Abstract

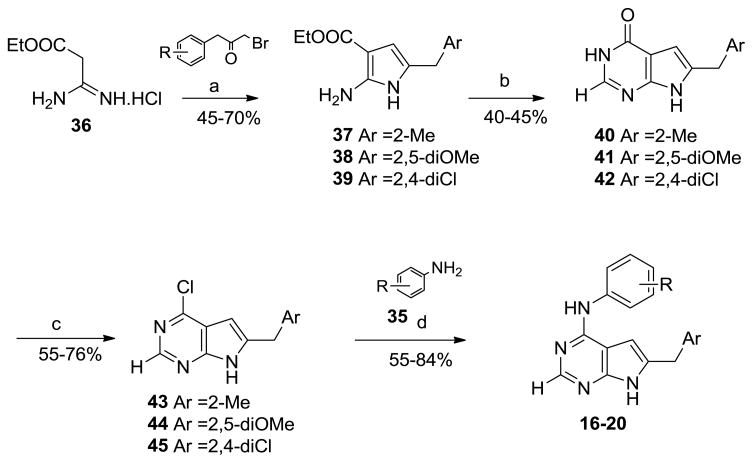

A series of eight N4-phenylsubstituted-6-(2,4-dichlorophenylmethyl)-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine-2,4-diamines 8–15 were synthesized as vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR-2) inhibitors with varied substitutions in the phenyl ring of the 4-anilino moiety. In addition, five N4-phenylsubstituted-6-phenylmethylsubstituted-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-4-amines 16–20 were synthesized to evaluate the importance of the 2-NH2 moiety for multiple receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) inhibition. Cyclocondensation of α-halomethylbenzylketones with 2,6-diamino-4-hydroxypyrimidine afforded 2-amino-6-(2,4-dichlorophenylmethyl)-3,7-dihydro-4H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-4-one, 23 and reaction of α-bromomethylbenzylketones with ethylamidinoacetate followed by cyclocondensation with formamide afforded the 6- phenylmethylsubstituted-3,7-dihydro-4H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-4-ones, 40–42 respectively. Chlorination of the 4-position and displacement with appropriate anilines afforded the target compounds 8–20. Compounds 8, 10 and 14 were potent VEGFR-2 inhibitors and were 100-fold, 40-fold and 8-fold more potent than the standard semaxanib, respectively. Previously synthesized multiple RTK inhibitor, 5 and the VEGFR-2 inhibitor 8 from this study, were chosen for further evaluation in a mouse orthotopic model of melanoma and showed significant inhibition of tumor growth, angiogenesis and metastasis.

Keywords: Pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines; Receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors; Antiangiogenic agents; Antitumor agents

Introduction

Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) and platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) have important functions in signal transduction pathways that regulate cell proliferation, differentiation and growth under normal cell function, as well as under abnormal conditions.1,2 RTKs are overexpressed in several tumors and are associated with aberrant signaling leading to increased angiogenesis, tumor cell proliferation and metastasis. 1,2

Angiogenesis is the growth of new blood vessels from existing vasculature.3 Physiological angiogenesis occurs during wound healing, the menstrual cycle and pregnancy, and produces well ordered vascular structures with mature, functional blood vessels.3,4 Pathological angiogenesis is associated with tumor growth and several diseases such as psoriasis, diabetic retinopathies and endometriosis.3 Angiogenesis is crucial for the sustained growth of tumors. The new blood vessels provide nutrients and oxygen for tumor proliferation, and also a route for metastasis. In addition to providing tumors with oxygen and nutrients through angiogenesis, activated endothelial cells release growth factors such as platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) that on binding to the growth factor receptors activate RTKs that both maintain the endothelial cell activation and stimulate tumor cell growth.3–6

Thus, inhibition of tumor angiogenesis offers a therapeutic strategy for treating a variety of cancers. Antiangiogenic agents are usually cytostatic and prevent the growth of the tumor but are not usually tumoricidal and are much more successful in cancer chemotherapy when combined with cytotoxic agents.4–6 Among the RTKs implicated in tumor progression are members of the VEGFR family that include VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2, members of the EGFR family and members of the PDGFR family namely PDGFR-α and PDGFR-β.7,8

Angiogenesis is facilitated by a number of growth factor receptors of which VEGFR-2 is the key.5,9–11 VEGF stimulation is sufficient to induce tumor growth and metastases. Inhibition of VEGFR-2 leads to an inhibition of angiogenesis, decreased vascular permeability and decreased endothelial cell survival.11

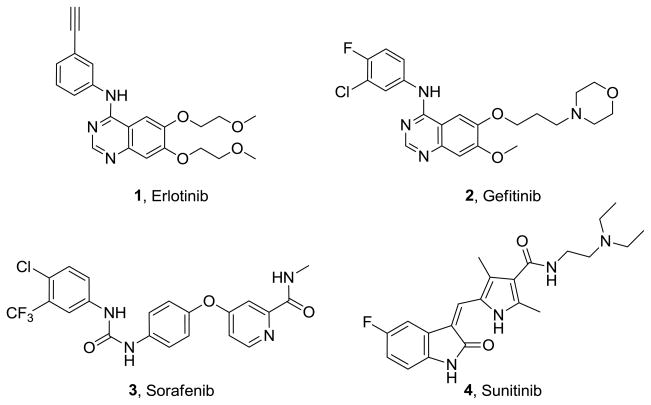

Several small molecule inhibitors of RTKs that target the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) binding site of tyrosine kinases are in clinical use and several others are in clinical trials as antitumor agents.1,2,12 Initial strategies for RTK inhibition focused on single RTK inhibitors such as erlotinib, 1 and gefitinib, 2 (Figure 1) that were approved for non small cell lung cancer.12,13 However, tumors have redundant signaling pathways for angiogenesis and often develop resistance to agents that target one specific pathway.14,15 A multifaceted approach that targets multiple signaling pathways has shown to be more effective than the inhibition of a single target due to the probable synergism/potentiation/additive effects that could lower the drug dose required.16–20 Multiple RTK inhibitors, sorafenib, 3 (Figure 1) an inhibitor of VEGFR, PDGFR and Raf-1 kinase and sunitinib, 4 (Figure 1) an inhibitor of VEGFR-1, VEGFR-2, fms-like tyrosine kinase-3 (Flt-3), PDGFR, stem cell factor receptor (c-Kit) and colony stimulating factor receptor (cFMS) have been approved for renal cell carcinoma.21,22 These two RTK inhibitors are in clinical evaluation alone and in combination with other agents against a variety of cancers. However, multiple RTK inhibitors are in some instances more prone to yield side effects than selective RTK inhibitors.24–26 Protein kinases share very similar structural features, which are often responsible for cross-reactivities in various kinases, producing the undesirable side efects.24 For example, the approved multiple RTK inhibitors sorafenib and sunitinib have been reported to be cardiotoxic.25,26 Thus, specific inhibitors of VEGFR-2 or other RTKs would also be of considerable interest.

Figure 1.

Gangjee et al.27 previously reported compounds 5–7 (Figure 2) as multiple RTK inhibitors in a series of N4-(3-bromophenyl)-6-phenylmethylsubstituted-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine-2,4-diamines. Compound 5 was a potent VEGFR-2 inhibitor and demonstrated A431 cytotoxicity and moderate EGFR inhibition in the cellular assays.27 Compound 6 was a potent VEGFR-2 inhibitor and a moderate PDGFRβ and VEGFR-1 inhibitor.27 In the previously reported series, the 6-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)methyl substituted compound 7, was a potent EGFR inhibitor, with poor VEGFR-2 inhibition.27 Since VEGFR-2 has been implicated as the principal mediator of angiogenesis5,9–11 and VEGFR-2 stimulation alone is sufficient to induce tumor growth and metastases,11 it was of interest to structurally design VEGFR-2 inhibition in the 6-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)methyl pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine scaffold of compound 7, to afford either a dual EGFR/VEGFR-2 inhibitor or perhaps a selective VEGFR-2 inhibitor.

Figure 2.

In order to design VEGFR-2 inhibitory activity into compound 7, various anilino substitutions were explored in compounds 8–15. These anilino substitutions were selected on the basis of the potent VEGFR-228–31 and EGFR32–33 inhibition reported for similar anilino substitutions in 6-6 fused scaffolds such as quinazolines, pthalazines and pyrido[2,3-d]pyrimidines. Small, lipophilic, electron-deficient substitutions at the ortho-position of the 4-anilino ring combined with a larger, lipophilic, electron withdrawing moiety at the para-position such as chlorine or bromine have provided potent VEGFR-2 inhibition in quinazolines.30,31 Thus, compounds 8, with the 2-chloro, 4-bromo anilino moiety and 9, with the 2-fluoro, 4-chloro aniline moiety were synthesized.

Small substitutions at the meta position of the anilino ring such as a 3-hydroxy and a 3-trifluoromethyl have also been reported to afford potent VEGFR-2 and EGFR inhibition,28–31 while larger, electron withdrawing substitutions such as 3-bromo and 3-chloro are preferred for EGFR inhibition in bicyclic 6-6 fused scaffolds.32,33 In order to improve the potency of VEGFR-2 inhibition and perhaps provide an optimal combination for VEGFR-2 and EGFR inhibition in the target compounds, we elected to substitute the phenyl ring of the anilino moiety at the 3-position with small, lipophilic, electron withdrawing substituents such as the 3-fluoro in 10, 3-trifluoromethyl in 11 and 3-ethynyl in 12.

Disubstitution at the 2,4- and 3,4- position of the anilino derivatives have also shown good inhibitory activities against VEGFR-2, while retaining moderate EGFR inhibition.30,31 In addition, these substitutions showed a preference for VEGFR-2 and EGFR over PDGFR and other kinases has been reported (VEGFR> EGFR >PDGFR, FGFR, IGF-1R).30,31 Thus, in addition to the 2,4-disubstituted compounds 8 and 9, the 3,4-disubstituted derivative 13 with a 3-fluoro, 4-trifluoromethyl anilino was also synthesized.

Bulky groups at the para-position which include electron donating alkyl groups and electron withdrawing substitutions such as halogens and aryl substitutions have also been reported to be conducive for potent VEGFR-2 inhibition,28,29,34,35 thus the 4-isopropyl aniline derivative 14 was synthesized. Its regioisomer, 15 was synthesized to restrict the conformation of the anilino ring with respect to the pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine scaffold and thereby determine its effect on RTK inhibition.

The 2-NH2 moiety of compound 727 was maintained in compounds 8–15 to provide an additional hydrogen bond in the Hinge region of RTKs compared to other known RTK inhibitors that lack this 2-NH2 moiety. The flexible 6-(2,4-dichlorobenzyl) substitution was maintained to allow for multiple conformations of the sidechain and as a result, perhaps afford interactions with two or more RTKs.

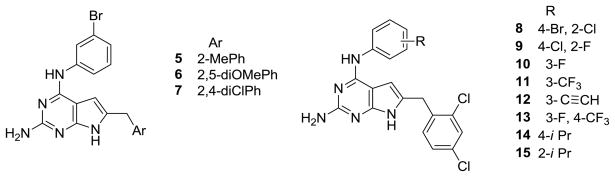

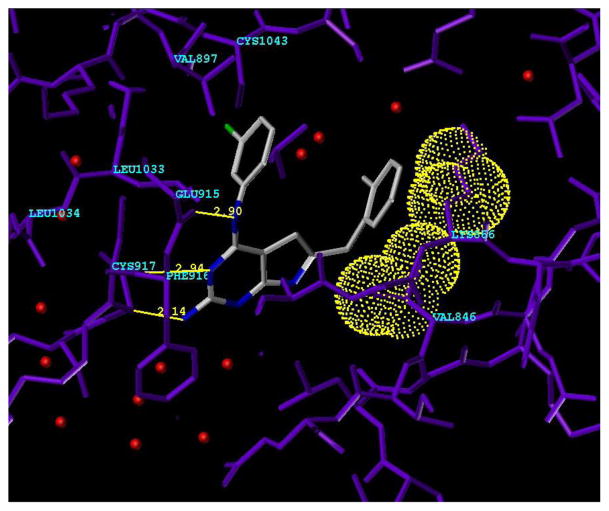

Molecular modeling using SYBYL 7.034 showed two possible modes of binding of 5 to VEGFR-2. The first or Mode 1 is shown in Figure 3. Compound 5 was energy minimized (Minimize and Search Option in SYBYL 7.0) and superimposed onto the crystal structure of a furo[2,3-d]pyrimidine in VEGFR-2 (PDB: 1YWN) 35,36 (Figure 3). In this model, the pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine occupies the adenine region of the ATP binding site. The N3 of the pyrimidine in 5 is hydrogen bonded to the backbone NH of Cys917 and the aniline NH is hydrogen bonded to the backbone carbonyl of Glu915. An additional hydrogen bond between the backbone carbonyl of Cys917 and the 2-NH2 on the pyrimidine ring of 5 is not observed in ATP or the reported furo[2,3-d]pyrimidine.35,36 These hydrogen bond interactions serve to anchor the heterocyclic portion of the molecule to VEGFR-2 and appropriately orient the other parts of the molecule in the ATP binding site.

Figure 3.

Compound 5 in Mode 1 in VEGFR-2 (PDB code: 1YWN) showing the key interactions. Hydrogen bonding in the Hinge region between the 2-NH2 and the backbone carbonyl of Cys917, N3 and NH of Cys917 and 4-anilino NH and backbone carbonyl of Glu915. Hydrophobic interactions between the 4-anilino phenyl ring and Val897 and Cys1043 are indicated. Hydrophobic interactions between the 6-benzyl ring and Val846 and carbon chain of Lys866 (shown in dotted van der Waals surface for VEGFR-2).

Compound 5 in Mode 1 in VEGFR-2 (PDB code: 1YWN) showing the key interactions. Hydrogen bonding in the Hinge region between the 2-NH2 and the backbone carbonyl of Cys917, N3 and NH of Cys917 and 4-anilino NH and backbone carbonyl of Glu915. Hydrophobic interactions between the 4-anilino phenyl ring and Val897 and Cys1043 are indicated. Hydrophobic interactions between the 6-benzyl ring and Val846 and carbon chain of Lys866 (shown in dotted van der Waals surface for VEGFR-2).

Compound 5 in Mode 2 in VEGFR-2 (PDB code: 1YWN) showing hydrogen bonding in the Hinge region between the 2-NH2 and the backbone carbonyl of Cys917, N3 and NH of Cys917 and pyrrolo NH and backbone carbonyl of Glu915.

An alternate mode of binding or Mode 2 (Figure 4), is obtained from Mode 1 by rotating the C2–NH2 bond by 180°. Mode 2 has the 4-anilino moiety binding in the Sugar pocket rather than in the Hydrophobic region as in Mode 1. In Mode 2, the 7-position pyrrolo NH mimics the anilino NH of Mode 1 and forms one of the H-bonds with the Hinge region, substituting for the 4-NH of ATP; the N1-nitrogen forms the second H-bond and mimics the N3-nitrogen of Mode 1 and ATP.

Figure 4.

Compound 5 in Mode 2 in VEGFR-2 (PDB code: 1YWN) showing hydrogen bonding in the Hinge region between the 2-NH2 and the backbone carbonyl of Cys917, N3 and NH of Cys917 and pyrrolo NH and backbone carbonyl of Glu915.

Thus, molecular modeling provided credence to our hypothesis of the possible binding modes of our target compounds 8–15 to VEGFR-2, similar to that shown for 5. An additional aspect of our work was to evaluate the role of the 2-NH2 moiety for RTK inhibition. The 2-NH2 moiety was originally incorporated in our design27 of pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines on the basis of molecular modeling as shown in Figures 3 and 4 to afford an additional hydrogen bond in the Hinge region of RTKs compared to most of the known 6-6 and 6-5 bicyclic pyrido[2,3-d]pyrimidines, quinazolines and furo[2,3-d]pyrimidines that lack the 2-NH2 moiety.28–33,34

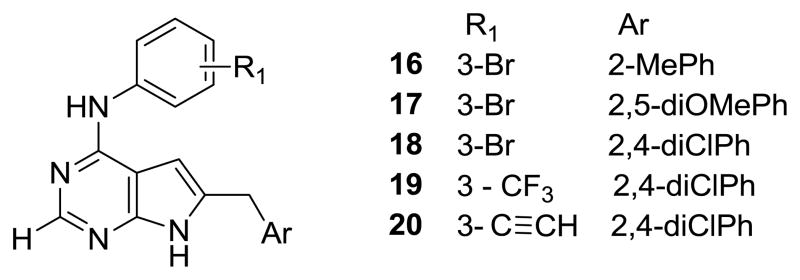

In order to specifically demonstrate that the 2-NH2 moiety does indeed contribute to an increase in the potency of the 6-phenylmethylsubstituted-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-2,4-diamines, it was necessary to synthesize pairs of analogs with and without the 2-NH2 group. Thus, N4-phenylsubstituted-6-phenylmethylsubstituted-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-4-amines, 16–20 (Figure 5) were synthesized as the 2-des NH2 analogs of 5, 6, 7, 11 and 12 respectively.

Figure 5.

Chemistry

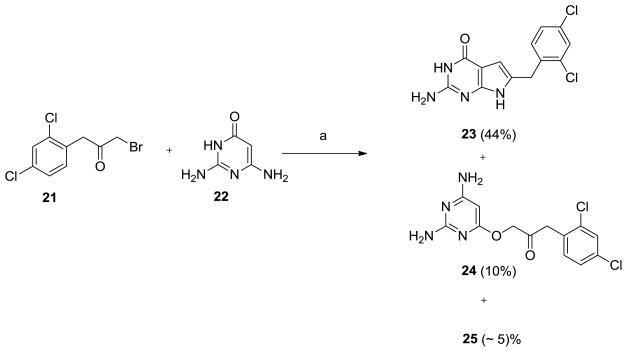

The key intermediate in the synthesis of 8–15 was the 6-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)methyl-3,7-dihydro-4H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-4-one 23 (Scheme 1). Several methods have been published for the synthesis of 6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines.27,37–43 We27 previously synthesized 23 by utilizing the method reported by Secrist and Liu37 that involved the reaction of α-bromomethylbenzylketones with 2,6-diamino-4-oxopyrimidine, 22. Secrist and Liu37 reported the regiospecific formation of 6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines in the reaction of α-bromomethylketones with 22 in DMF. These authors also reported a mixture of the 6-substituted-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines and the 5-substituted-furo[2,3-d]pyrimidines by the reaction of α-chloromethylketones with 22 in DMF. In subsequent reports, Gangjee et al.38 reported the reaction of 3-bromo-4-piperidone hydrobromide with 22 to afford only the tricyclic tetrahydropyrido annulated-2,4-diaminofuro[2,3-d]pyrimidine. Secrist and Liu27 had also reported the formation of furo[2,3-d]pyrimidines exclusively with cyclic α-chloromethylketones.

Scheme 1.

aReagents and Conditions: (a) DMF, r.t., 3 days

We repeated the reported methodology to obtain 23 as described previously.27 Careful scrutiny of the TLC for the reaction of α-bromomethyl-(2,4-dichlorobenzyl)ketone, 21 with 22 revealed three spots [TLC Rf 0.57, 0.60, 0.65 (CHCl3/CH3OH, 5:1)]. Two of the products, 23 and 24 were separated by column chromatography, however the third product, 25 (<5 % yield) could not be separated from 24. The 6-(2,4-dichlorobenzyl)-3,7-dihydro-4H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-4-one, 23 (Rf 0.57) was the major product, isolated in 44% yield. The Rf and the 1H NMR for the minor products were distinct from the starting materials 21 and 22 and the product 23. 1H NMR for one of the minor products, 24 (Rf 0.60), showed two D2O exchangeable peaks at 5.91 ppm and 6.12 ppm that integrated for two protons each and were assigned to the 2,4-diNH2 of 24. A singlet at 5.13 ppm that integrated for one proton was assigned to the C5-H of the pyrimidine. In addition, two singlets that integrated for two protons each at 4.85 ppm and 4.00 ppm and aromatic peaks at 7.37–7.58 ppm were also observed. These proton positions and their integration along with the HRMS confirmed the structure to be the monocyclic 2,4-diamino-6-substituted pyrimidine 24 (Scheme 2). Compound 24 is most likely formed by the attack of the 4-hydroxy group of 22 on the halogen of the α-bromomethylbenzylketone, 21 and could be an intermediate in the pathway toward the 2,4-diamino-5-substituted furo[2,3-d]pyrimidine, a by product isolated in previous reports.37

Scheme 2.

aReagents and Conditions: (a) conc HCl, 1 h, 70–80 °C; (b) 21, NaOAc, H2O, 12 h, 100 °C; (c) Piv2O, 2 h, 120 °C; (d) POCl3, 3 h, reflux; (e) 35, iPrOH, 2–3 drops conc HCl, 16–48 h, reflux; (f) 35, iPrOH, 2–3 drops conc HCl, microwave, 45 mins

The above method for 23 involved the formation of additional side products, moderate yields, prolonged reaction times and required purification by column chromatography. We attempted an alternate method for the synthesis of 23. The regiospecific synthesis of 6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines by the reaction of α–chloromethylbenzylketones with 22 in sodium acetate and water at reflux has been previously reported by Gangjee et al.39–42 and other groups.43 We attempted this method (Scheme 2) for the synthesis of 6-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)methyl-3,7-dihydro-4H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-4-one 23 based on the shorter reaction time (6–12 h vs 72 h) and significantly improved yields for the pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines, without the formation of any furo[2,3-d]pyrimidines or byproducts.39–43

The appropriate chloroketones 28 and 29 were synthesized by treating the appropriate diazoketones 2627 and 2727 with conc HCl at reflux (Scheme 2). The chloroketones 28 and 29 were treated with 22, NaOAc and water at reflux to afford 23 and 30 respectively in 65–70% yield. Chlorination of 23 proceeded in poor yields, hence, 23 was first pivaloylated at the 2-NH2 moiety followed by chlorination and treatment with appropriate aniline to the target compounds 8–15 as described in Scheme 2. Prolonged reflux (16–48 h) of the 4-chloro intermediates 33 and 34 with the appropriate anilines in isopropanol and a few drops of conc HCl resulted in displacement of the 4-chloro with the aniline and simultaneous depivaloylation to afford the target compounds 8, 9, 12 and 14. Reaction with the anilines in isopropanol and 2–3 drops of conc HCl in the microwave reactor (Emrys Liberator microwave synthesizer, Biotage Inc.) for 45 min at 120 °C afforded compounds 10, 11 and 13 respectively.

Based on the potent RTK inhibiton seen for the previously reported 5, we resynthesized 5 in larger quantities for an in vivo assay as described in Scheme 2. The 2-NH2 moiety in 30 was first pivaloylated to 32 and then chlorinated with POCl3 to afford N-[4-chloro-6-(2-methylbenzyl)-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-2-yl]-2,2-dimethylpropanamide, 34 in 55% yield compared to the 4-chloro-6-(2-methylbenzyl)-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine-2-amine27 that was previously reported in 28% yield. Nucleophilic displacement of the 4-chloro in 34 with 3-bromoaniline and simultaneous depivaloylation on prolonged reflux afforded 5.

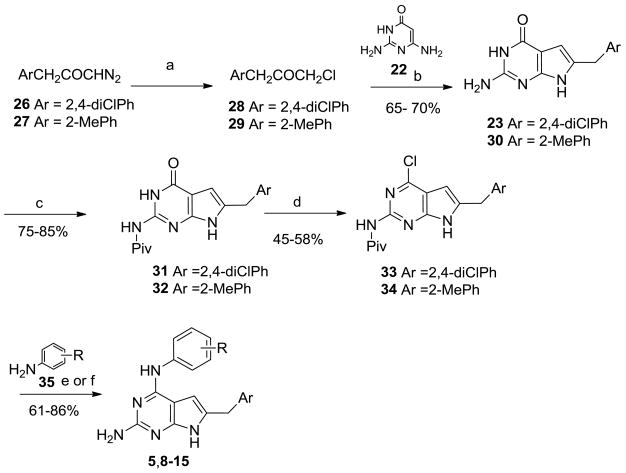

The 2-des NH2 compounds 16–20 (Figure 5) were synthesized (Scheme 3), somewhat differently from 8–15. Reaction of bromoacetone with ethylamidinoacetate, 3645 to afford the corresponding pyrroles, followed by cyclization with formamide to the corresponding pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines, has been reported in the literature.44–46 We modified this procedure for the synthesis of 16–20. The appropriate α-bromomethylbenzylketones with 32 at reflux afforded the appropriately substituted pyrroles 37–39 which were heated with formamide to afford the 6-substitutedphenylmethyl-3,7-dihydro-4H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-4-ones, 40–42. Compounds 40–42 were chlorinated with POCl3 to 43–45 and subsequent treatment with the appropriate anilines, 35 afforded the target compounds 16–20.

Scheme 3.

aReagents and Conditions: (a) α-bromobenzylketones, EtOAc, NEt3, N2, 15 mins, r.t. then 30 mins, (b) formamide, Na/MeOH, 8 h, 120 °C; (c) POCl3, 3 h, reflux; (d) 35, iPrOH, 2–3 drops conc HCl, 4.

Biological Evaluation and Discussion

Compounds 8–20 were evaluated as RTK inhibitors using human tumor cells known to express high levels of EGFR, VEGFR-2, VEGFR-1 and PDFGR-β using a phosphotyrosine ELISA cytoblot (Table 1).47 Whole cell assays were used for RTK inhibitory activity since these assays afford more meaningful results for translation to in vivo studies. The effect of compounds on cell proliferation was measured using A431 cancer cells, known to overexpress EGFR. EGFR is known to play a role in the overall survival of A431 cells.47

Table 1.

IC50 values (μM) of kinase inhibition and A431 cytotoxicity for compounds 7–15.

| VEGFR-2 | EGFR | VEGFR-1 | PDGFR-β | A431 cyto toxicity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7a | 28.1 ± 9.9 | 0.2 ± 0.06 | >50 | 17.0 ± 5.6 | 2.8 ± 1.1 |

| 8 | 0.1 ± 0.3 | >300 | >300 | >300 | 16.2 ± 2.5 |

| 9 | 45.7 ± 6.4 | 2.5 ± 0.09 | 70.9 ± 9.1 | 24.6 ± 4.1 | 4.9 ± 0.51 |

| 10 | 0.3 ± 0.04 | 161.6 ± 25.3 | 162.9 | 183.1 ± 30.2 | 45.2 ± 7.2 |

| 11 | >300 | 27.2 ± 3.1 | 156.1 ± 29.1 | >300 | 195.2 ± 28.8 |

| 12 | 85.6 ± 12.2 | 55.2 ± 7.1 | >300 | >300 | 9.5 ± 0.09 |

| 13 | 113.1 ± 21.1 | 91.7 ± 29.3 | >300 | >300 | 13.8 ± 2.5 |

| 14 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 45.6 ± 13.2 | 157 ± 22.3 | 174.9 ± 27.3 | 26.2 ± 4.0 |

| 15 | >300 | 96.4 ± 14.9 | 163.1 ± 27.9 | 43.0 ± 9.4 | 160.2 ± 25.6 |

| 46 | 12.0 ± 2.7 | ||||

| 47 | 10.6 ± 2.9 | ||||

| 48 | 14.1 ± 2.8 | ||||

| 49 | 0.2 ± 0.04 | ||||

| 50 | 3.7 ± 0.06 | ||||

| 1 | 124.7 ± 18.2 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 83.1 ± 10.1 | ||

| 4 | 18.9 ± 2.7 | 172.1 ± 19.4 | 12.2 ± 1.9 |

IC50 values from reference 27.

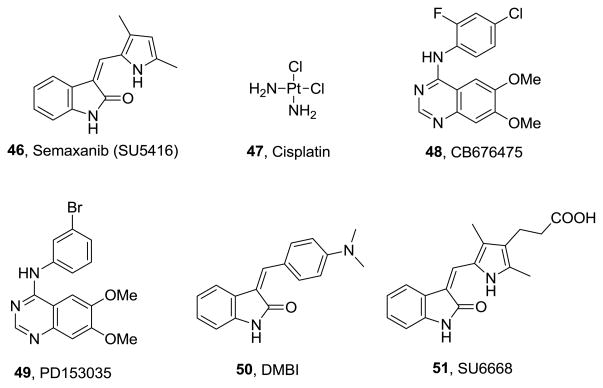

Since the IC50 values of compounds vary under different assay conditions (eg. ATP concentrations), standard compounds (Figure 6) were used as controls in each of the evaluations. The standard compounds used were semaxanib (SU5416), 46 for VEGFR-2;48 cisplatin, 47 for A431 cytoxicity, (4-chloro-2-fluorophenyl)-6,7-dimethoxyquinazolin-4-yl-amine (CB676475), 48 for VEGFR-1;32 4-[(3-bromophenyl)amino]-6,7-dimethoxyquinazoline (PD153035), 49 for EGFR;31 and 3-(4-dimethylamino-benzylidenyl)-2-indolinone (DMBI), 50 for PDGFR-β.49 In addition, FDA approved receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors erlotinib, 1 and sunitinib, 4 were also incorporated for a comparison in the in vitro study against EGFR, VEGFR-2 and PDGFR-β kinases. Sunitinib, 4 displayed two digit micromolar inhibitions of VEGFR-2 and PDGFR-β while erlotinib displayed single digit micromolar inhibition of EGFR. The inhibitory potencies (IC50 values) of 8–15 are compared with the previously synthesized compound 727 (Figure 1) and the standard compounds 1, 4, 46–50 in Table 1.

Figure 6.

VEGFR-2

Previously synthesized compound 7 did not show significant VEGFR-2 inhibition and was less potent than semaxanib in the cellular assay. Compounds 8, 10 and 14 of this series showed inhibition of VEGFR-2 that was more potent than the standards, semaxanib 46 and sunitinib 4. In the disubstituted anilino derivatives, compound 8 with the 2-chloro, 4-bromo anilino substitution was 100-fold more potent than semaxanib. However, the 2-fluoro, 4-chloro anilino derivative 9 and the 3-fluoro, 4-trifluoromethyl anilino derivative 13 did not inhibit VEGFR-2. VEGFR-2 inhibition also improved in the 3-substituted anilino derivatives, when the 3-bromo in 7 was replaced with a 3-fluoro in 10. Compound 10 was 40-fold better than semaxanib, 46. VEGFR-2 inhibition decreased significantly with variations to the 3-ethynyl in 12 and was abolished on variation to the 3-trifluoromethyl in 11. The 4-isopropyl substitution in 14, however provided potent VEGFR-2 inhibition that was 8-fold more potent than semaxanib, 46 while the 2-isopropyl substitution in 15 abrogated VEGFR-2 inhibition.

EGFR

In the 6-(2,4-dichlorophenylmethyl)substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines, compound 7 was a potent EGFR inhibitor. EGFR inhibition significantly decreased or was abolished on variation of the 3-bromo anilino substitution in 7 to other anilino moieties in 8–15. Compound 9 with the 2-fluoro, 4-chloro anilino substitution was the most potent EGFR inhibitor in this series of compounds, although EGFR inhibition decreased by 10-fold in 9 compared to 7 and the standard 49 (PD153035).

VEGFR-1

Compounds 8–15 and the lead compound 7 were inactive against VEGFR-1. Compound 9 with the 2-fluoro, 4-chloro anilino substitution was the best and was 5-fold less active than the standard 48 (CB676475).

PDGFR-β

Compound 7 showed two-digit micromolar inhibition of PDGFR-β and was less potent than the standard 50 (DMBI) and sunitinib, 4. Analogs 8–15 also showed diminished activity compared to 50 however compounds 9 and 15 retained two-digit micromolar inhibition as seen in the lead compound 7 and were 6.5-fold and 11.5-fold less potent than 50 respectively. Compounds 9 and 15 were approximately 2-fold and 4-fold less potent than the standard compound 4.

A431 cytotoxicity

Compound 7 showed potent inhibition in the A431 cytotoxicity assay and was more potent than the standard, cisplatin. All three disubstituted anilino compounds 8, 9 and 13 showed potent A431 cytotoxicity, more potent or equipotent with cisplatin, but slightly less potent than compound 7. The IC50 value for compound 9 was 1.7-fold less potent than the lead compound 7. The 3-ethynylsubstituted anilino derivative, 12 also showed single digit micromolar inhibitory activities in the A431 cytoxicity assay and was almost equipotent with cisplatin and approximately 3-fold less potent than 7. Interestingly, compounds 8, 12 and 13 showed reasonably potent A431 cytoxicities although they did not show significant EGFR inhibition. The A431 cell lines depend on EGFR for survival; perhaps these compounds do not directly inhibit EGFR but influence the downstream signaling of EGFR and crosstalk with other kinases which may be necessary for EGFR function. The literature contains several similar reports in which the EGFR inhibitory activity does not necessarily translate into A431 cytotoxicity.31,34

Multiple RTK inhibition

Compounds 8, 10 and 14 were the most potent VEGFR-2 inhibitors of this study. The improvement in VEGFR-2 inhibition for 8, 10 and 14 was obtained with a simultaneous decline in EGFR inhibition. Compound 9 retained moderate, dual EGFR and VEGFR-2 inhibition, and was 3.8-fold less potent than the semaxanib, 46 against VEGFR-2 and 10-fold less potent than the standard compound 49 (PD153035) against EGFR. Compound 9 also showed moderate VEGFR-1 inhibition and was 5-fold less potent than the standard 48 (CB676475). The 3-ethynyl substitution present in 12 was derived from the quinazoline-derived EGFR inhibitor, erlotinib, 1.12,32,33 Compound 12 however, did not show EGFR inhibition. This indicates that the scaffold that holds the anilino moiety is also important for specificity of inhibition of an RTK.

Since the inhibitory activities are determined in cells, it is not possible to make a definite structure–activity relationship for compounds 8–15 and RTK inhibition. However, the cellular assays discussed above clearly indicate that variation in the phenyl substitution of the anilino moiety does indeed control the potency and specificity of RTK inhibition. Since some anilino substitutions in 8–15 do not follow RTK inhibitory profiles observed for the 6-6 fused scaffolds, the optimal substitution pattern on the anilino moiety needs to be determined individually for each of the various scaffolds showing RTK inhibition.

A comparison of the RTK inhibitory activities and A431 cytotoxicity for the 2-NH2 substituted compounds 5–7 and 14–15 with their 2-des NH2 analogs 16–20 respectively is provided in Table 2, along with the standards.

Table 2.

IC50 values (μM) of kinase inhibition and A431 cytotoxicity for compounds 5–7 and 11–12 and 16–20.

| VEGFR-2 | EGFR | VEGFR-1 | PDGFR-β | A431 cytotoxicity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5a | 0.2 ± 0.04 | 9.1 ± 1.8 | >50 | >50 | 1.2 ± 0.4 |

| 6a | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 12.6 ± 3.3 | 31.1 ± 5.8 | 8.9 ± 1.6 | >50 |

| 7a | 28.1 ± 9.9 | 0.2 ± 0.06 | >50 | 17.0 ± 5.6 | 2.8 ± 1.1 |

| 11 | >300 | 27.2 ± 3.1 | 156.1 ± 29.1 | >300 | 195.2 ± 28.8 |

| 12 | 85.6 | 55.2 ± 7.1 | >300 | >300 | 9.5 ± 0.09 |

| 16 | 27.2 ± 4.2 | >300 | >300 | 182.0 ± 31.3 | 191.3 ± 30.2 |

| 17 | >300 | >300 | >300 | 171.3 ± 31.6 | 4.5 ± 1.7 |

| 18 | >300 | >300 | 150.9 ± 27.4 | 220.4 ± 33.4 | >300 |

| 19 | >300 | 33.1 ± 5.3 | >300 | 110.1 ± 31.1 | >300 |

| 20 | >300 | >300 | >300 | 142.2 ± 34.1 | 198.1 ± 31.2 |

| 46 | 12.0 ± 2.7 | ||||

| 47 | 10.6 ± 2.9 | ||||

| 48 | 14.1 ± 2.8 | ||||

| 49 | 0.2 ± 0.04 | ||||

| 50 | 3.7 ± 0.06 | ||||

| 1 | 124.7 ± 18.2 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 83.1 ± 10.1 | ||

| 4 | 18.9 ± 2.7 | 172.1 ± 19.4 | 12.2 ± 1.9 |

IC50 values from reference 27.

VEGFR-2

The 2-NH2 substituted compounds 5 and 6 showed potent submicromolar inhibition of VEGFR-2. The corresponding 2-des NH2 analogs 16 and 17 were 108-fold and >300-fold less potent than 5 and 6 respectively, and were 2-fold and >16-fold less potent than the standard, semaxanib 46. The 2-NH2 substituted compounds 7, 11 and 12 did not show potent inhibition of VEGFR-2. The VEGFR-2 inhibition further decreased for the corresponding 2-des NH2 analogs 18, 19 and 20 respectively.

EGFR

The 2-des NH2 compounds 16–20 showed poor inhibitory potencies against EGFR, compared to the 2-NH2 substituted compounds 5–7 and 11 and 12 and the standard compound 49 (PD1530305).

VEGFR-1

The 2-NH2 substituted compound 6 showed moderate VEGFR-1 inhibition, approximately 2-fold less potent than the standard 48. The corresponding 2-des NH2 analog 17 was > 6-fold less potent than 6 and > 14-fold less potent than the standard 48. VEGFR-1 inhibition did not improve for the 2-des NH2 analogs 16, 18, 19 and 20 compared to the 2-NH2 substituted compounds 5, 7, 11 and 12 respectively and also compared to the standard, 48 (CB676475).

PDGFR-β

The PDGFR-β inhibition did not improve for the 2-des NH2 analogs 16–20 compared to the 2-NH2 substituted compounds 5–7, 11 and 12 respectively.

A431 cytotoxicity

The 2-NH2 substituted compounds 5, 7 and 12 showed potent A431 cytotoxicity being more potent or equipotent to the standard, cisplatin. The A431 cytotoxicity significantly decreased for the corresponding 2-des NH2 analogs 16, 18 and 20 compared to 5, 7 and 12 respectively, and compared to cisplatin. The A431 cytotoxicity improved for the 2-des NH2 analog 17 compared to 6 and cisplatin, 47.

A consistent decrease in RTK inhibition in whole cells was observed for the 2-des NH2 compounds, 16–20, with the exception of the potent inhibition seen in the A431 cytotoxicity assay for 17. The study of the 2-NH2 substituted compounds and their corresponding 2-des NH2 analogs confirms our original hypothesis that a 2-NH2 should provide additional hydrogen bonding interactions that translates into improved inhibition for RTK and A431 cytotoxicity for the 2-NH2 substituted compounds compared to their 2-des NH2 analogs.

In vivo evaluation

Two compounds, compound 8 of this study and previously synthesized analog 5 were selected on the basis of their cellular RTK inhibitory activities for in vivo evaluation of inhibition of tumor growth, vascularity and metastasis. The compounds were evaluated in a B16-F10 murine metastatic melanoma model. This model is widely accepted for evaluating tumor growth and metastases, with highly vascularized tumors so that tumor-mediated angiogenesis can also be evaluated. Compound 5 showed potent VEGFR-2 inhibition, A431 cytotoxicity and moderate EGFR inhibition in the cellular assays, while 8 showed potent VEGFR-2 inhibition and A431 cytotoxicity. Compounds 5 and 8 were dosed intraperitoneally, three times weekly at 35 mg/kg. SU6668, 51 21 (Figure 6), an analog of the approved drug sunitinib and a potent inhibitor of c-Kit, VEGFR-2, PDGFR-β and fibroblast derived growth factor receptor-1 (FGFR-1) was used as a standard in this study and was dosed three times weekly at 10 mg/kg.

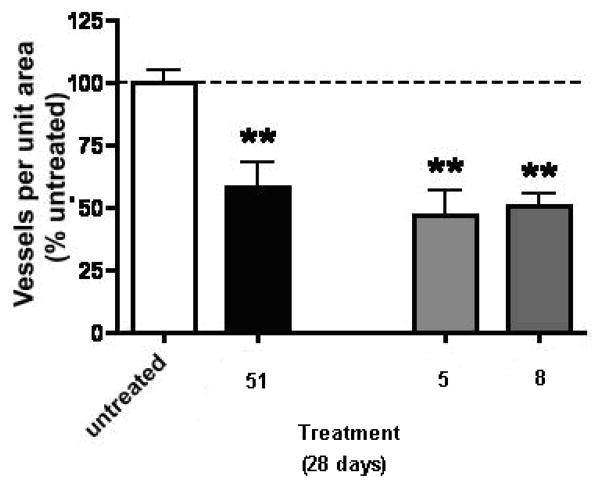

The results of the inhibitory activity of compounds 5, 8 and 51 on primary tumor growth are shown in Figure 7. Compounds 5 and 8 showed an inhibition in tumor growth compared to the untreated (sham) animals. Both 5 and 8 were effective antitumor agents compared to untreated animals, however they were somewhat less effective than 51.

Figure 7.

Inhibitory activity of compounds 5, 8 and 51(SU6668) on primary tumor growth in the B16-F10 melanoma model in mice, Values are mean ± SEM.,*** = P<0.001, **=P<0.01.

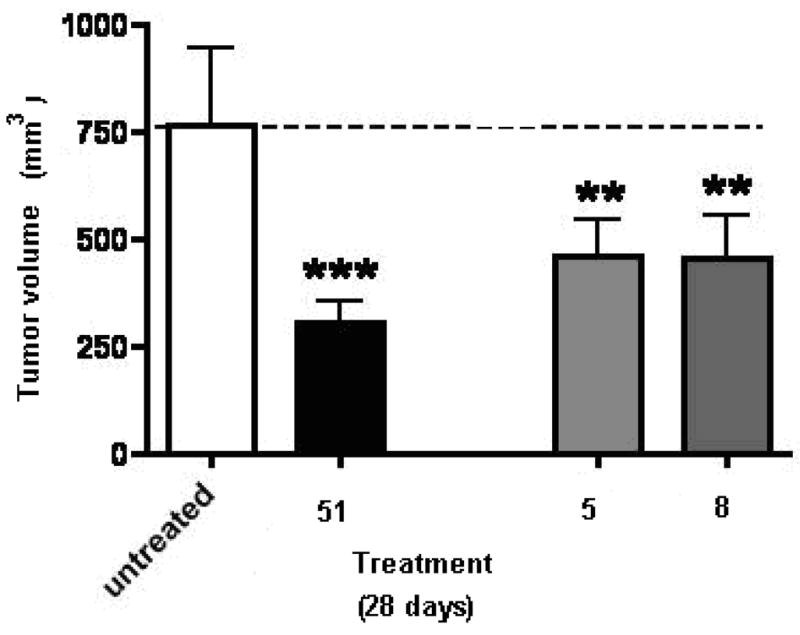

The effect of compounds 5, 8 and 51 on primary tumor vascularity is shown in Figure 8. All three agents (5, 8 and 51) induced a significant decrease in tumor vascularity compared to tumors from untreated (sham) animals. Compounds 5 and 8 were both somewhat more effective than 51 in the inhibition of tumor vascularity.

Figure 8.

The effect of compounds 5, 8 and 51(SU6668) on tumor vascularity in the B16-F10 melanoma model in mice, Values are mean ± SEM., **=P<0.01.

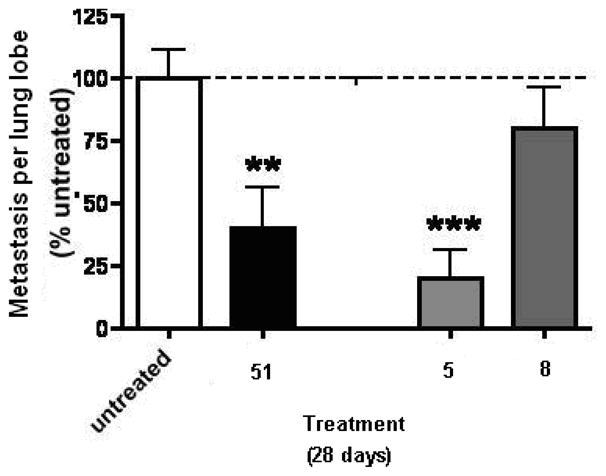

The effect of compounds 5, 8 and 51 on tumor metastasis is shown in Figure 9. The F10 variant of the B16-F10 tumor was selected for lung metastasis and one month after implantation, 90% of the animals showed lung metastases. These studies revealed that lung metastasis was inhibited with all three compounds 5, 8 and 51 compared with the untreated (sham) animals. Compound 5 was more effective than 51 in the inhibition of lung metastasis. Compound 8 also showed some inhibition of lung metastasis compared to the untreated animals but was less effective than either 5 or 51.

Figure 9.

The effect of compounds 5, 8 and 51(SU6668) on tumor metastasis in the B16-F10 melanoma model in mice, Values are mean ± SEM.,*** = P<0.001, **=P<0.01.

The in vivo antitumor evaluation of 5 and 8 suggest that both compounds cause an inhibition in tumor growth, angiogenesis and metastasis. Compound 5 shows a better inhibition of tumor angiogenesis and metastasis compared to 8. Compound 8 shows significant inhibition of angiogenesis but is less effective in inhibition of tumor metastasis.

Summary

In summary, compounds 8–15 were synthesized to improve the VEGFR-2 inhibition by variation of the phenyl substitutions of the 4-anilino moiety in compound 7. Three compounds 8, 10 and 14 showed potent cellular VEGFR-2 inhibitions and were much more potent or equipotent to the standard compound semaxanib. In fact, compounds 8, 10 and 14 were selective VEGFR-2 inhibitors and were devoid of any inhibitory activity against the other RTKs evaluated. Two compounds, 9 and 12 showed potent cytotoxic effects against A431 cells in culture, equipotent or more potent than the standard.

The cellular inhibition assays demonstrated that the potency and selectivity of the inhibition of different RTKs varies with different anilino substitutions, and that a combination of the substitutions in the 4-anilino ring and the 6-benzyl substituent dictates both specificity and potency of RTK inhibition in the 6-benzyl substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines. The different RTK inhibitory profiles observed for compounds 8–15 in this study suggest that individual substituent optimization of the anilino moiety will be necessary for each of the various scaffolds for different RTK inhibitions.

The lack of inhibitory activity of the 2-des NH2 analogs, 16–20 supports our design strategy of incorporating a 2-NH2 moiety in the 6-benzyl substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines for improved potency of RTK inhibition by providing an additional hydrogen bond with the Hinge region of RTKs. The in vivo antitumor activities of 5 and 8 indicate that both compounds cause an inhibition in tumor growth, angiogenesis and metastasis. Compound 5 was more effective in the inhibition of tumor angiogenesis and metastasis than the standard 51. Compound 8 was also more effective in the inhibition of tumor angiogenesis than the standard 51, but less effective than both 5 and 51 in the inhibition of tumor growth and metastasis. The demonstrated VEGFR-2 selectivity of 8 provides antiangiogenic activity in vivo as predicted. The in vivo antitumor activity of 5 and 8 indicates that whole cell RTK inhibitory activity does translate into successful in vivo activity and warrants the further development of 5 and 8 as antitumor agents.

Experimental

Synthesis

Analytical samples were dried in vacuo (0.2 mmHg) in a CHEMDRY drying apparatus over P2O5 at 80 °C. Melting points were determined on a MEL-TEMP II melting point apparatus with FLUKE 51 K/J electronic thermometer and are uncorrected. Nuclear magnetic resonance spectra for proton (1H NMR) were recorded on a Bruker WH-300 (300 MHz) or a Bruker 400 MHz/52 MM (400 MHz) spectrometer. The chemical shift values are expressed in ppm (parts per million) relative to tetramethylsilane as an internal standard: s, singlet; d, doublet; t, triplet; q, quartet; m, multiplet; br, broad singlet. Mass spectra were recorded on a VG-7070 double-focusing mass spectrometer or in a LKB-9000 instrument in the electron ionization (EI) or electron spray (ESI) mode. Chemical names follow IUPAC nomenclature. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on Whatman Sil G/UV254 silica gel plates with a fluorescent indicator, and the spots were visualized under 254 and 366 nm illumination. Proportions of solvents used for TLC are by volume. Column chromatography was performed on a 230–400 mesh silica gel (Fisher, Somerville, NJ) column. Elemental analyses were performed by Atlantic Microlab, Inc., Norcross, GA. Element compositions are within 0.4% of the calculated values. Fractional moles of water or organic solvents frequently found in some analytical samples could not be prevented in spite of 24–48 h of drying in vacuo and were confirmed where possible by their presence in the 1H NMR spectra. Microwave-assisted synthesis was performed utilizing an Emrys Liberator microwave synthesizer (Biotage) utilizing capped reaction vials. All microwave reactions were performed with temperature control. All solvents and chemicals were purchased from Aldrich Chemical Co. or Fisher Scientific and were used as received.

2-Amino-6-(2,4-dichlorobenzyl)-3,7-dihydro-4H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-4-one (23)

To a 250 mL round-bottom flask was added a solution of 26 (2.3 g, 10 mmol) in diethylether (50 mL). Aqueous HCl (15 mL) was added dropwise and the yellow mixture was refluxed for 1 h. The reaction mixture was cooled and the ether layer was separated, washed with water (50 mL) and dried over Na2SO4. The organic layer was evaporated to afford 2g (84%) of 28 as a yellow solid. To a 250 mL round-bottom flask was added 22 (1 eq), NaOAc (1.3 eq) and water (180 mL). The reaction mixture was refluxed for 20 min, and then a solution of 28 (2 g, 8.4 mmol) in MeOH (2 mL) was added. The reaction mixture was refluxed for another 12 h. The reaction mixture was cooled to 0 °C and filtered. The solid collected was washed with MeOH and diethyl ether to afford 1.96 g (75%) of 23; mp 265 °C (lit. mp 265 °C).27 The compound was identical in all respects to the mp, Rf, 1H NMR as that reported.27

2-Amino-6-(2-methylbenzyl)-3,7-dihydro-4H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-4-one (30)

Compound 30 was synthesized as described for 23 with 27 and was obtained as an off white solid (65%); mp 290 °C (lit. mp 290 °C).27 The compound was identical in all respects to the mp, Rf, 1H NMR as that reported.27

1-(2,6-Diamino-pyrimidin-4-yloxy)-3-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-propan-2-one (24)

To a 250 mL round-bottom flask was added 1727 (2 g, 7.1 mmol), 2,6-diaminopyrimidin-4-one and dry DMF (10 mL). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 3 days. The reaction mixture was dried in vacuo and the residue was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel (gradient, 1–5 % MeOH in CHCl3) to afford 970 mg (44%) of 23 as a yellow solid (mp, Rf, 1H NMR as that reported)27 and 23 mg (10%) of 24 as an off-white solid; TLC Rf 0.60 (CHCl3:CH3OH, 5:1); mp 152–153 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 4.01 (s, 2 H, CH2), 4.85 (s, 2 H, CH2), 5.12 (s, 1 H, CH), 5.92 (s, 2 H, NH2), 6.12 (s, 2 H, NH2), 7.35–7.60 (m, 3 H, C6H3). HRMS (EI): Calcd for C13H12N4O2Cl2 m/z = 326.0337, found m/z = 326.0337.

N-[4-Chloro-6-(2,4-dichlorobenzyl)-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-2-yl]-2,2-dimethylpropanamide (33)

To a 50 mL round-bottom flask, under nitrogen, was added compound 23 (800 mg, 2.59 mmol) and excess Piv2O (4 eq). The mixture was stirred at 100–120 °C for 2 h. The reaction mixture was cooled and hexane (40 mL) was added. The suspension was filtered to afford 850 mg (85%) of 31 as a light brown solid; TLC Rf 0.56 (CHCl3/MeOH, 10:1). To a 100-mL round-bottom flask was added 31 (300 mg, 1.3 mmol) and POCl3 (12 mL). The mixture was refluxed for 3 h. The reaction mixture was evaporated and quenched with water (15 mL). The resulting solution was cooled in an ice bath, and the pH was adjusted to 8–9 with dropwise addition of NH4OH. The mixture was diluted with CHCl3 (120 mL). The organic layer was separated and dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to afford a yellow solid. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel (isocratic, CHCl3) to afford 180 mg (58%) of 33 as a yellow fluffy solid; TLC Rf 0.81 (CHCl3/MeOH, 10:1); mp 122–124 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.21 (s, 9 H, C(CH3)3), 4.17 (s, 2 H, CH2), 6.07 (s, 1 H, CH), 7.39–7.84 (m, 3 H, C6H3), 10.01 (s, 1 H, NH), 12.40 (s, 1 H, NH). HRMS (ESI) [M + Na]+ calcd for C19H21N4Cl3 m/z = 433.0729, found m/z = 433.0744.

N-[4-Chloro-6-(2-methylbenzyl)-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-2-yl]-2,2-dimethylpropanamide (34)

Compound 34 was synthesized as described for 33 with 30 and was obtained as a yellow fluffy solid (55%); Rf = 0.76 (CHCl3/MeOH 10:1); mp 117–119 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.22 (s, 9H, C(CH3)3), 2.27 (s, 3 H, CH3), 4.05 (s, 2 H, CH2), 6.07 (s, 1 H, CH), 7.15–7.19 (m, 4 H, C6H4), 9.99 (s, 1 H, NH), 12.36 (s, 1 H, NH). HRMS (ESI) [M + H]+ calcd for C19H22N4OCl m/z = 357.1482, found m/z = 357.1470.

N4-(2-Bromo-4-chlorophenyl)-6-(2,4-dichlorobenzyl)-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine-2,4-diamine (8)

To a 100 mL round-bottom flask was added 33 (200 mg, 0.48 mmol), 2-bromo-4-chloroaniline (1.5 eq), iPrOH (20 mL) and 6 drops of conc HCl. The mixture was refluxed for 12 h. After being cooled, the reaction mixture was dried in vacuo. The residue was neutralized with NH4OH (1 mL) and extracted with CHCl3 (30 mL). The organic layer was dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to afford a yellow solid. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel (gradient, CHCl3 to 2% MeOH/CHCl3) and washed with diethyl ether to afford 180 mg (74%) of 8 as a white solid; TLC Rf 0.58 (CHCl3/CH3OH, 10:1); mp 203 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 3.99 (s, 2 H, CH2), 5.60 (s, 2 H, NH2), 5.91 (s, 1 H, CH), 7.36–7.72 (m, 6 H, C6H3 and C6H3), 8.45 (s, 1 H, NH), 10.91 (s, 1 H, NH). Anal.(C19H13Cl3BrN5 • 0.35 H2O) C, H, N, Br, Cl.

N4-(2-Fluoro-4-chlorophenyl)-6-(2,4-dichlorobenzyl)-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine-2,4-diamine (9)

Compound 9 was synthesized as described for 8 with 4-chloro-2-fluoroaniline and was obtained as a light yellow solid (86%); TLC Rf 0.57 (CHCl3/CH3OH, 10:1); mp 214 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 4.00 (s, 2 H, CH2), 5.62 (s, 2 H, NH2), 5.99 (s, 1 H, CH), 7.19–7.90 (m, 6 H, C6H3 and C6H3), 8.95 (s, 1 H, NH), 10.92 (s, 1 H, NH). Anal.(C19H13Cl3FN5 • 0.3 H2O) C, H, N, F, Cl.

N4-(3-Ethynylphenyl)-6-(2,4-dichlorobenzyl)-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine-2,4-diamine (12)

Compound 12 was synthesized as described for 8 with 3-ethynylaniline and was obtained as a yellow solid (52 mg, 53%); TLC Rf 0.55 (CHCl3/CH3OH, 10:1); mp 219 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 4.01 (s, 2 H, CH2), 4.1 (s, 1 H, CH), 5.72 (s, 2 H, NH2), 6.04 (s,1 H, CH), 6.90–8.06 (m, 7 H, C6H4 and C6H3), 8.81 (s, 1 H, NH), 10.92 (s,1 H, NH). Anal.(C21H15Cl2N5 • 0.21 H2O) C, H, N, Cl.

N4-(4-Isopropylphenyl)-6-(2,4-dichlorobenzyl)-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine-2,4-diamine (14)

Compound 14 was synthesized as described for 8 with 4-isopropylaniline and was obtained as an off-white solid (122 mg, 63%); mp 218 °C; TLC Rf 0.54 (CHCl3/CH3OH, 10:1); 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.19 (d, 6 H, CH3, J = 6 Hz), 2.8 (m, 1 H, CH, J = 6 Hz), 4.00 (s, 2 H, CH2), 5.63 (s, 2 H, NH2), 6.02 (s, 1 H, CH), 7.09 (d, 2 H, C6H4, J = 9 Hz), 7.77 (d, 2 H, C6H4, J = 9 Hz), 7.37–7.64 (m, 3 H, C6H3), 8.69 (s, 1 H, NH), 10.86 (s, 1 H, NH). Anal.(C22H21Cl2N5) C, H, N, Cl.

N4-(2-Isopropylphenyl)-6-(2,4-dichlorobenzyl)-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine-2,4-diamine (15)

Compound 15 was synthesized as described for 8 with 2-isopropylaniline and was obtained as a white solid (102 mg, 72%); TLC Rf 0.54 (CHCl3/CH3OH, 10:1); mp 216 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.09 (d, 6 H, CH3, J = 6 Hz), 3.17 (m, 1 H, CH, J = 6 Hz), 3.90 (s, 2 H, CH2), 5.40 (s, 2 H, NH2), 5.44 (s, 1 H, CH), 7.15–7.59 (m, 7 H, C6H4 and C6H3), 8.33 (s, 1 H, NH), 10.74 (s, 1 H, NH). Anal.( C22H21Cl2N5 • 0.05 CHCl3) C, H, N, Cl.

N4-(3-Bromophenyl)-6-(2-methylbenzyl)-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine-2,4-diamine (5)

Compound 5 was synthesized as described for 8 with 34 and 3-bromoaniline and was obtained as an off white solid (315 mg, 70%); mp 226 °C (lit. mp 225–228 °C). 27 The compound was identical in all respects to the mp, Rf, 1H NMR as that reported. 27 Anal.(C20H18BrN5 • 0.04 CHCl3) C, H, N, Br.

N4-(3-Fluorophenyl)-6-(2,4-dichlorobenzyl)-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine-2,4-diamine (10)

To a 2–5 mL microwave reaction vial was added 33 (300 mg, 0.73 mmol), 3-fluoroaniline (1.5 eq), i-PrOH (4 mL), DMF (1 mL) and 4 drops of conc HCl. The reaction mixture was irradiated in a microwave apparatus at 120 °C for 45 min. After being cooled, the reaction mixture was dried in vacuo. The residue was neutralized with NH4OH (1 mL) and extracted with CHCl3 (40 mL). The organic layer was dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to afford a yellow solid. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel (gradient, CHCl3 to 2% MeOH/CHCl3) and washed with diethyl ether to afford 180 mg (61%) of 6 as a light yellow solid; TLC Rf 0.56 (CHCl3/CH3OH, 10:1); mp 221 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 4.01 (s, 2 H, CH2), 5.82 (s, 2 H, NH2), 6.05 (s, 1 H, CH), 6.69–8.08 (m, 7 H, C6H4 and C6H3), 8.94 (s, 1 H, NH), 10.96 (s, 1 H, NH). Anal.(C19H14Cl2FN5 • 0.11 CHCl3) C, H, N, F, Cl.

N4-(3-Trifluoromethylphenyl)-6-(2,4-dichlorobenzyl)-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine-2,4-diamine (11)

Compound 11 was synthesized as described for 10 with 3-trifluoromethylaniline and was obtained as an off white solid (65%); TLC Rf 0.56 (CHCl3/CH3OH, 10:1); mp 216 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 4.02 (s, 2 H, CH2), 6.04 (s,1 H, CH), 5.78 (s, 2 H, NH2), 6.69 (t, 1 H, C6H4), 7.20–8.46 (m, 7 H, C6H4 and C6H3), 9.07 (s,1 H, NH), 11.00 (s, 1 H, NH). Anal.(C20H14Cl2F3N5 • 0.03 CHCl3) C, H, N, F, Cl.

N4-(3-Fluoro-4-trifluoromethylphenyl)-6-(2,4-dichlorobenzyl)-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine-2,4-diamine (13)

Compound 13 was synthesized as described for 10 with 3-fluoro-4-trifluoromethylaniline and was obtained as an off white solid (57%); TLC Rf 0.58 (CHCl3/CH3OH, 10:1); mp 220–222 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 4.00 (s, 2 H, CH2), 6.01 (s, 1 H, C5-H), 5.79 (s, 2 H, NH2), 7.26–8.19 (m, 6 H, Ar-H), 8.91(s,1 H, NH), 10.97 (s, 1 H, NH). Anal.(C20H13Cl2F4N5 • 0.44 CH3OH) C, H, N, F, Cl.

Ethyl-2-amino-5-(2-methylbenzyl)-1H-pyrrole-3-carboxylate (37)

To a 250 mL round-bottom flask, under nitrogen was added carbethoxyacetamidine hydrochloride 36,44 NEt3 (20 mL) and ethyl acetate (40 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred for at room temperature for 20 min, and then α-bromomethyl-(2-methylbenzyl)ketone (2 g, 9 mmol),27 was added and the mixture was refluxed for 1 h. After being cooled, the reaction mixture was dried in vacuo. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel (gradient, 10–50%. EtOAc/hexane) to afford 1.3 g (60%) of 37 as a red semisolid that degraded on storage and was directly used in the next step; TLC Rf 0.46 (EtOAc/hexane, 1:4); 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.17 (t, 3 H, CH3, J = 6 Hz), 2.23 (s, 3 H, CH3), 3.65 (s, 2 H, CH2), 4.01 (q, 2 H, CH2, J = 6 Hz), 5.48 (s, 2 H, NH2), 7.11–7.13 (m, 4 H, C6H4), 9.96 (s, 1 H, NH).

Ethyl-2-amino-5-(2,4-dichlorobenzyl)-1H-pyrrole-3-carboxylate (38)

Compound 38 was synthesized as described for 37 with α-bromomethyl-(2,4-dichlorobenzyl)ketone and was obtained as an orange semisolid (70%) that degraded on storage and was directly used in the next step; TLC Rf 0.5 (Hexane/ethylacetate,1:4); 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.20 (t, 3 H, CH3), 3.49(s, 1 H, C5-H), 4.02 (s, 2 H, CH2), 4.23 (q, 2 H, CH2), 5.59 (s, 2 H, NH2), 7.24–7.58 (m, 3 H, C6H4), 10.08 (s, 1 H, NH).

Ethyl-2-amino-(2,5-dimethoxybenzyl)-1H-pyrrole-3-carboxylate (39)

Compound 39 was synthesized as described for 37 with α-bromomethyl(2,5-dimethoxybenzyl)ketone and was obtained as a red semisolid (45%) that degraded on storage and was directly used in the next step; TLC Rf 0.40 (EtOAc/hexane, 1:4); 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.16 (t, 3 H, CH3), 3.67 (s, 3 H, OCH3), 3.79 (s, 3 H, OCH3), 3.95 (s, 2 H, CH2), 4.20 (q, 2 H, CH2), 5.75 (s, 2 H, NH2), 6.73–6.88 (m, 3H, C6H3), 9.98 (s, 1 H, NH).

6-(2-Methylbenzyl)-3,7-dihydro-4H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-4-one (40)

To a 250 mL round-bottom flask, under nitrogen was added 37 (1.3 g, 5.4 mmol), NaOMe (0.3 g, 50 mmol), and formamide (100 mL). The reaction mixture was heated to 160 °C for 12 h. The reaction mixture was cooled and the product was precipitated with ice. The precipitate was collected by filtration and dried in vacuo to afford 0.54 g (45%) of 40 as a pale brown solid; TLC Rf 0.55 (CHCl3/MeOH, 5:1); 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) 2.26 (s, 3 H, CH3), 3.92 (s, 2 H, CH2), 5.95 (s, 1 H, CH), 7.12–7.15 (m, 4 H, C6H4), 7.76 (s, 1 H, CH), 11.71 (s, 1 H, NH), 11.80 (s, 1 H, NH).

6-(2,5-Dimethoxybenzyl)-3,7-dihydro-4H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-4-one (41)

Compound 41 was synthesized as described for 40 with 39 and was obtained as a brown solid (40%); TLC Rf 0.51 (CHCl3/MeOH, 5:1); mp 220 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 3.67 (s, 3 H, OCH3), 3.74 (s, 3 H, OCH3), 3.86 (s, 2 H, CH2), 6.02 (s, 1 H, CH), 6.71–6.92 (m, 3 H, C6H3), 7.76 (s, 1 H, CH), 11.71 (s, 1 H, NH), 11.75 (s, 1 H, NH). HRMS (ESI) [M + Na]+: Calcd for C15H15N3O3Na m/z = 308.1011, found m/z = 308.1013.

N-4-Chloro-6-(2,5-dimethoxybenzyl)-3,7-dihydro-4H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine (44)

To a 100-mL round-bottom flask was added 41 (200 mg, 0.7 mmol) and POCl3 (12 mL). The mixture was refluxed for 3 h. The reaction mixture was evaporated and quenched with water (15 mL). The resulting solution was cooled in an ice bath, and the pH was adjusted to 8–9 with dropwise addition of NH4OH. The mixture was diluted with CHCl3 (120 mL). The organic layer was separated and dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to afford 150 mg ( 71%) of 44 as a white solid; TLC Rf 0.61 (CHCl3/MeOH, 10:1); mp 172–176 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 3.70 (s, 3 H, OCH3), 3.76 (s, 3 H, OCH3), 4.05 (s, 2 H, CH2), 6.12 (s, 1 H, CH), 6.82–6.83 (m, 3 H, C6H3), 8.52 (s, 1 H, CH), 12.53 (s, 1 H, NH).

N-4-Chloro-6-(2,4-dichlorobenzyl)-3,7-dihydro-4H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine (45)

To a 250 mL round-bottom flask, under nitrogen was added 38 (1.0 g, 5 mmol), NaOMe (0.3 g, 50 mmol), and formamide (100 mL). The reaction mixture was heated to 160 °C for 12 h. The reaction mixture was cooled and 41 was precipitated with ice. Compound 41 was collected by filtration and directly used for the synthesis of 45. To a 100-mL round-bottom flask was added 41 (200 mg, 0.7 mmol) and POCl3 (12 mL). The mixture was refluxed for 3 h. The reaction mixture was evaporated and quenched with water (15 mL). The resulting solution was cooled in an ice bath, and the pH was adjusted to 8–9 with dropwise addition of NH4OH. The mixture was diluted with CHCl3 (120 mL). The organic layer was separated and dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to afford compound 45 as a white solid (76%); TLC Rf 0.65 (CHCl3/MeOH, 10:1); 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) 4.23 (s, 2 H, CH2), 6.13 (s, 1 H, CH), 7.39–7.65 (m, 3 H, C6H3), 8.5 (s, 1 H, CH), 12.6 (s, 1 H, NH). Anal.(C13H8Cl3N3) C, H, N, Cl.

N-4-(3-Bromophenyl)-6-(2-methylbenzyl)-3,7-dihydro-4H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-4-amine (16)

To a 100-mL round-bottom flask was added 40 (200 mg, 0.7 mmol) and POCl3 (12 mL). The mixture was refluxed for 3 h. The reaction mixture was evaporated and quenched with water (15 mL). The resulting solution was cooled in an ice bath, and the pH was adjusted to 8–9 with dropwise addition of NH4OH. The mixture was diluted with CHCl3 (120 mL). The organic layer was separated and dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to afford 133 mg of 43 as a residue that was treated with 3-bromoaniline (1.5 eq), iPrOH (20 mL) and 2–3 drops of conc HCl. The mixture was refluxed for 4 h. After being cooled, the reaction mixture was dried in vacuo. The residue was neutralized with NH4OH (1 mL) and extracted with CHCl3 (30 mL). The organic layer was dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and dried in vacuo to afford 16 as a yellow solid. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel (gradient, CHCl3 to 2% MeOH/CHCl3) and washed with diethyl ether to afford 170 mg (84 %) of 16 as a white solid; TLC Rf 0.56 (CHCl3/CH3OH, 10:1); mp 242–244 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 2.26 (s, 3 H, CH3), 4.03 (s, 2 H, CH2), 6.24 (s, 1 H, CH), 7.11–7.79 (m, 8 H, C6H4 and C6H4), 8.26 (s, 1 H, CH), 9.29 (s, 1 H, NH), 11.85 (s, 1H, NH). Anal.(C20H17BrN4 • 0.17 H2O) C, H, N, Br.

N-4-(3-Bromophenyl)-6-(2,5-dimethoxybenzyl)-3,7-dihydro-4H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-4-amine (17)

To a 100-mL round-bottom flask was added 44, 3-bromoaniline (1.5 eq), iPrOH (20 mL) and 2–3 drops of conc HCl. The mixture was refluxed for 4 h. After being cooled, the reaction mixture was dried in vacuo. The residue was neutralized with NH4OH (1 mL) and extracted with CHCl3 (30 mL). The organic layer was dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and dried in vacuo to afford 17 as a white solid (55%); TLC Rf 0.54 (CHCl3/CH3OH, 10:1); mp 208–210 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 3.67 (s, 3 H, OCH3), 3.72 (s, 3 H, OCH3), 3.96 (s, 2 H, CH2), 6.29 (s, 1 H, CH), 6.80–7.81 (m, 7 H, C6H4 and C6H3), 8.26 (s, 1 H, CH), 9.28 (s,1 H, NH), 11.79 (s,1 H, NH). Anal.(C21H19BrN4O2) C, H, N, Br.

N-4-(3-Bromophenyl)-6-(2,4-dichlorobenzyl)-3,7-dihydro-4H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-4-amine (18)

Compound 18 was synthesized as described for 17 with 45 and was obtained as a white solid (77%); TLC Rf 0.61 (CHCl3/CH3OH, 10:1); mp 264–265 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 4.15 (s, 2 H, CH2), 6.27 (s, 1 H, CH), 7.15–7.67 (m, 7 H, C6H4 and C6H3), 8.29 (s, 1 H, CH), 9.29 (s, 1 H, NH), 11.92 (s, 1 H, NH). Anal.(C19H13BrCl2N4) C, H, N, Br.

N-4-(3-Ethynylphenyl)-6-(2,4-dichlorobenzyl)-3,7-dihydro-4H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-4-amine (19)

Compound 19 was synthesized as described for 17 with 45 and 3-ethynylaniline and was obtained as a a yellow solid (65%); TLC Rf 0.57 (CHCl3/CH3OH, 10:1); mp 243–245 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 4.11 (s, 2 H, CH2), 4.11 (s, 1 H, CH), 6.29 (s, 1 H, CH), 7.06–8.10 (m, 7 H, C6H4 and C6H3), 8.28 (s, 1 H, CH), 9.28 (s, 1 H, NH), 11.89 (s, 1 H, NH). Anal.(C21H14Cl2N4) C, H, N, Cl.

N-4-(3-Trifluoromethylphenyl)-6-(2,4-dichlorobenzyl)-3,7-dihydro-4H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-4-amine (20)

Compound 20 was synthesized as described for 17 with 45 and 3-trifluoromethylaniline and was obtained as a white solid (77%); TLC Rf 0.58 (CHCl3/CH3OH, 10:1); mp 244–246 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 4.18 (s, 2 H, CH2), 6.28 (s, 1 H, CH), 7.28–8.17 (m, 7 H, C6H4 and C6H3), 8.30 (s, 1 H, CH), 9.44 (s, 1 H, NH), 11.92 (s, 1 H, NH). Anal.(C20H13Cl2F3N4 • 0.3 H2O) C, H, N, F, Cl.

Biological Evaluation

All cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified environment containing 5% CO2 using media from Mediatech (Hemden, NJ, USA). The A-431 cells were from the American Type Tissue Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). All growth factors (bFGF, VEGF, EGF, PDGF-BB) were purchased from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ, USA). The PY-HRP antibody was from BD Transduction Laboratories (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Antibodies against EGFR, PDGFRβ, FGFR-1, Flk-1, and Flt-1 were purchased from Upstate Biotech (Framingham, MA, USA). The CYQUANT cell proliferation assay was from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA). The standard compounds used for comparison in the assays were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA).

Inhibition of Cellular Tyrosine Phosphorylation

Inhibition of EGF, VEGF and PDGF-BB-stimulated total cellular tyrosine phosphorylation in tumor cells naturally expressing high levels of EGFR (A431), VEGFR-2 (U251), VEGFR-1 (A498) and PDGFR-β (SF-539) respectively, were measured using the ELISA assay as previously reported.38 Briefly, cells at 60–75% confluence were placed in serum-free medium for 18 h to reduce the background of phosphorylation. Cells were always >98% viable by Trypan blue exclusion. Cells were then pre-treated for 60 min with 333, 100, 33.3, 10, 3.33, 1.00, 0.33 and 0.10 μM compound followed by 100 ng/mL EGF, VEGF, PDGF-BB, or bFGF for 10 min. The reaction was stopped and cells permeabilized by quickly removing the media from the cells and adding ice-cold Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.05% triton X-100, protease inhibitor cocktail and tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor cocktail. The TBS solution was then removed and cells fixed to the plate by 30 min at 60 °C and further incubated in 70% ethanol for an additional 30 minutes. Cells were further exposed to block (TBS with 1% BSA) for 1 h, washed, and then a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated phosphotyrosine antibody was added overnight. The antibody was removed, cells were washed again in TBS, exposed to an enhanced luminol ELISA substrate (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL, USA) and light emission measured using an UV Products (Upland, CA, USA) BioChemi digital darkroom. Standard compounds were used as controls in each of the evaluations. The standard compounds used were semaxanib, 46 for VEGFR-2; (4-chloro-2-fluorophenyl)-6,7-dimethoxy quinazolin-4-yl-amine, 48 for VEGFR-1; 4-[(3-bromophenyl)amino]-6,7-dimethoxyquinazoline, 49 for EGFR; 3-(4-dimethylamino-benzylidenyl)-2-indolinone, 50 for PDGFR-β. Erlotinib, 1 and sunitinib, 4 were also evaluated against VEGFR-2, EGFR and PDGFR-β in this assay. Data were graphed as a percent of cells receiving growth factor alone and IC50 values estimated from 2–3 separate experiments (n = 8–24) using non-linear regression Sigmoidal Dose-Response analysis with GraphPad Prism (San Diego, CA). In every case, the activity of a positive control inhibitor did not deviate more than 10% from the IC50 values listed in the text.

Antiproliferative assay

The assay was performed as described previously.47 Briefly, cells were first treated with compounds for 12h and then allowed to grow for an additional 36 h. The cells were then lysed and the CYQUANT dye, which intercalates into the DNA of cells, was added and after 5 min the fluorescence of each well measured using an UV Products BioChemi digital darkroom. Cisplatin, 47 was used as the standard for cytotoxicity in each experiment.. Data were graphed as a percent of cells receiving growth factor alone and IC50 values estimated from 2–3 separate experiments (n = 6–15) using non-linear regression Sigmoidal Dose-Response analysis with GraphPad Prism (San Diego, CA).

In vivo Antitumor Activity

In vivo antitumor activity of compounds was tested at a dose of 35mg/kg for 5 and 8, and 10 mg/kg of standard compound 51 (SU6668) three times a week by intraperitoneal route against the B16-F10 (lung colonizing) melanoma implanted in athymic NCr nu/nu male mice. 50,000 B16-F10 mouse melanoma cells were injected orthotopically SQ just behind the ear of the mice, 8 weeks in age. Two experiments were done starting with 5–6 animals/group. Animals were monitored every other day for the presence of tumors. Drug treatment was started 9 days after tumor implantation, the time at which most tumors were measurable by calipers. DMSO stocks (30 mM) of drugs were dissolved into sterile water for injection and 35 mg/kg was injected intraperitoneally (IP) every Monday (AM), Wednesday (noon) and Friday (PM). Sham treated animals received water only Monday, Wednesday and Friday. Values are mean ± SEM.,*** = P<0.001, **=P<0.01 versus untreated animals using one-way ANOVA with Neuman-Keuls post-test.

Tumor growth

The length (long side), width (short side) and depth of the tumors were measured using digital Vernier Calipers each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. Tumor volume was calculated using the formula: length × width × depth. Tumor growth rate was calculated using a linear regression analysis algorithm using the software GraphPad Prism 4.0 as the slope of the curve from day 9 after tumor implantation, the date of first treatment, out to day 28 of the experiment. The tumor volumes at the first measurement (day 9, day of first treatment) were untreated:12.3 ± 1.8 mm3, compound 5: 13.24 ± 3.0 mm3, compound 8: 14.1 ± 2.1 mm3 and 51 (SU6668): 11.9 ± 1.2 mm3.

Tumor metastases and vascularity

At the experiment’s end, day 28, the animals were humanely euthanized using carbon dioxide, tumors and lungs excised, fixed in 20% neutral buffered formalin for 8–10 hr, embedded into paraffin, and hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) stain of three separate tissue sections completed to span the tumor/lung. Metastases per lung lobe were counted using the H&E stained sections. Metastasis was seen as purple clusters of disorganized cells on the highly organized, largely pink lung. Blood vessels per unit area were counted in 5 fields at 100× magnification and averaged. Values are mean ± SEM., *** = P<0.001, **=P<0.01 versus untreated animals using one-way ANOVA with Neuman-Keuls post-test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by Grant CA98850 (A.G.) from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, and an equipment grant from the National Science Foundation (NMR: CHE 0614785).

Abbreviations

- RTK

receptor tyrosine kinase

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- PDGFR

platelet-derived growth factor receptor

- VEGFR

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor

- IGF-1

insulin-like growth factor-1

- Flt-3

fms-like tyrosine kinase 3

- c-Kit

stem cell factor receptor

- cFMS

colony stimulating factor receptor

- FGFR-1

fibroblast derived growth factor receptor-1

- ATP

adenosine triphospate

Footnotes

Elemental analysis is available online.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sun L, McMahon G. Drug Discovery Today. 2000;8:344. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(00)01534-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shauver L, Lipson K, Fong T, McMahon G, Strawn L. In: The New Angiotherapy. Fan T, Kohn E, editors. Humana Press; New Jersey: 2002. pp. 409–452. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Folkman J. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:273. doi: 10.1038/nrd2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Madhusadan S, Ganesan T. Clinical Biochemistry. 2004;37:618. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han L, Lorincz A, Sukumar S. In: Antiangiogenic Agents in Cancer Therapy. Teicher B, Ellis L, editors. Vol. 2. Humana Press; New Jersey: 2008. pp. 331–352. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rak J, Yu J, Klement G, Kerbel R. J Invest Dermatol Symp Proc. 2000;5:24. doi: 10.1046/j.1087-0024.2000.00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kerbel R, Folkmann J. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:727. doi: 10.1038/nrc905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hubbard S. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2002;12:735. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00383-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrara N. Oncologist. 2004;9:2. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.9-suppl_1-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrara N, Gerber H, LeCouter J. Nat Med. 2003;9:669. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shinkaruk S, Bayle M, Lain G, Deleris G. Curr Med Chem Anti-Cancer Agents. 2003;3:95. doi: 10.2174/1568011033353452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ciardiello F, Tortora G. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:2958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levitzki A. Acc Chem Res. 2003;36:462. doi: 10.1021/ar0201207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lynch T, Bell D, Sordella R, Gurubhagavatula S, Okimoto R. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2129. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pao W, Miller V, Politi K, Riely G, Somwar R. PLoS Med. 2005;2:225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandler A, Herbst R. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:4421s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adjei A. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:4446s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel P, Chaganti R, Motzer R. Br J of Cancer. 2006;94:614. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Jonge M, Verweij J. Eur J of Cancer. 2006;42:1351. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Druker J. Trends Mol Med. 2002;8:S14. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(02)02305-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laird A, Vajkoczy P, Shawver L, Thurnher A, Liang C, Mohammadi M, Schlessinger J, Ullrich A, Hubbard S, Blake R, Fong A, Strawn L, Sun Li, Tang Cho, Hawtin R, Tang F, Shenoy N, Hirth P, McMahon G, Cherrington J. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilhelm S, Carter C, Lynch M, Lowinger T, Dumas J, Smith R, Schwartz B, Simantov R, Kelley S. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:835. doi: 10.1038/nrd2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Atkins M, Jones C, Kirkpatrick P. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:279. doi: 10.1038/nrd2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knight ZA, Shokat KM. Chem Biol. 2005;12:621. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Force T, Krause D, Van Etten R. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:332. doi: 10.1038/nrc2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crespo A, Zhang X, Fernández A. J Med Chem. 2008;51:4890. doi: 10.1021/jm800453a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.a) Gangjee A, Yang J, Ihnat M, Kamat S. Bioorg Med Chem. 2003;11:5155. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2003.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Gangjee A. 6,770,652. US Patent No. 2004 August 3; Multiple Acting Anti-Angiogenic and Cytotoxic Compounds and Methods for Using the Same.

- 28.Bold G, Altmann K, Bruggen J, Frei J, Lang M, Manley PW, Traxler P, Wietfeld B, Buchdunger E, Cozens R, Ferrari S, Furet P, Hofmann F, Martiny-Baron G, Mestan J, Rosel J, Sills M, Stover D, Acemoglu F, Boss E, Emmenegger R, Lasser L, Masso E, Roth R, Schlachter C, Vetterli W, Wyss D, Wood J. J Med Chem. 2000;43:2310. doi: 10.1021/jm9909443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manley P, Furet P, Bold G, Bruggen J, Mestan J, Meyer T, Schnell C, Wood J, Haberey M, Huth A, Kruger M, Menrad A, Ottow E, Seidelmann D, Siemeister G, Thierauch K. J Med Chem. 2002;45:5687. doi: 10.1021/jm020899q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hennequin L, Stokes E, Thomas A, Johnstone C, Ple P, Ogilvie D, Dukes M, Wedge S, Kendrew J, Curwen J. J Med Chem. 2002;45:1300. doi: 10.1021/jm011022e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hennequin L, Thomas A, Johnstone C, Stokes E, Ple P, Lohmann J, Ogilvie D, Dukes M, Wedge S, Curwen J, Kendrew J, Lambert-van der Brempt C. J Med Chem. 1999;42:5369. doi: 10.1021/jm990345w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bridges A, Zhou H, Cody D, Rewcastle G, McMichael A, Showalter H, Fry D, Kraker A, Denny W. J Med Chem. 1996;39:267. doi: 10.1021/jm9503613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rewcastle G, Denny W, Bridges A, Zhou H, Cody D, McMichael A, Fry D. J Med Chem. 1995;38:3482. doi: 10.1021/jm00018a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tripos Inc., 1699 South Hanley Road, St. Louis, MO 63144.

- 35.Miyazaki Y, Matsunaga S, Tang J, Maeda Y, Nakano M, Philippe R, Shibahara M, Liu L, Sato H, Wang L, Nolte R. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15:2203. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harris P, Cheung M, Hunter R, Brown M, Veal J, Nolte R, Wang L, Liu W, Crosby R, Johnson J, Epperly A, Kumar R, Luttrell D, Stafford J. J Med Chem. 2005;48:1610. doi: 10.1021/jm049538w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Secrist J, Liu P. J Org Chem. 1978;43:3937. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gangjee A, Jain H, Phan J, Lin X, Song X, McGuire J, Kisliuk R. J Med Chem. 2006;49:1055. doi: 10.1021/jm058276a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gangjee A, Elzein E, Kisliuk R. J Med Chem. 1998;41:1409. doi: 10.1021/jm9705420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gangjee A, Mavandadi F, Kisliuk R, McGuire J, Queener S. J Med Chem. 1996;39:4563. doi: 10.1021/jm960097t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gangjee A, Jain H, Queener S. J Het Chem. 2005;42:589. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gangjee A, Jain H, Kisliuk R. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15:2225. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taylor E, Young W, Chaudhari R, Patel M. Heterocycles. 1993;36:1897. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Toja E, Tarzia G. J Het Chem. 1986;23:1555. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kobayashi T, Inoue T, Kita Z. Chem Pharm Bull. 1995;43:788. doi: 10.1248/cpb.43.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Venugopalan B, Desai G, de Souza N. J Het Chem. 1988;25:1633. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilson S, Barsoum M, Wilson B, Pappone P. Cell Prolif. 1999;32:131. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2184.1999.32230131.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arora A, Scholar E. J Pharmacol Experimental Ther. 2005;315:971. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.084145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kovalenko M, Gazit A, Bohmer C, Rorsman C, Ronnstrand L, Heldin C, Waltenberger J, Bohmer F. Cancer Res. 1994;54:6106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.