Abstract

Heme is a redox-reactive molecule with vital and complex roles in bacterial metabolism, survival, and virulence. However, few intracellular heme partners were identified to date and are not well conserved in bacteria. The opportunistic pathogen Streptococcus agalactiae (group B Streptococcus) is a heme auxotroph, which acquires exogenous heme to activate an aerobic respiratory chain. We identified the alkyl hydroperoxide reductase AhpC, a member of the highly conserved thiol-dependent 2-Cys peroxiredoxins, as a heme-binding protein. AhpC binds hemin with a Kd of 0.5 μm and a 1:1 stoichiometry. Mutagenesis of cysteines revealed that hemin binding is dissociable from catalytic activity and multimerization. AhpC reductase activity was unchanged upon interaction with heme in vitro and in vivo. A group B Streptococcus ahpC mutant displayed attenuation of two heme-dependent functions, respiration and activity of a heterologous catalase, suggesting a role for AhpC in heme intracellular fate. In support of this hypothesis, AhpC-bound hemin was protected from chemical degradation in vitro. Our results reveal for the first time a role for AhpC as a heme-binding protein.

Keywords: Cell/Trafficking, Enzymes/Multifunctional, Enzymes/Reductase, Metabolism/Heme, Organisms/Bacteria, Oxygen/Anti-oxidant, Protein/Heme, Protein/Intracellular Trafficking

Introduction

For most living organisms, heme is an essential cofactor of enzymes such as cytochromes, catalases, and peroxidases (1). The importance of heme resides in the unique properties of its iron center, including the capacities to undergo electron transfer, perform acid-base reactions, and interact with various coordinating ligands (2). Recent evidence has emphasized another role for heme, as a signaling molecule that regulates the function of key proteins implicated in diverse cellular processes (3, 4). In bacterial pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus, heme is a preferred iron source (5, 6), and specific mechanisms are used to capture and transport heme into the cytoplasm (5, 7). Once internalized, heme is incorporated into bacterial proteins or degraded to release iron for incorporation into iron-sulfur proteins or for endogenous heme synthesis (8). In Escherichia coli and other heme-synthesizing bacteria, heme b is further processed to heme d by the activity of the heme hydroperoxidase II (the catalase KatE) (9); both heme forms are required for activity of the cytochrome bd oxidase (10–12). Heme toxicity is due to redox reactions involving heme iron and oxygen, which generate reactive oxygen species (ROS)2 that induce membrane peroxidation and damage to proteins and DNA (13). ROS such as H2O2 or hydroperoxides can also initiate nonenzymatic modification and degradation of heme (13, 14). In view of these data and the low solubility of free heme, it is probable that internalized heme does not exist as a free molecule in the cytoplasm but as a complex with heme-binding proteins, which would reduce its contact with the cellular environment and facilitate its intracellular trafficking.

Few intracellular heme-binding proteins have been described in prokaryotes. In E. coli, CcmE is a heme chaperone that binds heme transiently in the periplasm and delivers it to newly synthesized and exported c-type cytochrome (15). Recently, three homologous cytoplasmic heme-binding proteins, Pseudomonas aeruginosa PhuS (16, 17), Shigella dysenteriae ShuS (18), and Yersinia enterocolitica HemS (19, 20), were reported to participate in intracellular heme storage and facilitate heme transfer from the uptake machinery to heme-binding proteins such as heme-oxygenase.

The opportunistic pathogen Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus (GBS)) is an asymptomatic inhabitant of the intestine and vagina but a leading cause of invasive infection in newborns and immunocompromised adults (21). GBS does not synthesize heme and is catalase-negative. However, GBS uses exogenous heme and menaquinone in an aerobic environment to activate a GBS membrane respiratory chain involving a cytochrome bd oxidase, needed for full virulence. The shift from fermentation to respiration metabolism results in increased biomass and improved survival (11). Although GBS can assimilate free heme or hemoglobin-bound heme (11, 22), little is known about its molecular mechanisms for heme acquisition and utilization. Our goal is to identify GBS proteins responsible for heme homeostasis. To this purpose, we used heme affinity chromatography to enrich for heme-binding proteins from bacterial lysates. Several potential heme-binding proteins were identified by MALDI-TOF. Here, we present the characterization of one of these proteins, the ubiquitous alkyl hydroxyperoxide reductase (AhpC), and show that it is a heme-binding protein.

The conserved alkyl hydroxyperoxide reductase AhpC belongs to the family of peroxiredoxins (Prx) (23). AhpC is a 2-Cys peroxiredoxin that, when coupled with a disulfide reductase as an electron donor, acts on hydrogen peroxide, peroxynitrite, and organic hydroperoxides to generate their corresponding alcohols (24). Prxs are also implicated in regulatory functions, as mainly reported in eukaryotes, such as transcription, apoptosis, and cellular signaling (25–27). In Helicobacter pylori, AhpC was shown to oligomerize and acquire protein chaperone activity in oxidative stress conditions (28).

Using genetic, biochemical, and spectrophotometric approaches, we show for the first time that a bacterial AhpC protein has heme-binding and heme protection capacities. Because AhpC belongs to a family of highly conserved peroxidases, our findings could have significance in other prokaryotes and provide an additional role for this already multifunctional protein.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial Strains

Characteristics of relevant strains and plasmids are described in supplemental Table S1. GBS strain NEM316, whose genome sequence is known, belongs to the capsular serotype III strain (GBS) and was isolated from a case of fatal septicemia (29). The GBS ahpC insertion mutant was constructed by inserting, in the same transcriptional orientation as ahpC, the promoterless and terminatorless kanamycin resistance cassette aphA-3 (30) within DNA segments encompassing the 5′ and 3′ ends of ahpC and ahpF, respectively, inactivating both genes (supplemental Fig. S1A). Three amplicons were generated using oligonucleotide pairs O1-O2, O3-O4, O5-O6 and then ligated after digestion with the appropriate enzymes (see supplemental Table S2). The resulting EcoRI-PstI fragment was cloned into pG+host5 (31), and the recombinant vector was introduced by electroporation into GBS NEM316. The double crossover events leading to the expected gene replacements were screened and obtained as described previously (32). Structure of the chromosomal insertion was verified using PCR analysis (supplemental Fig. S1, A and B) and DNA sequencing (data not shown). Note that for the clarity of the text, the ahpCF mutant described here was named ahpC throughout this study.

Bacterial Growth Conditions and Media

GBS was grown at 37 °C in rich M17 liquid broth (Difco) supplemented with 1% glucose, after inoculation by precultures grown in M17 with 0.2% glucose. GBS respiration metabolism was activated by supplementing medium with 1 μm hemin (from a stock solution of 10 mm hemin chloride dissolved in 50 mm NaOH; Fluka) and 10 μm vitamin K2 (Sigma) and growing in a rotary shaker (200 rpm) as described previously (11, 33). E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium. When needed, antibiotics were used as follows: 100 μg/ml ampicillin and 50 μg/ml kanamycin for E. coli; 5 μg/ml erythromycin and 5 μg/ml chloramphenicol for GBS.

Hemin Affinity Chromatography

Bacteria were grown overnight without aeration. Pelleted bacteria were resuspended in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 m NaCl, and 0.5% Triton X-100 and lysed with glass beads (Fastprep, MP Biomedicals). Cell debris and glass beads were removed by centrifugation at 18,000 × g for 10 min. The lysate was mixed with hemin-conjugated agarose (Sigma) for 2 h at 4 °C on a spinning wheel. Agarose was washed three times by centrifugation with 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 m NaCl, 0.25% Triton X-100, and 5 mm EDTA. All steps were carried out at 4 °C. Following the last washing, agarose beads were resuspended in Laemmli sample buffer (34), incubated at 90 °C for 5 min, and centrifuged 5 min at 18,000 × g. Supernatants were processed for SDS-PAGE.

Expression and Purification of His-AhpC

The GBS AhpC (GBS1874) open reading frame was amplified from NEM316 using (O7, O8) oligonucleotide primers (supplemental Table S2) and cloned into the E. coli expression plasmid Champion pET100 directional TOPO (pET100/D-TOPO) vector (Invitrogen), giving rise to a hexahistidine N-terminal fusion protein expression vector, pHis-AhpC. Mutant His-AhpCC47A,C165A was obtained by overlapping PCR mutagenesis (35), using the overlapping O9, O10 and O11, O12 primers for introducing C47A and C165A point mutations, respectively, in the AhpC sequence. The product was cloned into pET100/D-TOPO vector (supplemental Table S1). All plasmids were verified by sequencing. E. coli BL21 (DE3) transformed with pHis-AhpC was grown to A600 = 0.6, and expression was induced with 1 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside for 2 h at 37 °C. Cells were pelleted at 3,500 × g for 10 min and then resuspended in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 300 mm NaCl, containing 20 mm imidazole (binding buffer), and disrupted with glass beads (Fastprep, MP Biomedicals). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 18,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. His-tagged proteins were purified by nickel affinity chromatography using His-Select affinity gel (Sigma) following the manufacturer's recommendations. Briefly, the soluble fraction was mixed with resin and incubated on a spinning wheel at 4 °C for 1 h. The resin was then centrifuged and washed three times with binding buffer. Purified proteins were eluted with 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 300 mm NaCl, containing 150 mm imidazole, dialyzed against 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, and finally stored at −80 °C. Protein concentrations were determined with the Lowry assay method (Bio-Rad).

Construction of the HA-AhpC and AhpCF Vectors

A recombinant AhpC with an N-terminal HA tag (MYPYDVPDYA) extension (HA-AhpC) was generated by successive PCRs (35). Briefly, two rounds of PCR were performed to obtain overlapping DNA fragments encoding the HA-AhpC fusion. First, the AhpC coding sequence and promoter regions were amplified with oligonucleotide pairs O8-O13 and O15-O16, respectively, using GBS genomic DNA as template. Both O13 and O15 include half of the HA peptide sequence (supplemental Table S2, see italics). These fragments were then used as templates for a second round of PCR to expand the HA sequence using O8-O14 and O16-O17 oligonucleotide pairs. The resulting overlapping PCR products were annealed and amplified with oligonucleotide pairs O12-O15 (supplemental Table S2). The pHA-AhpC plasmid (supplemental Table S1) was obtained by cloning the final PCR product into pCR-BLUNT vector (Invitrogen). The entire ahpCF operon was also amplified by PCR with the oligonucleotide primers O16-O18 (supplemental Table S2) and cloned into the pCR-BLUNT vector (Invitrogen) giving rise to the pAhpCF vector (supplemental Table S1).

Expression and Purification of MBP-AhpC

The GBS AhpC (GBS1874) open reading frame was amplified from NEM316 genomic DNA using O21 and O22 oligonucleotide primers (supplemental Table S2), including the EcoRI and XbaI restriction sites, respectively. The PCR products were cloned into pMAL-c4X (New England Biolabs) using EcoRI and XbaI restriction sites generating a plasmid encoding the fusion of the maltose-binding protein (MBP) at the N terminus of AhpC (pMAL-AhpC) (supplemental Table S1). The plasmid was verified by sequencing and transformed into the E. coli TOP10 strain (supplemental Table S1). Purification of MBP-AhpC was performed on bacteria lysed as described for His-AhpC isolation (see above). MBP-AhpC protein was purified on amylose resin in 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 200 mm NaCl, and 1 mm EDTA (binding buffer) according to the manufacturer's recommendations (New England Biolabs). Elution of the MBP-AhpC protein was performed with 10 mm maltose in binding buffer.

In Gel Detection of Hemin

Hemin binding to AhpC was identified in SDS-PAGE, as described previously (36, 37). Briefly, 50 μg of purified His-tagged protein was incubated for 30 min at room temperature with a 2-fold molar excess of hemin in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, with Laemmli sample buffer without dithiothreitol and without heating. Samples were separated by SDS-PAGE. Hemin peroxidase activity was detected by staining the gel in a tetramethylbenzidine- and H2O2-containing solution (Sigma).

Purification of AhpC-Hemin Complex

His-AhpC-Hemin complex was prepared by incubating 50 μg of purified His-AhpC with a 2-fold excess of hemin in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5. After incubation at room temperature for 30 min, free hemin was removed by chromatography on a Sephadex G-15 gel filtration column (Sigma). Hemin content of the complex was determined by the pyridine hemochrome assay as described previously (38).

Absorbance Spectroscopy of the AhpC-Hemin Complex

Hemin binding affinities of His-AhpC and variants were determined by adding 0.5 to 1-μl increments of a 200 μm hemin solution to cuvettes containing test samples, in 100 μl of 10 μm His-AhpC in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, or reference sample without protein. Spectra were measured from 350 to 700 nm in a UV-visible spectrophotometer Libra S22 (Biochrom). Absorbance at 414 nm was plotted against hemin concentration, and data were fitted to a one-binding site model, which accounts for the protein concentration to determine the dissociation constant (39, 40) as shown in Equation 1,

|

A414 is the absorbance at 414 nm; CH is the concentration of heme added in the sample and reference cuvettes; Bmax is the absorbance of the maximal binding; and ϵ414 is the extinction coefficient of AhpC bound heme. The extinction coefficient of bound heme was calculated (ϵ414 = 83 mm−1·cm−1) from the absorbance at 414 nm of 7.0 μm of the purified complex according to the following equation: A414 = ϵ414·l·c (where l is the path length (1 cm) and c is the concentration of the protein complex). Curves were fitted to a one-binding site model with the equation described above using the nonlinear regression function of GraphPad Prism 4 software.

Resonance Raman Spectroscopy

AhpC-hemin complex in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, was excited with a 406.7-nm line of an Innova Kr+ laser (Coherent, Palo Alto). Spectra were recorded at 20 °C using a U1000 spectrometer (Jobin Yvon, France) equipped with an ultrasensitive back-thinned CCD detector. Radiant powers of 10 milliwatt were used to avoid photoreduction of the oxidized sample.

Peroxide Reductase Activity Assay

The peroxide reductase activity of recombinant His-AhpC free or in complex with hemin was measured by following the decrease at 340 nm within 10 min at 25 °C due to NADPH oxidation in a UV-visible spectrophotometer Libra S22 (Biochrom). Each assay was performed using 10 μm His-AhpC or 10 μm His-AhpC-hemin complex in 50 mm potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, 0.1 m ammonium sulfate, 0.5 mm EDTA, containing 5 μm thioredoxin (Sigma), 0.5 μm thioredoxin reductase (Sigma), and 150 μm NADPH (ϵ340 = 6.22 mm−1·cm−1). The reaction was initiated by the addition of 5 mm H2O2 (28). Background enzymatic activity was measured in the same conditions without thioredoxin reductase. Values are expressed in units (μmol of NADPH·min−1).

Immunoblotting

Immunoblotting was performed on bacterial lysates of strains transformed with the indicated expression vectors as reported previously (41).

Measurement of Oxygen Consumption

Oxygen consumption was followed with a Clark-type oxygen electrode (Liquid-Phase oxygen electrode unit DW1, Hansatech Instruments). The electrode was calibrated as recommended by the manufacturer, using air-saturated 50 mm potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.3, at 37 °C, assuming an oxygen concentration of 217 μm. Sodium dithionite was added to zero the electrode. S. agalactiae WT and ahpC late exponential phase cultures, prepared in aerobic fermentation or respiration conditions, were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline at 4 °C and resuspended in the same buffer at A600 = 1.0. One-ml volume of the bacterial suspension was transferred to a sealed cuvette equipped with the oxygen electrode. The bacterial suspension was then air-saturated by stirring for about 6 min at 37 °C, and after capping of the chamber, the maximum oxygen consumption rate was measured following the addition of 10 mm glucose, which was injected using a Hamilton microliter syringe through a capillary hole.

Hemin Intracellular Status

Hemin intracellular accumulation was assessed in vivo by following activity of the Enterococcus faecalis hemin-catalase (KatA) cloned under control of the kanamycin resistance gene (aphA-3) constitutive promoter PaphA-3 (pLUMB5, supplemental Table S1) (42). Diluted cultures transformed with the pLUMB5 plasmid were grown overnight under static conditions in M17 containing 1% glucose and supplemented or not with hemin. KatA expression in saturated cultures was followed on immunoblots with a polyclonal anti-KatA antibody (42). Catalase activity of pLUMB5 transformed bacteria was determined on whole cells incubated with 50 μm H2O2 with the spectrophotometric FOX1 method based on ferrous oxidation in xylenol orange as described previously (43). Absorption was measured at 560 nm. H2O2 concentrations in samples were calculated from a calibration curve with known concentrations of H2O2.

H2O2-mediated Hemin Degradation

Comparative intensities of the Soret band peaks were determined for hemin complexed or not with 20 μm AhpC or bovine serum albumin (BSA, fatty acid-free, Sigma) in the presence of H2O2. The Soret band peak absorption is 385 nm for free hemin and 414 nm for AhpC or BSA-bound hemin. Absorption values were measured as a function of time following addition of 800 μm H2O2. The data were normalized by subtracting the zero time point value to subsequent time points.

RESULTS

Identification of the Alkyl Hydroxyperoxidase (AhpC) by Hemin Affinity Chromatography

We used hemin-agarose affinity chromatography to identify hemin-binding proteins in Streptococcaceae. We initially identified proteins from Lactococcus lactis lysates that bound to hemin-conjugated agarose. Among the proteins identified by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry, a protein band migrating at around 20 kDa was identified as AhpC (data not shown). AhpC is a member of a highly conserved protein family and shares 71% identity with the NEM316 protein encoded by gbs1874 (supplemental Fig. S1C). In GBS and numerous bacteria, ahpC is clustered with ahpF (see supplemental Fig. S1A), the gene coding for the alkyl hydroperoxide reductase (AhpF) subunit, which functions as an electron donor to regenerate AhpC (44). We selected the GBS AhpC protein for study for the following reasons. (i) It shows 38% amino acid sequence identity with HBP23, a rat liver protein recently identified on the basis of its affinity for hemin but whose function remains unknown (supplemental Fig. S1C) (45, 46). (ii) AhpC plays a major role in oxidative stress resistance especially against organic peroxides, which could have relevance for infection. (iii) The AhpC amino acid sequence includes two cysteine-proline (CP) motifs belonging to the catalytic and resolving domains of the enzyme, which are potentially involved in binding hemin as described for several proteins (supplemental Fig. S1C) (for review see Ref. 3). Recent work also emphasizes the multifunctional aspects of this enzyme, as it is described as a protein chaperone in H. pylori and in yeast (25, 28) and as a regulator of cell signaling pathways in eukaryotes (46).

AhpC Binds Hemin in Vitro

The AhpC open reading frame was expressed as an N-terminal His-tagged protein and purified by affinity chromatography on nickel nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose (supplemental Fig. S2A), yielding a distinct protein band of around 23 kDa that binds to hemin-agarose (Fig. 1A, 1st lane). When 50 μm His-AhpC was preincubated with hemin, resin binding was inhibited as a function of the hemin concentration (Fig. 1A), suggesting that AhpC interaction with hemin was specific and noncovalent. In line with this result, the His-AhpC-hemin complex could be reconstituted in vitro and was characterized by UV-visible spectroscopy. The spectrum of the complex at pH 7.4 (Fig. 1B) revealed a Soret band at 414 nm and β/α bands at 535 and 566 nm, respectively, consistent with ferric hexacoordinate low spin binding through the hemin iron center (38). Reduction of the complex with dithionite (47) resulted in a shift of the Soret band from 414 to 426 nm although oxidation with ammonium persulfate did not, suggesting that AhpC is bound to ferric hemin in our experimental conditions (supplemental Fig. S2B). The nature of the interaction was further investigated by resonance Raman spectroscopy. Fig. 1C displays the high frequency region (1300–1700 cm−1) of the resonance Raman spectra of the AhpC-heme complex, performed at room temperature and pH 7.4 with a laser excitation at 406.7 nm. The spectra of this region consist of well known marker bands that are sensitive to the oxidation, spin, and coordination of the heme iron. The oxidation marker band ν4 was observed at 1375 cm−1 and is typical of ferric heme. The spin and coordination markers band ν3 (at 1503 cm−1) and ν2 (at 1589 cm−1) are characteristic of 6-coordinate (6c) low spin hemes (48). However, the ν3 and ν2 bands display an asymmetrical shape, which suggests the presence of weak bands at 1490 and 1575 cm−1 and thus the existence of a small population of oxidized high spin hemes in the sample. The heterogeneity of the heme population is also reflected by the higher frequency spectral region (>1600 cm−1). This region contains contributions of the vinyl stretching modes of b-type hemes (at 1620 cm−1) and the ν10 component (which is sensitive both to the spin state of the heme and to its conformation (49)). ν10 shows at least two contributions at 1632 and 1638 cm−1 (frequencies obtained by deconvolution but may vary according to the number of components used in this procedure). This suggests that in addition to heterogeneity in spin state, the oxidized hemes display heterogeneity in conformation in their binding sites. The nature of this heterogeneity, which requires the measurement of the whole resonance Raman spectra with different excitations, will be analyzed in further studies.

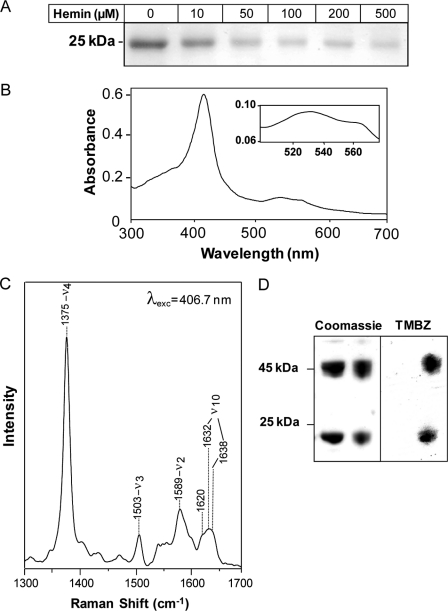

FIGURE 1.

AhpC is a hemin-binding protein. A, purified His-AhpC binds to hemin-conjugated agarose. His-AhpC (50 μm) was incubated with the indicated amount of hemin in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, containing 50 mm NaCl for 15 min prior to hemin-agarose addition. After washings, bound protein was eluted from the resin with 2× Laemmli sample buffer and processed for SDS-PAGE, followed by Coomassie Blue staining. Binding to hemin-agarose was inhibited by increasing hemin concentrations. B, UV-visible absorption spectrum of the AhpC-hemin complex. Purified holo-AhpC exhibits a Soret band at 414 nm and β and α bands at 535 and 566 nm, respectively (inset). C, resonance Raman spectrum of AhpC-hemin. High frequency region of the resonance spectrum of the complex at pH 7.4 was obtained with 406.7 nm laser excitation. The 1632 and 1638 cm−1 bands comprising ν10 were obtained by curve fitting. D, AhpC and hemin co-migrate on SDS-PAGE. His-AhpC alone (left panel, left lane) or in complex with hemin (left panel, right lane) were separated by SDS-PAGE without dithiothreitol as a mixture of disulfide-linked dimers (46 kDa) and monomers (23 kDa) (left panel, upper and lower bands, respectively). The gel was stained for hemin-associated peroxidase activity with tetramethylbenzidine (TMBZ, right panel), showing that AhpC monomers and dimers both interact with hemin. No tetramethylbenzidine staining was observed with AhpC alone (right panel, left lane).

The AhpC-hemin interaction was also studied by SDS-PAGE, using tetramethylbenzidine to reveal the presence of hemin (Fig. 1D). In mild denaturing conditions (0.5% SDS in the sample buffer and no heating), AhpC migrated as a mixture of monomers (23 kDa) and disulfide-linked dimers (47 kDa) (Fig. 1D, left panel). In these conditions, heme-associated peroxidase activity was observed with both monomeric and dimeric AhpC (Fig. 1D, right panel). Because binding is noncovalent (see Fig. 1 and below), these findings point also to a tight interaction, i.e. resistant to denaturation, between AhpC and hemin as reported earlier for other heme-binding proteins (47, 50, 51). No peroxidase activity was associated with the apoprotein (Fig. 1D, left panel, 1st and 2nd lanes), which is expected as AhpC requires an electron donor such as AhpF to be catalytically active (Fig. 1D, right panel) (52). Hemin binding to His-AhpC did not affect the ratio of dimer to monomer protein.

Characteristics of the AhpC-Hemin Complex

Utilizing the difference of the Soret band peak of free and His-AhpC-bound hemin, spectrophotometric titration of AhpC with increasing amounts of hemin was carried out at 414 nm (Fig. 2A and supplemental Fig. S2C). The dissociation constant Kd value of the AhpC-hemin complex was 0.52 ± 0.08 μm (mean ± S.D.; n = 6). His tag removal with enterokinase did not change the Kd value (data not shown), consistent with previous data showing that the His peptide has no affinity for hemin (53). The saturation point, as determined by titration, was around 10 μm hemin, indicating that AhpC binds one molecule of hemin per monomer (Fig. 2A). This conclusion was further demonstrated using the pyridine hemochrome assay to assess heme content. Results showed that 5 μm AhpC complex bound 5.5 ± 0.2 μm (mean ± S.D.; n = 3) (supplemental Fig. S2D).

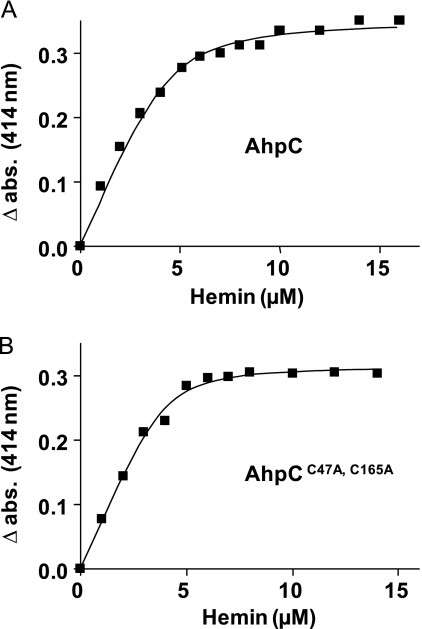

FIGURE 2.

Titration curves of AhpC WT and cysteine mutated with hemin. WT (A) and cysteine-mutated (B) AhpC (5 μm) were titrated with increasing increments of hemin. A414 was plotted against hemin concentration. Curves are representative of three independent experiments and were fitted using the nonlinear regression function of GraphPad Prism 4 software with the equation defined under “Experimental Procedures.” abs, absorbance.

The GBS AhpC protein has catalytic sites centered on positions Cys47 and Cys165 (supplemental Fig. S1C). To investigate the role of the cysteines in hemin affinity, we generated a His-AhpC derivative in which the two Cys residues were modified (supplemental Fig. S1C). The hemin titration curve of the C47A,C165A double AhpC mutant was identical to that of the WT (Fig. 2B). Moreover, the Kd value of mutated AhpC-hemin was 0.23 ± 0.04 μm (mean ± S.D.; n = 6) compared with 0.52 ± 0.08 μm (mean ± S.D.; n = 6) for native AhpC, suggesting that the hemin-binding domain is distinct from the catalytic/dimerization domains. This result is in accordance with the observation that hemin binds AhpC monomers as well as dimers (Fig. 1D). These results also suggest that hemin binding is distinct from the enzymatic activity of AhpC.

AhpC Binds Hemin in Vivo

An expression vector comprising the GBS AhpC open reading frame tagged at its N terminus with the hemagglutinin (HA) influenza peptide and transcribed via its native promoter was used to study AhpC in vivo. Western blot analysis with HA antibody showed that HA-AhpC was expressed in E. coli (Fig. 3A). When whole cell lysates were incubated with hemin-agarose, HA-AhpC was eluted from the resin-bound fraction, confirming AhpC to be a hemin-binding protein (Fig. 3A). To investigate whether AhpC binds hemin in vivo, we stimulated E. coli heme biosynthesis by adding δ-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) to strains overexpressing N-terminal MBP-tagged AhpC open reading frame in the presence of isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside (54, 55). The choice of the MBP-AhpC fusion was made to avoid treatments used for purification of the HA-AhpC or His-AhpC fusions, which could interfere with heme binding (MBP fusions are eluted with maltose). When induced in the presence of ALA, purified MBP-AhpC on amylose resin exhibited a light red color suggesting that AhpC could be copurified with heme (Fig. 3B and supplemental Fig. S3). Confirming this observation, a UV-visible spectra of an equivalent amount of purified MBP-AhpC originating from E. coli grown in the presence of ALA showed a Soret band at 414 nm (Fig. 3C) indicating that AhpC may complex with hemin in vivo.

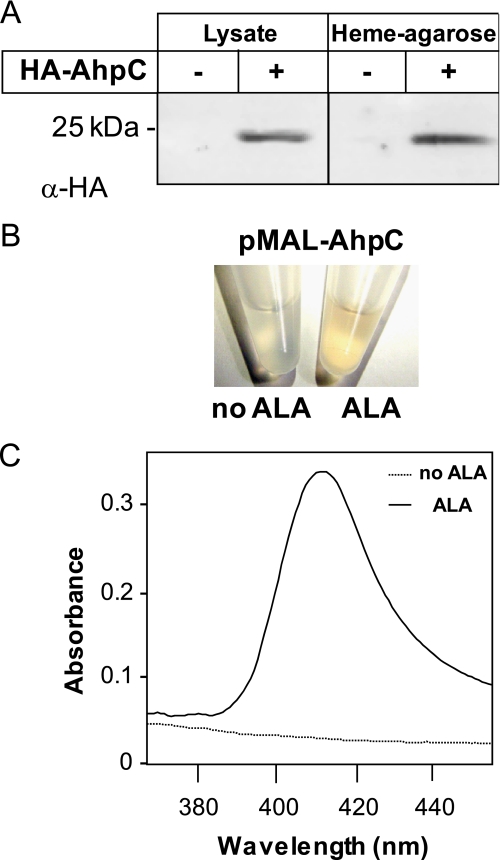

FIGURE 3.

AhpC binds hemin in vivo. A, E. coli lysates expressing HA-AhpC were incubated with hemin-agarose. HA-AhpC was eluted from hemin-conjugated resin as seen with an anti-HA antibody. B, purified MBP-AhpC from ALA-treated E. coli exhibits a red color (as also observed for HA-AhpC under similar conditions; data not shown). E. coli strains carrying the pMAL-AhpC expression vector were grown to A600 = 0.3 at 37 °C, cooled down to room temperature, and further grown at room temperature for 16 h in the presence of 0.25 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside and 1 mm ALA, a heme precursor that stimulates its synthesis. Cells were lysed, and the MBP-AhpC protein was purified on amylose resin (see “Experimental Procedures”). C, visible spectra of MBP-AhpC purified from E. coli treated with ALA or not as in B. Equivalent concentrations (60 μm) of MBP-AhpC as shown in B were analyzed by UV-visible spectrophotometry. Only the spectra corresponding to the protein isolated from ALA-treated cells exhibited a Soret band, further suggesting that heterologous overexpression of MBP-AhpC captured a fraction of overproduced hemin. The MBP tag has no affinity for hemin (data not shown).

Hemin Does Not Modify AhpC Alkyl Hydroxyperoxidase Activity

Like numerous peroxidases, AhpC hydroxyperoxidase activity does not require heme as a cofactor (56). As hemin did not bind AhpC through its catalytic sites (Fig. 2), we considered it unlikely that hemin interferes directly with its enzymatic activity. To validate this supposition, AhpC reductase activity was measured in vitro in hemin-bound and hemin-free forms using the thioredoxin-regenerating system (28). AhpC (10 μm) in complex with hemin had a similar reductase activity to that of the apoprotein (8.6 ± 1.6 and 9.5 ± 2.7 milliunits (mean ± S.D.; n = 3)), indicating that hemin had no effect on AhpC enzymatic properties. This does not rule out that, under in vivo conditions, the hemin cofactor is in a different redox/ligation state that could have an impact on AhpC activity. In vivo, the GBS ahpC mutant exhibited greater sensitivity than the WT strain to the alkylperoxide cumene hydroperoxide on plate tests (supplemental Table S3). Addition of hemin to cultures did not modify the size of the inhibition zone, suggesting that hemin does not affect enzyme activity (supplemental Table S3). We also used an in vivo approach in E. coli to estimate peroxidase activity of AhpC in a complex with hemin or not. The GBS ahpCF operon (pAhpCF) was first established in an E. coli ahpC mutant. Functionality of the GBS enzyme in E. coli was confirmed, as the transformed strain displayed clearly greater resistance to cumene hydroperoxide than the ahpC mutant and was even slightly more resistant than the WT E. coli parental strain (supplemental Table S4, 1st column). When the same bacteria were grown with ALA, the inhibition rings induced by cumene hydroperoxide were unchanged (supplemental Table S4, 2nd column), and cellular AhpC levels were comparable (as determined by Western blot; data not shown). Taken together, these data suggest that AhpC reductase activity is not hemin-dependent.

Respiration Metabolism Is Attenuated in an ahpC GBS Mutant

Increasing concentrations of hemin added to culture medium had similar toxicity in aerobic fermentation cultures of WT and ahpC GBS, thus making it unlikely that AhpC has a central role in limiting hemin toxicity (supplemental Fig. S4A). We investigated an alternative possibility that AhpC could participate in hemin intracellular availability. To date, no enzymatic function, other than the cytochrome bd oxidase, is known to use hemin in GBS (11). We first examined the efficiency of respiration metabolism in WT and ahpC strains as an indicator of intracellular hemin availability, because GBS respiration activity in late growth is contingent upon addition of hemin and a menaquinone (vitamin K2) (supplemental Fig. S4B) (11). Strains grown in hemin but without vitamin K2 (nonrespiratory condition) were used as controls. Respiration metabolism of WT GBS stimulated biomass by 1.8-fold compared with nonrespiring aerobic cultures, as reported (Fig. 4A and supplemental Fig. S4B) (11). In contrast, the ahpC mutant showed only a 1.4-fold increase in biomass in respiration conditions. To confirm that this difference was due to a respiration defect of the mutant, we compared the rate of oxygen consumption in WT and ahpC cells (11). Both strains exhibited similar low rates of oxygen consumption in nonrespiration conditions (Fig. 4B, fermentation), probably due to cytoplasmic NADH oxidase activity as reported previously (11). Growing WT GBS in respiration-permissive conditions resulted in an ∼6-fold increase in oxygen consumption attributed to stimulation of the respiratory chain (Fig. 4B, respiration). In contrast, the rate of oxygen consumption in the ahpC mutant was about 3.4 times lower than in the respiration-proficient WT strain. The above results give evidence that the absence of AhpC activity leads to a respiration defect. Altogether, these results suggest either a respiration-specific or more general role of AhpC in favoring intracellular hemin utilization.

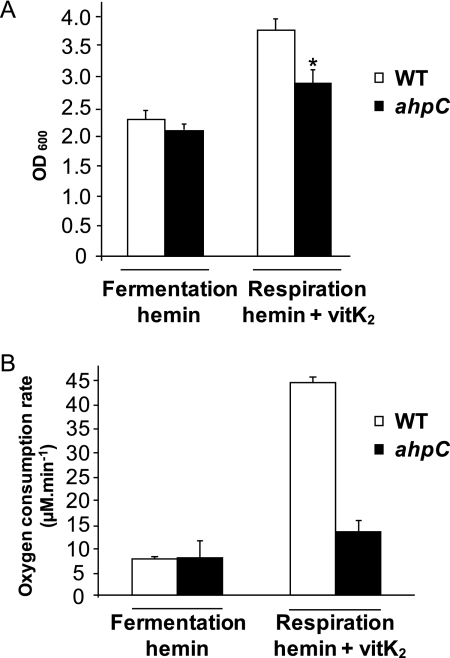

FIGURE 4.

GBS respiration metabolism is attenuated in an ahpC mutant. A, growth of WT and ahpC GBS in respiration-permissive conditions. WT and ahpC GBS strains were grown for 5–6 h in aerated or respiration-permissive (1 μm hemin and 10 μm vitamin K2 (vitK2)) or nonpermissive (1 μm hemin only) conditions in M17 supplemented with 1% glucose. The growth increase under respiration conditions was less pronounced for the ahpC GBS mutant. Results represent the means ± S.D. from at least 10 independent experiments. Asterisk denotes statistically significant reduction of respiration in the ahpC mutant compared with the WT as determined by Student's t test (p < 0.05). B, comparative oxygen consumption rates in WT and ahpC mutants grown as in Fig. 5A. Oxygen consumption was measured on whole cells grown under aerobic fermentation and respiration conditions with a Clark-type electrode as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Oxygen consumption, which is characteristic of respiration metabolism when oxygen is the terminal electron acceptor, was markedly reduced in the ahpC mutant, showing that respiration rate is decreased. Data are normalized to A600 = 1 for both cultures and are means ± S.D. from three experiments.

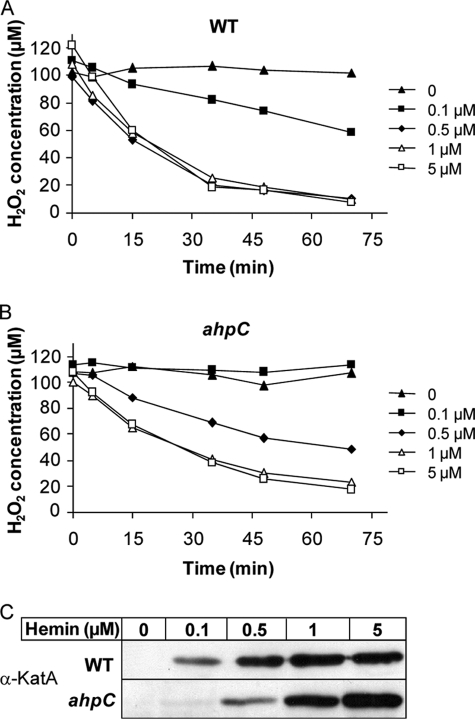

Activity of a Heterologously Expressed Heme-dependent Catalase Is Diminished in the GBS ahpC Mutant

GBS, like most streptococci, is catalase-negative. To further test the potential role of AhpC as an intermediate for intracellular heme availability, we used the heme-dependent E. faecalis catalase A (KatA) as a heterologous indicator to estimate intracellular heme availability (Fig. 5, A and B). KatA stability depends on the presence of heme (42). A plasmid expressing KatA (pLUMB5, kindly provided by L. Hederstedt) was established in WT and ahpC strains, and catalase activity of both strains was evaluated by measuring H2O2 consumption (42). As expected, no catalase activity was detected in either strain in the absence of added hemin (Fig. 5, A and B). In WT GBS, catalase activity was dependent on hemin at low concentrations and reached a maximum at 0.5 μm hemin and above (Fig. 5A). In contrast, in the presence of 0.5 μm hemin, the ahpC mutant exhibited significantly lower catalase activity than the WT strain (Fig. 5B). One explanation for these results is that at low concentrations (<1 μm), hemin cytoplasmic availability for functional KatA expression was lower in the ahpC mutant than in its WT counterpart. This hypothesis was tested (Fig. 5C), using the previous observation that cellular catalase expression levels are proportional to intracellular hemin availability by a post-translational mechanism (41). KatA expression was evaluated by Western blots of bacterial lysates using anti-KatA antibodies (kindly provided by L. Hederstedt). Protein profiles exhibited an extra ∼70-kDa band when WT GBS was grown in the presence of hemin (data not shown), which was confirmed by Western blotting to correspond to KatA (Fig. 5C, WT + hemin). This band was absent in profiles of cultures grown without hemin, confirming that KatA does not accumulate in this condition. Comparatively, KatA expression was lower in the ahpC mutant when bacteria were grown with 0.1 or 0.5 μm hemin (Fig. 5C, ahpC), suggesting that reduced KatA activity in the ahpC mutant is due to decreased enzyme abundance. The above findings lead us to speculate that in the absence of AhpC activity less hemin is available for incorporation in hemoproteins when extracellular concentrations of hemin are low (i.e. <1 μm).

FIGURE 5.

Levels of a heterologous heme catalase are reduced by ahpC inactivation. The E. faecalis catalase A (KatA) was expressed in GBS WT (A) and ahpC (B) strains transformed with pLUMB5 plasmid. Bacteria were incubated overnight with the indicated concentrations of hemin (μm). Catalase activity was assessed by measuring H2O2 consumption on whole cells with the xylenol orange assay (see “Experimental Procedures”). The presented results are representative of three independent experiments. The GBS control (no KatA) has no endogenous catalase activity in the presence of hemin (data not shown). C, KatA expression in WT and ahpC GBS. Cells were grown overnight in the presence of the indicated hemin concentration (μm). Equivalent amounts of protein (50 μg) were separated on SDS-PAGE and probed with anti-KatA polyclonal antibody. The presented results are representative of three independent experiments.

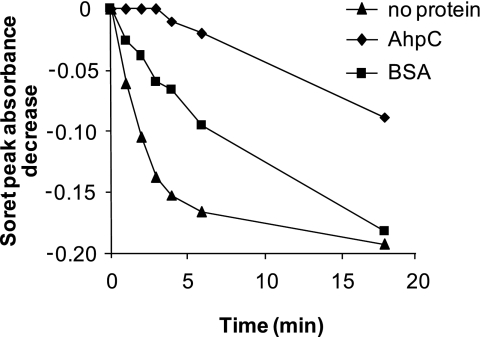

Binding to AhpC Protects Hemin from Nonenzymatic Degradation

The above results led us to ask whether the interaction between hemin and AhpC has a functional role in isolating hemin from a potentially deleterious environment. For example, hemin may be damaged by H2O2 and other ROS that are common by-products of bacterial growth in oxygen. We compared the in vitro sensitivity to H2O2-mediated degradation of hemin in its free form or complexed to AhpC or to another heme-binding protein, BSA (14). Addition of H2O2 to hemin resulted in a rapid decrease of peak absorbance at A385, as reported previously (14), indicating oxidation and partial hemin degradation (Fig. 6). In contrast, when AhpC was complexed with hemin prior to H2O2 addition, hemin decomposition was inhibited, as shown by a limited decrease of A414. In comparison, BSA conferred poor hemin protection (Fig. 6). These data are consistent with our hypothesis that hemin complexed with AhpC is protected from nonenzymatic oxidative degradation.

FIGURE 6.

AhpC-bound hemin is protected from H2O2-mediated degradation. 20 μm hemin alone or in complex with 20 μm His-AhpC or 20 μm BSA were diluted in 50 mm Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.0. Absorption spectra between 300 and 500 nm were taken at the indicated times before (t = 0) and at the indicated times and following the addition of 800 μm H2O2. The decrease in absorbance intensities of the Soret peak of free hemin (at A385) or hemin bound to AhpC or BSA (at A414) were determined from the spectra. Intensities at the indicated time points were subtracted from the respective zero values and plotted. The presented curves are representative of three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

The biochemical and in vivo studies presented here demonstrate that the GBS AhpC, a well known peroxidase belonging to the 2-Cys peroxiredoxin family, is a hemin-binding protein. This finding was unexpected, as this family was described as comprising non-hemin peroxidases (23). Indeed, AhpC activity from several sources has been extensively studied and shown to hydrolyze peroxides in the absence of hemin (24, 44, 52). We found that AhpC variants with substitutions at the redox-active Cys47 and Cys165 positions, which are catalytically inactive and unable to form disulfide bridge between monomers (52), bound hemin like the native enzyme, indicating that hemin binding occurs independently of enzyme function or oligomerization. This excluded involvement of “CP” motifs in the AhpC-heme interaction, despite their implication as heme-binding sites, e.g. of mammalian hemin-oxygenase or E. coli catalase (40, 57, 58). This study is therefore consistent with previous data and shows that hemin binding properties are distinct from enzymatic activity of the protein.

AhpC binds hemin with a Kd of ∼0.5 μm, an affinity lower than those reported for several bacterial cytoplasmic hemin-binding proteins such as ShuS (13 μm) (18), HmuO (2.5 ± 1.0 μm) (59), IsdG (5.0 ± 1.5 μm), and IsdI (3.5 ± 1.4 μm) (60). Interestingly, these values differ from the 55 nm Kd of the rat homologue HBP23 (45). This difference in dissociation constants might be explained if intracellular heme levels in prokaryotes are higher than those in eukaryotic cells (61, 62). Nevertheless, factors such as protein oligomerization or redox state, and hemin redox state, might affect hemin affinity measurements. UV-visible and resonance Raman spectroscopy showed that the heme bound to AhpC is mainly oxidized low spin heme with the presence of a low amount of a subpopulation of high spin hemes. Further studies should lead to the characterization of axial ligands implicated in this interaction.

What physiological function could be attributed to the AhpC-hemin interaction? Hemin is known to provoke the production of highly toxic ROS through the Fenton reaction (13), but it also undergoes redox reactions in the presence of ROS leading to its degradation (13, 63). We therefore considered two hypotheses. First, AhpC could be involved in protecting the cell against hemin toxicity. In this case, AhpC peroxidase activity, coupled to its hemin binding activity, would provide an efficient means of sequestering hemin to protect the cellular environment. However, this hypothesis was not supported, as hemin toxicity was equivalent in WT and ahpC mutant strains. Moreover, hemin of the AhpC-hemin complex exhibited peroxidase activity in vitro (data not shown). The second hypothesis is that AhpC participates in hemin availability by preventing its degradation and facilitating its intracellular transport to cellular targets. Both in vivo and in vitro results support this hypothesis. Two functions that rely on hemin-dependent enzymes, GBS respiration (11) and heterologous catalase KatA activity (64), were diminished in the ahpC mutant. One explanation is that amounts of available intracellular hemin in the ahpC mutant are insufficient for incorporation into the cytochrome oxidase or KatA, thus implicating a role of AhpC as a cytoplasmic hemin chaperone. Because heme is poorly soluble and toxic, our hypothesis is that binding to AhpC, a cytoplasmic protein, would help shuttle heme in the cytoplasmic environment to its binding partners, thereby improving its availability. Thus, the heme incorporated into the catalase would originate at least in part from holo-AhpC. Chaperones for metals or heme have been described previously, transporting metal ions/heme into specific targets and protecting cells from their toxicity (47, 65). CcmE, for example, is a heme chaperone that binds heme transiently in the E. coli periplasm and delivers it to newly synthesized c-type cytochromes (65). Similarly, copper chaperones carry and deliver copper to specific intracellular targets such as superoxide dismutase, cytochrome c, or multicopper oxidase (66). Studies on HBP23, which shares 38% identity with the GBS AhpC, have led to the conclusion that this protein could be an intracellular heme transporter (46, 67).

Previous studies of AhpC provided evidence in favor of our hypothesis. EPR spectroscopy was used to show that the hemin-dependent catalase A activity was affected in an H. pylori ahpC mutant (68). The authors proposed that a proportion of the catalase was bound to catalytically inactive hemin due to oxidative attack by peroxides accumulated in the ahpC mutant (68). Our results provide an additional explanation for these observations, as we show that hemin bound to AhpC protein is less sensitive to redox reactions in the presence of ROS. Both the previous and present data point to a role of AhpC in hemin binding, which protects intracellular hemin from degradation and could be a means to facilitate its utilization by different hemoproteins. Whether this property is unique to AhpC or is common to other GBS hemin-binding proteins remains to be confirmed. In conclusion, our results are consistent with the possibility that AhpC could serve as an intracellular chaperone for heme, to optimize its trafficking and transfer to cellular targets such as catalase.

Interestingly, our results indicating that AhpC peroxidase protects hemin from degradation are consistent with studies in eukaryotes. A role in hemin protection of a family of specific glutathione S-transferases in the hemin auxotroph nematode Caenorhabditis elegans was proposed in a recent proteomic study (69). Interestingly, like AhpC, several glutathione S-transferases possess peroxidase activity. Moreover, a 1-Cys Prx in the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum is expressed at high levels during the hemin-digesting stage and binds hemin. The authors suggested that 1-Cys Prx might slow GSH-mediated degradation of intracellular hemin and consequent iron liberation, thus protecting the parasite from iron-induced toxicity (70). Altogether, these data lead us to speculate that peroxidases other than AhpC could have a role as heme chaperones.

In this study, we show for the first time that bacterial AhpC has hemin binding activity and give evidence for its role in protecting heme from oxidative degradation. We hypothesize that the combination of AhpC peroxidase activity and hemin binding properties would optimize compartmentalization or storage of this reactive molecule. Because peroxiredoxins are highly conserved, our results might apply to other bacteria and provide an additional role for this multifunctional family. We speculate that AhpC could constitute the first identification of a bacterial intracellular protein with heme chaperone-like activities that is expressed in most bacteria.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Céline Henry (Plateau d'Analyse Protéomique par Séquençage et Spectrométrie de Masse, Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique) for mass spectrometry, Lars Hederstedt (Lund University, Sweden) for the generous gift of pLUMB5 plasmid and anti-KatA antibody, and Gergely Lukacs (McGill University, Canada) for the HA antibody. We are grateful to Yuji Yamamoto (Kitasato University, Japan) for sharing unpublished work concerning AhpCF while in the Unité des Bactéries Lactiques et Pathogènes Opportunistes Laboratory. We thank Anne Lecroisey (Institut Pasteur, France) for NMR experiments and valuable comments on the manuscript. We thank Dr. Lars Hederstedt and Claire Poyart (Hôpital Cochin, France) for valuable comments concerning the manuscript, and we are indebted to Cécile Wandersman (Institut Pasteur) for insightful comments. We thank members of the Unité des Bactéries Lactiques et Pathogènes Opportunistes team for discussion and support in the course of this work.

This work was supported in part by a grant for the “StrepRespire” Project from the Agence Nationale de la Recherche, France.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables S1–S4, Figs. S1–S4, and additional references.

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- ALA

- δ-aminolevulinic acid

- GBS

- group B streptococcus

- KatA

- catalase A

- MBP

- maltose-binding protein

- Prx

- peroxiredoxin

- BSA

- bovine serum albumin

- HA

- hemagglutinin

- MALDI-TOF

- matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight

- WT

- wild type.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sutak R., Lesuisse E., Tachezy J., Richardson D. R. (2008) Trends Microbiol. 16, 261–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar S., Bandyopadhyay U. (2005) Toxicol. Lett. 157, 175–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hou S., Reynolds M. F., Horrigan F. T., Heinemann S. H., Hoshi T. (2006) Acc. Chem. Res. 39, 918–924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reniere M. L., Torres V. J., Skaar E. P. (2007) Biometals 20, 333–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mazmanian S. K., Skaar E. P., Gaspar A. H., Humayun M., Gornicki P., Jelenska J., Joachmiak A., Missiakas D. M., Schneewind O. (2003) Science 299, 906–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilks A., Burkhard K. A. (2007) Nat. Prod. Rep. 24, 511–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skaar E. P., Humayun M., Bae T., DeBord K. L., Schneewind O. (2004) Science 305, 1626–1628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wandersman C., Stojiljkovic I. (2000) Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 3, 215–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Obinger C., Maj M., Nicholls P., Loewen P. (1997) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 342, 58–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poole R. K., Hatch L., Cleeter M. W., Gibson F., Cox G. B., Wu G. (1993) Mol. Microbiol. 10, 421–430 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamamoto Y., Poyart C., Trieu-Cuot P., Lamberet G., Gruss A., Gaudu P. (2005) Mol. Microbiol. 56, 525–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Winstedt L., Frankenberg L., Hederstedt L., von Wachenfeldt C. (2000) J. Bacteriol. 182, 3863–3866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagababu E., Rifkind J. M. (2004) Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 6, 967–978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grinberg L., O'Brien P., Hrkal Z. (1999) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 27, 214–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uchida T., Stevens J. M., Daltrop O., Harvat E. M., Hong L., Ferguson S. J., Kitagawa T. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 51981–51988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lansky I. B., Lukat-Rodgers G. S., Block D., Rodgers K. R., Ratliff M., Wilks A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 13652–13662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaur A. P., Lansky I. B., Wilks A. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 56–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilks A. (2001) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 387, 137–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stojiljkovic I., Perkins-Balding D. (2002) DNA Cell Biol. 21, 285–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schneider S., Sharp K. H, Barker P. D., Paoli M. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 32606–32610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doran K. S., Nizet V. (2004) Mol. Microbiol. 54, 23–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clancy A., Loar J. W., Speziali C. D., Oberg M., Heinrichs D. E., Rubens C. E. (2006) Mol. Microbiol. 59, 707–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujii J., Ikeda Y. (2002) Redox Rep. 7, 123–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsumura T., Okamoto K., Iwahara S., Hori H., Takahashi Y., Nishino T., Abe Y. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 284–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jang H. H., Lee K. O., Chi Y. H., Jung B. G., Park S. K., Park J. H., Lee J. R., Lee S. S., Moon J. C., Yun J. W., Choi Y. O., Kim W. Y., Kang J. S., Cheong G. W., Yun D. J., Rhee S. G., Cho M. J., Lee S. Y. (2004) Cell 117, 625–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirotsu S., Abe Y., Okada K., Nagahara N., Hori H., Nishino T., Hakoshima T. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 12333–12338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mu Z. M., Yin X. Y., Prochownik E. V. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 43175–43184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chuang M. H., Wu M. S., Lo W. L., Lin J. T., Wong C. H., Chiou S. H. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 2552–2557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gaillot O., Poyart C., Berche P., Trieu-Cuot P. (1997) Gene 204, 213–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trieu-Cuot P., Courvalin P. (1983) Gene 23, 331–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maguin E., Prévost H., Ehrlich S. D., Gruss A. (1996) J. Bacteriol. 178, 931–935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Biswas I., Gruss A., Ehrlich S. D., Maguin E. (1993) J. Bacteriol. 175, 3628–3635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rezaïki L., Cesselin B., Yamamoto Y., Vido K., van West E., Gaudu P., Gruss A. (2004) Mol. Microbiol. 53, 1331–1342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laemmli U. K. (1970) Nature 227, 680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Urban A., Neukirchen S., Jaeger K. E. (1997) Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 2227–2228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moore R. W., Welton A. F., Aust S. D. (1978) Methods Enzymol. 52, 324–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smalley J. W., Charalabous P., Birss A. J., Hart C. A. (2001) Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 8, 509–514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tong Y., Guo M. (2007) J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 12, 735–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Swillens S. (1995) Mol. Pharmacol. 47, 1197–1203 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yi L., Ragsdale S. W. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 21056–21067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lechardeur D., Xu M., Lukacs G. L. (2004) J. Cell Biol. 167, 851–862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frankenberg L., Brugna M., Hederstedt L. (2002) J. Bacteriol. 148, 6351–6356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wolff S. (1994) Methods Enzymol. 233, 182–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guimarães B. G., Souchon H., Honoré N., Saint-Joanis B., Brosch R., Shepard W., Cole S. T., Alzari P. M. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 25735–25742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iwahara S., Satoh H., Song D. X., Webb J., Burlingame A. L., Nagae Y., Muller-Eberhard U. (1995) Biochemistry 34, 13398–13406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Immenschuh S., Iwahara S., Satoh H., Nell C., Katz N., Muller-Eberhard U. (1995) Biochemistry 34, 13407–13411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frawley E. R., Kranz R. G. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 10201–10206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kitagawa T., Ozaki Y., Kyogoku Y., Horio T. (1977) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 495, 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Othman S., Le Lirzin A., Desbois A. (1994) Biochemistry 33, 15437–15448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuras R., de Vitry C., Choquet Y., Girard-Bascou J., Culler D., Büschlen S., Merchant S., Wollman F. A. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 32427–32435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hughes A. L., Powell D. W., Bard M., Eckstein J., Barbuch R., Link A. J., Espenshade P. J. (2007) Cell Metab. 5, 143–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wood Z. A., Poole L. B., Hantgan R. R., Karplus P. A. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 5493–5504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jani D., Nagarkatti R., Beatty W., Angel R., Slebodnick C., Andersen J., Kumar S., Rathore D. (2008) PLoS Pathog. 4, e1000053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Faller M., Matsunaga M., Yin S., Loo J. A., Guo F. (2007) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 23–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kery V., Elleder D., Kraus J. P. (1995) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 316, 24–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zederbauer M., Furtmüller P. G., Brogioni S., Jakopitsch C., Smulevich G., Obinger C. (2007) Nat. Prod. Rep. 24, 571–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McCoubrey W. K., Jr., Huang T. J., Maines M. D. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 12568–12574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang L., Guarente L. (1995) EMBO J. 14, 313–320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wilks A., Schmitt M. P. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 837–841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Skaar E. P., Gaspar A. H., Schneewind O. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 436–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Muller-Eberhard U., Vincent S. H. (1985) Biochem. Pharmacol. 34, 719–725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sassa S. (2004) Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 6, 819–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kremer M. L. (1989) Eur. J. Biochem. 185, 651–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rochat T., Miyoshi A., Gratadoux J. J., Duwat P., Sourice S., Azevedo V., Langella P. (2005) Microbiology 151, 3011–3018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Enggist E., Schneider M. J., Schulz H., Thöny-Meyer L. (2003) J. Bacteriol. 185, 175–183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kim B. E., Nevitt T., Thiele D. J. (2008) Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 176–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Immenschuh S., Nell C., Iwahara S., Katz N., Muller-Eberhard U. (1997) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 231, 667–670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang G., Conover R. C., Benoit S., Olczak A. A., Olson J. W., Johnson M. K., Maier R. J. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 51908–51914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Perally S., Lacourse E. J., Campbell A. M., Brophy P. M. (2008) J. Proteome Res. 7, 4557–4565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kawazu S., Ikenoue N., Takemae H., Komaki-Yasuda K., Kano S. (2005) FEBS J. 272, 1784–1791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.