Abstract

Objective:

To determine if mexiletine is safe and effective in reducing myotonia in myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1).

Background:

Myotonia is an early, prominent symptom in DM1 and contributes to decreased dexterity, gait instability, difficulty with speech/swallowing, and muscle pain. A few preliminary trials have suggested that the antiarrhythmic drug mexiletine is useful, symptomatic treatment for nondystrophic myotonic disorders and DM1.

Methods:

We performed 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trials, each involving 20 ambulatory DM1 participants with grip or percussion myotonia on examination. The initial trial compared 150 mg of mexiletine 3 times daily to placebo, and the second trial compared 200 mg of mexiletine 3 times daily to placebo. Treatment periods were 7 weeks in duration separated by a 4- to 8-week washout period. The primary measure of myotonia was time for isometric grip force to relax from 90% to 5% of peak force after a 3-second maximum grip contraction. EKG measurements and adverse events were monitored in both trials.

Results:

There was a significant reduction in grip relaxation time with both 150 and 200 mg dosages of mexiletine. Treatment with mexiletine at either dosage was not associated with any serious adverse events, or with prolongation of the PR or QTc intervals or of QRS duration. Mild adverse events were observed with both placebo and mexiletine treatment.

Conclusions:

Mexiletine at dosages of 150 and 200 mg 3 times daily is effective, safe, and well-tolerated over 7 weeks as an antimyotonia treatment in DM1.

Classification of Evidence:

This study provides Class I evidence that mexiletine at dosages of 150 and 200 mg 3 times daily over 7 weeks is well-tolerated and effective in reducing handgrip relaxation time in DM1.

GLOSSARY

- DM1

= myotonic dystrophy type 1;

- MVIC

= maximal voluntary isometric contraction;

- PF

= peak force;

- RT

= relaxation time;

- TID

= 3 times daily.

Myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1) is a multisystem, dominantly inherited disease caused by an unstable CTG repeat expansion in the 3′ nontranslated region of the DM1 gene on chromosome 19.1 Myotonia, weakness of facial and distal limb muscles, and cataracts are core clinical findings.2,3 Using various methods to measure myotonia, previous studies have reported antimyotonic effects for quinine,4,5 sodium channel blockers (phenytoin, procainamide, tocainide, mexiletine, carbamazepine),4,6–11 antidepressants (amitriptyline, clomipramine, imipramine),12–14 calcium channel blockers,15 benzodiazepines,16 prednisone,4 dehydroepiandrosterone,17 taurine,18 acetazolamide,19 and others. Recent studies have focused on the class Ib antiarrhythmic lidocaine analogs mexiletine7,20–22 and tocainide.7,8,10,23,24

One randomized study suggested that mexiletine at 400 to 600 mg daily is a safe and effective antimyotonia medication.7 (Although tocainide has also been reported to be effective in treating myotonia,8 bone marrow suppression8,25 limits its use.) While this study7 was an important step forward, it had some deficiencies: short duration (4 weeks), a heterogeneous patient group, a single-blind study design, heterogeneous treatment group sample sizes, and incomplete validation of the methods used to measure myotonia. Moreover, a recent Cochrane review concluded that none of the myotonia treatment studies reported as of 2006 were of sufficiently high quality to conclude that any available drug treatment of myotonia is effective and safe.26

Given the need for a more definitive antimyotonia treatment trial, we prospectively evaluated the effect of mexiletine on grip myotonia and cardiac conduction in DM1 in 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trials, the first using a dosage of 150 mg 3 times daily (TID) and the second using 200 mg TID.

METHODS

Study participants.

A total of 30 participants were enrolled in the 2 trials: 20 in the 150 mg TID trial (June 1, 2000–March 29, 2002) and 20 in the 200 mg TID trial (May 14, 2001–March 20, 2003); 10 participants enrolled in both trials. Patients were eligible if they were between the ages of 18 and 80, could walk 15 feet independently, had sufficient finger flexor strength to grasp a handle, met standard clinical criteria for the presence of myotonia (time for fingers to fully uncurl following maximal hand grip estimated by visual inspection to be 3 seconds or more, or percussion myotonia in wrist extensor and thenar muscles), satisfied clinical criteria for DM1,27 and had genetic confirmation of the diagnosis. Patients were ineligible if they were unable to give informed consent, were pregnant or lactating, were taking a medication known to affect myotonia, had a coexisting neuromuscular disease, or had another serious medical illness including second- or third-degree heart block, atrial flutter, atrial fibrillation, ventricular arrhythmia, history of cardiac arrhythmia requiring medication, congestive heart failure, symptomatic cardiomyopathy, or symptomatic coronary artery disease.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

All study participants gave written informed consent, and all study procedures received approval from the Institutional Review Board at the University of Rochester.

Randomization and enrollment.

We carried out 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trials (figure 1). In each trial, the 2 treatment periods were 7 weeks in duration separated by a 4- to 8-week washout period. Those who participated in both trials (n = 10) were required to wait at least 8 weeks after the end of the first trial to enroll in the second trial. Participants were randomly assigned in each trial to 1 of 2 treatment sequences: mexiletine/placebo or placebo/mexiletine. The computer-generated randomization plans included blocking to ensure approximate balance between the 2 treatment sequences. A programmer in the Department of Biostatistics (Rochester, NY) generated the randomization plans and sent them to the pharmacy where drug packaging and labeling took place. All drug was labeled with a participant ID number. Only the biostatistics programmer and the pharmacist had access to the treatment assignments. Drug was assigned sequentially. The study coordinator was required to check all baseline forms for completeness and verify eligibility criteria before calling the pharmacy to officially randomize a participant.

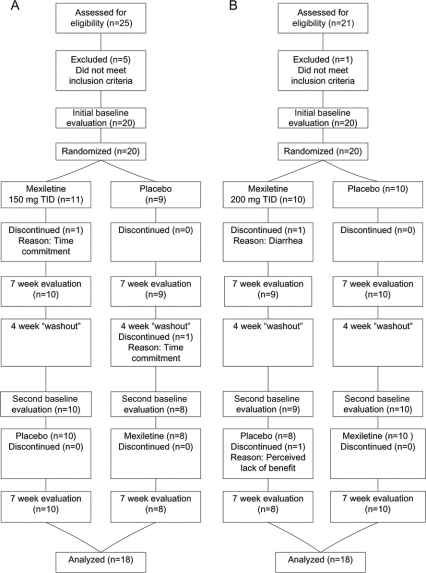

Figure 1 Consort flow diagram

Participant flow in the trial of mexiletine 150 mg TID (A) and in the trial of mexiletine 200 mg TID (B).

Therapy and follow-up.

For both trials, all participants were admitted to the University of Rochester General Clinical Research Center for an inpatient visit at the beginning (baseline 4-day admission) and at the end (2-day admission) of each 7-week treatment period. Fasting mexiletine drug levels were obtained on the first morning of each admission. An EKG was obtained on admission (day 1) and daily for the first 2 days that new treatment was initiated (days 3 and 4) at the baseline visit, and on both days of the week 7 visit. Myotonia testing (see below) took place in the morning (6:30–8:30 am) on the first 2 days of each admission (baseline and week 7) following an overnight fast. Randomization was performed on the morning of day 3 of the initial admission, after all baseline measurements were obtained.

Reports of adverse events, vital signs, and safety laboratory tests (comprehensive chemistry panel, CBC with differential, platelet count, PTT, APTT, T4, TSH, and urinalysis) were obtained at each inpatient visit as well as outpatient visits held during week 3 of each treatment period. Adverse events were also monitored during telephone calls at weeks 2 and 5 of each treatment period.

Mexiletine was purchased from Roxane Laboratories, Inc., and placebo was prepared by the pharmacy at the University of Rochester. Active and placebo medication were re-encapsulated in gelatin capsules by the pharmacy to facilitate blinding. The dosage was titrated so that TID dosing was reached by day 7 of each treatment period. Medication was tapered over 6 days after the completion of each treatment period.

Myotonia testing.

The right arm was used for measuring grip relaxation times (RTs) after a maximal voluntary isometric contraction (MVIC) as described previously.28,29 In brief, each trial consisted of 6 maximal voluntary contractions, each lasting 3 seconds, with a 10-second rest period between each contraction. Three sets of measurements (trials) were performed with 10-minute intervals of rest between trials.

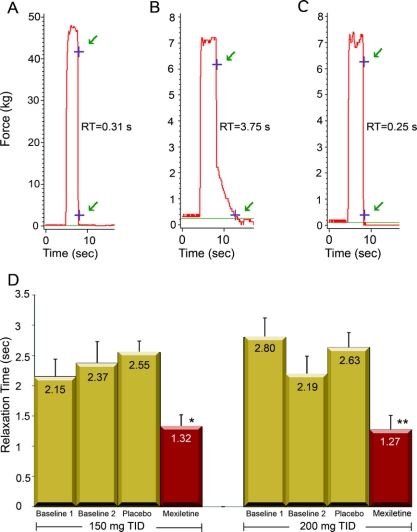

An automated computer program first determined peak force (PF) in kg units and then placed cursors on the declining, relaxation phase of the force recording at various levels of PF: 90%, 50%, and 5% (figure 2).28,29 The RTs reported here are the times required for decline in force from 90% to 5%, 90% to 10%, and 50% to 5% of PF.

Figure 2 Grip relaxation time (myotonia)

Maximum voluntary handgrip force traces in (A) a normal subject, and in DM1 participant 1843, (B) before and (C) after treatment with 7 weeks of mexiletine 200 mg TID. Automated software placed cursors (arrows) on the declining force trace at 90% and 5% of peak force. The 90%–5% hand grip relaxation times (RTs) are denoted to the right of each trace. (D) Mean 90%–5% hand grip RTs at the 2 baseline visits, and on placebo and mexiletine treatment for the 150 mg TID trial (left) and the 200 mg TID trial (right). The extensions of the bars represent 1 SEM. p Values for mexiletine treatment-related improvement in RT were *0.0004 (150 mg TID) and **0.001 (200 mg TID).

Grip RT and PF were calculated from the initial contraction from each of the 3 trials on the first 2 days of admission (6 trials total). The additional contractions 2–5 were analyzed for study of the warm-up phenomenon as previously reported.28 The mean PF and RT were determined by averaging these values from the 6 trials over the 2 days of evaluation.

Sample size determination.

The sample size of 20 participants was chosen to provide 80% power to detect a treatment effect of 0.66 SD units using a 2-tailed paired t test and a 5% significance level.

Statistical analysis.

The primary outcome variable for efficacy was the average RT (time to decline in force from 90% to 5% of PF). Secondary outcome variables included other average RTs (90%–10% of PF, 50%–5% of PF) and average PF. EKG outcomes, including PR interval, QRS interval, and QTc interval, were of primary interest from the perspective of safety. The primary statistical analyses of the data from week 7 of each treatment period used an analysis of variance model that included effects for treatment, period, and participant. Mean mexiletine–placebo differences (treatment effects) and associated 95% confidence intervals were estimated using this model. Only participants who completed both treatment periods were included in the primary statistical analyses. The results of analyses that included data from all randomized participants (mixed-effects analysis of variance model) and those that excluded data from 3 participants with undetectable mexiletine levels yielded nearly identical results.

RESULTS

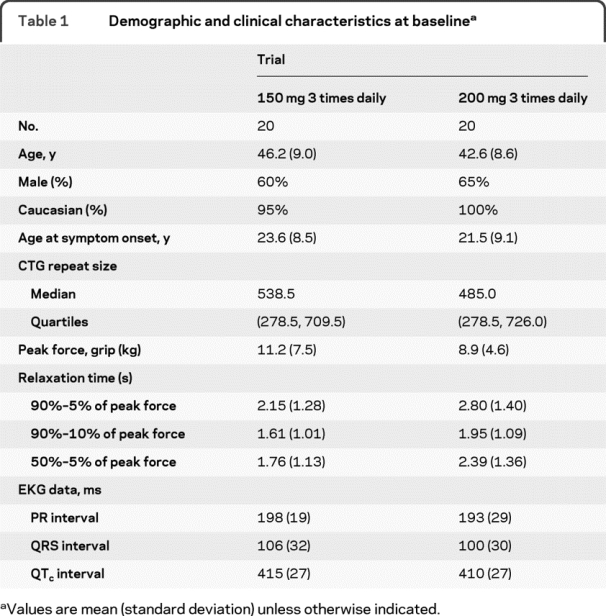

The participants in both studies were middle-aged with a slight male predominance (table 1). Symptoms had been present for a mean of about 2 decades, and median CTG repeat sizes were approximately 500 in both groups with a minimum of 169. Four participants dropped out of the study after the initial General Clinical Research Center visit: 2 participants in the 150 mg TID trial (1 on placebo and 1 on mexiletine, both due to family reasons and inability to fulfill the required time commitment) and 2 participants in the 200 mg TID trial (1 on placebo due to perceived lack of therapeutic benefit and 1 on mexiletine due to diarrhea).

Table 1 Demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline

Trough blood levels of mexiletine were somewhat higher with 200 mg TID (0.86 ± 0.48 μg/mL, range 0–1.70 μg/mL) than with 150 mg TID (0.54 ± 0.28 μg/mL, range 0–1.15 μg/mL). Mexiletine blood levels reached the therapeutic range for treating arrhythmia (0.5–2.0 μg/mL) in 13 patients (68%) with 200 mg TID and in 10 patients (55%) with 150 mg TID. Three participants (1 in the 150 mg TID trial and 2 in the 200 mg TID trial) had a mexiletine blood level of 0. When these possible noncompliers were removed, the blood levels achieved the therapeutic range in 76% of those on 200 mg TID and 59% of those on 150 mg TID.

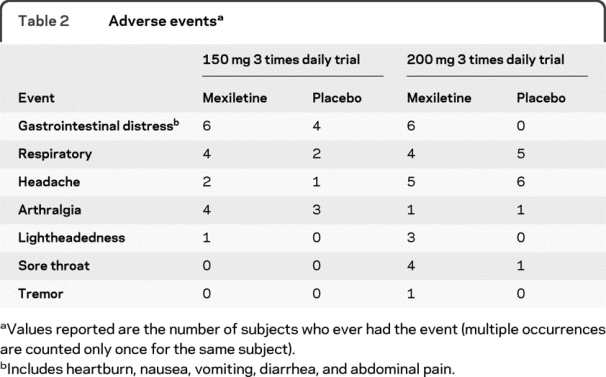

Mexiletine was generally well-tolerated and there were no significant adverse events at either dosage. Adverse events were mild (table 2), and slightly more common with mexiletine treatment than with placebo treatment. Adverse events that seemed to be more common with mexiletine were mild upper gastrointestinal distress and lightheadedness. As noted above, mexiletine treatment was discontinued due to an adverse event (diarrhea) in only 1 participant while taking 200 mg TID mexiletine.

Table 2 Adverse events

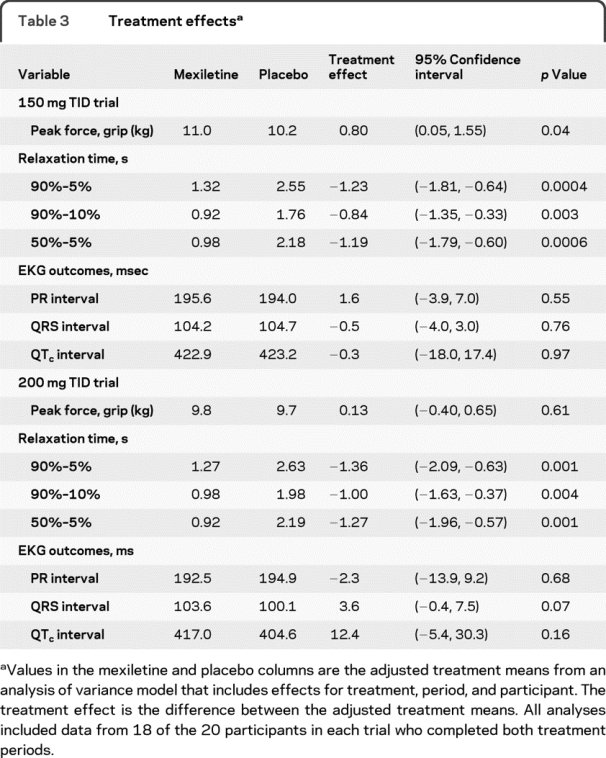

In both trials, there were no significant effects of mexiletine on EKG measurements (table 3, table e-1 on the Neurology® Web site at www.neurology.org). The mean PR, QRS, and QTc intervals remained stable over time with mexiletine and placebo treatment.

Table 3 Treatment effects

The MVIC grip traces showed prolonged 90%–5% RTs, particularly in the terminal portion of the relaxation phase (figure 2B). In both trials, the RTs were elevated at baseline (table 1) and during placebo treatment (table 3; figure 2) with mean 90%–5% RTs of over 2 seconds. Mexiletine at the 150 mg TID and 200 mg TID dosages was associated with a significant reduction in RT, with mean reductions of 48% (90%–5% RT), 48% (90%–10% RT), and 55% (50%–5%) with 150 mg TID and mean reductions of 52% (90%–5% RT), 51% (90%–10% RT), and 58% (50%–5%) with 200 mg TID (table 3, table e-2, figure 2). In both the 150 mg TID and 200 mg TID trials, 17 of the 18 participants (94%) had a shorter 90%–5% RT on mexiletine than on placebo. There was a significant improvement in peak grip force with 150 mg TID mexiletine compared to placebo (table 3), but this was not the case with 200 mg TID mexiletine (table 3).

DISCUSSION

The major finding in these randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of mexiletine in DM1 is that dosages of 150 and 200 mg TID for 7 weeks significantly improve myotonia, as measured by hand grip relaxation time, but do not cause significant adverse events or produce EKG conduction abnormalities in the short term.

These trials have several advantages over previous myotonia treatment trials in patients with DM1. 1) These studies are the largest we are aware of in that 20 genetically defined DM1 patients participated in each of the 2 trials. Previous trials have included relatively small numbers of DM1 patients, have often included participants with different forms of myotonic myopathy, and none have provided genetic confirmation. 2) These trials were double-blind; previous trials of mexiletine or tocainide for myotonia in DM1 have been single blind7 or unblinded.8 3) The improvement in myotonia noted in our first trial was corroborated by the second. 4) Plasma concentrations of mexiletine were measured, a requirement for the tocainide study,8 but not in the previous mexiletine study.7 5) These trials employed a carefully tested method of measuring grip myotonia28,29 that has good test-retest reproducibility, and yields grip relaxation times that increase and grip peak forces that decrease as CTG repeat lengths increase. Ergonomic techniques have been used to measure myotonia in patients with myotonic dystrophy for some time,9,30 but they have not been as carefully tested. The previous study of mexiletine7 utilized timed measurements of eye and hand opening, stair climbing, and the opponens pollicis, surface EMG-recorded myotonic afterdischarge that have merit as outcome measures, but again, have not been as carefully validated as our method.

Mexiletine is a lidocaine analog.31 Both drugs are type Ib anti-arrhythmics and produce state-dependent block of inactivated and to a lesser extent open (but not resting) sodium channels in cardiac and skeletal muscle; therefore, the channel block produced by these medications is mainly action potential-dependent. The 2 drugs differ in that sodium channel block induced by mexiletine is slightly slower to recover than that from lidocaine. In addition, hepatic metabolism is greatly reduced for mexiletine, which makes it suitable as an oral medication. Mexiletine is effective in cardiac patients with ventricular arrhythmias31 and long QT syndrome32 and in neuromuscular patients with myotonic disorders such as potassium aggravated myotonia or paramyotonia congenita.33,34 These myotonic disorders are skeletal muscle sodium channelopathies which typically manifest a slowed rate of fast sodium channel inactivation. This results in abnormally persistent sodium currents leading to repetitive firing of muscle fibers and delayed muscle relaxation (myotonia).33–35

Mexiletine ameliorates myotonia in sodium channelopathies by enhancing fast-inactivation of the sodium channels, resulting in use-dependent sodium channel block.33,34,36,37 In addition, mexiletine may also produce open channel block of late-opening channels38 at lower serum concentrations than those required to block channels that are closed and inactivated. By contrast, mexiletine is not known to affect skeletal muscle chloride channels, and its beneficial effects in patients with chloride channel myotonic disorders, such as DM1 or myotonia congenita, probably result from block of normal sodium channels which thereby decrease repetitive motor unit discharges.33,34 Our data show that even moderate oral dosages of 150 mg TID with drug levels in the low to mid-therapeutic range (by cardiac standards) reduce handgrip myotonia in DM1. Importantly, although mexiletine produces use-dependent sodium channel blockade and could result in loss of muscle strength, there was no decline in grip peak force on mexiletine at either dosage. On the contrary, peak force significantly improved on mexiletine 150 mg TID, but this was not confirmed by the 200 mg TID trial. In any case, the preservation of grip force on mexiletine is consistent with the absence of significant cardiac hemodynamic compromise in patients on mexiletine for ventricular arrhythmia.31

Given that patients with DM1 may have abnormalities of cardiac conduction,39 a major aim of these trials was to establish that mexiletine did not affect cardiac conduction in patients with DM1 with no baseline cardiac risk factors except first-degree AV block. It is recognized that lidocaine or mexiletine can potentially increase QRS duration particularly at higher heart rates, may shorten the QT interval, may compromise hemodynamic function in patients with heart failure,31 and can increase pacing threshold and the energy required for defibrillation.31 Still, treatment with these drugs in cardiac patients typically has little effect on PR, QRS, and QT duration, or on hemodynamic function.31 Similarly, previous studies of mexiletine and tocainide7,8 in patients with myotonic myopathy of various types have also shown no significant changes in EKG measurements. Our study supports the view that mexiletine at dosages of 150 to 200 mg TID has no significant effect on cardiac conduction over a 7-week treatment period in patients with DM1 who have no significant cardiac risk factors except for first-degree AV Block. However, we recognize that our conclusions about the cardiac safety of mexiletine in DM1 are somewhat tentative given that 1) mexiletine is rarely associated with a pro-arrhythmic response that can aggravate underlying ventricular arrhythmias,40 and 2) our studies involved a total of only 30 patients with DM1 followed for 7 weeks on mexiletine and excluded patients with significant heart disease. As a result, our practice is to obtain cardiac consultation before beginning mexiletine therapy for symptomatic myotonia in patients with DM1 who have current or remote cardiac symptoms or an abnormal baseline EKG.

In our trials, adverse events were observed in participants on placebo and on both dosages of mexiletine (table 2); none were considered serious, and only 1 participant discontinued the drug due to an adverse event. For those completing the trial, the occurrence of upper gastrointestinal distress and lightheadedness appeared to be more common with mexiletine than with placebo. Tremor occurred in only 1 participant taking mexiletine 200 mg TID. These results are similar to those observed previously.7

Overall, our data suggest that mexiletine at oral dosages of 150–200 mg TID may be considered as an effective, symptomatic treatment in patients with DM1 with functionally significant myotonia, and appears to be safe in the short term. Moreover, because the study required the presence of clinical myotonia, but did not specifically require moderate or severe myotonia as in 2 prior trials,7,8 we believe that our data are generalizable to typical patients with DM1 with clinically evident myotonia. The percentage improvement in grip RT was not significantly greater in the 200 mg TID trial than in the 150 mg TID trial. We do not know why our study did not demonstrate a clear dose response effect of mexiletine on grip RT. This may be due to the different baseline characteristics of the 2 groups (e.g., the grip RTs were longer in the 200 mg TID than the 150 mg TID trial) or possibly that the effect of mexiletine on RT plateaus over the 150–200 mg TID dosage range.

One limitation of our trials is that they show relatively short-term benefits of mexiletine on handgrip relaxation. We do not know if this effect is durable over months to years, or if it is associated with improvement in quality of life. Our findings warrant long-term clinical trials with mexiletine in order to determine whether 1) its minimal risk and significant benefit in relieving myotonia are maintained over time, 2) it results in functional improvement in muscle-related activities of daily living, 3) it has a beneficial effect in maintaining muscle strength and mass, 4) it has a beneficial role in reducing or preventing musculoskeletal pain, and 5) it improves quality of life.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Statistical analysis was conducted by Dr. M.P. McDermott and Dr. A.T. Pearson.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Tracy Forrester for help in manuscript preparation.

DISCLOSURE

Dr. Logigian serves on the editorial board of Muscle and Nerve. Mr. Martens and Mr. Moxley report no disclosures. Dr. McDermott has received honoraria from the Michael J. Fox Foundation; has served as a consultant to the New York State Department of Health, the American Epilepsy Society, the Michael J. Fox Foundation, and Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd.; has received research support from Medivation, Inc., Boehringer Ingelheim, NeuroSearch Sweden AB, and Forest Laboratories, Inc.; and receives research support from the NIH (NS42372 [Co-I], HD44430 [Co-I], DE16280 [Co-I], NS52619 [PI], NS45686 [Co-I], NS46487 [Co-I], NS50095 [Co-I], NS49639 [Co-I], AR52274 [Co-I], NS50573 [Co-I], HL80107 [Co-I], RR24160 [Co-I], NS58259 [Co-I], and NS48843 [Co-I]), the US Food and Drug Administration, the Michael J. Fox Foundation, the SMA Foundation, and from the Muscular Dystrophy Association. Ms. Dilek, Dr. Wiegner, Dr. Pearson, Ms. Barbieri, and Ms. Annis report no disclosures. Dr. Thornton receives research support from the NIH (AR046806 [PI], AR049077 [PI], AR48143 [PI], and U54NS48843 [Co-I]), and from the Muscular Dystrophy Association. Dr. Moxley serves on scientific advisory boards for the NIH, the CDC, the Myotonic Dystrophy Foundation, Asklepios BioPharmaceutical, Inc., Acceleron Pharma, Wyeth, and Insmed Inc.; and receives research support from the FDA, the NIH (NIAMS N01-AR-0-2250 [PI], NCRR 5 MO1 RR00044 [Co-Director], NIAMS R01 AR49077 [Co-I], 9 U54NS48843 [PI], NCRR 1UL 1RR02416002 [Co-Director], N01-AR-5-2274 [PI], 1 R13 NS066630-01 [PI], and NIAMS 2 R01 AR049077 [Co-I]), the Saunders Family Foundation, and from the Muscular Dystrophy Association.

Supplementary Material

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Eric Logigian, Department of Neurology, Box 673, 601 Elmwood Ave, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY 14642 eric_logigian@urmc.rochester.edu

Supplemental data at www.neurology.org

Study funding: This work comes from the University of Rochester Senator Paul D. Wellstone Muscular Dystrophy Cooperative Research Center (NIH/NS048843) and Clinical Research Center (NIH/NCRR MO1 RR00044) with support from the Food and Drug Administration (FD-R-001662). The work was also supported by the Saunders Family Neuromuscular Research Fund and NIH (AR49077).

Disclosure: Author disclosures are provided at the end of the article.

Received May 29, 2009. Accepted in final form February 3, 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fu YH, Pizzuti A, Fenwick RG, et al. An unstable triplet repeat in a gene related to myotonic muscular dystrophy. Science 1992;255:1256–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harper PS. Myotonic Dystrophy, 3rd ed. London: WB Saunders; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moxley RT III. Myotonic Dystrophy: Handbook of Clinical Neurology. New York: Elsevier Science; 1992: 209–259. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leyburn P, Walton JN. The treatment of myotonia: a controlled clinical trial. Brain 1959;82:81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolf A. Quinine: an effective form of treatment of myotonia. Arch Neurol Psychiatry 1936;36:382–384. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geschwind N, Simpson JA. Procaine amide in the treatment of myotonia. Brain 1955;78:81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwiecinski H, Ryniewicz B, Ostrzycki A. Treatment of Myotonia with antiarrhythmic drugs. Acta Neurol Scand 1992;86:371–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mielke U, Haass A, Sen S, Schmidt W. Antimyotonic therapy with tocainide under ECG-control in the myotonic dystrophy of Curschmann-Steinert. J Neurol 1985;232:271–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Munsat TL. Therapy of myotonia: a double-blind evaluation of diphenylhydantoin, procainamide, and placebo. Neurology 1967;17:359–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rudel R, Dengler R, Ricker K, Haass A, Emser W. Improved therapy of myotonia with the lidocaine derivative tocainide. J Neurol 1980;222:275–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sechi GP, Traccis S, Durelli L, Monaco F, Mutani R. Carbamazepine versus diphenylhydantoin in the treatment of myotonia. Eur Neurol 1983;22:113–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Antonini G, Vichi R, Leardi MG, Pennisi E, Monza GC, Millefiorini M. Effect of clomipramine on myotonia: a placebo-controlled, double-blind, crossover trial. Neurology 1990;40:1473–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gascon GG, Staton RD, Patterson BD, et al. A pilot controlled study of the use of imipramine to reduce myotonia. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 1989;68:215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Milner-Brown HS, Miller RG. Myotonic dystrophy: quantification of muscle weakness and myotonia and the effect of amitriptyline and exercise. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1990;71:983–987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grant R, Sutton DL, Behan PO, Ballantyne JP. Nifedipine in the treatment of myotonia in myotonic dystrophy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1987;50:199–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis I. Trial of diazepam in myotonia: a controlled clinical trial. Neurology 1966;16:831–836. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sugino M, Ohsawa N, Ito T, et al. A pilot study of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate in myotonic dystrophy. Neurology 1998;51:586–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Durelli L, Mutani R, Fassio F. The treatment of myotonia: evaluation of chronic oral taurine therapy. Neurology 1983;33:599–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Griggs RC, Moxley RT III, Riggs JE, Engel WK. Effects of acetazolamide on myotonia. Ann Neurol 1978;3:531–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ceccarelli M, Rossi B, Siciliano G, Calevro L, Tarantino E. Clinical and electrophysiological reports in a case of early onset myotonia congenita (Thomsen's disease) successfully treated with mexiletine. Acta Paediatr 1992;81:453–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson CE, Barohn RJ, Ptacek LJ. Paramyotonia congenita: abnormal short exercise test, and improvement after mexiletine therapy. Muscle Nerve 1994;17:763–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pouget J, Serratrice G. [Myotonia with muscular weakness corrected by exercise: the therapeutic effect of mexiletine.] Rev Neurol 1983;139:665–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ricker K, Haass A, Rudel R, Bohlen R, Mertens HG. Successful treatment of paramyotonia congenita (Eulenburg): muscle stiffness and weakness prevented by tocainide. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1980;43:268–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Streib EW. Successful treatment with tocainide of recessive generalized congenital myotonia. Ann Neurol 1986;19:501–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rawson NS, Harding SR, Malcolm E, Lueck L. Hospitalizations for aplastic anemia and agranulocytosis in Saskatchewan: incidence and associations with antecedent prescription drug use. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:1343–1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trip J, Drost G, van Engelen BGM, Faber CG. Drug treatment for myotonia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Griggs RC, Wood DS. Criteria for establishing the validity of genetic recombination in myotonic dystrophy. Neurology 1989;39:420–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Logigian EL, Blood CL, Dilek N, et al. Quantitative analysis of the “warm-up” phenomenon in myotonic dystrophy type 1. Muscle Nerve 2005;32:35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moxley RT, Logigian EL, Martens WB, et al. Computerized hand grip myometry reliably measures myotonia and muscle strength in myotonic dystrophy (DM1). Muscle Nerve 2007;36:320–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ravin A. Studies in dystrophica myotonia: III: experimental studies in myotonia. Arch Neurol Psychiatry 1940;43:649–681. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roden DM. Antiarrhythmic drugs. In: Brunton L, Parker J, Lazo K, eds. Goodman and Gillman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. New York: McGraw Hill Publishing; 2005;899–932. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shimizu W, Antzelevitch C. Sodium channel block with mexiletine is effective in reducing dispersion of repolarization and preventing torsade de pointes in LQT2 and LQT3 models of the long-QT syndrome. Circulation 1997;96:2038–2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jurkat-Rott K, Lehmann-Horn F. Human muscle voltage-gated ion channels and hereditary disease. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2001;1:280–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lehmann-Horn F, Jurkat-Rott K. Voltage-gated ion channels and hereditary disease. Physiol Rev 1999;79:1317–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cannon SC. Spectrum of sodium channel disturbances in the nondystrophic myotonias and periodic paralyses. Kidney Int 2000;57:772–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mohammadi B, Jurkat-Rott K, Alekov A, Dengler R, Bufler J, Lehmann-Horn F. Preferred mexiletine block of human sodium channels with IVS4 mutations and its pH-dependence. Pharmacogenet Genomics 2005;15:235–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takahashi MP, Cannon SC. Mexiletine block of disease-associated mutations in S6 segments of the human skeletal muscle Na(+) channel. J Physiol 2001;537:701–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang GK, Russell C, Wang SY. Mexiletine block of wild-type and inactivation-deficient human skeletal muscle hNav1.4 Na+ channels. J Physiol 2004;554:621–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Griggs RC, Davis RJ, Anderson DC, Dove JT. Cardiac conduction in myotonic dystrophy. Am J Med 1975;59:37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Campbell RW. Mexiletine. N Engl J Med 1987;316:29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.