the “sialome”, constitute attractive targets in the search for novel cancer biomarkers.

A variety of methods has been reported for the enrichment and identification of sialylated glycoproteins from bodily fluids or cell lysates. For example, affinity chromatography using sialic acid-specific lectins[10–12] or selective periodate oxidation of sialic acids followed by hydrazide capture[13] can provide glycoprotein samples that are enriched for sialylated species. These methods have been used for comparative analysis of the steady-state abundances of sialylated glycoproteins in serum from cancer patients and healthy subjects.[1]

A complementary method that we have developed involves metabolic labeling of sialylated glycoproteins by treating cells or living animals with peracetylated analogs of N-acetylmannosamine (ManNAc) bearing chemical reporter groups such as the azide (i.e., peracetylated N-azidoacetylmannosamine, Ac4ManNAz).[15, 16] Ac4ManNAz is enzymatically deacetylated in the cytosol and then metabolically converted to the corresponding N-azidoacetyl sialic acid (SiaNAz), which is subsequently incorporated into sialoglycoconjugates.[15, 17] Once presented on the cell surface, the azide-labeled sialylated glycans can be visualized or captured for glycoproteomic analysis with a variety of reagents[18], including Staudinger ligation phosphines[15], terminal alkynes along with reagents for Cu(I)-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC)[19, 20], or strained alkynes.[21] Wong and coworkers reversed the polarity of the reagents, using an alkynyl ManNAc derivative for metabolic labeling of cultured cells and CuAAC-mediated reaction with an azide-functionalized probe for capture of sialylated glycoproteins.[22, 23]

The metabolic/chemical labeling method holds several advantages over previous approaches to sialylated glycoprotein analysis. First, metabolic labeling selects for those glycoproteins that are biosynthesized at high levels, irrespective of their steady-state abundance. Thus, metabolic labeling may reveal novel sialylated biomarkers that are turned over rapidly and therefore missed by steady-state labeling methods. Second, metabolic labeling can be performed in live animals[16], permitting the selective tagging of sialylated glycoconjugates within their native tissue environments. However, the efficiency of sialic acid labeling using Ac4ManNAz is fairly low in vivo. Mouse heart tissue glycoproteins incorporate SiaNAz at ~3% of total sialic acid, and the azidosugar is undetectable in some organs that are known to possess sialylated glycoconjugates.[16]

The efficiency of sialic acid biosynthesis is very sensitive to the N-acyl structure of unnatural ManNAc analogs.[25, 26] Analogs with long or branched N-acyl chains are poor substrates for the biosynthetic enzymes, while those containing short, linear side chains are better tolerated.[26] Thus, we were curious how the alkynyl ManNAc analog reported by Wong and coworkers[23] would fare in live animal metabolic labeling studies compared to ManNAz. Toward this goal, we synthesized peracetylated N-(4-pentynoyl) mannosamine (Ac4ManNAl, Figure 1) and confirmed its metabolic conversion to the corresponding sialic acid (SiaNAl) in cultured cells. Jurkat cells, a human T lymphoma cell line, were cultured with 50 μM Ac4ManNAl for three days, after which their lysates were reacted with an azido biotin derivative (biotin-azide, Figure 1)[27] using standard CuAAC conditions.[28] Western blot analysis showed significant glycoprotein labeling in lysates from cells treated with Ac4ManNAl but no detectable labeling in lysates from untreated cells (Figure 2).

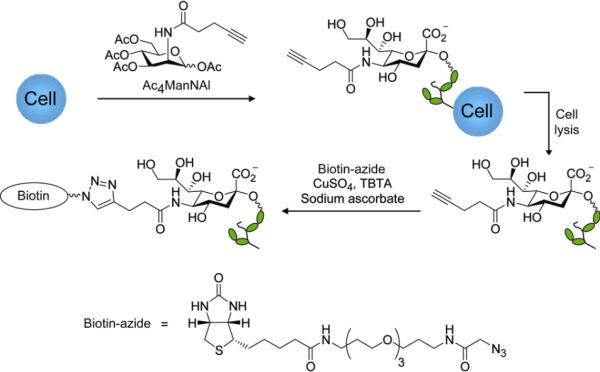

Figure 1.

Schematic for metabolic labeling of cellular glycans with Ac4ManNAl and detection with Cu(I)-catalyzed click chemistry.

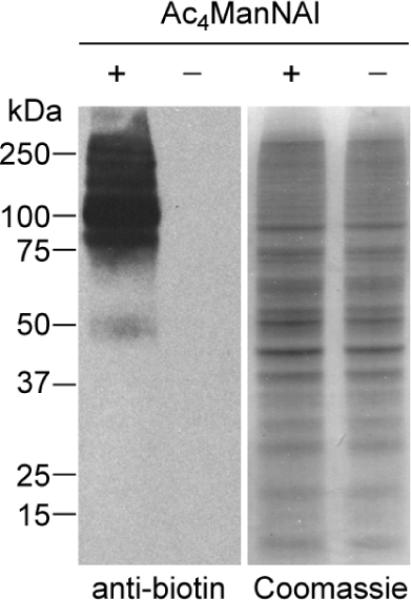

Figure 2.

Western blot analysis of lysates from Jurkat cells treated with Ac4ManNAl (50 μM) or no sugar. The lysates were reacted with biotinazide (100 μM) in the presence CuSO4 (1 mM), sodium ascorbate (1 mM), and the tris-triazolyl ligand TBTA[14] (100 μM) for 1 h at rt and analyzed by Western blot using an HRP-conjugated anti-biotin antibody (left panel). Total protein loading was confirmed by Coomassie staining of a duplicate protein gel (right panel).

We confirmed the presence of SiaNAl within these cellular glycans by performing sialic acid compositional analysis using established protocols (see Supporting Information for description of methods).[24] As shown in Table 1, we compared the efficiencies of metabolic conversion of Ac4ManNAl and Ac4ManNAz to glycoconjugate-bound SiaNAl and SiaNAz, respectively. Six cell lines were cultured in media supplemented with 50 μM Ac4ManNAl or Ac4ManNAz. After 72 hours, cells were lysed and the lysates subjected to sialic acid quantification. In every cell line, metabolic labeling with SiaNAl was substantially more efficient than with SiaNAz. For example, in the human prostate cancer cell line LNCaP, 78% of glycoconjugate-bound sialic acids were substituted with SiaNAl. By contrast, SiaNAz constituted only 51% of LNCaP glycan-associated sialic acids under the same metabolic labeling conditions. Fluorescence microscopy analysis of Ac4ManNAl- labeled cells after reaction with biotin-azide via CuAAC and staining with FITC-streptavidin confirmed that SiaNAl-modified glycans reside on the cell surface (see Supporting Information).

Table 1.

Incorporation percentage of SiaNAl vs. SiaNAz in vitro.[a]

| Cell line | Jurkat | HEK 293T | CHO | LNCaP | DU145 | PC3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % SiaNAl | 74±1 | 46±2 | 38±2 | 78±1 | 58±2 | 71±6 |

| % SiaNAz | 29±2 | 27±2 | 20±4 | 51±2 | 40±3 | 56±2 |

The cells were metabolically labeled with 50 μM Ac4ManNAl (top row) or Ac4ManNAz (bottom row) for 3 d and then lysed. Identification and quantification of SiaNAl and SiaNAz was determined by comparison with synthetic standards according to established procedures.[24] The error represents the standard deviation from the mean of at least three replicate experiments.

To determine whether the superior metabolic conversion efficiency of Ac4ManNAl observed in cell culture is recapitulated in vivo, we evaluated its conversion to SiaNAl after administration to laboratory mice. B6D2F1/J mice were injected intraperitoneally with Ac4ManNAl (300 mg/kg) or vehicle once daily for seven days (Figure 3). On the eighth day, the mice were euthanized, and a panel of organs was harvested and homogenized. The presence of glycoprotein-associated alkynes in the soluble fraction of homogenates was probed by CuAAC with biotin-azide, followed by Western blot analysis. As shown in Figure 4, labeling was observed in organ lysates from mice treated with Ac4ManNAl but not in organ lysates from vehicle-treated mice. Labeled glycoproteins were observed in lysates from the bone marrow, thymus, intestines, lung, spleen, heart, and liver, but not the kidney. These results indicated that Ac4ManNAl is metabolized in vivo and has access to most organs. Furthermore, during this one-week period, no toxic side effects were observed, suggesting that Ac4ManNAl is well tolerated by the mice.

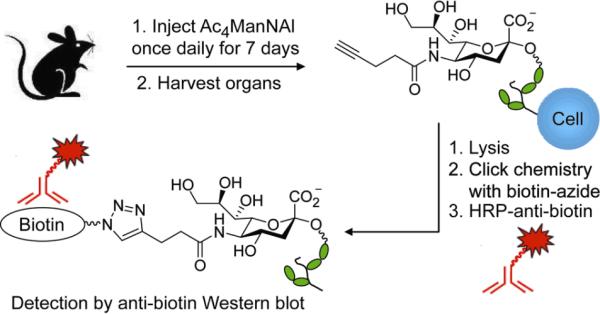

Figure 3.

Experimental overview for probing Ac4ManNAl metabolism in vivo. Wild-type B6D2F1/J mice were injected with Ac4ManNAl or vehicle intraperitoneally once daily for seven days. On the eighth day, the organs were collected and homogenized, and organ lysates were probed using click chemistry for the presence of alkyne-bearing glycoproteins by reaction with biotin-azide, followed by Western blot analysis using an HRP-conjugated anti-biotin antibody.

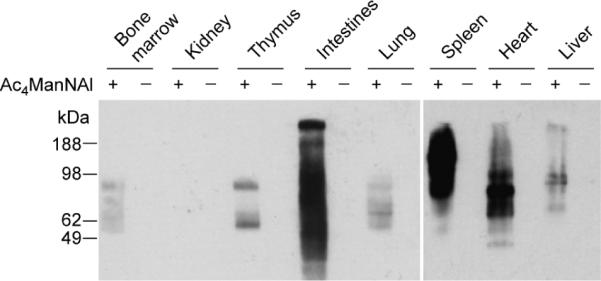

Figure 4.

Western blot analysis of tissue lysates from B6D2F1/J mice administered Ac4ManNAl (+) or vehicle (−). Mice were injected with Ac4ManNAl (300 mg/kg) or vehicle once daily for seven days. On the eighth day, the organs were harvested and homogenized. The lysates were then reacted with biotin-azide (100 μM) in the presence CuSO4 (1 mM), sodium ascorbate (1 mM), and TBTA (100 μM) for 1 h at rt and analyzed by Western blot using an HRP-conjugated anti-biotin antibody. Shown are representative data from three replicate experiments. Total protein loading was confirmed by Coomassie Blue staining of a duplicate protein gel (data not shown).

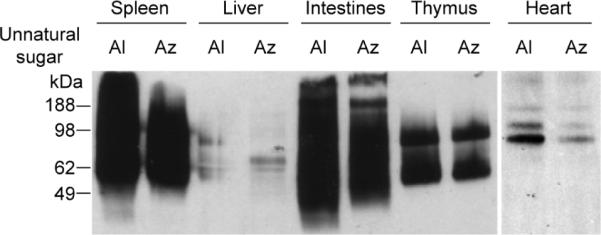

We then performed comparative in vivo metabolism studies of Ac4ManNAl and Ac4ManNAz using a similar protocol. The organs were harvested as described above, and the soluble fractions of the organ lysates were reacted with either biotin-azide or a biotin-alkyne derivative[21] using the same CuAAC conditions. Similar to our observations using cultured cells (Table 1), Ac4ManNAl treatment produced stronger labeling in organ lysates than Ac4ManNAz (Figure 5). Based on quantification by densitometry, we estimate that the labeling using ManNAl is at least 25% greater than that using ManNAz (see Supporting Information). However, estimating metabolic incorporation based on these data is difficult because CuAAC displays different reaction kinetics when the limiting reagent is the alkyne compared to the azide.[28] Given that the reaction kinetics are faster by approximately 2–3 fold in the latter case, we believe our estimate based on densitometry to be a lower limit.

Figure 5.

Ac4ManNAl is converted to the corresponding sialic acid more efficiently than Ac4ManNAz in mouse organs. A panel of organ lysates from mice treated with Ac4ManNAl (Al) or Ac4ManNAz (Az) (300 mg/kg) for 7 d were reacted with 100 μM biotin-azide or biotin-alkyne[21], respectively, in the presence CuSO4 (1 mM), sodium ascorbate (1 mM), and TBTA (100 μM) for 1 h at rt and analyzed by Western blot using an HRP-conjugated anti-biotin antibody. Shown are representative data from three replicate experiments. Total protein loading was confirmed by Coomassie Blue staining of a duplicate protein gel (data not shown).

In summary, we have demonstrated that Ac4ManNAl can metabolically label sialic acids in cultured cells and mice with greater efficiency than Ac4ManNAz. The alkynyl sugar may therefore be useful in the discovery of sialylated cancer biomarkers using murine cancer models. Moreover, these results underscore the sensitivity of sialic acid biosynthetic enzymes to subtle differences in the N-acyl structures of the two ManNAc analogs. Accordingly, further structural modulation of alkynyl and azido ManNAc analogs is worth pursuing in order to further increase metabolic labeling efficiency in vivo.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Director, Office of Energy Research, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Division of Materials Sciences, of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC03-76SF00098 (C.R.B.), as well as a grant from the National Institutes of Health to P.W. (K99GM080585) and startup funds from Albert Einstein College of Medicine (P.W.). P.V.C. was supported by predoctoral fellowships from the National Science Foundation and the American Chemical Society Division of Medicinal Chemistry. We thank the Glycotechnology Core Resource at UC San Diego for sialic acid analysis. We also thank J. Baskin for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.

References

- [1].Varki A, Cummings R, Esko J, Freeze H, Stanley P, Bertozzi C, Hart G, Etzler M. Essentials of Glycobiology. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; New York: 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Olofsson S, Bergstrom T. Ann. Med. 2005;37:154–172. doi: 10.1080/07853890510007340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Troy FA., 2nd Glycobiology. 1992;2:5–23. doi: 10.1093/glycob/2.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Taylor-Papadimitriou J, Epenetos AA. Trends Biotechnol. 1994;12:227–233. doi: 10.1016/0167-7799(94)90121-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sell S. Human Pathol. 1990;21:1003–1019. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(90)90250-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Jorgensen T, Berner A, Kaalhus O, Tveter KJ, Danielsen HE, Bryne M. Cancer Res. 1995;55:1817–1819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Itzkowitz S, Kjeldsen T, Friera A, Hakomori S, Yang US, Kim YS. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:1691–1700. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90671-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ogata S, Koganty R, Reddish M, Longenecker BM, Chen A, Perez C, Itzkowitz SH. Glycoconj. J. 1998;15:29–35. doi: 10.1023/a:1006935331756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Dube DH, Bertozzi CR. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2005;4:477–488. doi: 10.1038/nrd1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zhao J, Simeone DM, Heidt D, Anderson MA, Lubman DM. J. Proteome Res. 2006;5:1792–1802. doi: 10.1021/pr060034r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Qui R, Regnier FE. Anal. Chem. 2005;77:7225–7231. doi: 10.1021/ac050554q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Qui R, Regnier FE. Anal. Chem. 2005;77:2802–2809. doi: 10.1021/ac048751x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].McDonald CA, Yang JY, Marathe V, Yen TY, Macher BA. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2008 doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800272-MCP200. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Chan TR, Hilgraf R, Sharpless KB, Fokin VV. Org. Lett. 2004;6:2853–2855. doi: 10.1021/ol0493094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Saxon E, Bertozzi CR. Science. 2000;287:2007–2010. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5460.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Prescher JA, Dube DH, Bertozzi CR. Nature. 2004;430:873–877. doi: 10.1038/nature02791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Luchansky SJ, Hang HC, Saxon E, Grunwell JR, Yu C, Dube DH, Bertozzi CR. Methods Enzymol. 2003;362:249–272. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)01018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Laughlin ST, Bertozzi CR. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:2930–2944. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Rostovtsev VV, Green LG, Fokin VV, Sharpless KB. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:2596–2599. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020715)41:14<2596::AID-ANIE2596>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Tornoe CW, Christensen C, Meldal M. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:3057–3064. doi: 10.1021/jo011148j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Agard NJ, Prescher JA, Bertozzi CR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:15046–15047. doi: 10.1021/ja044996f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Hanson SR, Hsu TL, Weerapana E, Kishikawa K, Simon GM, Cravatt BF, Wong CH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:7266–7267. doi: 10.1021/ja0724083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Hsu TL, Hanson SR, Kishikawa K, Wang SK, Sawa M, Wong CH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:2614–2619. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611307104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Luchansky SJ, Argade S, Hayes BK, Bertozzi CR. Biochemistry. 2004;43:12358–12366. doi: 10.1021/bi049274f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Keppler OT, Horstkorte R, Pawlita M, Schmidt C, Reutter W. Glycobiology. 2001;11:11R–18R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/11.2.11r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Jacobs CL, Goon S, Yarema KJ, Hinderlich S, Hang HC, Chai DH, Bertozzi CR. Biochemistry. 2001;40:12864–12874. doi: 10.1021/bi010862s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hang HC, Yu C, Pratt MR, Bertozzi CR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:6–7. doi: 10.1021/ja037692m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Speers AE, Cravatt BF. Chem. Biol. 2004;11:535–546. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.