Abstract

Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) is activated by a majority of cytokine family receptors including receptors for GH, leptin, and erythropoietin. To identify novel JAK2-regulatory and/or -binding sites, we set out to identify autophosphorylation sites in the kinase domain of JAK2. Two-dimensional phosphopeptide mapping of in vitro autophosphorylated JAK2 identified tyrosines 868, 966, and 972 as sites of autophosphorylation. Phosphorylated tyrosines 868 and 972 were also identified by mass spectrometry analysis of JAK2 activated by an erythropoietin-bound chimeric erythropoietin receptor/leptin receptor. Phosphospecific antibodies suggest that the phosphorylation of all three tyrosines increases in response to GH. Compared with wild-type JAK2, which is constitutively active when overexpressed, JAK2 lacking tyrosine 868, 966, or 972 has substantially reduced activity. Coexpression with GH receptor and protein tyrosine phosphatase1B allowed us to investigate GH-dependent activation of these mutated JAK2s in human embryonic kidney 293T cells. All three mutated JAK2s are activated by GH, although to a lesser extent than wild-type JAK2. The three mutated JAK2s also mediate GH activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3), signal transducer and activator of transcription 5b (Stat5b) and ERK1, but at reduced levels. Coexpression with Src-homology 2B1β (SH2B1β), like coexpression with GH-bound GH receptor, partially restores the activity of all three JAK2 mutants. Based on these results and the crystal structure of the JAK2 kinase domain, we hypothesize that small changes in the conformation of the regions of JAK2 surrounding tyrosines 868, 966, and 972 due to e.g. phosphorylation, binding to a ligand-bound cytokine receptor, and/or binding to Src-homology 2B1, may be essential for JAK2 to assume a maximally active conformation.

Tyrosines 868, 966, and 972 in JAK2 autophosphorylate. JAK2 lacking these tyrosines is essentially inactive, but can be partially activated by SH2B1beta or GH-GHR.

Activation of Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) is an initiating step in signaling for many members of the cytokine receptor superfamily including the receptors for GH, prolactin, leptin, erythropoietin (Epo), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, thrombopoietin, and multiple ILs. In total, JAK2 can be activated by more than two thirds of the cytokine receptor family members (1,2). JAK2 also lies downstream of the G protein-coupled receptors for angiotensin II (3), α-thrombin, nicotine, serotonin, and LH (reviewed in Ref. 4). Because so many ligands are capable of activating JAK2, we were interested in gaining additional insight into the molecular mechanisms by which JAK2 becomes activated and is regulated, as well as the signaling pathways that are initiated as a direct result of JAK2 autophosphorylation.

JAK2 (murine) contains 49 tyrosines. When activated, JAK2 is phosphorylated on more than 20 of those tyrosines, based on the number of peptides visualized in two-dimensional (2D) phosphopeptide maps (5,6,7,8). In previous studies, we identified Tyr 221, 317, 570, 637, 813, and 1007 as sites of autophosphorylation (6,9,10,11) and used a variety of techniques to study the function of their phosphorylation in GH and leptin signaling. Thinking that the sites of autophosphorylation in JAK2 most likely to regulate its kinase activity would lie near its ATP- and substrate-binding sites, we chose in this study to concentrate on the tyrosines in the kinase domain (JH1 domain: residues 835-1132) of JAK2. Analysis of the crystal structure of this domain (12) indicates that Tyr 868, 913, 918, 931, 934, 966, 972, 1007, 1008, 1050, and 1099 are on the surface of JAK2. In contrast, Tyr 956, 1021, and 1045 are predicted to be buried, and Tyr 940 to be partially buried, in the interior of the kinase domain of JAK2. Tyr 1007 corresponds to the activating tyrosine present in all tyrosine kinases; it has been identified as a site of autophosphorylation in both ectopically expressed and endogenous JAK2 by multiple means and multiple groups (5,6,9,12,13,14). Tyr 1008 has also been implicated as an autophosphorylation site by x-ray crystallography (12) and comigration of JAK2-derived and synthetic peptides in 2D phosphopeptide maps (5). Subsequent to the initiation of our studies, Tyr 918, 931, 934, 940, 956, 966, and 972 have also been implicated as sites of phosphorylation by either mass spectrometry (MS) (Tyr 931, 956, and 966) (13) or comigration/coelution of peptides derived from JAK2 from Sf9 cells with synthetic peptides either in 2D phosphopeptide maps and/or by HPLC (Tyr 918, 931, 934, 940, 966, and 972) (7).

In this report, we use three different approaches (2D phosphopeptide mapping combined with site-directed mutagenesis, MS, and phosphospecific antibodies) to identify Tyr 868, 966, and 972 as autophosphorylation sites in JAK2. We provide evidence that GH elicits a rapid, transient increase in the phosphorylation of these three tyrosines in endogenous JAK2 in 3T3-F442A cells. When expressed ectopically in human embryonic kidney 293T (293T) cells, at levels at which overexpressed wild-type JAK2 is constitutively active, JAK2 lacking Tyr 868, Tyr 966, or Tyr 972 showed greatly reduced kinase activity, assessed by phosphorylation of Tyr 1007/1008, general tyrosyl phosphorylation of JAK2, and an in vitro kinase assay. When coexpressed with GH receptor, these Y→F mutants of JAK2 were capable of being activated by GH as measured by these same assays. They were also capable of mediating GH activation of Stat3, Stat5b, and ERK1, although to a lesser extent than wild-type JAK2. Coexpression with Src-homology 2 (SH2)B1β, like coexpression with GH-bound GH receptor, also partially restored their kinase activity. Based on these results and the crystal structure of the JAK2 kinase domain, we hypothesize that small changes in the conformation of the regions of JAK2 surrounding Tyr 868, 966, and 972 due, for example, to phosphorylation, binding to a ligand-bound cytokine receptor, and/or binding to SH2B1, may be essential for JAK2 to assume a maximally active conformation.

Results

2D phosphopeptide mapping demonstrates that tyrosines 868, 966, and 972 in the kinase domain of JAK2 autophosphorylate

To gain insight into how cytokine-dependent tyrosyl phosphorylation of JAK2 regulates JAK2 activity and determine whether JAK2 autophosphorylation initiates at least some of the effects of cytokines on cell function, we set out to identify tyrosines in the kinase domain of JAK2 that are autophosphorylated. Constructs were created encoding JAK2 with each of the 15 tyrosines in the kinase domain of JAK2 individually mutated to phenylalanine. For these experiments, 293T cells were used because they contain almost nondetectable levels of endogenous JAK2. Wild-type and mutant JAK2s were ectopically expressed, substantially purified by immunoprecipitating with αJAK2, and subjected to an in vitro kinase assay in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. The 32P-labeled JAK2 was subjected to 2D phosphopeptide mapping (thin-layer electrophoresis followed by thin-layer chromatography) as described in Materials and Methods. Previous studies revealed that in this in vitro kinase assay, 32P is incorporated almost exclusively (>99%) into tyrosines in JAK2 (15). Thus, 32P-labeled peptides were presumed to contain sites of JAK2 autophosphorylation. Several of the mutated JAK2s were poorly autophosphorylated, and high-quality 2D phosphopeptide maps could not be obtained. To increase the incorporation of 32P into JAK2, a truncated SH2B1β, myc-tagged SH2B1β (504–670), was coexpressed with the various JAK2 constructs. SH2B1β (504–670), like full-length SH2B1β, stimulates the activity of overexpressed JAK2 (10,16). As shown previously (6), wild-type JAK2 (murine), which contains a total of 49 tyrosines, yielded more than 20 32P-labeled peptides (Fig. 1). The addition of SH2B1β (504–670) did not alter the number or location of spots in the 2D phosphopeptide maps of JAK2 (data not shown). The 32P-labeled peptides were missing or shifted in the maps of JAK2 Y868F, JAK2 Y966F, JAK2 Y972F, and JAK2 Y1008F. When Tyr 868 was mutated to phenylalanine, spot 1 disappeared (compare panels A and B of Fig. 1). When Tyr 966 was mutated to phenylalanine, one of two spots that migrate as a doublet disappeared (spot 2) (compare panels K and L of Fig. 1). The doublet was often poorly resolved. Sometimes it was visible as two spots (see Fig. 1, L–O), sometimes as an elliptical spot (see Fig. 1, F–J). Mutation of Tyr 972 to phenylalanine led to the elimination of spot 3 (compare panels P and Q of Fig. 1). When Tyr 1008 was mutated to phenylalanine, spot 5 disappeared and two new spots appeared (spots 6 and 7) (compare panels R and S of Fig. 1). A shift in migration of a 32P-labeled spot suggests that the corresponding peptide contains two phosphorylated residues. The predicted Tyr 1008-containing tryptic peptides also contain Tyr 1007, a well-documented site of JAK2 autophosphorylation (5,6). The detection of the two peptides containing phosphotyrosine (pY)1007F1008 is likely due to inefficient trypsin cleavage that often occurs at lysines that are two residues N-terminal to a pY (17). Based on the theoretical predicted migrations of the peptides containing Tyr 1007 and Tyr 1008, spot 5 in the map of wild-type JAK2 (Fig. 1R) is thought to correspond to the 32P-labeled doubly phosphorylated peptide VLPQDKEpY1007pY1008K. Spot 7 in the map of JAK2 Y1008F (Fig. 1S) is thought to correspond to the 32P-labeled singly phosphorylated peptide VLPQDKEpY1007F1008K, and spot 6 is thought to correspond to the singly phosphorylated peptide EpY1007F1008K. No spots were consistently missing from the 2D phosphopeptide maps for the remaining JAK2 Y→F kinase domain mutants (Y913F, Y918F, Y931F, Y934F, Y940F, Y956F, Y1021F, Y1045F, Y1050F, and Y1099F) (Fig. 1, panels D, E, G–J, and L–O, respectively). The above results suggest that in addition to the activating Tyr 1007, there are at least four tyrosines in the kinase domain of JAK2 that autophosphorylate: Tyr 868, 966, 972, and 1008. It is possible that additional tyrosines in the kinase domain of JAK2 could be phosphorylated because the variable presence of the line of spots above the origin in our 2D phosphopeptide maps makes assignment of these spots difficult. Peptides containing other phosphorylated tyrosines in the kinase domain of JAK2 could migrate in this region or comigrate with peptides in other regions and escape detection.

Figure 1.

JAK2 is autophosphorylated on tyrosines 868, 966, 972, and 1008. 293T cells transiently expressing SH2B1β (504-670) (5 μg cDNA) and JAK2 or the indicated JAK2 Y→F mutant (2 μg cDNA) were lysed, and JAK2 was immunoprecipitated using αJAK2. Immobilized JAK2 was incubated with [γ-32P]ATP for 30 min. The 32P-labeled JAK2 was subjected to 2D phosphopeptide mapping. Insets are enlargements of the boxed regions containing spots of interest. Numbered solid arrows in maps A, L, and P indicate the position of spots (1, 2, and 3) that are missing (open arrows) in maps B, K, and Q of JAK2 Y868F, JAK2 Y966F, or JAK2 Y972F, respectively. The incorporation of 32P into JAK2 Y868F (map B) was minimal when compared with the other JAK2 constructs (data not shown). Therefore, in map B, background spots (determined by their presence in control cells not expressing ectopic JAK2) are more evident than in the corresponding map A of wild-type (WT) JAK2. The most prominent spot in the inset of map B is an example of such a background spot. The solid arrow in map R indicates the position of spot 5 that corresponds to the peptide containing phosphorylated Tyr 1008 (theoretically VLPQDKEpY1007pY1008K). In map S of JAK2 Y1008F, this peptide shifts to spot 7 (theoretically VLPQDKEpY1007F1008K). An additional cleavage product (theoretically EpY1007F1008K) is also present (spot 6). Boxes surround the maps that were performed in a single individual experiment. To determine with confidence that mutation of a tyrosine to phenylalanine leads to the disappearance of a specific spot, only JAK2 and JAK2 mutants from tryptic digests that were run simultaneously were compared. Between two and five maps were obtained for each of the JAK2 Y→F mutants.

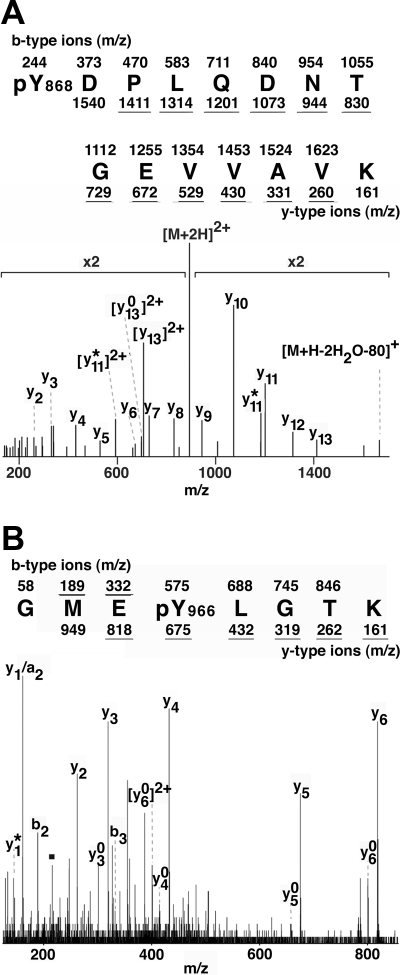

Phosphorylation of tyrosines 868 and 966 in JAK2 is detected by MS

We also used MS to identify tyrosines in JAK2 that undergo phosphorylation. To stimulate the autophosphorylation of JAK2, we coexpressed JAK2 with an Epo receptor/leptin receptor chimera (ELR) that places the intracellular domain of the leptin receptor under the control of Epo (9) and yields Epo-dependent activation of JAK2. We employed this ELR chimera in place of the native long-form leptin receptor (LRb) because the extracellular domain of the Epo receptor confers much higher levels of receptor expression (9) and thus greater phosphorylation of JAK2, which facilitates identification of phosphoamino acids by MS. The JAK2 protein was immunoprecipitated using αJAK2, resolved by SDS-PAGE, visualized by staining with Coomassie blue, and subjected to tryptic proteolysis. The resulting peptides were extracted from the gel and analyzed by liquid chromatography (LC)-tandem MS (MS/MS). Analysis of MS/MS spectra with Mascot revealed doubly charged peptide precursors corresponding to JAK2 tryptic peptides with amino acid sequence (p)Y868DPLQDNTGEVVAVK (Fig. 2A) and GME(p)Y966LGTK (Fig. 2B) with significance scores of 90 and 41, respectively. Accordingly, the probabilities that these sequences resulted from a random match were approximately 10−9 and 10−4, respectively. The E-values, i.e. the number of MS/MS spectrum matches in the RefSeq database characterized with equal or better Mascot scores than the selected match that are expected to occur by chance alone, were 3.9e-7 and 2.1e-2, respectively. Manual inspection and interpretation of fragment ions confirmed the Mascot-assigned peptide sequences. These results using MS support the 2D phosphopeptide maps identifying Tyr 868 and 966 as sites of JAK2 autophosphorylation.

Figure 2.

Phosphorylation of tyrosines 868 and 966 in JAK2 is detected by MS. The 293 cells overexpressing ELR and JAK2 were stimulated with Epo for 30 min. JAK2 was immunoprecipitated with αJAK2(758), resolved by SDS-PAGE, reduced, alkylated, and digested with trypsin. MS/MS spectrum corresponding to the doubly charged JAK2 tryptic peptides (A) (p)Y868DPLQDNTGEVVAVK (m/z 892.92) and (B) GME(p)Y966LGTK (m/z 503.76) were obtained. Sequence assignments with the expected m/z value for the b-type and y-type ions are noted. Underlined m/z values indicate fragment ions present in the MS/MS spectrum. Y-type ions (y), along with associated neutral losses of ammonia (y*), and water (y0) ions are indicated. Similarly, b-type ions (b), along with neutral losses of carbon monoxide (a) ions are identified. In Fig. 2A, [M+2H]2+ denotes the doubly charged peptide ion corresponding to (p)Y868DPLQDNTGEVVAVK. [M+H-2H2O-80]+ denotes the singly charged ion corresponding to (p)Y868DPLQDNTGEVVAVK, which has sustained neutral losses of water and phosphate. In Fig. 2B, the fragment corresponding to the PY-specific immonium ion (m/z = 216.043) is designated with a square.

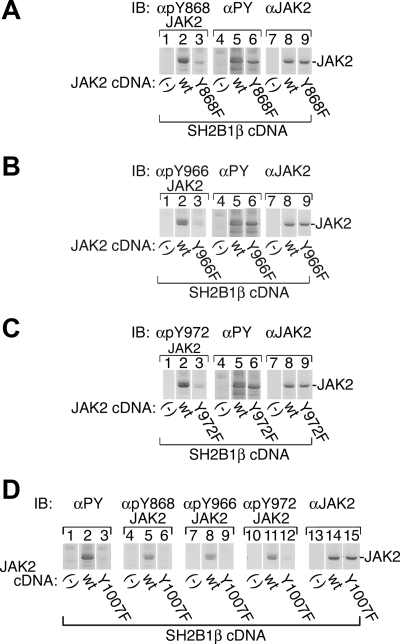

Phosphospecific antibodies indicate that JAK2 is phosphorylated at tyrosines 868, 966, and 972

To further confirm Tyr 868, 966, and 972 as sites of autophosphorylation in JAK2 and examine whether they are phosphorylated in response to cytokine stimulation, phosphospecific antibodies were prepared against peptides containing pTyr 868, pTyr 966, or pTyr 972. Antibodies prepared by Millipore Corp. (Bedford, MA)were initially screened against phosphorylated vs. nonphosphorylated peptides (data not shown). We then used the antibodies to confirm that active JAK2 expressed in mammalian cells (293T) is phosphorylated on Tyr 868, 966, and 972. To increase the overall tyrosyl phosphorylation of the JAK2 Y→F mutants, JAK2, JAK2 Y868F, JAK2 Y966F, and JAK2 Y972F were coexpressed with myc-tagged SH2B1β. All four forms of JAK2 exhibited substantial overall tyrosyl phosphorylation as assessed by blotting with antibody to PY (αPY, 4G10) (Fig. 3, A–C, lanes 5 and 6). αpTyr 868 JAK2 clearly recognized wild-type JAK2 (Fig. 3A, lane 2), but only recognized JAK2 Y868F to a very limited extent (Fig. 3A, lane 3). Similarly, wild-type JAK2 was readily recognized by αpTyr 966 (Fig. 3B, lane 2) and αpTyr 972 (Fig. 3C, lane 2), whereas JAK2 Y966F and JAK2 Y972F were only poorly recognized by αpTyr 966 (Fig. 3B, lane 3) and αpTyr 972 (Fig. 3C, lane 3), respectively. Although all three antibodies recognized autophosphorylated wild-type JAK2, none recognized the unphosphorylated, kinase-inactive JAK2 Y1007F (Fig. 3D, lanes 6, 9, and 12), confirming that the antibodies are specific to the phosphorylated form of the tyrosines, and do not recognize non-tyrosyl-phosphorylated JAK2. Figure 3, A–C, lanes 8 and 9, and Fig. 3D, lanes 14 and 15, show that expression of wild-type and mutated JAK2 was similar. Together, these data provide further support that Tyr 868, 966, and 972 are phosphorylated in JAK2.

Figure 3.

αpY868 JAK2, αpY966 JAK2, and αpY972 JAK2 identify tyrosines 868, 966, and 972, respectively, as sites of phosphorylation in JAK2. 293T cells transiently transfected with SH2B1β cDNA (1 μg) and the cDNAs (1 μg) for JAK2, JAK2 Y868F, JAK2 Y966F, JAK2 Y972F, JAK2 Y1007F, or vector were lysed. Proteins were resolved on SDS-PAGE gels and blotted [immunoblotted (IB)] with the indicated antibodies (n = 2). The migration of JAK2 is indicated.

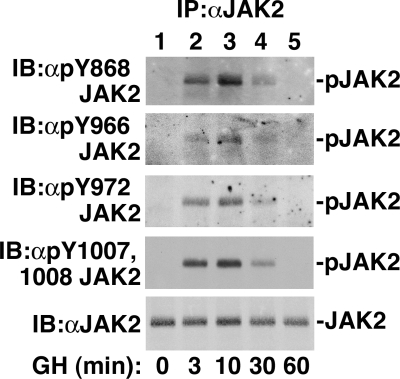

Phosphorylation of endogenous JAK2 at tyrosines 868, 966, and 972 is increased in response to GH

In most cells, endogenous JAK2 has low basal activity. Ligand binding to a JAK2-associated cytokine receptor then activates JAK2. GH robustly activates JAK2 in 3T3-F442A cells (15). To test whether Tyr 868, 966, and 972 are phosphorylated in endogenous JAK2 in response to ligand stimulation, 3T3-F442A cells were stimulated with 500 ng GH/ml or vehicle. When JAK2 was immunoprecipitated with αJAK2 and blotted with αpY868 JAK2, αpY966 JAK2, or αpY972 JAK2, phosphorylation of JAK2 at Tyr 868, 966, and 972, respectively, was increased by 3 min, remained elevated for at least 30 min, and was substantially diminished by 60 min (Fig. 4, top three panels). This time course is similar to that observed for JAK2 activation as assessed by blotting with αpY1007/1008 JAK2 (Fig. 4, fourth panel). Blotting with αJAK2 confirmed equal loading (Fig. 4, bottom panel). These data are consistent with a rapid and transient increase in phosphorylation at Tyr 868, 966, and 972 in endogenous JAK2 in response to GH.

Figure 4.

In response to GH, endogenous JAK2 is phosphorylated at tyrosines 868, 966, and 972. The 3T3-F442A cells were incubated with vehicle or 500 ng GH/ml (23 nm) for the indicated times. The cells were lysed. JAK2 was immunoprecipitated using αJAK2 and blotted [immunoblotted (IB)] with the indicated antibodies (n = 2 for 0, 10 min; n = 1 for 3, 30, 60 min; n = 3 for equivalent lysate blots, data not shown). The migration of JAK2 is indicated. IP, Immunoprecipitation.

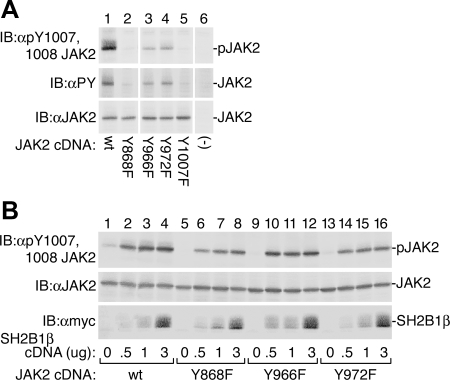

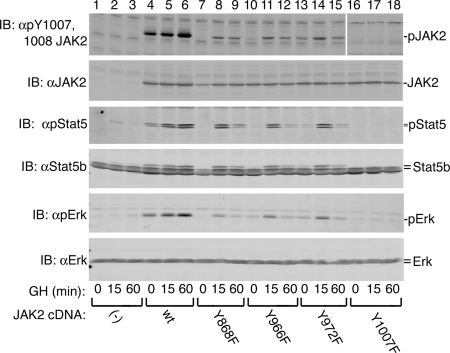

Tyrosines 868, 966, and 972 in overexpressed JAK2 are required for maximal JAK2 kinase activity

To gain insight into whether Tyr 868, 966, and 972 play a role in regulating JAK2 activity, we determined whether mutating these tyrosines to phenylalanine affected the kinase activity of JAK2. JAK2, JAK2 Y868F, JAK2 Y966F, JAK2 Y972F, and JAK2 Y1007F were transiently expressed in 293T cells. Mutating Tyr 966 and 972 to phenylalanine greatly diminished JAK2 activity as monitored by the phosphorylation of JAK2 at Tyr 1007, the critical tyrosine in the activation loop of JAK2 (Fig. 5A, lanes 3 and 4, top panel) or by overall tyrosyl phosphorylation (Fig. 5A, lanes 3 and 4, middle panel). Both phosphorylation at Tyr 1007/1008 and overall tyrosyl phosphorylation of JAK2 Y868F were severely depressed, to levels similar to that seen with JAK2 Y1007F (Fig. 5A, lanes 2 and 5). Blotting with αJAK2 indicated that the expression of the different JAK2s was comparable (Fig. 5A, bottom panel). These results indicate that when JAK2 is expressed at levels that lead to autoactivation, Tyr 868, 966, and 972 are required for maximal activity of the ectopically expressed JAK2.

Figure 5.

Mutating tyrosines 868, 966, or 972 in JAK2 to phenylalanine decreases the ability of JAK2 to autophosphorylate when JAK2 is expressed alone. Coexpression with SH2B1β partially restores kinase activity. A, 293T cells transiently transfected with the cDNA (1 μg) for JAK2 or the indicated JAK2 Y→F mutant were blotted [immunoblot (IB)] with the indicated antibodies (n = 2). The migration of JAK2 is indicated. B, 293T cells transiently transfected with the cDNA (1 μg) for JAK2 or the indicated JAK2 Y→F mutant and the indicated amount of the cDNA for SH2B1β were blotted (IB) with the indicated antibodies (n = 2). The migration of JAK2 and SH2B1β is indicated.

SH2B1β is known to bind to pY813 in JAK2 and activate JAK2 (10,16). To determine whether the presence of SH2B1β would restore the kinase activity of these JAK2 Y→F mutants, SH2B1β at three different levels was coexpressed with JAK2, JAK2 Y868F, JAK2 Y966F, and JAK2 Y972F in 293T cells (Fig. 5B). The expression of JAK2 was similar for the various mutant forms of JAK2 (Fig. 5B, middle panel), and SH2B1β expression was not affected by coexpression with the various JAK2s (Fig. 5B, bottom panel). As previously reported (10,16), coexpression of SH2B1β with wild-type JAK2 dramatically increased JAK2 activity as monitored by phosphorylation at Tyr 1007/1008 (Fig. 5B, top panel, lanes 1–4). Coexpression of SH2B1β also substantially increased the activity of JAK2 Y868F, JAK2 Y966F, and JAK2 Y972F to levels that approached those seen with wild-type JAK2 (Fig. 5B). Thus, it appears that mutation of these tyrosines does not cause JAK2 to be incapable of activation and that SH2B1β stabilizes these mutant JAK2s in an active conformation.

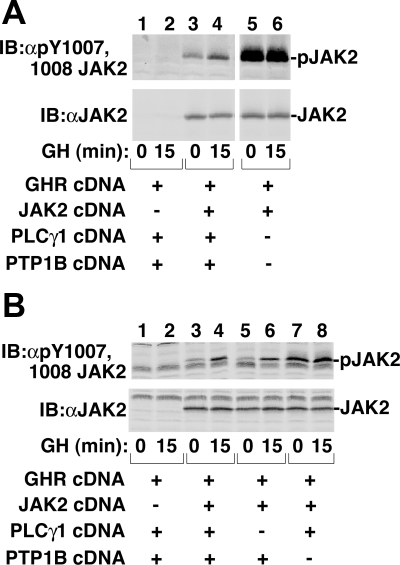

Overexpression of PTP1B enables detection of GH-dependent activation of JAK2 in 293T cells

Overexpressed JAK2 is often fully active and not responsive to further activation by GH. Thus, it has been difficult to determine whether mutations in JAK2 alter GH-dependent signaling. Recently, it was shown using NIH3T3 cells and various knockout mouse embryonic fibroblasts that, when complexed with JAK2, phospholipase Cγ1 (PLCγ1) and protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) attenuate GH-dependent activation of JAK2 (18). We hypothesized that in 293T cells, increased expression of PTP1B and PLCγ1 might suppress the high basal phosphorylation of overexpressed JAK2 and reset JAK2 to a state that would be responsive to GH-dependent activation. This would allow us to investigate the role of Tyr 868, 966, and 972 in GH-dependent activation of JAK2. To test this, we coexpressed in 293T cells GH receptor and JAK2 with and without PLCγ1 and PTP1B. After 15 min incubation with GH, cell lysates were immunoblotted with αpY1007/1008 JAK2. In the absence of PLCγ1 and PTP1B, basal activity of JAK2 was high (Fig. 6A, lane 5) and was not further increased in response to GH (Fig. 6A, lane 6). In cells expressing ectopic PLCγ1 and PTP1B, basal activity of JAK2 was substantially decreased and stimulation with GH increased the activity of JAK2 (Fig. 6A, lanes 3 and 4). In Fig. 6A, GH increased phosphorylation of Tyr 1007/1008 in JAK2 to 250% of control (no GH); the average increase was 230% ± 30% (sem, n =15) of control. This finding allowed us to investigate the effect of the various JAK2 mutants on the ability of GH to activate JAK2. Late in this study, we checked to confirm that overexpression of both PLCγ1 and PTP1B was required to achieve GH-dependent activation of JAK2. GH-dependent phosphorylation of JAK2 at Tyr 1007/1008, detected when both PLCγ1 and PTP1B were present (Fig. 6B, top panel, lanes 3 and 4), was also readily detected in the absence of overexpressed PLCγ1 (but presence of PTP1B) (Fig. 6B, top panel, lanes 5 and 6). In contrast, in the absence of overexpressed PTP1B (and presence of overexpressed PLCγ1), basal activity was substantially elevated (Fig. 6B, top panel, compare lanes 5 and 7), and further GH-dependent stimulation was only rarely detected (Fig. 6B, top panel, lane 8). Thus, ectopic expression of PTP1B appeared to be sufficient for detection of GH activation of JAK2 in this system. In contrast to overexpression of PTP1B, overexpression of the tyrosine phosphatases SHP1 or SHP2 neither lowered basal activity of JAK2 nor enabled detection of GH-dependent activation of JAK2 (data not shown), suggesting some specificity to the effect of PTP1B.

Figure 6.

PTP1B, but not PLCγ1, is necessary for GH-dependent phosphorylation of overexpressed JAK2 in 293T cells. 293T cells were transiently transfected with various combinations of the cDNAs encoding GH receptor (400 ng), JAK2 (320 ng), PLCγ1 (100 ng), and PTP1B (150 ng) as indicated. The cDNA for (A) Stat5b (100 ng) or (B) Stat3 (100 ng) was also transfected. The cells were incubated with vehicle or 500 ng GH/ml (23 nm) for 15 min. Cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and blotted [immunoblot (IB)] with the indicated antibodies (n = 2). The migration of JAK2 is indicated.

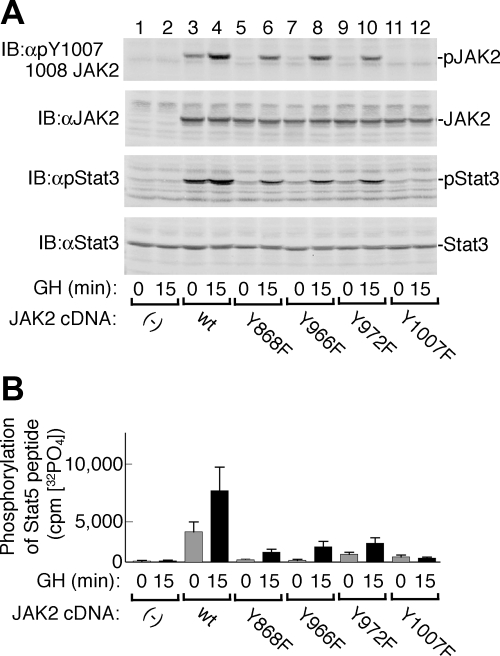

GH-bound GH receptor partially stabilizes JAK2 Y868F, JAK2 Y966F, and JAK2 Y972F in a kinase-active conformation

To gain insight into the role that Tyr 868, 966, and 972 have on the ability of GH to activate JAK2, in 293T cells we coexpressed PLCγ1 and PTP1B with GH receptor and JAK2 or one of the JAK2 Y→F mutants. The transfected cells were treated with or without 500 ng GH/ml for 15 min. JAK2 activity was assessed by blotting cell lysates with αpY1007/1008 JAK2 (Fig. 7A, top panel). Consistent with the results obtained when the JAK2 mutants were expressed in the absence of GH receptor (Fig. 5A), in the presence of GH receptor but absence of GH, wild-type JAK2 had some basal activity, whereas JAK2 Y868F, JAK2Y966F, and JAK2Y972F were essentially inactive (Fig. 7A, top panel, lanes 3, 5, 7, and 9). However, treatment with GH for 15 min substantially stimulated the activity of all four JAK2s (Fig. 7A, top panel, lanes 4, 6, 8, and 10), although the JAK2 activity at 15 min for the three JAK2 mutants was less than that observed with wild-type JAK2. To determine whether the changes in JAK2 activity translated into changes in the activity of downstream signaling pathways, Stat3 was also coexpressed, and phosphorylation of Stat3 on its critical Tyr 705 was assessed by blotting cell lysates with antibody to phosphorylated Tyr 705 (αpStat3) (Fig. 7A, panel 3). Phosphorylation of Stat3 on Tyr 705 is required for its activation (19). Levels of activated Stat3 followed the same pattern as levels of activated JAK2. Thus, basal (no GH) phosphorylation of Tyr 705 in Stat3 was easily detectable in the presence of wild-type JAK2 but barely or not detectable in the presence of JAK2 Y868F, JAK2 Y966F, and JAK2 Y972F (Fig. 7A, third panel, lanes 3, 5, 7, and 9). Treatment with GH stimulated Stat3 phosphorylation in cells expressing ectopic wild-type JAK2 as well as in cells expressing JAK2 Y868F, JAK2 Y966F, or JAK2 Y972F (Fig. 7A, third panel, lanes 4, 6, 8, and 10). In contrast, in cells expressing JAK2 Y1007F, basal and GH-stimulated phosphorylation of Stat3 were essentially absent. Thus, whereas JAK2 Y868F, JAK2 Y966F, and JAK2 Y972F, when expressed alone, have little or no detectable activity, in the presence of GH receptor, JAK2 Y868F, JAK2 Y966F, and JAK2 Y972F can all be activated in response to GH.

Figure 7.

Basal and GH-stimulated activation of JAK2 Y868F, JAK2 Y966F, or JAK2 Y972F is decreased compared with wild-type JAK2. The 293T cells were transiently transfected with cDNA encoding GH receptor (400 ng), PTP1B (150 ng), PLCγ1 (100 ng), Stat3 (100 ng), myc-ERK1 (100 ng), and either JAK2, JAK2 Y868F, JAK2 Y966F, JAK2 Y972F, or JAK2 Y1007F (320 ng) as indicated. The cells were incubated with vehicle or 500 ng GH/ml (23 nm) for 15 min. A, Cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and blotted [immunoblot (IB)] with the indicated antibodies (n = 5). The migration of JAK2 and Stat3 is indicated. B, JAK2 was immunoprecipitated using αJAK2 and subjected to an in vitro kinase assay in the presence of 1 μm ATP and 500 μm of a peptide containing Tyr699 of Stat5. Background equal to the average 32P (3965 cpm) incorporated into the control cells [(−) JAK2 cDNA, 0 min GH] was subtracted from all conditions (n = 3). Error bars represent the sem. GH caused a statistically significant (P < 0.05) increase in activity of JAK2 WT, JAK2Y868F, JAK2Y966F, and JAK2Y972F. When compared with JAK2 WT, both the basal and GH-stimulated activity of all of the JAK2 Y→F mutants was decreased to a statistically significant extent. WT, Wild type.

To measure more directly the enzymatic activity of the JAK2 mutants, proteins in cell lysates from control and GH-treated 293T cells from Fig. 7A were immunoprecipitated with αJAK2, and the activity of the isolated JAK2 was determined in an in vitro kinase assay using a peptide containing Tyr 699 in Stat5 as substrate. In this peptide-based kinase assay, moderate basal and elevated GH-stimulated levels of activity were detected for wild-type JAK2 (Fig. 7B). For the JAK2 mutants lacking Tyr 868, 966, 972, or 1007, the basal activity of JAK2 measured in this in vitro kinase assay was low. After GH stimulation, the in vitro kinase activity associated with JAK2 Y868F, JAK2 Y966F, and JAK2 Y972F increased to a limited extent. As expected, no GH-dependent stimulation of activity was detected with JAK2 Y1007F. These results, using both antibodies to pY1007 and in vitro kinase assays, indicate that 15 min with GH stimulates the kinase activity of JAK2 Y868F, JAK2 Y966F, and JAK2 Y972F, although to a reduced level compared with wild-type JAK2.

GH activation of Stat5b and ERK1 is reduced in JAK2 with tyrosines 868, 966, or 972 mutated to phenylalanine

To determine whether the suppression in enzymatic activity detected at 15 min for the various JAK2 Y→F mutants would be evident at later time points, and to test the effect of the mutations on the ability of GH to stimulate phosphorylation of Stat5b and activate ERK1/2, 293T cells overexpressing the various JAK2s along with GH receptor, PTP1B, PLCγ1, Stat5b, and ERK1 were stimulated with 500 ng GH/ml for 0, 15, or 60 min. The longer time course revealed that with wild-type JAK2, phosphorylation at Tyr 1007/1008 increased for at least the first 60 min after GH addition (Fig. 8, top panel). With JAK2 Y868F, JAK2 Y966F, and JAK2 Y972F, GH-stimulated phosphorylation at Tyr 1007/1008 was modest, peaking at 15 min with a slight downward trend evident by 60 min. Stat5b activation was assessed using an antibody (αpStat5) to the phosphorylated form of the critical tyrosine (Tyr 699) present in both Stat5a and b. ERK activity was assessed by blotting with an antibody (αpERK) to the doubly phosphorylated, activated form of ERK. As seen with JAK2 activity, GH-dependent activation of Stat5b (Fig. 8, third panel) and ERK1 (Fig. 8, fifth panel) was higher after 60 min than after 15 min in wild-type JAK2-expressing cells, whereas in cells expressing JAK2 Y868F, JAK2 Y966F, or JAK2 Y972F, the phosphorylation of Stat5b and ERK1 detected after 15 min of GH treatment was reduced by 60 min. No GH activation of Stat5b or ERK1 was detected in cells expressing JAK2 Y1007F. Expression of Stat5b, ERK1, and the different JAK2s did not vary across the experimental conditions (Fig. 8, second, fourth, and sixth panels). Similar results were observed for ectopically expressed Stat3 (data not shown).

Figure 8.

Effect of mutating tyrosines 868, 966, and 972 on the ability of JAK2 to phosphorylate Stat5b and ERK1. The 293T cells were transfected with cDNA encoding GH receptor (400 ng), Stat5b (100 ng), PLCγ1 (100 ng), PTP1B (150 ng), and either JAK2 WT, JAK2 Y868F, JAK2 Y966F, JAK2 Y972F, or JAK2 Y1007F (320 ng) as indicated. Cells were incubated with vehicle or with 500 ng GH/ml (23 nm) for 15 or 60 min and then lysed. Proteins were resolved on SDS-PAGE gels and blotted [immunoblot (IB)] with the indicated antibodies (n = 4). The migration of JAK2, Stat5b, and ERK is indicated. WT, Wild type.

Discussion

JAK2 is a kinase essential for signaling by numerous cytokines and hormones. Therefore, understanding how JAK2 functions and is regulated is of fundamental importance for many aspects of cellular physiology. In this work, we used multiple approaches to identify three sites of JAK2 autophosphorylation, Tyr 868, 966, and 972, that lie within the kinase domain of JAK2. We initially identified all three sites as sites of autophosphorylation using site-directed mutagenesis combined with 2D phosphopeptide mapping of JAK2 overexpressed in a mammalian expression system and autophosphorylated in an in vitro kinase assay. Consistent with the 2D phosphopeptide mapping results, phosphorylation of all three of these tyrosines (868, 966, and 972) has also been detected by MS. Although our work is the first to identify Tyr 868 as a site of autophosphorylation, phosphorylation at Tyr 966 was recently detected during an MS-based global survey of PY signaling in lung cancer (13), and Tyr 972 was identified by MS as a site of phosphorylation in JAK2 ectopically expressed in African green monkey BSC40 epithelial cells (20). Tyr 966 and 972 had been preliminarily identified as sites of JAK2 autophosphorylation by comigration of 32P-containing tryptic JAK2 peptides with synthetic peptides in 2D phosphopeptide maps and by HPLC (7). Our use of phosphospecific antibodies provided evidence that Tyr 868, 966, and 972 are phosphorylated in endogenous JAK2 and that phosphorylation is increased in response to cytokine (e.g. GH) stimulation.

With the identification of phosphorylation at Tyr 868, 966, and 972, at least six tyrosines within the kinase domain of JAK2 are now known to be autophosphorylated: Tyr 868, 966, and 972, as well as Tyr 913 (8), 1007, and 1008 (5,6,12,13). Global surveys using phosphoproteomics (13,14) or comigration of peptides (7) suggest that other tyrosines (918, 931, 934, 940, 945) in the kinase domain of JAK2 may also be phosphorylated, but further analysis is needed to validate these tentatively identified sites. Tyr 868, 966, and 972 are conserved in JAK2 from human to fish. Tyr 868 and 966 are also conserved in the other JAK family members (JAK1, JAK3, and TYK2), whereas Tyr 972 is conserved in JAK1, JAK2, TYK2, and carp JAK3, but not in human, rat, mouse, or puffer fish JAK3. This conservation suggests that all three sites are likely to be critical components of JAK signaling. It also seems likely that the homologous tyrosines in the other JAKs might autophosphorylate. In support of this, Tyr 939 in JAK3 (the equivalent of Tyr 966 in JAK2) has been reported to be phosphorylated in response to activation of JAK3 by IL-2 and IL-9 (21).

Our initial studies with the various JAK2 mutants in 293T cells revealed that the basal activity of JAK2 when JAK2 was expressed alone was almost totally abrogated by mutation of the various tyrosines to phenylalanines. This observation initially led us to believe that the activities of JAK2 Y868F, JAK2 Y966F, and JAK2 Y972F were severely compromised. The realization, that coexpression of JAK2, GH receptor, and the phosphatase PTP1B partially reconstituted GH-dependent activation of wild-type JAK2, provided the basis for an assay to investigate the ability of these mutants to respond to GH. Whereas the JAK2 Y→F mutants remained very inactive in the absence of GH, in stark contrast to the elevated basal activity of wild-type JAK2, the activity of the mutants approached that of wild-type JAK2 after 15 min of GH as measured by phosphorylation at Tyr 1007/1008 and phosphorylation of Stat3 or Stat5. Thus, with the mutated JAK2s, GH binding to the GH receptor-JAK2 complex appeared to shift the conformation of JAK2 in the vicinity of Tyr 868, 966, and 972, respectively, to a conformation that was at least partially active. Surprisingly, SH2B1β, which binds to Tyr 813 of JAK2 (10), is also able to stabilize these JAK2 Y→F mutants. Thus, the regions of JAK2 surrounding Tyr 868, 966, and 972 appear to be stabilized in an active conformation by several mechanisms including association and stabilization of JAK2 by SH2B1β or GH-bound GH receptor and, presumably, by phosphorylation of Tyr 868, 966, and 972.

However, even though the GH-GH receptor complex is initially able to stabilize JAK2 Y868F, JAK2 Y966F, and JAK2 Y972F in active conformations, the activation is transient, and long-term activation of the JAK2 Y→F mutants appears to be substantially less robust than the extended activation detected with wild-type JAK2. Presumably, competition between GH-dependent activation of JAK2 and inactivation by PTP1B (and perhaps other endogenous phosphatases) regulates the phosphorylation detected at Tyr 1007/1008 and the level of activation of JAK2. The elevated basal phosphorylation of wild-type JAK2 detected after serum deprivation would suggest that with wild-type JAK2, the equilibrium between activation and inactivation remains tilted toward activation even during a prolonged period of serum deprivation. Even a small decrease in the intrinsic activity of the various JAK2 constructs, if unaccompanied by a corresponding decrease in rate of inactivation, could lead over time to the substantially decreased levels in Tyr 1007/1008 phosphorylation seen by 60 min in JAK2 Y868F, JAK2 Y966F, and JAK2 Y972F compared with wild-type JAK2. It could similarly lead to the decreased basal phosphorylation detected after serum deprivation in JAK2 Y868F, JAK2 Y996F, and JAK2 Y972F compared with wild-type JAK2.

Consistent with our findings that suggest that Tyr 868, 966, and 972 in JAK2 are phosphorylated, phosphorylation at sites homologous to Tyr 868, 966, and 972 in JAK2 has been detected in other kinases. Phosphorylation of the tyrosine at the position equivalent to Tyr 966 in JAK2 has been reported for at least 15 other kinases. As we report here for Tyr 966 in JAK2, the equivalent tyrosine in JAK3, recepteur d’origine nantais (RON), Raf, and ribosomal S6 kinase 2 (RSK2) has been reported to be required for maximal kinase activity. In JAK3, mutation of Tyr 939 to phenylalanine substantially reduced JAK3 enzymatic activity as assessed by in vitro kinase assays and phosphorylation of the downstream substrate Stat5a (21). In RON, Tyr 1175 appears to be one of several tyrosines required for full kinase activity (22). In the serine/threonine kinase Drosophila Raf, mutating Tyr 538 to phenylalanine abolishes serine/threonine kinase activity of Drosophila Raf toward its substrate Dsor (23). In contrast, the phosphorylation of Tyr 529 by fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-activated FGF receptor 3 (24) or epidermal growth factor-activated Src (25) appears to activate RSK2 kinase indirectly by contributing to a conformational change that permits RSK2 to bind to its activating kinase ERK at a site remote from Tyr 529 (26,27). The equivalent of Tyr 966 is also phosphorylated in Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (13,14), ephrin receptor (Eph) A3, EphA5, EphA6 (14), EphB2 (28,29), EphB6 (28), FGF receptor 1 (30), insulin receptor (13,14,31), JAK3 (21), RON (22), and the serine/threonine kinases calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase 1α (13,14), microtubule-associated serine/threonine kinase (MAST)1, MAST4 (13,14), A-Raf (32), and RSK2 (24,25).

Also in agreement with our results, McDoom et al. (20) reported that Tyr 972 in JAK2 is required for maximal JAK2 activity. Similar to what we report here, they observed that when Tyr 972 is mutated to phenylalanine, basal JAK2 activity as assessed by blotting with αpY1007/1008 JAK2, and αPY is suppressed substantially. However, GH retains some ability to stimulate tyrosyl phosphorylation of JAK2 Y972F. Interestingly, when JAK2 signaling downstream of the G protein-coupled angiotensin receptor was investigated, mutating Tyr 972 resulted in a complete loss of the ability of angiotensin II to activate JAK2 as monitored by blotting of JAK2 with αPY. Thus, the various receptors for JAK2 (e.g. GH receptor and angiotensin II receptor) appear to stabilize the region of JAK2 in the vicinity of Tyr 972 to varying extents, which suggests that the binding sites between JAK2 and its various cognate receptors, or some other component of signaling, vary in a significant way. The residue homologous to Tyr 972 in JAK2 is also phosphorylated in EphA2 (14,33), EphB2 (28,29,34), EphB3 (13,14), EphB6 (28), and the serine/threonine kinases MAST1 and MAST4 (13,14). Although EphA2 Y734F is reported to be as active as wild-type EphA2, mutation of Tyr 734 to phenylalanine disrupts binding to the p85-regulatory subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase, and EphA2 Y734F is defective in Rac1 activation, cell migration, ephrin-A1-induced vascular assembly, and tumor angiogenesis (33). Thus, in EphA2, the tyrosine equivalent to Tyr 972 in JAK2 appears to play a role in recruiting signaling proteins to the EphA2-JAK2 signaling complex. The equivalent of Tyr 868 is phosphorylated in two tyrosine kinases, focal adhesion kinase (14,35,36) and Lyn (14), and the serine/threonine kinase Mos (13,14). However, the function of this tyrosine in these kinases has not been reported.

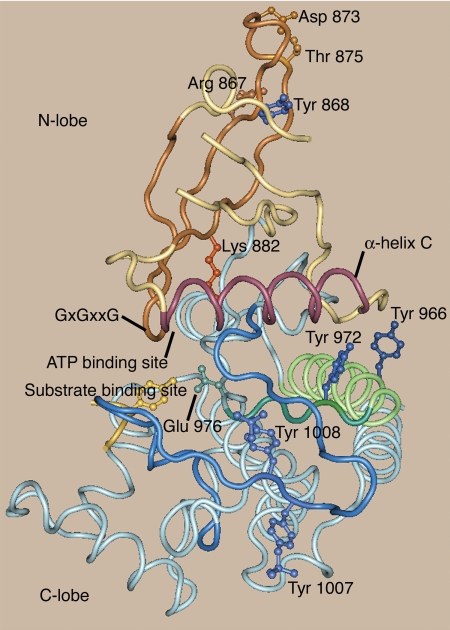

To gain insight into how phosphorylation of Tyr 868, 966, and 972 might regulate JAK2 activity, we turned to the crystal structure of the kinase domain of JAK2. In the crystal structure of the kinase domain of JAK2 complexed with either the ATP analog 2-tert-butyl-9-flouro-3, 6-dihydro-7H-benz[h]-imidaz[4,5-f]isoquinoline-7-one [2B7A (12)] or the JAK2 inhibitor 5-bromo-3-aminoindazole [3E62 (37)], Tyr 868, 966, and 972 are predicted to be exposed to solvent, consistent with all three tyrosines being available for phosphorylation. Tyr 966 is in α-helix E (His 950–Lys 970), and Tyr972 is in β-strand 6 (Arg 971–Arg 975) on the side of the kinase domain opposite from the catalytic site (Fig. 9). Because the proper orientation of the N- and C-lobes is essential for kinase activity (38,39,40,41), the fact that Tyr 966 and Tyr 972 are positioned at the interface between the C- and N-lobe of the kinase domain suggests a role in modulating JAK2 kinase activity. Furthermore, the orientation of α-helix C plays a critical role in stabilizing the position of the essential lysine in the catalytic cleft of kinases, and during kinase activation the orientation of α-helix C often shifts (39). Thus, the proximity of Tyr 972, and to a lesser extent Tyr 966, to α-helix C (Glu 889–Ser 904) of JAK2 (Fig. 9) suggests that phosphorylation of Tyr 972 and Tyr 996 in JAK2 could play a role in shifting the conformation of JAK2 to a catalytically competent conformation.

Figure 9.

Position of tyrosines 868, 966, and 972 in the structure of JAK2 [2B7A (12)]. Tyr 966 and Tyr 972 are in the C-lobe of the JAK2 kinase domain. Tyr 966 is in α-helix E (green) and Tyr 972 in β-strand 6 (dark green). Tyr 972 is in close proximity to α-helix C (mauve) in the N-lobe. The α-helix C plays a critical role in positioning the ATP in the active site. When the kinase domain is in the active conformation, Tyr 972 is in close proximity to the activation loop (dark blue). Tyr 868 is in the N-lobe of the kinase domain in β-strand 2. The top of the catalytic cleft is formed by β-strand 1, β-strand 2, and β-strand 3 (brown). The Gly-X-Gly-X-X-Gly 861 ATP binding motif is in the turn between β-strand 1 and β-strand 2. Lys 882, which binds to the α- and β-phosphates of the bound ATP, is in β-strand 3. Mutations in the region surrounding Tyr 868 have been linked to acute megakaryoblastic leukemia (Thr 875Arg) (43) and pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Arg 867Gln or Asp 873Arg) (44). The substrate tyrosine (light gold) is modeled into the substrate-binding site based on the closely related structure of the insulin receptor [1IR3 (56)]. The N-lobe is in brown-mauve tints. The C-lobe is in blue-green tints.

Tyr 868 is located in β-strand 2 (Phe 860–Asp 869) of the N-lobe. β-Strand 2 is one of three β-strands that form the top of the catalytic cleft (Fig. 9). The Gly-X-Gly-X-X-Gly 861 nucleotide-binding motif is in the turn between β-strand 1 and β-strand 2. Lys 882, the critical lysine in the kinase domain that is essential for phosphate transfer, is located in β-strand 3. Tyr 868 is therefore well positioned for its phosphorylation to alter the conformation of the catalytic cleft. A critical regulatory role for the region in JAK2 surrounding Tyr 868 is also suggested by the fact that mutations in β-strand 2 and the loop between β-strands 2 and 3 have major effects on JAK2 activity. Mutation of Cys 866 to alanine dramatically decreases JAK2 kinase activity, as measured using an in vitro kinase assay (42). A constitutively active JAK2 with a Thr 875Asn mutation was isolated from a cell line derived from a patient with acute megakaryoblastic leukemia (43). Constitutively active JAK2s harboring either Arg 867Gln or Asp 873Asn mutations were isolated from patients with pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia (44).

In summary, we used three different approaches to show that, in addition to tyrosine 1008 and tyrosine 1007, which corresponds to the activating tyrosine present in all tyrosine kinases, Tyr 868, 966, and 972 are autophosphorylated in JAK2. We have used phosphospecific antibodies to suggest that a ligand-dependent increase in phosphorylation at all three of these tyrosines occurs in both overexpressed and endogenous JAK2. Tyr 868 is a particularly intriguing site of phosphorylation because it has been detected in only a small subset of kinases and is located in a region of JAK2, the mutation of which is associated with acute megakaryoblastic leukemia and pediatric acute lymphatic leukemia. We have also demonstrated that mutation of any one of these tyrosines to phenylalanine dramatically decreases the kinase activity of ectopically expressed JAK2, which is normally constitutively active. Somewhat surprisingly, SH2B1β, a known activator of JAK2, and GH-bound GH receptor are able to restore, at least partially, the activity of these JAK2 mutants and signaling pathways downstream of them (i.e. Stat3, Stat5, and/or ERK1). Thus, in contrast to what is observed with the insulin receptor, which appears to contain a single primary activating tyrosine (equivalent to Tyr 1007 in JAK2), full activation of JAK2 appears to require phosphorylation of at least five tyrosines (i.e. 868, 966, 972, 1007, and 1008). Based on these findings and analysis of the crystal structure of the kinase domain of JAK2, we hypothesize that the regions of JAK2 surrounding Tyr 868, Tyr 966, and Tyr 972 are important conformational switches. These regions are partially stabilized when the Y→F mutants of JAK2 are complexed to GH-bound GH receptor or to SH2B1β. Presumably phosphorylation of the respective tyrosines also contributes to maintaining these regions in the maximally active conformation.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Recombinant 22,000-Da human GH was a gift from Eli Lilly & Co. (Indianapolis, IN). Synthetic Epo (Epogen) was obtained from Amgen, Inc. (Thousand Oaks, CA). cDNA encoding myc-tagged ERK1 was from K. L. Guan (University of California at San Diego, San Diego, CA). Rat GH receptor cDNA in pMTGH vector (45) was from L. Mathews (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI). Murine JAK2 cDNA in the prk5 vector (46) was kindly provided by J. Ihle (St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN). For the experiments using Epo, the JAK2 cDNA was in pcDNA3 (47). The pcDNA3 vector containing the cDNA for the chimeric ELR LRb has been described elsewhere (48). PLCγ1 cDNA in prk5 was from B. Margolis (University of Michigan). Rat PTP1B cDNA in pCMV5 (49) was from J. E. Dixon (University of California at San Diego). Myc-tagged rat SH2B1β and myc-tagged rat SH2B1β (504-670) cDNAs have been described elsewhere (50). Rat Stat5b cDNA in the pRc/CMV vector was a gift of L. Yu-Lee (51) (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX). Mouse Stat3 cDNA in the pcDNA1 vector was a gift of D. Levy (New York University, New York, NY). [γ-32P]ATP (6000 Ci/mmol) was from BP Biomedical (Foster City, CA). BSA was from Serologicals (Norcross, GA) (CRG-7) or Proliant (Ankeny, IA), and DMEM was from Cambrex (Walkersville, MD). Coomassie brilliant blue G-250 stain was from Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc. (Hercules, CA). Triton X-100, leupeptin, and aprotinin were from Roche (Indianapolis, IN). Protein A agarose was from Repligen Corp. (Waltham, MA) or Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Nitrocellulose paper was from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Piscataway, NJ). Protein molecular weight standards were from Invitrogen. Polyvinylpyrrolidone and phosphoamino acid standards were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis kits were from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). The Stat5 peptide, AKAADGY699VKPQIKQVV, was prepared by the Peptide and Proteomics Core of the Michigan Diabetes Research and Training Center (University of Michigan). Methylated trypsin was from Promega Corp. (Madison, WI). Thin-layer chromatography plates were from EM Science (Gibbstown, NJ).

Antibodies

Polyclonal antibody to JAK2 (αJAK2) used for immunoprecipitation (1:100 dilution) was raised against a peptide corresponding to amino acids 758-776 of murine JAK2 by the Carter-Su laboratory in conjunction with Pel-Freez Biologicals (Rogers, AR) or by the Myers laboratory (αJAK2(758); Fig. 2). The monoclonal αJAK2 antibodies used for immunoblotting (1:2000 dilution) were from Invitrogen (AH01352) or Millipore (clone 8E10.2; Figs. 5, 6, and 8). Antibody recognizing phosphorylated Tyr 1007 and 1008 of JAK2 (αpY1007/1008 JAK2) (1:2,000 dilution) was prepared as described previously (9) or purchased from Millipore. Antibodies recognizing phosphorylated Tyr 868, 966, and 972 of JAK2 (αpY868 JAK2 (no. 09-203), αpY966 JAK2 (no. 09-264), and αpY972 JAK2 (no. 09-243), respectively) were prepared in collaboration with Millipore (1:1000, Fig. 3; or 1:250, Fig. 4). IRdye 800-conjugated antimouse antibody was from Rockland Immunochemicals (Philadelphia, PA) or LI-COR Biosciences (Lincoln, NE), and IRdye 700-conjugated antirabbit antibody was from LI-COR (both used at 1:20,000). Protein A horseradish peroxidase was from Amersham. Anti-PY antibody 4G10 (αPY) (1:7500 dilution) was from Millipore. Antibody to SH2B1β (used at 1:2000) (50) was a kind gift of L. Rui (University of Michigan). Antibody to Stat3 (αStat3) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) and antibody to phosphorylated Tyr 705 of Stat3 (αpStat3) (Millipore) were both used at a dilution of 1:7500. Antibody to Stat5b (αStat5b) raised against amino acids 711–727 of murine Stat5b (no. 835) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (1:5000 dilution), and antibody to phosphorylated Tyr 699 of Stat5b/5a (αpStat5b) was from Zymed Laboratories, Inc. (South San Francisco, CA)(1:1000 dilution). Antibody that recognizes both ERKs 1 and 2 (αERK) and antibody to ERKs 1 and 2 doubly phosphorylated on Thr 202/Tyr 204 (αpERK; E10) were both from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA) and used at 1:2000.

Subcloning and mutagenesis

Preparation of Prk5-JAK2 Y1007F was previously described (6). QuikChange Mutagenesis kits from Stratagene were used for site-directed mutagenesis. The primers (sense strand, mutation in lowercase) used were: for Prk5-JAK2 Y868F (5′-GGAGATGTGCCGCTtTGACCCGCTGCAGGACAACAC-3′); Prk5-JAK2 Y913F (5′-CAGCATGACAACATCGTCAAGTtCAAGGGAGTGTGC-3′); Prk5-JAK2 Y918F (5′-GTCAAGTACAAGGGAGTGTGCTtCAGTGCGGGTCG-3′); Prk5-JAK2 Y931F (5′-GGGTCGGCGCAACCTAAGATTAATTATGGAATtTTTACCATATGG-3′); Prk5-JAK2 Y934F (5′-GGAATATTTACCATtTGGAAGTTTACGAGACTATCTCC-3′); Prk5-JAK2 Y940F (5′-GGAAGTTTACGAGACTtTCTCCAAAAACATAAAGAACGGATAG-3′); Prk5-JAK2 Y956F (5′-CTTCTTCAATtCACATCTCAGATATGCAAGGGCATGG-3′); Prk5-JAK2 Y966F (5′-GCAAGGGCATGGAATtTCTTGGTACAAAAAGGTATATCC-3′); Prk5-JAK2 Y972F (5′-CTTGGTACAAAAAGGTtTATCCACAGGGACCTGGC-3′); Prk5-JAK2 Y1008F (5′-GCCGCAGGACAAAGAATACTTCAAAGTAAAGGAGCC-3′); Prk5-JAK2 Y1021F (5′-GCCCCATATTCTGGTtCGCACCTGAATCCTTGACGG-3′); Prk5-JAK2 Y1045F (5′-GCTTTGGAGTGGTTCTATtCGAACTTTTCACATACATCG-3′); Prk5-JAK2 Y1050F (5′-GGAGTGGTTCTATACGAACTTTTCACATTCATCGAGAAGAG-3′); Prk5-JAK2 Y1099F (5′-GCCCAGATGAGATTTtTGTGATCATGACAGAGTGC-3′); pcDNA3-JAK2-Y868F (5′-GTGGAGATGTGCCGCTtTGACCCGCTGCAGGACAAC-3′); pcDNA3-JAK2-Y966F (5′-GATATGCAAGGGCATGGAATtTCTTGGTACAAAAAGGTATATCC-3′); and pcDNA3-JAK2-Y972F (5′-TATCTTGGTACAAAAAGGTtTATCCACAGGGACCTGGC-3′). Mutations were verified by DNA sequencing. Amino acids are numbered according to National Center for Biotechnology Information accession no. NP_032439.2.

Cell culture and transfection

Murine 3T3-F442A cells and human embryonic kidney 293T cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 8% calf serum and 100 U of penicillin per ml, 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, 0.25 μg of amphotericin B per ml, and 1 mml-glutamine (feeding medium). The stock of 3T3-F442A fibroblasts was kindly provided by H. Green (Harvard University, Boston, MA). 293T cells (10-cm plates) were transfected with the cDNAs indicated in the figure legends using calcium phosphate precipitation (52). Empty expression vector was used to normalize the total amount of DNA in transfections to 2.0 μg DNA. Cells were washed twice with DMEM 6 h after transfection and incubated with feeding medium. Cells were used 24 h after transfection. For GH time courses, cells were preincubated overnight in serum-free medium containing 1% BSA.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting

Cells were washed with ice-cold PBS (10 mm sodium phosphate, 137 mm NaCl) containing 1 mm Na3VO4, pH 7.4, and solubilized in 50 mm Tris; 0.1% Triton X-100; 137 mm NaCl; 2 mm EGTA; 1 mm Na3VO4; 10 μg aprotinin/ml; 10 μg leupeptin/ml; 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, pH 7.5 (lysis buffer). Lysed cells were centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant (cell lysate) was incubated with the indicated antibody on ice for 2 h. Protein A agarose was added, and the vials were rotated at 4 C for 1 h. Immunoprecipitates were washed three times with lysis buffer and eluted with a mixture (80:20) of lysis buffer and SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Immunoprecipitated proteins and proteins in cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies, and visualized using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences) or protein A horseradish peroxidase followed by detection using enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL; Fig. 4). Immunoblots were quantified using LI-COR Odyssey 2.1 software.

2D Phosphopeptide mapping

In vitro kinase assays were performed as described previously (15). Briefly, cells were washed with PBS and solubilized in lysis buffer in the absence of Na3VO4. Cell lysates were incubated with αJAK2. Immune complexes were precipitated using protein A agarose and washed with lysis buffer (no Na3VO4) and then with kinase buffer (50 mm HEPES; 100 mm NaCl; 5 mm MnCl2; 0.5 mm dithiothreitol; 1 mm Na3VO4, pH 7.6). Immobilized JAK2 was incubated in kinase buffer containing 0.5 mCi [γ-32P]ATP, 40 μg aprotinin/ml, and 40 μg leupeptin/ml at 30 C for 30 min, washed five times with lysis buffer, and eluted by boiling in a mixture (80:20) of lysis buffer and SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE (5–12% gradient), transferred to nitrocellulose, and visualized with a phosphor imager (Bio-Rad model 505). The 32P-labeled JAK2-containing band was cut from the nitrocellulose, soaked in 100 mm acetic acid containing 0.5% polyvinylpyrrolidone at 37 C for 30 min, washed with H2O, and digested with 5 μg of sequencing grade methylated trypsin at 37 C for 4 h. Digested peptides were lyophilized, oxidized with performic acid, and relyophilized. Peptides (20,000 cpm) were separated by thin-layer electrophoresis at pH 1.9 followed by thin-layer chromatography using phosphochromatography buffer (17). The 32P-labeled spots in the 2D phosphopeptide maps were visualized with a phosphor imager. To facilitate comparison of the various 2D phosphopeptide maps, the contrast and brightness of the maps were adjusted using PhotoShop 8.0 so that the intensity of the spots were roughly equivalent between maps. The maps were resized so that, relative to the origin, the horizontal and vertical migration of the spot corresponding to the peptide containing tyrosine 221 (6) was the same for all the maps. Calculation of the theoretical migration of peptides in 2D phosphopeptide maps is based on the parameters of Boyle et al. (17) as calculated using a program written in Microsoft Excel (6).

In vitro kinase assay

293T cells were transfected using calcium phosphate precipitation with 320 ng cDNA encoding JAK2 or various JAK2 Y→F mutants as indicated and cDNA for GH receptor (400 ng), PTP1B (150 ng), PLCγ1 (100 ng), myc-ERK1 (100 ng), Stat3 (100 ng), and 830 ng vector. Cells were incubated in serum-free medium overnight before 500 ng GH/ml was added for 15 min. αJAK2 immunoprecipitates were washed in 50 mm HEPES, 0.5 mm dithiothreitol, 100 mm NaCl, 1 mm NaVO4, 5 mm MnCl2 (pH 7.5). Mn2+ was used instead of Mg2+ in this assay because JAK2 is 3 times more active in the presence of Mn2+; 4 μm Mn2+ was found to be equipotent to 2 mm Mg2+ (53). [γ-32P]ATP (10 μCi), nonradioactive ATP, and a Stat5 peptide containing Tyr 699 were added to yield a final concentration of 1 μm ATP and 500 μm Stat5 peptide. After 15, 30, and 45 min at 30 C, vials were centrifuged, and an aliquot of the supernatant was spotted on p81 paper. The p81 paper was washed in 75 mm H3PO4, scintillation fluid (Cytoscint; BP Biomedical) was added, and bound 32P was counted using a Packard scintillation counter. The reaction was nonlinear above 20 min. Therefore, the velocity was determined from the 15-min time point. Statistical significance was determined using Student’s one-tailed, paired t test using Prism 3.0 from GraphPad (San Diego, CA).

Identification of phosphorylation sites by mass spectroscopy

For preparation of protein for liquid chromatography (LC)-tandem MS (MS/MS) analysis, subconfluent 293 cells were transfected with 15 μg of pcDNA3-ELR and 10 μg of pcDNA3-JAK2 (per 15-cm plate). The cells were made quiescent by overnight incubation in DMEM containing 0.5% BSA and stimulated with Epo at 37 C for 30 min. Cells were lysed in 20 mm Tris (pH 7.4), 137 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 1% glycerol, 50 mm β-glycerophosphate, 50 mm NaF, 1% Nonidet P-40, 2 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 2 mm Na3VO4. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 16,000 × g at 4 C for 20 min. Material from five to 10 plates was immunoprecipitated with αJAK2(758), and resolved on a single lane of a 7% SDS-PAGE gel. JAK2 protein was visualized with Coomassie brilliant blue G-250 stain. JAK2 was excised, destained, reduced, and alkylated as described elsewhere (54). Proteolytic digestion was carried out with 13 ng/μl sequencing-grade trypsin (Promega) in 25 mm ammonium bicarbonate at 37 C for 18 h. The resulting peptides were eluted with 60% methanol/5% acetic acid and lyophilized. Esterification and IMAC (immobilized metal affinity chromatography) enrichment were performed with optimized buffers described previously (55). IMAC-enriched phosphopeptides were loaded off-line onto a fused silica precolumn (8 cm × 75 μm) packed with 5–15 μm spherical C18 beads (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). HPLC was performed with a high-performance analytical column (8 cm × 50 μm) packed with 5 μm-diameter C18 reverse-phase beads (YMC, Wilmington, NC) (55). The estimated effluent flow rate was 20–50 nl/min. HPLC solvent A was 0.2 m acetic acid, and solvent B was 70% acetonitrile/0.2 m acetic acid. The solvent gradient was varied from 0–5% B in 5 min and 5–100% B in 35 min. MS data acquisition was performed on a QSTAR XL (MDX/SCIEX) instrument operated in information dependent mode [MS scan, 300 ≤ mass/charge (m/z) ≤ 2000; MS/MS scans were acquired for the five most abundant ions identified using low resolution for precursor isolation and 1.5-sec accumulation time with MS/MS data acquired in enhanced all-function and full-profile mode, 1.8 kV electrospray ionization voltage]. Data from the MS/MS scans were converted to peak lists (.mgf files) that were then compared against a mouse RefSeq protein sequence database (downloaded on October 7, 2009) using the Mascot (Matrix Science, Inc., London, UK) software platform (version 2.2.1). The mouse RefSeq protein sequence database consisted of 35,867 sequences. The search parameters allowed for two missed cleavages for trypsin, a fixed modification of +14 for methyl esters of aspartic acid, glutamic acid, and the peptide C terminus, and variable modifications of +80 for serine, threonine, and tyrosine phosphorylation, and +16 for methionine oxidation. Mass tolerance was set to 100 ppm for precursors and 200 ppm for fragment ions. All MS/MS spectra from putative phosphopeptide sequences with Mascot scores greater than or equal to 20 (P ≤ 10−2) were manually interrogated. Statistical assessment was based on the expectation value or E-value determined as the number of MS/MS spectrum matches in the RefSeq database characterized with equal or better Mascot score than the selected match that are expected to occur by chance alone. The peptide mixture in the flow through from the IMAC column was subjected to further LC/MS/MS analysis to identify phosphopeptides not retained by the IMAC column. MS data acquisition was performed on an Orbitrap (ThermoFisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) functioning in data-dependent mode (MS scan, 300 ≤ m/z ≤ 2000; MS/MS scans were acquired for the four most abundant ions identified using low resolution for precursor isolation in the linear trap, followed by C-trap-based MS/MS with data acquired in reduced profile mode). The acquisition data files were converted to .mgf files using software developed in the Marto laboratory, and a Mascot search was performed as above.

Structural and clustal analysis and Phosphosite kinase database search

The structure of the JH1 domain of JAK2 [2B7A (12)] was visualized using Cn3D produced by National Center for Biotechnology Information, Swiss Pdb viewer developed by Nicolas Guex (GlaxoSmithKline R&D, Research Triangle Park, NC), and PyMOL Molecular Graphics System (http://www.pymol. org). Surface accessibility was determined using PyMOL. Clustal alignments were performed using LaserGene, version 1.63 (DNASTAR, Madison, WI). The search for other kinases that contain phosphorylated tyrosines in positions homologous to Tyr 868, 966, and 972 was conducted using PhosphositePlus (www.phosphosite.org).

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant DK34171 (to C.C.-S.), the Michigan Economic Development Corporation for the Michigan Life Sciences Corridor Initiative (to J.A.S.), the University of Michigan Center for Structural Biology (to J.A.S.), and NIH DK56731 (to M.G.M.). S.R. was supported by predoctoral fellowships from the American Diabetes Association and the American Heart Association. Oligonucleotides were synthesized by the Biomedical Research Core Facility at the University of Michigan with support from the Michigan Diabetes Research and Training Center (P60-DK20572), the University of Michigan Multipurpose Arthritis Center (P60-AR20557), and the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center (NIH P30 CA46592). Synthesis of Stat5 peptide and cDNA sequencing were supported by the Peptide and Proteomics Core and Cellular and Molecular Biology Core, respectively, of the Michigan Diabetes Research and Training Center (P60-DK20572).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to declare.

First Published Online March 19, 2010

Abbreviations: 293T cells, Human embryonic kidney 293T cells; 2D, two-dimensional; ELR, chimeric Epo-leptin (LRb) receptor; Eph, ephrin receptor; Epo, erythropoietin; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; JAK2, Janus kinase 2; JH1, kinase domain of JAK2; IMAC, immobilized metal affinity chromatography enrichment; LC, liquid chromatography; MAST, microtubule-associated serine/threonine; MS, mass spectrometry; MS/MS, tandem MS; PLCγ1, phospholipase Cγ1; m/z, mass/charge; PTP1B, protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B; PY, phosphotyrosine; RON, recepteur d’origine nantais; RSK2, ribosomal S6 kinase 2; SH2, Src-homology 2; Stat, signal transducer and activator of transcription.

References

- Argetsinger LS, Carter-Su C 1996 Mechanism of signaling by growth hormone receptor. Physiol Rev 76:1089–1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit LS, Meyer DJ, Argetsinger LS, Schwartz J, Carter-Su C 1999 Molecular events in growth hormone-receptor interaction and signaling. In: Kostyo JL, ed. Handbook of physiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 445–480 [Google Scholar]

- Marrero MB, Schieffer B, Paxton WG, Heerdt L, Berk BC, Delafontaine P, Bernstein KE 1995 Direct stimulation of Jak/STAT pathway by the angiotensin II AT1 receptor. Nature 375:247–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier S, Duhamel F, Coulombe P, Popoff MR, Meloche S 2003 Rho family GTPases are required for activation of Jak/STAT signaling by G protein-coupled receptors. Mol Cell Biol 23:1316–1333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Witthuhn BA, Matsuda T, Kohlhuber F, Kerr IM, Ihle JN 1997 Activation of Jak2 catalytic activity requires phosphorylation of Y1007 in the kinase activation loop. Mol Cell Biol 17:2497–2501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argetsinger LS, Kouadio JL, Steen H, Stensballe A, Jensen ON, Carter-Su C 2004 Autophosphorylation of JAK2 on tyrosines 221 and 570 regulates its activity. Mol Cell Biol 24:4955–4967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda T, Feng J, Witthuhn BA, Sekine Y, Ihle JN 2004 Determination of the transphosphorylation sites of Jak2 kinase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 325:586–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funakoshi-Tago M, Pelletier S, Matsuda T, Parganas E, Ihle JN 2006 Receptor specific downregulation of cytokine signaling by autophosphorylation in the FERM domain of Jak2. EMBO J 25:4763–4772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feener EP, Rosario F, Dunn SL, Stancheva Z, Myers Jr MG 2004 Tyrosine phosphorylation of Jak2 in the JH2 domain inhibits cytokine signaling. Mol Cell Biol 24:4968–4978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurzer JH, Argetsinger LS, Zhou YJ, Kouadio JL, O'Shea JJ, Carter-Su C 2004 Tyrosine 813 is a site of JAK2 autophosphorylation critical for activation of JAK2 by SH2-Bβ. Mol Cell Biol 24:4557–4570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson SA, Koleva RI, Argetsinger LS, Carter-Su C, Marto JA, Feener EP, Myers Jr MG 2009 Regulation of Jak2 function by phosphorylation of Tyr317 and Tyr637 during cytokine signaling. Mol Cell Biol 29:3367–3378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucet IS, Fantino E, Styles M, Bamert R, Patel O, Broughton SE, Walter M, Burns CJ, Treutlein H, Wilks AF, Rossjohn J 2006 The structural basis of Janus kinase 2 inhibition by a potent and specific pan-Janus kinase inhibitor. Blood 107:176–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rikova K, Guo A, Zeng Q, Possemato A, Yu J, Haack H, Nardone J, Lee K, Reeves C, Li Y, Hu Y, Tan Z, Stokes M, Sullivan L, Mitchell J, Wetzel R, Macneill J, Ren JM, Yuan J, Bakalarski CE, Villen J, Kornhauser JM, Smith B, Li D, Zhou X, Gygi SP, Gu TL, Polakiewicz RD, Rush J, Comb MJ 2007 Global survey of phosphotyrosine signaling identifies oncogenic kinases in lung cancer. Cell 131:1190–1203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PhosphoSitePlus 2009 In: www.phosphosite.org: Third Millenium, Cell Signaling Technologies [Google Scholar]

- Argetsinger LS, Campbell GS, Yang X, Witthuhn BA, Silvennoinen O, Ihle JN, Carter-Su C 1993 Identification of JAK2 as a growth hormone receptor-associated tyrosine kinase. Cell 74:237–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rui L, Carter-Su C 1999 Identification of SH2-Bβ as a potent cytoplasmic activator of the tyrosine kinase Janus kinase 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:7172–7177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle WJ, van der Geer P, Hunter T 1991 Phosphopeptide mapping and phosphamino acid analysis by two-dimensional separation on thin-layer cellulose plates. Methods Enzymol 201:110–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JH, Kim HS, Kim SH, Yang YR, Bae YS, Chang JS, Kwon HM, Ryu SH, Suh PG 2006 Phospholipase Cγ1 negatively regulates growth hormone signalling by forming a ternary complex with Jak2 and protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B. Nat Cell Biol 8:1389–1397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaptein A, Paillard V, Saunders M 1996 Dominant negative stat3 mutant inhibits interleukin-6-induced Jak-STAT signal transduction. J Biol Chem 271:5961–5964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDoom I, Ma X, Kirabo A, Lee KY, Ostrov DA, Sayeski PP 2008 Identification of tyrosine 972 as a novel site of Jak2 tyrosine kinase phosphorylation and its role in Jak2 activation. Biochemistry 47:8326–8334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Ross JA, Frost JA, Kirken RA 2008 Phosphorylation of human Jak3 at tyrosines 904 and 939 positively regulates its activity. Mol Cell Biol 28:2271–2282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X, Ni S, Correll PH 2005 Uncoupling ligand-dependent and -independent mechanisms for mitogen-activated protein kinase activation by the murine Ron receptor tyrosine kinase. J Biol Chem 280:35098–35107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia F, Li J, Hickey GW, Tsurumi A, Larson K, Guo D, Yan SJ, Silver-Morse L, Li WX 2008 Raf activation is regulated by tyrosine 510 phosphorylation in Drosophila. PLoS Biol 6:e128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S, Dong S, Gu TL, Guo A, Cohen MS, Lonial S, Khoury HJ, Fabbro D, Gilliland DG, Bergsagel PL, Taunton J, Polakiewicz RD, Chen J 2007 FGFR3 activates RSK2 to mediate hematopoietic transformation through tyrosine phosphorylation of RSK2 and activation of the MEK/ERK pathway. Cancer Cell 12:201–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S, Dong S, Guo A, Ruan H, Lonial S, Khoury HJ, Gu TL, Chen J 2008 Epidermal growth factor stimulates RSK2 activation through activation of the MEK/ERK pathway and src-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of RSK2 at Tyr-529. J Biol Chem 283:4652–4657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux PP, Richards SA, Blenis J 2003 Phosphorylation of p90 ribosomal S6 kinase (RSK) regulates extracellular signal-regulated kinase docking and RSK activity. Mol Cell Biol 23:4796–4804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anjum R, Blenis J 2008 The RSK family of kinases: emerging roles in cellular signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 9:747–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalo MS, Pasquale EB 1999 Multiple in vivo tyrosine phosphorylation sites in EphB receptors. Biochemistry 38:14396–14408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalo MS, Yu HH, Pasquale EB 2001 In vivo tyrosine phosphorylation sites of activated ephrin-B1 and ephB2 from neural tissue. J Biol Chem 276:38940–38948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi M, Dikic I, Sorokin A, Burgess WH, Jaye M, Schlessinger J 1996 Identification of six novel autophosphorylation sites on fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 and elucidation of their importance in receptor activation and signal transduction. Mol Cell Biol 16:977–989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan G, Deng J, Wang T, Zhao C, Xu X, Wang P, Voltz JW, Edin ML, Xiao X, Chao L, Chao J, Zhang XA, Zeldin DC, Wang DW 2007 Tissue kallikrein reverses insulin resistance and attenuates nephropathy in diabetic rats by activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B and adenosine 5′-monophosphate-activated protein kinase signaling pathways. Endocrinology 148:2016–2026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baljuls A, Schmitz W, Mueller T, Zahedi RP, Sickmann A, Hekman M, Rapp UR 2008 Positive regulation of A-RAF by phosphorylation of isoform-specific hinge segment and identification of novel phosphorylation sites. J Biol Chem 283:27239–27254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang WB, Brantley-Sieders DM, Hwang Y, Ham AJ, Chen J 2008 Identification and functional analysis of phosphorylated tyrosine residues within EphA2 receptor tyrosine kinase. J Biol Chem 283:16017–16026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesner S, Wybenga-Groot LE, Warner N, Lin H, Pawson T, Forman-Kay JD, Sicheri F 2006 A change in conformational dynamics underlies the activation of Eph receptor tyrosine kinases. EMBO J 25:4686–4696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo A, Villén J, Kornhauser J, Lee KA, Stokes MP, Rikova K, Possemato A, Nardone J, Innocenti G, Wetzel R, Wang Y, MacNeill J, Mitchell J, Gygi SP, Rush J, Polakiewicz RD, Comb MJ 2008 Signaling networks assembled by oncogenic EGFR and c-Met. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:692–697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccimaro E, Hevko J, Blair IA 2006 Analysis of phosphorylation sites on focal adhesion kinase using nanospray liquid chromatography/multiple reaction monitoring mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 20:3681–3692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonysamy S, Hirst G, Park F, Sprengeler P, Stappenbeck F, Steensma R, Wilson M, Wong M 2009 Fragment-based discovery of JAK-2 inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 19:279–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ten Eyck LF, Taylor SS, Kornev AP 2008 Conserved spatial patterns across the protein kinase family. Biochim Biophys Acta 1784:238–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornev AP, Haste NM, Taylor SS, Eyck LF 2006 Surface comparison of active and inactive protein kinases identifies a conserved activation mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:17783–17788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupa A, Preethi G, Srinivasan N 2004 Structural modes of stabilization of permissive phosphorylation sites in protein kinases: distinct strategies in Ser/Thr and Tyr kinases. J Mol Biol 339:1025–1039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huse M, Kuriyan J 2002 The conformational plasticity of protein kinases. Cell 109:275–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamoon NM, Smith JK, Chatti K, Lee S, Kundrapu K, Duhé RJ 2007 Multiple cysteine residues are implicated in Janus kinase 2-mediated catalysis. Biochemistry 46:14810–14818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercher T, Wernig G, Moore SA, Levine RL, Gu TL, Fröhling S, Cullen D, Polakiewicz RD, Bernard OA, Boggon TJ, Lee BH, Gilliland DG 2006 JAK2 T875N is a novel activating mutation that results in myeloproliferative disease with features of megakaryoblastic leukemia in a murine bone marrow transplantation model. Blood 108:2770–2779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullighan CG, Zhang J, Harvey RC, Collins-Underwood JR, Schulman BA, Phillips LA, Tasian SK, Loh ML, Su X, Liu W, Devidas M, Atlas SR, Chen IM, Clifford RJ, Gerhard DS, Carroll WL, Reaman GH, Smith M, Downing JR, Hunger SP, Willman CL 2009 JAK mutations in high-risk childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:9414–9418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billestrup N, Møldrup A, Serup P, Mathews LS, Norstedt G, Nielsen JH 1990 Introduction of exogenous growth hormone receptors augments growth hormone-responsive insulin biosynthesis in rat insulinoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87:7210–7214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvennoinen O, Witthuhn BA, Quelle FW, Cleveland JL, Yi T, Ihle JN 1993 Structure of the murine JAK2 protein-tyrosine kinase and its role in interleukin 3 signal transduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90:8429–8433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloek C, Haq AK, Dunn SL, Lavery HJ, Banks AS, Myers Jr MG 2002 Regulation of Jak kinases by intracellular leptin receptor sequences. J Biol Chem 277:41547–41555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks AS, Davis SM, Bates SH, Myers Jr MG 2000 Activation of downstream signals by the long form of the leptin receptor. J Biol Chem 275:14563–14572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan KL, Haun RS, Watson SJ, Geahlen RL, Dixon JE 1990 Cloning and expression of a protein-tyrosine-phosphatase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87:1501–1505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rui L, Mathews LS, Hotta K, Gustafson TA, Carter-Su C 1997 Identification of SH2-Bβ as a substrate of the tyrosine kinase JAK2 involved in growth hormone signaling. Mol Cell Biol 17:6633–6644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo G, Yu-Lee L 1997 Transcriptional inhibition by Stat5. Differential activities at growth-related versus differentiation-specific promoters. J Biol Chem 272:26841–26849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Okayama H 1987 High-efficiency transformation of mammalian cells by plasmid DNA. Mol Cell Biol 7:2745–2752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stred SE, Stubbart JR, Argetsinger LS, Shafer JA, Carter-Su C 1990 Demonstration of growth hormone (GH) receptor-associated tyrosine kinase activity in GH-responsive cell types. Endocrinology 127:2506–2516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevchenko A, Wilm M, Vorm O, Mann M 1996 Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Anal Chem 68:850–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndassa YM, Orsi C, Marto JA, Chen S, Ross MM 2006 Improved immobilized metal affinity chromatography for large-scale phosphoproteomics applications. J Proteome Res 5:2789–2799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard SR 1997 Crystal structure of the activated insulin receptor tyrosine kinase in complex with peptide substrate and ATP analog. EMBO J 16:5572–5581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]