Abstract

We have recently shown that β-catenin-facilitated export of cadherins from the endoplasmic reticulum requires PX-RICS, a β-catenin-interacting GTPase-activating protein for Cdc42. Here we show that PX-RICS interacts with isoforms of 14-3-3 and couples the N-cadherin-β-catenin complex to the microtubule-based molecular motor dynein-dynactin. Similar to knockdown of PX-RICS, knockdown of either 14-3-3ζ or -θ resulted in the disappearance of N-cadherin and β-catenin from the cell-cell boundaries. Furthermore, we found that PX-RICS and 14-3-3ζ/θ are present in a large multiprotein complex that contains dynein-dynactin components as well as N-cadherin and β-catenin. Both RNAi- and dynamitin-mediated inhibition of dynein-dynactin function also led to the absence of N-cadherin and β-catenin at the cell-cell contact sites. Our results suggest that the PX-RICS-14-3-3ζ/θ complex links the N-cadherin-β-catenin cargo with the dynein-dynactin motor and thereby mediates its endoplasmic reticulum export.

Keywords: Cell/Adhesion, Cell/Trafficking, Membrane/Trafficking, Molecular Motors/Dynein, Protein/Protein-Protein Interactions, Subcellular Organelles/Endoplasmic Reticulum, Subcellular Organelles/Vesicles, Transport

Introduction

In general, cargo proteins to be exported from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)2 have characteristic amino acid sequences called “ER export motifs” that facilitate their ER exit (1–4). Classic cadherins (simply referred to cadherins hereafter) (5–9), however, are known to have no functional ER export motifs, and their efficient ER exit requires complex formation with β-catenin at the ER immediately after cadherin synthesis (10–12). We have recently shown that this β-catenin-facilitated ER export of cadherins requires PX-RICS, a β-catenin-interacting GTPase-activating protein (GAP) for Cdc42 (13).

PX-RICS is an alternatively spliced isoform of RICS (RhoGAP involved in the β-catenin-N-cadherin and N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor signaling) and contains phox homology (PX) and Src homology 3 domains in its N-terminal region (14, 15). RICS is expressed predominantly in neurons of the brain and localized to the growth cone and postsynaptic density, where it regulates neurite extension and presumably N-methyl-d-aspartate signaling (14). In contrast, PX-RICS is expressed in a wide variety of tissues and cell lines and localized to the ER and cis-Golgi (13, 15). Our recent study has revealed that PX-RICS facilitates ER-to-Golgi transport of the N-cadherin-β-catenin complex through its direct interaction with β-catenin, Cdc42, γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor-associated protein (GABARAP) and phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate (PI4P) (13). This finding suggests that PX-RICS is a key molecule in a novel intracellular transport system that is independent of known ER export motifs and provides a molecular basis that explains why the assembly of cadherins with β-catenin is essential for efficient ER exit of cadherins. However, the precise molecular mechanisms by which PX-RICS triggers ER exit of the N-cadherin-β-catenin complex remain to be elucidated. To address this issue, we attempted to identify PX-RICS-interacting scaffold proteins involved in the PX-RICS-dependent forward transport mechanism. Here we report that PX-RICS and its novel binding partner 14-3-3 proteins link the N-cadherin-β-catenin cargo with the dynein-dynactin motor, thereby regulating the amount of surface N-cadherin available for cell-cell adhesion.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Antibodies

Rabbit polyclonal antibody to PX-RICS was generated as described previously (15). The commercially available antibodies used in this study were as follows. Mouse anti-14-3-3ϵ, mouse anti-β-catenin, and mouse anti-p150Glued antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences; mouse anti-GFP antibody (Living colors A.v. monoclonal antibody (JL-8)) was from Invitrogen; rabbit anti-Myc antibody was from MBL; mouse anti-α-tubulin antibody (DM1A) was from Merck; mouse anti-N-cadherin (13A9) and mouse anti-DYNC1I (74.1) antibodies were from Millipore; mouse anti-Myc (9E10), mouse anti-pan-14-3-3 (H-8), rabbit anti-14-3-3ζ (C-16), goat anti-14-3-3β (A-15), goat anti-14-3-3γ (A-12), goat anti-14-3-3η (E-12), and goat anti-Sec23 (E-19) antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; mouse anti-FLAG (M2) and mouse anti-14-3-3θ (3B9) antibodies were from Sigma; rabbit anti-calnexin antibody was from Stressgen; and mouse anti-transferrin receptor antibody (H68.4) was from Zymed Laboratories Inc.. Rabbit and mouse IgGs were from Millipore.

PX-RICS-derived Mutants

Details of the PX-RICS-derived mutants used in this study are as follows. 1433BR, a fragment of PX-RICS (amino acids 1763–1828), contains a 14-3-3 binding motif (amino acids 1793–1798); ΔRSKSDP and 1433BR-ΔRSKSDP, mutants of PX-RICS and 1433BR, lack the 14-3-3 binding motif, respectively; S1796A and 1433BR-SA are mutants of PX-RICS and 1433BR in which Ser1796, the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) phosphorylation site in the 14-3-3 binding motif, is replaced with Ala. All mutant forms were generated by PCR-based mutagenesis.

Cell Culture and Transfection

HEK293T, COS-7, and HeLa cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone). Cells were transfected with plasmids using FuGENE 6 (Roche Applied Science). For CaMKII inhibition, COS-7 cells were treated with 10 μm KN-93 (Merck) for 24 h.

Identification of PX-RICS-interacting Proteins

HEK293T cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1(+)-FLAG-PX-RICS, and binding proteins were analyzed by direct nano-flow liquid chromatography/electrospray tandem mass spectrometry, as described earlier (16).

Protein Expression and Purification

For preparation of GST fusion proteins, cDNA fragments were subcloned into pGEX-5X-3 (GE Healthcare). GST fusion proteins were synthesized in Escherichia coli and isolated by adsorption to glutathione-Sepharose (GE Healthcare). 35S-Labeled proteins were synthesized by in vitro transcription-translation in the presence of [35S]methionine using the TNTTM coupled reticulocyte lysate system (Promega).

In Vitro Pulldown Assays

Lysates from COS-7 cells (500 μg of protein) or in vitro-translated proteins were incubated with 2 μg of GST or GST fusion proteins in binding buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 140 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 0.1% Triton X-100, protease inhibitor mixture) for 1 h at 4 °C and then with glutathione-Sepharose for 1 h at 4 °C. Beads were washed extensively with binding buffer, and bound proteins were fractionated by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting or autoradiography. For dephosphorylation experiments, lysates from COS-7 cells (500 μg of protein) were treated with 10 units of bacterial alkaline phosphatase (Takara Bio Inc.) for 1 h at 30 °C before pulldown assays. For phosphorylation experiments, in vitro translated PX-RICS was treated with 50 ng of rat brain CaMKII (Merck) for 2 h at 30 °C in the presence of 1 mm Ca2+, 2 mm ATP, 2.5 μg of bovine brain calmodulin (Millipore) in a 50-μl reaction mixture before pulldown assays.

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting

Cells were lysed in lysis buffer T (10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 140 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, protease inhibitor mixture, phosphatase inhibitor mixture). The lysates were precleared with protein A-Sepharose (GE Healthcare) for 1 h at 4 °C. Precleared lysates (500 μg of protein) were incubated with 5 μg of antibody for 1 h at 4 °C, and then the immunocomplexes were adsorbed to protein A-Sepharose for 1 h at 4 °C. After washing extensively with lysis buffer T, immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore). The blots probed with primary antibodies were visualized with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Promega).

Immunofluorescence

HeLa cells were plated on coverslips in 6-well tissue culture plates (1 × 105 cells per well). After 48 h of incubation at 37 °C, cells were fixed with cold methanol for 20 min at −20 °C (for PX-RICS, 14-3-3 or N-cadherin staining) or 2% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at 4 °C (for β-catenin staining) and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in Tris-buffered saline for 5 min. The cells were double-stained with the appropriate combination of primary antibodies for 60 min at room temperature. Staining patterns were visualized by incubating with Alexa Fluor 488- or Alexa Fluor 594-labeled donkey secondary antibody (Invitrogen) for 60 min at room temperature. The cell images were obtained with a LSM510META laser scanning confocal microscope (Zeiss).

RNAi Experiments

Sequences of human CaMKII isoforms targeted by shRNAs are as follows: shRNA-CAMK2A (for the α isoform, 5′-GGGACACCACTACCTGATCTT-3′) and shRNA-CAMK2B (for the β isoform, 5′-CCGCCTTCTGAAGCATTCCAA-3′); shRNA-CAMK2D (for the δ isoform, 5′-ATGCCGCCTGCATAGCATATA-3′) and shRNA-CAMK2G (for the γ isoform, 5′-TGGCCTAGCCATCGAAGTACA-3′) and shRNA-control, (5′-TGAGAGTAGTGACATCCGG-3′). DNA oligonucleotides encoding shRNAs were subcloned into the H1 promoter-driven vector pSUPERretro.puro (OligoEngine). Sequences of Stealth RNAi (Invitrogen) that target the human 14-3-3ζ or -θ, DYNC1I2, or p150Glued gene are as follows: siRNA-ζ-1, 5′-CAGGUGUAGUAAUUGUGGGUACUUU-3′; siRNA-ζ-2, 5′-CAGUUAACAUUUAGGGAGUUAUCUG-3′; siRNA-θ-1, 5′-CCAAACACUUAUGUAGAGGACUAAA-3′; siRNA-θ-2, 5′-CCGGAAGUAUUAGAUUGAAUGGAAA-3′; siRNA-DYNC1I2–1, 5′-GGAGAUUGGAUUUAUGGAAUCUCAA-3′; siRNA-DYNC1I2–2, 5′-CAACUAAGAAUAACAAGCCUUUGUA-3′; siRNA-p150–1, 5′-GGGCAGAAGACAAAGCAAAGCUAAA-3′; siRNA-p150–2, 5′-ACCAUGACUGCGUUCUGGUGCUGUU-3′. Stealth RNAi negative control low GC duplex (Invitrogen) was used as a control. HeLa cells were transfected with the shRNA expression constructs or cotransfected with Stealth RNAi and pSUPERretro.puro using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), cultured for 24 h, and then treated with puromycin (4 μg/ml) for 48 h to remove untransfected cells. Surviving cells were subjected to immunoblotting, immunofluorescence, cell dissociation assays, or cell surface biotinylation assays. For rescue experiments, HeLa cells were cotransfected using Lipofectamine 2000 with Stealth RNAi and the expression plasmid carrying only the coding region of 14-3-3ζ or -θ.

Surface Biotinylation Assays

Biotinylation assays of cell surface proteins were performed as described (17). siRNA-transfected cells were washed 3 times with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1 mm CaCl2 and 0.5 mm MgCl2 (PBS(+)) and incubated with 0.25 mg/ml EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin (Pierce) in PBS(+) for 20 min at 4 °C with gentle agitation. After an immediate rinse with ice-cold quenching buffer (50 mm glycine in PBS(+)), cells were further washed 3 times in ice-cold quenching buffer for 5 min each. The cells were lysed in lysis buffer T, and cleared lysates (0.5 mg of protein) were incubated with 60 μl of 50% slurry of streptavidin-agarose beads (Pierce) for 2 h at 4 °C. Beads were washed five times in lysis buffer T and then once with PBS. Bound proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting.

Cell Dissociation Assays

Cells were scraped in PBS(+) and suspended by 10 times repeated pipetting. The extent of cell dissociation was quantified by counting the number of cell clumps (Np), and the total number of cells (Nc) and was represented by the ratio Nc/Np.

Density Gradient Ultracentrifugation

The density gradient ultracentrifugation was performed as described elsewhere (18). Subconfluent HeLa cells (1 × 107) were washed twice with ice-cold PBS(+) and lysed in 1 ml of lysis buffer D (25 mm Hepes-KOH (pH 6.8), 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 1% digitonin, protease inhibitor mixture, phosphatase inhibitor mixture) at 4 °C for 30 min. After centrifugation at 17,000 × g for 30 min, the supernatant (2 mg of protein/0.5 ml) was layered over an 11.5-ml 10–40% (w/v) linear sucrose density gradient containing 25 mm Hepes-KOH (pH 6.8), 150 mm NaCl, and 0.4% digitonin. After centrifugation for 15 h at 35,000 rpm in a Beckman SW40 rotor, 12 fractions containing 1 ml each were collected from the top of the tube and were subjected to immunoblotting or immunoprecipitation. Protein mobility markers (high molecular weight native marker kit (GE Healthcare)) were applied to a parallel gradient, and their fraction positions were determined by 2–15% native PAGE followed by Coomassie staining.

Live Cell Imaging of N-cadherin and PX-RICS

N-cadherin-GFP and mCherry-PX-RICS expression constructs were created by inserting full-length human N-cadherin and PX-RICS cDNAs into pEGFP-N1 and pmCherry-C1 (Takara Bio Inc.), respectively. Live cell imaging was performed using a Revolution XD system (Andor Technology).

RESULTS

PX-RICS Interacts with 14-3-3ζ and -θ at the ER

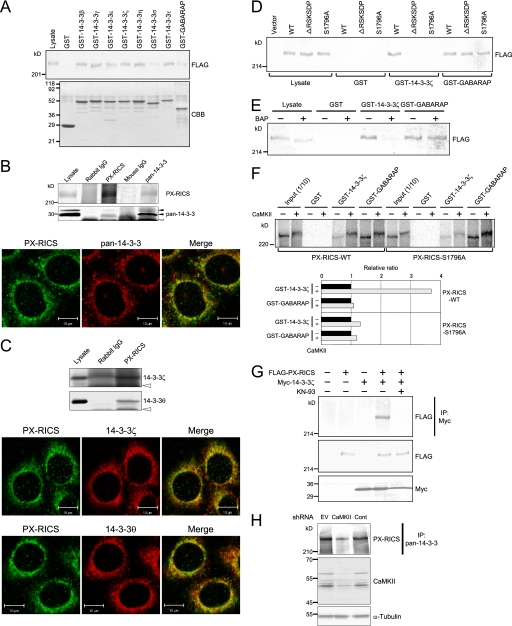

We attempted to identify PX-RICS-interacting proteins involved in the PX-RICS-dependent forward transport mechanism using liquid chromatography-based electrospray tandem mass spectrometry (16). We found that PX-RICS could interact with the β, γ, ϵ, ζ, and η isoforms of 14-3-3 proteins, which have been reported to be involved in diverse biological processes, including intracellular protein transport (19–21). In vitro pulldown assays confirmed that PX-RICS interacts with all seven human isoforms of 14-3-3 proteins (Fig. 1A). 14-3-3σ showed a relatively low binding activity for PX-RICS, whereas the other isoforms exhibited similar high activities.

FIGURE 1.

Phosphorylation of PX-RICS by CaMKII enhances its interaction with 14-3-3 proteins. A, shown is binding of PX-RICS with 14-3-3s in vitro. Lysates from COS-7 cells expressing FLAG-tagged PX-RICS were incubated with GST or GST fusion proteins as indicated, and bound proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-FLAG antibody. The lower panel shows Coomassie staining of GST and GST fusion proteins used in pulldown assays. GST-GABARAP was used as a positive control. B, shown is binding of PX-RICS with 14-3-3s in vivo. HeLa cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with the antibodies indicated above each lane followed by immunoblotting with the antibodies indicated on the right. Solid arrowheads denote 14-3-3s. The open arrowhead denotes the light chain of the antibodies used in immunoprecipitation. Immunofluorescent staining of HeLa cells with anti-PX-RICS and anti-pan-14-3-3 antibody are shown in the lower panel. C, shown is the specific interaction of PX-RICS with the ζ and θ isoforms of 14-3-3s. HeLa cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-PX-RICS antibody followed by immunoblotting with antibodies specific for 14-3-3ζ or -θ. Open arrowheads indicate the light chain of the antibodies used in immunoprecipitation. The lower panel shows immunofluorescent staining of HeLa cells with anti-PX-RICS antibody plus 14-3-3ζ- or θ-specific antibody. D, the internal RSKS DP (the underline indicates Ser1796) sequence of PX-RICS is responsible for its binding to 14-3-3s. Lysates from COS-7 cells expressing FLAG-tagged wild-type PX-RICS or its mutant forms (ΔRSKSDP or S1796A) were incubated with GST-14-3-3ζ, and bound proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-FLAG antibody. WT, wild type. E, phosphorylation of PX-RICS is required for its binding to 14-3-3s. Lysates from COS-7 cells expressing FLAG-PX-RICS were treated with buffer (−) or bacterial alkaline phosphatase (BAP; +) and incubated with GST-14-3-3ζ. Bound proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-FLAG antibody. F, CaMKII-mediated phosphorylation of Ser1796 in the 14-3-3 binding motif of PX-RICS enhances its binding to 14-3-3s. In vitro-translated wild-type and mutant PX-RICS (PX-RICS-WT and -S1796A) were treated with buffer (−) or CaMKII (+) and then subjected to pulldown assays with GST-14-3-3ζ. The representative results of densitometric quantification of precipitated PX-RICS are shown in the lower panel. G, binding of PX-RICS to 14-3-3 is inhibited by a CaMKII inhibitor. COS-7 cells expressing FLAG-tagged PX-RICS and/or Myc-tagged 14-3-3ζ were treated with KN-93 as indicated. The amount of PX-RICS bound to 14-3-3ζ was analyzed. H, decreased interaction of endogenous PX-RICS with 14-3-3 proteins due to CaMKII knockdown is shown. Lysates from HeLa cells transfected with an empty shRNA vector (EV), a mixture of four shRNAs for CaMKII isoforms (CaMKII), or control shRNA were analyzed by immunoprecipitation (IP) followed by immunoblotting.

We next examined whether PX-RICS is associated with 14-3-3s in vivo. When lysates from HeLa cells were subjected to coimmunoprecipitation experiments, 14-3-3s were found to coprecipitate with PX-RICS, and vice versa (Fig. 1B). We also investigated whether 14-3-3s are colocalized with PX-RICS, which is present at the ER (13). We found that both PX-RICS and 14-3-3s are stained as reticular or punctate patterns, and a significant fraction of these proteins colocalize, especially in the perinuclear region (Fig. 1B). These results suggest that PX-RICS is associated with 14-3-3s at the ER in living cells.

Despite the high sequence homology among 14-3-3 isoforms, not all ligands show equal affinities for different 14-3-3 isoforms (19, 22). We, therefore, examined whether PX-RICS preferentially interacts with a particular isoform(s) of 14-3-3s using isoform-specific antibodies. We found that the β, γ, and η isoforms were expressed at the extremely low levels, but the ϵ, ζ, and θ isoforms were abundantly expressed in HeLa cells (data not shown). In vivo pulldown assays with HeLa cell lysates revealed that the ζ and θ isoforms, but not the ϵ isoform, coprecipitated with PX-RICS (Fig. 1C and data not shown). Immunofluorescent staining also revealed that PX-RICS is colocalized with the ζ and θ isoforms, but not the ϵ isoform, in the perinuclear region (Fig. 1C and data not shown). These results suggest that PX-RICS interacts specifically with the ζ and θ isoforms of 14-3-3 proteins.

CaMKII-mediated Phosphorylation of PX-RICS Regulates Its Binding to 14-3-3ζ

PX-RICS contains a putative 14-3-3 binding motif RSKSDP near its C terminus that is consistent with the well characterized consensus sequence for 14-3-3 binding, RSX(pS/pT)XP (X, any amino acid; pS, phospho-Ser; pT, phospho-Thr) (19, 22). To determine whether this motif acts as a 14-3-3-binding site, we constructed a deletion mutant of PX-RICS (ΔRSKSDP) in which the entire RSKSDP sequence has been removed. In vitro pulldown assays revealed that GST-14-3-3ζ was able to precipitate FLAG-tagged wild-type PX-RICS, but not ΔRSKSDP, from COS-7 cell lysates (Fig. 1D). Thus, 14-3-3 proteins may bind to the RSKSDP sequence of PX-RICS.

Phosphorylation of a serine/threonine residue in the 14-3-3 binding motif is known to be required for interaction with 14-3-3s (19, 22). Hence, we investigated whether binding of PX-RICS to 14-3-3s is dependent on serine phosphorylation of the RSKSDP sequence. To this end, we utilized a point mutant of PX-RICS (S1796A) in which Ser1796, the second serine residue in the 14-3-3 binding motif, was replaced with Ala. We found that S1796A lacks the ability to interact with GST-14-3-3ζ (Fig. 1D). To confirm this, we performed pulldown assays using lysates from PX-RICS-expressing COS-7 cells that had been pretreated with bacterial alkaline phosphatase. We found that GST-14-3-3ζ failed to precipitate PX-RICS from the bacterial alkaline phosphatase-treated lysates (Fig. 1E). These results suggest that phosphorylation of Ser1796 in the 14-3-3 binding motif of PX-RICS is required for its interaction with 14-3-3s.

Inspection of the amino acid sequence of PX-RICS revealed that its 14-3-3 binding motif overlaps with a motif required for phosphorylation by CaMKII, RXX(S/T) (23). We, therefore, asked whether CaMKII phosphorylates Ser1796 of PX-RICS and, if so, whether this phosphorylation promotes the interaction between PX-RICS and 14-3-3s. In vitro translated wild-type PX-RICS and S1796A were treated or not with CaMKII and then subjected to pulldown assays using GST-14-3-3ζ. We found that the amount of wild-type PX-RICS associated with 14-3-3ζ was increased more than 3-fold by CaMKII treatment (Fig. 1F). In contrast, the amount of S1796A associated with 14-3-3ζ was not changed by CaMKII treatment. Furthermore, when we coexpressed FLAG-tagged PX-RICS and Myc-tagged 14-3-3ζ in COS-7 cells and treated the cells with the cell-permeable CaMKII inhibitor KN-93, coprecipitation of PX-RICS with 14-3-3ζ was markedly inhibited (Fig. 1G). Similarly, shRNA-mediated knockdown of CaMKII isoforms reduced the interaction between endogenous PX-RICS and 14-3-3 proteins (Fig. 1H). Taken together, these results suggest that CaMKII-mediated phosphorylation of PX-RICS at the 14-3-3 binding motif enhances its ability to interact with 14-3-3 proteins.

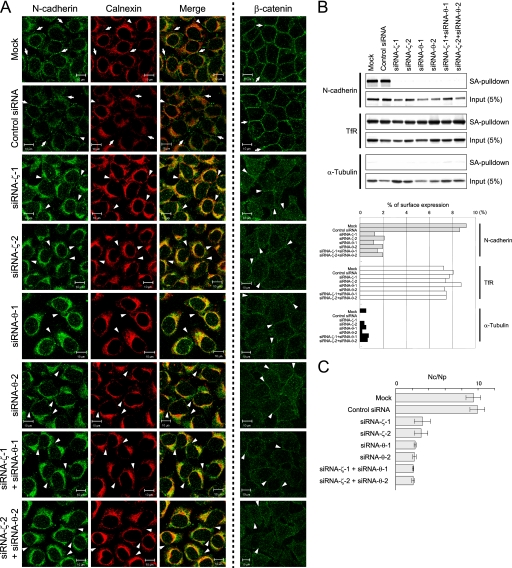

14-3-3ζ/θ Is Required for PX-RICS-mediated N-cadherin-β-Catenin Transport

14-3-3 proteins are known to be involved in intracellular protein transport (19–21). Thus, we examined whether 14-3-3ζ and -θ are involved in PX-RICS-mediated ER-to-Golgi transport of the N-cadherin-β-catenin complex. We generated siRNAs that target the 3′-untranslated region of human 14-3-3ζ (siRNAζ-1 and -2) and -θ (siRNA-θ-1 and -2), respectively (supplemental Fig. S1A) and examined their effects on the intracellular localization of N-cadherin and β-catenin. When HeLa cells were transfected with siRNA for 14-3-3ζ or -θ, N-cadherin and β-catenin disappeared from the cell-cell contact sites (Fig. 2A). Double immunofluorescent staining with antibodies to N-cadherin and calnexin, an ER-resident protein, revealed that a significant fraction of N-cadherin was retained in the ER (Fig. 2A). Double knockdown of 14-3-3ζ and -θ resulted in no apparent synergistic effect on the intracellular localization of N-cadherin and β-catenin (Fig. 2A). Cell surface biotinylation assays also revealed that the amount of cell surface N-cadherin is markedly reduced in siRNA-expressing cells (Fig. 2B). We further examined by cell dissociation assays whether knockdown of 14-3-3ζ or -θ affects the cell adhesion ability of HeLa cells. We found that after mechanical dispersal in the presence of Ca2+, control cells remained as large aggregates, but cells transfected with siRNA against 14-3-3ζ or -θ dissociated efficiently to nearly single cells (Fig. 2C). These results suggest that knockdown of 14-3-3ζ or -θ leads to the reduction in the amount of N-cadherin at the cell surface and consequent reduction in the cell-cell adhesion ability. These phenotypes are identical to those of PX-RICS- and GABARAP-knockdown cells (13), suggesting that 14-3-3ζ and -θ are involved in PX-RICS-mediated transport of the N-cadherin-β-catenin complex.

FIGURE 2.

14-3-3ζ/θ is involved in ER-to-Golgi transport of the N-cadherin-β-catenin complex. A, knockdown of 14-3-3ζ or -θ results in the disappearance of N-cadherin and β-catenin at the cell-cell boundaries and the ER accumulation of N-cadherin. HeLa cells transfected with the indicated siRNAs were subjected to immunofluorescent staining with anti-N-cadherin plus anti-calnexin or anti-β-catenin antibody. Arrows indicate N-cadherin or β-catenin enriched at the sites of cell-cell contact. Arrowheads indicate the absence of N-cadherin and β-catenin at the borders between two neighboring cells. Scale bars, 10 μm. B, upper panel, knockdown of 14-3-3ζ or -θ inhibits the surface expression of N-cadherin. The amounts of total and surface N-cadherin in siRNA-transfected HeLa cells were evaluated by surface biotinylation assays. Transferrin receptor (TfR) and α-tubulin were used for positive and negative controls, respectively. Lower panel, surface expression of N-cadherin was quantified by measuring the band intensity of the biotinylated fraction (SA pulldown in the upper panel) compared with that of total input. Representative results of the three independent experiments are shown. C, Ca2+-dependent cell adhesion is abrogated by knockdown of 14-3-3ζ or -θ. HeLa cells expressing the indicated siRNAs were dissociated by pipetting in the presence of Ca2+. Cell adhesion activity was quantified by counting the total number of cells (Nc) and the number of particles (cell clumps) (Np). Error bars represent the mean ± S.D. (n = 6).

Because 14-3-3 proteins are known to function as homo- or heterodimers that can interact with a wide variety of substrate proteins (19, 22), we examined the functional interaction between 14-3-3ζ and -θ. When 14-3-3ζ lacking its 3′-untranslated region was overexpressed in cells transfected with siRNA targeting the 3′-untranslated region of 14-3-3ζ, N-cadherin and β-catenin were found to be localized at the cell-cell boundaries (supplemental Figs. S1B and S2). However, overexpression of 14-3-3ζ did not restore the localization of N-cadherin and β-catenin in cells transfected with siRNA against 14-3-3θ. Similar results were obtained when 14-3-3θ, lacking its 3′-untranslated region, was overexpressed. In addition, the aberrant localization of N-cadherin and β-catenin in cells transfected with siRNAs against 14-3-3ζ and -θ was rescued only by cotransfection of 14-3-3ζ and -θ but not 14-3-3ζ or -θ alone (supplemental Figs. S1B and S2). These results suggest that heterodimeric 14-3-3ζ/θ is involved in transport of the N-cadherin-β-catenin complex.

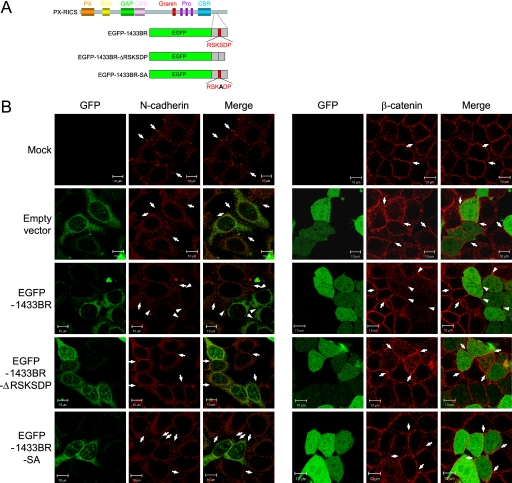

Complex Formation between PX-RICS and 14-3-3ζ/θ Is Essential for N-cadherin-β-Catenin Transport

We next assessed the significance of the interaction between PX-RICS and 14-3-3ζ/θ in transport of the N-cadherin-β-catenin complex. For this purpose, we expressed in HeLa cells a fragment of PX-RICS fused to EGFP (EGFP-1433BR) that interferes with the interaction between PX-RICS and 14-3-3ζ/θ (Fig. 3A and supplemental Fig. S1C) and examined its effects on the subcellular localization of N-cadherins and β-catenin. We found that the amounts of N-cadherin and β-catenin at the cell-cell contact sites were markedly reduced in EGFP-1433BR-expressing cells compared with the surrounding untransfected cells (Fig. 3B). In contrast, such changes were not induced by expression of mutant forms of EGFP-1433BR, EGFP-1433BR-ΔRSKSDP, or EGFP-1433BR-SA (Fig. 3B), which are unable to interfere with the interaction between PX-RICS and 14-3-3ζ/θ (supplemental Fig. S1C). These results suggest that the interaction between PX-RICS and 14-3-3ζ/θ is essential for PX-RICS-mediated transport of the N-cadherin-β-catenin complex.

FIGURE 3.

Complex formation of PX-RICS with 14-3-3ζ/θ is essential for ER-to-Golgi transport of the N-cadherin-β-catenin complex. A, schematic representation of PX-RICS-derived mutants is shown. SH3, Src homology 3 domain; GBR, GABARAP-binding region; Granin, granin motif; Pro-rich, polyproline stretch; CBR, β-catenin binding region. Green rectangles indicate the EGFP tag. The 14-3-3-binding motif is intact in EGFP-1433BR but deleted or mutated in the other two mutants. B, inhibition of the interaction between PX-RICS and 14-3-3ζ/θ results in the disappearance of N-cadherin and β-catenin from the cell-cell boundaries. HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated constructs and processed for immunostaining with anti-N-cadherin or anti-β-catenin antibody. Arrows indicate N-cadherin and β-catenin enriched in the cell-cell boundaries. Arrowheads indicate the N-cadherin- or β-catenin-negative boundaries of HeLa cells expressing PX-RICS-derived mutants. Scale bars, 10 μm.

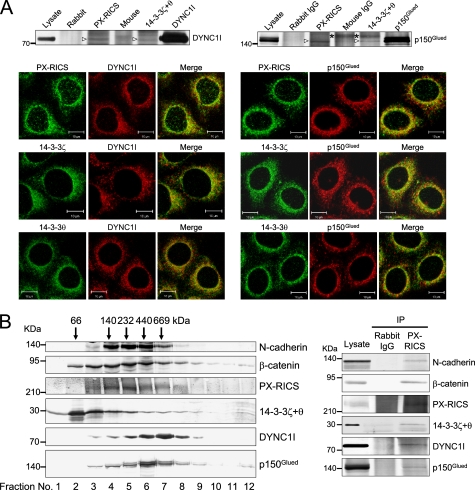

PX-RICS-14-3-3-associated Dynein-Dynactin Is Responsible for N-cadherin-β-Catenin Transport

Recent proteomic analyses of putative 14-3-3-binding partners have identified many proteins that are involved in intracellular vesicular transport, including the dynein-dynactin motor (20, 21, 24–28). Thus, we explored whether PX-RICS and 14-3-3ζ/θ are associated with components of forward transport machineries. In vivo pulldown assays showed that PX-RICS and 14-3-3ζ/θ coimmunoprecipitated with the intermediate chain of cytoplasmic dynein (DYNC1I) and the p150 subunit of dynactin (p150Glued) (Fig. 4A). Consistent with this result, immunofluorescent staining revealed that the intracellular localization of these proteins overlapped significantly in the perinuclear region (Fig. 4A). In contrast, Sec23, a core component of the COPII coat protein complex, did not coprecipitate with PX-RICS or 14-3-3ζ/θ (data not shown). To further confirm the presence of a large multimeric complex assembled from the above-mentioned proteins, we fractionated digitonin-solubilized proteins on a linear sucrose density gradient. Pulldown assays revealed that N-cadherin, β-catenin, PX-RICS, 14-3-3ζ/θ, DYNC1I, and p150Glued coimmunoprecipitated with PX-RICS from fractions corresponding to a molecular mass larger, but not smaller than 669 kDa (Fig. 4B and data not shown). Taken together, these results suggest that N-cadherin, β-catenin, PX-RICS, 14-3-3ζ/θ, DYNC1I, and p150Glued are components of the multiprotein complex having a molecular mass of >669 kDa.

FIGURE 4.

The PX-RICS-14-3-3ζ/θ complex links the N-cadherin-β-catenin complex with the cytoplasmic dynein-dynactin motor. A, upper panels, PX-RICS and 14-3-3ζ/θ are associated with the cytoplasmic dynein-dynactin complex. HeLa cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-PX-RICS or anti-14-3-3ζ/θ antibody followed by immunoblotting with antibodies specific for DYNC1I or p150Glued. Open arrowheads indicate DYNC1I or p150Glued coimmunoprecipitated with PX-RICS or 14-3-3ζ/θ. Asterisks indicate proteins immunoprecipitated nonspecifically. Lower panels, PX-RICS, 14-3-3ζ and 14-3-3θ were colocalized with DYNC1I and p150Glued at the perinuclear region in HeLa cells. Scale bars, 10 μm. B, PX-RICS assembles with N-cadherin, β-catenin, 14-3-3ζ/θ, DYNC1I, and p150Glued to form a large multiprotein complex. Left panel, lysates from HeLa cells solubilized with 1% digitonin were fractionated by sucrose density gradient (10–40%) ultracentrifugation, and each fraction was subjected to immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. Arrows at the top indicate the mobilities of protein molecular weight markers. Right panel, fractions 7 and 8, the highest molecular weight fractions that contain all of the above-mentioned proteins, were pooled and immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-PX-RICS antibody followed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies.

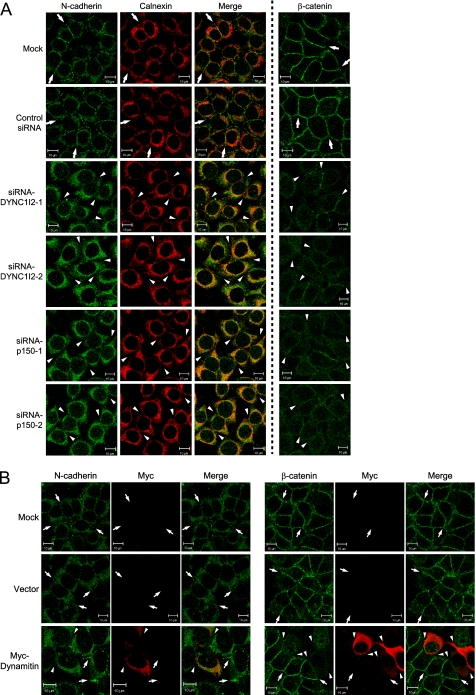

We next investigated whether dynein-dynactin is involved in N-cadherin-β-catenin trafficking by siRNA-mediated depletion of DYNC1I and p150Glued. There are two distinct genes for DYNC1I, DYNC1I1 and DYNC1I2. The former is expressed exclusively in neurons, whereas the latter is expressed ubiquitously (29). Thus, we targeted DYNC1I2 for siRNA-based silencing of DNYC1I in HeLa cells (supplemental Fig. S1D). In DYNC1I2 knockdown cells, N-cadherin and β-catenin disappeared from the cell-cell boundaries as in PX-RICS- or 14-3-3ζ- or -θ knockdown cells (Fig. 5A). A significant fraction of N-cadherin was retained in the ER, as shown by coimmunostaining with calnexin (Fig. 5A). Silencing of p150Glued also led to a similar phenotype (supplemental Fig. S1D and Fig. 5A). We also disrupted dynein motor function by overexpression of dynamitin, which disassembles dynactin, an activator of cytoplasmic dynein (30) (supplemental Fig. S1E). In dynamitin-expressing cells, the amounts of N-cadherin and β-catenin at the cell-cell boundaries were markedly reduced compared with the surrounding untransfected cells (Fig. 5B). These results suggest that PX-RICS-14-3-3ζ/θ-dependent transport of the N-cadherin-β-catenin complex is mediated by dynein-dynactin.

FIGURE 5.

Inhibition of dynein-dynactin function leads to the absence of N-cadherin and β-catenin at the cell-cell contact sites. A, knockdown of DYNC1I or p150Glued results in the disappearance of N-cadherin and β-catenin from the cell-cell boundaries. HeLa cells transfected with the indicated siRNAs were subjected to immunofluorescent staining with anti-N-cadherin plus anti-calnexin or anti-β-catenin antibody. Arrows indicate N-cadherin or β-catenin enriched at the sites of cell-cell contact. Arrowheads indicate the absence of N-cadherin and β-catenin at the borders between two neighboring cells. Scale bars, 10 μm. B, the disappearance of N-cadherin and β-catenin from the cell-cell boundaries due to dynamitin-mediated abrogation of dynein motor function is shown. Arrows indicate N-cadherin and β-catenin enriched in the cell-cell boundaries. Arrowheads indicate the N-cadherin- or β-catenin-negative boundaries of HeLa cells expressing Myc-tagged dynamitin. Scale bars, 10 μm.

PX-RICS Moves Together with N-cadherin

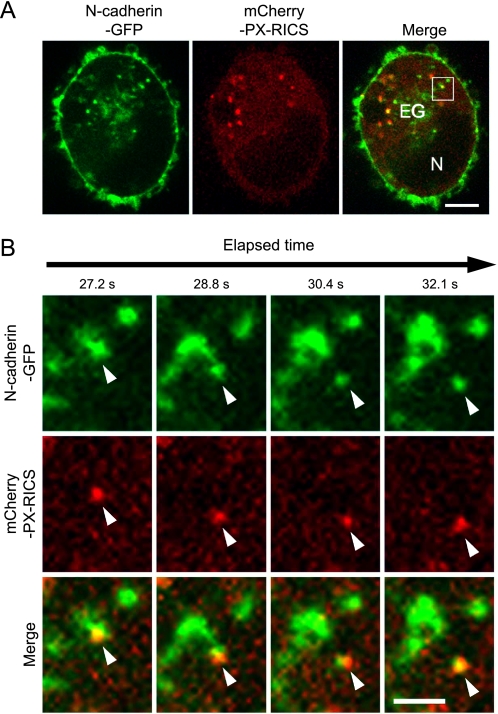

To obtain further evidence for the involvement of PX-RICS in N-cadherin transport, we attempted to visualize the intracellular movement of N-cadherin and PX-RICS using time-lapse microscopic imaging of HeLa cells expressing N-cadherin-GFP and mCherry-PX-RICS. We found that N-cadherin-GFP and mCherry-PX-RICS are colocalized on the same vesicles and move together around the ER/Golgi-like field (Fig. 6A and supplemental Video S1). Some vesicles carrying both N-cadherin-GFP and mCherry-PX-RICS showed straight, long rang, and centrifugal movements (Fig. 6B). These results are consistent with our notion that PX-RICS plays an important role in N-cadherin transport.

FIGURE 6.

Time-lapse images of N-cadherin-GFP and mCherry-PX-RICS in HeLa cells. Corresponding video images are available in supplemental Video S1. A, shown still photographs from supplemental Video S1 (at 27.2 s) of a HeLa cell expressing N-cadherin-GFP (green) and mCherry-PX-RICS (red). EG, ER/Golgi-like field; N, nucleus. Scale bar, 5 μm. B, magnified time-lapse images of the region boxed in A. Arrowheads indicate a typical moving vesicle that harbors both N-cadherin-GFP and mCherry-PX-RICS. Scale bar, 3 μm.

DISCUSSION

Despite the growing list of membrane proteins requiring 14-3-3 for efficient cell surface expression, the molecular mechanism by which 14-3-3 proteins exert this effect remains poorly understood (20, 21). In this study we have shown that PX-RICS interacts with 14-3-3ζ/θ to couple the N-cadherin-β-catenin cargo with the dynein-dynactin motor and thereby mediates its ER-to-Golgi transport. Our finding provides novel insights into how proteins of the 14-3-3 family promote the cell surface expression of membrane proteins.

In our knockdown/rescue experiments, we have found that exogenous expression of 14-3-3ζ or -θ can restore the intracellular localization of N-cadherin and β-catenin in 14-3-3ζ- or θ-knockdown cells, but not in 14-3-3θ- or ζ-knockdown cells (supplemental Fig. S1B and S2). In addition, the localization of N-cadherin and β-catenin in 14-3-3ζ/θ double-knockdown cells was rescued only by cointroduction of both ζ and θ isoforms but not by either the ζ or θ isoform (supplemental Fig. S1B and S2). These results suggest that heterodimeric 14-3-3ζ/θ is involved in transport of the N-cadherin-β-catenin complex. Thus, it is reasonable that knockdown of either the ζ or θ isoform yields similar phenotypic outputs. N-cadherin was found to be stuck in the ER as clearly demonstrated by double immunofluorescence (Fig. 2A), suggesting that these knockdown phenotypes could be attributed to blocked ER-to-Golgi transport but not to aberrant post-Golgi trafficking, including aberrant surface expression, membrane anchoring, endocytosis, or recycling.

Putting our previous and present findings together, we propose a possible model for the action of PX-RICS and its interacting molecules during ER exit of the N-cadherin-β-catenin complex (supplemental Fig. S3). Our previous results suggest that PX-RICS-mediated ER-to-Golgi transport of the N-cadherin-β-catenin complex is dependent on multiple protein-protein (PX-RICS-GABARAP, -Cdc42, and -β-catenin) and protein-lipid (PX-RICS-PI4P) interactions (13). The PX domain of PX-RICS has the highest binding affinity for PI4P (15), which is a predominant phosphoinositide in the ER and Golgi membranes and plays important roles in vesicular budding and/or fusion (31–34). GABARAP is known to be associated with the ER membrane presumably through its hydrophobic phosphatidylethanolamine tail (35, 36). Thus, PX-RICS may be selectively recruited to the ER membrane through its coincident interaction with PI4P and GABARAP (32) and link the N-cadherin-β-catenin cargo with GABARAP. GABARAP may act as a binding cue to stabilize the interaction between PI4P and PX-RICS (32). 14-3-3ζ/θ heterodimer may serve as a linker to mediate the interaction between ER-anchored PX-RICS and the dynein-dynactin motor complex (19–21). Importantly, GABARAP is also known to have the ability to bind microtubules (37). The concerted action of these molecules may provide the driving force for ER exit and/or transport of the N-cadherin-β-catenin cargo along GABARAP-bound microtubules. The substrate diversity of 14-3-3 proteins may enable them to utilize other adaptor proteins in place of PX-RICS, thus allowing the dynein-dynactin motor to carry different cargo proteins without canonical ER export motifs. Similar cargo-adaptor-motor systems have also been proposed for the kinesin superfamily of proteins, another family of cytoplasmic molecular motors (38–40). Thus, the diversity of adaptors may be a common feature by which limited types of molecular motors can recognize a wide array of cargos.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by grants-in-aid for scientific research on Priority Areas, Cell Innovation, Genome Network Project, and in part by the Global Centers of Excellence (COE) Program (Integrative Life Science Based on the Study of Biosignaling Mechanisms), Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Video S1 and Fig. S1–S3.

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- GAP

- GTPase-activating protein

- RICS

- RhoGAP involved in the β-catenin-N-cadherin and N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor signaling

- PX

- phox homology

- GABARAP

- γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor-associated protein

- PI4P

- phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate

- CaMKII

- Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- GST

- glutathione S-transferase

- shRNA

- short hairpin RNA

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- GFP

- green fluorescence protein

- EGFP

- enhanced GFP.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barlowe C. (2003) Trends Cell Biol. 13, 295–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kappeler F., Klopfenstein D. R., Foguet M., Paccaud J. P., Hauri H. P. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 31801–31808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nishimura N., Balch W. E. (1997) Science 277, 556–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sato K., Nakano A. (2002) Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 2518–2532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gallin W. J., Edelman G. M., Cunningham B. A. (1983) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 80, 1038–1042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halbleib J. M., Nelson W. J. (2006) Genes Dev. 20, 3199–3214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peyriéras N., Hyafil F., Louvard D., Ploegh H. L., Jacob F. (1983) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 80, 6274–6277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takeichi M. (2007) Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8, 11–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshida C., Takeichi M. (1982) Cell 28, 217–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Y. T., Stewart D. B., Nelson W. J. (1999) J. Cell Biol. 144, 687–699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kurth T., Fesenko I. V., Schneider S., Münchberg F. E., Joos T. O., Spieker T. P., Hausen P. (1999) Dev. Dyn. 215, 155–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wahl J. K., 3rd, Kim Y. J., Cullen J. M., Johnson K. R., Wheelock M. J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 17269–17276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakamura T., Hayashi T., Nasu-Nishimura Y., Sakaue F., Morishita Y., Okabe T., Ohwada S., Matsuura K., Akiyama T. (2008) Genes Dev. 22, 1244–1256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okabe T., Nakamura T., Nishimura Y. N., Kohu K., Ohwada S., Morishita Y., Akiyama T. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 9920–9927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayashi T., Okabe T., Nasu-Nishimura Y., Sakaue F., Ohwada S., Matsuura K., Akiyama T., Nakamura T. (2007) Genes Cells 12, 929–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Natsume T., Yamauchi Y., Nakayama H., Shinkawa T., Yanagida M., Takahashi N., Isobe T. (2002) Anal. Chem. 74, 4725–4733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nasu-Nishimura Y., Hurtado D., Braud S., Tang T. T., Isaac J. T., Roche K. W. (2006) J. Neurosci. 26, 7014–7021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu G., Chen F., Levesque G., Nishimura M., Zhang D. M., Levesque L., Rogaeva E., Xu D., Liang Y., Duthie M., St George-Hyslop P. H., Fraser P. E. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 16470–16475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aitken A. (2006) Semin. Cancer Biol. 16, 162–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mrowiec T., Schwappach B. (2006) Biol. Chem. 387, 1227–1236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shikano S., Coblitz B., Wu M., Li M. (2006) Trends Cell Biol. 16, 370–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gardino A. K., Smerdon S. J., Yaffe M. B. (2006) Semin. Cancer Biol. 16, 173–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mukherji S., Soderling T. R. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 14062–14067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dorner C., Ullrich A., Häring H. U., Lammers R. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 33654–33660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gavin A. C., Aloy P., Grandi P., Krause R., Boesche M., Marzioch M., Rau C., Jensen L. J., Bastuck S., Dümpelfeld B., Edelmann A., Heurtier M. A., Hoffman V., Hoefert C., Klein K., Hudak M., Michon A. M., Schelder M., Schirle M., Remor M., Rudi T., Hooper S., Bauer A., Bouwmeester T., Casari G., Drewes G., Neubauer G., Rick J. M., Kuster B., Bork P., Russell R. B., Superti-Furga G. (2006) Nature 440, 631–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jin J., Smith F. D., Stark C., Wells C. D., Fawcett J. P., Kulkarni S., Metalnikov P., O'Donnell P., Taylor P., Taylor L., Zougman A., Woodgett J. R., Langeberg L. K., Scott J. D., Pawson T. (2004) Curr. Biol. 14, 1436–1450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meek S. E., Lane W. S., Piwnica-Worms H. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 32046–32054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pozuelo Rubio M., Geraghty K. M., Wong B. H., Wood N. T., Campbell D. G., Morrice N., Mackintosh C. (2004) Biochem. J. 379, 395–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pfister K. K., Shah P. R., Hummerich H., Russ A., Cotton J., Annuar A. A., King S. M., Fisher E. M. (2006) PLoS Genet. 2, e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schroer T. A. (2004) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 20, 759–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Matteis M., Godi A., Corda D. (2002) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 14, 434–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Di Paolo G., De Camilli P. (2006) Nature 443, 651–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Audhya A., Foti M., Emr S. D. (2000) Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 2673–2689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bruns J. R., Ellis M. A., Jeromin A., Weisz O. A. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 2012–2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kittler J. T., Rostaing P., Schiavo G., Fritschy J. M., Olsen R., Triller A., Moss S. J. (2001) Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 18, 13–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kabeya Y., Mizushima N., Yamamoto A., Oshitani-Okamoto S., Ohsumi Y., Yoshimori T. (2004) J. Cell Sci. 117, 2805–2812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang H., Olsen R. W. (2000) J. Neurochem. 75, 644–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hirokawa N., Takemura R. (2004) Exp. Cell Res. 301, 50–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karcher R. L., Deacon S. W., Gelfand V. I. (2002) Trends Cell Biol. 12, 21–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Teng J., Rai T., Tanaka Y., Takei Y., Nakata T., Hirasawa M., Kulkarni A. B., Hirokawa N. (2005) Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 474–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.