Adaptive changes have long been recognized to occur in the heart and vasculature in response to chronic hypertension. What might be less well appreciated is the fact that chronically increased blood pressure is also associated with adaptive changes in neurons within the central nervous system (CNS). Changes in the properties of ligand-gated and voltage-gated channels have been described in a variety of neurons in a variety of central nuclei and in a variety of models of hypertension.

γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter in virtually every region in the adult brain. Microinjections of GABA and GABA receptor subtype selective agonists and antagonists have been performed within various cardiovascular-related regions of the CNS. Suffice it to say that in every cardiovascular-related region of the CNS tested, activation of GABA receptors alters cardiovascular function. This is likely due to the ubiquitous role of GABA within the CNS. GABAergic inhibition can be mediated by activation of receptors located in both pre-synaptic and post-synaptic loci. Two major subtypes of the GABA receptor exist: the GABAA receptor is a pentameric, chloride ionophore that primarily mediates post-synaptic inhibition1 while the GABAB receptor is a G-protein coupled receptor that can induce reductions in calcium-conductance to mediate pre-synaptic inhibition and increases in potassium conductance to mediate post-synaptic inhibition2.

GABAergic inhibition of central neurons can result in pressor or depressor responses depending upon the central site being examined. Pressor responses are often assumed to be the result of GABAergic inhibition of neurons that reduce sympathetic discharge. Depending upon the specific area being studied, GABA injections into the CNS can also alter vagal cardiac function and levels of vasoactive hormones such as vasopressin and angiotensin in addition to changes in sympathetic outflow3, 4.

In addition to microinjection studies, in vivo and in vitro electrophysiological analyses of functionally identified neurons in cardiovascular related CNS areas are useful in the analysis of mechanisms that underlie alterations in GABAergic neurotransmission in hypertensive animals. Due to space constraints this review will selectively summarize changes in GABAergic transmission in hypertensive rats that have recently been described in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS), the first integrative site for baroreceptor afferent inputs within the CNS.

Nucleus of the solitary tract and hypertension

Within caudal regions of the NTS, microinjection of GABAA or GABAB receptor agonists increase arterial pressure, presumably due to GABAergic inhibition of NTS neurons receiving arterial baroreceptor afferent inputs4-6. Furthermore, microinjection of GABAA or GABAB receptor antagonists lower arterial pressure indicating that GABAergic inhibition via both receptor subtypes is a tonically active process within the NTS4, 7. The pressor and sympatho-excitatory responses induced by the microinjection of GABAA receptor agonists were no different comparing normotensive rats to spontaneously hypertensive, DOCA-salt and renal-wrap hypertensive rats8-10. In contrast, pressor and sympatho-excitatory responses to activation of GABAB receptors are enhanced in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRs), DOCA-salt and renal-wrap hypertensive rats8-11. These microinjection studies strongly suggest hypertension-induced alterations in GABAergic mechanisms in the NTS. However, due to inherent limitations of the microinjection technique, they provide little insight into the specific changes that occur in individual NTS neurons. Electrophysiological analyses of NTS neurons receiving arterial baroreceptor inputs provide insights into hypertension-induced neural plasticity of GABAergic mechanisms in the NTS.

The responses of individual NTS neurons which receive arterial baroreceptor afferent inputs to exogenous application of GABA receptor selective agonists have been examined in normotensive and in renal-wrap hypertensive rats. An in vivo study of NTS neurons receiving baroreceptor inputs, and therefore presumed to be sympatho-inhibitory in function, found that the ability of the GABAA receptor agonist muscimol to inhibit aortic nerve (baroreceptor) evoked discharge was reduced after both 1 and 4 weeks of hypertension12. Conversely, the ability of the GABAB receptor agonist baclofen to inhibit aortic nerve evoked discharge was enhanced after both 1 and 4 weeks of hypertension. The changes in sensitivity to activation of GABAA and GABAB receptors were found to occur in NTS neurons that received rapidly conducting baroreceptor afferent inputs and in NTS neurons that received slowly conducting baroreceptor afferent inputs. The results demonstrate that early in hypertension the sensitivity of NTS neurons to activation of GABA receptors is altered and that these changes are maintained for at least 4 wk. Directionally opposite changes in sensitivity occur in response to GABAA (reduced inhibition) and GABAB (enhanced inhibition) receptor selective agonists.

In vitro electrophysiological analyses provide additional insights to those obtained in vivo, particularly if one attempts to obtain some level of identification of neuronal function in the in vitro setting to demonstrate potential functional significance. Anatomical labeling techniques have been used to identify NTS neurons receiving aortic nerve (baroreceptor) inputs in in vitro preparations so that this specific class of neuron can be studied13. In labeled neurons isolated from the NTS of renal-wrap hypertensive rats, changes in the post-synaptic responses to activation of GABAA and GABAB receptors mirrored the changes observed in vivo. The mid-point of the dose-response curve (EC50) for peak GABAA currents was significantly greater in neurons from hypertensive compared with normotensive rats14. The time constant for desensitization of GABAA evoked currents was the same in neurons from hypertensive and normotensive rats indicating that the reduced sensitivity was not associated with a change in desensitization of GABAA evoked responses. The alterations in GABAA receptor evoked currents are consistent with the in vivo observations and indicate that NTS neurons receiving arterial baroreceptor inputs are less sensitive to GABAA receptor inhibition.

GABAB receptors can mediate both pre and post-synaptic inhibition. In vitro analyses of GABAB evoked responses were performed using a brain slice preparation so that both the pre-synaptic and post-synaptic components of GABAB mediated inhibition could be analyzed in NTS neurons receiving arterial baroreceptor afferent inputs15. GABAB evoked post-synaptic responses were consistent with the in vivo observations. The EC50 of the post-synaptic outward potassium current induced by application of the GABAB agonist baclofen was significantly less in NTS neurons recorded in brain slices from hypertensive compared to normotensive rats suggesting an enhanced post-synaptic response to activation of GABAB receptors in second-order baroreceptor neurons in the NTS in renal-wrap hypertensive rats.

More recent studies in our lab indicate alterations also occur in the pre-synaptic GABAB receptor that could influence glutamate and GABA release in hypertension. Recordings were obtained from NTS neurons in a brain slice using pipettes filled with cesium to block potassium currents so that pre-synaptic GABAB effects could be observed in the absence of post-synaptic GABAB evoked outward current. Baclofen reduced the amplitude of tractus evoked excitatory post-synaptic currents (eEPSCs) in the absence of a direct effect on the post-synaptic membrane suggesting that reduced EPSC amplitude was the result of GABAB receptor mediated pre-synaptic inhibition. The EC50 of the GABAB receptor mediated pre-synaptic inhibition of eEPSC amplitude was significantly reduced in hypertensive compared to normotensive rats (Zhang and Mifflin, unpublished observations). The results suggest that in renal-wrap hypertensive rats baclofen evokes an enhanced pre-synaptic inhibition of glutamate release in 2nd-order baroreceptor neurons.

Nucleus of the solitary tract and exercise

During exercise, the arterial baroreflex is reset to operate at higher pressures in humans16. GABAergic mechanisms in the NTS have also been shown to be involved in exercise-induced resetting of the baroreflex in the rat17. Somatosensory afferent fibers originating from skeletal muscle are activated during exercise and release substance P in the NTS which directly activates NTS GABAergic neurons18. The GABAergic neurons then inhibit NTS neurons receiving baroreceptor inputs to reset the reflex function curve. The model is similar to that proposed for reflex resetting in hypertension where the resetting moves the set-point to the middle (linear) range of the reflex function curve19.

In relation to hypertension, a single bout of mild to moderate exercise can lead to a prolonged, post-exercise decrease in blood pressure in hypertensive subjects20. Studies in the SHR have shown that during this “post-exercise hypotension” the release of GABA is reduced within the NTS, therefore the inhibition of NTS neurons by somatic afferents is reduced contributing to a reduction in blood pressure21. The reduced release of GABA was shown to be associated with internalization of the Substance P (NK-1) receptor so that somatic afferent activation during exercise produces less excitation of the GABAergic neurons21. It is not known if the reduced Substance P-mediated excitation of GABAergic neurons is a result of the hypertension.

It's not all about GABA

Neuronal adaptations to hypertension within the NTS are not restricted to alterations in GABAergic mechanisms. Anatomical studies report alterations in excitatory amino acid, AMPA receptor subunits within the NTS in hypertension22, 23. Hypertension also induces alterations in voltage-gated ion channels within the NTS. In renal-wrap hypertensive rats, the transient outward potassium current (IA), a K current contributing to neuronal excitability, is reduced in NTS neurons receiving arterial baroreceptor inputs, whereas delayed rectifier potassium currents are normal24. Delayed excitation, one current-clamp manifestation of IA, has also been reported in NTS neurons25 in SHR. The recent finding that many NTS neurons that exhibit IA project to the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN)26 suggests that this alteration could influence the baroreceptor signal that is relayed to the hypothalamus and subsequently sympathetic outflow.

Hypertension also induces enhanced current flow through high-voltage activated, but not low-voltage activated, Ca2+ channels in NTS neurons that receive baroreceptor afferent inputs27. There is a link between enhanced calcium influx and reduced GABAA receptor function. Increased Ca2+ influx, as a result of synaptic (NMDA) depolarization28 or depolarizing voltage pulses29, reduces the neuronal response to activation of GABAA receptors.

These findings emphasize that neurons exhibit a number of adaptive changes in hypertension. There are no doubt numerous other changes in these neurons and in other regions of the CNS that have yet to be described. Present efforts to provide a comprehensive model that explain alterations in neural regulation of cardiovascular function in hypertension are limited by the incomplete state of our current knowledge regarding the full extent of the adaptations; that is what changes and where?

What alters GABA receptor function in hypertension?

What might initiate neuronal adaptations to chronic hypertension? The in vitro findings have an important implication in that whatever alters the sensitivity of second-order NTS neurons to the activation of GABAA and GABAB receptors, the altered sensitivity persists at least for several hours in the absence of the hypertension due to the nature of in vitro preparation. Increased levels of GABAB mRNA have been reported in the NTS of both renal-wrap hypertensive and SHRs30, 31, so enhanced GABAB responses in hypertension might be due to increased receptor levels if the increased message is translated into increased receptor protein.

The pressure sensitivity of arterial baroreceptors “resets” in hypertension so that the threshold pressure necessary to evoke discharge is elevated. Supra-threshold sensitivity may, or may not, be normal; however it is important to realize that the absolute number of baroreceptor afferents discharging at a given pressure is increased in chronic hypertension. In normotensive rabbits, approximately 91% of myelinated and 28% of unmyelinated baroreceptor afferent fibers are discharging at the resting levels of arterial pressure. In chronically hypertensive rabbits, approximately 100% of myelinated and 78% of unmyelinated baroreceptor afferent fibers are discharging at the resting, hypertensive, level of arterial pressure32. This suggests a large increase in tonic excitatory baroreceptor afferent input to the NTS in chronic hypertensive animals, primarily as a result of recruitment of unmyelinated afferent fibers.

Therefore, alterations in GABA receptor function could be the result of an increased baroreceptor afferent input to the NTS and the subsequent effect(s) of increased discharge and/or increased exposure to neurotransmitters. We have found reduced levels of message for the GABAA-α1 subunit in the NTS of renal wrap hypertensive rats (Fig. 1). This suggests that the reduced GABAA receptor responses observed in vivo and in vitro may be the result of reduced levels of GABAA receptor. This reduction is abolished by sectioning the carotid sinus and aortic depressor nerves to eliminate baroreceptor afferent inputs to the NTS prior to the onset of hypertension suggesting that the reduced expression of the NTS GABAA-α1 subunit in hypertension is dependent upon baroreceptor afferent inputs to the NTS.

Figure 1.

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of levels of a GABAA–α1 receptor subunit in the NTS using a previously described competitive method63. The bar graphs represent the mass ratio of the target message to an internal standard directed towards the same sequence as the target but smaller in length in, from left to right: normotensive (sham) rats with sino-aortic nerves intact; renal wrap hypertensive rats with sino-aortic nerves intact; normotensive rats with sino-aortic denervation (SAD); renal wrap hypertensive rats with SAD. The gel below illustrates in each lane, from left to right, a molecular weight standard followed by samples from 2 - 4 separate rats in each group. The upper bands in the data lanes are the target message above with the internal standard below. Star indicates significant difference compared to sham intact.

If excitatory drive to the NTS is increased in hypertension, one would predict that these neurons would exhibit an increased discharge frequency in hypertensive animals. However, the discharge frequency of NTS neurons receiving arterial baroreceptor inputs is not different in renal-wrap hypertensive rats33. It has been proposed that increased GABAB receptor mediated inhibition may limit the excitatory drive to NTS neurons in hypertension19.

Factors that regulate GABAB receptor function less well studied than those that regulate GABAA receptor function. The availability of surface GABAB receptors is regulated by glutamate in hippocampal and cortical neurons, however the results are not consistent34, 35. Activation of GABAB receptors with baclofen did not influence receptor endocytosis in these neurons36 35, but it did increase receptor degradation through mechanisms that were independent of endocytosis36. Increased calcium influx through voltage gated calcium channels has been described in the NTS of hypertensive rats37, and changes in intracellular calcium could initiate alterations in gene expression that influence any of the numerous mechanisms shown to alter GABAA and GABAB receptor function (e.g., receptor expression, subunit composition, trafficking, phosphorylation status)1. Transcription factors that could mediate neuronal adaptations in hypertension include the immediate early gene product c-Fos38, 39 and the intermediate factor FosB (Cunningham and Mifflin, unpublished observations).

Other factors to consider as initiators of neuronal adaptation in hypertension are changes in tissue or systemic levels of hormones induced by chronic hypertension. These neurochemicals may also cause alterations in neural structures not immediately involved in baroreflex. Many of the changes reported in NTS neurons from hypertensive rats (alterations in K+ and Ca2+ channel conductances) are similar to the acute effects of angiotensin (AngII) acting on AT1 receptors on brainstem neurons40. In addition to direct effects on NTS neurons receiving arterial baroreceptor inputs, recent work suggests that AngII can also activate eNOS and the resulting release of NO stimulates GABA release and inhibition of NTS neurons receiving arterial baroreceptor inputs41.

AngII may also play a role in initiating hypertension-induced changes in GABAB receptor function as recent in vitro work found that application of AngII to NTS neuronal cultures induce a two-fold increase in GABAB receptor expression42. Treatment of the NTS neuronal cultures with AngII had no effect on GABAA receptor expression. Perfusion of NTS neuronal cultures with baclofen decreased neuronal discharge frequency by a greater amount in cultures pre-treated with AngII, indicating that chronic AngII treatment significantly enhanced the neuronal response to GABAB receptor activation. AngII had no effect on the inhibitory action of the GABAA receptor agonist muscimol suggesting the actions of AngII were selective for the GABAB receptor. In whole animal studies, intracerebroventricular infusion of AngII was associated with an elevation of GABAB receptor mRNA and protein levels in the NTS; however there was an AngII-induced increase in MAP that could contribute to the obsrevation. These results indicate that AngII stimulates GABAB receptor expression in NTS neurons. Since the renal-wrap model of hypertension is AngII dependent43, AngII could mediate changes in GABAB receptor function reported in the NTS and PVN of renal-wrap hypertensive rats30, 44. It would be very interesting to examine GABA evoked responses in renal-wrap hypertensive rats following prolonged blockade of AngII receptors within the NTS. In addition to an increase in receptor protein, AngII could also increase GABAB receptor function via common G-protein coupled receptor signal transduction pathways activated by AngII and GABAB receptors.

Specificity and selectivity

To this point, the question has been framed “What happens to neurons receiving a baroreceptor afferent input during chronic hypertension?” A question that arises from these observations is to what extent are neuronal adaptations to hypertension within the NTS restricted to neurons receiving arterial baroreceptor afferent inputs?

The in vivo study cited previously45 examined responses of NTS neurons that did not receive aortic nerve inputs to iontophoretic application of GABAA and GABAB receptor agonists. There was no change in the inhibition of spontaneous discharge induced by activation of GABAA receptors while inhibition induced by activation of GABAB receptors was enhanced as observed in neurons receiving aortic nerve inputs. The in vitro analysis of NTS neuronal responses to activation of GABAA receptors found no difference in the dose-response relationship of neurons receiving aortic nerve inputs and neurons not receiving aortic nerve inputs, although the sample size was small14. Similarly, changes in transient outward potassium currents37 and high-threshold voltage-gated calcium channels46 did not differ comparing NTS neurons that received aortic nerve inputs to those that did not receive aortic nerve inputs.

It is possible that at least some portion of the non-aortic nerve activated population of NTS neurons in these studies receive inputs from other arterial and/or cardiac/thoracic baroreceptors. The model hypothesized to explain alterations in NTS neuronal responses in hypertension proposed that increased baroreceptor afferent input to the NTS was the primary initiator of the neuronal adaptations19. The finding that GABAA-α1 receptor subunit mRNA levels are reduced in hypertensive rats and that this reduction can be abolished by section of baroreceptor afferent nerves is consistent with this hypothesis. However, removal of baroreceptor afferent inputs is likely to alter numerous other factors that could influence the neurons; e.g., circulating and/or tissue levels of hormones, hind brain blood flow, glucose and/or oxygen availability. The fact that a reduction in receptor subunit levels is observed is surprising given the relatively small number of cells within the NTS that receive an arterial baroreceptor input and suggests that alterations in GABA-gated receptors and voltage-gated ion channels occur in a larger population of NTS neurons than those that receive solely arterial baroreceptor afferent inputs.

If neuronal adaptations occur in a larger population of NTS neurons, one might predict that other reflex or integrative functions of NTS neurons not involved in baroreflexes would be altered in hypertensive animals. Alterations in cardiopulmonary mechanoreflexes47, 48 and arterial chemoreflexes49 have been reported in hypertensive rats.

Significance of alterations in central GABAergic mechanisms in hypertension

At present it is difficult to estimate the contribution of the hypertension induced changes in GABAergic mechanisms in the hindbrain to cardiovascular regulation in hypertension. In the context of cardiovascular regulation and hypertension, altered GABAergic neurotransmission is only one of a myriad of factors in the overall adaptive response. These and other changes are likely to occur in other central areas and have yet to be fully characterized. For example, a “tonic GABAA current” has been identified in paraventricular neurons that project to the RVLM50. The extent to which this current, if present, is altered in the NTS or any other brain region in hypertension has yet to be examined.

Some insight can be gleaned by looking at the output side of the CNS. The tonic discharge frequency of putative sympatho-excitatory neurons within the RVLM is normal in the SHR and baroreflex inhibition of this discharge appears normal, albeit shifted towards higher pressures51. Using the immediate early gene product c-Fos as an indicator of neuronal activation, the number of neurons exhibiting c-Fos is elevated in the NTS, CVLM, RVLM and PVN in renal-wrap hypertensive rats38.

A model whereby increased GABAB receptor function offsets, to some extent, increased excitatory baroreceptor input to NTS neurons has been proposed19. The increased number of active neurons in the NTS of hypertensive rats described in the c-Fos study38 suggests that any reduction in excitatory synaptic input mediated by increased GABAB receptor pre-synaptic inhibition is not sufficient to prevent recruitment of additional neurons. However, it appears to be sufficient to normalize NTS discharge which remains normal ensuring that discharge remains at a level where the neuron can still respond to increases or decreases in MAP. If increased GABA release in the PVN in renal-wrap hypertensive rats52 is dependent upon the NTS, the model predicts that it is the result of an increased number of active NTS neurons and not an increased discharge in any given neuron. This model is also consistent with the finding of normal baroreflex inhibition of RVLM neurons in SHR51.

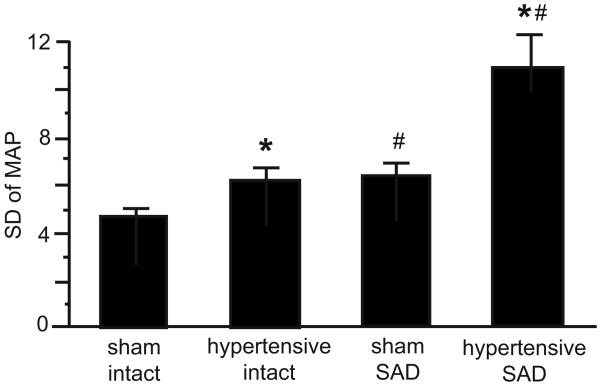

A study by Haywood's group emphasizes the important role that the baroreflexes play in normotension and hypertension and may provide some insight into the significance of neuronal adaptations in NTS neurons receiving arterial baroreceptor inputs53. In renal-wrap hypertensive rats MAP variability is increased by approximately 50% (Fig. 2). This indicates a diminution in baroreflex buffering capability, although contributions from the neuro-effector junction cannot be excluded. Sino-aortic denervation (SAD), to eliminate baroreceptor inputs to the CNS, in normotensive rats also increased MAP variability by 50%. However, in SAD renal-wrap hypertensive rats, MAP variability was nearly double that in SAD normotensive rats. Therefore, the contribution of the baroreflexes to the mechanisms that serve to minimize MAP variability is actually much greater in hypertensive compared to normotensive animals. Increased MAP variability has been associated with increased risk of cardiovascular mortality due to myocardial infarction, stroke and end-organ damage such as for stroke, and end-organ (heart, kidney, blood vessel) damage 54-62. There is an ongoing debate of the role of the arterial baroreflexes in the determination of the absolute level of MAP in normotension and hypertension. Regardless, the role of the arterial baroreflexes in the determination of the stability of MAP is not in dispute and it may well be that the ability to maintain some degree of baroreflex buffering that is of equal clinical significance in hypertension.

Figure 2.

Standard deviation of 1-hour blood pressure values were used as an index of lability of MAP. Weekly average of the lability of MAP after renal wrap or sham surgery. * P < 0.05 vs sham. # P < 0.05 vs intact. Figure reproduced by permission from VanNess et al.53

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: This work was supported by HL56637.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Both authors declare there are no relevant financial, personal or professional relationships with other people or organizations.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mehta A, Ticku M. An update on GABA-A receptors. Brain Research Rev. 1999;29:196–217. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(98)00052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ulrich D, Bettler B. GABA-B receptors: synaptic functions and mechanisms of diversity. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17:298–303. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett JA, McWilliam PN, Shepheard SL. A GABA-mediated inhibition of neurones in the nucleus tractus solitarius of the cat. Journal of Neurophysiology (London) 1987;392:417–430. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Catelli JM, Giakas WJ, Sved AF. GABAergic mechanisms in nucleus tractus solitarius alter blood pressure and vasopressin release. Brain Res. 1987;403:279–289. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sved AF, Tsukamoto K. Tonic stimulation of GABAB receptors in the nucleus tractus solitarius modulates the baroreceptor reflex. Brain Research. 1992;592:37–43. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91655-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ito S, Sved AF. Influence of GABA in the nucleus of the solitary tract on blood pressure in baroreceptor-denervated rats. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;273:R1657–R1662. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.273.5.R1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sved AF, Sved JC. Endogenous GABA acts on GABAB receptors in nucleus tractus solitarius to increase blood pressure. Brain Res. 1990;526:235–240. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91227-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Durgam VR, Vitela M, Mifflin SW. Enhanced GABA-B receptor agonist responses and mRNA within the nucleus of the solitary tract in hypertension. Hypertension. 1999;33:530–536. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.1.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsukamoto K, Sved AF. Enhanced GABA-mediated responses in nucleus tractus solitarius of hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1993;22:819–825. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.22.6.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yin M, Sved AF. Role of gamma-aminobutyric acid B receptors in baroreceptor reflexes in hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1996;27:1291–1298. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.27.6.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vitela M, Mifflin SW. Gamma-Aminobutyric acid (B) receptor-mediated responses in the nucleus tractus solitarius are altered in acute and chronic hypertension. Hypertension. 2001;37:619–622. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.2.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mei L, Zhang J, Mifflin S. Hypertension alters GABA receptor-mediated inhibition of neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract. American journal of physiology. 2003;285:R1276–1286. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00255.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mendelowitz D, Yang M, Andresen MC, Kunze DL. Localization and retention in vitro of fluorescently labeled aortic baroreceptor terminals on neurons from the nucleus tractus solitarius. Brain Research. 1992;581:339–343. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90729-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tolstykh G, Belugin S, Tolstykh O, Mifflin SW. Responses to GABA-A receptor activation are altered in NTS neurons isolated from renal-wrap hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2003;42:732–736. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000084371.17927.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang W, Herrera-Rosales M, Mifflin SW. Chronic hypertension enhances the postsynaptic effect of baclofen in the nucleus tractus solitarius. Hypertension. 2007;49:659–663. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000253091.82501.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Potts JT, Shi XR, Raven PB. Carotid baroreflex responsiveness during dynamic exercise in humans. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:H1928–1938. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.265.6.H1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Potts JT. Inhibitory neurotransmission in the nucleus tractus solitarii: implications for baroreflex resetting during exercise. Exp Physiol. 2006;91:59–72. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2005.032227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Potts JT, Fong AY, Anguelov PI, Lee SC, McGovern D, Grias I. Targeted deletion of Neurokinin-1 receptor expressing nucleus tractus solitarii neurons precludes somatosensory depression of arterial baroreceptor-heart rate reflex. Neuroscience. 2007;145:1168–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mifflin SW. What does the brain know about blood pressure? News in Physiol Sci. 2001;16:266–271. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.2001.16.6.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kenney MJ, Seals DR. Postexercise hypotension. Key features, mechanisms, and clinical significance. Hypertension. 1993;22:653–664. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.22.5.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen CY, Bechtold AG, Tabor J, Bonham AC. Exercise reduces GABA synaptic input to nucleus tractus soliatrii baroreceptor second-order neurons via NK1 receptor internalization in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Neuroscience. 2009;29:2754–2761. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4413-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hermes SM, Mitchell JL, Silverman MB, Lynch PJ, McKee BL, Bailey TW, Andresen MC, Aicher SA. Sustained hypertension increases the density of AMPA receptor subunit, GluR1, in baroreceptive regions of the nucleus tractus solitarii of the rat. Brain Research. 2008;1187:125–136. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.10.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saha S, Spary EJ, Maqbool A, Asipu A, Corbett EKA, Batten TF. Increased expression of AMPA receptor subunits in the nucleus of the solitary tract in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Mol Br Res. 2004;121:37–49. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Belugin S, Mifflin S. Transient voltage-dependent potassium currents are reduced in NTS neurons isolated from renal wrap hypertensive rats. Journal of neurophysiology. 2005;94:3849–3859. doi: 10.1152/jn.00573.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sundaram K, Johnson SM, Felder RB. Altered expression of delayed excitation in medial NTS neurons of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Neurosci Lett. 1997;225:205–209. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00214-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bailey TW, Hermes SM, Whittier KL, Aicher SA, Andresen MC. A-type potassium channels differentially tune afferent pathways from rat solitary tract nucleus to caudal ventrolateral medulla or paraventricular hypothalamus. The Journal of physiology. 2007;582:613–628. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.132365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tolstykh G, de Paula PM, Mifflin S. Voltage-dependent calcium currents are enhanced in nucleus of the solitary tract neurons isolated from renal wrap hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2007;49:1163–1169. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.106.084004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stelzer A, Shi H. Impairment of GABA-A receptor function by N-methyl-D-aspartate-mediated calcium influx in isolated CA1 pyramidal cells. Neurosci. 1994;62:813–828. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90479-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inoue M, Oomura Y, Yakushiji T, Akaike N. Intracellular calcium ions decrease the affinity of the GABA receptor. Nature. 1986;324:156–158. doi: 10.1038/324156a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Durgam VR, Vitela M, Mifflin SW. Enhanced gamma-aminobutyric acid-B receptor agonist responses and mRNA within the nucleus of the solitary tract in hypertension. Hypertension. 1999;33:530–536. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.1.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh R, Ticku MK. Comparison of [3H]baclofen binding to GABA-B receptors in spontaneously hypertensive and normotensive rats. Brain Research. 1985;358:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90941-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones JV, Thoren PN. Characteristics of aortic baroreceptors with non-medullated afferents arising from the aortic arch of rabbits with chronic renovascular hypertension. Acta Physiol Scand. 1977;101:286–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1977.tb06010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang J, Mifflin SW. Integration of aortic nerve inputs in hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2000;35:430–436. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.1.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vargas KJ, Terunuma M, Tello JA, Pangalos MN, Moss SJ, Couve A. The availability of surface GABA B receptors is independent of gamma-aminobutyric acid but controlled by glutamate in central neurons. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:24641–24648. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802419200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilkins ME, Li X, Smart TG. Tracking cell surface GABAB receptors using an alpha-bungarotoxin tag. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283:34745–34752. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803197200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fairfax BP, Pitcher JA, Scott MG, Calver AR, Pangalos MN, Moss SJ, Couve A. Phosphorylation and chronic agonist treatment atypically modulate GABAB receptor cell surface stability. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:12565–12573. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311389200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Belugin S, Mifflin SW. Transient voltage-dependent potassium currents are reduced in NTS neurons isolated from renal wrap hypertensive rats. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94:3849–3859. doi: 10.1152/jn.00573.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cunningham JT, Herrera-Rosales M, Martinez MA, Mifflin SW. Identification of active central nervous system sites in renal wrap hypertension. Hypertension. 2007;49:653–658. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000254481.94570.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dampney RA, Polson JW, Potts PD, Hirooka Y, Horiuchi J. Functional organization of brain pathways subserving the baroreceptor reflex: studies in conscious animals using immediate early gene expression. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2003:597–616. doi: 10.1023/A:1025080314925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sumners C, Zhu M, Gelband CH, Posner P. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor modulation of neuronal K+ and Ca2+ currents: intracellular mechanisms. The American Journal of Physiology. 1996;271:C154–163. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.1.C154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paton JF, Waki H, Kasparov S. In vivo gene transfer to dissect neuronal mechanisms regulating cardiorespiratory function. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2003;81:311–316. doi: 10.1139/y03-028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yao F, Sumners C, O'Rourke ST, Sun C. Angiotensin II increases GABAB receptor expression in nucleus tractus solitarii of rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H2712–2720. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00729.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Siragy HM, Carey RM. Protective role of the angiotensin AT2 receptor in a renal wrap hypertension model. Hypertension. 1999;33:1237–1242. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.5.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang W, Herrera-Rosales M, Mifflin S. Chronic hypertension enhances the postsynaptic effect of baclofen in the nucleus tractus solitarius. Hypertension. 2007;49:659–663. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000253091.82501.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mei L, Zhang J, Mifflin SW. Hypertension alters GABA receptor mediated inhibition of neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract. Am J Physiol (Reg Int Comp) 2003;285:R1276–R1286. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00255.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tolstykh G, De Paula PM, Mifflin SW. Voltage-dependent calcium currents are enhanced in nucleus of the solitary tract neurons isolated from renal wrap hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2007;49:1163–1169. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.106.084004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Head GA, Minami N. Importance of cardiac, but not vascular, hypertrophy in the cardiac baroreflex deficit in spontaneously hypertensive and stroke-prone rats. Am J Med. 1992;92:54S–59S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(92)90148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ricksten SE, Noresson E, Thoren P. Inhibition of renal sympathetic nerve traffic from cardiac receptors in normotensive and spontaneously hypertensive rats. Acta Physiol Scand. 1979;106:17–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1979.tb06364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schultz HD, Li YL, Ding Y. Arterial chemoreceptors and sympathetic nerve activity. Implications for hypertension and heart failure. Hypertension. 2007;50:6–13. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.106.076083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Park JB, Jo JY, Zheng H, Patel KP, Stern JE. Regulation of tonic GABA inhibitory function, presympathetic neuronal activity and sympathetic outflow from the paraventricular nucleus by astroglial GABA transporters. J Physiol. 2009;587:4645–4660. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.173435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun MK, Guyenet PG. Medullospinal sympathoexcitatory neurons in normotensive and spontaneously hypertensive rats. American Journal of Physiology. 1986;250:R910–R917. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1986.250.5.R910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Haywood JR, Mifflin SW, Craig T, Calderon A, Hensler JG, Hinojosa-Laborde C. γ–Aminobutyric Acid (GABA)-A function and binding in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus in chronic renal-wrap hypertension. Hypertension. 2001;37:614–618. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.2.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.VanNess JM, Hinojosa-Laborde C, Craig T, Haywood JR. Effect of sinoaortic deafferentation on renal wrap hypertension. Hypertension. 1999;33:476–481. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.1.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Parati G, Mancia G. Blood pressure variability as a risk factor. Blood Press Monit. 2001;6:341–347. doi: 10.1097/00126097-200112000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Su DF, Miao CY. Blood pressure variability and organ damage. Clin & Exp Pharmacol & Physiol. 2001;28:709–715. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2001.03508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pringle E, Phillips C, Thijs L, Davidson C, Staessen JA, de Leeuw PW, Jaaskivi M, Nacheve C, Parati G, O'Brien ET, Tuomilehto J, Webster J, Bulpitt CJ, Fagard RH. Systolic blood pressure variability as a risk factor for stroke and cardiovascular mortality in the elderly hypertensive population. J Hypertens. 2003;21:2251–2257. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200312000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kario K. Blood Pressure Variability in Hypertension: A Possible Cardiovascular Risk Factor. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17:1075–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mussalo H, Vanninen E, Ikaheimo R, Laitinen T, Hartikainen J. Short-term blood pressure variability in renovascular hypertension and in severe and mild essential hypertension. Clin Sci. 2003;105:609–614. doi: 10.1042/CS20020268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Parati G. Blood pressure variability, target organ damage and antihypertensive treatment. J Hypertens. 2003;21:1827–1830. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200310000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Parati G. Blood pressure variability and cardiovascular control mechanisms in hypertension. Clin Sci. 2003;105:545–547. doi: 10.1042/CS20030256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mancia G, Parati G, Hennigc M, Flatauc B, Ombonib S, Glavinab F, Costad B, Scherze R, Bondf G, Zanchetti A. Relation between blood pressure variability and carotid artery damage in hypertension: baseline data from the European Lacidipine Study on Atherosclerosis (ELSA) J Hypertens. 2001;19:1981–1989. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200111000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gomez-Angelats E, de la Sierra A, Sierra C, Parati G, Mancia G, Coca A. Blood pressure variability and silent cerebral damage in essential hypertension. Am Heart J. 2004;17:696–700. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Durgam VR, Mifflin SW. Comparative analysis of multiple receptor subunit mRNA in micropunches obtained from different brain regions using a competitive RT-PCR method. J Neurosci Methods. 1998;84:33–40. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(98)00081-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]