SUMMARY

The distribution of Burkholderia pseudomallei was determined in soil collected from a rural district in Papua New Guinea (PNG) where melioidosis had recently been described, predominately affecting children. In 274 samples, 2·6% tested culture-positive for B. pseudomallei. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis using SpeI digests and rapid polymorphic DNA PCR with five primers demonstrated a single clone amongst clinical isolates and isolates cultured from the environment that was commonly used by children from whom the clinical isolates were derived. We concluded that individuals in this region most probably acquired the organism through close contact with the environment at these sites. Burkholderia thailandensis, a closely related Burkholderia sp. was isolated from 5·5% of samples tested, an observation similar to that of melioidosis-endemic areas in Thailand. This is the first report of an environmental reservoir for melioidosis in PNG and confirms the Balimo district in PNG as melioidosis endemic.

INTRODUCTION

Melioidosis is caused by the saprophytic Gram-negative bacterium Burkholderia pseudomallei. Although the organism's ecology is not well understood, B. pseudomallei seems to prefer moist clay soils and associated fresh water [1]. It is clear that individuals with a close association with the environment in regions where the organism is endemic are at risk of acquiring the disease [2]. When a reservoir of infection and mode of transmission is elucidated, control measures may be investigated. A melioidosis-endemic region in rural Papua New Guinea (PNG) has recently been reported [3]. A key feature of the disease in this remote and resource-poor community is childhood predilection. The objective of this study was to demonstrate a reservoir of infection and, through determining the molecular epidemiology of isolates from clinical and environmental sources, propose a mode of transmission for melioidosis in this region. This should assist with the development of more efficacious melioidosis prevention strategies.

METHODS

Ethical approval was provided by the PNG Medical Research Advisory Council. At all times permission from local village communities was sought before any aspect of the study commenced.

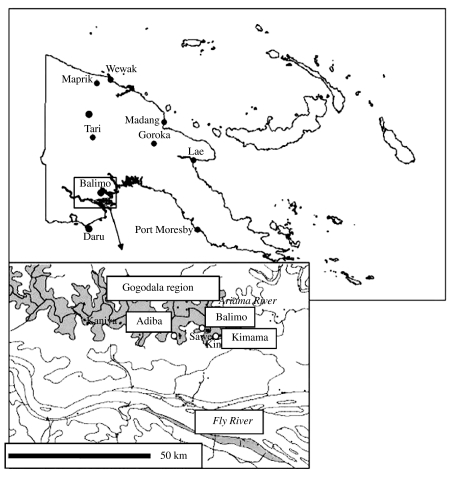

Three village communities, Balimo, Kimama and Adiba, within the Gogodala language group of the Western province PNG where clinical melioidosis has recently been described were selected for the study (Fig. 1) [3]. Sites where individuals, particularly children, had contact with the environment were opportunistically sampled. Sites included soil from garden places (GP); soil under or near houses (NH); soil from points of land near the lagoon, where children wash (PtC); soil from mainland regions of the village (N-PtC) and soil from walls of water wells or soil adjacent to well (Wells). Samples from the same region within villages were generally taken at 5 m intervals. Samples were collected during the last month of the wet season. A hole about 50 cm deep was dug with a spade which was cleaned of excess soil and disinfected with 70% ethanol between each application. Samples of soil were generally taken at a depth of 30 cm using disposable wooden applicator sticks. About 80 g of soil was collected from the hole, placed into 80 ml sterile, polypropylene containers and transported to James Cook University, Townsville, Australia for processing.

Fig. 1.

The villages of the Gogodala region are located predominately throughout the Aramia river floodplain which is about 30 km from the Fly River. The Aramia River feeds lagoon systems which seasonally flood. Villages are often established on land which is surrounded by these lagoons. Balimo village is located across a lagoon system 6 km to the northwest of Kimama. Adiba village is located on a separate lagoon system 11 km upriver from Balimo.

Ashdown's B. pseudomallei environmental selective broth (ASHSB) [4] with the addition of 50 mg/l colistin was used in the processing. Sample preparation and incubation conditions were optimized as follows. Forty grams of soil were placed in 40 ml sterile distilled water. The mixture was subjected to agitation in an orbital shaker at 30°C for 24 h. Next the soil was allowed to settle and 10 ml of the supernatant was added to 10 ml of 2× concentrated ASHSB and further incubated at 30°C for 5 days. Then the broth was subcultured onto Ashdown agar (ASH) with 8 mg/l gentamicin. Typical colonies were selected for further investigation.

Both phenotypic and genotypic methods of identification were used. Isolates were presumptively identified as B. pseudomallei based on typical colonial appearance, positive oxidase reaction and gentamicin resistance. The identity was confirmed using API 20NE (bioMérieux, Baulkham Hills, NSW) or Microbact 24E (MedVet, Adelaide, SA) [5]. Isolates were further subjected to PCR using published primers and protocols, which were able to discriminate between B. pseudomallei and B. thailandensis [6, 7]. Isolates suspected of being B. thailandensis were assessed for arabinose assimilation and only those testing positive were identified as B. thailandensis [8]. Isolates that met these genotypic and phenotypic criteria were confirmed as either B. pseudomallei or B. thailandensis.

All isolates confirmed as either B. pseudomallei or B. thailandensis in this study along with 10 clinical B. pseudomallei isolates previously cultured from individuals from the Balimo region, were subjected to pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) using SpeI [9]. The B. pseudomallei isolates were also subjected to rapid amplified of polymorphic DNA (RAPD) PCR using five primers (RAPD 10mer; Qiagen, Doncaster, VIC) based on the methods previously published for use with B. pseudomallei [10, 11]. Band patterns were analysed based on the methods of Tenover [12].

Fisher's exact test was used to determine differences among and between villages and regions within villages for prevalence of B. pseudomallei and B. thailandensis in soil and Spearman's correlation coefficients were used to determine relationships between the prevalence of the two Burkholderia species.

RESULTS

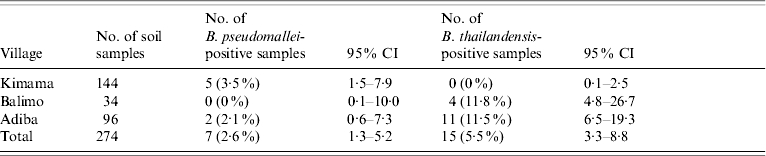

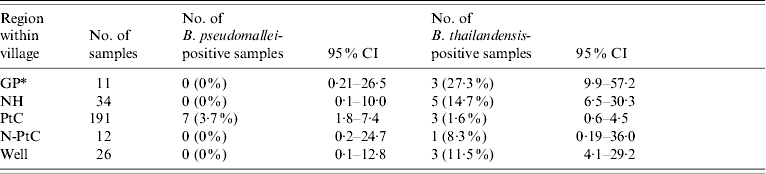

The prevalence of B. pseudomallei and B. thailandensis from the 274 soil samples collected from the three villages are shown in Table 1. Although no samples collected from Balimo were culture-positive for B. pseudomallei, the prevalence did not vary significantly among villages (P=0·90, Fisher's exact test). In contrast, the prevalence of B. thailandensis among villages varied significantly (P<0·001, Fisher's exact test). The distribution of B. pseudomallei- and B. thailandensis-positive samples in regions within villages is shown in Table 2. Only the samples taken from the regions classified as points of land, where children play (PtC) yielded B. pseudomallei although the prevalence did not vary significantly among regions (P=0·8, Fisher's exact test). However, the distribution of B. thailandensis-positive samples varied significantly among regions (P<0·001, Fisher's exact test). It is interesting to note that in both regions within and among villages there appear to be inverse relationships between the rank of B. pseudomallei and B. thailandensis prevalence, although these did not achieve significance at the 5% level (P=0·2 and 0·3, respectively, Spearman correlation).

Table 1.

Prevalence of B. pseudomallei and B. thailandensis from soil samples taken from Kimama, Balimo and Adiba

Table 2.

Distribution of B. pseudomallei- and B. thailandensis-positive soil samples per region within village

See Methods section for explanation of abbreviations.

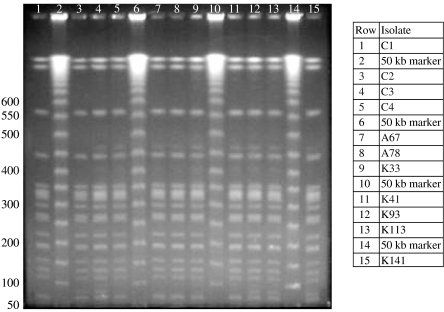

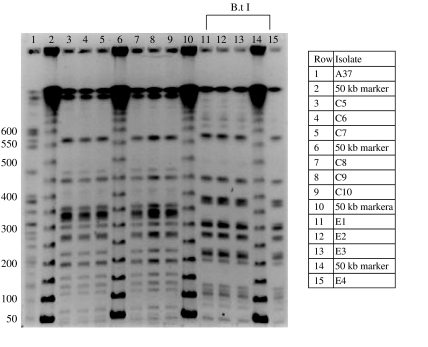

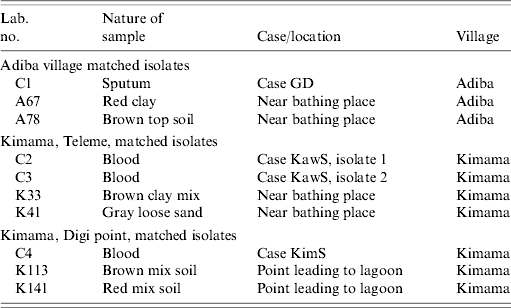

A total of 17 B. pseudomallei and 15 B. thailandensis isolates were subjected to molecular typing. These included the seven environmental B. pseudomallei isolates collected during this study and 10 clinical isolates previously cultured from individuals with melioidosis from the Balimo region [3]. All isolates were subjected to SpeI restriction digest PFGE. All 17 confirmed B. pseudomallei isolates, including the 10 isolates that represent three clinical/environmental matches (Table 3), shared the same PFGE macro- restriction pattern regardless of location and source of isolate (Figs 2 and 3). This genotype consists of 17 bands ranging from about 50–1000 kb. The 10 epidemiologically matched isolates were further analysed with RAPD PCR and all five primers showed identical banding patterns (data not shown).

Table 3.

B. pseudomallei isolates epidemiologically matched in terms of locality

Nature of sample refers to either an isolate of clinical or environmental origin. Case/location refers to the individual diagnosed with melioidosis from whom the organism was isolated and recently reported [3] and the location of the environmental sample. Teleme and Digi point are localities within Kimama village, they are both adjacent to the lagoon system and about 300 m distant from each other.

Fig. 2.

SpeI digest PFGE patterns of three epidemiologically associated B. pseudomallei isolate groups.

Fig. 3.

SpeI digest PFGE patterns demonstrating all clinically derived B. pseudomallei (C prefix) with the same genotype as epidemiologically unrelated clinical and environmental isolates shown in Figure 2. Included in rows 11–15 are PNG B. thailandensis genotype 1. Isolate A37 (row 1) is an uncharacterized environmental organism demonstrating considerable divergence from the other Burkholderia.

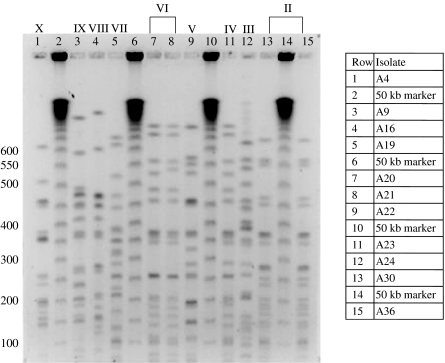

In contrast, PFGE analysis of the 15 isolates that shared B. thailandensis characteristics demonstrated 10 genotypes (Figs 3 and 4). The four isolates from Balimo (E1–E4) shared the same type (I), two groups of two from Adiba shared two separate types (II and VI), but all others were separate, with varying degrees of similarity.

Fig. 4.

SpeI digest patterns of PNG B. thailandensis genotypes II–X.

DISCUSSION

We report for the first time the isolation of B. pseudomallei from the environment in PNG, an observation that substantiates the Balimo region of the Western province as a newly described melioidosis-endemic community. The overall prevalence of B. pseudomallei cultured from soil samples (2·6%, 95% CI 1·3–5·2) is at the lower end of those reported from Thailand (4·4–20·4%) [13] but higher than those rates reported from North Queensland (1·7%) [14].

The general clonality demonstrated within this group of B. pseudomallei isolates from this region limits the ability to clearly define the epidemiology of infection. However, the data gathered so far supports the general hypothesis that the organism responsible for melioidosis in this region resides in soil at points of land leading into the lagoon where children play. In this community children are more likely than adults to wash (bathe) in the muddy waters of the lagoon adjacent to these regions. This activity is mostly robust play, and is likely to enable transmission of water-borne organisms. The mode of acquisition could be through inhalation, aspiration or per-nasal transmission, or by subcutaneous inoculation through pre-existing skin lesions. The epidemiology may be similar to that recently described in Brazil where childhood predilection associated with specific environmental exposure with no apparent comorbidity is also a feature. Together they may represent a new epidemiological paradigm, one which health-care workers in similar rural subsistence communities should be made aware of [15, 16]. Further sampling and testing is required to support these observations.

It has been noted elsewhere that the prevalence of B. pseudomallei has an inverse relationship with the prevalence of B. thailandensis and that this is related to a lower clinical incidence of melioidosis in endemic regions [17]. The relatively small number of samples employed in this study applied limitations to the statistical analysis of the prevalence data. However, it is noteworthy in this study that the village with highest B. pseudomallei prevalence (Kimama) shared the lowest prevalence of B. thailandensis and the inverse was observed with the village with the lowest B. pseudomallei prevalence (Balimo) (Table 1). These observations need to be further tested with a more robust sampling strategy.

The B. pseudomallei isolates that represent the single PFGE and RAPD genotype share the multi-locus sequence type (MLST) ST267 (Nilsson, unpublished observations), the same as a clone previously typed from the Balimo region of PNG. This general lack of genetic diversity of B. pseudomallei from this region is of interest, and may reflect attributes of ecology and survival of this organism in this region. A phylogenetic study of these isolates with those from geographically related regions where melioidosis has been previously reported, such as Port Moresby, Torres Strait and mainland Queensland [18–20] may yield information on the evolution and movement of B. pseudomallei within this region [21].

The differences in genetic diversity between B. pseudomallei and B. thailandensis may highlight the importance of selection pressure from the human susceptible host and/or single-celled eukaryotes or plants in this region [22] in selecting out and maintaining a single genotype of Burkholderia sp. from the environment with the fitness to adapt to an intracellular lifestyle. This virulent genotype may be recycled into the environment and be maintained through continued exposure and release, as has been speculated previously [17, 23, 24]. As virulence, and therefore an ability to adopt an intracellular habitat, appears not to be a feature of the PNG B. thailandensis strains [25], clonal selection of this species in this way is unlikely. Further characterization of the PNG B. thailandensis isolates within this collection may demonstrate divergence typical of multiple species.

Local health-care authorities should expect melioidosis cases to appear after the beginning of the wet season, when the water fills the lagoon and children are more likely to wash and play at these sites. Basic primary health care which protects skin lesions such as cuts and sores from the environment may be useful in minimizing exposure to B. pseudomallei. Further recognition and quarantine of infected areas would provide a simple cost-effective strategy which should reduce morbidity and mortality from this infection in a region with limited health resources.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge the staff of Balimo Health Centre and the local Gogodala community for their support of the study. The study was funded by BHP Community Trust.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

None.

REFERENCES

- 1. .Dance DAB. Ecology of Burkholderia pseudomallei and the interactions between environmental Burkholderia spp. and human-animal hosts. Acta Tropica. 2000;74:159–168. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(99)00066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. .Cheng AC, Currie BJ. Melioidosis: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. Clinical Microbiology Review. 2005;18:383–416. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.2.383-416.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. .Warner JM et al. Melioidosis in a rural community of the Western province, Papua New Guinea. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2007;101:809–813. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2007.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. .Ashdown LR, Clark SG. Evaluation of culture techniques for isolation of Pseudomonas pseudomalli from soil. Applied Environmental Microbiology. 1992;58:4011–4015. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.12.4011-4015.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. .Dance DA et al. Identification of Pseudomonas pseudomallei in clinical practice: use of simple screening tests and API 20NE. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1989;42:645–648. doi: 10.1136/jcp.42.6.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. .Dharakul T et al. Phylogenetic analysis of Ara+ and Ara− Burkholderia pseudomallei isolates and development of a multiplex PCR procedure for rapid discrimination between the two biotypes. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1999;37:1906–1912. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1906-1912.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. .Winstanley C, Hart CA. Presence of type III secretion genes in Burkholderia pseudomallei correlates with Ara(−) phenotypes. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2000;38:883–885. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.2.883-885.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. .Brett PJ, DeShazer D, Woods DE. Burkholderia thailandensis sp. nov., a Burkholderia pseudomallei-like species. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology. 1998;48:317–320. doi: 10.1099/00207713-48-1-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. .Gal D et al. Contamination of hand wash detergent linked to occupationally acquired melioidosis. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2004;71:360–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. .Norton R et al. Characterisation and molecular typing of Burkholderia pseudomallei: are disease presentations of melioidosis clonally related? FEMS Immunology and Medical Microbiology. 1998;20:37–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1998.tb01109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. .Haase A et al. RAPD analysis of isolates of Burkholderia pseudomallei from patients with recurrent melioidosis. Epidemiology and Infection. 1995;115:115–121. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800058179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. .Tenover FC et al. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1995;33:2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. .Vuddhakul V et al. Epidemiology of Burkholderia pseudomallei in Thailand. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1999;60:458–461. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.60.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. .Thomas AD. The isolation of Pseudomonas pseudomallei from soil in North Queensland. Australian Veterinary Journal. 1977;53:408. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1977.tb07973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. .Miralles IS et al. Burkholderia pseudomallei: a case report of a human infection in Ceara, Brazil. Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de São Paulo. 2004;46:51–54. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652004000100011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. .Rolim DB et al. Melioidosis, northeastern Brazil. Emerging Infectious Disease. 2005;11:1458–1460. doi: 10.3201/eid1109.050493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. .Trakulsomboon S et al. Epidemiology of arabinose assimilation in Burkholderia pseudomallei isolated from patients and soil in Thailand. Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health. 1999;30:756–759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. .Currie B. Melioidosis in Papua New Guinea: is it less common than in tropical Australia? Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1993;87:417. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(93)90018-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. .Faa AG, Holt PJ. Melioidosis in the Torres Strait islands of far North Queensland. Communicable Disease Intelligence. 2002;26:279–283. doi: 10.33321/cdi.2002.26.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. .Rimmington RA. Melioidosis in North Queensland. Medical Journal of Australia. 1962;1:50. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1962.tb76106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. .Godoy D et al. Multilocus sequence typing and evolutionary relationships among the causative agents of melioidosis and glanders, Burkholderia pseudomallei and Burkholderia mallei. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2003;41:2068–2079. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.5.2068-2079.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. .Inglis TJJ, Mee BJ, Chang BJ. The environmental microbiology of melioidosis. Reviews in Medical Microbiology. 2001;12:13–20. [Google Scholar]

- 23. .Dance DAB. Pseudomonas pseudomallei: danger in the paddy fields. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1991;85:1–3. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(91)90134-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. .Ketterer PJ, Donald B, Rogers RJ. Bovine melioidosis in South-Eastern Queensland. Australian Veterinary Journal. 1975;51:395–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1975.tb15607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. .Ulett GC et al. Burkholderia pseudomallei virulence: definition, stability and association with clonality. Microbes and Infection. 2001;3:621–631. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(01)01417-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]