Abstract

The intercalated disk (ID) is a complex structure that electromechanically couples adjoining cardiac myocytes into a functional syncitium. The integrity of the disk is essential for normal cardiac function, but how the diverse elements are assembled into a fully integrated structure is not well understood. In this study, we examined the assembly of new IDs in primary cultures of adult rat cardiac myocytes. From 2 to 5 days after dissociation, the cells flatten and spread, establishing new cell-cell contacts in a manner that recapitulates the in vivo processes that occur during heart development and myocardial remodeling. As cells make contact with their neighbors, transmembrane adhesion proteins localize along the line of apposition, concentrating at the sites of membrane attachment of the terminal sarcomeres. Cx43 gap junctions and ankyrin-G, an essential cytoskeletal component of voltage gated sodium channel complexes, were secondarily recruited to membrane domains involved in cell-cell contacts. The consistent order of the assembly process suggests that there are specific scaffolding requirements for integration of the mechanical and electrochemical elements of the disk. Defining the relationships that are the foundation of disk assembly has important implications for understanding the mechanical dysfunction and cardiac arrhythmias that accompany alterations of ID architecture.

1. Introduction

Cardiac myocytes are linked to each other along their axis of contraction by complex connections called intercalated disks (reviewed in [1]). The cardiac intercalated disk (ID) is composed of three types of cell-cell contacts: adherens junctions, gap junctions, and desmosomes. These connections serve as anchorage sites for the actin cytoskeleton, the intermediate filament network, microfilaments, microtubules, and the terminal ends of the myofibrils. They stabilize the cellular cytoskeleton and electromechanically couple adjoining cardiac myocytes to form a functional syncitium. Alterations in the structure of the disk, either due to mutation of one of its components or aberrant remodeling during heart failure, can lead to progressive contractile dysfunction and cardiac arrhythmias [2].

ID remodeling may be an important ventricular adaptation to congestive heart failure. In response to dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) and congestive failure, there is a marked upregulation of adherens junction constituents, including N-cadherin, and β-catenin, and the plicate region of the intercalated disk becomes much more undulated [3]. Since the increased undulation will decrease the angle of incidence between the working myofibrils and their membrane anchorage sites, this will result in an improved force transmission and diminished shear stress at the intercalated disk. Therefore, structural adaptations within the intercalated disk, specifically within the adherens junctions, may in part compensate for the increased myocardial strain that accompanies congestive heart failure and DCM and may enable optimization of force transmission in this setting.

In contrast to the adhesive complex proteins of the intercalated disk, connexin43 (Cx43), a gap junction protein is not upregulated and, according to some reports, even downregulated in the setting of DCM [4]. Several studies have also shown significant redistribution of Cx43 in the setting of cardiomyopathies and heart failure [5]. This suggests that there are distinct regulatory pathways governing the expression of the mechanical and electrical elements of the ID, and that these pathways can be affected by disease. Additional studies have shown a close interaction between the mechanical and electrical components of the intercalated disk since loss of N-cadherin disrupts connexin localization and cardiac impulse propagation [6], and correct targeting of Cx43 to the ID depends on transport of the intact protein to cadherin-containing adherens junctions of the disk [7]. This suggests that the disruption of the mechanical components of the disk may lead to destabilization of the gap junctions and ventricular arrhythmias.

Perhaps the most direct evidence of the important relationship between the structural and electrophysiologic properties of the ID involves the clinical syndrome of Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy/Dysplasia (ARVC). ARVC is a heterogenous disorder characterized by severe ventricular arrhythmias and, commonly, fibro-fatty replacement of regions of the right and/or left ventricle (reviewed in [8]). It has been estimated that, although ARVC is a relatively rare condition, affecting approximately 1 in 5000 people in the U.S., it is responsible for approximately 10% of the cases of sudden death in individuals under the age of 35 [9–11]. To date, ten different genes have been determined to be responsible for causing ARVC, including desmocollin, desmoglein, desmoplakin, plakophillin-2 (PKP2), plakoglobin, desmin, ZASP, Transmembrane Protein 43 (TP43), and Transforming Growth Factor β3 (TGF β3). For many of these genes, mutations have only been identified in a few pedigrees worldwide [8] or lead to “atypical” forms of ARVD.

The great majority of ARVC cases with identified genetic mutations are linked to genes coding for proteins of the desmosome. Since none of these proteins directly participate in propagation of the cardiac impulse, alteration in the properties of the desmosome must have important secondary effects on the electrochemical connections within the ID including the gap junctions and/or the voltage-gated sodium channels (VGSC). Recent studies have supported this assertion, demonstrating that plakophilin-2 (PKP2), a part of the desmosomal complex, is involved in stabilization of gap junctions and VGSCs within the ID. Loss of PKP-2 was associated with redistribution of Cx43 gap junctions in cell culture models and in patients with ARVC [12–14] and with decreased sodium current and lower conduction velocity in cultured cardiac myocytes [15]. Yet the relationships between the assembly and organization of the desmosomes and the recruitment and stabilization of the gap junctions and VGSCs have not been well characterized. In this study, we examined the assembly of IDs in remodeling adult rat cardiac myocytes in primary culture. The findings suggest progressive and coordinated maturation of the transmembrane adhesion complexes, intracellular cytoskeletal networks, and, ultimately, specialized sarcolemmal domains.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

Primary cultures of cardiac myocytes were isolated from adult female rats using enzymatic dissociation of myocardial tissue with trypsin and collagenase as previously described [16]. Cells were cultivated on coverslips in 199 medium as described [17].

2.2. Immunohistochemistry

Cells on coverslips were washed with PBS, fixed in methanol for two minutes, and rinsed with PBS. Coverslips were incubated in PBS+0.1%TX100+1 mg/ml BSA for 30 minutes, rinsed three times with PBS, and incubated with primary antibody diluted in PBS+BSA for 1.5 hours at room tempretare. Following three PBS washes, coverslips were incubated with secondary antibodies. Cells were incubated with monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies together, followed by combined corresponding secondary antibodies. Controls for immunostaining were the omission of both primary antibodies and omission of both secondary antibodies. Sequential staining was performed when two monoclonal antibodies were used on one sample. After the first primary/secondary incubations, coverslips were incubated at 4°C overnight with goat antimouse IgG, then washed with PBS and incubated with Fab fragment of goat antimouse IgG. The second primary/secondary antibodies were then applied. Additional controls included reversing order of secondary antibodies and reversing order of primary incubations.

The following primary antibodies were used: 4B2 against Dsg [18], PKP2 (1 : 20, Biodesign International, Meridian Life Science, Saco, ME. K44262M), pan-cadherin (1.4 mg/ml, Sigma C3678), NW6 against desmoplakin (1 : 100), ankyrinG (10 μg/mL, SCBT, SC28561), connexin43 (750 μg/mL, Sigma C8093), plakoglobin (1 : 100, Sigma P8087), Nav1.5 (40 μg/mL, Alamone ASC-005). FITC conjugated goat-antimouse IgG, Texas Red conjugated goat-antimouse IgG, FITC conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG, and Texas Red-conjugated goat antirabbit IgG were obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc. (West Grove, PA). Coverslips were mounted on slides using the Prolong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (Molecular Probes Inc., Eugene, OR). Immunostained samples were examined with an Olympus FV-500 Meta confocal microscope using a 60x objective.

2.3. Electron Microscopy

Cells were plated on laminin-coated coverslips as above. Five days post plating, the cells were fixed overnight at 4°C in 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 2.0% paraformaldehyde and post fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide. After washing, they were stained with saturated uranyl acetate, and embedded in Epon 812. Ultra-thin sections were prepared and stained with saturated uranyl acetate and lead citrate. The sections were examined with a Philips CM100 transmission electron microscope, at an accelerating voltage of 60 kV.

3. Results

3.1. Time Course of ID Remodeling in Primary Culture

Adult rat cardiac myocytes grown in primary culture in the presence of serum disassemble their contractile structures and remodel their cellular cytoskeleton [19]. Over the course of 2–5 days, the cells extend processes, form new cell-matrix and cell-cell contacts, assemble new myofibrils, and resume spontaneous beating. During the remodeling process, the components of the ID are dismantled and subsequently reassembled at the new sites of cell-cell contact. To assess the time course of intercalated disk reassembly, primary cultures were immunolabeled with a pan-cadherin and PKP2 antibodies at timepoints from 1 to 14 days post plating (Figures 1 and 2). It was noted that, as a result of cell spreading and redistribution of adhesive junction components, new cell-cell contacts began to form as early as 3 days post plating along the boundaries between adjoining cells (Figure 2). Over the next 1-2 weeks in culture, the degree of myofibril alignment increased and the new IDs became focused at the polar ends of the myocyte along the new axis of contraction (see Figures 1(e) and 1(e′)).

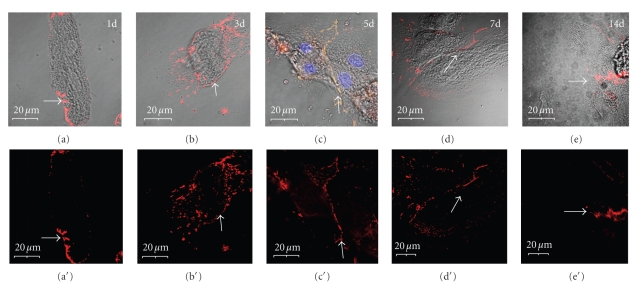

Figure 1.

Reassembly of cell-cell contacts in remodeling adult rat cardiac myocytes in culture. (a, b) On days 1–3 post plating, the cell rounds up, the IDs disassemble, and cadherins redistribute along the periphery of the cell (arrow in b). (c, d) Between days 5–7, new cell-cell contacts form and cadherin localizes to specific domains along the line of apposition (arrows). (e) By 14 days post plating, the cell-cell contacts have remodeled to form more localized and mature structures (arrow). Scale bars are 20 μm.

Figure 2.

Early remodeling of the intercalated disks of isolated adult rat ventricular cardiomyocytes in primary culture. (a) One day post plating, PKP2 (green) and N-cadherin (red) relocalize from the intercalated disks to the lateral sarcolemma. (b)–(e) By day 3 post plating, very immature cell-cell contacts have begun to form between the spreading cardiomyocytes. N-cadherin (red) specifically localizes to these contact sites before PKP2 (green). Note that these new cell contacts predominantly contain either N-cadherin (arrowheads in (b)–(f)) or both N-cadherin and PKP2 ((b)–(f): yellow) but not PKP2 alone. Scale bars are 20 μm (b) and 10 μm (c)–(f).

Based on these studies, the 5 day post-plating timepoint was selected for further analyses. This timepoint allowed the evaluation of the order of incorporation of cytoskeletal elements into more complex and organized assemblies (Figure 3). At later timepoints, contractile activity and ongoing remodeling made it more difficult to differentiate assembling from disassembling structures.

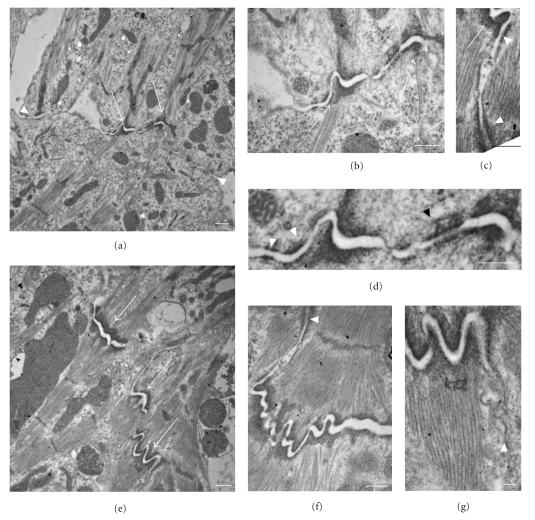

Figure 3.

Ultrastructural analysis of new cardiomyocyte cell-cell contacts at 5-days post plating. At this timepoint, cell contacts form and develop rapidly, allowing the observation of both nascent (a, b, d) and more mature (c, e, f, g) contact sites. (a) Remodeling cardiomyocytes extend fingerlike projections (arrowheads) that interact with neighboring cells to form adhesive contacts (arrows) thereby electromechanically linking the two cells. (b, d) Higher magnifications of an adhesive domain indicated in (a) shows insertion of actin filaments into nascent adherens junctions (AJs) (arrows in (b)). Note the nascent (white arrowheads in (d)) and more mature (black arrowhead in (d)) desmosomal contacts in close proximity to the maturing AJ. (c) A mature adhesive domain again demonstrates desmosomal contacts (arrowheads) near a newly formed adherens junction (arrow). (e)–(g) More mature adhesive contacts demonstrate adherens junctions (arrows in (e)) at the insertion of the terminal actin filaments of newly formed myofibrils, along with closely associated desmosomal contacts (arrowhead in (f)) and gap junctions (arrowhead in (g)). Scale bars are 500 nm (a)–(f) and 100 nm (g).

3.2. Adhesive Junction and Armadillo Family Proteins Colocalize during the Early Phase of ID Assembly

To determine the scaffolding requirements for each element of the ID, their inclusion into new cell-cell contacts of varying complexity and maturity was examined at 5-days post plating. The order of incorporation was determined by pairwise comparison of double immunolabelings with an array of ID components. If two elements precisely colocalized in all cells sampled then they were scored as essentially concurrent in their incorporation into the new cell-cell contact. For some pairs, one of the two elements was never noted at cell contacts in the absence of the other; that element was determined to be recruited after the other to the new cell contacts. For some pairs, the localization patterns did not precisely overlap and either protein could localize to the new contact without the other. In those cases, the localization was determined to be simultaneous but not strictly interdependent.

Using this approach, the earliest components of the ID to localize to new cell-cell contacts were the transmembrane proteins, including N-cadherin and desmocollin, and the armadillo family proteins, including β-catenin (data not shown), plakoglobin (PG), and PKP2 (Figure 4). Of these, N-cadherin seemed to be required for adhesive contact formation as none of the other components were noted along the line of cell apposition in its absence. There was some variability in the ratio of PKP2 to desmocollin (Figures 4(d)–4(f)), indicating that there may be a nonstoichiometric relationship between the two, at least early in the assembly process or that PKP2 can localize to contacts that do not contain desmocollin. However, the localization patterns were nearly identical, indicating simultaneous or virtually simultaneous incorporation of the cadherin-armadillo protein complexes of both desmosomal and adherens junctions subtypes into the new cell adhesive domains. The most notable differences were in regions where N-cadherin was noted along projections within the cell extending from the site of cell-cell contact. These may represent filopodial-like cellular projections that, once the contact with the adjoining cell is established, recruit desmosomal components including PKP2 (Figures 4(a)–4(c)).

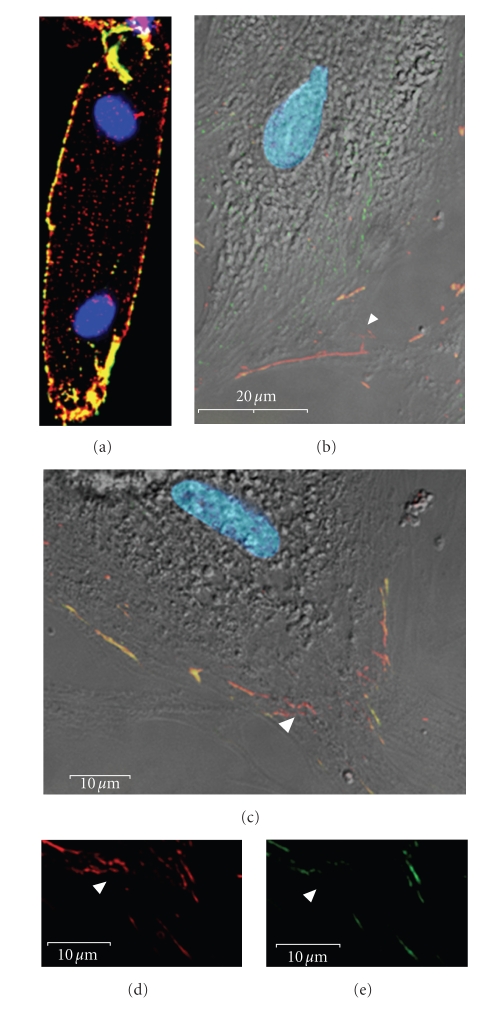

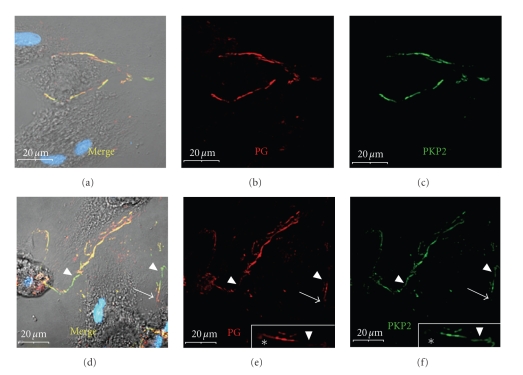

Figure 4.

Co-localization of PKP2 with N-cadherin and desmocollin in newly formed cell-cell contacts. ARCs were immunolabeled with antibodies to PKP2 (green: a, b, d, e) and pan-cadherin (red: a, c) or desmocollin (red: d, f) on day 5 post plating. There is an extensive overlap in localization of PKP2 with both N-cadherin and desmocollin. Note that there was a localization of N-cadherin along the lateral aspects of cellular projections at the cell-contact sites (arrows in (a)–(c)). These may represent filopodial extensions that mature into cell-adhesion domains. There was also noted to be some regional variation in the relative amounts of PKP2 and desmocollin (arrows in (d)–(f)). Scale bars are 10 μm.

Localization of the desmosomal cadherins, PKP2 and PG to overlapping sarcolemmal domains closely followed N-cadherin incorporation. Variations in the relative abundance of the two within the adhesive contacts (Figure 5) suggests that, while PKP-2 and PG are localizing to the same sarcolemmal regions concurrently, the presence of one may not be required for the localization of the other and both may be dependent on the presence of other components, namely, the cadherins, for proper incorporation into the adhesion complex.

Figure 5.

Localization of plakoglobin and plakophilin-2 in remodeling adult rat cardiac myocytes. ARCs were immunolabeled with antibodies to plakoglobin (PG) (red: a, b, d, e) and PKP2 (green: a, c, d, f) on day 5 post plating. Note the extensive co-localization of the two armadillo family proteins to new cell adhesion domains between contacting cells (a)–(c). There was some regional variation in the relative abundance of the two such that some newly-formed contacts contained predominately plakoglobin ((e): arrow; (e)-inset: asterisks) or PKP2 ((f) and (f)-inset: arrowheads). Scale bars are 20 μm and the insets in (e) and (f) are a 2 × magnification of a region of cell-cell contact.

Insertion of the intermediate filaments into the desmosomal complex requires desmoplakin (DP), a plaque protein that binds to intermediate filaments and to desmosomal proteins such as PKP2, PG, desmocollin, and desmoglein. DP appeared to be recruited to the newly-formed cell contacts after the assembly of complexes of the cadherin and armadillo family of proteins. In addition, it appeared to be recruited to only a subset of the contact sites. In contrast to PKP2 which distributed along the entire adhesive contact, DP localization was more granular in appearance, indicating the assembly of desmosomal plaques (Figure 6).

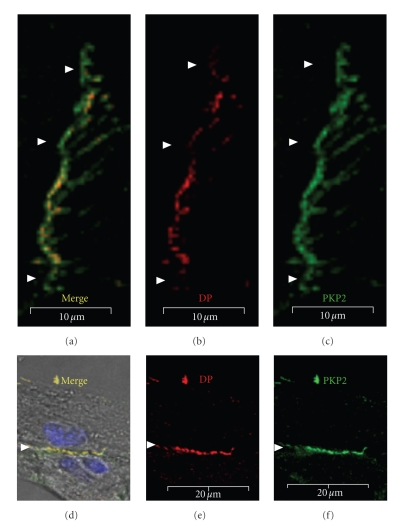

Figure 6.

Localization of DP to a subset of adhesive sites. ARCs were immunolabeled with antibodies to desmoplakin (red: a, b) and PKP-2 (green: a, c) on days 5 (a)–(c) and 7 (d)–(f) post plating. The absence of DP from some of the adhesive domains ((a)–(c): arrowheads) suggests that its localization to the newly forming structures occurs after PKP2. DP and PKP2 do fully co-localize at more mature adhesive contacts ((d)–(f): arrowheads). Scale bars are 10 μm (a)–(c) and 20 μm (e, f).

3.3. Connexin43 Concentrates at New IDs after the Assembly of the Adhesive Junction-Armadillo Protein Complexes

Previous studies have demonstrated that gap junction formation is dependent on the prior assembly of adhesive contacts in multiple cell types including cardiac myocytes [20–22]. Disruption of either desmosomal or adherens junction complexes results in the loss of gap junctions from the intercalated disk and the development of malignant ventricular arrhythmias [23, 24]. Prior work by Kostin et al. [25] demonstrated that, in primary adult rat cardiac myocytes in primary culture, both adherens junctions (as determined by immunolocalization of N-cadherin and α- and β-catenin) and desmosomal contacts (as determined by desmoplakin and PG) were recruited to new cell-cell contacts prior to the formation of gap junctions. We similarly noted the recruitment of gap junctions selectively to membrane domains involved in adhesive contacts (Figure 7). Subsarcolemmal assembly of connexons preceded their insertion into adhesive domains (Figures 7(a), 7(b), and 7(d)).

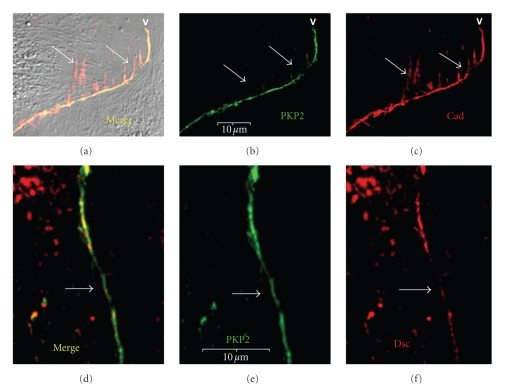

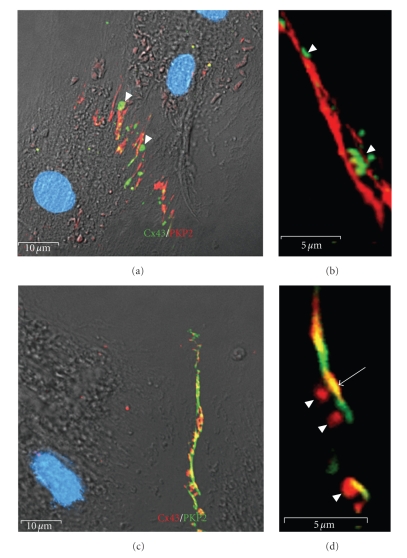

Figure 7.

Connexin43 localization to cell-cell contact domains follows adhesion complex assembly. ARCs at 5 days post plating were immunolabeled for Cx43 (green: (a, b); red: (c, d)) and PKP2 (red: (a, b); green: (c, d)). Early in the assembly and organization of cell-cell contacts in ARCs in primary culture, adhesive sites do not contain appreciable amounts of Cx43 (green: (a, b); red: (c, d)). (a) Connexin43 localization to newly formed adhesive contacts as identified by PKP2 immunostaining. Note the subsarcolemmal accumulation of connexons at the apices of the interdigitized contacts (arrowheads). (b) High magnification image of newly formed contact with subsarcolemmal accumulation of connexons prior to insertion into the membrane. (c, d) Low and higher magnification images of subsarcolemmal accumulation of connexons (arrowheads) prior to their insertion into the membrane. Note the regions of overlap of PKP2 and Cx43 immunolabeling indicating areas of mature gap junctions within the adhesive domains (arrow). Also, note that the Cx43 inserts into the membrane preferentially at adhesive sites (a, d). Scale bars are 10 μm (a, c) and 5 μm (b, d).

3.4. Recruitment VGSCs to the Intercalated Disk

Previous studies examining the localization of VGSC signaling complexes to specific subcellular membrane domains have highlighted the role of ankyrins in the targeting and stabilization process. It has been demonstrated that Nav1.5 physically interacts with ankyrin-G [26]. A mutation in SCN5A, the gene encoding Nav1.5, that impairs its ability to bind ankyrin-G results in loss of the channel from the sarcolemma and causes Brugada Syndrome, an electrophysiologic defect of the heart associated with ventricular fibrillation and sudden death [27]. Recent studies have further demonstrated an interaction between PKP2 and Nav1.5, suggesting functional integration of the VGSC with other membrane proteins such as ankyrin and with desmosomal adhesive complexes [15].

Therefore, to determine the structural requirements for the recruitment of the VGSC to newly formed IDs, the pattern of localization of ankyrin-G, Nav1.5, and the desmosomal protein PKP2 was examined at 5 and 13 days post plating. By 5 days post plating, ankyrin-G was specifically recruited to sarcolemmal domains involved in cell-cell contacts as determined by PKP2 colocalization (Figure 8). It appeared to arrive at the new ID significantly prior to the Nav1.5 α subunit, consistent with ankyrin-G recruiting VGSCs to the sarcolemma. Furthermore, it suggests that ankyrin-G is likewise dependent for its localization on targeting mechanisms that specifically direct it to sites of cell-cell contact.

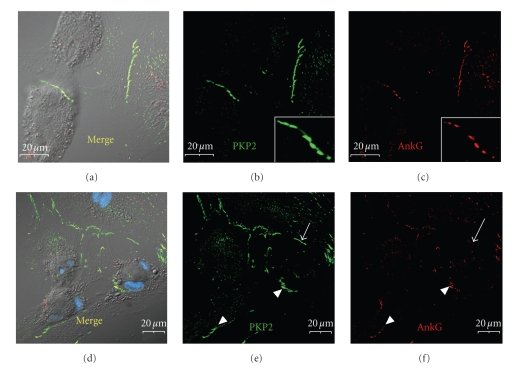

Figure 8.

Ankyrin-G is selectively recruited to membrane domains involved in adhesive contacts. At 5 days post plating, ARCs were immunolabeled for PKP2 (green: a, b, d, e) and ankyrin-G (red: a, c, d, f). (a)–(c) Ankyrin-G localizes to mature cell adhesion domains where it co-localizes with PKP2 (see insets). (d)–(f) Ankyrin-G is far less abundant (arrowheads) or not yet detectable (arrow) in immature or newly-formed adhesive contacts. Scale bars are 20 μm with the insets being 2 × magnifications of the larger image.

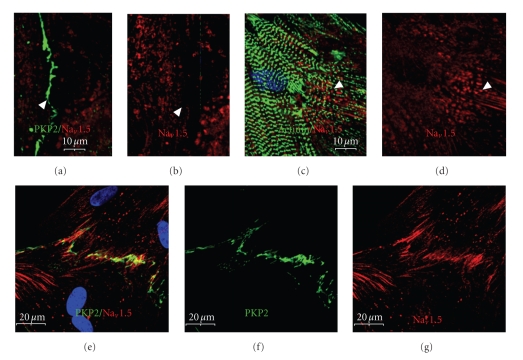

The Nav1.5 α subunit itself arrives at the newly formed ID much later than ankyrin-G. At the 5-day timepoint, when new cell-cell contacts are forming and ankyrin-G is beginning to co-localize to cell contact sites, immunostaining for Nav1.5 demonstrates a more diffuse localization (Figures 9(a)–9(d)). The antibody detects epitopes closely associated with newly assembled myofibrils. Previous work has demonstrated that membrane domains are closely associated with these new myofibrils [28]. Whether or not this truly represents localization of Nav1.5 to membrane structures associated with the myofibril remains to be determined. That ankyrin-G co-localized with Nav1.5 to these sites suggests that the immunostaining is specific and may represent a developmental intermediate as the membrane domains reorganize in the redifferentiation phase of remodeling. Later relocalization of Nav1.5 to the ID was demonstrated by immunostaining at 13 days post plating (Figures 9(e)–9(g)).

Figure 9.

The α subunit of the voltage-gated sodium channel is incorporated significantly later into the newly-formed intercalated disks. ARCs at 5 (a)–(d) and 13 (e)–(g) days post plating were immunolabeled for Nav1.5 (red: (a)–(e) and (g)) and PKP2 (green: a, e, f) or α-actinin (green: (c)). (a, b) At the 5-day timepoint, there is no detectable localization of Nav1.5 even to mature cell adhesion sites (arrowhead). (c, d) Instead, Nav1.5 appears to be more closely associated with assembling myofibrils (arrowhead). Note the linear arrays of Nav1.5 immunolabeling between α-actinin-labeled myofibrils. (e)–(g) By 13 days post plating, the channel has localized to the new intercalated disk, significantly after the other components. Scale bars are 10 μm (a)–(d) and 20 μm (e)–(g).

4. Discussion

The de- and redifferentiation of adult rat ventricular myocytes in primary culture has long been used to examine the processes guiding the reorganization of cytoskeletal and contractile structures that occurs during cardiac development and during the cellular remodeling that accompanies adaptation to pathophysiologic conditions [19]. Perhaps no model system is more ideally suited for characterizing the stepwise assembly and functional integration of complex cardiomyocyte structures such as the intercalated disk and the cardiac myofibril.

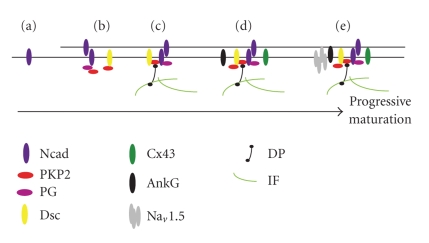

Pioneering studies by the laboratories of Werner Franke [29, 30] and Jutta Schaper [25, 31] have used primary cultures of neonatal and adult rat cardiac myocytes to make important contributions to our understanding of ID assembly and organization. The findings presented here build on this previous work by focusing on the ordered assembly of the desmosome and on the relationship between the desmosomal complex and the electrochemical connections within the disk (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Progressive maturation of the intercalated disk (a)–(e). (a) As cardiomyocytes remodel, N-cadherin (Ncad) distributes diffusely around the cell periphery. (b) When cells contact adjoining cells, desmocollin (Dsc) proteins of the armadillo family including plakoglobin (PG) and plakophillin-2 (PKP2) co-localize with N-cadherin at the cell contact site. (c) The nascent adhesive contacts recruit desmoplakin (DP) and the associated intermediate filaments. (d) After assembly of the adhesive plaque, connexin-43 (Cx43) and ankyrin-G (AnkG), a component of the VGSC, selectively localize to the adhesive contact site. (e) The α subunit of the voltage-gated sodium channel Na is incorporated significantly later into the more mature intercalated disks where they associate with ankyrin-G. The assembly process begins with the clustering of transmembrane adhesive contacts, followed by the recruitment of the plaque proteins and reorganization of the subcortical cytoskeleton. The process culminates with the recruitment of gap junctions and components of the VGSC complex (AnkG and Nav1.5) which are also assembled in a step-wise fashion.

4.1. Relationship of Desmosomes and Adherens Junctions

Traditionally, the intercalated disk was viewed as the sum of distinct intercellular contacts that could be readily categorized as desmosomes, adherens junctions, or gap junctions. More recent studies however have suggested that interrelationships of the desmosomes and the adherens junction components may be more extensive than previously recognized. There is now strong evidence that, in the mammalian heart, components of the desmosome and adherens junction routinely interact to form composite structures [32], leading to the coining of the term “area composita” to refer to domains within the plicate region of the ID disk in which there is an extensive intermingling of the two types of contacts. These cross-type connections would be predicted to form a strong network linking the actin filaments at the terminal ends of the myofibrils, with the cortical actin and intermediate filaments of the cellular cytoskeleton. The transmembrane portions of the connections would extend this network to the adjoining cells to form a “tissue-skeleton” for the heart, preserving ventricular architecture in the face of the hemodynamic demands.

Despite the important relationship between the two cell adhesion systems, how these interconnections are established and maintained is still not well understood. Previous studies have demonstrated the dependence of desmosome formation on the prior assembly of adherens junctions, suggesting a hierarchy within the assembly process. Human keratinocytes treated with antibodies to E- and P-cadherin are unable to form adherens junctions and have a dramatically reduced number of desmosomes [33]. Overexpression of a dominant negative cadherin in keratinocytes likewise impaired desmosome formation [34]. The mediator of this interaction between the two transmembrane systems may be plakoglobin, which is capable of interacting with both desmosomal and classic cadherins.

Our studies would suggest that a similar hierarchy exists in cardiac myocytes. Yet the extensive overlap in the localization patterns for the cadherin and armadillo protein components of both the desmosomes and the adherens junctions suggests that these processes occur nearly simultaneously in the remodeling cardiac myocyte and supports the previous observation that there is intermingling of the two types of adhesive contacts early in ID assembly [25]. The extent to which these contacts are subsequently sorted into distinct contact types (desmosome versus adherens junction) has been debated, but studies by the Franke laboratory suggest that in mammals, as opposed to fish and amphibians [35], these contacts will ultimately be intermingled within the area composita of the ID after birth [32].

4.2. Desmosomal Assembly in Newly Formed Cardiomyocyte Cell-Cell Contacts

The assembly of the elements of the intercalated disk would suggest that it progresses in a layered fashion, beginning with the organization of the transmembrane components and ultimately resulting in the remodeling of the cellular cytoskeleton. The “outside the cell” to “inside the cell” progressive organization of the intercalated disk is reminiscent of focal adhesion formation in that contact of the cell with extracellular environment (either the surrounding matrix in the case of the focal adhesion or the neighboring cells for the IDs) initiates organization of transmembrane molecules, followed by assembly of the submembrane complexes and integration with the cellular cytoskeleton. As with focal adhesions, dynamic cellular processes then promote “inside-out” remodeling of the transmembrane complexes leading to the clustering at specific contact sites, in this case, those that are localized to the termini of the cardiac myofibrils. Although there are two types of cell-cell contacts that form between neighboring cardiac myocytes, desmosomes and adherens junctions, the current study is in agreement with prior observations [25] that there may be a mixture of these two types of adhesive contacts. That PKP2, a desmosomal component, was noted to localize to contact sites lacking desmocollin, but never to domains lacking N-cadherin supports this assertion. Although direct interactions have not been described between PKP2 and classic cadherins, PG interacts with both classic cadherins and PKP2 and may promote localization of PKP2 to the contact site even in the absence of desmosomal cadherins. The ability of PG to bind to both classic and desmosomal cadherins and to interact with PKP2 may allow it to promote interactions of the two types of contacts both early in the formation of new intercalated disks as noted by Kostin et al. [25], and within the area composita later in the maturation of the disk [32].

The recruitment of PKP2 to the new intercalated disk may be required for the next phase of desmosomal assembly, namely, the linkage of the transmembrane complex with the intermediate filaments of the cellular cytoskeleton through the desmosomal plaque protein, desmoplakin. At the amino terminus of desmoplakin is a plakin domain that interacts with desmocollin, desmoglein, PKP2, and PG [36–38]. The carboxy terminus has an intermediate filament binding domain that promotes interactions with desmin intermediate filaments, vimentin, and cytokeratins [39]. Therefore, desmoplakin is required for the docking and integration of the intermediate filament system with the desmosomal cadherins, either through direct physical interaction or as part of a complex through interaction with the armadillo proteins, PG and PKP2. Once established, this connection physically links the cellular cytoskeleton of one myocyte with the next through the transmembrane and intercellular connections of the desmosome. This linkage is critical for the integrity of the desmosome and for the stability of the cellular cytoskeleton. Prior studies have demonstrated that PKP2 scaffolds PKCα, which prepares desmoplakin for incorporation into the desmosome [22]. Therefore, it is not surprising that DP only localized to regions of cell contact that already had recruited PKP2.Whether or not DP would have been able to localize to the ID in the absence of PKP2 or other elements of the adhesion complex was not examined in this study.

4.3. Relationship of Adhesive Contacts to Electrochemical Connections within the ID

As noted above, our findings regarding the assembly of gap junctions following the formation of adhesive contacts are consistent with the prior studies using this model system [25, 30–32]. This is true both for newly assembled contacts and for more mature intercalated disk-like structures. Connexin43 was recruited to new cell contacts after formation of adhesive contacts. As those contacts remodeled and more mature intercalated disk-like structures were organized, connexin43 remained more diffusely localized around the cell periphery before relocalizing to the new ID.

The factors that recruit gap junctions to and stabilize them within the ID are of particular interest for understanding the genesis of ventricular arrhythmias. Redistribution of gap junctions from the intercalated disk to the lateral sarcolemma is a characteristic feature of a range of myocardial disorders including myocardial ischemia, myocardial hypertrophy, and hypertrophic and dilated (or congestive) cardiomyopathy [4, 5]. This process, termed lateralization of the gap junctions, appears to be dependent upon or at least associated with changes in the phosphorylation state of specific residues within the carboxy terminus of connexin43 [40]. While heart failure and ischemic cardiomyopathy is only associated with an overall reduction in gap junction content of approximately 50% [41], compared to the 80% reduction required to see abnormalities of conduction velocity in animal models [42], regional variation in gap junction content can result in some regions within the diseased ventricle with greater than 90% reduction [41]. Direct electrical measurements are still required to properly assess the impact of this redistribution in the context of action potential propagation. Yet, we speculate that the genesis of ventricular arrhythmias in this setting may be due to the overall reduction and redistribution of gap junctions from the ID and, even more importantly, to the heterogeneity of electrical coupling within afflicted regions, thus setting the stage for generation of reentrant arrhythmias. Therefore, defining the interactions that affect gap junction localization to and retention within the ID region will be important for identifying strategies to limit its redistribution and the resulting effects this has on impulse propagation and cell connectivity within the myocardium.

Like the gap junctions, the VGSC ion conducting pore also appears to be recruited to the ID significantly after the formation of the adhesive complexes and is specifically localized to adhesion domains within the region of cell-cell contact. As noted previously [15], this suggests an interrelationship between the VGSC and the desmosome. How ID remodeling during pathophysiologic stress affects VGSCs has not been well studied. Given the array of cardiac dysrhythmias and conduction abnormalities that can occur with SCN5A mutations [43–45], it would be anticipated that a change in channel distribution or function within the ID might have a dramatic effect on the propensity for cardiac arrhythmias. As with the gap junctions, structural remodeling of the ID may result in redistribution of Nav1.5 and reduction in conduction velocity. Regional variation in conduction velocity can, in turn, lead to abnormal impulse propagation that supports ventricular arrhythmias.

While previous studies have examined the relationship of desmosomal and gap junction assembly in redifferentiating cardiac myocytes as noted above, the localization of Nav1.5 to the ID has not been well described. Nav1.5 is responsible for impulse generation and propagation in the heart. The complex includes a pore-forming α subunit, and two different structural and regulatory β subunits. An essential component of the VGSC complex is ankyrin-G, a membrane protein that binds both Nav1.5 and β1 and localizes VGSCs to specific subcellular domains [46–48]. There are nine different VGSC α subunit genes [49], four of which are expressed in the ventricular myocyte, including the tetrodotoxin sensitive (TTX-S) channels, Nav1.1, Nav1.3, and Nav1.6 and the tetrodotoxin-resistant (TTX-R) channel Nav1.5 [50]. In heart, the TTX-S channels localize with ankyrin-B to the transverse T-tubule system while TTX-R Nav1.5 interacts with ankyrin-G and is targeted to the intercalated disk and to the lateral sarcolemma [26]. The importance of Nav1.5 to normal cardiac physiology is evident from the range of severe cardiovascular disorders associated with alterations in the function or integrity of the Nav1.5 signaling complex as well as the severe phenotype of the Scn5a null mouse model [51]. Mutations in SCN5A have been described in patients with Long QT syndrome (LQT3) [43], Brugada Syndrome (BS) [44], Progressive Familial Heart Block (PFHB1A), and Dilated Cardiomyopathy with conduction disorder and arrhythmia (CMD1E) [52]. These disorders are associated with abnormal impulse propagation (PFHB1A and CMDE1) and/or severe ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death (LQT3, BS, and CMDE1). The finding of dilated cardiomyopathy in a subset of patients may be due to the adhesive properties of β1 and/or β2 subunits [53, 54] and is further evidence of the close relationship of the structural and electrochemical properties of the ID.

In this study, we noted that ankyrin-G was selectively recruited to cell-cell contact domains involved in adhesive interactions, suggesting that cell adhesion is required for localization of Nav1.5 to the ID. This targeting concentrates the channel at specific sarcolemmal domains, most specifically those domains that are also involved in direct electrochemical communication between adjacent cells through co-localization with gap junctions.

5. Summary

The current study builds on prior work using the de- and redifferentiation model of cardiac myocyte remodeling to examine the ordered assembly and integration of the elements of the ID. The current study demonstrates that desmoplakin and ankyrin-G are specifically recruited to PKP-containing adhesion plaques in remodeling cardiac myocytes and that localization of ankyrin-G to new intercalated disks significantly precedes the recruitment of Nav1.5, the alpha subunit of the VGSC. These new findings have important implications for the scaffolding of critical elements of the cellular cytoskeleton involved in the pathogenesis of disease processes including ARVD and Nav1.5-dependent disorders (e.g., Long QT Syndrome type 3 and Brugada Syndrome). The observed hierarchy for the assembly of the mechanical and electrochemical components of the disk has important implications for determining the genesis of ventricular arrhythmias in these disorders. Through the identification of mechanisms of arrhythmia generation, it may be possible to develop novel treatment strategies to prevent serious ventricular arrhythmias and lower the risk for sudden cardiac death in patients with ischemic or genetic myocardial disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to recognize Sarah Schumacher, Guadalupe Guerrero-Serna, Priscilla Sato, and Oksana Nekrasova for their technical advice and assistance. The work was supported by funds from the NIH [R01-HL075093 (MWR)], from the Stern Professorship (MWR) at the University of Michigan, from the Joseph L. Mayberry Endowment (KJG), and a grant from the LeDucq Foundation (MD, KJG).

References

- 1.Forbes MS, Sperelakis N. Intercalated discs of mammalian heart: a review of structure and function. Tissue and Cell. 1985;17(5):605–648. doi: 10.1016/0040-8166(85)90001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perriard J-C, Hirschy A, Ehler E. Dilated cardiomyopathy: a disease of the intercalated disc? Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2003;13(1):30–38. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(02)00209-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ehler E, Horowits R, Zuppinger C, et al. Alterations at the intercalated disk associated with the absence of muscle LIM protein. Journal of Cell Biology. 2001;153(4):763–772. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.4.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaprielian RR, Gunning M, Dupont E, et al. Downregulation of immunodetectable connexin43 and decreased gap junction size in the pathogenesis of chronic hibernation in the human left ventricle. Circulation. 1998;97(7):651–660. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.7.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith JH, Green CR, Peters NS, Rothery S, Severs NJ. Altered patterns of gap junction distribution in ischemic heart disease. An immunohistochemical study of human myocardium using laser scanning confocal microscopy. American Journal of Pathology. 1991;139:801–821. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li J, Levin MD, Xiong Y, Petrenko N, Patel VV, Radice GL. N-cadherin haploinsufficiency affects cardiac gap junctions and arrhythmic susceptibility. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2008;44(3):597–606. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaw RM, Fay AJ, Puthenveedu MA, von Zastrow M, Jan Y-N, Jan LY. Microtubule plus-end-tracking proteins target gap junctions directly from the cell interior to adherens junctions. Cell. 2007;128(3):547–560. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muthappan P, Calkins H. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases. 2008;51(1):31–43. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hulot J-S, Jouven X, Empana J-P, Frank R, Fontaine G. Natural history and risk stratification of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2004;110(14):1879–1884. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000143375.93288.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tabib A, Loire R, Chalabreysse L, et al. Circumstances of death and gross and microscopic observations in a series of 200 cases of sudden death associated with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy and/or dysplasia. Circulation. 2003;108(24):3000–3005. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000108396.65446.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dalal D, Nasir K, Bomma C, et al. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia: a United States experience. Circulation. 2005;112(25):3823–3832. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.542266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oxford EM, Musa H, Maass K, Coombs W, Taffet SM, Delmar M. Connexin43 remodeling caused by inhibition of plakophilin-2 expression in cardiac cells. Circulation Research. 2007;101(7):703–711. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.154252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joshi-Mukherjee R, Coombs W, Musa H, Oxford E, Taffet S, Delmar M. Characterization of the molecular phenotype of two arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC)-related plakophilin-2 (PKP2) mutations. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5(12):1715–1723. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tandri H, Asimaki A, Dalal D, Saffitz JE, Halushka MK, Calkins H. Gap junction remodeling in a case of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia due to plakophilin-2 mutation. Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology. 2008;19(11):1212–1214. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sato PY, Musa H, Coombs W, et al. Loss of plakophilin-2 expression leads to decreased sodium current and slower conduction velocity in cultured cardiac myocytes. Circulation Research. 2009;105(6):523–526. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.201418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Westfall MV, Rust EM, Albayya F, Metzger JM. Adenovirus-mediated myofilament gene transfer into adult cardiac myocytes. Methods in Cell Biology. 1997;(52):307–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Person V, Kostin S, Suzuki K, Labeit S, Schaper J. Antisense oligonucleotide experiments elucidate the essential role of titin in sarcomerogenesis in adult rat cardiomyocytes in long-term culture. Journal of Cell Science. 2000;113(21):3851–3859. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.21.3851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Getsios S, Amargo EV, Dusek RL, et al. Coordinated expression of desmoglein 1 and desmocollin 1 regulates intercellular adhesion. Differentiation. 2004;72(8):419–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2004.07208008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moses RL, Claycomb WC. Disorganization and reestablishment of cardiac muscle cell ultrastructure in cultured adult rat ventricular muscle cells. Journal of Ultrastructure Research. 1982;81(3):358–374. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(82)90064-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kowalczyk AP, Bornslaeger EA, Borgwardt JE, et al. The amino-terminal domain of desmoplakin binds to plakoglobin and clusters desmosomal cadherin-plakoglobin complexes. Journal of Cell Biology. 1997;139(3):773–784. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.3.773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stappenbeck TS, Green KJ. The desmoplakin carboxyl terminus coaligns with and specifically disrupts intermediate filament networks when expressed in cultured cells. Journal of Cell Biology. 1992;116(5):1197–1209. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.5.1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bass-Zubek AE, Hobbs RP, Amargo EV, et al. Plakophilin 2: a critical scaffold for PKCα that regulates intercellular junction assembly. Journal of Cell Biology. 2008;181(4):605–613. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200712133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gerull B, Heuser A, Wichter T, et al. Mutations in the desmosomal protein plakophilin-2 are common in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Nature Genetics. 2004;36(11):1162–1164. doi: 10.1038/ng1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Angst BD, Khan LUR, Severs NJ, et al. Dissociated spatial patterning of gap junctions and cell adhesion junctions during postnatal differentiation of ventricular myocardium. Circulation Research. 1997;80(1):88–94. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kostin S, Hein S, Bauer EP, Schaper J. Spatiotemporal development and distribution of intercellular junctions in adult rat cardiomyocytes in culture. Circulation Research. 1999;85(2):154–167. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.2.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lowe JS, Palygin O, Bhasin N, et al. Voltage-gated Nav channel targeting in the heart requires an ankyrin-G-dependent cellular pathway. Journal of Cell Biology. 2008;180(1):173–186. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200710107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mohler PJ, Rivolta I, Napolitano C, et al. Nav1.5 E1053K mutation causing Brugada syndrome blocks binding to ankyrin-G and expression of Nav1.5 on the of cardiomyocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(50):17533–17538. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403711101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borisov AB, Martynova MG, Russell MW. Early incorporation of obscurin into nascent sarcomeres: implication for myofibril assembly during cardiac myogenesis. Histochemistry and Cell Biology. 2008;129(4):463–478. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0378-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pieperhoff S, Schumacher H, Franke WW. The area composita of adhering junctions connecting heart muscle cells of vertebrates. V. The importance of plakophilin-2 demonstrated by small interference RNA-mediated knockdown in cultured rat cardiomyocytes. European Journal of Cell Biology. 2008;87(7):399–411. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Franke WW, Schumacher H, Borrmann CM, et al. The area composita of adhering junctions connecting heart muscle cells of vertebrates—III: assembly and disintegration of intercalated disks in rat cardiomyocytes growing in culture. European Journal of Cell Biology. 2007;86(3):127–142. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kostin S, Schaper J. Tissue-specific patterns of gap junctions in adult rat atrial and ventricular cardiomyocytes in vivo and in vitro. Circulation Research. 2001;88(9):933–939. doi: 10.1161/hh0901.089986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Franke WW, Borrmann CM, Grund C, Pieperhoff S. The area composita of adhering junctions connecting heart muscle cells of vertebrates. I. Molecular definition in intercalated disks of cardiomyocytes by immunoelectron microscopy of desmosomal proteins. European Journal of Cell Biology. 2006;85(2):69–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lewis JE, Jensen PJ, Wheelock MJ. Cadherin function is required for human keratinocytes to assemble desmosomes and stratify in response to calcium. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 1994;102(6):870–877. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12382690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amagai M, Fujimori T, Masunaga T, et al. Delayed assembly of desmosomes in keratinocytes with disrupted classic-cadherin-mediated cell adhesion by a dominant negative mutant. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 1995;104(1):27–32. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12613462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pieperhoff S, Franke WW. The area composita of adhering junctions connecting heart muscle cells of vertebrates. VI. Different precursor structures in non-mammalian species. European Journal of Cell Biology. 2008;87(7):413–430. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wahl JK, Sacco PA, McGranahan-Sadler TM, Sauppé LM, Wheelock MJ, Johnson KR. Plakoglobin domains that define its association with the desmosomal cadherins and the classical cadherins: identification of unique and shared domains. Journal of Cell Science. 1996;109(5):1143–1154. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.5.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Witcher LL, Collins R, Puttagunta S, et al. Desmosomal cadherin binding domains of plakoglobin. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(18):10904–10909. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kowalczyk AP, Hatzfeld M, Bornslaeger EA, et al. The head domain of plakophilin-1 binds to desmoplakin and enhances its recruitment to desmosomes. Implications for cutaneous disease. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(26):18145–18148. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith EA, Fuchs E. Defining the interactions between intermediate filaments and desmosomes. Journal of Cell Biology. 1998;141(5):1229–1241. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.5.1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lampe PD, Copper CD, King TJ, Burt JM. Analysis of Connexin43 phosphorylated at S325, S328 and S330 in normoxic and ischemic heart. Journal of Cell Science. 2006;119(16):3435–3442. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dupont E, Matsushita T, Kaba RA, et al. Altered connexin expression in human congestive heart failure. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2001;33(2):359–371. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Danik SB, Liu F, Zhang J, et al. Modulation of cardiac gap junction expression and arrhythmic susceptibility. Circulation Research. 2004;95(10):1035–1041. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000148664.33695.2a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Q, Shen J, Splawski I, et al. SCN5A mutations associated with an inherited cardiac arrhythmia, long QT syndrome. Cell. 1995;80(5):805–811. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90359-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rook MB, Alshinawi CB, Groenewegen WA, et al. Human SCN5A gene mutations alter cardiac sodium channel kinetics and are associated with the Brugada syndrome. Cardiovascular Research. 1999;44(3):507–517. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00350-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schott J-J, Alshinawi C, Kyndt F, et al. Cardiac conduction defects associate with mutations in SCN5A. Nature Genetics. 1999;23(1):20–21. doi: 10.1038/12618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hashemi SM, Hund TJ, Mohler PJ. Cardiac ankyrins in health and disease. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2009;47(2):203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McEwen DP, Isom LL. Heterophilic interactions of sodium channel β1 subunits with axonal and glial cell adhesion molecules. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(50):52744–52752. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405990200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Malhotra JD, Koopmann MC, Kazen-Gillespie KA, Fettman N, Hortsch M, Isom LL. Structural requirements for interaction of sodium channel β1 subunits with ankyrin. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(29):26681–26688. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202354200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goldin AL, Barchi RL, Caldwell JH, et al. Nomenclature of voltage-gated sodium channels. Neuron. 2000;28(2):365–368. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Malhotra JD, Chen C, Rivolta I, et al. Characterization of sodium channel α- and β-subunits in rat and mouse cardiac myocytes. Circulation. 2001;103(9):1303–1310. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.9.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Papadatos GA, Wallerstein PMR, Head CEG, et al. Slowed conduction and ventricular tachycardia after targeted disruption of the cardiac sodium channel gene Scn5a. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99(9):6210–6215. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082121299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McNair WP, Ku L, Taylor MRG, et al. SCN5A mutation associated with dilated cardiomyopathy, conduction disorder, and arrhythmia. Circulation. 2004;110(15):2163–2167. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000144458.58660.BB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brackenbury WJ, Djamgoz MBA, Isom LL. An emerging role for voltage-gated Na+ channels in cellular migration: regulation of central nervous system development and potentiation of invasive cancers. Neuroscientist. 2008;14(6):571–583. doi: 10.1177/1073858408320293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brackenbury WJ, Isom LL. Voltage-gated Na+ channels: potential for β subunits as therapeutic targets. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets. 2008;12(9):1191–1203. doi: 10.1517/14728222.12.9.1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]