Abstract

Varices that occur at sites other than the esophagogastric area are termed ectopic varices. An ileal varix is a very rare cause of lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Although ileal varices are generally associated with prior intra-abdominal surgery and adhesions, an arteriovenous malformation (AVM) in the ileocecal area can cause ileal varices and bleeding in patients with portal hypertension who have not received previous intra-abdominal surgery, which is due to an intestinal or colonic AVM dilating the collateral veins and further aggravating portal hypertension. Surgical treatment should be considered in patients with massive ectopic variceal bleeding. We report a case of massive ileocecal variceal bleeding associated with an AVM that occurred in a patient with alcoholic liver cirrhosis.

Keywords: Ileocecal varix, Arteriovenous malformation, Portal hypertension

INTRODUCTION

Esophagogastric variceal bleeding is a frequent complication of the portal hypertension. In the setting of the portal hypertension, portosystemic collaterals can occur anywhere along the gastrointestinal tract. Ectopic variceal bleeding, which is defined as bleeding from outside the esophagogastric lesion, is an uncommon life-threatening complication of portal hypertension.1 Bleeding from ileal varices is far less frequent and the reported cases seem to be associated with prior intra-abdominal surgery and adhesions.2-5 However, considering that intestinal and colonic arteriovenous malformation (AVM) could cause dilated collateral veins and aggravate portal hypertension,6,9 AVM in the ileocecal area can cause ileal varices and bleeding in patients with the portal hypertension without previous intra-abdominal surgery. We report a case of massive bleeding from the ileocecal varices associated with AVM in a patient with alcoholic liver cirrhosis.

CASE REPORT

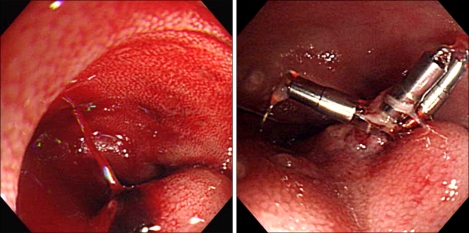

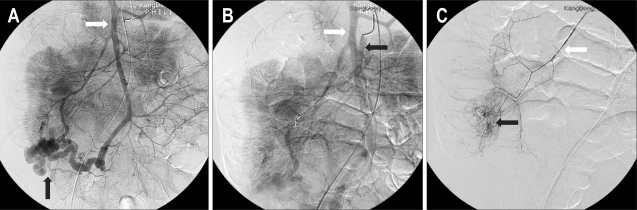

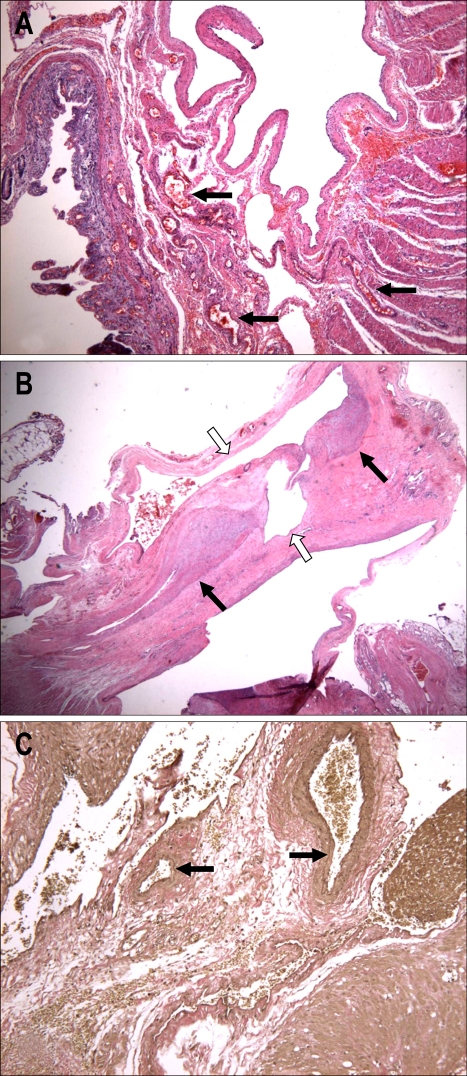

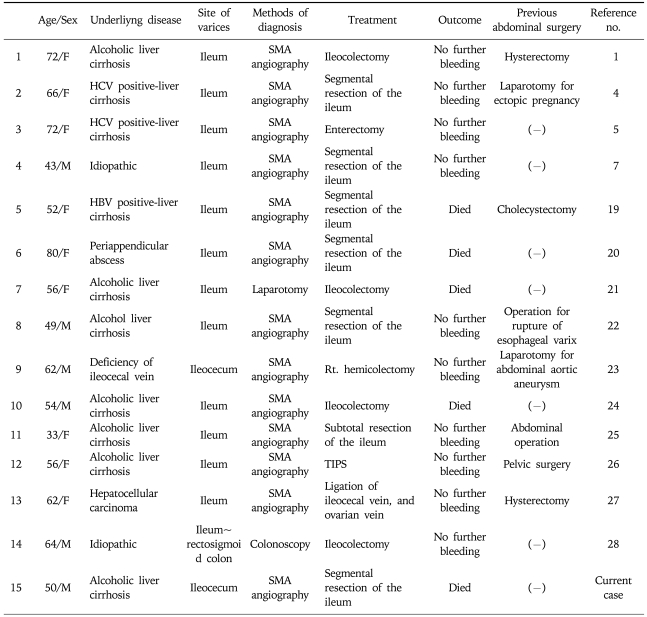

A 50-year-old man visited an emergency room due to massive hematochezia. He had histories of longstanding alcohol consumption and liver cirrhosis for 3 years. He had no history of operation. He passed large amount of bright red bloody stools on admission. On physical examination, ascites and hepatomegaly were prominently present. His blood pressure was 130/80 mmHg and pulse rate was 69/min. Laboratory findings were as follows: hemoglobin of 6.2g/dL; hematocrit of 19%; platelets of 2.43×105/mm3; prothrombin time of 42.8%; serum albumin of 2.7 g/dL; total bilirubin of 4.5 mg/dL; aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase of 563/149 IU/L. Hepatitis B surface antigen and hepatitis C virus antibody were negative. He was classified as having liver cirrhosis Child-Pugh class C at this point. Esophagogastroduodenoscopic examination revealed large non-bleeding esophageal varices and portal hypertensive gastropathy. The Colonoscopic examination showed severe bowel wall edema and a few diverticula in the ascending colon without an active bleeding site. One day later, he developed a massive hematochezia accompanied by hypotension. Active resuscitation was commenced and emergent colonoscopy was performed again. The colonoscopy revealed a Dieulafoy lesion with active bleeding at the terminal ileum. Three hemoclips were applied to the bleeding site successfully (Fig. 1). However, on the next day there was a massive and recurrent bleeding despite the clipping, necessitating transfusion of 11 units of packed red cells. A superior mesenteric angiography was undertaken to exclude an arterial bleeding during the episode of acute bleeding. In delayed phase dilated and tortous mesenteric varices were observed at the ileocecal area (Fig. 2A), and early filling of the dilated draining veins was observed in the ileocecal region (Fig. 2B). AVM with ileocecal varices was suspected. We performed coil embolization due to suspicious contrast extravasation observed in the distal portion of the right colic branch during the arterial phase (Fig. 2C). Nevertheless, massive lower gastrointestinal bleeding continued. Since the patient remained in a hemodynamically unstable state, an emergency exploratory laparotomy was performed although the fact that he was Child-Pugh class C liver cirrhosis. At the operation, a nodular cirrhotic liver and massive ascites were found. There was a dilated and tortuous vein with a diameter of about 0.5 cm-1 cm, on the surface of the ileocecal wall. A bleeding point was found at the 5 cm proximal portion of the ileoceal valve. Segmental resection of the ileum and colon were performed. The specimen consisted of 15 cm of the terminal ileum and 5 cm of the colon. Histologic sections showed a focal increase in the number of irregularly enlarged submucosal vessels (Fig. 3). Microscopic examination demonstrated several dilated angiodysplastic vessels with ruptures and hematoma formation in the submucosa (Fig. 4A) and showed the vascular element, which consisted of both thick and thin walled vessels (Fig. 4B). A plume of fibrin over a thick artery-like vessel was observed in the elastic stain (Fig. 4C). These findings were consistent with AVM. Although the patient's vital signs were stable and there was no further bleeding right after the surgical resection of the ileocecal varices, his condition deteriorated. The patient died of hepatic failure on the 13th day after the operation.

Fig. 1.

Colonoscopic view of ileoceal variceal bleeding performed for a Dieulafoy lesion due to spurting bleeding at the terminal ileum. Hemoclips are applied.

Fig. 2.

(A) Selective angiography of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) showing dilated tortuous veins (black arrow) in the delayed phase. White arrow: superior mesenteric vein (SMV). (B) Early filling of the dilated draining veins. Black arrow: SMA, white arrow: SMV. (C) Suspicious contrast extravasation (black arrow) in distal portion of the right colic branch, for which embolization is performed. White arrow: right colic artery.

Fig. 3.

Gross specimen shows a dilated submucosal vein in the resected ileum.

Fig. 4.

(A) Irregularly enlarged angiodysplastic vessels with rupture and hematoma formation in the submucosa. (B) Thick- and thin-walled vascular channels (black and white arrows, respectively) in the submucosa (hematoxylin & eosin stain; ×10). (C) Internal elastic fibers (black arrow) in thick artery-like vessels (elastin stain; ×100).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first case which illustrated that massive ileal variceal bleeding can be caused by AVM at the ileocecal area in a patient with alcoholic liver cirrhosis. Varices can occur in the distal gut, including small intestine and colon, though variceal bleeding is usually secondary to collateral venous pathways in the esophagus or stomach. Varices that occur at the site other than the esophagogastric area are described as ectopic varices and account for less than 5% of all varix-related bleedings.10 They are typically associated with portal hypertension. As the flow and pressure become increasingly high, portosystemic anastomotic veins may become ectatic and varicose in regions of potential portosystemic anastomoses.11 Although the most common site of ectopic varices is duodenum, varices involving the small intestine are commonly found at anastomotic sites and in adhesions after abdominal surgery.2-5 Collaterals within adhesions are possible causes of ectopic varices, particularly, in jejunum and ileum. Thus, previous abdominal surgery in patients with portal hypertension may be a predisposing factor in the development of ileal varices. Ueda et al.5 reviewed 57 reports that described small intestinal varices in PubMed dating from 1951 to 2003. Previous abdominal surgery was noted in 48 cases (84%).

In our case, the patient had ileal varices without a history of abdominal surgery. However, mesenteric angiography showed AVM at the ileocecal area. Interestingly, some studies noted that mesenteric AVM would cause portal hypertension and gastrointestinal variceal bleedings.6,7 Therefore, we hypothesized that the early and rapid drainage of blood through ileocecal AVM would develop dilated collateral vein at the ileocecal area and that accentuating the portal hypertension resulted in bleeding.

The term, AVM has been used to describe a wide variety of vascular lesions of the intestine, which include telangiectasia, angiodysplasia, vascular dysplasia and vascular ectasia.12 Moore et al.13 classified intestinal AVM as follows: Type 1 is a solitary localized lesion within the right colon usually in older patients. Type 2 is a larger, endoscopically visible, and probably congenital lesion common in small intestine. Type 3 is a punctate angiomas causing gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Considering that the feature of AVM of our case was single, well localized and an endoscopically non-visible malformation within the right colon in an older patient, the AVM in this patient could be classified as an intestinal AVM in the Type I category. Colonoscopy has occasionally been of value in the diagnosis of colonic AVMs. Visible telangiectatic lesions and multiple areas of mucosal erosion have been most frequently described.14 However, in cases of emergency, early diagnoses were often difficult because the bleeding sites may not be revealed by endoscopic examinations due to limited and poor field of vision. Ileocecal varices are often missed since air insufflations during the endoscopic examination raises the intraluminal pressure resulting in collapse of the varices.1 We also could not recognize the varices or AVM during the colonoscopy in this case. The most accurate method in diagnosing ectopic varices and AVMs is selective mesenteric angiography. In ectopic varices the delayed phase of the angiography shows large dilated tortuous veins. Angiographic hallmarks of an AVM of the bowel include early venous filling with a dilated draining vein, a vascular tuft, and a slowly emptying vein.14,15 In the patient with an angiographically demonstrable AVM, preoperative arterial catheter placement and dye injection are the most efficient method for localizing these lesions, and it also provides a reliable means of limiting the extent of resection.14 Therefore, mesenteric angiography should be considered during the earlier stage when working-up cases involving suspected ectopic varix.15,16

The histologic features of AVM are submucosal vascular malformation, the presence of thin walled ectatic venous channels, and thick walled fibromuscular vessels with internal elastic fibers connected with a thin walled vein,17 which are consistent with the pathologic results of our case.

The available therapies for variceal bleeding include conservative medical therapy; surgical options such as bowel resection and portosystemic shunt; and percutaneous treatment with either embolization or transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS).11,18 Coil embolization is a safe and technically easy treatment for ectopic variceal bleeding with effective, immediate results. However, recurrent bleeding is frequent and reintervention is often required.18 Thus, surgery should be undertaken as soon as the diagnosis is made, since bleeding from ectopic varices is most often profuse and recurrent. Surgical management such as segmental resection or shunt operation seems to be successful for controlling the excessive bleeding from ectopic varices.2

In a review of the literatures in PubMed from 1982 to 2007, a total of 14 cases was reported as ileal variceal bleeding.1,4,5,7,19-28 Among these 14 cases of ileal varix, 12 cases were diagnosed with SMA angiography.1,4,5,7,19,20,22-27 All of theses cases, bar one had operations performed.1,4,5,7,19,20,22-28 8 cases of them had a history of previous abdominal surgery.1,4,19,22,23,25-27 There were no cases that involved AVMs. We illustrated a review of the 14 ileal variceal bleeding cases (Table 1).

Table 1.

Reported Cases of Ileal Variceal Bleeding

In summary, we report a patient with alcoholic liver cirrhosis who had massive bleeding from ileocecal varices, which was associated with AVM. In patients with portal hypertension, ectopic variceal bleeding should be considered as another potential source of massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

References

- 1.Lewis P, Warren BF, Bartolo DC. Massive gastrointestinal haemorrhage due to ileal varices. Br J Surg. 1990;77:1277–1278. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800771126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kotfila R, Trudeau W. Extraesophageal varices. Dig Dis. 1998;16:232–241. doi: 10.1159/000016871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vescia FG, Babb RR. Colonic varices: a rare, but important cause of gastrointestinal hemorrhage. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1985;7:63–65. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198502000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohtani T, Kajiwara E, Suzuki N, et al. Ileal varices associated with recurrent bleeding in a patient with liver cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:264–268. doi: 10.1007/s005350050255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ueda J, Yoshida H, Mamada Y, et al. Successful emergency enterectomy for bleeding ileal varices in a patient with liver cirrhosis. J Nippon Med Sch. 2006;73:221–225. doi: 10.1272/jnms.73.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manns RA, Vickers CR, Chesner IM, McMaster P, Elias E. Portal hypertension secondary to sigmoid colon arteriovenous malformation. Clin Radiol. 1990;42:203–204. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(05)81935-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurihara H, Mochizuki H, Yamamoto S, et al. Massive intestinal bleeding caused by an ileal arteriovenous malformation: report of a case. Surg Today. 1994;24:552–555. doi: 10.1007/BF01884578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michalowicz B, Pawlak J, Malkowski P, et al. Intraabdominal arterio-venous fistulae and their relation to portal hypertension. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1996–1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tatekawa Y, Muraji T, Tsugawa C. Ileo-caecal arterio-venous malformation associated with extrahepatic portal hypertension: a case report. Pediatr Surg Int. 2005;21:835–838. doi: 10.1007/s00383-005-1524-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mark F, Lawrence S, Lawrence J. Portal hypertension and gastrointestinal bleeding. In: Vijay H, Patrick S, editors. Sleisenger & Fordtrans's gastrointestinal and liver disease. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2006. pp. 1925–1926. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naef M, Holzinger F, Glattli A, Gysi B, Baer HU. Massive gastrointestinal bleeding from colonic varices in a patient with portal hypertension. Dig Surg. 1998;15:709–712. doi: 10.1159/000018664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewi HJ, Gledhill T, Gilmour HM, Buist TA. Arteriovenous malformations of the intestine. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1979;149:712–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monk JE, Smith BA, O'Leary JP. Arteriovenous malformations of the small intestine. South Med J. 1989;82:18–22. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198901000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyer CT, Troncale FJ, Galloway S, Sheahan DG. Arteriovenous malformations of the bowel: an analysis of 22 cases and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1981;60:36–48. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198101000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monk JE, Smith BA, O'Leary JP. Arteriovenous malformations of the small intestine. South Med J. 1989;82:18–22. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198901000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cello JP, Crass RA, Federle MP. Colonic varices: an unusual source of lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. West J Med. 1982;136:252–255. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mudhar HS, Balsitis M. Colonic angiodysplasia and true diverticula: is there an association? Histopathology. 2005;46:81–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Macedo TA, Andrews JC, Kamath PS. Ectopic varices in the gastrointestinal tract: short- and long-term outcomes of percutaneous therapy. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2005;28:178–184. doi: 10.1007/s00270-004-0148-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Falchuk KR, Aiello MR, Trey C, Costello P. Recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding from ileal varices associated with intraabdominal adhesions: case report and review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 1982;77:859–860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hojhus JH, Pedersen SA. Cirrhosis and bleeding ileal varices without previous intraabdominal surgery. Acta Chir Scand. 1986;152:479–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arst HF, Reynolds JD. Acute ileal variceal hemorrhage secondary to esophageal sclerotherapy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1986;8:603–604. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198610000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shimada Y, Katayama T, Monden K, et al. A case of portal hypertension with massive gastrointestinal bleeding from ileal varices. Nippon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1984;85:611–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sugiyama S, Yashiro K, Nagasako K, et al. Extensive varices of ileocecum. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:1089–1091. doi: 10.1007/BF02253001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahn KH, Shin SJ, Chae HS, et al. A case of massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage due to ileal varices. Korean J Gastroenterol. 1997;30:815–819. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mashimo M, Hara J, Nitta A, et al. A case of ruptured ileal varices associated with alcoholic liver cirrhosis. Nippon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2007;104:561–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lopez-Benitez R, Seidensticker P, Richter GM, Stampfl U, Hallscheidt P. Massive lower intestinal bleeding from ileal varices: Treatment with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPSS) Radiologe. 2007;47:407–410. doi: 10.1007/s00117-005-1279-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kobayashi K, Yamaguchi J, Mizoe A, et al. Successful treatment of bleeding due to ileal varices in a patient with hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:63–66. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200101000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lopes LM, Ramada JM, Certo MG, et al. Massive lower gastrointestinal bleeding from idiopathic ileocolonic varix: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:524–526. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0279-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]