Abstract

Lipodystrophy with high nonesterified fatty acid (FA) efflux is reported in humans receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) to treat HIV infection. Ritonavir, a common component of HAART, alters adipocyte FA efflux, but the mechanism for this effect is not established. To investigate ritonavir-induced changes in FA flux and recycling through acylglycerols, we exposed differentiated murine 3T3-L1 adipocytes to ritonavir for 14 d. FA efflux, uptake, and incorporation into acylglycerols were measured. To identify a mediator of FA efflux, we measured adipocyte triacylglycerol lipase (ATGL) transcript and protein. To determine whether ritonavir-treated adipocytes increased glycerol backbone synthesis for FA reesterification, we measured labeled glycerol and pyruvate incorporation into triacylglycerol (TAG). Ritonavir-treated cells had increased FA efflux, uptake, and incorporation into TAG (all P < 0.01). Ritonavir increased FA efflux without consistently increasing glycerol release or changing TAG mass, suggesting increased partial TAG hydrolysis. Ritonavir-treated adipocytes expressed significantly more ATGL mRNA (P < 0.05) and protein (P < 0.05). Ritonavir increased glycerol (P < 0.01) but not pyruvate (P = 0.41), utilization for TAG backbone synthesis. Consistent with this substrate utilization, glycerol kinase transcript (required for glycerol incorporation into TAG backbone) was up-regulated (P < 0.01), whereas phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase transcript (required for pyruvate utilization) was down-regulated (P < 0.001). In 3T3-L1 adipocytes, long-term ritonavir exposure perturbs FA metabolism by increasing ATGL-mediated partial TAG hydrolysis, thus increasing FA efflux, and leads to compensatory increases in FA reesterification with glycerol and acylglycerols. These changes in FA metabolism may, in part, explain the increased FA efflux observed in ritonavir-associated lipodystrophy.

The lipodystrophy caused by ritonavir, a protease inhibitor used for treatment of HIV infection, may in part result from the ability of ritonavir to increase transcription of ATGL, an enzyme that catalyzes lipolysis in adipocytes.

Within visceral and sc adipose tissue, alterations in lipolysis that lead to increased cycling of fatty acids (FA) through acylglycerols can contribute to redistribution of adipose tissue stores (1,2,3). Region-specific lipoatrophy and lipohypertrophy have been described (4) in humans receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) for the treatment of HIV (5). An important contributor to intracellular lipid flux is partial or complete lipid hydrolysis followed by reesterification of FA to re-form triacylglycerol (TAG). Dyslipidemia, including but not limited to increased circulating nonesterified FA, has been reported to develop during HAART, particularly in patients prescribed regimens that include aspartic acid protease inhibitors such as ritonavir (6,7,8). Such reports suggest that dysfunction of adipose tissue may play an important role in development of HIV-associated lipodystrophy syndrome through dysregulation of fatty acid metabolism.

Several previous studies have used cultured adipocytes to identify cellular targets that may contribute to HIV-associated lipodystrophy syndrome. Investigations employing short-term exposure of both human and murine adipocytes to aspartic acid protease inhibitors have reported increased inflammatory cytokines in human adipocytes (9,10), decreased differentiation of murine cultured adipocytes (11,12), decreased insulin sensitivity (13), altered gene expression (14,15), and increased lipolysis (16,17). However, none of these reports has fully addressed the contribution of alterations in FA metabolism to the dyslipidemia reported in HIV-associated lipodystrophy.

We hypothesized that the increased plasma FA concentrations reported in humans with HIV-associated lipodystrophy might be due to failure of the adipocyte to effectively partition fatty acids into TAG and that such impairment might partially explain the resulting metabolic alterations. We therefore examined the effects of long-term exposure to the protease inhibitor ritonavir on fatty acid and glycerol flux, fatty acid reesterification, and use of alternative substrates for glycerol backbone synthesis in 3T3-L1 adipocytes.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and protease inhibitor treatment

Crystalline ritonavir was generously provided by Abbott Laboratories (Princeton, NJ) under a materials transfer agreement. Murine 3T3-L1 cells (Dr. Howard Green, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) were grown to confluence as previously described (18). Confluent cells were differentiated in DMEM supplemented as described above in the presence of 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 10−6 m dexamethasone, 0.5 mm 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine, and 5 μg/ml insulin for 72 h, with medium changed once every 24 h. In addition, differentiation medium contained a final concentration of 10 μm ritonavir in 0.1% ethanol or only the vehicle (0.1% ethanol). After differentiation, cells were maintained for a total of 11 more days in DMEM with 10% FBS containing either ritonavir or vehicle. Maintenance medium was changed every 24 h. All in vitro experiments were performed with 3T3-L1 adipocytes that were exposed to ritonavir or vehicle for a total of 14 d.

Treatment of 3T3-L1 adipocytes with triacsin C

To study the impact of inhibiting FA reesterification on ritonavir’s effects, cells were treated with triacsin C, which inhibits FA-facilitated transport and incorporation into TAG by inhibiting FA esterification to coenzyme A (CoA) (19). Cells were given fresh DMEM with 10% FBS and either ritonavir or vehicle and allowed to equilibrate for 0.5–1 h in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 C. All subsequent buffers and media also contained ritonavir or vehicle in addition to the other components specified, and all subsequent steps were performed in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 C. Adipocytes were washed two times with Krebs/Ringer/HEPES (KRH, prewarmed to 37 C) buffer (pH 7.4) containing 5 mm glucose. Cells were preincubated for 10 min with DMEM (without serum) with 25 mm glucose and 5% fatty acid-free BSA (Millipore, Billerica, MA) containing either 10 μm triacsin C (dissolved in 0.2% dimethylsulfoxide) (BIOMOL International, Plymouth Meeting, PA) or 0.2% dimethylsulfoxide alone. Subsequently, cells were FA loaded by exposure to labeled FA for 15 min (with or without triacsin C) using KRH with 5 mm glucose containing approximately 1 μCi [9,10-3H]palmitic acid (specific activity 31.0 Ci/mmol; PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Inc., Waltham, MA) complexed to BSA (20). After 15 min, the incubation medium was collected. Cells were washed two times with ice-cold KRH with 5 mm glucose and without BSA. Cell lysates were collected in ice-cold lysis buffer containing 10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 1 mm EDTA, 50 mm NaF, 100 nm okadaic acid, 20 μg/ml leupeptin, and 1 mm benzamidine. Cell lysates were sonicated for approximately 30 sec, and aliquots were counted in Biosafe II liquid scintillation fluid. Another aliquot was subjected to lipid extraction using the method of Folch et al. (21). FA and glycerol released in the media during the 15 min incubation were measured using the Wako HR Series NEFA kit (Wako Chemicals USA, Inc., Richmond, VA) and a radiometric glycerol assay (22), respectively.

Thin-layer chromatography (TLC)

Lipids from Folch extracts were resolved on plastic-backed TLC plates (20 × 20 cm with silica gel 60; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). TLC plates were developed using hexane/diethylether/glacial acetic acid (70:30:3). Lipids were visualized using iodine vapor. Regions from TLC plates were cut and placed in 10 ml Biosafe II scintillation fluid (Research Products International Corp., Mt. Prospect, IL). Lipids were extracted overnight in Biosafe II, and disintegrations per minute of labeled palmitate, glycerol, and pyruvate (as glycerol backbone) incorporated into TAG, diacylglycerol (DAG), and intracellular FA, were determined by liquid scintillation counting.

Glyceroneogenesis and glycerol recycling

We studied how ritonavir affected glycerol backbone formation from two substrates: direct phosphorylation of glycerol (a measure of recycling of glycerol) and formation of glycerol backbone from pyruvate (glyceroneogenesis). 3T3-L1 adipocytes were treated as previously described (23). Briefly, cells were washed in KRH without glucose and BSA and deprived of glucose for 3 h in KRH with 5% fatty acid-free BSA. Media were collected, and cells were loaded for 30 min with either 100 μm glycerol plus [2-3H]glycerol (6 μCi/well; GE Healthcare, Fairfield, CT) or 200 μm pyruvic acid plus [1-14C]pyruvic acid (6 μCi/well; GE Healthcare). The specific activities of the loading media were 0.05 ± 0.002 and 0.10 ± 0.001 (means with sem in picomoles per disintegration per minute) for glycerol- and pyruvate-containing buffers, respectively. Isotopes were included in all subsequent steps. After loading, cells were stimulated with 1 μm isoproterenol or not stimulated for an additional 2 h in KRH with 5% fatty acid-free BSA and without glucose. After the stimulation, media were collected, cells were washed two times with ice-cold KRH without BSA, and cell lysates were collected and analyzed by TLC as described above.

To assess mRNA expression of Gyk, PEPCK1, and ATGL, deoxyribonuclease-treated total RNA was prepared using the RNAqueous-4 PCR kit (Applied Biosystems/Ambion, Austin, TX), and 250 ng RNA was reverse transcribed using Invitrogen’s Superscript III Platinum Two-Step qRt-PCR kit. Real-time PCR was performed using Applied Biosystems TaqMan fluorescent gene expression assays containing predesigned primers for Gyk (Refseq NM_008194.3), PEPCK1 (Refseq NM_011044.2), and ATGL (Refseq NM_025802.2). To examine the effect of ritonavir on relative mRNA expression, expression ratios were calculated accounting for the efficiency of the PCR for both reference and target genes. The reference gene for all analyses was 18S rRNA.

Immunoblotting

3T3-L1 cells treated with either vehicle or ritonavir (14 d) were prepared for Western blot analyses by sonicating whole-cell lysates on ice in lysing buffer containing 25 mm HEPES (pH 7.5), 1 mm EDTA, 150 mm NaCl, 10 mm sodium pyrophosphate, 5 mm sodium fluoride, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mm sodium orthovanadate, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, and 10 μg/ml pepstatin A. Whole-cell lysates were extracted in Laemmli sample buffer with 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate. Fresh 55 mm dithiothreitol was added to the samples just before boiling. Total cellular protein was determined using the Bradford protein assay method (Bio-Rad, New York, NY), and equivalent amounts of protein were loaded per well. Immunoblots were probed with affinity-purified anti-ATGL (24) and affinity-purified anti-hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) (25). Signal was detected with secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase, an enhanced chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Scientific, formerly Pierce Biotechnology Inc., Rockford, IL). Quantitation of immunoblots was within the linear range of detection by enhanced chemiluminescence. Signal intensities on film for ATGL and HSL were quantified using laser scanning densitometry (PDSI; GE Healthcare, formerly Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ).

TAG analysis

Folch extracts were dried under nitrogen and resuspended in 95% ethanol. TAG in each extract was determined using both the triglyceride and free glycerol reagents (Sigma- Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Total triglycerides in each sample were calculated and expressed as picomoles triglyceride per microgram DNA.

DNA analysis

DNA content in whole-cell lysates was determined using bisbenzamide dye (26), and DNA assays were performed as previously described (16). Fluorescence was measured at an excitation wavelength of 356 nm and emission wavelength of 458 nm (fluorometer model LS 55; PerkinElmer).

Statistical analysis

Data were normalized for micrograms cellular DNA, a reflection of cell number. We analyzed data by ANOVA followed by Fisher protected least significant difference tests when the overall treatment effect was significantly different by ANOVA. Means were significantly different at P < 0.05. For quantification of gene expression with real-time PCR, mean expression ratios were calculated comparing relative expression of ritonavir-treated cells to vehicle (27) and compared with a hypothesized mean = 1. Expression ratios were considered significantly different from 1 at P < 0.05. All means are reported with se. Sample sizes and number of independent experiments are indicated in the figure legends.

Results

FA flux after 14 d ritonavir exposure

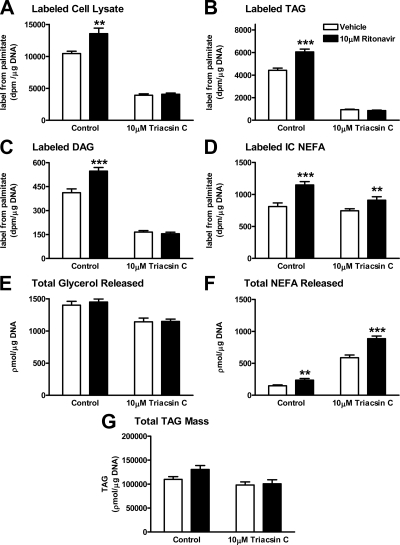

We labeled the already existing acylglycerol and FA intracellular pools with a tracer, [9,10-3H]palmitic acid, to assess uptake and deposition of FA at 15 min. In the absence of triacsin C, ritonavir increased intraadipocyte [3H]palmitate uptake and esterification (Fig. 1, A–C; control, left panels: P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively; and Supplemental Figure 1, published on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http://endo.endojournals.org). Triacsin C, which inhibits FA-facilitated transport by inhibiting esterification to CoA, inhibited the ritonavir-induced increase in labeled total cell lysate FA and in labeled intracellular esterified FA (Fig. 1, A–C; triacsin C, right panels; and Supplemental Figure 1). To demonstrate that ritonavir-induced changes in labeled FA uptake and labeled TAG were not due to differences in TAG mass, picomoles FA in whole-cell lysate and TAG were also normalized to picomoles TAG (Supplemental Figure 1). The ritonavir-induced increase in uptake and esterification persisted. However, triacsin C did not change the greater [3H]palmitate labeling of the intracellular FA pool in ritonavir-treated cells (Fig. 1D, P < 0.01; and Supplemental Figure 1, P < 0.001). Ritonavir treatment significantly increased extracellular FA release independently of the presence of triacsin C (Fig. 1F, P < 0.01), but this increase was not accompanied by any changes in glycerol release (Fig. 1E) or TAG mass (Fig. 1G).

Figure 1.

Effects of triacsin C on fatty acid uptake and disposition after ritonavir exposure. 3T3-L1 cells were exposed to ritonavir (black bars) or vehicle (white bars) during and after differentiation for a total of 14 d. Cells were pretreated with triacsin C or control medium for 10 min before labeling by addition of [9,10-3H]palmitic acid for a 15-min incubation. A, 3H in total cellular lysate; B, 3H in intracellular TAG; C, 3H in DAG; D, 3H in intracellular (IC) nonesterified FA pool; E and F, release of total glycerol (E) and total FA (F) during the 15-min incubation. All data are normalized for total cellular DNA. For all graphs, n = 18 from three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 for ritonavir vs. vehicle.

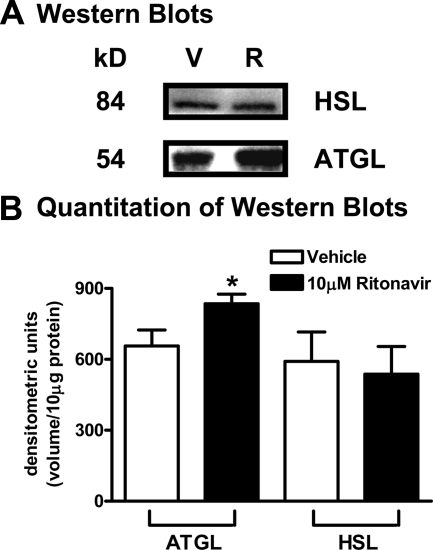

Steady-state ATGL mRNA and protein expression after 14 d ritonavir exposure

ATGL catalyzes the first step in TAG hydrolysis (TAG to diacylglycerol), resulting in greater FA flux (28). Using quantitative real-time PCR, we found ritonavir-treated adipocytes expressed significantly more steady-state ATGL mRNA (P < 0.05) when compared with vehicle (expression ratio = 1.27; n = 8 from two independent experiments). Correspondingly, ATGL protein expression, measured by Western analysis, was significantly increased (P < 0.05) in ritonavir-treated adipocytes when compared with vehicle (Fig. 2, A and B). When HSL protein expression was measured by Western analysis, protein expression was not different in ritonavir- and vehicle-treated adipocytes (537 ± 117.3 vs. 591 ± 125.1, P = 0.55; n = 9 from three independent experiments).

Figure 2.

Effects of ritonavir on ATGL and HSL protein expression. 3T3-L1 adipocytes treated with ritonavir or vehicle for 14 d. A, Representative ATGL and HSL Western blots (R, ritonavir; V, vehicle); B, quantitation of signal intensity from Western blots. All data are normalized for total cellular DNA. For B, n = 9, from three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05 for ritonavir (black bars) vs. vehicle (white bars).

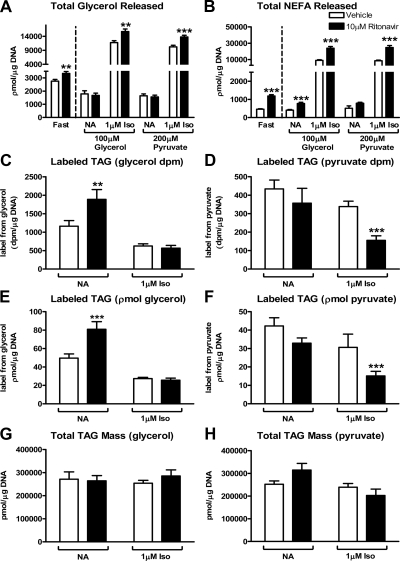

Ritonavir-mediated changes in glycerol recycling and glyceroneogenesis

Synthesis of glycerol-3-phosphate backbone from precursors other than glucose (29) is critical in recycling excess FA arising from lipolysis (1,30,31). We hypothesized that ritonavir-treated cells increase their use of substrates other than glucose to synthesize glycerol-3-phosphate for FA recycling. Therefore, we examined two pathways that produce glycerol-3-phosphate. This first one is the conversion of pyruvate to glycerol-3-phosphate, which is mainly regulated by the activity of cytosolic phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK1). The second pathway is direct phosphorylation of glycerol by glycerol kinase (Gyk) to produce glycerol-3-phosphate. We used an approach (23) in which cells are glucose deprived for 3 h and subsequently given glycerol or pyruvate as substrates for glycerol backbone synthesis. Ritonavir-treated cells released significantly more glycerol and FA extracellularly in response to glucose deprivation (Fig. 3, A and B, left panels). When nonstimulated cells were loaded with either glycerol or pyruvate, glycerol and FA release was diminished when compared with fasting (P < 0.001, Fig. 3, A and B, right panels). When ritonavir-treated cells were stimulated with isoproterenol, glycerol and FA release (Fig. 3, A and B, right panels) were significantly increased under both loading conditions.

Figure 3.

Effects of ritonavir in glucose-deprived 3T3-L1 cells on unstimulated and isoproterenol-stimulated lipolysis and glyceroneogenic capacity using glycerol or pyruvate. 3T3-L1 adipocytes were treated with ritonavir (black bars) or control medium (vehicle, white bars) for 14 d. Release of total glycerol (A) and total nonesterified FA (B) in response to 3 h glucose deprivation (Fast; left side of dashed line) followed by loading with either 100 μm unlabeled glycerol plus [2-3H]glycerol or 200 μm unlabeled pyruvate plus [1-14C]pyruvate for 30 min and subsequently studied after no additions (NA) in the nonstimulated state or after stimulation with 1 μm isoproterenol (Iso) for 2 h (right side of dashed line). C and D, Incorporation of [2-3H]glycerol (C) and [1-14C]pyruvic acid (D) into TAG. E, Incorporation of glycerol into TAG in picomoles per microgram DNA (label from either glycerol or pyruvate was converted to picomoles using specific activities reported in Materials and Methods). F, Incorporation of pyruvic acid (picomoles per microgram DNA) into TAG. G, Steady-state TAG mass in glycerol-loaded cells. H, Steady-state TAG mass in pyruvate-loaded cells. For all graphs, n = 15 from four independent experiments. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 for ritonavir vs. vehicle.

When given glycerol, nonstimulated ritonavir-treated cells incorporated significantly more labeled glycerol into TAG than vehicle when reported as disintegrations per minute or as picomoles incorporated (Fig. 3, C and E). However, labeled pyruvate incorporation into TAG was not different in nonstimulated ritonavir- and vehicle-treated cells (Fig. 3, D and F). During isoproterenol stimulation, when cells were glycerol loaded (Fig. 3, C and E), there was a significant loss of label (P < 0.001) from TAG backbone in both groups and no difference in glycerol labeled-TAG due to ritonavir treatment. In contrast, when cells were pyruvate loaded and isoproterenol stimulated (Fig. 3, D and F), ritonavir-treated cells had significantly less pyruvate label in TAG compared with vehicle. There were no differences in intracellular TAG mass in response to fasting of cells loaded with either glycerol or pyruvate (NA, Fig. 3, G and H), but during isoproterenol stimulation, ritonavir-treated cells loaded with pyruvate were not able to increase fatty acid reesterfication using pyruvate as a substrate for glycerol backbone synthesis resulting in significantly less TAG mass (P < 0.01 for isoproterenol vs. fasted, Fig. 3H).

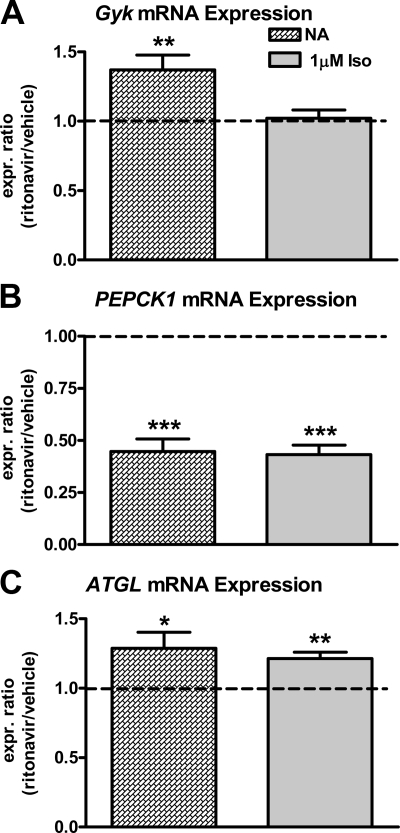

β-Adrenergic stimulation-induced changes in Gyk, PEPCK1, and ATGL mRNA expression after ritonavir treatment

We also studied 3T3-L1 adipocytes loaded with pyruvate (see above), to measure how β-adrenergic agonist stimulation would affect Gyk, PEPCK1, and ATGL transcripts in ritonavir-treated cells. When Gyk and PEPCK1 mRNA expression were measured in nonstimulated cells, ritonavir-treated cells had approximately 40% more Gyk transcript with no differences in Gyk transcript in isoproterenol-treated cells (Fig. 4A). On the contrary, ritonavir-treated cells expressed approximately 55% less PEPCK1 transcript (Fig. 4B) when compared with vehicle in both stimulated and nonstimulated cells. Vehicle-treated cells significantly increased Gyk expression in response to isoproterenol stimulation (nonstimulated vs. isoproterenol expression ratio = 1.5; P < 0.001), whereas Gyk expression in ritonavir-treated cells was unchanged (nonstimulated vs. isoproterenol expression ratio = 1.1; P = 0.17). Isoproterenol stimulation significantly (P < 0.01) induced PEPCK1 mRNA expression in both vehicle- and ritonavir-treated cells (nonstimulated vs. isoproterenol expression ratios = 39.7 and 34.4, respectively). However, ritonavir-treated cells still expressed less than half the PEPCK1 transcript observed in vehicle-treated cells (Fig. 4B). ATGL mRNA expression was significantly increased in both the nonstimulated condition (P < 0.05) and during isoproterenol stimulation (P < 0.01) in ritonavir-treated adipocytes when compared with vehicle (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Gyk, PEPCK1, and ATGL mRNA expression in 3T3-L1 adipocytes treated with ritonavir or vehicle for 14 d. A–C, Gyk (A), PEPCK1 (B), and ATGL (C) mRNA expression ratios in response to 3 h glucose deprivation followed by loading with 200 μm pyruvate for 30 min and subsequently not stimulated (NA, hatched bars) or stimulated with 1 μm isoproterenol (Iso, gray bars) for 2 h. Mean expression ratios with sem are reported. For all graphs, n = 8–9 from three independent experiments. See Fig. 3 for other details. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 for mean expression ratio different from 1.0.

Discussion

Increased FA efflux has been suggested as an important part of the development of the dyslipidemia observed in HIV-associated lipodystrophy syndrome (6,32,33,34,35). Therefore, we studied ritonavir-induced perturbations in adipocyte fatty acylglycerol metabolism. We hypothesized that chronic ritonavir exposure would induce greater FA flux in and out of the adipocyte, which could result in less effective FA buffering. Our data show that long-term ritonavir exposure increased ATGL-mediated partial hydrolysis of TAG, FA efflux, acylglycerol cycling, and facilitated transport and recycling of FA with no change in TAG mass. These changes induced by long-term ritonavir treatment agree with reported differences in futile cycling in human adipocytes from sc and omental depots after short-term exposure to protease inhibitors (36).

Ritonavir-treated cells had increased uptake and incorporation of labeled palmitate into TAG that was triacsin C sensitive. Triacsin C specifically inhibits acyl CoA synthases 1 and 4, which are involved in both active transport and activation of FA for incorporation into TAG (19). The data of the current study suggest that ritonavir-treated cells have increased triacsin C-sensitive active transport, because intracellular labeled FA concentrations were greater after ritonavir, and possibly increased acyl CoA synthase 1 and/or 4 activity, to account for their increased capacity to esterify FA into TAG and DAG. Although there is always the possibility of a nonspecific effect of triacsin C, our data are consistent with the idea that ritonavir treatment induces active transport and reesterification of FA. Furthermore, because TAG mass did not change due to ritonavir, these observations suggest that the FA reesterified are originating from increased partial TAG hydrolysis followed by compensatory up-regulated FA recycling to maintain TAG mass. We observed virtually complete compensation for hydrolysis in our closed cell culture system; however, we hypothesize that incomplete compensation might be observed in vivo in normal adipose tissue, where the presence of vasculature could enable FA relocation. Tissue-specific redistribution of FA primed by ritonavir-related TAG hydrolysis might then partially explain the peripheral lipodystrophy observed in humans after prolonged treatment with protease inhibitor-containing HAART regimens.

Indeed, despite increased FA recycling in ritonavir-treated adipocytes, excess FA efflux persisted independently of triacsin C treatment. Furthermore, increased FA efflux was accompanied by no change in glycerol release, HSL protein expression, or TAG mass. These data support the hypothesis that ATGL might be responsible for the excess FA flux observed in ritonavir-treated cells. We have previously reported that HSL protein expression was unchanged by ritonavir treatment of 3T3-L1 adipocytes despite increased FA efflux induced by β-adrenergic stimulation (16). HSL is considered the major lipase that preferentially catalyzes hydrolysis of DAG in adipocytes (37). We show in the current study that ATGL mRNA and protein expression are significantly increased by long-term ritonavir treatment with no change in HSL protein. Others have shown that overexpression of ATGL mRNA and protein in cultured adipocytes stimulates both glycerol and FA efflux (38) and increases fat mobilization in fasted mice (28). Although previous investigations have shown protease inhibitor-induced increases in FA efflux in vitro (16,17,39,40,41), changes in ATGL that might contribute to this effect have not been previously studied.

Ritonavir-treated adipocytes increased recycling of FA in a fashion that compensated for increased TAG hydrolysis. We hypothesized that ritonavir-treated adipocytes might also increase glycerol-3-phosphate synthesis from nonglucose precursors to support the increased FA reesterification required to maintain TAG mass. Glyceroneogenesis and glycerol recycling are critical pathways that are up-regulated during fasting or under conditions of decreased glucose supply and increase FA recycling (31,42,43). We studied ritonavir’s effects on glyceroneogenesis from pyruvate and glycerol recycling. Ritonavir-treated adipocytes up-regulated glycerol-3-phosphate synthesis from glycerol and increased Gyk transcript in nonstimulated, glucose-deprived cells. In contrast, PEPCK1 transcript was reduced by ritonavir treatment, and this reduction was not limited to the glucose-deprived state; we recently reported decreased PEPCK1 transcript in fed cells exposed to ritonavir (14). Reductions in PEPCK1 transcript in fed and fasted cells suggest a more generalized effect of ritonavir treatment on transcription of PEPCK1 rather than a difference due to altered nutritional status. We speculate that increased Gyk mRNA expression in ritonavir-treated cells may have been compensatory for lower PEPCK1 mRNA expression. Furthermore, changes in Gyk and PEPCK1 transcripts suggest that ritonavir treatment altered incorporation of specific substrates for TAG backbone synthesis through effects on transcription of the key rate-limiting enzymes for this process (31,44). Furthermore, ritonavir-treated cells did lose more TAG mass in response to fasting and subsequent isoproterenol stimulation when pyruvate was the substrate for TAG backbone synthesis, suggesting that ritonavir-treated cells used pyruvate less efficiently than glycerol to reesterify fatty acids into TAG. Interestingly, targeted ablation of PEPCK1 expression in white adipose tissue of mice results in a model that mimics lipodystrophy in a fraction of those mice (45). In addition, such mice have increased circulating free FA, suggesting an important role of PEPCK1 in promoting reesterification in white adipose tissue (45). Because in human adipocytes, glycerol phosphate formation by Gyk has been shown to account for only 14% of the total FA reesterified (46), a similar ritonavir-induced defect in PEPCK1-mediated glyceroneogenesis would be expected to induce even greater FA efflux in humans. Taken together, our data support the notion that ritonavir-treated cells have a higher rate of TAG hydrolysis and FA efflux and, subsequently, increased glycerol recycling (but not glyceroneogenesis from pyruvate) to assist in FA reesterification.

Although an in vitro murine adipocyte model does not fully recapitulate the complexity of the human condition observed in HIV-associated lipodystrophy syndrome, using a cell culture model allows manipulation of experimental conditions such that one can identify underlying mechanisms that might contribute to dyslipidemia. Thus, experiments verifying these findings in human adipocyte models should be carried out. Our experiments were designed to examine the long-term (14 d) effects of ritonavir exposure on adipocytes using a concentration typically achieved during HAART treatment. Previous studies have used acute ritonavir treatment (13,36,47), but it is possible that neither model accurately reflects the chronic effects of ritonavir on development of human HIV-associated lipodystrophy syndrome. Because previously, under our culturing conditions, there was no effect of ritonavir on adipocyte differentiation (14,16), we exposed adipocytes to ritonavir throughout differentiation to achieve as chronic an exposure to the drug as was possible. It is unknown whether different results would be found after shorter postdifferentiation ritonavir exposures or whether cells were differentiated and maintained in a more physiological glucose-containing medium rather than the supraphysiological (25 mm glucose) medium used. Additional studies should also examine whether ATGL is solely responsible for the increased TAG hydrolysis and FA efflux observed in ritonavir-treated adipocytes and examine the effects of other protease inhibitors used to treat HIV on FA cycling and substrate use for glycerol backbone synthesis.

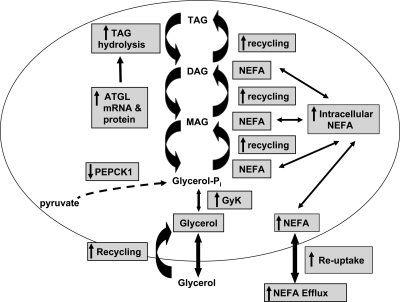

In sum, we have demonstrated alterations in adipocyte acylglycerol metabolism in ritonavir-treated adipocytes characterized by increased ATGL-mediated partial hydrolysis of TAG leading to increased FA efflux, increased FA-facilitated uptake, and increased FA and glycerol recycling (Fig. 5). We propose that increased FA flux and less effective FA partitioning into adipocytes leads to increased extracellular FA. These alterations in FA metabolism have been associated with metabolic dysfunction and may in part explain changes in tissue depot distribution commonly reported in the HIV-associated lipodystrophy syndrome that may occur among patients treated with ritonavir-containing regimens.

Figure 5.

Ritonavir’s effects on glycerolipid metabolism. Proposed model of ritonavir’s effects on FA cycling includes increased TAG hydrolysis, augmented recycling of both FA and glycerol, and inhibition of glyceroneogenesis from pyruvate. Abbreviations used: Glycerol-Pi, glycerol-3-phosphate; Gyk, glycerol kinase; MAG, monoacylglycerol; NEFA, nonesterified FA; PEPCK1, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Andrew S. Greenberg for generously providing ATGL antibody.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program, National Institutes of Health (NIH), Grant Z01-HD-00641 (to J.A.Y.) from National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). J.A.Y. is a Commissioned Officer in the U.S. Public Health Service, Department of Health and Human Services.

Disclosure Summary: All of the authors (D.A.W., E.L.G., N.E.W., and J.A.Y.) have nothing to declare. Ritonavir was supplied by Abbot under a materials transfer agreement with the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health.

First Published Online March 12, 2010

Abbreviations: CoA, Coenzyme A; DAG, diacylglycerol; FA, fatty acids; FBS, fetal bovine serum; HAART, highly active anti-retroviral therapy; HSL, hormone-sensitive lipase; KRH, Krebs/Ringer/HEPES; TAG, triacylglycerol; TLC, thin-layer chromatography.

References

- Cadoudal T, Leroyer S, Reis AF, Tordjman J, Durant S, Fouque F, Collinet M, Quette J, Chauvet G, Beale E, Velho G, Antoine B, Benelli C, Forest C 2005 Proposed involvement of adipocyte glyceroneogenesis and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase in the metabolic syndrome. Biochimie (Paris) 87:27–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentki M, Madiraju SR 2008 Glycerolipid metabolism and signaling in health and disease. Endocr Rev 29:647–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arner P 2005 Human fat cell lipolysis: biochemistry, regulation and clinical role. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 19:471–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kratz M, Purnell JQ, Breen PA, Thomas KK, Utzschneider KM, Carr DB, Kahn SE, Hughes JP, Rutledge EA, Van Yserloo B, Yukawa M, Weigle DS 2008 Reduced adipogenic gene expression in thigh adipose tissue precedes human immunodeficiency virus-associated lipoatrophy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:959–966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallon PW 2007 Pathogenesis of lipodystrophy and lipid abnormalities in patients taking antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Rev 9:3–15 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Valk M, Bisschop PH, Romijn JA, Ackermans MT, Lange JM, Endert E, Reiss P, Sauerwein HP 2001 Lipodystrophy in HIV-1-positive patients is associated with insulin resistance in multiple metabolic pathways. AIDS 15:2093–2100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Valk M, Reiss P, van Leth FC, Ackermans MT, Endert E, Romijn JA, Heijligenberg R, Sauerwein H 2002 Highly active antiretroviral therapy-induced lipodystrophy has minor effects on human immunodeficiency virus-induced changes in lipolysis, but normalizes resting energy expenditure. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:5066–5071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigouroux C, Gharakhanian S, Salhi Y, Nguyen TH, Chevenne D, Capeau J, Rozenbaum W 1999 Diabetes, insulin resistance and dyslipidaemia in lipodystrophic HIV-infected patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). Diabetes Metab 25:225–232 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagathu C, Eustace B, Prot M, Frantz D, Gu Y, Bastard JP, Maachi M, Azoulay S, Briggs M, Caron M, Capeau J 2007 Some HIV antiretrovirals increase oxidative stress and alter chemokine, cytokine or adiponectin production in human adipocytes and macrophages. Antivir Ther 12:489–500 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernochet C, Azoulay S, Duval D, Guedj R, Cottrez F, Vidal H, Ailhaud G, Dani C 2005 Human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitors accumulate into cultured human adipocytes and alter expression of adipocytokines. J Biol Chem 280:2238–2243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowell P, Flexner C, Kwiterovich PO, Lane MD 2000 Suppression of preadipocyte differentiation and promotion of adipocyte death by HIV protease inhibitors. J Biol Chem 275:41325–41332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, MacNaul K, Szalkowski D, Li Z, Berger J, Moller DE 1999 Inhibition of adipocyte differentiation by HIV protease inhibitors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 84:4274–4277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata H, Hruz PW, Mueckler M 2000 The mechanism of insulin resistance caused by HIV protease inhibitor therapy. J Biol Chem 275:20251–20254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler-Wailes DC, Guiney EL, Koo J, Yanovski JA 2008 Effects of ritonavir on adipocyte gene expression: evidence for a stress-related response. Obesity (Silver Spring) 16:2379–2387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker RA, Flint OP, Mulvey R, Elosua C, Wang F, Fenderson W, Wang S, Yang WP, Noor MA 2005 Endoplasmic reticulum stress links dyslipidemia to inhibition of proteasome activity and glucose transport by HIV protease inhibitors. Mol Pharmacol 67:1909–1919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler-Wailes DC, Liu H, Ahmad F, Feng N, Londos C, Manganiello V, Yanovski JA 2005 Effects of the human immunodeficiency virus-protease inhibitor, ritonavir, on basal and catecholamine-stimulated lipolysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:3251–3261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudich A, Vanounou S, Riesenberg K, Porat M, Tirosh A, Harman-Boehm I, Greenberg AS, Schlaeffer F, Bashan N 2001 The HIV protease inhibitor nelfinavir induces insulin resistance and increases basal lipolysis in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Diabetes 50:1425–1431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost SC, Lane MD 1985 Evidence for the involvement of vicinal sulfhydryl groups in insulin-activated hexose transport by 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Biol Chem 260:2646–2652 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin TM, Kim JH, Granger DA, Vance JE, Coleman RA 2001 Acyl-CoA synthetase isoforms 1, 4, and 5 are present in different subcellular membranes in rat liver and can be inhibited independently. J Biol Chem 276:24674–24679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Listenberger LL, Ory DS, Schaffer JE 2001 Palmitate-induced apoptosis can occur through a ceramide-independent pathway. J Biol Chem 276:14890–14895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folch J, Lees M, Sloane Stanley GH 1957 A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem 226:497–509 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley DC, Kaslow HR 1989 Radiometric assays for glycerol, glucose, and glycogen. Anal Biochem 180:11–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tordjman J, Chauvet G, Quette J, Beale EG, Forest C, Antoine B 2003 Thiazolidinediones block fatty acid release by inducing glyceroneogenesis in fat cells. J Biol Chem 278:18785–18790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi H, Perfield 2nd JW, Souza SC, Shen WJ, Zhang HH, Stancheva ZS, Kraemer FB, Obin MS, Greenberg AS 2007 Control of adipose triglyceride lipase action by serine 517 of perilipin A globally regulates protein kinase A-stimulated lipolysis in adipocytes. J Biol Chem 282:996–1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasaemle DL, Levin DM, Adler-Wailes DC, Londos C 2000 The lipolytic stimulation of 3T3-L1 adipocytes promotes the translocation of hormone-sensitive lipase to the surfaces of lipid storage droplets. Biochim Biophys Acta 1483:251–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downs TR, Wilfinger WW 1983 Fluorometric quantification of DNA in cells and tissue. Anal Biochem 131:538–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl MW 2001 A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 29:e45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann R, Strauss JG, Haemmerle G, Schoiswohl G, Birner-Gruenberger R, Riederer M, Lass A, Neuberger G, Eisenhaber F, Hermetter A, Zechner R 2004 Fat mobilization in adipose tissue is promoted by adipose triglyceride lipase. Science 306:1383–1386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JL, Peacock E, Samady W, Turner SM, Neese RA, Hellerstein MK, Murphy EJ 2005 Physiologic and pharmacologic factors influencing glyceroneogenic contribution to triacylglyceride glycerol measured by mass isotopomer distribution analysis. J Biol Chem 280:25396–25402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan HP, Li Y, Jensen MV, Newgard CB, Steppan CM, Lazar MA 2002 A futile metabolic cycle activated in adipocytes by antidiabetic agents. Nat Med 8:1122–1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson RW, Reshef L 2003 Glyceroneogenesis revisited. Biochimie (Paris) 85:1199–1205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadigan C, Borgonha S, Rabe J, Young V, Grinspoon S 2002 Increased rates of lipolysis among human immunodeficiency virus-infected men receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. Metabolism 51:1143–1147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadigan C, Rabe J, Meininger G, Aliabadi N, Breu J, Grinspoon S 2003 Inhibition of lipolysis improves insulin sensitivity in protease inhibitor-treated HIV-infected men with fat redistribution. Am J Clin Nutr 77:490–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meininger G, Hadigan C, Laposata M, Brown J, Rabe J, Louca J, Aliabadi N, Grinspoon S 2002 Elevated concentrations of free fatty acids are associated with increased insulin response to standard glucose challenge in human immunodeficiency virus-infected subjects with fat redistribution. Metabolism 51:260–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villarroya F, Domingo P, Giralt M 2007 Lipodystrophy in HIV 1-infected patients: lessons for obesity research. Int J Obes (Lond) 31:1763–1776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cianflone K, Zakarian R, Stanculescu C, Germinario R 2006 Protease inhibitor effects on triglyceride synthesis and adipokine secretion in human omental and subcutaneous adipose tissue. Antivir Ther 11:681–691 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zechner R, Kienesberger PC, Haemmerle G, Zimmermann R, Lass A 2009 Adipose triglyceride lipase and the lipolytic catabolism of cellular fat stores. J Lipid Res 50:3–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kershaw EE, Hamm JK, Verhagen LA, Peroni O, Katic M, Flier JS 2006 Adipose triglyceride lipase: function, regulation by insulin, and comparison with adiponutrin. Diabetes 55:148–157 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovsan J, Ben-Romano R, Souza SC, Greenberg AS, Rudich A 2007 Regulation of adipocyte lipolysis by degradation of the perilipin protein: nelfinavir enhances lysosome-mediated perilipin proteolysis. J Biol Chem 282:21704–21711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janneh O, Hoggard PG, Tjia JF, Jones SP, Khoo SH, Maher B, Back DJ, Pirmohamed M 2003 Intracellular disposition and metabolic effects of zidovudine, stavudine and four protease inhibitors in cultured adipocytes. Antivir Ther 8:417–426 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhard JM, Furfine ES, Jain RG, Ittoop O, Orband-Miller LA, Blanchard SG, Paulik MA, Weiel JE 2000 HIV protease inhibitors block adipogenesis and increase lipolysis in vitro. Antiviral Res 47:121–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beale EG, Hammer RE, Antoine B, Forest C 2004 Disregulated glyceroneogenesis: PCK1 as a candidate diabetes and obesity gene. Trends Endocrinol Metab 15:129–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarty K, Cassuto H, Reshef L, Hanson RW 2005 Factors that control the tissue-specific transcription of the gene for phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase-C. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 40:129–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huq AH, Lovell RS, Ou CN, Beaudet AL, Craigen WJ 1997 X-linked glycerol kinase deficiency in the mouse leads to growth retardation, altered fat metabolism, autonomous glucocorticoid secretion and neonatal death. Hum Mol Genet 6:1803–1809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olswang Y, Cohen H, Papo O, Cassuto H, Croniger CM, Hakimi P, Tilghman SM, Hanson RW, Reshef L 2002 A mutation in the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ-binding site in the gene for the cytosolic form of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase reduces adipose tissue size and fat content in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:625–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leroyer SN, Tordjman J, Chauvet G, Quette J, Chapron C, Forest C, Antoine B 2006 Rosiglitazone controls fatty acid cycling in human adipose tissue by means of glyceroneogenesis and glycerol phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 281:13141–13149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigem S, Fischer-Posovszky P, Debatin KM, Loizon E, Vidal H, Wabitsch M 2005 The effect of the HIV protease inhibitor ritonavir on proliferation, differentiation, lipogenesis, gene expression and apoptosis of human preadipocytes and adipocytes. Horm Metab Res 37:602–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.