Abstract

Redox-based mechanisms play critical roles in the regulation of multiple cellular functions. NF-κB, a master regulator of inflammation, is an inducible transcription factor generally considered to be redox-sensitive, but the modes of interactions between oxidant stress and NF-κB are incompletely defined. Here, we show that oxidants can either amplify or suppress NF-κB activation in vitro by interfering both with positive and negative signals in the NF-κB pathway. NF-κB activation was evaluated in lung A549 epithelial cells stimulated with tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), either alone or in combination with various oxidant species, including hydrogen peroxide or peroxynitrite. Exposure to oxidants after TNFα stimulation produced a robust and long lasting hyperactivation of NF-κB by preventing resynthesis of the NF-κB inhibitor IκB, thereby abrogating the major negative feedback loop of NF-κB. This effect was related to continuous activation of inhibitor of κB kinase (IKK), due to persistent IKK phosphorylation consecutive to oxidant-mediated inactivation of protein phosphatase 2A. In contrast, exposure to oxidants before TNFα stimulation impaired IKK phosphorylation and activation, leading to complete prevention of NF-κB activation. Comparable effects were obtained when interleukin-1β was used instead of TNFα as the NF-κB activator. This study demonstrates that the influence of oxidants on NF-κB is entirely context-dependent, and that the final outcome (activation versus inhibition) depends on a balanced inhibition of protein phosphatase 2A and IKK by oxidant species. Our findings provide a new conceptual framework to understand the role of oxidant stress during inflammatory processes.

Keywords: Inflammation, NF-κB, Oxidative Stress, Phosphatase, Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF)

Introduction

Oxidant stress is a critical pathophysiological mechanism that stands at the foreground of a number of inflammatory diseases. In such conditions, highly reactive oxygen and nitrogen species exert their biological activity by inflicting various oxidative damages to biomolecules and by modulating the activity of redox-sensitive signal transduction pathways (1). The transcription factor nuclear factor κB (NF-κB)2 is a master regulator of inflammation and apoptosis, which is considered a prototypical example of such sensitivity to oxidant stress (2). NF-κB is a family of dimeric proteins normally retained in the cytoplasm of nonstimulated cells, bound to inhibitory proteins, the IκBs (3). The critical step in NF-κB activation relies on its dissociation from the IκB protein, resulting from stimulus-induced phosphorylation of IκB, followed by its polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. IκB itself is phosphorylated by IκB kinase (IKK), composed of a heterodimer of two catalytic subunits, IKKα/β, and a regulatory subunit, IKKγ (4). A considerable variety of stimuli lead to IKK activation and downstream NF-κB signaling, comprising inflammatory cytokines, various microbial components, as well as genotoxic, physical, or chemical stress factors (5).

Since the first report by Schreck et al. (6) that NF-κB could be activated directly by H2O2 in a subclone of Jurkat cells, a number of experimental studies have lent support to the concept that NF-κB activation is mediated via a redox-based mechanism (for review, see Ref. 2). The underlying molecular mechanisms were shown to involve either IKK-dependent IκBα serine phosphorylation (7) or tyrosine phosphorylation of IκBα at Tyr42 (8). Recently however, the sensitivity of NF-κB to oxidant stress has been brought into question by a series of investigations showing that oxidant stress activates NF-κB only in some, but not all cell types (for review, see Ref. 9). Furthermore, several recent studies, including our own, have indicated that oxidants such as H2O2 (10–12) or peroxynitrite (PN) (13) repressed NF-κB activation by inflammatory cytokines in several cell systems in vitro, through a mechanism involving oxidative modification of the upstream kinase IKK. Similar inhibition of IKK has also been observed with various biochemical agents triggering oxidation of cysteine 179 in IKKβ (14–16). Thus, NF-κB modulation by oxidants appears largely unpredictable and dependent on the cell type studied and the kind of redox stimulus.

An essential aspect of NF-κB signaling is its transient nature, which requires short term activation and tight regulation by negative feedback loops (17). Given the multiplicity of their biological targets, oxidants might be able to modulate both positive and negative signals in the NF-κB pathway, and the balance between these contrasted influences might dictate the final outcome (activation or inhibition) on NF-κB. To address this hypothesis, lung A549 cells were stimulated with TNFα before or after a short exposure to oxidant stress conditions. Preexposure to oxidant stress prevented TNFα-mediated NF-κB activation by impairing IKK phosphorylation, whereas postexposure to oxidant stress markedly increased and prolonged TNFα-mediated NF-κB activation by suppressing phosphatase-dependent IKK dephosphorylation. Thus, oxidants can inactivate both kinases and phosphatases in the NF-κB signaling pathway and may thereby either suppress or amplify TNFα-dependent NF-κB activation. These findings provide novel insights into the mechanisms of NF-κB regulation in conditions of oxidant stress.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and Stimulation

Human lung carcinoma epithelial A549 cells and murine fibrosarcoma L929 cells were grown (5% CO2, 37 °C) in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin. Oxidant stress conditions were realized by exposing cells to the potent oxidant PN (1). In some experiments, the reactive oxygen species hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was used instead of PN. PN (Calbiochem) was synthesized as described (18) and used along a previously established protocol (13, 19). Briefly, PN was delivered to the cells (in PBS-glucose medium) at a final concentration of 10–500 μm. In the preexposure protocol, cells were exposed to PN (or H2O2) for the indicated times, washed in PBS-glucose, and replaced in culture medium for stimulation with 10 ng/ml human TNFα (Pierce). In some experiments, human IL-1β (PreproTech, London, UK) was used (1 ng/ml) instead of TNFα. In the postexposure protocol, cells were first stimulated with TNFα for the indicated times, washed in PBS-glucose, and then treated with PN (or H2O2) for various periods, as indicated. In specified protocols, the protein phosphatase inhibitor okadaic acid (OA; 100 nm) was used in place of the oxidants, as indicated.

To mimic the postexposure protocol described above in a physiologically relevant condition, separate experiments were conducted in L929 cells stimulated with TNFα. Indeed, these cells are known to produce large amounts of reactive oxygen species upon TNFα stimulation (20, 21). L929 cells were stimulated with 10 ng/ml TNFα for 1 h. The role of endogenously produced oxidants was evaluated by pretreating cells with the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine (25 mm) to prevent the accumulation of reactive oxygen species.

Preparation of Protein Extracts, SDS-PAGE, and Western Immunoblotting

Cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts were obtained as described (13). Thirty μg of cytoplasmic or 10 μg of nuclear proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, followed by standard immunoblotting protocol, using the following primary antibodies: anti-NF-κB RelA/p65, anti-IκBα (both from Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-IKKα, anti-IKKβ, anti-phospho-IKKα/β, and anti-α-tubulin (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA), and followed by incubation with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Bio-Rad).

Electromobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

EMSA was performed as described in detail, following incubation (20 min) of 10 μg of nuclear proteins with an [α-32P]dCTP-labeled NF-κB probe (5′-AGTTGAGGGGACTTTCCCAGG-3′) in EMSA buffer (13).

NF-κB Gene Reporter Assay

Cells were transiently transfected with 1 μg of a multimeric NF-κB pGL2 luciferase vector and 0.1 μg of the Renilla pRL-TK vector. Luciferase activity was determined and normalized as detailed in Ref. 13.

Immunoprecipitation and IKK Assay

IKK was immunoprecipitated, and the kinase reaction was performed by adding 1 μg of recombinant glutathione S-transferase-IκBα and 5 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP for 30 min at 30 °C, according to our previously published procedures (13). Proteins were separated on a 12% polyacrylamide gel, and gels were fixed, dried, and examined by autoradiography.

Quantification of IL-8 production

The concentration of IL-8 was determined in the medium of A549 cells stimulated with TNFα for 1 h followed by a 4-h posttreatment with H2O2, using a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Protein Phosphatase 2A Assay

PP2A activity was determined with the serine-threonine phosphatase assay system obtained from Promega, using the PP2A-specific reaction buffer. A549 cells in 6-well plates were left untreated or were treated with PN (500 μm) or the PP2A inhibitor OA (100 nm) for 30, 60, or 90 min. Cells were then lysed, cleared by centrifugation (100,000 × g, 4 °C, 1 h), and supernatants were passed through Sephadex G-25 spin columns to remove free phosphate. 35 μl of the phosphate-free lysate was then incubated on a 96-well plate together with 5 μl of the phosphopeptide substrate RRA(pT)VA and 10 μl of PP2A-specific buffer for 30 min at 30 °C. After addition of a molybdate complex dye, formation of molybdate malachite green-phosphate complex was monitored at 600 nm (pmol of phosphate/μg of protein/min), and PP2A activity was expressed as a percentage of control conditions. In some experiments, the reaction was done directly in crude cell extracts obtained from untreated cells, in the presence of PN (500 μm) or OA (100 nm).

Statistical Analysis

Densitometric analyses of blots are shown as mean ± S.E. Comparisons were done by analysis of variance and Bonferroni adjustment. A p < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Oxidants and TNFα Activate NF-κB with Different Time Courses

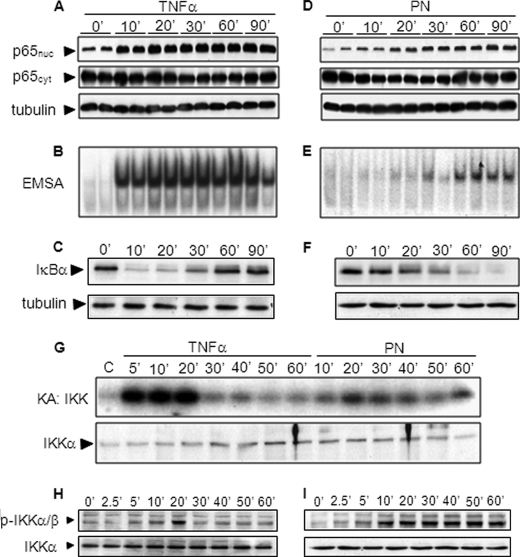

Stimulation of A549 cells with TNFα triggered the early (10 min) nuclear translocation of NF-κB p65 and rapidly enhanced NF-κB-DNA binding activity (Fig. 1, A and B). In agreement with the classical mechanism of NF-κB activation, these effects were correlated with the early degradation of IκBα after 10 and 20 min, followed by a secondary increase of the IκBα signal starting at 30 min (Fig. 1C), consistent with IκBα resynthesis for negative feedback (13). PN also activated NF-κB, albeit with different intensity and time course than TNFα. Indeed, p65 nuclear translocation and NF-κB-DNA binding were weaker and occurred later after PN, starting only after 20–30 min, and were associated with a delayed degradation of IκBα (Fig. 1, D–F). In contrast to TNFα, there was no detectable IκBα resynthesis up to 90 min after PN.

FIGURE 1.

Oxidants and TNFα activate NF-κB with different time courses. A549 cells were stimulated with 10 ng/ml TNFα or 500 μm PN. A and D, cytoplasmic or nuclear p65 as well as tubulin were detected by Western blotting. B and E, NF-κB-DNA binding activity was determined by EMSA. C and F, IκBα levels were determined by Western blotting. G, IKK activity was determined by the IKK assay (KA). H and I, total and phosphorylated IKKα/β were determined by Western blotting.

Given that the signal for IκBα degradation is triggered by the activity of the upstream kinase IKK, we explored the influence of TNFα and PN on IKK activity. As illustrated in Fig. 1G, TNFα promoted rapid and robust activation of IKK that was sustained for 20 min followed by return to baseline activity. In contrast, PN induced a much weaker activation of IKK, which did not dissipate over time and remained sustained for 60 min. The initiation of IKK activity being mediated by its phosphorylation at 2 serine residues, we determined whether the different time courses of IKK activation by PN and TNFα were associated with differences in IKK phosphorylation. As shown in Fig. 1H, IKK phosphorylation triggered by TNFα started after 5 min, peaked after 10 and 20 min, and then progressively returned to baseline levels, consistent with phosphatase-dependent IKK dephosphorylation (22). IKK was also phosphorylated in response to PN after 5–10 min, but, contrary to TNFα, such phosphorylation failed to be reversed and was maintained over 60 min.

Postexposure to Oxidant Stress Conditions Amplifies TNFα-dependent NF-κB Activation

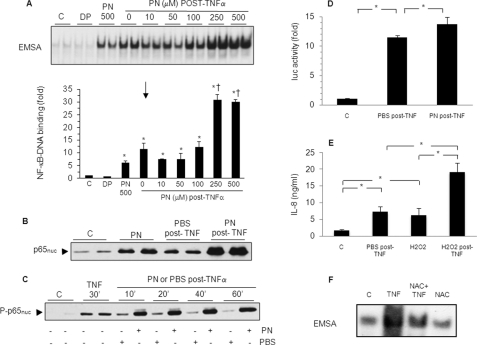

Cells were first stimulated for 30 min with TNFα to induce NF-κB activation and were subsequently treated with PN for 1 h. As indicated in Fig. 2A, such a sequence led to a significant enhancement of NF-κB-DNA binding activity, at concentrations of PN of 250 and 500 μm for 1 h. Control experiments using decomposed PN showed no effect. A comparable increase in NF-κB-DNA binding activity was observed when H2O2 was used instead of PN (supplemental Fig. S1). Similarly, p65 nuclear translocation was markedly enhanced by 500 μm PN for 1 h compared with a posttreatment with the PBS-glucose buffer (Fig. 2B). This was associated with an increased Ser536 phosphorylation of nuclear p65, an effect that was detected as early as 10 min after the addition of PN in time course experiments (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, the expression of NF-κB-dependent genes was also affected by postexposure to oxidants. As indicated in Fig. 2D, NF-κB-dependent luciferase activity induced by TNFα was significantly enhanced by postexposure to 500 μm PN (Fig. 2D). In addition, the secretion of IL-8 (Fig. 2E) induced by TNFα was significantly greater when cells were exposed to H2O2 (500 μm) after TNFα. Finally, the role of endogenous oxidants on the process of NF-κB activation was also evaluated in L929 cells, which generate reactive oxygen species when stimulated with TNFα. As shown in Fig. 2F, NF-κB activation triggered by TNFα in L929 cells was largely reduced by the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine, indicating that oxidants produced in response to TNFα amplify the process of NF-κB activation in these cells.

FIGURE 2.

Postexposure to oxidants amplifies TNFα-dependent NF-κB activation. A549 cells were unstimulated (control, c) or stimulated with decomposed PN for 1 h (DP), with 500 μm PN for 1 h, with 10 ng/ml TNFα for 30 min followed by 0–500 μm PN for 1 h (PN post-TNF), or with 10 ng/ml TNFα for 30 min followed by PBS buffer for 1 h (PBS post-TNF). A, NF-κB-DNA binding activity was determined by EMSA and was quantified by densitometry (*, p < 0.05 versus c. †, p < 0.05 versus TNFα + PN 0). B and C, nuclear p65 and nuclear phosphorylated p65 were determined by Western blotting. D, A549 cells were transiently co-transfected with a plasmid bearing NF-κB-firefly luciferase reporter gene and with a plasmid bearing Renilla luciferase. Transfected cells were unstimulated (c), stimulated with 10 ng/ml TNFα for 30 min followed by PBS (PBS post-TNFα) or by 500 μm PN (PN post-TNF) for 1 h and then replaced in medium for 3 additional h. Luciferase activity was measured in cell lysates (*, p < 0.05). E, IL-8 (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) in the medium of unstimulated cells (control c), or after stimulation with 10 ng/ml TNFα (30 min) followed by PBS for 4 h (PBS post-TNF) or with 10 ng/ml TNFα (30 min) followed by 500 μm H2O2 for 4 h (H2O2 post-TNF), or with 500 μm H2O2 alone for 4 h (*, p < 0.05) is shown. F, L929 cells were unstimulated (control, c) or were stimulated with 10 ng/ml TNFα for 1 h, with 25 mm N-acetylcysteine for 1 h followed by 10 ng/ml TNFα for 1 h (NAC+TNF) or with 25 mm N-acetylcysteine alone for 1 h (NAC). NF-κB-DNA binding activity was determined by EMSA. Error bars indicate S.E.

Postexposure to Oxidant Stress Conditions Prevents IKK Dephosphorylation, Leading to Prolonged Activation of IKK and Sustained IkBα Degradation

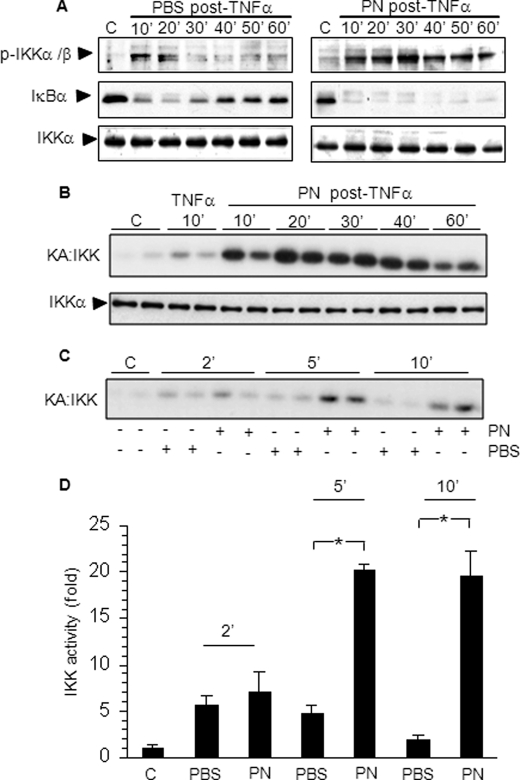

To explore the mechanisms of oxidant stress-dependent amplification of NF-κB activation by TNFα, we determined the influence of PN on the upstream activation of IKK and degradation of IκBα. Cells were first stimulated with TNFα for 10 min and then with PN (500 μm) or PBS-glucose buffer for 10–60 min. As shown in Fig. 3A, IKK phosphorylation triggered by TNFα was transient, with rapid dephosphorylation when cells were exposed to PBS-glucose buffer after TNFα. The concomitant degradation of IκBα was followed by robust IκBα resynthesis. In marked contrast, stimulation with PN after TNFα prevented IKK dephosphorylation up to 60 min, and this was associated with complete and persistent degradation of IκBα without any signs of IκBα resynthesis. The kinase activity of IKK triggered by TNFα was also profoundly enhanced by PN, as shown in Fig. 3B. This effect was evident as soon as 5 min after the addition of PN, as indicated by a 20-fold increase of IKK activity (Fig. 3, C and D).

FIGURE 3.

Postexposure to oxidants prevents IKK dephosphorylation, leading to prolonged activation of IKK and sustained IkBα degradation. A549 cells were stimulated with 10 ng/ml TNFα for 10 min followed by 500 μm peroxynitrite (PN post-TNFα) or PBS-glucose buffer (PBS post-TNFα) for the indicated times. A, phospho-IKKα/β, IκBα, and IKKα were determined by Western blotting. B and C, IKK activity was determined by kinase assay (KA), and the level of immunoprecipitated IKKα was determined by Western blotting as a loading control. D, IKK activity was quantified by densitometry (*, p < 0.05). Error bars indicate S.E.

PP2A Activity Is Inhibited by Oxidant Stress or OA, Leading to Prolonged IKK Phosphorylation

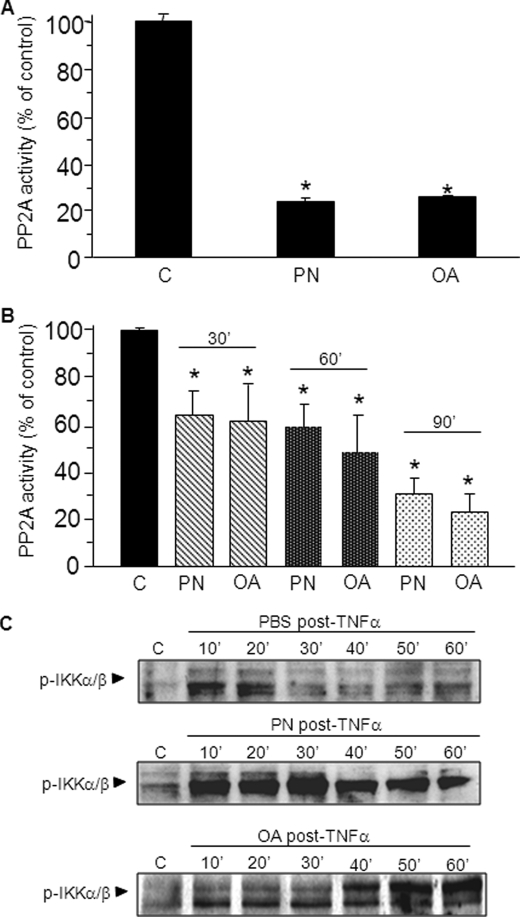

In a first set of experiments, total protein extracts from untreated cells were incubated with PN or OA for 30 min, followed by measurements of PP2A activity. As shown in Fig. 4A, both PN and OA produced a comparably potent inhibition of PP2A activity. In a second set of experiments, cells were first incubated with PN or OA for 30–90 min before measurements of PP2A activity. In such conditions, both PN and OA elicited a time-dependent significant reduction of PP2A activity (Fig. 4B). In a third set of experiments, cells were first activated with TNFα for 5 min and then with PBS-glucose buffer, PN, or OA for 1 h. As indicated in Fig. 4C, the phosphorylation of IKK after TNFα decreased rapidly in cells incubated with PBS-glucose, whereas it was sustained at a high level in cells incubated wit PN or OA.

FIGURE 4.

PP2A activity is inhibited by oxidants or OA, leading to prolonged IKK phosphorylation. A, untreated A549 cells were lysed, and cell lysates were left untreated (control, c) or were treated with 500 μm PN or with 100 nm OA for 30 min. PP2A activity was determined using a Ser/Thr phosphatase assay specific for PP2A. B, A549 cells were unstimulated (control, c) or were stimulated with 500 μm PN or 100 nm OA for 30–90 min. Cells were lysed, and PP2A activity was determined using the PP2A assay (*, p < 0.05). Error bars indicate S.E. C, A549 cells were treated with10 ng/ml TNFα for 10 min followed by PBS-glucose buffer (PBS post-TNFα), PN 500 μm (PN post-TNFα), or 100 nm OA (OA post-TNFα) for the indicated times. Phosphorylated IKKα/β was determined by Western blotting.

Preexposure to Oxidant Stress Conditions Prevents NF-κB Activation by TNFα

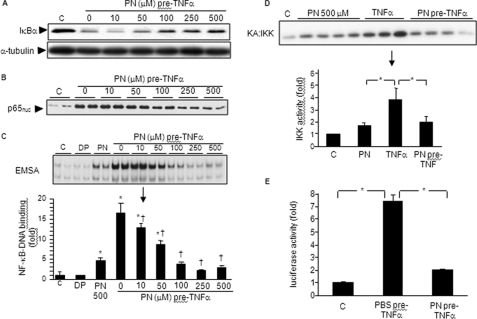

A549 cells were treated with concentrations of PN from 10 to 500 μm for 1 h and then with 10 ng/ml TNFα for 30 min. At concentrations of 50 μm and above, PN produced a concentration-dependent inhibition of NF-κB activation by TNFα, as evidenced by reduced degradation of IκBα (Fig. 5A) and NF-κB p65 nuclear translocation (Fig. 5B). Similarly, PN dose-dependently inhibited NF-κB-DNA binding (Fig. 5C), an effect that was similarly observed when H2O2 was used in place of PN (supplemental Fig. S1). These effects correlated with PN-dependent inhibition of IKK kinase, as indicated in Fig. 5D. IKK activity measured 10 min after TNFα was abrogated following preexposure (1 h) to PN. Furthermore, the induced luciferase expression following TNFα was abrogated when cells were preexposed to PN (1 h, 500 μm, Fig. 5E). Thus, transient exposure of A549 cells to oxidant stress conditions prevents subsequent IKK activation and downstream NF-κB signaling in response to TNFα, which agrees with our previous observations made in unrelated cell lines (13).

FIGURE 5.

Preexposure to oxidants prevents NF-κB activation by TNFα. A and B, A549 cells were left untreated (control, c) or were stimulated with 0–500 μm PN for 1 h followed by 10 ng/ml TNFα for 30 min. IκBα, nuclear p65, and α-tubulin were determined by Western blotting. C, A549 cells were left untreated (control, c) or were treated with decomposed PN (DP), 500 μm PN, or with 0–500 μm PN for 1 h followed by 10 ng/ml TNFα for 30 min. NF-κB-DNA binding activity was determined by EMSA. D, A549 cells were untreated (control, c) or treated with 500 μm PN or TNFα 10 ng/ml for 10 min or with 500 μm PN for 1 h followed by 10 ng/ml TNFα for 10 min. IKK activity was determined by kinase assay (KA), quantified by densitometry (*, p < 0.05). E, A549 cells were unstimulated or stimulated with TNFα for 4 h or with 500 μm PN for 1 h followed by TNFα for 4 h. Luciferase activity was determined in cell lysates at the end of stimulation (*, p < 0.05). Error bars indicate S.E.

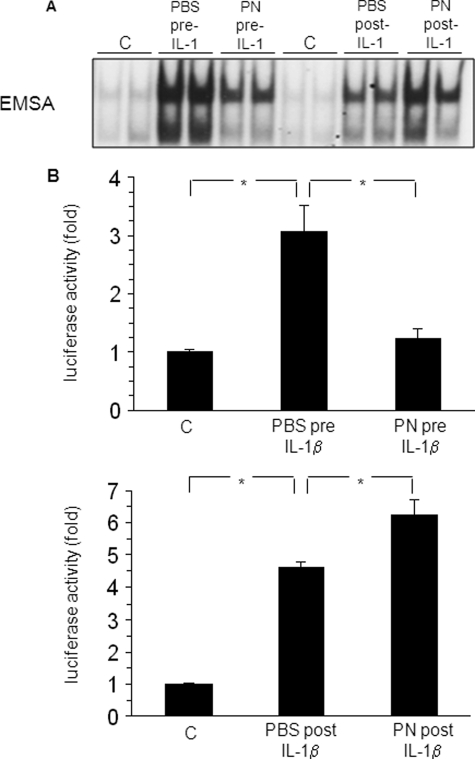

Regulation of NF-κB by Oxidants Is Independent of the Nature of the Immune Stimulus

Cells were activated with IL-1β (30 min) instead of TNFα, and PN or PBS-glucose buffer was added for 1 h, either before or after IL-1β. As shown in Fig. 6A, NF-κB-DNA binding activity was greatly prevented by preexposure to PN, whereas it was reinforced by postexposure to PN. Similar observations were obtained in luciferase reporter experiments (Fig. 6B, upper panel). Preexposure to PN abrogated luciferase activity measured after 4-h stimulation with IL-1β, whereas postexposure enhanced such activity (Fig. 6B, lower panel).

FIGURE 6.

Regulation of NF-κB by oxidants is independent of the nature of the immune stimulus. A, A549 cells were unstimulated (control, c) or were stimulated with 1 ng/ml IL-1β for 30 min in the presence of a pretreatment with PBS buffer (PBS pre-IL-1) or 500 μm PN (PN pre-IL-1) for 1 h, or in the presence of a posttreatment with PBS (PBS post-IL-1) or PN (PN post-IL-1) for 1 h. NF-κB-DNA binding activity was determined by EMSA. B, upper panel, luciferase activity in A549 cells either unstimulated (c) or stimulated with PBS buffer (PBS pre-IL-1) or 500 μm PN (PN pre-IL-1) for 1 h followed by 1 ng/ml IL-1β for 4 h (*, p < 0.05) is shown. Lower panel, luciferase activity in unstimulated A549 cells (c) or in cells treated with 1 ng/ml IL-1β followed by PBS (PBS post-IL-1) or 500 μm PN (PN post-IL-1) for 4 h is shown. *, p < 0.05. Error bars indicate S.E.

DISCUSSION

Defining the mechanisms of NF-κB regulation by oxidant stress is of major importance to understand the role of oxidants and free radicals in the pathophysiology of acute and chronic inflammation. Although it has generally been assumed that oxidants are direct NF-κB activators (for review, see Ref. 2), recent findings have put this paradigm into question, by showing that oxidants rather inhibit NF-κB via oxidative inactivation of IKKβ (for review, see Ref. 9). In the current study, we hypothesized that such contrasted effects might reflect the ability of oxidants to interfere with both positive and negative signals in the NF-κB pathway so that the final outcome (activation versus inhibition) would depend on the balance between these two opposite signals. This issue was addressed by comparing the effects of the oxidants PN or H2O2, given alone or in various combinations with TNFα, in an in vitro cellular model.

Oxidant stress on its own elicited a delayed activation of NF-κB compared with TNFα. This effect was associated with a continuous degradation of IκBα, contrasting with the early (within 30 min) resynthesis of IκBα observed after TNFα, indicating that this essential negative feedback loop was impaired in conditions of oxidant stress. The critical mechanism preventing continuous IκBα degradation is the transient nature of IKK activation, related to a well regulated balance between phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of critical serine residues within the activation loop of IKKα and IKKβ (5). Our finding of transient IKK phosphorylation and activation in response to TNFα is consistent with this concept. In contrast, oxidants triggered persistent IKK phosphorylation associated with long lasting kinase activity, indicating that proper dephosphorylation and inactivation of IKK were prevented in conditions of oxidant stress.

Several recent lines of evidence support a critical role of the serine-threonine phosphatase PP2A in catalyzing IKK dephosphorylation leading to termination of IKK activity. First, PP2A is constitutively recruited to IKKβ (17, 23), where it appears to control dephosphorylation of randomly activated IKK (23). Second, inactivation of PP2A with OA (22), UVB (17, 23), or RNA interference (24) has been associated with persistent IKK activation and NF-κB activation. Therefore, our findings of sustained IKK phosphorylation and permanent IκBα degradation under oxidative conditions pointed to inactivation of PP2A as the most likely underlying mechanism, the more so that PP2A is especially sensitive to inactivation by various oxidant species (25–27).

This hypothesis was further supported by the striking enhancement of TNFα-dependent NF-κB activation observed when oxidants were applied after TNFα. In these conditions, IKK phosphorylation and activity persisted over time, and IκBα resynthesis was completely abrogated. This translated into a significant enhancement of the expression of NF-κB-dependent genes, as shown both by increased luciferase activity and IL-8 secretion when oxidants were applied after TNFα. To evaluate the biological significance of these findings, we determined whether endogenously produced reactive oxygen species would reproduce the effects of exogenously added oxidants. For this purpose, murine fibrosarcoma L929 cells, which produce H2O2 after TNFα (20, 21), were stimulated with TNFα in the presence of the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine. In such conditions, the activation of NF-κB by TNFα was markedly attenuated, indicating that oxidants produced after TNFα in these cells served to amplify the process of NF-κB activation. Overall, these findings support the concept that oxidants promote a prolonged activation of NF-κB following TNFα stimulation via a mechanism involving the prevention of phosphatase-dependent IKK dephosphorylation.

We therefore directly evaluated the sensitivity of PP2A to oxidants in our experimental conditions and found that the latter was inhibited either when the oxidant was applied directly on isolated cellular proteins or when the assay was performed in cellular proteins isolated after stimulation with the oxidant. Importantly, comparable effects were obtained when PN was replaced by the PP2A inhibitor okadaic acid: inhibition of PP2A activity with OA promoted persistent IKK phosphorylation when applied after TNFα.

In addition to the sustained phosphorylation of IKK, we also noticed that TNFα-induced phosphorylation of Ser536 on nuclear p65 was enhanced after exposure to oxidants. This posttranslational modification of p65 has been shown to be essential for proper transcriptional activity of NF-κB (28). Recent findings have indicated that PP2A physically associates with p65 (29) and that inhibition of PP2A with OA (29) or PP2A RNA interference (24) blocked p65-Ser536 dephosphorylation. Thus, the marked increase of Ser536 phosphorylation upon PN treatment is totally consistent with its ability to inhibit PP2A activity.

In striking contrast with the above discussed results, preexposure to oxidant stress markedly inhibited NF-κB activation by TNFα, as indicated by reduced IκBα phosphorylation and degradation, impaired NF-κB DNA binding, and suppressed transcriptional activity, an effect related to the inhibition of TNFα-dependent activation of the kinase IKK (Fig. 4). We did not explore the mechanism underlying such inhibition, as this result confirmed our previous studies performed in unrelated cell lines (13). Furthermore, these findings are consistent with the oxidant-mediated abrogation of IKK activation and downstream signaling in response to cytokines reported in other cell systems in vitro (10–12), an effect related to impaired phosphorylation of serines 177/181 in IKKβ, consecutive to redox modifications (S-glutathionylation) of interjacent cysteine 179 (11, 30).

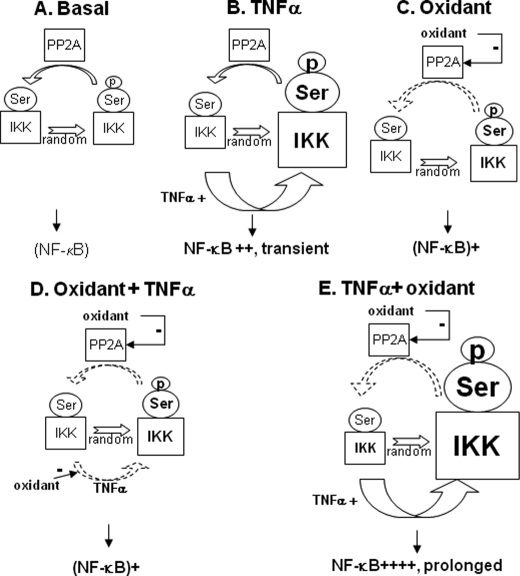

Based on our current findings, we therefore propose a new scheme of interactions among oxidant stress, IKK, and NF-κB, based on oxidative inhibition of both IKK and PP2A, as depicted in Fig. 7. In such a model, oxidant-mediated inactivation of PP2A promotes a slow accumulation of randomly phosphorylated IKK, resulting in low grade, delayed activation of NF-κB. In the presence of an activating stimulus such as TNFα, the influence of oxidants will depend entirely on the initial phosphorylation status of IKK. If not yet phosphorylated at the time of oxidant addition, oxidized IKK will remain unresponsive to the activating stimulus, and NF-κB will not be activated. Alternatively, if already phosphorylated at the time of oxidant addition, IKK will not be dephosphorylated due to impaired PP2A activity, resulting in the amplification and prolongation of NF-κB activation. We believe that this model may explain the controversy surrounding the issue of the redox regulation of NF-κB.

FIGURE 7.

Proposed scheme of interactions among oxidants, IKK, and the NF-κB pathway. A, baseline. Randomly phosphorylated IKK is dephosphorylated by PP2A, preventing NF-κB activation. B, TNFα. IKK phosphorylation is transient, due to PP2A activity, leading to transient NF-κB activation. C, oxidant stress. Inactivation of PP2A promotes a slow accumulation of phosphorylated IKK, resulting in low grade NF-κB activation. D, oxidant stress before TNFα. IKK inhibition by oxidants prevents NF-κB activation. E, oxidant stress after TNFα. IKK phosphorylation by TNFα is not removed due to PP2A inhibition, resulting in prolonged, amplified signal.

Because oxidant stress plays key roles in many chronic inflammatory diseases, antioxidant therapies are frequently considered as potentially suitable agents to treat or prevent such diseases, but large scale studies have failed to confirm such theoretical benefits (31). Our observations help explain these disappointing results by showing that the influence of oxidants on NF-κB signaling is entirely context-dependent. Understanding the complex interactions between oxidant stress and NF-κB should be an essential prerequisite to design efficient antiinflammatory therapies and to avoid unexpected side effects.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by Swiss National Fund for Scientific Research Grants PP00B-68882/1 and 320000-118174/1 (to L. L.). This work was also supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIAAA, National Institutes of Health (to P. P.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. S1.

- NF-κB

- nuclear factor κB

- IKK

- IκB kinase

- PN

- peroxynitrite

- TNFα

- tumor necrosis factor α

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- IL

- interleukin

- OA

- okadaic acid

- EMSA

- electromobility shift assay

- PP2A

- protein phosphatase 2A.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pacher P., Beckman J. S., Liaudet L. (2007) Physiol. Rev. 87, 315–424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gloire G., Legrand-Poels S., Piette J. (2006) Biochem. Pharmacol. 72, 1493–1505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghosh S., Hayden M. S. (2008) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 837–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karin M. (2008) Cell Res. 18, 334–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayden M. S., Ghosh S. (2008) Cell 132, 344–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schreck R., Rieber P., Baeuerle P. A. (1991) EMBO J. 10, 2247–2258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamata H., Manabe T., Oka S., Kamata K., Hirata H. (2002) FEBS Lett. 519, 231–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Imbert V., Rupec R. A., Livolsi A., Pahl H. L., Traenckner E. B., Mueller-Dieckmann C., Farahifar D., Rossi B., Auberger P., Baeuerle P. A., Peyron J. F. (1996) Cell 86, 787–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pantano C., Reynaert N. L., van der Vliet A., Janssen-Heininger Y. M. (2006) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 8, 1791–1806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Byun M. S., Jeon K. I., Choi J. W., Shim J. Y., Jue D. M. (2002) Exp. Mol. Med. 34, 332–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korn S. H., Wouters E. F., Vos N., Janssen-Heininger Y. M. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 35693–35700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Panopoulos A., Harraz M., Engelhardt J. F., Zandi E. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 2912–2923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levrand S., Pesse B., Feihl F., Waeber B., Pacher P., Rolli J., Schaller M. D., Liaudet L. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 34878–34887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rossi A., Kapahi P., Natoli G., Takahashi T., Chen Y., Karin M., Santoro M. G. (2000) Nature 403, 103–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kapahi P., Takahashi T., Natoli G., Adams S. R., Chen Y., Tsien R. Y., Karin M. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 36062–36066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ji C., Kozak K. R., Marnett L. J. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 18223–18228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barisic S., Strozyk E., Peters N., Walczak H., Kulms D. (2008) Cell Death Differ. 15, 1681–1690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uppu R. M., Pryor W. A. (1996) Anal. Biochem. 236, 242–249 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levrand S., Vannay-Bouchiche C., Pesse B., Pacher P., Feihl F., Waeber B., Liaudet L. (2006) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 41, 886–895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sánchez-Alcázar J. A., Schneider E., Hernández-Muñoz I., Ruiz-Cabello J., Siles-Rivas E., de la Torre P., Bornstein B., Brea G., Arenas J., Garesse R., Solís-Herruzo J. A., Knox A. J., Navas P. (2003) Biochem. J. 370, 609–619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xue X., Piao J. H., Nakajima A., Sakon-Komazawa S., Kojima Y., Mori K., Yagita H., Okumura K., Harding H., Nakano H. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 33917–33925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DiDonato J. A., Hayakawa M., Rothwarf D. M., Zandi E., Karin M. (1997) Nature 388, 548–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Witt J., Barisic S., Schumann E., Allgöwer F., Sawodny O., Sauter T., Kulms D. (2009) BMC Syst. Biol. 3, 71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li S., Wang L., Berman M. A., Zhang Y., Dorf M. E. (2006) Mol. Cell 24, 497–509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen L., Liu L., Huang S. (2008) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 45, 1035–1044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim H. S., Song M. C., Kwak I. H., Park T. J., Lim I. K. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 37497–37510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rao R. K., Clayton L. W. (2002) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 293, 610–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sakurai H., Suzuki S., Kawasaki N., Nakano H., Okazaki T., Chino A., Doi T., Saiki I. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 36916–36923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang J., Fan G. H., Wadzinski B. E., Sakurai H., Richmond A. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 47828–47833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reynaert N. L., van der Vliet A., Guala A. S., McGovern T., Hristova M., Pantano C., Heintz N. H., Heim J., Ho Y. S., Matthews D. E., Wouters E. F., Janssen-Heininger Y. M. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 13086–13091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bjelakovic G., Gluud C. (2007) J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 99, 742–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.