Abstract

Background

The patient centered medical home has received considerable attention as a potential way to improve primary care quality and limit cost growth. Little information exists that systematically compares PCMH pilot projects across the country.

Design

Cross-sectional key-informant interviews.

Participants

Leaders from existing PCMH demonstration projects with external payment reform.

Measurements

We used a semi-structured interview tool with the following domains: project history, organization and participants, practice requirements and selection process, medical home recognition, payment structure, practice transformation, and evaluation design.

Results

A total of 26 demonstrations in 18 states were interviewed. Current demonstrations include over 14,000 physicians caring for nearly 5 million patients. A majority of demonstrations are single payer, and most utilize a three component payment model (traditional fee for service, per person per month fixed payments, and bonus performance payments). The median incremental revenue per physician per year was $22,834 (range $720 to $91,146). Two major practice transformation models were identified—consultative and implementation of the chronic care model. A majority of demonstrations did not have well-developed evaluation plans.

Conclusion

Current PCMH demonstration projects with external payment reform include large numbers of patients and physicians as well as a wide spectrum of implementation models. Key questions exist around the adequacy of current payment mechanisms and evaluation plans as public and policy interest in the PCMH model grows.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11606-010-1262-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: primary care, physician payment, health reform

INTRODUCTION

An emerging consensus exists among providers, payers, and policymakers that primary care has reached a critical crossroads. A volume-oriented fee-for-service reimbursement system with relatively low reimbursement rates when compared to specialists has perpetuated a dysfunctional primary care system that rewards quantity over quality. Primary care physicians (PCPs) report doing more in less time and with worse results1. It is not surprising that few medical students are choosing primary care as a career2, and many older PCPs are retiring earlier than their specialist counterparts3. This deeply flawed system has led to per-capita costs nearly twice that of the next most expensive industrialized country with serious deficiencies in the quality of outpatient care4,5. Continued rising costs threaten the near-term solvency of Medicare and, potentially, the economic competitiveness of US companies.

The patient centered medical home (PCMH) has been touted as a model for delivery system reform that may address many of these market failures and inefficiencies6, and potentially rescue primary care from possible extinction7. Broadly defined, the PCMH envisions accessible, continuous, patient-oriented, team-based, and comprehensive care delivered in the context of a patient’s family and community8. This goal would be achieved through practice transformation supported by external payment reform designed to support the delivery of enhanced primary care services. The 2007 Joint Principles of the PCMH brought together related efforts within each of the major primary care professional societies and has been endorsed by a broad range of supporters including specialty societies and large employers9. Multiple local and regional efforts have begun testing and implementing the PCMH concept in practice, with many of these relying on qualification standards developed by the National Committee on Quality Assurance (NCQA)6.

Great interest in the PCMH persists despite a number of unresolved key issues. Though the Joint Principles set out a broad set of foundational elements9, a common operational definition of what the PCMH entails in practice remains elusive8. Furthermore, while there is supportive evidence for some components of the medical home10, little exists for its ability to improve quality or reduce costs11. Emerging evidence suggests that the transformation toward a medical home model is more laborious and complex than initially envisioned12. Finally, payment models for the PCMH, including payment structure, levels, and timing are varied, and the optimal payment model is unknown. Systematically collected and detailed data on how PCMH demonstrations are organizing and evaluating themselves is scant.

Our goal is to provide detailed information on existing PCMH demonstration projects being implemented throughout the country. We sought to characterize PCMH demonstrations with regards to key design elements that we thought crucial to understanding their potential impact. In order to better our understanding of the results of these demonstration programs, we also sought to characterize the evaluation design and measures.

METHODS

Overview

We collected descriptive information from PCMH demonstrations nationally that were currently active or planned to begin within 2009. Because pilot PCMH projects range from single practices seeking to transform the care they deliver on their own accord to formal multi-practice demonstrations, we focused our efforts on projects that arose external to the participating practices and included payment reform from at least one external payer. We conducted key informant interviews in order to collect detailed information about the history, participants, design, and implementation of each of the programs.

Identifying PCMH Demonstrations

Our literature review identified only three published studies of PCMH demonstrations (Geisinger11, North Carolina Medicaid13, and Group Health14). Next, we examined existing databases of PCMH demonstration programs including compilations available from the Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative (PCPCC)15 and the American College of Physicians16. We supplemented these data with a general Internet search using Google as well as content on other relevant websites (e.g., the Commonwealth Fund). We also contacted experts in the PCMH field to make sure that we were not missing newly-launched projects.

We gathered additional information about each identified program through either Internet searches or phone calls. We included demonstration or pilot projects that: 1) included external payment reform 2) were currently active or were due to start during 2009, and 3) were not restricted to a small proportion of patients being cared for in the practice (e.g., restricted to diabetics) and not solely a primary care case management effort (generally Medicaid-managed care programs that link patients to specific PCPs with pre-defined expectations of increased access, preventive focus, and care coordination roles). Physician organizations implementing the “medical home” without changes in payments from external payers were excluded because 1) external payment reform is a fundamental tenet of the seven joint principles of the medical home9, and more importantly, 2) external payment reform is the lynchpin behind the sustainability of medical home efforts in the future.

Key Informant Interviews

We worked with each demonstration to identify appropriate respondents for the in-depth interviews. This usually included the lead person at the primary convening organization. In many cases, we also conducted separate interviews with the lead investigator of the evaluation team. Interviews took place between March 19th, 2009 and August 11th, 2009. The interviews each lasted approximately 1 hour with follow-up questions through email and by telephone. We sent the completed data tables back to the interviewees to ensure the accuracy of information collected.

We used a structured interview tool that was pilot tested with the evaluator of three of the demonstration projects. Initial questions focused on identifying the impetus and key initial supporters of the project as well as major stakeholders. We also inquired about the requirements, selection process, and characteristics of participating practices, including practice size, information technology resources, and patient/payer mix. The practice requirements section also asked whether the NCQA Physician Practice Connections PCMH (PPC-PCMH) tool was used as a requirement for entry, participation or payment.

We then asked about the base payment methodologies (i.e., capitation, fee-for-service), bonus payments, and the specific formulas used to distribute funds. We also asked about payment timing and uniformity across providers. Practice transformation questions asked about the transformation models utilized, whether transformation was facilitated and, if so, by whom, and specific areas of focus. Finally, the evaluation section dealt with study design, data sources, and the timeline for evaluation. We also asked about the pilots’ methods for data collection and generation of patient samples.

Analysis

The analyses in this study are descriptive. Demonstrations were equally weighted for all analyses.

RESULTS

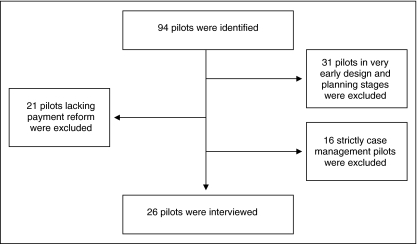

Twenty-six out of the 94 demonstrations identified met the inclusion criteria for our study (Fig. 1). All eligible demonstrations participated in the study. The most common reason for exclusion was that the pilot was still in development (n = 31). In addition, 21 did not include payment reform and 16 were focused on patients with a single disease or were purely case management programs. A list of excluded pilots and the reasons for exclusion is provided in online Appendix 1.

Figure 1.

Selection of participants for the study.

Description of Pilots

The pilots encompass 14,494 physicians in 4,707 practices who care for almost five million patients (Table 1). Five demonstrations (BCBS Michigan, two Pennsylvania projects, SoonerCare Choice Oklahoma, and Community Care of North Carolina) contain 3.7 million of these patients. About two-thirds of the demonstrations were sponsored by a single payer ranging in size from two practices to statewide initiatives including over 2,300 practices. Between 7 and 6,500 physicians participate in each pilot, encompassing between 720 and 1.7 million patients. Payers participating in the demonstrations generally provide coverage for between 30% and 40% of practice patients. Single payer pilots cover an average of 37% of patients in the practice whereas multi-payer pilots cover 55%.

Table 1.

Overview of Current Demonstration Programs

|

| Table 1 Key (abbreviations used are presented in alphabetical order) | ||

|---|---|---|

| AAFP= American Academy of Family Physicians | ACP= American College of Physicians | BCBS= Blue Cross Blue Shield |

| BTE= Bridges to Excellence Medical Home Program | BTS= Breakthrough Series | CCM= Chronic Care Model (Wagner) |

| CHCS= Center for Healthcare Strategy | DM= Disease Management | IBM= International Business Machines Corporation |

| IPA= Independent Practice Association | IPIP= Improving Performance in Practice | IT= Information Technology |

| MH= Medical Home (PCMH) | PCASG= Primary Care Access Stabilization Grant | PCMH= Patient Centered Medical Home |

| P4P= Pay for Performance | PGIP= Physician Group Incentive Program | QI= Quality Improvement |

| RHIO= Regional Health Information Organization | RWJ= Robert Wood Johnson Foundation | |

Many multi-payer initiatives grew out of state convening entities such as a Quality Improvement Organization (QIO) in Rhode Island, a Regional Health Information Organization (RHIO) in New York, or the state governor’s offices (Pennsylvania and Vermont). In contrast, most single payer health plan initiatives emerged as smaller local experiments, in some cases with the help of purchasers such as IBM with UnitedHealth in Arizona. The BCBS Michigan Medical Home project, which grew out of a large physician practice improvement initiative, as well as Community Care of North Carolina and SoonerCare Choice Oklahoma, which emerged from Medicaid case management programs, are statewide exceptions to this observed phenomenon.

Practice Eligibility and Selection

Table 2 shows the practice selection and entry criteria for the demonstrations. Most practice selection involves an open application process, though 42% were pre-selected by the main stakeholders. Practices were included on the basis of whether they were able to meet pre-specified capabilities of medical homes, and also to ensure a broad range of practice types. Nonetheless, only about one-fifth of demonstrations include Community Health Centers. Selection rates varied widely from 19% in the Emblem demonstration to 100% in the Southeastern Pennsylvania demonstration. Only 38% of demonstrations utilize control practices for evaluation and comparison purposes.

Table 2.

Practice Selection

| Name (State) | State | Preselected Practices | Application Process (Accepted/ Applied) | Control Practices | NCQA PPC tool required for entry | Use NCQA PPC tool at any point | IT Required for Entry | Minimum Practice or Panel Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United Health | AZ | No | Yes (7/20) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Colorado Multi-Stakeholder | CO | No | Yes (16/23) | Yes | No (MHIQ) | Yes | No | Yes |

| Wellstar Health System (Humana) | GA | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| New Orleans PCASG | LA | No | Yes (25/39) | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Maine PCMH | ME | No | Yes (26/51) | Yes | No (MHIQ) | Yes | No | Yes |

| Carefirst BCBS | MD | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| BCBS Michigan | MI | No | Yes (1200/2308) | No | No (internal tool) | No | No | No |

| Priority Health | MI | Yes in phase 1; no in phase 2. | No in phase 1; Yes in phase 2. | No. | No; MHIQ for phase 2. | No, but encouraged. | No | No for phase 1; Yes for phase 2. |

| New Hampshire Multi-Stakeholder | NH | No | Yes (11/20) | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Cigna Dartmouth-Hitchcock | NH | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| New York Hudson Valley | NY | No | Yes (N/A) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| CDPHP | NY | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Emblem Health | NY | No | Yes (38/200) | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| BCBS North Carolina | NC | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Community Care of North Carolina | NC | No | Yes (rolling acceptance) | No | No | No | No | No |

| MediQHome (BCBS) | ND | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Greater Cincinnati Aligning Forces | OH | No | Yes (11/25) | No | No (MHIQ) | Yes | No | Yes |

| Cincinnati MH Pilot (Humana) | OH | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| SoonerCare Choice | OK | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| CareOregon | OR | No | Yes (N/A) | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Geisinger | PA | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| SC, SW and NE PA | PA | No | Yes (27/55) | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Yes (27/79) | ||||||||

| Yes (37/63) | ||||||||

| SE PA | PA | No | Yes (34/34) | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| CSI-RI | RI | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| BCBS Tennessee | TN | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| PCMH Vermont | VT | No | Yes (3/6) | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Table 2 Key (abbreviations used are presented in alphabetical order) | ||

|---|---|---|

| BCBS= Blue Cross Blue Shield | CDPHP= Capital District Physician’s Health Plan | CSI-RI= Rhode Island Chronic Disease Sustainability Initiative |

| IT= Information Technology | MHIQ= TransforMED’s Medical Home IQ tool | NCQA= National Committee for Quality Assurance |

| NEPA= Northeastern Pennsylvania | PCMH= Patient Centered Medical Home | PCASG= Primary Care Access Stabilization Grant |

| PPC (or PPC-PCMH)= National Committee for Quality Assurance’s Physician Practice Connections Patient Centered Medical Home tool | SC= South-Central (Pennsylvania) | SE PA= Southeastern Pennsylvania |

| SW= Southwestern (Pennsylvania) | ||

A large majority of demonstrations (81%) require the use of the NCQA PPC-PCMH tool at some point during the demonstration, often as a target level for practice transformation but with 19% requiring a pre-specified level at entry for participation. Three multi-payer demonstrations (Colorado, Greater Cincinnati, and Maine) require the use of the TransforMED Medical Home IQ assessment tool (MHIQ) for entry, and BCBS Michigan PGIP internally devised a medical home measurement tool. Nearly all demonstrations that use the NCQA tool require reaching level 1 as a condition for payment by 12-18 months into the pilot, with a few requiring level 2. None required reaching level 3. Only 12% have any form of IT entry requirements, and 50% have panel or practice size requirements based on the number of eligible patients being treated at the practices.

Payment Arrangements

Almost all pilots include standard FFS payments that are supplemented by per person per month (PPPM) payments for eligible patients (Table 3). The exceptions are one program that used a risk adjusted fixed payment model and a second that included an enhanced fee schedule. PPPM payments range from $0.50 to $9.00, yielding a range from $720 to $91,146 per physician, with a mean of the medians between the high and low ranges of $22,834 of additional revenue per year.

Table 3.

Payment Models

| Payment Model Elements | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Single payer | 69% (17/26) |

| Multi-Payer that have Safe Harbors | 44% (4/9) |

| Use Typical FFS Payments | 96% (25/26) |

| Use Enhanced FFS Payments | 4% (1/26) |

| Use some form of Per Person per Month Payments (PPPM) | 96% (25/26) |

| Range of PPPM Payments | $0.50 to $9.00 |

| Risk- Adjust PPPM Payments | 23% (6/26) |

| Adjust PPPM Payments by NCQA PPC-PCMH Level Attained | 58% (15/26) |

| Range of Marginal Additional PPPM Revenue per MD | $720 to $91,146 |

| (mean =$22,834)* | |

| Additional non-PPPM payments (startup funding, network funding, community grants) | 42% (11/26) |

| Provide Payments Upfront or Start-up Payments | 42% (11/26) |

| Incorporate Bonus Payments (either existing P4P programs or new programs) | 77% (20/26) |

| Table 3 Key (abbreviations used are presented in alphabetical order) | ||

|---|---|---|

| FFS= Fee for Service | NCQA= National Committee for Quality Assurance | P4P= Pay for Performance |

| PPPM= Per Person Per Month | ||

*= represents mean of high and low range of medians

Under anti-trust law, payers are prohibited from working together to develop a uniform payment methodology for reimbursing physician practices. State convening entities can provide legally protected “safe harbors” under which such negotiations can take place. Approximately 44% of the multi-payer initiatives included this safe harbor provision.

A majority of demonstrations use additional bonus payments as well, with most of those payments consisting of previously existing P4P programs, but others that include new P4P bonus systems specific to the pilot. In several cases, the bonus payments have not been worked out. Only a quarter of pilots risk-adjust PPPM payments, and most risk adjustment systems are relatively simple (e.g., age/sex or number of chronic diagnoses). In addition, 60% adjust these payments by NCQA level attained. The experience of the one demonstration that incorporates a more complex clinical risk adjustment formula (Capital District Physicians Health Plan New York) suggests that such models can be challenging to implement. In that case, the health plan waits until the year is complete to retrospectively calculate the risk adjusted fixed payment amount for attributed patients. Thus, the practices are not certain of the budget constraint that they are working within.

More than 40% of demonstrations also include additional payments outside of fixed monthly payment arrangements. For example, the Rhode Island and Tennessee demonstrations include payments for embedded nurse care managers and licensed practical nurses within practices, respectively. Other pilots such as Community Care of North Carolina leverage local networks for supporting practices in areas such as care coordination and quality improvement, and include network PPPM contributions to sustain these entities. PCMH Vermont includes payments to community entities for support of population-based health management.

Practice Transformation

Most demonstrations utilize either a consultative model or rely on implementation of the chronic care model to drive the transformation process (Table 4 and online Appendices 2 and 3). The majority of demonstrations using either model also employ learning collaboratives. For example, the BCBS Michigan demonstration utilizes a series of learning collaboratives throughout the state to promote transformation, with a specific focus on Lean methodologies such as value stream mapping of care processes. The consultative models employ external consultants who analyze and then advise practices on the changes they must implement to become a functioning medical home. Practice consultants generally utilize their own normative models that identify operational aspects of a well functioning medical home and then work with the practices to implement change. Consultant to practice ratios varied from approximately 2 to 20 practices per consultant. A number of mostly single payer pilots do not use a defined transformation model.

Table 4.

Transformation

| Transformation Model | Use of Facilitator | New Personnel | Focus of Improvement | EMR and Registry Use* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consultative: 35% | Internal: 27% | On-site: 42% | General: 46% | EMR: 69% |

| External: 42% | Shared: 8% | Disease-specific (e.g., DM, CHF, Asthma): 54% | Registry: 81% | |

| Chronic care model-based learning collabrative: 23% | None: 31% | None: 50% | Neither are required nor encouraged: 8% | |

| Combination: 15% | ||||

| Any type of learning collaborative: 69% | ||||

| None: 27% | ||||

| Table 4 Key (abbreviations used are presented in alphabetical order) | ||

|---|---|---|

| CCM= Chronic Care Model (Wagner) | CHF= Congestive Heart Failure | DM= Diabetes Mellitus |

| EMR= Electronic Medical Record | IHI= Institute for Healthcare Improvement | |

*= Use of either tool is required or already adopted by most practices

Upfront transformation funding was available for over half of practices, ranging from small lump sum payments of $1000–$6000 per practice to grants totaling over $100,000 to support infrastructure investments. Almost all demonstrations paid the fees for the NCQA tool, though not the time and labor involved. Chronic diseases such as asthma and diabetes are the most common foci of specific transformation programs, especially among chronic care model practices. Many consultative model demonstrations also focus on these populations in addition to whole practice transformation.

Evaluation

Although all of the demonstrations will conduct an evaluation, the evaluation plan for nearly 60% of demonstrations had not yet been devised in detail at the time of the interviews. Even among those with more developed plans, the specification of which variables would be measured, along with surveys to be used, was uncommon. Those who have an evaluation plan in place are generally focused on cost plateau or reduction (as measured through claims), decreases in hospitalizations and emergency room visits, processes of care and quality outcome measures for chronic diseases, and patient experience measures. Most employ a pre-post design, with 38% planning comparisons to control practices. Peer-reviewed evaluations for two of the included programs (CCNC and Geisinger) suggest overall cost savings, but these reports should be considered preliminary11,13.

DISCUSSION

We provide detailed information on the structure, payment models, and transformation processes of the extant PCMH demonstration projects across the country. There is substantial diversity in not only the size and scope of current PCMH demonstration projects, but also in the design and conceptualization of the pilots. This diversity should be useful in providing insights into the design elements that are most crucial to facilitating the broader adoption of the PCMH model of primary care.

A number of key findings emerge from this study. First, we identified a large number of current and planned pilots, including 26 currently active demonstrations with payment reform in 18 states, as well as at least 68 demonstrations in 25 states planned for launch in the future. Current demonstrations include over 14,000 physicians caring for nearly 5 million patients. Undoubtedly there are additional projects that we failed to identify. These numbers suggest substantial enthusiasm for the PCMH model of care from diverse stakeholders throughout the country.

Second, the PCMH did not arise in a vacuum. Many of these projects are natural extensions of health plan or area-wide quality improvement initiatives. Thus, many of the demonstrations build upon an infrastructure of teamwork and shared resources that may be difficult to replicate when implementing the PCMH on a larger scale. Finally, we found substantial variability related to the basic requirements and definition of a PCMH, optimal payment methods, and methods for facilitating the transformation of existing primary care practices to highly functioning patient-centered medical homes.

Even in the presence of external payment reform, the PCMH pilots’ chances of achieving positive results hinge upon successful transformation, particularly given the relatively short time periods specified in many of the demonstrations (usually about two years). We identified two core models for helping practices transform themselves to a PCMH—implementation of the chronic care model supported by quality improvement coaching, and a model featuring external transformation consultants. The CCM identifies aspects of care systems that must be addressed to lead to significant improvements in chronic disease care. As applied to practice transformation, it provides guidance to practices on the types of initiatives they should undertake, working collaboratively with other practices within a learning collaborative. A plurality of pilots surveyed used this model of change and most of these did not use external consultants. In contrast, the consultative model of transformation involved proscriptive practice change most often carried out by external facilitators hired by the pilot who help to organize assessment and transformation around core modules. This model requires substantial additional up-front resources to support these facilitators.

Whether either of these models will be sufficient to support practice transformation on a large scale is not known. Prior research on implementation of the CCM through quality improvement collaboratives suggests that practices can achieve modest improvement in processes of care, but little definitive change in outcomes or cost savings have been observed17–22. Similarly, practices participating in the recently completed TransforMED national demonstration project found it challenging to achieve transformative care changes12. This suggests that transformation is difficult to achieve12,23,24. One key distinction is that these studies all occurred in the absence of external payment reform; the extent to which payment reform will serve as an enabler of practice transformation is a key issue to be answered by current pilots.

External payment reform is a cornerstone principle of the PCMH, and how individual health plans and demonstration projects structure payments is likely to be among the most important determinants of success. Most of the demonstrations adopt the “three part” payment model espoused by the PCPCC. This model includes ongoing fee-for-service payments, a fixed (usually monthly) case management fee, and potential for additional bonuses based on clinical performance. Across the demonstrations, however, we found a large range of additional revenue potential ranging from approximately $1000 to over $90,000 per physician per year, with most of the incremental revenue coming from the fixed case management fees. Many, but not all, of the demonstrations not only maintain FFS payment at existing levels, but still utilize it as their core payment system. In addition, participating health plans base payments on their own enrollees, and few of the projects attempt to add sufficient additional resources to cover costs for the entire practice. The timing of the payments might also play a significant role. Several of the demonstration projects include up-front payments that can be used to support investments needed for transformation that might be otherwise difficult to finance with incremental monthly or quarterly revenue.

Finally, we note that the NCQA PPC-PCMH tool has emerged as the de facto, if partially flawed25, method for evaluation of “medical homeness.” Some pilots view NCQA certification as a desired outcome and base their payment structure on achieving pre-specified levels. Others view such certification as a starting point, recognizing that the tool defines a baseline set of core capabilities but does not capture all of the key aspects required of a fully functioning medical home. Still other demonstrations use it as an external benchmark to inform practice transformation. How well outcomes correlate to NCQA level, and what consequences (intended and otherwise) emerge from tying payment to NCQA levels are questions deserving future empiric study.

Our findings yield several important implications for policy, practice, and research. The heterogeneity in program design suggests an urgent need to incorporate evaluation in all programs’ designs. Less than half of the programs had well-specified evaluation plans that were designed in conjunction with the pilot. In most cases, although evaluation is considered important, the evaluation designs had not been pre-specified, thus necessitating a reliance on existing data, and funding had not been secured to support a robust evaluation. Furthermore, many of the pilots do not identify adequate control groups against which to compare the intervention practices.

Program evaluation should look broadly at the impact on service cost/utilization; quality of care as measured by patient experiences, processes, and outcomes; and physician/staff experiences. If physician experiences are not improved within the medical home, the future may yield few PCPs to provide care under this model. An evaluator collaborative funded by the Commonwealth Fund is also working to develop uniform methods for measurement in each of these areas that will facilitate comparisons across pilots. Finally, we must be clear about the implications of the medical home on costs and cost growth. It is likely that implementing the medical home will not lead to immediate direct cost savings because of the initial increase in resources needed to implement this model. There is hope that the PCMH will impact the rate of cost growth in the future if it leads to a more rational model of care.

The PCMH model has captured the attention of providers, payers, purchasers, and policymakers nationwide, resulting in the development of numerous demonstration programs throughout the country. In addition, the PCMH is being looked at as a means of reorganizing care under current health reform proposals. The diversity in the design of the pilots suggests that significant unanswered questions remain about how the PCMH model should be implemented. Whether the PCMH model delivers on its promise of better quality and patient experience at lower costs will be in large part determined by how demonstrations address core questions around transformation, payment policy, medical home certification, and the adequacy of their evaluation plans.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Excluded Demonstration Projects (DOC 105 kb)

Transformation Part I (DOC 89 kb)

Transformation Part II (DOC 88 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all of the survey respondents for their willingness to participate in the study. This study was funded in part by grants from the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality, the Commonwealth Fund, and The American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation. Dr. Bitton is supported by grant number T32HP10251 from the Health Resources and Services Administration of the Department of Health and Human Services to support the Harvard Medical School Fellowship in General Medicine and Primary Care. The study contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Department of Health and Human Services.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

References

- 1.Bodenheimer T, Grumbach K, Berenson RA. A lifeline for primary care. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(26):2693–2696. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0902909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hauer KE, et al. Factors associated with medical students’ career choices regarding internal medicine. Jama. 2008;300(10):1154–1164. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.10.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lipner RS, et al. Who is maintaining certification in internal medicine–and why? A national survey 10 years after initial certification. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(1):29–36. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-1-200601030-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGlynn EA, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(26):2635–2645. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa022615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ginsburg JA, et al. Achieving a high-performance health care system with universal access: what the United States can learn from other countries. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(1):55–75. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-1-200801010-00196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rittenhouse DR, Shortell SM. The patient-centered medical home: will it stand the test of health reform? Jama. 2009;301(19):2038–2040. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fisher ES. Building a medical neighborhood for the medical home. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(12):1202–1205. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0806233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berenson RA, et al. A house is not a home: keeping patients at the center of practice redesign. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(5):1219–1230. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.5.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) et al. Joint principles of the patient-centered medical home. 2007 [cited November 20th, 2009]; Available from: http://www.acponline.org/running_practice/pcmh/demonstrations/jointprinc_05_17.pdf.

- 10.Rosenthal TC. The medical home: growing evidence to support a new approach to primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008;21(5):427–440. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2008.05.070287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paulus RA, Davis K, Steele GD. Continuous innovation in health care: implications of the Geisinger experience. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(5):1235–1245. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.5.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nutting PA, et al. Initial lessons from the first national demonstration project on practice transformation to a patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(3):254–260. doi: 10.1370/afm.1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steiner BD, et al. Community care of North Carolina: improving care through community health networks. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(4):361–367. doi: 10.1370/afm.866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reid R, et al. Patient-centered medical home demonstration: a prospective, quasi-experimental, before and after evaluation. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15(9):e71–e89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.PCPCC. Patient centered medical home: building evidence and momentum. 2009 [cited June 5, 2009]; Available from: http://www.pcpcc.net/content/pcpcc_pilot_report.pdf.

- 16.ACP. Patient centered medical home. 2009 [cited June 5, 2009]; Available from: http://www.acponline.org/running_practice/pcmh/.

- 17.Chin MH, et al. Improving and sustaining diabetes care in community health centers with the health disparities collaboratives. Med Care. 2007;45(12):1135–1143. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31812da80e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coleman K, et al. Evidence on the chronic care model in the new millennium. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(1):75–85. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Homer CJ, et al. Impact of a quality improvement program on care and outcomes for children with asthma. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(5):464–469. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.5.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landon BE, et al. Improving the management of chronic disease at community health centers. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(9):921–934. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa062860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mangione-Smith R, et al. Measuring the effectiveness of a collaborative for quality improvement in pediatric asthma care: does implementing the chronic care model improve processes and outcomes of care? Ambul Pediatr. 2005;5(2):75–82. doi: 10.1367/A04-106R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vargas RB, et al. Can a chronic care model collaborative reduce heart disease risk in patients with diabetes? J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(2):215–222. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0072-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hroscikoski MC, et al. Challenges of change: a qualitative study of chronic care model implementation. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4(4):317–326. doi: 10.1370/afm.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Solberg LI, et al. Transforming medical care: case study of an exemplary, small medical group. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4(2):109–116. doi: 10.1370/afm.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuzel AJ, Skoch EM. Achieving a patient-centered medical home as determined by the NCQA–at what cost, and to what purpose? Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(1):85–86. doi: 10.1370/afm.956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Excluded Demonstration Projects (DOC 105 kb)

Transformation Part I (DOC 89 kb)

Transformation Part II (DOC 88 kb)