Abstract

The immune-enhancing effects of selenium (Se) supplementation make it a promising complementary and alternative medicine modality for boosting immunity, although mechanisms by which Se influences immunity are unclear. Mice fed low (0.08 mg/kg), medium (0.25 mg/kg), or high (1.0 mg/kg) Se diets for 8 wk were challenged with peptide/adjuvant. Antigen-specific CD4+ T cell responses were increased in the high Se group compared with the low and medium Se groups. T cell receptor signaling in ex vivo CD4+ T cells increased with increasing dietary Se, with all 3 groups differing from one another in terms of calcium mobilization, oxidative burst, translocation of nuclear factor of activated T cells, and proliferation. The high Se diet increased expression of interleukin (IL)-2 and the high affinity chain of the IL-2 receptor compared with the low and medium Se diets. The high Se diet skewed the T helper (Th)1/Th2 balance toward a Th1 phenotype, leading to higher interferon-γ and CD40 ligand levels compared with the low and medium Se diets. Prior to CD4+ T cell activation, levels of reactive oxygen species did not differ among the groups, but the low Se diet decreased free thiols compared with the medium and high Se diets. Addition of exogenous free thiols eliminated differences in CD4+ T cell activation among the dietary groups. Overall, these data suggest that dietary Se levels modulate free thiol levels and specific signaling events during CD4+ T cell activation, which influence their proliferation and differentiation.

Introduction

Selenium (Se) is a nutritional trace mineral essential for various aspects of human health (1). The biological effects of Se are mainly exerted through its incorporation into selenoproteins as the amino acid, selenocysteine. Twenty-five selenoproteins have been identified in humans, all but one of which exist as selenocysteine-containing proteins in mice and rats (2). Several members of the selenoprotein family exhibit antioxidant or redox functions, including the glutathione peroxidases (GPx17 through 4) and thioredoxin reductases (Trxrd1, 2, and 3) (3). Several of these and other selenoproteins have been shown to be expressed in nearly all tissues and cell types, including those involved in innate and adaptive immune responses (4–6). Thus, it is not surprising that levels of Se intake have been shown to affect immune responses (7).

Data from experimental animal studies as well as limited human studies have demonstrated that Se deficiency results in less robust immune responses to vaccinations and infections compared with Se-adequate controls (8–10). The influence of host Se status on resistance to infectious agents such as viruses, bacteria, parasites, and fungi depends on the microorganism involved (7,11). Our laboratory recently used a mouse model of allergic airway inflammation to investigate how levels of dietary Se affected the development of this T helper (Th)2-driven immune response (12). Interestingly, Se intake was not related to the development of allergic airway inflammation in a simple dose-response manner. In particular, low levels of dietary Se resulted in low levels of allergic responses, which is consistent with results by others showing that several different types of immune responses are decreased in individuals with low Se status (13). However, supplementing diets with Se at levels higher than Se-adequate diets resulted in lower Th2-driven responses. Comparing these results to those involving viruses (14–17) and intracellular pathogens (18,19) suggests that Se supplementation may affect Th1 and Th2 responses differently. The notion that Se polarizes immunity during the activation of naïve Th cells may help explain studies showing that Se exerts differential influences on various types of immune responses (7,20).

Redox tone has been shown to play a key role in modulating the activation of T cells into effectors (21–23), and selenoproteins regulate redox tone. Despite the crucial role that CD4+ T cells play in initiating immune responses, there is a lack of information available regarding the direct effects of Se levels on these cells. A recent study demonstrated that a complete lack of selenoproteins in T cells led to decreased pools of mature T cells and defective T cell activation (24). Complete depletion of selenoproteins is physiologically improbable even under conditions of very low Se intake and questions remain regarding how less overt changes in Se status affect T cell biology. We examined the effects of Se intake on the activation of CD4+ T cells in terms of proliferation and differentiation.

Materials and Methods

Mice and diets.

C57BL/6 mice purchased from Jackson Laboratory were fed standard diets containing 0.2–0.25 mg/kg Se. At the time of weaning (3–4 wk of age), males were fed Open Source Diets purchased from Research Diets containing either 0.08 mg/kg (cat. no. D19101), 0.25 mg/kg (cat. no. D10001), or 1.0 mg/kg (cat. no. D05050403) Se. These diets were formulated with purified ingredients (Supplemental Table 1) and contained 20.3% protein, 66% carbohydrate, and 5% fat. The protein source was casein, which was also the main source of Se in the low Se diet. For medium and high Se diets, sodium selenite was added to achieve final Se levels. Each lot was independently tested to confirm the Se concentration by inductively coupled plasma-MS (Bodycote) with lot-to-lot variation at or below the detection limit of inductively coupled plasma-MS testing (0.02 mg/kg). Mice were fed the special diets for 8 wk prior to isolation of CD4+ T cells from spleens. To ensure that the different Se diets were not altering their overall health, mice were monitored for indicators of general health, including body weight (measured 8 wk after weaning), coat appearance, and general grooming. All animal experimental protocols were approved by the University of Hawaii Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Antibodies and reagents.

Antibodies used for flow cytometry included allophycocyanin (APC)-anti-CD4 and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-anti-CD4, FITC-anti-CD3, phycoerythrin (PE)-anti-CD40L and APC-anti-CD40L, PE-anti-CD44, PE/cyanine 5 (Cy5)-anti-CD16/32, PE/Cy5-anti-CD19, and anti-CD25 (eBioscience). Stimulation of CD4+ T cells was carried out with anti-CD4 (L3T4) (eBioscience) and anti-CD28 (37.51) (BioLegend). Propidium iodide (Ebioscience) was used for live cell determination. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis (LCMV) gp66–77 (DIYKGVYQFKSV) peptide was purchased from Peptide 2.0 and APC-conjugated I-A(b) tetramer preconjugated with LCMV gp66–77 was obtained by the NIH Tetramer Facility. All antibodies and reagents listed above were used at final concentrations recommended by manufacturers. N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC) and 2-mercaptoethanol were both purchased from Sigma.

In vivo antigen challenge.

To induce CD4+ T cell immune responses, an established protocol was followed (25) with modifications. Briefly, 50 μg LCMV gp66–77 peptide in 200 μL of a vaccine adjuvant comprised of cationic liposomes and noncoding plasmid DNA (CLDC) was injected intraperitoneally at d 0 and 12. Five days later, spleens were removed and 2 × 106 cells were stained with APC-conjugated tetramer for 2.5 h at 37°C. For the last 30 min of this incubation, a cocktail of surface-staining antibodies was added, including FITC-anti-CD4 plus PE-anti-CD44 to detect activated, antigen-specific T cells, and PE-Cy5-anti-CD16/32, PE-Cy5-anti-CD19, and propidium iodide detected in FL-3 to eliminate nonspecifically bound tetramer (dump channel). Four-color flow cytometry was performed on a FACScaliber to enumerate antigen-specific T cells.

Purification of ex vivo CD4+ T cells.

Spleens were removed from mice in a sterile hood and cell suspensions were prepared as previously described (25). A negative-selection CD4+ T cell isolation kit (Miltenyi) was used to purify untouched CD4+ T cells per the manufacturer's instructions and cells were resuspended in RPMI with 10% mouse sera pooled from mice in the same dietary Se group. Purity of cells was determined by evaluation of CD3+CD4+ via flow cytometry on a FACScaliber (BD Biosciences) and consistently ≥95%.

Calcium mobilization and proliferation assays.

Established techniques were used to assay for Ca2+ mobilization (26,27) with slight modifications. In brief, purified CD4+ T cells (5 × 109 cells/L) were loaded with 2 mg/L fluo-3 AM (Invitrogen) in 0.5% pluronic acid for 30 min followed by 2 washes in RPMI with 10% fetal bovine serum. Cells (1010/L) were recovered at 37°C for 30 min and in some cases media contained 50 μmol/L 2-mercaptoethanol or 10 mmol/L NAC, commonly used sources of exogenous free thiols (28). The cells were then analyzed with a FACScaliber for fluorescence 1–2 min to determine baseline Ca2+ levels. After this initial period, the cells were stimulated using soluble hamster anti-CD3 (10 mg/L) and mouse anti-hamster (20 mg/L) and cytofluorometric analysis resumed for another 4–8 min. Ionomycin (Sigma) was added at a final concentration of 500 μg/L to determine equivalent loading of cells with fluo-3 AM. Proliferation was measured using 3H-thymidine techniques previously described (24) and levels of isotope incorporated into DNA were measured using a Packard Bioscience/Perkin Elmer Tri-Carb 2900TR liquid scintillation counter. In some proliferation experiments, NAC was included in the culture media at a final concentration of 0.5 mmol/L.

Reactive oxygen species, glutathione, and free thiol measurement.

For reactive oxygen species (ROS) measurement, purified CD4+ T cells (1010 cells/L) in complete RPMI media were incubated with anti-CD3 (10 mg/L) on ice for 30 min. At 15 min prior to flow cytometric analysis, cells were loaded with 2 μmol/L 5-(and 6 -) chloromethyl-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate, acetyl ester (Invitrogen) in prewarmed (37°C) PBS containing 5 mg/L cross-linking anti-hamster antibody. Reactions were terminated by adding 4.5 mL ice-cold fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) buffer (PBS with 2% fetal bovine serum). Cells were pelleted and washed once with 3 mL ice-cold FACS buffer, resuspended in FACS buffer, and analyzed on a FACScaliber. For free thiol measurement, equivalent numbers of unstimulated CD4+ T cells from each dietary group were lysed with Mammalian Cell Lytic buffer (Sigma) with no reducing agent added, and lysates were analyzed using a DetectX Thiol Detection kit (Arbor Assays) and a Victor II fluorimeter (Perkin Elmer). Glutathione (GSH) levels were spectrophotometrically measured using a OxisResearch Total GSH kit. The readouts for total thiol and GSH were normalized to total protein as measured by the Bradford assay.

Enzyme activity and nuclear factor of activated T cells translocation assays.

Erythrocytes were lysed in 200 μL dH2O and analyzed with plasma for GPx activity using Bioxytech GPx-340 kit (OxisResearch) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For GPx and Trxrd assays involving CD4+ T cell lysates, protein was extracted from cells using CellLytic MT buffer (Sigma) and GPx assay carried out as described above and Trxrd assay using Thioredoxin Reductase Assay kit (Sigma). For nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) translocation, purified CD4+ T cells (5 × 105 cells/well) were added to CD3/CD28 (10/5 mg/L) precoated coverslips in 500 μL complete RPMI media and incubated at 37°C for 10 min. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained for NFAT (anti-NFAT followed by 488-secondary antibody) and nuclei (Hoeschst) using an NFAT Activation kit (Thermo Scientific). Cells were analyzed by fluorescent microscopy for colocalization of green and blue fluorescence using Image-J software (NIH).

Real-time PCR and flow cytometry.

Total RNA was extracted and real-time PCR carried out as previously described (29). Oligonucleotides used for real-time PCR included mIL2 (fwd: 5′-gct gtt gat gga cct aca gga-3′; rev: 5′-ttc aat tct gtg gcc tgc tt-3′) and mCD25 (fwd: 5′-cca aca cag tct atg cac caa-3′; rev: 5′-aga ttc tct tgg aat ctt cat gtt c-3′). Also, proprietary primers were purchased from SuperArray Biosciences for interleukin (IL)-4 (cat. no. PPM03013E) and interferon (IFN)γ (cat. no. PPM03121A). Flow cytometric analyses for surface markers were performed as previously described (12).

Statistical analyses.

All statistical tests for comparison of means were performed using GraphPad Prism version 4.0. A 1-way ANOVA was used to determine effect of diet on outcomes for T cell receptor (TCR)-stimulated cells with Tukey post test used to compare means of dietary groups. For the experiment involving exogenous free thiols and proliferation, a 2-way ANOVA was used to test the main effects of diet and exogenous free thiols on proliferation. In addition, interactions between diet and exogenous free thiols on proliferation were analyzed. Bonferroni's post hoc test was used to identify the means that differed. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05. GraphPad Prism was also used for linear and nonlinear regression analyses for curve-fitting.

Results

High dietary Se increases CD4+ T cell responses.

As expected with the chosen Se levels, the dietary groups did not differ in general health, lymphoid tissue development, or T cell populations in lymphoid and nonlymphoid tissues (data not shown). The diets had the desired effects in establishing low, medium, and high Se status in the mice as determined by GPx activity in erythrocytes and plasma (Fig. 1A,B). CD4+ T cells were purified from spleens and GPx and Trxrd enzymatic activities were measured. GPx activity was significantly lower in cells from the low Se group compared with cells from the medium and high Se groups (Fig. 1C). Trxrd activity was significantly higher in cells from the high Se group compared with cells from the low and medium Se groups (Fig. 1D). CD4+ T cell responses to in vivo antigenic challenge were greater in the high Se group compared with the low and medium Se groups (Fig. 1E).

FIGURE 1 .

Selenoenzyme activity in erythrocytes (A), plasma (B), and CD4+ T cells (C,D), and in vivo CD4+ T cell responses (E) in mice fed low, medium, or high Se diets for 8 wk. Values are means + SE, n = 3 (A–D) and 10 (E). For all graphs, means without a common letter differ, P < 0.05.

Dietary Se increases Ca2+ mobilization, oxidative burst, and NFAT translocation.

We next examined the effects of Se on CD4+ T cell activation by focusing on an early cell signaling event that occurs within seconds of TCR stimulation: Ca2+ mobilization. TCR-induced Ca2+ mobilization increased with increasing dietary Se, with all 3 groups differing from one another (Fig. 2A). There were no differences in Ca2+ mobilization when cells were treated with the Ca2+ ionophore, ionomycin, suggesting TCR signaling was specifically affected by Se levels and Se was not having a general effect on plasma membrane Ca2+ flux (data not shown).

FIGURE 2 .

TCR signal strength as determined by Ca2+ flux (A), oxidative burst (B), and NFAT translocation (C) in CD4+ T cells from mice fed low, medium, or high Se diets for 8 wk. (A) For each dietary group, cells were pooled from 3 mice and results represent 3 independent experiments. (B,C) Values are means + SE, n = 3. For all graphs, means without a common letter differ, P < 0.05.

A time-course experiment was performed to measure TCR-stimulated oxidative burst. ROS levels increased with increasing dietary Se, with all groups differing significantly from one another at 45 min post-TCR stimulation (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, there were no differences in ROS prior to TCR stimulation despite results showing that increasing dietary Se increased antioxidant selenoenzyme activity in CD4+ T cells (Fig. 1).

A crucial signaling event downstream of Ca2+ mobilization, NFAT, was evaluated. NFAT translocation increased with increasing dietary Se, with all groups differing significantly from one another (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, TCR-induced phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase was not affected by dietary Se levels (data not shown).

Se levels influence IL-2 transcription, IL-2 receptor expression, and proliferation.

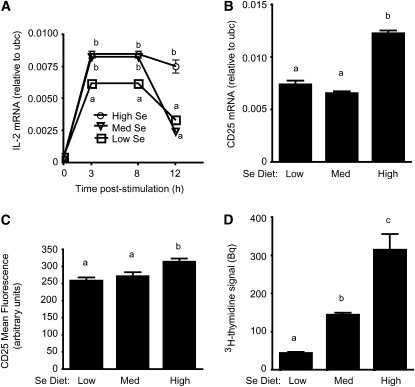

A time-course experiment was performed to evaluate IL-2 mRNA levels in CD4+ T cells after activation through TCR engagement (Fig. 3A). IL-2 mRNA was higher in the cells from the medium and high Se groups compared with cells from the low Se group from 3–8 h poststimulation. IL-2 mRNA was higher in cells from the high Se group compared with cells from the low or medium Se groups at 12 h poststimulation.

FIGURE 3 .

IL-2 mRNA (A), CD25 mRNA (B), CD25 surface expression (C), and cell proliferation (D) for TCR-stimulated CD4+ T cells from mice fed low, medium, or high Se diets for 8 wk. Values are means + SE, n = 3 (A,B,D) and 5 (C). For A, means at each time point without a common letter differ, P < 0.05. For B–D, means without a common letter differ, P < 0.05.

Levels of mRNA for CD25, the high-affinity chain of the IL-2 receptor (IL-2R), were examined at 12 h poststimulation. CD25 mRNA was higher in cells from the high Se group compared with cells from the low and medium Se groups (Fig. 3B). Surface expression of CD25 on TCR-stimulated CD4+ T cells was higher in cells from the high Se group compared with cells from the low and medium Se groups. (Fig. 3C). Given that the high Se diet increased expression of both IL-2 and the high affinity IL-2R chain and that interactions between IL-2 and IL-2R drive proliferation of T cells (30), we examined the effects of increasing Se intake on the proliferative capacity of CD4+ T cells. Proliferation increased with increasing dietary Se, with all groups differing significantly from one another (Fig. 3D). Levels of CD25 mRNA, CD25 surface expression, and proliferation did not differ in unstimulated cells from the 3 dietary Se groups (data not shown).

Se levels affect CD4+ T cell differentiation.

Increasing Se intake affects various types of immune responses differently and the differentiation of CD4+ T cells plays a central role in shaping immune responses (7). Thus, we evaluated TCR-stimulated CD4+ T cells for mRNA levels for the Th1 and Th2 cytokines, IFNγ and IL-4, respectively. IFNγ mRNA increased with increasing dietary Se, with all groups differing significantly from one another at 12 h post-TCR stimulation (Fig. 4A). In contrast, IL-4 mRNA was higher in cells from the low Se group at 3–8 h post-TCR stimulation compared with cells from the medium and high Se groups (Fig. 4B). Surface expression of CD40L, a molecule important for differentiation of Th1 effectors, was measured on TCR-stimulated CD4+ T cells. CD40L expression was higher on cells from the high Se group compared with cells from the low and medium Se groups (Fig. 4B). CD40L surface expression did not differ on unstimulated cells from the 3 dietary Se groups (data not shown).

FIGURE 4 .

IFNγ mRNA (A), IL-4 mRNA (B), and surface expression of CD40L (C) for TCR-stimulated CD4+ T cells from mice fed low, medium, or high Se diets for 8 wk. Values are means + SE, n = 3 (A,B) and 5 (C,D). For A and B, means at each time point without a common letter differ, P < 0.05. For B–D, means without a common letter differ, P < 0.05.

Se influences T cell activation through modulation of free thiol levels.

To determine cellular redox tone, free thiol groups (-SH groups arising under more reduced conditions, i.e. lower oxidative stress) were measured in freshly isolated CD4+ T cells. Free thiol levels were lower in cells from the low Se group compared with cells from the medium and high Se groups, which did not differ significantly from one another (Fig. 5A). Because GSH is a major intracellular thiol, GSH levels were measured in CD4+ T cells. GSH levels were lower in cells from the low Se group compared with cells from the medium and high Se groups, which did not differ from one another (Fig. 5B). To determine whether dietary Se affected T cell activation through a mechanism involving free thiols, we repeated the experiments from above with and without the addition of exogenous free thiols in the form of NAC. The addition of NAC eliminated the effects of dietary Se on proliferation (Fig. 5C). NAC did not affect proliferation in unstimulated CD4+ T cells (data not shown). The addition of exogenous free thiols also eliminated the effects of dietary Se on Ca2+ flux (Supplemental Fig. 1).

FIGURE 5 .

Free thiols (A) and GSH levels (B) and effects of exogenous free thiols on TCR-induced proliferation (C) for CD4+ T cells from mice fed low, medium, or high Se diets for 8 wk. Values are the mean + SE, n = 3 (A,B). Means without a common letter differ, P < 0.05. For C, values are the mean + SE, n = 11. P-values from the 2-way ANOVA were: diet, P < 0.001; NAC, P < 0.001; interaction, P < 0.001. Means without a common letter differ, P < 0.05.

Discussion

The data presented in this study demonstrate that TCR signal strength in CD4+ T cells is increased by Se intake, affecting their proliferation and differentiation. For several different measurements of TCR-induced activation, low dietary Se resulted in weak T cell activation. While several other studies have used tortula-based diets containing <0.02 mg/kg Se to severely deplete selenoprotein activity in rodents (19,31,32), the low Se diet (0.08 mg/kg) used in the present study was marginally lower than the nutritional requirement for rodents (0.1 mg/kg) (33). This level was chosen to reflect moderately low Se intake in a diet consumed by humans, with selenite added to increase Se intake to medium and high Se levels (34,35). Although CD4+ T cells are not the only type of immune cell detrimentally affected by low Se levels (11,36,37), they play a crucial role in driving a variety of different immune responses. The dramatic effects of low Se intake on CD4+ T cells in terms of weak TCR signals and reduced proliferation highlight the importance of acquiring sufficient levels of dietary Se for properly functioning Th cells.

In addition to increasing TCR signal strength, our data suggest that Se intake influences differentiation of CD4+ T cells into Th1 compared with Th2 effector cells. Increasing dietary Se may shift intracellular redox status toward a more reduced state and induce a bias toward Th1 effector cells. This would benefit antiviral immune or antitumor responses that depend on robust Th1 immunity (12). The notion that Se increases Th1 responses is consistent with studies showing higher dietary Se levels led to an increasing ability to generate CTL and to destroy tumor cells in mice (38). In contrast, Se supplementation and decreased oxidative stress may decrease Th2 responses such as those that drive allergic asthma and this notion is consistent with our previously published data (12). Particularly interesting was the effect of increasing Se intake on the expression of CD40L, an accessory molecule that plays a key role in driving the differentiation process (39–41). The effect of redox status on expression of CD40L or other accessory molecules involved in Th1:Th2 polarization is an understudied area that warrants further investigation.

Dietary Se has long been considered a potent antioxidant and our data suggest that higher Se intake increases TCR signal strength through mechanisms that involve free thiol concentrations. Early signaling events like Ca2+ flux and NFAT translocation were increased by increased Se intake, but dietary Se did not affect phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase levels, which is consistent with other data suggesting no influence of oxidative stress on this particular signaling event (26). Interestingly, higher Se status increased TCR-induced oxidative burst in activated CD4+ T cells, despite the increased selenoenzyme activity resulting from higher dietary Se in these cells. Higher enzymatic activity of GPx1, Trxrd1, and other antioxidant selenoproteins in CD4+ T cells from Se-supplemented individuals may serve to rapidly quench the augmented ROS and mitigate cellular damage that unchecked higher ROS may cause. Also, the differences in free thiols in CD4+ T cells from the 3 dietary Se groups were small compared with differences in proliferation. This suggests that small differences in free thiols prior to stimulation may become increasingly important for redox tone during the exponential expansion of these cells. Although Se and selenoproteins have been shown to have direct effects on cellular redox status (3), it remains unclear whether selenoproteins act directly on the cell signals during T cell activation or in a more indirect manner through regulation of cellular redox tone.

Extreme Se deficiency in humans is rare except in particular regions in China and Russia (42). Results of the NHANES III-1988–94 indicated that most Americans' diets provide the recommended levels of Se. However, Se supplementation (200 μg/d) may improve immune responses to cold or flu viruses or may augment vaccine responses to a variety of infectious diseases. In addition, Se supplementation may improve health by reversing declining immunity associated with aging and the immunosuppression associated with cancer, its treatment, and with HIV/AIDS. The data in the present study demonstrated that CD4+ T cells from mice fed high Se diets exhibited enhanced TCR signaling and in vivo responses compared with cells from mice fed medium Se diets. However, the immune-enhancing effects of Se supplementation must be considered with its other effects, as highlighted from a recently discontinued study involving Se supplementation and cancer prevention, the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (43). Understanding the mechanisms by which dietary Se affects the immune system, such as modulation of free thiols in Th cells, may lead to better utilization of Se supplementation as a means of enhancing Th1 immunity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Xiaosha Pang and Allyson Fukuyama for assistance with experiments. F.W.H., M.J.B., and P.R.H. designed research; F.W.H. and P.R.H. conducted research; S.D. designed and supplied specialized adjuvants; A.C.H. performed all animal husbandry; L.A.S. assisted with biostatistical analyses; F.W.H. and P.R.H. wrote the paper. P.R.H. had primary responsibility for final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supported by award number R21AT004844 from the National Center For Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NCCAM or the NIH. The work was also supported by NIH grants G12RR003061 and P20RR016453. NIH Tetramer facility provided APC-conjugated I-A(b)-LCMV gp66-77.

Author disclosures: F. W. Hoffmann, A. C. Hashimoto, L. A. Shafer, S. Dow, M. J. Berry, and P. R. Hoffman, no conflicts of interests for any of the authors.

Supplemental Table 1 and Figure 1 are available with the online posting of this paper at jn.nutrition.org.

Abbreviations used: APC, allophycocyanin; Cy5, cyanine 5; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; GPx, glutathione peroxidase; GSH, glutathione; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; IL-2R, interleukin-2 receptor; LCMV, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus; NAC, N-acetyl-cysteine; NFAT, nuclear factor of activated T cell; PE, phycoerythrin; ROS, reactive oxygen species; TCR, T cell receptor; Th, T helper; Trxrd, thioredoxin reductase.

References

- 1.Rayman MP. The importance of selenium to human health. Lancet. 2000;356:233–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kryukov GV, Castellano S, Novoselov SV, Lobanov AV, Zehtab O, Guigo R, Gladyshev VN. Characterization of mammalian selenoproteomes. Science. 2003;300:1439–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reeves MA, Hoffmann PR. The human selenoproteome: recent insights into functions and regulation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:2457–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gromer S, Eubel JK, Lee BL, Jacob J. Human selenoproteins at a glance. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:2414–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Behne D, Wolters W. Distribution of selenium and glutathione peroxidase in the rat. J Nutr. 1983;113:456–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bainbridge DR. Use of (75Se)L-selenomethionine as a label for lymphoid cells. Immunology. 1976;30:135–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffmann PR, Berry MJ. The influence of selenium on immune responses. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2008;52:1273–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mulhern SA, Taylor LE, Magruder LE, Vessey AR. Deficient levels of dietary selenium suppress the antibody response in first and second generation mice. Nutr Res. 1985;5:201–10. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petrie HT, Klassen LW, Klassen PS, O'Dell JR, Kay HD. Selenium and the immune response: 2. Enhancement of murine cytotoxic T-lymphocyte and natural killer cell cytotoxicity in vivo. J Leukoc Biol. 1989;45:215–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roy M, Kiremidjian-Schumacher L, Wishe HI, Cohen MW, Stotzky G. Selenium and immune cell functions. II. Effect on lymphocyte-mediated cytotoxicity. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1990;193:143–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffmann PR. Mechanisms by which selenium influences immune responses. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz). 2007;55:289–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffmann PR, Jourdan-Le Saux C, Hoffmann FW, Chang PS, Bollt O, He Q, Tam EK, Berry MJ. A role for dietary selenium and selenoproteins in allergic airway inflammation. J Immunol. 2007;179:3258–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hawkes WC, Kelley DS, Taylor PC. The effects of dietary selenium on the immune system in healthy men. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2001;81:189–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broome CS, McArdle F, Kyle JA, Andrews F, Lowe NM, Hart CA, Arthur JR, Jackson MJ. An increase in selenium intake improves immune function and poliovirus handling in adults with marginal selenium status. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:154–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beck MA, Levander OA, Handy J. Selenium deficiency and viral infection. J Nutr. 2003;133:S1463–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kupka R, Msamanga GI, Spiegelman D, Morris S, Mugusi F, Hunter DJ, Fawzi WW. Selenium status is associated with accelerated HIV disease progression among HIV-1-infected pregnant women in Tanzania. J Nutr. 2004;134:2556–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stephensen CB, Marquis GS, Douglas SD, Kruzich LA, Wilson CM. Glutathione, glutathione peroxidase, and selenium status in HIV-positive and HIV-negative adolescents and young adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:173–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shor-Posner G, Miguez MJ, Pineda LM, Rodriguez A, Ruiz P, Castillo G, Burbano X, Lecusay R, Baum M. Impact of selenium status on the pathogenesis of mycobacterial disease in HIV-1-infected drug users during the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;29:169–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gomez RM, Solana ME, Levander OA. Host selenium deficiency increases the severity of chronic inflammatory myopathy in Trypanosoma cruzi-inoculated mice. J Parasitol. 2002;88:541–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoffmann PR. Selenium and asthma: a complex relationship. Allergy. 2008;63:854–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Los M, Schenk H, Hexel K, Baeuerle PA, Droge W, Schulze-Osthoff K. IL-2 gene expression and NF-kappa B activation through CD28 requires reactive oxygen production by 5-lipoxygenase. EMBO J. 1995;14:3731–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams MS, Henkart PA. Role of reactive oxygen intermediates in TCR-induced death of T cell blasts and hybridomas. J Immunol. 1996;157:2395–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Devadas S, Zaritskaya L, Rhee SG, Oberley L, Williams MS. Discrete generation of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide by T cell receptor stimulation: selective regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase activation and fas ligand expression. J Exp Med. 2002;195:59–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shrimali RK, Irons RD, Carlson BA, Sano Y, Gladyshev VN, Park JM, Hatfield DL. Selenoproteins mediate T cell immunity through an antioxidant mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:20181–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zaks K, Jordan M, Guth A, Sellins K, Kedl R, Izzo A, Bosio C, Dow S. Efficient immunization and cross-priming by vaccine adjuvants containing TLR3 or TLR9 agonists complexed to cationic liposomes. J Immunol. 2006;176:7335–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cemerski S, Cantagrel A, Van Meerwijk JP, Romagnoli P. Reactive oxygen species differentially affect T cell receptor-signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:19585–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu KQ, Bunnell SC, Gurniak CB, Berg LJ. T cell receptor-initiated calcium release is uncoupled from capacitative calcium entry in Itk-deficient T cells. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1721–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hadzic T, Li L, Cheng N, Walsh SA, Spitz DR, Knudson CM. The role of low molecular weight thiols in T lymphocyte proliferation and IL-2 secretion. J Immunol. 2005;175:7965–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoffmann PR, Hoge SC, Li PA, Hoffmann FW, Hashimoto AC, Berry MJ. The selenoproteome exhibits widely varying, tissue-specific dependence on selenoprotein P for selenium supply. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3963–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leonard WJ, Lin JX. Cytokine receptor signaling pathways. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:877–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knight SA, Sunde RA. Effect of selenium repletion on glutathione peroxidase protein level in rat liver. J Nutr. 1988;118:853–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheng WH, Ho YS, Ross DA, Han Y, Combs GF Jr, Lei XG. Overexpression of cellular glutathione peroxidase does not affect expression of plasma glutathione peroxidase or phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase in mice offered diets adequate or deficient in selenium. J Nutr. 1997;127:675–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.NRC. Dietary selenium intake controls rat plasma selenoprotein P concentration. Nutrient requirements of laboratory animals. 4th ed. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1995.

- 34.Bieri JG. Second report of the ad hoc committee on standards for nutritional studies. J Nutr. 1980;110:1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sunde RA, Evenson JK, Thompson KM, Sachdev SW. Dietary selenium requirements based on glutathione peroxidase-1 activity and mRNA levels and other Se-dependent parameters are not increased by pregnancy and lactation in rats. J Nutr. 2005;135:2144–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim SH, Johnson VJ, Shin TY, Sharma RP. Selenium attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced oxidative stress responses through modulation of p38 MAPK and NF-kappaB signaling pathways. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2004;229:203–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Safir N, Wendel A, Saile R, Chabraoui L. The effect of selenium on immune functions of J774.1 cells. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2003;41:1005–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rayman MP. Selenium in cancer prevention: a review of the evidence and mechanism of action. Proc Nutr Soc. 2005;64:527–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koguchi Y, Thauland TJ, Slifka MK, Parker DC. Preformed CD40 ligand exists in secretory lysosomes in effector and memory CD4+ T cells and is quickly expressed on the cell surface in an antigen-specific manner. Blood. 2007;110:2520–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen AI, McAdam AJ, Buhlmann JE, Scott S, Lupher ML Jr, Greenfield EA, Baum PR, Fanslow WC, Calderhead DM, et al. Ox40-ligand has a critical costimulatory role in dendritic cell:T cell interactions. Immunity. 1999;11:689–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murata K, Ishii N, Takano H, Miura S, Ndhlovu LC, Nose M, Noda T, Sugamura K. Impairment of antigen-presenting cell function in mice lacking expression of OX40 ligand. J Exp Med. 2000;191:365–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou BF, Stamler J, Dennis B, Moag-Stahlberg A, Okuda N, Robertson C, Zhao L, Chan Q, Elliott P. Nutrient intakes of middle-aged men and women in China, Japan, United Kingdom, and United States in the late 1990s: the INTERMAP study. J Hum Hypertens. 2003;17:623–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lippman SM, Klein EA, Goodman PJ, Lucia MS, Thompson IM, Ford LG, Parnes HL, Minasian LM, Gaziano JM, et al. Effect of selenium and vitamin E on risk of prostate cancer and other cancers: the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). JAMA. 2009;301:39–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.