SUMMARY

Cat scratch disease (CSD), bacillary angiomatosis, hepatic peliosis and some cases of bacteraemia, endocarditis, and osteomyelitis are directly caused by some species of the genus Bartonella. The purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence of IgG antibodies against Bartonella henselae in healthy people and to identify the epidemiological factors involved. Serum samples from 218 patients were examined by indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA). Significance levels for univariate statistical analysis were determined by the Mann–Whitney U test, χ2 test and Fisher's exact test. Of 218 patients, 99 were female and 119 male, with a median age of 34·36 years (range 0–91 years). Nineteen (8·7%) reacted with B. henselae antigens. Of all the factors concerning the seroprevalence rate being studied (age, sex, contact with animals, residential area), only age was statistically significant. Our serological data seems to indicate that B. henselae is present in Catalonia and could be transmitted to humans.

INTRODUCTION

The number of zoonotic Bartonella spp. identified in the last 15 years has increased considerably, since the first HIV-infected patient with unusual vascular proliferative lesions of bacillary angiomatosis (BA) was described in 1983 [1]. Of the 21 species of Bartonella currently described, 10 are acknowledged as human pathogen species. B. bacilliformis, B. quintana, and B. henselae are the most frequently described species [2–4], while B. elizabethae, B. vinsonii, B. washoensis, B. grahamii, B. clarridgeiae, B. koehlerae and B. alsatica were recently identified as being responsible for some cases of human infection [5–10]. Cat scratch disease (CSD), BA, hepatic peliosis and some cases of bacteraemia, endocarditis, osteomyelitis, uveitis and neurological disorders are directly caused by some species of the genus Bartonella [11–13]. To determine the real incidence of Bartonella infection, it is necessary to study the seroprevalence in the general population as well as the principal reservoirs and vectors involved in infection transmission. In the present study, we serologically tested 218 samples across Catalonia for evidence of Bartonella spp. antibodies and analysed possible corresponding risk factors for infection.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Geographical area

The study was undertaken in Vallès Occidental, Catalonia, a predominantly urban area near the coast in the northeast of Spain. A total of 11 municipalities (356 266 inhabitants) participated in the study.

Samples

Serum samples from 218 patients who had attended Sabadell Hospital were collected for the survey. The collection of samples took place during a 5-month period, from September to January. The samples include adults undergoing minor surgery and children cared for non-infectious diseases in the Paediatrics Emergency Service.

Taking into account a previous analysis of the actual population of Vallès Occidental regarding sex, age and residential area, subjects were selected in order to obtain a representative sample. Thus, the study population was stratified by sex, by age (0–14 years, 15–29 years, 30–44 years, 45–64 years, ⩾65 years) and by residential area: rural (<5000 inhabitants), semi-rural (5000–50 000), and urban (>50 000).

Informed consent was obtained from all adult participants and from parents or legal guardians of minors. Each patient completed a questionnaire in which the following variables were registered: age, gender, place of residence, contact with pets, stray dogs, and occupation. Those inhabitants unable to answer the epidemiological survey were excluded.

The sample of heparinized blood was sedimented and the supernatant was collected and stored at −80°C. A serological survey was carried out according to the ethical guidelines of the ethics committee of Sabadell Hospital.

Serological technique

Human serum samples were evaluated by indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA). We used commercial slides (Bartonella IFA IgG; Focus Technologies Inc., Herndon, VA, USA) to determine antibodies to Bartonella spp. The kit for detecting IgG antibodies utilizing Vero cells infected with either B. henselae or B. quintana was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. The serum samples were initially diluted 1/64. Any serum samples found to be positive at the initial dilution were further titrated. Positive and negative controls were included in each test. We considered specimens showing no fluorescence at IgG titres of 1/64 as negative and specimens with bright fluorescence at a dilution of ⩾1/64 as positive. The intensity of each specific fluorescence test was subjectively evaluated and independently graded by two of the authors [14].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 14.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) Seroprevalence was determined globally and by residential area. A univariate analysis was performed to determine possible risk factors. Univariate group comparisons were performed using χ2 and Fisher's exact test. Group differences were determined by odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals. Quantitative variables were compared by Mann–Whitney U test. A P value of <0·05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

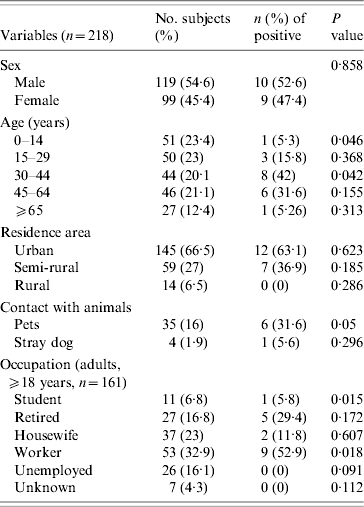

Of the 218 subjects, 119 were male and 99 female. The mean age was 34·36 years (0–91 years). Subjects were reported from 11 towns, and 145 (66·51%), 59 (27·2%), and 14 (6·5%) subjects lived in urban, semi-rural, and rural areas, respectively; 35 (16%) reported contact with pets, and four (1·9%) with stray dogs. In the group of 161 adults (⩾18 years), there were 11 (6·8%) students, 27 (16·8%) retired, 37 (23%) housewives, 53 (32·9%) workers, and 26 (16·1%) unemployed. For seven people the occupation was unknown.

Considering titres of ⩾1:64 as positive, the seroprevalence of B. henselae in humans was 8·7%, considering samples with antibodies against B. henselae only or with B. henselae titres twofold higher to B. quintana titres. No sample had antibodies against B. quintana only. The relationship between the B. henselae antibody prevalence and the surveyed items is shown in Table.

Table.

Demographic information from subjects tested for antibodies to B. henselae

Nineteen samples had antibodies against B. henselae. Ten of them had an IgG titre of 1:64, four a titre of 1:128, four a titre of 1:256 and one a titre of 1:512.

No difference in seroposivity was observed between males and females. The B. henselae seroprevalence was 8·3% in urban areas, 11·9% in semi-rural areas and 0% in rural areas. The mean age (±s.d.) of seropositive subjects was 42·83±17·04 years, whereas the mean age of seronegative subjects was 33·59±23·56 years (P=0·053). Seropositivity was significantly more prevalent in subjects aged 30–44 years (P=0·042). On the other hand, subjects aged 0–14 years showed a lower seropositive rate (P=0·046). Of seropositive patients, six (31·6%) had contact with pets (P=0·05) and one (5·6%) with stray dogs (non-significant). Concerning occupation, students presented lower seroprevalence (5·8%, P=0·015) and workers had a higher seropositive rate (52·9%, P=0·018).

DISCUSSION

B. henselae, now regarded as the primary, and perhaps sole, causative agent of CSD, is also a cause of BA and hepatic peliosis, and has been associated with endocarditis, fever, and bacteraemia in adults and children [15, 16]. Isolation of Bartonella is typically time-consuming, often requiring 2–6 weeks or longer incubation for primary isolation. The resulting isolation must then be identified by PCR. In general, isolation or detection of B. henselae from blood is not successful for CDS patients who have no evidence of systemic disease. Conversely, isolation of Bartonella spp. from blood of immunocompromised patients, or patients with evidence of systematic disease is usually possible. PCR offers a rapid and specific means to detect the organism directly from clinical samples and is more sensitive than isolation [17]. In humans, serological testing is the reference test for diagnosis of CDS and other infections by Bartonella [18]. An IgG anti-B. henselae antibody titre of ⩾1:64 is considered as positive for infection.

Nineteen people (8·71%) had antibodies against B. henselae. This seroprevalence is slightly lower than those reported by other investigators: 30% by Sander et al. [18] in Germany, 19·8% by Alexiou-Daniel et al. [19] in Greece, and 24·7% by Garcia-Garcia et al. [20] in Sevilla, Spain. However, similar or lower seroprevalence have been found in healthy populations from Sweden (3·2%) or La Rioja, Spain (5·88%) [21, 22]. We are able to assume that this seropositivity may indicate a past infection with Bartonella spp. However, we could not exclude unspecified serological cross-reactivity with other heterologous antigens. It is well known that Bartonella can cross-react with other genera, such as Coxiella burnetti or Chlamydia [23, 24]. Therefore, we compared these data with those obtained in a previous study (M. Vila et al., unpublished data). All 218 individuals included in this study were examinated by an IFA test for Chlamydia [Chlamydophila pneumoniae IFA IgG (Vircell, S.L., Santa Fé, Granada, Spain), cut-off 1/64]. Eight (3·66%) serum samples had antibodies against B. henselae exclusively; three serum samples reacted against C. pneumoniae and Bartonella at the same titre levels; six sera showed higher titres against B. henselae (1/128 vs. 1/32, 1/512 vs. 1/32 and 1/256 vs. 1/32); and in two other samples titres against Chlamydia were higher (1/256 vs. 1/64 and 1/128 vs. 1/64). These last two sera should not be considered positive for B. henselae. These results indicate B. henselae may be present in Catalonia and its seroprevalence might range from 6·42% to 7·9%.

The only statistically significant association observed was that between B. henselae seropositivity and age. B. henselae seropositivity was significantly more prevalent in subjects aged 30–44 years. This observation agrees with a study carried out in Greece, which also showed higher B. henselae seropositive rates in children aged <14 years (non-significant). Moreover, those children had greater titres [19]. Taking into account that the cat is the main Bartonella reservoir, most seropositive subjects had contact with pets. Highest titres in children could be due to greater contact with pets. Seropositives rates differ from one study to another due to the different epidemiological and climatic environments. Therefore, we carried out a seroprevalence study of B. henselae in cats from the same region and over the same period of time [25]. Seroprevalence of B. henselae in cats was 26% and there were 7% of cats with bacteraemia. If cats aged <1 year were considered, incidence of bacteraemia rises to 12·1%.

As shown in Sander et al. [18], most titres were not high. Thus, it seems that subjects did not have recent infection. In our study 1·37% of the healthy population examined had IgG antibodies to B. henselae at a titre 1:128, and 0·91% had IgG antibodies at a titre of 1:256 and 0·45% had IgG antibodies at a titre of 1:512.

Because bartonelloses are a newly recognized class of infection in Spain, it is important to identify certain potential risk factors. It is reasonable to assume that as reliable, validated, and safe methods for serological diagnosis of Bartonella infections become a routine procedure in many clinical laboratories, the spectrum of Bartonella-associated diseases will continue to expand. The present study therefore provides an epidemiological and serological framework for future Bartonella studies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by a FIS-0/0598 grant from ‘Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias’ (Health Research Fund), Madrid, Spain, and supported in part by Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo, Instituto de Salud Carlos III – FEDER, Spanish Network for the Research in Infectious Diseases (REIPI RD06/0008). We thank Jordi Real and Eva Penelo for their advice on biostatistics.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stoler MH et al. An atypical subcutaneous infection associated with acquired immune deficiency syndrome. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1983;80:714–718. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/80.5.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson BE, Neuman MA. Bartonella spp. as emerging human pathogens. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 1997;10:203–219. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.2.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chomel BB, Boulouis HJ, Breitschwerdt EB. Cat scrastch disease and other zonotic Bartonella infections. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2004;224:1270–1279. doi: 10.2460/javma.2004.224.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Comer JA, Paddock CD, Childs JE. Urban zoonoses caused by Bartonella, Coxiella, Ehrlichia, and Rickettsia species. Vector Borne Zoonotic Diseases. 2001;1:91–118. doi: 10.1089/153036601316977714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson G et al. Detection and identification of Bartonella species pathogenic for humans by PCR amplification tarfgeting the riboflavin synthase gene (ribC) Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2003;41:1069–1072. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.3.1069-1072.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kosoy M et al. Bartonella strains from ground squirrels are identical to Bartonella washoensis isolated from a human patient. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2003;41:645–650. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.2.645-650.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kerkhoff FT et al. Demostration of Bartonella grahamii DNA in ocular fluids of a patient with neuroretinitis. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1999;37:4034–4038. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.12.4034-4038.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mansueto P et al. Bartonellosis. Recenti Progressi in Medicina. 2003;94:177–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Avidor B et al. Bartonella koehlerae, a new cat-associated agent of culture negative human endocarditis. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2004;42:3462–3468. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.8.3462-3468.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raoult D et al. First isolation of Bartonella alsatica from a valve of a patient with endocarditis. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2006;44:278–279. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.1.278-279.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chomel BB. Cat-scratch disease and bacillary angiomatosis. Revue Scientifique et Technique Office International des Epizooties. 1999;15:1061–1073. doi: 10.20506/rst.15.3.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brouqui P et al. Chronic Bartonella quintana bacteremia in homeless patients. New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;340:184–189. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901213400303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raoult D et al. Diagnosis of 22 new cases of Bartonella endocarditis. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1996;125:646–652. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-8-199610150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zbinden R et al. Evaluation of commercial slides for detection of immunoglobulin G against Bartonella henselae by indirect immunofluorescence. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 1997;16:648–652. doi: 10.1007/BF01708554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piemont Y, Bermon D. Infections caused by Bartonella spp. Annales de Biologie Clinique (Paris) 2001;59:593–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chomel BB. Cat-scratch disease. Revue Scientifique et Technique Office International des Epizooties. 2000;19:136–150. doi: 10.20506/rst.19.1.1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fournier PE, Mainardi JL, Raoult D. Value of microimmunofluoresecence for diagnosis and follow-up of Bartonella endocarditis. Clinical and Diagnostic Laboratory Immunology. 2002;9:795–801. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.9.4.795-801.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sander A et al. Seroprevalence of antibodies to Bartonella henselae in patients with scratch disease in healthy controls: evaluation and comparison of two commercial serological test. Clinical and Diagnostic Laboratory Immunology. 1998;5:486–490. doi: 10.1128/cdli.5.4.486-490.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alexiou-Daniel AT et al. Occurrence of Bartonella henselae and Bartonella quintana in healthy Greek population. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2000;68:554–556. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2003.68.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia-Garcia JA et al. Prevalence of serum antibodies against Bartonella ssp. in a health population from the south area of the Seville province [in Spanish] Revista Clinica Espanola. 2005;11:541–544. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2565(05)72634-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGill S et al. Bartonella spp. seroprevalence in healthy Swedish blood donors. Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2005;37:723–730. doi: 10.1080/00365540510012152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blanco JR et al. Seroepidemiology of Bartonella henselae infection in a risk group [in Spanish] Revista Clinica Espanola. 1998;12:805–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.La Scola B, Raoult D. Serological cross-reactions between Bartonella quintana, Bartonella henselae and Coxiella burnetii. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1996;34:2270–2274. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.9.2270-2274.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maurin M, Etienne J, Raoult D. Serological cross-reactions between Bartonella and Chamidydia species: implications for diagnosis. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1997;35:2283–2287. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.9.2283-2287.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pons I et al. Prevalence of Bartonella henselae in cats in Catalonia, Spain. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2005;72:453–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]