SUMMARY

Recently the prevalence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) genotypes and the association between these genotypes and the clinical status of HBV-infected patients were recently investigated in the Lebanese population. The aim of the additional study reported here was to determine the current prevalence of hepatitis delta virus (HDV) infection and the range of HDV genotypes in this Lebanese population. Two hundred and fifty-eight HBsAg-positive patients (107 asymptomatic blood donors, 92 with chronic hepatitis, 24 with cirrhosis, 15 with hepatocellular carcinoma, 20 patients on haemodialysis) from ten medical centers in Lebanon were tested for antibody to hepatitis D virus (anti-HDV). Those testing positive were analysed further for HDV-RNA and for genotyping by reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP). Three samples (1·2%) were anti-HDV positive and out of these, only one was HDV-RNA positive (0·6%) and was analysed as HDV genotype I. Our results point to a low endemicity of HDV in the Lebanese population which is in sharp contrast to data reported from Lebanon 20 years ago and to the situation in neighbouring Arab and non-Arab countries in the Mediterranean region. HDV genotype I seems to be the predominant genotype in Lebanon and the Middle East.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis delta virus (HDV), first discovered by Rizzetto et al. [1] in a patient with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, is a unique single-stranded RNA virus that requires the helper function of HBV for infection [2]. It is established now that co-infection or superinfection of HBV and HDV may cause severe liver disease [3, 4] and HDV may increase hepatocellular carcinoma development three-fold compared to HBV infection without delta virus [5]. The severity of liver disease, however, varies by area and among clinical groups [6], and may be related to the differences in the frequencies of HDV viraemia among anti-HDV-positive cases or to the different genotypes of HDV [7]. Three genotypes of HDV (I–III) have been identified with different geographic distributions: Genotype I is found worldwide with predominance in North America, Europe, Africa, the Middle East and East Asia [8]; genotype II has been isolated only in East Asia (Taiwan and Japan) [9] while genotype III has been restricted to Northern South America (Peru and Colombia) [10].

Lebanon is considered moderately endemic for hepatitis B with an overall carrier rate of 2·2% [11]. However, there are no data on the significance of HDV infection in the Lebanese population except for one hospital-based study published two decades ago on the prevalence of HDV [12]. In this study, HDV infection and HDV genotypes were investigated by testing HBsAg-positive sera from Lebanese patients and blood donors collected from various parts of the country using reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP).

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

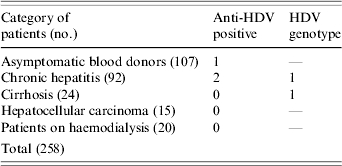

Recently 167 Lebanese individuals (103 males, 64 female) with HBV infection seen at nine medical centres representing the whole country between June 2002 and August 2004 were investigated for the prevalence of HBV genotypes in Lebanon [13]; The mean age of the patients was 42±12 years. A questionnaire designed to gather demographic, clinical and laboratory data was completed for each individual. The demographic data included sex, age, place of birth and travel history. The clinical information included mode of presentation (asymptomatic, symptoms of chronic liver disease), presumed source of infection (sexual, parenteral, other), liver histology and treatment. The manifestations of HBV infection in the 167 individuals were as follows: 46 were asymptomatic blood donors, 82 had symptomatic chronic hepatitis, 24 had cirrhosis and 15 had hepatocellular carcinoma (Table). In addition to the 167 patients mentioned, samples from 91 HBsAg-positive patients collected from one medical centre were also included in the study (61 blood donors, 10 with chronic hepatitis and 20 on haemodialysis; 64 males, 27 females, mean age 36±10 years) (Table). All 258 samples were tested for anti-HDV and for HDV-RNA. Genotyping was determined by RFLP and confirmed by direct sequencing.

Table.

Categories of HBsAg-positive patients tested for antibody to HDV (anti-HDV) and HDV genotypes

Serological assay of HBV and HDV

All samples were confirmed HBsAg in their respective centres and were tested for HBeAg and antibody to HBeAg at the Molecular Virology Laboratory, Faculty of Health Sciences, American University of Beirut using a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (VIDAS HBe/Anti-HBe; bioMérieux, Boxtel, The Netherlands). Testing for anti-HDV was performed by Abbott ELISA kits (Abbott Diagnostic Division, Wiesbaden, Germany).

Determination of Genotypes of HDV

HDV-RNA detection and genotyping

RNA was extracted by the High Pure Viral RNA kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) according to manufacturer's instructions. HDV RNA detection was done using the Ready-To-Go RT–PCR kit (Amersham, Pharmacia Biotech Inc., Uppsala, Sweden) following the manufacturer's specifications with primers 120 (homologous to the sequence of nucleotides 889–912) and 214 (complementary to the sequence of nucleotides 1334–1313) according to the corresponding delta-antigen-coding region [14]. HDV genotyping was investigated using RFLP analysis of the amplified region of nucleotides 911–1260, which is generally accepted to be ideal for the genotyping [10]. In brief, 10 μl from the extracted RNA was used for RT–PCR. The reaction mixture was subjected to 40 cycles of amplification; each cycle consisted of 95°C, 1 min; 42°C, 1 min; 72°C, 1·5 min [14]. The amplified DNA was digested by XhoI (Roche Diagnostics) and SacII (Roche Diagnostics) at 37°C for 3 h. The digested fragments were separated by electrophoresis in 3% agarose gel and stained by ethidium bromide. The restriction pattern was read according to the description of Wu et al. [15]. Genotypes I and II were included in all runs as a control.

Sequencing

Nucleotide sequencing was performed on the only positive sample we had; the result was comparable with the published sequence of HDV genotype I [15].

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first national study on the frequency of HDV infection and on distribution of HDV genotypes in Lebanon. The results of our study show that the prevalence of delta antibody among HBsAg-positive Lebanese patients and blood donors is ∼1% (three patients: one blood donor and two with chronic hepatitis) and contrasts sharply with the earlier report from Lebanon where HDV infection was studied [12]. In that older study, testing for HDV was done on 43 hospitalized patients with acute or chronic active HBV infection revealing absence of HDV infection in patients with acute HBV infection and in 12 asymptomatic HBsAg-positive carriers. Conversely, HDV infection was found in 40% of patients with chronic active hepatitis. The cohort included in this study consisted of hospitalized patients and might, therefore, not represent a true prevalence of HDV infection in Lebanon.

Of interest, our results are in contrast to the situation in neighbouring Arab [16–18] and non-Arab countries in the Mediterranean region [19–21]. For example, anti-HDV positivity was reported in 8·6% and 3·3% of Saudi patients and blood donors respectively [17] compared to 32·7% and 5·2% in Turkish patients and blood donors respectively [20]. HDV infection is common in Asian populations [22] and is also more common in intravenous drug users [21, 23]. None of our patients was an intravenous drug user. The prevalence of HDV has been reported to have decreased significantly over the past decade in various studies [24]. The cause for decreasing HDV infection can be attributed to many factors including anti-HBV vaccination [25], introduction and wide use of disposable needles for blood sampling and other medical purposes in high-risk populations [26], in addition to a natural decline in the HDV endemicity level in some communities [27]. A combination of these factors may have contributed to the decrease in the prevalence of HDV infection in our population.

Although a small number of anti-HDV-positive samples were analysed in this study (three samples), only one was HDV-RNA positive and was characterized as HDV genotype I. This genotype is reported to be the predominant genotype in Egypt [18], Turkey [28], Iran [29] and is perhaps the predominant genotype in the Mediterranean region. Genotype I of HDV has been reported to occur worldwide and to cause chronic hepatitis with a wide spectrum of severity [30]. This is in contrast to HDV genotype II reported in East Asia, Japan and Taiwan which often results in mild chronic hepatitis [31] and to HDV genotype III – confined mainly to North and South America – and which usually results in severe infection [32]. Recently we have shown that genotype D was the only genotype found in Lebanese patients with chronic hepatitis B [13]. Parallel to genotype D of HBV, genotype I of HDV seems to be the unique genotype found in the Lebanese population. No genotypic diversity was found in Lebanese patients with chronic hepatitis B and D. Our study, along with others from neighbouring countries [17, 23–25] point to the predominance of both HBV genotype D and HDV genotype I in countries of the Middle East.

With the introduction of mandatory HBV vaccination to all newborns in Lebanon in 1992–1993 along with other preventive measures, it is anticipated that the decrease in the prevalence of HBV infection may deplete the carrier reservoir of HBV and may lead to complete control and possibly eradication of HDV infection in Lebanon.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported partially by a grant from Schering-Plough and partially by the University Research Board (URB) of the American University of Beirut. The authors thank Drs B. Farhat, M. Bahlawan, U. Farhat, M. Alameddine, E. Nour, R. Sayegh, C. Yaghi, H. Assi, A. Ferzli and R. Shatila. Special thanks go to Mrs Maha Abul Naja for typing the manuscript.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rizzetto M et al. Immunofluorescence detection of a new antigen-antibody system (δ/anti-δ) associated with hepatitis B virus in liver and in serum of HBsAg carriers. Gut. 1997;189:97–1003. doi: 10.1136/gut.18.12.997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smedile A et al. Hepatitis B virus replication modulates pathogenesis of hepatitis D virus in chronic hepatitis D. Hepatology. 1991;13:413–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor JM. Hepatitis delta virus. Intervirology. 1999;42:173–178. doi: 10.1159/000024977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu JC et al. Natural history of hepatitis D viral superinfection: significance of viremia detected by polymerase chain reaction. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:796–802. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90453-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fattovich G et al. Influence of hepatitis delta virus infection on morbidity and mortality in compensated cirrhosis type B. Gut. 2000;46:420–426. doi: 10.1136/gut.46.3.420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hadler SC et al. Epidemiology of hepatitis delta virus infection in less developed countries. Progress in Clinical Biological Research. 1991;364:21–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu JC, Chiang TY, Sheen IJ. Characterization and phylogenetic analysis of a novel hepatitis D virus strain discovered by restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. Journal of General Virology. 1998;79:1105–1113. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-5-1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shakil AO et al. Geographic distribution and genetic variability of hepatitis delta virus genotype I. Virology. 1997;234:160–167. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakugawa H et al. Hepatitis delta virus genotype IIb predominates in an endemic area, Okinawa, Japan. Journal of Medical Virology. 1999;58:366–372. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199908)58:4<366::aid-jmv8>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casey JL et al. A genotype of hepatitis D virus that occurs in northern South America. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1993;19:9016–9020. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.9016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nabulsi MM, ElSaleeby CM, Araj GF The Lebanese hepatitis B collaborative Study Group. The current status of hepatitis B is Lebanon. Lebanese Medical Journal. 2003;51:51–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farci P et al. Delta hepatitis in Lebanon: prevalence studies and a reort on six siblings with chronic delta-positive active hepatitis. Journal of Hepatology. 1987;4:224–228. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(87)80084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharara AI et al. Prevalence of restriction fragment length polymorphism patterns of hepatitis B virus compatible with genotype D in Lebanon. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Disease. 2004;23:861–863. doi: 10.1007/s10096-004-1222-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chao YC et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of an isolate of hepatitis delta virus from Taiwan. Hepatology. 1991;13:345–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu JC et al. Genotyping of hepatitis D virus by restriction-fragment length-polymorphism and its correlation with outcomes of hepatitis D. Lancet. 1995;346:939–941. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91558-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toukan AU. An overview of hepatitis D virus infection in Africa and the Middle East. Progress in Clinical and Biological Research. 1993;382:251–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Traif I et al. Prevalence of hepatitis delta antibody among HbsAg Carriers in Saudi Arabia. Annals of Saudi Medicine. 2004;24:343–344. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2004.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saudy N et al. Genotypes and phylogenetic characterization of hepatitis B and delta viruses in Egypt. Journal of Medical Virology. 2003;70:529–536. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rezvan H et al. A study on delta virus infection and its clinical impact in Iran. Infection. 1990;18:26–28. doi: 10.1007/BF01644177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balik I et al. Epidemiology and clinical outcome of hepatitis D virus infection in Turkey. European Journal of Epidemiology. 1991;7:48–54. doi: 10.1007/BF00221341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dan M et al. Seroepidemiology of hepatitis B and D virus infection among intravenous drug addicts in Israel. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1993;22:140–143. doi: 10.1093/ije/22.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mumtz K et al. Epidemiology and clinical pattern of hepatitis delta virus infection in Pakistan. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2005;20:1503–1507. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kao JH et al. Hepatitis D virus genotypes in intravenous drug users in Taiwan: decreasing prevalence and lack of correlation with hepatitis B virus genotypes. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2002;40:3047–3049. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.8.3047-3049.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huo TI et al. Decreasing hepatitis D virus infection in Taiwan: an analysis of contributory factors. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 1997;12:747–751. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1997.tb00364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mast EE et al. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Part 1: immunization of infants, children, and adolescents. MMWR Recommended Reports. 2005;54:1–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huo TI et al. Changing seroepidemiology of hepatitis B, C and D virus infections in high-risk populations. Journal of Medical Virology. 2003;72:41–45. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sagnelli E et al. Decerase in HDV endemicity in Italy. Journal of Hepatology. 1997;26:20–24. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(97)80004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rozdayi AM et al. Molecular epidemiology of hepatitis B, C and D viruses in Turkish patients. Archives of Virology. 2004;149:2115–2119. doi: 10.1007/s00705-004-0363-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Behzadian F et al. Molecular phylogenetic analysis of Iranian HDV complete genome. Virus Genes. 2005;30:383–393. doi: 10.1007/s11262-004-6782-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cotrina M et al. Hepatitis delta genotypes in chronic delta infection in the northeast of Spain (Catalonia) Journal of Hepatology. 1998;28:971–977. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(98)80345-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ivaniushina V et al. Hepatitis delta virus genotypes I and II cocirculate in an endemic area of Yakutia, Russia. Journal of General Virology. 2001;82:2709–2718. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-11-2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakano T et al. Characterization of hepatitis D virus genotype III among Yucpa Indians in Venezuela. Journal of General Virology. 2001;82:2183–2189. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-9-2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]