Abstract

Low-level-radioactive-waste (low-level-waste) sites, including those at various U.S. Department of Energy sites, frequently contain cellulosic waste in the form of paper towels, cardboard boxes, or wood contaminated with heavy metals and radionuclides such as chromium and uranium. To understand how the soil microbial community is influenced by the presence of cellulosic waste products, multiple soil samples were obtained from a nonradioactive model low-level-waste test pit at the Idaho National Laboratory. Samples were analyzed using 16S rRNA gene clone libraries and 16S rRNA gene microarray (PhyloChip) analyses. Both methods revealed changes in the bacterial community structure with depth. In all samples, the PhyloChip detected significantly more operational taxonomic units, and therefore relative diversity, than the clone libraries. Diversity indices suggest that diversity is lowest in the fill and fill-waste interface (FW) layers and greater in the wood waste and waste-clay interface layers. Principal-coordinate analysis and lineage-specific analysis determined that the Bacteroidetes and Actinobacteria phyla account for most of the significant differences observed between the layers. The decreased diversity in the FW layer and increased members of families containing known cellulose-degrading microorganisms suggest that the FW layer is an enrichment environment for these organisms. These results suggest that the presence of the cellulosic material significantly influences the bacterial community structure in a stratified soil system.

The processing of nuclear materials, operation of nuclear reactors, and research and development activities at government sites, hospitals, universities, and radiochemical and radiopharmaceutical manufacturers have led to the generation of a substantial amount of low-level mixed radioactive and heavy metal wastes that have been disposed of in pits, trenches, and other waste sites (2). Codisposed of with metals and radionuclides were large quantities of cellulose-containing materials such as wood, paper towels, cardboard, cheesecloth, and other materials (53). These wastes result from glove box operations, decontamination, housekeeping, maintenance, and construction activities and can constitute up to 90% of the volume of typical low-level radioactive waste (low-level waste [LLW]) (60). While there are over 20,000 commercial users of radioactive materials (2), the Department of Energy (DOE) complex houses the majority of disposed LLW waste at sites including Savannah River, Hanford, Idaho National Laboratory (INL), and Nevada test sites (3). Prior to 2000, the DOE disposed of approximately 2 million cubic meters of LLW and has projected the disposal of an additional 10.1 million cubic meters by 2070 (3). Within the subsurface disposal area at the INL alone, approximately 330 metric tons of U-238 have been buried with cellulose-containing material (26, 32). While these LLW materials are generally classified as such due to their low radioactivity and metal concentrations, their large quantity suggests that there would be cause for environmental concern if mobilization of these contaminants were to occur.

The mobility of heavy metals and radionuclides in the subsurface may be greatly affected by the decomposition of this cellulosic waste by cellulolytic or fermentative microorganisms. A number of soil microorganisms can degrade one or more lignocellulosic components (i.e., cellulose and hemicellulose) to their respective subunits, which include cellobiose and C5 and C6 sugars (i.e., xylose, mannose, and glucose) (7, 38, 43). The breakdown of cellulose itself may release the associated metals and radionuclides, potentially increasing their mobility. Additionally, fermentative bacteria can then use these cellulose breakdown products as carbon and energy sources, producing a variety of fermentation products, including short-chain organic acids, alcohols, and hydrogen (20). These fermentation products may significantly influence contaminant mobility, since organic acids can chelate metals and radionuclides, potentially increasing their mobility (8, 21, 27, 44, 47). On the other hand, the work of numerous investigators has shown that these same compounds can serve as the carbon and energy sources for metal- and sulfate-reducing bacteria that reduce and precipitate the metals and radionuclides found at these sites (1, 7, 19, 31, 39, 40, 45, 48, 52, 56, 59).

To better understand interactions among the bacterial community, cellulosic waste, and contaminants at LLW sites, the bacterial community must first be identified. Little is known about the bacterial community structure at LLW sites, as previous studies have focused on culture-dependent techniques, the construction of small clone libraries, and denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (19, 20). Therefore, this study aimed to perform a larger, in-depth molecular analysis of the entire bacterial community at one of these sites. Soil cores from a surrogate waste pit at the INL were collected, and samples from four depths within the pit were analyzed using 16S rRNA gene clone libraries and high-density 16S rRNA gene microarrays (PhyloChip). The overall goal of this study was to determine how the presence of buried cellulosic waste influences the bacterial community structure found at an LLW site.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Site description.

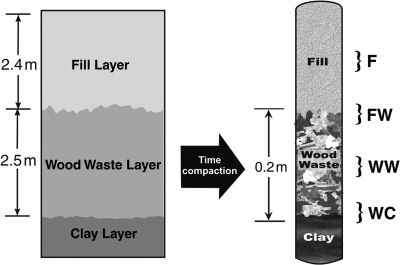

The Cold Test Pit South (CTPS) is located at the DOE INL Radioactive Waste Management Complex (RWMC) about 50 miles west of Idaho Falls, ID. The CTPS was constructed in 1988 and filled with simulated wastes that conform to the historical disposal practices at the RWMC between 1953 and 1970 (58). The pit was constructed to provide a clean environment to test the implementation of innovative waste characterization and retrieval technology and for performance and operational testing of remedial action scenarios. Cardboard was used as simulated waste containers to promote rapid deterioration and simulate up to 35 years of burial in shallow, land-filled pits. The bottom of the CTPS was lined with a crushed-sediment clay liner (Fig. 1). The waste layer, designated the wood waste (WW) layer, contains stacked cardboard boxes, drums of combustibles (scrap wood, cloth, paper, plastic, and HEPA filters), metals (aluminum and steel), concrete, asphalt, glass, and simulated inorganic sludges (silica- and carbonate-based pastes). Evidence from previous activities in the CTPS suggests that most of the simulated waste forms were concentrated at the base of the pit between 2.4 and 4.9 m below grade. The simulated waste layer was then covered with an overlying fill (F) soil layer using local unsaturated soil. Compaction over time reduced the size of the simulated waste layer to approximately 0.2 m.

FIG. 1.

Schematic of the nonradioactive CTPS near the LLW site at the INL where soil samples were obtained. Brackets indicate sampling points. F, fill; FW, fill-waste interface; WW, wood waste; WC, waste-clay interface.

CTPS sampling.

A truck-mounted Powerprobe 9600 (AMS, Inc., American Falls, ID) direct-push sampling rig was used to obtain intact core samples from the CTPS. Soil cores spanning the depth of the pit were collected in sterile 3.2-cm-diameter Lexan core tubes (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Samples were placed in a cooler on ice for shipment to the INL, where the samples were processed.

Lexan tubes were cut at four designated depths representing various layers of the pit (Fig. 1). The four soil layers that were sampled were the overlying F soil layer, the F soil-WW interface (FW), the WW soil layer, and the wood waste-clay interface (WC). Approximately 2.5 cm of soil was removed aseptically using a sterile spatula, and then a sterile 50-ml conical centrifuge tube was used to subcore for samples from which DNA was extracted. For samples that were obtained at interfaces (FW and WC), the soil sample obtained spanned each of the upper and lower layers equally. Samples were stored at −20°C prior to DNA extraction. Triplicate soil samples were collected from each of the four soil layers for individual DNA extraction and molecular analysis.

DNA extraction and 16S rRNA gene amplification.

DNA was extracted using the PowerMax Soil DNA isolation kit (Mo Bio Laboratories, Inc., Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol for the first set of soil samples from each layer (5 g soil per sample). DNA was extracted using the UltraClean Soil DNA kit (Mo Bio Laboratories, Inc., Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol for the second and third soil samples (0.3 g per sample) from each soil layer. Since the WW layer soil was high in humic content, an additional cleanup step using a Sephadex-based spin column was used according to the instructions provided (illustra MicroSpin G-25 columns; GE Healthcare UK) to remove compounds that inhibit amplification.

PCR amplification of 16S rRNA genes was performed using 50-μl reaction mixtures containing a final concentration of 1× PCR buffer, 0.01 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, 0.5 U JumpStart REDTaq DNA polymerase, (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 0.4 μM 8F primer (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′), and 0.4 μM 1492R primer (5′-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′) (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA). The reaction mixtures were heated to 94°C for 10 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 52°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min, with a final extension at 72°C for 10 min (Applied Biosystems GeneAmp PCR System 9700). The amplicons were checked for correct size on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer with an Agilent DNA 7500 kit (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany).

Cloning and sequencing.

Triplicate clone libraries were created for each soil layer using the three individual soil samples, and DNA extracts were obtained. 16S rRNA gene amplicons were ligated into the pCR2.1 vector using the TOPO TA cloning kit and transformed into Top10 competent Escherichia coli cells in accordance with the instructions provided (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Transformants were plated onto Sigma S-gal/LB agar, and individual colonies containing vectors with inserts were chosen based on black-white selection and used to inoculate 1 ml 2× LB with kanamycin in deep-well plates. The plates were incubated for 16 to 18 h at 37°C. The plasmid DNA was purified in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol (Montage Plasmid MiniprepHTS kit; Millipore). The average concentration of the plasmid DNA was 100 to 300 ng/μl, as determined using a NanoDrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE).

The purified plasmid DNA from one clone library of each of the four soil layers was sent to Idaho State University (ISU) Molecular Research Core Facility (MRCF) for sequencing. The purified plasmid DNA from the other two clone libraries of each of the four soil layers was sequenced at INL. At both locations, Sanger cycle sequencing reaction mixtures with dye terminators were prepared using between 100 and 200 ng template DNA, 1 μl BigDye v3.1 (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA), and one of three primers, M13F (5′-GTAAAACGACGGCCAG-3′), 515F (5′-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3′), or M13R (5′-CAGGAAACAGCTATGAC-3′), in a reaction mixture volume of 10 μl (primer concentrations were 3.2 pmol/μl at ISU and 5 pmol/μl at the INL). Reaction mixtures were denatured at 96°C for 1 min, followed by 40 cycles of 96°C for 10 s, 50°C for 5 s, and 60°C for 4 min. At the ISU MRCF, excess reagents and dye were removed using Millipore-seq plates (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and DNA was analyzed on an Applied Biosystems 3130 Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). At the INL, excess reagents and dye were removed using Performa DTRPlates (Edge Bio, Gaithersburg, MD) and DNA was analyzed on a 3730 DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA).

Sequence analysis.

Individual clones were sequenced using forward, internal, and reverse primers M13F, 515F, and M13R, respectively. Vector sequences were removed before assembly. Contiguous sequences were assembled using Phrap (16, 17) to make full-length 16S rRNA gene sequences. Clones were trimmed to remove poor-quality regions using Phred (22) (Q < 20), NAST aligned (10), and checked for chimeras with Bellerophon (25), all through the use of tools provided by Greengenes (12) (http://greengenes.lbl.gov/cgi-bin/nph-index.cgi). Nonchimeric sequences were compared to public databases in Greengenes and classified using the G2_Chip taxonomy classification system.

16S rRNA gene microarray analysis.

Amplification of the 16S rRNA gene from one of the DNA extractions obtained from each of the four soil layers was performed using 2 μg per reaction. Hybridization and subsequent analysis on a 16S rRNA gene-based microarray (PhyloChip) were carried out as previously described (11). Duplicate microarrays were analyzed for each soil layer sampled. A probe pair was scored as positive if (i) the fluorescence intensity of the perfect match probe was at least 1.3 times greater than the intensity of the mismatch probe and (ii) the difference between the perfect match and mismatch intensities was 130 times greater than the square of the background intensity. An operational taxonomic unit (OTU) was identified as present if at least 92% of the probe pairs for a specific OTU were scored as positive (probe fraction [pf] value ≥ 0.92). An OTU was scored as positive for a soil layer if the OTU met these criteria for both replicate microarrays of each layer. ARB (42) version 08.07.08prv and the SILVA 04.10.08 reference database were used for the production of neighbor-joining phylogenetic trees and MeV (49) for the production of heat maps.

Statistical analyses.

Statistically significant differences between duplicate PhyloChips and triplicate clone libraries for each layer were evaluated by Unifrac (41). Unweighted principal-coordinate analysis (PCoA) and lineage-specific analysis were performed using Unifrac software for both the clone library and PhyloChip NAST-aligned sequences. Before PCoA analysis, clone libraries were analyzed using DOTUR (54) (www.plantpath.wisc.edu/fac/joh/dotur.html), in which a 97% cutoff was used to group sequences into OTUs. A single representative sequence from each OTU was included in the analysis to eliminate phylogenetic weighting. Shannon's and Simpson's diversity indices, as well as rarefaction curves (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material) for both the clone library and PhyloChip data sets, were also calculated using DOTUR.

Quantitative PCR.

Specific primers for the Acidimicrobiaceae, Flexibacteriaceae, Streptomycetaceae, and KSA unclassified families were designed using the PROBE DESIGN and MATCH PROBE functions in ARB (42) version 08.07.08prv. Primers were designed and tested using an ARB neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree with all sequences detected by both PhyloChip and clone library analyses. Each family-specific primer was paired with a general bacterial primer (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). All primer pairs were determined to be highly specific to the target family (data not shown). Triplicate DNA extracts of each soil layer were diluted to the concentration used for amplification in the clone library analysis. Equal volumes of each of the diluted DNA extracts were pooled for each soil layer. A two-step amplification using 5 ng of template DNA from each soil layer was carried out using a Rotor-Gene SYBR green PCR kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA). An initial activation step of 95°C for 5 min, 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 5 s, and a combined annealing-extension step at 60°C for 10 s were performed when using the Acidimicrobiaceae-, Flexibacteriaceae-, and KSA unclassified-specific primers. Analysis with the Streptomycetaceae-specific primers had an increased combined annealing-extension temperature of 65°C. Triplicate samples were analyzed for each soil layer using each set of family-specific primers. Results are reported as the 16S rRNA gene copy number per nanogram of total DNA extracted.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

All nucleotide sequences from clone library analyses were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers GQ262819 to GQ264537.

RESULTS

Clone library and PhyloChip analyses.

A total of 448, 431, 382, and 458 clones were obtained from the F, FW, WW, and WC layers, respectively, after sequences were trimmed, aligned, and screened for chimeras. The complete clone library of the simulated LLW site contained 1,719 clones. Analysis of sequences followed the “standard operating procedure for phylogenetic inference” (46) regarding sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree building where applicable. The triplicate clone library results for each layer were evaluated using Unifrac and were determined not to be significantly different (P ≥ 0.2). Therefore, the triplicate libraries for each layer were combined and considered one complete library for this study.

Duplicate PhyloChip analyses performed for each layer were also evaluated using Unifrac, determined not to be significantly different (P ≥ 0.2), combined, and also reported as one data set for each layer. Totals of 717, 1,356, 1,567, and 1,582 unique OTUs were scored as positive in the F, FW, WW, and WC layers, respectively.

Bacterial community structure.

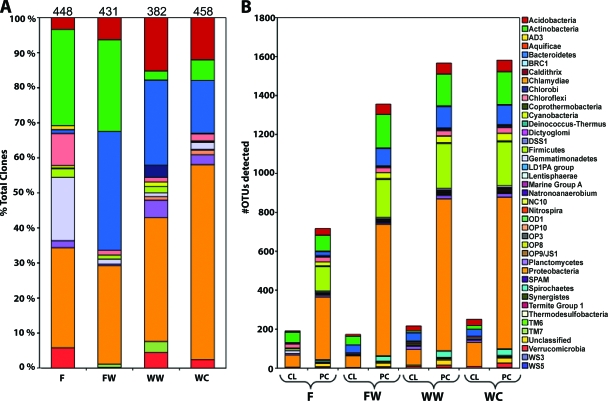

Both the clone library and PhyloChip results indicated that the bacterial community profile changed with depth when viewed at the phylum level. Clone library analysis revealed that Proteobacteria were dominant in all four layers, accounting for 29, 28, 35, and 56% of the total clones in the F, FW, WW, and WC layers, respectively (Fig. 2A). Twelve phyla were detected in the F layer by clone library analysis, with the Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Gemmatimonadetes phyla making up the majority of the total clones detected. These three phyla represented 332, or 74%, of the 448 F layer clones. The FW layer contained clones from 10 different phyla, the least of any of the layers. The FW layer was composed mostly of clones within the phyla Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Bacteroidetes. The Actinobacteria and Bacteroidetes phyla combined represented 60% of the total FW layer clones. This was a significant increase in Bacteroidetes clones from the F layer, as they were 34% of the total FW layer clones and only 1% of the total F layer clones. The WW layer contained clones from 13 different phyla, the most of any layer, and the WC layers contained clones from 12 different phyla. Additionally, both layers were composed mainly of Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Acidobacteria. These three phyla represented 74% of the total clones in the WW layer and 83% of the total clones in the WC layer.

FIG. 2.

The bacterial community viewed at the phylum level with depth at the CTPS. (A) Percent abundance of each phylum as determined by clone library analysis with the total number of clones for that layer listed at the top of each bar. (B) Number of unique OTUs identified within each phylum based on clone library (CL) and PhyloChip (PC) analyses. F, fill; FW, fill-waste interface; WW, wood waste; WC, waste-clay interface.

The PhyloChip data also indicated a change in community profile with depth and showed greater numbers of unique OTUs with increasing depth (Fig. 2B). Though the number of unique OTUs changed with depth, four phyla were consistently dominant, and in similar ratios to each other, in all soil layers. The Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, and Bacteroidetes phyla accounted for approximately 77, 84, 82, and 81% of the total OTUs detected by PhyloChip analysis in the F, FW, WW, and WC layers, respectively. In each layer, the Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, and Bacteroidetes phyla made up approximately 50%, 15%, 11%, and 6%, respectively, of the total OTUs detected by the PhyloChip in each soil layer.

A comparison at the OTU level between methods indicates that the PhyloChip detected significantly more OTUs than the clone libraries in all soil layers. Clone library analyses detected 191, 173, 217, and 252 unique OTUs in the F, FW, WW, and WC layers, respectively, compared to the PhyloChip analyses, which, as previously mentioned, detected 717, 1,356, 1,567, and 1,582 unique OTUs in the same layers. A total of 2,002 unique OTUs were detected in the entire study. Of these, only 10% were detected by both the clone library and PhyloChip methods (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Another 10% were detected by the clone library analysis only, while the remaining 80% were detected by the PhyloChip analysis only.

Bacterial community diversity.

Shannon's and Simpson's indices both indicated greater diversity in all four soil layers by PhyloChip analysis than by clone library analysis (Table 1). The Simpson's indices calculated for both methods demonstrated a similar trend, in which overall the F and FW layers had the least diversity while the WW and WC layers had the greatest diversity.

TABLE 1.

Shannon's and Simpson's indices calculated using clone library and PhyloChip data for each soil layera

| Layer | Shannon's index (95% CI) |

Simpson's index |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CL | PC | CL | PC | |

| F | 5.56 (±0.090) | 6.21 (±0.062) | 3.40E−03 | 6.00E−05 |

| FW | 5.61 (±0.093) | 5.86 (±0.074) | 3.10E−03 | 6.20E−05 |

| WW | 5.67 (±0.071) | 7.10 (±0.040) | 1.70E−03 | 3.70E−05 |

| WC | 5.72 (±0.084) | 7.03 (±0.041) | 2.20E−03 | 3.40E−05 |

CL, clone library; PC, PhyloChip; CI, confidence interval; F, fill; FW, fill-waste interface; WW, wood waste; WC, waste-clay interface.

Shannon's indices calculated using the clone library data indicated that there was no significant difference in diversity between soil layers. Conversely, Shannon's indices calculated with the PhyloChip data suggested there were significant differences in diversity between layers. Shannon's indices based on PhyloChip data determined that the FW layer had the least diversity, followed by the F layer, while the WW and WC layers had the greatest diversity.

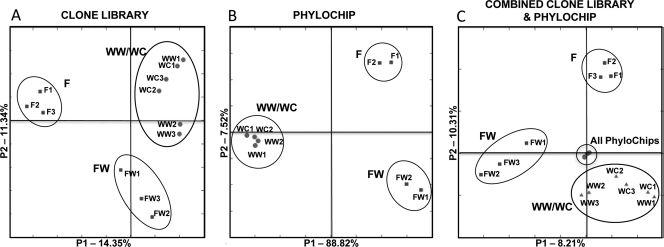

Soil layer stratification.

PCoA was performed with both the clone library and PhyloChip community data sets, and the results suggest that there were significant differences between the bacterial communities with depth (Fig. 3). The clone library data (Fig. 3A) and PhyloChip data (Fig. 3B) were first analyzed separately and yielded similar results. Triplicate clone libraries and duplicate PhyloChips for each soil layer clustered with themselves, again confirming the similarities between the replicates. When soil layers were compared, the WW and WC layers grouped closely together while the F and FW layers clustered independently from the other layers. Not surprisingly, when the clone library and PhyloChip data sets were combined and analyzed, the method used to identify the community appeared to influence the clustering of the data more heavily than the soil layer, since the PhyloChip data sets clustered together and independently of any of the clone library data (Fig. 3C). The clone library data still demonstrated the same trend shown in Fig. 3A: the F and FW layers each clustered by themselves, while the WW and WC layers clustered together.

FIG. 3.

PCoA of the (A) combined clone libraries, (B) combined PhyloChip data, and (C) combined clone library and PhyloChip data. A 97% identity cutoff was used to remove replicate sequences from the clone libraries before analysis. F, fill; FW, fill-waste interface; WW, wood waste; WC, waste-clay interface.

Lineage-specific analysis of the clone libraries was performed with Unifrac to determine which phyla were responsible for the differences between layers observed in the PCoA analysis. Multiple branch nodes were evaluated, and it was determined that groups within the Actinobacteria and Bacteroidetes phyla were responsible for the majority of the significant differences between layers (P < 0.05). Unifrac could not support lineage-specific analysis with the PhyloChip data, due to the large number of sequences. Because the Actinobacteria and Bacteroidetes phyla are known to contain cellulose-degrading microorganisms (43) and were identified as groups accounting for much of the change in bacterial community structure with depth, they were evaluated further to identify how they changed with depth. While the Proteobacteria also accounted for some of the changes identified by lineage-specific analysis, the majority of these Proteobacteria clones were identified and categorized by Unifrac as only “suggestive” (P value, 0.05 to 0.1) and thus less statistically significant.

Actinobacteria and Bacteroidetes phyla.

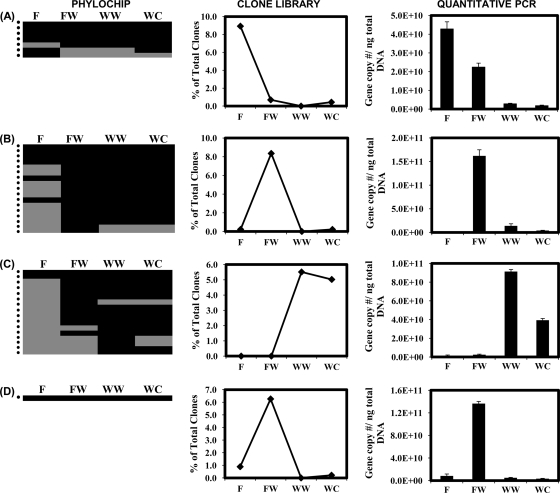

There were 123, 113, 10, and 27 clones identified as belonging to the phylum Actinobacteria in the F, FW, WW, and WC layers, respectively, corresponding to 28, 26, 3, and 6% of the total clones detected in each layer. Results indicate a difference in the Actinobacteria community structure with depth when viewed at the family level. In particular, four families showed significant changes with depth based on clone abundance: Acidimicrobiaceae, Glycomycetaceae, Micromonosporaceae, and Streptomycetaceae (Fig. 4; see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Of these four families, two were chosen for additional quantitative analysis using 16S rRNA gene family-specific primers.

FIG. 4.

(A) Acidimicrobiaceae and (B) Streptomycetaceae families within the Actinobacteria phylum and (C) Flexibacteraceae and (D) KSA unclassified families within the Bacteroidetes phylum that had significant changes with depth as viewed by PhyloChip and clone library analyses. PhyloChip results are presented as a presence (black)-absence (gray) heat map for each OTU detected within the family. Each row marked by a dot on the left represents a unique OTU. An OTU was determined to be present in a soil layer if the pf value was above or equal to 0.92 for both PhyloChips. Clone abundance of each family is reported as the percentage of the total clones detected per soil layer. Quantitative PCR was performed using family-specific primers for amplification of the 16S rRNA gene. F, fill; FW, fill-waste interface; WW, wood waste; WC, waste-clay interface.

Lineage-specific analysis identified Acidimicrobiaceae as responsible for some of the differences seen between the F layer and the other three layers. The Acidimicrobiaceae family contributed 33% of the total Actinobacteria clones and 8.9% of the total clones detected in the F layer. An approximately 10-fold decrease in the percentage of Acidimicrobiaceae clones was observed between the F and FW layers (Fig. 4A). No Acidimicrobiaceae clones were detected in the WW layer, and only three were detected in the WC layer, accounting for less than 1% of the total clones detected. The PhyloChip, however, detected the presence of Acidimicrobiaceae OTUs in all four soil layers, suggesting they are present throughout. The quantitative PCR data confirm the trends observed based on clone library analysis and also support the PhyloChip results, as it detected the presence of Acidimicrobiaceae in the WW layer, where no clones were identified. The Streptomycetaceae family had an approximately 40-fold increase in clone abundance between the F and FW layers (Fig. 4B). This increase was followed by significant decreases between the FW and WW layers. The quantitative PCR analysis also identified a significant increase between the F and FW layers in which approximately a 100-fold increase in the Streptomycetaceae 16S rRNA gene copy number per nanogram of total DNA was observed. This was followed by a significant decrease between the FW and WW layers. However, between the WW and WC layers, a decrease in the Streptomycetaceae 16S rRNA gene copy number per nanogram of total DNA was observed, while the clone libraries contained no clones in the WW layer and only one clone in the WC layer. The PhyloChip detected a large increase in the number of unique OTUs between the F layer and all of the other layers.

In the Bacteroidetes phylum, 5, 146, 93, and 69 clones were detected in the F, FW, WW, and WC layers, respectively, contributing approximately 1, 34, 24, and 15% of the total clones detected in these layers. This significant increase in the number of Bacteroidetes clones between the F layer and the other three layers partially explains how this phylum contributes to the observed stratification between layers. Four families in particular showed significant changes in clone abundance with depth and were identified by lineage-specific analysis as contributing to the stratification between layers: Crenotrichaceae, Flexibacteriaceae, Sphingobacteriaceae, and KSA unclassified clones (Fig. 4; see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Of these four families, two were chosen for additional quantitative analysis using 16S rRNA gene family-specific primers.

No Flexibacteriaceae clones were detected in the F or FW layer, though the PhyloChip and quantitative PCR detected their presence in both layers. Flexibacteriaceae clones accounted for 5.5% and 5.0% of the total WW and WC layer clones, respectively (Fig. 4C). Quantitative PCR analysis detected a decrease in the Flexibacteriaceae 16S rRNA gene copy number per nanogram of total DNA between the WW and WC layers but a greater decrease than was observed by clone library analysis. The PhyloChip detected a greater number of unique OTUs within the WW and WC layers than in the other two layers.

KSA unclassified clones detected in the F layer, based on clone library analysis, accounted for only 0.9% of the total clones (Fig. 4D). An approximately 7-fold increase in clone abundance was observed between the F and FW layers, followed by a significant decrease in the WW and WC layers. Interestingly, the PhyloChip only detected one unique OTU that was present in all four soil layers. The quantitative data support the trend observed by clone library analysis in which there was an increase in the KSA unclassified 16S rRNA gene copy number per nanogram of total DNA in the FW layer, followed by a significant decrease in the WW and WC layers. It also detected this family in all four soil layers, which supports the PhyloChip results.

Potential for cellulose degradation.

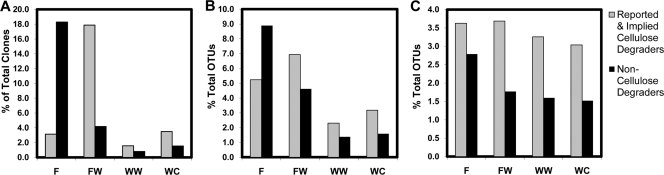

To gain a better understanding of the potential role of the Actinobacteria phylum in response to the presence of cellulose, families were evaluated based on whether or not they had at least one significant change between two soil layers. A significant change was defined as at least a 4-fold increase or decrease in clone numbers, which coincides with an approximately 1% change in total clone abundance, between any two layers. Thirteen families out of 33 detected met this criterion: Acidimicrobiaceae, Microthrixineae, Frankiaceae, Glycomycetaceae, Kineosporaceae, Microbacteriaceae, Micromonosporaceae, Streptomycetaceae, Thermomonosporaceae, Rubrobacteraceae, and three unclassified families. These families were then differentiated based on their potential capabilities to degrade cellulose. Those that had been reported in the literature to be known cellulose degraders or cellobiose utilizers or suggested to be cellulose degraders were grouped together as reported and implied cellulose degraders (4, 5, 9, 15, 30, 35-37, 43, 50, 61). Those families that have never been shown to degrade cellulose or utilize cellobiose nor suggested to be able to do so were grouped together as non-cellulose degraders. These groups were then compared in terms of their abundance and relative diversity with depth.

The clone abundance of the non-cellulose-degrading group was highest in the F layer, accounting for 18.3% of the total clones detected in this layer, and decreased approximately 5-fold between the F and FW layers (Fig. 5A). There were only three clones from this group in the WW layer and seven clones in the WC layer, accounting for less than 2% of the total clones in both layers. Conversely, the number of clones of the reported and implied cellulose-degrading group was highest in the FW layer, increasing 6-fold in abundance between the F and FW layers. This group accounted for 17.9% of the total clones detected in the FW layer, decreasing in abundance in the deeper layers and accounting for 1.6% of the total clones in the WW layer and 3.5% of the total clones in the WC layer. The greatest relative diversity, identified by clone library analysis, also correlated with the soil layer in which the greatest clone abundance was detected (Fig. 5B). This was the F layer for the non-cellulose-degrading group and the FW layer for the reported and implied cellulose-degrading group. The PhyloChip also detected the greatest number of unique OTUs in the F layer for the non-cellulose-degrading group and in the FW layer for the reported and implied cellulose-degrading group (Fig. 5C). However, the change in the number of unique OTUs detected by PhyloChip analysis and relative abundance among all four layers was not as great as indicated by the clone libraries, suggesting that clone libraries may be more sensitive than the PhyloChip to significant changes in populations. Interestingly, the PhyloChip detected a greater number of unique OTUs within the reported and implied cellulose-degrading group than in the non-cellulose-degrading group in all four layers. This may be due to an underestimate of the reported and implied cellulose-degrading group's presence and diversity by the clone libraries or may be due to a larger number of probes for this group found on the PhyloChip, therefore increasing its chance of detection.

FIG. 5.

Focus group comparisons of the Actinobacteria phylum. Families with a significant decrease or increase in the clone number between at least two layers (e.g., significant change between the F and FW layers) were categorized as either reported and implied cellulose degraders (families that were previously known to be cellulose degraders or cellobiose utilizers or have been suggested to be potential cellulose degraders) or non-cellulose degraders (families that have not been shown in the literature to degrade cellulose or utilize cellobiose nor suggested to be able to). These two groups were then compared based on (A) clone abundance and the number of OTUs detected by (B) clone library and (C) PhyloChip analyses. F, fill; FW, fill-waste interface; WW, wood waste; WC, waste-clay interface.

Unlike the Actinobacteria, all of the families that showed significant differences between layers contain known cellulose degraders (23, 24, 29, 33, 34, 43), except for the KSA unclassified family, of which no metabolic capabilities could be found in the literature. Regardless, the large number of reported and implied cellulose-degrading Bacteroidetes families detected by clone abundance and PhyloChip analysis in the FW, WW, and WC layers suggests that there is potential for cellulose degradation in these layers.

DISCUSSION

Clone library and PhyloChip comparison.

Both the clone library and PhyloChip analyses yielded valuable information about the bacterial community structure and diversity at the CTPS. While 1,719 clones is a substantial clone library data set, the results of the PhyloChip analyses demonstrate that even with a large number of clones, the results barely depict the total diversity that was found at the CTPS, as almost 80% of the total OTUs observed were detected by the PhyloChip only. The PhyloChip's sensitivity to low-abundance OTUs is useful in identifying rare members of the community that may play a key role in the environment but are not present in high numbers. Still, the clone libraries detected 203 OTUs that the PhyloChip did not detect and also provide insight into the potential abundance and dominance of these organisms at the CTPS, making it a valuable method to use as well.

Similar to previous studies in which both PhyloChips and clone libraries were used, the PhyloChip detected a greater overall diversity and number of unique OTUs (6, 11, 18, 51, 57). As previously mentioned, there were OTUs and even entire families detected through clone library analysis that were not detected by the PhyloChip. This may be due to poor hybridization with the probe, a sequence having a stronger affinity to the mismatch probe, or the absence of these sequences in the database when the probes were designed. It is also important to point out that when comparing the presence or absence of a specific OTU among the four soil layers, there was a low percentage of matches between the two methods. While it was not surprising that a unique OTU was detected only by the PhyloChip in a soil layer, it was surprising to observe the number of unique OTUs detected in some layers by the clone libraries only and in other layers by the PhyloChip only. This further supports the value of using these two methods to complement each other to gain more information about the bacterial community and may be especially important in studies where one specific OTU or organism is focused on.

In addition to the molecular analyses discussed in this study, six bacterial isolates (members of the genera Pseudomonas, Pedobacter, Streptomyces, Flavobacterium, Serratia, and Cellulomonas) were obtained from cellulose-degrading enrichments inoculated with the soil from the FW, WW, and WC layers (see the supplemental material). The results of these cultivation studies can be compared to both the clone library and PhyloChip results to further demonstrate the differences between these two methods. All six isolates were detected at the family level by PhyloChip analysis in all three soil layers (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). As the PhyloChip detects a great amount of diversity and a large number of community members, it is not surprising that it would detect all six families in all of the soil layers. Meanwhile, clone library analyses detected some of these families, such as Enterobacteriaceae containing the Serratia sp. isolate and Sphingobacteriaceae containing the Pedobacter sp. isolate, in layers from which they were not isolated. This suggests that either these organisms were present and we were unable to culture them or a different member of the family was present. While it is not surprising that there are soil layers in which these organisms are present but we were unable to culture them, it is interesting that a few of the isolates were cultivated from soil layers in which clone library analyses did not detect the presence of their families. For example, in the WW layer, the clone libraries did not detect any members of the family Streptomycetaceae. However, a Streptomyces sp. was isolated from the WW soil layer and the PhyloChip confirms the family's presence. If only clone library analysis had been conducted, the results would suggest that there were no members of this family present in this layer. These results further demonstrate the limits of clone library analysis and its potential to miss much of the diversity present at the site.

The results of this study show that the PhyloChip detects greater diversity, which provides a more complete picture of the community structure and is important in identifying rare members of the community that may play an important functional role at the site. However, it is limited by the fact that in its current state it is not a quantitative method. Therefore, it cannot be used to determine which members of the community are more abundant and will not detect changes in abundance between soil layers. Also, the PhyloChip does not appear to be as sensitive to small changes within the community, as seen with the Actinobacteria and Bacteroidetes phyla.

The clone libraries are semiquantitative and begin to address which members of the community are abundant. Quantitative analysis performed for selected families within the Actinobacteria and Bacteroidetes phyla support the data obtained by clone library analysis, suggesting that such a large clone library data set provides better confidence in the quantitative aspect of the clone library results. Still, as some differences between the results of the quantitative PCR and clone library analyses were seen, there are biases in the construction and analysis of clone libraries that limit its ability to be truly quantitative. On the other hand, they are more sensitive to changes within the community structure than the PhyloChip, which is an additional advantage to using clone library analyses.

LLW site microbial communities.

A total of 2,002 unique OTUs were detected by both methods combined in all four soil layers, and the dominant phyla observed (Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Acidobacteria, and Firmicutes) were similar to those in other soil studies (14, 28, 55). Additionally, at least one of the methods used in this study detected the class and, in most cases, the family containing multiple genera identified in previous studies (including Bacillus, Pseudomonas, Citrobacter, Clostridium, Azospira, Quadricoccus, Brevundimonas, and Trichococcus) focusing on LLW sites where culture techniques and small clone libraries were used to characterize the bacterial community, thus confirming their results (19, 20). The molecular techniques used in this study identified significantly more members of the bacterial community than previous studies. For example, Fox et al. in 2006 (19) identified eight distinct RFLP sequences from 29 clones in their LLW microbial community batch studies and even in the enrichments established in parallel to this study, only six isolates were cultured while 2,002 unique OTUs were identified. While it is known that culture-based techniques only focus on a small fraction of the microbial community, the findings of this study put into perspective how small a fraction that may be.

Influence of cellulose on the bacterial community.

Significant changes in the community structure and dominant phyla were observed with depth at the CTPS by both clone library and PhyloChip analyses, suggesting that the presence of cellulosic waste significantly influences the bacterial community at this site. PCoA analysis also supports this hypothesis, as it showed a stratification of the bacterial community occurring within the CTPS between the F, FW, and WW layers. The similarities observed between the WW and WC layer bacterial communities suggest that this part of the CTPS is not as stratified as in the shallower depths. This may be due to the presence of the clay lining at the bottom that allows the retention of water at this depth, decreasing stratification between the two soil layers.

The F layer had a low diversity overall, suggesting a more oligotrophic soil environment, most likely containing few carbon and energy sources supplied through downward transport during precipitation and snowmelt events. Additionally, the decrease in the number of phyla detected and the low calculated diversity at the FW layer suggest that there may be a selective influence on the community at this depth, where those bacteria with a certain metabolic advantage are dominant. The abundance of the phyla Actinobacteria and Bacteroidetes in this layer, as well as specific families within these phyla that contain known or potential cellulose degraders, suggests that cellulose may be the selective influence at this depth and cellulose-degrading microorganisms may have a metabolic advantage.

The WW layer of the CTPS contains large quantities of cellulosic materials. Therefore, it was hypothesized that this layer would most likely support growth of cellulose degraders. In this layer, both the clone library and PhyloChip results indicate the presence of families containing known cellulose degraders, suggesting that cellulose degradation may be occurring at this depth. However, increased diversity was also observed in this layer, suggesting that cellulose is likely broken down and utilized by either cellulose-degrading organisms themselves or other bacteria that rely on these breakdown products for growth. These products, readily utilized by a wide variety of microorganisms, would support a greater diversity of microorganisms in this layer. Compared to the WW and WC layers, the decreased diversity observed in the FW layer may be due to selective pressures on microorganisms in this layer, such as a lack of trace nutrients which may have been buried with the simulated waste, and a lack of retained water or retained breakdown products, which lead to the observed decrease in diversity in the FW layer. It is also important to note that while fungi were not considered in this study, we recognize that they may be catalyzing cellulose degradation at this site and therefore may be influencing the activity and diversity of the bacterial community between the different soil layers.

While the presence of these microorganisms cannot be linked to metabolic function directly and there may be other environmental variables besides cellulose influencing the bacterial community structure, the results demonstrate the possibility of cellulose playing a role in the changes in community structure with depth.

We hypothesized that the Firmicutes would be dominant at this site since this phylum contains many known cellulose degraders (13, 43), which are often dominant in soil environments (28) and are spore formers, which is likely advantageous when fluxes of water and nutrients into the system are minimal. The PhyloChip detected a large number of Firmicutes OTUs in all four layers, demonstrating a large relative diversity of this phylum present; however, the clone libraries detected a total of only 24 Firmicutes clones in all four soil layers and overall the number decreased with depth. It is possible that either members of this phylum are not very abundant at this site or the extraction and cloning method was not optimal for these organisms.

While all four layers were dominated by Proteobacteria, this was not surprising since Proteobacteria is a large, well-studied phylum containing many known members. Some members of the Proteobacteria such as Pseudomonas spp. can carry out aerobic cellulose degradation (43) and while they may play a role in cellulose degradation at this site, as they were detected by both methods, they did not change significantly with depth. Members of this phylum, as well as other phyla that did not change significantly with depth, may play important roles in other processes occurring in the soil such as metal cycling or the cycling of other nutrients. This may have significance in future studies which will focus on the interactions between the bacterial community and heavy metals and radionuclides found at this site.

Significance and future studies.

The results of this study provide insight into how the presence of cellulosic waste influences a bacterial community. This is the most in-depth study to date of the bacterial community found at an LLW site. To our knowledge, this is also the most in-depth study to date using both clone libraries and PhyloChip analyses to identify the bacterial community found in any one soil environment due to the large clone library size, numerous PhyloChips analyzed, and evaluation of the site at multiple depths. Multidepth sampling, such as that performed in this study, can identify potentially important changes in the microbial community that may otherwise be overlooked. This will lead to the ability to better define and identify the potential roles different microorganisms have in metal mobility at these LLW sites and better design remediation processes that may be needed at these sites in the future.

The results presented here will provide an extensive baseline for future studies investigating how bacterial community structure and function change as a function of cellulose utilization. Column studies are being used to potentially identify which groups of organisms may be playing a key role in heavy metal and radionuclide mobility in simulated LLW environments. In these studies, the bacterial community at both the DNA and RNA levels will be evaluated and geochemical parameters will be monitored. These analyses will aid in linking the bacterial community structure with the community function. The results presented here are the first step in better understanding the interactions between the bacterial community and cellulosic waste and contaminants at LLW sites.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Yvette Piceno, Todd DeSantis, Gary Andersen, and Eoin Brodie at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory for their indispensable training in running G2 PhyloChips and help in acquiring and analyzing the PhyloChip data. Thanks to the ISU MRCF for sequencing and to those at the INL who provided technical assistance in completing the clone libraries, including Michelle Walton, Frank Roberto, Cody Permann, and John Aston. We also extend our thanks to Steve Lopez for sampling access to the CTPS, as well as to Bill Smith and Joe Lord for operation of the PowerProbe sampling unit. Additional thanks to Peg Dirckx and Chantel Naylor for their graphical support.

The Montana State University portion of this work was supported by the U.S. DOE, Office of Science, Environmental Remediation Science Program (ERSP), contract DE-FG02-06ER64206. The INL portion of the work was supported by the U.S. DOE, Assistant Secretary for the Office of Science, ERSP, under DOE-NE Idaho Operations Office contract DE-AC07-05ID14517.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 10 March 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdelouas, A., W. Lutze, W. L. Gong, E. H. Nuttall, B. A. Strietelmeier, and B. J. Travis. 2000. Biological reduction of uranium in groundwater and subsurface soil. Sci. Total Environ. 250:21-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anonymous. 1994. Radioactive waste disposal: an environmental perspective. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC.

- 3.Anonymous. 2000. The current and planned low-level waste disposal capacity report, revision 2. Department of Energy, Washington, DC.

- 4.Bayer, E., Y. Shoham, and R. Lamed. 2006. Cellulose-decomposing bacteria and their enzyme systems, p. 578-617. In M. Dworkin, S. Falkow, E. Rosenberg, K. Schleifer, and E. Stackebrandt (ed.), The prokaryotes, 3rd ed., vol. 2. Springer Science & Business Media, LLC, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bentley, S., C. Corton, S. Brown, A. Barron, L. Clark, J. Doggett, B. Harris, D. Ormond, M. Quail, and G. May. 2008. Genome of the actinomycete plant pathogen Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. sepedonicus suggests recent niche adaptation. J. Bacteriol. 190:2150-2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brodie, E., T. Desantis, D. Joyner, S. Baek, J. Larsen, G. Andersen, T. Hazen, P. Richardson, D. Herman, T. Tokunaga, J. Wan, and M. Firestone. 2006. Application of a high-density oligonucleotide microarray approach to study bacterial population dynamics during uranium reduction and reoxidation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:6288-6298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chew, I., J. Obbard, and R. Stanforth. 2001. Microbial cellulose decomposition in soils from a rifle range contaminated with heavy metals. Environ. Pollut. 111:367-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choy, C., G. Korfiatis, and X. Meng. 2006. Removal of depleted uranium from contaminated soils. J. Hazard. Mater. 136:53-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coughlan, M., and F. Mayer. 1992. The cellulose-decomposing bacteria and their enzyme systems, p. 460-516. In A. Balows, H. G. Truper, M. Dworkin, W. Harder, and K. Schleifer (ed.), The prokaryotes, 2nd ed., vol 1. Springer Verlag, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeSantis, T., Jr., P. Hugenholtz, K. Keller, E. Brodie, N. Larsen, Y. Piceno, R. Phan, and G. Andersen. 2006. NAST: a multiple sequence alignment server for comparative analysis of 16S rRNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:394-399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeSantis, T., E. Brodie, J. Moberg, I. Zubieta, Y. Piceno, and G. Andersen. 2007. High-density universal 16S rRNA microarray analysis reveals broader diversity than typical clone library when sampling the environment. Microb. Ecol. 53:371-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeSantis, T., P. Hugenholtz, N. Larsen, M. Rojas, E. Brodie, K. Keller, T. Huber, D. Dalevi, P. Hu, and G. Andersen. 2006. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:5069-5072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Desvaux, M. 2005. Clostridium cellulolyticum: model organism of mesophilic cellulolytic clostridia. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 29:741-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elshahed, M., N. Youssef, A. Spain, C. Sheik, F. Najar, L. Sukharnikov, B. Roe, J. Davis, P. Schloss, V. Bailey, and L. Krumholz. 2008. Novelty and uniqueness patterns of rare members of the soil biosphere. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:5422-5428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evtushenko, L., and M. Takeuchi. 2006. The family Microbacteriaceae, p. 1020-1098. In M. Dworkin, S. Falkow, E. Rosenberg, K. Schleifer, and E. Stackebrandt (ed.), The prokaryotes, 3rd ed., vol. 3. Springer Science & Business Media, LLC, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ewing, B., and P. Green. 1998. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using Phred. II. Error probabilities. Genome Res. 8:186-194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ewing, B., L. Hillier, M. Wendl, and P. Green. 1998. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using Phred. I. Accuracy assessment. Genome Res. 8:175-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flanagan, J., E. Brodie, L. Weng, S. Lynch, O. Garcia, R. Brown, P. Hugenholtz, T. DeSantis, G. Andersen, J. Wiener-Kronish, and J. Bristow. 2007. Loss of bacterial diversity during antibiotic treatment of intubated patients colonized with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:1954-1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fox, J., R. Mortimer, G. Lear, J. Lloyd, I. Beadle, and K. Morris. 2006. The biogeochemical behaviour of U (VI) in the simulated near-field of a low-level radioactive waste repository. Appl. Geochem. 21:1539-1550. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Francis, A., S. Dobbs, and B. Nine. 1980. Microbial activity of trench leachates from shallow-land, low-level radioactive waste disposal sites. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 40:108-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Francis, C., M. Timpson, and J. Wilson. 1999. Bench- and pilot-scale studies relating to the removal of uranium from uranium-contaminated soils using carbonate and citrate lixiviants. J. Hazard. Mater. 66:67-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gordon, D., C. Abajian, and P. Green. 1998. Consed: a graphical tool for sequence finishing. Genome Res. 8:195-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holmes, B. 2006. The genera Flavobacterium, Sphingobacterium, and Weeksella, p. 539-548. In M. Dworkin, S. Falkow, E. Rosenberg, K. Schleifer, and E. Stackebrandt (ed.), The prokaryotes, 3rd ed., vol. 7. Springer Science & Business Media, LLC, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hreggvidsson, G., E. Kaiste, O. Holst, G. Eggertsson, A. Palsdottir, and J. Kristjansson. 1996. An extremely thermostable cellulase from the thermophilic eubacterium Rhodothermus marinus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:3047-3049. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huber, T., G. Faulkner, and P. Hugenholtz. 2004. Bellerophon: a program to detect chimeric sequences in multiple sequence alignments. Bioinformatics 20:2317-2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hull, L., C. Grossman, R. Fjeld, J. Coates, and A. Elzerman. 2002. Estimating uranium partition coefficients from laboratory adsorption isotherms. INEEL/CON-02-00106. Idaho National Engineering and Environmental Laboratory, Idaho Falls, ID.

- 27.Humphreys, P., R. McGarry, A. Hoffmann, and P. Binks. 1997. DRINK: a biogeochemical source term model for low level radioactive waste disposal sites. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 20:557-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Janssen, P. 2006. Identifying the dominant soil bacterial taxa in libraries of 16S rRNA and 16S rRNA genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:1719-1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johansen, J., P. Nielsen, and C. Sjoholm. 1999. Description of Cellulophaga baltica gen. nov., sp. nov. and Cellulophaga fucicola gen. nov., sp. nov. and reclassification of Cytophaga lytica to Cellulophaga lytica gen. nov., comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 49:1231-1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kämpfer, P. 2006. The family Streptomycetaceae, part I: taxonomy, p. 538-604. In M. Dworkin, S. Falkow, E. Rosenberg, K. Schleifer, and E. Stackebrandt (ed.), The prokaryotes, 3rd ed., vol. 3. Springer Science & Business Media, LLC, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kashefi, K., and D. Lovley. 2000. Reduction of Fe (III), Mn (IV), and toxic metals at 100°C by Pyrobaculum islandicum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:1050-1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keck, K., and R. Seitz. 2002. Potential for subsidence at the low-level radioactive waste disposal area. INEEL/EXT-02-01154. Idaho National Engineering and Environmental Laboratory, Idaho Falls, ID.

- 33.Khan, S., Y. Fukunaga, Y. Nakagawa, and S. Harayama. 2007. Emended descriptions of the genus Lewinella and of Lewinella cohaerens, Lewinella nigricans and Lewinella persica, and description of Lewinella lutea sp. nov. and Lewinella marina sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 57:2946-2951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khan, S., Y. Nakagawa, and S. Harayama. 2007. Sediminibacter furfurosus gen. nov., sp. nov. and Gilvibacter sediminis gen. nov., sp. nov., novel members of the family Flavobacteriaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 57:265-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kroppenstedt, R., and M. Goodfellow. 2006. The family Thermomonosporaceae: Actinocorallia, Actinomadura, Spirillospora and Thermomonospora, p. 682-724. In M. Dworkin, S. Falkow, E. Rosenberg, K. Schleifer, and E. Stackebrandt (ed.), The prokaryotes, 3rd ed., vol. 3. Springer Science & Business Media, LLC, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Labeda, D., and R. Kroppenstedt. 2004. Emended description of the genus Glycomyces and description of Glycomyces algeriensis sp. nov., Glycomyces arizonensis sp. nov. and Glycomyces lechevalierae sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54:2343-2346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Labeda, D., R. Testa, M. Lechevalier, and H. Lechevalier. 1985. Glycomyces, a new genus of the Actinomycetales. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 35:417-421. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leschine, S. 1995. Cellulose degradation in anaerobic environments. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 49:399-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu, C., Y. Gorby, J. Zachara, J. Fredrickson, and C. Brown. 2002. Reduction kinetics of Fe (III), Co (III), U (VI), Cr (VI), and Tc (VII) in cultures of dissimilatory metal-reducing bacteria. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 80:637-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lloyd, J., C. Harding, and L. Macaskie. 1997. Tc (VII) reduction and accumulation by immobilized cells of Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 55:505-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lozupone, C., and R. Knight. 2005. UniFrac: a new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:8228-8235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ludwig, W., O. Strunk, R. Westram, L. Richter, and H. Meier. 2004. ARB: a software environment for sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:1363-1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lynd, L., P. Weimer, W. van Zyl, and I. Pretorius. 2002. Microbial cellulose utilization: fundamentals and biotechnology. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66:406-577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Means, J., D. Crerar, and J. Duguid. 1978. Migration of radioactive wastes: radionuclide mobilization by complexing agents. Science 200:1477-1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ortiz-Bernad, I., R. Anderson, H. Vrionis, and D. Lovley. 2004. Vanadium respiration by Geobacter metallireducens: novel strategy for in situ removal of vanadium from groundwater. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:3091-3095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peplies, J., R. Kottmann, W. Ludwig, and F. Glöckner. 2008. A standard operating procedure for phylogenetic inference (SOPPI) using (rRNA) marker genes. J. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 31:251-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Read, D., D. Ross, and R. Sims. 1998. The migration of uranium through Clashach Sandstone: the role of low molecular weight organics in enhancing radionuclide transport. J. Contam. Hydrol. 35:235-248. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roh, Y., S. Liu, G. Li, H. Huang, T. Phelps, and J. Zhou. 2002. Isolation and characterization of metal-reducing Thermoanaerobacter strains from deep subsurface environments of the Piceance Basin, Colorado. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:6013-6020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saeed, A., V. Sharov, J. White, J. Li, W. Liang, N. Bhagabati, J. Braisted, M. Klapa, T. Currier, and M. Thiagarajan. 2003. TM4: a free, open-source system for microarray data management and analysis. Biotechniques 34:45-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Safo-Sampah, S., and J. Torrey. 1988. Polysaccharide-hydrolyzing enzymes of Frankia (Actinomycetales). Plant Soil 112:89-97. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sagaram, U., K. Deangelis, P. Trivedi, G. Andersen, S. Lu, and N. Wang. 2009. Bacterial diversity analysis of Huanglongbing pathogen-infected citrus using PhyloChips and 16S rDNA clone library sequencing. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:1566-1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sani, R., B. Peyton, W. Smith, W. Apel, and J. Petersen. 2002. Dissimilatory reduction of Cr (VI), Fe (III), and U (VI) by Cellulomonas isolates. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 60:192-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saunders, J., and L. Toran. 1995. Modeling of radionuclide and heavy metal sorption around low-and high-pH waste disposal sites at Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Appl. Geochem. 10:673-684. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schloss, P., and J. Handelsman. 2005. Introducing DOTUR, a computer program for defining operational taxonomic units and estimating species richness. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:1501-1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schloss, P., and J. Handelsman. 2006. Toward a census of bacteria in soil. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2:786-793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shelobolina, E., S. Sullivan, K. O'Neill, K. Nevin, and D. Lovley. 2004. Isolation, characterization, and U (VI)-reducing potential of a facultatively anaerobic, acid-resistant bacterium from low-pH, nitrate-and U (VI)-contaminated subsurface sediment and description of Salmonella subterranea sp. nov. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:2959-2965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sunagawa, S., T. Desantis, Y. Piceno, E. Brodie, M. Desalvo, C. Voolstra, E. Weil, G. Andersen, and M. Medina. 2009. Bacterial diversity and white plague disease-associated community changes in the Caribbean coral Montastraea faveolata. ISME J. 3:512-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thompson, E. 2002. Historical description of radioactive waste management complex (RWMC) surrogated buried waste test pits for environmental restoration (ER) waste area group 7 (WAG-7) operable unit (OU) 7-13 & 7-14. Idaho National Laboratory, Idaho Falls, ID.

- 59.Viamajala, S., B. Peyton, W. Apel, and J. Petersen. 2002. Chromate reduction in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 is an inducible process associated with anaerobic growth. Biotechnol. Prog. 18:290-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vilks, P., F. Caron, and M. Haas. 1998. Potential for the formation and migration of colloidal material from a near-surface waste disposal site. Appl. Geochem. 13:31-42. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vobis, G. 2006. The genus Actinoplanes and related genera, p. 623-653. In M. Dworkin, S. Falkow, E. Rosenberg, K. Schleifer, and E. Stackebrandt (ed.), The prokaryotes, 3rd ed., vol. 3. Springer Science & Business Media, LLC, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.