Abstract

Norway spruce (Picea abies) forests exhibit lower annual atmospheric methane consumption rates than do European beech (Fagus sylvatica) forests. In the current study, pmoA (encoding a subunit of membrane-bound CH4 monooxygenase) genes from three temperate forest ecosystems with both beech and spruce stands were analyzed to assess the potential effect of tree species on methanotrophic communities. A pmoA sequence difference of 7% at the derived protein level correlated with the species-level distance cutoff value of 3% based on the 16S rRNA gene. Applying this distance cutoff, higher numbers of species-level pmoA genotypes were detected in beech than in spruce soil samples, all affiliating with upland soil cluster α (USCα). Additionally, two deep-branching genotypes (named 6 and 7) were present in various soil samples not affiliating with pmoA or amoA. Abundance of USCα pmoA genes was higher in beech soils and reached up to (1.2 ± 0.2) × 108 pmoA genes per g of dry weight. Calculated atmospheric methane oxidation rates per cell yielded the same trend. However, these values were below the theoretical threshold necessary for facilitating cell maintenance, suggesting that USCα species might require alternative carbon or energy sources to thrive in forest soils. These collective results indicate that the methanotrophic diversity and abundance in spruce soils are lower than those of beech soils, suggesting that tree species-related factors might influence the in situ activity of methanotrophs.

Methanotrophic bacteria in aerated soils contribute significantly to the global flux of methane (CH4) and consume about 30 Tg year−1 of atmospheric CH4 (12). Forest soils are considered to be the most effective sinks of CH4 among these soils (8, 48). Atmospheric CH4 oxidation and the methanotrophic communities in forest soils may be affected by various abiotic factors, e.g., pH, water content, and soil temperature (32).

Cultivated methanotrophs belong to the families Methylocystaceae and Beijerinckiaceae (both Alphaproteobacteria), Methylococcaceae (Gammaproteobacteria), and the recently proposed Methylacidiphilaceae (Verrucomicrobia) (43). Most of these cultivated species are restricted to one-carbon compounds as carbon and energy sources (53). Only Methylocella species may grow on multicarbon compounds (9). Isolates of Methylocystis (i.e., strains LR1, DWT, and SC2) utilize atmospheric CH4 (1.8 ppm by volume [ppmv]); however, growth is not apparent at this concentration (3, 16, 28).

Genes of the CH4 monooxygenase (MMO) are well-established functional markers of methanotrophs (38). pmoA encodes the hydroxylase of membrane-bound CH4 monooxygenase (pMMO) while mmoX encodes the corresponding subunit of cytoplasmic CH4 monooxygenase (sMMO). Facultative methanotrophic species of Methylocella exclusively possess sMMO and thus will not be detected in pmoA analyses (10, 38). Atmospheric CH4-oxidizing communities have been analyzed in a variety of forest soils, and Methylocystis species and upland soil cluster α (USCα)-affiliated genotypes are detected in most of these soils (32). Methanotrophs affiliated with USCγ and clusters 1 and 5 are also abundant or even dominant at certain forest sites (30, 31, 33). Numbers of methanotrophs in forest soil range from 0.4 × 106 to 21 × 106 cells per g of dry weight (gDW) as determined by quantitative PCR (qPCR) (29, 33), and these bacteria have resisted cultivation (32).

Coniferous forests can have lower annual atmospheric CH4 uptake rates than deciduous forests (6, 40). European beech (Fagus sylvatica) soils exhibit a lower capacity to oxidize CH4 than Norway spruce (Picea abies) soils, indicating a causative effect of tree species on methanotrophic community (11). In the current study, the methanotrophic community composition and abundance of methanotrophs in soil from forests with adjacent beech and spruce stands were assessed to evaluate the potential effect of tree species on methanotrophic communities.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study sites and sampling.

Soil samples were taken from three temperate forests with European beech (F. sylvatica) and adjacent Norway spruce (P. abies) stands in Germany, i.e., Solling, Steigerwald, and Unterlüß. Soils at any sampling site were classified as dystric cambisols (11). Five soil cores were taken at each of the six sites and stored in open plastic bags at 5°C for up to 4 days until they were separated into depth layers, manually homogenized, and frozen at −80°C. Soil pH values were similar at beech and spruce sites and ranged from 3.9 to 5.4 (11). Samples from the Oa horizon (blackish humic layer) and from mineral soil at a depth of 0 to 5 cm (0- to 5-cm soil) were pooled and used for molecular community analyses since these layers exhibited the highest atmospheric CH4 oxidation rates (11).

DNA extraction.

DNA was extracted from 0.3 g of frozen soil (0.1 g of Oa horizon plus 0.2 g of 0- to 5-cm mineral soil) according to the protocol of Stralis-Pavese and colleagues (51) by mechanical, chemical, and enzymatic lysis. The following four modifications to the protocol were made. (i) Lysis buffer I used for initial extraction of soil also contained 20 mg ml−1 of polyvinyl pyrrolidone. (ii) Lysis buffer II for reextraction of soil samples was identical with buffer I. However, polyvinyl pyrrolidone and lysozyme were not added. (iii) The DNA pellet was dried for 15 min at 40°C after the washing step. (iv) DNA was eluted with Tris-HCl (pH 8.0). DNA extracts were quantified using a Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA kit (Invitrogen, Germany). For each of the 30 soil cores, DNA was extracted in triplicate, i.e., 90 extracts in total.

PCR and cloning.

Gene libraries of pmoA, mmoX, and Verrucomicrobia-related pmoA were set up. DNA extracts in triplicate per soil sample were pooled, and 1 ng of DNA was used as a template in PCRs. PCR premix F (Epicentre) combined with an Invitrogen Taq polymerase recombinant (Invitrogen, Germany) was used. pmoA was amplified with primers A189f (GGN GAC TGG GAC TTC TGG) and A682r (GAA SGC NGA GAA GAA SGC) (500 nM) (20). The initial denaturation step was at 94°C for 5 min, and the final elongation was at 72°C for 10 min. Denaturation and elongation during repeated PCR cycles was at 94°C (1 min) and 72°C (1 min), respectively. An 11-cycle touchdown was performed with a stepwise decrease of the annealing temperature from 65°C to 55°C (1 min), followed by 24 cycles with an annealing temperature of 55°C (1 min). Taq DNA polymerase was added after the initial denaturation step. mmoX was amplified with primers mmoX206f (ATC GCB AAR GAA TAY GCS CG) and mmoX886r (ACC CAN GGC TCG ACY TTG AA) (500 nM) (22). Five precycles with an annealing temperature of 56°C were performed, followed by 35 cycles at 59°C. Genomic DNA of Methylococcus capsulatus was used as positive control for pmoA- and mmoX-specific PCRs. Four novel primers were designed to prove the presence of methanotrophic Verrucomicrobia in the soil samples, i.e., Verruco29f (5′-AAG AYM GRA TGT GGT G-3′), Verruco120f (5′-GCC YAT AGG WGC RAC MT-3′), Verruco391r (5′-GTC CAT AGT ATT CCA C-3′), and Verruco500r (5′-ACD CCH CCN GCA AAR CT-3′). PCR was performed with pooled soil DNA extracts from all soil cores of the six sites (i.e., beech and spruce of Solling, Steigerwald, and Unterlüß). Since no positive control for Verrucomicrobia-related pmoA was available, PCR was performed with different primer combinations and annealing temperatures from 50°C to 70°C, with and without the addition of 0.12% bovine serum albumin (BSA), and as simple or nested assays.

PCR products were purified by agarose gel electrophoresis, and bands of the right size were excised and purified with a Montage Gel Extraction Kit (Millipore). Equal concentrations of all five PCR products of one sampling site were pooled and cloned by AGOWA (Germany). Per sampling site, 48 to 96 clones were sequenced by MacroGen (South Korea).

Sequence data analysis.

16S rRNA gene and pmoA gene sequences from 22 pure cultures were retrieved from GenBank (5). The gene fragments corresponded to regions amplified by the commonly used primer pair A189f and A682r (20) and the pair 27F and 1492R (35), respectively, and were further analyzed in ARB (36). Gene fragments were aligned, and pmoA sequences were in silico translated. Pairwise comparisons of all pmoA (DNA), PmoA (amino acids), and 16S rRNA gene sequences were performed to calculate the nucleotide or amino acid difference, D (18). The percentage sequence similarity of pmoA and PmoA sequence pairs was plotted versus the percentage sequence similarity of the 16S rRNA gene sequence pairs of the same strains. The similarity, S, was calculated according to the following equation: S = 1 − D.

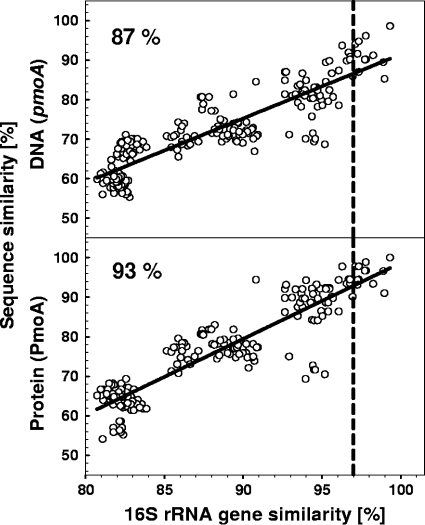

pmoA sequences retrieved from the six pmoA gene libraries of the sampled sites were aligned and in silico translated. Amino acid sequences were analyzed with the programs DOTUR (46) and ∫-LIBSHUFF (47) using an uncorrected distance matrix as input data set. The number of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) achieved by DOTUR was calculated for a 7% distance, which is an estimated cutoff value for methanotrophic species-level OTUs (Fig. 1). Coverage, C, of pmoA gene libraries was calculated according to the following equation, where n is the number of OTUs with only one sequence (singletons), and N is the number of clones examined: C = [1 − (n/N)] × 100.

FIG. 1.

Correlation of DNA and protein sequence similarity of pmoA and PmoA versus 16S rRNA gene similarity (22 pairwise comparisons of methanotrophic strains). The dashed line represents the 97% species cutoff value based on the 16S rRNA gene (49). Percentage values indicate the similarity cutoff value for species-level OTUs based on pmoA and PmoA sequence corresponding to distance values of 13% and 7%, respectively (intersection of dashed and regression line). R2 was 0.85 for the DNA panel and 0.79 for the protein panel. Accession numbers of analyzed sequences are given in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

qPCR assays targeting detected genotypes.

Bacteria were quantified with a modified assay established by Zaprasis and coworkers (55) using primers Eub341f (CCT ACG GGA GGC AGC AG) and Eub534r (ATT ACC GCG GCT GCT GG) (42). New qPCR assays (Q-USCα, Q-C7, and Q-AOB) were developed to assess the abundance of pmoA genes of USCα, pmoA and amoA genes of cluster 7 (C7), and amoA genes of ammonium oxidizing bacteria [AOB] within the Betaproteobacteria) detected in the soils. The following novel primers were designed and used in combination with common published primers (Table 1): USCα-346f (5′-TGG GYG ATC CTN GCN C-3′), C7-128r (5′-CCA ATG GGG AGC CTA AAT-3′), amoA38f (5′-AAT GGT GGC CGG TKG TNA C-3′), and amoA200r (5′-GAC CAC CAG TAR AAD CCC C-3′). The establishment of a primer system for the specific quantification of cluster 6 did not succeed; i.e., primers yielded unspecific by-products. Specificity of the novel qPCR assays was evaluated by means of nontarget DNA that had at least two mismatches at the binding site of the target group-specific primers. pmoA fragments of the different detected genotypes and of M. capsulatus (NCIMB 11853) were used as nontargets. Dilution series of target DNA quantified with a Quant-iT PicoGreen double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) kit (Invitrogen, Germany) were applied as quantitative calibration standards. A 16S rRNA gene fragment of Escherichia coli amplified with primers 27f and 907mr (35) was used as standard DNA for the Bacteria-targeting assay. For Q-USCα, Q-C7, and Q-AOB, an M13 PCR product of a respective clone insert for pmoA and amoA was used.

TABLE 1.

Conditions of qPCR assays

| Assay | Primers | Primer concn (nM) | Amplicon length (bp) | Annealing |

No. of PCR cycles | Efficiency (%)a | Detection limit (no. of genes per reaction) | Reference or source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temp (°C) | Time (s) | ||||||||

| Bacteria-targeting | Eub341f/Eub534r | 250 | 193 | 55.7 | 25 | 35 | 97 | 102 | 55 |

| Q-USCα | USCα-346f/A682r | 500 | 185 | 57.3 | 15 | 38 | 85 | 101 | This study |

| Q-AOB | amoA38f/amoA200r | 1,000 | 164 | 50.0 | 20 | 40 | 87 | 102 | This study |

| Q-C7 | A189f/C7-128r | 500 | 128 | 61.2 | 15 | 38 | 94 | 101 | This study |

| INHIB-CORRb | T7-Prom/M13r | 500 | 201 | 61.2 | 15 | 38 | 88 | 102 | This study |

Amplification efficiency as calculated by the iQ5 optical system software (version 2.0; Bio-Rad, Germany).

The assay was established to determine the quantitative degree of inhibition in qPCR measurements due to coextracted inhibitory compounds, such as humic acids.

All PCRs were performed in triplicate in 20-μl volumes using Thermosprint 96 PCR plates sealed with Thermosprint transparent sealing tapes (Bilatec, Germany). Five microliters of DNA template, i.e., 1 to 6 ng of DNA, were added to 15 μl of Master Mix containing the primers and the iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Germany). Final primer concentrations were 1,000 nM for Q-AOB and 500 nM for Q-USCα, Q-C7, and the Bacteria-targeting assay. The initial denaturation step was at 95°C for 8 min. Denaturation and elongation during PCR was at 95°C (30 s) and 72°C (15 s for Q-USCα and Q-C7, 20 s for Q-AOB, and 25 s for the Bacteria-targeting assay), respectively. Fluorescence data were acquired during the elongation step at 72°C since primer dimer formation was not evident by melting curve analysis. More details on the assays are presented in Table 1. qPCR was performed on an iCycler thermocycler with an iQ5 multicolor real-time PCR detection system. Data were analyzed with iQ5 optical system software (version 2.0; Bio-Rad, Germany).

Target group specificity of the assay Q-USCα was further evaluated by cloning (TOPO TA Cloning Kit; Invitrogen, Germany) purified (PCR purification kit; Qiagen, Germany) qPCR products derived from soil extracts and subsequent sequencing of 10 clone insert sequences. All retrieved sequences were pmoA genes and affiliated with USCα (data not shown).

Correction of qPCR measurements affected by coextracted inhibitory compounds.

The assay INHIB-CORR using primers T7-Prom (TAA TAC GAC TCA CTA TAG GG, Promega, Germany) and M13r (CAG GAA ACA GCT ATG ACC) (41) was established to calculate a factor correcting for PCR inhibition in each DNA extract caused by coextracted inhibitory compounds, such as humic substances (54). The vector region of the plasmid pCR 2.1-TOPO (Invitrogen, Germany) without a DNA insert amplified with primers M13f and M13r (41) served as a target for the assay INHIB-CORR and was used as inhibition control DNA. Every DNA extract was spiked with 0.2 × 104 inhibition control DNA molecules μl−1. Spiked DNA did not affect the amplification efficiency of the genotype-specific assays Q-USCα, Q-C7, and Q-AOB, and the Bacteria-targeting assay (data not shown). Final primer concentrations of the assay INHIB-CORR were 500 nM, and elongation during PCR was performed for 15 s. Further details are given in Table 1.

Spiked environmental DNA extracts were measured with genotype-specific assays and with INHIB-CORR. The logarithmic values of the starting quantity measured with the genotype-specific assays [lg(SQ)measured] were corrected for the inhibition factors determined with INHIB-CORR and for the difference in amplification efficiency (E) between the genotype-specific assays and INHIB-CORR (equation 1). Spiked DNA extracts were diluted to keep inhibition factors below a factor of 2. Corrected logarithmic values of the starting quantity [lg(SQ)corrected] were then converted to gene numbers per ng of DNA (ngDNA−1):

|

(1) |

For comparison of USCα gene abundances measured using the new Q-USCα assay with those measured using the assay FOREST (34) in a previous work (33), both assays were applied to the same DNA extracts. In silico coverage and measured numbers of USCα genes were compared (see Table S2 in the supplemental material).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

pmoA and amoA sequences were deposited at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) database under accession numbers FN564572 to FN564934.

RESULTS

pmoA- and PmoA-based distance cutoff values for estimating species-level OTUs of methanotrophs.

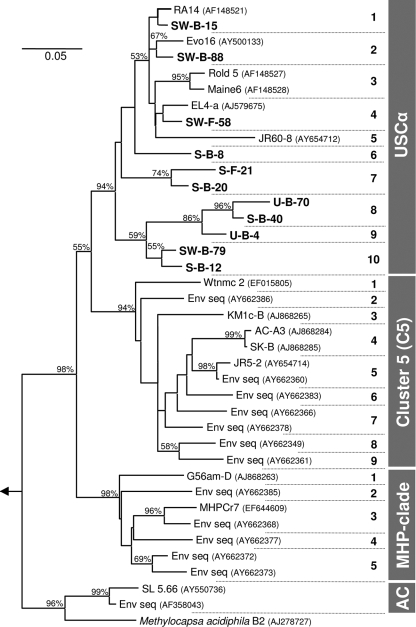

Sequence similarities of pmoAs and PmoAs and 16S rRNA genes of 22 methanotrophic isolates were linearly correlated, as suggested previously (19). This linear correlation was the basis to define distance cutoff values for methanotrophic species-level OTUs. The 97% species cutoff value based on 16S rRNA genes (49) corresponded with similarity cutoff values of 13% and 7% at the DNA and protein levels, respectively, for methanotrophic species-level pmoA-based OTUs (Fig. 1). Ten species-level USCα-affiliated OTUs (USCα 1 to 10) were resolved when these species-level cutoff values were used to analyze all available sequences (i.e., those published and those obtained in the current study) (Fig. 2). Clusters 5 and MHP were composed of nine and five species-level OTUs, respectively. Sequences within cluster AC (aquatic clones) and Methylocapsa acidiphila-related sequences formed separated OTUs. USCα and clusters 5 and MHP might represent three methanotrophic genera.

FIG. 2.

Dendrogram of species-level OTUs within USCα (30); clusters 5 (31), MHP (peat bog) (7), and AC (aquatic environments; named in this study); and Methylocapsa acidiphila-related sequences. Analysis of species-level OTUs was performed with 406 PmoA sequences based on a 7% sequence distance cutoff value using DOTUR (46). Analysis was restricted to amino acids 59 to 206 according to the PmoA of Methylococcus capsulatus Bath (NC_002977) and resulted in 26 different species-level OTUs. Thirty-nine selected sequences out of these 26 OTUs were used to construct a dendrogram in MEGA4 (52) using the neighbor-joining method (18) without evolutionary correction to apply the distance cutoff concept (10,000 bootstrap steps) (45). Bootstrap values higher than 50% are shown. Bold names indicate sequences from the current study. Accession numbers are given in parentheses. Bold numbers on the right side (1 to 10) represent different species-level OTUs within the corresponding clusters. The PmoA sequence of M. capsulatus Bath (NC_002977) was used as an out-group (arrow). The scale bar represents 5% sequence difference. Env seq, environmental sequence.

Detected genotypes.

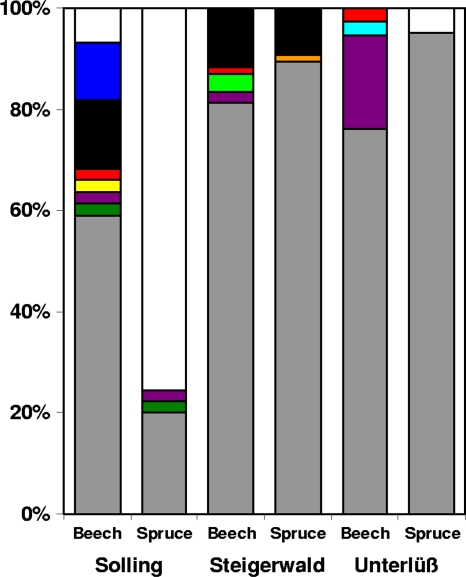

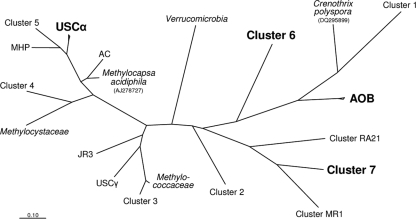

pmoA sequences were analyzed to resolve the identity of methanotrophic bacteria in pooled Oa horizon and mineral soil samples from the three forests, Solling, Steigerwald, and Unterlüß; 41 to 85 sequences were obtained per sampling site, with a total of 204 and 162 sequences from beech and spruce soils, respectively. Coverage of gene libraries based on the 7% distance cutoff value (Fig. 1) was close to 100% for most gene libraries, indicating sufficient sampling at most sites (Solling beech, 93%; Solling spruce, 82%; Steigerwald beech, 99%; Steigerwald spruce, 100%; Unterlüß beech, 100%; and Unterlüß spruce, 100%). Nine species-level OTUs were retrieved from beech soils (Fig. 3). These sequences affiliated with seven different OTUs within USCα (USCα-1, -2, -6, -7, -8, -9, and -10) and two deep-branching clusters (clusters 6 and 7) (Fig. 3 and 4) that might represent PmoA or AmoA sequences. Cluster 6 includes the environmental sequence EU723753 (retrieved from a forest soil) (26). The novel cluster 7 exclusively contains sequences obtained from Solling beech soil samples. In contrast, only five OTUs were detected in spruce soils (USCα-1, -4, -7, and -8 and cluster 6), indicating that methanotrophic diversity in spruce soils was lower than that in beech soils, as confirmed by statistical analysis (∫-LIBSHUFF, P < 0.05) (47). USCα-1 was the most frequently detected OTU associated with both tree species. USCα-1 includes RA14, the first pmoA genotype found to be potentially associated with atmospheric methane oxidation (21).

FIG. 3.

Community composition based on pmoA clone libraries. OTUs were defined according to a methanotrophic species-level cutoff value of 7%. Gene libraries were retrieved from pmoA PCR products from beech and spruce soils (Oa horizon pooled with 0- to 5-cm mineral soil) from three forests, Solling, Steigerwald, and Unterlüß. The numbers of analyzed sequences per clone library were as follows: Solling beech, 44; Solling spruce, 45; Steigerwald beech, 85; Steigerwald spruce, 75; Unterlüß beech, 75; and Unterlüß spruce, 41. Analysis was performed with 406 PmoA sequences using amino acids 59 to 206 according to the PmoA sequence of M. capsulatus Bath (NC_002977). Gray, USCα-1; dark green, USCα-7; purple, USCα-8; light green, USCα-2; orange, USCα-4; light blue, USCα-9; yellow, USCα-6; red, USCα-10; black, cluster 6; dark blue, cluster 7; white, ammonia-oxidizing bacteria within the Betaproteobacteria.

FIG. 4.

Phylogenetic tree showing the relationship of PmoA sequences obtained from forest soils in this study to known groups of PmoA and AmoA sequences. USCα (21), USCγ (30), cluster 1 (33), JR3 (2), and Methylocystaceae (16) represent putative atmospheric methane oxidizing genotypes. The tree was calculated based on amino acids 59 to 206 according to the PmoA sequence of M. capsulatus Bath (NC_002977) using the ARB-implemented PROML method (36) with the evolutionary model JTT (25). The scale bar represents 10% sequence difference. Accession numbers of sequences used for tree reconstruction are as follows: AF148521, AF148522, AF200729, AJ278727, AJ579669, AJ868245, AJ868259, AJ868265, AJ868278, AJ868281, AJ868409, AY550736, DQ295899, EF591085, EF644409, FJ970601, FN564735, FN564878, FN564924, FN564930, U76553, and NC_002977.

amoA sequences of Betaproteobacteria were occasionally found in Solling beech and Unterlüß spruce soils but not in Steigerwald soils. A high proportion of amoA sequences were detected in spruce soil from Solling (Fig. 3) and led to a lower coverage of methanotrophic OTUs than in other sampling sites and probably to an underestimation of methanotrophic diversity at this site. mmoX and Verrucomicrobia-related pmoA genes were not detected in any soil sample.

Abundance of methanotrophic, ammonia-oxidizing, and total Bacteria.

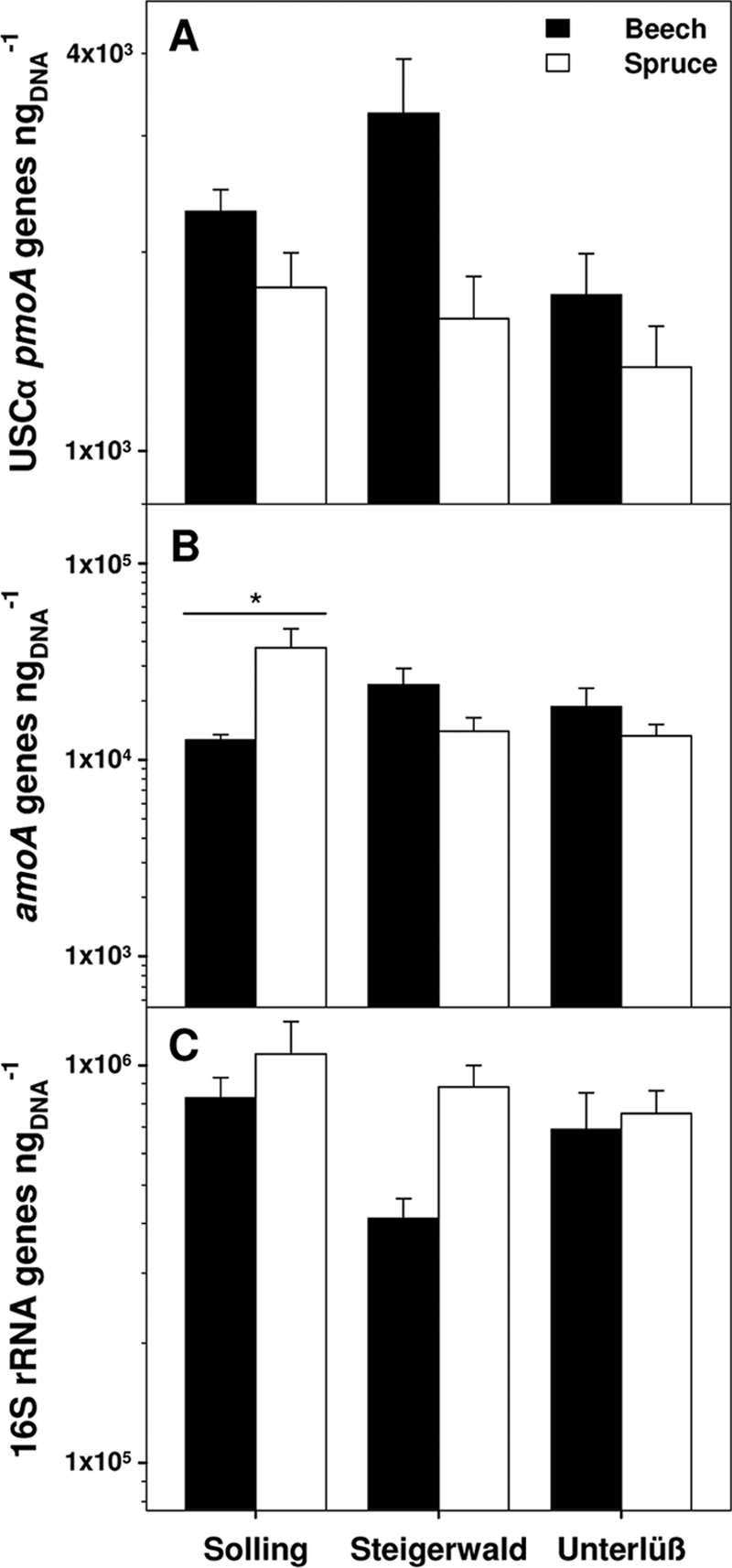

In silico coverage with the USCα primers used in the FOREST assay (34) approximated 86% of the USCα genotypes detected in the current study, whereas coverage with the new primers used in the new Q-USCα assay was 98% (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Q-USCα pmoA gene numbers exceeded those detected with FOREST by a factor of up to 8, as revealed from Steigerwald beech soil DNA extracts (see Table S2). Gene numbers of cluster 7 were below the detection limit of the corresponding qPCR assay (8.8 × 10−1 genes ngDNA−1). Abundance of USCα was higher in beech than in spruce soils at all three forest sites (Fig. 5A) (P > 0.05). USCα pmoA gene numbers ranged from 1.3 × 103 to 3.3 × 103 pmoA genes ngDNA−1, i.e., 0.3 × 108 to 1.2 × 108 pmoA genes gDW−1. amoA genes exceeded pmoA genes by a factor of 10, ranging from 1.3 × 104 to 3.7 × 104 amoA genes ngDNA−1, i.e., 0.3 × 109 to 2.6 × 109 amoA genes gDW−1 (Fig. 5B). Highest abundance of amoA genes was detected in Solling spruce soil samples. Abundance of bacterial 16S rRNA genes was generally higher in spruce soils than in beech soils (Fig. 5C). Gene numbers ranged from 0.4 × 106 to 1.1 × 106 16S rRNA genes ngDNA−1, i.e., 6.3 ×109 to 7.2 × 1010 16S rRNA genes gDW−1. Assuming that a methanotrophic cell contains two pmoA copies (50) and that a bacterial cell contains 4.13 16S rRNA gene copies (27), ratios of USCα to total Bacteria cell numbers were up to 2% and 0.5% for beech and spruce soils, respectively.

FIG. 5.

pmoA, amoA, and 16S rRNA gene numbers. Bars show the number of pmoA, amoA, and 16S rRNA genes measured by qPCR in beech and spruce soils from Solling, Steigerwald, and Unterlüß. Error bars indicate standard deviations of three replicate DNA extractions of five soil cores, i.e., from a total of 15 values. The asterisk indicates significant differences between beech and spruce soil (Mann-Whitney U test).

pmoA numbers and atmospheric CH4 oxidation rates of the six forest soils (11) were used to estimate atmospheric CH4 oxidation rates per cell. This calculated cell-specific activity was higher in beech than in spruce soil samples from Unterlüß and Solling, whereas cell-specific activities were similar in beech and spruce soils from Steigerwald (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Estimated cell-specific atmospheric CH4 oxidation rates of USCα

| Forest | Cell-specific CH4 oxidation rate (×10−18 mol of CH4 cell−1 h−1) by soil typea |

|

|---|---|---|

| Beech | Spruce | |

| Solling | 6.9 ± 1.5 | 1.5 ± 0.3 |

| Steigerwald | 14.0 ± 2.6 | 14.2 ± 2.1 |

| Unterlüß | 4.1 ± 0.7 | 1.8 ± 0.4 |

DISCUSSION

USCα is dominant in a variety of forest soils (24, 30, 32, 33). Consistently, pmoA sequences most frequently related to USCα were detected in pmoA gene libraries of Solling, Steigerwald, and Unterlüß forest soils in the current study. Clone libraries revealed a lower diversity of methanotrophic bacteria in spruce than in beech soils at all three sampling sites (Fig. 3), evidence that tree species affect methanotrophic community structure. USCα-1 was most frequently detected in both beech and spruce soils, indicating that this species-level OTU might constitute a dominant taxon.

Differences mainly occurred in less abundant species-level OTUs. USCα-2, -6, -9, and -10 and cluster 7 were not detected in spruce soils. Coniferous trees release monoterpenes that may reduce CH4 oxidation (1, 37). Atmospheric CH4 consumption rates are often lower in coniferous forest soils than in deciduous forest soils (6, 11, 40). USCα-2, -6, -9, and -10 and cluster 7 might represent genotypes that are more sensitive to monoterpenes than USCα-1, -4, -7, and -8 and cluster 6. Tree species did not affect methanotrophic community composition in a boreal tree succession experiment, as revealed by membrane lipid fingerprinting (39). However, the analysis of pmoA genes in the current study provides a more refined resolution of genotypes and facilitates the identification of methanotrophs on genus and species levels. Differences observed in the methanotrophic community structure between beech and spruce soils might reflect differences in monoterpene concentrations between coniferous and deciduous forests (37).

Methylocystis or alternative atmospheric CH4-oxidizing bacteria, such as those belonging to clusters 1 and 5 (32), were not detected in the forest soils of Solling, Steigerwald, and Unterlüß. mmoX genes were not detected, indicating that facultative methanotrophic species of the genus Methylocella and other sMMO-possessing methanotrophs were either not present or below the detection limit. Methanotrophic Verrucomicrobia bacteria were recently isolated from acidic environments (17, 23, 44). It was hypothesized that these bacteria might have been overlooked in other acidic environments due to their divergent pmoA gene that cannot be amplified with common pmoA primers (17). Nonetheless, Verrucomicrobia-like pmoA genes could not be amplified in the investigated soils with new primers that target pmoA1 and pmoA2 of Verrucomicrobia, suggesting the absence of this taxon. AOB of the genus Nitrosospira were highly abundant in Solling spruce soil (Fig. 3 and 5). This forest soil had a 3- to 13-fold higher ammonium content than the other soils (11), which might explain the high proportion of AOB in the gene library. It cannot be excluded that atmospheric CH4 was oxidized to some extent by AOB since CH4 is a substrate homolog for ammonia monooxygenase or that CH4 oxidation activity was lowered by the competitive inhibition of MMO by ammonium in the spruce soil of Solling forest (4, 13).

Abundance of USCα and its relative contribution to the total bacterial community were slightly higher in beech than in spruce soils (Fig. 5). pmoA gene numbers ranged from 0.3 × 108 to 1.2 × 108 pmoA genes gDW−1, values that exceeded those obtained with the FOREST assay (0.9 × 106 to 6.2 × 106 pmoA genes gDW−1) (29, 33). The primers used with the PCR assay FOREST cover only 81% of the available sequences (see Table S2 in the supplemental material), and the new Q-USCα assay yielded 8-fold higher gene numbers than the FOREST assay (see Table S2). Thus, the lower coverage of primers used in the FOREST assay might contribute to the differences in abundances measured in the previous and present study.

Calculated cell-specific CH4 oxidation rates were slightly higher in beech than in spruce soils (Table 2). A CH4 oxidation rate of at least 40 × 10−18 mol of CH4 cell−1 h−1 may be required for maintenance metabolism (33). Estimated USCα-specific oxidation rates approximated 800 × 10−18 mol of CH4 cell−1 h−1, suggesting that these organisms conserve enough energy for growth during the oxidation of atmospheric CH4 (33). However, these rates may have been overestimated since pmoA gene numbers were likely underestimated with the FOREST assay. Cell-specific CH4 oxidation rates calculated in the current study ranged from 1 × 10−18 to 14 × 10−18 mol of CH4 cell−1 h−1; these values are lower than required for maintenance of methanotrophic biomass, which raises the question of how atmospheric CH4 oxidizers are capable of growth in aerated soils (14). CH4 production was not measured in soil samples from the six sampling sites under anoxic conditions (11), and, thus, it is unlikely that USCα species grow also on CH4 produced in soil. Another possible survival mechanism would be the utilization of substrates other than or in addition to CH4 (14). It is known that Methylocella silvestris, which was isolated from a forest soil, is able to utilize alternative carbon compounds, such as acetate or methanol (9, 15). This suggests that USCα might rely on additional carbon sources to conserve enough energy for cell maintenance and growth. The capacity to use alternative carbon sources might thus lead to a high relative abundance of USCα (i.e., up to 2% of the total detected bacterial community), as has been observed in this study. Nonetheless, calculations of cell-specific CH4 oxidation rates are based on the detection of DNA and, thus, on the assumption that all detected genes represented active cells. This assumption might be not fully true and might have led to an underestimation of cell-specific CH4 oxidation rates.

Soil pH, temperature, and water content may impact community structure of methanotrophs (6, 8, 32). Nonetheless, different CH4 oxidation rates occur in acidic beech and spruce soils at equal matrix potentials and temperatures, indicating that tree species itself is an important environmental determinant of atmospheric CH4 consumption in forest soils (11). Monoterpenes have been proposed as factors that lower methanotrophic metabolic activities in spruce soils (1, 37). These collective results indicate that the methanotrophic diversity and abundance in spruce soils are lower than those of beech soils, suggesting that tree species-related factors might influence the in situ activity of methanotrophs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Henri Siljanen and Levente Bodrossy for providing the DNA extraction protocol and Egbert Matzner for support and helpful discussions.

The project was associated with the METHECO project within the EuroDIVERSITY program of the European Science Foundation (ESF). The study was financially supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant number KO2912/2-1), the ESF, and the University of Bayreuth.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 26 March 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amaral, J. A., and R. Knowles. 1998. Inhibition of methane consumption in forest soils by monoterpenes. J. Chem. Ecol. 24:723-734. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angel, R., and R. Conrad. 2009. In situ measurement of methane fluxes and analysis of transcribed particulate methane monooxygenase in desert soil. Environ. Microbiol. 11:2598-2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baani, M., and W. Liesack. 2008. Two isozymes of particulate methane monooxygenase with different methane oxidation kinetics are found in Methylocystis sp. strain SC2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:10203-10208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bédard, C., and R. Knowles. 1989. Physiology, biochemistry, and specific inhibitors of CH4, NH4+, and CO oxidation by methanotrophs and nitrifiers. Microbiol. Rev. 53:68-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benson, D. A., I. K. Karsch-Mizrachi, D. J. Lipman, J. Ostell, and D. L. Wheeler. 2008. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 36:D25-D30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borken, W., Y. J. Xu, and F. Beese. 2003. Conversion of hardwood forests to spruce and pine plantations strongly reduced soil methane sink in Germany. Glob. Chang. Biol. 9:956-966. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, Y., M. G. Dumont, N. P. McNamara, P. M. Chamberlain, L. Bodrossy, N. Stralis-Pavese, and J. C. Murrell. 2008. Diversity of the active methanotrophic community in acidic peatlands as assessed by mRNA and SIP-PLFA analyses. Environ. Microbiol. 10:446-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalal, R. C., and D. E. Allen. 2008. Greenhouse gas fluxes from natural ecosystems. Aust. J. Bot. 56:369-407. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dedysh, S. N., C. Knief, and P. F. Dunfield. 2005. Methylocella species are facultatively methanotrophic. J. Bacteriol. 187:4665-4670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dedysh, S. N., W. Liesack, V. N. Khmelenina, N. E. Suzina, Y. A. Trotsenko, J. D. Semrau, A. M. Bares, N. S. Panikov, and J. M. Tiedje. 2000. Methylocella palustris gen. nov., sp nov., a new methane-oxidizing acidophilic bacterium from peat bags, representing a novel subtype of serine-pathway methanotrophs. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 50:955-969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Degelmann, D. M., W. Borken, and S. Kolb. 2009. Methane oxidation kinetics differ in European beech and Norway spruce soils. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 60:499-506. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denman, K. L., G. Brasseur, A. Chidthaisong, P. Ciais, P. M. Cox, R. E. Dickinson, D. Hauglustaine, C. Heinze, E. Holland, D. Jacob, U. Lohmann, S. Ramachandran, P. L. da Silva Dias, S. C. Wofsy, and X. Zhang. 2007. Couplings between changes in the climate system and biogeochemistry, p. 499-587. In S. Solomon, D. Qin, M. Manning, Z. Chen, M. Marquis, K. B. Averyt, M. Tignor, and H. L. Miller (ed.), Climate change 2007: the physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the fourth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- 13.Dunfield, P., and R. Knowles. 1995. Kinetics of inhibition of methane oxidation by nitrate, nitrite, and ammonium in a humisol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:3129-3135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunfield, P. F. 2007. The soil methane sink, p. 152-170. In D. Reay, C. N. Hewitt, K. Smith, and J. Grace (ed.), Greenhouse gas sinks. CABI Publishing, Wallingfort, United Kingdom.

- 15.Dunfield, P. F., V. N. Khmelenina, N. E. Suzina, Y. A. Trotsenko, and S. N. Dedysh. 2003. Methylocella silvestris sp. nov., a novel methanotroph isolated from an acidic forest cambisol. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53:1231-1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunfield, P. F., W. Liesack, T. Henckel, R. Knowles, and R. Conrad. 1999. High-affinity methane oxidation by a soil enrichment culture containing a type II methanotroph. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:1009-1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunfield, P. F., A. Yuryev, P. Senin, A. V. Smirnova, M. B. Stott, S. Hou, B. Ly, J. H. Saw, Z. Zhou, Y. Ren, J. Wang, B. W. Mountain, M. A. Crowe, T. M. Weatherby, P. L. E. Bodelier, W. Liesack, L. Feng, L. Wang, and M. Alam. 2007. Methane oxidation by an extremely acidophilic bacterium of the phylum Verrucomicrobia. Nature 450:879-882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Felsenstein, J. 1985. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39:783-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heyer, J., V. F. Galchenko, and P. F. Dunfield. 2002. Molecular phylogeny of type II methane-oxidizing bacteria isolated from various environments. Microbiology 148:2831-2846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holmes, A. J., N. J. Owens, and J. C. Murrell. 1995. Detection of novel marine methanotrophs using phylogenetic and functional gene probes after methane enrichment. Microbiology 141:1947-1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holmes, A. J., P. Roslev, I. R. McDonald, N. Iversen, K. Henriksen, and J. C. Murrell. 1999. Characterization of methanotrophic bacterial populations in soils showing atmospheric methane uptake. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3312-3318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hutchens, E., S. Radajewski, M. G. Dumont, I. R. McDonald, and J. C. Murrell. 2004. Analysis of methanotrophic bacteria in Movile Cave by stable isotope probing. Environ. Microbiol. 6:111-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Islam, T., S. Jensen, L. J. Reigstad, O. Larsen, and N. K. Birkeland. 2008. Methane oxidation at 55°C and pH 2 by a thermoacidophilic bacterium belonging to the Verrucomicrobia phylum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:300-304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaatinen, K., C. Knief, P. F. Dunfield, K. Yrjälä, and H. Fritze. 2004. Methanotrophic bacteria in boreal forest soil after fire. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 50:195-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones, D. T., W. R. Taylor, and J. M. Thornton. 1992. The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 8:275-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.King, G. M., and K. Nanba. 2008. Distribution of atmospheric methane oxidation and methanotrophic communities in Hawaiian volcanic deposits and soils. Microbes Environ. 23:326-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klappenbach, J. A., P. R. Saxman, J. R. Cole, and T. M. Schmidt. 2001. rrndb: the ribosomal RNA operon copy number database. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:181-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knief, C., and P. F. Dunfield. 2005. Response and adaptation of different methanotrophic bacteria to low methane mixing ratios. Environ. Microbiol. 7:1307-1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knief, C., S. Kolb, P. L. Bodelier, A. Lipski, and P. F. Dunfield. 2006. The active methanotrophic community in hydromorphic soils changes in response to changing methane concentration. Environ. Microbiol. 8:321-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knief, C., A. Lipski, and P. F. Dunfield. 2003. Diversity and activity of methanotrophic bacteria in different upland soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:6703-6714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knief, C., S. Vanitchung, N. W. Harvey, R. Conrad, P. F. Dunfield, and A. Chidthaisong. 2005. Diversity of methanotrophic bacteria in tropical upland soils under different land uses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:3826-3831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kolb, S. 2009. The quest for atmospheric methane oxidizers in forest soils. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 1:336-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kolb, S., C. Knief, P. F. Dunfield, and R. Conrad. 2005. Abundance and activity of uncultured methanotrophic bacteria involved in the consumption of atmospheric methane in two forest soils. Environ. Microbiol. 7:1150-1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kolb, S., C. Knief, S. Stubner, and R. Conrad. 2003. Quantitative detection of methanotrophs in soil by novel pmoA-targeted real-time PCR assays. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:2423-2429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lane, D. J. 1991. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing, p. 115-175. In E. Stackebrandt and M. Goodfellow (ed.), Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. John Wiley and Sons Ltd., Chichester, United Kingdom.

- 36.Ludwig, W., O. Strunk, R. Westram, L. Richter, H. Meier, Yadhukumar, A. Buchner, T. Lai, S. Steppi, G. Jobb, W. Förster, I. Brettske, S. Gerber, A. W. Ginhart, O. Gross, S. Grumann, S. Hermann, R. Jost, A. König, T. Liss, R. Lüßmann, M. May, B. Nonhoff, B. Reichel, R. Strehlow, A. Stamatakis, N. Stuckmann, A. Vilbig, M. Lenke, T. Ludwig, A. Bode, and K.-H. Schleifer. 2004. ARB: a software environment for sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:1363-1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maurer, D., S. Kolb, L. Haumeier, and W. Borken. 2008. Inhibition of atmospheric methane oxidation by monoterpenes in Norway spruce and European beech soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 40:3014-3020. [Google Scholar]

- 38.McDonald, I. R., L. Bodrossy, Y. Chen, and J. C. Murrell. 2008. Molecular ecology techniques for the study of aerobic methanotrophs. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:1305-1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Menyailo, O. V., W. R. Abraham, and R. Conrad. 2010. Tree species affect atmospheric CH4 oxidation without altering community composition of soil methanotrophs. Soil Biol. Biochem. 42:101-107. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Menyailo, O. V., and B. A. Hungate. 2003. Interactive effects of tree species and soil moisture on methane consumption. Soil Biol. Biochem. 35:625-628. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Messing, J. 1983. New M13 vectors for cloning. Methods Enzymol. 101:20-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muyzer, G., E. C. Dewaal, and A. G. Uitterlinden. 1993. Profiling of complex microbial populations by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of polymerase chain reaction-amplified genes coding for 16S ribosomal RNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:695-700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Op den Camp, H. J. M., T. Islam, M. B. Stott, H. R. Harhangi, A. Hynes, S. Schouten, M. S. M. Jetten, N. K. Birkeland, A. Pol, and P. F. Dunfield. 2009. Environmental, genomic and taxonomic perspectives on methanotrophic Verrucomicrobia. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 1:293-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pol, A., K. Heijmans, H. R. Harhangi, D. Tedesco, M. S. M. Jetten, and H. J. M. Op den Camp. 2007. Methanotrophy below pH 1 by a new Verrucomicrobia species. Nature 450:874-878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saitou, N., and M. Nei. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4:406-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schloss, P. D., and J. Handelsman. 2005. Introducing DOTUR, a computer program for defining operational taxonomic units and estimating species richness. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:1501-1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schloss, P. D., B. R. Larget, and J. Handelsman. 2004. Integration of microbial ecology and statistics: a test to compare gene libraries. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:5485-5492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith, K. A., K. E. Dobbie, B. C. Ball, L. R. Bakken, B. K. Sitaula, S. Hansen, R. Brumme, W. Borken, S. Christensen, A. Prieme, D. Fowler, J. A. Macdonald, U. Skiba, L. Klemedtsson, A. Kasimir-Klemedtsson, A. Degorska, and P. Orlanski. 2000. Oxidation of atmospheric methane in Northern European soils, comparison with other ecosystems, and uncertainties in the global terrestrial sink. Glob. Chang. Biol. 6:791-803. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stackebrandt, E., and B. M. Goebel. 1994. Taxonomic note: a place for DNA-DNA reassociation and 16S rRNA sequence analysis in the present species definition in bacteriology. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 44:846-849. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stolyar, S., A. M. Costello, T. L. Peeples, and M. E. Lidstrom. 1999. Role of multiple gene copies in particulate methane monooxygenase activity in the methane-oxidizing bacterium Methylococcus capsulatus Bath. Microbiology 145:1235-1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stralis-Pavese, N., A. Sessitsch, A. Weilharter, T. Reichenauer, J. Riesing, J. Csontos, J. C. Murrell, and L. Bodrossy. 2004. Optimization of diagnostic microarray for application in analysing landfill methanotroph communities under different plant covers. Environ. Microbiol. 6:347-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tamura, K., J. Dudley, M. Nei, and S. Kumar. 2007. MEGA4: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24:1596-1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trotsenko, Y. A., and J. C. Murrell. 2008. Metabolic aspects of aerobic obligate methanotrophy. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 63:183-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wintzingerode, F. V., U. B. Goebel, and E. Stackebrandt. 1997. Determination of microbial diversity in environmental samples: pitfalls of PCR-based rRNA analysis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 21:213-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zaprasis, A., Y. J. Liu, S. J. Liu, H. L. Drake, and M. A. Horn. 2010. Abundance of novel and diverse tfdA-like genes, encoding putative phenoxyalkanoic acid herbicide-degrading dioxygenases, in soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:119-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.