Abstract

The treatment of large soft-tissue defects of the lower leg remains a challenge. The timing of the operation, the most suitable type of tissue, and the decision between local or free flap coverage still remains under discussion. Fifty-two patients were treated with local or free flap coverage after a traumatic soft-tissue defect of the lower leg. We compared the results after treatment with local versus free flaps and fasciocutaneous flaps versus musculocutaneous flaps. In the case of primary reconstruction, we also compared the results regarding the timing of the operation: patients treated within 72 h after the trauma versus patients treated after 72 h. Thirty-five patients (67%) have been treated because of posttraumatic soft-tissue defects and, therefore, insufficient fracture coverage. Seventeen patients (33%) were treated because of a chronic osteomyelitis that arose after the trauma. In our study, we did not find a statistically significant difference between the postoperative complications of local and free flaps. A significant increase could be demonstrated in the number of revisions after treatment with a free flap. Treatment with a fasciocutaneous flap in the entire study group was associated with significantly more postoperative complications than treatment with a musculocutaneous flap. There was no significant difference in results after early or late flap coverage. Patients treated with local or free flaps achieved equal outcomes, except for the number of postoperative revisions in which local flaps required lesser revisions. Treatment with a musculocutaneous flap is preferable to treatment with a fasciocutaneous flap regarding postoperative complications. The timing of operation proved not to be a discriminating factor.

Keywords: Soft-tissue defects, Lower leg, Open tibial fracture, Fasciocutaneous flap, Musculocutaneous flap

Fractures of the tibia are fractures that are frequently associated with an open fracture. The lower leg is relatively badly protected, owing to the superficial position of the tibia and the lack of proper soft tissue coverage. The treatment of these often large, soft-tissue defects remains a challenge for both the reconstructive surgeon and other involved disciplines. This requires a simultaneous approach of both the damaged soft tissue and the bone. Fractures of the lower leg are most frequently caused by traffic accidents (motor, car, and bicycle accidents), sports (soccer), and outdoor falls.

Open fractures of the tibia have a high incidence of infection and malunion [1, 2]. Formerly, the treatment of severe lower leg injuries often consisted of primary amputation [3]. Developments in the field of osteosynthesis and reconstructive techniques have led to new treatment possibilities. Early fracture stabilization is essential and can be achieved by means of external fixation, plate and screws, and reamed or unreamed tibial nails. Combined with stabilization, a thorough debridement is essential for further treatment [4, 5].

Regarding soft-tissue defects, the optimal timing of the operation, the most suitable type of tissue, and the consideration between a local or free approach still remains under discussion. Previous studies describe different outcomes and because of this they recommend different strategies. In this retrospective study, we have tried to contribute to this discussion through an analysis of our material

Patients and methods

Between January 2000 and March 2008, 52 patients were treated with a free or local flap following a traumatic open fracture of the lower leg. All patients were treated at a single academic hospital. Data was gathered by reviewing patient charts, operative reports, and electronic patient record.

In our study, patients were divided into two groups. In the first group, patients were treated because of posttraumatic soft-tissue defects and, therefore, insufficient fracture coverage (primary reconstruction). Patients in the second group were treated because of a chronic osteomyelitis that arose after the trauma. We compared the results after treatment with local versus free flaps and fasciocutaneous flaps versus musculocutaneous flaps. In the case of primary reconstruction, we also compared the results regarding the timing of the operation: patients treated within 72 h after the trauma versus patients treated after 72 h. Outcome was assessed according to the number of postoperative complications (infections, hematoma or hemorrhage, and dehiscence), partial and complete flap failures, secondary amputations and revisions, the length of hospital stay, and regaining of preoperative mobility. In the second group, outcome was also assessed according to the number of relapses of osteomyelitis (Fig. 1).

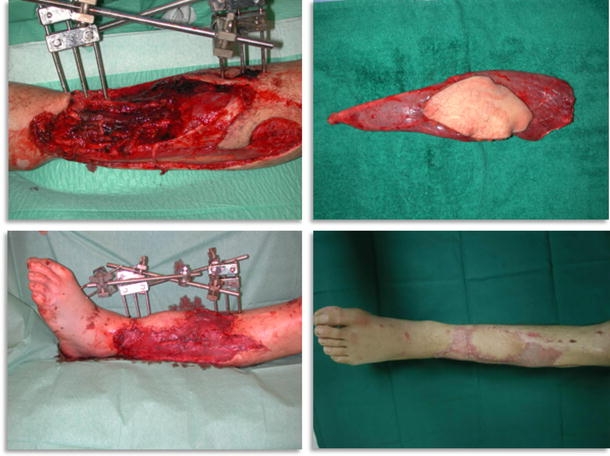

Fig. 1.

Left lower leg trauma after a traffic accident, operated on within 24 h with vascular reconstruction, debridement, and external fixation (above, left). Free vascularized gracilis muscle flap (above, right). Postoperative result after gracilis muscle transfer and split skin grafting (below, left). Reconstructed leg 2 months after surgery (below, right)

The chi-square test was performed for statistical evaluation. In the case of length of hospital stay, we used the Mann–Whitney test. A p value of <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

With a total of 39 men and 13 women, the male gender is by far the most represented. The mean age was 44.5 years (range, 15–79 years). The causes of the lower leg trauma are displayed in Table 1. In the entire study group, 35 (67%) patients were treated because of posttraumatic soft-tissue defects and, therefore, insufficient fracture coverage (primary reconstruction) and 17 (33%) patients because of a chronic osteomyelitis that arose after the trauma.

Table 1.

Causes of lower leg trauma

| Traffic accidents (73%) | |

| Motorbike | 15 |

| Car | 12 |

| Bicycle | 5 |

| Pedestrian | 4 |

| Airplane | 1 |

| Carriage | 1 |

| Work-related accidents (17%) | |

| Agriculture machine | 4 |

| Forklift truck | 3 |

| Ship wharf | 2 |

| Other (10%) | |

| Shooting | 1 |

| Grenade | 1 |

| Sporting | 1 |

| Unknown | 2 |

In total, 32 local flaps and 20 free flaps were used for reconstruction. As can be expected, free flaps are more frequently used in the treatment of distal third fractures of the tibia because of the limited possibilities for local reconstruction (Table 2).

Table 2.

Overview of the transferred flaps

| Location of the defect | Transferred tissue | Number |

|---|---|---|

| Proximal third | Local | 11 |

| Gastrocnemius | 10 | |

| Fasciocutaneous | 1 | |

| Free | 2 | |

| Latissimus dorsi | 2 | |

| Middle third | Local | 8 |

| Soleus | 6 | |

| Sural | 2 | |

| Free | 4 | |

| Anterolateral thigh flap (ALT) | 1 | |

| Gracilis | 1 | |

| Rectus abdominis | 1 | |

| Latissimus dorsi | 1 | |

| Distal third | Local | 13 |

| Sural | 8 | |

| Fasciocutaneous | 3 | |

| Tibialis anteriora | 1 | |

| Flexor hallucis longusa | 1 | |

| Lateral calcaneal artery flap | 1 | |

| Free | 14 | |

| Rectus abdominis | 5 | |

| Gracilis | 4 | |

| ALT | 3 | |

| Latissimus dorsi | 2 |

aBoth muscle transfers were used at the same patient in the same session

In the entire study group, 16 patients (31%) developed a postoperative complication, which consisted of hematoma (10%), hemorrhage (2%), flap dehiscence (4%), or infection (23%). Six patients (12%) developed a partial flap failure, after which the necrotic skin was resected. Complete flap failure occurred in eight patients (15%). A secondary lower leg amputation had to be performed in three patients (6%).

One or more revisions were performed in 15 patients (29%). Forty-one patients (84%) regained their preoperative mobility and eight patients were limited to some extent after treatment. In three patients, mobility could not be assessed because of departure to their home country shortly after discharge from the hospital. The median length of hospital stay was 16 days (range, 4–128 days).

Primary reconstruction

In 35 patients, a primary reconstruction was performed. Seven patients (20%) had a defect located at the proximal third of the tibia, seven patients (20%) at the middle third, and 21 patients (60%) at the distal third. Table 3 shows an overview of the Gustilo classification after an initial examination at the emergency room. A local flap was used in 21 patients (60%) and 14 patients (40%) were treated with a free flap. Fifteen patients (43%) underwent a fasciocutaneous flap transfer and 20 patients (57%) underwent a musculocutaneous flap transfer.

Table 3.

Gustilo classification after initial survey at the emergency room

| Grade | Percent |

|---|---|

| I | 11 |

| II | 17 |

| IIIa | 20 |

| IIIb | 43 |

| IIIc | 9 |

The average duration between the trauma and the operation was 27 days, with a median duration of 11 days (range, 0–176 days). One patient was treated after 176 days because of late necrosis of the lower leg muscles and development of a compartment syndrome. Other patients were operated on after several days because of their initially critical condition. Most of these patients were polytrauma patients with a long intensive care unit stay and initial treatment for other (life-threatening) injuries. Within this group, only 12 patients were diagnosed with just a lower leg injury. Other patients were diagnosed with other fractures, head or brain injuries, intra-abdominal injuries, and pneumothorax. After the initial trauma screening, fixation of the fracture was performed, either directly or at a later stage. The fracture was stabilised by means of an external fixator in 15 patients (43%), a plate and screw fixation in 11 patients (31%), and an intramedullary nail in nine patients.

A hematoma developed in five patients (14%) as a postoperative complication. One patient (3%) had a hemorrhage, nine patients (26%) developed an infection, and two patients (6%) had a dehiscence of their flaps. Four patients (11%) underwent debridement because of a partial flap failure and six patients (17%) because of complete flap failure. Eventually, two patients (6%) underwent a secondary amputation. Table 4 shows the outcomes of local and free flaps and fasciocutaneous and musculocutaneous flaps in the entire study group.

Table 4.

Outcomes of local and free flaps and fasciocutaneous and musculocutaneous flaps

| Local flaps (N = 32) | Free flaps (N = 20) | p value | Fasciocutaneous (N = 19) | Musculocutaneous (N = 33) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total complications (%) | 28.1 | 35 | 0.601 χ | 47.4 | 21.2 | 0.049 χ |

| Infection (%) | 21.9 | 25 | 0.795 χ | 26.3 | 21.2 | 0.674 χ |

| Complete flap failure (%) | 9.4 | 25 | 0.129 χ | 21.1 | 12.1 | 0.390 χ |

| Partial flap failure (%) | 12.5 | 10 | 0.784 χ | 15.8 | 9.1 | 0.467 χ |

| Secondary amputation (%) | 3.1 | 10 | 0.301 χ | 10.5 | 3.0 | 0.264 χ |

| Revisions (%) | 18.8 | 45 | 0.042 χ | 26.3 | 30.3 | 0.760 χ |

| Regaining mobility (%) | 86.2 | 75 | 0.319 χ | 81.3 | 81.8 | 0.962 χ |

| Length of hospital stay (median, days) | 13.5 | 31.1 | 0.085 M | 16 | 17 | 0.278 M |

χ chi-square test, M Mann–Whitney test

Osteomyelitis

Chronic osteomyelitis occurred in 17 patients after the initial trauma. Six patients (35%) had a defect located at the proximal third of the tibia, five (29%) patients at the middle third, and six (36%) at the distal third.

A local flap was applied in 11 patients (65%) and a free flap was used in six patients (35%). Four patients (24%) underwent a fasciocutaneous flap transfer and 13 patients (76%) underwent a musculocutaneous flap transfer.

None of the patients developed a hematoma, hemorrhage, or dehiscence of their flap as a postoperative complication. Three patients (18%) developed an infection. Two patients (12%) underwent debridement because of a partial flap failure and two patients (12%) because of complete flap failure. A relapse of osteomyelitis occurred in three patients (18%). A secondary amputation was performed in one patient (6%) because of relapsing chronic osteomyelitis.

Discussion

Much has changed in the treatment of soft-tissue defects after open fractures of the lower leg. The introduction of free flaps provided a virtually unlimited supply of tissue for reconstruction. Early treatment is more widespread and advocated after the introduction of antibiotic prophylaxis and improved techniques for fracture stabilization. Advocates of delayed flap coverage refer to the expansion of the zone of injury and prefer serial debridements before definitive treatment [4, 6]. Distal third wounds of the lower leg especially remain a challenge for the plastic and traumatologist surgeon because of the limited possibilities for local muscle transposition. As shown in Table 2, free flaps are frequently used for defects of the distal third and often remain the only possibility for treatment. Other studies recommend initial treatment with a vacuum-assisted closure system. These studies describe vacuum-assisted closure being applied either as a bridge to surgery by diminishing the surface area of the wound and inducing tissue granulation or as a definitive treatment in combination with skin grafting [4, 7, 8].

Comparing the results after free flap coverage with local flap coverage in our study group, no statistically significant differences were found, other than a statistically lower number of revisions after treatment with a local flap. Patients treated with local flaps showed better results on almost every other aspect, but these differences did not appear to be significant. On one hand, it can be expected that a free flap from a nontraumatized region of the body would perform better than a local flap within the damaged lower leg. On the other hand, practical experience shows that, in case of large or serious defects, free flaps remain the only possibility for reconstruction, whereas local flaps can be used in less serious or smaller defects. In our study, patients treated with a free flap did have a higher Gustilo classification, which in turn is associated with a higher infection rate [9]. Because of the fact that free flaps demand a long and costly procedure, a specialized team of plastic surgeons and traumatologists is required, and free flaps are frequently associated with postoperative complications, the preference for treatment with local flaps has to be considered [10, 11].

When comparing the treatment of fasciocutaneous flaps with musculocutaneous flaps, we found a statistically lower amount of postoperative complications in the patients treated with a musculocutaneous flap (Table 4). The osteomyelitis group treated with a musculocutaneous flap showed better outcomes on every aspect, but because of the small amount of patients, these numbers were not significant. Musculocutaneous flaps fill up dead spaces and reduce the risk of infection by providing an improved circulation and oxygen transport to the wound. On the other hand, fasciocutaneous flaps can provide a better cosmetic and functional result, especially when related to defects located at the distal third of the lower leg [12, 13].

In our study, we could not find a statistical difference regarding the timing of the operation. Previous, often older, studies show an increase in infection after early primary closure and, therefore, recommend delayed closure [14]. Treatment within 72 h after the trauma in our study did not result in a significant increase in postoperative complications such as infection or flap failure. Other studies show a reduction in the occurrence of postoperative flap infection and other complications after early flap coverage [15–17]. A possible bias in our study could be the fact that patients treated after 72 h often could not be operated on at an earlier stage because of comorbidity or long intensive care unit stay. These patients are assumed to be at a greater risk of developing postoperative complications. In our study, the plastic surgeon was often not consulted directly after the trauma, and this policy makes it impossible to treat patients who are candidates for treatment within 72 h.

Conclusion

Patients with large soft-tissue defects of the lower leg after a traumatic open tibial fracture should be initially treated with a local, musculocutaneous flap whenever possible. If the location or size of the defect makes local reconstruction impossible, free flaps remain the only possibility for reconstruction. The use of vacuum-assisted closure to obtain a surface area suitable for a further treatment down the reconstructive ladder has to be considered. The plastic surgeon should be consulted in an early stage after the trauma to determine if patients are candidates for early flap coverage.

Acknowledgments

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Patzakis MJ, Wilkins J, Moore TM. Use of antibiotics in open tibial fractures. Clin Orthop. 1983;178:31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dickson K, Katzman S, Delgado E, et al. Delayed unions and nonunions of open tibial fractures. Correlation with arteriography results. Clin Orthop. 1994;302:191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aldea PA, Shaw WW. The evolution of the surgical management of severe lower extremity trauma. Clin Plast Surg. 1986;13:549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parrett BM, Matros E, Pribaz JJ, et al. Lower extremity trauma: trends in the management of soft-tissue reconstruction of open tibia-fibula fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:1315. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000204959.18136.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reddy V, Stevenson TR. MOC-PS(SM) CME article: lower extremity reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:1. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000305928.98611.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karanas YL, Nigriny J, Chang J. The timing of microsurgical reconstruction in lower extremity trauma. Mircosurgery. 2008;28:632. doi: 10.1002/micr.20551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeFranzo AJ, Argenta LC, Marks MW, et al. The use of vacuum-assisted closure therapy for the treatment of lower-extremity wounds with exposed bone. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:1184. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200110000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herscovici D, Jr, Sanders RW, Scaduto JM, et al. Vacuum-assisted wound closure (VAC therapy) for the management of patients with high-energy soft tissue injuries. J Orthop Trauma. 2003;17:983. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200311000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gustilo RB, Anderson JT. Prevention of infection in the treatment of one thousand and twenty-five open fractures of long bones: retrospective and prospective analyses. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;58:453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heinz TR, Cowper PA, Levin LS. Microsurgery costs and outcome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104:89. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199907000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benacquista T, Kasabian AK, Karp NS. The fate of lower extremities with failed free flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98:834. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199610000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yazar S, Lin CH, Lin YT. Outcome comparison between free muscle and free fasciocutaneous flaps for reconstruction of distal third and ankle traumatic open tibial fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:2471. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000224304.56885.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yaremchuk MJ. Acute management of severe soft-tissue damage accompanying open fractures of the lower extremity. Clin Plast Surg. 1986;13:621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Russell GG, Henderson R, Arnett G. Primary or delayed closure for open tibial fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990;72:125. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.72B1.2298770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Godina M. Early microsurgical reconstruction of complex trauma of the extremities. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;78:285. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198609000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cierny G, Byrd HS, Jones RE. Primary versus delayed soft tissue coverage for severe open tibial fractures: a comparison of results. Clin Orthop. 1983;178:54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fischer MD, Gustilo RB, Varecka TF. The timing of flap coverage, bone-grafting, and intramedullary nailing in patients who have a fracture of the tibial shaft with extensive soft-tissue injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:1316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]