Abstract

Deletions at 16p13.11 are associated with schizophrenia, mental retardation, and most recently idiopathic generalized epilepsy. To evaluate the role of 16p13.11 deletions, as well as other structural variation, in epilepsy disorders, we used genome-wide screens to identify copy number variation in 3812 patients with a diverse spectrum of epilepsy syndromes and in 1299 neurologically-normal controls. Large deletions (> 100 kb) at 16p13.11 were observed in 23 patients, whereas no control had a deletion greater than 16 kb. Patients, even those with identically sized 16p13.11 deletions, presented with highly variable epilepsy phenotypes. For a subset of patients with a 16p13.11 deletion, we show a consistent reduction of expression for included genes, suggesting that haploinsufficiency might contribute to pathogenicity. We also investigated another possible mechanism of pathogenicity by using hybridization-based capture and next-generation sequencing of the homologous chromosome for ten 16p13.11-deletion patients to look for unmasked recessive mutations. Follow-up genotyping of suggestive polymorphisms failed to identify any convincing recessive-acting mutations in the homologous interval corresponding to the deletion. The observation that two of the 16p13.11 deletions were larger than 2 Mb in size led us to screen for other large deletions. We found 12 additional genomic regions harboring deletions > 2 Mb in epilepsy patients, and none in controls. Additional evaluation is needed to characterize the role of these exceedingly large, non-locus-specific deletions in epilepsy. Collectively, these data implicate 16p13.11 and possibly other large deletions as risk factors for a wide range of epilepsy disorders, and they appear to point toward haploinsufficiency as a contributor to the pathogenicity of deletions.

Introduction

Although common SNPs have been shown to play at most a modest role in most neuropsychiatric diseases, a growing body of evidence connects large deletions and duplications, or copy number variants (CNVs), to schizophrenia, autism, and mental retardation.1–5 Recently, deletions at 15q13.3 and 16p13.11, previously implicated in schizophrenia2 and mental retardation,6 have now been associated with idiopathic generalized epilepsy.7,8 These findings add epilepsy to the growing list of neuropsychiatric conditions with overlapping susceptibility conferred by copy number variation.

Here, we report a genome-wide screen evaluating the role of large, rare CNVs in patients affected with a wide range of seizure disorders, including both partial and generalized seizure disorders. We also explore possible mechanisms of pathogenicity for large deletions in neuropsychiatric disease.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

Patients with either focal (> 90%) or generalized epilepsy were drawn from four sites making up the EPIGEN Consortium (Brussels, Belgium [n = 550]; Dublin, Ireland [n = 624]; Durham, NC, USA [n = 755]; and London, UK [n = 1237]), with additional cohorts from the GenEpA Consortium (Finland [n = 417], Switzerland [n = 229]). All patients were asked to participate in a study investigating the genetics of epilepsy during routine clinical appointments at each site, in accordance with institutional standards. All patients had a definite diagnosis of epilepsy according to International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) definitions. Seizure types and epilepsy syndromes were classified according to the ILAE classifications. DNA was extracted from primary (untransformed) cells from either a blood (n = 3729) or brain (n = 63) sample. No recruited patients with neuropsychiatric disease and/or mental retardation were excluded if they met the criteria of having a genetically unexplained seizure disorder. Information about family history was provided by the patient, but blood samples for DNA were obtained only from consenting family members if the primary patient had a putative epilepsy-associated deletion and the individual consented to the follow-up investigations.

For comparison, we used controls from Finland and Switzerland who had no neuropsychiatric condition (n = 546). In addition, we evaluated 755 cognitively normal control subjects who had taken part in the Genetics of Memory study at Duke University and had undergone cognitive testing. These subjects were used to assess the frequency of epilepsy-associated deletions in controls and to assess the effects of epilepsy-associated CNVs on cognitive function. DNA from control subjects was obtained from blood (n = 52) or saliva (n = 1247). Controls used in this study partially overlap controls used in the Need et al. 2009 schizophrenia (SCZD [MIM 181500]) study.2 A total of 753 controls overlapped with this study; there were 546 unique controls evaluated here and 840 unique neuropsychiatrically normal controls evaluated in Need et al.2 In some cases, patients were recontacted with a request for additional blood samples from family members, blood samples for expression assessments, and additional blood samples for DNA when necessary. We were successful in obtaining additional samples only in a subset of patients.

All phenotypic data and samples were collected in accordance with the ethical standards set forth by the Duke University Institutional Review Board, Durham, NC, USA; Ethics Committee Erasme Hospital and Ethics Committee Gasthuisberg, Brussels, Belgium; Joint Research Ethics Committee of the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery and the Institute of Neurology, London, UK; Kantonale Ethik-Kommission, Zurich, Switzerland; Beaumont Hospital Ethics Committee, Dublin, Ireland; and the Advisory Board on Health Care Ethics, Sub-Committee on Medical Research Ethics, Helsinki, Finland.

Genome-wide Genotyping

DNA from all individuals were genotyped on the Illumina Human 610-Quad genome-wide genotyping array, with the exception of a subset run on other chips, including HumanHap 1M (n = 4), HumanHap 550K (n = 131), and HumanHap 317K (n = 47). All samples were genotyped in the Institute for Genome Sciences & Policy Genotyping Facility, and quality control measures were standardized across all batches.

CNV Calling

The CNV calls were generated with the PennCNV software (version 2008 June 26), with the use of the log R ratio (LRR) and B allele frequency (BAF) for all SNPs and CNV probes included on the genotyping chips. Standard PennCNV quality control checks were used for excluding unreliable samples, including LRR standard deviation (SD) greater than 0.28, BAF median greater than 0.55 or less than 0.45, BAF drift greater than 0.002, or a waviness factor of greater than 0.04 or less than −0.04. Individual CNVs were excluded if the PennCNV-generated confidence score was less than 10, if they were called on the basis of fewer than ten SNPs or CNV probes, if the CNV spanned a centromere, and, finally, if the CNVs overlapped at least 50% with regions previously described as being prone to false positives due to somatic mutations.2

Deletions greater than 1 Mb and specific regions associated with epilepsy were visually inspected in Illumina Beadstudio for calling accuracy. Specifically, in cases of a subject having two or more CNVs called within 1 Mb of each other, the uncalled region was inspected for the genotyping quality. If only SNPs that failed genotyping quality control were used to establish a break in the CNV, it was assumed to be continuous.

Confirmation of a Subset of Deletions

Deletions were confirmed in a subset of patients via comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) (Roche Nimblegen, HG18 WG Tiling CGH 2.1M v2). Deletions at 16p13.11 were confirmed via quantitative real-time PCR amplification of genomic DNA. Standard protocol was used for amplificiation, with β-globin used as an internal reference. In brief, multiplex 10 μl reactions containing a final concentration of 900 nM of each primer [ (β-globin [forward: 5′-GGCAACCCTAAGGTGAAGGC-3′, reverse: 5′-GGTGAGCCAGGCCATCACTA-3′]; 16p13.11 [forward: 5′-GATCAGTCCCCAAACCGAAC-3′, reverse: 5′-CGCCATCTCTGTTCTTGCTG-3′]), 250 nM of each fluorescently labeled probe (β-globin: VIC, 5′-CATGGCAAGAAAGTGCTCGGTGCCT-3′; 16p13.11: FAM, 5′-AGGTGGCCCAGCCTCTGGGC-3′), and 10 ng of genomic DNA were run in duplicate (Taqman Universal mastermix, Applied Biosystems [PCR conditions: 50°C × 2 min, 95°C × 10 min, 40 cycles of 95°C × 15 s, 60°C × 1 min, then 4°C]). A standard curve was constructed for β-globin and the locus within 16p13.11 on the basis of the number of cycles needed to achieve a threshold fluorescence for fixed amounts of DNA from subjects with two copies 16p13.11 (based on PennCNV calls), ranging from 0.25 to 200 ng. Relative copy number in the test sample was estimated by extrapolating from the standard curves an estimated DNA amount at each locus on the basis of the number of cycles needed to reach the defined threshold for that sample, then taking a ratio (16p13.11/β-globin). An average ratio, with an associated coefficient of variation between replicates of less than 25%, of greater than 0.25 and less than 0.75 was considered to be a single-copy deletion at 16p13.11. Correspondingly, a two-copy state at the 16p13.11 locus was called if the ratio was greater than 0.75 and less than 1.25.

Expression Analyses in Blood Samples

Blood samples from a subset of patients with epilepsy-associated deletions were studied for effects on gene expression. Blood was collected in Tempus tubes (Applied Biosystems) and extracted via a standard protocol. Quality of RNA was assessed on an Agilent Bioanalyzer. Gene transcript levels were estimated with Illumina Human HT-12 v3 microarrays (standard protocols). Data were normalized via robust spline normalization in R (v2.8.0). Only transcripts whose normalized expression in a set of n = 8 controls exceeded the mean normalized expression values across all transcripts evaluated on the array were included in this analysis, ensuring the highest sensitivity for detection of an effect. Data generated in this experiment is publically available through Gene Expression Omnibus (accession number GSE20977).

Deletion Inheritance

When available, blood samples were obtained from family members, and DNA was extracted and analyzed on the Illumina 610-Quad genotyping array. The relevant regions were visually inspected (in Beadstudio) and statistically assessed in PennCNV for ascertainment of copy number status. Relationships were confirmed with the use of genome-wide SNP-genotyping data.

Capture and Next-Generation Sequencing of the 16p13.11 Locus in Patients with a Deletion

A 3.3 Mb region spanning the deleted interval located at 16p13.11 was captured via an in-solution method (Agilent SureSelect). The captured intervals excluded large nongenic regions and included the following positions along chromosome 16 (chr16): 14380454–16405334, 16572078–16574838, 16658507–16666547, 17015093–17482240, and 18309264–18762264 (NCBI Build 36.1). The isolated region was sequenced in a single lane on the Illumina Genome Analyzer. The sequencing reads (two paired-end 75 bp fragments) were aligned to reference with the use of BWA software.9 SAMTools software was used to call SNP and indel variants.10 Variants were considered only if they had a consensus and SNP quality exceeding 20, if there were at least three reads supporting the variant, and if they were located within the PennCNV-estimated deletion boundaries.

Results

Evaluation of 15q13.3 and 16p13.11 Epilepsy-Associated Risk Loci

First, we evaluated three epilepsy-risk loci previously implicated in idiopathic generalized forms of epilepsy: 15q13.3,7,11 15q11.2,8 and 16p13.11.2,8 We observed one patient with a deletion spanning 15q13.3 (15q13.2–q13.3, Table 1). Consistent with previous reports, this patient has a diagnosis of juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (Table S1, available online), a form of idiopathic generalized epilepsy. The absence of 15q13.3 deletions in any of the more than 3000 focal epilepsy patients suggests that its involvement in epilepsy disorders is specific to generalized forms, despite the fact that deletions in this region have been associated with nonspecific effects in neuropsychiatric disease risk.3,7,12

Table 1.

List of Heterozygous Deletions Greater than 1 Mb Observed in Epilepsy Patients

| Cytoband | Size (Mb) | Gene Lista |

|---|---|---|

| 1p21.2–p21.1 | 5.6 | EDG1, AMY1C, AMY1B, AMY1A, SLC35A3, COL11A1, VCAM1, LRRC39, RNPC3, SLC30A7, RTCD1, DBT, AMY2B, AMY2A, AGL, CCDC76, DPH5, HIAT1, PALMD, AL359760.10, OLFM3, CDC14A, SASS6, EXTL2, GPR88, FRRS1, AL356280.21 |

| 1q21.1b | 1.2 | AL139152.7, ACP6, BCL9, GJA8, GJA5, RP11-94I2.2, FMO5, AL049742.8, FAM108A3, CHD1L, PRKAB2, AL356004.9 |

| 1q21.1b | 1.1 | AL139152.7, ACP6, BCL9, GJA8, GJA5, RP11-94I2.2, FMO5, AL049742.8, FAM108A3, CHD1L, PRKAB2 |

| 3q11.2 | 4.3 | ARL6, OR5H1, AC110491.5, AC026100.19, AC024218.17, DHFRL1, STX19, NSUN3, PROS1, MINA, EPHA6, ARL13B, OR5AC2 |

| 4q32.3 | 1.2 | SPOCK3 |

| 4q35.1–q35.2 | 1.5 | F11, AC096659.1, SORBS2, PDLIM3, TLR3, KLKB1, FAT, FAM149A, MTNR1A, CYP4V2 |

| 4q35.2c | 1.97 | AC093909.2, AC020698.4, TRIML2, TRIML1, ZFP42 |

| 5q12.3–q13.2c | 6.1 | MAST4, OCLN, PMCHL2, AC146944.1, CCNB1, CCDC125, CENPH, CD180, SMN2, SMN1, SFRS12, MCCC2, AC145102.2, MRPS36, AC131392.2, AC139277.2, AC139834.2, AC145146.2, TAF9, AC145132.2, GTF2H2, CDK7, BDP1, MRPS27, MAP1B, SLC30A5, CARTPT, AC140134.2, MARVELD2, RAD17, NAIP, SERF1A, AC145138.2, AC092373.2, AC139495.2, PIK3R1, AC139272.3 |

| 5q15 | 1.4 | RIOK2, LIX1, LNPEP, PCSK1, ARTS-1, CAST, ELL2, LRAP |

| 5q23.1 | 1 | None |

| 5q34 | 3 | MAT2B, GABRB2, GABRA6, HMMR, NUDCD2, ATP10B, GABRG2, GABRA1, CCNG1, GLRXL |

| 6q12 | 5.2 | AL450394.9, BAI3, AL356454.15, AL445677.1, AL109922.9, AL450324.10, EGFL11, AL365217.10, EGFL10 |

| 7q21.11–q21.13 | 12 | SEMA3A, AC002064.2, GRM3, PCLO, GNAI1, GTPBP10, STEAP4, MAGI2, RUNDC3B, SRI, STEAP2, STEAP1, CLDN12, ABCB4, DBF4, ABCB1, CROT, SLC25A40, ZNF804B, ADAM22, HGF, C7orf23, AC004082.1, DMTF1, KIAA1324L, TP53AP1, AC002081.1, PFTK1, AC002127.1, CD36, CACNA2D1, GNAT3, SEMA3E, SEMA3D, SEMA3C |

| 7q31.32–q31.33 | 2.9 | AP4M1, POT1, GPR37, SPAM1, HYAL4, GRM8 |

| 8q11.22–q11.23 | 2 | AC012413.10, SNTG1 |

| 9p23 | 1.1 | None |

| 9p24.3–p23 | 9.8 | INSL6, INSL4, AL583805.7, KIAA0020, VLDLR, KANK1, SLC1A1, CDC37L1, AL353638.15, ERMP1, RANBP6, PPAPDC2, CD274, RFX3, SMARCA2, KCNV2, UHRF2, GLDC, MLANA, AK3, TPD52L3, AL365202.19, DMRT3, AL161450.14, DMRT2, DMRT1, RCL1, JMJD2C, C9orf46, AL354941.10, GLIS3, KIAA1432, C9orf123, JAK2, PTPRD, KIAA2026, RLN2, RLN1, C9orf68, IL33, DOCK8, C9orf66, PDCD1LG2 |

| 10q11.21–q11.23c | 5.6 | AL591684.7, CHAT, LRRC18, AC027674.10, MSMB, ANXA8L2, ANXA8L1, TIMM23, ANXA8, AL603966.9, NCOA4, C10orf73, C10orf72, MAPK8, TIMM23B, C10orf71, FRMPD2, AL672187.12, FRMPD2L2, DRGX, OGDHL, PPYR1, RBP3, AL954360.3, AL450334.15, AL356056.22, CTGLF5, CTGLF4, CTGLF3, AL391137.11, PTPN20B, PTPN20A, SYT15, CTGLF2, C10orf64, ARHGAP22, AL603965.10, BX649215.1, PDZD5A, PARG, C10orf128, PGBD3, GDF10, GDF2, C10orf53, ANTXRL, AL442003.8, GPRIN2, AL731733.9, ZNF488, SLC18A3 |

| 12p13.32–p13.31 | 1.6 | KCNA5, NDUFA9, RAD51AP1, KCNA1, AC007848.11, DYRK4, NTF3, VWF, GALNT8, FGF6, AC008012.8, AKAP3, KCNA6, TMEM16B |

| 13q21.32–q21.33 | 4.6 | KLHL1, PCDH9 |

| 15q11.2 | 1.3 | AC025884.28, AC026495.13, OR4N4, OR4M2, AC131280.9, AC134980.3, AC126335.16, A26B1 |

| 15q11.2 | 1 | AC025884.28, OR4N4, OR4M2, AC131280.9, AC134980.3, AC126335.16, A26B1 |

| 15q13.2–q13.3 | 1.5 | CHRNA7, MTMR15, MTMR10, AC004460.1, TRPM1, ARHGAP11B, KLF13, OTUD7A |

| 16p12.3 | 1.5 | AC109446.2, XYLT1 |

| 16p13.11 | 1.2 | ABCC6, KIAA0430, ABCC1, AC130651.2, NDE1, C16orf45, MPV17L, MYH11, C16orf63, RRN3, NTAN1, PDXDC1 |

| 16p13.11 | 1.2 | NDE1, C16orf45, KIAA0430, AC130651.2, ABCC1, MYH11, C16orf63, RRN3, NTAN1, PDXDC1, ABCC6 |

| 16p13.11 | 1.2 | ABCC6, KIAA0430, ABCC1, AC130651.2, NDE1, C16orf45, MPV17L, MYH11, C16orf63, RRN3, NTAN1, PDXDC1 |

| 16p13.11–p12.3c | 2.7 | ABCC6, KIAA0430, ABCC1, AC130651.2, NDE1, XYLT1, C16orf45, MPV17L, MYH11, NOMO3, AC136619.3, C16orf63, AC138969.2, AC109446.2 |

| 16p13.11–p12.3c | 2.9 | ABCC6, KIAA0430, ABCC1, AC130651.2, NDE1, XYLT1, C16orf45, MPV17L, MYH11, NOMO3, AC136619.3, C16orf63, AC138969.2, AC109446.2 |

| 17p12d | 1.4 | AC005838.2, FAM18B2, AC005863.1, HS3ST3B1, COX10, TEKT3, CDRT4, PMP22, CDRT15 |

| 17p12 | 1.4 | PMP22, CDRT15, TEKT3, COX10, HS3ST3B1, CDRT4, AC005863.1, FAM18B2 |

| 17p12 | 1.4 | AC005838.2, FAM18B2, AC005863.1, HS3ST3B1, COX10, TEKT3, CDRT4, PMP22, CDRT15 |

| 17q12e | 1.4 | LHX1, AP1GBP1, ZNHIT3, PIGW, C17orf78, HNF1B, AC003042.2, MYO19, DUSP14, MRM1, DDX52, TADA2L, ACACA, AATF, ZNF403 |

| 18p11.32–p11.31 | 5 | THOC1, EMILIN2, KNTC2, AP002478.3, TGIF,fTYMS, C18orf56, DLGAP1, ENOSF1, SMCHD1, CLUL1, METTL4, COLEC12, CETN1, MYOM1, YES1, USP14, LPIN2, AP001011.6, C18orf2, AP005329.2, ADCYAP1, AP005329.1 |

| 19p12 | 1 | AC024563.6, AC011467.7, ZNF98, AC022145.8, ZNF208, ZNF257, ZNF676, AC008626.6 |

| 19p12 | 1 | AC024563.6, AC011467.7, ZNF98, AC022145.8, ZNF208, ZNF257, ZNF676, AC008626.6 |

Deletions observed in controls include 1q21.1 (chr1: 144838594–145848182), 14q31.3 (chr14: 86328510–87722142), and 18p11.32 (chr18: 755920–2473514).

Fully and partially included genes based on PennCNV-inferred boundaries and the Ensembl database.

Similarly sized deletion observed in a neurologically normal control.

Boundaries redefined with visual inspection (see Subjects and Methods).

Deletion identified in brain tissue specimen procured during therapeutic lobectomy.

Similarly sized duplications were also observed exclusively in cases.

No malformation observed on brain MRI.

At the second epilepsy-risk locus, 15q11.2,8 we observed 24 patients and three controls with a deletion larger than 300 kb (one-sided Fisher's exact test, p = 0.06). Two additional cases and three controls had smaller deletions in the region (< 100 kb). Two of the 24 patients (∼8%) with a deletion greater than 300 kb in the previously reported risk region had a diagnosis of generalized epilepsy, which is approximately equal to the percentage of patients with generalized epilepsy disorders in the cohort studied. In our analysis, this region does not appear to be clearly associated with partial or generalized epilepsy.

At the epilepsy-associated 16p13.11 locus, we found 23 patients with deletions greater than 100 kb in the region, whereas the largest deletion in controls in this region is 16 kb (Figure 1, one-tailed Fisher's exact test, p = 0.001). Although the deletions in epilepsy patients apparently vary in size, all but three cover a core set of seven genes, including NDE1 (MIM 609449, Figure 1), a gene with suspected involvement in human cortical development.13 Interestingly, we do not see any straightforward phenotypic similarities within the set of patients with 16p13.11 deletions, even among identically sized deletions (Table 2), including instances of both partial and generalized epilepsy. We also see no increased frequency of psychiatric illness in patients with 16p13.11 deletions, though such an increase might have been expected given the reported role of this deletion in schizophrenia.2 Psychiatric phenotypes were observed in only four out of 23 patients, which does not exceed the rate of psychiatric comorbidities in the general epilepsy patient population.14 All patients with a 16p13.11 deletion were adults (>18 yrs of age). Finally, 16p13.11 deletions have previously been associated with mental retardation or multiple congenital abnormalities (MR/MCA), with epilepsy reported in approximately 25% of MR/MCA patients.6 Although some of the patients have the clinical impression of lower than average intelligence quotients and dysmorphism (Table 2), none have MR/MCA.

Figure 1.

16p13.11 Deletions Observed Exclusively in Epilepsy Patients

A total of 23 deletions were observed in the region (indicated by blue bars marking the locations of patient-specific deletions), 22 of them sharing a common segment including or disrupting the NDE1 gene. Deletions in the same patient that were called in tandem and separated only by SNPs that failed genotyping quality control were assumed to be continuous and merged together (shown as a single bar in this display). Using the exact same criteria in controls, we observed no deletions exceeding 16 kb. Segmental duplications flanking the boundaries of these deletions are shown.

Figure produced in part with the use of the UCSC Genome Browser.

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristics of Patients with a 16p13.11 Deletion

| Chr16 Position (PennCNV) (Mb) | Size of Event (Mb) | Descent | Syndrome | Seizure Types | MRI | Drug Responsiveness | Deletion Acquisition/Seizure-Related Family History | Cognitive and/or Psychiatric Comorbidities, Dysmorphism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15.70–15.86 | 0.2 | British | partial epilepsy, focus unknown, cryptogenic | CPS, SGTCS | normal | seizure-free on monotherapy | unknown/none | obsessive-compulsive disorder, no cognitive or other psychiatric disorder. |

| 15.44–16.20a,b | 0.8 | North American, European | juvenile absence epilepsy | absences, GTCS | normal | seizure-free on dual therapy | inherited from mother/grandparent with epilepsy | no indication for cognitive/psychiatric testing |

| 15.39–16.19a,b | 0.8 | Mizrahi Jewish | partial epilepsy, focus unknown, cryptogenic | SPS, CPS, SGTCS | normal | seizure-free on monotherapy | inherited from mother/family history of febrile seizures | obsessive-compulsive disorder, learning disability, VIQ 77, PIQ 62 |

| 15.39–16.19 | 0.8 | North American, European | unclassified epilepsy | Dialeptic seizures, myoclonic seizures, GTCS | unilateral parietal encephalomalacia | refractory | unknown/none | no indication for cognitive/psychiatric testing |

| 15.39–16.20c | 0.8 | Northwest European | childhood absence epilepsy | Absences | aspecific white matter lesions | refractory | unknown/mother and two maternal cousins with epilepsy | no indication for cognitive/psychiatric testing |

| 15.39–16.20 | 0.8 | Italian | frontal lobe epilepsy, symptomatic | CPS, SGTCS | extensive right frontal cystic encephalomalacia | several seizure-free periods of ∼1 year, but not currently seizure-free | unknown/none | Gilles de la Tourette syndrome, no indication for cognitive testing |

| 15.39–16.20c | 0.8 | North American, European | juvenile absence epilepsy | Absences, GTCS | normal | refractory | unknown/none | no indication for cognitive/psychiatric testing |

| 15.39–16.20 | 0.8 | British | temporal lobe epilepsy, cryptogenic | SGTCS | normal | refractory | unknown/none | no indication for cognitive/psychiatric testing |

| 15.39–16.20c,d | 0.8 | Finnish | temporal lobe epilepsy, cryptogenic | SGTCS | normal | refractory | unknown/data unavailable | no indication for cognitive/psychiatric testing |

| 15.39–16.20c | 0.8 | Irish | temporal lobe epilepsy, symptomatic | SPS, CPS, SGTCS | postoperative signal changes in white matter | refractory | unknown/none | low-normal cognitive function, VIQ 82, PIQ 76. No psychiatric disorders. |

| 15.39–16.20a,b,e | 0.8 | North American, European | unclassified epilepsy | GTCS | normal | refractory | inherited from mother/none | no indication for cognitive/psychiatric testing, Streeter's bands and syndactyly |

| 15.39–16.20a,b | 0.8 | North American, European | unclassified epilepsy | Dialeptic seizures, GTCS | normal | refractory | did not inherit from mother, paternal transmission unknown/none | no indication for cognitive/psychiatric testing. Clinical impression of low-normal IQ, mild dysmorphism |

| 15.37–16.19 | 0.8 | British | partial epilepsy, focus unknown, cryptogenic | CPS | normal | seizure-free on dual therapy | unknown/strong family history of epilepsy, several affected members on both paternal and maternal sides of family | no indication for cognitive/psychiatric testing |

| 15.37–16.20c | 0.8 | Northwest European | temporal lobe epilepsy, cryptogenic | SPS, SGTCS | normal | refractory | unknown/none | no indication for cognitive/psychiatric testing |

| 15.39–16.23c | 0.8 | British | temporal lobe epilepsy, cryptogenic | SPS, CPS, SGTCS | normal | refractory | unknown/two maternal sibs with epilepsy | psychotic depression postdating onset of epilepsy |

| 15.39–16.23 | 0.8 | African descent | temporal lobe epilepsy, symptomatic | CPS | HS | refractory | unknown/none | no cognitive or psychiatric disorder |

| 15.35–16.20c,d | 0.8 | Northwest European | temporal lobe epilepsy, symptomatic | SPS, CPS, SGTCS | HS, nonspecific white matter changes | refractory | unknown/none | no indication for cognitive/psychiatric testing |

| 15.02–16.19c | 1.2 | British | frontal lobe epilepsy, cryptogenic | CPS, SGTCS | nonspecific bilateral periventricular white matter changes | refractory | unknown/two paternal relatives with epilepsy | normal cognitive function, psychosis on topiramate but no primary psychiatric history |

| 15.03–16.19a,b | 1.2 | African descent | juvenile absence epilepsy | Absences, GTCS | normal | refractory | de novo/none | no indication for cognitive/psychiatric testing |

| 15.10–16.23c,d | 1.2 | Irish | temporal lobe epilepsy, symptomatic | CPS, SGTCS | unilateral temporal lobe gliosis, affecting lateral neocortex | refractory | unknown/sibling with generalized epilepsy | no indication for cognitive/psychiatric testing |

| 16.77–18.26c | 1.5 | Northwest European | temporal lobe epilepsy, symptomatic | SPS, CPS, SGTCS | unilateral temporal stroke and abnormal ipsilateral hippocampal internal structure | rare seizures off antiepileptic drug treatment | unknown/none | cognitive problems secondary to the venous thrombosis (MMSE 27/30) |

| 15.39–18.08b | 2.7 | Northwest European | partial epilepsy, focus unknown, symptomatic | SGTCS | venous sinus thrombosis and small right frontal subdural hematoma | seizure-free on monotherapy | unknown/none | cognitive problems secondary to the venous thrombosis (MMSE 28/30 and Addenbrooke 89/100) |

| 15.39–18.26b | 2.9 | British | temporal lobe epilepsy, cryptogenic | SPS, CPS, SGTCS | normal | refractory | unknown/sibling with febrile seizures | no cognitive or psychiatric disorder |

Abbreviations are as follows: TLE, temporal lobe epilepsy; HS, hippocampal sclerosis (typical MRI with or without histological confirmation); SPS, simple partial seizures; CPS, complex partial seizures; SGTCS, secondarily generalized tonic clonic seizures; VNS, vagal nerve stimulator.

Evaluated in deletion-acquisition experiment.

Evaluated in expression analyses.

Sequenced along the intact homolog to search for deleterious recessive variants.

Patient has a putatively functional SNP in MPV17L.

Confirmed by array CGH.

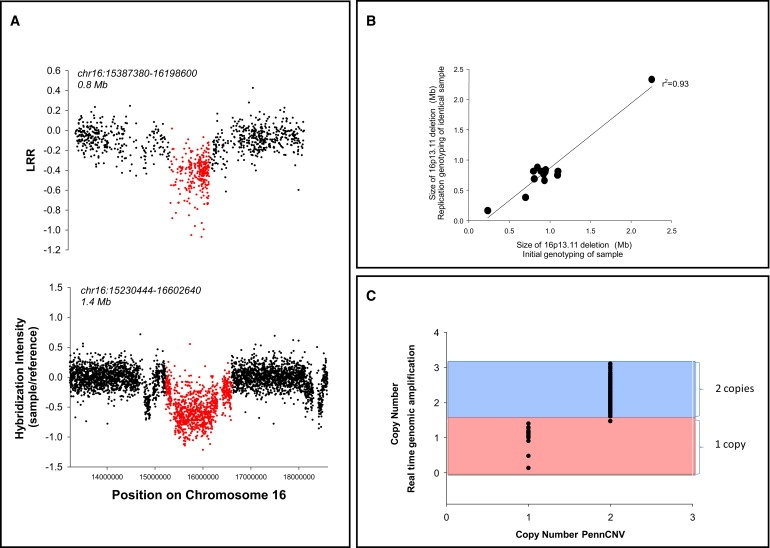

Confirmation of 16p13.11 Deletions

The DNA from one patient with a 16p13.11 deletion was analyzed via CGH (Figure 2A). The deletion was confirmed on the CGH array; however, the deletion boundaries were found to be larger (Figure 2A, chr16: 15.2–16.6, 1.4 Mb) than those inferred by PennCNV (chr16: 15.4–16.2, 811 kb). The extended boundaries estimated by CGH did not alter the genic content of the deletion. Additional confirmation of 16p13.11 deletions was also performed, including replication of the original PennCNV calls by regenotyping in a subset (Figure 2B) and by directly confirming the overall association statistics for the 16p13.11 region via quantitative real-time PCR in genomic DNA (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Confirmation of 16p13.11 Deletions

(A) CGH experiment confirming the 16p13.11 deletion. Intensity signals in a single patient with a 16p13.11 deletion detected via PennCNV on Illumina-based genotyping technology (top panel) compared to data collected on the same deletion patient via CGH (Roche NimbleGen, bottom panel). Deletion regions called by the two technologies are shown in red, and the coordinates defining the start and end points of the deletions are provided above each panel.

(B) A set of 14 individuals were regenotyped on the Illumina HumanHap 610 genotyping chips for replication of initial calls. All 14 deletions replicated, and the sizes of deletions called were highly correlated.

(C) Confirmation of the 16p13.11 deletion with the use of Taqman-based real-time genomic amplification.

Inheritance Patterns of 16p13.11 Deletions

We also investigated inheritance patterns for two individuals carrying 16p13.11 (n = 2) deletions by evaluating the CNV status at 16p13.11 in trios involving both parents of the proband. In one trio the deletion was de novo, whereas for the other proband the deletion was inherited from the mother (Table 2). In addition to the two trios, we also observed two other maternally inherited deletions at 16p13.11 in probands for which only the maternal sample was available (Table 2). In the three cases of inherited 16p13.11 deletions, the parent carriers are unaffected by epilepsy, but no neuropsychiatric testing was carried out on these individuals.

Mechanistic Evaluation of 16p13.11 Deletions

Expression Consequences of 16p13.11 Deletions in Lymphocytes

For seven of the 23 patients with 16p13.11 heterozygous deletions, we evaluated the effect of the deletion on gene expression of genes included in and nearby the deletion in lymphocytes. We extracted RNA from whole-blood samples of patients with deletions and measured transcriptome-wide expression. We evaluated two groups of genes in this analysis: (1) all genes within 1 Mb of the PennCNV-inferred deletion boundary but not included within it (“nearby” genes), and (2) genes included in each deletion (genes that are partly or entirely deleted). We used control samples with no 16p13.11 deletion (n = 8) to calculate SD for the distribution of gene expression for all highly expressed (expressed at level greater than the control group average) “nearby” and “included” genes for each deletion. We then determined, for each nearby and included transcript, the distance from the mean in SD units. All three highly expressed transcripts included within the PennCNV-estimated boundaries show a clear reduction in expression: C16orf63 (two-sided t test, p = 1 × 10−6), KIAA0430 (p = 0.006), and NDE1 (p = 5 × 10−5 [MIM 609449]) (Figure 3). No effects of the 16p13.11 deletions were detected in any nearby transcripts (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Expression Effects of a Subset of 16p13.11 Deletions in Leukocytes

(A) Shown is the number of SDs away from the group mean for highly expressed transcripts located within the deletion (red) and a 1 Mb surrounding region (blue). Data are summarized for seven patients with the 16p13.11 deletion (mean ± standard error of the mean) compared to eight controls.

(B) Shown is the number of SDs away from the mean for each individual transcript evaluated in individual subjects. The deleted region in each patient is highlighted in yellow. Position of the transcript along the x axis in both panels is equal to the position of the midpoint of the probe measuring the transcript.

Screen for Recessive Mutations on the Homologous Chromosome

We next sought to identify mutations present on the homologous region of the intact chromosome that might act as recessive risk factors for epilepsy with effects that are “unmasked” by the deletion. We designed a hybridization-based capture experiment that enriched for 2.9 Mb within a stretch of 3.3 Mb, corresponding to ∼1 Mb surrounding the outermost PennCNV-estimated boundaries of deletions observed in the 16p13.11 region, large intergenic regions excluded (Figure 4). We then isolated this sequence in ten individuals of European ancestry with deletions (Figure 4, Table 2) and sequenced the result in a single lane per individual on an Illumina Genome Analyzer. The 2.9 Mb of captured sequence was sequenced across all individuals at an average read depth of 50 (averages within individuals ranged between 36 and 78), with greater than 5-fold coverage for at least 93% of the sequenced region in each subject. For CCDS (Consensus CoDing Sequence, National Center for Biotechnology Information [NCBI]) genes, 96 ± 1% of bases included within exons were covered at least 5-fold, compared to < 0.1% bases covered in exons not targeted in the capture. We then identified all putative functional single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and indels (nonsynonymous, protein-truncating, or splice-site variants) within the patient-specific PennCNV-estimated deletion boundaries. We identified in total 12 SNVs and no indels meeting the functional criteria. We then evaluated the homozygote frequency of these 12 variants in controls by using both the HapMap CEU population (Utah residents with ancestry from northern and western Europe) and a set of 13 samples that have been whole-genome sequenced in our lab for other projects. We excluded a variant as a candidate for conferring epilepsy risk in homozygote (or hemizygote) form if its homozygote frequency in the HapMap CEU population exceeded 5% or if two or more homozygotes were observed in the control individuals for which whole-genome sequence was available. Of the 12 assumed functional variants identified, only four remained after this filtering process, including rs72774859 in MPV17L, rs45511401 in ABCC1 (MIM 158343), and SNVs located at chr16 positions 15635091 (KIAA0430) and 15718503 (MYH11 [MIM 160745]). The latter two variants were observed in the same subject and were not considered likely candidates. The MPV17L splice-site variant (rs72774859), however, was observed in three subjects with a consistent diagnosis of temporal lobe epilepsy with secondary generalized tonic-clonic seizures (marked on Table 2). We therefore genotyped this SNV in the remaining 13 patients harboring a 16p13.11 deletion, as well as in 2997 epilepsy cases lacking a deletion of 16p13.11 and in 1801 nonepileptic controls. No additional patients with a 16p13.11 deletion carried the variant on the intact homolog. We observed five homozygotes among the epilepsy cases (including two with an incongruous phenotype) and two homozygotes within the nonepileptic controls. The SNV in ABCC1 (rs45511401) was also genotyped in the larger cohort and was likewise observed in homozygote form in neuropsychiatrically normal controls. Collectively, these data provide no evidence for the unmasking of functional, recessive variants contributing either to the pathogenicity or to the pleiotropic effects of deletions at chromosome 16p13.11.

Figure 4.

Screen for Recessive Variants on the Intact Chromosome of 16p13.11

Individuals with deletions (indicated by the blue bars marking the locations of patient-specific deletions) were selected for a hybridization-based capture and next-generation sequencing experiment in which the intact homologous stretch of chromosome corresponding the deleted segment was sequenced in order to screen for pathogenic recessive mutations that may contribute to the risk associated with the deletion. The average read depth averaged across all ten subjects at each base is shown, and purple bars below mark the regions targeted in the hybridization-based capture.

Figure produced in part with the use of the UCSC Genome Browser.

Enrichment of Large Heterozygous Deletions in Epilepsy Patients

A total of six of the 23 16p13.11 deletions were larger than 1 Mb (Table 2). To investigate a possible class effect of deletions of this magnitude, we screened for additional deletions larger than 1 Mb in patients and controls. We found that deletions of more than 1 Mb occurred in 36/3812 epilepsy patients but only in 3/1299 controls (two-sided Fisher's exact test, p = 0.009), whereas deletions larger than 2 Mb occurred in 14 patients and no controls (p = 0.028). Most of the deletions greater than 1 Mb in the epilepsy patients are observed only once, with a total of 21 regions having a large deletion present in only one patient in the entire cohort (Table 1). Many of the genes included in the deletions greater than 1 Mb are implicated in epilepsy pathophysiology (Table 1). Of the 292 annotated genes covered by these CNVs, three carry mutations responsible for Mendelian epilepsies (KCNA1 [MIM 176260],15 GABRA1 [MIM 137160],16 and GABRG2 [MIM 137164]17–20), a finding unlikely to occur by chance given a total of 13 genes known to be responsible for Mendelian forms of idiopathic epilepsy among 23,000 genes in the genome (p = 6 × 10−4, binomial probability distribution). Additionally, ADAM22 (MIM 603709) is believed to interact with the protein encoded by LGI1, encoding another Mendelian epilepsy gene.21–23 These observations suggest that rare deletions larger than 1 Mb may influence disease susceptibility, a finding consistent with a recent study of schizophrenia.2

Additional follow-up analyses of these deletion regions, including CGH confirmation (Figure S1), detailed phenotypes of affected patients (Table S1), evaluation of deletion acquisition in a subset of patients (Table S2), and expression changes associated with the deletions (Figure S2), are provided online.

Genome-wide Screen for Locus-Specific CNV Associations

To detect smaller CNVs that associate with epilepsy susceptibility or broad categories of epilepsy subtypes, including partial epilepsy, generalized epilepsy, or temporal lobe epilepsy, we calculated the frequency of deletions (copy number < 2) and duplications (copy number > 2) in 3812 patients with the epilepsy phenotype, and we compared it to the frequency in neurologically normal controls (n = 1299). The frequency was calculated at each unique start and stop site for CNVs that met all of the defined quality control measures (defined in Subjects and Methods). Each site was assessed for a difference in frequency between groups with the use of a permutation-based Fisher's exact test in PLINK.24 Using this approach, we detected no locus-specific associations after correcting for multiple testing (> 32,000 tests).

Evaluation of CNV Burden in Epilepsy Patients

Finally, given recent reports suggesting that CNV burden influences other neuropsychiatric diseases,4,25 we also evaluated patterns of CNVs in epilepsy patients and controls. The results showed no overall differences in CNV burden, average number of genes within or disrupted by CNVs, or enhanced presence of rare gene-disrupting CNVs as defined previously for schizophrenia.4

Discussion

Despite the increasing reports of associations of CNVs with neurological, psychiatric, and developmental disorders, very little is known about the functional mechanisms that result in disease susceptibility. Even more puzzling is the increasing evidence for complex and highly differential phenotypic consequences associated with variants in this class.

Pathogenicity, as well as the pleiotropic consequences of CNVs in neuropsychiatric disease, must be due to haploinsufficiency, chromatin disruption leading to diffuse expression changes in the genome, unmasking of a recessive mutation on the intact stretch of homologous chromosome (previously suggested in 1), modification of germline or somatic mutations, epigenetic or environmental modifiers, or a combination of two or more of the above possible mechanisms.

It is a priority for the field to develop systematic approaches to evaluate these and other possible models of pathogenicity. As a first step toward this, we have developed data addressing a subset of these mechanisms in reference to 16p13.11 deletions, which we now clearly associate with a wide spectrum of epilepsy disorders. Specifically, we find a clear reduction of gene expression for included genes, but no systematic effects for genes near the deleted locus (Figure 3) that might indicate an effect on chromatin structure. In addition, at 16p13.11 we find no obvious deleterious recessive variants on the intact homologous chromosome in ten of the patients carrying the deletion. For the 16p13.11 deletion, at least, it therefore does not appear that unmasking of deleterious recessive mutations is a major component of pathogenicity. Collectively, these data seem to point tentatively toward haploinsufficiency of one or more included genes as a mechanism of pathogenicity. However, we note that the model of haploinsufficiency alone would seem unable to explain the variable presentation of deletions at 16p13.11 and those observed in other regions (1q21.11 and 15q13.33,7,12). Thus, even if haploinsufficiency is the correct model, it still requires other modifiers to influence the precise disease presentation.

In summary, this work suggests that 16p13.11 deletions affect approximately 0.6% of epilepsy patients and that the 16p13.11 deletion is the most prevalent single genetic risk factor for overall seizure susceptibility identified to date. We also identified a number of genic regions that appear to carry epilepsy-associated deletions and warrant detailed evaluation as implemented here for 16p13.11 deletions. Unraveling the interplay of functional and phenotypic consequences of these large deletions will provide novel insights into epilepsy pathophysiology and contribute to an understanding of the complex genetic architecture and phenotypic diversity within epilepsy and, likely, other neuropsychiatric diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients who kindly participated, as well as the physicians who recruited them.

This work was supported by grants from the UK Medical Research Council (G0400126), The Wellcome Trust (084730), the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) (08-08-SCC), University College London Hospitals Clinical Research and Development Committee (F136), and the National Society for Epilepsy, UK. This work was partly undertaken at University College London Hospitals/University College London, which received a proportion of funding from the Department of Health's NIHR Biomedical Research Centres funding scheme. The collection of the Belgian patients was supported by the Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique and the Fondation Erasme, Université Libre de Bruxelles. The collection of the Irish patient cohort was supported as part of the Programme for Human Genomics and the Programme for Research in Third Level Institutions (PRTLI3) funded by the Irish Higher Education Authority and in part by the Children's Medical and Research Foundation and the Irish Research Council for Science, Engineering and Technology. GlaxoSmithKline funded the recruitment and the phenotypic data collection of the GenEpA Consortium samples used in this study and contributed to the genotyping costs associated with their study.

We also acknowledge Leslie Hall, Siwan Oldham, Linda Surh, Rachel Taylor (GlaxoSmithKline), and Dan Lowenstein (University of California, San Francisco) for contributing to the GenEpA steering committee. T.J.U. was supported by the American Epilepsy Society postdoctoral research fellowship.

Contributor Information

Sanjay M. Sisodiya, Email: s.sisodiya@ion.ucl.ac.uk.

David B. Goldstein, Email: d.goldstein@duke.edu.

Supplemental Data

Web Resources

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

Ensembl, http://www.ensembl.org

EPIGEN, http://www.epilepsygenetics.eu

Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Omim/

UCSC Genome Browser, http://genome.ucsc.edu/

References

- 1.Mefford H.C., Sharp A.J., Baker C., Itsara A., Jiang Z., Buysse K., Huang S., Maloney V.K., Crolla J.A., Baralle D. Recurrent rearrangements of chromosome 1q21.1 and variable pediatric phenotypes. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1685–1699. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Need A.C., Ge D., Weale M.E., Maia J., Feng S., Heinzen E.L., Shianna K.V., Yoon W., Kasperaviciūte D., Gennarelli M. A genome-wide investigation of SNPs and CNVs in schizophrenia. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stefansson H., Rujescu D., Cichon S., Pietiläinen O.P., Ingason A., Steinberg S., Fossdal R., Sigurdsson E., Sigmundsson T., Buizer-Voskamp J.E., GROUP Large recurrent microdeletions associated with schizophrenia. Nature. 2008;455:232–236. doi: 10.1038/nature07229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walsh T., McClellan J.M., McCarthy S.E., Addington A.M., Pierce S.B., Cooper G.M., Nord A.S., Kusenda M., Malhotra D., Bhandari A. Rare structural variants disrupt multiple genes in neurodevelopmental pathways in schizophrenia. Science. 2008;320:539–543. doi: 10.1126/science.1155174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiss L.A., Shen Y., Korn J.M., Arking D.E., Miller D.T., Fossdal R., Saemundsen E., Stefansson H., Ferreira M.A., Green T., Autism Consortium Association between microdeletion and microduplication at 16p11.2 and autism. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358:667–675. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa075974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hannes F.D., Sharp A.J., Mefford H.C., de Ravel T., Ruivenkamp C.A., Breuning M.H., Fryns J.P., Devriendt K., Van Buggenhout G., Vogels A. Recurrent reciprocal deletions and duplications of 16p13.11: The deletion is a risk factor for MR/MCA while the duplication may be a rare benign variant. J Med Genet. 2008;46:223–232. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.055202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Helbig I., Mefford H.C., Sharp A.J., Guipponi M., Fichera M., Franke A., Muhle H., de Kovel C., Baker C., von Spiczak S. 15q13.3 microdeletions increase risk of idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Nat Genet. 2009;41:160–162. doi: 10.1038/ng.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Kovel C.G., Trucks H., Helbig I., Mefford H.C., Baker C., Leu C., Kluck C., Muhle H., von Spiczak S., Ostertag P. Recurrent microdeletions at 15q11.2 and 16p13.11 predispose to idiopathic generalized epilepsies. Brain. 2009;133:23–32. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li H., Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li H., Handsaker B., Wysoker A., Fennell T., Ruan J., Homer N., Marth G., Abecasis G., Durbin R., 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dibbens L.M., Mullen S., Helbig I., Mefford H.C., Bayly M.A., Bellows S., Leu C., Trucks H., Obermeier T., Wittig M. Familial and sporadic 15q13.3 microdeletions in idiopathic generalized epilepsy: precedent for disorders with complex inheritance. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:3626–3631. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Bon B.W., Mefford H.C., Menten B., Koolen D.A., Sharp A.J., Nillesen W.M., Innis J.W., de Ravel T.J., Mercer C.L., Fichera M. Further delineation of the 15q13 microdeletion and duplication syndromes: A clinical spectrum varying from non-pathogenic to a severe outcome. J Med Genet. 2009;46:511–523. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.063412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pawlisz A.S., Mutch C., Wynshaw-Boris A., Chenn A., Walsh C.A., Feng Y. Lis1-Nde1-dependent neuronal fate control determines cerebral cortical size and lamination. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008;17:2441–2455. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LaFrance W.C., Jr., Kanner A.M., Hermann B. Psychiatric comorbidities in epilepsy. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2008;83:347–383. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(08)00020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zuberi S.M., Eunson L.H., Spauschus A., De Silva R., Tolmie J., Wood N.W., McWilliam R.C., Stephenson J.B., Stephenson J.P., Kullmann D.M., Hanna M.G. A novel mutation in the human voltage-gated potassium channel gene (Kv1.1) associates with episodic ataxia type 1 and sometimes with partial epilepsy. Brain. 1999;122:817–825. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.5.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cossette P., Liu L., Brisebois K., Dong H., Lortie A., Vanasse M., Saint-Hilaire J.M., Carmant L., Verner A., Lu W.Y. Mutation of GABRA1 in an autosomal dominant form of juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Nat. Genet. 2002;31:184–189. doi: 10.1038/ng885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Audenaert D., Schwartz E., Claeys K.G., Claes L., Deprez L., Suls A., Van Dyck T., Lagae L., Van Broeckhoven C., Macdonald R.L., De Jonghe P. A novel GABRG2 mutation associated with febrile seizures. Neurology. 2006;67:687–690. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000230145.73496.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harkin L.A., Bowser D.N., Dibbens L.M., Singh R., Phillips F., Wallace R.H., Richards M.C., Williams D.A., Mulley J.C., Berkovic S.F. Truncation of the GABA(A)-receptor gamma2 subunit in a family with generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;70:530–536. doi: 10.1086/338710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kananura C., Haug K., Sander T., Runge U., Gu W., Hallmann K., Rebstock J., Heils A., Steinlein O.K. A splice-site mutation in GABRG2 associated with childhood absence epilepsy and febrile convulsions. Arch. Neurol. 2002;59:1137–1141. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.7.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wallace R.H., Marini C., Petrou S., Harkin L.A., Bowser D.N., Panchal R.G., Williams D.A., Sutherland G.R., Mulley J.C., Scheffer I.E., Berkovic S.F. Mutant GABA(A) receptor gamma2-subunit in childhood absence epilepsy and febrile seizures. Nat. Genet. 2001;28:49–52. doi: 10.1038/ng0501-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diani E., Di Bonaventura C., Mecarelli O., Gambardella A., Elia M., Bovo G., Bisulli F., Pinardi F., Binelli S., Egeo G. Autosomal dominant lateral temporal epilepsy: absence of mutations in ADAM22 and Kv1 channel genes encoding LGI1-associated proteins. Epilepsy Res. 2008;80:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalachikov S., Evgrafov O., Ross B., Winawer M., Barker-Cummings C., Martinelli Boneschi F., Choi C., Morozov P., Das K., Teplitskaya E. Mutations in LGI1 cause autosomal-dominant partial epilepsy with auditory features. Nat. Genet. 2002;30:335–341. doi: 10.1038/ng832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morante-Redolat J.M., Gorostidi-Pagola A., Piquer-Sirerol S., Sáenz A., Poza J.J., Galán J., Gesk S., Sarafidou T., Mautner V.F., Binelli S. Mutations in the LGI1/Epitempin gene on 10q24 cause autosomal dominant lateral temporal epilepsy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002;11:1119–1128. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.9.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Purcell S., Neale B., Todd-Brown K., Thomas L., Ferreira M.A., Bender D., Maller J., Sklar P., de Bakker P.I., Daly M.J., Sham P.C. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu B., Woodroffe A., Rodriguez-Murillo L., Roos J.L., van Rensburg E.J., Abecasis G.R., Gogos J.A., Karayiorgou M. Elucidating the genetic architecture of familial schizophrenia using rare copy number variant and linkage scans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:16746–16751. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908584106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.