SUMMARY

Listeria monocytogenes is an important pathogen which causes an infection called listeriosis. Because of the high mortality rate (∼30%) associated with listeriosis, and the widespread nature of the organism, it is a major concern for food and water microbiologists since it has been isolated from various types of foods, including seafood, as well as from the aqueous environment. To investigate the prevalence of this pathogen in the Aqaba Gulf (12 sites), Suez Gulf (14 sites) and Red Sea (14 sites), 200 water samples (collected during five sampling cruises in 2004), 40 fresh fish samples and 15 shellfish samples were analysed using the enrichment procedure and selective agar medium. All water samples were also examined for the presence Listeria innocua which was the most common of the Listeria spp. isolated, followed by L. monocytogenes, with a low incidence of the other species. During the whole year, the percentage of Listeria spp. and L. monocytogenes in 200 water samples was 20·5% (41 samples) and 13% (26 samples) respectively. In fresh fish (40 samples) it was 37% (15 samples) and 17·3% (7 samples) and in shellfish (15 samples) 53% (8 samples) and 33% (5 samples) respectively. In water samples, there was an association between the faecal contamination parameters and the presence of the pathogen; however, water salinity, temperature, dissolved oxygen and pH did not influence the occurrence of this bacterium. These results may help in the water-quality evaluation of the coastal environments of these regions.

INTRODUCTION

Listeria monocytogenes has been recognized as a human pathogen since 1929 [1] causing an infection called listeriosis which can be manifested through several different syndromes causing invasive illness. It can cause abortion during pregnancy, human meningitis, infection during the perinatal period, granulomatosis infantiseptica, sepsis, diarrhoea, pyelitis and ‘flu-like’ symptoms. The mortality rate of listeriosis is ∼30% [2].

In the early 1980s scientists recognized Listeria as a foodborne pathogen as human listerosis resulted from consuming food contaminated with this pathogen such as milk and dairy products, meat, poultry, vegetables, salads and seafood [3]. Moreover, L. monocytogenes has a saprophytic life and occurs widely in nature [4]. A variety of animals including domestic farm animals can carry the bacterium [5], and it can survive for long periods in a plant–soil environment [6]. Listeria spp. were isolated from the Mediterranean coast of Egypt, more specifically from the Eastern Harbour of Alexandria [7], while in the United States the bacterium was isolated from the California coast estuarine environment [6]. Scientists have proposed that the pathogen can survive for a long time in a marine environment as it is a salt-tolerant organism [8–10].

In Egypt, the coastal water of Red Sea including the Suez Gulf and the Aqaba Gulf, may be contaminated by domestic and/or industrial sewage/wastes. Thus, the risk of the presence of such a pathogen in these contaminated areas is to be expected. Listeria spp. have been recovered from a variety of seafood [11–13]; in Egypt, they have been isolated from fresh fish [14] as well as from shellfish collected from the Eastern Harbour of Alexandria [7].

This work addresses the incidence of Listeria spp. as well as the faecal pollution bacteria indicators in the coastal marine water of the Aqaba Gulf, Suez Gulf and Red Sea. Testing of seafood, collected from the local markets along the investigated areas, for the presence of the pathogen was another goal of the study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling sites

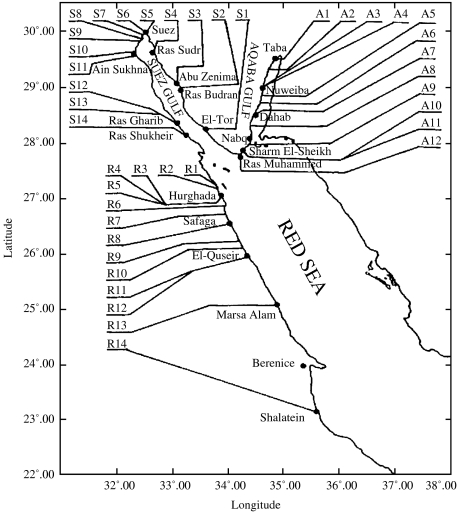

Coastal water samples were collected in five sampling cruises (bi-monthly intervals) during February to October 2004. The sampling sites along the Aqaba Gulf, Suez Gulf and Red Sea are shown in Figure 1. Water was sampled using 1-litre screw-cap bottles, with two sample bottles being taken at the same time/place from each site.

Fig. 1.

Map showing names and codes of sampling locations at Aqaba Gulf (A), Suez Gulf (S) and Red Sea (R).

At each sampling cruise, one fresh fish sample, was purchased from the fish markets of the cities of Nuweiba, Sharm El-Sheikh, Suez, Ras Gharib, Hurghada, Safaga, El-Quseir and Shalatein; one shellfish sample was also purchased, but only from Nuwebia, Suez and Safaga.

All water samples were analysed immediately using an on-site mobile microbiological laboratory. At each sampling site, hydrographical parameters of the water samples including temperature (°C), salinity (‰), dissolved oxygen (mg/l and pH) were measured using CTD (YSI 6000, Yellow Springs, OH, USA). Fish and shellfish samples were collected in plastic bags and kept in the refrigerator of the mobile laboratory and were analysed within 6–12 h.

Bacteriological analysis

Water samples were examined for the presence of faecal pollution indicators of bacteria including total coliforms, E. coli and faecal streptococci using the membrane filtration technique (Gelman 0·45 μm membranes) as described by ISO 9308/1 [15], and ISO 7899/2 [16]. For detection of total coliforms, the membranes were fixed onto m-Endo-LES agar and incubated at 37°C for 24 h; for detection of E. coli, m-FC agar was used followed by incubation at 44·5°C for 24 h; however for faecal streptococci, m-Enterococcus agar was used and incubated at 37°C for 48 h. The biochemical tests used for confirmation of the characteristic colonies as well as calculation of the final bacterial counts, per 100 ml of seawater, were done after the above-mentioned ISO examinations.

For detection of Listeria spp., the enrichment procedure based on the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) technique [17] was used. One litre of each water sample was filtered. More than one membrane was used for each sample when needed. Then, the filter membrane(s) of each sample were scrubbed and manually crushed, using a sterile sharp glass rod, in a 500-ml volume sterile beaker containing 100 ml of Listeria enrichment broth base (LEB) (Oxoid CM 882 broth, Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK) supplemented with Listeria selective supplement (Oxoid SR 141). Membrane suspensions were transferred to sterilized conical flasks and kept at refrigerator temperature (4–8°C) for 4 weeks.

Shellfish, after being scrubbed and rinsed with tap water, were opened aseptically and the flesh was collected. The flesh, or fish samples, were then blended in a sterile grinder to achieve homogenated slurries. Twenty-five grams of each representative slurry was directly suspended in 225 ml of LEB, and kept at refrigerator temperature (4–8°C) for 4 weeks. The refrigerated enrichment cultures were then streaked onto Oxford formula selective agar medium (CM 856) plus Listeria selective supplement (SR 140) as described by Curtis et al. [18]. Plates were incubated at 35°C for 48 h. Up to four colonies that were presumptively positive Listeria, with a black halo and a sunken centre, from each suspected positive plate were picked and purified onto trypticase soy agar (TSA) plates. For identification of the isolates a positive control of L. monocytogenes strain V7 (milk isolate) serotype 1 (obtained from the Department of Food Science, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA) served as a control in this work. This isolate was recovered by all media used in this study. Purified suspected isolates were viewed by the oblique light technique of Henry as described by the IDF [19]. Smears of suspected grey-blue colonies were Gram-stained and examined microscopically after streaking onto TSA plates and incubated at 35°C for 18–24 h. Cultures displaying the correct morphology were tested for catalase, then stabbed into motility test medium (Difco, Detroit, MI, USA) and incubated at 25°C to check for umbrella-shaped growth. Cultures that proved to be motile were tested for haemolysin using tryptose agar with 5% sheep blood. The isolates were streaked onto TSA slants, incubated at 35°C for 18–24 h for further characterization to species using the criteria described by McLauchlin [2].

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

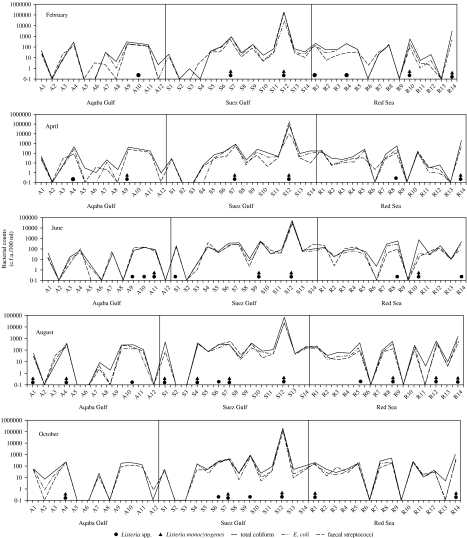

Figure 2 shows the faecal pollution indicators represented as c.f.u./100 ml of the water samples examined during whole year, as well as the prevalence of Listeria spp. in the three studied areas.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of Listeria spp. and counts of faecal bacteria in coastal waters of Aqaba Gulf (A), Suez Gulf (S), and the Red Sea (R) during 2004.

In the Aqaba Gulf area Listeria spp. were detected in 10 out of 60 (17%) samples investigated during the whole year. Five of these contaminated samples (50%) were found to harbour L. monocytogenes. In the Suez Gulf area, 16 out of 70 (23%) samples investigated, proved to be contaminated by Listeria spp. Twelve (75%) of these contaminated samples were found to harbour L. monocytogenes. Along the coastal area of the Red Sea, only 15 out of 70 (21%) samples investigated were contaminated by Listeria spp., where nine (60%) of them harboured L. monocytogenes. These results indicated that Suez Gulf recorded the highest percentage for the presence of the bacterium. This may be due to the drainage of wastes and/or untreated sewage into the Gulf.

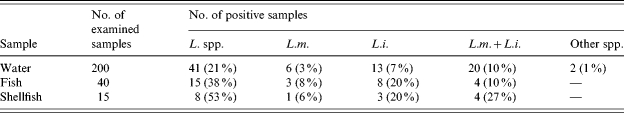

Generally, as illustrated in Table 1, Listeria spp. were detected in 21% (n=41) of the total examined water samples collected from all the investigated areas during the whole year (n=200). This percentage is lower than those reported at the Eastern harbour of Alexandria, where 9 out of 11 (82%), surface water samples were found to harbour Listeria spp. These results are similar to those reported in the United States where the percentage amounted to 33% of the examined marine waters collected from the California coast estuarine environment. Of these contaminated water samples (n=41), 63% (n=26) were found to harbour L. monocytogenes, however, L. innocua was the most predominant of the Listeria spp. since it was found in 80% (n=33) of the contaminated samples. At the same time a small percentage (5%) of other Listeria spp. was also detected (n=2).

Table 1.

Number and percentage of water, fish and shellfish samples positive for Listeria spp.

L. spp., Listeria species; L.m., Listeria monocytogenes; L.i., Listeria innocua; L.m.+L.i., both species together.

In general, in the results obtained, L. innocua was more prevalent than L. monocytogenes, suggesting that it might be a very common organism in the coastal environment. Such an observation should, however, be made with care, since only a few colonies of the pathogen were picked up from the selective plates for identification. In this regard Seeliger [20] reported that L. innocua is a good indicator for L. monocytogenes, thus, when looking for sources of Listeria, the presence of both of these species is equally significant.

The present results indicated that there was an association between the faecal pollution indicators and the presence of the pathogen. As seen in Figure 2, the pathogen was detected in sites with high bacterial counts of the three faecal pollution indicators and never isolated from any site with low counts for these parameters. This association was to be expected since the bacterium is widely distributed in sewage [21] and the numbers of Listeria that are contributed to the environment by sewage and sewage sludge may be higher than those of Salmonella [22].

It should be noted that such an association between the presence of the pathogen and the faecal contamination indicators should not be considered as a general trend, since many factors/relations may interfere, e.g. distribution in water, sediments and biofilms, seasonal variations, total bacterial load, relationship with indicators, etc. At least, our data give preliminary information on the behaviour of Listeria spp. in this coastal environment in an attempt to understand the epidemiology of this pathogen. At the same time, the recorded hydrographical parameters indicated that seasonal variation affected water temperature which ranged between 17·7 and 28·5°C. A range of 39·2–42·6‰ for salinity was, however, recorded; the pH ranged from 7·8 to 8·5 and the dissolved oxygen between 6·3 and 9·5 mg/l. This variation in these hydrographical parameters, during the whole year, did not appear to affect the distribution of Listeria spp. and/or the bacteria of faecal pollution indicators in the investigated sites.

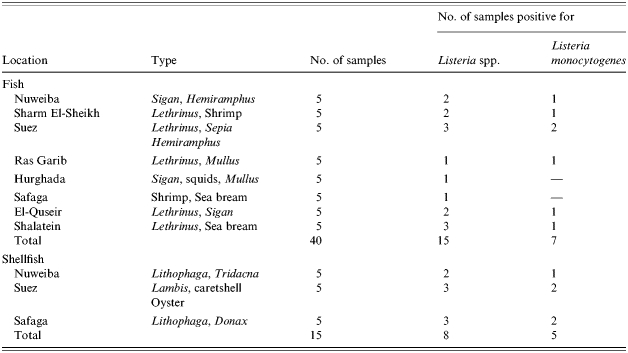

The incidence of Listeria spp. in the examined fish and shellfish samples is summarized in Table 2. As can be seen, L. innocua and L. monocytogenes were the only two species found in the investigated seafood samples. The incidence of Listeria spp. in the positive samples in relation to fish/shellfish type and the location where it was purchased is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Listeria spp. in fish and shellfish samples

In fish 38% (n=15) of the total examined samples (n=40) were found to be contaminated by Listeria spp. while 17·0% (n=7) were contaminated with L. monocytogenes. As observed in the coastal water samples, L. innocua was the most prevalent species since it was isolated from 30% (n=12) of the total samples examined (Table 1). These results are in accordance with reports by other authors [6] where the incidence of such a pathogen in fresh fish varied from very low to up to 50%, while a percentage ranging from 14·8 to 72·4% for the presence of Listeria spp. was also reported.

The highest frequency of Listeria spp. was recovered from shellfish where 53% (n=8) of the total examined samples (n=15) were contaminated with Listeria spp. and 33% (n=5) harboured L. monocytogenes. As was found in fish, L. innocua was the most prevalent since it was isolated from 47% (n=7) of the total samples examined (Table 1). These results are a little higher than those reported by Colburn et al. [6] (they found a range from 12 to 44·4% for the presence of Listeria spp. and from 4·0 to 12·1% for L. monocytogenes). In general, the numbers of the samples examined, the pumping rate by shellfish which provokes the accumulation of microorganisms, the ability of Listeria spp. to survive in marine waters and the degree to which Listeria spp. are diluted are all different factors that may affect the uptake and retention of Listeria spp. by the shellfish; and consequently, the numbers of positive samples that might be affected. Moreover, the percentages of the pathogen in fish/shellfish could not be linked to the coastal environment only, this may also be linked to the market environment, although most fish markets in these areas are very close to the seashore.

In conclusion, faecal pollution bacteria as well as Listeria spp. were detected in some sites along the investigated areas. The polluted sites were located either in front of populated cities such as the Suez Gulf area or in front of the industrial/tourism activities in the other investigated areas. Consequently, the discharge of domestic raw/partially treated sewage onto the polluted sites should be taken into consideration. Our results may draw attention to the need to implement better hygiene and epidemiological practices in these areas. In order to avoid listerosis infection, fish and shellfish must be well-cooked before consumption.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gray ML, Killinger AH. Listeria monocytogenes and listeric infection. Bacteriol Rev. 1966;30:309–382. doi: 10.1128/br.30.2.309-382.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McLauchlin J. Listeria monocytogenes, recent advances in the taxonomy and epidemiology of listeriosis in humans. J Appl Bacteriol. 1987;63:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1987.tb02411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Shenawy MA, Marth EH. Listeria monocytogenes and foods: history, characteristics, implication, isolation methods and control: a review. Egypt J Dairy Sci. 1989;17:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prentice GA. Living with Listeria. J Soc Dairy Technol. 1989;42:55–58. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gitler M, Collins CH, Grange JM. Isolation and identification of micro-organisms of medical and veterinary importance. London: Academic Press; 1985. Listeriosis in farm animals in Great Britain; pp. 191–200. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colburn KG, Kaysner CA, Abeyta C, Wekell C, Wekell MM. Listeria monocytogenes in California coast estuarine environment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:2007–2011. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.7.2007-2011.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Shenawy MA, El-Shenawy MA. Listeria species in some aquatic environments in Alexandria, Egypt. Int J Environ Health Res. 1996;6:131–140. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conner DE, Brackett RE, Bauchat LR. Effect of temperature, sodium chloride, and pH on growth of Listeria monocytogenes in cabbage juice. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986;52:59–63. doi: 10.1128/aem.52.1.59-63.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shahamat M, Seamon A, Woodbine M. Survival of Listeria monocytogenes in high salt concentrations. Zentralbl Bakteriol Parasitenkd Infektionskr Hyg Abt 1 Orig Reihe A. 1980;46:506–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elmanseer N, Bakhrouf A. Survival study of Listeria monocytogenes in seawater. Rapp Comm Int Mer Médit. 2004;37:273. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weagent SD, Sado PN, Colburn KG et al. The incidence of Listeria species in frozen seafood products. J Food Prot. 1988;51:655–657. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-51.8.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laciar AL, de Centorbi ONP. Listeria species in seafood in San Luis; Argentina. Food Microbiol. 2002;19:645–651. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karunasager I, Karunasager I. Listeria in tropical fish and fishery products. Int J Food Microbiol. 2002;62:177–181. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(00)00333-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Shenawy MA, El-Shenawy MA. Incidence of Listeria monocytogenes in seafood enhanced by prolonged enrichment. J Med Inst, Alex Univ ARE. 1995;16:32–40. [Google Scholar]

- 15.ISO (International Organization for Standardization). Geneva, Switzerland: No. 9308/1, 1990. Water quality detection and enumeration of coliform organisms, thermotolerant coliform organisms and presumptive Escherichia coli – Part 1: Membrane filtration method. [Google Scholar]

- 16.ISO (International Organization for Standardization). Geneva, Switzerland: No. 7899/2, 1984. Water quality detection and enumeration of streptococci – Part 2: Methods by membrane filtration. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lovett J, Francis DW, Hunt JM. Listeria monocytogenes in raw milk: detection, incidence and pathogenicity. J Food Prot. 1987;50:188–192. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-50.3.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Curtis GDW, Mitchell RG, King AF, Emma J. A selective differential medium for the isolation of Listeria monocytogenes. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1989;8:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 19.IDF (International Dairy Federation). Detection of Listeria monocytogenes. IDF standard. 1990;143:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seeliger HP. Listeriosis – history and actual developments. Infection. 1988;16:580–584. doi: 10.1007/BF01639726. (Suppl 2): [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Ghazali WR, Al-Azawi SK. Detection and enumeration of Listeria monocytogenes in sewage treatment plant in Iraq. J Appl Bacteriol. 1986;60:251–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1986.tb01080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watkins J, Sleath KP. Isolation and enumeration of Listeria monocytogenes from sewage, sludge and river. J Appl Bacteriol. 1981;50:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1981.tb00865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]