Abstract

Background

Persistent, activity-limiting pain after laparoscopic ventral or incisional hernia repair (LVIHR) appears to be related to fixation of the implanted mesh. A randomized study comparing commonly used fixation techniques with respect to postoperative pain and quality of life has not previously been reported.

Methods

A total of 199 patients undergoing non-urgent LVIHR in our unit between August 2005 and July 2008 were randomly assigned to one of three mesh-fixation groups: absorbable sutures (AS) with tacks; double crown (DC), which involved two circles of tacks and no sutures; and nonabsorbable sutures (NS) with tacks. All operations were performed by one of two experienced surgeons, who used a standardized technique and the same type of mesh and mesh-fixation materials. The severity of the patients’ pain was assessed preoperatively and at 2 weeks, 6 weeks and 3 months postoperatively by using a visual analogue scale (VAS). Quality of life (QoL) was evaluated by administering a standard health survey before and 3 months after surgery. Results in the three groups were compared.

Results

The AS, DC, and NS mesh-fixation groups had similar patient demographic, hernia and operative characteristics. There were no significant differences among the groups in VAS scores at any assessment time or in the change in VAS score from preoperative to postoperative evaluations. The QoL survey data showed a significant difference among groups for only two of the eight health areas analyzed.

Conclusion

In this trial, the three mesh-fixation methods were associated with similar postoperative pain and QoL findings. These results suggest that none of the techniques can be considered to have a pain-reduction advantage over the others. Development of new methods for securing the mesh may be required to decrease the rate or severity of pain after LVIHR.

Keywords: Incisional hernia, Ventral hernia, Laparoscopic surgery, Pain, Quality of life, Mesh fixation

Laparoscopic ventral and incisional hernia repair (LVIHR) continues to increase in popularity because of its low rates of complications and hernia recurrence and short hospitalization and recovery times [1–3]. Reported rates of recurrence after LVIHR have been as low as 2% or 3% [4, 5], but patients who undergo LVIHR tend to have more pain in the early postoperative period than after any other minimally invasive operation [6–8]. As a result, LVIHR usually cannot be performed as a day-case procedure. Pain after LVIHR is usually self-limiting, but it persists for more than 2 weeks in up to one-quarter of patients [9, 10]. Moreover, some patients experience chronic pain, which is usually defined as pain lasting longer than 8 weeks [6, 11, 12]. These observations have shifted more research attention to this aspect of the procedure.

The occurrence of postoperative pain in patients who have undergone LVIHR has been ascribed to mesh fixation and the use of transabdominal sutures (TAS) [13], metal fixation devices (e.g. tacks) or both [14]. Currently, two methods of mesh fixation are commonly employed. One involves placement of both TAS, either absorbable or nonabsorbable, and tacks; the other entails insertion of two circles of tacks without TAS [the double-crown (DC) technique] [15]. To our knowledge, no randomized trial has previously compared the nonabsorbable TAS (NS), DC, and absorbable TAS (AS) mesh-fixation techniques with respect to pain and quality of life (QoL) as specific outcomes of LVIHR. We therefore conducted a randomized investigation with the aim of determining whether pain and QoL after LVIHR varied according to the type of mesh fixation (NS, DC or AS) performed during surgery.

Methods

Patients

The protocol for this study was approved by the ethics committee of Medisch Spectrum Twente (Enschede, The Netherlands) and the local ethics committee. Patients between 18 and 80 years old who required non-urgent surgery for an incisional or ventral hernia between August 2005 and July 2008 were considered for enrollment. Patients with chronic cough, ascites, active abdominal infection or complete loss of abdominal domain due to hernia were excluded from the study, as were those receiving peritoneal dialysis or more than 15 mg prednisone per day and those who had previously undergone LVIHR. All patients enrolled in the trial provided informed consent to participate.

Operative techniques

All patients were given low-molecular-weight heparin subcutaneously to provide prophylaxis for thrombosis, and all were placed under general anaesthesia for operation. In all cases, LVIHR was done by one of two surgeons who had performed more than 100 such procedures before the study began.

Pneumoperitoneum was obtained by using either Veress needle or an open technique [16]. A 30° camera was inserted through a 10-mm trocar. Other trocars were inserted under direct visual. When necessary, adhesiolysis was performed, the hernia was exposed, and the surrounding area prepared for mesh placement. All patients were given a 1-mm-thick expanded polytetrafluoroethylene mesh (DualMesh; WL Gore & Associates, Flagstaff, AZ, USA), tailored to overlap all hernia margins by at least 3 cm. No attempt was made to reapproximate the edges of the hernia opening.

The method of mesh fixation for each patient was determined by means of computerized random generation of a number just before the operation. The number was given to the surgeon, who then used the mesh-fixation technique previously assigned to that number. Patients were not routinely told which method had been used in their procedure, but this information was not withheld when a patient specifically requested it.

In patients randomly assigned to the AS mesh-fixation group, titanium helical tacks (ProTack; TycoUSS, Norwalk, CT, USA) were placed approximately 5 mm inside the edge of the mesh along its entire perimeter, about 1.5–2.0 cm apart. Absorbable TAS (Vicryl; Ethicon, Norderstedt, Germany) were then inserted every 4–5 cm by using a Gore Suture Passer (WL Gore & Associates). Each of the TAS encompassed 0.5–1 cm of tissue. The TAS were tied down with care taken to avoid knotting the thread too tightly, and all knots were buried in the subcutaneous tissue. In the NS group, the mesh-fixation technique was the same as that used in the AS group, except that the TAS were made of a nonabsorbable material (Mersilene; Ethicon, Norderstedt, Germany). In patients in the DC group, one circle of titanium helical tacks was placed in the same position as in the patients in the AS mesh-fixation group and another circle was placed inside that circle, around the hernia opening. The tacks in the inner circle were spaced about 1.0–1.5 cm apart. No TAS were inserted.

After fixation of the mesh, the trocars were removed and the pneumoperitoneum was released. Fascial closure was done at all trocar sites that were 10 mm in diameter or larger. No special bandages were applied. Immediately after the operation, the surgeon completed a detailed report on patient, hernia and operative characteristics.

All patients received standard postoperative care, including mobilization and return to normal diet as quickly as possible. Patient-controlled analgesia (morphine) was provided for the first 24 h after surgery. Even patients with minimal pain or discomfort were given acetaminophen (1 g four times daily) and a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent (ibuprofen; 600 mg three times daily) for at least 3 days. The study protocol allowed administration of additional opioid and nonopioid analgesic agents if necessary.

Clinical follow-up

All patients were scheduled to return for an outpatient visit 2 weeks, 6 weeks and 3 months after surgery. The primary outcome measure in the study was the presence and severity of postoperative pain as determined by scores on a visual analogue scale (VAS; range 0–100) obtained preoperatively (baseline) and during the outpatient visits. The study also assessed QoL by means of administration of the RAND 36-item Short-Form Health Survey 1.0 (SF-36) preoperatively and at the 3-month follow-up visit.

The abdominal wall was examined at all outpatient visits. Patients in whom pain impairing daily activities persisted for more than 6 weeks or in whom hernia recurrence was suspected underwent ultrasonography or computed tomography. Prolonged postoperative pain was treated with oral analgesic agents and, in cases in which painful sites were well defined, local infiltration of analgesic. Postoperative complications were scored according to the classification system described by Dindo et al. [17]. Seromas and haematomas were considered complications when they limited daily activities or required drainage. Hernia recurrences were recorded but were not analyzed in this short-term study.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed by using SPSS version 15 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) for Windows. Results in the three mesh-fixation groups were compared by performing analysis of variance or Kruskal–Wallis tests (continuous variables) and chi-square or Fisher exact tests (categorical variables). When a significant difference in continuous, normally distributed variables was found, post hoc testing was done with Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD)test. A p value of < 0.05 was considered to represent statistical significance.

An a priori power analysis was performed with the following assumptions: alpha = 0.05, power = 80%, with a difference between groups of 8 in the change in VAS scores from baseline to the postoperative period considered clinically relevant. The estimated standard deviation (SD)for the change from baseline values was 15. Under these assumptions, we calculated that 56 patients per group were required.

Results

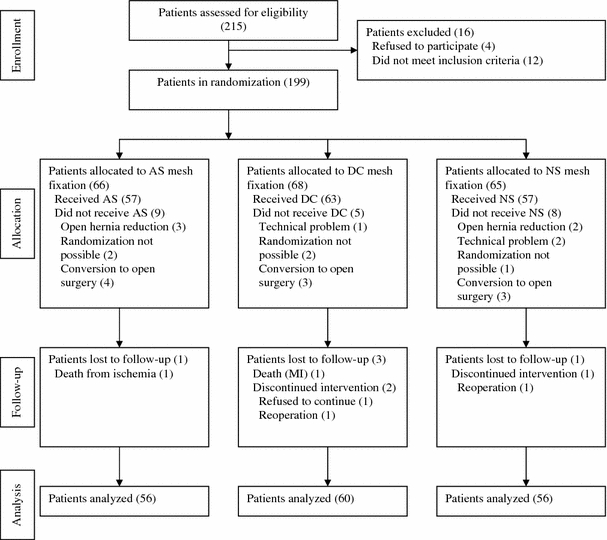

A total of 199 patients met the inclusion criteria and were initially randomly assigned to one of the three mesh-fixation groups. Twenty-seven of the 199 patients were subsequently excluded from the study for various reasons or were lost to follow-up. Thus, 172 entered the analysis phase of the trial (Fig. 1). Complete VAS scores were available for 143 patients (83%), and 3-month postoperative SF-36 forms were obtained from 137 patients (80%).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of participants’ progress through the randomized study comparing three methods of mesh fixation during laparoscopic ventral or incisional hernia repair. Values in parentheses are numbers of patients. AS absorbable sutures, DC double-crown method, NS nonabsorbable sutures, MI myocardial infarction

The AS, DC and NS mesh-fixation groups had similar patient demographic and hernia characteristics (Table 1). Moreover, there were no significant differences among the three groups in conversions to open surgery, mesh or hernia size, numbers of trocars used or length of postoperative hospital stay (Table 2). On post hoc analysis, operating time was significantly shorter in the DC group compared with the AS group (p = 0.03) and somewhat shorter in the DC group than in the NS group (p = 0.24). Because the DC mesh-fixation method uses an extra circle of tacks, repairs in which this technique was employed required significantly more tacks than were necessary in either AS or NS procedures. AS and NS mesh fixation required about the same number of TAS.

Table 1.

Patient demographic and hernia characteristics, according to mesh-fixation group

| Characteristic | Mesh-fixation group | Overall (n = 172) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS (n = 56) | DC (n = 60) | NS (n = 56) | ||

| Mean (±SD) age in years | 54.7 (12.9) | 51.6 (13.8) | 52.4 (12.7) | 52.9 (13.2) |

| Sex: M/F | 39/17 | 33/27 | 36/20 | 108/64 |

| Mean (± SD) BMI (kg/m2) | 29.1 (4.9) | 28.7 (5.4) | 29.9 (5.7) | 29.2 (5.3) |

| ASA class (no. of patients)a | ||||

| 1 | 25 | 37 | 23 | 85 |

| 2 | 23 | 16 | 27 | 66 |

| 3 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 16 |

| IH (% of patients) | 35.7 | 35 | 30.4 | 33.7 |

| Recurrent IH (% of patients)b | 10 | 10 | 11.1 | 10.7 |

AS absorbable sutures, DC double crown, NS nonabsorbable sutures, BMI body mass index, ASA American Society of Anesthesiologists, IH incisional hernia

aASA class was not reported for all patients

bAll in patients in whom the initial hernia was treated with an open surgical procedure

Table 2.

Operative and postoperative characteristics, according to mesh-fixation groupa

| Characteristic | Mesh-fixation group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS | DC | NS | Overall | p-Valueb | |

| No. (%) conversions to open surgery | 4 (7) | 3 (5) | 3 (5) | 10 (6) | — |

| Mesh size (cm2) | 233.9 (154.2) | 223.5 (149.7) | 201.4 (126.6) | 219.7 (144) | 0.75 |

| Hernia size (cm2) | 23.4 (61.5) | 22.5 (56.1) | 11.3 (29.6) | 19.2 (51.2) | 0.88 |

| No. of tacks | 41.3 (14.4) | 55.6 (22.4) | 35.9 (11.5) | 44.5 (18.8) | <0.001 |

| No. of sutures | 8.8 (3.2) | NA | 8.8 (2.6) | 8.8 (2.9) | 0.97 |

| No. of trocars | 3.1 (0.4) | 3.1 (0.5) | 3 (0.1) | 3.1 (0.4) | 0.32 |

| Operating time (min) | 60.3 (23.4) | 46.8 (22.9) | 53.4 (18.9) | 53.3 (22.4) | 0.005 |

| Postoperative stay (days) | 2.1 (2.2) | 1.7 (1.3) | 1.9 (1.3) | 1.9 (1.6) | 0.57 |

AS absorbable sutures, DC double crown, NS nonabsorbable sutures, NA not applicable

aValues are mean (± SD) unless otherwise indicated

bFor differences among the three groups

Mean VAS pain scores in each of the three mesh-fixation groups at the preoperative and three postoperative assessment times, as well as the change in scores from the preoperative to the postoperative period at 3 months, are shown in Table 3. The scores in the three groups were similar at all times, as was the extent of change in scores. A separate analysis of the VAS scores in the DC group found no significant correlation between the number of tacks used and postoperative pain (correlation coefficient 0.20; p = 0.14). Because the number of TAS used was predominantly eight, no statistical analysis could be performed on the relation between TAS and postoperative pain.

Table 3.

VAS scores for pain at various assessment times, according to mesh-fixation groupa

| Assessment time | Mesh-fixation group | p-Valueb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS | DC | NS | ||

| Preoperative | 21.1 (20.7) | 20.5 (23.6) | 26.4 (27.8) | 0.43 |

| 2 weeks postoperative | 15.8 (15.6) | 16.3 (20.8) | 20.7 (21.8) | 0.38 |

| 6 weeks postoperative | 6.2 (10.2) | 8.6 (19.6) | 8.8 (16.4) | 0.76 |

| 3 months postoperative | 4.5 (10.5) | 5.8 (12.5) | 11.2 (21.2) | 0.41 |

| Postoperative score minus preoperative scorec | –17.3 (–23.6 to –11) | –14.7 (–22.2 to –7.3) | –15.9 (–25 to –6.7) | 0.9 |

VAS visual analogue scale, AS absorbable sutures, DC double crown, NS nonabsorbable sutures

aValues are mean (± SD), except for postoperative minus preoperative score, for which mean (95% confidence interval) is shown

bFor differences among the three groups

cPostoperative score at 3 months minus preoperative score was used

QoL scores derived from the SF-36 survey are shown in Table 4. Post hoc analysis revealed a significant difference between the AS and DC groups in physical functioning measures (p = 0.017) and between the AS and NS groups in measures of role limitations due to emotional problems (p = 0.021). For both of these QoL indicators, patients in the AS group had better outcomes after LVIHR.

Table 4.

Postoperative scores (3 months after surgery) minus preoperative scores for the eight health concepts on the SF 36-item Short-Form Health Survey, according to mesh-fixation groupa

| Health concept | Mesh-fixation group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS | DC | NS | p-Value | |

| Physical functioning | 13.5 (6.5 to 20.5) | 2.4 (–3.2 to 7.9) | 9.2 (4.5 to 13.9) | 0.021 |

| Role limitations due to physical problems | 8.6 (–5.2 to 22.4) | 10.8 (–2.1 to 23.8) | 9.2 (–1.5 to 19.9) | 0.97 |

| Role limitations due to emotional problems | 13.2 (–1.6 to 28) | –8.3 (–19.3 to 2.6) | –11.7 (–25.1 to 1.7) | 0.017 |

| Energy/fatigue | 3.2 (–6 to 12.4) | –2 (–7.9 to 3.9) | –3.4 (–7 to 0.2) | 0.32 |

| Emotional well-being | 3.4 (–3.2 to 9.9) | 0.6 (–4 to 5.2) | 1 (–3.2 to 5.2) | 0.71 |

| Social functioning | 8.9 (–0.6 to 18.3) | 1.4 (–5.3 to 8.1) | –2.4 (–8.9 to 4.1) | 0.1 |

| Pain | 20.7 (11.2 to 30.2) | 14.9 (7.8 to 22) | 9.6 (2.5 to 16.7) | 0.14 |

| General health | –15.7 (–23.2 to –8.2) | –13.5 (–18.5 to –8.5) | –13.4 (–18.7 to –8.2) | 0.83 |

AS absorbable sutures, DC double crown, NS nonabsorbable sutures

aValues are mean (95% confidence interval)

Table 5 shows the postoperative complications in the study. The patient who was readmitted to hospital after surgery required help in performing activities of daily living. Five patients in the study (one each in the AS and DC groups and three in the NS group) required reoperation for chronic pain that did not resolve with conservative treatment. There was no significant difference in reoperation rate for chronic pain between the three groups (p = 0.41). These patients underwent either removal of the TAS used to affix the mesh (n = 2) or removal of the entire mesh and insertion of a new mesh (n = 3). Two of the patients with mesh removal and one with TAS removal became symptom free. The two other patients, one with non-absorbable sutures and one with double-crown fixation, remain with pain symptoms.

Table 5.

Complications of surgery and Dindo complication grade, according to mesh-fixation groupa

| Complication | Mesh-fixation group | No. (%) of all patientsb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS | DC | NS | ||

| Urinary retention | 3 | 2 | 1 | 6 (3.5) |

| Prolonged ileus | 1 | – | 1 | 2 (1.2) |

| Readmission to hospital | 1 | – | – | 1 (0.6) |

| Seroma | 1 | – | – | 1 (0.6) |

| Hematoma | 3 | 3 | 1 | 7 (4.1) |

| Bulging | 1 | – | 1 | 2 (1.2) |

| Pain requiring reoperation | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 (2.9) |

| Trocar hernia | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 (1.7) |

| Hernia recurrence | 1 | 1 | – | 2 (1.2) |

| Dindo gradec | ||||

| 1 | 9 | 5 | 4 | 18 (10.5) |

| 3b | 4 | 3 | 4 | 11 (6.4) |

AS absorbable sutures, DC double crown, NS nonabsorbable sutures

aValues are numbers of patients unless otherwise indicated

bTwenty-nine complications were observed in the study (complication rate, 16.9%), with 13, 8 and 8 complications, respectively, in the AS, DC and NS groups

cGrade 1: Any deviation from the normal postoperative course without the need for pharmacological treatment or surgical, endoscopic, and radiological interventions; grade 3b: Intervention under general anaesthesia

During the 3-month follow-up period in the study, no patient had hernia recurrence. Subsequently, there were two recurrences, one in the AS group and one in the DC group (p = 1.0).

Discussion

Secure fixation of the mesh and adequate overlap of all hernia margins with the prosthetic material are crucial to the success of LVIHR. The two most widely used mesh-fixation methods (the NS and DC techniques) in LVIHR provide reliable results with similarly low recurrence rates [1, 18]. However, fixation of the mesh to the abdominal wall also appears to be the most important source of postoperative pain. The importance of this problem was indicated by the recent study of Eriksen et al., who found that LVIHR was associated with considerable postoperative pain and fatigue in the first month after surgery and had significant effects on patients’ QoL for up to 6 months postoperatively [8].

As is the case with mesh repair of inguinal hernias, an increasing number of clinicians and researchers now consider postoperative pain, rather than recurrence, the most important adverse effect of LVIHR.

Because pain after LVIHR is frequently associated with movement and a pulling sensation at the site of TAS placement, most authors think that the pain is caused by the TAS [9, 13]. The finding that injections of local anaesthetics at TAS sites frequently result in pain resolution [9] supports this assumption. However, Carbajo et al. [12] reported a high rate of persistent pain (7.4%) after LVIHR procedures in which two circles of tacks alone (no TAS) were used to secure the mesh. Bageacu et al. [10] observed severe pain in patients in whom tacks were used in laparoscopic repair of incisional hernias. We previously found that removal of TAS implicated in the development of chronic pain after LVIHR does not always relieve the pain [14]. These and other findings indicate that TAS are not the only cause of pain after LVIHR, but that tacks may play an important role. Both a review by LeBlanc [18] and a case-controlled study by Nguyen et al. [19] suggested that TAS fixation and tack fixation are equally likely to be associated with postoperative pain, but this hypothesis has not previously been investigated in a randomized trial.

The aim of the current randomized trial was to provide more reliable data on the relation between pain after LVIHR and the method used to fix the mesh. The study found no significant differences among three mesh-fixation techniques with respect to VAS pain scores at 2 weeks, 4 weeks or 3 months after surgery. The only significant difference among the groups was that operating time was shorter in the DC group compared with the AS group, probably because it takes longer to place TAS around the perimeter of the mesh than to insert a second circle of tacks [20]. Our results indicate that the most commonly used methods to secure the mesh during LVIHR have a similar association with postoperative pain and that none of these techniques can be considered to have a pain-reduction advantage over the others.

The QoL assessments in the study found that, compared with preoperative status, patients in all three mesh-fixation groups had improvements in QoL by 3 months after LVIHR. In addition, only minimal intergroup differences in postoperative QoL measures were observed.

It is possible that the use of DC and NS mesh fixation in LVIHR provides mesh fixation that is more secure than is necessary to prevent recurrence, while increasing the risk of postoperative pain. Therefore, in this study, we also included a group of patients in whom absorbable TAS were employed to affix the mesh, speculating that, if postoperative pain is due to the presence of a permanent mesh-fixation device, the potential for such pain might decrease over time in patients in whom an absorbable material is used instead. We found, however, that for the first 3 months after LVIHR (long after the point at which absorbable TAS would have been retained), pain scores in the AS mesh-fixation group were not significantly different from those in either the NS or DC group. These results are similar to those in a previous study that failed to detect any significant difference between mesh fixation using absorbable TAS and fixation using nonabsorbable TAS with regard to postoperative pain after Lichtenstein inguinal hernia repair [21]. Interestingly, the absence of a correlation between the number of tacks used and postoperative pain in the current trial may indicate that pain after LVIHR is generated according to some “threshold” principle, rather than being due to a cumulative effect from many fixation points.

To minimize systematic and random errors, we analyzed only two outcomes: postoperative pain and QoL. To reduce the number of prognostic variables, the same type of mesh, tacks and nonabsorbable or absorbable TAS were used in all operative procedures, which were performed by one of two experienced surgeons, who used a standardized technique. This protocol made introduction of performance bias unlikely.

Certain modifications to the LVIHR procedure have potential to influence the severity of postoperative pain. For example, closing the hernia defect before placement of the mesh has been proposed. However, most surgeons (including us) do not close the defect. Probably they assume, as we do, that the resulting traction may contribute to the onset or severity of postoperative pain. Moreover, in two large case series in which defect closure was performed, the rates of chronic pain (2.5% [22] and 3.1% [4], respectively) were similar to those in major studies in which closure was not done.

Some recent research has focused on new, possibly less pain-inducing, mesh-fixation techniques. Olmi et al. [23] observed a low rate of postoperative pain (assessed with VAS scoring) in a series of 40 patients in whom fibrin glue was used to fix the mesh during laparoscopic repair of small and medium-sized abdominal wall defects. In a randomized controlled trial in pigs, Eriksen et al. [24] showed that laparoscopic intraperitoneal fixation of mesh with fibrin sealant was technically feasible and safe. Substantial additional research is required to ascertain whether the use of such techniques will decrease the rate or severity of pain after LVIHR while resulting in the same low recurrence rate.

Conclusions

In a randomized study that compared methods for securing the mesh during LVIHR, the AS, DC and NS techniques were associated with similar postoperative pain and QoL findings. These results suggest that none of the techniques can be considered to have a pain-reduction advantage over the others. Development of new mesh-fixation methods may be required to address the issue of pain after LVIHR.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Renée J. Robillard for editorial assistance and Hilda Rijnhart–de Jong for data analysis of QoL scores. WL Gore & Associates, Flagstaff, AZ, provided financial support for preparation of the manuscript. ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT00537927

Disclosures

Eelco Wassenaar, Ernst Schoenmaeckers, Johan Raymakers, Job van der Palen, and Srdjan Rakic have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Rudmik LR, Schieman C, Dixon E, Debru E. Laparoscopic incisional hernia repair: a review of the literature. Hernia. 2006;10:110–119. doi: 10.1007/s10029-006-0066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sajid MS, Bokhari SA, Mallick AS, Cheek E, Baig MK. Laparoscopic versus open repair of incisional/ventral hernia: a meta-analysis. Am J Surg. 2008;197:64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pham CT, Perera CL, Watkin DS, Maddern GJ. Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair: a systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:4–15. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0182-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Franklin ME, Jr, Gonzalez JJ, Jr, Glass JL, Manjarrez A. Laparoscopic ventral and incisional hernia repair: an 11-year experience. Hernia. 2004;8:23–27. doi: 10.1007/s10029-003-0163-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wassenaar EB, Schoenmaeckers EJ, Raymakers JT, Rakic S. Recurrences after laparoscopic repair of ventral and incisional hernia: lessons learned from 505 repairs. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:825–832. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0146-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costanza MJ, Heniford BT, Arca MJ, Mayes JT, Gagner M. Laparoscopic repair of recurrent ventral hernias. Am Surg. 1998;64:1121–1127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samuel K, Miller SK, Carey SD, Rodriguez FJ, Smoot RT., Jr . Complications and their management. In: LeBlanc KA, editor. Laparoscopic hernia surgery: an operative guide. London: Arnold; 2003. pp. 161–169. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eriksen JR, Poornoroozy P, Jørgensen LN, Jacobsen B, Friis-Andersen HU, Rosenberg J. Pain, quality of life and recovery after laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. Hernia. 2009;13:13–21. doi: 10.1007/s10029-008-0414-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carbonell AM, Harold KL, Mahmutovic AJ, Hassan R, Matthews BD, Kercher KW, Sing RF, Heniford BT. Local injection for the treatment of suture site pain after laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. Am Surg. 2003;69:688–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bageacu S, Blanc P, Breton C, Gonzales M, Porcheron J, Chabert M, Balique JG. Laparoscopic repair of incisional hernia: a retrospective study of 159 patients. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:345–348. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-0018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heniford BT, Park A, Ramshaw BJ, Voeller G. Laparoscopic repair of ventral hernias: nine years’ experience with 850 consecutive hernias. Ann Surg. 2003;238:391–400. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000086662.49499.ab. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carbajo MA, Martp del Olmo JC, Blanco JI, Toledano M, de la Cuesta C, Ferreras C, Vaquero C. Laparoscopic approach to incisional hernia. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:118–122. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-9079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.LeBlanc KA. Laparoscopic incisional and ventral hernia repair: complications—how to avoid and handle. Hernia. 2004;8:323–331. doi: 10.1007/s10029-004-0250-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wassenaar EB, Raymakers JT, Rakic S. Removal of transabdominal sutures for chronic pain after laparoscopic ventral and incisional hernia repair. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2007;17:514–516. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3181462b9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morales-Conde S, Cadet H, Cano H, Bustos M, Martín J, Morales-Mendez S. Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair without sutures—double crown technique: our experience after 140 cases with a mean follow-up of 40 months. Int Surg. 2005;90(3 Suppl):S56–S62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hasson HM. Open laparoscopy. Biomed Bull. 1984;5:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–213. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LeBlanc KA. Laparoscopic incisional hernia repair: are transfascial sutures necessary? A review of the literature. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:508–513. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-9032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen SQ, Divino CM, Buch KE, Schnur J, Weber KJ, Katz LB, Reiner MA, Aldoroty RA, Herron DM. Postoperative pain after laparoscopic ventral hernia repair: a prospective comparison of sutures versus tacks. JSLS. 2008;12:113–116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wassenaar EB, Raymakers JT, Rakic S. Impact of the mesh fixation technique on operation time in laparoscopic repair of ventral hernias. Hernia. 2008;12:23–25. doi: 10.1007/s10029-007-0269-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paajanen H. Do absorbable mesh sutures cause less chronic pain than nonabsorbable sutures after Lichtenstein inguinal herniorrhaphy? Hernia. 2002;6:26–28. doi: 10.1007/s10029-002-0048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chelala E, Thoma M, Tatete B, Lemye AC, Dessily M, Alle JL. The suturing concept for laparoscopic mesh fixation in ventral and incisional hernia repair: mid-term analysis of 400 cases. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:391–395. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-9014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olmi S, Scaini A, Erba L, Croce E. Use of fibrin glue (Tissucol) in laparoscopic repair of abdominal wall defects: preliminary experience. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:409–413. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-9108-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eriksen JR, Bech JI, Linnemann D, Rosenberg J. Laparoscopic intraperitoneal mesh fixation with fibrin sealant (Tisseel) vs. titanium tacks: a randomised controlled experimental study in pigs. Hernia. 2008;12:483–491. doi: 10.1007/s10029-008-0375-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]