Abstract

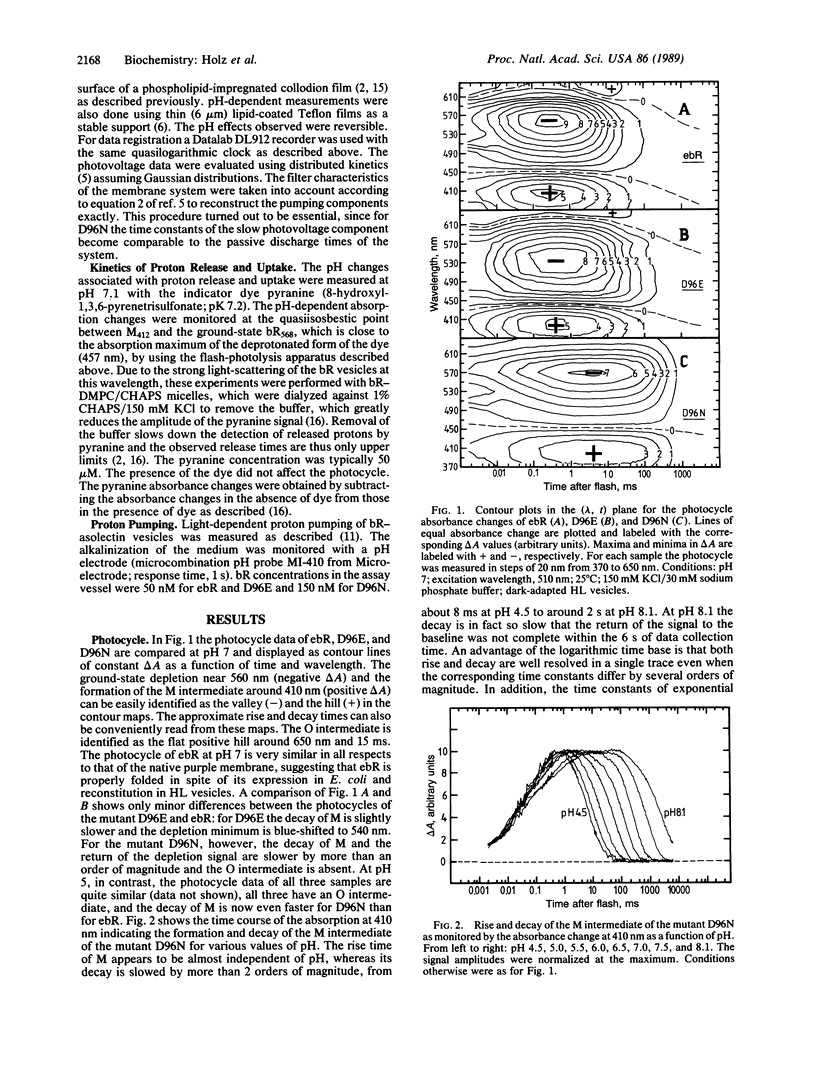

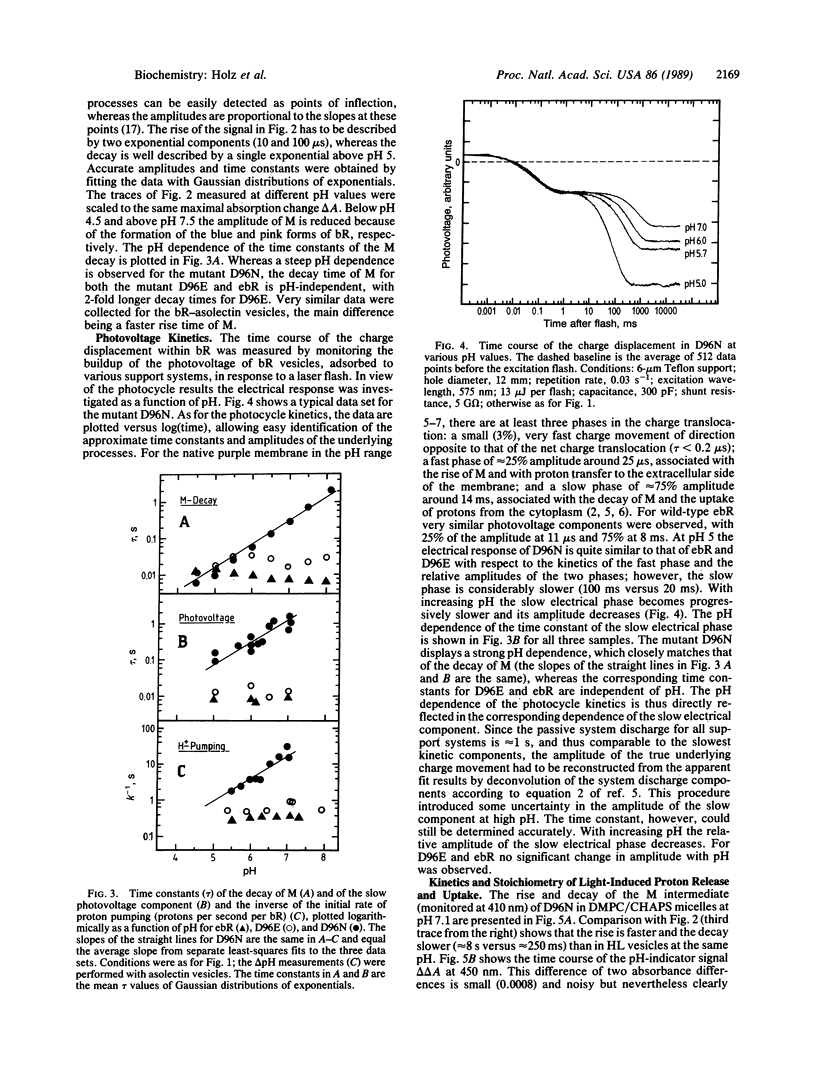

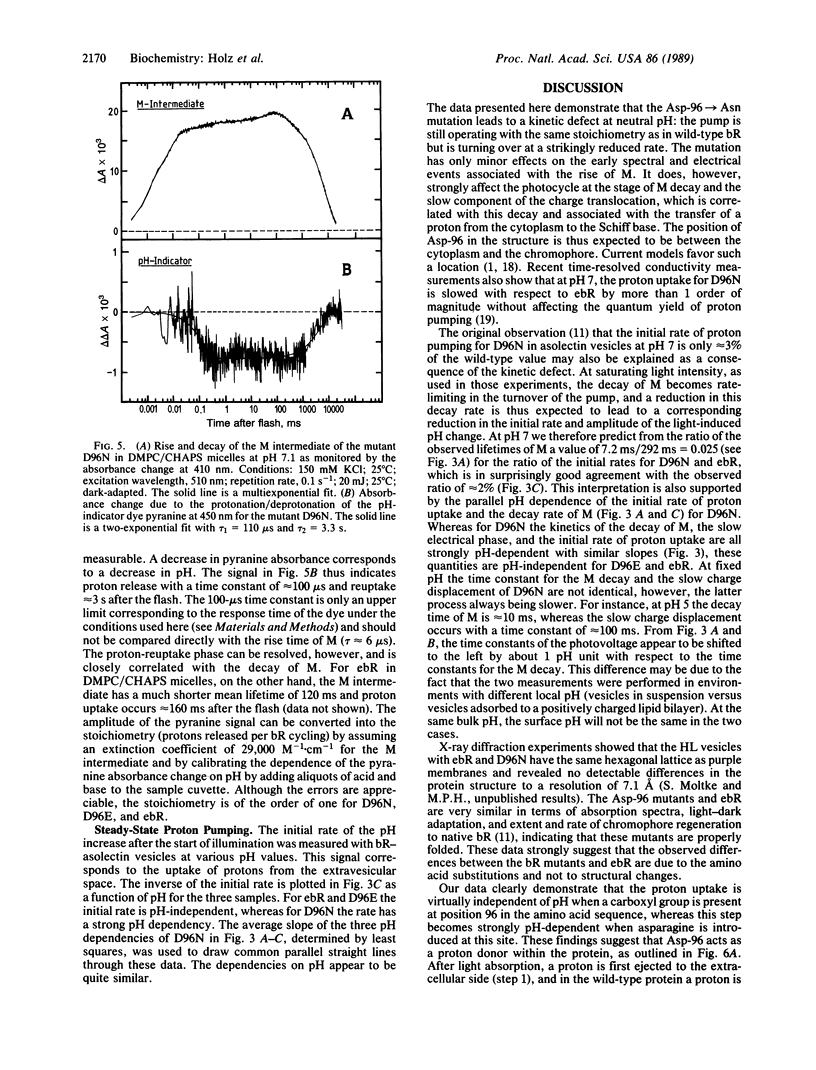

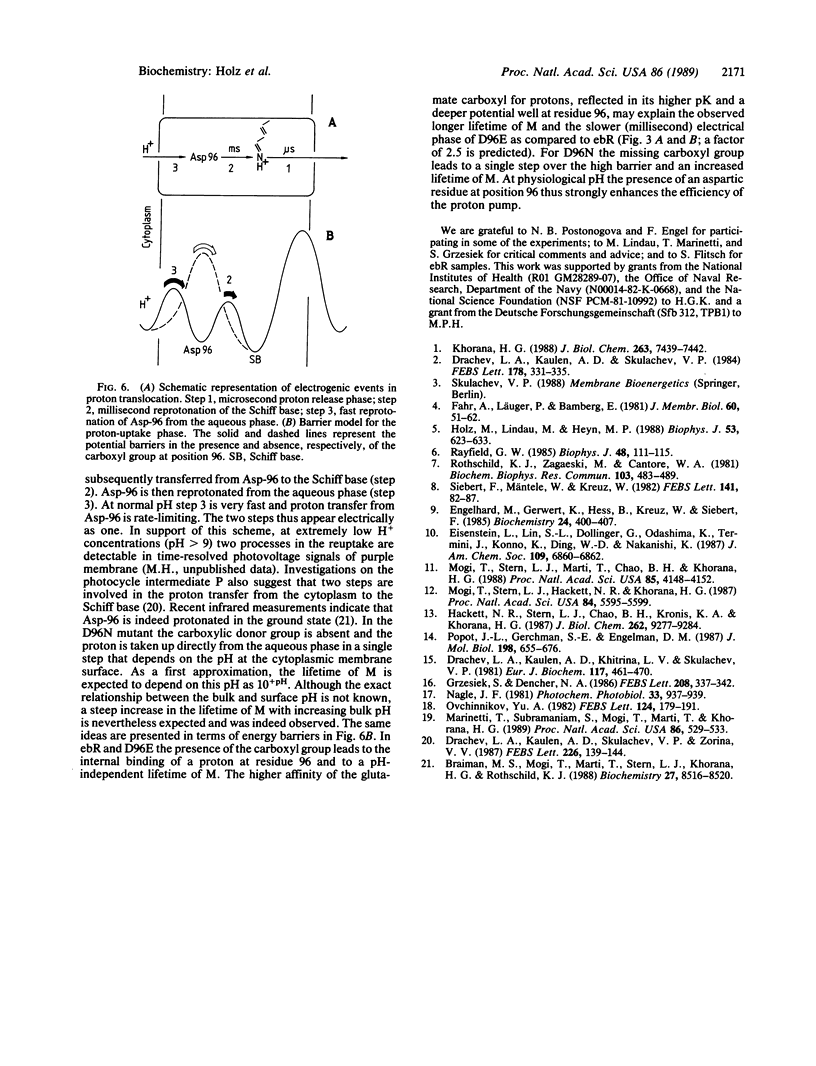

The photocycle, electrical charge translocation, and release and uptake of protons from the aqueous phase and release and uptake of protons from the aqueous phase were investigated for bacteriorhodopsin mutants with aspartic acid-96 replaced by asparagine or glutamic acid. At neutral pH the main effect of the Asp-96----Asn mutation is to slow by 2 orders of magnitude the decay of the M intermediate and the concomitant charge displacement associated with the reprotonation of the Schiff base from the cytoplasmic side of the membrane. The proton uptake measured with the indicator dye pyranine is likewise slowed without affecting the stoichiometry of proton pumping. The corresponding results for the Asp-96----Glu mutant, on the other hand, are very close to those for the wild-type protein. These results provide a kinetic explanation for the fact that at pH 7 and saturating light intensities the steady-state proton pumping is almost abolished in the Asp-96----Asn mutant but is close to normal in the Asp-96----Glu mutant. Thus, the pump is simply turning over much more slowly in the Asp-96----Asn mutant. The time constants of the decay of M and the associated charge translocation increase strongly with increasing pH for the Asp-96----Asn mutant but are virtually pH-independent for the Asp-96----Glu mutant and wild-type bacteriorhodopsin. At pH 5 the M decay of the Asp-96----Asn mutant is as fast as for wild type. These results suggest that Asp-96 serves as an internal proton donor in the proton-uptake pathway from the cytoplasm to the Schiff base.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Braiman M. S., Mogi T., Marti T., Stern L. J., Khorana H. G., Rothschild K. J. Vibrational spectroscopy of bacteriorhodopsin mutants: light-driven proton transport involves protonation changes of aspartic acid residues 85, 96, and 212. Biochemistry. 1988 Nov 15;27(23):8516–8520. doi: 10.1021/bi00423a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drachev L. A., Kaulen A. D., Khitrina L. V., Skulachev V. P. Fast stages of photoelectric processes in biological membranes. I. Bacteriorhodopsin. Eur J Biochem. 1981 Jul;117(3):461–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1981.tb06361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelhard M., Gerwert K., Hess B., Kreutz W., Siebert F. Light-driven protonation changes of internal aspartic acids of bacteriorhodopsin: an investigation by static and time-resolved infrared difference spectroscopy using [4-13C]aspartic acid labeled purple membrane. Biochemistry. 1985 Jan 15;24(2):400–407. doi: 10.1021/bi00323a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackett N. R., Stern L. J., Chao B. H., Kronis K. A., Khorana H. G. Structure-function studies on bacteriorhodopsin. V. Effects of amino acid substitutions in the putative helix F. J Biol Chem. 1987 Jul 5;262(19):9277–9284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holz M., Lindau M., Heyn M. P. Distributed kinetics of the charge movements in bacteriorhodopsin: evidence for conformational substates. Biophys J. 1988 Apr;53(4):623–633. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(88)83141-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khorana H. G. Bacteriorhodopsin, a membrane protein that uses light to translocate protons. J Biol Chem. 1988 Jun 5;263(16):7439–7442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinetti T., Subramaniam S., Mogi T., Marti T., Khorana H. G. Replacement of aspartic residues 85, 96, 115, or 212 affects the quantum yield and kinetics of proton release and uptake by bacteriorhodopsin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989 Jan;86(2):529–533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.2.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogi T., Stern L. J., Hackett N. R., Khorana H. G. Bacteriorhodopsin mutants containing single tyrosine to phenylalanine substitutions are all active in proton translocation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987 Aug;84(16):5595–5599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.16.5595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogi T., Stern L. J., Marti T., Chao B. H., Khorana H. G. Aspartic acid substitutions affect proton translocation by bacteriorhodopsin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 Jun;85(12):4148–4152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.12.4148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ovchinnikov YuA Rhodopsin and bacteriorhodopsin: structure-function relationships. FEBS Lett. 1982 Nov 8;148(2):179–191. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(82)80805-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popot J. L., Gerchman S. E., Engelman D. M. Refolding of bacteriorhodopsin in lipid bilayers. A thermodynamically controlled two-stage process. J Mol Biol. 1987 Dec 20;198(4):655–676. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90208-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayfield G. W. Temperature dependence of photovoltages generated by bacteriorhodopsin. Biophys J. 1985 Jul;48(1):111–115. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(85)83764-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothschild K. J., Zagaeski M., Cantore W. A. Conformational changes of bacteriorhodopsin detected by Fourier transform infrared difference spectroscopy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1981 Nov 30;103(2):483–489. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(81)90478-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]