SUMMARY

The purpose of this study was to assess and describe the current spectrum of emerging zoonoses between 2000 and 2006 in European countries. A computerized search of the Medline database from January 1966 to August 2006 for all zoonotic agents in European countries was performed using specific criteria for emergence. Fifteen pathogens were identified as emerging in Europe from 2000 to August 2006: Rickettsiae spp., Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Borrelia burgdorferi, Bartonella spp., Francisella tularensis, Crimean Congo Haemorrhagic Fever Virus, Hantavirus, Toscana virus, Tick-borne encephalitis virus group, West Nile virus, Sindbis virus, Highly Pathogenic Avian influenza, variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, Trichinella spp., and Echinococus multilocularis. Main risk factors included climatic variations, certain human activities as well as movements of animals, people or goods. Multi-disciplinary preventive strategies addressing these pathogens are of public health importance. Uniform harmonized case definitions should be introduced throughout Europe as true prevalence and incidence estimates are otherwise impossible.

INTRODUCTION

The ability of infectious agents to cross the species barrier explains why numerous zoonotic and vector-borne agents affect humans. Of the growing list of human pathogens, 1415 according to one report [1], 61% are zoonotic [1]. Among emerging infectious diseases, 75% are zoonotic, originating principally from wildlife [2]. The latter is a reservoir of microorganisms that, once transferred to humans, may emerge as public health threats [2]. Other factors that might be important in the emergence and spread of zoonotic and vector-borne diseases include the increasing proximity of human and animal populations caused by growth of the human population, their mobility for recreational, cultural and socioeconomic purposes, and the efforts to keep them well nourished [1, 2]. Air transportation and air travel may facilitate the global spread of emerging infectious diseases as occurred with the SARS epidemic [1].

Detecting a rise in incidence of a specific disease remains the cornerstone of containment of an emerging communicable threat. However, as the emergence of an infectious disease appears to be the end result of a multi-factorial complex process, there is difficulty in predicting it, and also in responding quickly. This review attempts to identify zoonoses and vector-borne diseases that had an increasing impact on humans in Europe in the period from 2000 to August 2006. In addition, it discusses the social, ecological, technological and microbial factors that have affected emergence of such infections. Monitoring changes in these factors will be of paramount importance in the strategies against these infections.

METHODS

Search strategy and selection criteria

A computerized search of the Medline database from January 1966 to January 2006 was conducted. Articles reporting original data and original articles on emerging or re-emerging zoonoses in European countries were the sources used for this review. The terms used in the search included ‘emerging zoonoses’, ‘Europe’, ‘European countries’, and all the 46 European countries separately. In addition cross-checking of the results was performed with additional searches using all zoonoses from a formal recent combined WHO/FAO/OIE European Region Report [3]. The specific criteria used for each country were [3, 4]: (a) the detection of a new zoonotic or vector-borne species associated with human disease, (b) an increase in the incidence of a known zoonotic or vector-borne disease in humans, (c) spread of a pathogen to a new vector or animal reservoir and change in transmission dynamics, and (d) novel geographical locations for hosts or vectors of these pathogens. Each individual type of emergence is indicative of a separate dimension of the public health impact of each pathogen.

Exclusion criteria

Emerging zoonoses or vector-borne infections that could be potentially imported into Europe from other continents were excluded from this review.

RESULTS

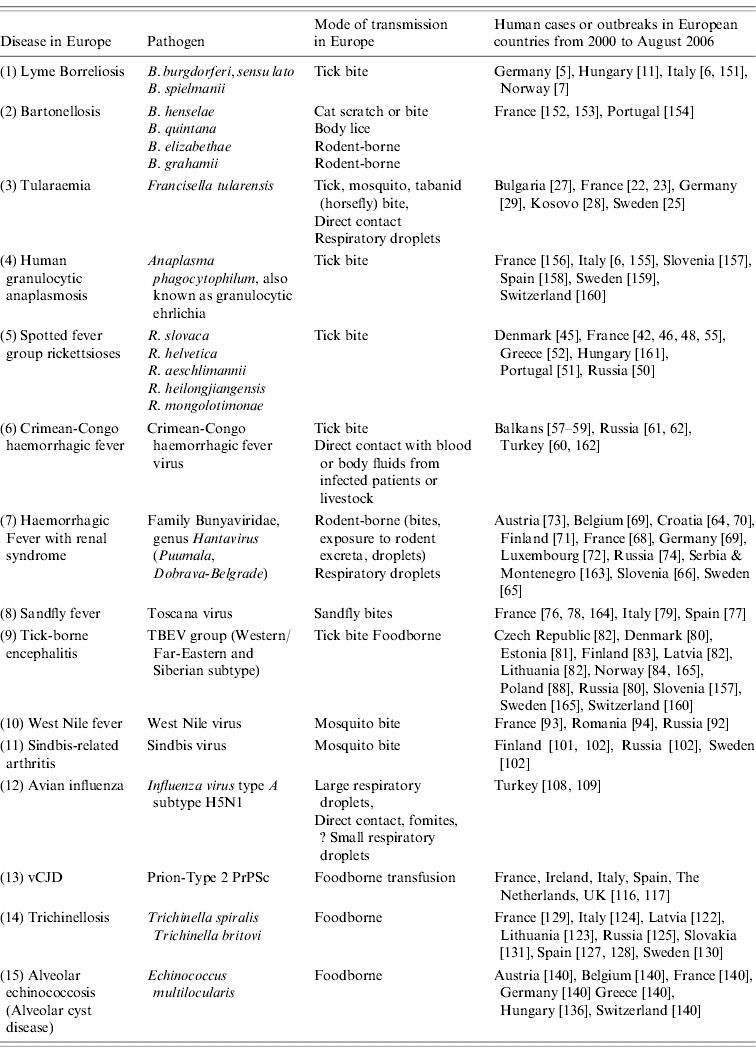

Fifteen emerging zoonotic or vector-borne infections with increasing impact on humans in Europe during the last 7 years were identified (Table 1). Table 2 lists a description of the identified agents together with their factors affecting emergence.

Table 1.

Emerging zoonoses and vector-borne diseases in Europe: pathogens, main modes of transmission, and recent data on human cases or outbreaks in European countries from 2000 to August 2006

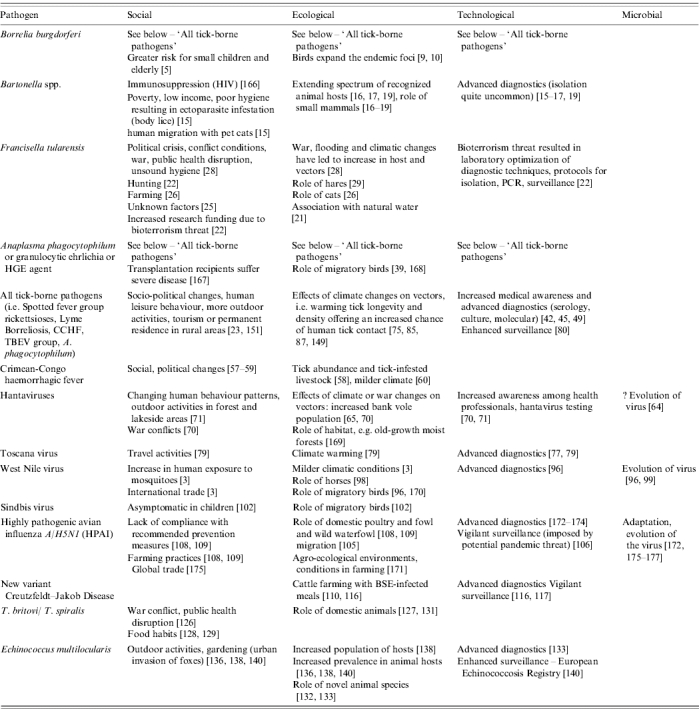

Table 2.

Risk factors for the emergence of zoonoses and vector-borne diseases in Europe from 2000 to August 2006

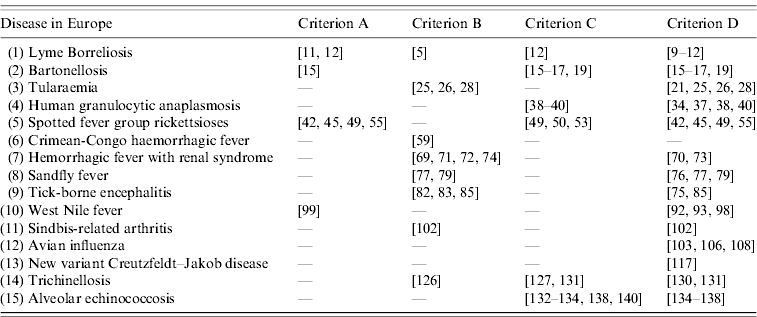

The emergence of several of these infections is related to multiple factors (e.g. movement of animals and climatic changes affecting vectors) and the degree of importance of one over the other is not always easy to determine. Emergence of vector-borne diseases is predominantly affected by climatic variations and changes, and certain human activities and behaviour. On the other hand emergence of Hantaviruses, highly pathogenic avian influenza A/H5N1, trichinellosis, echinococcosis and prion disease is associated predominantly with other factors such as movements of animals, people or goods (Table 3). A detailed description of individual agents is given below.

Table 3.

Criteria for emergence of the identified zoonoses and vector-borne diseases in Europe from 2000 to August 2006

BACTERIAL AND RICKETTSIAL INFECTIONS

Borrelia burgdorferi

Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato is a complex of the following species: B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. afzelii, B. garinii, B. bissettii and B. lusitaniae that have been implicated as a cause of human Lyme disease mostly in central and Northern European countries [5–7] including Scandinavia, Austria, Germany, and Switzerland (Table 1). Iceland is reportedly free of the disease, and Ireland has a very low incidence. An increase in incidence of 33%, from 17·8 cases/100 000 population in 2002 to 23·3 cases/100 000 in 2003 has been noted in eastern German states recently [5]. In Norway the highest number of Lyme cases, 253 in total, was noted as recently as 2004 [7].

The factors behind the increase in incidence are not clear (Table 2). Rodents serve as important hosts in the enzootic cycle of the disease and their population expansion may be a factor. A high proportion of rodents in Central Europe are seropositive for B. burgdorferi [8]. Along with a substantial role in the maintenance of Lyme's disease in enzootic foci, migratory birds transfer infected ticks across national and intercontinental borders establishing new endemic foci of disease. Since ticks may attach to a host for 24–48 h, sufficient time is provided for some birds to travel hundreds or even a few thousand miles along migration routes before ticks complete feeding and drop off [9]. Even transhemispheric transfer by seabirds has been proven [10]. A novel genospecies causing Lyme disease, B. spielmanii, has been recently detected in Hungary, The Netherlands and Czech Republic [11] and in several French and German sites where garden dormice have been identified as a new reservoir host [12] (Table 3).

Along with the emergence of Lyme borreliosis in the temperate northern hemisphere, there is an increased awareness of the potential for emergence of human babesiosis in Europe due to its transmission by the same tick vectors [13].

Bartonella spp

New Bartonella spp., an extended animal host range, and new endemic locations have been recognized since 2000 (Table 1). Advanced molecular diagnostics have greatly enhanced our ability to detect Bartonella spp. infections and have assisted in defining their mammalian reservoirs. Serology is mostly useful for the Cat Scratch Disease (CSD) agent Bartonella henselae.

Novel species have been recognized and may pose a threat to humans, e.g. the rodent-borne B. elizabethae, B. grahamii, and the feline B. koehlerae [14, 15].

Novel vectors and an extended range of mammal reservoirs have been identified including rodent and cat fleas for the rodent-borne and feline-borne Bartonella spp. respectively [15, 16].

Expansion of the range of vectors and mammal reservoirs has been noted for B. henselae and other Bartonella spp. in recent years [16]; B. henselae, the CSD agent has been identified in the tick Ixodes ricinus, in long-tailed field mice and in domestic cats in novel geographical areas in Europe [17, 18]. B. quintana which causes the body-lice-mediated trench fever in humans and had no known animal reservoir, was shown to infect a domestic cat. This could explain B. quintana infections identified in humans who maintain high hygiene standards, are not infested with body lice, but have close contact with cats (Tables 2 and 3) [19].

Francisella tularensis

Tularemia caused by Francisella tularensis, a Gram-negative coccobacillus, is a widely dispersed disease throughout the Northern Hemisphere including Europe where only F. tularensis subsp. holarctica, also known as type B is endemic [20–24]. The terrestrial and aquatic cycles of the infection include a wide variety of rodent reservoirs, e.g. hares, squirrels, bank voles, beavers, muskrats, as well as a spectrum of diverse arthropod vectors such as ticks, midges and mosquitoes. In each geographical location diverse numbers of vectors and vertebrate hosts may be involved, e.g. tabanids, voles, hamsters, mice, and hares in Russia, mosquitoes in Sweden, Finland, Russia, and ticks in Central Europe [20–24] (Table 1).

In Finland and Sweden outbreaks were recorded at least once every decade [25, 26], but as a human disease it has re-emerged causing increasing numbers of cases in Bulgaria in the last decade [27], Sweden in 2000 and 2003 [25, 26] and more recently in France [23].

In other areas outbreaks occur only occasionally except in times of socio-ecological change and disruption of the public health system such as has occurred recently from armed conflict in Kosovo (Table 2) [28]. Contact with animal products through wounds and abrasions, consumption of contaminated food or water [28], and inhalation [23] are the main modes of transmission in endemic areas [21]. The most recent outbreak was reported from Germany among hare hunters in January 2006 [29] (Table 3).

Anaplasma phagocytophilum

Human granulocytic anaplasmosis (also known as human granulocytic ehrlichiosis), is a tick-borne zoonosis caused by the pathogen Anaplasma phagocytophilum (formerly named Ehrlichia phagocytophila and Ehrlichia equi). It was associated with tick-borne fever in cattle, sheep, and goats in Europe for several decades.

Human cases emerged in Europe in 1996 [30] and have been reported in several European countries since then (Table 1) [31]. Co-infection with Borrelia burgdorferi is attributed to their common vectors [13, 32, 33], I. ricinus ticks (throughout Europe), and I. persulcatus ticks (Eastern parts of Europe) [34, 35].

Transmission and propagation of A. phagocytophilum occurs in large mammals such as horses, cattle, sheep, goats, dogs, cats in Europe. Small mammals and not ticks are the reservoirs of anaplasmoses. Several rodent and other animal species contribute in various European countries [36–40], e.g. roe deer have a principal role in the life-cycle of I. ricinus in Spain [40].

Roe deer are the main reservoir for A. phagocytophilum in Central Europe and Scandinavia with a high seroprevalence of about 95% and a variable rate of PCR-proven infection ranging from 12·5% in the Czech Republic to 85·6% in Slovenia [41].

Expansion of vectors and reservoirs into novel geographical locations has been noted in several countries, e.g. Spain [40], Austria [36], Czech Republic [36] and Denmark [41]. The role of migrating birds in long-range tick transfer may be important since the same A. phagocytophilum gene sequences were detected in infected ticks on migrating birds and in humans and domestic animals in Sweden [39] (Tables 2 and 3).

Rickettsiae spp

Spotted fever group (SFG) rickettsioses caused by novel species such as R. slovaca [42–44], R. helvetica [45–47], R. aeschlimannii [44, 48, 49] and others such as R. sibirica sensu stricto [50, 51], R. heilongjiangensis [50], and R. mongolotimonae [51, 52] are emerging (Table 1). This emergence may only be an artefact reflecting the wide application of molecular diagnostic techniques which have facilitated identification and characterization. There is evidence that SFG rickettsioses were initially misidentified by serology as R. conorii, the common pathogen of Mediterranean spotted fever [49, 53]. Ticks may serve as vectors, reservoirs and/or amplifiers for most of these new species. Vertebrates are bacteraemic for short periods and whether they can serve as reservoirs is still under discussion [49, 54].

Novel geographical locations have been noted for vectors and hosts of rickettsial species. R. slovaca, originally isolated from ticks in Slovakia, is now recognized as a human pathogen in France [47, 55]. More recently R. slovaca and R. helvetica were the first recognized rickettsioses in Scandinavia [45]. Although the reasons for this geographical expansion are unclear, the role of both migrating birds and tick-infested dogs imported into Northern European areas cannot be underestimated [56]. Recently rare rickettsial species such as R. mongolotimonae have been associated with human disease in the Mediterranean area [51, 52]. The burden of tick infestation with SFG rickettsiae is rising and this, together with the currently observed expansion of the tick vectors' range and geographical distribution in Europe [44–46 44–46, 49, 50, 53] suggests an increased risk for human infection (Tables 2 and 3).

VIRAL INFECTIONS

Crimean-Congo Haemorrhagic Fever (CCHF) virus

CCHF infection, genus Nairovirus, family Bunyaviridae, is widespread in Africa, Asia, Middle East and East Europe. CCHF has a fatality rate up to 17%, which can be even greater in nosocomial outbreaks. The infection is transmitted by ixodid ticks, e.g. Hyalomma marginatum, Rhipicephalus rossicus, Dermacentor marginatus or by body fluids from viraemic hosts, e.g. humans or livestock [57–62] (Table 1).

Outbreaks of CCHF have been reported between 2000 and 2006 from South-Eastern Europe – in Bulgaria in 2002 and 2003 [57], in Albania and in Kosovo in 2001 [58, 59] with still undefined reservoirs. Social disruption, conflict, or war were major factors [57–59].

An outbreak in Turkey began as increased activity of the infection in 2002. Up to until 2005 about 500 cases were reported to the Turkish Ministry of Health. Twenty-six of these cases died. The virus was transmitted via tick bite or contact with blood or other infected tissues from viraemic livestock [60]. This CCHF outbreak in Turkey may be attributed to the milder climate reported during April in the year preceding the outbreak [60] (Tables 2 and 3).

In genetic analyses, strains from Bulgaria were similar to others from Albania, Kosovo, European (South West) Russia and Turkey. However, a great divergence was seen between these virus strains and the non-pathogenic AP 92 strain from Greece, and strains from Asia and Africa [57, 60–62].

Hantavirus

The main Hantaviruses, genus Hantavirus, family Bunyaviridae, seen in Europe, are Dobrava-Belgrade and Puumala. They are associated with haemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) whereas Seoul virus causes a mild HFRS, with worldwide distribution, but without reported clinical disease in Europe thus far. The main mode of transmission is via inhalation of aerosols from excreta of persistently infected rodents. High-risk groups include farmers, forestry workers, and individuals in close contact with wildlife [63–65] (Table 1).

Dobrava-Belgrade virus has been reported as a cause of severe HFRS in the Balkans [64, 66] and Russia [63]. Puumala virus on the other hand causes a milder disease, called nephropathia epidemica, and has been described in Western Russia [67], Scandinavia [65], Western Europe, including France [68] Germany [69], and the Balkans (excluding the Mediterranean region) [70]. The coexistence of the two viruses in the Balkans [64, 70] might lead to exchange of genetic material and emergence of new viral subtypes.

An increased incidence has been recently seen in Central and Northern European countries, including Belgium, France, Germany [69], Finland [71], and Luxembourg [72]. During the first quarter of 2005 the incidence in parts of Belgium and France rose to 5·5 and 13·8/100 000 population respectively [69]. The first human case in Austria was reported in February 2006 [73]. A large outbreak of more than 10 000 cases of Puumala virus-induced HFRS was identified in 2004 in the European region of Russia with an annual incidence of 124/100 000 in the Udmutria Republic and a case-fatality rate of about 1% [74].

Novel endemic areas were recognized in Croatia during the 2002 Puumala virus outbreak that followed war conflicts, abandonment of human settlements and uncontrolled rodent population expansion (Table 3) [70].

The emergence of these viruses has been attributed to ecological changes of the rodent reservoir habitats, the milder climate in Northern Hemisphere and altered human behaviour patterns (Table 1) [65, 70, 71, 75]. However, increased awareness among physicians and better access to Hantavirus testing may account for the increase in registered Hantavirus infections in Europe [69].

Sandfly fever viruses (Toscana, Naples, Sicilian)

Sandfly fever viruses belong to genus Phlebovirus, family Bunyaviridae. They are transmitted in the Mediterranean area by the sandflies Phlebotomus perniciosus and P. perfiliewi. Naples and Sicilian sandfly fever viruses cause mild self-limiting disease of unknown epidemiology. Toscana virus is the third most frequent cause of aseptic meningitis between May and October in Central Italy, where it was originally isolated from sandflies in 1971 (Table 1). Toscana virus has since been detected in France [76], Spain [77], Slovenia, Greece, Cyprus, Turkey and other European countries [78, 79] (Table 3). In all Northern Mediterranean countries Toscana virus should be included in the differential diagnosis of viral meningitis during the warm season. Entomological studies may provide a better estimation of the variety of vectors, their geographic distribution, and the disease potential for further spread (Table 2) [77, 79].

Tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) group

The TBEV group, genus Flavivirus, family Flaviviridae, is a complex of closely related viruses affecting the central nervous system (Table 1). Importantly, several other viral species including those belonging to the genus Bunyaviridae and Togaviridae can be involved in the syndrome of tick-borne encephalitis (TBE). The TBEV group includes the European subtype, widely distributed in Europe and transmitted by I. ricinus ticks, and the Far-Eastern and Siberian subtypes, present from the Far East to Baltic countries and transmitted by I. persulcatus ticks [80]. Recently, foodborne outbreaks of TBE linked to consumption of unpasteurized goats' and cows' milk have been reported in Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia [80, 81].

Cases of TBE have been recorded focally throughout Central and Eastern Europe and Scandinavia [80, 82]. During the last 5 years an increasing incidence has not only been noted in most Central European countries [82, 83] but has also spread to European areas previously considered free of disease, e.g. Norway [84]. Latvia and neighbouring Finland (especially the Aland island area where annual incidence was 100/100 000 population in 2001) [83], areas in Russia and the Czech Republic [80] show very high incidences whereas in Austria a significant decrease occurred after a specific immunization programme [80].

It could be speculated that recent climatic changes and global warming may change the transmission dynamics of the TBE viruses [84] and the TBE risk area may enlarge even more in landscape types suitable for leisure and recreational activities [85]. The TBE viruses are maintained in nature in a cycle involving permanently infected ticks and wild vertebrate hosts. The viruses are transmitted horizontally between vectors and vertebrates especially from spring to autumn with small mammals serving as reservoirs of the virus [86]. I. ricinus, the principal tick vector involved in the transmission of the European subtype in Central Europe is found in microhabitats with high humidity and moderate temperatures. Temperature patterns during the year determine the altitude above sea level (a.s.l.) where there is high risk for a tick bite. A study of the popular resort area, Sumava Mountains in the Czech Republic (a region that borders the Czech Republic, Germany and Austria), revealed that I. ricinus habitats have reached 1000–1100 m a.s.l. compared to 700 m a.s.l. during the previous decade (Table 3). Human cases have already been reported from the Sumava Mountains area at altitudes as high as 900 m a.s.l. [85, 87] (Table 3). TBE is a growing concern in Europe but case definition and notification schemes are not yet uniform and may affect the estimated prevalence of the disease focally (Table 2) [88, 89].

West Nile virus (WNV)

WNV is a member of the genus Flavivirus, family Flaviviridae (Table 1). The virus is transmitted mainly by mosquito bites [90]. Before 2000, it was enzootic in Africa, Europe, and Asia where it was maintained in natural cycles between birds and mosquitoes [90]. Large outbreaks occurred in the European countries of Romania in 1996 [91] and Russia in 1999 [92]. Human and equine WNV infections have recently been described in France [93, 94] and Portugal [95].

Phylogenetic analyses have shown that WNV strains from France 2000 (horse), Tunisia 1997 (human) and Kenya 1998 (mosquito) belong to same genetic lineage possibly indicating the circulation of the virus along migratory bird routes in Europe [9, 96]. Similarly, it is thought that a strain closely related to the Israel strain first identified in 1951 [90] was transferred by migratory birds to New York, where it triggered a human outbreak of WNV encephalitis in late 1999. This was the first documented occurrence of this virus in the Western Hemisphere [97].

New European areas are affected by expanding vector and vertebrate hosts [96–98]. Moreover, novel viral strains closely related to WNV (initially identified as WNV), and characterized with molecular techniques [99], are now present in Central Europe and southern Russia [99]. As the genetic evolution of WNV continues to be observed this virus remains an important public health threat (2 and 3) [100].

Sindbis virus

Sindbis virus, genus Alphavirus, family Togaviridae, was first isolated in 1952 [101] causing a rash and fever-related arthritis called Pogosta disease in Finland, Ockelbo disease in Sweden and Karelian fever in European Russia (Table 1). A higher than expected seroprevalence (including children) has been recently shown in Finland [102] (Table 3). The disease is mild or asymptomatic in children causing underestimation of the problem. Northern European strains are genetically similar to each other [101] and to African strains [102], indicating transfer by migratory birds (Table 2) [102].

Highly pathogenic avian influenza A/H5N1 (HPAI)

The recent wide geographical spread of the virus [103] is attributed to its apparent carriage by migratory birds [9, 104] from Asia to Europe and now to Africa [105], the expansion of host range in other mammals as well as the increased risk for human infection especially for persons involved in commercial poultry farming [106]. Suspected human cases were identified in Europe based on epidemiological criteria [107] and confirmatory testing was positive in Turkey without evidence of human-to-human transmission (Table 1) [108]. In Turkey severe weather conditions forced people into closer contact with their domestic birds with subsequent increased human exposure to the virus [109].

The conditions for zoonotic transmission of avian influenza will probably not be found in most other parts of Europe (excluding the influenza pandemic). HPAI is a global threat and its presence has increased awareness about a potential influenza pandemic [106] (Table 3). Pre-pandemic planning and response activities are necessary for all countries around the world especially those with poor resources (Table 2).

New variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (vCJD)

vCJD was initially recognized in 1995–1996 in several patients from the United Kingdom and one from France [110–112] (Table 1). There are questions regarding its pathogenesis [113]. It is primarily considered as foodborne and is associated with the zoonotic epidemic of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE). Any patient that has had a cumulative residence of 6 months or more in the United Kingdom during the period from 1980 to 1996 is considered at risk [114, 115]. Several controversial issues regarding vCJD exist, e.g. the percentage of the population exposed to BSE-contaminated beef during that period and the contribution of the still unknown co-factors in the pathogenesis of the disease [115].

An international network reports surveillance data for vCJD cases (Table 2). Current data (up to 17 November 2006) of patients with vCJD that have died include 156 cases in Britain, 19 in France, three in Ireland, two in The Netherlands, and one each in Italy and Spain; extending the list of affected countries [116] (Table 3).

Future predictions about at-risk populations are difficult to make. In the United Kingdom where the vCJD epidemic was first recognized, annual incidence is not increasing and it is thought that only a few cases will occur during the next years [116, 117]. However, it cannot be excluded that the limited outbreak experienced from 1996 to today may be followed by another. The emergence of transfusion-associated vCJD, i.e. two cases from the United Kingdom, caused the initiation of stricter measures for the reduction of risk associated with blood transfusions [118–121].

PARASITIC INFECTIONS

Trichinellosis

Most trichinella infections worldwide are attributed to Trichinella spiralis which parasitizes domestic animals. Rarely can they be associated with other parasite species such as T. britovi and T. nativa that mainly infest wildlife (Table 1).

Trichinella spp. are transmitted directly by ingestion of infective larvae through consumption of undercooked meat. Only thoroughly cooked meat is safe for consumption, whereas smoking, salting and drying are unreliable as meat processing techniques. Industrialized pig farming and meat inspection have prevented endemic trichinellosis caused by T. spiralis in Western Europe. However inadequate inspection is implicated in outbreaks after 2000 in Lithuania and Latvia where the annual incidence is 0·6 and 0·7–1/100 000 population respectively (Table 2) [122, 123].

Horse meat consumption was implicated in T. spiralis outbreaks in France and Italy [124]. Socioeconomic changes are well known to be associated with peaks in the incidence of the disease [125] – as recently in Serbia [126]. T. britovi is an emerging pathogen in free-range domestic pigs which may feed on rodents infected with the parasite. The parasite's presence is maintained in sylvatic cycles involving wild pigs, foxes and rodents of the same habitat as is the case in Spain [127] and France [128]. Infection originating from wildlife is emerging, as hunting and consumption of raw meat are becoming more popular, e.g. in France (Table 2) [129].

Recently another species, Trichinella pseudospiralis, a cosmopolitan non-encapsulated species has been detected in Sweden [130] and in pigs, rats and a cat in a farm in Slovakia [131] (Table 3). Raptorial migrating birds that are well-known hosts of T. pseudospiralis introduced the parasite into this area which serves as a crossing of Pan-European bird migration routes from Europe and northern Asia in autumn and spring (Table 2) [131].

Alveolar echinococcosis

Alveolar echinococcosis (alveolar cyst disease), endemic in Northern Central Europe and the Arctic region, is caused by the small tapeworm Echinococcus multilocularis carried by its terminal hosts, e.g. foxes, dogs, wolves, that shed the parasite's eggs in their faeces (Table 1). It is transmitted through consumption of infected raw or undercooked food containing eggs of the parasite. Humans serve as inadvertent intermediate hosts. The water vole is the principal intermediate host in Central Europe along with more than 40 species of rodents. The prevalence of the parasite is increasing in rodents that spillover the organism to other animal species, e.g. beavers [132], wild boars [133] or wolves [134]. Parasite eggs have been detected in 47·3% of excreta from red foxes in the city and 66·7% from red foxes in the adjacent recreational areas, which also migrate eastwards as a result of their population expansion [135–138]. Interestingly the population of both water voles and red foxes is increasing as a result of ecological changes (voles) and institution of animal anti-rabies vaccination programmes (foxes) [136–138]. Furthermore, the infection has been now transmitted to domestic dogs and cats that comprise a permanent source of human infection near dwellings [138, 139] (Table 3).

In Europe up to 2000, 559 human cases were verified (Table 1) [140]. As the incubation time is thought to be anywhere from 5 to 15 years the limited number of sporadic human cases after 2000 is not a reassuring finding. The high annual incidence in particular regions [140], the spread of the parasite sylvatic cycle in other meadow ecosystems and the expansion to other animal hosts indicate a possible spread of the infection and underestimation of the problem (Table 2). Currently a surveillance scheme has been established with participation from 12 European countries, the European Echinococcosis Registry [140].

Other

Although not among the emerging zoonoses, brucellosis and visceral leishmaniasis had a significant impact on the endemic European countries.

Brucellosis is endemic in most Southern European countries, with sporadic outbreaks, but the impact on humans has not increased since 2000. The epidemiological trends vary slightly according to the strictness of the preventive measures especially the ones concerning dairy products [141] and imported cases from endemic to non-endemic European countries offer a diagnostic challenge [142].

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) due to Leishmania infantum is a zoonotic disease, endemic in Southwest Europe where the predominant vector is the sandfly Phlebotomus perniciosus and the main reservoir of infection is dogs. HIV patients are more susceptible to the infection, but there was a fall in the proportion of cases of HIV/VL co-infection after 1996 following the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy [143, 144]. Eighty-five percent of these co-infections originate from Southwest Europe, 71% of them affecting intravenous drug users [143–145]. In the last decade, the disease has been stable in Europe except for an increasing shift from rural areas to suburbs where dogs are present and small gardens offer refuge to the vector [146]. New zoonotic foci of canine leishmaniasis have been detected in the northwest of Italy, without an increase in the incidence of the human disease [147, 148]. Climatic changes in the future could modify the geographical distribution, rendering surveillance for vector spread necessary even in the absence of established increasing impact for humans in Europe from 2000 to the present.

DISCUSSION

Several bacterial, viral and parasitic zoonoses affecting humans have emerged in the last 6 years in Europe by strictly defined criteria. The phenomenon may be associated with social, ecological, technological and microbial risk factors which act synergistically to facilitate emergence of such pathogens in Europe.

Social factors include human mobility especially with air travel, tourism and outdoor activities, permanent residence in rural areas, food habits, international commerce, war and political conflicts.

Concerning ecological factors it is probable that milder climate (global climatic change) may be followed by a northern shift in the distribution of major disease vectors, i.e. ticks and mosquitoes [75, 149]. A milder winter, earlier arrival of spring and/or late arrival of the following winter permit prolonged seasonal tick activity and hence pathogen transmission, a general increase in vector and mammal populations and changes in the migration patterns of animals and birds. However, more research is necessary to investigate and identify the effect of climate changes on emerging infectious diseases [150]. The ecological changes may act in combination with social factors to increase the chance that a communicable disease emerges, e.g. recent emergence of arthropod-borne infections like TBEV group encephalitis, Lyme borreliosis and anaplasmoses [75, 149].

Microbiological factors contribute to disease spread and emergence into new territories, e.g. the evolution noted in WNV and Avian influenza A(H5N1).

Technological factors may contribute to the false sense of ‘emergence’ of such diseases. These include the enhanced diagnostic techniques including newer molecular methods that facilitate the isolation and characterization of emerging pathogens as well as the increased awareness of physicians with careful case-history recording and laboratory investigation leading to subsequent correct diagnosis and reporting. Tularemia historically could have remained unrecognized as it affected a limited number of humans. As a potential bioterrorist weapon it received increased awareness among physicians followed by increased research funding, enhanced diagnostics and vigilant surveillance systems. Furthermore, the surveillance of emerging zoonotic diseases in the European countries is not uniform. Uniform harmonized case definitions and laboratory assays should be introduced in all European countries; as an example the true prevalence estimates for TBE might be affected by case definition restrictions [88]. Notification for the majority of these diseases is not mandatory, it is based on voluntary laboratory reporting schemes leading to underreporting. Consequently, it is possible that enhanced monitoring and optimized diagnostics may account for the observed emergence in certain geographic locations.

A potentially valuable tool in the accurate estimation of the prevalence and incidence of these pathogens might be the performance of virological investigation of their vectors and seroepidemiological surveys regarding their human reservoirs and their animal hosts. Animal serological data can be used to identify novel zoonotic foci and assist in predicting human outbreaks. Long-term surveillance of natural foci in endemic regions provides useful information on the activation of zoonoses and may provide a marker for future outbreaks. This permits timely epidemiological prognosis and institution of preventive measures. In that respect it is necessary to highlight the need to train young people in disciplines such as entomology and wildlife biology.

In conclusion, 15 zoonotic and vector-borne agents were identified as emerging threats with a public health impact for humans in Europe for the period from 2000 to August 2006. National and regional public health sectors should give priority to surveillance systems and enhanced diagnostics regarding these emerging pathogens. A broad collaboration among clinicians, public health workers, veterinary medicine and veterinary public health officials is necessary for prompt response strategies ensuring the prevention and management of such infections.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cunningham AA. A walk on the wild side – emerging wildlife diseases. British Medical Journal. 2005;331:1214–1215. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7527.1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blancou J et al. Emerging or re-emerging bacterial zoonoses: factors of emergence, surveillance and control. Veterinary Research. 2005;36:507–522. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2005008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Report of the WHO/FAO/OIE Joint Consultation on Emerging Zoonotic Diseases Geneva, Switzerland: . 3–5 May 2004, ). Accessed 15 August 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hughes JM. Emerging infectious diseases: a CDC perspective. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2001;7:494–496. doi: 10.3201/eid0707.017702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehnert WH, Krause G. Surveillance of Lyme borreliosis in Germany, 2002 and 2003. Eurosurveillance. 2005;10:83–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santino I et al. Multicentric study of seroprevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi and Anaplasma phagocytophila in high-risk groups in regions of central and southern Italy. International Journal of Immunopathology and Pharmacology. 2004;17:219–223. doi: 10.1177/039463200401700214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nygard KK, Brantsaeter AB, Mehl R. Disseminated and chronic Lyme borreliosis in Norway, 1995–2004. Eurosurveillance. 2005;10:235–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stefancikova A et al. Anti-Borrelia antibodies in rodents: important hosts in ecology of Lyme disease. Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine. 2004;11:209–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reed KD et al. Birds, migration and emerging zoonoses: West Nile virus, Lyme disease, Influenza A and Enteropathogens. Clinical Medicine & Research. 2003;1:5–12. doi: 10.3121/cmr.1.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olsen B et al. Transhemispheric exchange of Lyme disease spirochetes by seabirds. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1995;33:3270–3274. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.12.3270-3274.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foldvari G, Farkas R, Lakos A. Borrelia spielmanii erythema migrans, Hungary. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2005;11:1794–1795. doi: 10.3201/eid1111.050542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richter D et al. Relationships of a novel Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia spielmani sp. nov., with its hosts in Central Europe. Applied Environmental Microbiology. 2004;70:6414–6419. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.11.6414-6419.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piccolin G et al. A Study of the presence of B. burgdorferi, Anaplasma (previously ehrlichia) phagocytophilum, Rickettsia, and Babesia in Ixodes ricinus collected within the territory of Belluno, Italy. Vector Borne and Zoonotic Diseases. 2006;6:24–31. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2006.6.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Avidor B et al. Bartonella koehlerae, a new cat-associated agent of culture-negative human endocarditis. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2004;42:3462–3468. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.8.3462-3468.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boulouis HJ et al. Factors associated with the rapid emergence of zoonotic Bartonella infections. Veterinary Research. 2005;36:383–410. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2005009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tea A et al. Bartonella species isolated from rodents, Greece. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2004;10:963–964. doi: 10.3201/eid1005.030430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engbaek K, Lawson PA. Identification of Bartonella species in rodents, shrews and cats in Denmark: detection of two B. henselae variants, one in cats and the other in the long-tailed field mouse. Acta Pathologica, Microbiologica et Immunologica Scandinavica. 2004;112:336–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2004.apm1120603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melter O et al. Detection and characterization of feline Bartonella henselae in the Czech Republic. Veterinary Microbiology. 2003;93:261–273. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(03)00032-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.La VD et al. Bartonella quintana in domestic cat. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2005;11:1287–1289. doi: 10.3201/eid1108.050101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cross TJ, Penn RL, Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 5th edn. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingston; 2000. Francisella tularensis (tularemia) pp. 2393–2402. ; pp. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tarnvik A, Priebe HS, Grunow R. Tularaemia in Europe: an epidemiological overview. Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2004;36:350–355. doi: 10.1080/00365540410020442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vaissaire J et al. Tularemia. The disease and its epidemiology in France [in French] Medecine et Maladies Infectieuses. 2005;35:273–280. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siret V et al. An outbreak of airborne tularaemia in France, August 2004. Eurosurveillance. 2006;11:58–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perez-Castrillon JL et al. Tularemia epidemic in northwestern Spain: clinical description and therapeutic response. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2001;33:573–576. doi: 10.1086/322601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Payne L. Endemic tularemia, Sweden, 2003. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2005;11:1440–1442. doi: 10.3201/eid1109.041189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eliasson H et al. The 2000 tularemia outbreak: a case-control study of risk factors in disease-endemic and emergent areas, Sweden. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2002;8:956–960. doi: 10.3201/eid0809.020051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kantardjiev T et al. Tularemia outbreak, Bulgaria, 1997–2005. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2006;12:678–680. doi: 10.3201/eid1204.050709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reintjes R et al. Tularemia outbreak investigation in Kosovo: case control and environmental studies. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2002;8:69–73. doi: 10.3201/eid0801.010131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hofstetter I et al. Tularaemia outbreak in hare hunters in the Darmstadt-Dieburg district, Germany. http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ew/2006/060119.asp#2. Eurosurveillance. 2006;11 doi: 10.2807/esw.11.03.02878-en. : E060119.3 ( [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petrovec M et al. Human disease in Europe caused by a granulocytic Ehrlichia species. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1997;35:1556–1559. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1556-1559.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blanco JR, Oteo JA. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Europe. Clinical microbiology and infection (the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases) 2002;8:763–772. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2002.00557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parola P, Davoust B, Raoult D. Tick- and flea-borne rickettsial emerging zoonoses. Veterinary Research. 2005;36:469–492. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2005004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stanczak J et al. Ixodes ricinus as a vector of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Babesia microti in urban and suburban forests. Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine. 2004;11:109–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Santos AS et al. Detection of Anaplasma phagocytophilum DNA in Ixodes ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) from Madeira Island and Setubal District, mainland Portugal. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2004;10:1643–1648. doi: 10.3201/eid1009.040276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parola P et al. Ehrlichial DNA amplified from Ixodes ricinus (Acari: Ixodidae) in France. Journal of Medical Entomology. 1998;35:180–183. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/35.2.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petrovec M et al. Infections of wild animals with Anaplasma phagocytophila in Austria and the Czech Republic. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003;990:103–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bown KJ et al. Seasonal dynamics of Anaplasma phagocytophila in a rodent-tick (Ixodes trianguliceps) system, United Kingdom. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2003;9:63–70. doi: 10.3201/eid0901.020169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alberti A et al. Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Sardinia, Italy. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2005;11:1322–1324. doi: 10.3201/eid1108.050085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bjoersdorff A et al. Ehrlichia-infected ticks on migrating birds. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2001;7:877–879. doi: 10.3201/eid0705.017517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oporto B et al. A survey on Anaplasma phagocytophila in wild small mammals and roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) in Northern Spain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003;990:98–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Skarphedinsson S, Jensen PM, Kristiansen K. Survey of tickborne infections in Denmark. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2005;11:1055–1061. doi: 10.3201/eid1107.041265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cazorla C et al. First isolation of Rickettsia slovaca from a patient, France. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2003;9:135. doi: 10.3201/eid0901.020192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oteo JA et al. Epidemiological and clinical differences among Rickettsia slovaca rickettsiosis and other tick-borne diseases in Spain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003;990:355–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Punda-Polic V et al. Detection and identification of spotted fever group rickettsiae in ticks collected in southern Croatia. Experimental Applied Acarology. 2002;28:169–176. doi: 10.1023/a:1025334113190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nielsen H et al. Serological and molecular evidence of Rickettsia helvetica in Denmark. Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2004;36:559–563. doi: 10.1080/00365540410020776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fournier PE et al. Evidence of Rickettsia helvetica infection in humans, eastern France. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2000;6:389–392. doi: 10.3201/eid0604.000412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fournier PE et al. Aneruptive fever associated with antibodies to Rickettsia helvetica in Europe and Thailand. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2004;42:816–818. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.2.816-818.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Raoult D et al. First documented human Rickettsia aeschlimannii infection. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2002;8:748–749. doi: 10.3201/eid0807.010480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fernandez-Soto P, Encinas-Grandes A, Perez-Sanchez R. Rickettsia aeschlimannii in Spain: molecular evidence in Hyalomma marginatum and five other tick species that feed on humans. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2003;9:889–890. doi: 10.3201/eid0907.030077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shpynov SN et al. Molecular identification of a collection of spotted Fever group rickettsiae obtained from patients and ticks from Russia. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2006;74:440–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Sousa R et al. Rickettsia sibirica isolation from a patient and detection in ticks, Portugal. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2006;12:1103–1108. doi: 10.3201/eid1207.051494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Psaroulaki A et al. Simultaneous detection of ‘Rickettsia mongolotimonae’ in a patient and in a tick in Greece. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2005;43:3558–3559. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.7.3558-3559.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Beninati T et al. First detection of spotted fever group rickettsiae in Ixodes ricinus from Italy. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2002;8:983–986. doi: 10.3201/eid0809.020060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sreter-Lancz Z et al. Rickettsiae of the spotted-fever group in ixodid ticks from Hungary: identification of a new genotype (‘Candidatus Rickettsia kotlanii’) Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology. 2006;100:229–236. doi: 10.1179/136485906X91468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Di rique Gouriet F, Rolain JM, Raoult D. Rickettsia slovaca infection, France. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2006;12:521–523. doi: 10.3201/eid1203.050911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jaenson TG et al. Geographical distribution, host associations, and vector roles of ticks (Acari: Ixodidae, Argasidae) in Sweden. Journal of Medical Entomology. 1994;31:240–256. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/31.2.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Papa A et al. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in Bulgaria. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2004;10:1465–1467. doi: 10.3201/eid1008.040162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Papa A et al. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in Albania, 2001. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2002;21:603–606. doi: 10.1007/s10096-002-0770-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Papa A et al. Genetic detection and isolation of crimean-congo hemorrhagic fever virus, Kosovo, Yugoslavia. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2002;8:852–854. doi: 10.3201/eid0808.010448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ergonul O. Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever. Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2006;6:203–214. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70435-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yashina L et al. Genetic variability of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever virus in Russia and Central Asia. Journal of General Virology. 2003;84:1199–1206. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.18805-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yashina L et al. Genetic analysis of Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic fever virus in Russia. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2003;41:860–862. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.2.860-862.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lundkvist A et al. Dobrava hantavirus outbreak in Russia. Lancet. 1997;350:781–782. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)62565-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Markotic A et al. Characteristics of Puumala and Dobrava infections in Croatia. Journal of Medical Virology. 2002;66:542–551. doi: 10.1002/jmv.2179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Olsson GE et al. Human hantavirus infections, Sweden. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2003;9:1395–1401. doi: 10.3201/eid0911.030275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pal E, Strle F, Avsic-Zupanc T. Hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in the Pomurje region of Slovenia – an 18-year survey. Wiener klinische Wochenschrift. 2005;117:398–405. doi: 10.1007/s00508-005-0359-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Alexeyev OA et al. Hantaan and Puumala virus antibodies in blood donors in Samara, an HFRS-endemic region in European Russia. Lancet. 1996;347:1483. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)91717-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sauvage F et al. Puumala hantavirus infection in humans and in the reservoir host, Ardennes region, France. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2002;8:1509–1511. doi: 10.3201/eid0812.010518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mailles A et al. Larger than usual increase in cases of hantavirus infections in Belgium, France and Germany, June 2005. http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ew/2005/050721.asp#4. Eurosurveillance. 2005;10(7) doi: 10.2807/esw.10.29.02754-en. ): E050721.4 ( [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cvetko L et al. Puumala virus in Croatia in the 2002 HFRS outbreak. Journal of Medical Virology. 2005;77:290–294. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rose AM et al. Patterns of Puumala virus infection in Finland. Eurosurveillance. 2003;8:9–13. doi: 10.2807/esm.08.01.00394-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schneider F, Mossong J. Increased hantavirus infections in Luxembourg, August 2005. http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ew/2005/050825.asp#1. Eurosurveillance. 2005;10(8) doi: 10.2807/esw.10.34.02781-en. ): E050825.1 ( [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hoier S et al. Puumala virus RNA in patient with multiorgan failure [Letter] Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2006;12 doi: 10.3201/eid1202.050634. : E050634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Garanina SB ICEID; Atlanta, Georgia, USA: 2006. Investigation of Hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome outbreak in Udmutria, Russia. , 19–22 March, . Poster session 46: Hemorrhagic fever. Abstract 275. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lindgren E, Gustafson R. Tick-borne encephalitis in Sweden and climate change. Lancet. 2001;358:16–18. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)05250-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Peyrefitte CN et al. Toscana virus and acute meningitis, France. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2005;11:778–780. doi: 10.3201/eid1105.041122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sanbonmatsu-Gamez S et al. Toscana virus in Spain. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2005;11:1701–1707. doi: 10.3201/eid1111.050851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hemmersbach-Miller M et al. Sandfly fever due to Toscana virus: an emerging infection in southern France. European Journal of Internal Medicine. 2004;15:316–317. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Charrel RN et al. Emergence of Toscana virus in Europe. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2005;11:1657–1663. doi: 10.3201/eid1111.050869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.International Scientific Working group on TBE. http://www.tbe-info.com. http://www.tbe-info.com ). Accessed 15 August 2006.

- 81.Kerbo N, Donchenko I, Kutsar K. Tickborne encephalitis outbreak in Estonia linked to raw goat milk, May–June 2005. http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ew/2005/050623.asp#2. Eurosurveillance. 2005;10(6) doi: 10.2807/esw.10.25.02730-en. ): E050623.2 ( [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Beran J. Tickborne encephalitis in Europe: Czech Republic, Lithuania and Latvia. http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ew/2004/040624.asp#3 Eurosurveillance Weekly. 2004;6(26) ): 040624 ( [Google Scholar]

- 83.Strauss R et al. Tickborne encephalitis in Europe: basic information, country by country. http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ew/2004/040715.asp#2 Eurosurveillance Weekly. 2004;7(29) (Editorial team). ): 040715 ( [Google Scholar]

- 84.Csango PA et al. Tick-borne encephalitis in southern Norway. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2004;10:533–534. doi: 10.3201/eid1003.020734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Daniel M et al. Shift of the tick Ixodes ricinus and tick-borne encephalitis to higher altitudes in central Europe. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2003;22:327–328. doi: 10.1007/s10096-003-0918-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jaenson TG et al. Geographical distribution, host associations, and vector roles of ticks (Acari: Ixodidae, Argasidae) in Sweden. Journal of Medical Entomology. 1994;31:240–256. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/31.2.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Daniel M et al. An attempt to elucidate the increased incidence of tick-borne encephalitis and its spread to higher altitudes in the Czech Republic. International Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2004;293:55–62. doi: 10.1016/s1433-1128(04)80009-3. (Suppl. 37): [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Stefanoff P et al. Evaluation of tickborne encephalitis case classification in Poland. Eurosurveillance. 2005;10:23–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gunther G, Lindquist L. Surveillance of tickborne encephalitis in Europe and case definition. Eurosurveillance. 2005;10:23–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Murgue B et al. West Nile in the Mediterranean basin: 1950–2000. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2001;951:117–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb02690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hubalek Z, Halouzka J. West Nile fever – a reemerging mosquito-borne viral disease in Europe. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 1999;5:643–650. doi: 10.3201/eid0505.990505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Platonov AE. West Nile encephalitis in Russia 1999–2001: were we ready? Are we ready? Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2001;951:102–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb02689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Del Giudice P et al. Human West Nile virus, France. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2004;10:1885–1886. doi: 10.3201/eid1010.031021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zeller HG, Schuffenecker I. West Nile virus: an overview of its spread in Europe and the Mediterranean basin in contrast to its spread in the Americas. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Inectious Diseases. 2004;23:147–156. doi: 10.1007/s10096-003-1085-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Connell J et al. Two linked cases of West Nile virus (WNV) acquired by Irish tourists in the Algarve, Portugal. http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ew/2004/040805.asp#1 Eurosurveillance Weekly. 2004;8(32) ): 040805 ( [Google Scholar]

- 96.Charrel RN et al. Evolutionary relationship between Old World West Nile virus strains. Evidence for viral gene flow between Africa, the Middle East, and Europe. Virology. 2003;315:381–388. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00536-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hayes EB et al. Epidemiology and transmission dynamics of West Nile virus disease. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2005;11:1167–1173. doi: 10.3201/eid1108.050289a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Autorino GL et al. West Nile virus epidemic in horses, Tuscany region, Italy. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2002;8:1372–1378. doi: 10.3201/eid0812.020234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bakonyi T et al. Novel flavivirus or new lineage of West Nile virus, central Europe. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2005;11:225–231. doi: 10.3201/eid1102.041028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Beasley DW et al. Limited evolution of West Nile virus has occurred during its southwesterly spread in the United States. Virology. 2003;309:190–195. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00150-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kurkela S et al. Causative agent of Pogosta disease isolated from blood and skin lesions. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2004;10:889–894. doi: 10.3201/eid1005.030689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Laine M et al. The prevalence of antibodies against Sindbis-related (Pogosta) virus in different parts of Finland. Rheumatology. 2003;42:632–636. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Editorial team. Avian influenza H5N1 detected in German poultry and a United Kingdom wild bird. http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ew/2006/060406.asp#1. Eurosurveillance. 2006;11(4) ): E060406.1 ( [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Liu J et al. Highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza virus infection in migratory birds. Science. 2005;309:1206. doi: 10.1126/science.1115273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ducatez MF et al. Avian flu: multiple introductions of H5N1 in Nigeria. Nature. 2006;442:37. doi: 10.1038/442037a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Coulombier D, Ekdahl K. H5N1 influenza and the implications for Europe. British Medical Journal. 2005;331:413–414. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7514.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Quoilin S et al. Management of potential human cases of influenza A/H5N1: lessons from Belgium. http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ew/2006/060126.asp. Eurosurveillance Weekly. 2006;11 doi: 10.2807/esw.11.04.02885-en. : E060126 ( [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Editorial team. Avian influenza in Turkey: 21 confirmed human cases. http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ew/2006/060119.asp#1. Eurosurveillance. 2006;11 : E060119.1 ( [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Giesecke J. Human cases of avian influenza in eastern Turkey: the weather factor. http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ew/2006/060119.asp#2. Eurosurveillance. 2006;11 doi: 10.2807/esw.11.03.02877-en. : E060119.2 ( [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Will RG et al. A new variant of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in the UK. Lancet. 1996;347:921. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)91412-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Britton et al. Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in a 16-year-old in the UK [Letter] Lancet. 1995;346:1155. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91827-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Chazot G et al. New variant of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in a 26-year-old French man [Letter; Comment] Lancet. 1996;347:1181. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90638-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Colchester AC, Colchester NT. The origin of bovine spongiform encephalopathy: the human prion disease hypothesis. Lancet. 2005;366:856–861. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67218-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Collinge J. Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Lancet. 1999;354:317. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)05128-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ward HJ et al. Risk factors for variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: a case-control study. Annals of Neurology. 2006;59:111. doi: 10.1002/ana.20708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.The BSE inquiry. http://www.bse.org.uk http://www.bse.org.uk

- 117.variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease 2007. http://www.eurocjd.ed.ac.uk/vcjdworldeuro.htm. http://www.eurocjd.ed.ac.uk/vcjdworldeuro.htm . Current data February . ). Accessed 16 March 2007.

- 118.Llewelyn et al. Possible transmission of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease by blood transfusion. Lancet. 2004;363:417. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15486-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Peden AH et al. Preclinical vCJD after blood transfusion in a PRNP codon 129 heterozygous patient. Lancet. 2004;364:527. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16811-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Bird SM. Attributable testing for abnormal prion protein, database linkage, and blood-borne vCJD risks. Lancet. 2004;364:1362. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17194-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ludlam CA, Turner ML. Managing the risk of transmission of variant Creutzfeldt Jakob disease by blood products. British Journal of Haematology. 2006;132:13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Perevoscikovs J et al. Trichinellosis outbreak in Latvia linked to bacon bought at a market, January–March 2005. http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ew/2005/050512.asp#2. Eurosurveillance. 2005;10(5) doi: 10.2807/esw.10.19.02702-en. ): E050512.2 ( [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Bartuliene A, Jasulaitiene V, Malakauskas A. Human trichinellosis in Lithuania 1990–2004. http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ew/2005/050714.asp#6. Eurosurveillance. 2005;10(7) ): E050714.6 ( [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Pozio E. New patterns of Trichinella infection. Veterinary Parasitology. 2001;98:133–148. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(01)00427-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ozeretskovskaya NN et al. New trends and clinical patterns of human trichinellosis in Russia at the beginning of the XXI century. Veterinary Parasitology. 2005;132:167–171. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2005.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Djordjevic M et al. The need for implementation of International Commission on Trichinellosis recommendations, quality assurance standards, and proficiency sample programs in meat inspection for trichinellosis in Serbia. Veterinary Parasitology. 2005;132:185–188. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2005.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Cortes-Blanco M et al. Outbreak of trichinellosis in Caceres, Spain, December 2001–February 2002. Eurosurveillance. 2002;7:136–138. doi: 10.2807/esm.07.10.00362-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Gomez-Garcia V, Hernandez-Quero J, Rodriguez-Osorio M. Short report: Human infection with Trichinella britovi in Granada, Spain. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2003;68:463–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Gari-Toussaint M et al. Human trichinellosis due to Trichinella britovi in southern France after consumption of frozen wild boar meat. Eurosurveillance. 2005;10:117–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Pozio E et al. Trichinella pseudospiralis foci in Sweden. Veterinary Parasitology. 2004;125:335–342. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Hurnikova Z et al. First record of Trichinella pseudospiralis in the Slovak Republic found in domestic focus. Veterinary Parasitology. 2005;128:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Janovsky M et al. Echinococcus multilocularis in a European beaver from Switzerland. Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 2002;38:618–620. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-38.3.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Boucher JM et al. Detection of Echinococcus multilocularis in wild boars in France using PCR techniques against larval form. Veterinary Parasitology. 2005;129:259–266. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Martinek K et al. Echinococcus multilocularis in European wolves (Canis lupus) Parasitology Research. 2001;87:838–839. doi: 10.1007/s004360100452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Hofer S et al. High prevalence of Echinococcus multilocularis in urban red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) and voles (Arvicola terrestris) in the city of Zurich, Switzerland. Parasitology. 2000;120:135–142. doi: 10.1017/s0031182099005351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Sreter T et al. Echinococcus multilocularis: an emerging pathogen in Hungary and Central Eastern Europe? Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2003;9:384–386. doi: 10.3201/eid0903.020320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Moks E, Saarma U, Valdmann H. Echinococcus multilocularis in Estonia. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2005;11:1973–1974. doi: 10.3201/eid1112.050339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Deplazes P et al. Wilderness in the city: the urbanization of Echinococcus multilocularis. Trends of Parasitology. 2004;20:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Deplazes P, Eckert J. Veterinary aspects of alveolar echinococcosis – a zoonosis of public health significance. Veterinary Parasitology. 2001;98:65–87. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(01)00424-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Kern P et al. European echinococcosis registry: human alveolar echinococcosis, Europe, 1982–2000. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2003;9:343–349. doi: 10.3201/eid0903.020341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Mendez Martinez C et al. Brucellosis outbreak due to unpasteurized raw goat cheese in Andalucia (Spain), January–March 2002. Eurosurveillance. 2003;8:164–168. doi: 10.2807/esm.08.07.00421-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Al Dahouk S et al. Human brucellosis in a nonendemic country: a report from Germany, 2002 and 2003. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2005;24:450–456. doi: 10.1007/s10096-005-1349-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Malik AN et al. Changing pattern of visceral leishmaniasis, United Kingdom, 1985–2004. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2006;12:1257–1259. doi: 10.3201/eid1208.050486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Desjeux P, Alvar J. Leishmania/HIV co-infections: epidemiology in Europe. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology. 2003;97:3–15. doi: 10.1179/000349803225002499. (Suppl. 1): [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Gabutti G et al. Visceral leishmaniasis in Liguria, Italy. Lancet. 1998;351:1136. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)79424-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.WHO. Urbanization: an increasing risk factor for leishmaniasis. http://www.who.int/wer. Weekly Epidemiological Record. 2002;77:365–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Ferroglio E et al. Canine leishmaniasis, Italy. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2005;11:1618–1620. doi: 10.3201/eid1110.040966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Paradies P et al. Incidences of canine leishmaniasis in an endemic area of southern Italy. Journal of Veterinary Medicine, B: Infectious Diseases and Veterinary Public Health. 2006;53:295–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.2006.00964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Lindgren E, Talleklint L, Polfeldt T. Impact of climatic change on the northern latitude limit and population density of the disease-transmitting European tick Ixodes ricinus. Environmental health perspectives. 2000;108:119–123. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.McMichael AJ, Woodruff RE, Hales S. Climate change and human health: present and future risks. Lancet. 2006;367:859–869. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Cinco M et al. Seroprevalence of tick-borne infections in forestry rangers from northeastern Italy. Clinical Microbiology and Infection (the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases) 2004;10:1056–1061. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.01026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Foucault C et al. Bartonella quintana bacteremia among homeless People. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2002;35:684–689. doi: 10.1086/342065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Fournier PE et al. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of Bartonella quintana and Bartonella henselae endocarditis: a study of 48 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2001;80:245–251. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200107000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Santos R et al. Bacillary angiomatosis by Bartonella quintana in an HIV-infected patient. Journal of American Academy of Dermatology. 2000;42:299–301. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(00)90147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Ruscio M, Cinco M. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Italy: first report on two confirmed cases. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003;990:350–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Remy V et al. Human anaplasmosis presenting as atypical pneumonitis in France. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2003;37:846–848. doi: 10.1086/377502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Arnez M et al. Causes of febrile illnesses after a tick bite in Slovenian children. Pediatric Infectious Diseases Journal. 2003;22:1078–1083. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000101477.90756.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Oteo JA et al. First report of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis from southern Europe (Spain) Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2000;66:430–432. doi: 10.3201/eid0604.000425. . [Erratum in: (2000) 562 and 663.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Bjoersdorff A et al. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis as a common cause of tick-associated fever in Southeast Sweden: report from a prospective clinical study. Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2002;34:187–191. doi: 10.1080/00365540110080061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Baumann D et al. Fever after a tick bite: clinical manifestations and diagnosis of acute tick bite-associated infections in northeastern Switzerland [in German] Deutsche medizinische Wochenschrift. 2003;128:1042–1047. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-39103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Raoult D et al. Spotless rickettsiosis caused by Rickettsia slovaca and associated with Dermacentor ticks. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2002;34:1331–1336. doi: 10.1086/340100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Karti SS et al. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in Turkey. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2004;10:1379–1384. doi: 10.3201/eid1008.030928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Papa A, Bojovic B, Antoniadis A. Hantaviruses in Serbia and Montenegro. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2006;12:1015–1018. doi: 10.3201/eid1206.051564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Defuentes G et al. Acute meningitis owing to phlebotomus fever Toscana virus imported to France. Journal of Travel Medicine. 2005;12:295–296. doi: 10.2310/7060.2005.12512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Haglund M. Occurrence of TBE in areas previously considered being non-endemic: Scandinavian data generate an international study by the International Scientific Working Group for TBE (ISW-TBE) International Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2002;291:50–54. doi: 10.1016/s1438-4221(02)80010-8. (Suppl. 33): [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Regnery RL, Childs JE, Koehler JE. Infections associated with Bartonella species in persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1995;21:S94–98. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.supplement_1.s94. (Suppl. 1): [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Trevejo RT, Barr MC, Robinson RA. Important emerging bacterial zoonotic infections affecting the immunocompromised. Veterinary Research. 2005;36:493–506. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2005011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Alberti A et al. Equine and canine Anaplasma phagocytophilum strains isolated on the island of Sardinia (Italy) are phylogenetically related to pathogenic strains from the United States. Applied Environmental Microbiology. 2005;71:6418–6422. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.10.6418-6422.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Olsson GE et al. Habitat factors associated with bank voles (Clethrionomys glareolus) and concomitant hantavirus in northern Sweden. Vector Borne Zoonotic Diseases. 2005;5:315–323. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2005.5.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Malkinson M, Banet C. The role of birds in the ecology of West Nile virus in Europe and Africa. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 2002;267:309–322. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-59403-8_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Martin V et al. Epidemiology and ecology of highly pathogenic avian influenza with particular emphasis on South East Asia. Developments in Biologicals. 2006;124:23–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Gambaryan A et al. Evolution of the receptor binding phenotype of influenza A (H5) viruses. Virology. 2006;344:432–438. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Wan XF et al. Genetic characterization of H5N1 avian influenza viruses isolated in southern China during the 2003–04 avian influenza outbreaks. Archives of Virology. 2005;150:1257–1266. doi: 10.1007/s00705-004-0474-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Taubenberger JK et al. Characterization of the 1918 influenza virus polymerase genes. Nature. 2005;437:889–893. doi: 10.1038/nature04230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Sims LD et al. Origin and evolution of highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza in Asia. Veterinary Record. 2005;157:159–164. doi: 10.1136/vr.157.6.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Gabriel G et al. The viral polymerase mediates adaptation of an avian influenza virus to a mammalian host. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2005;102:18590–18595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507415102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.World Health Organization. Global Influenza Program Surveillance Network. Evolution of H5N1 avian influenza viruses in Asia. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2005;11:1515–1521. doi: 10.3201/eid1110.050644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]