Abstract

Background

The majority of immigrants to Canada originate from the developing world, where the most rapid increase in prevalence of diabetes mellitus is occurring. We undertook a population-based study involving immigrants to Ontario, Canada, to evaluate the distribution of risk for diabetes in this population.

Methods

We used linked administrative health and immigration records to calculate age-specific and age-adjusted prevalence rates among men and women aged 20 years or older in 2005. We compared rates among 1 122 771 immigrants to Ontario by country and region of birth to rates among long-term residents of the province. We used logistic regression to identify and quantify risk factors for diabetes in the immigrant population.

Results

After controlling for age, immigration category, level of education, level of income and time since arrival, we found that, as compared with immigrants from western Europe and North America, risk for diabetes was elevated among immigrants from South Asia (odds ratio [OR] for men 4.01, 95% CI 3.82–4.21; OR for women 3.22, 95% CI 3.07–3.37), Latin America and the Caribbean (OR for men 2.18, 95% CI 2.08–2.30; OR for women 2.40, 95% CI: 2.29–2.52), and sub-Saharan Africa (OR for men 2.31, 95% CI 2.17–2.45; OR for women 1.83, 95% CI 1.72–1.95). Increased risk became evident at an early age (35–49 years) and was equally high or higher among women as compared with men. Lower socio-economic status and greater time living in Canada were also associated with increased risk for diabetes.

Interpretation

Recent immigrants, particularly women and immigrants of South Asian and African origin, are at high risk for diabetes compared with long-term residents of Ontario. This risk becomes evident at an early age, suggesting that effective programs for prevention of diabetes should be developed and targeted to immigrants in all age groups.

Although the prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus is generally higher in developed countries, it is increasing most rapidly in developing countries.1–3 The greatest relative increases in diabetes in the next 25 years are predicted to occur in the Middle Eastern crescent, sub-Saharan Africa and India.3 Approximately 250 000 individuals immigrate to Canada annually, the largest percentages from Asia, Africa and the Middle East.4

Beyond conventional risk factors for diabetes such as age and obesity, risk does not appear to be evenly distributed across ethnic groups. Apart from evidence that prevalence of diabetes is higher among persons of non-European ethnicity5–14 (who comprise the vast majority of immigrants to Canada), little is known about the epidemiology of diabetes among immigrants to Western countries. In ethnically and culturally heterogeneous countries like Canada, programs for prevention and control of diabetes could benefit from a greater understanding of the distribution of risk among different ethnic groups and newcomers from various regions of the world.

The purpose of our study was to determine the prevalence of diabetes among over one million immigrants to Ontario from various world regions, make comparisons to the prevalence in the long-term population of Ontario and examine the association of prevalence with sex, age, country of birth, time since arrival and socio-economic characteristics.

Methods

Data sources and study population

The Registered Persons Database, an electronic registry of all people who are eligible for health coverage in Ontario in a given year, was probabilistically linked to the Canadian Landed Immigrant Database (LIDS) maintained by Citizenship and Immigration Canada (linkage rate of 84%). From this data set, all adults age 20 years or older who were eligible for coverage under the province’s universal health insurance program on Mar. 31, 2005, were included in the study if they had a valid health card number and their date of birth was available. People in the study population who had been granted permanent residency status in Canada between 1985 and 2000 were defined as recent immigrants. The Canadian Landed Immigrant Database includes information collected at the time of application for immigrant status on education level, intended occupation, language ability, immigration category, sex and date of birth. The feasibility of linkage between this database and health-specific administrative data sets was tested in pilot projects,15 which showed that differences in linkage by immigration class, date of immigration, education and country of birth were not likely sufficient to produce significant bias in any study results. The data set has been previously used in Ontario to look at immunizations in children of immigrant mothers16 and at perinatal outcomes.17

We identified people who had been diagnosed with diabetes on or before Mar. 31, 2005, using the Ontario Diabetes Database, which is a validated administrative data registry created from hospital records and physician services claims. The database uses an algorithm of two primary care visits or one admission to hospital for diabetes within a two-year period to identify diagnosed cases of diabetes (excluding gestational diabetes). This algorithm has a sensitivity of 86% and a specificity of over 97% in identifying patients with confirmed diabetes.18

Given the absence of individual-level income-related information in both the immigration- and health-based data sets, we linked residential postal codes of 2005 to area-level income from the 2006 Canadian Census using the postal-code conversion file.19 The conversion file assigns relative income quintiles based on the smallest geographical unit for which census data are available, and is adjusted for household and community size. Because 98% of all immigrants to Canada between 1985 and 2000 settled in urban areas according to our data, our study excluded rural populations, which were defined as those with rural residential postal codes. Cities are home to the majority (85%) of the general Ontario population, which totalled 12 160 282 in the 2006 Census.20

Statistical analyses

We calculated age-adjusted point prevalence rates of diabetes by sex for recent immigrants and long-term residents on Mar. 31, 2005. For each population, sex-specific rates were also generated by age group (20–34 years, 35–49 years, 50–64 years, 65–74 years, and 75 years or older) and, for the immigrant population, by country of birth and world region (based on the World Bank schema, available at http://go.worldbank.org/FFZ0CTE2V0). The 15 countries that experienced the highest prevalence of diabetes were also identified. We used direct age-standardization to the 1991 Canada Census population to adjust for differences in population distribution across different world regions.

We used logistic regression to estimate the association of risk factors with prevalence of diabetes. These risk factors included age, sex, world region of birth, pre-migration level of education, post-migration area level of income, immigration visa category and time since arrival in Canada. Categories used to define level of education at time of immigration were no education, secondary (high school) level or lower, non-university qualifications (including diplomas or certificates from institutions not qualifying as universities, apprenticeships and other non-university post-secondary education), some university, and university education or higher. To examine risk by region of birth, immigrants from North America and Western Europe were used as a comparator. Given that point prevalence was measured in 2005 and immigration records were only available up until 2000, we were unable to evaluate risk among those living in Canada for less than five years.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

We included 1 122 771 recent immigrants and 7 503 085 long-term residents who met eligibility criteria. The characteristics of both the recently immigrated and long-term resident populations are listed in Table 1. Compared with long-term residents, immigrants tended to be younger and were more likely to live in lower-income neighbourhoods. Recent immigrants originated predominantly from East-Asia (27.5%), South Asia (19.4%), and Latin America and the Caribbean (15.8%).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study populations of long-term residents of Ontario* and recent immigrants to Ontario† in 2005

| Characteristic | Long-term residents n = 7 503 085 | Recent immigrants n = 1 122 771 |

|---|---|---|

| Median age, yr‡ | 47 | 43 |

| Age ≥ 65 yr, %‡ | 18.2 | 10.2 |

| Men, % | 49.3 | 49.5 |

| Income quintile of neighbourhood of settlement, %§ | ||

| Q1 (lowest income) | 18.2 | 26.4 |

| Q2 | 19.6 | 21.7 |

| Q3 | 19.7 | 19.7 |

| Q4 | 20.4 | 18.8 |

| Q5 | 21.2 | 13.0 |

| World region of birth, no. (%) | ||

| East Asia and Pacific | 309 043 (27.5) | |

| South Asia | 217 367 (19.4) | |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 177 191 (15.8) | |

| Eastern Europe and Central Asia | 167 456 (14.9) | |

| Western Europe and North America | 98 931 (8.8) | |

| North Africa and Middle East | 87 610 (7.8) | |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 64 367 (5.7) | |

| Unknown or stateless | 795 (0.07) | |

| None specified | 11 (0.001) | |

| Immigration visa category, no. (%) | ||

| Family | 448 142 (39.9) | |

| Economic: skilled, independent | 285 322 (25.4) | |

| Refugee | 184 588 (16.4) | |

| Economic: skilled, family | 124 465 (11.1) | |

| Economic: business | 54 056 (4.8) | |

| Other | 26 185 (2.3) | |

| None specified | 13 (0.001) | |

| Educational level at landing, no. (%) | ||

| No education | 47 604 (4.2) | |

| Secondary level or less | 608 925 (54.2) | |

| Non-university qualifications | 171 106 (15.2) | |

| Some university | 56 021 (5.0) | |

| University degree or higher | 239 031 (21.3) | |

| None specified | 84 (0.007) | |

| Years since arrival, no. (%) | ||

| 5–9 years | 322 047 (28.7) | |

| 10–14 years | 384 608 (34.2) | |

| ≥ 15 years | 416 116 (37.1) | |

Limited to residents of urban areas, based on the first three characters of postal codes of residence (i.e., forward sortation areas).

Comprises those eligible for provincial health care based on administrative databases. The recent-immigrant population includes those who obtained legal landed status between 1985 and 2000.

Based on age as of Mar. 31, 2005.

2001 census income information was applied based on the individual’s postal code of residence in 2005.

Trends in diabetes prevalence

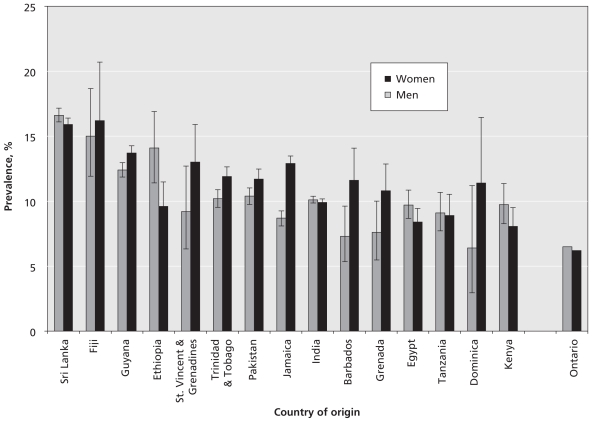

Immigrants from South Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, sub-Saharan Africa, and North Africa and the Middle East all experienced significantly higher rates of diabetes than long-term residents of Ontario (Figure 1). The 15 countries of birth (out of 239 countries and geopolitical regions) that were associated with the highest rates of diabetes among both sexes were found in South Asia, the Pacific Islands, Latin America, the Caribbean and Africa (Figure 2). Among long-term residents, men displayed higher rates of diabetes than women (6.5% versus 6.2%), but women who were recent immigrants had rates equal to or higher than immigrant men from the same regions, with the exception of women from sub-Saharan Africa.

Figure 1.

Age-adjusted, sex-specific prevalence of diabetes (with 95% confidence intervals) in 2005 among recent immigrants by world region of origin and among long-term residents of Ontario.

Figure 2.

Age-adjusted, sex-specific prevalence of diabetes (with 95% confidence intervals) in 2005 among recent immigrants to Ontario from the 15 countries of origin with the highest prevalence and among long-term residents of Ontario.

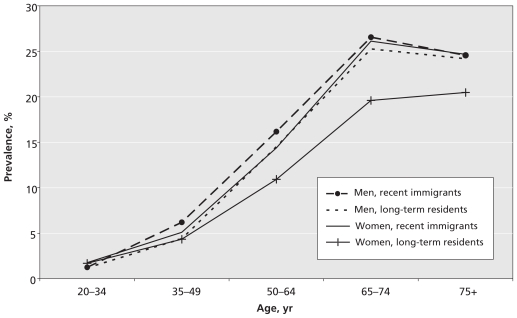

Overall, immigrants of both sexes had statistically higher rates of diabetes than long-term residents at all ages (except men aged 75 or older), with a large disparity between women who were recent immigrants and women who were long-term residents (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Age-specific prevalence of diabetes in 2005 among recent immigrants to and long-term residents of Ontario, by sex.

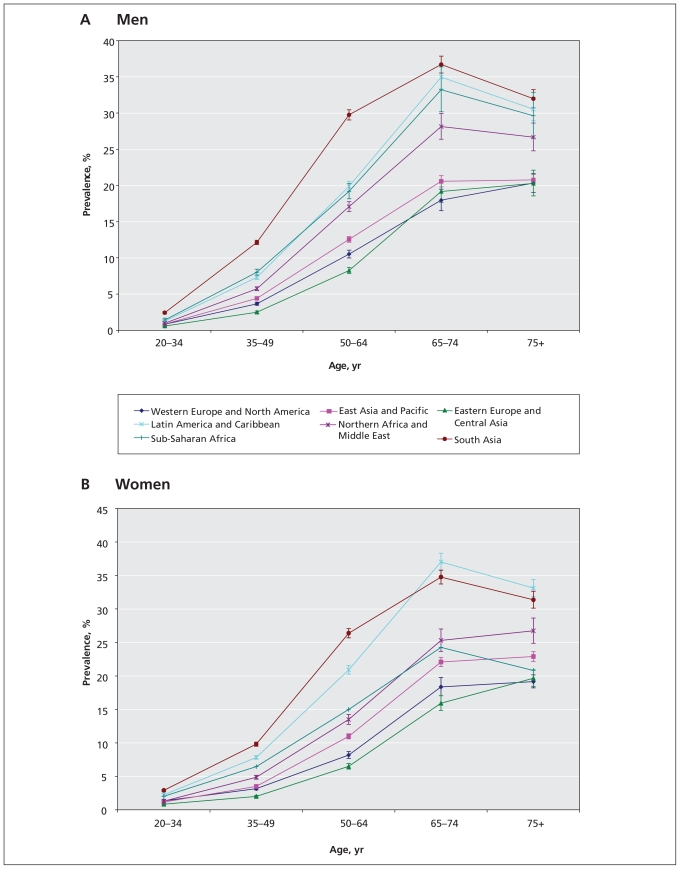

The prevalence of diabetes increased sharply with age until age 75 in both sexes and among both recent immigrants and long-term residents (Figure 4). Increased prevalence of diabetes became evident at a young age and was evident across all age groups among immigrants from the regions of highest risk. Across all age groups, men from South Asia had the highest prevalence rates, followed by men from Latin America and the Caribbean and from sub-Saharan Africa (Figure 4a). Women from Latin America and the Caribbean and from South Asia had the highest prevalence rates by age (Figure 4b). The lowest rates were found among men and women from Europe, North America and Central Asia.

Figure 4.

Age-specific prevalence of diabetes among men (A) and among women (B) in 2005, by world region of birth.

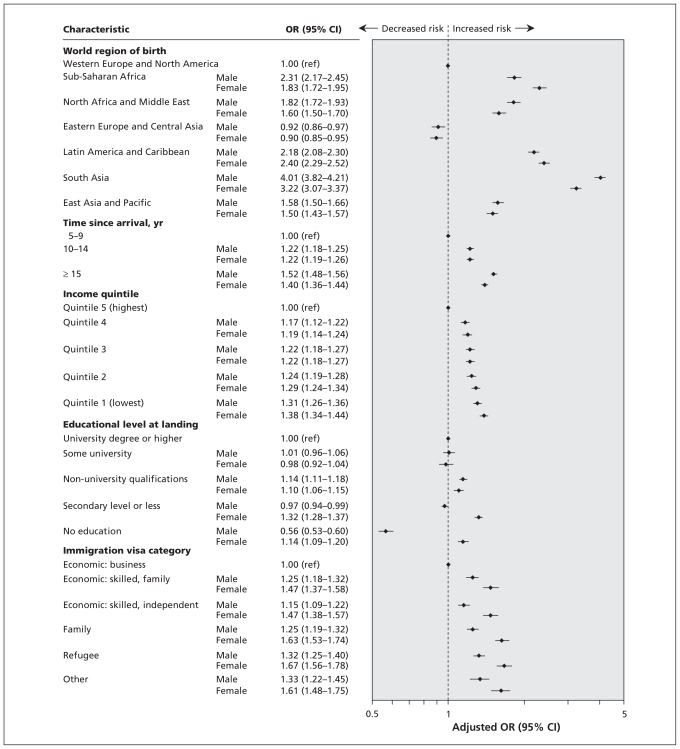

After controlling for age, immigration category, education, income level and time since arrival, we found significantly higher rates of diabetes among men (OR 4.01, 95% CI 3.82–4.21) and women (OR 3.22, 95% CI 3.07–3.37) from South Asia compared with immigrants from Western Europe and North America (Figure 5). The next highest risk was evident among men (OR 2.18, 95% CI 2.08–2.30) and women (OR 2.40, 95% CI 2.29–2.52) from Latin America and the Caribbean and among men (OR 2.31, 95% CI 2.17–2.45) and women (OR 1.83, 95% CI 1.72–1.95) from sub-Saharan Africa.

Figure 5.

Risk of diabetes among recent immigrants to Ontario in 2005, by sex. An odds ratios (OR) greater than 1.0 indicates an increased risk of diabetes. CI = confidence interval.

An income gradient was observed, whereby lower income was associated with higher risk (OR 1.31, 95% CI 1.26–1.36 for men and OR 1.38, 95% CI 1.33–1.44 for women in the lowest, relative to the highest, income quintile). Women with secondary-level education or lower had higher risk compared to those with a university degree or higher (OR 1.32, 95% CI 1.28–1.37). Men with no education had the lowest risk of diabetes (OR 0.56, 95% CI 0.53 – 0.60).

The multiple logistic regression model also showed a gradient for time since arrival, with the highest prevalence of diabetes among men (OR 1.52, 95% CI 1.48–1.56) and women (OR 1.40, 95% CI 1.36–1.44) living in Canada for 15 years or more compared to those living in Canada for 5–9 years.

Interpretation

Our study used a unique population-based data set in a setting with high rates of immigration to describe the epidemiology of diabetes among a heterogeneous immigrant population. The increased relative rates of diabetes we observed among immigrants from South Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, and North Africa and the Middle East are particularly striking given that the population of Ontario is itself highly diverse ethnically. We also found that the risk among immigrants from South Asia was at least triple that of immigrants from Western Europe and North America, and the risk among immigrants from Latin America and the Caribbean and from sub-Saharan Africa was roughly double, even after controlling for age, sex, time since arrival, income level and immigration-related variables.

Our findings support those of three previous Canadian studies that found immigrants from South Asia had two to three times the rate of diabetes as compared with the overall Ontario population, with the white population in Ontario or with a sample of Canadians of European heritage.21–23 All of these studies were based either on data from health surveys21,22 or on a relatively small population sample.23 Further, all three were focused on ethnic differences in diabetes in the population overall and did not look at immigration status. Research conducted in the United Kingdom found that people of South Asian ethnicity had prevalence rates of diabetes that were three to six times the rates in the white British population, which is consistent with our findings.7 Our prevalence estimates are higher than those generated in 2004 by the World Health Organization, which used data derived from a small number of studies (some of which were outdated) and were based on extrapolations and assumptions likely to lead to underestimations of risk.3

A detailed description of risk for diabetes by age and sex among immigrants to Western countries has previously been lacking. Although prevalence of diabetes is generally higher among men than women,3,24 recently immigrated women in our study had prevalence rates that were roughly equivalent to or higher than men from the same countries. Particularly high rates were evident among women from Latin America and the Caribbean relative to men. This pattern of elevated risk among women relative to men has been previously described only in areas with high proportions of Aboriginal populations.25 We also found that the largest disparity in risk existed between women who were recent immigrants and women who were long-term residents. These findings suggest that recently immigrated women may be at particularly high risk for diabetes. Combined with the social isolation and barriers to access of services experienced by many recently immigrated women,26 this higher risk may raise important health-related issues for immigrant women and should be of concern to health providers and planners.

We also found an age-related disparity in prevalence of diabetes between the highest- and lowest-risk immigrant groups. This disparity became apparent in young adulthood (by age 35 years among South Asians) and increased with age. By age 65 years, more than a third of men and women from these regions had diabetes. Above age 75 years, a plateau or decrease in risk was observed among people from all regions, which has also been described previously in the general Canadian population.24

We found that risk for diabetes increased with time since arrival. An increase in the prevalence of chronic disease and declining health status over time since immigration has been previously described in the Canadian literature based on health-survey data.27–29 Many possible causes of this observed deterioration in health status over time have been suggested, including uptake of unhealthy behaviours, acculturation-related stress, decreased social, economic and political status, barriers to access of preventive services, and competing priorities resulting in reduced self-care.28

Socio-economic status is known to have an inverse relationship with risk for diabetes,31,31 and low education has been identified as a correlate of higher diabetes rates in Canada.21 In our study, we found an interaction between sex and education, whereby low educational attainment (i.e., less than a high school diploma) was a significant independent risk factor for diabetes among immigrant women, but little or no formal education was protective for immigrant men. The latter could reflect more physically demanding employment (e.g., manual labour) among men in this group. We also observed an inverse relationship between income and risk for diabetes among women, as has been described before in Canada.21 One explanation for this may be that higher rates of obesity are reported among women with low socio-economic status than among men.32

Limitations

High rates of diabetes in specific ethnic migrant groups are likely attributable to a complex interplay of genetic and environmental factors, including acculturation, stress, social isolation, and employment and economic challenges.33 Despite the limitations of our data in addressing social and experiential exposures, it must be noted that strong ethnic differences continued to be apparent even after controlling for certain pre-migration (i.e., country of birth, immigrant category and education) and post-migration (i.e., neighbourhood income level, time since arrival) factors.

Additional limitations of this study are related to the use of administrative data. Although we were unable to differentiate type 1 from type 2 diabetes in the administrative data, the former represents a very small proportion of all diabetes (5%–10%) and is therefore unlikely to have biased our results.34 Administrative data may also underestimate the prevalence of diabetes. Studies in other jurisdictions suggest that up to 30% of diabetes in the population may be undiagnosed,35 and it is possible that the probability of diagnosis may differ by immigration status and country of birth. Finally, a small proportion (less than 5%) of health services that are not billed on a fee-for-service basis would not have been captured in our data.36

Conclusions

We found that recent immigrants from South Asia, the Caribbean, South America and Africa are at much higher risk for diabetes than both long-term residents of Ontario and recent immigrants from Europe, North America and Central Asia. This risk becomes evident in young adulthood and continues throughout the life course. The largest disparity in risk between immigrants and the general population was observed among women, the etiology of which should be further explored. Risk increased with time since immigration, but ethnic differences persisted even after controlling for this variable, suggesting that acculturation and transition to a “westernized” diet and lifestyle contributes to and may exacerbate, but does not explain, these differences. Although a few studies have shown promising results, lifestyle-related interventions targeted to recent immigrants should be explored further.37 Our findings could aid policy-makers and planners in the development of specific guidelines for screening and targeted, community-level educational programs on diabetes. Finally, our study highlights the critical importance for population-health research using data routinely collected on immigration status and ethnicity.

Acknowledgements

Data were provided by Citizenship and Immigration Canada and the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES). The authors thank Alex Kopp and Nadia Gunraj for preparing the data.

Footnotes

Funding: Financial support was provided by St. Michael’s Hospital. The Canadian Population Health Initiative of the Canadian Institute for Health Information, Citizenship and Immigration Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) sponsored the data linkage for this study. This study was also supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred. No external funding was received for this study.

Previously published at www.cmaj.ca

Competing interests: None declared.

Contributors: All of the authors contributed to the conception and design of the study. Richard Glazier and Douglas Manuel supervised the study. Marie DesMeules and Sarah McDermott contributed to the acquisition of data and creation of the linked data sets. Rahim Moineddin and Maria Creatore contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data. Maria Creatore drafted the manuscript, and the other authors critically revised it for important intellectual content. All of the authors approved the final version of the manuscript submitted for publication.

This article has been peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.International Diabetes Federation (IDF) Diabetes Atlas, second edition. Brussels (Belgium): The Federation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramachandran A, Mary S, Yamuna A, et al. High prevalence of diabetes and cardiovascular risk factors associated with urbanization in India. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:893–8. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, et al. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1047–53. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Facts and figures 2006: immigration overview. Ottawa (ON): Citizenship and Immigration Canada; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McBean AM, Li S, Gilbertson DT, et al. Differences in diabetes prevalence, incidence, and mortality among the elderly of four racial/ethnic groups: whites, blacks, hispanics, and asians. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2317–24. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.10.2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Bowman BA, et al. Diabetes trends in the US: 1990–1998. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1278–83. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.9.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mather HM, Keen H. The Southall Diabetes Survey: prevalence of known diabetes in Asians and Europeans. BMJ. 1985;291:1081–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.291.6502.1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abate N, Chandalia M. Ethnicity and type 2 diabetes: focus on Asian Indians. J Diabetes Complications. 2001;15:320–7. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8727(01)00161-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tillin T, Forouhi N, Johnston DG, et al. Metabolic syndrome and coronary heart disease in South Asians, African-Caribbeans and white Europeans: a UK population-based cross-sectional study. Diabetologia. 2005;48:649–56. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1689-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rotimi CN, Cooper RS, Okosun IS, et al. Prevalence of diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in Nigerians, Jamaicans and US blacks. Ethn Dis. 1999;9:190–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dowse GK, Gareeboo H, Zimmet PZ, et al. High prevalence of NIDDM and impaired glucose tolerance in Indian, Creole, and Chinese Mauritians. Mauritius Noncommunicable Disease Study Group. Diabetes. 1990;39:390–6. doi: 10.2337/diab.39.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujimoto WY, Bergstrom RW, Boyko EJ, et al. Diabetes and diabetes risk factors in second- and third-generation Japanese Americans in Seattle, Washington. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1994;24(Suppl):S43–52. doi: 10.1016/0168-8227(94)90226-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franco LJ. Diabetes in Japanese-Brazilians–influence of the acculturation process. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1996;34(Suppl):S51–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hara H, Egusa G, Yamakido M, et al. The high prevalence of diabetes mellitus and hyperinsulinemia among the Japanese-Americans living in Hawaii and Los Angeles. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1994;24(Suppl):S37–42. doi: 10.1016/0168-8227(94)90225-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kliewer F, Kazanjian A. The health status and medical services utilization of recent immigrants to Manitoba and British Columbia: A pilot study. Vancouver (BC): University of British Columbia; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guttmann A, Manuel D, Stukel TA, et al. Immunization coverage among young children of urban immigrant mothers: findings from a universal health care system. Ambul Pediatr. 2008;8:205–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Urquia ML, Frank JW, Glazier RH, et al. Neighborhood context and infant birth-weight among recent immigrant mothers: a multilevel analysis. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:285–93. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.127498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hux JE, Ivis F, Flintoft V, et al. Diabetes in Ontario: determination of prevalence and incidence using a validated administrative data algorithm. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:512–6. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.3.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilkins R. PCCF+ Version 5D User’s Guide Automated Geographic Coding Based on the Statistics Canada Postal Code Conversion Files, Including Postal Codes through September 2008. Ottawa (ON): Health Information and Research Division, Statistics Canada; 2009. Cat. no. 82F0086-XDB. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Statistics Canada. Population and Dwelling Count Highlight Tables. 2006 Census. Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; 2007. 2007. Population counts for Canada, provinces and territories, census divisions and census subdivisions (municipalities), by urban and rural, 2006 Census: 100% data (table) Cat. no. 97-550-XWE2006002. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manuel DG. Schultz. Diabetes health status and risk factors. In: Hux JE, Booth GL, Slaughter PM, et al., editors. Diabetes in Ontario. Toronto (ON): Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2003. pp. 77–94. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shah BR. Utilization of physician services for diabetic patients from ethnic minorities. J Public Health (Oxf) 2008;30:327–31. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdn042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anand SS, Yusuf S, Vuksan V, et al. Differences in risk factors, atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular disease between ethnic groups in Canada: the Study of Health Assessment and Risk in Ethnic Groups (SHARE) Lancet. 2000;356:279–84. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02502-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Public Health Agency of Canada. Diabetes in Canada: highlights from the National Diabetes Surveillance System, 2004–2005. Ottawa (ON): The Agency; 2008. [(accessed 2010 Feb. 3)]. Available: www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/2008/dicndss-dacsnsd-04-05/index-eng.php. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Young TK, Reading J, Elias B, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in Canada’s first nations: status of an epidemic in progress. CMAJ. 2000;163:561–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bierman AS, Angus J, Ahmad F, et al. Access to Health Care Services. In: Bierman AS, editor. Project for an Ontario Women's Health Evidence-Based Report: Vol 1. Toronto (ON): St Michael’s Hospital and the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pérez C. Health status and health behaviours among immigrants. Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; 2002. [(accessed 2010 Feb. 3)]. Cat. no. 82-003. Available: www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/82-003-s/2002001/pdf/82-003-s2002005-eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newbold KB. Self-rated health within the Canadian immigrant population: risk and the healthy immigrant effect. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:1359–70. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dunn JR, Dyck I. Social determinants of health in Canada’s immigrant population: Results from the national population health survey. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51:1573–93. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brancati FL, Whelton PK, Kuller LH, et al. Diabetes mellitus, race, and socioeconomic status. A population-based study. Ann Epidemiol. 1996;6:67–73. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(95)00095-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robbins JM, Vaccarino V, Zhang H, et al. Socioeconomic status and type 2 diabetes in African American and non-Hispanic white women and men: evidence from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:76–83. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.1.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matheson FI, Moineddin R, Glazier RH. The weight of place: a multilevel analysis of gender, neighborhood material deprivation and body mass index among Canadian adults. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:675–90. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Misra A, Ganda OP. Migration and its impact on adiposity and type 2 diabetes. Nutrition. 2007;23:696–708. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.International Diabetes Federation. Diabetes facts and figures: types of diabetes. Brussels (Belgium): The Federation; 2009. [(accessed 2009 Nov. 24)]. Available: www.idf.org/node/1052?unode=3B9689B0-C026-2FD3-879219B2881892E7. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harris MI, Eastman RC. Early detection of undiagnosed diabetes mellitus: a US perspective. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2000;16:230–6. doi: 10.1002/1520-7560(2000)9999:9999<::aid-dmrr122>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams JI, Young W. Appendix: a summary of studies on the quality of administrative databases in Canada. In: Goel V, Williams JI, Anderson GM, et al., editors. Patterns of health care in Ontario. The ICES Practice Atlas. 2nd ed. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Medical Association; 1996. pp. 339–46. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Renzaho AM, Mellor D, Boulton K, et al. Effectiveness of prevention programmes for obesity and chronic diseases among immigrants to developed countries – a systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13:438–50. doi: 10.1017/S136898000999111X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]