Abstract

Two different mixture synthesis routes have been used to make the four stereoisomers of petrocortyne A. A first quick and dirty route provided a mixture of the four isomers in non-selective fashion. Mosher and 2-naphthylmethoxyacetic acid (NMA) ester methods were developed to identify the components, and the mixture was partially resolved on analytical chiral HPLC to give the two pure enantiomers of petrocortyne A and the racemate of its diastereomer. A second fluorous mixture synthesis produced all four isomers of petrocortyne A in individual pure form. Comparison of spectra of Mosher derivatives of the synthetic isomers with two supposedly different natural products showed that both natural samples were instead identical and had the (3S,14S) configuration. Likewise, petrocortynes B, D and F–H are (3S,14S) and petrocortyne D is (3R,14S). Having access to all possible candidate isomers of both petrocortyne A and its Mosher derivatives provided a secure structure assignment not so much because one of the isomers matched the natural product, but because all of the other isomers did not.

Introduction

Marine sponges are rich sources of biologically active natural products of a myriad of different structures.1 The genus Petrosia, for example, produces all sorts of long-chain polyacetylene natural products, including petrocortynes, petroformynes, and petrosiacetylenes.2 These natural products exhibit diverse biological activities including antimicrobial, antitumor, antiviral and antifungal effects.3 The compounds typically consist of a linear carbon backbone of 30 to 46 carbons interspersed with functional groups including alkynes, E- and Z-alkenes, and hydroxy groups. There has been very little synthetic work directed such compounds.4

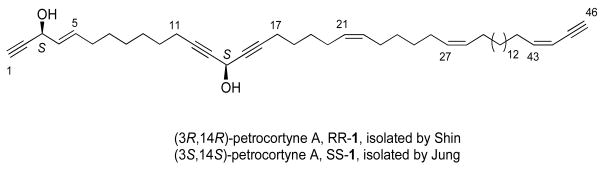

Petrocortyne A 1 is a representative natural product of this class that was first described by Shin and coworkers.5 Fractionation and purification of a 5.5 kg Petrosia sp. sample collected in 1994 from Korean waters of Komun Island provided 70 mg of a compound assigned as (3R,14R)-petrocortyne A (Figure 1). The constitution of the sample was assigned by a battery of spectroscopic methods. The 46-carbon chain features a dialkynylol unit (C12-C16) and an enynol unit (C1-C5) that are common in other petrocortynes. The two remote stereocenters at C3 and C14 were treated independently and their configurations were assigned by the “advanced Mosher ester” method.6 The sample had a modest inhibitory effect on the enzyme phospholipase A2 (PLA2) (31% at 50 μg/mL).

Figure 1.

Proposed structures of petrocortyne A

On the heels of this work, Jung and coworkers reported fractionation and purification of a 14.5 kg Petrosia sp. sample collected in 1995 again off Komun Island.7 This provided an unspecified amount of petrocortyne A, whose NMR spectra were identical to those of the sample of Shin. But the advanced Mosher analysis of this sample suggested that it was the enantiomer, (3S,14S)-petrocortyne A. Jung’s petrocortyne A is a potent cytotoxic agent, and also exhibits significant anti-inflammatory and pro-aggregative effects at non-cytotoxic concentrations.8 Significant information about the cellular targets of petrocortyne is available.

Could the same class of sponge isolated from similar locations in different years really produce enantiomers of the same natural product? Or were one or even both of the structure assignments incorrect? These questions piqued our curiosity in the context of a program on assigning structures to natural products when two or more stereoisomers can reasonably be expected to have substantially identical spectra.9 Would the (3S,14S)/(3R,14R) pair of enantiomers exhibit the same spectra as the (3R,14S)/(3S,14R) pair? The pairs are syn/anti diastereomers, but the stereocenters are remote. If the spectra are the same, then how can the diastereomers be differentiated? And is the application of advanced Mosher analysis of petrocortynes a reliable tactic for assigning configurations?

We have recently communicated the finishing steps of a fluorous mixture synthesis of the petrocortyne isomers and validation of a new “short cut” Mosher method for assigning configurations of stereocenters in nearly symmetric environments.10 Here we report full details of two separate mixture syntheses of all four stereoisomers of petrocortyne A. The first “quick and dirty” synthesis produced a mixture of all four isomers that was partially separated. The second “fluorous mixture synthesis”11 provided all four individual pure isomers. Comparison of data from synthetic and natural samples and Mosher derivatives shows that the two natural samples are the same and that Jung’s assignment of (3S,14S)-petrocortyne A is correct. We validate use of Mosher esters to assign the difficult C14 stereocenter of petrocortynes, but at the same time we suggest that using 2-naphthylmethoxyacetic acid (NMA) esters is more convenient and reliable.

Results and Discussion

Mixture Synthesis Strategies

To confidently assign the structures of the extant petrocortyne A natural products, we set the goal of making individual, pure samples of all four stereoisomers of petrocortyne A for data collection and comparison with each other and with the natural samples. Dismissing the traditional approach to making all four stereoisomers by serial synthesis as too much effort, we simultaneously adopted two mixture synthesis approaches: a quick and dirty mixture synthesis and a fluorous mixture synthesis.

In the quick and dirty approach, we planned to make a single mixture of all four stereoisomers by using non-selective reactions to make each of the two stereocenters. Because the two stereocenters are remote, we reasoned that we could make believe that this mixture of true stereoisomers was a single compound during the body of the synthesis. In other words, we expected the mixtures not to resolve into diastereomeric components on chromatography, nor to give different resonances in the NMR spectra, etc. In the end, this expectation was realized.

All exercises in make believe have to end sooner or later, and this one ends at the final mixture sample containing the four isomers of petrocortyne A. This mixture has to be resolved (separated) into its four isomeric components, and the configurations of the four isomers have to be confidently assigned. The approach is comparable to a classical racemic synthesis followed by resolution and assignment of enantiomers, but with double the level of difficulty. We were confident that we could solve the identification problem on intermediate compounds made during the course of synthesis. However, as in racemic synthesis, the solution to the separation problem is difficult to anticipate because it is a trial and error process.

To complement the quick and dirty approach, we simultaneously pursued a fluorous mixture synthesis approach. This is somewhat more work because we must individually prepare each isomer and encode its configuration with a fluorous tag. But the bulk of the synthesis again occurs in a mixture mode, so considerable effort is spared. We again make believe that this mixture of quasiisomers (“quasi” because the compounds are not true isomers due to the fluorous tags12) is a single compound throughout much of the synthesis. But this time, we know that when the make believe ends we will be able to resolve the final mixture into its four individual components by demixing. And we will know which isomer is which by reading (identifying) the tags. In essence, a bit of extra work in the beginning could pay big dividends at the end because there are built-in solutions to the problems of separation and identification.

Assignment of Stereocenter Configurations by Derivatization

To start, we undertook a series of model studies with two overlapping aims. Recall that the configurations of the two samples of petrocortynes were assigned by the advanced Mosher method. First, to ensure that these assignments are correct, we needed to validate that method on samples of known configuration. Second, if successful, the quick and dirty synthesis was expected to provide isomers devoid of stereostructures, so the same model studies could serve as foundation for derivatization and assignment of the unidentified final products. In the end, this use was not needed because the fluorous mixture synthesis produced pure stereoisomers of defined configuration. But the studies nonetheless laid a solid foundation for using both Mosher6 and NMA13 ester derivatives to assign petrocortynes. In addition, we found a third use of the model studies that was not planned at the outset, which was to assign the configuration of one of the stereocenters during the fluorous mixture synthesis.

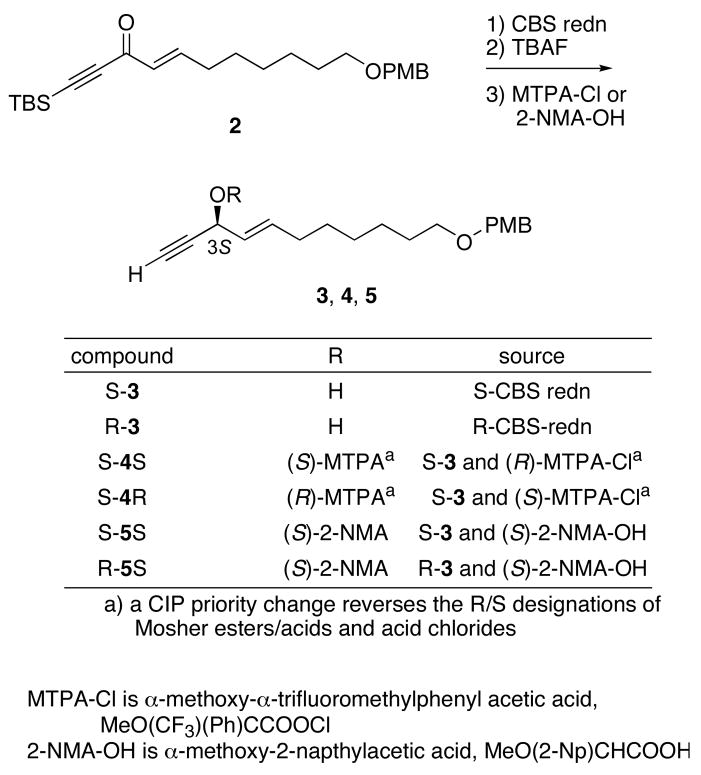

Model studies directed towards validating the Mosher method for assigning the configuration at C3 are summarized in Scheme 1. We later leveraged this work by using some of the intermediates to begin the fluorous mixture synthesis. Reduction of readily available alkyne 2 by the S-CBS reagent14 then desilylation with TBAF provided S-3 in 73% yield and 94% ee. Likewise, reduction by the R-CBS reagent provided R-3 in 70% yield and 93% ee. The configurations of these compounds can be confidently assigned from the prevailing model for CBS reductions, so they are suitable substrates to validate the advanced Mosher method.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of alkynyl alkenyl carbinol 3 and derived MTPA and 2-NMA esters

Alcohol S-3 was reacted with the R and S Mosher acid chlorides (MTPA-Cl = α-methoxy-α-trifluoromethylphenylacetic acid chloride).6 Integration of the 1H and 19F NMR spectra of the resulting samples S-4S15 and S-4R provided the indicated ees for the CBS reductions. The chemical shifts of pairs of resonances were then subtracted by the usual method (δS − δR),16 and the values obtained are shown in Table 1 in parts per million (ppm). The magnitudes of the differences are well outside experimental error, and the signs of the differences (negative to the left of the stereocenter as drawn, positive to the right) are as expected from the CBS model.

Table 1.

Assignment of the C3 stereocenter in Mosher (4) and NMA (5) esters

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| protons | 1 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| Δδ (δS-4S− δS-4R) ppm | 0.040 | −0.110 | −0.061 | −0.041 | −0.032 | −0.052 | −0.026 | −0.011 | 0.000 |

| Δδ (δR-5S − δS-5S) ppm | 0.114 | −0.199 | −0.183 | −0.152 | −0.183 | −0.118 | −0.092 | −0.054 | −0.027 |

During the model studies for the C14 stereocenter, we needed to make α-methoxy-2-naphthylacetic acid (NMA) esters to validate the Mosher results, so we also made the NMA esters with 3. We had available only the S-2-NMA acid, so this was reacted with both R and S-3 and the spectra of derivatives S-5S and R-5S were analyzed as usual. The results of appropriate subtraction are also shown in Table 1. The signs of the differences match the Mosher esters, as expected. But the magnitudes of the differences are much larger in the NMA esters, and the measurable differences extend further down the chain.

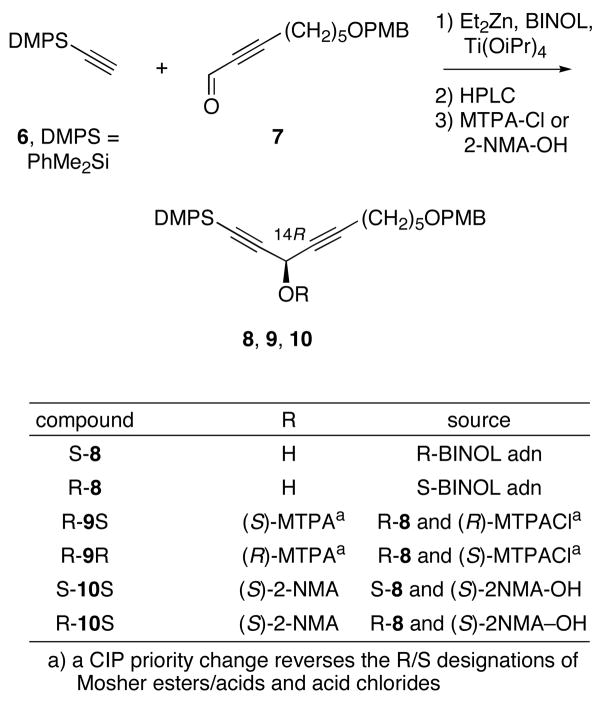

Model studies directed towards validating the Mosher method for assigning the configuration at C14 are summarized in Scheme 2. The use of Mosher esters to assign the C14 center is much more difficult than assigning C3 for two reasons. First, the nearest protons on both sides of the dialkynyl carbinol unit (C11-C17) are already three carbon atoms away from the stereocenter. Second, because of the quasisymmetry of these units, the propargyl protons on C11 and C17 are chemical shift equivalent in the natural product and related compounds. Making the Mosher ester separates the resonances by a very small amount.2 Prior to applying the Mosher method, the resonances have to be assigned, which is again difficult due to the quasi-symmetry. If the resonances are mis-assigned, then the stereocenter configuration will be mis-assigned.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of dialkynyl carbinol fragment 8 and derived MTPA and 2-NMA esters

To avoid any possible confusion about assigning pairs of propargylic methylene protons, we simply chose a model system with only one propargylic methylene group. Again, we planned to leverage the chemistry used to make the model later in the fluorous mixture synthesis. Both enantiomers of dialkynol 8 were prepared according to Pu by in situ generation of the zinc alkyne from 6, followed by addition of (R)- or (S)-BINOL, Ti(OiPr)4 and aldehyde 7.17 The enantiomers R-8 and S-8 were each obtained in 83% ee, in 64% and 70% isolated yield, respectively. Configurations were assigned by the Pu model. We found that the enantiomers were readily separable on a Chiralcel-OD HPLC column, so the ee of each sample was upgraded to >99% by preparative HPLC prior to derivatization.

We then made both MTPA and 2-NMA esters of 8 as described above. Again the pair of enantiomeric MTPA acid chlorides was reacted with R-9 to make the pair of Mosher esters R-9S and R-9R, while the single S-NMA acid was reacted with the pair of enantiomers S-8 and R-8 to give the NMA pair S-10S and R-10S. The results of the subtractions are summarized in Table 2. The expected signs of the differences are observed for both esters; however, the magnitudes are very different. For example, in the Mosher ester 9, the nearest protons to the stereocenter at C17 (propargylic position) show a difference of only 0.029 ppm. While this difference is outside the error of the measurement, it is still very small. Especially when one considers that the natural product will exhibit two resonances with this small separation that have to be unambiguously assigned.

Table 2.

Assignment of the C14 stereocenter in Mosher (9) and NMA (10) esters

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| protons | 1′ | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 1″ |

| Δδ(δR-9S − δR-9R) ppm | −0.023 | 0.029 | 0.023 | 0.024 | 0.011 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| Δδ(δS-10S − δR-10S) ppm | −0.151 | 0.158 | 0.175 | 0.152 | 0.103 | 0.064 | 0.022 |

The NMA esters 10 exhibit superior spectroscopic properties, with a chemical shift difference of 0.158 ppm for H17 and an even greater difference for H18 (0.175 ppm). Differences for H19 and H20 still exceed 0.1 ppm. The benzylic protons (H1″) ten atoms away from the stereocenter have about the same difference (0.022 ppm) in the 2-NMA esters as the nearest protons (H17) in the Mosher esters. No differences were measured for the PMB aromatic protons or methoxy group (H7″) of the NMA esters.

Taken together, these results validate the use of the Mosher method for assigning the configuration at C17, but at the same time show that the use of the NMA method will be both easier and more reliable. Since either ester can be used to assign C3, the 2-NMA ester is accordingly recommended as the single best derivative to simultaneously assign both stereocenters.

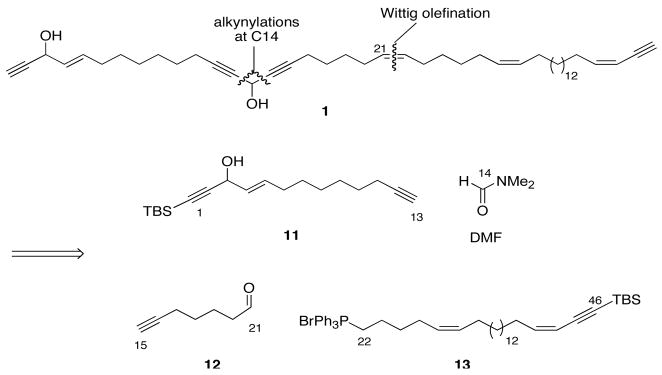

Diastereomer Mixture Synthesis

Having validated the advanced Mosher method and identified the even better NMA method for configuration assignment, we decided to undertake the non-selective synthesis of a mixture of all four diastereomers with the goal of resolving and identifying the components of the final mixture. The high level plan for this synthesis, shown in Figure 2, divides the molecule into one large component 13 (C22-C46), two medium-sized ones 11 (C1-C13) and 12 (C15-C21), and one small one. The small component is dimethylformamide, which provides the linchpin carbon (C14) to join the 1,4-dialkyne unit.

Figure 2.

Retrosynthetic plan for the synthesis of a mixture of true diastereomers of 1

Complete details of the fragment syntheses are provided in the Supporting Information. Briefly, 12 was made in two steps and 54% overall yield from 3-heptyn-1-ol (Scheme S2), while rac-11 was made in six steps and 34% overall yield from 3-nonyn-1-ol (Scheme S3). Finally, the large right-side fragment 13 was made in 10 steps from 16-hydroxyquindecanoic acid (Scheme S4).

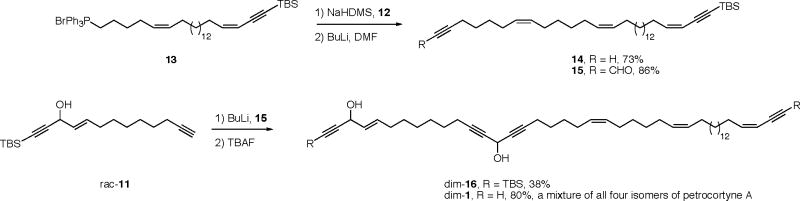

The fragment couplings and completion of the diastereomer mixture synthesis are summarized in Scheme 3. Coupling of 13 and 12 by a Wittig reaction under standard conditions provided the C21-Z isomer 14 in 73% yield. In turn, this was formylated with DMF to give aldehyde 15 in 86%. Deprotonation of fragment rac-11 followed by addition of aldehyde 15 and careful chromatography gave dim-16 in 38% yield, where the prefix “dim” stands for “diastereoisomer mixture”. Finally, desilylation with TBAF provides the final mixture of all four petrocortyne A isomers, dim-1. About 18 mg of this mixture was produced.

Scheme 3.

Fragment couplings and production of a mixture of the four stereoisomers of petrocortyne A.

Both samples dim-16 and dim-1 appeared to be single compounds by the usual means of spectroscopic (high field 1H and 13C NMR) and chromatographic (standard and reverse phase TLC) analysis. It is inconceivable that coupling of 11 and 15 provided a single isomer; instead, the pairs of diastereomers are simply not distinguishably different. Importantly, the spectroscopic data of dim-1 completely matched the data reported by both (R,R)-1 and (S,S)-1, so the synthesis confirms the constitution of petrocortyne A.

Left to secure is its configuration. Towards that end, upon injection into an analytical Chiralcel OD column (2% isopropanol/hexane), the sample of dim-1 was resolved into not four but three peaks in a ratio of about 1/2/1. We interpreted this chromatogram as showing that the four isomers were present in equal amounts; two isomers separated from the other two, which overlapped each other. This was later confirmed as described below.

At this juncture, the work on the fluorous mixture synthesis (see below) was well advanced and promised to soon provide all four pure isomers. Thus, the scan of other chiral separation methods was terminated and no derivatizations were attempted. In the end, the diastereomer mixture synthesis proved the constitution of petrocorytne A and showed that it was possible to resolve two of the four isomers with a Chiralcel OD column.

Fluorous Mixture Synthesis

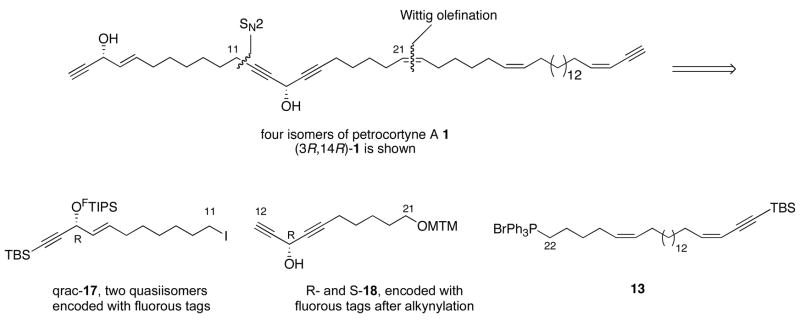

The strategy for the fluorous mixture synthesis, shown in Figure 3, is similar to the diastereomer mixture synthesis, with one important exception. To allow for generation of the C14 stereocenter by a Pu asymmetric addition with a silyl alkyne, we shifted the fragment coupling dissection away from C14 to the C11-C12 bond. This gives the same right-hand fragment 13 as above, the far-left fragment qrac-17 above, and the center-left fragment 18. These last fragments are closely related to 11 and 12 in Scheme 3. For the fluorous mixture synthesis, both fragments 17 and 18 have to be made in highly enantioenriched form, then tagged with different fluorous tags for later separation and identification. While the earlier model work used a PMB group on O22,18 this proved difficult to remove, so we changed to a methylthiomethyl (MTM) group.19

Figure 3.

Plan for the fluorous mixture synthesis

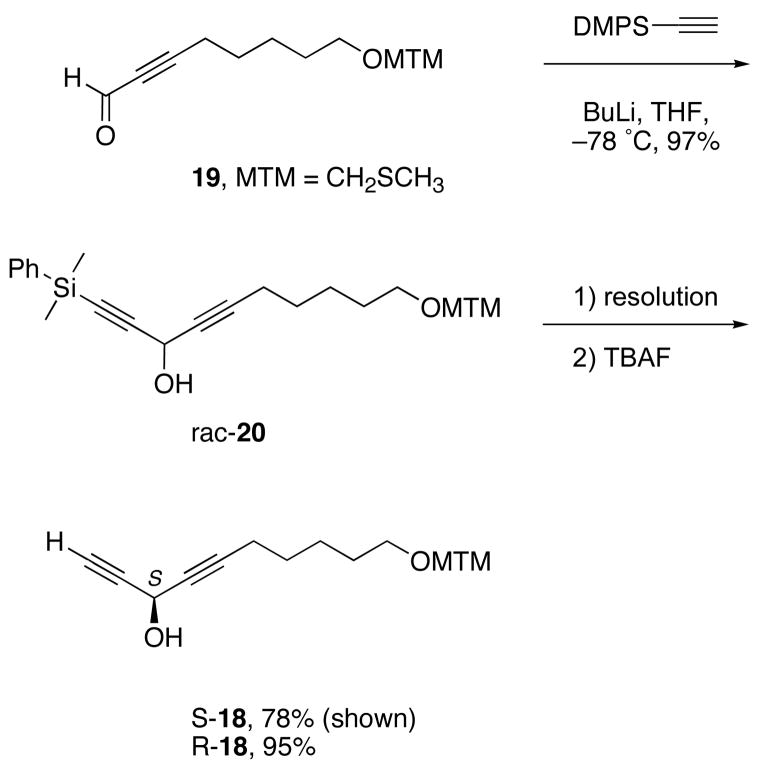

The synthesis of center-left fragment 18 is summarized in Scheme 4. Initially, we focused on Pu additions of several alkynes to aldehydes like 19. These results are summarized in the Supporting Information, Scheme S5. The observed ees of products like 20, while substantial (78–90%), did not meet our target levels of >95%. Enantiomeric impurities at this stage would produce diastereomer impurities downstream, and we did not know whether or how the impurities could be either separated or identified.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of alcohols R,S-18

In analyzing the ees from Pu reactions, we soon found that products like rac-20 were easily resolved on a Chiralcel-OD column. Thus, instead doing two asymmetric alkyne additions and upgrading the ees of those enantiomeric products, we simply made racemic 20 on gram scale and resolved it. The racemate was preparatively resolved to provide the first-eluting enantiomer R-18 in 47% yield and second-eluting enantiomer S-18 48% yield (combined yield, 97%). Both samples had ees ≥99% by chiral HPLC analysis. The configurations of 18 could be tentatively assigned by HPLC comparison to samples made by Pu alkynylation, and the assignments were confirmed by making NMA esters as above (see Supporting Information for details).

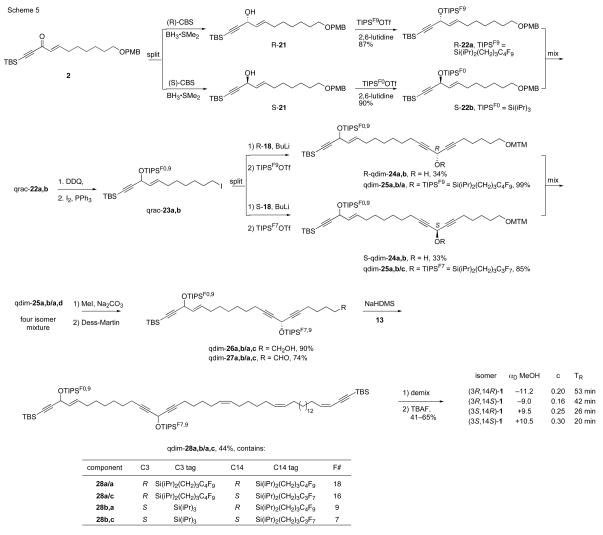

The fragment couplings and completion of the fluorous mixture synthesis are summarized in Scheme 5. To start, CBS reduction of ketone 22 by a procedure similar to that in Scheme 2 provided aklynyl alkenyl carbinols R- and S-21. Quasienantiomers R-22a and S-22b15 were individually prepared by tagging R-21 with C4F9(CH2)3Si(iPr)2OTf20 and S-21 with standard TIPSOTf. The resulting products were mixed in equal amounts to make qrac-22a,b. Removal of the PMB group followed by treatment of the resulting alcohol with iodine and triphenylphosphine gave iodide qrac-23a,b15 ready for coupling with the center-left fragment.

Scheme 5.

Fluorous mixture synthesis of petrocortyne isomers

In an initial dead-end approach, we tagged the enantiomers of left-center fragment 18 (Scheme 4) with two different silyl groups, but could not couple the resulting quasiracemate (not shown) with qrac-23a,b. Suspecting that this reaction failed because the protected dialkylcarbynol proton was deprotonated rather than (or in addition to) the terminal alkyne proton, we conspired to block this side reaction by conducting the coupling on a dianion derived from free alcohol 18. This revised sequence, shown in Scheme 5, has the same number of synthetic steps as the original plan, but since the coupling was placed before the tagging, we had to postpone the mixing. This results in conducting one extra reaction (two couplings instead of one).

Deprotonation of R-18 with two equivalents of BuLi provided a dianion that was coupled with qrac-23a,b. The resulting pair of quasidiastereomers (R-qdim 24a,b) was tagged with C4F9(CH2)3Si(iPr)2OTf to encode the configuration at C14 in qdim-25a,b/a15 with a perfluorobutyl group. Likewise, the pair of quasidiastereomers S-qdim-24a,b from reaction of qrac-23a,b with S-18 was encoded with the perfluoropropyl group from C3F7(CH2)3Si(iPr)2OTf to give qdim-25a,b/a,c. Mixing the pair of tagged products provided the first four-compound quasiisomer mixture, qdim-25a,b/a,c. Notice that even though both R stereocenters of qdim-25 are encoded with the same perfluorobutyl group (tag “a”), there is no redundancy in fluorine content of the final four products and the coding scheme is therefore unambiguous.21

Removal of the MTM group from 25 followed by Dess-Martin oxidation provided aldehyde qdim-27, which was then coupling with Wittig reagent 13 to provide qdim-28, now ready for demixing. Despite the highly convergent synthesis plan involving late introduction of stereocenters, the fluorous mixture synthesis route still saved fifteen reactions compared to the same route conducted in serial or parallel.

The quasiisomer mixture qdim-28 was readily demixed by preparative fluorous HPLC to provide the four underlying components in pure form. Unlike the spectra of true protected isomers dim-16 (Scheme 3), the NMR spectra of these four isomers were not identical. In addition to the obvious differences in the resonances originating from the different tags (TIPS and fluorous TIPS), the two isomers containing the standard TIPS groups had several small differences in resonances of backbone protons. Thus, the observed small differences emanated from the tag differences, not the stereocenter differences.

This conclusion was confirmed by removing the tags from the four quasiisomers 28 with TBAF to give the four isomers of petrocortyne A 1, this time in individual, pure form. The NMR spectra and chromatographic retention times of all the isomers on standard silica gel were the same, and were identical to four compound mixture qdim-1.

Importantly, the pure isomers could be partly differentiated in complementary ways by optical rotation and chiral HPLC. The optical rotations of the four isomers are shown in Scheme 5. Two pairs of diastereomers 1 (RR/RS and SS/SR) have rotations that are too close to differentiate in practice. So the for structure assignment purposes, the sign of the optical rotation can be used assign the configuration of C3, but no information is provided about C14. Contributions to rotation from remote stereocenters are often approximately additive,22 so at this wavelength the C14 stereocenter apparently contributes a negligible amount to the total rotation.

Given that two pairs of isomers have almost the same rotations, how do we know that the four samples of 1 from the fluorous mixture synthesis are isomerically pure? This confirmation comes from the chiral HPLC. Injection and coinjection of the four pure isomers of 1 into the Chiralcel OD column reproduced the pattern observed for the mixture sample dim-1 described above. Isomer S,S-1 eluted first, while its enantiomer R,R-1 eluted last. The isomers S,R-1 and R,S-1 eluted together and between the other two isomers. Thus, the chiral HPLC experiment resolves the diastereomers and further resolves one pair of enantiomers but not the other. That R,R-1 and S,S-1 give essentially single peaks on HPLC analysis shows that they are both diastereomerically and enantiomerically pure. The results show that S,R-1 and R,S-1 are diastereopure, and they must also be enantiopure because the samples were all literally made together. Thus, this pair is simply not resolved into its enantiomers by the chiral column.

Structure Assignments

Armed with mixture and individual samples of all four isomers and having validated the Mosher analysis, we are ready to assign configurations to the petrocortyne natural products. We did not succeed in obtaining samples of either isolate, but both papers provide extensive information about the natural samples and Mosher derivatives. Based on comparison of our data with the published data, we conclude that the structure of (3R,14R)-petrocotyne A is incorrect, and that the structure of (3S,14S)-petrocortyne A is correct.

Looking at optical rotations first, the signs and magnitudes of the reported optical rotation by both Shin5 (+6.4, c = 0.25 MeOH) and Jung7 (+10.8, c = 1.9, MeOH) are consistent with the measured optical rotations of either (3S,14R)-petrocortyne A or (3S,14S)-petrocortyne A. The rotation of Jung’s sample is “spot on” for the (3S,14S)-isomer, but as stated above, we maintain that the magnitudes of rotations of the two diastereomers are too close to differentiate relative stereochemistry. So the rotation comparison confirms the configuration of C3 as S. Accordingly, Jung’s assignment of this stereocenter is correct and Shin’s is incorrect. Because the diastereomers of petrocortyne A have identical 1H and 13C NMR spectra, the assignment of C14 does not follow from the assignment of C3.

Next, we converted the pair of diastereomers with the (3S) configuration to both the bis-(R)- and bis-(S)-Mosher esters, and recorded and assigned a complete set of 1D and 2D 1H NMR spectra. The structures of the Mosher esters and their entire spectra are shown in the Supporting Information of the prior communication.10 The analysis of the spectra in that paper also showed that the advanced Mosher rule can be used (with care) to assign the configuration at C14 in petrocortynes, and that a new “short cut” Mosher rule can also be applied for this task.

In practice, however, no rules or subtractions were needed to assign the configuration of the petrocortyne A Mosher esters because we had available spectra of all possible isomers. Setting rules aside, we simply matched our spectra with those of Shin and Jung. We initially expected that this matching would require 2D spin lock experiments to differentiate H11 and H17, which are in nearly symmetric environments. Such assignments were used by both Shin and Jung for their Mosher analyses, and we did them too for validation.

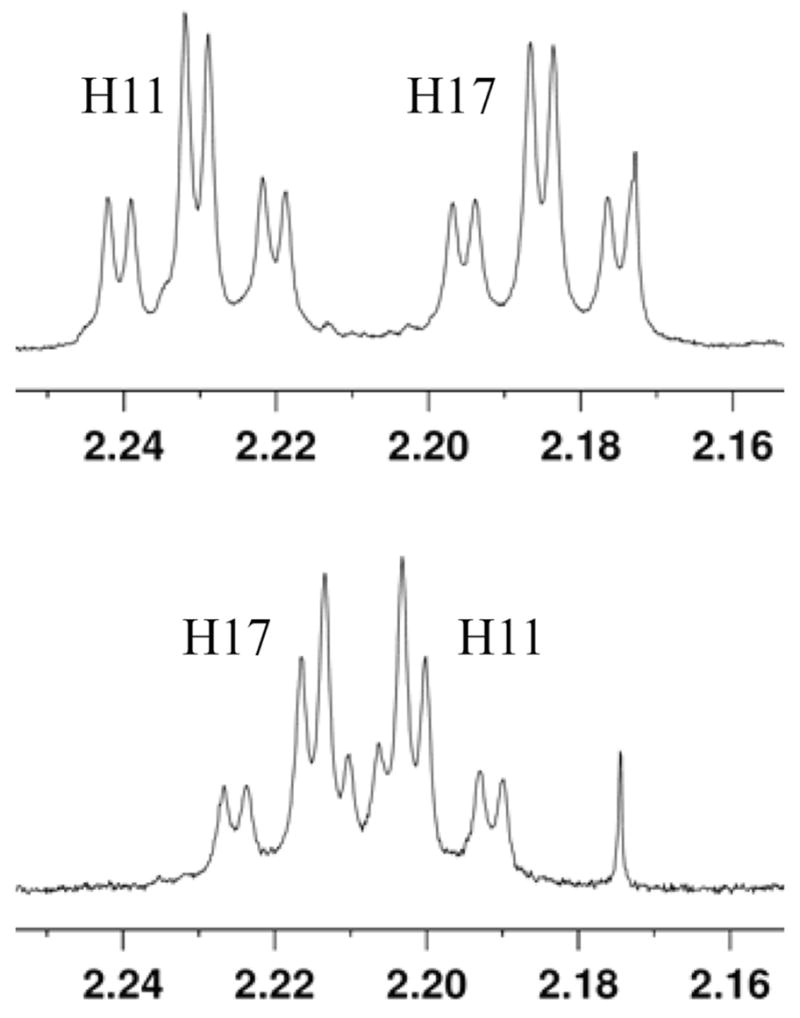

However, the proper assignment of H11 and H17 was rendered superfluous because the diastereomers of petrocortyne showed clear differences in their Mosher spectra. Expansions of the spectra of bis-(S)-Mosher esters made from the synthetic (3S,14S) and (3S,14R) isomers of 1 are shown in Figure 4 along with assignments of H11 and H17. These assignments were made by TCOSY experiments, and can also be made by either the advanced Mosher rule of the new short cut.10 That the spectra of the diastereomers are different means that the Mosher ester at the C3 stereocenter has an effect on its counterpart eleven atoms down the chain at C14. This long range effect is remarkable, and the differences, if small, are unmistakable even at lower field strengths than that shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Expansions of portions of the 1H NMR spectra of the bis-(S)-Mosher esters of (3S,14S)-1 (top) and (3S,14R)-1 (bottom) with proton assignments.

Because all four Mosher spectra of the petrocortyne isomers were unique, we set aside all the resonance assignments and simply matched the 1D 1H NMR spectra of the synthetic Mosher esters with those reported by Shin and Jung. The spectrum of the bis-(S)-Mosher ester of synthetic (3S,14S)-1 uniquely matched the spectra reported by both groups.23 In turn, both of their bis-(R)-Mosher spectra matched those from synthetic (3S,14S)-1 as well. This means that Shin’s and Jung’s samples are identical, not enantiomers, and that Jung’s assignment of the 3S,14S configuration is correct. It also means that both groups properly assigned H11 and H17 in their Mosher esters. Jung then properly applied the advanced Mosher rule to assign the natural product configuration.

Unfortunately, Shin must have neglected to recognize the change in CIP priority attendant with using Mosher acid chlorides in the advanced Mosher rule.6 In other words, he did all of the correct assignments and subtractions, but reversed the configurations of the stereocenters of his Mosher esters. That process reversed both stereocenters in the final assignment. The same group has described the isolation and assignments of a number of other petrocortynes. In reviewing these assignments, we learned that the same errors were made consistently. Accordingly, the absolute configurations of petrocortynes B,5 D,2a E,2a F,2a G2a and H2a in the indicated references need to be reversed, while the structures of B,2d G2c and H2c in the indicated references are correct.

Conclusions

Two different mixture synthesis routes have been used to make the four stereoisomers of petrocortyne A. A quick and dirty route provided a mixture of the four isomers in non-selective fashion. That the intermediate diastereomers did not separate and exhibited identical spectra facilitated the synthesis of the isomers. Both Mosher and NMA derivatization methods were developed to identify the final petrocortyne A isomers. The mixture was partially resolved on chiral HPLC to give two pure enantiomers of the syn diastereomer along with the racemate of the anti diastereomer. Planned preparative resolution and derivatization were aborted because the four pure enantiomers became available through the fluorous mixture synthesis. However, with hindsight we conclude that this approach would have succeeded because the enantiomeric pair that resolved was that of petrocortyne A.

This traditional mixture synthesis is easy but risky. The risk is in the uncertainty of final separation of the diastereomers, which must be accomplished in order to complete their identification. That risk is maximized because it is postponed to the very end of the synthesis. The fluorous mixture synthesis produced all four isomers of petrocortyne in individual pure form. The extra effort in making precursors in enantiopure form and tagging them with fluorous tags paid dividends in the end with easy separation and identification by fluorous demixing.

Comparison of optical rotations of the four synthetic and two natural samples of 1 showed that both natural samples had the C3-(S) configuration but left unresolved the configuration at C14. Comparison of spectra of Mosher derivatives of the synthetic and natural samples showed that both natural samples had the (3S,14S) configuration. Because we have all possible diastereomers and their Mosher esters, this comparison is accomplished by matching spectra and does not rely on the advanced Mosher rule. At the same time, the use of the Mosher rule has been validated for assigning the difficult C14 stereocenter of the petrocortynes. As we showed in the communication,10 a “short cut” variant in which only one Mosher ester is made can also be used for this stereocenter. Finally, for compounds that differ from petrocortyne only in areas remote from the stereocenters, the Mosher rule again becomes completely unnecessary; it suffices to simply make one Mosher ester, record its 1H NMR spectra and match that to the library of spectra reported herein.

In the bigger picture, having access to all possible candidate isomers for a given structure is of great value in securing a hard and fast structure assignment. As we stressed in a recent paper on murisolins,9b the security of the assignment comes not so much because one of the isomers “matches” the natural product, but because all of the other isomers do not.

Experimental

General

This experimental section contains details for the fluorous mixture synthesis as described in Scheme 5 and for the synthesis of the final Mosher esters. General methods and experimental details for all other work in the paper are contained in the Supporting Information.

(R,E)-1-(tert-Butyldimethylsilyl)-11-(4-methoxybenzyloxy)undec-4-en-1-yn-3-ol (R-21)

A solution of compound 2 (10.62 g, 25.6 mmol) in THF (90 ml) was added dropwise in 10 min to a solution of (R)-CBS (7.10 g, 25.6 mmol) and BH3·SMe2 (2.8 mL, 29.5 mmol) in THF (30 mL) at 0 °C under Ar. Upon completion of addition, reaction was cautiously quenched by slow addition of MeOH (30 mL) at 0 °C. The resulting solution was stirred for 15 min at room temperature and most organic solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by column chromatography (hexane/EtOAc = 17:3) to afford the title compound R-21 (7.48 g, 70%, 93% ee), [α]D 25 = −21.7 (c = 1.30, CHCl3), 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.26 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2 H), 6.88 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2 H), 5.90 (dtd, J = 15.3, 6.6, 0.9 Hz, 1 H), 5.59 (ddt, J = 15.3, 5.7, 1.4 Hz, 1 H), 4.82 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1 H), 4.43 (s, 2 H), 3.80 (s, 3 H), 3.43 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2 H), 2.06 (q, J = 6.6 Hz, 2 H), 1.80 (d, J = 6.3 Hz, 1 H), 1.63–1.55 (m, 2 H), 1.45–1.28 (m, 6 H), 0.94 (s, 9 H), 0.12 (s, 6 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 158.9, 133.7, 130.6, 129.1, 128.8, 113.6, 105.8, 88.4, 72.3, 69.9, 63.0, 55.1, 31.7, 29.5, 28.8, 28.7, 26.0, 25.9, 16.4, −4.8; IR (film) 3593, 3419, 2932, 2858, 1612, 1513, 1465, 1363, 1301, 1249, 1091, 1034, 909, 827, 777, 734 cm−1; HRMS (ESI) m/z (M+ + Na) calcd for C25H40O3NaSi 439.2644, found 439.2620.

(S,E)-1-(tert-Butyldimethylsilyl)-11-(4-methoxybenzyloxy)undec-4-en-1-yn-3-ol (S-21)

Following the same procedure for R-21, ketone 2 (9.50 g, 22.9 mmol) was reacted with (S)-CBS (6.35 g, 22.9 mmol), BH3·SMe2 (2.5 mL, 26.4 mmol), the title compound S-21 (6.99 g, 73%, 94% ee) was obtained. [α]D 25 = +22.1 (c = 1.17, CHCl3), 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.26 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2 H), 6.88 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2 H), 5.89 (dt, J = 15.0, 6.9 Hz, 1 H), 5.59 (dd, J = 15.0, 5.7 Hz, 1 H), 4.82 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1 H), 4.43 (s, 2 H), 3.80 (s, 3 H), 3.43 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2 H), 2.05 (q, J = 6.6 Hz, 2 H), 1.86 (d, J = 6.3 Hz, 1 H), 1.63–1.54 (m, 2 H), 1.45–1.28 (m, 6 H), 0.94 (s, 9 H), 0.12 (s, 6 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 159.0, 133.9, 130.7, 129.2, 128.8, 113.7, 105.7, 88.7, 72.4, 70.0, 63.2, 55.2, 31.8, 29.6, 28.9, 28.7, 26.0(2C), 16.4, −4.7; IR (film) 3405, 2931, 2857, 1613, 1513, 1464, 1362, 1302, 1249, 1091, 1035, 910, 828, 776, 733 cm−1; MS (EI) m/z 439 (M+ + Na); HRMS (ESI) m/z (M+ + Na) calcd for C25H40O3NaSi 439.2644, found 439.2640.

(R,E)-tert-Butyl(3-(diisopropyl(4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,7-nonafluoroheptyl)silyloxy)-11-(4-methoxybenzyloxy)undec-4-en-1-ynyl)dimethylsilane (R-22a)

Trifluoromethanesulfonic acid (neat, 1.9 mL, 21.7 mmol) was slowly added to silane C4F9(CH2)3(iPr)2SiH (neat, 8.67 g, 23.0 mmol) at 0 °C. After being stirred for 20 min at the same temperature, the mixture was warmed to room temperature and stirred for 15 h. To it CH2Cl2 (24 mL) was added at −60 °C, followed by a solution of alcohol R-21 (6.00 g, 14.4 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (36 mL) and 2,6-lutidine (3.3 mL, 28.7 mmol). The resulting mixture was warmed to room temperature and stirred for further 2 h. Saturated aqueous NH4Cl (75 mL) was then added to quench the reaction at 0 °C. The mixture was extracted with Et2O (3 × 150 mL), the organic layers were combined and washed with water, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (hexane/EtOAc = 19:1) to afford the title compound R-22a (9.94 g, 87%): [α]D 25 = +1.1 (c = 1.20, CHCl3), 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.26 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2 H), 6.88 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2 H), 5.79 (dtd, J = 15.0, 6.9, 0.9 Hz, 1 H), 5.51 (dd, J = 15.3, 5.7 Hz, 1 H), 4.88 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1 H), 4.43 (s, 2 H), 3.80 (s, 3 H), 3.43 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2 H), 2.19–2.00 (m, 4 H), 1.76–1.69 (m, 2 H), 1.61–1.53 (m, 2 H), 1.43–1.28 (m, 6 H), 1.06 (br s, 14 H), 0.93 (s, 9 H), 0.79–0.73 (m, 2 H), 0.09 (s, 6 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 159.1, 132.2, 130.8, 129.6, 129.2, 113.8, 106.3, 88.0, 72.5, 70.2, 64.0, 55.3, 34.5 (t, JCF = 21.8 Hz, 1 C), 31.8, 29.7, 29.0, 28.9, 26.0 (2 C), 17.6 (2 C), 17.5 (2 C) 16.5, 14.6, 12.7, 12.6, 11.0 −4.8; IR (film) 3020, 2933, 1514, 1423, 1215, 1133, 1044, 928, 755 cm−1; HRMS (ESI) m/z (M+ + Na) calcd for C38H59O3NaSi2F9 813.3757, found 813.3793.

(S,E)-tert-Butyl(11-(4-methoxybenzyloxy)-3-(triisopropylsilyloxy)undec-4-en-1-ynyl)dimethylsilane (S-22b)

2,6–Lutidine (3.5 mL, 30.1 mmol) and TIPSOTf (7.9 mL, 29.4 mmol) were sequentially added to the solution of alcohol S-21 (6.90 g, 16.6 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (160 mL) at 0 °C. The resulting mixture was stirred for 2 h at the same temperature. Saturated aqueous NH4Cl (80 mL) was then added to quench the reaction. The mixture was extracted with Et2O (3 × 150 mL), the organic layers were combined and washed with water, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (hexane/EtOAc = 19:1) to afford the title compound S-22b (8.53 g, 90%): [α]D 25 = −1.0 (c = 0.92, CHCl3), 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.26 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2 H), 6.88 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2 H), 5.80 (dtd, J = 15.3, 6.6, 0.9 Hz, 1 H), 5.52 (dd, J = 15.0, 5.4 Hz, 1 H), 4.92 (dd, J = 5.1, 0.6 Hz, 1 H), 4.43 (s, 2 H), 3.80 (s, 3 H), 3.43 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2 H), 2.04 (q, J = 6.6 Hz, 2 H), 1.61–1.54 (m, 2 H), 1.43–1.28 (m, 6 H), 1.15–1.06 (m, 21 H), 0.92 (s, 9 H), 0.09 (s, 6 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 159.1, 131.7, 130.8, 129.9, 129.2, 113.7, 106.8, 87.5, 72.5, 70.2, 63.9, 55.3, 31.8, 29.7, 28.9 (2 C), 26.1 (2 C), 18.0, 16.5, 12.2, −4.7; IR (film) 3019, 2934, 2864, 1514, 1424, 1216, 1039, 928, 756 cm−1; HRMS (ESI) m/z (M+ + Na) calcd for C34H60O3NaSi2 595.3979, found 595.3959.

(R,E)-tert-Butyl(3-(diisopropyl(4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,7-nonafluoroheptyl)silyloxy)-11-iodoundec-4-en-1-ynyl)dimethylsilane and (S,E)-tert-butyl(11-iodo-3-(triisopropylsilyloxy)undec-4 -en-1-ynyl)dimethylsilane (qrac-23a,b)

DDQ (9.93 g, 43.7 mmol) was added to the mixture of compound R-22a (9.94 g, 12.6 mmol) and compound S-22b (7.24 g, 12.6 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (250 mL) and H2O (13 mL) at room temperature. The reaction was monitored by TLC until completion, and then saturated NaHCO3 aqueous solution was added. The mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 150 mL), the organic layers were combined, washed with saturated NaHCO3 aqueous solution, brine, dried over MgSO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (hexane/Et2O = 4:1) to afford the title compound, which was contaminated with tiny 4-(methoxymethyl)benzaldehyde and was used in the following step without further purification.

To a solution of triphenylphosphine (5.44 g, 20.7 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (27 mL) was slowly added a solution of iodine (5.26 g, 20.7 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (27 mL), followed by a mixture of imidazole (1.55 g, 22.8 mmol) and alcohol (5.74 g, 10.2 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (80 mL) at room temperature. After 2 h, the reaction was quenched with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (100 mL). The mixture was extracted with Et2O (3 × 100 mL) and organic layer was washed with saturated aqueous Na2S2O3 (100 mL), water, brine, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (hexane/EtOAc = 99:1) to afford the title compound qrac-23a,b (5.62 g, 42% for two steps): 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.83–5.74 (m, 1 H), 5.52 (dd, J = 15.0, 5.1 Hz, 1 H), 4.94–4.88 (m, 1 H), 3.18 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2 H), 2.19–2.04 (m, 4H), 1.88–1.70 (m, 4H), 1.47–1.27 (m, 8 H), 1.19–1.02 (m, 17.5 H), 1.06 (s, 9 H), 0.79–0.73 (m, 2 H), 0.09 (s, 6 H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 131.9, 131.4, 130.1, 129.8, 106.8, 106.2, 88.1, 87.6, 64.0, 63.8, 34.5 (t, JCF = 21.8 Hz), 33.5, 31.6, 30.3, 28.7, 28.0, 26.0, 18.0, 17.6, 17.5, 16.5, 14.6, 12.7, 12.6, 12.2, 10.9, 7.1; IR (film) 2932, 2862, 1464, 1384, 1236, 1133, 1057, 908, 826, 733; MS (EI) for qrac-23a m/z 737 (M+ – C3H7); qrac-23b m/z 519 (M+ – C3H7); HRMS (ESI) qrac-23a m/z (M+ – C3H7) calcd for C27H43OF9Si2I 737.1753, found 737.1748; qrac-23b m/z (M+ – C3H7) calcd for C23H44OSi2I 519.1976, found 519.1993.

(12R,23R,E)-23-((tert-Butyldimethylsilyl)ethynyl)-29,29,30,30,31,31,32,32,32-nonafluoro-25,25-diisopropyl-4,24-dioxa-2-thia-25-siladotriaconta-21-en-10,13-diyn-12-ol and (12R,23S,E)-23-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)ethynyl)-25,25-diisopropyl-26-methyl-4,24-dioxa-2-thia-25-silaheptacosa-21-en-10,13-diyn-12-ol (R-qdim-24a,b)

n-BuLi (4.0 mL, 1.6 M solution in THF, 6.4 mmol) was slowly added to the solution of alkyne R-18 (679.0 mg, 3.0 mmol) in THF (15 mL) at −30 °C. After stirring at the same temperature for 1 h, the mixture was cooled to −78 °C, HMPA (1.5 mL) was added followed by a solution of iodide qrac-23a,b (1.01 g, 1.5 mmol) in THF (7.5 mL). The resulting mixture was stirred for 2 h at −78 °C and warmed to room temperature. After stirring at room temperature for overnight, saturated NH4Cl aqueous solution (20 mL) was added, the organic layer was separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with Et2O (3 × 20 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with water, brine, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (hexane/Et2O = 4:1) to afford the mixture R-qdim-24a,b (370.7 mg, 34%) which was contaminated with some inseparable impurities and was used in the following step without further purification. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.80–5.76 (m, 1 H), 5.55–5.49 (m, 1 H), 5.10–5.08 (m, 1 H), 4.93–4.88 (m, 1 H), 4.63 (s, 2 H), 3.52 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 2 H), 2.23 (quind, J = 7.0, 1.5 Hz, 4 H), 2.15 (s, 3 H), 2.12–2.06 (m, 1 H), 2.05 (q, J = 6.5 Hz, 2 H), 1.78–1.69 (m, 1 H), 1.64–1.45 (m, 8 H), 1.40–1.25 (m, 6 H), 1.10–1.05 (m, 17.5 H), 0.93 (s, 9 H), 0.78–0.74 (m, 1 H), 0.09 (s, 6 H); HRMS (ESI) R-qdim-24a m/z (M+ + Na) calcd for C42H67O3F9NaSi2S 901.4103, found 901.4134; R-qdim-24b m/z (M+ + Na) calcd for C38H68O3NaSi2S 683.4325, found 683.4340.

(12S,23R,E)-23-((tert-Butyldimethylsilyl)ethynyl)-29,29,30,30,31,31,32,32,32-nonafluoro-25,25-diisopropyl-4,24-dioxa-2-thia-25-siladotriaconta-21-en-10,13-diyn-12-ol and (12S,23S,E)-23-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)ethynyl)-25,25-diisopropyl-26-methyl-4,24-dioxa-2-thia-25-silaheptacosa-21-en-10,13-diyn-12-ol (S-qdim-24a,b)

Following the same procedure for R-qdim-24a,b, alkyne S-18 (679.0 mg, 3.0 mmol) was reacted with n-BuLi (4.0 mL, 1.6 M solution in THF, 6.4 mmol), HMPA (1.5 mL), and iodide qrac-23a,b (1.01 g, 1.5 mmol), the title mixture S-qrac-24a,b (356.2 mg, 33%) was obtained, which was contaminated with some inseparable impurities and was used in the following step without further purification. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.82–5.77 (m, 1 H), 5.55–5.49 (m, 1 H), 5.10–5.08 (m, 1 H), 4.92–4.88 (m, 1 H), 4.63 (s, 2 H), 3.52 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2 H), 2.23–2.20 (m, 4 H), 2.15 (s, 3 H), 2.14–2.09 (m, 1 H), 2.05 (q, J = 6.6 Hz, 2 H), 1.76–1.70 (m, 1 H), 1.63–1.43 (m, 8 H), 1.40–1.25 (m, 6 H), 1.11–1.03 (m, 17.5 H), 0.92 (s, 9 H), 0.77–0.74 (m, 1 H), 0.09 (s, 6 H); HRMS (ESI) S-qdim-24a m/z (M+ + Na) calcd for C42H67O3F9NaSi2S 901.4103, found 901.4072; S-qdim-24b m/z (M+ + Na) calcd for C38H68O3NaSi2S 683.4325, found 683.4296

(12R,23R,E)-23-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)ethynyl)-12-(diisopropyl(4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,7-nonafluoroheptyl)silyloxy)-29,29,30,30,31,31,32,32,32-nonafluoro-25,25-diisopropyl-4,24-dioxa-2-thia-25-siladotriaconta-21-en-10,13-diyne and (12R,23S,E)-23-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)ethynyl)-12-(diisopropyl(4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,7-nonafluoroheptyl)silyloxy)-25,25-diisopropyl-26-methyl-4,24-dioxa-2-thia-25-silaheptacosa-21-en-10,13-diyne (qdim-25a,b/a)

Trifluoromethanesulfonic acid (neat, 72.4 μL, 0.82 mmol) was slowly added to silane C4F9(CH2)3(iPr)2SiH (neat, 359.0 mg, 0.95 mmol) at 0 °C. After being stirred for 20 min at the same temperature, the mixture was warmed to room temperature and stirred for 15 h. To it CH2Cl2 (0.8 mL) was added at −60 °C, followed by a solution of alcohol R-qdim-24a,b (200.0 mg, 0.27 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (1.2 mL) and 2,6-lutidine (0.13 mL, 1.09 mmol). The resulting mixture was warmed to room temperature and stirred for further 2 h. Saturated aqueous NH4Cl (10 mL) was then added to quench the reaction at 0 °C. The mixture was extracted with Et2O (3 × 10 mL), the organic layers were combined and washed with water, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (hexane/Et2O = 97:3) to afford the title mixture qdim-25a,b/a (272.5 mg, 99%): 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.81–5.77 (m, 1 H), 5.54–5.49 (m, 1 H), 5.21 (s, 1 H), 4.92–4.87 (m, 1 H), 4.62 (s, 2 H), 3.50 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2 H), 2.23–2.18 (m, 4 H), 2.14 (s, 3 H), 2.12–2.03 (m, 5 H), 1.80–1.73 (m, 3 H), 1.62–1.41 (m, 8 H), 1.40–1.33 (m, 4 H), 1.31–1.25 (m, 2 H), 1.12–1.05 (m, 31.5 H), 0.92 (s, 9 H), 0.79–0.75 (m, 3 H), 0.09 (s, 6 H); MS (EI) qdim-25a/a m/z 1275 (M+ + Na); qdim-25b/a m/z 1057 (M+ + Na); HRMS (ESI) qdim-25a/a m/z (M+ + Na) calcd for C55H86O3F18NaSi3S 1275.5216, found 1275.5210; qdim-25b/a m/z (M+ + Na) calcd for C51H87O3F9NaSi3S 1057.5438, found 1057.5407.

(12S,23R,E)-23-((tert-Butyldimethylsilyl)ethynyl)-29,29,30,30,31,31,32,32,32-nonafluoro-12-((4,4,5,5,6,6,6-heptafluorohexyl)diisopropylsilyloxy)-25,25-diisopropyl-4,24-dioxa-2-thia-25-siladotriaconta-21-en-10,13-diyne and (12S,23S,E)-23-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)ethynyl)-12-((4,4,5,5,6,6,6-heptafluorohexyl)diisopropylsilyloxy)-25,25-diisopropyl-26-methyl-4,24-dioxa-2-thia-25-silaheptacosa-21-en-10,13-diyne (qdim-25a,b/c)

Following the same procedure for R-qdim-24a,b, the mixture S-qdim-24a,b (250.0 mg, 0.34 mmol) was reacted with trifluoromethanesulfonic acid (neat, 79.6 μL, 0.90 mmol), silane C3F7(CH2)3(iPr)2SiH (neat, 333.6 mg, 1.02 mmol), and 2,6-lutidine (0.14 mL, 1.19 mmol), the title mixture qdim-25a,b/c (277.7 mg, 85%) was obtained: 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.80–5.77 (m, 1 H), 5.54–5.50 (m, 1 H), 5.21 (s, 1 H), 4.92–4.87 (m, 1 H), 4.62 (s, 2 H), 3.50 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2 H), 2.23–2.18 (m, 4 H), 2.14 (s, 3 H), 2.12–2.03 (m, 5 H), 1.80–1.73 (m, 3 H), 1.62–1.43 (m, 8 H), 1.40–1.33 (m, 4 H), 1.31–1.25 (m, 2 H), 1.12–1.05 (m, 31.5 H), 0.92 (s, 9 H), 0.79–0.75 (m, 3 H), 0.09 (s, 6 H); MS (EI) qdim-25a/c m/z 1225 (M+ + Na); qdim-25b/c m/z 1008 (M+ + Na + H); HRMS (ESI) qdim-25a/c m/z (M+ + Na) calcd for C54H86O3F16NaSi3S 1225.5248, found 1225.5231; qdim-25b/c m/z (M+ + Na) calcd for C50H87O3F7NaSi3S 1007.5470, found 1007.5438.

(8R,19R,E)-21-(tert-Butyldimethylsilyl)-8,19-bis(diisopropyl(4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,7-nonafluoroheptyl)silyloxy)henicosa-17-en-6,9,20-triyn-1-ol, (8R,19S,E)-21-(tert-butyldimethylsilyl)-8-(diisopropyl(4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,7-nonafluoroheptyl)silyloxy)-19-(triisopropylsilyloxy)henicosa-17-en-6,9,20-triyn-1-ol, (8S,19R,E)-21-(tert-butyldimethylsilyl)-19-(diisopropyl(4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,7-nonafluoroheptyl)silyloxy)-8-((4,4,5,5,6,6,6-heptafluorohexyl)diisopropylsilyloxy)henicosa-17-en-6,9,20-triyn-1-ol, and (8S,19S,E)-21-(tert-butyldimethylsilyl)-8-((4,4,5,5,6,6,6-heptafluorohexyl)diisopropylsilyloxy)-19-(triisopropylsilyloxy)henicosa-17-en-6,9,20-triyn-1-ol (qdim-26a,b/a,c)

Solid NaHCO3 (324.4 mg, 3.86 mmol) and MeI (9.0 mL) were added to the solution of mixture qdim-25a,b/a (270.0 mg, 0.27 mmol) and qdim-25a,b/c (259.4 mg, 0.27 mmol) in mixture of acetone (16.0 mL) and water (0.86 mL). The resulting suspension was stirred in a sealed tube at 45 °C for 14 h. The mixture was diluted with water (20 mL) and EtOAc (30 mL). The organic layer was separated and the aqueous phase was extracted with EtOAC (3 × 20 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with brine, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (hexane/Et2O = 3:1) to afford the mixture qdim-26a,b/a,c (451.0 mg, 90%): 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.82–5.76 (m, 1 H), 5.54–5.49 (m, 1 H), 5.20 (s, 1 H), 4.92–4.87 (m, 1 H), 3.64 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2 H), 2.24–2.18 (m, 4 H), 2.14–2.03 (m, 5 H), 1.78–1.73 (m, 3 H), 1.62–1.43 (m, 8 H), 1.40–1.24 (m, 6 H), 1.13–1.05 (m, 31.5 H), 0.92 (s, 9 H), 0.79–0.75 (m, 3 H), 0.09 (s, 6 H); MS (EI) qdim-26a/a m/z 1215 (M+ + Na); qdim-26b/a m/z 998 (M+ + Na + H); qdim-26a/c m/z 1165 (M+ + Na); qdim-26b/c m/z 948 (M+ + Na + H) HRMS (ESI) qdim-26a/a m/z (M+ + Na) calcd for C53H82O3F18NaSi3 1215.5182, found 1215.5067; qdim-26b/a m/z (M+ + Na) calcd for C49H83O3F9NaSi3 997.5404, found 997.5370; qdim-26a/c m/z (M+ + Na) calcd for C52H82O3F16NaSi3 1165.5214, found 1165.5240; qdim-26b/c m/z (M+ + Na) calcd for C48H83O3F7NaSi3 947.5436, found 947.5422.

(8R,19R,E)-21-(tert-Butyldimethylsilyl)-8,19-bis(diisopropyl(4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,7-nonafluoroheptyl)silyloxy)henicosa-17-en-6,9,20-triynal, (8R,19S,E)-21-(tert-butyldimethylsilyl)-8-(diisopropyl(4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,7-nonafluoroheptyl)silyloxy)-19-(triisopropylsilyloxy)henicosa-17-en-6,9,20-triynal, (8S,19R,E)-21-(tert-butyldimethylsilyl)-19-(diisopropyl(4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,7-nonafluoroheptyl)silyloxy)-8-((4,4,5,5,6,6,6-heptafluorohexyl)diisopropylsilyloxy)henicosa-17-en-6,9,20-triynal, and (8S,19S,E)-21-(tert-butyldimethylsilyl)-8-((4,4,5,5,6,6,6-heptafluorohexyl)diisopropylsilyloxy)-19-(triisopropylsilyloxy)henicosa-17-en-6,9,20-triynal (qdim-27a,b/a,c)

NaHCO3 (196.2 mg, 2.34 mmol) was added followed by DMP (371.5 mg, 0.88 mmol) to the solution of mixture qdim-26a,b/a,c (270.0 mg, 0.29 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (4.5 mL) at room temperature. The resulting mixture was stirred at the same temperature for 2 h. Saturated NH4Cl aqueous solution (15 mL) was added. The organic phase was separated and the aqueous phase was extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 10 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with brine, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (hexane/Et2O = 9:1) to afford the mixture qdim-27a,b/a,c (200.3 mg, 74%): 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.76 (s, 1 H), 5.82–5.76 (m, 1 H), 5.54–5.49 (m, 1 H), 5.20 (s, 1 H), 4.92–4.87 (m, 1 H), 2.44 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2 H), 2.24 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2 H), 2.19 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2 H), 2.14–2.02 (m, 5 H), 1.79–1.70 (m, 5 H), 1.57–1.46 (m, 6 H), 1.38–1.33 (m, 4 H), 1.31–1.25 (m, 2 H), 1.13–1.05 (m, 31.5 H), 0.92 (s, 9 H), 0.79–0.75 (m, 3 H), 0.09 (s, 6 H); HRMS (ESI) qdim-27a/a m/z (M+ + Na) calcd for C53H80O3F18NaSi3 1213.5026, found 1213.5062; qdim-27b/a m/z (M+ + Na) calcd for C49H81O3F9NaSi3 995.5248, found 995.5237; qdim-27a/c m/z (M+ + Na) calcd for C52H80O3F16NaSi3 1163.5058, found 1163.5033; qdim-27b/c m/z (M+ + Na) calcd for C48H81O3F7NaSi3 945.5279, found 945.5278.

(10R,21R,E)-21-((7Z,13Z,29Z)-32-(tert-Butyldimethylsilyl)dotriaconta-7,13,29-trien-1,31-diynyl)-10-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)ethynyl)-1,1,1,2,2,3,3,4,4,27,27,28,28,29,29,30,30,30-octadecafluoro-8,8,23,23-tetraisopropyl-9,22-dioxa-8,23-disilatriacont-11-en-19-yne, (5S,16R,E)-16-((7Z,13Z,29Z)-32-(tert-butyldimethylsilyl)dotriaconta-7,13,29-trien-1,31-diynyl)-5-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)ethynyl)-22,22,23,23,24,24,25,25,25-nonafluoro-3,3,18,18-tetraisopropyl-2-methyl-4,17-dioxa-3,18-disilapentacos-6-en-14-yne, (9S,20R,E)-9-((7Z,13Z,29Z)-32-(tert-butyldimethylsilyl)dotriaconta-7,13,29-trien-1,31-diynyl)-20-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)ethynyl)-1,1,1,2,2,3,3,26,26,27,27,28,28,29,29,29-hexadecafluoro-7,7,22,22-tetraisopropyl-8,21-dioxa-7,22-disilanonacos-18-en-10-yne, and (5S,16S,E)-16-((7Z,13Z,29Z)-32-(tert-butyldimethylsilyl)dotriaconta-7,13,29-trien-1,31-diynyl)-5-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)ethynyl)-22,22,23,23,24,24,24-heptafluoro-3,3,18,18-tetraisopropyl-2-methyl-4,17-dioxa-3,18-disilatetracos-6-en-14-yne (qdim-28a,b/a,c)

NaHMDS (0.63 mL, 1.0 M solution in THF, 0.63 mmol) was added to the solution of phosphonium bromide 13 (658.9 mg, 0.82 mmol) in THF (2.1 mL) at 0 °C. The resulting orange solution was stirred at the same temperature for 10 min and then cooled to −78 °C. The solution of aldehyde qdim-27a,b/a,c (190.0 mg, 0.21 mmol) in THF (1.4 mL) was then added. The mixture was stirred at −78 °C for 2 h. Saturated NH4Cl aqueous solution (10 mL) was added, the organic phase was separated and aqueous phase was extracted with Et2O (3 × 10 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with brine, dried over MgSO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (hexane/CH2Cl2 = 9:1) to afford the title compound qdim-28a,b/a,c (137.2 mg, 44%): 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.96 (dt, J = 10.8, 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 5.83–5.76 (m, 1 H), 5.54–5.47 (m, 2 H), 5.38–5.30 (m, 4 H), 5.21 (s, 1 H), 4.92–4.87 (m, 1 H), 2.32 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2 H), 2.20 (q, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 2.15–2.08 (m, 3 H), 2.06–1.98 (m, 10 H), 1.79–1.72 (m, 3 H), 1.53–1.47 (m, 4 H), 1.44–1.25 (m, 36 H), 1.13–1.05 (m, 31.5 H), 0.96 (s, 9 H), 0.92 (s, 9 H), 0.79–0.75 (m, 3 H), 0.13 (s, 6 H), 0.09 (s, 6 H).

Demix the mixture qdim-28a,b/a,c

The mixture qdim-28a,b/a,c (137.2 mg, 0.09 mmol) was dissolved in CH3CN/THF (3:2) (6 mL) and demixed by semi-preparative fluorous HPLC (FluorosFlash PFC8 column, CH3CN:THF = 100:0 to 85:15 in 45 min, then 85:15 for another 20 min). The four desired compounds were obtained.

28b/c: 41.3 mg, t = 20.3 min

28b/a: 39.5 mg, t = 25.5 min

28a/c: 16.0 mg, t = 42.2 min

28a/a: 19.7 mg, t = 52.7 min

(3S,4E,14S,21Z,27Z,43Z)-Hexatetraconta-4,21,27,43-tetraen-1,12,15,45-tetrayne-3,14-diol ((3S,14S)-1)

TBAF (0.24 mL, 1.0 M solution in THF, 0.24 mmol) was added to a solution of compound 28b/c (40.0 mg, 0.029 mmol) in THF (0.6 mL) at room temperature. The mixture then was stirred for 1 h at this temperature and quenched with saturated aqueous NH4Cl. The resulting mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 5 mL). The organic layers were washed with brine, dried over MgSO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (hexane/Et2O = 4:1) to give compound (3S,14S)-1 (11.4 mg, 59%): [α]D 25 = +10.5 (c = 0.30, CH3OH), 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.00 (dt, J = 10.8, 7.2 Hz, 1 H), 5.91 (dt, J = 15.0, 7.0 Hz, 1 H), 5.62 (dd, J = 15.0, 6.0 Hz, 1 H), 5.44 (dd, J = 10.8, 1.2 Hz, 1 H), 5.39–5.31 (m, 4 H), 5.09 (dt, J = 7.2, 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 4.84 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1 H), 3.07 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 2.57 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1 H), 2.32 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2 H), 2.23 (qd, J = 6.0, 1.2 Hz, 4 H), 2.13 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1 H), 2.08 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2 H), 2.06–1.99 (m, 8 H), 1.88 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1 H), 1.55–1.49 (m, 4 H), 1.46–1.25 (m, 36 H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 146.31, 134.32, 130.21, 130.07, 129.65, 129.31, 128.52, 107.88, 85.02, 84.97, 83.26, 81.13, 80.58, 78.10, 78.10, 74.01, 62.77, 52.54, 31.76, 30.26, 29.76, 29.68 (3 C), 29.65 (3 C), 29.57, 29.44, 29.37, 29.33 (2 C), 29.17, 28.87, 28.72, 28.56, 28.54, 28.49, 28.19, 27.92, 27.23, 27.13, 27,09, 26.65, 18.64, 18.63; IR (film) 3054, 2986, 2929, 2855, 1422, 1265, 909, 740; MS (EI) m/z 678 (M+ + Na + H); HRMS (ESI) m/z (M+ + Na) calcd for C46H70O2Na 677.5274, found 677.5321.

(3S,4E,14R,21Z,27Z,43Z)-Hexatetraconta-4,21,27,43-tetraen-1,12,15,45-tetrayne-3,14-diol ((3S,14R)-1)

Following the same procedure for (3S,14S)-1, the compound 28b/a (38.0 mg, 0.027 mmol) was reacted with TBAF (0.22 mL, 1.0 M solution in THF, 0.22 mmol), the title compound (3S,14R)-1 (10.4 mg, 59%) was obtained: [α]D 25 = +9.5 (c = 0.25, CH3OH), 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.00 (dt, J = 10.8, 7.2 Hz, 1 H), 5.91 (dt, J = 15.6, 7.2 Hz, 1 H), 5.62 (ddd, J = 15.6, 6.0, 0.6 Hz, 1 H), 5.44 (dd, J = 10.8, 1.2 Hz, 1 H), 5.39–5.31 (m, 4 H), 5.09 (dt, J = 6.6, 1.2 Hz, 1 H), 4.84 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1 H), 3.07 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 2.57 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 2.32 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2 H), 2.23 (qd, J = 6.5, 1.2 Hz, 4 H), 2.11 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1 H), 2.08 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2 H), 2.06–1.99 (m, 8 H), 1.87 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1 H), 1.56–1.49 (m, 4 H), 1.46–1.25 (m, 36 H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 146.32, 134.33, 130.21, 130.07, 129.65, 129.31, 128.51, 107.87, 85.03, 84.98, 83.26, 81.12, 80.58, 78.09, 78.08, 74.02, 62.78, 52.54, 31.77, 30.26, 29.76, 29.68 (3 C), 29.66 (3 C), 29.58, 29.44, 29.37, 29.33 (2 C), 29.17, 28.87, 28.72, 28.56, 28.54, 28.50, 28.20, 27.91, 27.23, 27.13, 27,09, 26.65, 18.65, 18.63; IR (film) 3054, 2986, 2929, 2855, 1423, 1265, 909, 736; MS (EI) m/z 678 (M+ + Na + H); HRMS (ESI) m/z (M+ + Na) calcd for C46H70O2Na 677.5274, found 677.5267.

(3R,4E,14S,21Z,27Z,43Z)-Hexatetraconta-4,21,27,43-tetraen-1,12,15,45-tetrayne-3,14-diol ((3R,14S)-1)

Following the same procedure for (3S,14S)-1, the compound 28a/c (12.5 mg, 0.008 mmol) was reacted with TBAF (0.07 mL, 1.0 M solution in THF, 0.07 mmol), the title compound (3R,14S)-1 (2.1 mg, 41%) was obtained: [α]D 25 = −9.0 (c = 0.16, CH3OH), 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.00 (dt, J = 10.8, 7.2 Hz, 1 H), 5.91 (dt, J = 15.0, 7.2 Hz, 1 H), 5.62 (dd, J = 15.6, 6.0 Hz, 1 H), 5.44 (dd, J = 10.8, 1.2 Hz, 1 H), 5.39–5.31 (m, 4 H), 5.09 (dt, J = 7.2, 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 4.84 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1 H), 3.07 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 2.57 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 2.32 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2 H), 2.23 (qd, J = 6.9, 1.8 Hz, 4 H), 2.10 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1 H), 2.08 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2 H), 2.06–1.99 (m, 8 H), 1.85 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1 H), 1.56–1.49 (m, 4 H), 1.46–1.25 (m, 36 H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 146.33, 134.35, 130.22, 130.08, 129.66, 129.31, 128.52, 107.88, 85.05, 85.00, 83.26, 81.12, 80.58, 78.08 (2 C), 74.02, 62.80, 52.55, 31.77, 30.27, 29.77, 29.68 (3 C), 29.66 (3 C), 29.59, 29.45, 29.38, 29.34 (2 C), 29.18, 28.88, 28.73, 28.57, 28.55, 28.51, 28.21, 27.92, 27.24, 27.14, 27,09, 26.66, 18.65, 18.63; IR (film) 3053, 2986, 2929, 1423, 1265, 909, 736, 706; MS (EI) m/z 678 (M+ + Na + H); HRMS (ESI) m/z (M+ + Na) calcd for C46H70O2Na 677.5274, found 677.5307.

(3R,4E,14R,21Z,27Z,43Z)-Hexatetraconta-4,21,27,43-tetraen-1,12,15,45-tetrayne-3,14-diol ((3R,14R)-1)

Following the same procedure for (3S,14S)-1, the compound 28a/a (18.5 mg, 0.011 mmol) was reacted with TBAF (0.09 mL, 1.0 M solution in THF, 0.09 mmol), the title compound (3R,14R)-1 (5.1 mg, 69%) was obtained: [α]D 25 = −11.2 (c = 0.20, CH3OH), 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.00 (dt, J = 10.8, 7.2 Hz, 1 H), 5.91 (dt, J = 15.6, 6.6 Hz, 1 H), 5.62 (ddd, J = 15.0, 6.0, 1.2 Hz, 1 H), 5.44 (d, J = 10.8, 1 H), 5.39–5.31 (m, 4 H), 5.09 (dt, J = 7.2, 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 4.84 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1 H), 3.07 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1 H), 2.57 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 2.32 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2 H), 2.23 (qd, J = 7.2, 1.8 Hz, 4 H), 2.11 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1 H), 2.08 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2 H), 2.06–1.99 (m, 8 H), 1.86 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1 H), 1.56–1.49 (m, 4 H), 1.46–1.25 (m, 36 H); 13C NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3) δ 146.33, 134.35, 130.22, 130.08, 129.66, 129.31, 128.52, 107.88, 85.04, 84.99, 83.26, 81.13, 80.58, 78.09 (2 C), 74.03, 62.79, 52.55, 31.77, 30.28, 29.77, 29.69 (3 C), 29.66 (3 C), 29.59, 29.45, 29.38, 29.34 (2 C), 29.18, 28.88, 28.73, 28.56, 28.54, 28.50, 28.20, 27.92, 27.24, 27.14, 27,09, 26.66, 18.65, 18.63; IR (film) 3054, 2986, 1423, 1265, 909, 735, 705; MS (EI) m/z 678 (M+ + Na + H); HRMS (ESI) m/z (M+ + Na) calcd for C46H70O2Na 677.5274, found 677.5295.

Synthesis of Mosher Esters of (3S,14R)-1 and (3S,14S)-1

(2R,2′R)-((3S,4E,14R,21Z,27Z,43Z)-Hexatetraconta-4,21,27,43-tetraen-1,12,15,45-tetrayne-3,14-diyl) bis(3,3,3-trifluoro-2-methoxy-2-phenylpropanoate)

R-MTPA (1.8 mg, 0.0076 mmol) was added to a solution of alcohol (3S, 14R)-1 (1.0 mg, 0.0015 mmol) in DCM (0.5 mL) at rt, followed by addition of DCC (1.9 mg, 0.0092 mmol) and DMAP (0.2 mg, 0.0015 mmol). The resulting mixture was stirred for overnight. The solvent was evaporated and the crude product was purified by column chromatography (hexane/EtOAc = 9:1) to give title compound (1.0 mg, 62%): 1H NMR (700 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.55–7.52 (m, 4 H), 7.41–7.38 (m, 6 H), 6.21 (t, J = 2.1 Hz, 1 H), 6.06 (dtd, J = 15.4, 7.7, 1.4 Hz, 1 H), 6.02–5.98 (m, 2 H), 5.60 (ddt, J = 15.4, 7.0, 1.4 Hz, 1 H), 5.45–5.43 (m, 1 H), 5.38–5.30 (m, 4 H), 3.59 (s, 3 H), 3.55 (s, 3 H), 3.07 (t, J = 1.4 Hz, 1 H), 2.59 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1 H), 2.32 (qd, J = 7.7, 1.4 Hz, 2 H), 2.23 (td, J = 7.0, 2.1 Hz, 2 H), 2.19 (td, J = 7.0, 2.1 Hz, 2 H), 2.08 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2 H), 2.04–1.99 (m, 8 H), 1.56–1.21 (m, 40 H).

(2S,2′S)-((3S,4E,14R,21Z,27Z,43Z)-Hexatetraconta-4,21,27,43-tetraen-1,12,15,45-tetrayne-3,14-diyl) bis(3,3,3-trifluoro-2-methoxy-2-phenylpropanoate)

Following the above procedure, the compound (3S,14R)-1 (1.0 mg, 0.0015 mmol) was reacted with S-MTPA (1.8 mg, 0.0076 mmol) in the present of DCC (1.9 mg, 0.0092 mmol) and DMAP (0.2 mg, 0.0015 mmol), the title compound (0.8 mg, 50%) was obtained: 1H NMR (700 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.56–7.52 (m, 4 H), 7.43–7.38 (m, 6 H), 6.21 (t, J = 2.1 Hz, 1 H), 6.03–5.97 (m, 3 H), 5.49 (ddt, J = 15.4, 7.0, 1.4 Hz, 1 H), 5.45–5.43 (m, 1 H), 5.38–5.29 (m, 4 H), 3.59 (s, 3 H), 3.59 (s, 3 H), 3.07 (t, J = 0.7 Hz, 1 H), 2.63 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1 H), 2.32 (qd, J = 7.7, 1.4 Hz, 2 H), 2.21 (td, J = 7.7, 2.1 Hz, 2 H), 2.20 (td, J = 7.0, 2.1 Hz, 2 H), 2.05–1.99 (m, 10 H), 1.52–1.21 (m, 40 H).

(2R,2′R)-((3S,4E,14S,21Z,27Z,43Z)-Hexatetraconta-4,21,27,43-tetraen-1,12,15,45-tetrayne-3,14-diyl) bis(3,3,3-trifluoro-2-methoxy-2-phenylpropanoate)

Following the above procedure, the compound (3S,14S)-1 (1.0 mg, 0.0015 mmol) was reacted with R-MTPA (1.8 mg, 0.0076 mmol) in the present of DCC (1.9 mg, 0.0092 mmol) and DMAP (0.2 mg, 0.0015 mmol), the title compound (1.1 mg, 69%) was obtained: 1H NMR (700 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.56–7.54 (m, 4 H), 7.43–7.38 (m, 6 H), 6.21 (t, J = 2.1 Hz, 1 H), 6.05 (dtd, J = 15.4, 7.0, 1.4 Hz, 1 H), 6.02–5.98 (m, 2 H), 5.59 (ddt, J = 15.4, 7.0, 1.4 Hz, 1 H), 5.45–5.43 (m, 1 H), 5.37–5.29 (m, 4 H), 3.59 (s, 3 H), 3.55 (s, 3 H), 3.06 (d, J = 0.7 Hz, 1 H), 2.59 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1 H), 2.32 (qd, J = 7.7, 1.4 Hz, 2 H), 2.22 (td, J = 7.0, 2.1 Hz, 2 H), 2.20 (td, J = 7.0, 2.1 Hz, 2 H), 2.07 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2 H), 2.04–1.99 (m, 8 H), 1.52–1.21 (m, 40 H).

(2S,2′S)-((3S,4E,14S,21Z,27Z,43Z)-Hexatetraconta-4,21,27,43-tetraen-1,12,15,45-tetrayne-3,14-diyl) bis(3,3,3-trifluoro-2-methoxy-2-phenylpropanoate)

Following the above procedure, the compound (3S,14S)-1 (1.0 mg, 0.0015 mmol) was reacted with S-MTPA (1.8 mg, 0.0076 mmol) in the present of DCC (1.9 mg, 0.0092 mmol) and DMAP (0.2 mg, 0.0015 mmol), the title compound (0.7 mg, 44%) was obtained: 1H NMR (700 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.55–7.52 (m, 4 H), 7.43–7.38 (m, 6 H), 6.21 (t, J = 1.4 Hz, 1 H), 6.03–5.97 (m, 3 H), 5.49 (dd, J = 15.4, 7.0 Hz, 1 H), 5.44–5.43 (m, 1 H), 5.37–5.29 (m, 4 H), 3.59 (s, 3 H), 3.59 (s, 3 H), 3.06 (d, J = 1.4 Hz, 1 H), 2.63 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1 H), 2.32 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2 H), 2.23 (td, J = 7.0, 2.1 Hz, 2 H), 2.19 (td, J = 7.0, 2.1 Hz, 2 H), 2.05–1.99 (m, 10 H), 1.52–1.21 (m, 40 H).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIH NIGMS), for funding this work. We also thank Dr. Jung for copies of NMR spectra of petrocortyne and its Mosher esters.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Contains complete experimental procedures and compound characterization for all compounds not in the experimental section along with copies of key spectra. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References and Notes

- 1.(a) Keyzers RA, Davies-Coleman MT. Chem Soc Rev. 2005;34:355–365. doi: 10.1039/b408600g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yeung KS, Paterson I. Chem Rev. 2005;105:4237–4313. doi: 10.1021/cr040614c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Blunt JW, Copp BR, Munro MHG, Northcote PT, Prinsep MR. Nat Prod Rep. 2006;23:26–78. doi: 10.1039/b502792f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Shin J, Seo Y, Cho KW. J Nat Prod. 1998;61:1268–1273. doi: 10.1021/np9802015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lim YJ, Kim JS, Im KS, Jung JH, Lee CO, Hong J, Kim DK. J Nat Prod. 1999;62:1215–1217. doi: 10.1021/np9900371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lim YJ, Lee CO, Hong J, Kim DK, Im KS, Jung JH. J Nat Prod. 2001;64:1565–1567. doi: 10.1021/np010247p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Lim YJ, Park HS, Im KS, Lee C-O, Hong J, Lee M-Y, Kim D-k, Jung JH. J Nat Prod. 2001;64:46–53. doi: 10.1021/np000252d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim DK, Lee MY, Lee HS, Lee DS, Lee JR, Lee BJ, Jung JH. Cancer Lett. 2002;185:95–101. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00233-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gung BW, Omollo AO. Eur J Org Chem. 2008:4790–4795. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.200800593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seo Y, Cho KW, Rho JR, Shin J, Sim CJ. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:447–462. [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Ohtani I, Kusumi T, Kashman Y, Kakisawa H. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:4092–4096. [Google Scholar]; (b) Seco JM, Quinoa E, Riguera R. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2000;11:2781–2791. [Google Scholar]; (c) Hoye TR, Jeffrey CS, Shao F. Nature Protocols. 2007;2:2451–2458. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim JS, Lim YJ, Im KS, Jung JH, Shim CJ, Lee CO, Hong J, Lee H. J Nat Prod. 1999;62:554–559. doi: 10.1021/np9803427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hong S, Kim SH, Rhee MH, Kim AR, Jung JH, Chun T, Yoo ES, Cho JY. Arch Pharmacol. 2003;368:448–456. doi: 10.1007/s00210-003-0848-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Curran DP, Zhang QS, Lu HJ, Gudipati V. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:9943–9956. doi: 10.1021/ja062469l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jung WH, Guyenne S, Riesco-Fagundo C, Mancuso J, Nakamura S, Curran DP. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:1130–1133. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704893. and references therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curran DP, Sui B. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:5411–5413. doi: 10.1021/ja900849f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Luo ZY, Zhang QS, Oderaotoshi Y, Curran DP. Science. 2001;291:1766–1769. doi: 10.1126/science.1057567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Curran DP, Zhang QS, Richard C, Lu HJ, Gudipati V, Wilcox CS. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:9561–9573. doi: 10.1021/ja061801q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang QS, Curran DP. Chem Eur J. 2005;11:4866–4880. doi: 10.1002/chem.200500076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kusumi T, Takahashi H, Xu P, Fukushima T, Asakawa Y, Hashimoto T, Kan Y, Inouye Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:4397–4400.Seco JM, Latypov S, Quinoa E, Riguera R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:2921–2924.Kouda K, Kusumi T, Ping X, Kan Y, Hashimoto T, Asakawa Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:4541–4544.Duret P, Waechter AI, Figadère B, Hocquemiller R, Cavé A. J Org Chem. 1998;63:4717–4720.(e) For a recent comparison of shielding effects of various Mosher-like derivatives, see Hoye TR, Erickson SE, Erickson-Birkedahl SL, Hale CRH, Izgu EC, Mayer MJ, Notz PK, Renner MK. Org Lett. 2010 doi: 10.1021/ol1003862. ASAP.

- 14.(a) Corey EJ, Shibata S, Bakshi RK. J Org Chem. 1988;53:2861–2863. [Google Scholar]; (b) Corey EJ, Helal CJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1998;37:1988–2012. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980817)37:15<1986::AID-ANIE1986>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Numbers are coded consistently in the paper as follows: R or S before the number indicates a stereocenter in the petrocortyne chain; R or S after the number indicates the stereocenter of the Mosher or NMA ester; rac, a mixture of true racemates; qrac, a mixture of quasiracemates; dim, a mixture of true diastereomers; qdim, a mixture of quasidiastereomers. Silyl tags are coded by letters: a, TIPSF9 = Si(iPr)2(CH2)3C4F9; b, TIPSF0 = Si(iPr)3; c, TIPSF7 = Si(iPr)2(CH2)3C3F7. When two letters are present, the O3 tag is listed before the O14 tag. For example, one of the four components of qdim-26a,b/a,c is 26a/c. This has the “a” tag on O3 and the “c” tag on O14.

- 16.Where possible, the chemical shifts were taken from the 1D spectra. When resonances overlapped in the 1D spectra, chemical shifts were taken from the proton axis of 1H,13C COSY (HMQC) spectra.

- 17.(a) Gao G, Moore D, Xie RG, Pu L. Org Lett. 2002;4:4143–4146. doi: 10.1021/ol026921r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Aschwanden P, Carreira EM. In: Acetylene Chemistry. Diederich F, Stang PJ, Tykwinski RR, editors. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2005. pp. 101–138. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sui B. PhD Thesis. University of Pittsburgh; 2009. The thesis can be downloaded in pdf form at: http://etd.library.pitt.edu/ETD-db/ETD-search/search. [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Petri AF, Schneekloth JS, Mandal AK, Crews CM. Org Lett. 2007;9:3001–3004. doi: 10.1021/ol071024e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Pojer PM, Angyal SJ. Aust J Chem. 1978;31:1031–1040. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Preliminary studies used the more common fluorous silyl tags with ethylene (rather than propylene) spacers, but these tags proved unstable. See: Garcia Sancho A, Wang X, Sui B, Curran DP. Adv Synth Catal. 2009;351:1035–1040. doi: 10.1002/adsc.200900061.

- 21.Curran DP, Moura-Letts G, Pohlman M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:2423–2426. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kondru RK, Wipf P, Beratan DN. Science. 1998;282:2247–2250. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.In comparing Mosher spectra, we discovered that the magnitudes of the subtraction values reported in Figure 3 of reference 5 are not correct. Assuming that the listed values are in ppb, they are exactly one-half of the actual subtraction values. The original resonances of the Mosher ester spectra are listed in the experimental section of the paper, and these data were used for the comparison. For the Mosher esters in reference 7, we compared our spectra with copies of the originals kindly provided by Dr. Jung. With his permission, these copies are included in the Supporting Information.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.