Abstract

Disparities in teen pregnancy rates are explained by different rates of sexual activity and contraceptive use. Identifying other components of risk such as race/ethnicity and neighborhood can inform strategies for teen pregnancy prevention. Data from the 2005 and 2007 New York City Youth Risk Behavior Surveys were used to model demographic differences in odds of recent sexual activity and birth control use among black, white, and Hispanic public high school girls. Overall pregnancy risk was calculated using pregnancy risk index (PRI) methodology, which estimates probability of pregnancy based on current sexual activity and birth control method at last intercourse. Factors of race/ethnicity, grade level, age, borough, and school neighborhood were assessed. Whites reported lower rates of current sexual activity (23.4%) than blacks (35.4%) or Hispanics (32.7%), and had lower predicted pregnancy risk (PRI = 5.4% vs. 9.0% and 10.5%, respectively). Among sexually active females, hormonal contraception use rates were low in all groups (11.6% among whites, 7.8% among blacks, and 7.5% among Hispanics). Compared to white teens, much of the difference in PRI was attributable to poorer contraceptive use (19% among blacks and 50% among Hispanics). Significant differences in contraceptive use were also observed by school neighborhood after adjusting for age group and race/ethnicity. Interventions to reduce teen pregnancy among diverse populations should include messages promoting delayed sexual activity, condom use and use of highly effective birth control methods. Access to long-acting contraceptive methods must be expanded for all sexually active high school students.

Keywords: Adolescents, Contraception, Sexual behavior

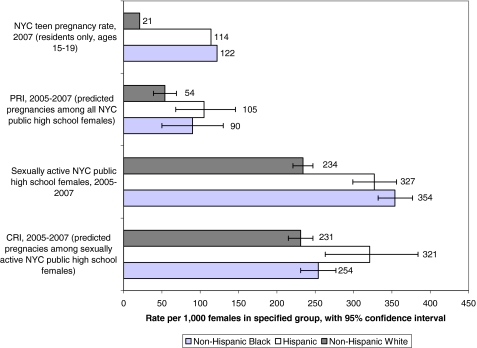

Teen pregnancy rates in New York City (NYC) are consistently higher than in the United States (US) overall, particularly among blacks and Hispanics and within poor neighborhoods. The latest national teen pregnancy rate for 2005 indicates that there are 71 pregnancies per 1,000 girls aged 15 to 19 each year,1 while the 2007 NYC rate for residents ages 15–19 was about 83 per 1,000.1 Within NYC, there are significant disparities in the teen pregnancy rate by race/ethnicity and neighborhood.2 In 2007, teen pregnancy rates among NYC residents were more than four times higher among NYC black (122/1,000) and Hispanic teens (114/1,000) than among white teens (21/1,000),1 and the city’s lowest teen pregnancy rate was in Staten Island (51/1,000),1 where 70% of the population is white and the poverty rate is only 10%. 3

In NYC, the highest rates of teen pregnancy are reported in three neighborhoods with a disproportionate burden of poverty and poor health, East and Central Harlem (in Manhattan) (133/1,000), North and Central Brooklyn (Bedford-Stuyvesant and Bushwick) (129/1,000), and the South Bronx (133/1,000).1 Poverty rates, as indicated by the 2000 US Census and NYC Department of City Planning, are similarly elevated in East and Central Harlem (37%) and North and Central Brooklyn (34%) compared with NYC overall (21%), as are the proportions of adults who did not graduate from high school (about 40% in the target neighborhoods vs. 29% citywide). The South Bronx target area has a poverty rate of more than 40%, and half of its adult residents did not graduate from high school.4 Prior research demonstrates that the rate of contraceptive use tends to be lower in more disadvantaged neighborhoods.5 Public high school teens in these NYC target areas are more likely to be sexually active than their peers in the rest of the city and the females are less likely to report contraceptive use.4

The relative contribution of sexual activity and contraceptive use to pregnancy risk among NYC teens is not known. We initially applied pregnancy risk index (PRI) methodology to decompose the risk of pregnancy into these two behavioral components.6–8 We apply the PRI here to estimate population-based differences in the components of pregnancy risk (i.e., sexual activity and contraceptive efficacy) by race/ethnicity and other selected demographic subgroups within an urban environment.

Methodology

Data Collection Instrument

The NYC Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) is implemented by the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) and the Department of Education (DOE) in conjunction with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The survey has been conducted biennially since 1997 to monitor health risk behaviors that contribute to the leading causes of mortality, morbidity, and social problems among youth in New York City. Beginning in 2005, the survey was designed to provide representative data on students who attend public school in the three neighborhoods in which the DOHMH focuses its efforts to reduce health disparities through District Public Health Offices in the South Bronx, East and Central Harlem, and North and Central Brooklyn.

Note that students may not reside within the neighborhood in which they attend school. The 2007 YRBS introduced a question on borough of residence. With the exception of Manhattan, most survey participants (87% or greater) reported that they lived in the same borough where they attended school. Overall, only 49% of Manhattan students lived in Manhattan and 69% of students in the East and Central Harlem target area lived in Manhattan. Detailed information on sampling, response weights, and weighting are published elsewhere.9,10

A total of 8,140 students in 87 public high schools completed the survey in 2005, and 9,080 students in 87 public high schools completed it in 2007.9,11 Special Education and English as a Second Language classes were excluded from the survey. Participating students completed a self-administered, anonymous, 99-item questionnaire that measured risk behaviors including tobacco, alcohol and drug use, unintentional injury and violence, sexual activity, diet, and physical activity. Study methods followed CDC guidelines for all state and federal YRBS surveys and are approved by the DOHMH and DOE Institutional Review Boards (IRB).9 Use of the data for this analysis was also approved by the Columbia University Medical Center IRB.

Study Population

This study combines data from the 2005 and 2007 NYC YRBS to gain sufficient sample size to enable small area estimates and multivariable modeling. We compared the 2005 and 2007 data sets and found no significant variation in patterns of sexual behavior or contraceptive use. We restricted our study sample (N = 7,435) to non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic white teen girls in grades 9 through 12, excluding students with missing data on age (N = 7). Participants without complete responses on the sexual behavior module [ever had sex, current sexual activity (among those who had ever had sex), use of condom at last sex, or use of other birth control at last sex] were excluded, resulting in a final sample size of 6,608. Response rates on the sexual behavior module among the sample varied significantly by race/ethnicity (92.8% of whites had complete data vs. 89.3% of Hispanics and 85.7% of blacks; chi square = 0.455, p = 0.001), but not by survey year (88.6% in 2005 and 87.8% in 2007; chi square = 7.492, p = 0.500).

Measures

Sexual activity and contraception Contraceptive use at last intercourse was defined only for girls who reported that they were currently sexually active (i.e., had sexual intercourse with one or more people during the past 3 months), thus reducing potential error due to poor recall.8,9 The NYC YRBS includes separate questions for condom use (used a condom during last sexual intercourse) and main birth control use at last intercourse [condom, pill, Depo-Provera (injectable birth control), withdrawal, other, no method, not sure].11 Due to limited sample size for some individual methods of contraception, we created a four-level birth control outcome (condom/no hormonal method, withdrawal/other method, any hormonal method, and no method/not sure) to obtain prevalence estimates of birth control type by demographic subgroup.We assigned a contraceptive failure rate (CFR) to each of 10 possible combinations of reported birth control methods based on published “typical use CFRs” from a national sample. In contrast to “perfect use” failure rates, typical use CFRs are estimated based on the percentage of average couples who experience an accidental pregnancy during the first year of initiating a method (not necessarily for the first time) if they do not stop using that method for any other reason: no method (85.0%), not sure (85.0%), withdrawal only (18.4%), condom only (17.4%), birth control pill only (8.7%), Depo-Provera/shot only (6.7%), all methods including other methods (12.4%), condom with other method (2.2%), birth control pill and condom (1.5%), condom and Depo-Provera/shot only (1.2%), and condom and withdrawal (3.2%).12–14 Failure rates for dual method use at last intercourse (pill and condom or injection and condom) were estimated by multiplying the method-specific failure rates for the two methods used.

Risk indices The CRI is a composite measure using behavioral data (i.e., prevalence of contraceptive methods used by a population group) combined with CFRs of specific contraceptive methods. The CRI summarizes the pregnancy risk for the sexually active proportion of the population by summing the product of each method-specific failure rate and the proportion of sexually active female adolescents using that method at last intercourse.15 In these calculations, non-use of contraception is considered a “method” with a specific risk of pregnancy. Thus,  , where x = each specific method.15The PRI is the product of two components: the percentage of the population currently sexually active and the contraceptive risk index (CRI). The PRI method has been validated using national Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) and vital statistics data to assess the source of declining pregnancy rates over time. Validation studies of the national YRBSS show no differences in item response bias by race/ethnicity on sexual behavior questions. Methodological issues associated with the PRI and CRI are more fully discussed elsewhere.6,8,15We present actual NYC teen pregnancy rates for 2007 that were calculated using counts of births and terminations (induced or spontaneous) based on certificates filed with the DOHMH.1 Only pregnancies among NYC resident teens ages 15–19 that occurred in NYC are included. The population denominator for actual pregnancy rates is the initial unchallenged US Census estimate for 2007.1

, where x = each specific method.15The PRI is the product of two components: the percentage of the population currently sexually active and the contraceptive risk index (CRI). The PRI method has been validated using national Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) and vital statistics data to assess the source of declining pregnancy rates over time. Validation studies of the national YRBSS show no differences in item response bias by race/ethnicity on sexual behavior questions. Methodological issues associated with the PRI and CRI are more fully discussed elsewhere.6,8,15We present actual NYC teen pregnancy rates for 2007 that were calculated using counts of births and terminations (induced or spontaneous) based on certificates filed with the DOHMH.1 Only pregnancies among NYC resident teens ages 15–19 that occurred in NYC are included. The population denominator for actual pregnancy rates is the initial unchallenged US Census estimate for 2007.1

Analysis

We first assessed demographic differences in the percentage of girls reporting recent sexual activity and their use of specific birth control methods. We used logistic regression to model odds of recent sexual activity and a generalized multinomial logit model to estimate odds of using condoms only, any hormonal method, or withdrawal/other method vs. no birth control/not sure at last sex. All multivariable models adjusted for race/ethnicity, grade level, and school neighborhood. Because NYC neighborhoods tend to vary by socioeconomic status (SES), school neighborhood was selected as a proxy for community-level SES. Information on components of SES, such as students’ household income, or education and employment status of their parent(s)/guardian(s), were not collected on the survey. To reduce multicollinearity in the multivariable models, we constructed an eight-level combined school borough–neighborhood variable. The geographic reference group for the eight-level variable is the South Bronx, as its pregnancy rates and poverty rate are consistently higher than those of other NYC counties and neighborhoods. We excluded age group from the multivariable models, since it was not significantly associated with the outcomes after controlling for grade level. Because of limited racial/ethnic variation within borough and neighborhood, we were not able to introduce interaction terms into any of the models.

We estimated CRI and PRI by race/ethnicity, grade level, age, borough, and neighborhood. Also, t tests were used to test for significance of between-group differences at the 0.05 level. Next, we decomposed the overall PRI into its component parts (sexual activity and contraceptive use) for demographic subgroups defined by age, grade, race/ethnicity, and school neighborhood. The between-group percentage of the difference between pregnancy risk due to lower rates of sexual activity (SA) was calculated as:  . Similarly, the percentage of the difference in pregnancy risk due to more effective contraceptive use was calculated as:

. Similarly, the percentage of the difference in pregnancy risk due to more effective contraceptive use was calculated as:  . We fit multivariable linear models to obtain adjusted parameter estimates for the associations between race/ethnicity and PRI/CRI, controlling for grade level and neighborhood.

. We fit multivariable linear models to obtain adjusted parameter estimates for the associations between race/ethnicity and PRI/CRI, controlling for grade level and neighborhood.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SUDAAN software, which corrected for the clustering inherent in complex survey designs.16 All analyses were nested on survey year, school, and classroom. Standard errors and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using a first-order Taylor series.16 Relative standard errors (RSE) were calculated for means and percentages. Estimates with RSEs >30% are noted as unreliable. Multivariable models were estimated using the LOGISTIC, MULTILOG, and REGRESS procedures.17

Results

Approximately one third of the total sample of public high school girls reported having had sex in the 3 months prior to the survey (32.6%). The percentage of teen girls who reported current sexual activity varied significantly (p < 0.05) by race/ethnicity, age, and grade level (Table 1). Black students were most likely to be currently sexually active (35.4%), followed by Hispanics (32.7%) and whites (23.4%). The proportion of students who were currently sexually active increased with age and grade level. They were highest among female students aged 18 and up (59.6%) and 12th graders (48.3%), and lowest among students under age 15 (16.8%) and 9th graders (22.4%). Students in North and Central Brooklyn reported higher rates of current sexual activity than those in the South Bronx (reference group) (40.4% vs. 32.8%).

Table 1.

Sexual activity by race/ethnicity, grade level, and District Public Health Office neighborhood

| Percent sexually active in 3 months prior to survey | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| N | Weighted % | 95% CI | |

| Race/ethnicity** | |||

| White (ref) | 1,078 | 23.4 | (19.7–27.5) |

| Black | 2,192 | 35.4* | (29.6–41.7) |

| Hispanic | 3,338 | 32.7* | (29.9–35.6) |

| Age** | |||

| Under 15 | 971 | 16.8* | (13.0–21.3) |

| 15 (ref) | 1,743 | 25.4 | (21.4–30.0) |

| 16 | 1,852 | 35.4* | (31.2–39.8) |

| 17 | 1,478 | 41.9* | (37.4–46.6) |

| 18+ | 564 | 59.6* | (49.9–68.6) |

| Grade level** | |||

| 9 | 1,831 | 22.4* | (18.1–25.1) |

| 10 | 1,827 | 32.2* | (28.3–36.3) |

| 11 | 1,771 | 37.0* | (32.3–41.9) |

| 12 (ref) | 1,179 | 48.3 | (40.5–56.2) |

| School neighborhood** | |||

| South Bronx (ref) | 876 | 32.8 | (28.0–38.0) |

| Bedford-Stuyvesant and Bushwick (Brooklyn) | 1,029 | 40.4* | (36.1–44.9) |

| East and Central Harlem (Manhattan) | 1,114 | 33.9 | (30.4–37.7) |

| Rest of Bronx | 590 | 40.2 | (33.6–47.2) |

| Rest of Brooklyn | 416 | 27.6 | (18.7–38.7) |

| Rest of Manhattan | 558 | 33.5 | (29.2–38) |

| Queens | 782 | 31.6 | (27.5–36.1) |

| Staten Island | 1,243 | 29.6 | (26.1–33.3) |

| Total | 6,608 | 32.6 | (29.5–36) |

*p < 0.05, significantly different from the reference group, t test; **p < 0.05, chi-square test

Self-reported contraceptive use varied significantly by race/ethnicity, grade level, and school neighborhood (Table 2). Compared with whites, Hispanics were more likely to report using no method or “not sure” (23.0% vs. 10.7%) the last time they had sex. Use of hormonal contraception was low in all groups of sexually active females (11.6% among whites, 7.8% among blacks, and 7.5% among Hispanics). Ninth (67.4%) and 10th (67.4%) graders were more likely to report condom use than 12th graders (55.3%), but less likely to report withdrawal/other method. Almost 18% of 12th-grade females reported using “withdrawal” or “some other method,” compared with 9.5% of 9th graders and 6.1% of 10th graders.

Table 2.

Birth control at last intercourse by demographic subgroup

| N | Condom/no hormonal method | Withdrawal/other | Any hormonal | No method/not sure | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted % | 95% CI | Weighted % | 95% CI | Weighted % | 95% CI | Weighted % | 95% CI | ||

| Race/ethnicity** | |||||||||

| White (ref) | 277 | 63.2 | (55.3–70.4) | 14.4 | (9.6–21.1) | 11.6 | (7.4–17.9) | 10.7 | (6.4–17.4) |

| Black | 792 | 66.7 | (61.5–71.5) | 11.6 | (8.1–16.3) | 7.8 | (4.8–12.4) | 13.9 | (10.9–17.5) |

| Hispanic | 1,206 | 57 | (52.3–61.6) | 12.2 | (9.5–15.5) | 7.5 | (5.5–10) | 23.3* | (20.2–26.8) |

| Grade level** | |||||||||

| 9th | 417 | 67.4* | (56.3–76.8) | 9.9* | (6.1–15.8) | 6.8 | (4–11.5) | 15.9 | (10.7–23) |

| 10th | 562 | 67.4* | (61–73.2) | 6.1* | (3.9–9.6) | 7.3 | (4.6–11.6) | 19.1 | (15–24.1) |

| 11th | 709 | 58.3 | (51.5–64.8) | 15.4 | (11.5–20.3) | 8.3 | (5.1–13.1) | 18.1 | (14.3–22.5) |

| 12th (ref) | 587 | 55.3 | (49.7–60.9) | 17.5 | (12.9–23.2) | 9.4 | (5.7–15.1) | 17.8 | (13.8–22.8) |

| School neighborhood** | |||||||||

| South Bronx (ref) | 302 | 54.1 | (48.5–59.6) | 9.5 | (6.6–13.5) | 10.9 | (7.4–15.7) | 25.5 | (20.9–30.7) |

| Bedford-Stuyvesant and Bushwick (Brooklyn) | 414 | 61.6* | (57.3–65.7) | 9.7 | (5.9–15.6) | 5.9 | (3.3–10.3) | 22.8 | (17.1–29.6) |

| East and Central Harlem (Manhattan) | 389 | 66.2* | (60.1–71.8) | 9.5 | (7–12.8) | 10.5 | (8–13.8) | 13.8* | (10–18.7) |

| Rest of Bronx | 216 | 74.2* | (66–81.1) | 6.4a | (3.0–13.2) | 4.9* | (2.7–8.6) | 14.6* | (10.4–20) |

| Rest of Brooklyn | 130 | 63.3 | (54.5–71.2) | 10.3a | (5.2–19.5) | 9.9a | (4.7–19.7) | 16.5* | (12.6–21.3) |

| Rest of Manhattan | 186 | 58.0 | (46.6–68.6) | 12.9 | (8.2–19.8) | 10.9 | (7–16.4) | 18.2* | (13.8–23.6) |

| Queens | 272 | 56.5 | (48.5–64.1) | 18.7* | (12.1–27.9) | 5.1* | (2.9–9.1) | 19.6 | (14.3–26.4) |

| Staten Island | 366 | 63.6* | (57.8–69.1) | 15.6* | (11.4–20.9) | 8.4 | (5.7–12.3) | 12.4* | (9.1–16.8) |

| Total | 2,275 | 62.0 | (58.5–65.5) | 12.1 | (9.8–14.9) | 8.0 | (6.3–10.2) | 17.9 | (15.8–20.1) |

*p < 0.05, significantly different from the reference group, t test; **p < 0.05, chi-square test

aEstimate should be interpreted with caution. Estimate’s relative standard error (a measure of estimate precision) is greater than 30%

Sexually active female students in the South Bronx (25.5%) were more likely to report using no birth control the last time they had sex than students who attended school in the rest of the Bronx (14.6%), East and Central Harlem (13.8%), Brooklyn [excluding the Bedford-Stuyvesant (North Brooklyn) and Bushwick (Central Brooklyn) target neighborhood] (18.2%), and Staten Island (12.4%). South Bronx female students were less likely to report condom use (54.5%) than students in the rest of the Bronx (74.2%), East and Central Harlem (66.2%), and Staten Island (63.6%) (Table 2). Few students citywide reported using a hormonal method (8.0%); this rate was higher in the South Bronx (10.9%) than in the rest of the Bronx (4.9%) and Queens (5.1%).

The multinomial regression model estimated odds of reporting each of three types of birth control versus no method/not sure, adjusting for race/ethnicity, grade level, and school neighborhood. Both race/ethnicity and school neighborhood were significantly associated with birth control method (Table 3). Compared with whites, sexually active Hispanic female students were less likely to report use of condoms (adjusted odds ratio, 0.4), any hormonal method (0.3), or withdrawal/other methods (0.5). Significant school neighborhood differences were observed in odds of condom use. East and Central Harlem female students were significantly more likely to report condom use than girls who attended school in the South Bronx (adjusted odds ratio, 2.0), as were girls in the rest of the Bronx (2.2) and Staten Island (1.8).

Table 3.

Adjusted odds of reporting specific birth control methods at last intercourse by demographic subgroup, multinomial logistic regression

| N | Condom/no hormonal method vs. no method or not sure | Any hormonal method vs. no method or not sure | Withdrawal/“other” vs. no method or not sure | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | Adjusted OR | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | Adjusted OR | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | ||

| Race/ethnicity** | ||||||||||

| White | 277 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Black | 792 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 1.8 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 2.2 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 2.1 |

| Hispanic | 1,206 | 0.4* | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.3* | 0.1 | 0.9 | 0.5* | 0.2 | 1.0 |

| Grade level** | ||||||||||

| 9th | 417 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 2.8 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 2.4 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 1.6 |

| 10th | 562 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 1.7 | 0.3* | 0.2 | 0.6 |

| 11th | 706 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 1.7 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 2.1 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 1.6 |

| 12th | 587 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| School neighborhood** | ||||||||||

| South Bronx (ref) | 302 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Bedford-Stuyvesant and Bushwick (Brooklyn) | 414 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 2.4 |

| East and Central Harlem (Manhattan) | 389 | 2.0* | 1.3 | 3.2 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 2.9 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 3.2 |

| Rest of Bronx | 216 | 2.2* | 1.4 | 3.6 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 3.0 |

| Rest of Brooklyn | 130 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 2.5 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 2.6 |

| Rest of Manhattan | 186 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 2.4 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 3.7 |

| Queens | 272 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 1.8 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 1.2 | 2.2* | 1.0 | 4.9 |

| Staten Island | 366 | 1.8* | 1.0 | 3.0 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 1.0 | 4.9 |

*p < 0.05, t test; **p < 0.05, adjusted Wald F

The CRI, which represents the predicted annual number of pregnancies per 100 sexually active public high school females, varied significantly by race/ethnicity and school neighborhood (Table 4). Hispanics (32.1) had a significantly higher CRI than whites (23.1), suggesting that sexually active Hispanic girls used less effective contraception overall than whites. Teens attending school in the South Bronx had a significantly higher CRI (32.7) than the rest of the Bronx (26.5), East and Central Harlem (25.1), Brooklyn (excluding the Bedford-Stuyvesant and Bushwick target neighborhood) (26.8), and Staten Island (24.8). CRI did not differ significantly by age or grade level. In the multivariable model including grade level, race/ethnicity, and school neighborhood, Hispanics still had a significantly higher CRI than whites (beta, 8.98, p < 0.001; results not shown), and the South Bronx school neighborhood still had a significantly higher CRI than the rest of the Bronx (beta, −5.60, p = 0.025) and East/Central Harlem (−6.39, p = 0.008; data not shown).

Table 4.

Pregnancy risk scores by race/ethnicity, grade level, school borough, and school neighborhood

| Contraceptive risk index | Pregnancy risk index | Deconstructed differences in pregnancy risk indices | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Weighted mean | 95% CI | N | Weighted mean | 95% CI | % from sexual activity | % from contraception | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| White (ref) | 277 | 23.1 | (19.1–27.1) | 1,078 | 5.4 | (3.9–6.9) | Ref | Ref |

| Black | 792 | 25.4 | (23.1–27.7) | 2,192 | 9.0* | (7.4–10.6) | 81% | 19% |

| Hispanic | 1,206 | 32.1* | (29.9–34.4) | 3,338 | 10.5* | (9.2–11.8) | 50% | 50% |

| Under 15 | 165 | 30.2 | (23.7–36.7) | 971 | 5.1 | (3.2–6.9) | – | – |

| 15 (ref) | 460 | 28.7 | (25.1–32.2) | 1,743 | 7.3 | (5.6–9) | Ref | Ref |

| 16 | 662 | 27 | (24.7–29.4) | 1,852 | 9.6* | (8.2–11) | 100% | 0% |

| 17 | 675 | 28.4 | (25.2–31.5) | 1,478 | 11.9* | (10–13.8) | 100% | 0% |

| 18+ | 313 | 28.3 | (24.8–31.8) | 564 | 16.9* | (13.7–20) | 100% | 0% |

| Grade level | ||||||||

| 9 | 417 | 27.2 | (23.1–31.3) | 1,831 | 5.8* | (4.4–7.3) | 96% | 4% |

| 10 | 562 | 29.2 | (26.1–32.2) | 1,827 | 9.4* | (7.8–11) | 96% | 4% |

| 11 | 709 | 28.2 | (25.4–31.1) | 1,771 | 10.4* | (9–11.9) | 100% | 0% |

| 12 (ref) | 587 | 28 | (24.8–31.3) | 1,179 | 13.5 | (10.9–16.2) | Ref | Ref |

| School neighborhood | ||||||||

| South Bronx (ref) | 302 | 33 | (29.3–36.6) | 876 | 10.8 | (8.2–13.4) | Ref | Ref |

| Bedford-Stuyvesant and Bushwick (Brooklyn) | 414 | 31.6 | (27.5–35.7) | 1,029 | 12.8 | (10.2–15.4) | – | – |

| East and Central Harlem (Manhattan) | 389 | 25.1* | (22–28.1) | 1,114 | 8.5 | (7–10) | – | – |

| Rest of Bronx | 216 | 26.5* | (23.2–29.8) | 590 | 10.7 | (8.6–12.7) | – | – |

| Rest of Brooklyn | 130 | 26.8* | (24.1–29.5) | 416 | 7.4 | (4.5–10.3) | – | – |

| Rest of Manhattan | 186 | 28.5 | (25.2–31.7) | 558 | 9.5 | (7.9–11.2) | – | – |

| Queens | 272 | 29.7 | (25.4–34) | 782 | 9.4 | (7.9–10.9) | – | – |

| Staten Island | 366 | 24.8* | (22.1–27.4) | 1,243 | 7.3* | (6.1–8.6) | 26% | 74% |

| Total | 2,275 | 28.2 | (26.8–29.7) | 6,608 | 9.2 | (8.2–10.3) | ||

*p < 0.05, significantly different from the reference group, t test

The PRI, which represents the predicted annual number of pregnancies per 100 public high school females, varied significantly by race/ethnicity, school neighborhood, age, and grade level (Table 4). The highest PRI score was observed among Hispanics (10.5), followed by blacks (9.0) and whites (5.4). Fifty percent of the difference in PRI between Hispanic and white teens and 19% of the difference in PRI between black and white teens were attributable to less effective contraception. Differences in PRI were also observed by school neighborhood. PRI was significantly lower in Staten Island (7.3) than in the South Bronx (10.7). Seventy four percent of this neighborhood difference was attributable to more effective contraceptive use. Virtually all the observed difference in PRI by age and grade level was attributable to higher rates of self-reported sexual activity. Unlike CRI, overall PRI did not vary by school neighborhood after adjusting for grade and race/ethnicity. In the multivariable model Hispanics (beta, 4.67, p < 0.001) and blacks (3.13, p < 0.007) had a higher predicted PRI than whites (results not shown). PRI also increased significantly by grade level: 12th-grade girls had significantly higher PRI than girls in the 9th grade (beta, −8.09, p < 0.001), 10th grade (−4.39, p = 0.002), and 11th grade (−3.22, p = 0.033).

Figure 1 displays the 2007 NYC resident teen pregnancy rates for white, black, and Hispanic teen girls compared with our YRBS-based estimates of PRI and its components, recent sexual activity and CRI. The estimated PRI for Hispanic public high school girls (105/1,000; 95% CI = 92–118/1,000) was similar to the actual pregnancy rate for NYC Hispanic teens (114/1,000). The estimated PRI for blacks was somewhat lower than the actual pregnancy rate (90/1,000; 95% CI = 74–106/1,000 versus 122/1,000), while the estimated PRI for whites was more than twice as high as the actual pregnancy rate (54/1,000; 95% CI = 39–69/1,000 versus 21/1,000).

FIGURE 1.

Rates per 1,000: NYC resident teen pregnancies, pregnancy risk index, sexual activity, and contraceptive risk index, by race/ethnicity.

Whites had significantly lower rates of self-reported current sexual activity and PRI, as well as actual pregnancy rates, compared with blacks and Hispanics. CRI among sexually active Hispanic teen girls, based on self-reported contraceptive use at last intercourse, was markedly higher than among blacks, while both PRI and actual pregnancy rates were similar between these two groups. This pattern further suggests that elevated rates of teen pregnancy among Hispanics compared with rates in whites are attributable to poorer contraceptive use.

Discussion

Our analysis demonstrates independent racial/ethnic and school neighborhood variation in the components of pregnancy risk among NYC public high school students. Both race/ethnicity and school neighborhood were significantly associated with differences in contraceptive use. Black and Hispanic females had greater overall pregnancy risk (PRI) compared with whites. The difference in PRI between blacks and whites was mainly attributable to higher rates of sexual activity, while the difference between Hispanics and whites was mainly attributable to less contraceptive use among sexually active girls. Our multivariable analyses showed that attending school in the South Bronx, a predominantly Hispanic neighborhood characterized by high rates of poverty, was significantly associated with increased contraceptive risk (CRI), after controlling for race/ethnicity. This suggests that the observed neighborhood disparity in teen pregnancy rates is not entirely attributable to the high concentration of Hispanic teen girls.

As our neighborhood context and race/ethnicity variables are highly correlated, we could not statistically model interactions between race/ethnicity and school neighborhood. Nevertheless, the associations we observed in our multivariable models offer evidence that both race/ethnicity and school neighborhood independently influence the risk of pregnancy. There is a growing body of literature suggesting that when teens live in poor communities with less advantage and opportunity and more disorganization, they are more likely to engage in sex at an earlier age and to become pregnant.18 This finding is supported by data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health that indicated neighborhood context as a significant factor in differences in rates of sexual initiation, after controlling for family income, parental education, race/ethnicity, age, and family structure.19 Qualitative studies within financially depressed neighborhoods have linked teens’ decisions not to use contraception to feelings of hopelessness or perceived lack of personal opportunity for the future.20,21 This research is consistent with our finding of increased pregnancy risk within high need neighborhoods, after controlling for race/ethnicity.

Racial/ethnic differences in expectations and motivations to have sex have been observed as early as middle school. A study of students in the Bronx showed that Hispanic 6th, 7th, and 8th graders felt more strongly than blacks that it is best to wait until marriage to have sex, and fewer black students than Hispanics believed that having sex would result in a “bad reputation.”22 A study of Baltimore teens found that preventing pregnancy was the driving force for contraceptive use among white teens, while Mexican-American and African-American teens described motivation to use condoms as protection against an STD, particularly HIV/AIDS.23 If teen girls are not specifically motivated to prevent a pregnancy, use of condoms may lapse when there is no perceived risk of contracting an STI.

Limitations

Our study has a number of limitations. First, the YRBS includes only a limited number of sexual activity and contraceptive questions. Therefore, the difference in pregnancy risk between blacks and whites and between Hispanics and whites may be due in part to unmeasured differences in frequency of sexual activity or consistency of contraceptive use. If these factors vary systematically across risk groups, then CRI estimates could be biased. For example, if one group has sex less frequently than another, its CRI would be overestimated relative to groups that have sex more frequently. Their proportion of pregnancy risk attributable to contraceptive failure would similarly be overestimated.

A second limitation, also related to the data collected on the YRBS, is that our use of school neighborhood as a proxy for home residence is imperfect. Students may choose to attend magnet schools or other specialized high schools outside their home neighborhood. As described above, students attending sampled schools in Manhattan were more likely than other students to reside in another borough. Misclassification of neighborhood residence potentially reduced our ability to detect associations between neighborhood and pregnancy risk, but significant associations were observed nonetheless.

A third limitation is that the findings are generalizable only to NYC public school students and not all NYC teens. Unlike some other localities, the NYC YRBS does not survey private schools. Students who have dropped out are, by definition, not in the survey, and students with poor attendance are less likely to be in the sample. We noted that there is more than a fivefold difference in actual pregnancy rates among white versus black and Hispanic NYC teens, while the PRI for white public high school students was half that of blacks and Hispanics. Race/ethnic disparities in school enrollment among NYC teens suggest that the pregnancy risk indices presented here are less representative of white NYC teens overall than of black and Hispanic teens. According to 2007 US Census estimates, only 50% of NYC whites ages 15–19 were enrolled in public school, compared to 74% of Hispanics and 75% of blacks.24 In 2007, white NYC teens ages 15–19 were more likely to be enrolled in private schools (40%) than blacks (11%) and Hispanics (10%) and less likely to be out of school (10% of whites vs. 15% of blacks and 16% of Hispanics).24 While the exclusion of private school, special education, and out-of-school students from the YRBS survey limits its generalizability, we know of no single population-level dataset that includes data on behavioral risk for both in-school and out-of-school teens. A separate survey with an appropriate methodology for reaching out-of-school teens would be needed to complement YRBS.

Despite these limitations, the YRBS is a unique source of data for obtaining population-based estimates of pregnancy risk at the local level. While the National Survey of Family Growth provides a more detailed picture of teen sexual activity over a 12-month period, these data are not representative at the state or local level and cannot be used to assess neighborhood-level differences.

Conclusions

Rates of hormonal contraception were low across all three racial/ethnic groups, and access to the pill and other long-acting methods of contraception must be expanded for all sexually active students. Significant differences in current sexual activity and contraceptive use across racial/ethnic and neighborhoods call for multifaceted approaches to teen pregnancy prevention. For example, compared with white students, Hispanic teens in NYC appear to be at greater risk of pregnancy because of less effective contraceptive use. Hispanic teen girls and girls who attended school in the South Bronx (a predominantly Hispanic, high-poverty neighborhood) were less likely to use condoms or other methods of contraception than other sexually active teens.

Due to its diversity, New York City is uniquely suited to this analysis of variation in pregnancy risk across racial/ethnic groups and within geographic areas with high concentrations of poverty. The PRI methodology, in conjunction with local YRBS data, may be useful to other localities to identify differences in the components of pregnancy risk between racial/ethnic groups and neighborhoods, and thereby help drive teen pregnancy prevention activities.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Katharine H. McVeigh, Joseph R. Egger, Jennifer Norton, and the Data Unit for preparation of the 2005–2007 analytic data set; Aviva G. Schwarz for assistance with data analysis; Dimitra Assimoglou for contributing to the literature review; Bonnie D. Kerker, Deborah Kaplan, and Lorna Thorpe for their review of this article; and Donna Eisenhower and the Survey Unit for data collection and survey methods.

References

- 1.Teen Pregnancy in New York City: 1997–2007. New York: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2009. Accessed on 17 February 2010. Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/ms/ms-nyctp-97-07.pdf

- 2.Schwartz S, Zimmerman R, Williams R, Li W, Betancourt F, Genovese R. Summary of Vital Statistics 2007, The City of New York: Bureau of Vital Statistics, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; 2008.

- 3.New York City Department of Small Business Services, Borough snapshot: Staten Island. Available at: www.nyc.gov/html/sbs/wib/downloads/pdf/borough_snapshot_si.pdf. Accessed on 3/26/2009.

- 4.Noyes P, Alberti P, Ghai N. Health Behaviors among Youth in East and Central Harlem, Bedford-Stuyvesant and Bushwick, and the South Bronx. New York, NY: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; 2008.

- 5.Cubbin C, Santelli J, Brindis CD, Braveman P. Neighborhood context and sexual behaviors among adolescents: findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2005;37(3):125–134. doi: 10.1363/3712505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santelli JS, Abma J, Ventura S, et al. Can changes in sexual behaviors among high school students explain the decline in teen pregnancy rates in the 1990s? J Adolesc Health. 2004;35(2):80–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santelli JS, Lindberg L, Singh S. Trends in adolescent sexual experience, contraceptive use, and pregnancy risk, 1995 and 2002. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38(2):156–157. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santelli JS, Morrow B, Anderson JE, Lindberg L. Contraceptive use and pregnancy risk among U.S. high school students, 1991–2003. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38(2):156. doi: 10.1363/psrh.38.106.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Comprehensive YRBS Methods Report: Bureau of Epidemiology Services Survey Unit, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; 2008.

- 10.Brener ND, Kann L, Kinchen SA, et al. Methodology of the youth risk behavior surveillance system. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2004;53(RR-12):1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Bureau of Epidemiology Services, Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/episrv/episrv-youthriskbehavior.shtml. Accessed on 3/26/2009.

- 12.Kost K, Singh S, Vaughan B, Trussell J, Bankole A. Estimates of contraceptive failure from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. Contraception. 2008;77(1):10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ranjit N, Bankole A, Darroch JE, Singh S. Contraceptive failure in the first two years of use: differences across socioeconomic subgroups. Fam Plann Perspect. 2001;33(1):19–27. doi: 10.2307/2673738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trussell J. Contraceptive efficacy. In: Hatcher R, Trussell J, Nelso A, Cates W, Stewart F, Kowel D, editors. Contraceptive Technology: Nineteenth Revised Edition. New York: Ardent Media; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santelli JS, Lindberg LD, Finer LB, Singh S. Explaining recent declines in adolescent pregnancy in the United States: the contribution of abstinence and improved contraceptive use. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):150–156. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.089169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaw B, Barnswell B, Beiler G. SUDAAN User's Manual: Software for Analysis of Correlated Data. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 17.RTI. Sudaan User's Manual, Release 8.0. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2001.

- 18.Kirby D. The impact of schools and school programs upon adolescent sexual behavior. J Sex Res. 2002;39(1):27–33. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cubbin C, Braveman PA, Marchi KS, Chavez GF, Santelli JS, Gilbert BJ. Socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparities in unintended pregnancy among postpartum women in California. Matern Child Health J. 2002;6(4):237–246. doi: 10.1023/A:1021158016268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilliam ML. Providers' perspectives on minority adolescent contraceptive behaviors: a focus group approach. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(4 Suppl):16S. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilliam ML, Warden MM, Tapia B. Young Latinas recall contraceptive use before and after pregnancy: a focus group study. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2004;17(4):279–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guilamo-Ramos V, Jaccard J, Dittus P, Bouris A, Holloway I, Casillas E. Adolescent expectancies, parent–adolescent communication and intentions to have sexual intercourse among inner-city, middle school youth. Ann Behav Med. 2007;34(1):56–66. doi: 10.1007/BF02879921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sugland BW, Wilder KJ, Chandra A. Sex, Pregnancy and Contraception: a Report of Focus Group Discussions with Adolescents. Washington: Child Trends; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruggles S, Sobek M, Alexander T, Fitch CA, Goeken R, Hall PK, King M, Ronnander C. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 4.0 [Machine-readable database]. Minneapolis, MN: Minnesota Population Center [producer and distributor], 2009 [Accessed on 17 February 2010; available at http://usa.ipums.org/usa/].