Abstract

A new 5-coordinate, (N4S(thiolate))FeII complex, containing tertiary amine donors, [FeII(Me4[15]aneN4)(SPh)]BPh4 (2), was synthesized and structurally characterized as a model of the reduced active site of superoxide reductase (SOR). Reaction of 2 with tert-butyl hydroperoxide (tBuOOH) at -78 °C led to the generation of the alkylperoxo-iron(III) complex [FeIII(Me4[15]aneN4)(SPh)(OOtBu)]+ (2a). The non-thiolate-ligated complex, [FeII(Me4[15]aneN4)-(OTf)2] (3), was also reacted with tBuOOH, and yielded the corresponding alkylperoxo complex [FeIII(Me4[15]aneN4)(OTf)(OOtBu)]+ (3a) at the elevated temperature of -23 °C. These species were characterized by low-temperature UV-vis, EPR, and resonance Raman spectroscopies. Complexes 2a and 3a exhibit distinctly different spectroscopic signatures than the analogous alkylperoxo complexes [FeIII([15]aneN4)(SAr)(OOR)]+, which contain secondary amine donors. Importantly, alkylation at nitrogen leads to a change from low-spin (S = ½) to high -spin (S = 5/2) of the iron(III) center. The resonance Raman data reveal that this change in spin-state has a large effect on the ν(Fe-O) and ν(O-O) vibrations, and a comparison between 2a and the non-thiolate-ligated complex 3a shows that axial ligation has an additional significant impact on these vibrations. In addition, to our knowledge this study is the first in which the influence of a ligand trans to a peroxo moiety has been evaluated for a structurally equivalent pair of high-spin/low-spin peroxo-iron(III) complexes. The implications of spin state and thiolate ligation are discussed with regard to the functioning of SOR.

Introduction

The processing of dioxygen and related molecules, such as hydrogen peroxide and superoxide, is of critical importance to a number of heme and non-heme iron metalloproteins. In most of these systems the formation of iron-oxygen adducts in the form of iron-superoxo, -hydroperoxo, or -alkylperoxo species is a key step in their function. One such metalloprotein is superoxide reductase (SOR), which is found in anaerobic and microaerophilic organisms and reduces superoxide to hydrogen peroxide as part of the organism's natural defenses.1-10 The reduced, active state of SOR contains an FeII center bound by four imidazolyl nitrogen donors from histidine arranged in a plane, and a thiolato sulfur donor from cysteine in an axial position, resulting in a square pyramidal [(N4S(thiolate)] geometry around the iron center. The coordination environment of SOR has an obvious structural similarity with the heme-iron active site of cytochrome P450, in which the iron center is coordinated by four pyrrolyl nitrogen donors in the equatorial plane and a cysteinate ligand in the axial position.11-14 The two enzymes are thought to access similar iron-(hydro)peroxy intermediates during catalysis, which then experience dramatically different fates; in the case of SOR the (hydro)peroxy ligand is released as H2O2, whereas in P450 O-O bond cleavage takes place and results in the formation of a reactive, high-valent iron-oxo species.

One possible factor that influences the fate of the iron(III)-(hydro)peroxo intermediate is the spin state of the iron center. Solomon and Que have performed spectroscopic studies, supported by theoretical calculations, on both hydroperoxo- and alkylperoxo-iron(III) model complexes that show that a low-spin FeIII (S = ½) gives rise to relatively strong Fe-O and weak O-O bonds, while high-spin FeIII (S = 5/2) produces weak Fe-O and strong O-O bonds.15,16 These studies have led to the hypothesis that a low-spin state in the FeIII-OO(H) intermediate in P450 favors O-O bond cleavage, while an analogous high-spin intermediate in SOR would favor release of H2O2.17-21 The spin state of the putative FeIII-OO(H) intermediate formed in the native reaction of O2- with SOR is not known, although there is some evidence to suggest that the FeIII-OO(H) species formed upon reaction of SOR with H2O2 is high-spin.8,22-24 Recent density functional theory (DFT) calculations show that the most energetically favorable reaction pathway for SOR is via a high-spin FeIII-OOH species.3

In addition to spin state, the presence of the cysteine thiolate ligand in SOR may help tune the strength of the Fe-O bond such that Fe-O over O-O bond cleavage occurs preferentially. In a previous study we provided evidence for this idea via the spectroscopic characterization of a series of thiolate-ligated iron model complexes.25 However, it should be noted that a cysteine thiolate is also present in P450, and it has been suggested for many years that the thiolate ligand in P450 promotes O-O bond cleavage via the “push effect.”

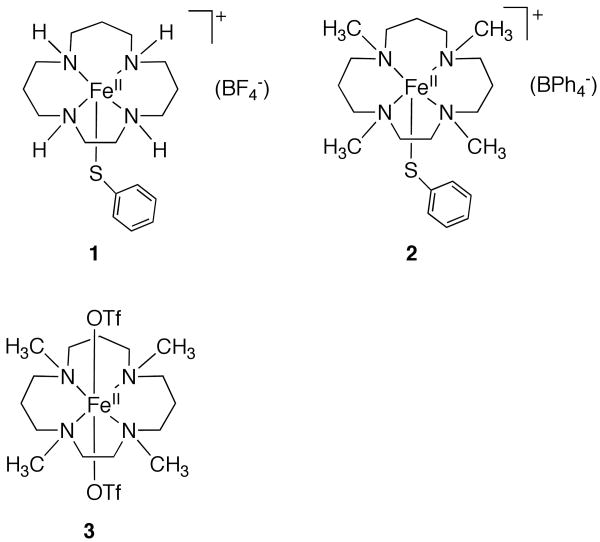

The synthesis and characterization of small-molecule model complexes has been critical for gaining an understanding of the spectroscopic and reactivity properties of enzymatic iron-peroxo species. However, there are very few non-heme iron model complexes that mimic the unusual mixed nitrogen/sulfur ligation of SOR, especially with regard to including a thiolate donor in the coordination sphere.5,26-29 The lack of such models is in part due to the difficulties inherent in synthesizing complexes with thiolate ligands, which are prone to oxidation as well as forming bridged, polymetallic species. Toward this end we recently synthesized a series of N4S(thiolate)FeII complexes with the general formula [FeII([15]aneN4)(SAr-p-X)]BF4 ([15]aneN4 = 1,4,8,12-tetraazacyclopentadecane, X = H (1), Cl, OMe, NO2 and SAr = SC6F4-p-C6F5) as models for the reduced form of SOR (for the structure of 1, see Chart 1), in which the electron-donating ability of the thiolate donor was systematically varied.25

Chart 1.

These complexes react with alkylhydroperoxides to give metastable, low-spin FeIII-OOR species that can be trapped and spectroscopically characterized at low temperature. Resonance Raman (RR) studies on these complexes showed a clear correlation between an increase in the electron-donating ability of the thiolate ligand and a reduction in the Fe-O stretching frequency. This trend matches nicely with the limited data available for the influence of the Cys donor on the Fe-O stretch in the enzyme.6,23

In the present study we have turned our attention to the influence of the macrocyclic amine nitrogen donors in these model complexes. We hypothesized that alkylation of the nitrogen donors should be a straightforward way of modulating their electronic and steric properties while still allowing us to isolate the same type of coordinatively unsaturated N4S(thiolate)FeII model complexes. The alkylation of secondary amine donors in other macrocyclic metal complexes has been shown to influence their redox potentials, LMCT bands, spin state, and reactivity.30-32 Although alkylation of the N donors in [15]aneN4 might be expected to make this ligand a stronger-field ligand, previous studies suggested that alkylation should in fact make it a weaker donor, and perhaps allow us access to high-spin FeIII-OO(R or H) species. Only two other high-spin thiolate-ligated FeIII-OO(R or H) species have been reported. Kovacs and Solomon33 described the preparation of high-spin [FeIII(cyclam-PrS)(OOH)]+, and Que and Halfen20 reported the high-spin FeIII-OOR complex [FeIII(L8py2)(CH3-p-C6H4S)(OOtBu)]+ (L8py2 = neutral N4 donor).

Herein we describe the synthesis of the new iron(II) complex [FeII(Me4[15]aneN4)(SPh)]BPh4 (2) (Me4[15]aneN4 = 1,4,8,12-tetramethyl-1,4,8,12-tetraazacyclopentadecane), which is the tetra-N-methylated analogue of [FeII([15]aneN4)(SPh)]BF4 (1) reported previously (Chart 1).25,34 Reaction of 2 with tBuOOH results in the formation of a novel, metastable FeIII-OOR species that can be trapped at low temperature. Alkylation of the nitrogen donors in the basal plane of this SOR model complex is found to have a profound influence on the spectroscopic (UV-vis, EPR, RR) properties of the alkylperoxo species. In addition, the non-thiolate-ligated complex, FeII(Me4[15]aneN4)(OTf)2 (3) (Chart 1), has been examined and shown to react with ROOH to give a metastable low-temperature FeIII-OOR adduct absent the thiolate donor. Comparison of this species with the thiolate-ligated complex has provided a means to assess the role of the thiolate donor in addition to alkylation at nitrogen.

Experimental Section

General Procedures

All reactions were carried out under an atmosphere of N2 or Ar using a drybox or standard Schlenk techniques. 1,4,8,12-tetraazocyclopentadecane ([15]aneN4) (98%) was purchased from Strem Chemicals. Ferrous triflate was purchased from Wako Chemicals. All other reagents were purchased from commercial vendors and used without further purification unless noted otherwise. Diethyl ether and dichloromethane were purified via a Pure-Solv Solvent Purification System from Innovative Technology, Inc. THF was distilled from sodium/benzophenone. Acetonitrile was distilled from CaH2. All solvents were degassed by repeated cycles of freeze-pump-thaw and then stored in a dry box. Sodium hydride (60% in mineral oil) was washed with hexanes prior to use. Tert-butylhydroperoxide was purchased from Aldrich as an ∼ 5.5 M solution in decane over molecular sieves. Isotopically labeled tBuO18O18H was synthesized by the reaction of tBuMgCl with 18O2 following a published procedure.35 The 18O2 gas was purchased from Icon Isotopes (99% atom purity).

Physical Methods

Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra were obtained on a Bruker EMX EPR spectrometer controlled with a Bruker ER 041 × G microwave bridge at 15 K. The EPR spectrometer was equipped with a continuous-flow liquid He cryostat and an ITC503 temperature controller made by Oxford Instruments, Inc. Low-temperature UV-visible spectra were recorded at −78 °C on a Cary 50 Bio spectrophotometer equipped with a fiber-optic coupler (Varian) and a fiber optic dip probe (Hellma 661.302-QX-UV, 2 mm path length) for low temperature, using custom-made Schlenk tubes designed for the fiber-optic dip probe. RR spectra were obtained on a custom McPherson 2061/207 spectrometer equipped with a Princeton Instrument liquid-N2 cooled CCD detector (LN-1100PB). The 647-nm and 514-nm excitations were obtained from a Kr laser (Innova 302, Coherent) and an Ar laser (Innova 90, Coherent), respectively. The laser beam was kept at low power (between 30 mW and 80 mW) and focused with a cylindrical lens on frozen samples in NMR tubes. The samples were subjected to continuous spinning at 110 K to prevent adverse effects from the laser illumination. Long wave pass filters (RazorEdge filters, Semrock) were used to attenuate the Rayleigh scattering. Sets of ∼15 min accumulations were acquired at 4-cm-1 resolution. Frequency calibrations were performed using aspirin and are accurate to ±1 cm-1. Elemental analyses were performed by Atlantic Microlab Inc., Norcross, GA. 1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker AMX-400 spectrometer (400 MHz).

Synthesis of 1,4,8,12-tetramethyl-1,4,8,12-tetraazocyclopentadecane (Me4[15]aneN4)

The ligand Me4[15]aneN4 was synthesized from the reaction of [15]aneN4 with formaldehyde following a procedure reported by Che et al.31 A mixture of [15]aneN4 (2.0 g, 9.3 mmol), formic acid (9.8 mL, 98-100%), formaldehyde (8.9 mL, 37%), and water (1 mL) was refluxed for 48 h, and then cooled to room temperature. The reaction mixture was slowly transferred to an 800 mL beaker containing 50 mL of H2O immersed in an ice bath. A solution of sodium hydroxide (8 M) was gradually added to the mixture until a pH > 12 was reached. The solution was extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 250 mL). The organic fractions were dried with anhydrous sodium sulfate and the solvent was evaporated to obtain an oily yellow residue. The oily residue was distilled under reduced pressure (0.1 mm Hg) with heating up to 110 – 120 °C to remove impurities. The pure product remained in the distillation flask as an oil under these conditions. Yield: 2.14 g (85%) of Me4[15]aneN4; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 1.5, m (CH2, 6H); 2.2, d (CH3, 12H); 2.3-2.5, m (CH2, 16H).

Synthesis of [FeII(Me4[15]aneN4)(SC6H5)](BPh4) (2)

A solution of Me4[15]aneN4 (0.135 g, 0.498 mmol) in CH3CN (3 mL) was added dropwise to a suspension of anhydrous FeCl2 (0.053 g, 0.421 mmol) in CH3CN (3 mL), and stirred for 45 minutes resulting in a pale yellow-brown solution. An acetonitrile solution of NaSC6H5 (0.089 g, 0.676 mmol) (prepared from addition of benzenethiol to NaH in THF) was added to the mixture dropwise and stirred for an hour to give a brown solution with white precipitate. An acetonitrile solution of NaBPh4 (0.157 g, 0.460 mmol) was added to the mixture dropwise, resulting in more white precipitate, and the solution was stirred over night. The solvent was removed under vacuum to give an off-white solid, which was redissolved in CH2Cl2 and filtered through celite to give a brown solution. Vapor diffusion of diethyl ether into this solution resulted in colorless plates of 2 after a few hours. Yield: 0.260 g (78%); Anal. Calc. for C45.5H60N4BClFeS (2 • 0.5 CH2Cl2) C, 68.55; H, 7.59; N, 7.03. Found: C, 68.54; H, 7.74; N, 6.97.

Synthesis of FeII(Me4[15]aneN4)(OTf)2 (3)

The synthesis of 3 was reported previously,36 and this method was followed with slight modification. To a suspension of anhydrous Fe(OTf)2 (0.169 g, 0.477 mmol) in CH3CN (3 mL) was added a solution of Me4[15]aneN4 (0.155 g, 0.572 mmol) in CH3CN (3 mL) dropwise, and stirred for 5 h resulting in a gray-brown suspension. Acetonitrile was removed under vacuum to give a brown solid which was redissolved in CH2Cl2 and filtered through celite to give a clear solution. Vapor diffusion of diethyl ether into this solution resulted in crystals (colorless plates) of 3 within 24 h. Yield: 0.222 g (75%); Anal. Calc. for C17H34F6FeN4O6S2: C, 32.70; H, 5.49; N, 8.97. Found: C, 32.78; H, 5.49; N, 8.93. A unit cell check on representative crystals of 3 were performed by X-ray diffraction and compared with that reported previously,36 confirming the structure of 3.

X-ray Crystallography of 2

X-ray diffraction data were collected on an Oxford Diffraction Xcalibur3 diffractometer, equipped with a Mo K-alpha sealed-tube source and a Sapphire CCD detector. Single crystals were mounted in oil under a cold nitrogen stream at 110(2) K. Selected crystallographic details are provided in Table 1. Data were collected, integrated, scaled and corrected for absorption using CrysAlis PRO software.37 Structures were solved and refined using the SHELXTL suite of software.38

Table 1.

Crystallographic Information for Complex 2.

| Parameter | Parameter | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Formula | C93H124B2Cl6Fe2N8S2 | β (deg) | 106.1930(10) |

| Mr | 1764.14 | γ (deg) | 90 |

| cryst syst | monoclinic | V, Å3 | 8991.51(19) |

| Space group | P21/c | Z | 4 |

| a (Å) | 28.3020(4) | Cryst color | colorless |

| b (Å) | 18.3435(2) | T, K | 110 |

| c (Å) | 18.0349(2) | R1 [I > 2σ(I)] | 0.0610 |

| α (deg) | 90 | GOF on F2 | 1.046 |

Each unit cell contains two independent iron molecules and three methylene chloride solvent molecules, i.e 1.5 CH2Cl2 per FeII. The cationic portions of the two molecules are disordered across the pseudo-mirror plane of the Me4[15]aneN4 ligand such that a CH2CH2 group of the ligand in each cation exchanges positions with a CH2CH2CH2 group. There is also some disorder in one methylene chloride molecule.

Electrochemistry

Cyclic voltammetry was performed on an EG&G Princeton Applied Research potentiostat/galvanostat model 263A at scan rates of 0.025 – 0.5 V/s. A three-electrode configuration made up of a platinum working electrode, a Ag/AgCl reference electrode (3.5 M KCl), and a platinum wire auxiliary electrode was employed. Measurements were performed with 1.0 mM analyte in CH2Cl2 at ambient temperatures under argon using 0.10 M tetra-n-butylammonium hexafluorophosphate (recrystallized 3 times from ethanol/water, dried over high vacuum for 3 days and stored in the dry box) as the supporting electrolyte. The ferrocenium/ferrocene couple (FeCp2+/0) at 0.45 V was used as an external reference.

Generation of [FeIII(Me4[15]aneN4)(SPh)(OOtBu)]+ (2a) for UV-vis spectroscopy

In a typical reaction, a custom-made schlenk flask was loaded with 8 - 12 mg of [FeII(Me4[15]aneN4)(SPh)]BPh4 (2) and dissolved in 5 mL of CH2Cl2 to give a concentration between 1 - 3 mM for the FeII complex. A fiber optic dip probe UV-vis cell with a path length of 2 mm was inserted into the flask and the solution was cooled to -78 °C. After recording the UV-vis spectrum of the FeII starting material, 1.75 equiv. of tBuOOH (stock solution in n-decane) diluted in CH2Cl2 was added to the FeII complex. UV-vis spectra were recorded immediately following the addition of tBuOOH. An instant color change from colorless to turquoise green was observed, and the formation and decay of the turquoise species was monitored by UV-vis spectroscopy.

Generation of [FeIII(Me4[15]aneN4)(OTf)(OOtBu)]+ (3a) for UV-vis spectroscopy

In a typical reaction, a custom-made schlenk flask was loaded with FeII(Me4[15]aneN4)(OTf)2 (3) (11 mg, 0.0176 mmol), which was then dissolved in CH2Cl2 (5 mL, 3.5 mM in 3). A fiber optic dip probe UV-vis cell with a path length of 2 mm was inserted into the flask and the solution was cooled to -23 °C. After recording the UV-vis spectrum of the FeII starting material, 1.75 equiv. of tBuOOH (stock solution in n-decane) diluted in CH2Cl2 was added to the FeII complex. UV-vis spectra were recorded immediately following the addition of tBuOOH. A gradual color change from colorless to dark blue was observed and the formation and decay of the new species was monitored by UV-vis spectroscopy.

Generation of [FeIII(Me4[15]aneN4)(SPh)(OOtBu)]+ (2a) for resonance Raman spectroscopy

In a typical procedure, a Wilmad WG-5M economy NMR tube was loaded with a solution of 2 in CH2Cl2 (300 μL, 19 mM) and cooled to -78 °C. An amount of tBuOOH (1.75 equiv., stock solution in n-decane) diluted in CH2Cl2 was added to the NMR tube. The reaction mixture was shaken carefully to obtain a homogenous solution, and the rapid evolution of a turquoise color was noted, indicating the formation of 2a. The solution was then frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at 77 K until RR measurements were taken. Samples containing tBu18O18OH were prepared in an identical manner.

Generation of [FeIII(Me4[15]aneN4)(OTf)(OOtBu)]+ (3a) for resonance Raman spectroscopy

In a typical procedure, a Wilmad WG-5M economy NMR tube was loaded with a solution of 3 in CH2Cl2 (300 μL, 20 mM) and cooled to -23 °C. An amount of tBuOOH (1.75 equiv., stock solution in n-decane) diluted in CH2Cl2 was added to the NMR tube. The reaction mixture was shaken to obtain a homogenous solution, and the evolution of a dark blue color was observed, indicating the formation of 3a. The solution was then frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at 77 K until RR measurements were taken. Samples containing tBu18O18OH were prepared in an identical manner.

Generation of [FeIII(Me4[15]aneN4)(SPh)(OOtBu)]+ (2a) for EPR spectroscopy

In a typical procedure, a Wilmad Quartz EPR tube was loaded with a solution of 2 in CH2Cl2 (400 μL, 3 mM) and cooled to -78 °C. An amount of tBuOOH (1.75 equiv., stock solution in n-decane) diluted in CH2Cl2 was added to the NMR tube. The reaction mixture was bubbled briefly with Ar gas to obtain a homogenous solution, taking care so as to minimize warming of the solution. The rapid evolution of a turquoise color was noted, indicating the formation of 2a. The solution was then frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at 77 K until EPR measurements were taken.

Generation of [FeIII(Me4[15]aneN4)(OTf)(OOtBu)]+ (3a) for EPR spectroscopy

In a typical procedure, a Wilmad Quartz EPR tube was loaded with a solution of 3 in CH2Cl2 (400 μL, 5 mM) and cooled to -23 °C. An amount of tBuOOH (1.75 equiv., stock solution in n-decane) diluted in CH2Cl2 was added to the NMR tube. The reaction mixture was bubbled briefly with Ar gas to obtain a homogenous solution, taking care so as to minimize warming of the solution. The evolution of a dark blue color was noted, indicating the formation of 3a. The solution was then frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at 77 K until EPR measurements were taken.

Results and Discussion

Selection of the Tetramethylated Ligand Me4[15]aneN4

Our previous work on models of the active site of SOR employed the 15-membered macrocycle [15]aneN4. This macrocyclic, tetradentate nitrogen donor was selected because it provided the appropriate number of neutral N donors to mimic the four His donors in SOR, it was commercially available, and like other macrocyclic ligands, was known to give very stable complexes. Although there were no structurally characterized iron(III) complexes of [15]aneN4, a variety of other trivalent complexes of other metals (CoIII, RhIII, CrIII) had been described previously.39-42 These trivalent complexes all contain trans-ligated axial ligands (trans-([15]aneN4)MIII(L)2), despite the potential flexibility of macrocycles of this type to fold into a cis-ligated structure, and this propensity for forming trans structures was desirable from the standpoint of preparing trans-ligated iron(III) thiolate/peroxo species. In this study we employed the tetramethylated analog of Me4[15]aneN4, which was expected to offer the same advantages as outlined above for [15]aneN4.

Synthesis and Characterization of Iron(II) Complexes

The iron(II) complex [FeII(Me4[15]aneN4)(SPh)]BPh4 (2) was prepared according to Scheme 1. Successful synthesis of 2 requires the use of an anhydrous metal salt in combination with dry, aprotic solvents. Attempts to synthesize 2 from hydrated metal salts such as Fe(BF4)2•6H2O, or protic solvents such as MeOH, were unsuccessful. It was previously shown by Halfen and coworkers that the synthesis of the related cyclam complex [FeII(Me4cyclam)(SC6H4-p-OMe)]OTf requires the use of rigorously dry, aprotic conditions, such as employing the specially prepared triflate starting material, Fe(OTf)2•CH3CN, in dry THF. It was suggested that these conditions were necessary to avoid protonation of the tetraamine macrocycle.28

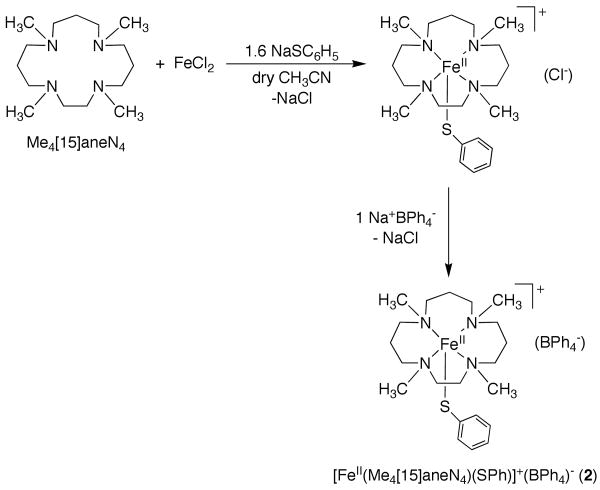

Scheme 1.

As shown in Scheme 1, the reaction of anhydrous FeCl2 with Me4[15]aneN4 in dry CH3CN results in the insertion of FeII into the Me4[15]aneN4 cavity, as evidenced by the fact that FeCl2, which is sparingly soluble in CH3CN, gradually dissolves upon addition of Me4[15]aneN4 to give a yellow-brown solution. The thiolate donor is then added as a solution of the sodium salt (NaSC6H5) in CH3CN, leading to the formation of a dark brown solution and a white precipitate, presumably NaCl. As found for the syntheses of the thiolate-ligated complexes [(FeII([15]aneN4)(SAr)]+,25 the preparation of [FeII(Me4[15]aneN4)(SPh)]+ was quite sensitive to the amount of arylthiolate ligand used. It was found that addition of a slight excess of the thiolate ligand (1.6 equiv) was optimal for obtaining 2 in good yield as a crystalline solid. Crystals of 2 were obtained via metathesis of the chloride anion with the non-coordinating, bulky tetraphenylborate anion, followed by recrystallization from CH2Cl2/Et2O. This preparation was used to prepare X-ray quality crystals as well as for routine preparation of the complex for all other studies.

We prepared the known, non-thiolate ligated iron(II) complex [FeII(Me4[15]aneN4)(OTf)2] (3) in order to examine a close analog of 2 that did not contain a thiolate donor, thereby giving us a direct means of determining the influence of the thiolate donor on the structure and reactivity of the iron(II) center. The synthesis of 3 from Fe(OTf)2 and Me4[15]aneN4 was reported previously,36 and we followed this same method except for the recrystallization procedure, which involved vapor diffusion of Et2O directly into reaction mixtures of 3. We found that higher yields of 3 could be obtained by vapor diffusion of Et2O into solutions of 3 in CH2Cl2.

X-ray Structural Studies

X-ray quality crystals of 2 were grown by vapor diffusion of Et2O into a methylene chloride solution of 2. The crystal structure of the cation of 2 is shown as an ORTEP diagram in Figure 1. Structural parameters are shown in Table 1, and selected bond lengths and angles are given in Table 2. There are two independent molecules of 2 in the unit cell, both of which are shown in Figure 1. The iron(II) center in each molecule is five-coordinate, with four nitrogen donors from the Me4[15]aneN4 ligand and a sulfur donor from the PhS- ligand completing the coordination sphere.

Figure 1.

ORTEP diagrams of the two independent complex cations of 2 (molecule 1, top; molecule 2, bottom) showing 30% probability thermal ellipsoids. Hydrogen atoms were omitted for clarity.

Table 2.

Selected Bond Distances (Å) and Angles (deg) for Complex 2.

| Fe1-N1 | 2.185(2) | N1-Fe1-N2 | 79.90(13) |

| Fe1-N2 | 2.340(5)1 | N1-Fe1-N3 | 143.48(10) |

| 2.386(16)2 | |||

| Fe1-N3 | 2.217(2) | N1-Fe1-N4 | 88.48(9) |

| Fe1-N4 | 2.267(2) | N3-Fe1-N4 | 90.51(9) |

| Fe1-S1 | 2.3540(8) | N2-Fe1-N3 | 90.96(13) |

| Fe2 -N5 | 2.157(2) | N2-Fe1-N4 | 162.28(13) |

| Fe2-N6 | 2.406(5)1 | N5-Fe2-N6 | 77.94(13) |

| 2.370(8)2 | |||

| Fe2-N7 | 2.177(2) | N5-Fe2-N7 | 143.47(9) |

| Fe2-N8 | 2.247(2) | N5-Fe-N8 | 90.29(9) |

| Fe2-S2 | 2.3459(7) | N6-Fe2-N7 | 91.34(13) |

| N6-Fe2-N8 | 163.30(14) | ||

| N7-Fe2-N8 | 91.21(9) |

Major component in which the CH2CH2 group of the ligand is in one position

Minor component in which CH2CH2 group of the ligand is in another position

Both molecules exhibit distorted square pyramidal geometries (τ43 = 0.31; square pyramid = 0 < τ < 1.0 = trigonal bipyramid) and differ mainly in the relative position of the phenylthiolate ligand. In molecule 1 (Fe1), the phenyl ring of the PhS- group sits directly over N2, such that the torsion angle defined by N2-Fe1-S1-C(Ph) is nearly zero (-4.55 (17)°). In molecule 2, the phenyl ring of the thiolate ligand is rotated almost 180° in relation to molecule 1, being positioned directly over N8 and resulting in a torsion angle of N6-Fe2-S2-C(Ph) = -171.99(18)°. An ethyl bridge between N1 and N2 (molec 1) and N5 and N6 (molec 2) is positionally disordered with an adjacent propyl bridge, which was well modeled in the final refinements.

The four methylated nitrogen atoms are chiral, and as a consequence there are six possible diastereomers that can be characterized by the positions of the methyl groups in relation to the plane of the N donors. The diastereomer that is seen in Figure 1 is the “3-up-1-down” (trans-I40) configuration, in which one N-CH3 group (N(2)-CH3 and N(6)-CH3) is on the same side of the macrocyclic plane as the thiolate ligand, while the other three N-CH3 groups lie on the opposite side. This is the same as that observed previously for the N-H groups in [FeII([15]aneN4)(SAr)]BF4.25 In comparison, the 6-coordinate complex [FeII(Me4[15]aneN4)](OTf)2 (3) is found in a 2-up-2-down configuration (trans-II).36 This configuration likely helps reduce the steric interactions between the two axial triflate ligands and the N-CH3 groups. Similarly, in 5-coordinate 2 the 3-up-1-down configuration helps to minimize steric repulsion between the phenylthiolate ligand and the N-Me substituents. To our knowledge there are no other structurally characterized Me4[15]aneN4 complexes with the exception of [Ru(Me4[15]aneN4)(O)2](ClO4)2.44 There are some structures of the 14-membered analog, such as [Ru(Me4[14]aneN4)(O)(Cl)]+, which is 6-coordinate like complex 3, but found in the “3-up-1-down” configuration, or [Ru(Me4[14]aneN4)(O)2]+, which is found in the “4-up” configuration. Both [RuIV(Me4[14]aneN4)(O)(NCCH3)]2+45 and [FeIV(Me4[14]aneN4)(O)(NCCH3)]2+46 have been crystallographically characterized and are also found in the “4-up” configuration, where the four methyl groups point toward the NCCH3 ligand. The 6-coordinate complexes therefore do not necessarily favor a 2-up-2-down configuration as seen for the bis-triflate complex 3.

The average Fe-N distances for 2 are 2.2410 and 2.2468 Å for molecules 1 and 2 respectively, and fall in line with other high-spin FeII complexes, including complex 336 (Fe-NAVE = 2.2445 Å). These bonds are slightly elongated compared to the average Fe-N distance of 2.1953 Å for the non-methylated complex [FeII([15]aneN4)(SPh)]BF4. The Fe-S bond distances of 2.3540(8) and 2.3459(7) Å for molecules 1 and 2, respectively, are typical for high-spin FeII-SR complexes,47-49 and are similar to the Fe-S bond distance for [FeII([15]aneN4)(SPh)]BF4. The Fe-N and Fe-S distances are also similar to those found in the reduced (FeII) form of SOR for the His and Cys donors,8,50-52 and thus complex 2 is a good structural model of this site.

Methylation of the secondary amines in [15]aneN4 make it a weaker-field ligand. This weakening is evident in the slight elongation of the average Fe-N distance for 2 as compared to [FeII([15]aneN4)(SPh)]BF4. This result is in line with previous work from Meyerstein53,54 and Wieghardt,30 which showed that alkylation of the amine donors in this kind of macrocyclic ligand should result in a weaker-field ligand. DFT calculations also support this conclusion.30

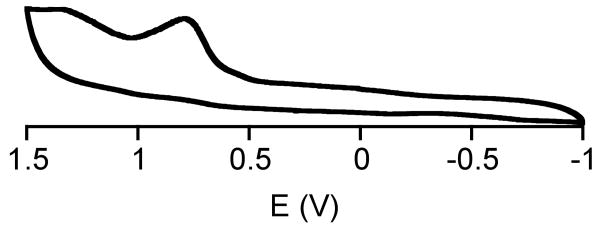

Electrochemistry

The cyclic voltammogram for 2 is shown in Figure 2. An irreversible oxidation wave is observed, with an anodic potential of +780 mV (vs Ag/AgCl), which we assign to the FeIII/II couple. In comparison, (FeII([15]aneN4)(SPh)]BF4 (1) exhibits a FeIII/II potential at +501 mV.25 Thus alkylation of the amine donors makes the complex more difficult to oxidize by 279 mV, supporting the conclusion that alkylation of the nitrogen atoms in Me4[15]aneN4 makes it a much weaker donor than the nonalkylated [15]aneN4. Solvation factors have been invoked to account for the effect of N-methylation on the redox potentials of nickel(II/I) and chromium(III/II) cyclam complexes,32,55 and may also contribute to the difference in redox potentials between 1 and 2.

Figure 2.

Cyclic voltammogram for [FeII(Me4[15]aneN4)(SPh)]BPh4 in CH2Cl2 using a Ag/AgCl reference electrode (3.5 M KCl).

The redox potential for the enzyme SOR has been measured by different methods, giving a range of 200 – 365 mV for the FeIII/FeII couple.19,56-58 The oxidation of 2 is clearly at a much higher potential than that of the enzyme, as has been found for other SOR models from our group and others.25 Multiple factors are likely to contribute to the differences in redox potentials between the enzyme and model complexes (e.g. aqueous vs nonaqueous conditions, H-bonding).

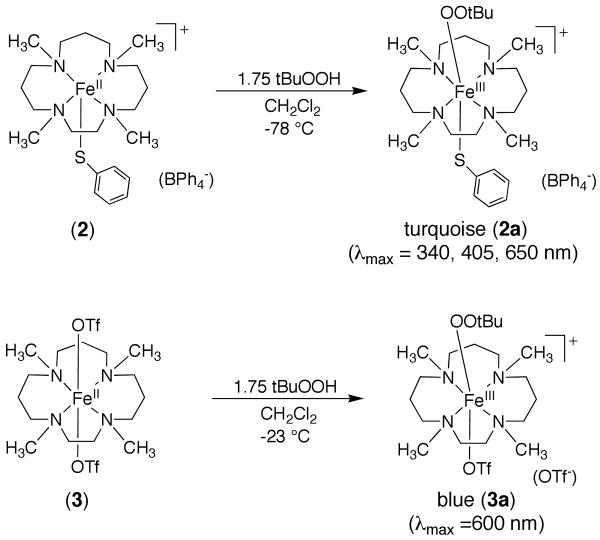

Reaction of FeII Complexes with Alkylhydroperoxides (ROOH)

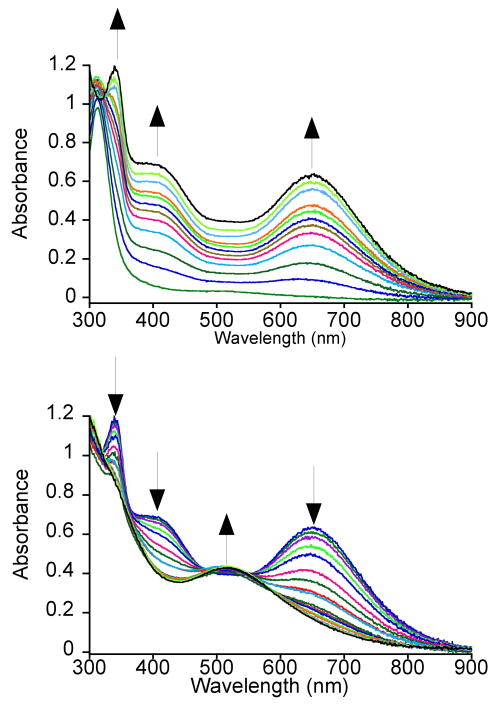

Addition of tBuOOH to 2 in CH2Cl2 at −78 °C leads to a rapid color change from colorless for the iron(II) complex to a turquoise green characteristic of a metastable species 2a (Scheme 2). The new turquoise species gives rise to a UV-vis spectrum with λmax at 340, 405 and 650 nm (Figure 3). The peak at 650 nm (ε = 2300 M-1cm-1) is assigned as an alkylperoxo-to-iron(III) LMCT band based on both the energy of this transition and its molar absorptivity.16,59-61 There is an intense feature in the spectrum of the FeII complex 2 at λmax = 313 nm that can be assigned to a S → FeII charge-transfer band based on a detailed analysis of a series of closely related iron(II)-thiolate complexes.28 This band apparently shifts to 340 nm upon formation of 2a. A number of thiolate-to-iron(III) CT bands have been assigned previously by spectroscopic and computational methods, although bands in the high-energy region (λmax < 400 nm) are more difficult to identify exclusively as S → FeIII CT bands because of possible overlap with other transitions.19,62 We suggest that the peak at 340 nm seen for 2a is an S → FeIII CT band, and the fact that this peak is absent in the triflate-derived alkylperoxo-iron(III) complex (vide infra) supports this assignment. However, this assignment must remain tentative until a more detailed spectroscopic and/or theoretical analysis can be carried out. The shoulder at 405 nm grows in together with the 340 and 650 nm bands, clearly arising from 2a as well. The mechanism of formation of the alkylperoxo species likely follows that proposed previously for the nonmethylated complexes, occurring in two steps. The initial step involves conversion of the FeII complex to an FeIII complex, presumably FeIII-OH, via oxidation with 0.5 equiv of ROOH. This step is then followed by displacement of hydroxide by ROOH to give FeIII-OOR. Our earlier work on the nonmethylated analogs provided evidence for such a mechanism from titration studies, and Que and coworkers have provided data in support of this mechanism for the formation of other Fe-OOR(H) complexes from FeII + ROOH or H2O2.18,63

Scheme 2.

Figure 3.

UV-vis spectral changes for the reaction of [FeII(Me4[15]aneN4)(SPh)](BPh4) and tBuOOH in CH2Cl2 at -78 °C, showing the formation (top) and decay (bottom) of [FeIII(Me4[15]aneN4)(SPh)(OOtBu)]+ (2a). The formation was monitored every 30 s for 45 min, and the decay was monitored every 2 - 5 minutes up for 40 min (select spectra shown for clarity).

The spectrum for the turquoise species evolves over ∼40 min, and then gradually decays with a similar rate to a purple species with a broad absorption centered at 514 nm (Figure 3). This purple species is stable for several hours at low temperature, but decays rapidly upon warming to room temperature. The broad absorption at 514 nm is consistent with an alkylperoxo-to-iron(III) LMCT band, but this spectrum lacks the 340 nm feature observed in 2a. These data suggest that the thiolate ligand may be lost in the purple species (vide infra). For the nonmethylated analogs [FeIII([15]aneN4)(SAr)(OOR)]+, it was shown that the thiolate ligand is converted to disulfide upon decomposition of the alkylperoxo-iron(III) complex at low-temperature.25

The UV-vis spectrum for the nonmethylated [FeIII([15]aneN4)(SPh)(OOtBu)]+ exhibits an alkylperoxo-to-iron(III) LMCT band at 526 nm, corresponding to a deep burgundy-colored intermediate, whereas the tetramethylated complex 2a exhibits a strongly red-shifted absorption at 650 nm associated with the turquoise choromophore. Thus there is a strong influence of N-methylation on the alkylperoxo-to-iron(III) LMCT band, and previous work from others supports this notion.53,64-68 For example, Meyerstein and coworkers observed a red shift in the N-to-CuII LMCT band of a CuII complex upon methylation of a linear polyamine ligand.53 The lowering in energy of the alkylperoxo-to-iron(III) band for 2a also tracks with the increase in the oxidation potential for this complex versus the unmethylated analog. It is reasonable to assume that the energy of the alkylperoxide orbital involved in the LMCT transition remains essentially the same for 2a and its unmethylated analog.

The increase in the oxidation potential for 2 suggests a stabilization of the HOMO, probably dominated by metal d orbital character, which also results in a lowering of the energy of the LMCT transition in the alkylperoxo complex. This analysis, however, does not take into account the spin-state change that occurs on going from the unmethylated analog to 2a (vide infra). The same correlation for a series of FeIII-OOH complexes has been made, where an increase in the FeIII/II potential of iron(II) precursors was found to be linearly dependent on a decrease in the energy of the hydroperoxo-to-iron(III) LMCT absorptions.18

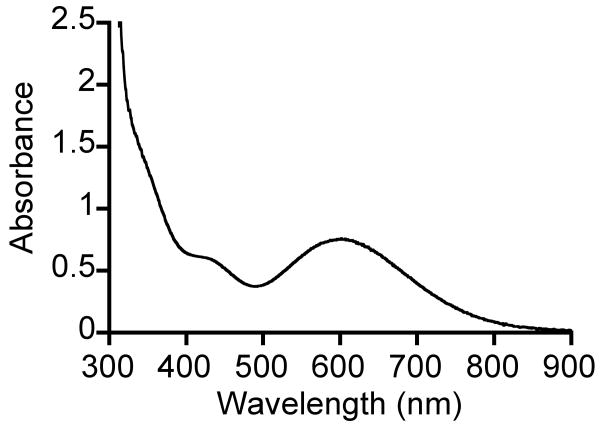

The non-thiolate-ligated complex FeII(Me4[15]aneN4)(OTf)2 does not react with tBuOOH at -78 °C, but once the temperature is raised to -40 °C, a faint blue color develops. Moreover, when the reaction is run at -23 °C, a gradual color change takes place from colorless FeII to dark blue (Scheme 2). Low-temperature UV-vis reveals a peak with λmax 600 nm (ε = 1080 M-1cm-1), indicative of an alkylperoxo-to-iron(III) LMCT band (Figure 4). This new blue species, 3a, forms over 60 min and then decays with a similar rate to give a yellow solution. The appearance of a second chromophore in the decay of 3a was not observed (Figure S1), in contrast to what was seen for the decay of 2a. The necessity to employ higher temperatures in the reaction of 3 may be a consequence of the lack of an open site on the metal, hindering the initial coordination and oxidation by ROOH.

Figure 4.

UV-vis spectrum of [FeIII(Me4[15]aneN4)(OTf)(OOtBu)]+ (3a) in CH2Cl2 at -23 °C.

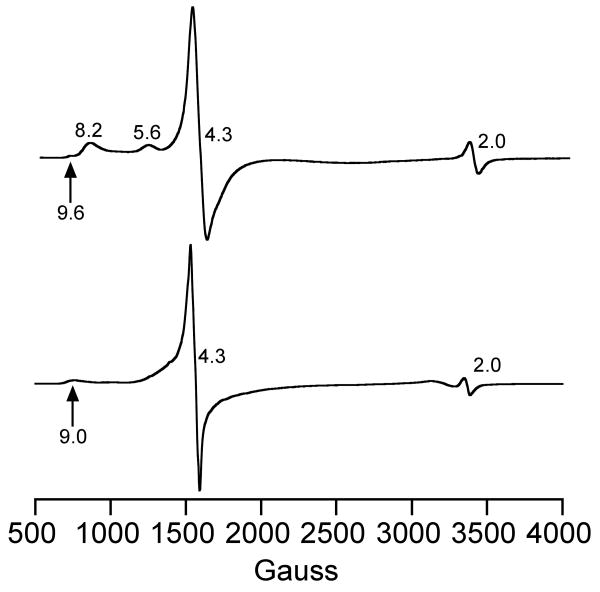

EPR Spectroscopy

The X-band EPR spectra for 2a and 3a in CH2Cl2 at 15 K are shown in Figure 5, and the g values are collected in Table 3 with other literature values for comparison. The spectra are typical of high-spin (S = 5/2) iron(III) complexes. The turquoise complex 2a (Figure 5a) exhibits a sharp, intense peak at g 4.3 that extends out on the low-field side by over 400 G. Additional peaks are seen at g 8.2 and 5.6, along with a small but reproducible feature at g 9.6, and another small signal at g 2.0 which is likely a radical impurity. There are no signals that can be attributed to a low-spin (S = ½) iron(III) species, such as seen for the unmethylated analog [FeIII([15]aneN4)(SPh)(OOtBu)]+.

Figure 5.

X-band EPR spectra of [FeIII(Me4[15]aneN4)(SPh)(OOtBu)]+ (top) and [FeIII(Me4[15]aneN4)(OTf)(OOtBu)]+ (bottom) in CH2Cl2 at 15 K. Experimental conditions, (top, bottom): Frequency, 9.475 GHz; microwave power, 2 mW; modulation frequency, 100 kHz; modulation amplitude, 10.0 G; receiver gain, 5.02 × 103.

Table 3.

Vibrational, UV-vis, and EPR Data for High-Spin FeIII-OOR Complexes.

| High-spin FeIII-OOR complexesa | ν(Fe-O) (cm-1) | ν(O-O) (cm-1) | λ (nm) | EPR g values | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [FeIII(Me4[15]aneN4)(SPh)(OOtBu)]+ (2a) | 584 | 843, 872 | 650 | 9.6, 8.2, 5.6, 4.3 | b |

| [FeIII(Me4[15]aneN4)(OTf)(OOtBu)]+ (3a) | 612 | 871 | 600 | 9.0, 4.3 | b |

| [FeIII(6Me3TPA)(OOtBu)(OH)]+ | 637 | 842, 877 | 562 | 4.3 | 76 |

| [FeIII(6Me3TPA)(OOtBu)(H2O)]2+ | 612 | 829, 867 | 562 | 4.3 | 76 |

| [FeIII(6Me2TPA)(OOtBu)(H2O)]2+ | 647 | 843, 881 | 552 | 4.3 | 76 |

| [FeIII(6MeTPA)(OOtBu)(H2O)]2+ | 682 | 790 | 600 | 4.3, 2.2, 2.12, 1.97c | 76 |

| [FeIII(L8Py2)(OOtBu)(OTf)]+ | 627 | 833, 870 | 580 | 8.8, 5.2, 3.2 | 20 |

| [FeIII(L8Py2)(OOtBu)(OBz)]+ | 623 | 832, 873 | 545 | --- | 20 |

| [FeIII(L8Py2)(OOtBu)(SAr)]+ | 623 | 830, 874 | 510 | --- | 20 |

| [FeIII(L8Py2)(OOtBu)(OPy)]+ | 623 | 831, 878 | 550 | --- | 20 |

| [FeIII(bppa)(OOtBu)]2+ | 629 | 873, 838 | 613 | 7.58, 5.81, 4.25, 1.82 | 77 |

| [FeIII(bppa)(OOCm)]2+ | 639 | 878, 838 | 585 | 7.76, 5.65, 4.20, 1.78 | 77 |

Abbreviations: TPA = tris(2-pyridylmethyl)amine; L8Py2 = N,N-bis(2-pyridylmethyl)-1,5-diazacyclooctane; BPPA = bis(6-pivalamido-2-pyridylmethyl)(2-pyridylmethyl)amine.

This work.

Mixed high-spin and low-spin species.

At first glance the intense signal at g 4.3 and the small feature at g 9.6 may be assigned to a purely rhombic high-spin FeIII with λ, = E/D = 1/3, while the features at g 8.2 and 5.6 could be associated with an intermediate λ, value of ∼0.1, suggesting the presence of two different iron species. However, a recent, detailed EPR study by Nilges and Wilker on high-spin FeIII-catecholate complexes shows that simulations of X-band EPR spectra based on only one high-spin FeIII component with λ < 1/3 reproduce all of the same spectral features seen for 2a.69 The EPR spectrum for 2a was quantitated by double integration of the high-spin iron(III) region (600 – 2400 G) and comparison with a calibration curve constructed from an FeIII-EDTA standard for an S = 5/2 ion.70,71 This analysis gives an 80% yield for 2a, assuming the high-spin FeIII signals arise only from 2a. To further explore if the high-spin FeIII EPR signals were coming from one species (i.e. 2a) or multiple components, EPR spectra were monitored at different reaction times (30 – 120 min). As seen in Figure S2, the g 4.3, 5.6, and 8.2 peaks appear to broaden and shift over time. At the end of the time course a new feature at g ∼6.7 is apparent, together with broad peaks at g ∼5.6 and g ∼4.3. Although a detailed analysis of these spectral changes is complicated due to the overlapping and broad nature of the features in this region, the peaks at g 8.2, 5.6, and 4.3 do not appear to interconvert or decay independently of each other. Double integrations at each time-point give a relatively constant value of spins versus total iron content (79 - 87%). Thus these data are consistent with our assignment of the g 8.2, 5.6 and 4.3 peaks coming from a single species, although multiple species cannot be definitively ruled out. Taken together, these data are consistent with our assignment of 2a as a high-spin alkylperoxo-iron(III) complex, [FeIII(Me4[15]aneN4)(SPh)(OOtBu)]+.

The spectrum for the triflate-ligated 3a (Figure 5b) is characterized by peaks at g 9.0 and 4.3, where the g 4.3 resonance extends out ∼500 G to the low-field side, and can be assigned to a high-spin iron(III) complex following Nilges and Wilker.69 The small signal at g 2.0 is likely a radical impurity as seen in the spectrum for 2a. The EPR spectrum for 3a is markedly different from that of 2a, and in particular the dominant feature (g ∼4.3) appears significantly broadened for 2a. Qualitatively, this difference results from the triflate-coordinated complex more closely approaching ideal rhombic symmetry, while the thiolate-coordinated complex is more distorted. We choose not to speculate as to the electronic or geometrical origins of this effect, but simply note that the difference in axial ligands (thiolate vs triflate) has a distinct effect on the electronic structure of the FeIII-OOR unit as reflected in the EPR spectra.

The major finding to emerge from the EPR data is that N-methylation of [15]aneN4 leads to a high-spin ground state (S = 5/2) for the iron(III)-alkylperoxo species. Previously, it was shown by EPR that the nonmethylated complexes [FeIII([15]aneN4)(SAr)(OOR)]+ were all low-spin FeIII (S = ½). This result is consistent with our findings regarding the influence of the methyl groups; methylation causes a significant weakening of the amine donor strength in [15]aneN4, and thus alkylation at nitrogen provides access to high-spin FeIII-OOR complexes.

Resonance Raman Spectroscopy

The RR spectra of 2a obtained at 110 K are shown in Figure 6. With a 647-nm laser excitation that coincides with the absorption maximum, the RR spectrum exhibits strong resonance-enhanced vibrations near 450 cm-1, 584 cm-1, 843 cm-1, and 872 cm-1. Preparing 2a with tBu18O18OH affects all of these RR signals. The bands near 450 cm-1 are only moderately perturbed by 18O-labeling, and are assigned to (C-C-C) and (C-C-O) deformation modes of the alkylperoxo ligand as in previous RR characterization of iron(III)-alkylperoxo species.15,16,25,34 The 584-cm-1 band which shifts −19 cm-1 with tBu18O18OH is assigned to the ν(Fe–O) (Table 3). Finally, the two strong bands at 872 and 843 cm-1 are replaced after labeling with tBu18O18OH by a weak 843-cm-1 band and a strong band at 815 cm-1 readily assigned to the ν(18O–18O) mode. The enhancement of the 843 cm-1 band in unlabeled 2a most likely originates from Fermi coupling between ν(O-O) and ν(C-C) of the OOtBu group as previously noted for related complexes.15,72 In agreement with this analysis, using a ν(18O–18O) = 815 cm-1 to calculate the ν(16O-16O) assuming a simple diatomic oscillator leads to a 864.5 cm-1 value, intermediate between the 843 and 872 cm-1 bands observed in 2a. These ν(O-O) values are comparable to other frequencies reported for high-spin alkylperoxo complexes (Table 3), but the ν(Fe–O) of 2a is 40 to 60 cm-1 lower than those observed for other high-spin alkylperoxo complexes. This ν(Fe-O) is also significantly lower than that seen for the low-spin complex [FeIII([15]aneN4)(SPh)(OOtBu)]+ (ν(Fe-O) = 615 cm-1).25 As previously with the unmethylated low-spin FeIII-OOR complexes, the RR spectra of 2a show no evidence of Fe-S stretching vibrations in the 300 to 400 cm-1 region (see Supporting Information).

Figure 6.

RR spectra of a) [FeIII(Me4[15]aneN4)(SPh)(OOtBu)]+ (2a) generated from tBu16O16OH (top, red) and tBu18O18OH (middle, blue), and [FeII(Me4[15]aneN4)(SPh)](BPh4) (2) (bottom, grey) obtained with 647-nm laser excitation and b) the purple species observed following the decay of 2a generated from tBu16O16OH (top, red) and tBu18O18OH (middle, blue) and 2 (bottom, grey) obtained with 514-nm laser excitation. Spectra recorded on frozen solutions (CH2Cl2) at ∼110 K. In each graph the spectra are normalized on Raman signals from CH2Cl2.

The purple species produced by the decay of 2a contributes only weakly to RR spectra obtained with 647-nm excitation (see Supporting Information), but the RR spectra obtained with 514-nm excitation for samples where the purple species was intentionally maximized show strong ν(Fe–O) and ν(O–O) vibrations at 614 and 844/889 cm-1, respectively (Figure 6b). At this excitation wavelength, the RR modes of 2a are only weakly enhanced (see Supporting Information). As with most iron(III)-alkylperoxo species, the RR spectrum of the purple species shows evidence of Fermi coupling between ν(O-O) and, presumably, the ν(C-C) of the OOtBu group. Labeling of the alkylperoxo moiety with 18O shifts the ν(O-O) mode to 810 cm-1, out of coupling range with the non-resonant ν(C-C) mode. Comparing ν(18O-18O) and ν(Fe-O) in the purple species and 2a reveals a modest downshift of the O-O stretch (−5 cm-1) and a +30 cm-1 upshift of the ν(Fe-O) in the purple species which is in line with the loss of a strong thiolate trans effect. The nature of the sixth ligand in this species has not been identified.73

The RR spectra for the blue species 3a, prepared from the reaction of [FeII(Me4[15]aneN4)(OTf)2] (3) and tBuOOH at -23 °C, are shown in Figure 7. The RR spectra, obtained with a 647-nm excitation, show a set of ν(Fe–O) and ν(O–O) vibrations at 612 and 871 cm-1 that downshift to 591 and 822 cm-1 with tBu18O18OH, respectively. These data confirm the assignment of 3a as the iron(III)-alkylperoxo complex [FeIII(Me4[15]aneN4)(OTf)(OOtBu)]+. In contrast with the RR spectra of 2a, the region corresponding to the (C-C-C)/(C-C-O) deformation modes of 3a shows a single band at 456 cm-1 that shifts −6 cm-1 with tBu18O18OH. Importantly, the lack of a trans thiolate ligand in 3a results in a ν(Fe-O) 18-cm-1 higher than in 2a, while its ν(18O-18O) mode upshifts 7-cm-1 compared to 2a (Table 3).

Figure 7.

RR spectra of [FeIII(Me4[15]aneN4)(OTf)(OOtBu)]+ (3a) generated from tBu16O16OH (top, red) and tBu18O18OH (middle, blue), and [FeII(Me4[15]aneN4)(OTf)2] (3) (bottom, grey). Spectra were recorded on frozen solutions (CH2Cl2) at ∼110 K with 647-nm laser excitation.

As pointed out in the Introduction, the spin states of FeIII-OOR(H) complexes have been suggested to strongly influence the Fe-O and O-O vibrations and accompanying bond strengths. Specifically, a low-spin ground state (S = ½) should result in relatively strong Fe-O and weak O-O bonds, while a high-spin ground state (S = 5/2) should lead to weak Fe-O and strong O-O bonds.15,16,25 The low-spin complexes [FeIII([15]aneN4)(SAr)(OOR)]+ exhibited low ν(Fe-O)s between 600 and 623 cm-1 that did not follow the expected trend for low-spin vs high-spin FeIII-OOR complexes. These unusually low ν(Fe–O)s were assigned to a trans effect of the thiolate donor, and it was shown that the electron-donating power of the different thiolate ligands correlated closely with the Fe-O vibrational frequencies. The 18O-downshifts of the ν(Fe–O) and ν(O–O) bands for the low spin, unmethylated complexes matched those predicted for simple diatomic oscillators, and permitted a direct interpretation of vibrational energies in terms of bond strengths. For the high-spin species 2a, the observed isotopic downshifts deviate from calculated values for simple diatomic models (Δν(Fe–16/18O) exptl (calc) = −19 (−28) cm-1 and Fermi coupled ν(16O–16O) doublet), and therefore interpreting vibrational frequency in terms of bond strengths is less straightforward. However, the present work demonstrates that both the tetramethylated and nonmethylated thiolate-ligated SOR model complexes do follow the expected trend in ν(Fe–O) and ν(O–O) vs iron spin state, with the important finding that ν(Fe–O) is dramatically weakened by the axial thiolate donor for both high-spin and low-spin species. In contrast, the ν(O-O) frequencies appear to be only marginally affected by the thiolate ligand. To our knowledge this study is the first in which the influence of a ligand trans to a peroxo moiety has been evaluated for a structurally equivalent pair of high-spin/low-spin peroxo-iron(III) complexes.

The triflate-ligated complex 3a and the thiolate-ligated complex 2a exhibit comparable ν(O-O)s (as judged by the ν(18O-18O) modes which show no evidence of Fermi coupling) but different ν(Fe-O)s. The more weakly donating triflate ligand leads to a ∼30 cm-1 increase in ν(Fe–O) compared to the thiolate ligand. These results contrast with what was seen in the high-spin complexes [FeIII(L8Py2)(OOtBu)(X)]+ (X = OTf, OBz, SAr, OPy), where the iron-alkylperoxo ν(Fe-O) is largely insensitive to a change in the nature of the trans ligand (Table 3). For these complexes, only the ν(Fe-O) of the triflate-ligated species exhibited a small upshift of 4 cm-1 compared to the other complexes. The lack of sensitivity of ν(Fe-O) to the nature of the sixth ligand was not discussed.20

Our results on the high-spin complexes parallels our findings for the low-spin complexes, in which ν(Fe-O) are sensitive to the identity of the trans donor ligand, while ν(O-O) are only marginally affected. These results support the strikingly similar findings that have been obtained for (hydro)peroxo-iron(III) adducts of SOR, where a weakening of the SCys-FeIII bond correlates with a strengthening of the Fe-O bond, but has little or no affect on the O-O bond.6,23 In fact, there is a growing body of evidence to suggest that the nature of the S-Fe interaction in SOR plays a critical role in catalysis.3,23,74,75 Our findings and those on the enzyme are in agreement, and show that the traditional “push effect” invoked for heme enzymes, where the thiolate donor helps to weaken the O-O bond and thereby favor O-O bond cleavage, is not observed in either our low-spin or high-spin nonheme iron models, or in the native enzyme itself. However, these findings do not rule out a possible push effect on excited state species (e.g. transition state in O-O bond cleavage) during the formation and decay of an iron-peroxide.

Summary and Conclusions

The alkylated ligand Me4[15]aneN4 has been used to prepare a new thiolate-ligated, (N4S)FeII complex as an accurate structural model of the reduced form of SOR. This complex adds to the small, but growing number of thiolate-ligated SOR models. Previously we prepared a series of structurally analogous SOR models with the nonalkylated ligand [15]aneN4. We found that the addition of methyl groups on the amine donors has a dramatic impact on the donating properties of the macrocycle, making Me4[15]aneN4 a significantly weaker donor than [15]aneN4. We have shown that the tetramethylated iron(II) complex is capable of producing the metastable alkylperoxo species [FeIII(Me4[15]aneN4)(SPh)(OOtBu)]+ (2a), despite the potential steric crowding of the metal center from the methyl groups. This complex is a rare example of an iron-peroxo species that contains a thiolate donor in the coordination sphere. Importantly, alkylation at nitrogen induces a spin state change for the alkylperoxo species from low-spin to high-spin iron(III). The change in spin state causes a dramatic shift in the Fe-O and O-O vibrations of the Fe-OOtBu unit, in which ν(Fe–O) drops to lower energy by ∼30 cm-1 and ν(O–O) increases by ∼60 cm-1. The ν(Fe–O) for this high-spin alkylperoxo species 2a is lower than all other known high-spin alkylperoxo complexes lacking a thiolate ligand.

This work has allowed for a direct comparison of iron-peroxo species with low-spin and high-spin iron(III) in nearly identical ligand environments. Previously, our data for the thiolate-ligated low-spin FeIII-OOR model complexes, and in particular their very low ν(Fe-O), suggested that these models may not follow the trend of other low-spin FeIII-OOR species that yield strong Fe-O and weak O-O bonds compared to high-spin homologues. However, the characterization of the thiolate-ligated high-spin FeIII-OOR 2a shows an equally low ν(Fe-O) when compared to other high-spin Fe-OOR species. Thus, these studies demonstrate that the addition of the trans thiolate ligand in both low-spin and high-spin species induces a large weakening of the ν(Fe-O) without major change in ν(O-O). A new non-thiolate-ligated alkylperoxo complex was also generated, [FeIII(Me4[15]aneN4)(OTf)(OOtBu)]+ (3a), and exhibited a ∼30-cm-1 upshift in ν(Fe–O) but only a 7-cm-1 upshift in ν(O-O). These data provide strong evidence that the trans donor ligand in FeIII-OOR species has an important role in fine-tuning ν(Fe-O). Taken together, our results indicate that both spin state and trans-thiolate ligation play a critical role in determining the nature of the peroxo-iron interaction in models, and by analogy, in SOR. The His4Cys iron-binding site in SOR, as opposed to the porphyrinate/Cys ligand set found in cytochrome P450, may have been selected to ensure the formation of a high-spin FeIII-OO(H) intermediate with a relatively weak Fe-O bond, thereby favoring the release of H2O2 over O-O bond cleavage.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was support from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences at the NIH (D.P.G., GM62309; P.M.-L., GM74785). We thank Dr. J. Telser (Roosevelt University) and Dr. V. Szalai for discussions regarding the EPR spectra, and Dr. P. Kennepohl (University of British Columbia) for discussions regarding the UV-vis data.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Additional RR, UV-vis and EPR spectra, and X-ray structure file for complex 2 (CIF). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

References

- 1.Niviere V, Fontecave M. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2004;9:119–123. doi: 10.1007/s00775-003-0519-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurtz DM., Jr J Inorg Biochem. 2006;100:679–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2005.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dey A, Jenney FE, Adams MWW, Johnson MK, Hodgson KO, Hedman B, Solomon EI. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12418–12431. doi: 10.1021/ja064167p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang VW, Emerson JP, Kurtz DM., Jr Biochemistry. 2007;46:11342–11351. doi: 10.1021/bi700450u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kovacs JA, Brines LM. Acc Chem Res. 2007;40:501–509. doi: 10.1021/ar600059h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathé C, Weill CO, Mattioli TA, Berthomieu C, Houée-Levin C, Tremey E, Nivière V. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:22207–22216. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700279200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moura I, Pauleta SR, Moura JJG. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2008;13:1185–1195. doi: 10.1007/s00775-008-0414-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katona G, Carpentier P, Nivière V, Amara P, Adam V, Ohana J, Tsanov N, Bourgeois D. Science. 2007;316:449–453. doi: 10.1126/science.1138885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clay MD, Yang TC, Jenney FE, Kung IY, Cosper CA, Krishnan R, Kurtz DM, Jr, Adams MWW, Hoffman BM, Johnson MK. Biochemistry. 2006;45:427–438. doi: 10.1021/bi052034v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pereira AS, Tavares P, Folgosa F, Almeida RM, Moura I, Moura JJG. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2007:2569–2581. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sligar SG, Makris TM, Denisov IG. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;338:346–354. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaik S, Kumar D, de Visser SP, Altun A, Thiel W. Chem Rev. 2005;105:2279–2328. doi: 10.1021/cr030722j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loew GH, Harris DL. Chem Rev. 2000;100:407–419. doi: 10.1021/cr980389x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Denisov IG, Makris TM, Sligar SG, Schlichting I. Chem Rev. 2005;105:2253–2277. doi: 10.1021/cr0307143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lehnert N, Ho RYN, Que L, Jr, Solomon EI. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:12802–12816. doi: 10.1021/ja011450+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lehnert N, Ho RYN, Que L, Jr, Solomon EI. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:8271–8290. doi: 10.1021/ja010165n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silaghi-Dumitrescu R, Silaghi-Dumitrescu L, Coulter ED, Kurtz DM., Jr Inorg Chem. 2003;42:446–456. doi: 10.1021/ic025684l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roelfes G, Vrajmasu V, Chen K, Ho RYN, Rohde JU, Zondervan C, la Crois RM, Schudde EP, Lutz M, Spek AL, Hage R, Feringa BL, Münck E, Que L., Jr Inorg Chem. 2003;42:2639–2653. doi: 10.1021/ic034065p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clay MD, Jenney FE, Jr, Hagedoorn PL, George GN, Adams MWW, Johnson MK. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:788–805. doi: 10.1021/ja016889g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bukowski MR, Halfen HL, van den Berg TA, Halfen JA, Que L., Jr Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:584–587. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ogliaro F, de Visser SP, Shaik S. J Inorg Biochem. 2002;91:554–567. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(02)00437-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horner O, Mouesca JM, Oddou JL, Jeandey C, Niviere V, Mattioli TA, Mathe C, Fontecave M, Maldivi P, Bonville P, Halfen JA, Latour JM. Biochemistry. 2004;43:8815–8825. doi: 10.1021/bi0498151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mathé C, Nivière V, Houee-Levin C, Mattioli TA. Biophys Chem. 2006;119:38–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2005.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mathé C, Mattioli TA, Horner O, Lombard M, Latour JM, Fontecave M, Nivière V. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:4966–4967. doi: 10.1021/ja025707v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Namuswe F, Kasper GD, Sarjeant AAN, Hayashi T, Krest CM, Green MT, Moënne-Loccoz P, Goldberg DP. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:14189–14200. doi: 10.1021/ja8031828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brines LM, Kovacs JA. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2007:29–38. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kovacs JA. Chem Rev. 2004;104:825–848. doi: 10.1021/cr020619e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fiedler AT, Halfen HL, Halfen JA, Brunold TC. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:1675–1689. doi: 10.1021/ja046939s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Halfen JA, Moore HL, Fox DC. Inorg Chem. 2002;41:3935–3943. doi: 10.1021/ic025517l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berry JF, Bill E, Garcia-Serres R, Neese F, Weyhermüller T, Wieghardt K. Inorg Chem. 2006;45:2027–2037. doi: 10.1021/ic051823y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Che CM, Wong KY, Poon CK. Inorg Chem. 1986;25:1809–1813. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meyerstein D. Coord Chem Rev. 1999;186:141–147. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kitagawa T, Dey A, Lugo-Mas P, Benedict JB, Kaminsky W, Solomon E, Kovacs JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:14448–14449. doi: 10.1021/ja064870d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krishnamurthy D, Kasper GD, Namuswe F, Kerber WD, Sarjeant AAN, Moënne-Loccoz P, Goldberg DP. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:14222–14223. doi: 10.1021/ja064525o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walling C, Buckler SA. J Am Chem Soc. 1955;77:6032–6038. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suh Y, Seo MS, Kim KM, Kim YS, Jang HG, Tosha T, Kitagawa T, Kim J, Nam W. J Inorg Biochem. 2006;100:627–633. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2005.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.CrysAlis PRO. Oxford Diffraction Ltd.; Wroclaw, Poland: [Google Scholar]

- 38.SHeldrick GM. SHELXTL version 6.10. Bruker AXS Inc.; Madison, Wisconsin, USA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bhattacharya PK. Dalton Trans. 1980:810–812. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hay RW, Tarafder MTH. Dalton Trans. 1991:823–827. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Islam MS, Uddin MM. Polyhedron. 1993;12:423–426. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hung Y, Busch DH. J Am Chem Soc. 1977;99:4977–4984. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Addison AW, Rao TN, Reedjik J, van Rijn J, Verschoor GC. Dalton Trans. 1984:1349–1456. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mak TCW, Che CM, Wong KY. Chem Commun. 1985:986–988. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Che CM, Wong KY, Mak TCW. Chem Commun. 1985:546–548. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rohde JU, In JH, Lim MH, Brennessel WW, Bukowski MR, Stubna A, Münck E, Nam W, Que L., Jr Science. 2003;299:1037–1039. doi: 10.1126/science.299.5609.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krishnamurthy D, Sarjeant AN, Goldberg DP, Caneschi A, Totti F, Zakharov LN, Rheingold AL. Chem Eur J. 2005;11:7328–7341. doi: 10.1002/chem.200500156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mukherjee RN, Abrahamson AJ, Patterson GS, Stack TDP, Holm RH. Inorg Chem. 1988;27:2137–2144. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zang Y, Que L., Jr Inorg Chem. 1995;34:1030–1035. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Adam V, Royant A, Nivière V, Molina-Heredia FP, Bourgeois D. Structure. 2004;12:1729–1740. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Santos-Silva T, Trincao J, Carvalho AL, Bonifacio C, Auchere F, Raleiras P, Moura I, Moura JJG, Romao MJ. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2006;11:548–558. doi: 10.1007/s00775-006-0104-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yeh AP, Hu YL, Jenney FE, Jr, Adams MWW, Rees DC. Biochemistry. 2000;39:2499–2508. doi: 10.1021/bi992428k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Golub G, Cohen H, Paoletti P, Bencini A, Meyerstein D. Dalton Trans. 1996:2055–2060. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Golub G, Zilbermann I, Cohen H, Meyerstein D. Supramol Chem. 1996;6:275–279. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clark T, Hennemann M, van Eldik R, Meyerstein D. Inorg Chem. 2002;41:2927–2935. doi: 10.1021/ic0113193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jovanovic T, Ascenso C, Hazlett KRO, Sikkink R, Krebs C, Litwiller R, Benson LM, Moura I, Moura JJG, Radolf JD, Huynh BH, Naylor S, Rusnak F. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:28439–28448. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003314200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rodrigues JV, Saraiva LM, Abreu IA, Teixeira M, Cabelli DE. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2007;12:248–256. doi: 10.1007/s00775-006-0182-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tavares P, Ravi N, Moura JJG, LeGall J, Huang YH, Crouse BR, Johnson MK, Huynh BH, Moura I. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10504–10510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jensen MP, Costas M, Ho RYN, Kaizer J, Payeras AMI, Münck E, Que L, Jr, Rohde JU, Stubna A. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:10512–10525. doi: 10.1021/ja0438765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jensen MP, Payeras AMI, Fiedler AT, Costas M, Kaizer J, Stubna A, Münck E, Que L., Jr Inorg Chem. 2007;46:2398–2408. doi: 10.1021/ic0607787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Menage S, Wilkinson EC, Que L, Jr, Fontecave M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1995;34:203–205. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kennepohl P, Neese F, Schweitzer D, Jackson HL, Kovacs JA, Solomon EI. Inorg Chem. 2005;44:1826–1836. doi: 10.1021/ic0487068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim J, Zang Y, Costas M, Harrison RG, Wilkinson EC, Que L., Jr J Biol Inorg Chem. 2001;6:275–284. doi: 10.1007/s007750000198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bazzicalupi C, Bencini A, Cohen H, Giorgi C, Golub G, Meyerstein D, Navon N, Paoletti P, Valtancoli B. Dalton Trans. 1998:1625–1631. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bernhardt PV. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:771–774. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Golub G, Cohen H, Paoletti P, Bencini A, Messori L, Bertini I, Meyerstein D. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:8353–8361. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jubran N, Ginzburg G, Cohen H, Koresh Y, Meyerstein D. Inorg Chem. 1985;24:251–258. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wagner F, Barefield EK. Inorg Chem. 1976;15:408–417. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Weisser JT, Nilges MJ, Sever MJ, Wilker JJ. Inorg Chem. 2006;45:7736–7747. doi: 10.1021/ic060685p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Aasa R, Vänngård T. J Magn Reson. 1975;19:308–315. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bou-Abdallah F, Chasteen ND. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2008;13:15–24. doi: 10.1007/s00775-007-0304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lehnert N, Fujisawa K, Solomon EI. Inorg Chem. 2003;42:469–481. doi: 10.1021/ic020496g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Experiments aimed at better characterizing the status of the iron(III) coordination trans to the alkylperoxo ligand in the purple species were inconclusive. Specifically, addition of sodium benzenesulfinate, a likely oxidation product of the phenylthiolate ligand, to 3a did not convert this species to the purple complex (514 nm). Similarly, addition of sodium triflate to the purple species did not convert the latter species to 3a.

- 74.Clay MD, Cosper CA, Jenney FE, Adams MWW, Johnson MK. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:3796–3801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0636858100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Todorovic S, Rodrigues JV, Pinto AF, Thomsen C, Hildebrandt P, Teixeira M, Murgida DH. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2009;11:1809–1815. doi: 10.1039/b815489a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zang Y, Kim J, Dong YH, Wilkinson EC, Appelman EH, Que L., Jr J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:4197–4205. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wada A, Ogo S, Watanabe Y, Mukai M, Kitagawa T, Jitsukawa K, Masuda H, Einaga H. Inorg Chem. 1999;38:3592–3593. doi: 10.1021/ic9900298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.