Abstract

Glucocorticoids, major end effectors of the stress response, play an essential role in the homeostasis of the central nervous system (CNS) and contribute to memory consolidation and emotional control through their intracellular receptors, the glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors. Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (CDK5), on the other hand, plays important roles in the morphogenesis and functions of the central nervous system, and its aberrant activation has been associated with development of neurodegenerative disorders. We previously reported that CDK5 phosphorylated the glucocorticoid receptor and modulated its transcriptional activity. Here we found that CDK5 also regulated mineralocorticoid receptor-induced transcriptional activity by phosphorylating multiple serine and threonine residues located in its N-terminal domain through physical interaction. Aldosterone and dexamethasone, respectively, increased and suppressed mRNA/protein expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in rat cortical neuronal cells, whereas the endogenous glucocorticoid corticosterone showed a biphasic effect. CDK5 enhanced the effect of aldosterone and dexamethasone on BDNF expression. Because this neurotrophic factor plays critical roles in neuronal viability, synaptic plasticity, consolidation of memory, and emotional changes, we suggest that aberrant activation of CDK5 might influence these functions through corticosteroid receptors/BDNF.

CDK5, an important kinase for brain physiology and pathophysiology, phosphorylates the mineralocorticoid receptor and modulates the transcriptional activity of this receptor in neurons.

Glucocorticoids, steroid hormones secreted from the adrenal cortices, play essential roles in the homeostasis of the central nervous system (CNS) (1,2). Indeed, these hormones regulate cognition, memory and mood, and influence the anatomic structure of the brain and differentiation/survival/apoptosis of neurons (3,4). Most known effects of glucocorticoids in CNS are mediated by the glucocorticoid (GR) and mineralocorticoid (MR) receptors, both of which belong to the nuclear receptor superfamily, functioning as hormone-dependent transcription factors (5). After binding to agonist ligands, the cytoplasmic GR and MR dissociate from several heat shock proteins with which they are complexed, enter into the nucleus in an energy-dependent manner, and ultimately modulate the transcriptional activity of their responsive genes (6). Inside the nucleus, these receptors bind their cognate DNA-binding sequences, the glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid response elements located in the regulatory regions of glucocorticoid- and mineralocorticoid-responsive genes (5). Promoter-bound GR and MR initiate transcription of downstream coding sequences by associating with numerous coactivator complexes and chromatin-remodeling factors, as well as the RNA polymerase II and its ancillary factors, through their transactivation domains, located in their N-terminal (NTD) and ligand-binding (LBD) domains, respectively (5,6,7,8).

GR and MR are evolutionarily close, having diverged from each other from an ancestral corticoid receptor approximately 350 million years ago (9,10). Thus, these receptors have major homologies at their DNA-binding domain (DBD) (94%) and LBD (57%), and share many responsive genes, as well as ligands with different binding affinities (11,12). Interestingly, the MR binds the endogenous glucocorticoid cortisol or corticosterone with higher affinity than the GR in the absence of the cortisol-inactivating enzyme 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 (11βHSD2) (11). GR and MR, however, regardless of the presence or absence of 11βHSD2, are stimulated by their specific ligands, e.g. dexamethasone and aldosterone, respectively (11). In contrast to the DBDs and LBDs of the two receptors, their NTDs have much less sequence homology (<15%), thus adding specificity to the transcriptional effects of the two receptors by utilizing distinct activation domains of their NTDs (12). These pieces of evidence indicate that in some areas of the brain, in the absence of 11βHSD2, the MR acts as a second glucocorticoid receptor regulating the expression of various target genes with different transcriptional potencies from the GR in response to cortisol/corticosterone, or in association with its specific ligand aldosterone.

Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (CDK5), a member of the CDK-dependent kinase family of serine/threonine kinases, is essential for neuronal morphogenesis, function and survival, by regulating numerous important functions, such as synaptic transmission and plasticity, neuronal migration, cell adhesion, axon guidance, membrane transport, and actin dynamics (13,14). CDK5 is expressed ubiquitously in many tissues; however, its activity is restricted primarily to the nervous system due to neuron-specific expression of its activator molecules p35 and p39 (15,16). In addition to these physiological roles of CDK5, recent evidence suggests that aberrant CDK5 activation caused by proteolytic conversion of p35 to p25 plays a role in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (17,18,19,20,21,22). In these disorders, cellular stress-mediated calpain-directed proteolysis of p35 deprives the membrane-associated p35 of an N-terminal myristoylated membrane tether, releasing p25 into the cytoplasm where it hyperactivates the kinase activity of CDK5 (23,24).

We previously reported that CDK5 modulates the transcriptional activity of the GR by interacting with its LBD and phosphorylating multiple serine residues located in its NTD transactivation domain (25). In this manuscript, we examined the effect of CDK5 on the MR and found that this enzyme also interacted with this receptor, phosphorylated the serine and threonine residues located in its NTD, and modulated transcriptional activity similarly to the GR. We also found that both GR and MR modulated expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and CDK5 further altered their effects on this pivotal CNS molecule. Our results thus suggest that CDK5 might influence formation/alteration of memory and mood by affecting differential effects of glucocorticoids on BDNF expression.

Results

CDK5 modulates MR-induced transcriptional activity in a kinase activity-dependent fashion

We examined the effect of CDK5/p35 and CDK5/p25 on MR-induced transcriptional activity of the glucocorticoid- and mineralocorticoid-responsive mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) promoter in GR- and MR-deficient HCT116 cells upon transfection with MR-expressing plasmids together with those of CDK5 and p35/p25 (Fig. 1A). CDK5 and p35 or p25 suppressed, in a dose-dependent manner, aldosterone-induced MR transcriptional activity on the promoter, whereas the dominant-negative mutant CDK5D144N, defective in the kinase activity, failed to do so. The suppressive effect of CDK5 on MR-induced transactivation of the MMTV promoter was stronger when it was coexpressed with p25 than with p35, consistent with previous report that p25 is much stronger in the activation of CDK5 kinase activity than p35 (14,26). Expression levels of MR in the presence of aldosterone were similar throughout the experiment (Fig. 1A, bottom panel), whereas CDK5 did not affect aldosterone-induced nuclear translocation of MR (Fig. 1B). These results indicate that CDK5 modulates MR-induced transcriptional activity in a kinase activity-dependent fashion, similarly to its effect on the GR.

Figure 1.

CDK5 suppresses MR-induced transcriptional activity. A, CDK5 suppresses MR-induced transcriptional activity in a kinase activity-dependent fashion. HCT116 cells were transfected with plasmids expressing the molecules indicated together with MMTV-Luc and pGL4.73-RLuc. Bars in the top panel represent mean ± se values of firefly luciferase activity normalized for Renilla luciferase activity in the presence and absence of 10−8m aldosterone (Aldo). Expression levels of MR and β-actin (bottom panel, top and bottom gel, respectively) in the Aldo-treated samples used in the top panel were examined with Western blots (bottom panel). *, P < 0.01; n.s., not significant between the two conditions indicated. B, CDK5 does not influence Aldo-induced nuclear accumulation of MR. HCT116 cells were transfected with indicated protein-expressing plasmids and were treated with 10−8m Aldo for 1 h. Total and nuclear MR were examined, respectively, in whole homogenates and nuclear extracts of these cells in Western blots by using anti-MR antibody. RLU, relative light units; WT, wild type.

CDK5 interacts with LBD of the MR in vitro and is associated with this receptor in a ligand-dependent fashion in vivo

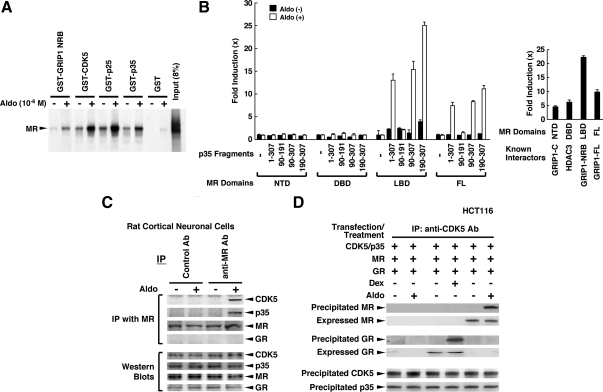

We tested the interaction of CDK5, p25, and p35 with MR in glutathione-S-transferase (GST) pull-down assays (Fig. 2A). As expected, these molecules interacted with MR in an aldosterone-dependent fashion where p25 showed the strongest interaction. We also examined the interaction of p35 and MR in a yeast two-hybrid assay and found that a portion of p35 enclosed in amino acids 190-307 was associated with LBD in an aldosterone-dependent fashion, but not with its DBD or NTD (Fig. 2B, left panels). The full-length MR or its domains employed in the yeast two-hybrid assay were associated with full-length GR-interacting protein 1 (GRIP1), its nuclear receptor-binding domain (NRB) or C-terminal domains, or histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3) (Fig. 2B, right panel). Thus, these MR domains expressed in yeast were functional, as they interacted, respectively, with the GRIP1 and HDAC3, which are coregulator molecules already known to interact with these domains of steroid hormone receptors (7,27). CDK5 and p35 were also associated with MR in an aldosterone-dependent fashion in a coimmunoprecipitation assay (Fig. 2C). Importantly, the CDK5/p35 and MR protein complex formed in response to aldosterone did not include GR in rat primary cortical neuronal cells (Fig. 2C, fourth top gel), although MR has been reported to form a heterodimer with GR (28,29). Sole expression of MR or GR in HCT116 cells, which are devoid of both of these receptors, also supported fully interaction of these receptors with CDK5/p35 (Fig. 2D). Thus, the MR indeed forms a ternary complex with CDK5/p35 independently of the GR. Taken together, these results suggest that CDK5 suppresses MR-induced transcriptional activity by physically interacting with MR LBD via p35 or p25.

Figure 2.

CDK5 and MR interact with each other in vitro and in vivo. A, MR interacts with GST-fused CDK5, p35, and p25 in a ligand-dependent fashion in a GST pull-down assay. In vitro translated and 35S-labeled MR was incubated with bacterially produced and purified GST-fused proteins on GST beads in the presence and absence of 10−6m aldosterone (Aldo). Radiolabeled MR associated with GST-fusion proteins was visualized in SDS-PAGE gels; 8% of MR used for the reaction was loaded as input. B, MR interacts with p35 through its LBD in an Aldo-dependent fashion in a yeast two-hybrid assay. EGY48 yeast cells were transformed with p8OP-LacZ, pB42AD-p35 (1-307) -p35 (90-307), -p35 (1-191) -p35 (190-307), GRIP1-C, GRIP1-NRB, GRIP1-FL, or HDAC3, and pLexA-MR (1-984), -MR (1-602), -MR (602-670), or -MR (668-984) and incubated with 10−6m Aldo. The results of the interaction between MR domains and p35 fragments were shown in the left panel. The interaction of these MR domains in the presence of 10−8m Aldo with molecules already known to bind them is shown in the right panel to demonstrate the integrity of the expressed MR-related proteins. Basal β-galactosidase activities of MR NTD, DBD, LBD, and FL in the absence of their interactors are 33,009 ± 2147, 212 ± 9, 44,349 ± 983, and 69,662 ± 2862 (mean ± se, unit/OD600nm), respectively. Bars represent the mean ± se values of fold activation compared with baseline (left panel, the value obtained in the presence of pLexA, pB42AD-p35, and p8OP-LacZ and in the absence of aldosterone; right panel, the value obtained in the absence of interactors). C, Carboxyl terminal. Panel C, MR is associated with CDK5 and p35 in a ligand-dependent fashion in rat primary cortical neuronal cells. Rat primary cortical neuronal cells were incubated in the presence and absence of 10−8m Aldo for 1 h, and coimmunoprecipitation was carried out by using the antibodies (Ab) indicated. The results of coimmunoprecipitation are shown in the top four gels, whereas expression levels of CDK5, p35, MR, and GR are shown in Western blots in the bottom four gels by loading 10% of cell lysates used for the coimmunoprecipitation reactions. D, MR and GR, respectively, form a protein complex with CDK5 and p35 in a ligand-dependent fashion in HCT116 cells. HCT116 cells were transfected with the indicated protein-expressing plasmids and were treated with 10−8m Aldo or 10−6m dexamethasone (Dex) for 1 h. Coimmunoprecipitation was performed by using anti-CDK5 antibody, and precipitated MR, GR, CDK5, and p35 were examined (third top and bottom two gels). Expressed MR and GR were also shown in Western blots in second and fourth top gels by loading 10% of cell lysates used for the coimmunoprecipitation reactions. IP, Immunoprecipitation.

CDK5 phosphorylates the MR in vitro and in vivo and modulates MR-induced transcriptional activity though phosphorylation of this receptor

Because CDK5 suppressed MR-induced transcriptional activity in its kinase activity-dependent fashion, we examined phosphorylation of MR by CDK5 with phospho-mass spectrometry analysis. A representative mass spectrometry result for the phosphorylation of GST-fused human (h)MR (1-602) by CDK5 is shown in Fig. 3A, whereas amino acid residues of GST-fused hGR (1-490) and hMR (1-602) phosphorylated by CDK5 in vitro are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. In this analysis, we found that CDK5 phosphorylated serines 45 and 203 of hGR (1-490), which we identified as the residues phosphorylated by this kinase in our previous report (25), suggesting that the in vitro phosphorylation system correctly identified phosphorylated residues. In addition to these residues, we also found that serines 25 and 267 of the GR, which were not recognized in the previous report (25), were also phosphorylated by CDK5. Using the same method, we employed a GST-fused hMR (1-602) that contained NTD of this receptor and found that serine 250 and threonine 159 of the MR fragment were phosphorylated by CDK5. Indeed, these residues are in the consensus sequences of CDK5 phosphorylation sites (14,30,31,32). Therefore, we introduced multiple mutations replacing these serine and threonine into alanine and examined the effect of CDK5/p35 on their transcriptional activity on the MMTV promoter in HCT116 cells. Because serine 128 is also in the perfect motif of CDK5 phosphorylation sites, we mutated this residue to alanine as well. Single replacement of serines 128 and 250 or threonine 159 mildly reduced the suppressive effect of CDK5/p25 on these mutant MRs, whereas double mutations of these amino acid residues strongly attenuated the negative effect of CDK5 (Fig. 3B, top panel). Replacement of all three amino acids by alanine completely abolished CDK5 effect on the mutant MR-induced transcriptional activity. We also obtained similar results by using p35 instead of p25 in combination with CDK5 (data not shown). Mutant MRs employed in this experiment accumulated in the nucleus in similar amounts in response to aldosterone (Fig. 3B, bottom panel). These results indicate that serines 128 and 250 and threonine 159 of the MR play critical roles in the CDK5/p25-induced suppression of MR transcriptional activity.

Figure 3.

CDK5 regulates MR-induced transcriptional activity by phosphorylating the latter’s two serine (128 and 250) and one threonine (159) residues. A, A representative analysis of the phospho-MS of GST-hMR (1-602) phosphorylated by CDK5/p35. The peptide sequence analyzed in this panel is shown in the upper left corner. The serine phosphorylated by CDK5 is indicated with asterisk and underline. B, Serines 128 and 250 and threonine 159 are all necessary for CDK5 to suppress MR-induced transcriptional activity in HCT116 cells. Top panel, HCT116 cells were transfected with plasmids expressing the indicated MR mutants and CDK5/p35 together with MMTV-Luc and pGL4.73-RLuc. Bars represent mean ± se values of firefly luciferase activity normalized by Renilla luciferase activity in the presence and absence of 10−8m aldosterone (Aldo). *, P < 0.01, n.s., not significant between the two conditions indicated. Bottom panel, HCT116 cells were transfected with plasmids expressing the indicated MR mutants, and levels of MR proteins accumulated in the nucleus after treatment with 10−8m Aldo (top gel) and the control Oct1 (bottom gel) were examined in Western blots using their specific antibodies in the nuclear extracts obtained from these cells. C, CDK5 phosphorylates serines 128 and 250 and threonine 159 in an Aldo-dependent fashion in HCT116 cells. HCT116 cells were transfected with the indicated MR mutant-expressing plasmids together with CDK5- and p25-expressing plasmids and were treated with 10−8m Aldo for 1 h. MRs were immunoprecipitated by anti-MR antibody, and phosphorylated serine (top panel) or threonine (bottom panel) residues of MR by CDK5 were examined in Western blots by using antibody specific to phosphoserine or -threonine residues. D, CDK5 phosphorylates serine and threonine residues in an Aldo-dependent fashion in rat primary cortical neuronal cells. Rat primary cortical neuronal cells were treated with 10−8m Aldo and/or 20 μm roscovitine for 1 h. MRs were immunoprecipitated with anti-MR antibody, and serine- and threonine-phosphorylated MRs (top and bottom gel, respectively) were examined in Western blots by using antibody specific for phosphoserine or -threonine residues. WT, Wild type.

Table 1.

Tryptic peptides of GST-hGR(1-490) phosphorylated by CDK5

| Peptide sequences that contain phosphorylated residues | Phosphorylated residue |

|---|---|

| SASS PSLAVASQSDSKQ | S25 |

| KVSASS PSLAVASQSDSKQ | S45 |

| FSSGS PGKETNESPWRS | S203 |

| KIKDNGDLVLSS PSN | S267 |

and bold letters indicate the amino acid residues phosphorylated by CDK5.

Table 2.

Tryptic peptides of GST-hMR(1-602) phosphorylated by CDK5

| Peptide sequences that contain phosphorylated residues | Phosphorylated residue |

|---|---|

| RSHS PAHASNVGSPLSSPLSSMKS | S250 |

| KGNGHRPSTLSCVNT PLRS | T159 |

and bold letters indicate the amino acid residues phosphorylated by CDK5.

We next examined CDK5-induced phosphorylation of these serine and threonine residues by coprecipitating MR with anti-MR antibody and by probing with an antibody specific for phosphorylated serine or threonine residues. CDK5-induced phosphorylations of the MR were dependent on the presence of serines 128 and 250 and threonine 159 in HCT116 cells transfected with wild-type MR or MR mutants with nonphosphorylating (alanine) amino acid residues (Fig. 3C). The CDK5 inhibitor roscovitine (25,33,34,35) almost completely abolished aldosterone-dependent phosphorylation of MR in rat primary cortical neuronal cells (Fig. 3D). These results suggest that CDK5 phosphorylates serines 128 and 250 and threonine 159 of the MR in an aldosterone-dependent fashion at the cellular level. Because these serines and threonine residues are located in the transactivation domain of the MR NTD (36), it appears that phosphorylation by CDK5 modulates MR transcriptional activity by affecting the interaction of cofactors to this MR activation domain similar to the GR (25).

We next examined the biological consequence of CDK5-mediated modulation of MR-induced transcriptional activity by testing its inhibitor roscovitine on rat primary cortical neuronal cells treated with aldosterone or dexamethasone. We focused on the BDNF, because this factor plays essential roles in the long-term survival/differentiation of neurons, as well as their cellular architecture and synaptic plasticity, and thus, is crucial for the long-term potentiation and memory formation (37), which MR and GR strongly influence (2). In neurons, the effects of BDNF are mediated by two cell surface receptors, the receptor tyrosine kinase B (TrkB) and the low-affinity p75 neurotropin receptor (p75NTR) (37). In these cells, aldosterone induced BDNF mRNA expression by 3-fold after 12 h of exposure, whereas dexamethasone suppressed it by up to 50% in a similar time course (Fig. 4A). During the treatment, mRNA expression of TrkB, CDK5, and p35 was not altered, whereas that of the p75NTR was mildly stimulated by these steroids. Eplerenone and RU 486, receptor antagonists specific to MR and GR, respectively, completely blocked the effect of aldosterone or dexamethasone on BDNF mRNA expression in these cells (Fig. 4B), indicating that alteration of this mRNA expression by these steroids are mediated by the MR and GR, respectively. We also examined the effect of these hormones on the secretion of BDNF from these cells and found that aldosterone and dexamethasone, respectively, increased and decreased concentrations of BDNF in the medium, whereas eplerenone and RU 486 abolished their effects (Fig. 4C). In the titration analyses, aldosterone increased, whereas dexamethasone suppressed BDNF secretion into the medium of rat primary cortical neuronal cells (Fig. 4D). Corticosterone, an endogenous glucocorticoid that can activate both GR and MR, demonstrated a biphasic effect on the BDNF secretion in the medium, stimulating it at lower concentrations and suppressing it at higher concentrations. Eplerenone abolished the positive effect of corticosterone on BDNF secretion observed at its lower concentrations, whereas RU 486 eliminated the negative effect of this steroid seen at its higher concentrations (Fig. 4D), suggesting that corticosterone has a biphasic effect on BDNF secretion by activating both the MR and GR.

Figure 4.

Aldosterone (Aldo) stimulates, whereas dexamethasone (Dex) suppresses, BDNF production of rat primary cortical neuronal cells. A, Aldo stimulates BDNF mRNA expression in rat primary cortical neuronal cells, whereas Dex suppresses it. Rat primary cortical neuronal cells were incubated in the presence of 10−8m Aldo or 10−6m Dex for 0, 1, 4, 10, or 24 h, and mRNA expressions of BDNF, TrkB, p75NTR, CDK5, and p35 were determined with SYBR Green real-time PCR. Circles and bars represent mean ± se values of mRNA expression of the molecules indicated corrected for that of RPLP0 in the presence of aldosterone (open circles) or dexamethasone (solid circles). B, Specific receptor inhibitors eplerenone and RU 486, respectively, abolish Aldo- and Dex-induced changes in BDNF mRNA expression in rat primary cortical neuronal cells. Rat primary cortical neuronal cells were incubated with the steroids indicated, and BDNF mRNA expression was measured with SYBR Green real-time PCR. Bars represent mean ± se values of mRNA expression of BDNF corrected for that of RPLP0. *, P < 0.01, compared between the two conditions indicated. C, Aldo increases, whereas Dex reduces, BDNF secretion into the culture medium of rat primary cortical neuronal cells. Rat primary cortical neuronal cells were incubated in the presence of 10−8m Aldo, 10−6m Dex, 10−6m eplerenone, and/or 10−5m RU 486 for the indicated time periods, and the concentrations of BDNF in medium were determined with a specific ELISA. Circles and bars represent mean ± se values of BDNF concentrations in the presence of Aldo (open circles) or dexamethasone (solid circles). *, P < 0.01, compared with the values in the presence and absence of eplerenone or RU 486 in the presence of same concentration of Aldo or Dex. D, Aldo, corticosterone (Cortico), and Dex differentially regulate BDNF secretion in rat primary cortical neuronal cells. Rat primary cortical neuronal cells were incubated in the presence of indicated concentrations of Aldo, Cortico, or Dex for 24 h, and the concentrations of BDNF in medium were determined with a specific ELISA. Circles/squares and bars represent mean ± se values of BDNF concentrations in the presence of Aldo (open circles), Cortico (open squares), or Dex (solid circles). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01, compared with the values in the absence of steroids. E, Eplerenone and RU 486 differentially regulate Cortico-induced BDNF secretion in rat primary cortical neuronal cells. Rat primary cortical neuronal cells were incubated with the indicated concentrations of Cortico in the presence or absence of 10−6m eplerenone or 10−5m RU 486 for 24 h. Concentrations of BDNF in medium were determined with a specific ELISA. Squares/circles and bars represent mean ± se values of BDNF concentrations in the absence (open squares) or presence of eplerenone (solid circles) or RU 486 (solid circles). *, P < 0.05, compared with the values in the absence of eplerenone or RU 486.

We then examined the effects of roscovitine on the aldosterone- or dexamethasone-mediated alteration of BDNF mRNA expression in the presence of aldosterone or dexamethasone at 0-, 1-, 4-, 10-, and 24-h time points in these cells (Fig. 5). Roscovitine, respectively, attenuated aldosterone- and dexamethasone-induced stimulation and suppression of BDNF mRNA expression (Fig. 5A). Roscovitine suppressed mRNA expression of p75NTR at baseline, whereas it weakly affected their mRNA expression in the presence of aldosterone or dexamethasone. Roscovitine did not alter TrkB mRNA expression either in the presence or absence of these hormones. At the level of protein expression, roscovitine inhibited aldosterone- or dexamethasone-induced increase/ reduction of the BDNF level in the medium, consistent with our results examining its mRNA expression (Fig. 5B). To confirm these results obtained with roscovitine, we transfected rat primary cortical neuronal cells with CDK5 small interfering RNA (siRNA), and examined their BDNF mRNA expression. As expected, knockdown of CDK5 influenced the effects of dexamethasone and aldosterone on BDNF mRNA expression in a similar fashion as roscovitine, whereas knockdown of the cAMP response element-binding protein 1 (CREB1), which also plays an important role in the regulation of BDNF expression (38), had no such effect (Fig. 5C), further indicating that our results obtained with roscovitine are caused through the inhibition of CDK5 by this compound.

Figure 5.

CDK5 inhibitor roscovitine (Rosco) suppresses the stimulatory effect of aldosterone (Aldo) and the inhibitory effect of dexamethasone (Dex) on the BDNF production. A, Rosco suppresses the stimulatory effect of Aldo and the inhibitory effect of Dex on the mRNA expression of BDNF, whereas it weakly suppressed mRNA expression of p75NTR, but not TrkB, in rat primary cortical neuronal cells. Rat primary cortical neuronal cells were incubated with 10−8m Aldo or 10−6m Dex in the presence or absence of 20 μm Rosco for 9 h. mRNA expressions of the molecules indicated were determined by SYBR Green real-time PCR. Bars represent mean ± se values of mRNA expressions of the molecules indicated normalized for that of RPLP0 in the presence and absence of Rosco. *, P < 0.01; n.s., not significant compared with the values indicated or to the value obtained in the absence of steroids and roscovitine. B, Rosco suppresses the stimulatory effect of Aldo and the inhibitory effect of Dex on the BDNF secretion of rat primary cortical neuronal cells. Rat primary cortical neuronal cells were incubated with 10−8m Aldo or 10−6m Dex in the presence or absence of 20 μm Rosco for 24 h. Concentrations of BDNF in the culture media of these cells were determined with a specific ELISA. Bars represent mean ± se values of BDNF concentrations in the presence and absence of Rosco. *, P < 0.01; n.s., not significant compared with the values indicated or to the value obtained in the absence of steroids and Rosco. C, Knockdown of CDK5, but not of CREB1, suppresses the stimulatory effect of Aldo and the inhibitory effect of Dex on the BDNF secretion of rat primary cortical neuronal cells. Rat primary cortical neuronal cells were transfected with control, CDK5, or CREB1 siRNA and were incubated with 10−8m Aldo or 10−6m Dex for 24 h. Concentrations of BDNF in the culture media of these cells were determined using a specific ELISA. Bars represent mean ± se values of BDNF concentrations in the presence of indicated siRNA. *, P < 0.01; n.s., not significant compared with the value obtained in the presence of control siRNA and in the absence of steroids.

Discussion

We demonstrated that CDK5 interacted with MR at its LBD through its activator p35 in a ligand-dependent fashion, phosphorylated this receptor at serines 128 and 250 and threonine 159, and modulated its transcriptional activity. These serine and threonine residues are located in the activation domain of the MR NTD (36). Because the modes of CDK5 for modulating the MR activity are similar to those of GR, it is likely that CDK5 positively and negatively alters MR-induced transcriptional activity by differentially affecting interaction of cofactors to this activation domain similarly to its effect on the GR. It is also likely that this effect of CDK5 is promoter specific and, possibly, tissue specific (25). We examined the potential biological relevance of CDK5-mediated regulation of MR- and GR-induced transcriptional activity by focusing on the neurotropin BDNF and found that aldosterone/MR and dexamethasone/GR, respectively, increased/suppressed the expression of BDNF in the rat primary cortical neuronal cells. Importantly, the endogenous glucocorticoid corticosterone, which activates both MR and GR (11), demonstrated a biphasic effect on the BDNF expression in rat primary cortical neuronal cells, stimulating it in lower concentrations relevant to its physiological circulating levels, whereas suppressing it in higher concentrations encountered under stress or with use of exogenous glucocorticoids (11). The CDK5 inhibitor roscovitine suppressed their effects, suggesting that CDK5 further enhanced the positive and negative effects of MR and GR on the expression of BDNF, respectively.

GR and MR mediate the numerous CNS effects of endogenous glucocorticoids, cortisol and corticosterone, in humans and rodents, respectively (2,11). Cortisol or corticosterone circulates at 2 log units higher concentrations than the natural mineralocorticoid aldosterone, whereas the MR has higher affinity to cortisol than the GR (11). Thus, basal physiological levels of circulating cortisol fully activate the MR, whereas the GR is affected primarily by elevated levels of cortisol or corticosterone during the circadian surge or during stress. GR is expressed both in neurons and in glial cells of the entire CNS, whereas MR is restrictively expressed in neurons of the hippocampus and amygdala, which do not have the glucocorticoid-inactivating 11βHSD2 enzyme (2). In the hippocampus, which is a brain region essential for learning and memory, and in the control of emotion and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, these two receptors mediate different and often opposite effects of cortisol/corticosterone (2). Indeed, the MR mediates enhancement of neuronal excitability, stabilization of synaptic transmission, and stimulation of long-term potentiation (LTP) in CA1 hippocampal cells, whereas simultaneous occupation of both MR and GR results in attenuation of the excitability and disruption of LTP in these neurons (39,40). Previous publications also indicate that MR activation is protective to granular cell neurons of the hippocampus, whereas persistent GR stimulation is toxic to these cells (41,42). Thus, both glucocorticoid excess (via the GR) and deficiency (via the MR) cause apoptosis of these cells, leading to memory deficits and alterations in mood and cognition (41). These observations are supported by several animal studies employing genetic modifications of GR/MR expression in mice (42,43,44,45,46).

BDNF is a neurotropin, essential for neuronal viability, growth and differentiation, and synaptic efficacy and plasticity (37,47). It stimulates synaptic transmission in hippocampal neurons (48,49), whereas BDNF-knockout mice display attenuated LTP in the CA1 region of the hippocampus (50). This neurotrophic factor also decreases the vulnerability to glucose deprivation and reduces glutamate neurotoxicity in cultured hippocampal neurons (51). Thus, changes in BDNF levels in the hippocampus are associated with pathological conditions, such as Alzheimer’s disease and depression (52,53).

We found that aldosterone stimulated BDNF mRNA and secretion in rat primary cortical neuronal cells, whereas dexamethasone suppressed it. These effects were mediated by their receptors GR and MR, respectively. We also found that the endogenous glucocorticoid corticosterone, which activates both GR and MR, demonstrated a biphasic effect on BDNF secretion from rat primary cortical neuronal cells, consistent with a previous report indicating that this steroid regulated BDNF expression in the hippocampus of rats in vivo (54). Taken together, these pieces of evidence indicate that these steroids might influence neuronal survival, memory formation, and mood through altering BDNF expression in the hippocampal neurons, whereas the endogenous glucocorticoids may have a biphasic effect on BDNF expression, stimulating it at physiological concentrations, whereas suppressing at pharmacological or stress-related concentrations. Furthermore, our results suggest that CDK5 may alter BDNF expression in the hippocampus by changing the transcriptional activity of these receptors. Because aberrant activation of CDK5 is associated with several neurodegenerative disorders including Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, where BDNF plays a role (55), it is possible that this kinase plays a role in the pathogenesis of these disorders by modulating BDNF expression in the hippocampus through alteration of GR- and/or MR-induced transcriptional activity on the BDNF gene.

Our results are based largely on the molecular interactions between CDK5 and MR/GR and the transcriptional regulation of the latter by the former at the cellular level in vitro. On the basis of these results, we propose that further studies should be considered in vivo, by studying brain functions, such as memory, mood, and behavior or neuropathological changes in the CNS with aging. Because the CNS GR/MR-BDNF pathways in the hippocampus participate in the regulation of mood (53,55), we hypothesize that alterations in CDK5 activity in this and other brain areas might contribute to the pathogenesis of mood disorders, such as major depression, bipolar disorder, and anxiety disorder, by positively or negatively regulating the activity of endogenous glucocorticoid actions in the brain (6).

Materials and Methods

Plasmids

pcDNAI/Amp-hMR, which expresses the hMR, was a kind gift from Dr. N. Warriar (Centre 71 Recherche, Hôtel-Dieu Québec and Laval University, Québec, Canada). pcDNAI/Amp-hMR S128A, T159A, S250A, S128/S250A, T159/S250A, and S128/T159/S250A, which express the mutant MRs with indicated amino acid replacement, were created by PCR-assisted mutagenesis reactions (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). pGEX-2T-hMR (1-602) was a kind gift from Dr. Marc Lombès (University of Paris, Le Kremlin-Bicêtre, France). pGEX-4T3-GR (1-490) and pGEX-4T3-GRIP1-NRB, which, respectively, express GST-fused human GR fragment (1-490) and the NRB (amino acids 599-774) of the mouse GRIP1, were previously reported (56). pcDNA3-CDK5, -CDK5D144N, -p35, and -p25, and pGEX-4T3-CDK5, -p35, and -p25 are also previously reported (25). pMMTV-luc and pGL4.73-RLuc, which, respectively, express firefly luciferase under the control of glucocorticoid-responsive, four glucorticoid response element-containing mouse mammary tumor virus promoter and the Renilla luciferase under the control of the Simian virus 40 promoter, were donated from Dr. G. L. Hager (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD) and purchased from Promega Corp. (Madison, WI), respectively. pcDNA3 and pGEX-4T3 were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) and GE Healthcare Bioscience Corp. (Piscataway, NJ), respectively. pLexA-MR (1-984), -MR (1-602), -MR (602-670), or -MR (668-984), which express full-length (FL), NTD, DBD, and LBD of the human MR fused to the LexA-activation domain, were constructed by subcloning the corresponding MR cDNA sequences into pLexA (ClONTECH Laboratories, Inc., Palo Alto, CA). pB42AD-p35 (1-307), -p35 (90-307), -p35 (1-191), and -p35 (190-307) and p8OP-LacZ were described previously (25). pLexA-GRIP1-C, -GRIP1-NRB, and -GRIP1-FL and -HDAC3 were produced by subcloning, respectively, the cDNA fragments encoding amino acids 594-774, 740-1217, and 1-1462 of the mouse GRIP1 (56), and the human HDAC3 (57) into pLexA.

Cell cultures and transfections

MR-deficient human colon carcinoma HCT116 cells were maintained in McCoy’s 5A medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml of penicillin, and 100 μg/ml of streptomycin, respectively. HCT116 cells were transfected with the indicated amounts of CDK5- and/or p35-related plasmids, 0.2 μg/well of MR-related plasmids together with 1.5 μg/well of pMMTV-Luc and 0.5 μg/well of pGL4.73-RLuc. Primary cultures of rat cortical neuronal cells were prepared from embryonic d 18 (E18) rat fetuses and were cultured in the Neurobasal medium and B27 supplement (Invitrogen) containing 100 U/ml of penicillin, 100 μg/ml of streptomycin, and 2 mm glutamine, as described previously (25). After 7 d of culture, these cells were treated with 10−8m of aldosterone, 10−6m of eplerenone, 10−6m of dexamethasone, 10−5m of RU 486 and/or 20 μm of roscovitine (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), and were used for the coimmunoprecipitation or chromatin-immunoprecipitation assays or purification of total RNA for mRNA quantification. Eplerenone was a kind gift from Pfizer, Inc. (Groton, CT). Rat cortical neuronal cells were also transfected with CDK5, CREB1, or control siRNAs (Applied Biosystems/Ambion, Austin, TX) with Lipofectamin 2000 (Invitrogen) and were treated with 10−8m of aldosterone or 10−6m of dexamethasone.

GST pull-down assay

35S-labeled human MR was generated by in vitro translation using pcDNAI/Amp-hMR, and was tested for interaction with GST-CDK5, -p35, or -p25, immobilized on glutathione-sepharose beads in the presence or absence of 10−6m of aldosterone, as previously described (25). After vigorous washing with the buffer, proteins were eluted and separated on 8% SDS-PAGE gels. Gels were fixed, treated with Enlighting (NEN Life Science Products, Inc., Boston, MA), dried, and exposed to film.

Yeast two-hybrid assay

The yeast two-hybrid assay was performed with the LexA system (CLONTECH), as previously described (58). The β-galactosidase activity was normalized for O.D. value at 600 nm. Fold induction was calculated by the ratio of adjusted β-galactosidase values of transformed cells cultured in the presence of galactose/raffinose vs. those in the medium containing glucose.

Coimmunoprecipitation assay and Western blot

Rat primary cortical neuronal cells were treated with 10−8m aldosterone or vehicle for 2 h. Cells were lysed in buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mm NaCl, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and 1Tab/50 ml Complete Tablet, and coimmunoprecipitation was carried out as previously described (25). Proteins were immunoprecipitated by anti-MR (C-19), -GR (P-20), or -CDK5 (C-8) antibody or control rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), and the protein-antibody complexes were collected with Protein Agarose A/G PLUS (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). Associated proteins were separated in 4–20% SDS-PAGE gels and blotted on nitrocellulose membranes, and MR-associated CDK5 and p35 or CDK5-associated MR and GR were detected by anti-CDK5 (C-8), -p35 (C-19), -MR (C-19), and -GR (P-20) antibodies, respectively (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). To evaluate endogenously or exogenously expressed MR, GR, CDK5, p35, and β-actin, 10% of cell lysates used in the coimmunoprecipitation reaction were run on SDS-PAGE gels, and Western blots were performed by using their specific antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). Nuclear extracts were prepared from whole homogenates of HCT116 cells transfected with MR-, CDK5- and/or p25-expressing plasmids and treated with 10−8m of aldosterone for 1 h, as previously reported (58,59). Nuclear accumulated MRs were subsequently examined in Western blots by using anti-MR (C-19) antibody. Oct1 was used as a positive control for the nuclear fraction as previously reported (58). To evaluate phosphorylation of serine or threonine residues of MR by CDK5, rat primary cortical neuronal cells or HCT116 cells transfected with wild-type or mutant MR-expressing plasmids together with those expressing CDK5 and p25 were treated with 10−8m of aldosterone or vehicle for 1 h, and cell lysates were produced as described above. MRs were immunoprecipitated by anti-MR antibody or control rabbit IgG, and phosphorylated serine or threonine residues of MR by CDK5 were examined in Western blots by using the antibodies specific to phosphoserine (16B4) or phosphothreonine (1F11) residues (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.).

In vitro phosphorylation of GST-hMR (1-602) by CDK5 and subsequent mass spectrometry analyses

Culture (∼ 1 liter) of the BL21 bacteria transformed with pGEX-2T-hMR (1-602) or pGEX-4T3-GR (1-490), and GST-hMR (1-602) and GST-hGR (1-490) proteins were purified by using the Glutathione Sepharose GSTrap 4B columns (GE Healthcare Bioscience Corp.). These proteins were mixed with 10 ng of active CDK5 and p35 (Millipore Corp., Billerica, MA) in a buffer containing 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.4), 1 mm EDTA, 10 mm MgCl2, 0.2 mm dithiothreitol, and a protease inhibitor cocktail (2 μl) in a final volume of 50 μl (25). The reaction was started by addition of 100 μm ATP and incubated at 30 C for 30 min. The samples were buffer exchanged into 25 mm NH4HCO3 by using 30K Nanosep Centrifugal Devices (Pall Corp., East Hills, NY). They were then dried in the SpeedVac System (ThermoSavant Corp., Holbrook, NY) and were taken up in 8 m urea/0.4 m NH4HCO3 for reduction (by dithiothreitol) and alkylation (by iodoacetamide) according to the standard protocol (60). After diluting the samples into 2 m urea/0.1 m NH4HCO3 with water, half of each sample was digested with trypsin and half with chymotrypsin overnight at 37 C. Digested samples were then acidified with trifluoroacetic acid, combined, and cleaned up in the OASIS HLB media (Waters Corp., Milford, MA). Eluted digests were dried in the SpeedVac system and were subjected to enrich the phosphorylated peptides by the TiO2 chromatography, according to the method of Wu et al. (61). Phosphopeptide-enriched samples were finally analyzed with liquid chromatography /tandem mass spectroscopy (MS/MS) on an LTQ XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron Corp., San Jose, CA) where the instrument was set up to acquire a full survey scan followed by a collision-induced dissociation MS/MS spectrum on each of the top 10 most abundant ions in the survey scan. MS/MS Spectra were searched by using the SEQUEST program (Thermo Electron, Inc.) against a FASTA database, which consists of sequences of the pertinent protein and several decoy protein to identify phosphopeptides and specific phosphorylation sites.

SYBR Green real-time PCR for quantification of mRNA

Rat primary cortical neuronal cells were incubated with 10−8m aldosterone, 10−6m of dexamethasone, 10−6m of eplerenone, 10−5m of RU 486 and/or 20 μm roscovitine for the indicated time periods. After the incubation, total RNA was purified from these cells by using the RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN, Inc., Valencia, CA), treated with deoxyribonuclease (Promega), and were reverse transcribed to cDNA with the TaqMan reverse transcription reagents (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The real-time PCR was performed in triplicate using the SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) in the 7500 real-time PCR System (Applied Biosystems), as previously described (25). The primer pairs used for measuring mRNA levels of BDNF, TrkB, p75NTR, CDK5, p35, and CREB1 are shown in Table 3. The obtained Ct (threshold cycle) values of these molecules were normalized for those of the acidic ribosomal phosphoprotein P0 (RPLP0), and their relative mRNA expressions were demonstrated as fold induction to baseline. The dissociation curves of primer pairs used showed a single peak and samples after PCRs had a single expected DNA band in an agarose gel analysis (data not shown).

Table 3.

Primer pairs used in the real-time PCR

| Gene name (rat) | Primer sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|

| BDNF | |

| Forward | GACTGCAGTGGACATGTC |

| Reverse | CAGCCTTCCTTCGTGTAACC |

| TrkB | |

| Forward | CCTGGAGTTGACTATGAG |

| Reverse | GATGCTCCCGATTGGTTTGG |

| p75NTR | |

| Forward | CACAGCGACAGTGGCATCTC |

| Reverse | CAGGGGCAGGCTACTGTAGAG |

| CDK5 | |

| Forward | GTCAGGCTTCATGATGTC |

| Reverse | GAGGAGTGACTTCACAATCTC |

| CREB1 | |

| Forward | GTTATTCAGTCTCCACAAGTC |

| Reverse | GAAGGCCTCCTTGAAAGG |

| p35 | |

| Forward | CTACCGCCTGAAGCACTTGTC |

| Reverse | GTAGAGGAAGACCACATTGG |

| RPLP0 | |

| Forward | GAGAAGACCTCTTTCTTC |

| Reverse | CAACATGTTCAGCAGTGTG |

Measurement of BDNF secreted into media

Rat cortical neuronal cells were incubated with 10−8m aldosterone, 10−6m dexamethasone, 10−6m eplerenone, 10−5m of RU 486 or indicated concentrations of aldosterone, corticosterone, or dexamethasone and/or 20 μm of roscovitine for the indicated time periods. After the incubation, medium was collected and BDNF levels were determined by using the ChemiKine BDNF Sandwich ELISA Kit (Millipore Corp., Bedford, MA).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out by unpaired Student’s t test with the two-tailed P value.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. G. L. Hager (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD), M. Lombès (University of Paris, Le Kremlin-Bicêtre, France), and N. Warriar Centre 71, Rocherche, Hôtel-Dieu Québec and Laval University, Québec, Canada) for providing their plasmids and Mr. E. K. Zachman (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) for his superb technical assistance. We thank Pfizer Inc. (Groton, CT) for providing eplerenone.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

Disclosure Summary: All authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online March 31, 2010

Abbreviations: BDNF, Brain-derived neurotrophic factor; CDK, cyclin-depenedent kinase; CNS, central nervous system; CREB, cAMP response element-binding protein; DBD, DNA-binding domain; GR, glucocorticoid receptor; GRIP1, GR-interacting protein 1; GST, glutathione-S-transferase; HDAC, histone deacetylase; 11βHSD, 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase; LBD, ligand-binding domain; LTP, long-term potentiation; MMTV, mouse mammary tumor virus; MR, mineralocorticoid receptor; MS/MS, tandem mass spectrometry; NRB, nuclear receptor-binding domain; NTD, N-terminal domain; RPLP0, ribosomal phosphoprotein P0; siRNA, small interfering RNA; TrkB, receptor tyrosine kinase B.

References

- Kino T, Chrousos GP 2005 Glucocorticoid effect on gene expression. In: Steckler T, Kalin NH, Reul JMHM, eds. Handbook on stress and the brain. Amsterdam: Elsevier BV; 295–312 [Google Scholar]

- de Kloet ER, Derijk RH, Meijer OC 2007 Therapy insight: is there an imbalanced response of mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptors in depression? Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 3:168–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fietta P, Fietta P 2007 Glucocorticoids and brain functions. Riv Biol 100:403–418 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashid S, Lewis GF 2005 The mechanisms of differential glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid action in the brain and peripheral tissues. Clin Biochem 38:401–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kino T, Chrousos GP 2004 Glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors and associated diseases. Essays Biochem 40:137–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrousos GP, Kino T 2005 Intracellular glucocorticoid signaling: a formerly simple system turns stochastic. Sci STKE 2005:pe48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna NJ, Lanz RB, O'Malley BW 1999 Nuclear receptor coregulators: cellular and molecular biology. Endocr Rev 20:321–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld MG, Lunyak VV, Glass CK 2006 Sensors and signals: a coactivator/corepressor/epigenetic code for integrating signal-dependent programs of transcriptional response. Genes Dev 20:1405–1428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaides NC, Galata Z, Kino T, Chrousos GP, Charmandari E 2010 The glucocorticoid receptor: molecular basis of biologic function. Steroids 75:1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortlund EA, Bridgham JT, Redinbo MR, Thornton JW 2007 Crystal structure of an ancient protein: evolution by conformational epistasis. Science 317:1544–1548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrousos GP 2001 Glucocorticoid therapy. In: Felig P, Frohman LA, eds. Endocrinology, metabolism, 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 609–632 [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs WJ, Orth DN 1998 The adrenal cortex. In: Wilson J, D, Foster DW, eds. Williams textbook of endocrinology. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co.; 517–750 [Google Scholar]

- Ohshima T, Ward JM, Huh CG, Longenecker G, Veeranna, Pant HC, Brady RO, Martin LJ, Kulkarni AB 1996 Targeted disruption of the cyclin-dependent kinase 5 gene results in abnormal corticogenesis, neuronal pathology and perinatal death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:11173–11178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhavan R, Tsai LH 2001 A decade of CDK5. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2:749–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai LH, Delalle I, Caviness Jr VS, Chae T, Harlow E 1994 p35 is a neural-specific regulatory subunit of cyclin-dependent kinase 5. Nature 371:419–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang D, Wang JH 1996 Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (Cdk5) and neuron-specific Cdk5 activators. Prog Cell Cycle Res 2:205–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julien JP, Mushynski WE 1998 Neurofilaments in health and disease. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol 61:1–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau LF, Seymour PA, Sanner MA, Schachter JB 2002 Cdk5 as a drug target for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. J Mol Neurosci 19:267–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KY, Clark AW, Rosales JL, Chapman K, Fung T, Johnston RN 1999 Elevated neuronal Cdc2-like kinase activity in the Alzheimer disease brain. Neurosci Res 34:21–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlijanian MK, Barrezueta NX, Williams RD, Jakowski A, Kowsz KP, McCarthy S, Coskran T, Carlo A, Seymour PA, Burkhardt JE, Nelson RB, McNeish JD 2000 Hyperphosphorylated tau and neurofilament and cytoskeletal disruptions in mice overexpressing human p25, an activator of cdk5. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:2910–2915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen MD, Larivière RC, Julien JP 2001 Deregulation of Cdk5 in a mouse model of ALS: toxicity alleviated by perikaryal neurofilament inclusions. Neuron 30:135–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz JC, Tseng HC, Goldman JA, Shih H, Tsai LH 2003 Aberrant Cdk5 activation by p25 triggers pathological events leading to neurodegeneration and neurofibrillary tangles. Neuron 40:471–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MS, Kwon YT, Li M, Peng J, Friedlander RM, Tsai LH 2000 Neurotoxicity induces cleavage of p35 to p25 by calpain. Nature 405:360–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusakawa G, Saito T, Onuki R, Ishiguro K, Kishimoto T, Hisanaga S 2000 Calpain-dependent proteolytic cleavage of the p35 cyclin-dependent kinase 5 activator to p25. J Biol Chem 275:17166–17172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kino T, Ichijo T, Amin ND, Kesavapany S, Wang Y, Kim N, Rao S, Player A, Zheng YL, Garabedian MJ, Kawasaki E, Pant HC, Chrousos GP 2007 Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 differentially regulates the transcriptional activity of the glucocorticoid receptor through phosphorylation: clinical implications for the nervous system response to glucocorticoids and stress. Mol Endocrinol 21:1552–1568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesavapany S, Li BS, Amin N, Zheng YL, Grant P, Pant HC 2004 Neuronal cyclin-dependent kinase 5: role in nervous system function and its specific inhibition by the Cdk5 inhibitory peptide. Biochim Biophys Acta 1697:143–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco PJ, Li G, Wei LN 2003 Interaction of nuclear receptor zinc finger DNA binding domains with histone deacetylase. Mol Cell Endocrinol 206:1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Wang J, Sauter NK, Pearce D 1995 Steroid receptor heterodimerization demonstrated in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92:12480–12484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou XM, Storring JM, Kushwaha N, Albert PR 2001 Heterodimerization of mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptors at a novel negative response element of the 5-HT1A receptor gene. J Biol Chem 276:14299–14307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veeranna, Shetty KT, Link WT, Jaffe H, Wang J, Pant HC 1995 Neuronal cyclin-dependent kinase-5 phosphorylation sites in neurofilament protein (NF-H) are dephosphorylated by protein phosphatase 2A. J Neurochem 64:2681–2690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Songyang Z, Lu KP, Kwon YT, Tsai LH, Filhol O, Cochet C, Brickey DA, Soderling TR, Bartleson C, Graves DJ, DeMaggio AJ, Hoekstra MF, Blenis J, Hunter T, Cantley LC 1996 A structural basis for substrate specificities of protein Ser/Thr kinases: primary sequence preference of casein kinases I and II, NIMA, phosphorylase kinase, calmodulin-dependent kinase II, CDK5, and Erk1. Mol Cell Biol 16:6486–6493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaudette KN, Lew J, Wang JH 1993 Substrate specificity characterization of a cdc2-like protein kinase purified from bovine brain. J Biol Chem 268:20825–20830 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick GN, Zhou P, Kwon YT, Howley PM, Tsai LH 1998 p35, the neuronal-specific activator of cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (Cdk5) is degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. J Biol Chem 273:24057–24064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan TC, Valova VA, Malladi CS, Graham ME, Berven LA, Jupp OJ, Hansra G, McClure SJ, Sarcevic B, Boadle RA, Larsen MR, Cousin MA, Robinson PJ 2003 Cdk5 is essential for synaptic vesicle endocytosis. Nat Cell Biol 5:701–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JR, Lynch WJ, Sanchez H, Olausson P, Nestler EJ, Bibb JA 2007 Inhibition of Cdk5 in the nucleus accumbens enhances the locomotor-activating and incentive-motivational effects of cocaine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:4147–4152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindan MV, Warriar N 1998 Reconstitution of the N-terminal transcription activation function of human mineralocorticoid receptor in a defective human glucocorticoid receptor. J Biol Chem 273:24439–24447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernfors P, Bramham CR 2003 The coupling of a trkB tyrosine residue to LTP. Trends Neurosci 26:171–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair A, Vaidya VA 2006 Cyclic AMP response element binding protein and brain-derived neurotrophic factor: molecules that modulate our mood? J Biosci 31:423–434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shors TJ, Seib TB, Levine S, Thompson RF 1989 Inescapable versus escapable shock modulates long-term potentiation in the rat hippocampus. Science 244:224–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond DM, Fleshner M, Rose GM 1994 Psychological stress repeatedly blocks hippocampal primed burst potentiation in behaving rats. Behav Brain Res 62:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa N, Almeida OF 2002 Corticosteroids: sculptors of the hippocampal formation. Rev Neurosci 13:59–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gass P, Kretz O, Wolfer DP, Berger S, Tronche F, Reichardt HM, Kellendonk C, Lipp HP, Schmid W, Schütz G 2000 Genetic disruption of mineralocorticoid receptor leads to impaired neurogenesis and granule cell degeneration in the hippocampus of adult mice. EMBO Rep 1:447–451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle MP, Kolber BJ, Vogt SK, Wozniak DF, Muglia LJ 2006 Forebrain glucocorticoid receptors modulate anxiety-associated locomotor activation and adrenal responsiveness. J Neurosci 26:1971–1978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle MP, Brewer JA, Funatsu M, Wozniak DF, Tsien JZ, Izumi Y, Muglia LJ 2005 Acquired deficit of forebrain glucocorticoid receptor produces depression-like changes in adrenal axis regulation and behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:473–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronche F, Kellendonk C, Kretz O, Gass P, Anlag K, Orban PC, Bock R, Klein R, Schütz G 1999 Disruption of the glucocorticoid receptor gene in the nervous system results in reduced anxiety. Nat Genet 23:99–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gass P, Reichardt HM, Strekalova T, Henn F, Tronche F 2001 Mice with targeted mutations of glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors: models for depression and anxiety? Physiol Behav 73:811–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindvall O, Kokaia Z, Bengzon J, Elmér E, Kokaia M 1994 Neurotrophins and brain insults. Trends Neurosci 17:490–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korte M, Kang H, Bonhoeffer T, Schuman E 1998 A role for BDNF in the late-phase of hippocampal long-term potentiation. Neuropharmacology 37:553–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H, Schuman EM 1995 Long-lasting neurotrophin-induced enhancement of synaptic transmission in the adult hippocampus. Science 267:1658–1662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korte M, Carroll P, Wolf E, Brem G, Thoenen H, Bonhoeffer T 1995 Hippocampal long-term potentiation is impaired in mice lacking brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92:8856–8860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson MP, Lovell MA, Furukawa K, Markesbery WR 1995 Neurotrophic factors attenuate glutamate-induced accumulation of peroxides, elevation of intracellular Ca2+ concentration, and neurotoxicity and increase antioxidant enzyme activities in hippocampal neurons. J Neurochem 65:1740–1751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagahara AH, Merrill DA, Coppola G, Tsukada S, Schroeder BE, Shaked GM, Wang L, Blesch A, Kim A, Conner JM, Rockenstein E, Chao MV, Koo EH, Geschwind D, Masliah E, Chiba AA, Tuszynski MH 2009 Neuroprotective effects of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in rodent and primate models of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med 15:331–337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuluđ B, Ozan E, Gönül AS, Kilic E 2009 Brain-derived neurotrophic factor, stress and depression: a minireview. Brain Res Bull 78:267–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaaf MJ, Hoetelmans RW, de Kloet ER, Vreugdenhil E 1997 Corticosterone regulates expression of BDNF and trkB but not NT-3 and trkC mRNA in the rat hippocampus. J Neurosci Res 48:334–341 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murer MG, Yan Q, Raisman-Vozari R 2001 Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the control human brain, and in Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. Prog Neurobiol 63:71–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kino T, Slobodskaya O, Pavlakis GN, Chrousos GP 2002 Nuclear receptor coactivator p160 proteins enhance the HIV-1 long terminal repeat promoter by bridging promoter-bound factors and the Tat-P-TEFb complex. J Biol Chem 277:2396–2405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichijo T, Voutetakis A, Cotrim AP, Bhattachryya N, Fujii M, Chrousos GP, Kino T 2005 The Smad6-histone deacetylase 3 complex silences the transcriptional activity of the glucocorticoid receptor: potential clinical implications. J Biol Chem 280:42067–42077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kino T, Tiulpakov A, Ichijo T, Chheng L, Kozasa T, Chrousos GP 2005 G protein β interacts with the glucocorticoid receptor and suppresses its transcriptional activity in the nucleus. J Cell Biol 169:885–896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nader N, Chrousos GP, Kino T 2009 Circadian rhythm transcription factor CLOCK regulates the transcriptional activity of the glucocorticoid receptor by acetylating its hinge region lysine cluster: potential physiological implications. FASEB J 23:1572–1583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone KL, Williams KR 1993 Enzymatic digestion of proteins and HPLC peptide isolation. In: Matsudaira PT, ed. A practical guide to protein and peptide purification for microsequencing. 2nd ed. San Diego, CA: Academic Press, Inc.; 43–69 [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Shakey Q, Liu W, Schuller A, Follettie MT 2007 Global profiling of phosphopeptides by titania affinity enrichment. J Proteome Res 6:4684–4689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]