Abstract

Purpose

To determine the morphological patterns of angiographic macular edema using simultaneous co-localization of fluorescein angiograms (FA) and spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) images in diabetes, epiretinal membrane, uveitic and pseudophakic cystoid macular edema and vein occlusion.

Methods

87 consecutive patients (107 eyes) with macular edema from five different etiologies were imaged by simultaneous SLO/OCT to study the morphological patterns of edema on SD-OCT and then correlated/co localized with the FA patterns of leakage. Statistical analysis was done to analyze the differences in the morphological OCT pattern by different disease.

Results

SD-OCT characteristics of macular edema showed a significant difference across different diseases (p = 0.037). Cystic fluid pockets were found to be more commonly seen in patients with DME and retinal vein occlusions whereas those cases with macular edema secondary to ERM revealed non-cystic changes on OCT. 70 of the 107 eyes had diffuse angiographic leakage and rest of the 37 eyes had cystoid leakage on angiography. Of the 70 eyes with diffuse leakage, 24.28% showed microcysts on SD-OCT in the area of edema and 70% eyes had diffuse thickening or distorted architecture without cyst. All 37 eyes with cystoid leakage showed cysts in the area of edema by SD-OCT. 3.73% of eyes with FA leakage had no abnormality on SD-OCT.

Conclusions

Eyes with DME and retinal vein occlusions have a significantly higher incidence of cyst formation on SD-OCT. There was no correlation between visual acuity and cyst formation. Diffuse non-cystoid angiographic macular edema may show micro cysts on SD-OCT, but diffuse edema is more commonly associated with thickening or distortion of the retinal layers without cyst formation. Cystoid leakage on FA is always associated with cystic changes on SD-OCT.

INTRODUCTION

Macular edema is a common cause of decreased visual acuity in many ophthalmic diseases. It results from disruption of the blood-retinal barrier and subsequent accumulation of fluid leading to increased retinal thickness.1 Fluorescein Angiography (FA) and Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) are commonly used in conjunction with each other for the diagnosis of macular edema. FA identifies the anatomical location and pattern of vascular leakage, and is a qualitative and functional study, whereas OCT allows a morphological assessment of macular edema by producing two or three-dimensional images of the retinal tissue.2 Several prior reports have used time domain OCT to describe the morphological characteristics of macular edema in different etiologies,3, 4, 5, 6 and also to monitor treatment response of Anti-VEGF drugs for wet AMD.7, 8, 9

Correlating information obtained by FA and OCT is important to help understand the pathophysiology of macular edema, and several recent studies have addressed this issue.10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 Interestingly, some authors found that macular edema detected by either FA or time domain OCT was occasionally not present on the other imaging modality.13, 16 Similarly, we previously reported that patients with macular edema could have FA leakage with normal appearing macular time domain OCT scans.16 Our hypothesis in these situations was that fluorescein staining of non-cystoid edema is diffuse, irregular and not confined to well demarcated spaces which could therefore be missed by time domain OCT, but might be visible with higher resolution spectral domain (SD) OCT.16

SD-OCT allows the study of structural alterations in the different retinal layers and subtle changes associated with disease processes.17 The high resolution and speed of SD-OCT and the ability, with certain instruments, to use simultaneous scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (SLO) to co-localize angiographic findings with OCT images, makes these machines ideal candidates to study the correlations between angiographic features and SD-OCT morphology in macular edema. A recent study on the subject by Bolz et al.12 defined angiographic leakage patterns such petalloid, honeycomb, or diffuse, and associated these with SD-OCT changes such as cystic spaces or diffuse pooling. This self-described “pilot study” indicated that relationships exist between angiographic leakage and retinal changes on SD-OCT, but the report included only 10 eyes with DME and was performed with digital image superimposition instead of simultaneous SLO fluorescein angiography and SD-OCT to guarantee accurate co-localization of pathology. We therefore correlated different angiographic leakage patterns to SD-OCT morphology in 107 eyes with macular edema of different etiologies. We performed precise co-localization of retinal pathology using simultaneous image acquisition, and high resolution SD-OCT for accurate visualization of changes in the retinal architecture.

METHODS

We retrospectively reviewed the charts of 107 consecutive patients with macular edema on fluorescein angiography who underwent confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope (cSLO) FA/OCT scans at the University of California at San Diego Jacobs Retina Center. All patients included in our study had a thorough clinical examination with best corrected visual acuity by ETDRS chart, indirect ophthalmoscopy and fundus photography. The study was Institutional Review Board approved, and informed consent for all imaging was taken from study patients

All study FA and SD-OCT images were acquired with the Spectralis HRA/OCT, Heidelberg Retinal Angiograph (Heidelberg engineering, Heidelberg Germany). The Spectralis combines high-resolution SD-OCT with a scanning laser ophthalmoscope (SLO), and allows for simultaneous OCT scans with FA imaging, infrared imaging, or indocyanine green (ICG) angiography.

Identified etiologies of macular edema included DME, epiretinal membrane (ERM), vascular occlusions, uveitis, and post-cataract extraction macular edema. Patients with macular edema showing definite leakage on fluorescein angiograms were included in the study. Simultaneously acquired FA and OCT scans passing through the center of the macula were chosen for classification. In the few cases where leakage on the angiogram was parafoveal, we assured that the scan used for analysis passed through the area of leakage. The SD-OCT SLO we used (Heidelberg Spectralis) is provided with retinal tracking technology, which enables real time, simultaneous imaging while tracking and correcting for eye movements. In addition, the automatic cursor provided on the instrument was also used to confirm site to site correlation. All the analyses were performed by two trained observers (MB, IK). In cases of discrepancy between the two, a third reviewer made the final decision. Poor quality images were excluded from the study.

We classified leakage patterns on FA into either diffuse or cystoid. Consistent with prior studies, diffuse leakage was defined as late widespread leakage, not confined to well demarcated spaces involving the foveal or parafoveal areas (Figure 1–5).12, 18 Cystoid leakage included petalloid or honeycombed patterns of hyperfluorescence, and featured dye pooling in well-defined foveal or parafoveal spaces (Figure 6).

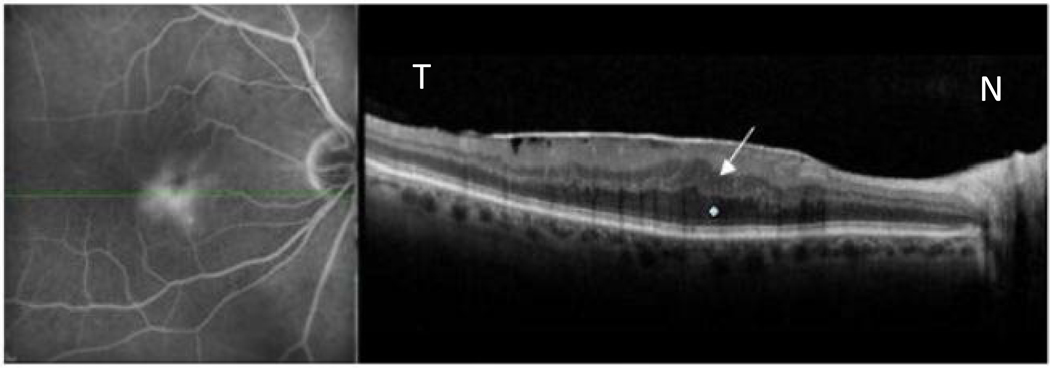

Figure 1.

Idiopathic epiretinal membrane with macular edema in 67 year old male as imaged by simultaneous scanning laser ophthalmoscope/ spectral domain optical coherence tomography.(SLO/ Spectral OCT).Late phase fluorescein angiogram (left image) shows diffuse non cystoid leakage with straightening of retinal vessels. Green line indicates OCT scan location. B-scan OCT (right image) shows thickening of the outer nuclear layer ONL (white star) and inner nuclear layer (INL) layers (white arrow).

Note that there are no cystic fluid pockets seen.

N-nasal, T- temporal.

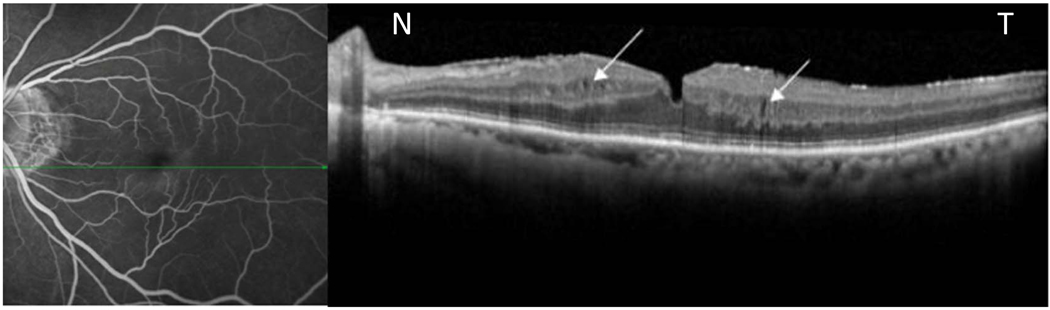

Figure 5.

Late fluorescein angiogram (left image) reveals late parafoveal diffuse leakage in a patient with an epiretinal membrane. Corresponding horizontal OCT scan passing through the inferior parafoveal region (area of leakage) shows thickening of inner nuclear layer (INL) and outer nuclear layers with faintly

Visible cystic spaces in INL layer. (White arrows).

N-nasal, T- temporal.

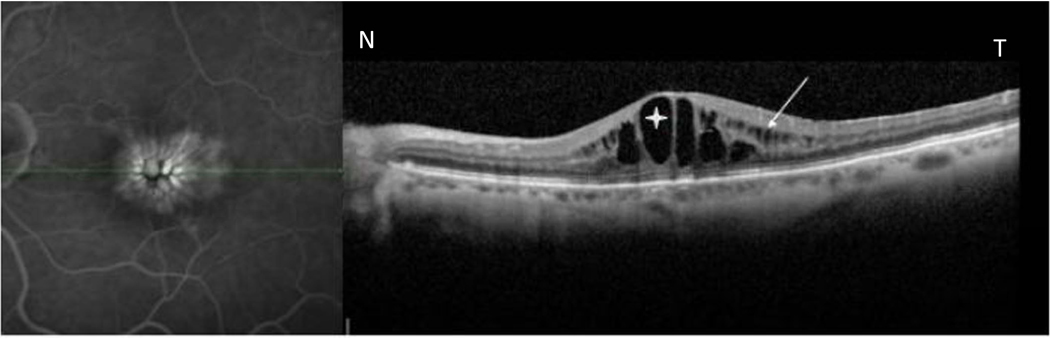

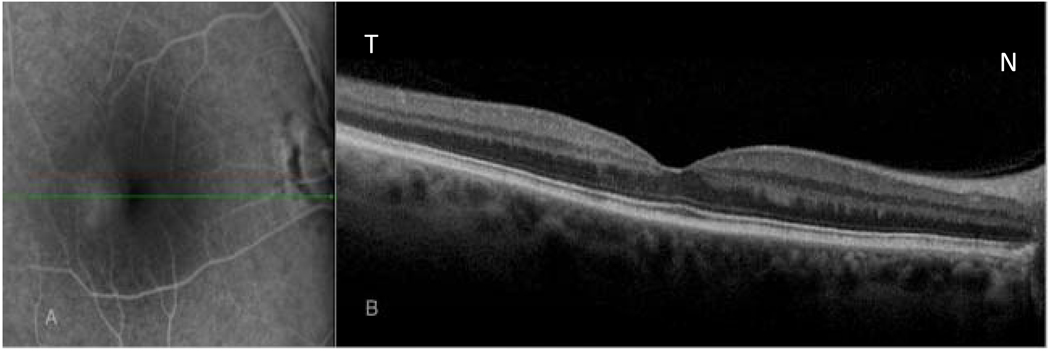

Figure 6.

Simultaneously acquired late phase fluorescein angiogram (FA) and spectral domain optical coherence tomography (Spectral- OCT) scan using simultaneous scanning laser ophthalmoscope /spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SLO- Spectral OCT) in a patient with uveitic cystoid macular edema (CME). FA image (left) shows central petalloid and honeycomb pattern of hyperfluorescence corresponding to cystoid spaces in outer nuclear layer/outer plexiform layer(asterix) and inner nuclear layer(white arrows).

N-nasal, T- temporal.

OCT scans obtained through simultaneous FA/OCT were used for a detailed comparative analysis of leakage on FA and corresponding retinal morphological patterns on SD-OCT. Both horizontal and vertical scans passing through the center of the area of leakage were analyzed. Gray scale images of each OCT was studied. The OCT scan was classified into a cystic or non-cystic group. The cystic group showed the presence of well-defined cystic fluid pockets, which were round hypo-reflective lacunae with well-defined boundaries seen in the retinal layers. In addition, the size of cysts (smallest and largest) in microns was measured using the digital image and scale of the OCT in the antero-posterior dimension. The non-cystic group had retinal layer thickening either localized or diffuse in one or more retinal layers and/or distorted retinal architecture. Foveal retinal thickness was analyzed only for those patients who showed normal retinal morphology on SD-OCT. Table 1 and 2 summarizes the various types of retinal changes assessed with OCT in the areas of leakage.

Table 1.

| Table 1a. Fluorescein angiogram (FA) findings and corresponding morphological type of macular edema as seen on Spectral domain optical coherence tomography.(SD-OCT ) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Edema on OCT | ||||

| FA Leakage |

Cystic† | Non Cystic* |

Normal | Total |

| Diffuse (70) |

17 | 49 | 4 | 70 |

| Cystoid (37) |

37 | 0 | 0 | 37 |

| Table 1b: Types of Non Cystic Optical coherence tomography (OCT) Findings on Spectral domain( SD- OCT) in patients with diffuse angiographic leakage. | |

|---|---|

| OCT Findings | Number |

| Thickened Retina* | 38 |

| Distorted Retina + | 11 |

| Total | 49 |

Cystic- well defined hypo reflective cysts seen in the retinal layers.

• Thickened retina and/or distorted retina layers without cystic fluid pockets.

Thickening of the retinal layers (localized or diffuse) with preservation of retinal layer morphology

Normal morphology of retinal layers is lost

Table 2.

Morphological types of edema based on the etiology in eyes with macular edema as seen on Spectral domain Optical coherence tomography.(SD- OCT).

| Etiology | Cystic | Non Cystic | Normal | Total | Mean ETDRS letters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DME | 25 | 19 | 3 | 47 | 45.21+−19.99 |

| ERM | 8 | 21 | 1 | 30 | 45.76+−13.2 |

| RVO | 11 | 3 | 0 | 14 | 31.5+−16.4 |

| Uveitis | 8 | 4 | 0 | 12 | 55.17+−19.99 |

| Post surgery | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 26.65+−17.5 |

| P value( GEE) | 0.037 | P value= 0.1 | |||

DME= diabetic macular edema, ERM-=epiretinal membrane, RVO= Retinal vein occlusions

Statistical analysis was performed to identify any significant difference in the OCT morphological characteristics of macular edema across different etiologies. Because many patients had both eyes included in this study, generalized estimating equations (GEE) were used to take into account any intra-patient correlation. Cystic and non-cystic changes on OCT were coded as binary variables and GEE with a binomial distribution were used to model the probability of OCT cystic change across the different etiologies. In addition, visual acuity in ETDRS letters was recorded in all patients and Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel statistical analysis was performed to examine the association between visual acuity and OCT cystic change while controlling for etiology.

RESULTS

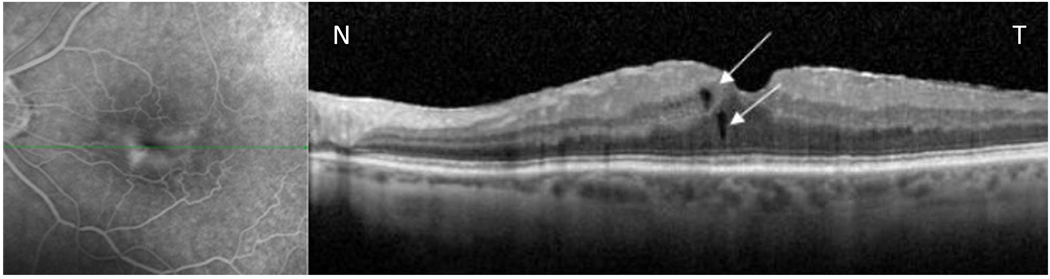

Of the 107 eyes, 70 had diffuse leakage on FA and OCT disclosed small cystic fluid pockets (microcysts) in 17 of these eyes (24.28%) (Figure 4 and 5) and non-cystic changes in 49 (70%) (Table 1a). The microcysts were not seen on the angiogram in any of these cases. The cystic fluid pockets were round hypo-reflective lacunae with well-defined boundaries. The sizes ranged from 6 microns to 113 microns. Amongst the eyes showing non-cystic changes on OCT, thickening of the inner nuclear and outer nuclear layers either localized or diffuse was found in 38 cases (Figure 1). The remaining 11 eyes showed distorted retinal architecture (Figure 2 and Table 1b). 4 eyes with evidence of diffuse leakage on FA did not show any changes on SD-OCT (Figure 3). The central foveal thickness of these 4 eyes ranged from 259 µm to 295 µm (Normal values− 270.2 ± 22.5 µm).19

Figure 4.

Simultaneous scanning laser ophthalmoscope /spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SLO- Spectral OCT) in a patient with macular edema secondary to epiretinal membrane. Late phase fluorescein angiogram (left image) shows ill defined diffuse leakage with straightening of the retinal vessels in the perifoveal area. B-scan spectral domain optical coherence tomography (Spectral -OCT) scan through the area of leakage reveals few small microcysts. (As is shown by white arrows)Note: Thin ERM coursing over the retinal surface is also seen in the OCT scan.

N-nasal, T- temporal.

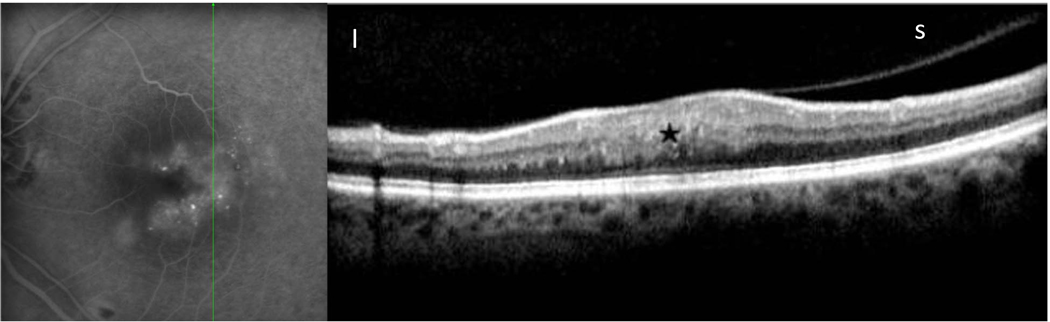

Figure 2.

Late phase fluorescein angiography (FA) image with a simultaneously acquired Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (Spectral-OCT) scan in a diabetic. FA image (left) shows diffuse non cystoid leakage with few leaking microaneurysms. Parafoveal OCT scan located as indicated in the FA image (green line). Correlation shows diffuse swelling of the retinal layers with distorted architecture of the retinal morphology (Black star).Partial posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) also seen with early hyaloi separation seen superiorly. I-inferior, S-superior

Figure 3.

Simultaneous fluorescein angiogram and spectral domain optical coherence tomography (Spectral - OCT) images from a patient with diabetic macula edema. A, Late phase fluorescein angiogram shows ill defined diffuse leakage temporal to the fovea. B, Corresponding OCT image through the area of leakage. B-scan OCT shows normal retinal morphology

Central foveal thickness was 275µm.

N-nasal, T- temporal.

The morphological patterns of macular edema on SD-OCT showed a significant difference across different etiologies including DME, uveitic macular edema, epiretinal membranes, vascular occlusions, and post-operative CME (p = 0.037) (Table 2). Visual acuity was not found to be statistically different across the different etiologies (p = 0.1) (Table 2) and there was no correlation between visual acuity and cystic changes on OCT (p = 0.529, r = −0.054).

Finally, comparisons across different edema etiologies reveal that cystic fluid pockets were more common in patients with DME and retinal vein occlusions whereas cases with macular edema secondary to ERM generally revealed non-cystic changes on OCT (p = 0.0204 and 0.0249 respectively) (Table 3a and 3b). Of note, in all 37 eyes with cystoid (petalloid/honeycomb) pattern of FA leakage, OCT revealed multiple cystic pockets in 100% of the cases (Table 1a and Figure 6), and these cysts were usually seen in the inner nuclear layer, outer plexiform and outer nuclear layers of the retina.

Table 3.

| Table 3a. Comparison of Optical coherence tomography (OCT) characteristics of macular edema in Diabetes and Epiretinal membrane. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OCT Characteristics | ||||

| Etiology | Cystic | Non Cystic | Normal | Total |

| DME | 25 | 19 | 3 | 47 |

| 52.17% | 41.3% | 6.52% | 100% | |

| ERM | 8 | 21 | 1 | 30 |

| 24.13% | 72.4% | 3.44% | 100% | |

| Total | 32 | 40 | 3 | 75 |

| p Value: 0.0204,GEE | ||||

| Table 3b: Comparison of Optical coherence tomography (OCT) characteristics of macular edema in Retinal vein occlusions and Epiretinal membrane. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OCT Characteristics | ||||

| Etiology | Cystic | Non Cystic | Normal | Total |

| RVO | 11 | 3 | 0 | 14 |

| 78.5% | 21.42% | 0.0% | 100% | |

| ERM | 8 | 21 | 1 | 30 |

| 26.67% | 70.0% | 3.33% | 100% | |

| Total | 19 | 24 | 1 | 44 |

| p Value: 0.0249,GEE | ||||

DME=Diabetic macular edema, ERM= Epiretinal membrane, OCT= Optical coherence tomography. GEE- Generalized estimating equations.

RVO=Retinal vein occluions, ERM= Epiretinal membrane, OCT= Optical coherence tomography. GEE- Generalized estimating equations.

Discussion

We report the first large-scale study using simultaneous FA/SD-OCT with eye-tracking to evaluate the correlation between angiographic leakage in macular edema with retinal morphology on SD-OCT. Most interestingly, our patients showed significant morphological differences on SD-OCT based on the different causes of edema. Patients with macular edema secondary to epiretinal membrane generally had non-cystic changes on SD-OCT, whereas eyes with DME and retinal vein occlusions showed more cystic changes. This difference may be explained by their different pathogenic mechanisms as there may be more prominent or more chronic vascular leakage in primary retinovascular disease. The amount of fluid normally present in the retina is maintained according to the osmotic and hydrostatic pressure between the retina and the surrounding vasculature, which are compartmentalized by the blood-retinal barrier. A breakdown in the blood-retinal barrier allows fluid to accumulate in cystoid spaces within the retina. In retinal vein occlusions, macular edema results from breakdown of the capillary endothelium associated with increased intravascular hydrostatic pressure. The damaged vessels leak fluid into the intercellular spaces, eventually leading to intraretinal cystoid spaces. Similarly in diabetes, the blood retinal barrier becomes incompetent due to vascular compromise. Another mechanism that has been hypothesized for macular edema emphasizes the role of mechanical factors, such as in epiretinal membranes. According to this theory, local forces induce a release of mediators that lead to a breakdown of the blood-retinal barrier, resulting in macular edema.

Visual acuity was not associated with the presence of cyst formation indicating that the association of etiology with cysts was not being confounded by visual acuity. Visual acuity is a measure of foveal function and thus we hypothesize that it correlates with the number, size, location of the cysts and not just the presence or absence of cysts. Others have already reported that VA is negatively correlated with increased macular thickness for several etiologies of macular edema.20, 21 The majority of our patients had diffuse leakage on FA (70) which showed a few microcysts on OCT in comparison to rest of the 37 eyes which had large multiple cysts.

Our study was a cross-sectional review of macular edema cases and was designed to study the correlation between angiographic leakages and associated morphological changes on Spectral OCT across different etiologies. It is difficult to determine with any accuracy the duration of diabetes, particularly in adult onset cases, as the onset of disease may be years before the diagnosis is made. Our classification of fluorescein leakage into diffuse and cystoid groups has been well accepted in the literature. Diffuse leakage was defined as late ill-defined widespread leakage not demarcated to well-defined spaces involving the fovea as illustrated in Figure 1–5. In the cystoid variant of macular edema (Figure 6), the FA shows a petalloid or honeycombed pattern of hyperfluorescence as a result of dye pooling in the cystoid spaces corresponding to large cyst in OPL and INL layers as seen by OCT.10, 12 Our observations also corroborate these results. A recent report by Bolz et al.12 studied eyes with DME and used digital image superimposition to correlate non-simultaneous FA and OCT. Our study has the advantages of a larger patient population and the use of simultaneous confocal SLO/OCT images.

Diffuse non-cystoid angiographic macular edema showed micro cysts on Spectral OCT, but was more commonly associated with thickening or distortion of the retinal layers without cyst formation. It is possible that scanning laser SD-OCT allows visualization of cystic structures not seen on fluorescein angiography. Since the horizontal resolution of FA images by our SLO is approximately 10–15 microns and that for our spectral domain OCT is 5–7 microns, smaller cystic pockets may be visible on the SD-OCT but missed on FA. However, we did not measure, or try to determine, the volume of individual intra-retinal cysts. Such analysis would require complete serial OCT sectioning of the entire macula, and is beyond the scope of this study.

In 3.73% of the cases of macular edema, we saw no morphological changes whatsoever on SD-OCT. This result highlights the role of FA in imaging macular edema, and suggests that in some cases, even with SD-OCT, fluorescein angiography is a more sensitive determinant of macular edema. While this study was not meant to evaluate the relative sensitivity and specificity of FA and OCT to detect macular edema, we hypothesize that in some patients with diffuse leakage on FA and no changes on OCT, fluid is present throughout the retina to a mild degree and morphologic changes are not detectable.

To summarize, SD SLO/OCT allows simultaneous co-localization of OCT and angiographic images and shows a high correlation between FA leakage patterns and SD-OCT findings. While cysts seen on FA always reveal cysts on SD-OCT, diffuse FA leakage most commonly reveals non-cystic diffuse thickening and/or distortion of the retinal layers although cysts may be seen. We found a statistically significant difference in retinal morphology across different etiologies of macular edema. Cystic fluid pockets are more commonly seen in patients with DME and retinal vein occlusions whereas those cases with macular edema secondary to ERM revealed non-cystic changes on OCT.

Acknowledgments

Study has been supported by NIH grant EY007366, EY01623. : Dr. William R. Freeman is the recipient of the RPB senior scientific investigator award.

Footnotes

content-type="publisher-disclaimer">This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

None of the authors have any financial disclosures

REFERENCES

- 1.Marmor MF. Mechanisms of fluid accumulation in retinal edema. Doc Ophthalmol. 1999;97(3–4):239–249. doi: 10.1023/a:1002192829817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schaudig U, Scholz F, Lerche RC, Richard G. Optical coherence tomography for macular edema. Classification, quantitative assessment, and rational usage in the clinical practice. Ophthalmologe. 2004;101(8):785–793. doi: 10.1007/s00347-004-1054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Catier A, Tadayoni R, Paques M, et al. Characterization of macular edema from various etiologies by optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(2):200–206. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tran TH, de Smet MD, Bodaghi B, et al. Uveitic macular oedema: correlation between optical coherence tomography patterns with visual acuity and fluorescein angiography. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92(7):922–927. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.136846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Otani T, Kishi S, Maruyama Y. Patterns of diabetic macular edema with optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;127(6):688–693. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanchez JG, Garcia RA, Wu L, et al. Optical coherence tomography characteristics of group 2A idiopathic parafoveal telangiectasis. Retina. 2007;27(9):1214–1220. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e318074bc4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emerson MV, Lauer AK, Flaxel CJ, et al. Intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 2007;27(4):439–444. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31804b3e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fong KC, Kirkpatrick N, Mohamed Q, Johnston RL. Intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) for neovascular age-related macular degeneration using a variable frequency regimen in eyes with no previous treatment. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2008;36(8):748–755. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2008.01873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fung AE, Lalwani GA, Rosenfeld PJ, et al. An optical coherence tomography-guided, variable dosing regimen with intravitreal ranibizumab (Lucentis) for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143(4):566–583. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Otani T, Kishi S. Correlation between optical coherence tomography and fluorescein angiography findings in diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(1):104–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soliman W, Sander B, Hasler PW, Larsen M. Correlation between intraretinal changes in diabetic macular oedema seen in fluorescein angiography and optical coherence tomography. Acta Ophthalmol. 2008;86(1):34–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2007.00989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bolz M, Ritter M, Schneider M, et al. A systematic correlation of angiography and high-resolution optical coherence tomography in diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(1):66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Antcliff RJ, Stanford MR, Chauhan DS, et al. Comparison between optical coherence tomography and fundus fluorescein angiography for the detection of cystoid macular edema in patients with uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(3):593–599. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(99)00087-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ozdek SC, Erdinc MA, Gurelik G, et al. Optical coherence tomographic assessment of diabetic macular edema: comparison with fluorescein angiographic and clinical findings. Ophthalmologica. 2005;219(2):86–92. doi: 10.1159/000083266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang SW, Park CY, Ham DI. The correlation between fluorescein angiographic and optical coherence tomographic features in clinically significant diabetic macular edema. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137(2):313–322. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2003.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kozak I, Morrison VL, Clark TM, et al. Discrepancy between fluorescein angiography and optical coherence tomography in detection of macular disease. Retina. 2008;28(4):538–544. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e318167270b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drexler W, Sattmann H, Hermann B, et al. Enhanced visualization of macular pathology with the use of ultrahigh-resolution optical coherence tomography. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121(5):695–706. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.5.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson RN, Schatz H, McDonald HR, et al. Fluorescein angiography: Basic principles and interpretation. In: Ryan SJ, editor. Retina. 3rd ed. Vol 2. St. Louis, Missouri: Mosby Inc; 2001. pp. 875–942. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grover Sandeep, Murthy Ravi K, Brar Vikram S, et al. Normative Data for Macular Thickness by High-Definition Spectral-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography.(Spectralis) Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(2):266–271. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Markomichelakis NN, Halkiadakis I, Pantelia E, et al. Patterns of macular edema in patients with uveitis: qualitative and quantitative assessment using optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(5):946–953. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Otani T, Kishi S, Maruyama Y. Patterns of diabetic macular edema with optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;127(6):688–693. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]