Abstract

A new method of optically guided controlled release was experimentally evaluated with liposomes containing a molecular load and gold nanoparticles (NPs). NPs were exposed to short laser pulses to induce transient vapor bubbles around the NPs, plasmonic nanobubbles, in order to disrupt the liposome and eject its molecular contents. The release efficacy was tuned by varying the lifetime and size of the nanobubble with the fluence of the laser pulse. Optical scattering by nanobubbles correlated to the molecular release and was used to guide the release. The release of two fluorescent proteins from individual liposomes has been directly monitored by fluorescence microscopy, while the generation of the plasmonic nanobubbles was imaged and measured with optical scattering techniques. Plasmonic nanobubble-induced release was found to be a mechanical, nonthermal process that requires a single laser pulse and ejects of the liposome contents within a millisecond timescale without damage to the molecular cargo and that can be controlled through the fluence of laser pulse.

Keywords: liposome, bubble, release, photothermal, gold nanoparticles, pulsed laser

1. Introduction

An accuracy of the delivery of therapeutic and diagnostic agents is associated with one of the biggest challenges of chemotherapy and medicine in general. Often the drug concentration necessary to treat a target cell is toxic to normal tissue because the selectivity and efficacy of the delivery is very low. The most advanced approach to the problem of delivery of toxic agents is based on their temporal encapsulation, delivery of the capsule to the target and controlled release from the capsule upon the delivery. Microscale sized, drug-carrying capsules composed of lipids or multiple polyelectrolyte layers have made it possible to deliver drugs slowly over time [1,2]. More recently it has become possible to control the release of drugs or onset of treatment until the microcapsules are in the desired place. However, many of the release techniques (thermal, chemical, biological) can be harmful to healthy cells because they do not provide reliable protection from undesired accidental triggering of the release [3]. This poses the problem of improving the control of the release process. Q1Furthermore, cell defense mechanisms can make the intracellular delivery of therapeutic agents difficult or impossible due to the inability of drugs to overcome endocytotic barriers. Nanoparticles (NPs), including liposomes, micelles and polymer- and polyelectrolyte-based capsules, have been considered recently as promising delivery vehicles [4], since NPs are small enough to penetrate cells and may carry both the therapeutic agent and imaging probe thus providing the multiple functions of therapy and its guidance. The main challenges of current delivery methods, however, remain to be the spatial and temporal control of the release, the selectivity of its mechanism and prevention of accidental premature release [5].

These challenges have been addressed through the development of the release methods that do not depend upon biochemical and physiological processes, but employ the remote thermal or acoustical activation of the release. Plasmonic nanoparticles when added into various capsules [1, 6-14] have acted as optically activated heat sources to stimulate the release. The subsequent thermal effects result in the structural breakdown of the capsule, releasing its molecular cargo into the surrounding environment. The reported works have employed plasmon resonant gold nanoparticles to stimulate liposome heating. The heating of the liposome membrane turns the lipid bilayer boundary into liquid state thus allowing the diffusion of the liposome content. However, this mechanism relies mainly on continuous (or quasi-continuous) optical activation and on a relatively high concentration of the nanoparticles so to provide a significant thermal effect. Also, thermal diffusion causes an uncontrollable spread of an elevated temperature, which is unsafe for the liposome content and for surrounding tissues.

Besides the thermal techniques the acoustical mechanisms were employed for the controlled release. In [9], the laser-induced bubbles were assumed as a possible additional cause of the liposome disruption, though neither bubble nor the liposome disruption were directly detected. Acoustically and optically activated bubbles have also been used for the delivery of the drugs by disrupting the capsules or the cellular membranes with so-called opto- and sono-poration methods [15-18]. Generation of such bubbles can mechanically disrupt the capsule membrane, resulting in release of the capsule load. However, the generation of acoustically- and optically-induced bubbles also includes other laser-induced adverse effects such as heating (for long optical exposure) or generation of detrimental pressure waves (for short optical pulses). Also, acoustically generated bubbles cannot provide high selectivity, inducing collateral disruption and damage to normal cells and tissues. Bubbles also possess excellent optical scattering properties [3,18-23] that may help with their detection at the nano-scale and may improve the NP-based optical sensing and imaging through the amplification of the scattered light by the orders of magnitude relative to that of NPs. It is possible to generate vapor bubbles around optically absorbing plasmonic nanoparticles using laser pulses. Laser-induced evaporation and cavitation around NPs remain the most under-recognized photothermal phenomena. Optical generation and detection of tissue-generated vapor bubbles have been studied at the macro- and micro-scale level for various biomedical tasks [24-27]. However, the studies of bubble generation around laser-heated NPs [28-30] and at the nanometer scale [31] are rather scarce and, up to now, application of the nanoparticle-generated bubbles has not been systemically considered for the purpose of the controlled release and delivery.

Several methods of the optically-guided delivery have been developed where optical guidance was based on fluorescent markers [32-38]. While guiding the release process, such fluorescent markers themselves may not be biologically safe and optically stable, especially when exposed to various biochemical processes. Resuming all the above we may point out several general challenges of the release methods and associated tasks:

-Improving the control of the release mechanism to avoid premature or delayed release, and associated safety issues (since the encapsulated content may be potentially toxic).

- Ability to control the time and speed of the release (tunable release).

- Improving the selectivity of the release mechanism so to activate only specific carriers.

- Reliable guidance mechanism of the release that is protected from environmental biological and chemical impacts.

We have hypothesized that a combination of the properties of plasmonic nanoparticles with those of the photothermal vapor bubbles may be a key solution to the above requirements. First, the nanoparticle-generated vapor bubbles (plasmonic nanobubbles) may support mechanical localized disruption as the release mechanism, can quickly eject the molecular load (the process that is much faster than the diffusion) and optical scattering by plasmonic nanobubble would provide the guidance of the release. Q2Second, being transient phenomena, plasmonic nanobubbles use the safest available probes (gold nanoparticles [39,40]). Third, unlike bigger macro-bubbles, plasmonic nanobubbles can be generated in the controllable way to provide localized effects in individual liposomes or other delivery vehicles. In this work we have experimentally tested our hypothesis using liposomes as delivery vehicles, fluorescent proteins as the model for the molecular load and plasmonic nanobubbles (PNB) as the multifunctional agent for release and guidance probe.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Liposomes

The liposomes were loaded with specific fluorescent molecules (the proteins R-phycoerythin (PE) (240kDa, Invitrogen, P801) or allophycocyanin (APC) (104kDa, Invitrogen, A803), and with 80-nm gold spheres (Ted Pella, Inc., #15710-20). Liposomes with a slight positive charge were prepared so that they would be stationary on the plasma cleaned (negative) glass substrate. The protocol outlined by Avanti polar lipids was followed for a mixture of 80% 1,2-Dioleoyl-sn-Glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC) and 20% 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane (DOTAP) lipids (purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc.). Q8This mixture of cationic and zwitterionic lipids results in cationic liposomes with a positive zeta potential [41]. The two lipids species were dissolved in chloroform at 5 mg/ mL, and 1 mL of this solution was dried in a glass vessel with N2 for several minutes. In order to ensure full evaporation of the organic solvent, the samples were placed in vacuum for 1 hour. The sample was then hydrated with 1 mL of Q718 MΩ deionized water without buffer containing 5% PE or APC by volume, and 80 nm gold spheres concentrated to 1011 mL−1. Hydration of the dried lipid bilayers triggers the formation of liposomes. Q21The mixture sat at 4°C overnight then was moved to a clean container and sonicated for 5 minutes. Next, the sample was immersed in liquid nitrogen for 5 minutes, then a warm water bath for 5 minutes. These freeze/thaw cycles were repeated a total of 5 times, and the sample was sonicated again for 5 minutes. Sonication and the freeze/thaw cycles cause the formed liposomes to break down into smaller liposomes. Q13Next, the sample was centrifuged for 2 minutes at 1.7 kRCF, the supernatant was removed (to remove the free dye) and replaced by H2O. In the sample with NPs, a small pellet of free NPs was also removed. This was repeated for a total of 2-3 times to ensure that remaining dye and NPs were mostly inside liposomes. Q9Finally, the liposomes solution was extruded with a Avanti Polar Lipids miniextruder through a 1 micrometer pore size filter 9 times to create monodisperse liposomes.

Q5 and 15One can estimate the number of nanoparticles per liposome by assuming the entire mass of lipids forms monodisperse 1 micron diameter single unilamellar liposomes, and that the lipid headgroup area in the liposome is 70A2. This yields a liposome concentration of approximately 4 × 1011 mL−1 and volume fraction of 20%. If one assumes that the nanoparticles are uniformly distributed throughout the liposome solution at 1 × 1011 mL−1, there would be only 1 nanoparticle per 4 liposomes. Considering the limited volume fraction of the liposomes, one would expect only 1 in 20 liposomes to contain a nanoparticle. Of course, this rough estimate could be affected by polydispersity in the liposomes, interactions between the nanoparticles and lipids (which would increase loading), and aggregation of the nanoparticles when concentrated (which would create aggregates in the liposomes). Furthermore, high yield loading is not required since this report describes single liposome experiments rather than ensemble measurements. Q9To avoid the above limitations of the liposome preparations were have analyzed only individual liposomes and have used the optical scattering by gold NPs to identify and to select the liposome with NPs for the measurements. Optical scattering imaging was also used to characterize individual liposomes in the sample chamber and also as a relative measure of their diameter, since the amplitude of the scattered light correlates with the diameter of scattering object. The liposomes were found to be monodisperse, and only the liposomes with similar amplitudes of their scattering images (that have delivered the bubbles) were employed for the measurements. Q16We have obtained the data for 50 liposomes and have analyzed the averaged data. Q14The liposomes have been used in the experiments within 1-2 days after their preparation. Within that period their stability was quantitatively monitored through the amplitudes of the scattering and fluorescent images of individual liposomes.

2.2. Generation and detection of plasmonic nanobubbles

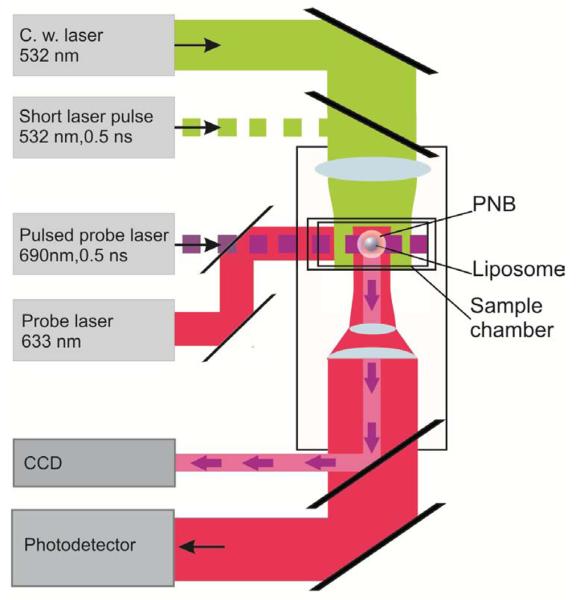

The gold NPs, which are extremely efficient at converting optical energy into thermal energy, were used as PNB sources. The following experiments were preformed using a photothermal microscope that we have recently developed [22] (Fig. 1). Liposomes were studied in distilled water in an sealed cell prepared a microscope slide and were immobilized at the bottom of the cell through electrostatic forces as described above. Individual liposomes were positioned at the center of focused laser beam and were irradiated with a single pump laser pulse, inducing the PNB. The pump pulse (532 nm, 0.5 ns, model SH-STA, Standa Ltd, Lithuania) was focused into the spot of 14 μm diameter. The fluence of this pulse was varied with the optical attenuator in the range 0.01 − 1 J/cm2 and has been measured by monitoring the energy and the diameter of the pump pulse.

Figure 1.

Experimental set up uses inverted optical microscope and 4 lasers for generation and detection of the PNBs and of the fluorescent images.

The PNBs were imaged with Luka CCD camera (Andor Plc, N. Ireland) that has been used to register the pulsed probe laser radiation (690 nm, 0.5 ns, delay 10 ns relative to the pump pulse) that has been scattered by the PNB. The pixel amplitude of this time-resolved pulsed image was used to estimate the brightness of the PNB and to correlate the PNB to the fluorescence of the molecular load of the liposome. A18The stationary background image (obtained prior to the exposure to pump laser pulse) has been subtracted from the scattering image obtained with the delay of 10 ns to the pump pulse. Thus we have analyzed only transient scattering in the time domain that was associated with the PNB generation. The lifetime (and hence the maximal diameter) of the PNB was measured with an additional continuous probe laser (633 nm, 0.1 mW) that was focused on the liposome collinearly with the pump laser beam (Fig. 1). The axial intensity of this beam was registered with fast photodetector (PDB-110C, Thorlabs, INC) and has been analyzed as a time-response. Optical scattering of this probe beam and the kinetics of the PNB produce the signal of the PNB-specific shape (as we have found previously [22,42]) that allows to detect the PNB and to measure its lifetime. Q16PNBs were quantified with the two parameters:

-PNB generation probability PRB has been measured at specific laser fluence as the ratio of the PNB-positive events to the total number of the irradiated liposomes; thus the PRB has meant the probability of the bubble generation in the liposome under specific level of the pump laser fluence;

-PNB lifetime has been measured as the duration of the PNB-specific time-response at the level of 0.5 of the maximum of the response; this parameter has described the mechanical impact of PNB.

2.3. Monitoring the liposome load

Q3To independently monitor and quantify the release we have used fluorescent proteins (PE and APC) as the molecular load. Relatively big molecules of the above proteins were chosen instead of small molecules of fluorescent dyes for the purpose of the evaluation of potentially destructive action of PNBs upon liposome load. In case of thermal denaturation the protein's fluorescent yield would drop significantly, so in a case of the PNB-induced thermal damage we would observe no fluorescence. Q13 The level of the initial level of the liposome load with APC and PE has been characterized by the pixel image amplitudes of the fluorescent images of individual liposomes.

Fluorescent images were obtained with the above described CCD camera. Low-power continuous laser excitations of PE at 532 nm and APC at 633 nm were used so to maximize the sensitivity of the imaging of individual liposomes. Three fluorescent images were obtained: before the PNB generation (initial condition), 10-30 ms after the PNB generation (in attempt to directly detect the released molecules) and 60 s after the PNB generation (to estimate the residual fluorescence of the liposome). Fluorescent imaging was also used in an additional experiment to monitor the state of the fluorescent proteins after being exposed to the PNB, as it is well known that proteins can be thermally damaged when being exposed to the elevated temperature. Q3We have used a glass substrate coated with Poly-l-lysine to trap the released protein in the vicinity of the liposome that was disrupted by the PNB. While this reduces the liposome binding to the substrate, we still find sufficient bound liposomes to carry out the experiments. The residual fluorescence of the protein trapped by the substrate is possible only for molecules that were not thermally damaged. Therefore, detection of the residual fluorescence outside the liposome and after the generation of the PNB is considered to be evidence that molecular functionality of the proteins was preserved.

The influence of the PNB on the liposome was quantified by comparing the pixel amplitudes of the optical scattering and fluorescent images before and after the PNB generation. The relative amplitudes for residual fluorescence (RF) and residual scattering (RS) are defined as follows:

where Is and If are the average pixel amplitude of the scattering and fluorescence measurements respectively, and Ibkg is the average background pixel amplitude of the image. RF directly characterizes the efficacy of the release of the fluorescent molecules from the liposome, and RS characterizes the integrity or destruction of the liposome as a solid object. RS and RF were correlated to the PNBs as characterized by the following parameters:

- Probability of the PNB generation at specific pump laser fluence.

- PNB generation threshold fluence.

- Lifetime (measure of the PNB maximal diameter).

- Scattering image pixel amplitude (measure of the PNB optical brightness).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Generation and detection of PNB in liposomes

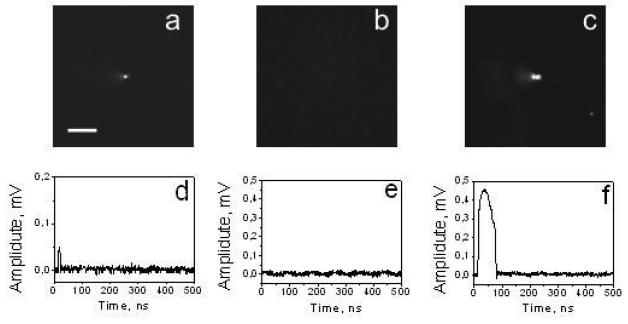

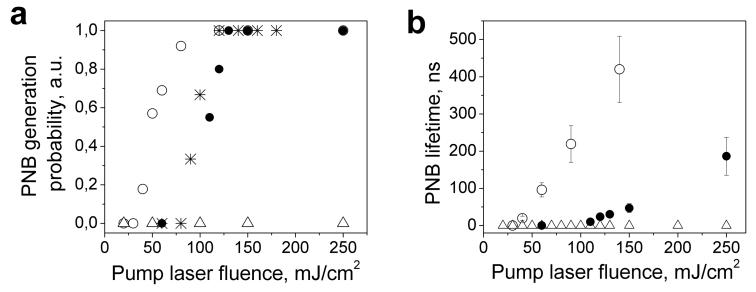

We have applied a single pump laser pulse to individual objects in five samples: 80-nm gold NPs, liposomes with the PE or APC, with and without NPs (Fig. 2). Q5,15Individual liposomes containing NPs (in the corresponding samples) were selected and measured based on their corresponding optical scattering images. Due to the significant difference in scattering image amplitudes between “empty” liposomes and those with gold NPs were able to select only the liposomes with NPs for the measurements of the corresponding preparations. Q18The images shown at Fig. 2a-c have been obtained for the time domain corresponding to the pump laser pulse and at the delay of 10 ns. Thus they show only transient phenomena induced by the pump pulse and do not show the steady scattering (that has been subtracted as the background). We have measured the probability of the PNB generation at different pump fluence levels (Fig. 3a) and have determined the PNB generation threshold fluence for each sample as the fluence that corresponded to a PNB generation probability of 0.5 (Table 1). Under identical conditions the liposomes with PE and NPs have yielded the brightest PNB (Fig. 2c), the longest time-responses (Fig. 2f), the highest probability of the PNB generation (Fig. 3a) and the lowest PNB generation threshold fluence (Table 1). Furthermore, the PNB generation threshold fluence in the liposomes with PE and NPs was found to be almost 3 times lower than that of individual 80 nm NPs. This may be due to the formation of the NP clusters in the liposomes: several NPs are brought close together inside the liposome as the result of the encapsulation procedure. Our previous results support this conclusion and also have revealed the lower PNB generation thresholds for the NP clusters relative to that for single NPs [18,22]. The initial amplitude of optical scattering images (prior to the exposure to the pump laser pulse) for the liposomes with NPs and PE (Table 1) was found to be the highest, Q6also suggesting NP clusters. The liposomes prepared with the APC and NPs yielded PNB signals that were close to those of single NPs (Fig. 3a, Table 1). It should be noted that in the applied range of the pump pulse fluences (from 0.01 to 2 J/cm2) we did not observe the generation of the PNBs in the liposomes with PE or APC only (the controls). Therefore, the generation of the PNB was depended upon the pump laser fluence and presence of NPs inside the liposomes. From these results, we can conclude that the process of the PNB generation is reliable and highly selective to occur around the NPs, excluding undesired generation of the PNBs in the liposomes without NPs.

Figure 2.

Q17 Pulsed scattering images (a-c) and time-responses (d-f) acquired with a single pump laser pulse for single 80-nm gold nanoparticle (a,d), single liposome with PE molecules (b,e) and for a single liposome with PE and 80-nm gold nanoparticles (c,f). Scale bar is 10μm.

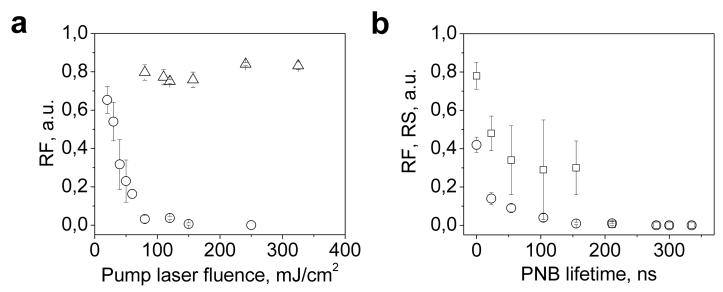

Figure 3.

(a) PNB generation probability vs. pump laser fluence for liposomes loaded with NPs and PE (hollow circles), liposomes loaded with NPs and APC (stars), single NPs (solid circles), and liposomes loaded with PE only (triangles) (b) PNB lifetime vs. pump laser fluence for liposomes loaded with NPs and PE (hollow circles), single NPs (solid circles) and liposomes loaded with PE only (triangles).

Table 1.

Q18Optical scattering efficacy of intact liposomes and NPs and PNB generation thresholds in the experimental samples.

| 80 nm gold spheres |

Liposomes with PE |

Liposomes with gold NPs and PE |

Liposomes with APC |

Liposomes with gold NPs and APC |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optical scattering image pixel amplitude Is, counts |

312±17 | 2356±239 | 9813±381 | 2503±340 | 3922±323 |

| PNB generation threshold fluence of the pump laser pulse, J/cm2 |

0.11 | >2.0 | 0.039 | >2.0 | 0.1 |

Next, we have studied the tunability of the PNB maximal diameter, since the disruptive effect is the result of the PNB size (as we have found previously in living cells [43,44]). We have measured the lifetime of the PNB generated in liposomes with the PE and NPs and around single NPs (Fig. 3b). The lifetime is directly proportional to the maximal diameter of the PNB and has been measured for individual liposomes. We did not measure this parameter for the liposomes containing only the fluorescent molecules since we previously found that no PNBs were generated in such liposomes. According to obtained data, the PNB lifetime gradually increased with the pump laser fluence both for NPs and the liposomes with NPs and the dependences are close to linear. The slope of the liposome dependence was higher than that of the NPs, which means the liposomes have higher photothermal efficacy due to the NP clusterization. The intersections of these data-lines with x-axis were off-set from zero, indicating PNB generation thresholds that are in line with the previously determined thresholds for these samples (Table 1). Also, we have found that the PNB generation in the liposomes was reproducible when more than one pump pulse was applied to the same liposome. Therefore, several sequential PNBs can be generated on-demand. Our results allow us to conclude that the PNB lifetime (and hence the maximal diameter) can be tuned through the level of the pump laser fluence. The tunablity and the selectivity of the generation should be considered as the main properties of the PNB.

3.2. PNB-induced release of fluorescent molecules from the liposomes

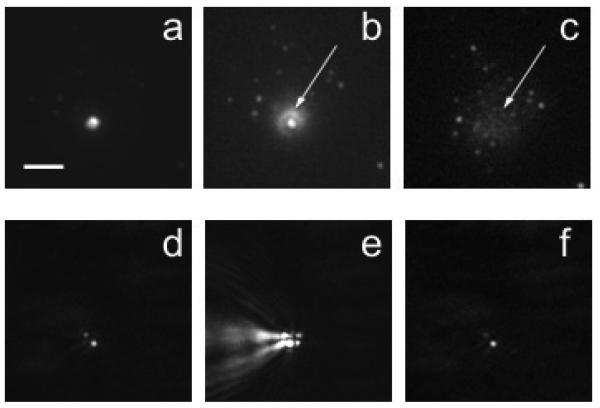

Based on the established properties of PNBs, we have studied their influence on the release of a specific molecular load from individual liposomes. The liposomes were positioned in the center of the laser beams and their fluorescence (Fig. 4a) and optical scattering (Fig. 4d) images were obtained before the generation of the PNB. During the exposure to the pump laser pulse the optical scattering of the PNB was imaged at 10 ns time delay (Fig. 4e) and the 2nd fluorescent image has been registered at 10-30 ms time delay (Fig. 4b). The latter distinctly shows the molecular-specific fluorescence outside the liposome in a concentric halo. This is direct imaging of the release of the fluorescent molecules from the liposome. At a later stage (60 s after the pump laser pulse) there is no fluorescent halo around the liposome, and the level of fluorescence in the liposome has dropped (Fig. 4c). Therefore, the generation of the single PNB has caused the release of the fluorescent protein from the liposome within milliseconds. Optical scattering images of the liposome before (Fig. 4d) and 60 s after the generation of the PNB (Fig. 4f) show that the PNB and the release of the fluorescent molecules did not destroy the liposome despite a significant (more than 10-fold) drop of the fluorescence amplitude, the scattering amplitude did not change significantly.

Figure 4.

Q17Bubble generation in single liposome containing APC protein and 80 nm gold NPs: (a) APC fluorescence of a single liposome before the generation of the PNB, (b) APC ejection from liposome by the NP-generated bubble (released APC is the halo shown with an arrow), (c) residual fluorescence of APC after its release and trapping by the substrate (arrows); optical scattering images show: (d) gold NPs in the same liposome, (e) the NP-generated bubble, (f) the same liposome through 60 s after the generation of the bubble (0.5 ns, 532 nm). Scale bar is 10 μm.

The next important question was to estimate the influence of the PNB on the protein molecules since the PNB is associated with thermal and mechanical impact. In this experiment we used a substrate coated with Polyl-lysine to trap and concentrate the released molecules in the vicinity of the liposome. After the generating the PNB in the liposome fluorescent spots that were scattered within several micrometers around the liposome can be observed (Fig. 4c). Therefore, at least some part of the liposome load was released without apparent damage to the molecules. Additionally, the PNB response (Fig. 2f) amplitude returned to the baseline immediately after the termination of the PNB, offering additional evidence of the absence of thermal impact on the released molecules. The level of the response amplitude after the PNB characterizes the relative change of the bulk temperature in the volume that is irradiated by the probe laser. A return to the baseline means that the temperature did not deviate from the initial level. This effect of “thermal insulation” of the PNB was previously reported by us in detail [22,45]. The “viability” test as applied was rather rough and in future we will analyze the release of specific antibodies and their binding to the substrate of the matching antigens. Nevertheless, we may conclude that the PNB-induced release does not destroy the protein molecules employed as they maintain their fluorescent properties after the release.

The control liposomes (with fluorescent molecules and no gold NPs) yielded no change during and after the exposure to the pump laser pulse; neither a PNB, outside dynamics or residual fluorescence were detected. Therefore, we conclude that the release was cause by the generation of the PNB in the liposomes and that a single laser pulse and a single PNB was sufficient to provide the release. Also, we conclude that the release is a mechanical process since we detected no increase in temperature after the PNB and no lyses or other irreversible change of the liposome. We suggest that the mechanism of the release is associated with the two PNB-induced processes: disruption of the liposome membrane and the ejection of the liposome load by the expanding bubble. This explains why we observed the halo in 10-30 ms (Fig. 4b): the diffusion of the molecules from the disrupted liposome could not produce this structure while it perfectly matched the bubble mechanism.

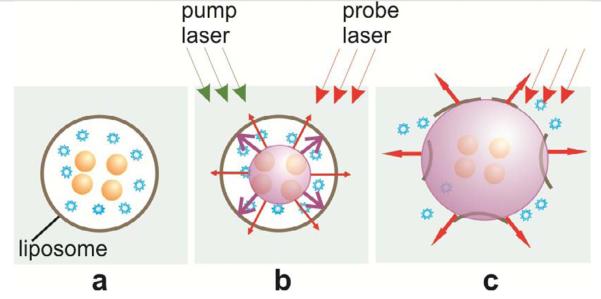

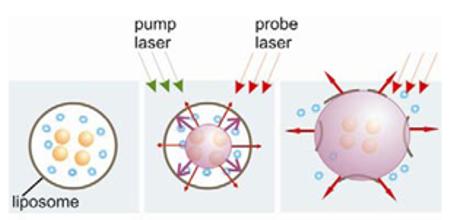

Q10,11,12Obtained results can be explained through the following mechanism. Upon absorption of a single 0.5 ns laser pulse, gold NPs (assumingly trapped inside the liposome) quickly evaporate the surrounding liquid medium. The evaporated medium forms a vapor bubble that we refer to as plasmonic nanobubble (Fig. 5b). The PNB expands to a maximal diameter and then collapses and disappears. Maximal diameter of the PNB is proportional to its lifetime [22,25,45-49]. A rapidly expanding bubble can mechanically disrupt the liposome, pushing the molecular load out (Fig. 5c).

Figure 5.

Scheme of optically-guided controlled release of encapsulated molecules (blue) (a) with PNB (b) that disrupts the liposome and quickly ejects its content into outer medium (c); imaging and optical monitoring of the PNB at the stage (c) provide the guidance of the release process.

As we have shown previously, the lifetime (and hence the size) of the nanoparticle-generated bubbles can be controlled by varying the laser pulse fluence and the plasmonic properties of the gold NPs [22,49,50]. Also, we have demonstrated the mechanically disruptive action of such bubbles for selective destruction of cancerous cells [43,44]. PNBs also possess two other properties that are important in controlled release that we have verified experimentally:

- Thermal energy is concentrated inside PNBs [22,45], protecting the outer molecular load from thermal damage;

- PNBs have excellent optical scattering properties (that exceed those of gold NPs and of fluorescent molecules), which depend on their size. [18,23] Therefore, optical scattering by PNBs may be used to guide the release process.

Since the PNB is a localized phenomena that exists on-demand at the nanoscale, verification of this mechanism requires the generation of a PNB and monitoring the release from individual liposomes. The PNB lifetime is in the range of 10 – 1000 ns and the size may vary from 50 nm to micrometers. Therefore, it is critical to correlate the PNB generation with the release of the liposome load, requiring direct detection and monitoring of the PNBs in individual liposomes. Unlike previous attempts where laser-heated NPs were used without detection of bubbles nor monitoring of the release process in individual liposomes, [1,6-9] we have provided the direct imaging of PNBs.

This mechanism was studied in more quantitative way while focusing on how to control and tune the release process. We have generated the PNBs in individual liposomes at the different levels of the pump laser fluence starting from those below the PNB generation threshold. We have measured the relative change of the amplitudes of fluorescence and optical scattering in each individual liposome (50 single liposomes) as the function of the pump laser fluence (Fig. 6a). We have correlated these two parameters to the PNB lifetime, which was measured simultaneously (Fig. 6b). Increase of the laser fluence above the PNB threshold caused a significant drop in the fluorescence only in the liposomes with NPs, while the liposomes without NPs did not respond to the pump pulse and maintained their fluorescence in the full range of the applied fluences (Fig. 6a). This, in addition to those discussed above, offers evidence that the release of molecule load was associated with the PNB. The behavior of optical scattering amplitudes, which characterize the integrity of the liposome and the presence of gold NPs, dropped at higher fluences compared to the drop of the fluorescence (Fig. 6b). We have re-plotted the data from figure 6a and have analyzed the fluorescence and scattering as a function of the PNB lifetime (which characterizes its maximal diameter). The dependence of the relative change of fluorescence has a clear dependence upon the PNB lifetime in the range of 10 – 60 ns (Fig. 6b). This means that the efficacy of the release can be tuned by varying the pump laser fluence (and therefore, PNB lifetime) (Fig. 3b). Based on these results, we conclude that the PNB mechanism of release is fast and very reliable: it requires a single pulse (single PNB) to provide the release, the PNB-induced release occurs very quickly, and there is no release if no PNB is generated.

Figure 6.

(a) Relative amplitudes of the residual fluorescence after pump pulse of the liposomes loaded with PE (triangles) and liposomes loaded with NPs and PE (hollow circles) as function of the fluence of the pump laser pulse; (b) Relative amplitudes of the residual fluorescence (hollow circles) and scattering (hollow squires) for the liposomes loaded with NPs and PE as a function of the PNB lifetime.

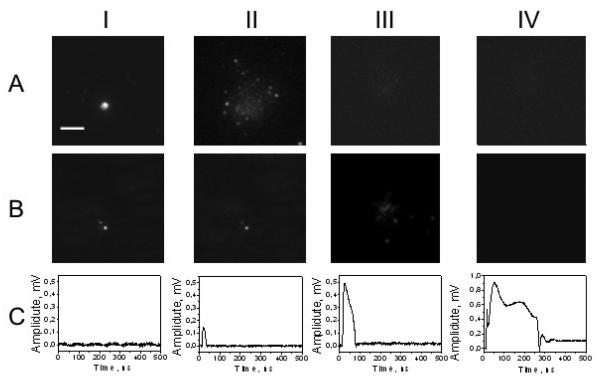

Analysis of the scattering amplitudes at higher fluences has implied that the larger PNB may cause some additional processes besides the release of the fluorescent load. We have compared the fluorescent and scattering images at high levels of the pump laser pulses relative to those obtained previously (Fig. 7). In the range of the laser fluence starting from 150 mJ/cm2 we have observed the ejection of gold NPs out from the liposome (Fig. 7b-III). This effect was associated with the increased lifetime of the PNB (Fig. 7c-III), and also with complete release of the fluorescent load (Fig. 7a-III). Further increase of the pump pulse fluence above 200 mJ/cm2 has caused total destruction of the liposome: it returned “empty” fluorescent and scattering images (Fig. 7a-IV, b-IV). The last case was associated with the largest PNB (Fig. 7c-IV). This response has indicated a change in the baseline level after the termination of the PNB. This could have been caused by the complete physical destruction of the liposome: the baseline signal of the probe laser depends upon optical properties of the medium and we have found that it changes when the object is removed from the beam area. Q19Since we have observed the effect of NP ejection from the liposomes at high laser fluence and this effect was associated with the decrease of the optical scattering amplitude as measured after the NP ejection (Fig. 7b-III vs II) we consider the relative change of the scattering amplitude RS as a measure of its structural integrity. At lower fluences the level of RS did not change so drastically (see Fig. 6b and Fig. 7b-II vs I). However, this property is different from the liposome content: we have shown that the liposome maintained the level of optical scattering (RS did not change as significantly as RF did) after the release of significant part of its fluorescent content (that caused significant decrease of the RF level, compare Fig. 7a-II vs I (fluorescence) and Fig. 7b-II vs I (scattering)). Also, even relatively small PNBs have influence the scattering of the liposomes as can be seen from Fig. 6b. This may be attributed to many parallel processes such as melting and merging of the NPs after the laser pulse, thermal shrinking of the liposome and other processes. Their detailed study was beyond the scope of our work that has been focused on the effect of the PNB on controlled release of chemical cargo from the liposomes. Therefore, we may consider at least three modes of the PNB-induced processes: the tunable release mode (the liposome releases its molecular content depending upon the PNB lifetime); the ejection mode (the liposomes fully releases its molecular content and besides the bigger parts of the liposome are ejected such as nanoparticles), and the destruction mode (besides the release and ejection the liposome itself is totally destroyed by the PNB).

Figure 7.

Q17Optical signals obtained for individual liposomes: (a) –fluorescent images, (b) –optical scattering images, (c) –time responses of optical scattering; (I) liposome with NP before the pump laser pulse, (II)-(IV) 60 s after the generation of single PNB, with increasing fluence of the pump laser pulse: 80 mJ/cm2 (II), 160 mJ/cm2 (III) and 250 mJ/cm2 (IV). Scale bar is 10 μm.

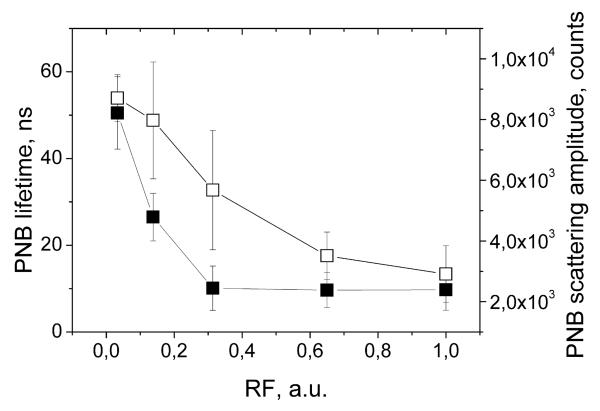

Next, we have analyzed the potential of PNBs for optical guidance of the release. The fluorescent molecules were employed in our experimental model for the purpose of independent analysis of the release process. As we have found previously [22,23], PNB optical properties (optical scattering amplitude of the PNB image along with the amplitude and duration of the PNB time response) correlate to its lifetime. We suggest that the above optical properties of the PNB can be used for quantitative optical guidance of the controlled release without any additional optical probes. We have analyzed two independently measured optical parameters of PNBs (scattering image pixel amplitude and the duration of the time response) as the function of the relative change of the liposome fluorescence (Fig. 8). The both PNB parameters yield good correlation to the release efficacy. Therefore, optical scattering parameters of the PNB, obtained with the one or two probe lasers, can be used to guide the release without any additional probes. This may significantly improve the efficacy and the safety of the release since no potentially toxic fluorescent probes are required and guidance is provide by gold NPs and the locally generated transient PNB.

Figure 8.

Optical parameters of PNB (scattering image pixel amplitude (hollow square) and the duration of time-response (solid square)) as a function of the efficacy of the release of fluorescent molecules from individual liposomes.

4. Conclusions

The above experiments have demonstrated a new mechanism and method for controlled, optically guided release through disruption of the liposome membrane and ejection of the liposome contents with plasmonic nanobubbles. This method relies upon the delivery of optical radiation to the site of the release. For future in vivo applications, there are several possible approaches for the delivery and collection of optical radiation:

- extracorporeal treatment (blood, bone marrow and other liquid tissues) in an optically transparent cuvette;

- surface treatment (superficial tumor, surgery cavities) with an optical fiber probe that can be used for the delivery of the pump and probe laser radiation, and for the collection of the scattered light by the plasmonic nanobubble;

- deep tissue local treatment with penetrating probe (similar to that described above);

- use of a near-infrared pump laser wavelength (instead of visible as we have employed) with better penetration into the tissue and with resonance-matched gold NPs (nanorods and nanoshells).

Plasmonic nanobubble release method has several unique features that were verified and demonstrated above:

- the mechanism of the release is mechanical, nonthermal, fast (millisecond range), local (can be activated in individual liposomes) and tunable (to control the amount of the released load);

- the release agent – a plasmonic nanobubble – is not a particle but a transient on-demand event that combines mechanical and optical properties in one agent, associated with relatively safe gold nanoparticles;

- the release mechanism does not depend upon biochemical and physiological factors that could trigger unintended release.

Furthermore, this mechanism is not limited to liposomes or any specific capsules. The drug (or other molecular load) can be delivered to specific target cells with other PNB methods: by locally disrupting the cellular membrane with extracellular PNBs (generated near cellular plasma membrane and around extracellular plasmonic NPs), injecting the extracellular molecules inside into a cytoplasm, and by disrupting the endosomes (by generating PNBs around endocytosed gold NPs) and delivering endocytosed drugs to cytoplasm and thus overriding one of the most critical barriers for intracellular delivery – endocytotic pathway. By now the PNB method of the liposome disruption has demonstrated reliable and selective mechanism of the release, high speed (in millisecond range) and tunability of the release efficacy.

Acknowledgements

Authors acknowledge support from NIH 1R21CA133641 and from the Institute of International Education/SRF (New York, NY).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lai M, Chang C, Lien Y, Raymond CT. Application of gold nanoparticles to microencapsulation of thioridazine. J. Con. Rel. 2006;111:352–361. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wan WK, Yang L, Padavan DT. Use of degradable and nondegradable nanomaterials for controlled release. Nanomedicine. 2007;2:483–509. doi: 10.2217/17435889.2.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lapotko D. Plasmonic nanoparticle-generated photothermal bubbles and their biomedical applications. Nanomedicine. 2009;4:813–845. doi: 10.2217/nnm.09.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sinha R, Kim GJ, Nie S, Shin DM. Nanotechnology in cancer therapeutics: bioconjugated nanoparticles for drug delivery. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2006;5:1909–1917. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee S-M, Chen H, Dettmer CM, O'Halloran TV, Nguyen ST. Polymer-caged lipsomes: a ph-responsive delivery system with high stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:15096–15097. doi: 10.1021/ja070748i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Angelatos AS, Radt B, Caruso F. Light-responsive polyelectrolyte/gold nanoparticle microcapsules. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2005;109:3071–3076. doi: 10.1021/jp045070x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skirtach AG, Dejugnat C, Braun D, Susha AS, Rogach AL, Parak WJ, Mohwald H, Sukhorukov GB. The role of metal nanoparticles in remote release of encapsulated materials. Nano Lett. 2005;5:1371–1377. doi: 10.1021/nl050693n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paasonen L, Laaksonen T, Johans C, Yliperttula M, Kontturi K, Urtti A. Gold nanoparticles enable selective light-induced contents release from liposomes. J. Con. Rel. 2007;122:86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu G, Mikhailovsky A, Khant HA, Fu C, Chiu W, Zasadzinski JA. Remotely triggered liposome release by near-infrared light absorption via hollow gold nanoshells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:8175–8177. doi: 10.1021/ja802656d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Markowitz MA, Dunn DN, Chow GM, Zhang J. The effect of membrane charge on gold nanoparticle synthesis via surfactant membranes. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1999;210:73–85. doi: 10.1006/jcis.1998.5932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Regev O, Backov R, Faure C. Gold nanoparticles spontaneously generated in onion-type multilamellar vesicles. Bilayers–particle coupling imaged by Cryo-TEM. Chem. Mater. 2004;16:5280–5285. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faure C, Derre A, Neri W. Spontaneous formation of silver nanoparticles in multilamellar vesicles. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2003;107:4738–4746. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park S-H, Oh S-G, Mun J-Y, Han S-S. Loading of gold nanoparticles inside the DPPC bilayers of liposome and their effects on membrane fluidities. Colloids Surf., B Biointerfaces. 2006;48:112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thurston G, McLean JW, Rizen M, Baluk P, Haskell A, Murphy TJ, Hanahan D, McDonald DM. Cationic liposomes target angiogenic endothelial cells in tumors and chronic inflammation in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;101:1401–1413. doi: 10.1172/JCI965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yao CP, Rahmanzadeh R, Endl E, Zhang ZX, Gerdes J, Hüttman G. Elevation of plasma membrane permeability by laser irradiation of selectively bound nanoparticles. J. Biomed. Opt. 2005;10:064012. doi: 10.1117/1.2137321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stevenson D, Agate B, Tsampoula X, Fischer P, Brown CTA, Sibbett W, Riches A, Gunn-Moore F, Dholakia K. Femtosecond optical transfection of cells: viability and efficiency. Opt. Express. 2006;14:7125–7133. doi: 10.1364/oe.14.007125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prentice P, Cuschieri A, Dholakia K, Prausnitz M, Campbell P. Membrane disruption by optically controlled microbubble cavitation. Nature Physics. 2005;1:107–110. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hleb E, Hu Y, Drezek R, Hafner J, Lapotko D. Photothermal bubbles as optical scattering probes for imaging living cells. Nanomedicine. 2008;3:797–812. doi: 10.2217/17435889.3.6.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yavas O, Leiderer P, Park H, Grigoropoulos C, Poon C, Leung W, Do Nhan, Tam AC. Optical reflectance and scattering studies of nucleation and growth of bubbles at a liquid-solid interface induced by pulsed laser heating. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1993;70:1830–1833. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.70.1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zohdy M, Tse C, Ye Jing Yong, O'Donnell M. Optical and acoustic detection of laser-generated microbubbles in single cells. IEEE T. Ultrason. Ferr. 2006;53:117–125. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2006.1588397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marston PL. Light scattering by bubbles in liquids and its applications to physical acoustics. In: Crim LA, et al., editors. Sonochemistry and Sonoluminescence. Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1999. pp. 73–86. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lapotko D. Optical excitation and detection of vapor bubbles around plasmonic nanoparticles. Opt. Express. 2009;17:2538–2556. doi: 10.1364/oe.17.002538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hleb E, Lapotko D. Influence of transient environmental photothermal effects on optical scattering by gold nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 2009;9:2160–2166. doi: 10.1021/nl9007425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin CP, Kelly MW. Cavitation and acoustic emission around laser-heated microparticles. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1998;72:2800–2802. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neumann J, Brinkmann R. Nucleation dynamics around single microabsorbers in water heated by nanosecond laser irradiation. J. Appl. Phys. 2007;101:114701. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vogel A, Noack J, Hüttmann G, Paltauf G. Mechanisms of femtosecond laser nanosurgery of cells and tissues. Appl. Phys. B. 2005;81:1015–1047. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hutson S, Ma X. Plasma and cavitation dynamics during pulsed laser microsurgery in vivo. Phys. Rev. 2007;99:158104. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.99.158104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chanda N, Shukla R, Katti KV, Kannan R. Gastrin releasing protein receptor specific gold nanorods: breast and prostate tumor avid nanovectors for molecular imaging. Nano Lett. 2009;9:1798–1805. doi: 10.1021/nl8037147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farny H, Wu T, Holt RG, Murray TW, Roy RA, A. R. Nucleating cavitation from laser-illuminated nano-particle. Acoust. Res. Lett. Online. 2005;6:138–143. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Debbage P, Jaschke W. Molecular imaging with nanoparticles: giant roles for dwarf actors. Histochem Cell Biol. 2008;130:845–875. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0511-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vogel A, Linz N, Freidank S, Paltauf G. Femtosecond-laser-induced nanocavitation in water: implications for optical breakdown threshold and cell surgery. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008;100:038102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.038102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bryson JM, Fichter KM, Chu W-J, Lee J-H, Li J, McLendon PM, Madsen LA, Reineke TM. Polymer beacons for luminescence and magnetic resonance imaging of DNA delivery. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:16913–16918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904860106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saad M, Garbuzenko OB, Ber E, Chandna P, Khandare JJ, Pozharov VP, Minko T. Receptor targeted polymers, dendrimers, liposomes: which nanocarrier is the most efficient for tumor-specific treatment and imaging? J. Control Release. 2008;130:107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Torchilin VP. Targeted pharmaceutical nanocarriers for cancer therapy and imaging. AAPS J. 2007;9:E128–147. doi: 10.1208/aapsj0902015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khemtong C, Kessinger CW, Gao J. Polymeric nanomedicine for cancer MR imaging and drug delivery. Chem. Commun. (Camb) 2009;24:3497–3510. doi: 10.1039/b821865j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koning GA, Krijger GC. Targeted multifunctional lipid-based nanocarriers for image-guided drug delivery. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2007;7:425–440. doi: 10.2174/187152007781058613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gullotti E, Yeo Y. Extracellularly activated nanocarriers: a new paradigm of tumor targeted drug delivery. Mol. Pharm. 2009;6:1041–1051. doi: 10.1021/mp900090z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bharali DJ, Khalil M, Gurbuz M, Simone TM, Mousa SA. Nanoparticles and cancer therapy: a concise review with emphasis on dendrimers. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2009;4:1–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lewinski N, Colvin V, Drezek R. Cytotoxicity of nanoparticles. Small. 2008;4:26–49. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murphy CJ, Gole AM, Stone JW, Sisco PN, Alkilany AM, Goldsmith EC, Baxter SC. Gold nanoparticles in biology: beyond toxicity to cellular imaging. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:1721–1730. doi: 10.1021/ar800035u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ciani L, Ristori S, Salvati A, Calamai L, Martini G. DOTAP/DOPE and DC-Chol/DOPE lipoplexes for gene delivery: zeta potential measurements and electron spin resonance spectra. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1664:70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lapotko D, Lukianova K, Shnip A. Photothermal responses of individual cells. J. Biomed. Opt. 2005;10:014006. doi: 10.1117/1.1854685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lapotko D, Lukianova E, Potapnev M, Aleinikova O, Oraevsky A. Method of laser activated nanothermolysis for elimination of tumor cells. Cancer Lett. 2006;239:36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hleb EY, Hafner JH, Myers JN, Hanna EY, Rostro BC, Zhdanok SA, Lapotko DO. LANTCET: elimination of solid tumor cells with photothermal bubbles generated around clusters of gold nanoparticles. Nanomedicine. 2008;3:647–667. doi: 10.2217/17435889.3.5.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lapotko D. Pulsed photothermal heating of the media during bubble generation around gold nanoparticles. Intern. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2009;52:1540–1543. [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Leeuwen TG, Jansen ED, Motamedi M, Welch AJ, Borst C. Excimer laser ablation of soft tissue: a study of the content of rapidly expanding and collapsing bubbles. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 1994;30:1339–1345. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rayleigh L. On the pressure developed in a liquid during the collapse of a spherical cavity. Philos. Mag. 1917;34:94–98. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brennen CE. Cavitation and bubble dynamics. Oxford University Press; Oxford Engineering Science, NY: 1995. p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lapotko D, Lukianova K. Laser-induced micro-bubbles in cells. Intern. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2005;48:227–234. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hleb E, Lapotko D. Photothermal properties of gold nanoparticles under exposure to high optical energies. Nanotechnology. 2008;19:355702. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/19/35/355702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]