Abstract

Background

The genomic organization of Hox clusters is fundamental for the precise spatio-temporal regulation and the function of each Hox gene, and hence for correct embryo patterning. Multiple overlapping transcriptional units exist at the Hoxa5 locus reflecting the complexity of Hox clustering: a major form of 1.8 kb corresponding to the two characterized exons of the gene and polyadenylated RNA species of 5.0, 9.5 and 11.0 kb. This transcriptional intricacy raises the question of the involvement of the larger transcripts in Hox function and regulation.

Methodology/Principal Findings

We have undertaken the molecular characterization of the Hoxa5 larger transcripts. They initiate from two highly conserved distal promoters, one corresponding to the putative Hoxa6 promoter, and a second located nearby Hoxa7. Alternative splicing is also involved in the generation of the different transcripts. No functional polyadenylation sequence was found at the Hoxa6 locus and all larger transcripts use the polyadenylation site of the Hoxa5 gene. Some larger transcripts are potential Hoxa6/Hoxa5 bicistronic units. However, even though all transcripts could produce the genuine 270 a.a. HOXA5 protein, only the 1.8 kb form is translated into the protein, indicative of its essential role in Hoxa5 gene function. The Hoxa6 mutation disrupts the larger transcripts without major phenotypic impact on axial specification in their expression domain. However, Hoxa5-like skeletal anomalies are observed in Hoxa6 mutants and these defects can be explained by the loss of expression of the 1.8 kb transcript. Our data raise the possibility that the larger transcripts may be involved in Hoxa5 gene regulation.

Significance

Our observation that the Hoxa5 larger transcripts possess a developmentally-regulated expression combined to the increasing sum of data on the role of long noncoding RNAs in transcriptional regulation suggest that the Hoxa5 larger transcripts may participate in the control of Hox gene expression.

Introduction

Hox genes play a crucial role in specifying regional identity along the body axes and in regulating morphogenesis during animal development. Inappropriate expression and mutation of Hox genes can disrupt normal programs of growth and differentiation leading to malformations, tumor formation, and even death [1]. In mammals, 39 Hox genes are distributed over four clusters sharing a similar organization that reflects the relationship existing between the relative position of each Hox gene along the cluster, its expression domain in the embryo and its temporal onset. Hox genes have RNA expression domains extending from the caudal end of the embryo to a defined anterior limit. The resulting spatio-temporal profile of Hox gene expression during embryogenesis correlates with the arrangement of the clusters: the 3′ most genes being expressed earlier and in more anterior domains than the 5′ located ones [2]. Consequently, the clustered organization appears fundamental for the precise spatio-temporal regulation and the function of each Hox gene and hence for the correct patterning of the embryo.

How Hox gene expression is modulated along the developing axes still remains elusive. Our initial knowledge of the regulatory mechanisms governing Hox gene expression comes mostly from transgenic mice studies, which have shown that Hox dynamic expression patterns result from positional information transducing via transcription factors that interact with a combination of positive and negative cis-acting sequences to differentially control Hox gene expression in a spatio-temporal and tissue-specific fashion. However in most cases, only limited subsets of the proper spatial and temporal expression patterns are reconstituted by the transgenes. A likely explanation is the presence of complex and overlapping transcriptional units in Hox genes that implies dispersed regulatory regions in the clusters [3]–[5]. There is also evidence for the integrated regulation of neighboring Hox genes through the sharing, the competition and/or the selective use of defined cis-acting sequences [6]–[8]. Moreover, global enhancer sequences located outside the Hox clusters can coordinate the expression of several genes in a relatively promoter-unspecific manner [9]–[12]. Finally, large-scale chromatin remodeling events participate to the regulation of Hox loci [13], [14].

Hox RNAs and HOX proteins can colocalize, which reinforces the notion that transcriptional control is a primary mechanism for Hox gene regulation. However in some instances, HOX proteins are detected in a subdomain of the RNA pattern suggesting the existence of post-transcriptional control [8], [15]. The discovery of microRNAs that can mediate the targeted degradation of specific Hox transcripts has unveiled an additional level of regulation of Hox gene expression [16], [17]. In addition, antisense transcripts and long noncoding RNAs are found throughout Hox clusters and they are proposed to be part of the epigenetic regulation of Hox gene expression [18]–[22]. Altogether, these data indicate that a complex array of different modes of regulation is essential for the proper spatio-temporal Hox gene expression.

To fully understand the regulatory events governing Hox gene expression, we are using as a model the Hoxa5 gene. This gene plays a crucial role during embryogenesis as well as being involved in tumorigenesis [23]–[25]. In the developing embryo, Hoxa5 is expressed in the neural tube caudal to the posterior myelencephalon, in the axial skeleton up to the level of prevertebra (pv) 3 and in the mesenchymal component of several organs, including the trachea, the lung, the stomach, the intestine and the kidneys [26]–[31]. We have shown that the loss of Hoxa5 function in the mouse affects a well-defined subset of structures mainly located at the cervico-thoracic level [23], [26], [27], [32], [33]. Aside from morphological defects in foregut derivatives and mammary glands [26], [29], [34], [35], the targeted disruption of the Hoxa5 gene perturbs axial skeleton identity between pv3 and pv10, the anterior-most region of the Hoxa5 domain of expression along the prevertebral axis [23], [27].

Polyadenylated transcripts of 1.8, 5.0, 9.5 and 11.0 kb in length encompassing Hoxa5 coding sequences are produced in the embryo. They are also detected after birth in a tissue-specific fashion [23], [36]. The 1.8 kb transcript is the most abundant and it corresponds to the two characterized exons of the Hoxa5 gene [37]. It encodes the 270 amino acid (a.a.) HOXA5 protein. Previous RNAase protection assays have shown that the larger forms initiate more upstream from sequences that remain to be identified [37]. Differences in the expression profile of these different transcripts are also observed: the 1.8 kb transcript is expressed as early as embryonic day (e) 8.0–8.25, whereas the larger transcripts are first detected around e8.5–8.75 [32]. The larger transcripts are present in more posterior structures of the embryo with an anterior limit of expression in the pv column corresponding to pv10, while that of the 1.8 kb transcript is pv3. In the neural tube, a posterior shift was observed for the larger transcripts [32]. Similarities between the Hoxa7 expression profile and that of the larger transcripts indicate that they may share regulatory mechanisms [38].

The presence of multiple overlapping transcriptional units at the Hoxa5 locus suggests that Hoxa5 gene regulation may be complex. Using a transgenic approach, we have shown that several DNA control elements located both upstream and downstream the Hoxa5 coding sequences are involved in the expression of the 1.8 kb transcript [32], [39]–[41]. An intricate situation prevails as some of these regulatory sequences are shared with the flanking Hoxa4 gene, while others overlap with the Hoxa6 coding sequences [32], [39], [42]. The presence of larger transcripts encompassing the Hoxa5 coding sequences also implies that more DNA regions involved in Hoxa5 gene regulation may be distributed along the cluster.

To assess the importance of the Hoxa5 larger transcripts in Hoxa5 gene function and regulation and to eventually define how they integrate in the developmental program, we have undertaken their molecular characterization. Our data revealed the complex organization of the different transcriptional units encompassing the Hoxa5 and Hoxa6 loci. It results from the use of three specific promoters and alternative splicing. Even though all these transcripts can potentially produce the genuine 270 a.a. HOXA5 protein, only the 1.8 kb form appears to generate the protein. Furthermore, the Hoxa5 functional domain along the embryonic axis coincides with the expression region of the protein, where the larger transcripts are excluded. This pinpoints at the 1.8 kb form as the Hoxa5 functional transcript in regional specification and leaves opened a role for the larger transcripts as long noncoding RNAs.

Results

Molecular characterization of the Hoxa5 alternate transcripts

Previous northern analysis of polyA+ RNA from mouse embryo using a DNA probe corresponding to the 3′-untranslated region of the second exon of the Hoxa5 gene has shown that polyadenylated transcripts of approximately 1.8, 5.0, 9.5 and 11.0 kb in length contain sequences from the Hoxa5 locus [23]. The 1.8 kb transcript corresponds to the putative Hoxa5 transcript as demonstrated from cDNA sequence analyses [36], [37]. We thus aimed to determine the molecular origin of the larger transcripts. To do so, we applied a series of molecular approaches, and by merging all the data obtained from northern, 3′- and 5′-RACE, RT-PCR and cDNA analyses, we established a schematic representation of the major Hoxa5 transcripts produced in the e12.5 mouse embryo (Fig. 1).

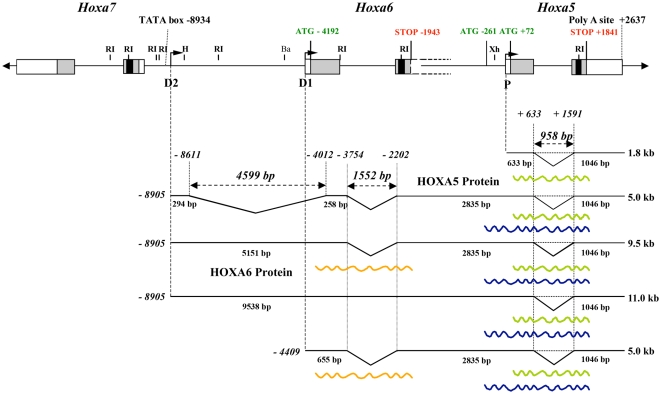

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the different transcripts encompassing Hoxa5 sequences in the e12.5 mouse embryo.

Genomic organization of the Hoxa5, Hoxa6 and Hoxa7 genes along the HoxA cluster. Black, grey and open boxes indicate homeobox, translated and transcribed sequences, respectively. The two known exons of Hoxa5 and the two in-frame ATG are represented. Position +1 corresponds to the transcription initiation site of Hoxa5 exon 1. The 3′ non-coding sequences of Hoxa6 exon 2 extend further downstream into the Hoxa6-Hoxa5 intergenic region and the adjacent Hoxa5 coding sequences and they are indicated by dotted lines. The ATG of the putative HOXA6 protein is indicated. The promoters driving expression of the different transcripts are shown: proximal promoter, P; distal promoters D1 and D2. The transcripts are represented underneath based on northern, 5′ RACE, 3′-RACE and RT-PCR assays used to define their molecular structure. Hoxa5 intron is represented by a dotted line to indicate the non-spliced isoforms. The longest ORFs deduced from the sequence of each transcript are represented by waved lines: the 270 a.a. HOXA5 protein, the 381 a.a. HOXA5 isoform and the HOXA6 protein. Ba, BamHI; H, HindIII; RI, EcoRI; Xh, XhoI.

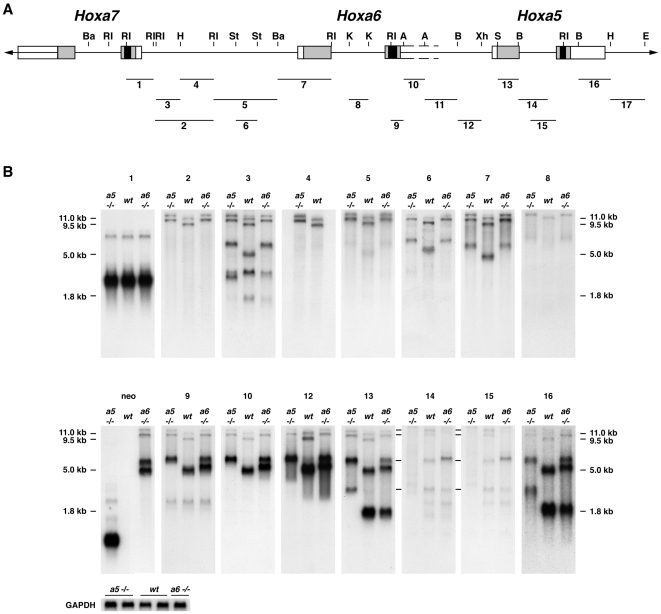

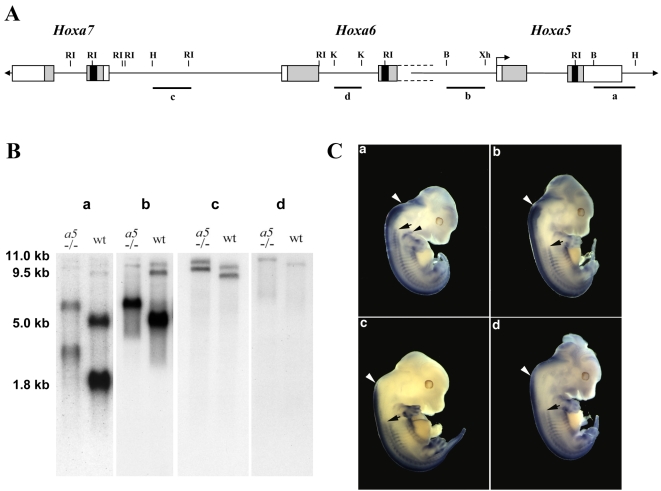

First, we performed northern analyses with e12.5 mouse embryo polyA+ RNA using as antisense riboprobes several genomic fragments encompassing Hoxa5 and flanking Hox genes (Fig. 2). The RNA was obtained from wild-type (wt), Hoxa5 −/− and Hoxa6 −/− embryos. We took advantage of the mutant forms of the Hoxa5 and Hoxa6 transcripts produced in Hoxa5 −/− and Hoxa6 −/− mice, respectively. These mutant transcripts are 1 kb larger than the endogenous ones due to the insertion of a 1 kb neo cassette into the homeobox sequence of each gene [23], [43], [44]. This difference in length allowed us to distinguish the alternate Hoxa5 transcripts among the several products detected. Northern analyses of polyA+ RNA from wt and Hoxa5 −/− embryos revealed that the 1.8, 5.0, 9.5 and 11.0 kb transcripts contained the two Hoxa5 exons and they were all affected by the insertion of the neo cassette into the Hoxa5 mutant allele as previously shown (probes 13 and 16; Fig. 2) [23]. Moreover, these sense transcripts were all transcribed from the same DNA strand. The 1.8 kb transcript corresponded to the two Hoxa5 exons. As shown by probes 2 to 12, the 5.0, 9.5 and 11.0 kb RNA species initiated in the Hoxa6-Hoxa7 intergenic region further upstream from the identified 1.8 kb transcript start site (position +1; Figs. 1 and 2) [37]. These larger transcripts contained the Hoxa6 sequences and they showed the expected shift in size in Hoxa6 −/− RNA due to the presence of the neo cassette [44]. A complex splicing pattern also prevailed explaining the difference in length between the 5.0, 9.5 and 11.0 kb transcripts. The Hoxa6 intron sequences were only detected in the 11.0 kb transcript (probe 8; Fig. 2), while some Hoxa6-Hoxa7 intergenic sequences did not hybridize to the 5.0 kb band (probes 2, 4 and 5; Fig. 2). Faint bands approximately 1 kb larger than the expected transcripts were also distinguished in the wt specimens with probes 14 and 15 that correspond to Hoxa5 intron sequences, suggesting that transcripts with unspliced Hoxa5 intron sequences may exist at low abundance (Fig. 2). Additional bands of about 2.5 kb in length were detected with the Hoxa6-Hoxa7 intergenic probe 3. Their origin was not investigated but they could correspond to RNA species initiating in the Hoxa6-Hoxa7 intergenic region that skip the Hoxa6 and Hoxa5 loci to continue further downstream in the Hoxa4-Hoxa5 sequence, like the GenBank mRNA AK051552, or extend towards the vicinity of the Hoxa3 gene, as the Y11717 mRNA (GenBank). Finally, all 1.8, 5.0, 9.5 and 11.0 kb transcripts ended at the same polyA site at the 3′ end of Hoxa5 exon 2 (position +2637) as revealed by 3′-RACE (Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends) experiments. This was also demonstrated by the lack of hybridization in northern analysis with a riboprobe located in genomic sequences 3′ to the Hoxa5 polyA site (Fig. 2; data not shown).

Figure 2. Molecular characterization of Hoxa5 transcripts by northern analysis.

(A) Genomic organization of the Hoxa5, Hoxa6 and Hoxa7 genes along the cluster. Black, grey and open boxes indicate homeobox, translated, and transcribed sequences, respectively. Probes used for northern analyses are indicated by numbered lines (1–17). (B) Northern analyses of polyA+ RNA from e12.5 wild-type, Hoxa5 −/− and Hoxa6 −/− mouse embryos were performed with probes covering the genomic region located between Hoxa5 and Hoxa7. The mutated form of the Hoxa5 transcripts produced in Hoxa5 −/− mice are 1 kb larger than the endogenous ones due to the insertion of the neo cassette into the homeobox sequence. A similar situation prevails for the Hoxa6 mutation where the insertion of the neo cassette in the Hoxa6 homeobox sequence also disrupts all transcripts encompassing the Hoxa5 and Hoxa6 loci, except the 1.8 kb form. The 5.0, 9.5 and 11.0 kb transcripts contain Hoxa5 exons 1 and 2 sequences but initiated further upstream of the known 1.8 kb transcript start site in the Hoxa6-Hoxa7 intergenic region. The difference in length between the 9.5 and 11.0 kb transcripts is due to the Hoxa6 intron sequences present only in the 11.0 kb transcrit (probe 8). All transcripts end at the same polyadenylation site at the 3′ end of Hoxa5 exon 2 since no hybridization was observed by northern analyses with probes covering more than 1 kb of genomic sequences 3′ to the Hoxa5 polyA site (probe 17; data not shown). The lines on the left of northern blots 14 and 15 indicate Hoxa5 non-spliced isoforms that are 1 kb larger. Gapdh was used as a loading control. A, AccI; B, BglII; Ba, BamHI; E, EagI; H, HindIII; K, KpnI; RI, EcoRI; S, SacI; St, StuI; Xh, XhoI.

To map the transcriptional start site of the larger Hoxa5 transcripts, we designed a 5′-RACE strategy based on the data obtained from the northern analyses. We used different sets of primers specific either to the 9.5 and 11.0 kb transcripts (primer 1) or located in sequences shared by the 5.0, 9.5 and 11.0 kb transcripts (primers 2 and 3; Fig. S1A). Clones obtained with primer 1 indicated that the 9.5 and 11.0 kb transcripts initiate in the Hoxa6-Hoxa7 intergenic region at position –8905 bp, which is about 2.3 kb downstream of the 3′-end of Hoxa7 gene. With primers 2 and 3, 5′-RACE products revealed the presence of a 4.6 kb intron and an initiation site coinciding with that of the largest transcripts at position –8905 bp. A second population of clones was also obtained with primer 2 with a transcription start site at position –4409 bp, which corresponds to the putative first base of Hoxa6 exon 1. Thus, two distal promoters, one related to the Hoxa6 gene (promoter D1) and a more distal one located dowstream the Hoxa7 gene (promoter D2), participate in the production of the Hoxa5 alternate transcripts (Fig. 1).

Finally to resolve the molecular structure of the different transcripts, we used various combinations of primers in RT-PCR experiments (Fig. S1B). Sequencing data of the clones obtained confirmed the importance of alternative splicing in the production of the various Hoxa5 transcripts and revealed other minor forms (clones pLJ282 and 284).

Figure 1 summarizes the molecular characterization of the different Hoxa5 transcripts and from this, several observations were made. First, the sequences between the Hoxa7 and the Hoxa5 genes can be entirely transcribed to give rise to the 11.0 kb transcript. Second, the 5.0 kb band detected by northern analyses included two main RNA species, one initiating at position –8905 bp, like the larger forms of 9.5 and 11.0 kb, and containing a large intron of 4.6 kb (identified as the 5 kb-Hoxa5 transcript), and a second starting at –4409 bp, from the putative Hoxa6 promoter (identified as the 5 kb-Hoxa6/a5 transcript). Third, no specific Hoxa6 transcript corresponding solely to the two known Hoxa6 exons was detected by northern analysis. Indeed, such signal was not observed with a probe including the putative Hoxa6 exon 1 sequences (probe 7; Fig. 2). A weak band of about 2.4 kb in length was seen with the Hoxa6 exon 2 probe containing part of the homeobox sequence (probe 9; Fig. 2). However, it could not correspond to a Hoxa6 transcript since it did not produce a mutant form 1 kb larger in the Hoxa6 −/− RNA sample. Sequence blast of probe 9 against the mouse genome revealed homologies with some Hox genes, the highest being 94% homology with the Hoxa7 homeobox sequence (data not shown). Since the 2.4 kb band matched the main transcript seen with probe 1, which included Hoxa7 homeobox sequence, it is likely that this faint band may result from the cross-hybridization of probe 9 with the major Hoxa7 transcript.

Our northern and 3′-RACE studies unveiled that all Hoxa5 transcripts use the polyA site of the Hoxa5 gene. Search for polyadenylation sequences at the Hoxa6 locus did not reveal the presence of a consensus site nearby the presumptive 3′-end of the Hoxa6 gene. Identified consensus motifs were either overlapping the end of the Hoxa6 homeobox sequence (position −2006 bp relative to the start site of the 1.8 kb transcript), or located further downstream in the Hoxa6-Hoxa5 intergenic region (positions −825 bp and −468 bp). The lack of a functional polyadenylation sequence at the Hoxa6 locus was further confirmed by the presence of a neo transcript in Hoxa6 −/− RNA sample of about 5.5 kb in length (probe neo; Fig. 2). This transcript initiated at the MC1 promoter of the MC1neo cassette, which does not contained a polyA addition signal [44]. Thus, transcription of the neo cassette must end at the nearest functional polyadenylation site, the latter being localized 3′ of the Hoxa5 gene. In summary, the use of different promoters and alternative splicing may account for the production of several transcriptional units containing sequences from both Hoxa5 and Hoxa6 loci.

Transcriptional activity in the Hoxa6-Hoxa7 intergenic region

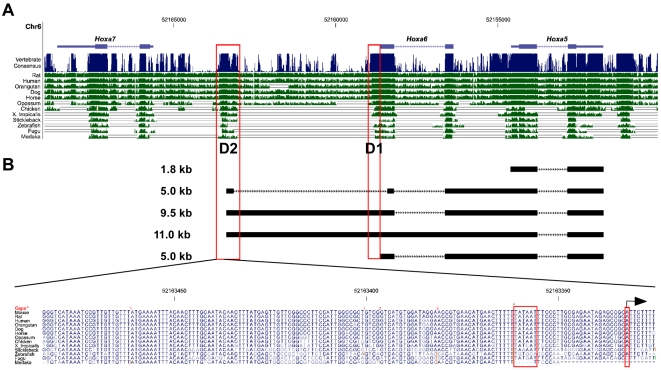

Our observation that the 5 kb-Hoxa5, 9.5 and 11.0 kb alternate transcripts initiated from a DNA region located downstream the Hoxa7 gene prompted us to define the transcriptional activity of the sequences encompassing the potential distal promoters D1 and D2. We first performed comparison of the sequences encompassing the Hoxa5, Hoxa6 and Hoxa7 loci between divergent vertebrate species using the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) Genome Browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/; Mouse July 2007 assembly) [45]. As expected, Hox exon sequences showed very high homology (Fig. 3). A ∼500 bp DNA region surrounding the transcription start site at position −8905 bp and the D2 promoter was also highly conserved among the species. Alignment of the nucleotide sequences indicated a DNA region of 160 bp, which includes a putative TATA box at position −8934 bp, very highly preserved, arguing for the presence of evolutionary conserved important regulatory DNA elements that may be involved in the production of the larger transcripts. Highly homologous sequences located just 5′ from Hoxa6 exon 1 and corresponding to the putative D1 promoter were also found.

Figure 3. Evolutionary conservation of the Hoxa5-Hoxa7 genomic region among animal species.

(A) The mouse sequence of the Hoxa5-Hoxa7 loci was compared to that of rat, human, orangutan, dog, horse, opossum, chicken, xenopus tropicalis, stickleback, zebrafish, fugu and medaka using the UCSC genome browser. The regions with vertical lines indicate conserved sequences. In addition to Hox exons, the DNA regions located upstream the Hoxa5 distal transcription start sites at positions −4409 bp (D1) and −8905 bp (D2) show high homology between divergent species (boxes), suggesting the presence of evolutionary conserved important regulatory DNA elements. (B) Alignment of the nucleotides of a 160-bp DNA fragment from the D2 region indicates the presence of a consensus TATA box and a transcription initiation site (boxes) in most species.

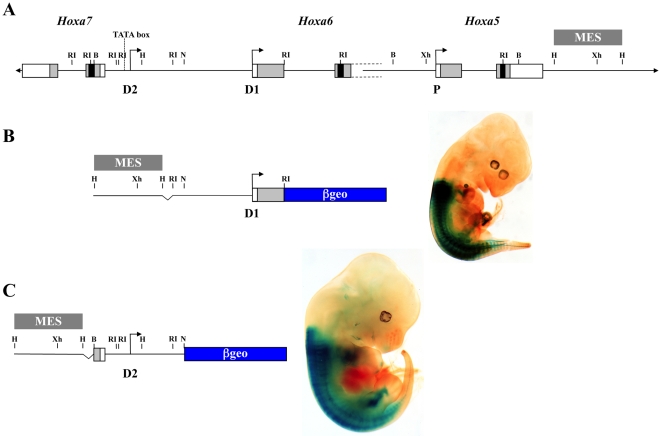

The transcriptional activity of the distal promoters D1 and D2 was directly assessed by transgenesis (Fig. 4). For each promoter, a ∼4 kb DNA fragment containing sequences flanking the transcription start site was fused to an IRES-βgeo cassette used as a reporter. A MES enhancer sequence, known to drive Hoxa5 regionalized expression along the embryonic axis, was added to each construct in order to improve the detection of a minimal promoter activity [32]. A Hox-like staining pattern was observed with the two transgenes indicating that the sequences upstream the distal transcription initiation sites D1 and D2 possess promoter activity.

Figure 4. Transcriptional activity of the D1 and D2 putative promoters in e12.5 transgenic embryos.

(A) A schematic representation of the Hoxa5, Hoxa6 and Hoxa7 genes along the HoxA cluster. The proximal promoter P and the two distal promoters D1 and D2 are indicated. (B) Detection of β-galactosidase activity in D1-lacZ transgenic embryos in presence of the mesodermal enhancer sequence (MES) indicates that the 4 kb-DNA region encompassing the putative Hoxa6 promoter (D1) can drive Hox-like expression along the antero-posterior axis. (C) As well, a 4 kb-DNA fragment containing the D2 putative promoter region of the larger transcripts possesses a similar transcriptional activity. B, BglII; H, HindIII; N, NruI; RI, EcoRI; Xh, XhoI.

Differential expression pattern of the Hoxa5 transcripts

Our previous studies have demonstrated that the 1.8 kb transcript is expressed earlier during embryogenesis and in more anterior structures than the larger transcripts [32]. To gain information on the potential function of the alternate transcripts during embryogenesis, we performed comparative whole-mount in situ hybridization analyses at e12.5. Since all transcripts included the two Hoxa5 exons corresponding to the 1.8 kb transcript and shared most of their sequences, we used probes that recognize either all transcripts or combinations of the larger forms. As shown on figure 5A and B, probe “a” contains Hoxa5 exon 2 sequences common to all transcripts; probe “b” corresponds to the Hoxa5-Hoxa6 intergenic region recognizing the 5.0, 9.5 and 11.0 kb forms; probe “c” is localized in the Hoxa6-Hoxa7 intergenic region and detects the 9.5 and 11.0 kb transcripts; and probe “d” includes Hoxa6 intron sequences hybridizing only to the 11.0 kb transcript. The expression profile detected with probe “a”, but not with probes “b”, “c” and “d”, revealed structures that exclusively express the 1.8 kb transcript (Fig. 5C). In the pv column, the anterior limit of expression of the 1.8 kb transcript corresponded to pv3, while the 5.0, 9.5 and 11.0 transcripts shared the same boundary at pv10. In the neural tube, a posterior shift was observed for the larger transcripts, and the shift was more caudal with probes “c” and “d”. In the future pectoral girdle, hybridization signal was detected only with probe “a”. Previous in situ hybridization experiments on e12.5 embryo sections have shown a strong expression with probe “a” in the mesenchymal component along the entire respiratory tract while probe “b” produced a weak signal restricted to the distal tip of the lungs [26], [27]. Similarly, hybridization in the thyroid gland region was observed only with probe “a” (data not shown) [35]. In the developing gastrointestinal tract, a dynamic Hoxa5 expression pattern prevails. Probe “a” detected expression in the gut mesenchyme as early as e9.0, while the onset of expression with probe “b” was delayed to e12.5 in the foregut, and e10.5 in the midgut [28], [29]. In the hindgut, expression of the larger transcripts was detected as early as e9.5 indicating that they shared the same onset as the 1.8 kb transcript (Fig. S2). After e12.5, the expression profile in the developing stomach was similar for probes “a” and “b” with a widespread distribution throughout the gastric mesenchyme until e17.5, followed by restriction to the submucosa and muscular layers and extinction at postnatal day 15 (data not shown) [29]. In the mid- and hindgut, expression was detected with both probes in the mesenchyme up to e14.5 and e17.5, respectively. Expression of the larger transcripts then extinguished in the midgut and the hindgut, while that of the 1.8 kb transcript got restricted to the enteric nervous system and was maintained after birth (Fig. S2) [28].

Figure 5. Differential expression pattern of Hoxa5 transcripts.

(A) Genomic organization of the Hoxa5, Hoxa6 and Hoxa7 genes along the cluster. Probes a, b, c and d used for northern blot analyses and whole-mount in situ hybridization are indicated below. (B) Northern blots of polyA+ RNA extracted from e12.5 wild-type and Hoxa5 −/− embryos were hybridized with each probe. (C) Whole-mount in situ hybridization of e12.5 wild-type embryos with probes a-d. Anterior limits of expression are indicated for the neural tube (white arrowheads) and the prevertebral column (black arrows). The different profiles reveal the specific expression of the transcripts: probe a allows to identify the structures that exclusively express the 1.8 kb transcript. Theses structures include the pv3-pv10 axial domain and the pectoral girdle (black arrowhead). The larger transcripts are expressed in more posterior structures than the 1.8 kb transcript. B, BglII; H, HindIII; K, KpnI; RI, EcoRI; Xh, XhoI.

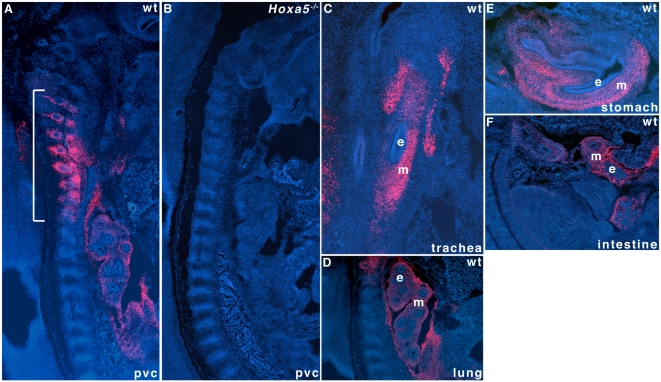

The differential expression of the transcripts encompassing Hoxa5 sequences along the antero-posterior axis of the skeleton and the rostro-caudal axis of the developing gut reflects the organization of the different promoters (P, D1 and D2) along the cluster and respects the relationship of colinearity characterizing the Hox complexes. It also raises questions about the role played by each of these transcripts during development. Even though the Hoxa5 mutation perturbs all Hoxa5 transcripts, most of the defects observed in the Hoxa5 −/− mutant mice are confined to the cervico-thoracic region and they affect structures and organs that solely express the 1.8 kb transcript. Using a HOXA5-specific antibody, we looked at the HOXA5 protein distribution in the e12.5 mouse embryo [46]. HOXA5 immunoreactivity was observed along the pv column in the pv3-pv10 region and in the mesenchyme of the trachea, lung, stomach and intestine (Fig. 6A, C–F). No immunostaining was detected in Hoxa5 −/− specimens (Fig. 6B). Except for the gastrointestinal tract where all Hoxa5 transcripts were detected (Fig. S2), the expression seen in the pv column and the respiratory tract matched that of the 1.8 kb transcript, raising the possibility that only the 1.8 kb transcript produces the HOXA5 protein.

Figure 6. Restricted spatial distribution of HOXA5 protein along the antero-posterior axis and in the respiratory and digestive tracts.

HOXA5 immunoreactivity is detected in the pv3-pv10 region of the prevertebral column (pvc) of e12.5 wild-type mouse embryos by immunofluorescence (bracket; A). No immunoreactivity is seen in the Hoxa5 −/− specimens confirming the absence of the protein in the null mutant mouse line (B). HOXA5 is also detected in the mesenchymal component of the trachea (C), lung (D), stomach (E) and intestine (F) of e12.5 mouse embryo. e, epithelium; m, mesenchyme.

Translational capability of the Hoxa5 transcripts

There are multiple ORFs predicted from the sequence of the different Hoxa5 transcripts and the longest ones are represented in figure 1. All Hoxa5 transcripts include the HOXA5 ORF suggesting that they can potentially produce the genuine 270 a.a. HOXA5 protein. Sequence analysis also revealed the presence of a distal in-frame ATG codon located 333 nucleotides upstream of the proximal promoter (P; Fig. 1) that can produce a larger HOXA5 isoform of 381 a.a. Moreover, a HOXA6 protein of 232 a.a. can potentially be translated from the 5 kb-Hoxa6/a5 and the 9.5 kb transcripts, raising the possibility of bicistronic transcriptional units.

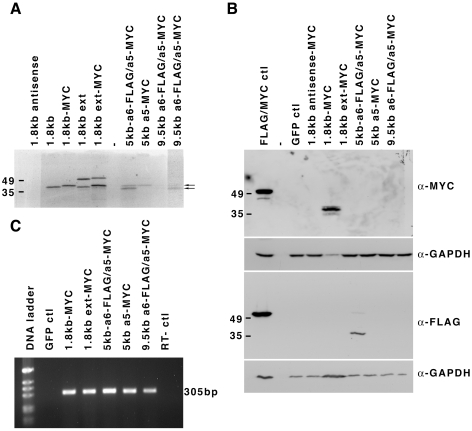

To define the capacity of the larger transcripts to produce the HOXA5 protein, we made expression vectors containing the entire 5 kb-Hoxa5, 5 kb-Hoxa6/a5 or 9.5 kb cDNA sequence with a MYC tag at the carboxy terminus of the HOXA5 protein. We also added a FLAG tag at the carboxy terminus of the HOXA6 protein for the 5 kb-Hoxa6/a5 and 9.5 kb cDNA vectors. As a control, we used a MYC-tagged version of the 1.8 kb cDNA. In addition, we made a vector containing an extended version of the 1.8 kb transcript (up to position -555 relative to the start site of the 1.8 kb transcript) that includes the distal ATG codon. The plasmids were first tested in vitro using a coupled transcription/translation assay with incorporation of radio-labeled methionine (Fig. 7A). As expected, vectors containing the 1.8 kb cDNA sequence with or without the MYC tag produced radioactive products of about 38 kD in size, slightly larger for the vector carrying the MYC tag and which corresponded to the 270 a.a. HOXA5 protein. For the extended version of the 1.8 kb transcript, the 38 kD HOXA5 protein was produced as well as a protein of about 50 kD, compatible to the 381 a.a. isoform. For the vector carrying the 5 kb-Hoxa5 cDNA, the HOXA5-MYC isoform of 270 a.a. was the unique band observed. In the case of the vector containing the 5 kb-Hoxa6/a5 cDNA sequence, the 270 a.a. HOXA5-MYC protein was detected as well as a smaller protein of about 36 kD, likely corresponding to the HOXA6-FLAG protein. Similar observations were made for the 9.5 kb cDNA, even though the two bands were faint. No band related to the larger HOXA5 isoform was detected with the 5 kb-Hoxa5, the 5 kb-Hoxa6/a5 and the 9.5 kb cDNAs. Thus when tested in vitro, all vectors can produce the genuine HOXA5 protein. The 5 kb-Hoxa6/a5 and 9.5 kb transcripts can also generate the HOXA6 protein, acting as bicistronic units.

Figure 7. HOXA5 protein production from Hoxa5 transcripts.

(A) Expression vectors carrying cDNAs corresponding to the 1.8 kb (with and without a MYC-tag), the extended 1.8 kb (MYC-tagged and non-tagged), the 5.0 kb-Hoxa6-FLAG/a5-MYC, the 5.0 kb-Hoxa5-MYC and the 9.5 kb Hoxa6-FLAG/a5-MYC transcripts were tested in vitro using a coupled transcription/translation system. A [S35]-radiolabeled protein corresponding to a ∼38 kD genuine HOXA5 protein is translated from all vectors. The larger HOXA5 isoform of ∼50 kD is only translated from the extended 1.8 kb cDNA version. The 5.0 kb-Hoxa6-FLAG/a5-MYC and the 9.5 kb Hoxa6-FLAG/a5-MYC vectors also produce a ∼36 kD band likely corresponding to the putative HOXA6 protein. Translation of the HOXA5 and HOXA6 proteins from the 9.5 kb Hoxa6-FLAG/a5-MYC vector is weakly detected and a longer exposure is shown with arrows to indicate the position of both proteins. (B) The HEK293 cells were transfected with the MYC-tagged version of the 1.8 kb and extended 1.8 kb expression vectors and with the 5.0 kb-Hoxa6-FLAG/a5-MYC, the 5.0 kb-Hoxa5-MYC and the 9.5 kb Hoxa6-FLAG/a5-MYC vectors. In parallel, control plasmids expressing either the green fluorescent protein (GFP ctl), the 1.8 kb Hoxa5-MYC in the antisense orientation or the pMEK1-MYC-FLAG plasmid (MYC/FLAG ctl) were transfected. Protein lysates were western-blotted with anti-MYC or anti-FLAG antibodies. Solely the 1.8 kb-MYC vector produces a genuine HOXA5 protein whereas the HOXA6 protein is only detected with the 5.0 kb-Hoxa6-FLAG/a5-MYC plasmid. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (C) RNA expression of each expression vector transfected in HEK293 cells was tested by RT-PCR. A 305 bp fragment is observed in RNA samples from HEK293 cells transfected with the Hoxa5 cDNA vectors. No expression is detected in the GFP ctl specimen.

Transfection assays in HEK293 cells followed by western analyses with the MYC or FLAG antibodies showed that only the 1.8 kb-MYC vector produces the 270 a.a. HOXA5-MYC protein (Fig. 7B). The HOXA5-MYC isoform of 381 a.a. was neither produced from the extended version of the 1.8 kb transcript nor from the 5 kb-Hoxa5, the 5 kb-Hoxa6/a5 and the 9.5 kb vectors. Moreover, only the 5 kb-Hoxa6/a5 vector produced the HOXA6-FLAG protein of 232 a.a. As verified by RT-PCR analysis, all Hoxa5 cDNA expression vectors were transcribed in HEK293 cells (Fig. 7C). In summary, all Hoxa5 transcripts can be efficiently translated in in vitro assays. However in cell cultures, only the 1.8 kb transcript can encode the 270 a.a. HOXA5 protein and the HOXA6 protein can solely be produced from the 5 kb-Hoxa6/a5 transcript.

Skeletal transformations in Hoxa6 and Hoxa5; Hoxa6 transheterozygous mutant mice

The Hoxa6 mutant mouse line provides a valuable tool for investigating the role of the larger Hoxa5 transcripts since the insertion of the MC1neo cassette into the Hoxa6 homeobox sequences disrupts the 5.0, 9.5 and 11.0 RNA species encompassing the Hoxa5 and Hoxa6 loci (Fig. 2). The Hoxa6 mutation causes a relatively mild phenotype, which consists in the presence of ectopic ribs on the 7th cervical vertebra (C7) in less than half of the mutants [44]. One puzzling aspect of the Hoxa6 −/− phenotype is that it is incompatible with the pv10 anterior expression boundary of the gene, as established by the expression analysis using probes specific for the larger transcripts (Fig. 5C). Two possibilities could account for this discrepancy. The integrity of the larger transcripts including Hoxa6 sequences is necessary for the correct patterning at the pv7 axial level. Alternatively, the presence of the neo cassette in the Hoxa6 locus may interfere with the expression of the nearby Hoxa5 gene, which then can impact on the skeletal phenotype. Ectopic ribs on C7 are a hallmark of the Hoxa5 mutation, as they are found in most Hoxa5 mutants [23], [27]. Moreover, transcriptional interference is not unusual in Hox mutations, and we have previously reported the deleterious long-range cis effect of the Hoxa4 mutation on Hoxa5 expression [27]. To discriminate between these options and to define the respective role of the Hoxa5 and Hoxa6 genes in the specification of the cervico-upper thoracic region, we generated Hoxa5; Hoxa6 transheterozygous animals (Hoxa5 +/−; Hoxa6 −/+), which are heterozygotes for both genes on different chromosomes. First, we examined the skeleton of new cohorts of single mutants and transheterozygous newborn pups (Table 1). In this mixed genetic background, Hoxa5 −/− mutants displayed the skeletal transformations previously reported: the lack of tuberculum anterior on C6 in 84% of the specimens analyzed; the presence of ectopic ribs on C7 (87%), most being present on both sides of the vertebra; abnormal acromion (42%) and fused tracheal rings (100%). Hoxa5 +/− pups also presented the C7 homeotic transformation at a lesser frequency (57%) than the Hoxa5 −/− mutants, but with a much higher incidence than the Hoxa6 −/− mutants (35%; Table 1). Ectopic ribs on C7 were observed in 58% of the Hoxa5 +/−; Hoxa6 −/+ pups analyzed, a frequency similar to that of Hoxa5 +/− mutants, suggesting that the Hoxa6 contribution to the C7 skeletal specification was weak.

Table 1. Newborn skeletal morphology according to the Hoxa5 and Hoxa6 genotypes.

| Genotype | ||||||

| wt | Hoxa5 +/− Hoxa6 +/+ | Hoxa5 −/− Hoxa6 +/+ | Hoxa5 +/−Hoxa6−/+ | Hoxa5 +/+ Hoxa6 +/− | Hoxa5 +/+ Hoxa6 −/− | |

| Tuberculum anterior on C6 a | ||||||

| Absent | - | - | 32 | - | - | - |

| Present | 14 | 44 | 6 | 38 | 20 | 26 |

| Ribs on C7a | ||||||

| Absent | 12 | 16 | 5 | 16 | 7 | 17 |

| Present | 2 | 28 | 33 | 22 | 13 | 9 |

| Unilateral | - | 6 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 5 |

| Bilateral | 1 | 11 | 15 | 8 | 6 | 2 |

| Acromiona | ||||||

| Normal | 14 | 44 | 22 | 38 | 19 | 26 |

| Abnormal | - | - | 16 | - | 1 | - |

| Trachea | ||||||

| Normal | 7 | 22 | - | 19 | 10 | 13 |

| Abnormal | - | - | 19 | - | - | - |

| Number of animals | 7 | 22 | 19 | 19 | 10 | 13 |

left and right sides were scored independently.

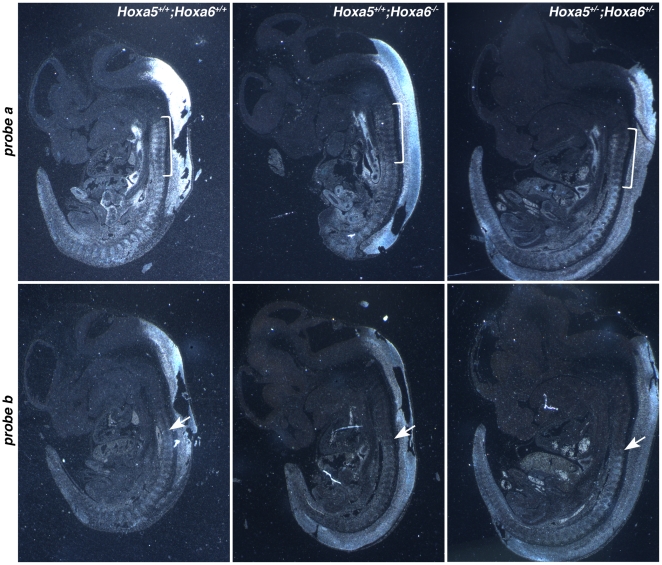

We also monitored Hoxa5 expression in Hoxa6 −/− and Hoxa5 +/−; Hoxa6 +/− e12.5 embryos by in situ hybridization using the riboprobes “a” and “b” described above (Figs. 5A and 8). The signal detected with probe “a” was specifically less intense in the pv3-pv10 region of the pv column from Hoxa6 −/− and Hoxa5 +/−; Hoxa6 +/− embryos when compared to wt specimens. No change in expression was observed with probe “b”. Thus, the disruption of the large transcripts by the Hoxa6 mutation does not have a major impact on axial specification as no skeletal anomaly was seen for the vertebrae localized caudally of pv10. Moreover, the Hoxa6 mutation alters expression of the 1.8 kb transcript in the pv3-pv10 region. One possible explanation may be that the insertion of the neo cassette into the Hoxa6 locus impairs the activity of the Hoxa5 proximal promoter, which consequently alters the specification of the C7 vertebra. On the other hand, the larger transcripts may also be involved in the regulation of the Hoxa5 proximal promoter by a mechanism that remains to be defined and their disruption by the Hoxa6 mutation may affect the expression of the 1.8 kb transcript, that in turn impacts on skeletal patterning in the cervico-thoracic region.

Figure 8. Comparative expression patterns of Hoxa5 transcripts in e12.5 wild-type, Hoxa6 homozygous and Hoxa5; Hoxa6 transheterozygous mutants.

In situ hybridization experiments were performed on comparable sagittal sections. Representative specimens are shown. Genotype is indicated on the top right of each column and probe on the left of each row. The bracket indicates the pv3-pv10 domain, which hybridizes with probe a in wild-type specimens, but not with probe b. In Hoxa6 −/− and Hoxa5 +/−; Hoxa6 −/+ mutants, the signal in this region is significantly decreased with probe a. With probe b, the anterior limit of expression corresponds to pv10 in all samples regardless of the genotype (arrows) with no major change in signal intensity.

Discussion

Multiple transcriptional units are present at the Hoxa5 locus

This study aimed at characterizing the different transcriptional units encompassing the Hoxa5 locus. Presence of multiple transcripts is not unique to the Hoxa5 gene. Other Hox genes have been reported to produce several RNAs and in few cases, the molecular nature of these transcripts has been analyzed [4], [5], [47], [48]. In the case of the Hoxa5, Hoxd4 and Hoxb3 genes, the additional transcripts are expressed according to a Hox-like pattern but they have distinct boundaries of expression. Their generation involves multiple promoters, alternative splicing and/or the use of different polyadenylation sites. We have identified three promoters for the Hoxa5 transcripts. The proximal one corresponds to the genuine Hoxa5 promoter driving expression of the major 1.8 kb transcript. The larger transcripts are generated from either the distal D1 promoter, which is in fact the putative Hoxa6 promoter, or the D2 promoter located downstream the 3′ extremity of the Hoxa7 gene. Alternative splicing is also an important process contributing to the diversity of Hoxa5 transcripts. Furthermore, the Hoxa5 intron is not rigorously spliced in a small proportion of all Hoxa5 transcripts adding to the number of RNA species detected. In contrast, the Hoxa6 intron is systematically spliced in all transcripts that include the Hoxa6 locus with the exception of the 11.0 kb form, which retains the intron sequences. Finally, only one polyadenylation site located at the end of the Hoxa5 locus is utilized by all transcripts encompassing the Hoxa5 and Hoxa6 sequences. This data reveals the lack of a functional polyadenylation site at the Hoxa6 locus. Thus in the e12.5 mouse embryo, the Hoxa6 transcript exists only as a bicistronic gene product that can potentially generate two HOX proteins, HOXA5 and HOXA6.

Several studies have revealed the high transcriptional activity occurring along the mammalian Hox clusters [19]–[22]. Many of these transcriptional units are antisense to Hox genes. They are highly conserved between mouse and human, and some are polycistronic. For the HoxA cluster, a search with the UCSC genome browser indicates the existence of numerous sense and antisense transcripts covering the mouse Hoxa5-Hoxa7 genomic region. Except for the Hoxa5 1.8 kb transcript, none of the larger transcripts characterized in the present work have been reported in databanks. However, portions of some of the transcripts listed include sequences of the Hoxa5 larger forms. For instance, the first exon of the GenBank mRNA AK051552 corresponds exactly to the 5kb-Hoxa5 transcript first exon. Twelve kb downstream in the Hoxa4-Hoxa5 intergenic region, the second exon of the AK051552 transcript encompasses sequences corresponding to a distal Hoxa3 exon annotated as the Hoxa3 Y11717 mRNA (GenBank). The latter also initiates within the first exon of the 5 kb-Hoxa5 transcript. In fact, the portrait of the different RNA species initiating in the Hoxa6-Hoxa7 intergenic region reveals extensive transcription and production of large transcripts starting in the D2 promoter region and extending towards the vicinity of the Hoxa3 gene. These data combined to ours argue for an intricate transcriptional activity at the D2 promoter. Interestingly, the integration of the Mouse Moloney Leukemia Virus (MMLV) nearby the D2 promoter in the Hoxa6-Hoxa7 intergenic sequence impacts dramatically on the expression of the Hoxa3 to Hoxa10 genes [49]. Even though we cannot rule out the possibility of a long-distance perturbing effect from the MMLV enhancer on the HoxA promoters, it is tempting to speculate that the MMLV insertion predominantly affects the D2 promoter activity revealing the important role of the latter in the control of a subset of HoxA genes.

Production of the HOXA5 and HOXA6 proteins

In in vitro assays, all the cDNAs corresponding to the larger Hoxa5 RNA species tested can produce the 270 a.a. HOXA5 protein but not the 381 a.a. isoform initiating at the distal ATG (Fig. 1). However in HEK293 cultured cells, only the 1.8 kb transcript can be translated into the genuine HOXA5 protein. Moreover, expression of the HOXA5 protein along the mouse embryonic axis was not detected caudally of pv10, the anterior boundary of the expression domain of the larger transcripts. The concordance between the Hoxa5 mutant phenotype and the expression domains of the HOXA5 protein and the 1.8 kb transcript support the notion that the 1.8 kb RNA is the functional Hoxa5 transcript.

In the case of the HOXA6 protein, the bicistronic 5 kb-Hoxa6/a5 and 9.5 transcripts generate both HOXA5 and HOXA6 proteins in vitro but only the 5 kb-Hoxa6/a5 cDNA produces the HOXA6 protein in cultured cells. Whether the 5 kb-Hoxa6/a5 transcript can generate the HOXA6 protein in the embryo remains to be defined via the development of a specific antibody. The absence of HOXA5 protein from the bicistronic 5 kb-Hoxa6/a5 unit is in accordance with the previous observations that polycistronic translation is a rare phenomenon in eukaryotes. In the case of polycistronic transcripts, the 5′ proximal cistron is usually the translated one as observed here [50]. Polycistronic transcription is not unusual in Hox clusters [19]. For instance, the Hoxc4, -c5 and -c6 genes are transcribed from a common promoter producing a primary transcript alternatively spliced to produce mature messengers encoding different proteins [51]. Finally, the presence of long 5′ untranslated region (UTR) sequences in the 5 kb-Hoxa5 and 9.5 kb transcripts can explain the absence of translation as it can greatly reduce translational efficiency [50]. Thus, the molecular characterization of the different Hoxa5 RNA species has unveiled an unexpected transcriptional organization and the promiscuity between the Hoxa5 and Hoxa6 loci in protein production.

Role of the Hoxa6 locus

Our studies raise questions about the role of the Hoxa6 gene during development. Interestingly in teleosts, the Hoxa6 gene is not present, most likely lost during the duplication process [52]. In mice, the Hoxa6 mutation results in a mild skeletal phenotype resembling that of the Hoxa5 mutants and occurring at an axial level located outside the Hoxa6 expression domain. Indeed, the Hoxa6 phenotype can be attributed to transcriptional interference that hinders transcription from the Hoxa5 proximal promoter. In fact, the neo cassette used to mutate the Hoxa6 gene was inserted in a temporal regulatory sequence responsible for the correct onset of Hoxa5 expression supporting the notion that the presence of exogenous sequences nearby control regions impact on their efficiency [32], [44]. We cannot rule out the possible implication of the larger transcripts in the regulation of the Hoxa5 proximal promoter and the effect their disruption by the Hoxa6 mutation may have. To directly address this possibility would require the specific abolition of the larger transcripts in mice and the analysis of the phenotypic and molecular consequences. Taken together, our data suggest that it seems unlikely that the Hoxa6 gene plays a role in axial specification, although it may serve other functions yet to be defined.

Functional role of the Hoxa5 1.8 kb transcript

Along the antero-posterior axis, the HOXA5 protein is detected in the most-rostral subdomain of expression of the Hoxa5 gene, which corresponds to the exclusive axial expression domain of the 1.8 kb transcript. In Hoxa5 mutant mice, most of the defects observed lie within the HOXA5 protein expression domain. This further supports the importance of the 1.8 kb transcript as the biological effector of the Hoxa5 gene during development.

Restricted HOX proteins expression was also reported for the Hoxb4 and Hoxb5 genes, and in both cases, the proteins were similarly localized in the anterior part of the gene expression domain [8], [15]. Comparatively to the RNA distribution, vertebrate HOX proteins may be more confined to precise axial levels, a situation comparable to what is observed for homeotic proteins in Drosophila embryos. Lots of efforts have been put on the regulatory mechanisms establishing the anterior boundary of Hox expression domains in vertebrates. Our findings enlighten the relevance of examining in more details how posterior boundaries may be fixed along the embryonic axes as well.

Implication of the Hoxa5 long noncoding RNAs

In e12.5 mouse embryo, the different polyA+ transcripts covering the Hoxa5 coding sequences reported in this study originate from the DNA coding strand. Moreover, the larger transcripts have similar Hox-like expression profiles. They are expressed later during embryogenesis and in more posterior structures than the 1.8 kb transcript. Similarities between the expression profile of the larger transcripts and that of the Hoxa7 gene indicate that they may share regulatory elements [38]. These long and interspersed transcripts also imply that DNA regions involved in Hoxa5 gene regulation may be distributed along the cluster and emphasize the importance of the Hox cluster organization for the correct expression of Hox genes.

The larger Hoxa5 transcripts cannot generate the HOXA5 protein. However, the 5 kb-Hoxa6/a5 transcript can produce the HOXA6 protein in HEK293 cells. Thus, the 5kb-Hoxa5, the 9.5 and the 11.0 kb transcripts, all transcribed from the distal D2 promoter, can be considered as long noncoding RNAs. Both Hoxa5 and Hoxa6 null mutations disrupt the 5.0, 9.5 and 11.0 kb transcripts without any phenotypic consequence in the domain where they are expressed. These two mutations do not preclude the transcription of the transcripts but produce mutant versions 1 kb larger due to the presence of a neo cassette in each mutated locus. Thus, disruption of the larger transcripts does not impact on axial specification. Transcription of intergenic regions or upstream promoter sequences can affect the expression of adjacent genes, either by producing transcriptional interference, promoter competition for a limiting factor or by altering chromatin structure, leading to the hypothesis that the act of transcription per se of long noncoding RNAs is responsible for the regulatory effect [53]. Alternatively, long noncoding RNAs may regulate in trans gene expression as shown for HOTAIR, which participates to the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 [20]. Our results in conjunction with the increasing sum of data on the potential role of long noncoding RNAs in transcriptional regulation now raise the following questions: do the Hoxa5 larger transcripts represent “transcriptional noise” or do they contribute by themselves to the control of Hox gene expression [54].

New genome-wide technologies have unveiled the complex architecture of the eukaryotic transcriptome. The extensive overlap between transcriptional units, the existence of non-co-linear transcripts and the multifunctional roles of genomic sequences have even led to a re-evaluation of the current concept of the nature of the gene [55]–[57]. In this context and due to the fact that several of these features occur in Hox clusters, the latter appear as a paradigm from which we may learn more about the link existing between transcriptional complexity, functionality and genome organization.

Materials and Methods

Mouse strains and genotyping

The establishment of the Hoxa5 mutant mouse line in the MF1-129/SvEv-C57BL/6 mixed background and the genotype by Southern analysis has been previously reported [23]. The Hoxa6 mouse line in the 129/SvEv-C57BL/6 genetic background was provided by Dr. Mario Capecchi and genotyped by Southern blot analysis as described [44].

Hoxa5 mutant mice were intercrossed with Hoxa6 mutant mice to produce transheterozygous animals (Hoxa5 +/−; Hoxa6 −/+). For genetic background homogeneity, transheterozygous animals were interbred to generate mice carrying the possible Hoxa5; Hoxa6 allelic combinations for subsequent skeletal analyses.

Embryonic age was estimated by considering the morning of the day of the vaginal plug as e0.5. All experiments were performed according to the guidelines of the Canadian Council on Animal Care and approved by the institutional animal care committee (Comité de Protection des Animaux du Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Québec, CPA-CHUQ).

PolyA+ RNA isolation and northern analysis

Total RNA from wild-type, Hoxa5 −/− and Hoxa6 −/− e12.5 embryos was isolated according to the TRIzol RNA extraction protocol (Invitrogen). For polyA+ RNA, the extraction was followed by two-step chromatography on oligo(dT)-cellulose column [58]. Seven µg of each polyA+ RNA preparation were used for northern analysis. Several genomic fragments covering the HoxA locus from Hoxa7 to Hoxa5 were used for antisense riboprobe synthesis (Fig. 2A). Hybridization to a GAPDH probe for quality control and quantitation was performed in parallel.

5′-Rapid Amplification of cDNA ends (RACE), 3′-RACE and RT-PCR analyses

The 5′ RACE protocol was essentially based on that described in [59]. The first-strand cDNA synthesis was performed with one µg of total RNA from e12.5 wild-type mouse embryos annealed to antisense Hox primer 1 (5′-GCGACCCTGCTATTGCCCAGACA-3′), primer 2 (5′-CTTCCGGTCGGTGCCTTCCTCAT-3′) or primer 3 (5′-CTGCGGGAGAAGCAGGCTGGAAT-5′; Fig. S1A). A polyA tail was added to the cDNAs. The dA-tailed cDNAs were first amplified using the nested Hox primer 1′ (5′-AACACAGCAGCCCCTGCACGGAA-3′), primer 2′ (5′-CTGCACGCTGCCGTCAGGTTTGT-3′) or primer 3′ (5′-GGCACCAGGGGGCAAAGCCAATA-3′) with an anchor primer complementary to the added oligo(dA) tail (5′-CCAGTGAGCAGAGTGACGAGGACTCGAGCTCAAGCTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT-3′) and an adapter primer included into the anchor primer (5′-CCAGTGAGCAGAGTGACGAGGAC-3′). A second round of amplification was set up with the primary PCR products and a different set of nested primers: primer 1″ (5′-CCCTCTTCCAGGGCTCAGGAA-3′), primer 2″ (5′-AAATGCGGCCGCCTGCTGCTCGGGAGAAAAGTG-3′) or primer 3″ (5′-AAATGCGGCCGCGGTCCCTGCACTGGGTCTAC-3′) with the anchoring primer (5′-GACGAGGACTCGAGCTCAAGC-3′). The secondary PCR products were subcloned prior to sequencing.

The 3′ RACE System for Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends (GIBCO BRL) was used to identify the 3′ extremity of the Hoxa5 transcripts. One µg of polyA+ RNA from e12.5 wild-type mouse embryos was used for the first-strand cDNA synthesis with a polyT adapter primer (5′-CCATCGATGTCGACTCGAGTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT-3′) according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer. PCR amplification was then performed using a Hoxa5 specific primer (5′-CTCCCCTTGTGTTCCTTCTG-3′) and a nested adapter primer (5′-CCATCGATGTCGACTCGAGT-3′) on an aliquot of the first-strand synthesis reaction. The resulting amplified products were subcloned and sequenced.

For the RT-PCR reactions, one µg of total RNA from e12.5 wild-type mouse embryos was used for the first-strand cDNA synthesis after annealing to an oligo(dT) primer or to the specific Hox primers 2 and 3 (described above). The following PCR reactions were then performed using various combinations of sense and antisense primers that all contain a NotI site. The sense primers are: primer 4 (5′-ATATGCGGCCGCCTCCGCTCCATCCTGCGTGCTT-3′), primer 5 (5′-AAATGCGGCCGCATCACAGTCCTGCAGAGGGGC-3′), and primer 6 (5′-AAATGCGGCCGCCACAAACGACCGCGAGCCACA-3′). The antisense primers are: primer 7 (5′-AAATGCGGCCGCCCCGGCGAGGATACAGAGGAT-3′) and primer 8 (5′-AAATGCGGCCGCACAGAGAGCTGCCCGGCTACT-3′). The RT-PCR products were then digested with NotI, subcloned and sequenced.

Construction of Hox/lacZ transgenes and production of transgenic embryos

Genomic fragments encompassing the putative D1 and D2 promoter regions were subcloned in front of the IRES-βgeo cassette obtained from the pSA-IRESβgeolox2PGKDTA plasmid designed by Drs. Philippe Soriano and Valera Vasioukhin. We used a 4.19 kb EcoRI fragment extending from positions −7.96 kb to −3.77 kb (position +1 corresponding to the transcription start site of Hoxa5 exon 1) for the D1 promoter and a 3.88 kb BglII-NruI fragment extending from positions −11.46 kb to −7.58 kb for the D2 promoter. The 2.1 kb mesodermal enhancer (MES) was inserted upstream the promoter region in both constructs [32]. The constructs were made in pBluescript SKII+ (Stratagene) and purified following a cesium chloride centrifugation.

The Hox/lacZ sequences were isolated using a SalI-NotI digestion to remove vector sequences and they were purified on agarose gel. They were injected into the pronuclei of fertilized eggs derived from (C57BL/6 x CBA) F1 hybrid intercrosses following standard procedures [60]. Transgenic founder embryos were recovered from foster mothers at e12.5, genotyped by Southern analysis of yolk sac DNA using a lacZ specific probe to verify the integrity of the microinjected construct, and analyzed for lacZ expression by β-galactosidase staining as previously described [32].

RNA in situ hybridization and immunofluorescence analyses

The whole-mount in situ hybridization protocol was based on the one described in [61], while radioactive in situ hybridization of paraffin sections was performed according to the protocol in [62]. The following murine genomic sequences were used as templates for synthesizing either digoxigenin or [35S] UTP-labeled riboprobes: a 830 bp BglII-HindIII fragment containing the 3′-untranslated region of the second exon of the Hoxa5 gene (probe a), a 606 bp BglII-XhoI fragment present in the intergenic region between Hoxa5 and Hoxa6 genes (probe b), a 675 bp HindIII-EcoRI sequence located just downstream the Hoxa7 gene (probe c), and a 356 bp KpnI fragment present in the Hoxa6 intron (probe d). The in situ experiments were performed on at least three specimens of each genotype.

Immunofluorescence staining with the rabbit anti-HOXA5 antibody and counterstaining with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Molecular Probes) was performed as described in [46].

Expression vectors, transfection, western and RT-PCR analyses

The sequence of the 1.8 kb cDNA was subcloned into the pcDNA3 expression plasmid (Invitrogen). A DNA fragment, from the p3XFLAG-MYC-CMV-24 expression vector (Sigma) and containing a MYC tag followed by the polyadenylation sequence of the human growth hormone gene, was inserted just before the stop codon of the HOXA5 protein using an overlapping PCR strategy with synthetic oligonucleotide primers covering the appropriate sequences [63]. A 5′-extended version of the 1.8 kb cDNA expression vector including the distal ATG codon in-frame with the HOXA5 open reading frame (ORF) was also designed. It contains upstream genomic sequences up to the EcoRV site at position −555 bp. This plasmid was made with and without the MYC tag. We also produced a pcDNA3 expression vector carrying the HOXA5-MYC version for the 5 kb-Hoxa5 cDNA as well as for the 5 kb-Hoxa6/a5 and for the 9.5 kb cDNAs. For these last two plasmids, a FLAG tag, from the p3XFLAG-MYC-CMV-24 vector, was added just before the HOXA6 stop codon. The TnT7 Quick coupled transcription-translation system (Promega) was used to produce [35S] methionine-labeled proteins according to the manufacturer's protocol. The translation products were analyzed by electrophoresis on a 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel (SDS-PAGE) and revealed by autoradiography.

HEK293 cells were transiently transfected by the calcium phosphate method in 60 mm petri dishes with 10 µg/dish of the Hox expression vectors [64]. The pEGFP-C2 expression vector was used to assess transfection efficiency (10 µg/dish; Clontech) and a pMEK1-MYC-FLAG plasmid (10 µg/dish; provided by Dr. Jean Charron) was used as a positive control for the immunodetection of the MYC and FLAG tags. Transfection of each plasmid was done in duplicate. Chloroquine was added at a final concentration of 50 µM. Three hours after transfection, the cells were shocked for 30 seconds at 37 °C with 15% glycerol in HEPES-buffered saline. Forty-eight hours after transfection, protein extracts were obtained after cell lysis in 300 µl of ice-cold lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1% NP-40, 10 mM EGTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 20 mM glycerol 2-phosphate, 25 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4 and a proteinase inhibitor cocktail (Complete Mini EDTA-free; Roche Diagnostics)). After 15 minutes on ice, the extracts were centrifuged at 15,000 g at 4°C. Protein content of the supernatant was quantified using a Lowry-based assay (DC Protein Assay, Bio-Rad), and 20 µg of total protein lysate was resolved on a denaturing 12% SDS-PAGE, electrotransferred onto nitrocellulose (PALL) and probed overnight at 4°C with either a MYC-tag rabbit monoclonal antibody at a dilution of 1/1,000 (Cell Signaling Technology) or an anti-FLAG mouse monoclonal antibody at a dilution of 1/10,000 (Sigma) according to manufacturer's instructions. Membranes were also incubated with a mouse monoclonal anti-GAPDH antibody at a dilution of 1/20,000 (Fitzgerald Industries International) for loading control. Membranes were then incubated with the appropriate secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody (a donkey anti-rabbit IgG at a dilution of 1/100,000 or a donkey anti-mouse at a dilution of 1/80,000; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Proteins were revealed by chemiluminescence using the Western Lighting Plus-ECL system (PerkinElmer) according to manufacturer's protocol.

Total RNA from transfected HEK293 cells was isolated according to the TRIzol RNA extraction protocol (Invitrogen) and cDNA was synthesized with Superscript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) using random primers. Reverse-transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) of the Hoxa5-myc portion was used to validate the expression of each transfected cDNA. PCR was performed for 25 cycles with an annealing temperature of 60°C. A 305 bp fragment was amplified with the Hoxa5 forward primer 5′-CCCAGATCTACCCCTGGATG-3′ and the MYC-tag reverse primer 5′-GATGAGTTTTTGTTCGGGGC-3′.

Skeletal analysis

Whole-mount skeletons were prepared from Hoxa5; Hoxa6 compound newborn pups with Alcian blue for staining the cartilage and Alizarin red for staining the bone, as described in [27]. Skeletons were observed, and left and right sides of each vertebra were scored independently for bilateral markers.

Supporting Information

Molecular characterization of the Hoxa5 alternate transcripts by 5′-RACE and RT-PCR. (A) The transcription initiation site of the larger transcripts was determined by 5′-RACE. Genomic organization of the Hoxa5, Hoxa6 and Hoxa7 genes along the cluster is shown. Black, grey and open boxes indicate homeobox, translated, and transcribed sequences, respectively. The primers used are indicated (arrows). With primer 1, we obtained several clones showing that the 9.5 and 11.0 kb transcripts initiate in the Hoxa6-Hoxa7 intergenic region at position −8905 bp. With primers 2 and 3, we obtained 5′-RACE products that revealed the presence of a 4.6 kb intron in the 5.0 kb transcript. The initiation site of this transcript also coincides with that of the 9.5 and 11.0 kb transcripts. A second population of clones was obtained with a transcription start site at position −4409 bp, which corresponds to the putative first base of Hoxa6 exon 1. (B) By using various primer combinations in RT-PCR experiments, we established the molecular structure of the different transcripts. We also demonstrated that the 5.0 kb band detected by northern analyses include minor splicing variants and two major RNA species, one initiating at −8905 bp and a second starting at −4409 bp. The latter corresponds to the putative Hoxa6 transcript. This transcript uses the polyA site of the Hoxa5 gene. This result correlates with the absence of a functional polyadenylation sequence at the Hoxa6 locus as shown by northen analysis. We also showed that splicing of the Hoxa5 intron is not always complete and a low percentage of the Hoxa5 transcripts contained intron sequences. A, AccI; B, BglII; Ba, BamHI; H, HindIII; K, KpnI; RI, EcoRI; S, SacI; St, StuI; Xh, XhoI.

(0.26 MB PPT)

Hoxa5 expression in the developing hindgut. Sections of e9.5 (A-C) and e10.5 (D-F) mouse embryos, and e15.5 (G-I), e17.5 (J–L) and DO (birth; M–O) hindgut tissues were hybridized with either probe a (B, E, H, K, N) or probe b (C, F, I, L, O). Bright-field views are shown on the left panels. (A–B) At e9.5, probe a detects Hoxa5 transcripts along the gut up to the caudal foregut (arrowhead). (C) Expression with probe b is restricted to a more posterior region. (D–I) From e10.5 to e15.5, both probes reveal signal in the mesenchyme of the hindgut, while probe a detects Hoxa5 transcripts in the myenteric plexi of the midgut (white arrow). (J–K) At e17.5, signal with probe a is confined to myenteric plexi in the proximal part of the hindgut (white arrow) while it still displays a diffuse mesenchymal expression in the distal hindgut. (M–N) Plexi of the enteric nervous system remain positive for probe a after birth as shown for D0. (L, O) No expression is observed with probe b from e17.5 onwards. d, distal hindgut; hg, hindgut; mg, midgut; p, proximal hindgut; tb, tailbud. Scale bar, 100 µm.

(6.19 MB TIF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jean Charron for insightful input on the manuscript and for the pMEK1-MYC-FLAG vector, Dr. Mario Capecchi for the Hoxa6 mutant mouse line, Drs. Philippe Soriano and Valera Vasioukhin for the pSA-IRESβgeolox2PGKDTA plasmid, Éric Paquet for help with bioinformatics, and Marcelle Carter, Lisa Danielczak and Nicolas Lafond for skilled technical assistance.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: This work was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) grant (MOP-68999 to L.J.) and a postdoctoral fellowship from the Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec-Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (FRSQ-INSERM; to O.B.). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Grier DG, Thompson A, Kwasniewska A, McGonigle GJ, Halliday HL, et al. The pathophysiology of HOX genes and their role in cancer. J Pathol. 2005;205:154–171. doi: 10.1002/path.1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krumlauf R. Hox genes in vertebrate development. Cell. 1994;78:191–201. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90290-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradshaw MS, Shashikant CS, Belting H-G, Bollekens JA, Ruddle FH. A long-range regulatory element of Hoxc8 identified by using the pClaster vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2426–2430. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Folberg A, Kovacs EN, Featherstone MS. Characterization and retinoic acid responsiveness of the murine Hoxd4 transcription unit. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:29151–29157. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.46.29151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sham MH, Hunt P, Nonchev S, Papalopulu N, Graham A, et al. Analysis of the murine Hox-2.7 gene: conserved alternative transcripts with differential distributions in the nervous system and the potential for shared regulatory regions. EMBO J. 1992;11:1825–1836. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05234.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gould A, Morrison A, Sproat G, White RAH, Krumlauf R. Positive cross-regulation and enhancer sharing: two mechanisms for specifying overlapping Hox expression patterns. Genes Dev. 1997;11:900–913. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.7.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kmita M, Duboule D. Organizing axes in time and space; 25 years of colinear tinkering. Science. 2003;301:331–333. doi: 10.1126/science.1085753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharpe J, Nonchev S, Gould A, Whiting J, Krumlauf Selectivity, sharing and competitive interactions in the regulation of Hoxb genes. EMBO J. 1998;17:1788–1798. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.6.1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duboule D. The rise and fall of Hox gene clusters. Development. 2007;134:2549–2560. doi: 10.1242/dev.001065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kmita M, Fraudeau N, Hérault Y, Duboule D. Serial deletions and duplications suggest a mechanism for the collinearity of Hoxd genes in limbs. Nature. 2002;420:145–150. doi: 10.1038/nature01189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kondo T, Duboule D. Breaking colinearity in the mouse HoxD complex. Cell. 1999;97:407–417. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80749-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spitz F, Gonzalez F, Duboule D. A global control region defines a chromosomal regulatory landscape containing the HoxD cluster. Cell. 2003;113:405–417. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00310-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chambeyron S, Bickmore WA. Chromatin decondensation and nuclear reorganization of the HoxB locus upon induction of transcription. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1119–1130. doi: 10.1101/gad.292104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morey C, Da Silva NR, Perry P, Bickmore WA. Nuclear reorganisation and chromatin decondensation are conserved, but distinct, mechanisms linked to Hox gene activation. Development. 2007;134:909–919. doi: 10.1242/dev.02779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brend T, Gilthorpe J, Summerbell D, Rigby PW. Multiple levels of transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation are required to define the domain of Hoxb4 expression. Development. 2003;130:2717–2728. doi: 10.1242/dev.00471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naguibneva I, Ameyar-Zazoua M, Polesskaya A, Ait-Si-Ali S, Groisman R, et al. The microRNA miR-181 targets the homeobox protein Hox-A11 during mammalian myoblaast differentiation. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;8:278–284. doi: 10.1038/ncb1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yekta S, Shih I-h, Bartel DP. MicroRNA-directed cleavage of HOXB8 mRNA. Science. 2004;304:594–596. doi: 10.1126/science.1097434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsieh-Li HM, Witte DP, Weinstein M, Brandford W, Li H, et al. Hoxa11 structure, extensive antisense transcription, and function in male and female fertility. Development. 1995;121:1373–1385. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.5.1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mainguy G, Koster J, Woltering J, Jansen H, Durston A. Extensive polycistronic and antisense transcription in the mammalian Hox clusters. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e356. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rinn JL, Kertesz M, Wang JK, Squazzo SL, Xu X, et al. Functional demarcation of active and silent chromatin domains in human HOX loci by noncoding RNAs. Cell. 2007;129:1311–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sasaki YTF, Sano M, Kin T, Asai K, Hirose T. Coordinated expression of ncRNAs and HOX mRNAs in the human HOXA locus. BBRC. 2007;357:724–730. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.03.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sessa L, Breiling A, Lavorgna G, Silvestri L, Casari G, et al. Noncoding RNA synthesis and loss of Polycomb group repression accompanies the colinear activation of the human HOX cluster. RNA. 2007;13:223–239. doi: 10.1261/rna.266707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeannotte L, Lemieux M, Charron J, Poirier F, Robertson EJ. Specification of axial identity in the mouse: role of the Hoxa-5 (Hox1.3) gene. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2085–2096. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.11.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okada Y, Jiang Q, Lemieux M, Jeannotte L, Su L, et al. Leukaemic transformation by CALM-AF10 involves upregulation of Hoxa5 by hDOTIL. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1017–1024. doi: 10.1038/ncb1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gendronneau G, Lemieux M, Morneau M, Paradis J, Têtu B, et al. Influence of Hoxa5 on p53 tumorigenic outcome in mice. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:995–1005. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aubin J, Lemieux M, Tremblay M, Bérard J, Jeannotte L. Early postnatal lethality in Hoxa-5 mutant mice is attributable to respiratory tract defects. Dev Biol. 1997;192:432–445. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aubin J, Lemieux M, Tremblay M, Behringer RR, Jeannotte L. Transcriptional interferences at the Hoxa4/Hoxa5 locus: Importance of correct Hoxa5 expression for the proper specification of the axial skeleton. Dev Dyn. 1998;212:141–156. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199805)212:1<141::AID-AJA13>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aubin J, Chailler P, Ménard D, Jeannotte L. Loss of Hoxa5 gene function in mice perturbs intestinal maturation. Am J Physio. 1999;277:C965–C973. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.277.5.C965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aubin J, Déry U, Lemieux M, Chailler P, Jeannotte L. Stomach regional specification requires Hoxa5-driven mesenchymal-epithelial signaling. Development. 2002;129:4075–4087. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.17.4075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dony C, Gruss P. Specific expression of the Hox1.3 homeo box gene in murine embryonic structures originating from or induced by the mesoderm. EMBO J. 1987;6:2965–2975. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02602.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gaunt SJ, Coletta PL, Pravtcheva D, Sharpe PT. Mouse Hox-3.4: homeobox sequence and embryonic expression patterns compared to other members of the Hox gene network. Development. 1990;109:329–339. doi: 10.1242/dev.109.2.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Larochelle C, Tremblay M, Bernier D, Aubin J, Jeannotte L. Multiple cis-acting regulatory regions are required for the restricted spatio-temporal Hox5 gene expression. Dev Dyn. 1999;214:127–140. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199902)214:2<127::AID-AJA3>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tabariès S, Lemieux M, Aubin J, Jeannotte L. Comparative analysis of Hoxa5 allelic series. Genesis. 2007;45:218–228. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garin É, Lemieux M, Coulombe Y, Robinson GW, Jeannotte L. Stromal Hoxa5 function controls the growth and differentiation of mammary alveolar epithelium. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:1858–1871. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meunier D, Aubin J, Jeannotte L. Perturbed thyroid morphology and transient hypothyroidism symptoms in Hoxa5 mutant mice. Dev Dyn. 2003;227:367–378. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Odenwald WF, Taylor CF, Palmer-Hill FJ, Friedrich V, Jr, Tani M, et al. Expression of a homeo domain protein in noncontact-inhibited cultured cells and postmitotic neurons. Genes Dev. 1987;1:482–496. doi: 10.1101/gad.1.5.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zakany J, Tuggle CK, Patel M, Nguyen-Huu MC. Spatial regulation of homeobox gene fusions in the embryonic central nervous system of transgenic mice. Neuron. 1988;1:679–691. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90167-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Püschel A, Balling WR, Gruss P. Position-specific activity of the Hox1.1 promoter in transgenic mice. Development. 1990;108:435–442. doi: 10.1242/dev.108.3.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moreau J, Jeannotte L. Sequence analysis of a Hoxa4-Hoxa5 intergenic region including shared regulatory elements. DNA Seq. 2002;13:203–209. doi: 10.1080/10425170290034507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nowling T, Zhou W, Krieger KE, Larochelle C, Nguyen-Huu MC, et al. Hoxa5 gene regulation: A gradient of binding activity to a brachial spinal cord element. Dev Biol. 1999;208:134–146. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tabariès S, Lapointe J, Besch T, Carter M, Woollard J, et al. Cdx protein interaction with Hoxa5 regulatory sequences contributes to Hoxa5 regional expression along the axial skeleton. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:1389–1401. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.4.1389-1401.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Packer AI, Crotty DA, Elwell VA, Wolgemuth DJ. Expression of the murine Hoxa4 gene requires both autoregulation and a conserved retinoic acid response element. Development. 1998;125:1991–1998. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.11.1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jeannotte L, Ruiz JC, Robertson EJ. Low level of Hox1.3 gene expression does not preclude the use of promoterless vectors to generate a targeted gene disruption. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:5578–5585. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.11.5578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kostic D, Capecchi MR. Targeted disruptions of the murine Hoxa-4 and Hoxa-6 genes result in homeotic transformations of components of the vertebral column. Mech Dev. 1994;46:231–247. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(94)90073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karolchik D, Hinrichs AS, Kent WJ. The UCSC genome browser. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. Dec., 2009;Chapter 1:Unit1.4. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0104s28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Joksimovic M, Jeannotte L, Tuggle CK. Dynamic expression of murine HOXA5 protein in the central nervous system. Gene Expr Patterns. 2005;5:792–800. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Popovic R, Erfurth F, Zeleznik-Le N. Transcriptional complexity at the HOXA9 locus. Blood cells, Molec Diseases. 2008;40:156–159. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dintilhac A, Bihan R, Guerrier D, Deschamps S, Pellerin I. A conserved non-homeodomain Hoxa9 isoform interacting with CBP is co-expressed with the typical Hoxa9 protein during embryogenesis. Gene Expr Patterns. 2004;4:215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bijl J, Sauvageau M, Thompson A, Sauvageau G. High incidence of proviral integrations in the Hoxa locus in a new model of E2a-PBX1-induced B-cell leukemia. Genes Dev. 2005;19:224–233. doi: 10.1101/gad.1268505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kozak M. Regulation of translation via mRNA structure in prokaryotes and eukaryotes Gene. 2005;361:13–37. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Simeone A, Pannese M, Acampora D, D'Esposito M, Boncinelli E. At least three human homeoboxes on chromosome 12 belong to the same transcription unit. Nucl Acids Res. 1988;16:5379–5390. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.12.5379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Santini S, Boore JL, Meyer A. Evolutionary conservation of regulatory elements in vertebrate Hox clusters. Genome Res. 2003;13:1111–1122. doi: 10.1101/gr.700503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brock HW, Hodgson JW, Petruk S, Mazo A. Regulatory noncoding RNAs at Hox loci. Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;87:27–34. doi: 10.1139/O08-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pontig CP, Oliver PL, Reik W. Evolution and functions of long noncoding RNAs. Cell. 2009;136:629–641. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sharp PA. The centrality of RNA. Cell. 2009;136:577–580. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gingeras TR. Implications of chimearic non-co-linear transcripts. Nature. 2009;461:206–211. doi: 10.1038/nature08452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]